ABSTRACT

This article analyzes the development, commercialization and demise of the Smaky school computer in French-speaking, Western Switzerland between 1973 and 1997. By examining archival material, I consider the connections between this locally assembled and used school computer, and the globally embedded economic developments during the period of investigation. I argue that, historically, the Smaky was both a product of and a response to the region’s economic crisis in the 1970s and early 1980s. Analytically speaking, I critically reflect on the seemingly contradictory categories of ‘global’ and ‘local’. Although these were politically effective among historical actors, they are of limited use in the historical analysis of digital educational technologies.

Introduction

For computer scientist Jean-Daniel Nicoud, there was no question as to why the Smaky, his brand of educational computers which were commercially produced between 1978 and 1997, eventually failed: ‘the Internet made the difference for Apple. Suddenly, you needed a team five times as big as before, but we did not have any financial aspirations’.Footnote1 Epsitec-System S.A., the company producing Nicoud’s Smaky, never used the brand’s success in the 1980s to significantly grow research and development (R&D), production, marketing and distribution. Instead, the strategy was to supply a manageable Western Swiss school market with a manageable Western Swiss team. This cost-covering strategy took its toll simultaneously to the breakthrough of the World Wide Web. After 1993, the year the Mosaic Web browser was launched and the dot-com bubble started to inflate, financially ambitious computer manufacturers expanded their workforce to grow with and profit from the new technology. Those who, like Epsitec, had deliberately focused on a local market, served by a small team, were displaced by companies such as Apple.

Undoubtedly, the emergence of the World Wide Web had implications for small-scale computer manufacturers such as Epsitec. However, the demise of this local edtech provider cannot be solely attributed to the World Wide Web as such a techno-deterministic explanations cannot fully account for the intricate and multifaceted nature of history. A new technological development is only one factor amongst others, perhaps favoring a certain outcome, but by no means determining it (MacKenzie and Wajcman Citation1985). To adequately tell the story of the Smaky and its eventual demise, we need to attend to the interaction of social, political and economic forces, as well as scientific and technological factors (Chandler Citation1995). Consequently, this account of the Smaky’s history illustrates that the mechanisms behind Epsitec’s demise were much more complex than Nicoud’s mono-causal reasoning suggests. And from today’s perspective of a computer market dominated by global oligopolists, the question also arises as to why a local company like Epsitec was able to successfully compete in the school market in Western Switzerland in the first place. After all, computer manufacturers like IBM, Norsk Data or Olivetti, and later Commodore, Atari or Apple were already strong, established competitors by the 1970s and 1980s, and expanding into international markets.

Accordingly, in this article, I address two simple questions: why was it possible for a local computer manufacturer in Western Switzerland in the 1970s and 1980s to become a main supplier to local primary and secondary schools, essentially only competing with Apple from the mid-1980s onward? And why, aside from the World Wide Web, did the Smaky disappear so quickly from schools in the first half of the 1990s? As I argue, these questions can only be answered by analyzing the Smaky both through a local and a global lens. Only by reconstructing how these two scales interacted do we understand the Smaky’s success against established products in the global market. And it was also their interaction that accounted for the company’s failure years later. Although this is not a case of global history, and the development of the Smaky computer in Western Switzerland is not contrasted with other computers elsewhere, the basic global-historical idea of studying concrete local phenomena as emerging from their global entanglements is still vital for my analysis (Bayly Citation2004).Footnote2

Historically speaking, the analysis adds to our understanding of the socioeconomic, political and cultural factors which contributed to the emergence, success and demise of educational computer manufacturers between the 1970s and 1990s. It suggests that the Smaky was both a product of and a response to the economic crisis, affecting several regions in the Global North in the 1970s and early 1980s, Western Switzerland being among them (chapter 1). Provided that the industrial crisis was acute, felt or remembered, it was possible for Epsitec to forge private-public partnerships with education policy makers and school administrators (chapters 2). As the region recovered, however, the regional computer manufacturer became less of a political priority. When the devaluation of the US dollar in the second half of the 1980s gave Apple a competitive advantage, the crisis was too far away to enforce effective political measures on a local level (chapter 3). Consequently, Epsitec folded (conclusion). This last point provides important clues as to the historical genesis of global oligopolists, such as Microsoft, Google or Apple, in relation to which the small local edtech providers of the late twentieth century tend to be forgotten.

Analytically speaking, I reflect on the seemingly contradictory categories of ‘global’ and ‘local’. While both are semantically significant and politically effective terms for actors in the field of digital edtech, they are of limited analytical use in terms of studying edtech providers and procurement (Macgilchrist, Potter, and Williamson Citation2021). This argument aligns with David Edgerton’s critique of ‘techno-nationalism’ and ‘techno-globalism’ (Edgerton Citation2007). According to Edgerton, the two concepts shed more light on the underlying assumptions and ideologies of technology analysts, consultants and politicians than on technological realities. Focusing on the local dimension, techno-nationalism is a perspective that emphasizes the connection between a nation’s technological strength and self-sufficiency and its national security, economic prosperity and social stability. Similarly, techno-localism sees technology as a tool to support local communities, economies and cultures. This may involve government procurement favoring domestic technology producers over foreign competitors for political reasons rather than purely economic rationale. The ‘Plan Calcul’, France’s first information technology program, launched by the de Gaulle government in 1966, is an example of techno-nationalism (Kuo Citation2022).

Techno-globalist accounts, on the other hand, emphasize the global entanglements of technological change and innovation. Microchip technology originated in the USA and was subsequently shared across national boundaries. From its inception, technological innovation in computing took place within global systems of innovation, embedded in national systems, and relied on cross-national knowledge transfer. Moreover, the development of microcomputers was often dependent on global supply chains, with local microcomputer manufacturers in Europe relying on imported microelectronic components. In this respect, the Smaky was no different from the computers produced by Acorn and Thomson in the UK, Olivetti in Italy or Siemens in Germany, which relied on microprocessors manufactured in the US (Zilog, Intel) or Japan (Motorola). Finally, national and local efforts to develop computer systems took place against the backdrop of a global economic market in which nations and their respective industries compete (Edgerton Citation2007, 14).

The Smaky computer is an example of how these two ideological frameworks are bridged in concrete historical developments. The Smaky emerged and vanished in a web of cultural, economic and social connections which spanned beyond local boundaries. This study is a first attempt at retracing the Smaky’s ‘glocal’ entanglements. To do so, I concentrate on Western Switzerland only. While Switzerland consists of 26 politically autonomous cantons with four different languages,Footnote3 the headquarters of Epsitec-System S.A. was located in francophone Western Switzerland. The Smaky computer explicitly targeted the francophone Western Swiss market and was most widely used in Western Swiss schools. Consequently, the article is based on historical material of the cantonal departments of education from the archives of Vaud, Fribourg, Geneva, Neuchâtel and Jura. The material consists of reports and minutes from commissions that were responsible for the introduction of computer education; correspondence between these commissions and people supporting or working for Epsitec; and newspaper articles and literature on microcomputers and computer education read and archived by commission members.

1. Transatlantic computer entrepreneurship after the boom, 1973–1978

The year 1973, when this story of the Smaky begins, was particularly grim. The oil price crisis heralded the worst recession in the Global North since the end of World War II. Just two years before, the Bretton Woods international monetary system, which had contributed to stable growth rates in the Western industrialized nations since 1944, had collapsed (Tanner Citation2015, 449). Together with the fundamental changes in industrial production, the two events would soon come to mark the beginning of a period of crisis characterized by low growth rates, economic fluctuation, inflation, plant closures and high unemployment (Doering-Manteuffel and Raphael Citation2012; Raphael Citation2019). In Europe, Switzerland was hit hardest by the crisis. Of the four linguistic regions, highly industrialized francophone Switzerland with its machinery, metal and food industries was most severely affected by the maelstrom of the global economic downturn from 1975 onward. Like the US Rust Belt, the north of England or the German Ruhr area, the territory in Western Switzerland was facing ‘deindustrialization’. Plant closures, unemployment and population decline negatively affected the area steeped in a tradition of watchmaking, textile production and precision engineering. In the media, the buzzwords ‘watchmaking crisis’ was circulating to describe these multi-layered developments (Donzé Citation2011, 125).

For Nicoud, however, 1973 looked much brighter. It marked the year that the computer scientist behind the Smaky received his first professorship. The former physics and math teacher was entrusted with the management of the new Digital Calculator Lab (DCL) at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (EPFL) in Lausanne, Western Switzerland. Due to his lack of experience in industry, Nicoud first had to complete a research stay with a computer manufacturer.Footnote4 In 1973, Nicoud thus visited the Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) in Maynard, Massachusetts. In the 1970s, DEC was the market leader in the computer industry alongside IBM and Univac. Impressed by the microelectronic devices Nicoud had built, DEC’s Gordon Bell invited him to Massachusetts to define a project for Nicoud’s research stay. They agreed for Nicoud to work on his Portable Computer System (PCS) between March and July of 1974. Nicoud used the time and money at DEC to produce the first three non-commercial iterations of the Smaky (Smart Keyboard) in 1975/76 ().Footnote5

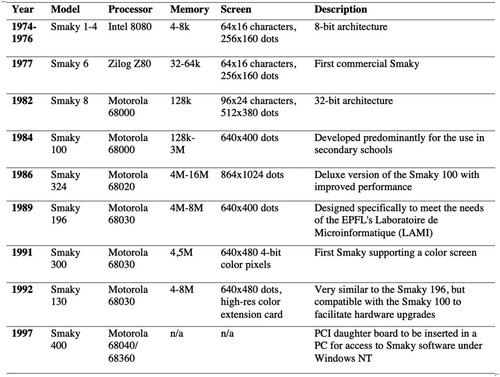

Figure 1. The Smaky models (see Nicoud Citation2011b).

While internationally operating companies, such as DEC, became active with targeted investments in computer developers like Nicoud, the Swiss Confederation stepped in on a structural scale. Between 1978 and 1982, it invested approximately 80 million Swiss francs into the Impulse Program I (Geiss Citation2016). The program contributed to the industrial revitalization and ‘diversification’ of Switzerland by strengthening training as well as R&D.Footnote6 Besides bolstering software production for industrial control systems through the foundation of the Software School Switzerland, Western Swiss companies were encouraged and supported in their development of microelectronic components and products.Footnote7 Since the argument was repeatedly raised that anyone who could manufacture delicate watches should also be able to produce microelectronic components, electronic watch components took center stage in the program. This economic rejuvenation was accompanied by two National Research Programs.Footnote8 They were designed to help understand Western Switzerland’s struggles over ‘deindustrialization’, while the impulse program was aimed at mitigating these. The development of the Smaky was, therefore, not an isolated undertaking by a visionary developer. Rather, it took place against the backdrop of state-funded research programs and economic development initiatives aimed at fostering a microelectronic industry in Western Switzerland.

To produce the Smaky commercially, Epsitec-System S.A. was founded at the beginning of 1978 in the Nicoud family home.Footnote9 From the perspective of Epsitec, it was clear that their market would be neither one for industrial nor home computers. The R&D, production and marketing possibilities of the fledgling company were too limited for that purpose.Footnote10 However, due to developments in education policy, a market nevertheless opened up. Since the late 1960s, individual mathematics and physics teachers had been offering computer education in general education schools. Since these classes were not coordinated by the departments of education and relied on expensive mainframe infrastructures hosted by universities, they were often solely offered in university cities (Fassa Citation2005; Felder Citation1987). In the wake of the economic crisis of the 1970s, businessmen, politicians and pedagogs called for a more coordinated implementation of computer education within the curriculum. The 24 h of Informatics program of 1978, developed and published by the Swiss Conference of Cantonal Ministers of Education (EDK/CDIP), constituted the first step in that direction. In the future, upper secondary students throughout Switzerland were to attend at least 24 h of computer education before graduation.Footnote11

For Epsitec, this opened up an appropriate market. For one thing, it made sense for schools to decentralize computer education by transitioning to the emerging microcomputers, rather than continuing with mainframes to implement the 24 h of Informatics program. After all, teaching that relies on external infrastructure is a challenge for schools. Furthermore, schools were stable customers who valued personal exchange with developers based on trust. Large global companies were met with suspicion, especially in these early days of computer education, and it often seemed unclear to teachers whether they were concerned about the students or simply profit.Footnote12 Additionally, the school market in Western Switzerland was sufficiently isolated for Epsitec to exploit its locational advantage: US, Scandinavian, English or German products would find it difficult to gain a foothold in schools because of the language barrier and French products were less well received by politicians and teachers due to the alleged cultural differences. As mentioned in the introduction, centralist France had introduced the minicomputers of Mitra and Télémécanique top-down, which, according to protectionist Swiss politicians and teachers, contradicted the federalist bottom-up spirit of Switzerland (Stamm Citation1978b). Epsitec, on the other hand, was able to offer French-language equipment and support as well as present itself as an affable local company whose values harmonized with the decentralized and self-determined local school culture.

Indeed, it was an order from a school in 1978 that allowed Epsitec to go into production. In 1978, Epsitec presented the fifth iteration of the Smaky (Smaky 6) at the IMMM computer fair in Geneva to identify a ‘promoter’ willing to invest in the device’s production (Stamm Citation1978a). Epsitec found what it was looking for in Raymond Morel, the teacher in charge of the Computer Center for Geneva’s Upper Secondary Schools (CCEES-GE) and president of the national IT Coordination Group, which had drafted the 24 h of Informatics program. At the time, Morel was decentralizing computer education (Felder Citation1987, 37). Classes continued to be held using the central Norsk Data computer at the CCEES-GE, which was located at Collège de Calvin (CC) where Morel himself taught. However, thanks to connecting lines and terminals, students were increasingly able to access the central computer from their own school via time-sharing.Footnote13 As the Smaky could be used not only as a stand-alone but also as an ‘intelligent terminal’, Morel ordered six units worth over 22,000 Swiss francs from Epsitec (Renaud Citation1979). In tandem, the Smaky 6s and the Norsk Data Computer were to provide the CC’s 350 students with optional computer education, as conceptualized in the 24 h of Informatics program (Stamm Citation1978b).Footnote14 Epsitec thus entered the school market because of schools using the Smaky as a terminal, which subsequently, was able to be used as a stand-alone.

When Nicoud took up his professorship at EPFL’s LCD in 1973, the future in Western Switzerland appeared bleak in the face of the looming crisis. In an attempt to find an answer, Western Switzerland took education to task. Policymakers and school officials saw the crisis as an opportunity to transform the industry, the job market and even society and culture as a whole through education.Footnote15 Thanks to computer education, students should learn the skills needed for a successful career and a prosperous life in a ‘post-industrial society’, as society was being reimagined at the time (Bell Citation1973).Footnote16 This educational focus had resultant effects on the region’s industrial imaginaries. In a region that was proficient in producing small parts, why not manufacture parts for a computer industry (Jeannet Citation1984)?Footnote17 DEC, EPFL, Nicoud and Epsitec benefited from this train of thought and launched the Smaky as a techno-utopian organism in a region that had seemingly become inhospitable as regards industry.Footnote18 Commercialization, in turn, became possible when schools opened up as an appropriate market over the course of the 24 h of Informatics program of 1978: not too small, not too big and, above all, stable. Consequently, by 1978, the world appeared considerably more friendly: with the Impulse Program I, the associated National Research Programs, the introduction of computer education and the first contract for Epsitec, there seemed to be a future for Western Switzerland even ‘after the boom’ (Doering-Manteuffel and Raphael Citation2012).

2. The emergence of a united school computer market and its main supplier, c. 1980

With schools, Epsitec had bet on the right buyer. After the introduction of the 24 h of Informatics program and the beginning of decentralization of educational IT-infrastructures, the company received further orders from the two most populous cantons of Geneva and Vaud. With a total of 880,000 inhabitants, the two cantons accounted for almost 60% of the total population of Western Switzerland in 1980 and thus were crucial in introducing the Smaky to a wider audience. In the 1979/80 school year, Geneva ordered an additional 12 Smaky 6s for 10 secondary schools (Morel Citation1981, 2).

Epsitec benefited from two technology policy measures. Firstly, from 1979 onwards, the Interdepartmental Informatics Commission of the Canton of Geneva (CIDI) had decided only to finance microcomputers, rather than time-sharing infrastructures.Footnote19 Secondly, the canton was concerned with limiting the number of brands in schools. As an ‘intelligent terminal’, which could be used both as a terminal and a microcomputer, the Smaky 6 was perfect for navigating the transition from centralized to decentralized school computer infrastructures. Moreover, as a local supplier of quality products, it was easy to agree on the devices from Epsitec to reduce the number of brands in use (Morel Citation1981, 4).

In the canton of Vaud, the situation was different but no less advantageous for Epsitec. When the first Smaky 6s were about to be installed in Geneva’s upper secondary schools around 1980, Vaud was focusing its educational policy on lower secondary schools (Desgraz Citation1980). Unlike in upper secondary schools, little had changed in lower secondary schools in terms of computer education. In 1980, the Cantonal Commission for Computer Science of the Department of Education (CCI-VD), responsible for computer education in public schools, instructed the lower secondary schools to each appoint a computer officer by November of the same year (Bovet et al. Citation1985, 23; Desgraz Citation1980, 10). These computer officers were to advise their principals on the purchase of computers and the organization of computer courses for teachers. In addition, the CCI-VD tasked the computer officers with enforcing a transitional hardware solution in their schools. Until schools acquired their own equipment, they had to work with Smakys lent by the Vaud Centre for Pedagogical Research (CVRP) (Desgraz Citation1980, 8). Since EPFL invested considerable resources in the training computer education teachers, it always had its representatives in the CCI-VD and its subcommittees. These helped to emphasize in the commission the ‘convergence of interests’ between EPFL, its spin-off Epsitec and schools, eventually leading to the Smaky becoming the interim solution for lower secondary schools.Footnote20 Once the CCI-VD and the CVRP had set the course in favor of Epsitec, the ‘path-dependent’ nature of procurement practices would do its part (David Citation1985).

School development in Switzerland is decentralized (federalism) and must operate at the lowest possible organizational level (subsidiarity) (Hega Citation2000). In theory, this would have allowed school districts to decide independently about their IT equipment. In practice, however, it was a matter of negotiation to decide on what the lowest possible organizational level was. In the case of computer education in Vaud, the cantonal governing bodies saw the competences with themselves and decided that transitional computers in all of Vaud had to be Smakys; therefore, a preliminary decision guiding future procurement had already been made. In Geneva, when Morel took the decision to reduce the number of brands in schools in favor of Smaky, this also deprived the school districts of their decision-making authority and put Epsitec in an advantageous position. Paradoxically, federalism and subsidiarity allowed for the creation of a united regional school market for microcomputers in the first place, while at the same time positioning Epsitec as its main supplier. In these two cases, then, federalism and subsidiarity neither lead to complete freedom of choice for school districts nor to a free market for school computers. Instead, they resulted in a powerful private-public partnership.

Switzerland has a long-standing political tradition of private-public partnerships (Eichenberger and Mach Citation2011) of which the rise of the Smaky is a pertinent example. Neo-corporatist arrangements play a vital part in the provision of public services by dividing labor between public and private enterprises, as well as in the implementation of policies, in market regulation, and the organization of vocational education (Ladner Citation2019, 10). The close cooperation between Epsitec and local public authorities functioned within the logic of this tradition. This is remarkable in that the product of global economic upheaval and investment was now relentlessly profiting from local political-economic traditions. Because an agreement was reached between Epsitec and local school authorities on a private-public partnership, a small but relatively united school computer market emerged in western Switzerland. Although decentralization and subsidiarity are supposed to prevent the formation of monopolies, the effect was paradoxically comparable to France: In the early 1980s, students in Western Switzerland could hardly get around the Smaky. From an entrepreneurial perspective, the Nicouds, EPFL and Epsitec had pragmatically and skillfully switched between the global and the local scale to first develop and then market their microcomputer between 1973 and 1980.

3. Smaky versus Apple, 1986–1990

By the mid-1980s, Switzerland was recovering from the economic and industrial upheavals of the previous decade. Regarding Western Switzerland, it appeared that the region had not only survived the crisis of the secondary sector but thanks to companies such as Logitech, Valtronic and Epsitec, research institutes like the Centre Suisse d’Electronique et de Microtechnique (CSEM) in Neuchâtel, universities such as EPFL and a broad IT initiative in schools, the region would become a similarly successful economic player in the computer age as it had been in the industrial age. In the spring of 1986, the magazine, Nouvelles informatiques, even reported on the emerging ‘Silicon Vallée’ (Jeanmonod Citation1986, 1).

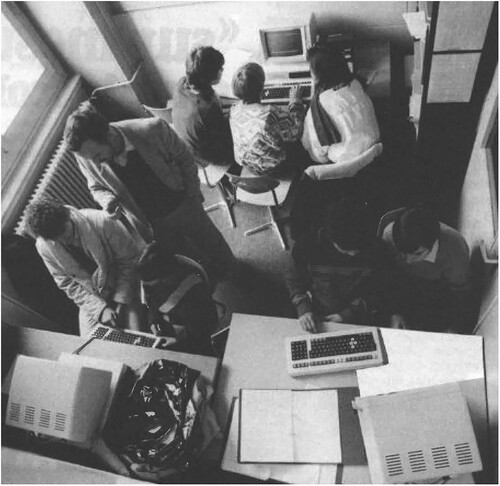

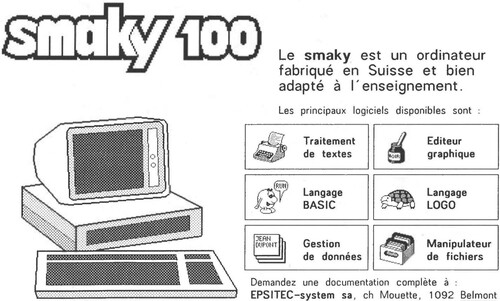

One element of this emerging ‘Silicon Vallée’ was the production of software. Educational software was largely based on the work of teachers, who benefitted from PROF, a so-called ‘author language’. Developed in 1986 by Denis Dumoulin, a part-time employee of Epsitec, PROF was a graphical flowchart editor. A single flowchart represented the whole lesson, while the nodes represented the units. The nodes of the flowchart were filled with visual, audio or text material and a task; each node anticipated an answer that the programmer had stored. The program had a test mode that allowed teachers to try out parts of their programs to debug them (Smaky News Citation1986). More complex software, such as the four basic applications (word processing, drawing, spreadsheet and database software), was commissioned and paid for by the Vaud Department of Education (DIPC-VD) and produced by Epsitec (Bettex Citation1990; Fornerod Citation1990). In terms of hardware, the Smaky 100, released to schools in 1985/86, was crucial to software production because it struck the balance between price and performance (see ). Thus, teachers could afford the microcomputer and participate more easily in software production. ()

Figure 2. Seven secondary students and one teacher working with three Smaky 100s in Neuchâtel around 1985 (Bovet et al. Citation1985, 13).

Figure 3. Advertisement for the Smaky 100 from 1985 stating: ‘The Smaky is a computer manufactured in Switzerland and well adapted for education.’ (Bovet et al. Citation1985, 7).

To the outside world, these developments conveyed a positive image of Western Switzerland’s microcomputer industry. Behind the scenes, however, problems started to arise. In the canton of Vaud, disputes between users and representatives of the Smaky on one side and the DIPC-VD on the other intensified from 1986 onwards. The initial debate centered on whether the DIPC-VD was inciting those schools that had purchased Smakys to migrate to the Macintosh (Fornerod Citation1990). In doing so, the DIPC-VD would have violated the 1985 subsidy decision, which guaranteed communities a free choice between Smaky and Apple, ensuring equal treatment of the two products. While the Group of Instructors and Administrators Using the Smaky Microcomputer (GARUMS) blamed the alleged overrepresentation of Apple fans in the DIPC-VD, who reportedly ran an ‘anti-Smaky campaign’ (Fornerod Citation1990; Montagrin Citation1988a; Citation1988b), the Department of Education took the view that free market forces were at play and that the Smaky was gradually losing ground because it could not keep up with the Macintosh. Based on the archival material within my possession, I was unable to ascertain whether the accusations of the ‘Smakyists’ in relation to the DIPC-VD were justified (Fornerod Citation1990). What I can recount, however, is that the Smaky’s loss of ground from 1986 onwards was associated with a drastic shift in the global financial system.

The original subsidy scheme of the DIPC-VD provided for a fixed amount of 3,000 Swiss francs for each microcomputer. The education department had decided against percentage subsidies to ensure budgetary planning security. Provided that the financial conditions were such that Epsitec could keep up with the prices of foreign producers, this subsidy mode was acceptable to all stakeholders. However, this approach drastically changed in September 1985, when the finance ministers of the G5 (France, West Germany, UK, Japan and the US) signed the Plaza Accord in New York City to depreciate the US dollar (Donzé and Fujioka Citation2015). As Motorola’s annual report of 1984 argued, ‘U.S.–based manufacturers, notably including electronics companies’, had suffered from the rapid and perpetual appreciation of the US-dollar since 1980.Footnote21 Due to the currency’s strength, they struggled to perform internationally. The Plaza Accord of 22 September 1985 responded to these struggles by intervening in currency markets to put an end to the steep climb of the dollar exchange rate.

For schools in Western Switzerland, this intervention on the foreign exchange market meant that it no longer made sense to buy Smakys. Granted, this was a quality product, was developed and assembled locally, used the French language and had a small but vibrant community of software producers; but with the Apple Macintosh, schools were now getting an equally good or a slightly better microcomputer at a lower price. In 1990, a Smaky cost twice as much as a Macintosh (however, in contrast to Apple’s offer, the purchase price of the Smaky included the software).Footnote22 Therefore, even if the DIPC-VD were dominated by Apple fans, the Smaky’s chances of survival had deteriorated primarily because of the politically managed devaluation of the US dollar on a global scale.

The DIPC-VD acknowledged the sudden market advantage for Apple and addressed it with a new local subsidy model (Montagrin Citation1988b). In 1987, the dollar exchange rate was so low that the price of a Macintosh had fallen below 3,000 Swiss francs, meaning that schools theoretically received money from the canton when they bought a Macintosh (Fornerod Citation1990). Although I was unable to verify claims that this took place, schools were given Macintosh computers free of charge by 1987. The question was therefore raised in the media whether Switzerland would be the first European country to no longer have an ‘indigenous product’ in schools and whether the canton of Vaud, of all places, would lead the way in ousting its own ‘local product’ (Dubois Citation1986). To prevent this, Vaud took the decision to switch to a hybrid subsidy model (Bettex Citation1990). Each computer was now subsidized by 50%, with a maximum contribution of 3,000 Swiss francs.

Even though schools from then on no longer theoretically received money for the purchase of Apple computers, the new subsidy model could not compensate for the Macintosh’s price advantage. Notwithstanding software, the Macintosh’s net purchase price remained lower than that of a Smaky and GARUMS feared the complete removal of subsidies for the Smaky (Montagrin Citation1988b). According to its 1988 report, those teachers who had embraced IT with the Smaky were losing their enthusiasm for computer education. They feared that they would have to become acquainted and learn to teach with a new brand after only a couple of years (Montagrin Citation1988b). Moreover, GARUMS warned of the loss that the Smaky – the ‘pride of the Vaudois’ – represented ‘in terms of the technological genius of Vaud’. Sooner or later, there would be no ‘computer made in our canton’ – a fact that, unlike today, was unimaginable at the time (Montagrin Citation1988a; Citation1988c). However, in view of the upheaval on the global foreign exchange market, slightly adjusting the subsidy model turned out to be futile, and so tensions in the school market as regards computers continued to rise.

During the first round of renewal and supplementation of computer equipment in Vaud schools in 1990, the dispute between Smaky users and Epsitec, on the one hand, and the DIPC-VD, on the other, flared up again. The reason for this was the DIPC-VD’s practice of replacing obsolete equipment of any brand with a Macintosh if the school so desired. This foreshadowed the fact that the ratio of Macintosh to Smaky, which in Vaud in 1990 was 5–1 or 1,000–200 computers, would shift even more in favor of Apple (Montagrin Citation1990a). Since it had specifically developed the Smaky 300, a cost-effective device for schools, the situation was especially frustrating for Epsitec. Understandably, the company interpreted the practice as a ‘free exchange’ to secretly enforce Apple products (Montagrin Citation1990b), while Smaky users saw this as the logical consequence of a ‘one-sided information policy’ of the DIPC-VD in favor of the Macintosh (Pralong Citation1990). GARUMS, therefore, proposed that all schools equipped with only one brand should be required to purchase the equipment of the other brand. However, this would have violated the 1985 procurement decision, which prohibited the DIPC-VD from interfering with the decision-making authority of the individual municipalities (Bettex Citation1990). By 1990, it became apparent that the Smaky would not receive enough political support from both the cantonal and federal authorities to withstand the competition from Apple. By now, the small, modest school computer could no longer – and no longer needed to – fulfill its function as a beacon of hope for a beleaguered region, which it had been able to do in the 1970s and early 1980s. For one thing, it was clear by now that the days of European microcomputer manufacturers were numbered.Footnote23 And for another, the positive development of GDP since 1984 suggested that this would not stand in the way of a prosperous future for Switzerland. Thus, over the next few years, the Smaky lost its home market in Vaud, a setback from which it was unable to recover.

Conclusion, 1991–1997

Just how inhospitable the climate had become for the Smaky in schools in Western Switzerland was demonstrated by the launch of the Smaky 196 in 1991. The latest Smaky had been exclusively developed with Nicoud’s laboratory at EPFL in mind rather than schools. In 1992, the last complete machine from Epsitec followed, the Smaky 130. Subsequently, production was no longer worthwhile because the cost of the components equaled the price of the final computer. However, as the Smaky 130 was also available as a processor card, compatible with the Smaky 100, Epsitec claimed it sold around 2,000 units of the 1992 model. Due to the success of the Smaky 130, the model 400 from 1996 was produced exclusively as a processor card. It could be installed in most PCs via PCI bus. However, success failed to materialize with only 200 units sold, and so the Smaky brand came to an end in 1997.Footnote24 According to its own accounts, Epsitec sold a total of 4,000 Smakys between 1978 and 1997; 50% of these devices went to schools.

In the field of education, Epsitec had been engaged in a rearguard action since the early 1990s. After it became clear that educational politicians and school bureaucrats were not willing to counter Apple’s newly gained price advantage, Smaky users tried to nestle in the Apple ecosystem. Since the offering of the Palo Alto manufacturer’s software far exceeded that of Epsitec, Smaky users tried to spread the new emulator for Apple software, which had been sold in schools since 1988/89 (Bettex Citation1990, 4; Fornerod Citation1990, 9). The emulator capable of running Apple software on a Smaky and vice versa was intended to strengthen the position of the Epsitec brand by giving Smaky users access to software for Apple devices for which the Federal Office for Education and Science (OFES/BBW) had already paid (Montagrin Citation1990a, 3). In doing so, however, the ‘Smakyists’ involved the lawyers of Apple and its distributors. They considered this practice ‘illegal’ and threatened the schools with legal consequences (Montagrin Citation1990b, 1). Fearing Apple, education departments, in turn, threatened schools with legal consequences for ‘piracy’ (Fornerod Citation1990, 4). The issues raised by the emulator dispute in the legal gray area of software licenses and their special status in schools are worthy of their own legal-historical investigation, which I cannot provide. What is clear, however, is that the schools were unwilling to take legal risks and backed down to Apple’s threats. With the comparatively high price for hardware and the limited software offer, the fate of the Smaky was sealed.

As I have argued, this fate was not the result of quasi-natural, inevitable developments. Explanations such as Nicoud’s which blame the winning technology (e.g., the Internet) or its location (e.g., Silicon Valley) for the demise of the losing technology (e.g., the Smaky) are tempting. However, besides being tautological, they do not do justice to the messiness, complexity and contingency of technological life cycles. In the case of the Smaky, many minor decisions, developments and incidents contributed to its demise: school administrators were seduced by the flagship product from the Golden State’s computer hub, not realizing the consequences it would have on the fragile microcomputer industry in their own region; during negotiations with Apple, the responsible federal agency, OFES/BBW, seemed unwilling to stipulate in the contract that Apple software be used with an emulator; under the guise of freedom of choice for local schools (i.e., subsidiarity), the cantonal education departments did not intervene in the procurement process in favor of the local Smaky and when the G5 actively devalued the dollar in the second half of the 1980s, the Swiss Confederation took no action to protect the local microcomputer. In that sense, it was not a particular technology like ‘the Internet’ or a supposedly unstoppable business hub like ‘Silicon Valley’ that broke the Smaky’s back, but a host of unassuming and local human decisions that, embedded in politics, economics, society and pedagogy, undermined the Smaky over the years.

The same is true of the emergence and establishment of the Smaky in the 1970s and 1980s. Even if, with reference to the industrial age, the sources repeatedly speak of the technological proclivity of Vaud, the Smaky’s history implies that the reasons for its success were more complicated. The development of the Smaky began at a time when the structural break of the 1970s hit Western Switzerland hard. Faced with major problems in conventional industry, it was worthwhile for the EPFL, DEC and Nicoud to invest in a ‘new technology’. In this sense, the Smaky was a product of the watchmaking crisis. As a techno-utopian device, the Smaky also benefited from the notion that computers would make Western Switzerland fit for the ‘post-industrial age’. It was thus also a response to the structural break. Overall, the Smaky stood for a forward-looking and cosmopolitan local patriotism that succeeded in recruiting regional schools as partners. Therefore, although the categories, ‘local’ and ‘global’, developed clout in the political negotiations and media disputes of the time, the historical perspective suggests treating these scales as entangled when considering the development, establishment and demise of a digital educational technology such as the Smaky.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for Carmen Flury and Rosalía Guerrero Cantarell's help in revising this article. I also would like to thank Barbara Hof, Patricia Ferrante and the two reviewers for their feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Jean-Daniel Nicoud - Citation50e EPFL Citation2019, 16:01.

2 In The Birth of the Modern World, Christopher Bayly writes: ‘[A]ll local […] histories must […] be global histories.’ (Citation2004, 2).

3 Within Switzerland’s federal political structure, each of the 26 cantons has its own parliament, executive, court system, and constitution. The cantons implement policies determined at the national level, but they have a considerable degree of freedom in doing so. This decentralized approach grants the cantons the autonomy to organize certain sectors, such as education and cultural affairs, according to their specific needs and preferences (Ladner et al. Citation2019; 13–14).

4 J.-D. Nicoud and Fondation Mémoires Informatiques Citationn.d.

5 ‘Offre Smaky Citation100 concernant l’équipement informatique des établissements scolaires vaudois’ Citation1985; 1.

6 ‘Vorschläge zur wirtschaftlichen Stärkung des Juraraumes’ Citation1983; 34–35.

7 Ld Citation1978.

8 ‘NFP Citation05 “Regionalprobleme in der Schweiz, namentlich in den Berg- und Grenzgebieten”’ n.d.; ‘NFP Citation10 “Bildung und das Wirken in Gesellschaft und Beruf”’ n.d.

9 ‘Epsitec-System S.A.’ Citation1978.

10 ‘Offre Smaky Citation100 concernant l’équipement informatique des établissements scolaires vaudois’ Citation1985; 1.

11 ‘L’introduction de l’informatique dans l’enseignement secondaire’ Citation1978.

12 ‘Informatique et scolarité obligatoire. Rapport du groupe’ Citation1985, 1.

13 For a history of educational time-sharing, see Rankin Citation2018.

14 For the time being, the other Geneva upper secondary schools had to make do with outdated HP 9100s, 9810s and 9830s from the late 1960s and early 1970s, respectively, as terminals. See ‘Recapitulation des demandes en microsystèmes pour satisfaire les besoins des etablissments secondaires’ Citation1979.

15 On education becoming an instrument of economic policy, see Paoli Citation2017.

16 For the same train of thought in the US, see Cain Citation2021, 145.

17 Nicoud himself made the connection between manufacturing computers and watches: ‘[A] hundred years ago […] I would have become [sic] a watchmaker, clearly’ (Nicoud Citation2011a).

18 For reformist techno-utopianism and educational technologies, see Ames Citation2019; Cuban Citation2001, 12–20.

19 Since the canton had invested 800,000 Swiss francs in this infrastructure between 1971 and 1978, mainframes and terminals were still used; consequently, the equipment would not be updated (Morel Citation1981; 1).

20 “Procè-verbal no Citation37. Séance du lundi Citation26 septembre Citation1983, au Gymnase de Chamblandes” Citation1983, 2.

21 ‘Annual Report Citation1984’ Citation1985.

22 Fornerod Citation1990; Montagrin Citation1988b; ‘Avant-projet informatique – février Citation1990. ‘Avant-projet informatique – février 1990. Groupement d’assistence et de développement pour les enseignants utilisant le Smaky’ 1990.

23 “Am Rande eines Desasters” Citation1991.

24 The Smaky shared its fate with other European products and manufacturers. Nixdorf had been dissolved in 1990; Bull was gradually privatized from 1995 onward; and Olivetti sold its PC branch in 1997.

References

- Ames, Morgan G. 2019. The Charisma Machine: The Life, Death, and Legacy of One Laptop Per Child. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- “Am Rande eines Desasters”. 1991 Der Spiegel, 7. April 1991, Accessed May 2, 2023, https://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/am-rande-eines-desasters-a-d9039d25-0002-0001-0000-000013488406.

- “Annual Report 1984”. 1985. Motorola Inc. (After Nixdorf was dissolved in 1990, the German magazine Der Spiegel now reported serious problems at the other European manufacturers as well: Philips in the Netherlands, Bull in France, Schneider in Germany and Amstrad in England. “Am Rande Eines Desasters” 1991).

- “Avant-projet informatique – février” 1990. Groupement d’assistence et de développement pour les enseignants utilisant le Smaky.” Commission NTI/CDIP. pp. 953–115. Archives cantonales vaudoises. Unpublished archival source.

- Bayly, Christopher Alan. 2004. The Birth of the Modern World, 1780-1914: Global Connections and Comparisons. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Bell, Daniel. 1973. The Coming of Post-Industrial Society. A Venture in Social Forecasting. London: Heinemann.

- Bettex, François. 1990. “Réponses aux observations faites par EPSITEC relativement à la politique du département en matière d’informatique.” Lausanne: Département de l’instruction publique et des cultes. pp. 146/373. Archives Cantonales Vaudoises.

- Bovet, Jean-Claude, Raymond Morel, Julien Fonjallaz, Jean-François Emmenegger, Diego Erba, Joseph Guntern, Claude Robert-Tissot, Daniel Amiguet and Jean-Marie Boillat. 1985. “Dans les cantons … situation et tendances actuelles.” Coordination. Bulletin Conférence intercantonale des Chefs des départements de l'instruction publique de la Suisse romande et du Tessin 27 (Mai/Juin): 3–25.

- Cain, Victoria. 2021. Schools and Screens. A Watchful History. Cambridge, MA, London: MIT Press.

- Chandler, Daniel. 1995. “Technological or Media Determinism.” Aberystwyth University. http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/tecdet/tecdet.html (9.3.2023).

- Cuban, Larry. 2001. Oversold and Underused: Computers in the Classroom. Cambridge, MA, London: Harvard University Press.

- David, Paul A. 1985. “Clio and the Economics of QWERTY.” Papers and Proceedings of the Ninety-Seventh Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association 75 (2): 332–337.

- Desgraz, Claude. 1980. “Introduction de l’informatique dans l’enseignement secondaire inférieur.” SB 312 B 189. Archives Cantonales Vaudoises.

- Doering-Manteuffel, Anselm and Lutz Raphael. 2012. Nach dem Boom. Perspektiven auf die Zeitgeschichte Seit 1970. 3. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Donzé, Pierre-Yves. 2011. History of the Swiss Watch Industry. from Jacques David to Nicolas Hayek. Bern: Peter Lang.

- Donzé, Pierre-Yves, and Rika Fujioka. 2015. “European Luxury Big Business and Emerging Asian Markets, 1960–2010.” Business History 57 (6): 822–840. doi:10.1080/00076791.2014.982104

- Dubois, Claudine. 1986. “Les démangeaisons des puces savantes.” 24 heures, April 21, 1986, sec. Lausanne – Vaud.

- Edgerton, David E. H. 2007. “The Contradictions of Techno-Nationalism and Techno-Globalism: A Historical Perspective.” New Global Studies 1(1). doi:10.2202/1940-0004.1013

- Eichenberger, Pierre, and André Mach. 2011. “Organized Capital and Coordinated Market Economy: Swiss Business Interest Associations Between Socio-Economic Regulation and Political Influence.” In Switzerland in Europe. Continuity and Change in the Swiss Political Economy, edited by Christine Trampusch, and André Mach, 61–81. Abingdon: Rotledge.

- “Epsitec-System S.A”. 1978. Schweizerisches Handelsamtsblatt 96 (40): 503.

- Fassa, Farinaz. 2005. Société en mutation, école en transformation : le récit des ordinateurs. Lausanne: Payot

- Felder, Dominique. 1987. “La Scolarisation de l’informatique à Genève.” 22. Cahiers du Service de la recherche sociologique. Genève: Service de la recherche sociologique.

- Fornerod, Pierre. 1990. “Informatique dans l’enseignement secondaire inferieur. ‘Gueguerre’ Macintosh – Smaky.” Société pédagogique vaudoise. pp. 953–115. Archives cantonales vaudoises.

- Geiss, Michael. 2016. “Sanfter Etatismus: Weiterbildungspolitik in der Schweiz.” In Staatlichkeit in der Schweiz: Regieren und Verwalten vor der neoliberalen Wende, edited by Lucien Criblez, Christina Rothen and Thomas Ruoss, 219–246. Zürich: Chronos.

- Hega, Gunther M. 2000. “Federalism, Subsidiarity and Education Policy in Switzerland.” Regional & Federal Studies 10 (1): 1–35. doi:10.1080/13597560008421107

- “Informatique et scolarité obligatoire. Rapport du groupe”. 1985. GISO. République et Canton du Jura. IPP 78. Archives cantonales jurassiennes.

- Jean-Daniel Nicoud - 50e EPFL. 2019. Musée Bolo. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Oxu638GCtU.

- Jeanmonod, Denise. 1986. “L'informatique romande: de Plan-les-Ouates à Corcelles en passant par la Vallée de Joux.” Nouvelles Informatiques 4 (April): 1.

- Jeannet, Alain. 1984. “Un pionnier dans la Vallée.” L’Hebdo, November 29, 1984, sec. Economie.

- Kuo, Laureen. 2022. “Plan Calcul: France's National Information Technology Ambition and Instrument of National Independence.” Business History Review 96 (3): 589–613. doi:10.1017/S0007680521000441

- Ladner, Andreas., et al. 2019. “Society, Government, and the Political System.” In Swiss Public Administration. Governance and Public Management, edited by Andreas Ladner, 3–20. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ld. 1978. “Impulsprogramm – für die Wirtschaft oder für den Delegierten?” Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 23.4 1978, sec. Wirtschaft.

- “L’introduction de l’informatique dans l’enseignement secondaire”. 1978. 13. Bulletin d’information. Genève: Conférence suisse des directeurs cantonaux de l’instruction publique (CDIP).

- Macgilchrist, Felicitas, John Potter, and Ben Williamson. 2021. “Shifting Scales of Research on Learning, Media and Technology.” Learning, Media and Technology 46 (4): 369–376. doi:10.1080/17439884.2021.1994418

- MacKenzie, Donald and Judy Wajcman. 1985. “Introductory Essay: The Social Shaping of Technology.” In The Social Shaping of Technology, edited by Donald MacKenzie and Judy Wajcman, 2-25. Milton Keynes, Philadelphia: Open University Press.

- Montagrin, Edouard. 1988a. “Microordinateur SMAKY, quelques arguments,” May 3, 1988. pp. 953–115. Archives cantonales vaudoises.

- Montagrin, Edouard. 1988b. “Smaky, ordinateur vaudois ou non?” May 17, 1988. pp. 953–115. Archives cantonales vaudoises.

- Montagrin, Edouard. 1988c. “Lettre du groupe des animateurs Smaky,” May 27, 1988. pp. 953–115. Archives cantonales vaudoises.

- Montagrin, Edouard. 1990a. “Proposition d’égalisation des possibilités entre les appareils Mac Intosh et Smaky pour les établissements utilisant le Smaky.” pp. 953–115. 10

- Montagrin, Edouard. 1990b. “E. Montagrin à G. Gilliéron, secrétaire général de SPV,” July 2, 1990. pp. 953–115. Archives cantonales vaudoises.

- Morel, Raymond. 1981. “Résumé des développements et de l’utilisation des microsystèmes dans l’enseignement secondaire (Période 1979–1980).” 2006 va 33.4.20. Archives d’Etat de Genève.

- “NFP 05 ‘Regionalprobleme in der Schweiz, namentlich in den Berg- und Grenzgebieten’”. n.d. “Schweizerischer Nationalfonds (blog).” Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.snf.ch/de/12fvDFPBw1EGifOY/seite/fokusForschung/nationale-forschungsprogramme/nfp05-regionalprobleme-schweiz-berg-grenzgebieten.

- “NFP 10 ‘Bildung und das Wirken in Gesellschaft und Beruf’” n.d. Schweizerischer Nationalfonds (blog). Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.snf.ch/de/S86dtGvPmnMkWwnY/seite/fokusForschung/nationale-forschungsprogramme/nfp10-bildung-wirken-gesellschaft-beruf.

- Nicoud, Jean-Daniel. 2011a. Jean-Daniel Nicoud, an Oral History Conducted in 2011 by Peter Asaro, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana for Indiana University and the IEEE. https://ethw.org/Oral-History:Jean-Daniel_Nicoud.

- Nicoud, Jean-Daniel. 2011b. “The Smaky’s Family.” Accessed February 28, 2023. https://archiveweb.epfl.ch/lami.epfl.ch/teach/smaky.html.

- Nicoud, Jean-Daniel and Fondation Mémoires Informatiques. n.d. “Smaky.ch : une histoire de l’informatique en Suisse.” Accessed July 21, 2022. http://www.smaky.ch/.

- “Offre Smaky 100 concernant l’équipement informatique des établissements scolaires vaudois”. 1985. “Epsitec-System S.A.” pp. 953–115. Archives cantonales vaudoises.

- Paoli, Simone. 2017. “The European Community and the Rise of a New Educational Order (1976–1986).” In Contesting Deregulation. Debates, Practices and Developments in the West since the 1970s, edited by Stefan Müller and Knud Andresen, 31: 138–152. Making Sense of History. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Pralong, Christian. 1990. “Informatique Scolaire,” May 28, 1990. pp. 953–115. Archives cantonales vaudoises.

- “Procè-verbal no 37. Séance du lundi 26 septembre 1983, au Gymnase de Chamblandes.” n.d. Commission Cantonale d’Informatique, 31 octobre 1983. SB 312 B 189. Archives cantonales vaudoises.

- Rankin, Joy Lisi. 2018. A People’s History of Computing in the United States. Cambridge, MA, London: Harvard University Press.

- Raphael, Lutz. 2019. Jenseits von Kohle und Stahl. Eine Gesellschaftsgeschichte Westeuropas nach dem Boom. Erste Auflage. Frankfurter Adorno-Vorlesungen 2018. Berlin: Suhrkamp

- “Recapitulation des demandes en microsystèmes pour satisfaire les besoins des établissments secondaires”. 1979. 2006 va 33.4.20. Archives d’Etat de Genève.

- Renaud, C. 1979. “Sous-commission ‘micro-système.’ PV no 11. Séance du 5 novembre 1979. Collège Calvin 10h00.” GIDES. Sous-commission “micro-système.” 2006 va 33.4.20. Archives d’Etat de Genève.

- Smaky News. 1986. “PROF: langage auteur de Denis Dumoulin,” September 1, 1986.

- Stamm, Marielle. 1978a. “IMMM à Genève pour la 2ème fois - Majorité d'acheteurs OEM parmi les 5 200 visiteurs.” 01 Informatiques 496, July.

- Stamm, Marielle. 1978b. “Raymond Morel, président du Groupe de coordination informatique: ‘L'informatique à l'école doit être généralisée.’” 01 Informatique, no. 515 (November): 23.

- Tanner, Jakob. 2015. Geschichte der Schweiz im 20. Europäische Geschichte im 20. Jahrhundert. München: C. H. Beck.

- “Vorschläge zur wirtschaftlichen Stärkung des Juraraumes”. 1983. Bern: Koordinationsorgan BIGA/Uhrenkantone/Uhrenstädte.