ABSTRACT

This study addresses normative orientations to smartphone use in Swedish upper-secondary classrooms. We present a Nexus Analysis from a policy enactment perspective of a material comprising ethnographic interviews, classroom video observations, and smartphone screen capture, investigating how a cultural conception of the smartphone as a source of disturbance is negotiated in discursive and embodied social action. Three groups of policy actors – head teachers, teachers, and students – balance competing agendas such as digitalization strategies, popular media narratives, and student autonomy and peer relationship maintenance. There is a tension between orientations to the smartphone as a legitimate resource for socialization and learning in the digitalized classroom, but also as an exception to desired digitalization – a potential threat to the social and disciplinary order of the classroom. Notably, the students display considerable awareness of such tensions, in reflective comments made in interviews and in displayed strategies for managing their smartphones in class.

1. Introduction

The smartphone is a contested object in the educational context, and heavily debated in popular media. This study investigates negotiations of the role of the smartphone in Swedish upper-secondary classrooms, in the context of broader discourses of digital technologies in education. In Sweden, a national digitalization strategy (Utbildningsdepartementet Citation2017) expresses the aim that Sweden should be world-leading in digitalization. On the other hand, as in many other parts of the world, there is heated public debate over the increasingly ubiquitous presence of smartphones in the hands of school-aged learners. These debates construct a variety of threats potentially posed by smartphones to children and young adults, pedagogically, socially, and cognitively (Ott Citation2017). As is further discussed below, evidence to support these assumptions is sparse and contradictory. In Sweden, there are no national directives nor any universal agreement on how schools are supposed to deal with the presence of smartphones among students. However, there are recurring calls and proposals for smartphone bans, including a proposal from the current Swedish minister of education. This makes for a somewhat confused situation where the smartphone is variously normalized and problematized, and stake-holders – notably, head teachers, teachers, and the students themselves – act according to sometimes conflicting agendas.

This article presents findings from a project on digital technologies in the Swedish upper-secondary classroom. Here, we focus specifically on the construal of smartphones as a potential source of disturbance by head-teachers, teachers, and students. Adopting a Nexus Analytic and video ethnographic methodological framework (Scollon and Scollon Citation2004), and enlisting the concept of policy enactment (Ball, Maguire, and Braun Citation2012) as a theoretical framework, we study how these policy actors position themselves in regard to smartphones in interviews, and how smartphones are manifestly used and oriented to in classroom video observations – in short, how enacted policy on smartphones in the classroom is articulated as a nexus of social practice by key stake-holders. This analytical focus is motivated by the broadly contested status of smartphones in the classroom in Swedish society in general, but also, as will be seen, how this contested status is a manifest concern for our research participants. Aiming to shed light on this nexus of social practice from a policy enactment perspective, we pose the following research questions:

How do head teachers, teachers, and students construct and relate to the idea of the smartphone as a potential source of disturbance in the classroom?

How do these participants make relevant and orient to popular and institutional discourses on the digitalization of school generally and controversies surrounding smartphones in school specifically?

1.1. Digitalization and smartphones in the classroom

Sweden’s educational system is undergoing a comprehensive push toward digitalization, with educators facing political demands for and expectations of this process. A large number of both national and international policies focus on equal access to digital technologies and call for developing the digital literacy of citizens (OECD Citation2016; Redecker Citation2017), as part of what constitutes so-called ‘21st century skills and competences’ (OECD Citation2016, 9). The Swedish national curriculum has been revised to emphasize digital competence across school subjects (SFS Citation2010, 800) and a special strategy for digitalization of education has been presented (Utbildningsdepartementet Citation2017). Major economic investments are made into supplying schools with digital hardware and software. For example, a majority of Swedish schools organize and administer their work through educational platforms or learning management systems (Skolverket Citation2016), and subject content is largely relocated from printed text to online resources and multimodal texts (Willermark Citation2018). Moreover, it has been the case for years that almost every upper secondary school student (98%) has access to a personal smartphone (Alexandersson and Davidsson Citation2016). Increasingly, these phones are present and used in school, often even during class (Forsman Citation2014; Ott Citation2017; Sahlström, Tanner, and Valasmo Citation2019). The schools investigated in the present study conform to these tendencies, being examples of extensively digitalized classrooms, where students, in addition to carrying personal smartphones, are provided with access to laptops and other digital devices, and teachers and students both make use of digital devices and Internet connectivity in teaching and learning activities and share overall positive attitudes towards digitalization.

Despite this digitalization push, personal smartphones have mostly not been regarded as a potential resource for learning, but rather as a source of disruption and distraction (Hassoun Citation2015; Ott Citation2017). Beside studies that have focused on public debate (Ott Citation2017), research on smartphones in class has highlighted the link between student school performance and the banning of phones in classrooms. However, results have been contradictory (Amez and Baert Citation2019). While some studies suggest that smartphones can impair students’ academic results (Beland and Murphy Citation2016; Amez et al. Citation2021; Lee et al. Citation2021), other studies suggest that phones have positive effects (Kuznekoff, Stevie Munz, and Titsworth Citation2015), or no effects at all (David et al. Citation2015; Kessel, Hardardottir, and Tyrefors Citation2019). Whether correlations are positive or negative, it remains difficult to establish causal relationships and mechanisms (Baert et al. Citation2020; Chen and Yan Citation2016). In the present study, however, our focus is not on any potential correlations between in-class smartphone presence and academic performance or outcomes, but rather how the smartphone is normatively oriented to in the social life of the classroom.

For students such as those that we have followed, smartphones are especially central to maintaining social relationships and participating in interactions with close friends as well as in broader networks (c.f. Olin-Scheller, Tanner, and Öhman Citation2018; Sahlström, Tanner, and Valasmo Citation2019). Smartphones are also used for task-related activities, such as information retrieval. This often happens under the teacher’s radar and is not attended to in the shared discursive space of the classroom (Asplund, Olin-Scheller, and Tanner Citation2018). In a Swedish context, Olin-Scheller and colleagues (Citation2020) show that smartphones do not primarily appear as a disturbance in the classroom, but rather they are used intermittently when the intensity of teaching subsides, and in ways that conform to ordinary organizational and interactional classroom patterns. Valasmo, Paakkari, and Sahlström (Citation2022) describe similar practices in Finnish upper-secondary school, and Aagaard (Citation2017) in a Danish business college. Given the emergence of such findings, the popular perception of the smartphone as a threat to the order of the classroom may arguably be seen as an instance of a media moral panic (Drotner Citation1992; Standage Citation1998), a behavior among adults (often parents and teachers) that frequently follows the introduction of new technologies or cultural trends adopted early by young people as these are ‘interpreted as threats toward young people’ (Svenningsson Elm Citation2008, 113; cf. Selwyn and Aagaard Citation2021). At the very least, then, there is a lack of empirically-grounded study of how smartphones actually do end up being used and integrated into social life at school.

1.2. Smartphones in the classroom from a policy enactment perspective

We take the notion of policy enactment as a theoretical point of departure (Ball Citation2006; Ball, Maguire, and Braun Citation2012; Singh, Heimans, and Glasswell Citation2014). From a policy enactment perspective, policy is seen as a matter of dynamic, multi-lateral processes, emerging in the interface of practices, actions, interpretations, and translations and across many levels of an organization. We argue that discourse constructing smartphones as a source of disturbance in the classroom is a matter of policy, and specifically of ‘doing behavior policy’ (Ball, Maguire, and Braun Citation2012, 98). Issues of behavior have always been central to education, and is part of what constitutes schools as sites for socialization.

Behavioral policies are often encoded into the form of artefacts such as classroom codes of conducts, anti-bullying plans, schoolyard rules, and the like. However, there are also unwritten rules. In today’s Sweden, normative rules regarding the presence and use of smartphones in school are very much in the process of being negotiated, and few schools have established written rules, with many leaving smartphone policies up to individual teachers to make and develop ad hoc.

Policy is enacted by the people who inhabit a given institution or organization – in our case, head teachers, teachers, and students – as different agendas, ideologies, and interests meet (Ball Citation1997). Various discourses are in place that contribute to shaping what positions and views are available or salient to participants. Building on Foucault, Ball, Maguire, and Braun (Citation2012) describe how normative positions are produced in relation to discourses at play in participants’ lives. Actors in different organizational positions mutually and jointly constitute policy processes, but rarely on equal grounds. The social practices of schools, certainly, are suffused with power relationships and a spectrum of social conditions that enter into the doing of policy. In enlisting this perspective, we argue that smartphone policies in schools are not only – and perhaps not even primarily – developed on a political or institutional level: Smartphone policies are also made in practice by stakeholders at all levels, including teachers and students themselves.

2. Nexus analysis: material and methods

This study draws on materials collected in the video ethnographic research project Connected Classrooms (Swedish Research Council grant no. 2015-01044). To methodologically operationalize our object of interest – policy enactment in a school-situated context – we adopt an ethnographically grounded approach based on Nexus Analysis (Scollon and Scollon Citation2004, Citation2007). This is a form of discourse analysis suitable for the complexity of ethnographic materials, geared towards shedding light on how social practices emerge precisely in the interface of discourses, histories, and institutional norms and orders of interaction. The framework is thus well-suited to addressing questions such as those we pose in this study.

2.1. Material and participants

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 22 students, six teachers, and five head teachers between 2016 and 2018. The participants come from two upper-secondary schools, representing both preparatory programs for higher education and vocational programs, with students in Years 2–3 (aged 18–19). The schools are situated in a mid-sized town in Sweden, and each class consists of around 25 students. The interviews were 30–60 minutes in length and were all audio recorded and transcribed. The interview guide contained a broad array of questions pertaining to digitalization and the students’ use of digital devices.

Classroom recordings focused on the students’ activities during lessons in different subjects at both participating schools, in a total of eight classes, yielding 69.3 hours of video. All students included in the study were informed about the aims and implementation of the study. They were asked to participate in classroom video recordings and, and to allow us to observe their use of smartphones and computers. Almost all students gave their consent to participate, and those who did not were excluded. We made efforts to develop trust and a dialogue with the students, and they were given full rights to see the data and to withdraw whatever and whenever they wished. The project was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (reg. no. 2015/452).

Out of the 22 interviewed students, 11 were ‘focus students’ for the video recordings. One focus student per recording session had their smartphone screen recorded during class via a screen mirroring application. They were also video recorded in the classroom, focusing on the students, their surrounding peers, and their desks and working resources (laptops, pen and paper, etc.). Teachers were occasionally visible on camera, permitting some observations of teacher behavior in interactions with the focus students.

In the spirit of Nexus Analysis, this combination of materials makes possible the analysis not only of expressed attitudes and participant-described practices, but also analysis of how interaction plays out in the situated practice of the classroom. We could thus achieve a triangulatory analysis of orientations and attitudes displayed by participants in interviews and manifest practices in the video material. This triangulation is mainly limited to the student participants, since they were the focus of the video ethnography. Below, we thus focus primarily on the interviews, since these represent all three groups of participants, with observations from the video ethnography mainly being used in the section focusing on the students. Excerpts from the interviews were translated from Swedish into English by the research team, with names replaced by pseudonyms. Further, we distinguish participants using numbered labels (Head1, Teach3, Stud13, etc.).

2.2. Analytical procedure

In our dataset, we have identified and analyzed sequences that make manifest norms and practices that relate to our chosen focal nexus of social practice (Scollon and Scollon Citation2004, Citation2007). Our process of identifying the notion of the smartphone as a source of disturbance as a salient nexus to study more closely may be described using the five-step procedure described by Scollon and Scollon (Citation2004, 153–155): establishing a social issue to study, identifying crucial social actors, observing an interaction order, determining the most significant cycles of discourse, and establishing a zone of identification. The notion of the smartphone as a potential source of disturbance in the classroom is well established as a salient social issue through the recurrence of this theme in public debate on technology and education. Through our data, we could observe the centrally relevant interaction orders and how discourses of smartphone use circulate through the classroom scene. We thus identified the presence of the smartphone, and orientations and practices involving the use of smartphones, as an especially important focal point for analysis due to its combined relevance to public and institutional debate as well as its relevance as an empirically manifest concern for the research participants.

The nexus analytical approach frames social practice as emerging in the interplay of the three dimensions of historical body, interaction order, and discourses in place. In our case, the historical body is the sum of participants’ habits of action, views and opinions, and reported experiences. In observations from the video recordings, as well as from reported experiences, we also generate a picture of classroom interaction orders featuring the students’ personal smartphones, which makes visible how interactional norms, expectations, social roles, and modalities play into the construction of the smartphone as a potential source of disturbance. We see evidence of the discourses in place throughout the accounts that participants give in the interviews, as well as from observations. Thus, the notion of the smartphone as a source of disturbance is realized in social practice in a number of ways in our data – as a topic of discussion as well as through interactional orientations, as we will show below.

3. Results

In this section, we present our findings by moving through the perspectives enacted by head teachers, teachers, and students, shifting attention from matters of school policy (mainly represented by the head teachers, and to some extent the teachers) to matters of classroom policy and practice (represented by teachers and students). We summarize, paraphrase, and present selected excerpts, to represent majority opinions and recurring tendencies, while also making space for divergent opinions and exceptional cases.

3.1. Head teachers

The five head teachers oriented to the notion of the smartphone as a potential disturbance in various ways. Their perspectives reflect common discussions among faculty, media debate, and conversations with parents of students, which feature smartphones as a recurring topic. The head teachers construe this topic as contentious and polarizing for teachers, but they themselves are not convinced that smartphones are disruptive. Head4 says ‘I’m not always certain that [smartphones] disturb a lot, and then I suppose the brain scientists are saying something else, but I don’t think that [the students] themselves really experience it as disruptive.’ Head4 mentions ‘brain scientists,’ referencing popular media discourse on the issue at the time which frequently invoked cognitive or neuroscientific research. Three other head teachers also allude to the media narrative on smartphones at the time, dismissing this narrative as untrue and overblown. Head2, says that ‘the media tends to focus on problems, and not at all on the utility of using [smartphones] in school.’ Head2 construes the media narrative as ‘antiquated,’ but also as something that is on the way out:

(Head2) Yes well it’s still that it’s just a disruptive element. That is, something that doesn’t really belong in school. Maybe stuck in this, you’re liable to get stuck on matters of discipline or order. […] But it would have been cool if there had been a focus on what opportunities arise with it instead. Because it’s really carrying the youth ahead.

The head teachers overall seemed keen to express a nuanced view of the smartphone, highlighting potential benefits, but also problematizing some aspects of the role of digital devices and online connectivity in the lives of young people, such as social distraction from schoolwork. Head4 suggests that the smartphone is too often identified as causing a perceived epidemic of issues relating to new digital technologies, such as young people being unable to sleep at night, addiction to digital games, or a rise in cyberbullying. Head4 disaligns with this discourse by suggesting that the real problem is not the smartphone itself, but rather that some individual students have trouble limiting their use of mobile devices and computers in their spare time. Further, Head4 argues that some conflicts that erupt in social media occasionally end up leading to disruption in the classroom. In such cases, the interviewee emphasizes, the issue is not really the use of smartphones in class, but rather how peer conflicts that arise outside of the classroom are brought into it.

It is clear from such accounts that the head teachers bring to the interview situation their previous experiences of collegial discussions with faculty, reading the news, conversations with parents, and their own observations from working at the schools. Similarly, the head teachers follow and have opinions on popular media debate, as well as educational discourse on digitalization. The latter discourse was put in place in the interview situation by the interviewer, who was explicitly eliciting views on digitalization. As the head teachers construct the situation, some teachers desire that the head teacher function as a policy provider, and desire a justification for banning smartphones from the classroom. The head teachers suggest that these teachers as overly influenced by the media narrative’s negative framing of smartphones.

The head teachers overtly position themselves in alignment with the digitalization policy of the Swedish national agency for education, and frame the smartphone in line with this policy as a potential resource to take advantage of. Ideologically, thus, the head teachers frame the smartphone positively, and position themselves in opposition to a media image of the smartphone as a threat to schools. Importantly, they also position themselves as sympathetic to and concerned with the wellbeing of students, while being under pressure from some teachers and parents. In this sense, they appear as exposed to a cross-pressure (Berg Citation2018) of enacting and enforcing policies that affect and are evaluated by multiple actors with different views and agendas, ranging from state and municipal governance to parents and guardians, the community, and not least the wants and wishes of teachers and students.

3.2. The teachers’ perspective

The five interviewed teachers may also broadly be described as positive and open-minded about the potential benefits of digital devices in the classroom. However, they are less optimistic than the head teachers. ‘The phone is a disruptive element for many of the students,’ says Teach5, framing the presence of smartphones specifically as an issue for the students. The teachers also agree in perceiving the smartphone as belonging to the private sphere as opposed to the personal computer which is perceived as a more legitimate tool for schoolwork. The teachers describe the students as being on their phones often and for extended periods, and as mainly using their phones for social media. Teach2 says that ‘the usual thing isn’t to look at Wikipedia but rather to look at social media,’ indicating that there could be legitimate uses for the phone in class (such as information retrieval) but that the norm is to use the phone for off-task and illegitimate purposes. ‘Snapchat is what disturbs the most,’ says Teach1, referring to the most popular social media application among youth at the time.

Compared to the head teachers, the teachers were less oriented to media discourses. Instead, the teachers emphasized the normative interaction order of the classroom, and the historical body of their experience of classroom sociality. The most prevalent discourse put in place by the teachers is one of disciplinary and social order. Specifically, the teachers suggest that students’ use of smartphones in class makes it more difficult for them to connect with one another, and pulls the students’ attention from the teacher. Teach3, who held the strongest negative views, reported experiencing ‘a flood of snapchats and messages and everything like that coming in’ on students’ phones. This experience is clearly frustrating to the teacher:

(Teach3) [… ] the students lose track of what’s happening in the classroom. […] It bothers me because they aren’t here. They aren’t focused on what we’re doing.

This teacher, then, indicates a normative disciplinary and social order appropriate to the classroom – one of attentive co-presence – and construes the smartphone as a threat to this order, something that pulls the students’ attention away from the official business of the classroom. ‘It’s also a disturbance for the person sitting beside you and that maybe actually wants to work on the assignment but sees that you are on that website with shoes and fun stuff,’ says Teach3. The other teachers are less critical, but also orient to this norm of attentive co-presence. As Teach1 puts it, ‘I do really want to feel that everyone is paying attention.’ Another teacher explicitly articulates a view of the smartphone as disrupting the classroom interaction order:

(Teach4) […] when my students want to talk to me and they pull up the phone, I just leave. That becomes a kind of clear signal. Are you here to talk to me, then we are the ones talking. And then that third [party] cannot have higher priority than what this has.

Some of the teachers position themselves – as adults, as teachers – as responsible for disciplining the students into an awareness of institutional as well as broader social norms. ‘Many of the students don’t know what the boundaries are so then we have to talk about that together,’ says Teach1. Teach 3 argues that young people need to develop a consciousness of how smartphones affect their lives, saying that ‘if you don’t have your eyes opened to what role [the smartphone] plays in your life, then you’ll bring it with you into your university studies as well.’

The smartphone is also seen as a crutch for students who lack the will or capacity to challenge themselves socially or in learning situations: ‘Sometimes I see that the smartphone is an escape for the students,’ says Teach5, and argues that ‘it is easy go there when you can’t manage to bring a discussion to another level or when you are faced with getting to know a new person.’ Teach3 observes that there’s an important point to carrying on a discussion in class ‘instead of saying five lines and then picking up one’s phone,’ using the phone as ‘a sort of security blanket or a lifeline to the extent that one forgets the very reason for even being here.’

The teachers also construe the smartphone as an obstruction to a variety of teaching and learning activities. Teach4 observes that students frequently pick up their phones during long lectures, ‘especially if there are complex things being explained – then [the phones] typically start coming up.’ The sense that the presence of smartphones in the classroom can be a distraction from at least some important classroom business is shared by all the teachers. Some report acting on this by occasionally being more attentive to their students’ smartphone use, asking the students to put down their phones, and sometimes even collecting their students’ phones. For instance, Teach2 reports routinely collecting student phones during exams, continuing as follows:

(Teach2) And also while giving instructions or oral reviews when they need to be active and discuss things or when we have others coming in to talk, then I feel that it’s a matter of respect. If we bring in a lecturer then I’m very careful. Sometimes you actually need to be fully focused.

Most of the teachers, however, construe the phones as a minor and manageable problem. ‘You kind of accept that the phones are out,’ says Teach1: ‘Most of the time you can just ask them, if they’re on their phone – did you hear what I said? And when I ask them to repeat it back to me they actually can.’ In the classroom recordings, we see that students as a matter of course use their smartphones in ways that do not attract attention from the teachers, but there are also a few instances of teachers manifestly orienting to smartphone use as a disturbance, albeit never in a very contentious way. In one case, the students have been assigned a reading task. The teacher notices a student oriented to his phone rather than his book. The teacher walks up and says ‘try reading now,’ waving a hand at the group. The student is already in the process of putting down his phone as the teacher is speaking, suggesting that the admonition was anticipated.

While the teachers were overall more oriented to their experiences of classroom sociality rather than media discourses, there was one instance of a teacher discussing public debate on smartphones as being politicized in educational context:

(Teach2) [It]’s terrible that you can run for election on the promise that the smartphone is one of the campaign promises be-all and end-all. There’s so much about how it bothers the students, and, sure, it’s a disturbance and the students are very stressed out and feel bad, but if it’s the smartphone or not I just don’t know. But I am for, I don’t think there should be a ban. Teachers need to practice more leadership in how the phone may be used and risks attached to that, and parents need to know more about how to handle the smartphones.

In sum, the teachers may be described as divided and ambivalent in their policy enactment. While some of the teachers had quite negative views of smartphones and of students’ ability to manage their phone use, none of the teachers favored an outright ban. The teachers did raise concerns of the smartphones as a potential threat to the social and disciplinary order of the classroom, citing their normative understandings of this interactional order as well as the historical body of their reported experiences to make their arguments. However, we did not see the teachers regularly taking action to manage smartphone-related trouble in their classrooms, nor hear them express major concerns in this regard.

3.3. The students’ perspective

The students comprised the largest group of participants, and displayed a greater variety in perspectives on the issue of smartphones in class. They were largely negative toward the idea of a smartphone ban, and instead frequently argued that upper-secondary students are mature enough to be able to take responsibility for using their phones in appropriate ways. They also argued in various ways that keeping their phones with them was part of getting used to social life outside of or after school:

(Stud20) I think it’s good that you get to use your phone and computer, because I think that this is what you will be using most in the future, when one is out on the job market, as long as you use them in the right way.

In the vocational programs the smartphone may even be an important tool in learning activities. A hairdresser student, Stud13, said that she uses her phone often, among other things for documenting haircuts and colorings, as well as practicing marketing to attract customers. Conversely, she experienced the phone as being more or less invisible during theoretical classes, except for occasional glances to monitor one’s social media.

Some of the students have a first language other than Swedish (the majority and teaching language). One of these students notes that the smartphone is important to her as a translation tool. She frequently uses a translation app during class to improve her understanding of words and texts. Despite this, she generally keeps her phone hidden in a pocket during class:

(Stud1) […] when we’re doing assignments and stuff, then I use my computer. I know that it’s possible to do the assignments on smartphone as well, but I don’t do that. Because it kind of distracts me when like some friend sends snaps to me or then it disturbs me.

Only one student argued in favor of clear rules banning phones in class: ‘I like it actually. Because I do know how many use their phones, so … I’m generally sitting in the back so I see many taking out their phone, taking a snapchat and like putting it down again’ (Stud19). The student’s use of ‘actually’ (Swedish faktiskt) indexes an awareness that the expected stance from a student is to be against a ban, as most of the participants were. However, when it comes to the schools observed in this study, it turns out that the students had very different ideas of what their school’s policy on smartphones actually was. Some students had come to believe that there existed an ‘official’ school policy on smartphones – as was not in fact the case – whereas others had picked up on there being different rules with different teachers. Stud16 puts it as follows:

(Stud16) It depends. [Birgitta] tells us off quite a lot. […] [Janne] doesn’t say a lot. And I don’t know, I almost think that can work better. Because it becomes, like, if [Birgitta] tells someone off for choosing to use their phone, to reply to a snap or whatever. Then it feels like it’s made out to be a bigger thing. Because then everyone actually is disturbed by it. But [Janne] sees … you know that he sees you kind of. But then you put it down after. Then no one else has been like disturbed by it. […] But that’s almost a better way of doing it.

The image that emerges is that the students are uncertain yet actively reflexive when it comes to how to deal with their personal smartphones in class. Several of them orient to media and popular debate discourses, distancing themselves from what they experience as a kind of prejudice: ‘It feels like we don’t do anything in school and just sit and fiddle with our phones all the time. It’s not true, I don’t think’ (Stud15). Several students, like the teachers, orient to the normative social order of the classroom, but position themselves as being quite concerned with matters of respect and consideration for others, voicing various strategies – sometimes contradictory – for negotiating these issues. For instance, some students argue that it’s generally unproblematic to check your phone during longer lectures:

(Stud18) Yeah, primarily during these lectures where it isn’t, well, you don’t have any text to copy but rather just need to sit and listen and take notes on what the teachers say. Then it’s a lot simpler to just like pick up your phone and listen with half an ear kind of.

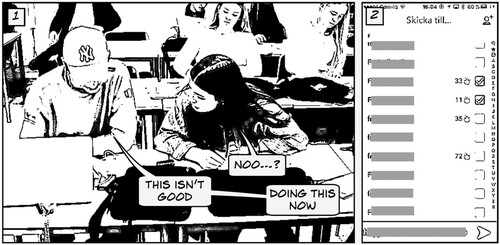

shows one of the focus students, Hassan, who could be seen practicing this strategy several times in the video observations, picking up his phone for relatively extended periods of time during longer lectures, and once during the showing of a video. In this instance, this strategy causes a bit of trouble. The teacher has recently signaled a transition between activities is about to take place, and Hassan takes this opportunity to pick up his phone, open the social application Snapchat, and send a mass message to all his contacts with which he is currently maintaining a ‘streak’ (as would occur between two friends on Snapchat if they message one another back and forth at least once per day). Hassan has close to 100 ongoing streaks, and can be seen systematically going through his friends list and selecting all these friends as recipients (, Panel 2). As he is about halfway through the list, the teacher begins to instruct the students on vocabulary items that they are supposed to note down for the upcoming task. Hassan seems stressed by this, and says ‘this isn’t good … doing this now’ to a peer (, Panel 1), as he hurries to finish ticking all the intended recipients of his message and his peer turns her attention back to taking notes. Hassan thus produces a negative assessment of his own behavior, recognizing even as he is doing it that his use of his phone on this occasion is problematic.

Other students maintain that it is precisely during lectures that you should give the teacher your undivided attention, out of respect or not to ‘make the teachers sad’ (Stud11). Some report that they feel more free to use their phones while working independently on assigned tasks:

(Stud 16) (…) if [the teacher is] there to discuss something with us, then I wouldn’t be fiddling with the phone. So. It’s maybe if we are working on our own with study questions or if you are stepping out to get something.

The students describe off-task smartphone use as being common among their peers, and construct it as a strategy of dealing with boring stretches of class or giving oneself a short break. Many of the students suggest that they may be distracted from work by their own phones, but some also argue that it can be helpful in other ways. For instance, some students report feeling like they can focus better on individual work if they get to use headphones to listen to music.

The visibility of smartphones in the classroom was a recurring theme. The students try to be discreet and tactful about their phone use during class, but also report feeling like their phone use is visible and accountable to their peers as well as teachers.

(Stud19) Yeah, then you usually take it like that and keep it down low for some dumb reason and you sit like this. Because it’s like … head down like this, it’s so obvious. I read some teacher had put on their Facebook or something like that, Tumblr, and it said like, Dear students, we know when you use your cellphones. You don’t look like at your [schoolwork] and smile. (Laughs). I just felt that’s pretty obvious. (Parts in italics were spoken in English)

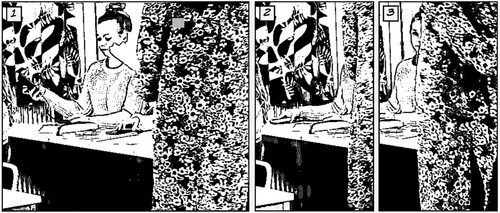

The students are thus concerned with discretion, but do not imagine that their smartphone use is invisible. Strategies of concealment, which were recurrent in our video observations, may rather be seen as a respectful orientation to a normative expectation that smartphone use should be non-intrusive in the interactional space of the classroom. shows one focus student, Sigrid, employing such a strategy. As the teacher is preparing to hand out task sheets, Sigrid is checking messages. When the teacher approaches her desk, Sigrid shifts her attention to the teacher (, Panel 1), and lowers the phone to the desk (Panel 2). As Sigrid sees that the teacher turning to leave, she picks the phone back up (Panel 3).

In many ways, thus, a majority of the participating students display reflexivity concerning their use of smartphones, and an orientation to the social order of the classroom that overlaps substantially with the teachers’ agenda. At the same time, they indicate a tension between the desire to do well in school and to maintain a presence and responsiveness in their online-mediated peer relationships. This maintenance of relationships also includes caring for classmates who are having personal issues, or who are home sick. In the latter case, this care may also include learning-relevant interaction, for instance updating a peer who is home sick on what is going on in class (as we observed one of our focus students doing through instant messaging).

Some key concepts that recur in the interviews with students are self-control, focus or concentration, and dependence. However, managing one’s self-control is only constructed as a serious problem by one student:

(Stud15) It is a disturbance partly because you like lose focus. But that depends on your own self-control. How you deal yourself. Because not everyone is like that, everyone doesn’t pick up their phone. It’s different. I’m one of the ones who picks up the phone. But my friends don’t pick up the phone. (…) While I just shut down and focus only on the phone.

Stud15 is positions himself as struggling to resist the phone. Nevertheless, he is construing his difficulty as an exception to the norm, and is further showing that he is capable of reflecting on this challenge.

From the students’ accounts and our video observations, it is evident that students recognize that there are better and worse strategies for managing smartphone use in class. Further, the social demand of being available to peers in social media is largely considered to be valid even if it sometimes comes into competition with attention to schoolwork. There is a strong discourse in place of personal responsibility, which some of the students connect to age: At their age, as young adults, they both should and need to become adept at managing themselves and being respectful to their teachers and each other. Smartphones exist among these participants as an essential part of the social infrastructure of contemporary life, and they, therefore, regard a ban on phones as being unrealistic or counter-productive: ‘It’s kind of like banning cars. I mean, it’ll never work to ban completely. It’s like, well … you learn how to use them’ (Stud21).

In summary, we see the students negotiating and enacting policies of smartphone use in the classroom in a highly reflexive manner, in relation to three main factors: Firstly, a sense of responsibility for being a good student, for one’s own learning and achievements in school; secondly, a sense of social responsibility for respecting the teachers’ feelings and authority in the classroom; and thirdly, a sense of responsibility to be socially available to and supportive of their peers via social media.

4. Discussion and conclusion

Our findings make clear that, in these classrooms in Sweden, the discursive construction of the smartphone as a disturbance is present, and is enlisted to make sense of and enact behavioral policy in the digitalized classroom. While some participants align with this discourse, most of them also contest and resist it in various ways. There is thus a tension between viewing the smartphone as a social and educational resource within the digitalized classroom, and viewing it as something that belongs outside of the classroom, an exception to desired digitalization. All three groups of actors orient to an understanding of the smartphone as a potential threat or challenge to classroom social order, and to the students’ engagement in learning. The head teachers orient to a kind of cross-pressure between public debate on smartphones and cutting-edge digitalization policy. Teachers are especially concerned with their experience of meeting and engaging with their students, and, arguably, their authority or ownership or the attentional space of the classroom. The students are concerned with respecting both their teachers and peers, but also with their own self-disciplining abilities. However, all three groups of actors ultimately enact an open-minded attitude, rejecting any one-sided narrative of the smartphone as an intrinsically or severely disruptive technology.

In the video observations, it is evident that students employ various strategies to partition instances of smartphone use so as to not disrupt the official classroom business, and handle their smartphones so as to respect their teachers. Only rarely can we see the smartphone impinging on the disciplinary order of the classroom (cf. Olin-Scheller et al. Citation2020; Sahlström, Tanner, and Valasmo Citation2019). The students, but also the head teachers and teachers also recognize that smartphones today constitute an important and integral part of the social lives of youth, and that banning or heavily sanctioning the use of smartphones in class comes with social and emotional costs.

The three groups of policy actors studies here overall do not seem particularly troubled by smartphones in practice, while still needing to position themselves in relation to a complex weave of competing ideologies, norms, needs, desires, and agendas (cf. Ball Citation1997). They accomplish these positionings mainly by drawing their own lived experiences, the historical body of their dealing with smartphones in the classroom. All participant groups – but mainly the head teachers – orient to popular debate, mostly with a critical attitude toward a lack of nuance. In particular, the students appear in our analysis as substantially more reflexive policy actors than one might imagine based on popular opinion. Indeed, the students also seem more actively reflexive than their own teachers are aware of. There are competing agendas at play when students manage the social complexity of interacting with and through their smartphones in coordination with the social and pedagogical activity of the classroom, but this tension is not unnoticed. The teachers are, as one might expect, all the more concerned with the normative social and disciplinary order of the classroom, and the classroom’s official business. Unlike the head teachers, the teachers did not comment much on any novel pedagogical possibilities afforded by smartphones. This is surprising given the emphasis that Swedish education ordinance, policy, and teacher training puts on digitalization.

Our results indicate that in schools like those investigated here, the key stakeholders are already negotiating and settling on good-enough policy practices for dealing with smartphones. Notably, while international research on smartphones and other digital devices in a school context has often focused on the potential impact of these technologies in terms of academic performance or outcomes (e.g., Amez and Baert Citation2019), our participants were at least as concerned with the potential impact of smartphones on the social and disciplinary order of the classroom. While outcomes certainly are a legitimate concern (to our research participants and to stake-holders in education in Sweden as well as internationally), we would argue that too little attention has been paid so far to this social and normative aspect. While our study is qualitative and limited in scope to only two schools in the specific educational context of Swedish upper-secondary education, we would nevertheless argue for some potential implications. Firstly, formal policies banning or severely restricting students’ smartphone use at school may be unnecessary and counter-productive. Secondly, we find that teachers should likely be able to enter into constructive dialogue with their students based on mutual respect, rather than adopting a paternalistic or disciplinarian stance. Notably, we make these arguments in relation to learners in their late teens. For younger learners, it is possible that other considerations may be warranted, as our student participants themselves argue. However, this is also an empirical question: Kay, Benzimra, and Li (Citation2017), for instance, found that younger students were less distracted by digital technologies during lectures. To our knowledge, there is thus far no research on the social role of smartphones in classrooms with younger learners. We might similarly delimit our findings in relation to the preconditions of digitalization in different parts of the world: The schools included in this study are highly digitalized, with digitalization extensively supported and promoted by Swedish educational authorities, and the students live highly connected private lives. These conditions may provide for the relatively unproblematic status of smartphones in these classrooms – although this, too, is an empirical question.

The incorporation of new forms of social interaction or cultural activity into an extant normative order is a slow business, and one that demands social negotiations, and trial and error. In our study, we found our participants to be engaging thoughtfully, constructively, and in good faith in such grounded policy enactment. We would encourage both scholars and the broader community of stakeholders in education to pay more attention to the details of how this still new technology finds its place in social life across national and cultural contexts, and, especially, to attend to the agency and reflexive capability of youth.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aagaard, Jesper. 2017. “Breaking Down Barriers: The Ambivalent Nature of Technologies in the Classroom.” New Media & Society 19 (7): 1127–1143. doi:10.1177/1461444816631505.

- Alexandersson, Kristina, and Pamela Davidsson. 2016. Eleverna och internet 2016 [The Students and the Internet 2016]. Stockholm: Internetstiftelsen.

- Amez, Simon, and Stijn Baert. 2019. Smartphone Use and Academic Performance: A Literature Review. IZA Discussion Paper Series 12723. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3483961.

- Amez, Simon, Suncica Vujić, Lieven De Marez, and Stijn Baert. 2021. “Smartphone Use and Academic Performance: First Evidence from Longitudinal Data.” New Media & Society. doi:10.1177/14614448211012374.

- Asplund, Stig-Börje, Christina Olin-Scheller, and Marie Tanner. 2018. “Under the Teacher’s Radar: Literacy Practices in Task-Related Smartphone Use in the Connected Classroom.” L1-Educational Studies in Language and Literature, 1–26. doi:10.17239/L1ESLL-2018.18.01.03.

- Baert, Stijn, Suncica Vujić, Simon Amez, Matteo Claeskens, Thomas Daman, Arno Maeckelberge, Eddy Omey, and Lieven De Marez. 2020. “Smartphone Use and Academic Performance: Correlation or Causal Relationship?” Kyklos 73 (1): 22–46. doi:10.1111/kykl.12214.

- Ball, Stephen J. 1997. “Policy Sociology and Critical Social Research: A Personal Review of Recent Education Policy and Policy Research.” British Educational Research Journal 23 (3): 257–274.

- Ball, Stephen J. 2006. “The Necessity and Violence of Theory.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 27 (1): 3–10. doi:10.1080/01596300500510211.

- Ball, Stephen J., Meg Maguire, and Annette Braun. 2012. How Schools Do Policy: Policy Enactments in Secondary School. London: Routledge.

- Beland, Lous-Phillipe, and Richard Murphy. 2016. “Ill Communication: Technology, Distraction & Student Performance.” Labour Economics 41: 61–76.

- Berg, Gunnar. 2018. Skolledarskap och skolans frirum. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Chen, Quan, and Zheng Yan. 2016. “Does Multitasking with Mobile Phones Affect Learning? A Review.” Computers in Human Behavior 54: 34–42. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.047.

- David, Prabu, Jung-Hyun Kim, Jared S. Brickman, Weina Ran, and Christine M. Curtis. 2015. “Mobile Phone Distraction While Studying.” New Media & Society 17 (10): 1661–1679. doi:10.1177/1461444814531692.

- Drotner, Kirsten. 1992. “Modernity and Media Panics.” In Media Cultures: Reappraising Transnational Media, edited by Michael Skovmand, and Kim Christian Schrøder, 42–63. London: Routledge.

- Forsman, Michael. 2014. Duckface/Stoneface: Sociala medier, onlinespel och bildkommunikation bland killar och tjejer, i årskurs 4 och 7. Stockholm: Statens medieråd.

- Hassoun, Dan. 2015. “‘All Over the Place’: A Case Study of Classroom Multitasking and Attentional Performance.” New Media & Society 17 (10): 1680–1695. doi:10.1177/1461444814531756.

- Kay, R., D. Benzimra, and J. Li. 2017. “Exploring Factors That Influence Technology-Based Distractions in Bring Your Own Device Classrooms.” Journal of Educational Computing Research 55 (7): 974–995.

- Kessel, Dany, Hulda Lif Hardardottir, and Björn Tyrefors. 2019. The Impact of Banning Mobile Phones in Swedish Secondary Schools. Working Paper Series 1288. Stockholm: Research Institute of Industrial Economics.

- Kuznekoff, Jeffrey, H. Stevie Munz, and Scott Titsworth. 2015. “Mobile Phones in the Classroom: Examining the Effects of Texting, Twitter, and Message Content on Student Learning.” Communication Education 64 (3): 344–365. doi:10.1080/03634523.2015.1038727.

- Lee, Seungyeon, Ian M. McDonough, Jessica S. Mendoza, Mikenzi B. Brasfield, Tasnuva Enam, Catherine Reynolds, and Benjamin C. Pody. 2021. “Cellphone Addiction Explains How Cellphones Impair Learning for Lecture Materials.” Applied Cognitive Psychology 35 (1): 123–135. doi:10.1002/acp.3745.

- OECD. 2016. Skills for a Digital World: 2016 Ministerial Meeting on the Digital Economy Background Report. OECD Digital Economy Papers No. 250. Paris: OECD. doi:10.1787/5jlwz83z3wnw-en.

- Olin-Scheller, Christina, Marie Tanner, Stig-Börje Asplund, Janne Kontio, and Peter Wikström. 2020. “Social Excursions During the In-Between Spaces of Lessons. Students’ Smartphone Use in the Upper Secondary School Classroom.” Scandinavian Journal of Education 65 (4): 615–632. doi:10.1080/00313831.2020.1739132.

- Olin-Scheller, Christina, Marie Tanner, and Anna Öhman. 2018. “Klassrummet som galleri – gymnasieelevers identitetsarbete i ett uppkopplat klassrum. KAPET.” In Berättelser. Vänbok till Héctor Péréz Priéto, edited by Olin-Scheller Tanner, and A. Löfdahl, 143–158. Karlstad: Karlstads universitet.

- Ott, Torbjörn. 2017. Mobile Phones in School: From Disturbing Objects to Infrastructure for Learning. Gothenburg: Gothenburg University.

- Redecker, Christine. 2017. European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators: DigCompEdu. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/digcompedu.

- Sahlström, Fritjof, Marie Tanner, and Verneri Valasmo. 2019. “Connected Youth, Connected Classrooms. Smartphone Use and Student and Teacher Participation During Plenary Teaching.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 21: 311–331.

- Scollon, Ron, and Susie W. Scollon. 2004. Nexus Analysis: Discourse and the Emerging Internet. London: Routledge.

- Scollon, Ron, and Susie W. Scollon. 2007. “Nexus Analysis: Refocusing Ethnography on Action.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 11 (5): 608–625. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9841.2007.00342.x.

- Selwyn, Neil, and Jesper Aagaard. 2021. “Banning Mobile Phones from Classrooms: An Opportunity to Advance Understandings of Technology Addiction, Distraction and Cyberbullying.” British Journal of Education Technologies 52: 8–19. doi:10.1111/bjet.12943.

- SFS (Svensk författningssamling). 2010. “800. Skollag. [Swedish Code of Statutes: Education Statute].”

- Singh, Parlo, Stephen Heimans, and Kathryn Glasswell. 2014. “Policy Enactment, Context and Performativity: Ontological Politics and Researching Australian National Partnership Policies.” Journal of Education Policy 29 (6): 826–844. doi:10.1080/02680939.2014.891763.

- Skolverket. 2016. It-användning och it-kompetens i skolan. Stockholm: Skolverket.

- Standage, Tom. 1998. The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century’s Online Pioneers. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Sveningsson Elm Malin. 2008. “Young People’s Gender and Identity Work in a Swedish Internet Community.” In The Future of Identity in the Information Society. Privacy and Identity 2007, edited by S. Fischer-Hübner, P. Duquenoy, A. Zuccato, and L. Martucci, 113–126. Boston: Springer.

- Utbildningsdepartementet. 2017. Nationell digitaliseringsstrategi för skolväsendet. Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet. https://www.regeringen.se/informationsmaterial/2017/10/regeringen-beslutar-omnationell-digitaliseringsstrategi-for-skolvasendet/.

- Valasmo, Verneri, Antti Paakkari, and Fritjof Sahlström. 2022. “The Device on the Desk: A Sociomaterial Analysis of How Snapchat Adapts to and Participates in the Classroom.” Learning, Media and Technology. doi:10.1080/17439884.2022.2067176.

- Willermark, Sara. 2018. “Technological Pedagogical and Content Knowledge: A Review of Empirical Studies Published from 2011 to 2016.” Journal of Educational Computing Research 56 (3): 315–343. doi:10.1177/0735633117713114.