ABSTRACT

Affectively charged social media exchanges pertaining to remote schooling in Hungary during the early stages of the pandemic provided unique insights into dispositions towards technologically mediated learning. In this article, we explore how parents and teachers responded to the increased porosity, mobility, and visibility of classroom interactions during pandemic-related school closures. We wanted to know what emotive responses to the intensification of digital media use in the home revealed about boundaries of learning in Hungary. Data were gathered with SentiOneTM’s AI-based social listening tool and analysed by coupling an attunement to affect with a multimodal analytic. We found a lack of shared understanding of what technologically mediated learning from home entails placed boundaries of learning under threat. To enable shared understandings and strengthen trust between students, teachers, and parents, we propose protected spaces that escape public scrutiny for joint digital practices to evolve.

Introduction

‘This teaching equals zero’ ran the headline of an online news article published late March in 2020.Footnote1 Approximately two weeks prior the Hungarian Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán, announced the closure of schools and the start of remote schooling. In the following months, homes became nodes comprised of an odd mix of domestic life, learning and (when possible) work. As schools shifted into children’s and teachers’ ordinary domestic spaces via networked digital technologies, boundaries between home and school became porous. Meanwhile, everyday interactions of learners, teachers, and parents gained unexpected mobility and visibility through networked digital technologies, moving in and between settings (and the public domain) in previously unimagined ways. Early reflections on pandemic education showed that although it was called remote learning, this was anything but remote. With the school moving into the home, learning became ‘[…] close and personal and with the customary territorial trade-offs of colonization.’ (Williamson, Eynon, and Potter Citation2020).

The undoing of boundaries that have conventionally demarcated the where who and how of schooling that occurred during remote emergency teaching was marked by a range of emotions. These not only involved anxiety, anger, frustration, exhaustion but also experiences of a greater sense of intimacy, increased understanding of children’s lives as learners and a fuller appreciation of the complexity of teaching. The pandemic drew public and private spheres into each other – if only for a brief time – demonstrating how a system that has been historically resistant to change can indeed change, if forced to do so. In this study we glimpse the potential for networked and technologically mediated learning and, perhaps more significantly, the everyday volatilities that forced system-wide educational change invokes. We argue that reaching a deeper understanding of the micropolitical forces associated with these volatilities is an important step towards identifying how boundaries of digital technologies might be redrawn to enhance learners and learning across different sites.

A study concerned with tracing affect reveals much about the micropolitical forces at work in a given situation. According to Threadgold (Citation2021) moments of crisis can act as a window into everyday micropolitical forces that may go unnoticed in ordinary times but nonetheless play a significant role in moulding education systems and expectations of teachers’ work, parental involvement and student learning. The upheaval of a crisis has the potential to expose the mundane practices that produce and strengthen affective patterns of relating which, in time, prime the responses of both individuals and organisations (e.g., children, parents, teachers as well as the larger educational body). In this case, the sudden move to remote emergency teaching that accompanied the school closures has created a unique opportunity to study what happens when the boundaries or ‘rules of the game’ (Bourdieu Citation1990) change and place unprecedented emphasis on technologically mediated teaching and learning.

Early Covid-related studies indicated that experiences of remote learning varied widely and were influenced by several factors, such as age groups, the organisation of the family, workload, or teacher’s ICT use (European Commission Citation2021). However, there was agreement that in Europe, remote learning disproportionately impacted children from disadvantaged backgrounds, primary and lower secondary students, and those at schools where teachers had fewer digital skills (European Commission Citation2020). That disadvantaged students are more likely to attend schools with inferior ICT resources compounds educational disadvantage which, in the Hungarian context, is accentuated by a greater magnitude of socio-economic gap when compared to other EU countries (Eurostat Citation2019). Further complicating this picture is the finding that socio-economic factors are not the only consideration, as another Hungarian study adds, the usual social attributes (e.g., parents’ educational level, social class) did not influence the frequency of co-learning during Covid closures. What proved to be more relevant was whether the parents were working from home (less time for co-learning) and the number of children in the household (Engler, Markos, and Dusa Citation2021). This is consistent with other Covid studies, which highlight parents’ struggles with organising remote schooling at home and acting as teachers (e.g., European Commission Citation2021).

Together these studies provide a general sense of remote learning landscape in Hungary during a crisis; however, they are not able to tell us about the affects (and effects) of everyday experiences of the digital intensification during the school closures. Accordingly, we respond to a call issued by Williamson, Eynon, and Potter (Citation2020) to examine ‘in up-close detail, the effects and consequences of the expansion and embedding of digital technologies and media in education systems, institutions and practices across the world’ (2). Through a cooperation with SentiOne, an AI-based social listening tool, we collaborated with algorithms to work in the space between distant and close views of data, looking for patterns and sense-checking the data contributing to these patterns – exposing affective forces of systemic infrastructures and everyday encounters during lockdown. Blackman (Citation2019) calls this style of digital research ‘transmedial storytelling’, a type of ethnographic orientation for working with digital archives and AI-based social research technologies.

Positioning social media platforms (here, Facebook) as living digital archives, we engage empirical material via a multimodal analysis of parents’, children’ and teachers’ responses to the potpourri of changes brought along by the intensification of networked digital technology for learning. In adopting multimodal discourse as a socio-cultural practice (Hunt Citation2015) imbued with affectivity (and materiality), we aim to contribute knowledge concerned with how specific practices of writing articles, posting, commenting on or reacting to the topic of remote learning indicated broader affective affinities with digital technologies.

To achieve this aim, we were guided by the question:

To what extent did the intensification of digital media use in the home unsettle the boundaries of learning during the Covid-pandemic in Hungary? And, with what affects?

Affective affinities

In educational situations, affect is commonly conceived in terms of learning to affect and be affected (Mulcahy Citation2012). Affect can be gauged as movement or change in capacity to act at, both a bodily level (e.g., bodily affect) and a transpersonal level (e.g., arising in and between the bodies, materials, digital technologies, and ideas that participate a given event). It is this movement or change that translates into micro-powers or micro-politics. Accumulating lots of tiny incremental changes in the capacity to act may create momentum and become the basis of transformative change (Mulcahy and Martinussen Citation2023). In our analysis, we use the term ‘confluence’ to denote affective affinities that enhance a person’s power to act and ‘dissonance’ to denote affective discord, friction or resistance. Affective confluence and dissonance are not mutually exclusive nor a binary pair; they can occur together or separately to prime people to respond to situations in particular ways, helping explain how the past shows up in the present and filters through into the future (Ahmed Citation2014; Blackman Citation2019; Healy and Morrison Citation2021; Mulcahy Citation2016; Threadgold Citation2020). Understanding affective confluence and dissonance as forces that have the capacity to make, unmake and remake boundaries of technologically mediated learning brings a critical awareness of the boundary work in which affect is implicated and the micropolitics that such boundary work entails.

Data and methodFootnote2

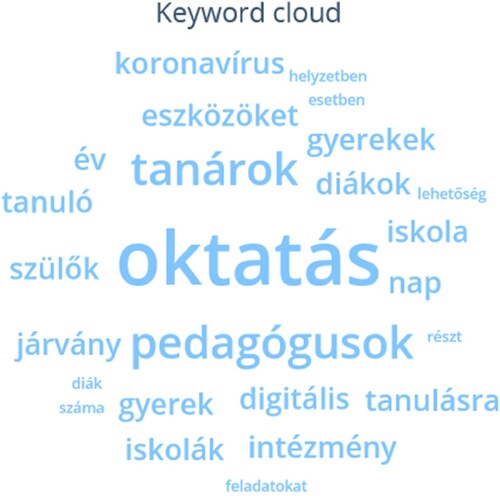

SentiOneTM provides researchers with GDPR compliant AI-based social listening tools along with the computational means to do data analysis, including commercial sentiment analysis. However, the commercial sentiment analysis is not compatible with research informed by sophisticated theories of affect and emotion. We thus repurposed SentiOneTM’s offerings, finding ways to engage with the AI-based tools that enabled a computational attunement to how affect emerges and is expressed as sentiment in everyday social media encounters. The key to success was retaining ‘a human in the loop’ and adopting an iterative approach to designing the search strategy. Our particular search strategy involved pinpointing Hungarian keywords through a preliminary reading of media articles associated with remote learning during Covid-19. Then, after testing the keywords (see for a word cloud of a test search), we further refined our terms, grouping them into two categories: one connected to remote learning (e.g., ‘digital teaching’) and the other with sentiment (‘fury’, ‘difficult’, ‘smooth’, etc.). By manually pairing remote learning words with emotion words, we were able to discard the commercial sentiment analysis offered by SentiOne and instead adopt a hybrid human-computational attunement to affect.

Figure 1. Keyword cloud from initial search. Most prominent words: teaching; teachers; pedagogues; tools; coronavirus; child/children; digital; school; pupils; parents; institution.

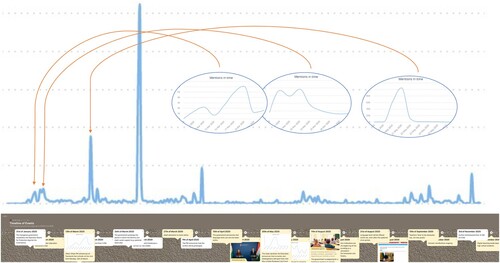

The ‘crawlers’ from our final set of keywords returned approximately 10.000 results, which we further narrowed by focusing on specific time periods. To select the most relevant periods, we created a timeline of Covid-19 announcements (https://doi.org/10.26188/6284ad82dd824) based on the official website of the Hungarian government (koronavirus.gov.hu). Then, using a visualisation tool provided by SentiOneTM that showed the reach of a media event, we mapped social media activity over time onto the timeline (see data visualisation, ), with the reach being derived from an algorithm based on the number of interactions with a post (https://listen.help.sentione.com/docs/reach).

Figure 2. Data visualisation of timeline of events and peaks in social media activity. See https://doi.org/10.26188/6284ad82dd824 for high resolution image of the timeline at the bottom of the figure.

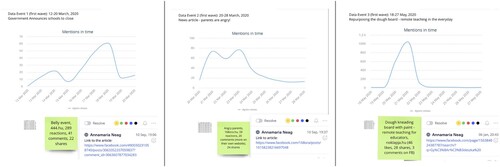

The concept of the event is important when analysing dynamic, affectively charged datasets like those assembled by the SentiOneTM crawlers because the event affords a sense of stable form within a fluid whole (Massumi cited in Anderson and Harrison Citation2012, 19). In relation to what they call ‘Affective Event Theory’ Wakefield and Wakefield (Citation2016) further explain that affect ‘arises in response to an affect-generating stimulus … and emotional expressions (e.g., shame, grief, hope, love) are noticeable evidence that an affective reaction to a stimulus has occurred’ (142). To select the events for analysis, we identified three key timeframes early in the pandemic and three media events which ‘triggered’ a peak in social media responses (see ).Footnote3 Data related to each media event comprised of an online article (e.g., the affect-generating stimulus); social media exchanges shared on Facebook; images; and emojis. Together these data become a ‘data event’.

Figure 3. Screenshots from Miro of selected key time frames showing peaks in social media activity and corresponding media event (https://doi.org/10.26188/19790959)

Multimodal analytic

The multimodal analytic guiding our analysis of the selected data events is adapted from Hunt’s (Citation2015) multimodal analysis of Facebook data. The analytic is broken down into four elements that comprise each data event to form what Kress (Citation2012) refers to as a ‘multimodal ensemble’ (38):

Social actors: with a focus on parents, children, and teachers, and – because of social media’s interactivity – also on commenters/users, van Leeuwen (Citation1996) argues that ‘[…] representations include or exclude social actors to suit their interests and purposes in relations to readers for whom they are intended’ (35). Therefore, we were interested to see which social actors and processes were included/excluded, how these were linguistically presented in the multimedia texts, and how these could be understood as enabling and/or constraining – e.g., become productive of affective dissonance or confluence.

Visual images: with a focus on images shared in the media articles and Facebook posts, analysing specific aspects of visual content, such as composition, colour, or the iconography of images (Machin and Mayr Citation2012), images become an important semiotic resource. They convey a fuller understanding of how remote learning reconfigured the social, technological, material, and affective relations.

Non-linguistic reactions: with a focus on semiotic resources such as likes, emojis and gifs (Breazu and Machin Citation2019; Ledin and Machin Citation2019), somewhat banal reactions become powerful symbols of affect, or as Papacharissi (Citation2015) notes, of ‘affective connectivity’.

Broader social-economic-political relations: with a focus on situating each data event in relation to each other and the broader socio-economic-political context, transpersonal affect sheds light on the power relations shifting and re-arranging the boundaries of learning in a time of digital intensification.

Multimodality extends beyond language-based modes of communication and, as Kress (Citation2012) points out, encompasses affect. Since affect is ubiquitous, our multimodal ensemble does not separate affect but embeds it into all four elements. Performing our analysis, we (1) identified the affective relations ‘in’ each data event and (2) traced the affective dissonances, confluences and broader socio-political conditionsFootnote4 across the four elements comprising the data events. In saying this we note that affect, as a transpersonal force, is not exclusive to a human body, even when it manifests as bodily affect. An affected (human) body – gripped by a ‘sense of energy or mobilisation’ (Wakefield and Wakefield Citation2016, 142) – may respond by leaving an emotionally charged comment or emoji on Facebook, leaving traces of affect. Data thus carry traces of bodily affect, detectable through linguistic and non-linguistic expressions in the media articles and associated comments as well as the accompanying images. In this sense bodies and bodily affect maintains a presence in data, even once the originating individual has left the event. Tracing the presence of affect is a way to account for power and therefore politics.

Data events

In the following we present our analysis of the three selected data events – articles and Facebook posts that present an account of ordinary life in the pandemic that generated an ‘affective pull’ (Mulcahy and Healy Citation2021). Each data event investigates how remote schooling brought to the surface the social, technological, and material relations that configure dispositions (Threadgold Citation2020) towards technologically mediated learning in what is one of the most politically polarised societies in Europe (Bene and Szabó Citation2019). The data events are presented as three standalone data-stories which, to varying degrees, integrate the four elements of our multimodal analysis to generate a narrative arch. Each offers a different take on ordinary experiences of remote schooling in extraordinary times: the first data event focuses on children, parents, and technology; the second on parents and technology; the third then discusses the relationship between teachers and technology.

Data Event 1. ‘The teacher gets up and you can see his belly’

Data Event 1 was initiated by an account of a journalist’s experiences of the first day of remote learning – as a parent. The quote from the title is something his daughter shared with him when discussing the best moments of their first remote day. First published on March 16th, 2020, on 444.hu, a popular anti-government media outlet, the article was then shared on 444.hu’s official Facebook page. The data comprising this data event consists of the article; a photo (see ); 41 comments, 289 ‘reactions’ (likes and laughing emojis), and 22 shares. Facebook, as a communicative infrastructure is ‘set up to enable some, but not other type of social interaction, as is the button ‘like’, affording an immediate and positive response to posts […]’ (Ledin and Machin Citation2018, 20). Facebook offers users the option to express feelings, such as ‘love’, ‘haha’, ‘sad’ or ‘angry’. While this post got 289 reactions, the reactions were only ‘likes’ or ‘haha’ (laughing face emoji), no other ‘off the shelf’ (Jovanovic and Van Leeuwen Citation2018) emotive responses were shared. This may be related to the novelty of the situation, there was no prolonged lockdown yet for people to have negative feelings about. Users found the post amusing, perhaps in an ‘we are in this together’ way? As Stewart (Citation2007) argues:

A world of shared banalities can be a basis of sociality, or an exhausting undertow, or just something to do. It can pop up as a picture of staged perfection, as a momentary recognition, or as a sense of shock or relief at being ‘in’ something with others. (38)

Social actors

The parent-journalist was exposed to school-related activities they do not normally have privy to. This is also true in reverse: parents became vulnerable too, just as teachers were inadvertently drawn into domestic activities. One of the defining sentiments of the text is ‘embarrassment’. This is strengthened by the linguistic expressions of sentiment: ‘motyogtam’ (muttered), ‘elnézéskérést’ (apologise), ‘zavaromban’ (confusion). The journalist-parent finds himself in the unusual situation of gate crashing an MS Teams online class, while searching for the family dog. Feeling out of place was enhanced by technologically mediated scrutiny. The journalist realises that remote learning can cause ‘very personal’ situations. We can see the parent-subject’s struggle (dissonance with school from home) then switched back to the journalist-subject reporting on an unusual situation with habituated ease (confluence with professional practice).

The teacher then is mostly talked about. The journalist reports on the teachers’ actions, digital technologies used, and their struggles with ICTs. He argues for the need to stay relevant and interesting during these pandemic times, leading to a strong reaction from one of the readers, who comments:

To be interesting and relevant??? From Friday to Monday!!! What not! Nothing more natural in this setting!!! This writer blessed with a ‘high-brow’ intellect must know a lot about the everyday life of a school and the complexity of the teaching process. The teacher and his belly. So funny! He really caught the gist of it!

Learn you little bastard, don’t check out the teacher’s belly!  .

.

The broader network of relations: the social-economic-political scene

The Facebook comments convey a polarised Hungarian society, split along the axis of pro – and anti-government. Anger at the government’s handling of the unfolding COVID-19 crisis is present in some of the comments, while others attack the journalist, as he is seen as a representative of ‘Leftist-liberals’:

This is totally characteristic of the Leftist-liberal opposition media … on Friday they were demanding to shut the schools. Then on Friday evening, Orbán [PM] announced that they will and from Monday there will be digital learning … who is going to stay at home with the kids, the whole thing is hasty, by the way what is digital learning, nothing will come out of it.

digital learning started and right now the problem is that ‘AAAAAAAA, IT’SNOTWORKING’! Leftist-liberals, get your **** out of here!

Data Event 2. ‘This teaching equals zero’ (late March 2020)

Data Event 2 revolves around an article titled: ‘Parents in several schools in the capital are upset about the online education that started with the school closures: ‘This teaching equals zero’. The article published in late March 2020 on the website of leftist, anti-governmental weekly 168Óra, presents the largely negative experiences of two parents during the first lockdown. The data event consists of this article; two photos ( and ); 20 comments, 59 ‘reactions’ and 24 shares. The 59 reactions are comprised of more varied expressions than in Data Event 1 with 33 likes, 15 crying face emojis, 6 laughing face emojis, 3 surprised face (wow) and 2 angry face emojis, suggesting the novelty of lockdown is wearing off. Parents’ linguistic expressions of sentiment in the article and Facebook comments would support this. Worried parents ask:

What if I don’t understand it myself?

How can I teach this, if I am not good in it?

Figure 5. Stock image of person behind large stack of books.

Figure 6. Photojournalistic style image of deserted classroom.

The second photo of an uninhabited, traditional classroom () is photojournalistic in style, taking on a history of ‘bearing witness, and being a reliable document, or recording of reality (Ledin and Machin Citation2018, 41). Yet this is also ‘reality interrupted’ (Sontag Citation2004), showing a moment in time but not the complex and messy processes of schooling. The low-level (denoting a power position) but oblique angle, which denotes detachment (it’s not a frontal angle) creates a stark contrast with the intimate parent–child-school-home relations at play in Data Event 1. The ‘meaning potential’, a term that ‘suggests not something fixed, but a possibility’ (Machin and Mayr Citation2012, 51), prompts us to consider the connection between the photojournalistic image and the stock photo to evoke thoughts of the difficulties of learning without pedagogic support, the absence of person to person interactions, and a presence of Covid-19 induced social distancing.

Social actors

Parents’ share views of their children, saying ‘the fifth grader cannot learn because there was no discussion about remote teaching at the school’. The parent worries because she does not know where to send her child’s homework, asking ‘How will he [the teacher] know that he wrote it?’. As the school moves into the home, assessment and fraud becomes a focus of parents. The importance of (correct) evaluations seems heightened, not dismissed during this period, showing a confluence with neoliberal practices such as standardised testing and competition along with an emphasis on accountability. This is countered by later comments saying education should be more geared towards survival not assessment:

But what the hell is there to grade in the first week of such a sudden changeover??

It should be left to children to set up an online platform (Moodle, Discord, Goggle Classroom, etc.)

They started struggling with KRETA [official educational platform] so the kids have now switched teachers to Google.

Right now parents are teaching the children, but by the time this shit is over, all the parents will be going to the psychiatric hospital, to the empty containers that Orbán [the PM] is now putting up [for Covid patients].

How many days has it been? In all that time, what new and beautiful things has the kind parent built? The kind parent should rather help than freak out. Doing something is hard, freaking out is easy.

Daddy should search for help on Google instead of swearing … Ask for help from the educators … or something

The broader network of relations: the social-economic-political scene

Threaded through the Data Event is a critique of the Hungarian education system’s preparedness for remote learning, with reports of the KRÉTA platform crashing frequently and only available during afternoons. As Szabó, Buda, and Erdei (Citation2020) and Grajczjár, Schottner, and Szűts (Citation2021) argue, the educational digital revolution happened overnight in Hungary, without a systematic planning, and it caught educational stakeholders off guard. The heightened anxieties around ‘learning loss’ are summed up by a mother’s exclamation: This teaching amounts to zero. The next year will certainly start with the students making up for these three months. Compounding factors include parents and teachers being ‘pitted against each other’, parents not having the capacity to ‘get off their arses and help the kids’, and unequal access to digital technologies, as noted in the following Facebook comments:

Parents have already been pitted against the teachers, who have solved the problem from scratch in a couple of days without any central help. … But note, online education requires parents to get off their arses and help the kids. This distance education in developed countries works by one parent helping.

Overall, parents feel left on their own, not to mention families who do not have digital tools, even if online education is launched as promised. The biggest problem is that neither teachers nor parents have received practical training in distance learning.

Data Event 3 – Kneading board with chalkboard paint (late May 2020) – teachers and technology

The third data event is comprised of an article titled ‘Kneading board with chalkboard paint – distance learning does not spare teachers either, published mid May 2020 on a popular women’s magazine website (noklapja.hu). The article was shared on their official Facebook page, receiving 46 likes, 3 comments and 28 shares. The relative lack of emotive responses (e.g., no ‘wow’ or ‘angry’ emojis) may be explained by this article being shared on a lifestyle magazine’s Facebook page as research shows that politically inflected media attracts more heated debate (Szabó, Zoltán, and Molnár Emese Citation2021). However, the text is not depleted of sentiment, linguistically there is a plethora of feelings expressed: ‘kihívás’ (challenge), ‘hatalmas teher’ (huge burden), ‘fáradtság’ (tiredness), ‘igazságtalan’ (unfair), ‘morcosan’ (grumpy).

The photo accompanying this article () is again a staged stock photo in which we find a blurred image of a young person handwriting and watching their laptop. As if it were an image in an image, we can see a teacher giving an online class. We find several objects used to signify an ideal online education setting: no connection issues, good hardware, one child/computer, no making do with a kneading board and chalkboard paint. It seems like a relaxed learning environment, in stark contrast with what the article describes. The focus of the photo is on the laptop and the teacher, with the laptop occupying a symbolic and central role. The teacher is made salient as everything else is out of focus. This draws us closer to her: a teacher in semi-professional attire, with youthful hairstyle, all in all someone who is in control. This is an interesting choice as much of the article presents the struggles of teachers as borders collapsed around them.

Social actors

It is not only borders between school, home and workplaces that collapsed (as we saw in Data Event 1), but teachers’ position of authority was also challenged as they struggled to translate their face-to-face pedagogic experience into the online world – a world with which many teachers did not have a positive affective affinity. This seemed more pronounced for older teachers, as one late career teacher explains:

I can't go and see if they've written it down well, if they've solved the problem well, because a lot of times they can't even see what I'm writing. I've tried everything in vain – I've even covered my kneading board with chalkboard paint and put it on a ladder – if the child can only follow the lesson on a smartphone screen, they won't see it.

The most tiring thing is that the roles change from minute to minute: one minute I'm a mother, the next I'm a teacher, the third I'm a cook, it can be very tiring.

As with the previous data event, children are only talked about. They are described by teachers as being exhausted, frustrated, and angry because of the Covid-closures. Children are also blamed for plagiarising and not engaging in remote schooling:

it can't be a coincidence that people who used to fail physics are now getting straight A's. To avoid the trap of copying and plagiarism, for a while I asked them to handwrite their presentation notes and photograph them, but many students don't have the tools to do that either, not just me.

The broader network of relations: The social-economic-political scene

Parents and teachers critique the government and the educational system’s lack of preparedness for technologically mediated learning. Connected to this is the discussion relating to trust, accountability, and control. As one of the teachers interviewed for the article aptly points out:

[…] the biggest challenge is that Hungarian offline education is not fundamentally based on trust, but on control and accountability, and online education cannot work without trust.

Covid-19 not only troubles longstanding asymmetries in relations of trust and control, but it also reconfigures our perception of time. Time arises repeatedly: teachers complain about the time spent setting up tests, the time needed to create a 30-minute video, or the burden of managing parents. However, references to time did not always carry negative connotations. Rather it was also associated with a positive disposition to being available to appreciate everyday life with children: finally, parents have the time to spend with the kids and co-create something (e.g., during an online arts and crafts class), as they are not rushing to extra classes (a middle-class preoccupation). This is an unexpected outcome of ordinary affect – settling into a slower, less hectic routine – making time to exist in kid-time rather than structuring it with an adult perception of time.

Discussion

Having presented a curated selection of data, we now explore how certain ‘taken for granted’ boundaries were exposed during the Hungarian Covid-closures, and with what effects. In so doing, we focus on two interrelated themes that emerged from our analysis: escaping the boundaries of bodies and escaping the boundaries of the subject. We can look at big data patterns and explore relationships between micropolitics (e.g., ordinary affects) embodied and embedded in everyday practices and the macro-politics of a data event. The ability to zoom in and out of data, to ‘walk’ around data and come to know data as simultaneously big and small comes with certain practical challenges and considerations: How to select or discard data within the event? This question underpins our tracing of affective dissonance and confluence in the multimodal account presented above. It also provides a method for enacting a transversal analysis which, while embedded in a singular time, place and language still offers insights into the boundary work and practice work (Zietsma and Lawrence Citation2010) involved when boundaries are redrawn to make new configurations of networked and technologically mediated schooling possible.

Escaping the boundaries of bodies: bodies out of place

Bodies, understood in terms of affect are not ‘closed psychological and biological systems’ but ‘open, participating in the flow or passage of affect’ (Blackman Citation2012, 2), with that flow of affect shaping and being shaped by the bodies that are caught up in the network of relations through which it moves. In Data Event 1, teacher-bodies and parent-bodies kept finding themselves out of place (a teacher’s belly in a child’s bedroom, a parent disrupting a synchronous class while looking for the dog) as they found themselves (re)positioned in a network of social, material and technological relations that comprised remote learning. The parent’s embarrassment at crossing a line by entering the ‘classroom’ unannounced (‘zavaromban’, ‘motyogtam’, ‘elnézéstkérést’) is not unrelated in tone to Facebook comments about the undisciplined body of the teacher making its presence felt in the virtual classroom in an unexpected (wrong) way, resulting in the comment ‘Learn you little bastard, don’t check out the teacher’s belly!  ’ The uneasy mix of humour with a sense of inappropriateness nods to the affective dissonance with the changed rules and realities of schooling – and the increased scrutiny of everyday moments that might ordinarily pass us by. The teacher's belly breaks norms and expectations of how teachers ‘should’ appear / dress / behave while being drawn into the public sphere for comment in an uncomfortably intimate way. It makes salient the idea of embodiment never being a private (singular) affair, but ‘always already mediated by our continual interactions with other human and non-human bodies’ (Weiss cited by Blackman Citation2012, 13).

’ The uneasy mix of humour with a sense of inappropriateness nods to the affective dissonance with the changed rules and realities of schooling – and the increased scrutiny of everyday moments that might ordinarily pass us by. The teacher's belly breaks norms and expectations of how teachers ‘should’ appear / dress / behave while being drawn into the public sphere for comment in an uncomfortably intimate way. It makes salient the idea of embodiment never being a private (singular) affair, but ‘always already mediated by our continual interactions with other human and non-human bodies’ (Weiss cited by Blackman Citation2012, 13).

Not only did bodies that were being kept in place (by lockdown) find themselves out of place they could also no longer engage in regular (and regulating) face to face practices of teaching. As a teacher and mother of two young children explains in Data Event 3, she cannot connect with the pupils as she usually would and does not meet the eyes of pupils. It does not mean, however, that the practices of teachers and learners are no longer embodied and embedded, it is just that the embodying and embedding happens differently when learning is largely relocated to a digital site. This becomes a question of (in)expertise and (in)experience with engaging digital pedagogies. Digital pedagogies are multifaceted and take educators years to build. They cannot fulfil their potential if only seen as part of a ‘frontline emergency service’ (Williamson, Eynon, and Potter Citation2020). It would be wrong to conflate intentional digital pedagogies with pandemic pedagogies which occurred as an emergency response to a public health crisis. Some teachers did succeed in translating their curriculum and pedagogy into online platforms during the pandemic though. A study from the European Commission (Citation2020) offers some insight, finding that younger teachers were in a better position to respond to the demands of remote learning because they are more likely to have been exposed to digital technologies in their education, and they might be more eager to undertake continuous ICT professional development – creating a more positive affective affinity with remote learning. This may help also explain the findings that Hungarian teachers, who reportedly received a significant amount of IT training and are familiar with digital education, have varied methodological and pedagogical knowledge (Malatyinszki Citation2020).

Other studies found that students felt the transition was harder for teachers who had been in the profession for longer while parents reportedly faced the biggest challenge during the remote learning period (Bíró Citation2020; European Commission Citation2021). Similarly, our study is also shot through with parents’ struggles – revealing that expectations were not easy to meet, even for parents who would presumably be well-placed to adjust to remote learning because they are accustomed to ‘the rules of the game’, e.g., those who live in a professional middle-class family with excellent access to networked digital technology and whose children attend well-resourced schools with a history of edutech integration. What this indicates is that parental dispositions associated with children’s use of networked digital technologies for learning may predict whether an initiative will succeed. Threadgold (Citation2020) might argue that this is because parents’ dispositional make-up primes them to respond to the situation in predictable ways. This then raises the question of what sorts of dispositions create optimal conditions for children’s use of networked digital technologies when learning from home? Or put more simply, how might Daddy be capacitated to ask Google for help instead of swearing?

Escaping the boundaries of the subject: a politics of trust and control

The sudden switch to remote learning and the additional school-related responsibilities that came with it forced a reconfiguration of the parent-subject. One parent asks, ‘How can I teach this, if I am not good in it?’ amid decries that ‘THIS IS NOT WORKING’. While it was not all bad – parents say they appreciate really seeing what their children do at school – the added pressure to become teacher was overwhelming for many. The subsequent blurring of boundaries was felt acutely by a teacher-mother (Data Event 3) who speaks about her constantly shifting subjectivity in terms of constantly changing roles (a mother, a teacher and a cook). Accompanying the emotional labour of the destabilised parent-teacher subject – without the usual boundaries – is the question of what kind of subjects parents-teachers-learners may become as they come into relation differently through technologically mediated schooling? There is resistance to the reconfiguration of the parent-subject, with boundary work (Gieryn Citation1983) occuring as a reinscription of the boundary under threat. The Facebook post, It is NOT for parents to teach, ask teachers for help marks out the identity of the teacher and the teaching profession, separating teacher work from parenting work. This reaction, according to Braidotti (Citation2018) who understands identity as an effect of power, is an indicator of resistance to a change in the power dynamic that arises when parents become teachers.

Again, the teacher-parent from Data Event 3 offers a way to see through the teacher/parent binary, showing that it is possible for the reshaping (hybridising) of parent-teacher subjects through shared experiences of remote schooling to have a positive aspect, saying she thinks it is important to see that behind every half-hour video the teacher sends out, there are hours of work: And if we can see the mutual investment of energy and the extra workload that this period puts on everyone, it might also strengthen the relationship of trust between teacher and student, teacher and parent, parent and child. She pinpoints the trust-control relation as being a significant factor in the relative success of remote schooling, saying that as a teacher: the biggest challenge is that Hungarian offline education is not fundamentally based on trust, but on control and accountability, and online education cannot work without trust. The teacher-parent suggests the neoliberal big ‘P’ politics of the education system, which exercises control via an emphasis on competition, individualism and accountability, filters into the little ‘p’ politics of everyday classroom interactions (e.g., ordinary affects) by diminishing trust – which did not optimise the conditions of remote learning.

Reed (Citation2001, 202) suggests that ‘trust/control relations are most usefully conceptualised as analytically distinctive but mutually conditioning elements within emergent structures of “positioned-practices”’. That is, control and trust relations form in everyday situated practices. When these relations shift, e.g., when teachers and students no longer occupy the same physical space or parents take on supervision of learning, new ‘expert power’ may be generated, and the locus of control goes elsewhere. A destabilisation of the balance of control and trust was accompanied by anxieties about ‘learning loss’ and suspicion of student plagiarism. In the absence of trust, students exert their power to work-around assessment tasks. Previously stable trust-control relations of in-person schooling became much more volatile when learning moved online. Arguably, teachers who had a positive affinity with an online learning environment emphasising trust and, conversely, did not ordinarily engage in pedagogies that rely on a high degree of control, were in a better position to foster the conditions for students to do remote learning well. Enhancing interpersonal trust with a view to realising the potential of technologically mediated learning in schools may also provide a degree of protection from the rise in digital practices threatening relations of trust by providing a means to put dis-trust at the heart of the teacher-student relation and reify control via digital surveillance tools (e.g., through learning analytics or plagiarism software).

Concluding thoughts

We suggest that micropolitics of trust and control are an obscured aspect of boundary-related work of social actors, mediating technologies, systems and the practices they partake in that make, unmake, and escape boundaries. The pandemic-related school closures in Hungary made these micropolitics tangible. The shift in power dynamics offered non-formal, non-hierarchised learning opportunities that decomposed boundaries defining the who, what, where and when of schooling. As boundaries became compromised, they ceased to structure everyday practices of schooling, creating the conditions for boundary escape to occur. Meanwhile, a lack of shared understanding of what technologically mediated learning from home entails heightened instability and uncertainty. The affectively charged responses presented in the article show the reactions of social actors when placed into this very much unwanted situation: a world of tensions, dilemmas, and possibilities. Without digital technologies all this would have been unthinkable. And yet technology did not drive digital intensification, the government response to a public health crisis did.

The occasion offered learning opportunities for teachers – albeit they were not asking for them – in terms of digital literacies and pedagogies. It also offered co-learning opportunities for parents and children alike in the non-formal learning setting of the home. The significance of trust and control for realising the potential of such opportunities has critical implications for future educational practice. Not only does it illuminate the type and distribution of relations that can enhance digital dispositions and capacities, but it also suggests how to cultivate them via teamwork, collaboration, and (re)negotiation of power dynamics; prompting the consideration of digital literacies as transdisciplinary practices performed by a variety of actors that are ‘more than mere users’ (Scott Citation2022). The (re)negotiation of power dynamics is crucial, with much to be gained by democratising the classroom through the adoption of practices that strengthen trust while reducing the reliance on practices designed to control or surveil. To achieve this children and adults need opportunities to establish shared practices in protected spaces (e.g., away from public scrutiny of the media). We propose that the creation of protected spaces for safe risk-taking and experimentation with shared digital practices will prompt positive dispositional shifts to, for example, enable Daddy to ask Google for help instead of swearing and potentially benefit a range of actors within and beyond the school community.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for the Digital Child for introducing the researchers and providing critical feedback on early drafts of this paper. We would also like to thank the reviewers for their insightful critique, enabling us to strengthen and streamline the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 More on this tool: www.sentione.com

2 This research received ethics approval from the Commission for Ethics in Research, Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University. The data comes from publicly available Facebook pages and news websites. All information tracible to social media users (author IDs) were anonymised. The data were also translated from Hungarian into English, adding another layer of protection.

3 There were several peaks in social media activity and corresponding media to select from. However, there is not the scope to report on more for this article. We therefore curated three events that together would convey the ordinary affects arising during pandemic life and enable us to trace their effects over time.

4 The concept of affective dissonance, confluence and their relation to broader socio-political conditions can be mapped onto Kress’ (Citation2012) thinking around textual incoherence, coherence and what these say about social order.

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2014. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. NED-New ed. 2. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Anderson, Ben., and Paul. Harrison. 2012. “The Promise of non-Representational Theories.” In Taking-Place [Electronic Resource]: Non-Representational Theories and Geography, edited by P. D. Harrison, and B. D. Anderson, 1–34. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Ltd. 34 pages.

- Bene, Marton, and Gabriella Szabó. 2019. “Bonded by Interactions: Polarising Factors and Integrative Capacities of the News Media in Hungary.” Javnost - The Public 26 (3): 309–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2019.1639427.

- Bíró, Gyula. 2020. “A Hazai Digitális Távoktatás Tapasztalatai a Covid-19-es Járványhelyzet Időszakában egy Kvalitatív Felmérés Tükrében.” In Fejezetek a COVID-19-es Távoktatás Digitális Tapasztalataiból., edited by Gábor Kozma, 18–41. Szeged: Gerhardus Kiadó.

- Blackman, Lisa. 2012. The Subject of Affect: Bodies, Process, Becoming. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446288153

- Blackman, Lisa. 2019. “Haunted Data, Transmedial Storytelling, Affectivity: Attending to “Controversies” as Matters of Ghostly Concern.” Ephemera: Theory & Politics in Organization 19 (1): 31–52. https://ephemerajournal.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/contribution/19-1blackman%20(1).pdf.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1990. The Logic of Practice. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Braidotti, Rosi. 2018. “Affirmative Ethics, Posthuman Subjectivity, and Intimate Scholarship: A Conversation with Rosi Braidotti.” In Decentering the Researcher in Intimate Scholarship, 179–188. Emerald. 9 pages.

- Breazu, Petre, and David Machin. 2019. “Racism Toward the Roma Through the Affordances of Facebook: Bonding, Laughter and Spite.” Discourse & Society 30 (4): 376–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926519837396.

- Engler, Ágnes. 2020. “Távolléti Oktatás a Családok Aspektusából.” Civil Szemle, no. Special Issue. http://www.civilszemle.hu/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/CSz-ku%CC%88lo%CC%88nsza%CC%81m-20201.pdf.

- Engler, Ágnes, Valéria Markos, and Ágnes Réka Dusa. 2021. “Szülői segítségnyújtás a jelenléti és távolléti oktatás idején.” Educatio 30 (1): 72–87. https://doi.org/10.1556/2063.30.2021.1.6.

- European Commission. Joint Research Centre. 2020. The Likely Impact of COVID-19 on Education: Reflections Based on the Existing Literature and Recent International Datasets. Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760126686.

- European Commission. Joint Research Centre. 2021. Emergency remote schooling during COVID-19: A closer look at European families, Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760613798.

- Eurostat. 2019. Living conditions in Europe - income distribution and income inequality. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Living_conditions_in_Europe_-_income_distribution_and_income_inequality&oldid=585980.

- Fox, Nick J. 2011. “Boundary Objects, Social Meanings and the Success of New Technologies.” Sociology 45 (1): 70–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038510387196.

- Gieryn, Thomas F. 1983. “Boundary-work and the Demarcation of Science from non-Science: Strains and Interests in Professional Ideologies of Scientists.” American Sociological Review, 781–795. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095325.

- Grajczjár, István, Krisztina Schottner, and Zoltán Szűts. 2021. “A Digitális Távoktatás Felsőoktatási Tapasztalatai: Milyen Tényezők Magyarázzák a Blended Learning Támogatottságát?” Opus et Educatio 8 (2), https://doi.org/10.3311/ope.433.

- Healy, Sarah, and Caroline Morrison. 2021. “The Gadfly: A Collaborative Approach to Doing Data Differently.” In Teacher Transition into Innovative Learning Environments, edited by Wesley Imms, and Thomas Kvan, 139–150. Singapore: Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446288153

- Hunt, Daniel. 2015. “The Many Faces of Diabetes: A Critical Multimodal Analysis of Diabetes Pages on Facebook.” Language & Communication 43: 72–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2015.05.003.

- Jovanovic, Danica and Van Leeuwen, Theo. 2018. “Multimodal Dialogue on Social Media.” Social Semiotics 28 (5): 683–699. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2018.1504732.

- Kress, Gunther. 2012. “Multimodal Discourse Analysis.” In The Routledge Handbook of Discourse Analysis, edited by James Paul Gee, and Michael Handford. Routledge. see https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203809068.ch3.

- Ledin, Per, and David Machin. 2018. Doing Visual Analysis: From Theory to Practice. London: Sage.

- Ledin, Per, and David Machin. 2019. “Doing Critical Discourse Studies with Multimodality: From Metafunctions to Materiality.” Critical Discourse Studies 16 (5): 497–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2018.1468789.

- Machin, David, and Andrea Mayr. 2012. How to Do Critical Discourse Analysis: A Multimodal Introduction. London: Sage.

- Mulcahy, Dianne. 2012. “Affective Assemblages: Body Matters in the Pedagogic Practices of Contemporary School Classrooms.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 20 (1): 9–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2012.649413.

- Mulcahy, Dianne. 2016. “‘Sticky’ Learning: Assembling Bodies, Objects and Affects at the Museum and Beyond.” In Learning Bodies, edited by Julia Coffey, Shelley Budgeon, and Helen Cahill, 2:207–222. Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Mulcahy, Dianne, and Sarah Healy. 2021. “Ordinary Affect and Its Powers: Assembling Pedagogies of Response-Ability.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society, July, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2021.1950201.

- Mulcahy, Dianne, and Maree Martinussen. 2023. “Affecting Advantage: Class Relations in Contemporary Higher Education.” Critical Studies in Education 64 (2): 168–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2022.2055595.

- Papacharissi, Zizi. 2015. Affective Publics: Sentiment, Technology, and Politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Reed, Michael I. 2001. “Organization, Trust and Control: A Realist Analysis.” Organization Studies 22 (2): 201–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840601222002.

- Scott, Anne-Marie. 2022. “Digital transformation and why it can’t be done without learning technologists.” In Brain-fluff (blog). May https://ammienoot.com/brain-fluff/digital-transformation-and-why-it-cant-be-done-without-learning-technologists/.

- Sontag, Susan. 2004. “Regarding the Torture of Others”. New York Times Magazine, May 23. https://monoskop.org/images/a/af/Sontag_Susan_2004_Regarding_the_Torture_of_Others.pdf.

- Stewart, Kathleen. 2007. Ordinary Affects. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Szabó, József, András Buda, and Gábor Erdei. 2020. “A Pandémiás Helyzet Hatása az Oktatásra a Debreceni Egyetemen.” Opus et Educatio 7 (4), https://doi.org/10.3311/ope.410.

- Szabó, Gabriella, Kmetty Zoltán, and K. Molnár Emese. 2021. “Politics and Incivility in the Online Comments: What is Beyond the Norm-Violation Approach?” International Journal of Communication 15 (2), https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/16411/3403.

- Szilard, Malatyinszki. 2020. “A digitális oktatás megélése.” https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.36400.38408.

- Threadgold, Steven. 2020. Bourdieu and Affect: Towards a Theory of Affective Affinities. 1st ed. Bristol University Press. https://doi.org/10.46692/9781529206630

- Threadgold, Steven. 2021. Keynote at Annual Conference of Youth Studies, Finnish Youth Research Society and University of Helsinki. November 5, 2021. https://youtu.be/xMx4BsfSh1U

- van Leeuwen, Theo. 1996. “The Representation of Social Actors.” In Texts and Practices: Readings in Critical Discourse Analysis, edited by Carmen Rosa Caldas-Coulthard, and Malcolm Coulthard, 32–71. London: Routledge.

- Wakefield, Robin, and Kirk Wakefield. 2016. “Social Media Network Behavior: A Study of User Passion and Affect.” The Journal of Strategic Information Systems 25 (2): 140–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2016.04.001.

- Williamson, Ben, Rebecca Eynon, and John Potter. 2020. “Pandemic Politics, Pedagogies and Practices: Digital Technologies and Distance Education During the Coronavirus Emergency.” Learning, Media and Technology 45 (2): 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1761641.

- Zietsma, Charlene, and Thomas B. Lawrence. 2010. “Institutional Work in the Transformation of an Organizational Field: The Interplay of Boundary Work and Practice Work.” Administrative Science Quarterly 55 (2): 189–221. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2010.55.2.189.