ABSTRACT

Estonia has since the liberation from the Soviet Union in 1991 successfully branded itself as a digital society and an education nation. This transformation builds on a sociotechnical imaginary where the progression of learning and the advancement of future citizens is postulated by a restructuring of the classroom through digital solutions. In this case study, we look at a prototype of a future classroom that was set up at the Estonian pavilion at the world fair EXPO 2020 in Dubai, as part of a nation branding process, promoting the nation’s educational system and prosperous ed-tech sector. The future classroom was promoted using slogans and futuristic visuals that targeted foreign investors and policy makers, in a way that suggested that the anticipated digital future already exists in Estonia, and therefore, is available for foreign investment, while at the same time connecting to a national and historical narrative of Estonia as part of the European cultural sphere.

1. Introduction

It doesn't look like much of a classroom, right? I guess you're more used to the situation where the teacher leads all the activities, but you will get used to it – just like I did!

The above quote is taken from a video that was made to promote ‘the future classroom’ as a part of the nation branding of Estonia for the (delayed) world fair EXPO 2020 that was held in Dubai, from October 2021 to March 2022. In this video we see a girl, who is approximately 10–12 years old, carrying a touchscreen tablet, and addressing the camera directly as she walks us through a smart classroom. In the video, this space is represented as a 3-D animated hologram that adds a futuristic feeling. Most notable of these holograms is a model of a smart classroom, which was also materialized in a small-scale prototype in the Estonian pavilion, alongside material from Estonian ed-tech companies. Indeed, educational development and digital technology made up two of the main themes in the pavilion and can be understood as part of the branding of Estonia as a start-up nation with a strong educational system, and thus a competitor on the global market well worth investing in (Tammpuu and Masso Citation2018).

In this article, we use the Estonian pavilion as a point of departure to explore how imaginaries regarding ‘the future of education’ (Facer Citation2011; Selwyn et al. Citation2020) are tied to national identity and processes of nation branding. To discuss this relation between technological development and future making, we connect our study to the widely used concept of sociotechnical imaginaries (Jasanoff Citation2015). We do this through an empirically grounded analysis of how sociotechnical imaginaries are constructed, materialized and ‘synchronized with ongoing projects of nation building’ (Jasanoff Citation2015, 335). Hence, we want to explore how education and the transformation of the classroom as a learning space is used as a projection of the future (Rahm Citation2023) and relate this to the national history of Estonia, thus contributing to the conceptual and empirical debate regarding how sociotechnical imaginaries are constructed, as well as the ongoing discussion of the future of education within the realms of critical studies of educational technologies.

We depart from a media production perspective (Deuze and Prenger Citation2019) to show how nation specific versions of transnational and dominant sociotechnical imaginaries regarding education were materialized and marketed. Estonia is used as a case here because of its strong emphasis on digital development, a process that in the official narrative has transformed the country ‘from underdeveloped, post Soviet transition state into e-Estonia, an advanced digital society’ (Mäe Citation2017, 33). From a longer historical perspective however, it is not only a matter of westernization but actually a rewesternization where Estonia through competing with other western nations when it comes to digital and educational development reconnect with Europe and the western world of which the country was a part before the Soviet occupation (Lauristin and Vihalemm Citation2009; Citation2020). The sociotechnical imaginaries produced by actors in the Estonian tech and education industry thus involve not only visions of the future but also of the past, and considerations of how these narratives can be used in relation to a global market of investors.

While recognizing the commercial and governmental interests involved in this future making, we approach the case from an empirical perspective. Our aim is to understand and bring forth the complexities and concrete work involved in the production of sociotechnical imaginaries by mapping the main agents and motives behind the production and promotion of the future of education at the Estonian pavilion at EXPO 2020. This is accomplished by focusing on how the future classroom was visualized in the video, in the promotion material, and in the exhibition spaces. At the end of the analysis, we relate these anticipations of education to the Estonian educational and national history.

2. Previous research and theoretical framework

The classroom is an important node in any school system, which means that it is connected to a complex comprising historical and institutional, physical, and administrative mechanisms and knowledge structures, as well as to an assemblage of regulations, measurements, architectonic and technological solutions (Mäkitalo-Siegl et al. Citation2010; Tyack and Tobin Citation1994). The classroom has since long also been a space for the implementation of new forms of educational media technologies, from school films to VR (Cuban Citation1986; Good Citation2020). With digitalization, there has been an increase in terms of the assumptions made regarding how new technologies can transform the classroom and education at large (Selwyn et al. Citation2020). This has made the classroom a target for innovators and ‘edupreneurs’ (Ideland Citation2021) since it is a concrete site where the otherwise dispersed complexity of the educational system can be distilled and made into an object of visions and hope.

These ‘Edutopias’ are articulated through a production of images, reports and narratives that depict, predict and prescribe how learning, communication and citizenship can and should be organized at the ‘digital frontier’ (Leahy, Holland, and Ward Citation2019), often in association with different forms of personalized learning and learning analytics as well as immersive media like AR (augmented reality), VR (virtual reality), holograms, interactive walls and artificial intelligence (Knox, Williamson, and Bayne Citation2020). A considerable amount of research and investments from the industry side have been put into this venture (c.f. Google Citation2019), while more critical scholars have long questioned the hype and hopes regarding digital technologies in education and other fields of society (Cuban Citation1986; Woolgar Citation[2002] 2009) and discussed it as a form of ‘colonization of the future’ (Selwyn and Facer Citation2013, 11) based on principles of global capitalism, neoliberalism and new public management (Ideland Citation2021; Knox, Williamson, and Bayne Citation2020; Selwyn et al. Citation2020; Williamson Citation2017).

While we agree with much of this critical perspective, we have here chosen to focus more on how different agents, from architects and video makers to government officials, performed their understanding of the future of education through their deliberations and creative work in the formatting of ‘the future classroom’ as part of the nation branding of Estonia for EXPO 2020. To discuss this matter, we rely on the notion of sociotechnical imaginaries, defined as ‘collectively held, institutionally stabilized, and publicly performed visions of desirable futures, animated by shared understandings of forms of social life and social order attainable through, and supportive of, advances in science and technology’ (Jasanoff Citation2015, 19). We further follow Jasanoff in her understanding of sociotechnical imaginaries as, ‘the embedding of ideas into cultures, institutions and materialities’ (Citation2015, 323) and an extension of global ideas into local constellations, where they become re-embedded in the political culture of nations. This connection between the transnational and national governance and cultural projections and imaginaries on how to maintain and improve complex systems (such as systems for energy, environment, education, etc.) through the advancement of new and emerging digital technologies, can also be related to what Flyverbom and Garsten (Citation2021) refer to as anticipatory governance by which they mean, ‘a knowledge-based, performative phenomenon that addresses potential and desirable futures and operates as a mode of shaping, controlling and orchestrating organizations’ referring to a process of assembling and combining different agents and socio-material resources through different forms of anticipatory actions that are both performative and prescriptive (Flyverbom and Garsten Citation2021, 2–3).

In relation to our case study, it is also important to distinguish between nation building and nation branding. Nation building refers to forms of governance that are meant to create national unity and identity. Nation building is thus directed in-wards to the nation state itself and its citizens, for example, through references to history and traditions (Hobsbawm and Ranger Citation1983) and the means of mediation and infrastructures of communication (c.f. Anderson Citation1983). Nation branding partly overlaps with nation building, but is more related to collaborations between governmental agencies, business interests, PR-consultants, media producers (Bolin and Ståhlberg Citation2010) and relations with foreign investors and potential trading partners, not least during events such as world fairs (Smits and Jansen Citation2012). Nation branding has also been described as a form of soft power (Nye Citation2008) that in terms of control and management of information is related to ‘the ability to shape the preferences of others’ as well as ‘creating the power of getting others to want what you want’ (95). Still, Viktorin et al. (Citation2018) suggest that nation branding does not merely ‘constitute an instrument of image boosting but, in fact, represents a struggle over what the nation is, to whom, and why, among local, governmental, and nonstate actors and organizations’ (10). The Estonian pavilion at EXPO 2020 in Dubai not only relate to nation building and nation branding but also the long tradition of world fairs since these events ‘are part of the languages chosen to represent ideas about the future’ (Lopez-Galviz, Nordin, and Dunn Citation2019, 1378) and a form that illustrates how images of the future shape present decisions (Poli Citation2014).

3. Method and material

Drawing on methods from media production studies, we explore the different actors and institutions involved in the making of the Estonian pavilion and the logics that guided them (Deuze and Prenger Citation2019). More concretely, we have performed interviews with key persons involved in different parts of this production and asked them about their deliberations and engagements. The participants include two governmental representatives, one person who worked at the pavilion in Dubai, and a producer from the production company that was assigned by Education Estonia (governmental agency) to make the video that we referred to at the beginning of this article. All our interviews can be described as expert interviews (Bogner and Menz Citation2009) that we made with individuals who in different ways had been engaged in the production of the pavilion and the video material that accompanied this. The interviews (six in total) were semi-structured (Hammersley and Atkinson Citation2007) and made over Zoom between May and August 2022. Since the interviews were done on a video-based platform, the informants could share documents, links, show videos to us, etc., during the session.

We have also drawn largely on material taken from the websites of the partaking organizations, such as Education Estonia, EdTech Estonia, e-Estonia, Education and Youth Board and as well as the official Facebook page eestipaviljonDubais2020 (www.facebook.com/eestipaviljonDubais2020). Another important source has been a special issue of a magazine called Life in Estonia, published by investinestonia.com, to promote and brand the Estonian pavilion at EXPO 2020 (Grosberg Citation2021). The visual material and the interviews have been analyzed in tandem to capture what Gillian Rose (Citation2012, 20–25) refers to as an image’s ‘site of production’ and that includes a mapping of the process of making this image or visual material, what genres or image conventions it draws on, who it was made for and why. It is also important to note that the construction of a pavilion at a world fair extends to more than its objects and promotional material; it is also about the creation of a narrative (Bal Citation2010). To capture this dimension, researchers in the field of exhibition studies often stress the need for an ‘architectural sensibility associated with the placement of objects in a space’ (O’Donnell Citation2016, 80). In our study we have tried to accomplish this through a reconstruction of the exhibition space based on promotional material and images of the pavilion found online, in combination with ethnographic notes made by one of the authors, while visiting the Estonian pavilion in December 2021. We have also tried to understand how the exhibition ‘appeared to the visitor moving through the exhibition space, as opposed to statically viewing the exhibition from the fixed point of view of the photographer or the aerial view of the annotated floor plan’ (O’Donnell Citation2016, 77) by making a ‘digital walk through’ (on Zoom) of the exhibition space under the guidance of one of the staff at the Estonian pavilion in Dubai, focusing especially on the prototype of the smart classroom.Footnote1

4. From Zero to hero

The overall theme of the special issue of the magazine Life in Estonia (Grosberg Citation2021) for EXPO 2020 was ‘Technology is our second language’, and in this magazine the Estonian pavilion is presented by the general manager as a place to ‘meet our partners who have built Estonia’s digital society and they will show you how to do this in your own country’ while an ICT-consultant agency and investor, as well as the chairman of the Supervisory Board of EXPO 2020, describe Estonia as ‘a sandbox and test site for digital services, where digital transformation happened because the government and the private sector jointly created a digital identity for all residents’ (ibid). The consultant also strongly emphasizes the role of education for the digital development and identity of Estonia.

This branding of Estonia as ‘the education nation’ is no coincidence. Over the last 25 years, Estonia, the smallest of the Baltic states (1.3 million inhabitants) has branded itself as a successful education nation (Mehisto and Kitsing Citation2022) and received international attention for its high ranking in the PISA-survey (Boman Citation2020). Estonia is also acclaimed for having many startups and ICT-investments, as well as being a pioneer in terms of e-Democracy and e-Governance, including Internet voting (i-Voting) and government-issued systems for e-ID. Yet, the voice of critical data scientists (e.g., Männiste and Masso Citation2020) stressing ethical and social issues concerning digital governance ideals of Estonia has largely been eclipsed by louder voices of techno-optimists. In the cover of the special issue of Life in Estonia (Figure 1.1) and one image from this issue (Figure 1.2) illustrate how Estonia was branded as oriented towards the future, lifelong learning and an inclusive, explorative, and progressive digital culture.

Figure 1. Cover plus page 9 from a special issue of Life in Estonia about EXPO 2020. Photos: Sirli Raitma, Aron Urb. .1 Sirli Raitma. A photograph showing an old lady with a tracksuit jacket wearing a VR-helmet with the text “Technology is our second language”. .2 Aron Urb. Photograph of children throwing paper airplanes from a round window with the text ‘Presenting a nation of tomorrow’.

4.1 The Tiger Leap and onwards

The process of branding Estonia as a digitally advanced society started with the introduction of the Internet, right after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the restoration of an independent Estonia in 1991. The Internet was first used by academics and the media, then by state agencies in the build-up of various e-services (Runnel Citation2009, 15; cf. Velmet Citation2020). By putting much effort into implementing and applying Internet and various new media technologies to systems for governance, not least within the educational sector, it was promoted as a way to, as Runnel (Citation2009, 16) puts it, help Estonia ‘catch up’ with the advanced European countries and fulfil the agenda of “Estonia's integration” into the democratic Western societies. Runnel further explains how matters of international competitiveness were articulated and made part of certain narratives about Estonia as a nation centered around ICT and education. One crucial part of this was an educational program called ‘The Tiger Leap’, which suggested that Estonia might become a successor to the 21st century's ‘booming high-tech Asian Tigers’ (Velmet Citation2020, 175).

The Tiger Leap program was mainly focused on primary and secondary schools and had three pillars: to provide schools with computers and Internet; to offer teachers digital training; and to develop digital educational content in the Estonian-language. Hence, most schools in Estonia were equipped with computers and an Internet connection already in the late 1990s, and thousands of teachers were offered a 40-hour program with basic computer training (hitsa.ee). In this way, the Tiger Leap program also contributed to a sense of national identity and a narrative about Estonia as ‘the education nation’ at the digital frontier. In 2014, digital competence became part of the Estonian national curriculum, and over the last two decades the development of educational technology in Estonia has become more and more aligned with international partners and start-ups, as well as with the European Commission. Over time, the focus in Estonian ed-tech research and development has shifted from being tech centered to becoming more focused on innovative pedagogical methods and the design of the future classroom. Consequently, models have been developed for inquiry-based learning spaces, online laboratories, app-supported learning, and guidelines for learners and teachers. Some of this has also been implemented in other parts of the world (Pedaste et al. Citation2015). Estonia has thus a long history in terms of advertising education and the use of digital technologies.

4.2 The Blue Pavilion

EXPO 2020 was meant to be held in Dubai in 2020 but, due to the pandemic, it was postponed and instead held from October 2021 to March 2022. With an overall investment of more than 7 billion dollars and a total of 24 million visits over six months, 190 countries could showcase their offerings and ambitions (gulfnews.com). One part of this was the Estonian pavilion, and one of the exhibition coordinators described the main objectives behind the exhibition as follows:

So we have an exhibition downstairs that talks about the digital story and how Estonia went from ‘zero to hero’, how we started off from nothing in the nineties and now 99% of our government services are available online.

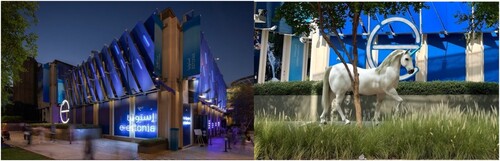

Figure 2. Foundation of Estonian Section at EXPO 2020 Dubai (Brand Estonia). Photos: Ismail Noor. .1 A photograph of a glass building shining with blue light and the letter E in neon. .2 A photograph of a unicorn statue on artificial glass and with a blue background.

Within the pavilion, various forms of ‘exhibition media’ (Ekström Citation2019) were used to inform visitors about different aspects of the digital revolution in Estonia, offering facts such as: 3000 digital services, seamlessly interlinked digital platforms that connect public and private sectors, most public services available online, e-health, e-democracy, e-tax, etc. The pavilion and the PR around it also pointed out more future oriented aspects of Estonia as being A nation of tomorrow, The Unicorn Factory, Digital, smart, sustainable, or as one of the exhibition coordinators explained the pavilion to us: ‘the know-how, the processes, what we have and how we got there and how it is beneficial for the citizens and for other countries.’ The visitors were also encouraged to ‘join the e-revolution’ and enjoy the digital lifestyle of Estonia. A special arrangement was the ‘Estonian Education Week’ that gathered universities, governmental representatives, business interests, startups and ed-tech researchers.

4.3 First floor

The first floor of the Estonian pavilion was open to all visitors. The focal point and the key to the creation of a ‘futuristic feeling’ on the entrance floor was an installation of 400 blue lamp balls, hanging from the ceiling at different heights () and endlessly reflecting on the mirrored walls hence creating ‘a sensation of infinity, symbolizing Estonia’s scalable and infinitely expandable digital services’ (Grosberg Citation2021, 13).

Figure 3. Inside the Estonian pavilion in EXPO 2020. Photo: Mihkel Sillaots. A photograph of room with sphere shaped lamps hanging from the ceiling in different heights, shining with blue light.

The first floor was also filled with screens that informed visitors about various ‘smart solutions’ of Estonian origin. More than 40 companies and organizations were represented at the pavilion, among them many startups, not least from the ed-tech sector, who were at the pavilion to interact with investors from other parts of the world. The blue light and mirrors were used to create a sense of infinity for those present in the pavilion. The color blue recurred in other parts of the exhibition media, such as in the video and the special issue, where it was used to also connote the Estonian flag (blue, black and white) and Estonia as a forward facing and progressive digital nation. Compared to this futuristic feeling of the first floor, the second floor of the pavilion was more dedicated to business activities, appointments, and special events, and it included meeting rooms and office spaces. It was also here that the prototype of the smart classroom was located.

4.4 Second floor and the prototype of classroom

In our pavilion you get a glimpse of the future – with a classroom of the future and the best of our ed-tech solutions on display.

Figure 4. The smart classroom prototype at the Estonian pavilion at EXPO 2020. An indoor space with modern furniture in light colors.

The idea to include a prototype of a smart classroom came from the team behind the Estonian pavilion, while the prototype as such was the result of a collaboration between an Estonian furniture manufacturer (that otherwise produces furniture for hotels, rooms and lobbies) and an Estonian designed bureau with considerable experience from designing schools. The furniture in this space was made so it would be easy to move around and rearrange, with mobile walls and separators to make it possible to resize the room and mobile podiums for training and performing presentation skills. Many of these objects had sockets and loading stations that were connected to communication networks (investinestonia.com). As we now will see, some of these ideals of collaboration, personalization and connectivity were also emphasized in the design of the videos that were made to promote the smart classroom and Estonia as an education nation for the future.

5. Visualizing the future of education

Among the five videos that were produced to promote Estonia as an education nation, two had Arabic subtitles and could hence be showcased at the EXPO 2020 in Dubai. One of them featured a boy at an early school age, who introduces the viewer to the Estonian education system by walking us through classrooms, from kindergarten to university. The other one was the previously mentioned video of the future classroom, which we will focus on in this section. By exploring the production process behind the video, we try to capture how sociotechnical imaginaries are negotiated, materialized and communicated through visual techniques and image conventions, conceptualized here as anticipatory actions (Flyverbom and Garsten Citation2021). Our analysis of this starts with 1) a short description of the general message of the video, followed by a three-step analysis inspired by Rose’s (Citation2012) framework for how to study images through its sight of production and continues by looking at, 2) the production process (technological modality), 3) genre/imagery (compositional modality), and 4) aim and intended audience (social modality).

5.1 A walkthrough of the smart classroom

The video is called Smart Classroom and was produced on commission from Education Estonia (an initiative for international education cooperation by the Government of Estonia) for EXPO 2020. The video features a girl wearing pink trousers and a white t-shirt with the logotype of Education Estonia printed on it. The video opens with the line ‘Hello, and welcome to the future of education!’, followed by the clarification that she is about to introduce us to a smart classroom. The initial quote in this article, assuring the reader that he or she will also get used to this kind of classroom, is accompanied by a cut in footage of students leaning over their iPads and books. This classroom is then compared to an old model of education ‘where the teacher leads all the activities’, illustrated by a hologram representing a traditional classroom, with the teacher standing at the front and the blackboard behind her (see .1). The hologram appears when the girl holds out her right hand and as in a magic gesture, accompanied by the sound of a bell-like sound (like something is being revealed). The imagery is dim and greyish, and the sound effects behind it connote something like a horror film.

Figure 5. Stills from the video of the smart classroom (Processed for EXPO 2020). .1 A girl holding a tablet in her left hand and holding out her right hand to reveal a hologram of a room and a sign that says, ‘Traditional classroom’. .2 A girl standing next to a computer, holding a tablet in her left hand pointing to a text that says, ‘Most learning materials are in the cloud‘. .3 A 3D image of a sectionalized classroom, with bluish glow and floating against a green background.

As the video proceeds, the camera moves from a room with bookshelves and seating pillows, resembling a library, into a hallway with glass walls, while the girl explains to the viewer that students in a smart classroom are given more responsibility for their learning, while still being guided by their ‘awesome teacher’ (cut in footage of the teacher waving). Next, the girl introduces the laptop as the most important learning tool that contains not only e-learning material ‘in the cloud’ (Figure 5.2) but also enables communication and follow ups between student and teacher.

In the final scene, the girl sits down on a couch and repeats her magic gesture, this time to reveal a hologram showing ‘the future classroom’ (Figure 5.3). As the model spins, the names of the different areas light up as the girl tells us about their intended use, from group work and creative workshops to individual studies and traditional teacher-led lectures. This is the most detailed part of the video and takes up around 30 seconds of the one minute and 50 second long video, which ends with the girl scrolling through a list of Estonian ed-tech companies on her iPad and encouraging the viewer to visit the website of Education Estonia.

5.2 The production process

We will now, in accordance with Rose’s (Citation2012) model, describe the production process and technological modality of this video in terms of how the visuals and props for the video came about. The video was produced by an advertising and video production company on a commission from Education Estonia, under the guidance of their project manager, who explained to us that she worked in collaboration with representatives from other governmental departments and that they together had ‘chiseled out’ the description of what they wanted the main message and form of the video to be. One premise for their ordering of the video (besides duration and budget) was a request that the smart classroom be represented with the help of some form of animation that represented the smart classroom. Based on this, companies that wanted to compete for the contract could present their scripts for how to visualize and narrate the message of a progressive and future-oriented national education system. According to the project manager at Education Estonia, it was the animation that made the winning video company stand out in the competition, as they used 3D-animations that resembled holograms, which was considered innovative and futuristic.

After being contracted, the real collaboration started, and ideas were being ‘ping ponged back and forth’. The production manager at the video company, who described himself as the ‘middle-man’ between the crew and Education Estonia, explained that the client had the last say when it came to changes in the script:

Of course, we had to accept all the input from their side because they are the people who are working with the smart classroom idea and showing it to the world. So we had to basically accept their ideas and mix it with our visual ideas.

It was also crucial for the production team to find a suitable setting for the shooting of the video with the girl walking through a smart classroom. The challenge here was to find a space that resembled the prototype of the future smart classroom as it was described in the hologram. To solve this, the production team decided to shoot the video in a school near Tallinn where they could use props to create a feeling of a future classroom space. In the school where the video was shot, there were empty bookshelves, and the production team decided to bring books to the set. When we asked why it was so important to have books in a video about the digital future, the video producer explained that ‘the main idea was to show futuristic elements but not without the books … books are still a big part of the education system’. Also, the project manager at Education Estonia, underlined the significance of books as a symbol for the importance of traditional knowledge forms.

5.3 Genre and imagery

In the video, the past and the future are not only described through the use of props but also with the help of certain image conventions. One example of this is the use of holograms. While the hologram of the future classroom is presented like a floor plan with the names of the spaces as interactive signs, the hologram of the traditional classroom, although in bluish 3D, more resembles a sepia tinted photograph. The video producer explained to us that this was a conscious choice to connote ‘the historical traditional classroom’. The hologram of the smart classroom, on the other hand, with its bluish glow was designed to look futuristic, and was even compared by the production manager with the aesthetics used in science fiction films. He also explained that the specific sound that is heard when the holograms appear was chosen because ‘holograms usually do this kind of sound in space movies’. The interview material further indicates that the hologram was used as a form of anticipation for something partly already present but still not yet fully realized. The consideration behind this anticipatory action was described by the project manager at Education Estonia as follows:

You are like inside, and something is going on and you can touch it, and of course you know it has been made, that it is artificial, but you are feeling like being in the future / … / it is futuristic and innovative, and not only by words, but while looking at it you feel like ‘Oh, I want to be there!’

5.4 Aim and intended audience

During the interviews, it turned out that one target group for the video with the girl was representatives from the UAE-region, Dubai being one of them. Throughout the interviews, we learned that this could explain the girl’s opening phrase in the video: ‘You will get used to it, just like I did.’ The ‘you’ implied here is thus an adult, foreign investor, or policy maker, with little or no experience of smart classrooms. However, in the video the implied viewer is comforted by a young person, who is already part of a future that seems predetermined and inevitable. This interpretation was confirmed by the production manager of the video, who informed us that the video was made to address ‘educational representatives around the world’.

The main target group for the video was thus international investors, with the aim to create interest in the smart classroom. ‘When we are looking at this international target group, we cannot talk only about things that are good in Estonia for Estonians’ but must consider what others might find interesting, as the project manager at Education Estonia explained it. The video, together with the promotional material discussed above, can be understood as a part of a wider nation branding process of Estonia as an education nation with business connections to other nations when it comes to ed-tech solutions and innovation. As we will discuss next, this branding process also contains aspects of nation building in the sense that it draws on ideas about the past and shared national history, in the same way as the girl in the video backing into the classroom, while addressing the outside world (c.f. Angell and Larsen Citation2022).

6. Backing into the future

Since Estonia became independent again in 1991, the question of identity and belonging, as well as international recognition, has become extremely important. As discussed above, one part of the transformation of Estonia from a post-socialist country to an EU-member state has been interpreted as a projection of Estonia as part of the knowledge culture of central Europe (Lauristin and Vihalemm Citation2009). One objective in Estonia’s digital transformation has thus been to boost education and regain Estonia’s status as an education nation. Here investments in education have been a prerequisite for Estonia’s rapid transformation into a world leading e-society. This was also part of the narrative told to foreign investors at the Estonian pavilion during EXPO 2020. This is how the exhibition coordinator explained the matter:

It’s a very big part of our digital backstory […] None of the things that we have right now would be possible without education, without ICT education, without having taught people how to use things.

We have already described the role of education and digitalization as part of the national identity of Estonia as an independent, progressive, and prosperous nation. Although this sociotechnical imaginary is not exclusive to Estonia, it must be understood in relation to the specific conditions of Estonia’s history. It can also be noticed that, since the first World Fair, held in 1851 at Crystal Place in London, world fairs have been about boosting international reputation and business opportunities, as well as performing a form of national consciousness and shared future. Projections and anticipations, prescriptions, and prognostics, with references to desired futures and technological development, are important aspects of this, and over the last few decades there has also been an increased emphasis on digital solutions, for example, in relation to educational progress and a new knowledge economy.

7. Concluding remarks

We have in this article used ‘the future classroom’ as a prism to discuss how sociotechnical imaginaries of a transnational nature are configured and concretized in relation to processes of nation branding, and the anticipation of a desired future, with the production of promotional material for the Estonian pavilion at EXPO 2020 as empirical example. Our results show that the trope of the future classroom came into play in a collaboration between different governmental and corporate interests, to brand and promote Estonia as the education nation in order to attract foreign interest to Estonia to invest and do business. One aspect of this venture was the production of exhibition media that used metaphors (e.g., the unicorn, the sandbox, technology as a second language), slogans (e.g., e-Estonia, A nation of tomorrow, The education nation), and imagery (the color blue, holograms and fluorescent light) to create a futuristic and progressive sense around the Estonian pavilion. More concretely, we have shown how a futuristic feeling was implemented in the promotional materials (such as Life in Estonia) that accompanied the arrangements at the Estonian pavilion in Dubai. Through an analysis of the deliberations and creations in the production and design of one of the videos that were made to promote the conceptualization of the smart classroom, we have shown how the future of education was represented by holograms and visual polarizations between traditional and future forms of classrooms, to put Estonia on the world map and attract foreign interest and investments.

These concrete examples of how the trope of the future classroom was used in the production of the exhibition media for the Estonian pavilion reveals how anticipatory actions connect transnational and dominant sociotechnical imaginaries with national politics, identity, and history. In the case of Estonia, we have shown how these global hypes and hopes, regarding how digitalization will transform and improve education, become embedded in the nation specific narrative of Estonia as an educational nation in the European cultural sphere. This national narrative included advertising videos with children as representatives of modern Estonia and its future, with innovation, startups and foreign investment, digitalization and new learning environments as some of the main keys.

The nation branding process of Estonia, including the smart classroom prototype, was thus not only oriented outwards toward foreign interest, but also included elements of nation building directed inwards to Estonia and its citizens. The representation of Estonia as an innovator society and education nation is performative in the sense that it not only projects a preferred future but also to some extent prescribes it. This form of anticipatory governance brings together public and commercial interests to organize and control the future of education. With our case study we have thus tried to show how the digitalization of public education in a concrete and performative way is negotiated and articulated in nation-specific terms, supporting a process of ongoing nation building and formation of national identity.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Michael Forsman

Michael Forsman is a Full Professor in Media and Communication Studies at Södertörn University (Sweden). His research concerns media, children and youth, media literacy, and the digitalization of education. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8669-5752

Ingrid Forsler

Ingrid Forsler is an Associate Professor in Media and Communication Studies at Södertörn University (Sweden). Her research concerns imaginaries about media in education, media literacy, and visual methods. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1548-1981

Signe Opermann

Signe Opermann is a Research Fellow in Media Sociology at the University of Tartu (Estonia). Her recent research concerns media use, platformization of family life, digital skills, and digitalization of education. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7070-0545

Emanuele Bardone

Emanuele Bardone is an Associate Professor at the Centre of Educational Technology at University of Tartu (Estonia). His main research interests revolve around critical educational technology and philosophy of technology. He is currently Director of the International Master's Programme in Educational Technology in the same university. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9038-2580

Margus Pedaste

Margus Pedaste is a Full Professor of Educational Technology at the Institute of Education of the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Tartu (Estonia). His research focuses on improving learners’ digital competence and inquiry skills, as well as on educational technology in supporting teaching and learning. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5087-9637

Notes

1 Our case comes with certain ethical implications, since it is hard to guarantee the anonymity of the participants since they represent institutions that are described in the text. To avoid misinterpretation or unnecessary details in the text, the participants have been given the opportunity to read the article before publication and have given their permission.

References

- Anderson, Benedict R.O. 1983. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

- Angell, Svein Ivar, and Eirinn Larsen. 2022. “Introduction: Reimagining the Nordic Pasts.” Scandinavian Journal of History 47 (5): 589–599. doi: 10.1080/03468755.2022.2051599.

- Bal, Mieke. 2010. Double Exposures the Subject of Cultural Analysis. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bogner, Alexander, and Wolfgang Menz. 2009. “The Theory-Generating Expert Interview: Epistemological Interest, Forms of Knowledge, Interaction.” In Interviewing Experts, edited by Alexander Bogner, Beate Littig, and Wolfgang Menz, 43–80. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bolin, Göran, and Per Ståhlberg. 2010. “Between Community and Commodity. Nationalism and Nation Branding.” In Communicating the Nation: National Topographies of Global Media Landscapes, edited by Anna Roosvall, and Inka Salovaara-Moring, 79–101. Göteborg: Nordicom.

- Boman, Björn. 2020. “What Makes Estonia and Singapore So Good?” Globalisation, Societies and Education 18 (2): 181–193. doi:10.1080/14767724.2019.1701420.

- Cuban, Larry. 1986. Teachers and Machines: The Classroom Use of Technology since 1920. New York: Teachers college Press.

- Deuze, Mark, and Mirjam Prenger. 2019. Making Media: Production, Practices, and Professions. Amsterdam: University Press.

- Ekström, Anders. 2019. “Walk-in Media: International Exhibitions as Media Space.” In The Routledge Handbook of Museums, Media and Communication, edited by Kirsten Drotner, Vince Dziekan, Ross Parry, and Kim Christian Schrøder, 17–30. London: Routledge.

- Facer, Keri. 2011. Learning Futures Education, Technology and Social Change. London: Routledge.

- Flyverbom, Mikkel, and Christina Garsten. 2021. “Anticipation and Organization: Seeing, knowing and governing futures.” Organization Theory 2 (3), doi: 10.1177/26317877211020325.

- Good, Katie Day. 2020. Bring the World to the Child: Technologies of Global Citizenship in American Education. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Google. 2019. Future of the Classroom Emerging Trends in K-12 Education. Global Edition. Google for Education.

- Grosberg, Reet ed. 2021. Life in Estonia, 57, 2. Tallinn: Estonian Investment Agency. Accessed 16 February 2023. https://investinestonia.com/business-in-estonia/life-in-estonia/magazine-dubai-2020-special.

- Hammersley, Martyn, and Paul Atkinson. 2007. Ethnography: Principles in Practice. 3rd ed. London, New York: Routledge.

- Hobsbawm, Eric, and Terence Ranger, eds. 1983. The Invention of Traditions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ideland, Malin. 2021. “Google and the End of the Teacher? How a Figuration of the Teacher is Produced through an Ed-Tech Discourse.” Learning, Media and Technology 46 (1): 33–46. doi: 10.1080/17439884.2020.1809452.

- Jasanoff, Sheila. 2015. “Future Imperfect: Science, Technology, and the Imaginations of Modernity.” In Dreamscapes of Modernity: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Fabrication of Power, edited by Sheila Jasanoff, and Sang-Hyun Kim, 1–47. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Jasanoff, Sheila, and Sang-Hyun Kim, eds. 2015. Dreamscapes of Modernity: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Fabrication of Power. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Knox, Jeremy, Ben Williamson, and Sian Bayne. 2020. “Machine Behaviourism: Future Visions of ‘Learnification’ and ‘Datafication’ across Humans and Digital Technologies.” Learning, Media and Technology 45 (1): 31–45. doi: 10.1080/17439884.2019.1623251.

- Lauristin, Marju, and Peeter Vihalemm. 2009. Estonia’s Transition to the EU: Twenty Years On. London, New York: Routledge.

- Lauristin, Marju, and Peeter Vihalemm. 2020. “The ‘Estonian Way’ of the Post-Communist Transformation through the Lens of the Morphogenetic Model.” In Researching Estonian Transformation: Morphogenetic Reflections, edited by Veronika Kalmus, Marju Lauristin, Signe Opermann, and Triin Vihalemm, 33–73. Tartu: University of Tartu Press.

- Leahy, Sean M., Charlotte Holland, and Francis Ward. 2019. “The Digital Frontier: Envisioning Future Technologies Impact on the Classroom.” Futures 113 (102422): 1–10.

- Lopez-Galviz, Carlos, Astrid Nordin, and Nick Dunn. 2019. “Latent Fictions: The Anticipation of World Fairs.” In Handbook of Anticipation: Theoretical and Applied Aspects of the Use of Future in Decision Making, edited by Roberto Poli, 1377–1393. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland AGm.

- Mäe, Rene. 2017. “The Story of e-Estonia: a Discourse Theoretical Approach.” Baltic Worlds 2017 (1–2): 32–44.

- Mäkitalo-Siegl, Kati, Jan Zottman, Frederic Kaplan, and Frank Fisher eds. 2010. Classroom of the Future: Orchestrating Collaborative Spaces. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Männiste, Maris, and Anu Masso. 2020. “‘Three Drops of Blood for the Devil’: Data Pioneers as Intermediaries of Algorithmic Governance Ideals.” Mediálni studia / Media Studies 14 (1): 55–74.

- Mehisto, Peeter, and Maie Kitsing. 2022. Lessons from Estonia’s Education Success Story: Exploring Equity and High Performance through PISA. Abingdon, New York: Routledge.

- Nye, Joseph S. 2008. “Public Diplomacy and Soft Power.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 616: 94–109. doi:10.1177/0002716207311699.

- O’Donnell, Natalie Hope. 2016. “Space as Curatorial Practice: The Exhibition as a Spatial Construct : Ny Kunst i Tusen År (1970), Vår Verden Av Ting - Objekter (1970) and Norsk Middelalderkunst (1972) at Henie Onstad Kunstsenter”. PhD diss., Oslo School of Architecture and Design.

- Pedaste, Margus, Mario Mäeots, Leo A. Siiman, Ton De Jong, Siswa A.N. Van Riesen, Ellen T. Kamp, Constantinos C. Manoli, Zacharias C. Zacharia, and Eleftheria Tsourlidaki. 2015. “Phases of Inquiry-Based Learning: Definitions and the Inquiry Cycle.” Educational Research Review 14: 47–61. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2015.02.003

- Peeterson, Eve. 2022. “Estonia – a Springboard for Unicorn Companies.” Invest in Estonia, January. Accessed 16 February 2023. https://investinestonia.com/estonia-a-springboard-for-unicorn-companies/.

- Poli, Roberto. 2014. “Anticipation: What About Turning the Human and Social Sciences Upside Down?” Futures 64: 15–18. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2014.10.003.

- Rahm, Lina. 2023. “Educational Imaginaries: Governance at the Intersection of Technology and Education.” Journal of Education Policy, 46–68. doi: 10.1080/02680939.2021.1970233.

- Rose, Gillian. 2012. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials. London: Sage.

- Runnel, Pille. 2009. The Transformation of the Internet: Use Practice in Estonia. PhD diss., University of Tartu, Institute of Journalism and Communication. Tartu: Tartu University Press.

- Selwyn, Neil, and Keri Facer. 2013. The Politics of Education and Technology: Conflicts, Controversies, and Connections. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Selwyn, Neil, Luci Pangrazio, Selena Nemorin, and Carlo Perrotta. 2020. “What Might the School of 2030 be Like? An Exercise in Social Science Fiction.” Learning, Media and Technology 45 (1): 90–106. doi: 10.1080/17439884.2020.1694944.

- “Smart Classroom”. Video produced by Education Estonia. Retrieved from YouTube. February 16. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=raW11Sv05X8.

- Smits, Katherine, and Alix Jansen. 2012. “Staging the Nation at Expos and World’s Fairs.” National Identities 14 (2): 173–188. doi: 10.1080/14608944.2012.677817.

- Tammpuu, Piia, and Anu Masso. 2018. “‘Welcome to the Virtual State’: Estonian e-Residency and the Digitalised State as a Commodity.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 21 (5): 543–60. doi:10.1177/1367549417751148.

- Tyack, David, and William. Tobin. 1994. “The “Grammar” of Schooling: Why Has it Been so Hard to Change?” American Educational Research Journal 31 (3): 453–479. doi:10.3102/00028312031003453.

- Velmet, Aro. 2020. “The Blank Slate E-State: Estonian Information Society and the Politics of Novelty in the 1990s.” Engaging Science, Technology, and Society 6: 162–184. doi: 10.17351/ests2020.284.

- Viktorin, Carolin, Jessica C.E. Gienow-Hecht, Annika Estner, and Marcel K. Will eds. 2018. Nation Branding in Modern History. New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books.

- Williamson, Ben. 2017. Big Data in Education: The Digital Future of Learning, Policy and Practice. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Woolgar, Steve ed. [2002] 2009. Virtual Society?: Technology, Cyberbole, Reality. Oxford: Oxford: University Press.