ABSTRACT

Media literacy education in Australia is underpinned by the key concepts of media education: technologies, representations, institutions, audiences, languages and, more recently, relationships. The conceptual approach to media literacy education continues to offer a way for teachers and students to critically examine the media. In Australia, this usually occurs through the subject strand of Media Arts; however, little research explores how the concepts are used in primary school classrooms. This study investigates how the key concept of ‘technologies’ was enacted in three primary school classrooms. A case study methodology was employed to gain insight into how teaching and learning experiences develop an understanding of the concept of ‘technologies’. A thematic analysis determined that the concept of ‘technologies’ was explored in the case study classrooms. However, technology was used as a tool to complete tasks rather than a nuanced examination of how technology enables and constrains production and distribution.

Technological developments over the past decade or so have made the ability to create, view and participate with media more straightforward than in the past. They have also, to some degree, made technology used in media production less explicit. This paper addresses the key concept of ‘technologies’ for media education in a time of rapid technological change. In a Media Arts classroom, the Australian version of media studies taught from primary through to secondary school, the technology used in the past was visible and tangible to students and teachers. Now students can work on a single device, such as a tablet, that provides scope to capture video, record sound, write and deploy code, and share creations and works-in-progress nearly instantaneously. This has made technologies, especially software and platforms, less visible to students and teachers (Apps, Beckman, and Howard Citation2023). Understanding the technology involved in media production, how it is developed, how to use it, and its impact on our viewing and distribution practices are all increasingly important aspects of ‘technologies’ as a key concept of media literacy education.

The relationship between technologies and media production is not new. However, it is more complex as current and emerging technologies shift our media practices away from mass media production to different forms of communication. There are calls for the next iteration of media literacy education, or as Ptaszek (Citation2020) has called it, Media Education 3.0. In this paper, I present the findings of three case studies focused on the use of ‘technologies’ as a concept in primary school classrooms. Despite the case study classrooms all engaging with the concept of ‘technologies’ to varying degrees, there was a focus on technical skills. This is somewhat unsurprising given primary school teachers in Australia do not usually receive formal education or training in Media Arts (McKenzie et al. Citation2014). I argue here not for the next phase of media literacy education, but for researchers and educators to return to our conceptual frameworks and question how we can more deeply consider our current concepts in the classroom. For the concept of ‘technologies’, this means moving beyond technical skills and considering how technology enables and constrains production and dissemination through social and cultural practices (du Gay et al. Citation1997). This includes engaging with the systems used for production and distribution (de Groot, de Haan, and van Dijken Citation2023), the platformitisation and datafication of daily life (Sefton-Green and Pangrazio Citation2022) and algorithms (Jacques et al. Citation2020; Valtonen et al. Citation2019).

The research discussed in this paper was framed by the question, ‘How is the Media Education key concept of ‘technologies’ enacted in classroom practice?’ I examine how the key concept of ‘technologies’ is currently explored in Australian primary school classrooms where the Australian version of media education, known as Media Arts, occurs. Firstly, I outline the conceptual approach to media literacy education and examine the concept of ‘technologies’ in more detail. Next, I outline the approach to the study, including the methodology and the participants of the case studies selected for the research. I describe the data collection and analysis procedures before presenting each case study. I conduct a thematic analysis of the data and outline how the concept of ‘technologies’ is unevenly implemented in primary school classrooms. Much of the media literacy education research focuses on secondary classrooms. This research examines how primary school teachers and students talk about and enact practices that help researchers understand how the key concept of ‘technologies’ is understood.

The conceptual approach

Media Arts education in Australia is underpinned by the key concepts of media education, aligning with media literacy and media education in the UK (Masterman Citation1985; Buckingham Citation2003) and Canada (Jolls, Walkosz, and Morgenthaler Citation2013). Instead of outlining a set of competencies for students to master, a conceptual framework helps students develop broader understandings they can apply as media cultures and technologies change in the future (Buckingham Citation2013; Bazalgette Citation2010; Poyntz Citation2015). A conceptual approach is distinctive from the process model to media literacy education. In a process model specific actions are undertaken to create and analyse media, while a conceptual approach affords opportunities to examine the media through textual and contextual components that relate to how the media is produced, distributed and consumed in our everyday lives (Dezuanni Citation2020). The concepts can be explored through media production and analysis (Partington and Buckingham Citation2011). In Australia the key concepts are ‘technologies’, ‘representations’, ‘audiences’, ‘institutions’, ‘languages’, and more recently include ‘relationships’ (ACARA Citation2022; Australian Media Literacy Alliance Citation2020; Dezuanni Citation2020). Although these concepts are outlined in curriculum documents, there is little research about how Australian primary school teachers apply these in classroom settings. It should also be noted that the concepts do not exist singularly in any media production. Rather they build on and inform each other. For example, a recent addition to the Australian Curriculum, the concept of ‘relationships’, considers the relationship between people through technology and people with technology. These ideas may be dealt with as part of the ‘technologies’ concepts in parts of the world, and indeed are interrelated in many ways that can be difficult to distinguish. In this paper I discuss a discreet concept, that of ‘technologies’ as a way to examine classroom practice and consider how teachers and their students can be more equipped to challenge the notions of technology as a stable and determined entity.

Concept of ‘technologies’

Central to the concept of ‘technologies’ is the notion of critically reflecting on how technology shapes media production (Buckingham Citation2003) and the social, political, economic and cultural contexts in which technology is developed (Buckingham Citation2019). Social and cultural practices shape, and are shaped by, technology due to technological changes to production and distribution methods (du Gay et al. Citation1997), with the boundaries between human and technological activity no longer dinstinguishable (Jandrić et al. Citation2018). The technologies that students use have been designed by humans for specific purposes, with biases knowingly or unknowingly built into the technologies (Stoddard Citation2014) that are often not clearly visible to users (Knaus Citation2020). The technology we use is not neutral but rather enables or constrains particular choices of the user (Buckingham and Burn Citation2007; Williamson Citation2017) through human and industry-created, but technology-mediated, algorithms (Dezuanni Citation2021). When engaging with the concept of ‘technologies’ in classrooms, teachers can challenge and provide opportunities for students to use technologies in ways that disrupt preconceived notions about technology use (Marsh et al. Citation2019; Parry and Taylor Citation2021).

The skills involved in using technology to create media are essential, but only one aspect of the concept of ‘technologies’. Developing media literacy is more nuanced than being proficient with media technology (Buckingham Citation2019). Within the concept of ‘technologies’ there is scope for children to learn technical and procedural skills about how to make the media and how the media is made, not just ‘technology learning for its own sake’ (Poyntz et al. Citation2020). As a fundamental component of media production (Hoechsmann and Poyntz Citation2012), students still need to learn how to use technology effectively for their production.

The concept of ‘technologies’ does not only refer to digital technology. In a classroom, students may access digital and non-digital technologies (Bazalgette Citation1992). Despite this, the process of modern media production will always require the use of digital technology. Students’ opportunities to develop a deep understanding of the concept of ‘technologies’ are impacted when they lack access to digital technology. Dezuanni (Citation2015) argues that using digital materials alongside media concepts provides opportunities to develop media literacy through producing and analysing media artworks. It is possible to focus on the material or the conceptual. However, deeper understandings can advance as the building blocks of digital media literacy are considered together.

At the time of this study, the Australian Curriculum: The Arts encouraged teachers to use ‘ … technologies which are essential for producing, accessing and distributing media’ (ACARA, n.d., para. 11). Schools and teachers have the flexibility to use technology as they see fit or have available. This study investigates how the concept of ‘technologies’ is addressed in classes where Media Arts teaching and learning occurs.

Methodology

A case study methodology (Stake Citation1995; Merriam and Tisdell Citation2015) was used to investigate the research question ‘How is the Media Education key concept of ‘technologies’ enacted in classroom practice?’ This was part of a broader doctoral study that examined primary teachers’ engagement with the five concepts included in the mandated national curriculum at the time. Here I focus on the concept of ‘technologies’ to explore how students developed understandings of the concept during a unit of work.

Participants

The three teachers of the cases were purposefully sampled to ensure they included some form of Media Arts teaching and learning in a unit of work. Of the three, one teacher did not explicitly recognise they were undertaking Media Arts in their curriculum planning. Each case was selected to provide insight into Media Arts education across various schooling years: a Year 1 class, a Year 6 class and a composite Year 5/6 classFootnote1, each in a government school in a metropolitan area just outside of a capital city. According to data available about the schools, they all have high levels of education advantage (ACARA Citation2018), and the schools are located in areas where the income is higher than the national average. The schools have varying levels of diversity. Two schools had slightly more students from a language background other than English, but all three schools had a limited number of students who identified as Aboriginal people or Torres Strait Islander people, the First Nations people of Australia. The findings of this study are not representative of all classrooms. Instead, the study provides insight into the research question based on the classrooms that agreed to participate in the research.

Data collection

Data were collected over each class’s unit of work as outlined in . The units of work ranged from five to ten weeks, and I observed four lessons across each unit. All the units featured some form of what the curriculum documents call making – a form of production work. Before the commencement of the fieldwork, I conducted semi-structured interviews with the teachers lasting between 30 and 45 minutes. After each lesson, where time allowed, I undertook shorter semi-structured interviews to clarify observations. Student interviews occurred throughout my visits. These interviews were less formal, often occurring as the student worked or as we looked at their class work together. I also collected physical artefacts, including planning worksheets and copies of productions where possible. While these helped to inform and focus the analysis, they were not explicitly analysed for this study.

Table 1. Data collected at each case study site.

Data analysis

A thematic analysis was undertaken, selected to help understand and represent the classroom experience across the dataset. Although the key conceptual framework is not a theory per se, the key concepts informed the analysis through a deductive approach to coding the data (Braun and Clarke Citation2022). Each case, including the associated interviews and observations, was coded and analysed separately. After this phase, the three cases were examined together to explore what reoccurring themes were apparent that related to ‘technologies’. Drawing on the literature concerning the key concepts of media literacy education and with a considersation of their importance to the Australian Curriculum, I determined there was an uneven implementation of the key concepts, including ‘technologies’, although the reasons behind why this occurred differed across the cases. This theme was reviewed across the three cases to ensure it was valid (Braun and Clarke Citation2022) and as per the thematic analysis model used, I acknowledge that the theme is influenced by my own position as a researcher. While the three teachers all discussed technology in some way in their initial interviews, it was clear through interview and observation data that their understanding of the concept of technologies was limited to technical understandings.

Case 1: technical skills at the forefront

The participants of the first case study included two classes of Year 5 and 6 students and their teacher, Dave. Dave was a specialist teacher who taught a subject called Digital Media Arts. He took each Year 5/6 composite class for a one-hour weekly session to provide the subject and teaching relief to the classroom teacher. Dave had some previous Media Arts experience, but much of his expertise and interest was in the use of digital technology. The students of the two classes involved in the study undertook a unit of work using the online block coding program Scratch (MIT Citation2013). The students had varying levels of spontaneous knowledge (Buckingham Citation2003), or prior experience, with Scratch, which ultimately impacted how the students worked with the technology.

In his initial interview, Dave explained the type of Media Arts work he had undertaken before with students:

So, a lot of our initial media arts was, you know, information reports via PowerPoint, then a move to slides, then we were looking, well how can we be more creative and do these things? So, then they started designing websites, then we started looking at green screens and how can we make this better? Look at the quality work. So, movies came in, trailers came in.

Throughout the unit of work, students could create an animation or video game using Scratch. They could decide upon the content, as long as it was appropriate for a school context and conformed to narrative conventions. For some students, Scratch was a new technology. Others had some experience, using the program at home or in other contexts. It was observed that students explored the software at their own pace, with little instructional teaching occurring throughout the unit. This prevented some students from fully expressing their ideas as they lacked the technical skills to use the program effectively.

During the first lesson observed, Dave briefly discussed some of the project's requirements, including limiting text on the screen in favour of sound. Dave asked the students, ‘What am I testing you on?’ The students responded with the answer ‘IT skills.’ From the outset, there was a clear focus on using digital technologies in the class. However, there was also some focus on narrative production. Together the class discussed what makes a good piece of work in Digital Arts. The students decided the project should have a complication, a narrative that makes sense, good graphics, and it should be appropriate for school, only some of which is related to the ‘IT skills’ response from earlier. The conflation between Media Arts understandings and IT skills is apparent, although the technology soon becomes the focus.

The above discussion focussed on gaming and narrative conventions before Dave explained the technical processes used in Scratch more explicitly. He asked the class if they could explain how to insert an image into their projects. Dave chose three students to describe their processes. Each student provided a different method for inserting an image into a project. While they may have been taught various ways, given Dave’s predilection for student-centred learning, they likely learned these different techniques from each other or from tutorials online. The focus always remained on how to use the technology.

During a subsequent lesson, three students worked on their projects together. One group member, Camilla, took me through a project she was working on. She was clearly technically proficient and could discuss how she made the sprites (the animated image) of her project move. In The Key Hole project, she showed several keys on the screen and said, ‘Each key can do something. I’m just trying to get a good sound for when the key hits the keyhole.’ I asked her about the narrative of her game. ‘Well,’ she said, ‘I haven’t thought much about that. But I guess it could be that this mischievous key is trying to escape the keyhole.’ For Camilla, the technology was more important than the narrative conventions of the game. Although Camilla often recreated projects found in books and online, she applied these understandings more broadly in some instances. For example, when Camilla and I played The Key Hole together, she instructed me to use specific keys to move my sprite around the screen. When we played, I became confused. The A key on the keyboard's left made the sprite move right, and the D key on the right made the sprite move left. I mentioned how tricky this was to Camilla, who realised her mistake and said, ‘That should be easy to fix,’ before remedying the error. Camilla could identify and debug her code, demonstrating an understanding of how the technology worked. The technology here was an essential part of the project and was a part of how Camilla demonstrated technical proficiency.

Audrey, another group member, was often left with nothing to do while her two friends worked together, sharing and copying code. Audrey explained that her project featured a girl collecting balloons, who also needed to escape the ghoul chasing her. Once the protagonist caught all the balloons, she would progress to the next level, which involved a change of the background image. I asked if the next level would increase in difficulty, to which she replied, ‘Ah, maybe.’ We discussed what help her friends had provided her during the session, to which she said, ‘Getting it to work’. She had the idea for the game and some understanding of the types of things Scratch could achieve but did not know how to put into practice the ideas due to her limited technical skills. This hampered her ability to demonstrate her knowledge of other key concepts, as she could not move forward with the technology. Although the key concept of ‘technologies’ is broader than the skills and processes, students still need assistance with these aspects, especially when the technology is new to them or used in alternate ways.

This case study presents a nuanced understandings of what the concept of ‘technologies’ can look like in a classroom. There is a focus on the technical aspects of the concept of ‘technologies’ even though not all students could use the technology proficiently. Students were required to learn how to use the technology, with a student-centred approach the preferred model in the classroom. Despite this focus, it was clear that some students could not develop technical skills to progress their productions. The second case study in the following section examines a classroom that focuses on the technical aspects of ‘technologies’, but this is enacted differently in the classroom.

Case 2: technical proficiency for a polished production

The second case was conducted with a Year 6 class and their teacher, Josh. The case was a double class with approximately 50 students and two teachers. Josh taught the unit of work pertaining to this study, with the second teacher working in a supporting role. Josh was interested in graphic design and filmmaking with students but did not relate this to Media Arts. The unit of work featured as part of this case study was not explicitly taught as a Media Arts unit but was part of the English subject work the students were undertaking. This is not unusual, as English is a subject where media literacy education is often taught (Hobbs Citation2004). As the case study data collection progressed, however, it was possible to see that the concept of ‘technologies’ was apparent from a media literacy perspective in this unit of work. Students created a children’s picture book in the form of an eBook, including the text, illustrations, and preparation for distribution. To create the eBooks, the students used their own iPads as part of a Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) program. Most students had experience using iPads as part of their learning which, as Josh said, ‘takes away a lot of the barriers or organisation’ of the technology itself.

Josh said the students understand how to use the technology well. The students required specific software applications, including Sketchbook (Sketchbook Inc Citation2018) and Book Creator (Tools for Schools Citation2011). Josh says:

There’s very little teaching that needs to go into the use of iPads and the use of the apps. The teaching that needs to come in is more so the use of, it’s more the use of basic graphic design, how you design and things like that. Everything else they know.

In a subsequent lesson, there was more explicit teaching on how to use the technologies. Josh provided ten minutes for students to experiment with the drawing app used for their illustrations. The Sketchbook app provided scope for illustrating with a range of digital pens, backgrounds and layering. During the initial play, Josh demonstrated on his iPad connected to a projector how to change pens and layers, explaining he would draw on one layer and colour on another. After this, the experimentation became more structured, with Josh instructing students to draw a grid on a blank page and select a colour palette. Students then drew lines with the different pen types, with one line per box on the grid. They considered what pens might work well for their illustration style, with some suited for drawing and others for colouring and shading. Dylan, a student, said it was difficult to choose just one pen to stick with as a style as ‘ … there are lots of choices and to use one throughout the book, you might want to change it up.’

The students understood the need to apply their chosen style consistently across their eBooks. Students reported valuing some of the affordances of drawing using the iPad. Dylan said:

If you do it old school, you can’t really change it, but in this app you can … when you do it on the iPad, when you draw, you can rub it out easier and it doesn’t smudge everything … or you can go back.

On the iPad it’s a bit harder to draw … but you can actually zoom it in and make it really close up if you want something really close up. If you’re drawing [on paper] you can do that but it will take a lot of work, but on the iPad you can just go zoom in close … you can make it more delicate on the iPad.

Case 3: no access to digital technology for media production

The final case of this study was a class of Year 1 students and their teacher Angela. Angela was an early years teacher with minimal experience teaching Media Arts. She expressed concern that in previous years, students had engaged in more traditional literacy work, instead of engaging with Media Arts. Angela used a pre-existing unit of work where students created a soundscape to represent a landscape image. At the unit's start, Angela was unsure how she would record the soundscapes or what level of technology she would use. However, she recognised the importance of using technology for Media Arts, especially since this was the only Media Arts work the students would undertake all year. She said:

The problem was, and the problem is, and this whole thing got me thinking about this, that it’s all to do with accessing technology. You’ve got to have technology in there somewhere because that’s one of the four content descriptors.

At the beginning of the unit, Angela led the students through a series of activities about sounds in everyday life. In subsequent lessons, the students began to plan for their soundscape. In small groups, students chose from a series of images, such as a rainforest, waterfall and outer space. Angela explained how students would design their soundscapes using planning documents. The planning was broken into small steps: re-draw their selected image, list the characters that might be in the location and write the sounds they thought they would hear if they were in the location. Students would then practise creating the sounds that would go into their soundscape. To do this, students used found objects in the room. For instance, some students tapped their pencils, poured water from bottles or used their voices to make sounds. Although not digital, children are exploring different types of non-digital tools, or technologies, to assist in the creation of their eventual soundscape. The final part of the planning required students to list the objects they planned to use. In one group, a student discussed that a pencil tapping could be a lizard walking around and tapping some cups could make the sound of water falling on rocks. As they were not using digital technology at this stage, they could not record and playback the sounds, preventing them from understanding that a pencil tapping is unlikely to sound like a lizard walking.

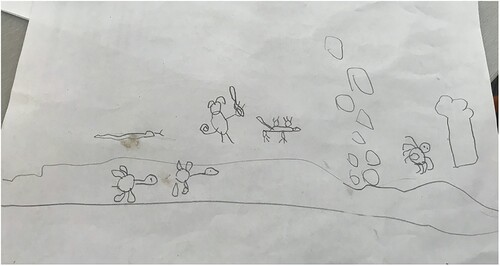

A couple of days later, the students returned to the task. In the group I observed, the students drew a timeline of their soundscape, using symbols and pictures to represent the length and intensity of each sound (see ).

Figure 1. Example of soundscape timeline.

shows that this group planned to use different animal sounds, including snakes and monkeys. It also shows how some sounds, such as the turtle, were repeated. The water is depicted as running throughout the soundscape. Towards the end of the soundscape, the sound of rocks falling was depicted as having intensity. There was some back and forth on the plan, helping the students understand and order their future digital text using pens and paper. While not yet using digital technology, they used other non-digital technologies to aid their understanding and preparation.

During the final lesson, the students had the opportunity to make their soundscapes. However, the soundscape was more of a performance than a media production. Each group had the image they were representing projected to the class. The group members stood in front of the class while the rest of the students watched as an audience. Angela explained that each group would record their soundscape to match the image. Each group had two turns at recording. Angela would record the soundscape on her computer. The students did not use the digital technology itself – Angela controlled the buttons and the recording process.

After the first group recorded, Angela reminded students of some things to consider. Each person in the group was responsible for one sound, and their soundscape should go for 30 seconds. A student requested access to their planning sheets and timelines, which students received just before their turn to record. The first group recorded again. They used water bottles, maths counters pinging off desks, and rustling leaves to create their sounds. Angela recorded the soundscape, motioned for them to continue through the entire 30 seconds and made a cutting motion when they had reached the correct length. She played the recording back to the class. After a mix-up, the students told Angela the soundscape reflected a waterfall, not the initial image of a different location on the screen.

Angela asked the class if they thought the soundscape sounded enough like a waterfall. They answered with a ‘no’ and offered suggestions on how to make the soundscape more authentic, including making ‘shh’ type sounds with their voices. As the group recorded a final time, Angela moved her computer to try and find the best place to record the sound. During the playback, they realised the soundscape was quieter than they thought it would be. Angela asked the groups to make their sounds louder.

It became clear to Angela that the students did not fully comprehend the task until they began to record. She said, ‘I think for some of them, the penny didn’t drop until we actually performed them, and they were like ahhh.’ The students were responsible for many parts of the production of their soundscape. However, as they did not practice digital recording, they could not understand how the non-digital and digital technology could inform each other.

Analysis and discussion

Across the three case study examples, the concept of ‘technologies’ was unevenly implemented across the classrooms. There are several insights that these case studies allow us to address. For this paper, I will examine two sub-themes to help understand how ‘technologies’ was approached in the case study classrooms. The first sub-theme, a tool rather than a key concept, examines how the technology was used not to develop a deep understanding of the concept of ‘technologies’ but rather as a way to use tools to achieve the desired outcome. The second sub-theme, non-digital tools, helps to understand how non-digital technologies can be used in Media Arts work. As I unpack this sub-theme, I also consider how using digital technologies would deepen understandings of the concept for the students involved.

A tool rather than a key concept

Cases 1 and 2 both focus on how to use digital technologies as part of production work. Although enacted differently by the teachers, the technology was an important tool to help achieve a goal – a Scratch game or children’s eBook. Josh from case study 2 used explicit instruction to ensure all students could use the affordances of the software effectively. Josh provided time for students to experiment with the Sketchbook app, playing with the types of pens available. He demonstrated the app's features, including how to use different layers for different purposes. The class used technology in every lesson observed quite seamlessly. While there were aspects of instruction, like the teaching of the Sketchbook app, the students drew on a wealth of experience and understanding about how to use the technology. The use of technology is one aspect of the concept of ‘technologies’, but students were not positioned to consider the concept beyond the ‘use’ of technology. There was no focus on how the technology enabled or constrained design choice – although students would have understood there were limitations to some individual choices.

Although students were developing an eBook, the focus for much of the unit was on children’s picture books. eBooks have a set of different affordances, including moving image and audio, both of which were accessible to students using the eBook Creator app. However, these innovative conventions, where some form of interaction was invited from the audience, were not explored in class. Differences between the technology of a print and digital book were not explored throughout the unit. Some students did add a short film segment to their eBook, but this was not the standard. Only three of the 39 eBooks collected invited some form of interaction from the audience. The technology was used to reproduce a form available physically, not to explore the concept of ‘technologies’. The concept could have been investigated further through an exploration of the interactive affordances of eBooks or how the technology has impacted on distribution methods.

Although facilitated differently, Dave from case study 1 also emphasised using technology as a tool. In the lessons observed, there was some teacher-directed exploration of the technology. However, the students usually explored as they looked for ways to move their projects forward individually or in small groups. As described, this student-centred approach caused difficulties for some students. Audrey had different technical skill levels, which impacted her project leaving her unable to advance her ideas. In subsequent lessons, she changed her ideas to meet her skill level. This more straightforward project required less critical exploration and impacted her ability to demonstrate an understanding of other key concepts, such as ‘languages’. To cope with the demands of the technology, some students copied code from each other, or had their more knowledgeable friends do the code for them. Furthering a focus on the interactivity of Scratch could have shifted the focus away from the program as a tool towards a deeper understanding of how choices are enabled or constrained by media creators.

The focus of case 2 was even more firmly on technology as a tool. While Josh’s students did not consider the technology beyond what it could help them produce, they all successfully completed the task. Dave’s students had varying levels of success in leveraging technology to produce a project. Although the students of both classes created a media artwork that used the technology, there was little explicit discussion beyond what the technology could do within the confines of their direct project. The teachers and students viewed technology as a tool without an explicit understanding of the impact that it had on the choices available.

Non-digital tools

Students can develop conceptual understandings without using digital technologies (Hobbs Citation1998; Bazalgette Citation1992). For Angela, the choice for her students to create a soundscape without using technology was practical to some extent. She did not have enough digital technology and was concerned about how to manage the sounds from different groups if the class recorded simultaneously. Despite Angela being the only person to use digital technology, there were times the concept of ‘technologies’ was explored.

Technology includes essential tools in creating media artworks (Bazalgette Citation1992). In Angela’s class, students used several non-digital tools. As they made their soundscape, students used items from the classroom and their bodies through voice or clicking, for example, to represent sounds from the scene. They had to consider each sound's length, volume, and placement within their 30-second recording. Students understood this process to some extent. One student, Ella, said, ‘We are working towards making a soundscape and I’m using sticks and leaves and stuff like that to make noises.’

The concept of ‘technologies’ became more explicit during the final lesson, where Angela recorded the soundscapes in front of the class. Students had the opportunity to hear their recorded soundscape played back to them and began understanding what the technology did to the sounds they created. They realised the soundscapes did not sound as intended and offered suggestions in response to this newly developed understanding. Digital technology was integral to cementing understandings of the concept of ‘technologies’, even though these were still limited to technical production. There were conversations about the microphone placement and how the sounds and the microphone interact. This inclusion of digital technology as part of the work, not separate, was essential to build these early conceptual understandings.

Although Angela’s recordings were relatively simple, she pressed record, and she pressed stop when the students were done, she still had to consider several aspects of how to use the technology, including what program to use, how to press record, how to playback and how to insert the sound into the class slideshow. It might not seem worth having children attempt these processes to an adult familiar with the technology. But for some children, this might be one of the few times that year they could have used digital technology. Although not the only function of the key concept of ‘technologies’, access to digital technology is still an essential part of media production (Cappello, Felini, and Hobbs Citation2011).

Conclusion

Media literacy education can cope with the demands of the shifting nature of technology. The history of media literacy education shows the field has always had to come to terms with how technology is used, by who, and for what purposes. Some may claim a broadening of the subject, or as some call it, Media Education 3.0 (Ptaszek Citation2020), is required. But the conceptual framework has always been designed with new and emerging media forms in mind. While, as Buckingham (Citation2019) contends, we should critically debate the concepts as we encounter new forms of media, the framework remains relevant. What is essential however is a more clearly defined understanding of what we mean when we discuss ‘technologies’ in relation to media literacy education and the intersection of this with the lived experiences of children and young people. While primary school teachers, to varying degrees, understand how to use some digital technologies, even highly competent and interested teachers are not always making the connection between aspects of technologies that lie outside of using technology as a tool. Research translation between media literacy researchers and teachers in the form of professional learning, publications written specifically for teachers and examples of classroom practice, would start to address this problem for primary school teachers. There can be a lag between technology innovations, research, and classroom translation due to the unsettled nature of media and communications knowledge (Dezuanni Citation2021), which is why teacher understanding of the concept of ‘technologies’ is essential.

If we think media literacy education encompasses the full suite of technologies of how we make the media, we need to continue thinking through how teachers can help students develop understandings of all that entails in the current media landscape, including how media literacy understands areas of technology that are usually more firmly placed outside the discipline. This includes artificial intelligence and algorithms as non-human participants in producing and distributing media artworks. Understanding how to use technologies for particular purposes is essential. Using technologies in various ways for various outcomes is also important. To cope with ‘technologies’ as a concept, though, we need to ensure the concept of ‘technologies’ is developed to encompass not just the application of technologies as tools for production, but rather as part of the broader media landscape that impacts our everyday media practices.

Ethics

This study was given approval by QUT’s Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number 1700000733) and the education jurisdictions where the research occurred. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants and children’s parent/guardian.

Acknowledgements

This study was undertaken on unceded Ngunnawal land and the unceded lands of the Turrbal and Yugara people, the First Nations owners.

I also acknowledge the students and teachers who shared their classrooms to me. Without them, this research would not have been possible. Thank you to Prof Michael Dezuanni and Prof Annette Woods who both provided feedback on this paper and to the reviewers for their input. Parts of this research were supported by the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for the Digital Child through project number CE200100022.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 In Australia, students in Year 1 are approximately 6–7 years of age. Students in Year 6 are approximately 11–12 years of age.

References

- Apps, Tiffani, Karley Beckman, and Sarah K. Howard. 2023. “Valuable Data? Using Walkthrough Methods to Understand the Impact of Digital Reading Platforms in Australian Primary Schools.” Learning, Media and Technology, 294–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2022.2160458.

- Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). 2018. “My School.” 2018. https://www.myschool.edu.au.

- Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). 2022. “The Arts | V9 Australian Curriculum.” 2022. https://v9.australiancurriculum.edu.au/teacher-resources/understand-this-learning-area/the-arts#media-arts.

- Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). n.d. “Learning in Media Arts.” Accessed June 7, 2019. https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/the-arts/media-arts/structure/.

- Australian Media Literacy Alliance. 2020. “Work.” https://medialiteracy.org.au/index.php/work/.

- Bazalgette, Cary. 1992. “Key Aspects of Media Education.” In Media Education: An Introduction, edited by Manual Alvarado, and Oliver Boud-Barrett, 199–219. London: BFI Pub.

- Bazalgette, Cary. 2010. “Analogue Sunset. The Educational Role of the British Film Institute, 1979–2007.” Comunicar 18 (35): 15–24. https://doi.org/10.3916/C35-2010-02-01.

- Braun, Virginia., and Victoria Clarke. 2022. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide to Understanding and Doing. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Buckingham, David. 2003. Media Education: Literacy, Learning and Contemporary Culture. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Buckingham, David. 2013. “Challenging Concepts: Learning in the Media Classroom.” In Current Perspectives in Media Education: Beyond the Manifesto, 24–40. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137300218

- Buckingham, David. 2019. The Media Education Manifesto. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Buckingham, David, and Andrew Burn. 2007. “Game Literacy in Theory and Practice.” Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia 16 (3): 323–349.

- Cappello, Gianna, Damiano Felini, and Renée Hobbs. 2011. “Reflections on Global Developments in Media Literacy Education: Bridging Theory and Practice.” Journal of Media Literacy Education 3 (2): 66–73. www.jmle.org.

- Dezuanni, Michael L. 2015. “The Building Blocks of Digital Media Literacy: Socio-Material Participation and the Production of Media Knowledge.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 47 (3): 416–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2014.966152.

- Dezuanni, Michael L. 2020. Peer Pedagogies on Digital Platforms: Learning with Minecraft Let’s Play Videos. Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Dezuanni, Michael L. 2021. “Re-Visiting the Australian Media Arts Curriculum for Digital Media Literacy Education.” The Australian Educational Researcher 48: 873–887. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-021-00472-6.

- du Gay, Paul, Stuart Hall, Linda Janes, Hugh Mackay, and Keith Negus. 1997. Doing Cultural Studies : The Story of the Sony Walkman. Doing Cultural Studies : The Story of the Sony Walkman. Culture, Media and Identities. London: Sage, in association with The Open University.

- Groot, Tjitske de, Mariëtte de Haan, and Maartje van Dijken. 2023. Learning In and About a Filtered Universe: Young People’s Awareness and Control of Algorithms in Social Media. Learning, Media and Technology. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2023.2253730

- Hobbs, Renée. 1998. “The Seven Great Debates in the Media Literacy Movement.” Journal of Communication 48 (1): 16–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1998.tb02734.x.

- Hobbs, Renée. 2004. “A Review of School-Based Initiatives in Media Literacy Education.” American Behavioral Scientist 48 (1): 42–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764204267250.

- Hoechsmann, Michael, and Stuart R. Poyntz. 2012. “What Is Media Literacy ?” In Media Literacies: A Critical Introduction, edited by Michael Hoechsmann, and Stuart R Poyntz, 1–16. Malden, M.A.: Blackwell Publishing.

- Jacques, J., J. Grosman, A. Collard, Y. Oh, A. Kim, and Hyeon-seon Jeong. 2020. “Pre-Service Teachers’ Performance in Solving Word Problems in Mathematics in the Colleges of Education in Ghana: Effect of Constructivist Approach.” Education Journal 3 (June): 37–62. https://doi.org/10.31058/j.edu.2020.31005.

- Jandrić, Petar, Jeremy Knox, Tina Besley, Thomas Ryberg, Juha Suoranta, and Sarah Hayes. 2018. “Postdigital Science and Education.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 50 (10): 893–899. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2018.1454000.

- Jenkins, Henry. 2006. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press.

- Jolls, Tessa, Barbara J. Walkosz, and Dee Morgenthaler. 2013. “Media Literacy Education in Action.” In Media Literacy Education in Action: Theoretical and Pedagogical Perspectives, 11–19. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203076125.

- Knaus, Thomas. 2020. “Technology Criticism and Data Literacy: The Case for an Augmented Understanding of Media Literacy.” Journal of Media Literacy Education 12 (3): 6–16. https://doi.org/10.23860/JMLE-2020-12-3-2.

- Marsh, Jackie, Elizabeth Wood, Liz Chesworth, Bobby Nisha, Beth Nutbrown, and Bryony Olney. 2019. “Makerspaces in Early Childhood Education: Principles of Pedagogy and Practice.” Mind, Culture, and Activity 26 (3): 221–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2019.1655651.

- Masterman, L. 1985. Teaching the Media. London: Comedia Publishing Group.

- McKenzie, Phillip, Paul Weldon, Glenn Rowley, Martin Murphy, and Julie McMillan. 2014. “Staff in Australia’s Schools 2013: Main Report on the Survey.” Australian Council for Educational Research. https://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1021&context=tll_misc

- Merriam, Sharan B, and Elizabeth J. Tisdell. 2015. “Designing Your Study and Selecting a Sample.” In Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation, 73–104. John Wiley & Sons. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/qut/detail.action?docID=2089475.

- MIT. 2013. “Scratch.” https://scratch.mit.edu/.

- Padlet. 2018. “Padlet.” 2018. https://padlet.com/.

- Parry, Becky, and Lucy Taylor. 2021. “Emergent Digital Authoring: Playful Tinkering with Mode, Media, and Technology.” Theory Into Practice 60), https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2020.1857127.

- Partington, Anthony, and David Buckingham. 2011. “Challenging Theories: Conceptual Learning in the Media Studies Classroom.” International Journal of Learning and Media 3 (4): 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1162/ijlm_a_00079.

- Poyntz, Stuart R. 2015. “Conceptual Futures: Thinking and the Role of Key Concepts Models in Media Literacy Education.” Media Education Research Journal 6 (2): 63–79.

- Poyntz, Stuart R., Divina Frau-Meigs, Michael Hoechsmann, Sirkku Kotilainen, and Manisha Pathak-Shelat. 2020. “Introduction.” In The Handbook of Media Education Research. Wiley Online Books. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119166900.ch0

- Ptaszek, Grzegorz. 2020. “Media Education 3.0? How Big Data, Algorithms, and AI Redefine Media Education.” In The Handbook of Media Education Research, edited by Divina Frau-Meigs, Sirkku Kotilainen, Manisha Pathak-Shelat, Michael Hoechsmann, and Stuart R. Poyntz, 229–240. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119166900

- Sefton-Green, Julian, and Luci Pangrazio. 2022. “The Death of the Educative Subject? The Limits of Criticality Under Datafication.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 54 (12): 2072–2081. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2021.1978072.

- Showbie. 2018. "Showbie”.

- Sketchbook Inc. 2018. Sketchbook®”.

- Stake, R. 1995. The Art of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Stoddard, Jeremy. 2014. “The Need for Media Education in Democratic Education.” Democracy & Education 22 (1): 1–9.

- Tools for Schools. 2011. “Book Creator.”.

- Valtonen, Teemu, Matti Tedre, KAti Mäkitalo, and Henriikka Vartiainen. 2019. “Media Literacy Education in the Age of Machine Learning.” Journal of Media Literacy Education 11 (2): 20–36. https://doi.org/10.23860/jmle-2019-11-2-2.

- Williamson, Ben. 2017. “Learning in the ‘Platform Society’: Disassembling an Educational Data Assemblage.” Research in Education 98 (1): 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034523717723389.