ABSTRACT

Time and its management, as evident in the scheduling, sequencing and structuring of activities, is important in early childhood education (ECE). While ECE apps have been changing teaching and learning practices for over a decade, research has yet to examine how they represent and manage time. To address this gap, we analysed the representation and management of time in iHuman ABC, a popular English learning app for children in China. Adopting Djonov and Van Leeuwen's (Citation2018) model for analysing semiotic software and Van Leeuwen’s (Citation2008) critical discourse studies framework, we examined temporal features in the app's design and references to these features in promotional materials and user reviews. Findings reveal that iHuman ABC reflects an instructivist ideology which considerably limits children’s ability to organise their time and contradicts research-based recommendations for teaching English. This study contributes to critical multimodal studies of the potential of software to transform educational practices.

Introduction

The centrality of apps in children’s lives today and their power to extend education beyond the classroom are widely acknowledged (Herodotou Citation2018). Yet few studies have examined the design of learning apps for children with a focus on its potential to transform the social practices of teaching and learning (Van Leeuwen and Iversen Citation2017). Time is a key dimension of all social practices (Van Leeuwen Citation2008) and therefore also of the teaching and learning practices supported by digital technologies. Many educational apps for preschoolers structure children’s interaction with the contents through time control features, which should be thoughtfully designed to help them stay focused on the learning objectives (Falloon Citation2013). Like other app features, time controls manifest multimodally, through different communication modes including verbal instructions and visual symbols (e.g., progress bars and countdown timers), and might not fully follow research-based recommendations for supporting young children’s learning (Callaghan and Reich Citation2018). Specifically, empirical research on learning apps for children is yet to examine whether they fulfil the promise of serving as ‘a space that extends beyond traditional, institutional learning with rigid, temporal schedules’ (see Schuck, Kearney, and Burden Citation2017, 10) and can help overcome the limitations of associated instructivist pedagogies. Thus, a critical multimodal perspective is needed to analyse how these educational apps represent and manage time.

While studies of educational apps have discussed time controls in general terms (see Gibson and Clarke-Midura Citation2015; Welbers et al. Citation2019), little is known about whether and how time management in learning apps can support learning in specific subject areas (e.g., teaching preschoolers English in China). As English learning materials occupy a substantial share among apps marketed as ‘educational’ in the Apple, Google Play, and Amazon app stores (Vaala, Ly, and Levine Citation2015), how these apps represent and manage time warrants further research. Here China presents an interesting case because many preschoolers are reported to be using English learning apps while parents are concerned about whether these apps could effectively engage children in learning in ways that allow parents to monitor children’s progress (Xia and Gao Citation2022).

This study examines how the multimodal design of an English learning app for young children that is popular in China seeks to control the time children spend on various activities and whether its way of time management reflects research findings on how children learn English. Specifically, we chose a popular English learning app developed in China for preschoolers, iHuman ABC, as our case study. We adopted a critical multimodal approach for the study of semiotic software (Djonov and Van Leeuwen Citation2018) and analysed the interface design, promotional materials about it, and user reviews to address the following research question: How is time represented and managed in an English learning app for preschoolers that is popular in China?

Time in the design and use of educational apps

Time has received only cursory attention in research on educational apps, mostly in relation to gamification. Gamification is an essential feature of many educational apps (Hirsh-Pasek et al. Citation2015) and refers to the incorporation of game elements like story-telling, visualisation of characters and problem-solving to add fun to non-game contexts like education (Kapp Citation2012). Language learning apps employ gamification to turn mundane drills into fun experiences and enhance learners’ motivation to learn the target language (Purgina, Mozgovoy, and Blake Citation2019).

Previous studies have identified that gamification features related to time operate at two levels – macro and micro. Macro-level features operate beyond a single learning task. For example, a set of tasks may be presented in a linear sequence, which imposes strong time constraints, or as a sandbox (or open-world) structure, to invite free exploration (Thompson, Berbank-Green, and Cusworth Citation2007). Micro-level features operate within a task. They include progress bars, which indicate how much of a task a learner has completed, and timers, which measure or constrain the duration of a user’s response time and replay options. Such gamification features warrant critical attention due to their implications for learners’ autonomy and motivation, as timers could increase language learners’ sense of challenge and thrill (Sun and Hsieh Citation2018).

A small number of empirical studies have related time management in educational apps to learners’ outcomes. Welbers et al. (Citation2019) found that introducing session time limits in a learning app (to prevent ‘binging’) led undergraduate students to move away from cramming and adopt a distributed learning style, which resulted in better learning performance. Gibson and Clarke-Midura (Citation2015) examined the virtual performance assessment of almost 4000 middle-school students in science through symbolic regression analysis and revealed that time stamps of learner activities and achievements in apps enabled learners to assess their progress and consider the relation between duration spent on certain activities and their scores. Experiments with children aged 4 to 8 years (Boteanu et al. Citation2016) and 3 to 5 (Troseth et al. Citation2020) showed that ‘real-time prompts’ (i.e., automated written or spoken suggestions for adults and children to discuss a topic) in e-books resulted in higher quantities of talk and turn-taking by adults and children, which could foster language learning. While such experimental studies offer valuable insights into the effectiveness of specific design features, they need to be complemented by qualitative research designed to ‘address more nuanced questions about the effective design of mobile applications for children’s learning’ (Booton, Hodgkiss, and Murphy Citation2021, 3).

Qualitative studies of learning materials have adopted a critical multimodal approach to examine their effectiveness with reference to recommendations for teaching in a specific discipline (e.g., history teaching in Zhang, Djonov, and Torr Citation2022), but are yet to examine time in apps designed to teach young children English. The critical multimodal study of iHuman presented in this article will address this gap with a focus on teaching alphabet knowledge and phonics. In that area, for teaching children English as a foreign language (EFL), researchers recommend starting with easier sound-to-letter correspondences before moving to harder ones (e.g., from phonemes present to those absent in children’s first language), and first introducing those that will enable children to decode and spell a greater number of words (Arnold and Rixon Citation2014). This study will build on previous research by analysing not only the app’s multimodal design, as a means of explicating how it enables or constrains users’ actions, but also discourses about it that might indicate how people legitimate its design and use, which observation alone cannot capture (Van Leeuwen Citation2018).

Preschool English education in China

Apps for teaching young children English offer a means of addressing the limited availability of and time constraints on preschool English classes in China. Since 2018, due to the Chinese government’s ban on English education in public kindergartens, only private kindergartens can offer English lessons. In private kindergartens only play-based English lessons are allowed, and kindergartens cannot teach content from the primary school curriculum (Liang, Li, and Chik Citation2020). These policies have thus increased the demand for English language teachers with qualifications and skills in early childhood pedagogy. Unable to meet these requirements, some private kindergartens have suspended English teaching (Yang Citation2018), while others have reduced the time allocated to it. For instance, private preschools reported limiting English lessons to 150 minutes per week (see Li Citation2022).

To manage time restrictions, teachers are likely to adopt instructivist approaches to teaching and adhere closely to schedules, leaving limited or no space for children's agency and interests (Tang and Maxwell Citation2007). Instructivism regards learning as a process where educators transmit knowledge in a predefined way, with an emphasis on the efficiency and effectiveness of the knowledge transfer (Porcaro Citation2011). Instructivist pedagogies would limit children’s autonomy over the timing of English learning activities and counter the government’s endorsement of learner-centred instruction and children’s active participation in their own learning (e.g., MOE Citation2012).

In the context of limited access to classroom-based English instruction, English learning apps for preschool-aged children have gained popularity in China (see Xia and Gao Citation2022). In a survey of Chinese parents of young children by Jiemian Edu (Citation2018), 63% of respondents selected interactive apps as the most popular way for children to learn English from scratch. It is therefore important to critically examine the potential of English learning apps to effectively support young children’s learning in this area.

As the use of learning apps in China constitutes a ‘shadow education’ practice, which is hard to observe directly (Liu and Bray Citation2022), researchers have sought to understand this practice by examining discourses about it. For example, a recent poststructural study of 13 policy papers in China (Li and Christophe Citation2024) found that they presented digital technology as both a remedy and a reason for problems in education, and positioned students, teachers and parents in similarly contradictory, often incoherent terms. For instance, parents were depicted as needing to be (re-)educated about effective (digital) learning and responsible for monitoring students and teachers. The present study complements research on digitalisation in education in general by focusing on time in the most popular English learning app for preschoolers in China, iHuman ABC, through a critical analysis of the app itself and discourses about its design and use.

A critical multimodal approach to analysing time in learning apps

This study adopts a critical multimodal discourse analysis (CMDA) approach and within it two analytical models: Djonov and Van Leeuwen (Citation2018)’s model for studying software and Van Leeuwen’s (Citation2008) model for analysing time as an element of social practice and how it is represented in discourse.

CMDA is an intersection of multimodal discourse analysis (MDA) and critical discourse analysis (CDA). While MDA examines the meaning potential of different semiotic resources and their co-deployment in texts and semiotic artefacts, CDA strives to inform efforts to achieve social justice by exposing how the use of semiotic resources (mainly language) reflects and naturalises certain social agendas and power relations (Djonov and Zhao Citation2014). CMDA aims to reveal how different semiotic resources work together to achieve communicative goals in various social practices.

Critical multimodal studies of software as semiotic technology

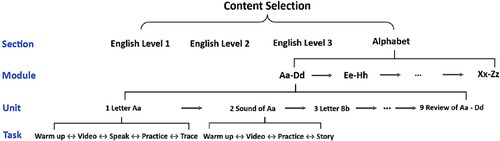

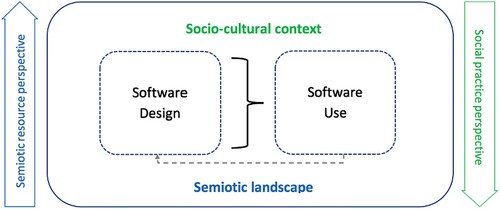

Djonov and Van Leeuwen (Citation2018) propose a social semiotic framework for critical multimodal studies of software. They conceptualise software as a semiotic artefact, ‘a type of semiotic resource that has material form and incorporates selections from other semiotic resources such as modes (layout, colour, mathematical symbolism), media (print, aural, video), and abstract meaning-making principles (e.g., genre, framing)’ (649). Studies adopting this model (see ) would examine:

the design of software tools (the semiotic resources they incorporate and the way these sources are represented);

their use in specific institutional and socio-historic contexts, and discourses about them; and

the broader semiotic landscape and socio-cultural contexts that shape the ways software design and use interact.

Figure 1. Framework for critical multimodal studies of software as semiotic technology (Adopted from Djonov, Tseng, and Lim Citation2021, 10).

We will employ this framework to analyse time features in a learning app’s design, promotional discourses about and user reviews of the app that relate to time and its management, and the potential of the app’s design to shape young children’s learning of English. We interpret the findings of this analysis with reference to the broader socio-cultural context of preschool English education in China (outlined in Section 3) and the semiotic landscape of learning apps’ design (see Section 2). We build on recent critical multimodal studies on semiotic software, about the rewards in Norwegian literacy apps (Kvåle Citation2021) and the potential of the social network site ResearchGate to transform the practice of academic peer review (Djonov and Van Leeuwen Citation2018). We extend this line of inquiry by examining how time is represented and managed by an English learning app.

Adopting this framework, we could analyse an app’s potential to transform a social practice such as the management of time in children’s app-based learning from two perspectives: (1) bottom-up – examining how the semiotic resources within the app represent and construct options for managing time; (2) top down – focusing on how the broader social practice of managing time in the teaching and learning of young children – is enabled and how its elements (participants, actions, location, etc.) and the relationships between them are potentially transformed through the app’s design.

Time in social practice

This study adopts Van Leeuwen’s model for analysing the relationship between discourse and social practice. In the model, time is a key element of all social practices, that is, ‘socially regulated ways of doing things’ (Van Leeuwen Citation2008, 6). Other elements include participants, actions, performance modes, locations, and resources (tools and materials), and the eligibility conditions each element must meet in a particular practice. Central to the model is the idea that when discourses represent social practices, they necessarily recontextualise, or transform, them through processes such as substitution, deletion, rearrangement or the addition of elements such as justification and evaluation, which can only be achieved in discourse. Similarly, Djonov and Van Leeuwen (Citation2018) argue that digital platforms designed for certain social practices have the power to transform these practices. For example, teachers play a significant role in managing the sequence of various learning activities in the classroom. iHuman claims to ‘arrange a scientific self-learning pathway for children’ (为孩子安排了科学的自学路径) in the app’s Help section, which could suggest that the app substitutes the teachers in managing the learning time and sequence.

Van Leeuwen’s (Citation2008) model also offers a framework for analysing how time and its management are represented in discourse, which could help unravel power relations and inequities in social practices. This framework offers four main distinctions for describing representations of time and its management:

Time Location (e.g., ‘at 10 am’) vs. Extent (duration or frequency, e.g., ‘for half an hour’, ‘every 30 minutes’);

Time summons, where a temporal order is embodied or imposed by authorities (e.g., app prompts such as ‘say a few more times’) vs. Synchronisation, when events are organised in relation to either other events (e.g., instructions like ‘after your play time, we’re going to do learning time together’) or natural/mechanical time (e.g., ‘get up when the sun rises or at 8am’);

Exact (e.g., ‘for 10 minutes’) vs. Inexact (e.g., ‘after a few days’);

Unique (e.g., ‘only this Monday’) vs. Recurring (e.g., ‘every Monday’), distinguishing a single from multiple instances of an activity.

This article extends Van Leeuwen’s (Citation2008) framework beyond its origin in verbal discourse analysis by adapting it to the critical multimodal analysis of an English learning app.

Methodology

Focal English learning app: iHuman ABC

This study is part of a larger doctoral project that examines how English learning apps position children and adults, and whether and how their design reflects research evidence of the ways young children learn English, and the potential of English learning apps to transform the social practices of teaching English to Chinese preschool-aged children. Apps in this larger project meet the following criteria: (1) designed to teach children aged 4 to 6 years English; (2) popular in China in terms of downloads in the iOS App Store during the first half year of 2022 (from January 1 to June 30, 2022, after the new Chinese regulation on English learning apps came into effect on December 13, 2021). We only focused on iOS App Store since parents tend to use iPad (iOS operated) for child education and there is no singular platform for Androids OS apps in China.

In this article, we focus on the popular English language learning app iHuman ABC (‘洪恩 ABC’, hereafter iHuman), which recorded more than 247,000 downloads in China from 1 January to 30 June 2022. iHuman is designed to teach English to children aged 0–5 years by a NYSE-listed company iHuman Inc. iHuman's help section describes the app as a self-managed tool for children who need to learn English.

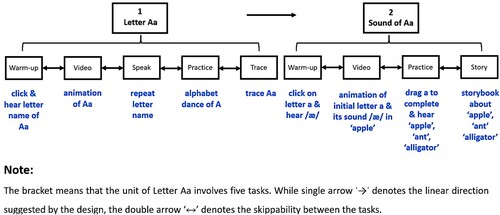

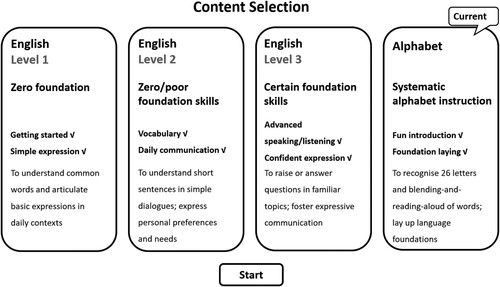

We categorised the content into a hierarchy of section, module, unit and task as shown in . The app offers four sections of contentFootnote1: ‘Idiomatic Colloquial English’ (地道口语) Level 1 to 3 and ‘Recognising Alphabet Letters’ (认识字母). For brevity, hereon we will label these sections simply ‘English’ and ‘Alphabet’. In the content selection page (represented in ), the app asks children to ‘let dad and mom choose the right level’ (让爸爸妈妈来选择合适的级别吧).

Figure 3. Four sections are shown on iHuman’s content selection screen, with descriptions of their content (translated by the first author).

The analysis we present below focuses on ‘Alphabet’ because it is a discrete section that presents a well-researched area of English literacy learning, namely, the alphabet and phonics (letter-sound correspondences). This makes it possible to evaluate the extent to which the app’s design reflects research recommendations for teaching in this area. The section teaches alphabet knowledge, including the names of the letters, their shapes and letter-sound correspondences, which are illustrated only with the relevant letter in word-initial position (e.g., for the letter ‘a’, only /æ/ for ‘apple’). The section consists of seven modules, each covering three to four letters. Each letter is presented in two units – ‘Letter’ and ‘Sound’. For the letter ‘Aa’, for example, the unit ‘Letter Aa’ (字母 Aa) teaches the letter name and shape through five tasks (‘Warm up 听’, ‘Video 看’, ‘Speak说’, ‘Practice 练’ and ‘Trace 写’) Footnote2, and another, ‘Sound of Aa’ (‘Aa的发音’) teaches the letter-sound correspondence by four tasks (‘Warm up 听’, ‘Video 看’, ‘Practice练’ and ‘Story 读’). Our close analysis of time features focuses on the two trial units of letter ‘Aa’, as they are freely accessible, whereas all other units require annual paid subscription.

Data collection and analysis

The data of this study comprise: (1) software design: the contents available to users of iHuman and how they are presented through the app’s interface, especially in the ‘Alphabet’; (2) discourses about the app and its suggested use: promotional materials (i.e., from in-app advertisements and the Help section) and iOS user reviews. While the promotional materials reveal the producers' claims about the app’s design and functions, the user reviews offer insights into users’ experiences with and perspectives on the app.

To collect the data, we used screenshots for static elements and video recording for dynamic elements (e.g., animation or possible navigation paths) of the app. Our analysis of iHuman’s design, presented in Section 6.1., drew on Kress and Van Leeuwen’s framework (Citation2021) for analysing the app’s visual design and on Van Leeuwen’s (Citation2008) timing categories to analyse features that represent or help manage time in the two units of letter Aa.

Given the status of young children’s use of learning apps in China as a shadow education practice, we examined the app’s use indirectly, by analysing discourses around and conducting walkthroughs of the app. To record such discourses for the larger research project, we captured 40 screenshots of in-app promotional materials and collected 672 user reviews in iOS App Store for mainland China from Jan 2018Footnote3 to Jun 2022 by Sensor Tower (an app store data analytic service provider). For this study, we identified 3 screenshots (i.e., Help section, parental settings and parental report) and 85 user reviews that mentioned time or time management, and drew on Van Leeuwen (Citation2008) to analyse these discursive constructions of time as an element of the social practice of using the app. We supplemented the analysis of these materials through ‘user walkthrough’ (Light, Burgess, and Duguay Citation2018), namely, exploring the app ourselves and trying out the options it offers for managing time. Specifically, we noted down the social actors (i.e., ‘who is involved in time management’) and actions they can perform to manage time when using iHuman. We then considered whether and how these affordances of iHuman seek to transform the practice of English language teaching, noting, for instance, that it is not teachers but the app’s designers and parents who control how much time children spend on various activities and in what sequence they complete them within the app. This analysis is presented in Section 6.2 and .

Findings

Representation and management of time in the app’s design

In this section, we will first present key findings from our analysis of the app’s design and promotional materials.

A linear learning path

Layout is a semiotic resource for visually arranging blocks of words, images and other graphical elements in multimodal artefacts and suggesting the order in which audiences should engage with these elements (Kress and Van Leeuwen Citation2021). We argue that the sequencing of the units suggested by iHuman’s linear layout represents the learning path, i.e., a route that users can take to accomplish a learning goal.

The main page of iHuman’s ‘Alphabet’ section adopts a linear layout (see ). The section's units are depicted as bubbles from letter A to Z and the learner needs to swipe left or right to navigate the path, with each bubble marked by an Arabic number from 1 to 60. This represents the tightly structured and predefined learning path used in this section of the app. This visual representation reflects the fact that learners have no choice over which letter to learn first; they must successfully complete one lesson before they can access the next. Children may have some discretion over their learning pace only if their parents have enabled the option of skipping forward or backward within the quarter or quintet of tasks in a unit. In addition, if the child is skipping all tasks, the app will issue a prompt to choose either to complete the unit again or return to the main page.

Addressing parents, the Help section brands this linear path as a ‘scientific self-learning path’ (科学的自学路径) and states that ‘(Children) can just follow the instruction and sequence to unlock (the following units)’ (‘根据指引按顺序解锁即可’) but does not explain what makes it ‘scientific’ nor ‘self-learning’.

Dominance of time summons over synchronisation features

The key findings of the analysis of time management in the two Letter A units are presented in . Of the 30 time features we identified in these units, 25 (86%) represented ‘time summons’. The remaining 5 (14%) were ‘synchronisation’ features, represented as progress bars that synchronise with video playing. These remaining features from the timing network (location/extent; exact/inexact; and unique/recurring) were embedded within time summons or synchronisation features. This is illustrated with selected time summons features in .

Table 1. Features of time representation & management.

Table 2. Micro time summons and their multimodal representation in iHuman ABC.

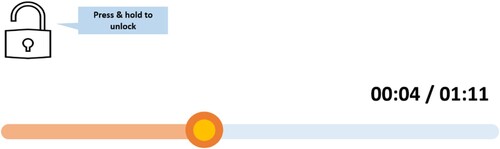

iHuman ABC employs three types of micro-level time summons, ones that operate within tasks, which are illustrated in . The most common type is prompts, which not only demonstrate how to complete a task but keep flashing until the learner completes it. The second type, time limits appear whenever the app asks children to pronounce a sound or word and impose a limit of eight seconds. The limit does not vary across different tasks regardless of how many times the learner is asked to pronounce the name of the letter ‘a’ /eɪ/. The third type is countdowns. When the user has finished the last task in a unit, a three-second countdown would appear together with a button the child can press to ‘continue learning’ (继续学习). If the child does not click on that button or the ‘home’ button to return to the app’s initial screen within three seconds, they are transferred directly to the next unit in the sequence. All three types of micro time summons impose standardised time limits to all the app’s users, which ignores individual variations in children’s response times and proficiency levels. The app and its promotional materials do not reveal how these time limits were determined (e.g., pre-launch trials or other empirical research).

iHuman ABC also employs macro-level time summons, which affects all tasks. These are in the form of a forced rest away from the app and screentime (see ). After a set period of using the app (20 minutes at default), a message appears asking children to rest their eyes. Meanwhile, English songs are played for 3 minutes, and a digital countdown clock is displayed. These songs are randomly selected from those available in the section, and may or may not provide a review of what children have just learned. In the ‘Alphabet’, for example, there are the so called iHuman New Alphabet Songs (‘洪恩新派字母歌’), such as ‘A, A. This is the letter A. /æ/, /æ/, apple. Apple, Apple.’ During the forced rest after children have completed tasks about the letters A, B and C, for example, the songs may be about these letters or letters they have not yet learned.

Figure 5. Forced rest page (left) & the parental setting (right) of forced rest in iHuman (translated by the authors).

Additionally, skipping the forced rest is only possible after verification by a parent. The app settings include a ‘mode of eye protection’ option where parents can change the interval between rests (from 10 to 60 minutes). In fact, iOS user reviews applaud this feature for not only protecting children’s eyes but also restricting digital play time (Excerpt: ‘the app is also very customisable to control the children’s time on learning and playing so that there’s no need to worry about visual impairment due to excessive screen time’, ‘软件也很人性化,还能控制孩子学习玩的时间,不会担心看手机太长时间伤眼睛了’).

Synchronisation is found only at micro-level, i.e., affecting a single task, in the form of progress bars (see ) in the Video tasks. In each video task, the progress bars are hidden by default and a prompt appears showing a key-lock and reading ‘child lock is on; tap to show the icon’ (‘儿童锁已开启;点击屏幕可唤出解锁’). They only show up when the adult follows the Chinese written instruction (press & hold to show, 长按解锁). This grants parents control in deciding whether to make the progress bar visible. The progress bar not only shows the video’s duration and how much of it has been viewed but allows children to skip forward or backward.

To sum up, iHuman features a linear learning path and time summons, at both micro and macro level, that control children’s use of the app. These time summons could take the form of prompts for actions, time limits, countdown to continue in tasks, and forced rest at intervals. Children can only vary their learning pace by skipping forward/backward among tasks or in video watching if adults have allowed that by changing the default settings. With tight control over the content, order, pace and duration of the learning activities, the app tends to adopt an educator-centred approach to English teaching. This positions children as passive learners, expected to comply with instructions and constraints imposed by adults, be they the app’s designers or parents.

Time management as a social practice by iHuman

This section draws on iHuman’s promotional materials and reviews to examine the app’s potential to transform time management in children’s English learning. Specifically, we will compare the scheduling in the suggested app use with the scheduling in traditional preschool English classrooms. Our analysis is built on the premise that timing itself as a social practice is transformed when it is digitally recontextualised, and that such transformations could involve substitution, deletions, rearrangements and additions of elements of the social practice in discourse (Van Leeuwen Citation2008). The results are summarised in .

Table 3. Scheduling (English) learning in iHuman.

Parents’ involvement

While teachers are the ones who schedule learning activities in traditional classrooms, parents are designated to substitute teachers in scheduling children’s learning with iHuman. Specifically, the app’s settings grant parents different degrees of control over children’s use of the app.

iHuman, as our analysis of the app’s design revealed, offers parents options for choosing whether children could skip forward/backward among tasks in a unit and at what intervals they should have a rest from the screen. Parents can also receive reports about children’s progress, such as the one shown in , about time spent on Module A-D, the number of times a child has spoken within a module in total, broken down into repeating letter names and reading after the picture books. In fact, user reviews requested some of these features (e.g., ‘it would be better if it could notify us of the learning progress on WeChat’ (要是能微信通知学习进度分析啥的就更好了) and ‘When time is up, it will play the learned English rhymes during the forced break, so as not to hurt their eyes’ (到时间了会强制休息播放学过的英语儿歌,不会伤眼睛)).

Moreover, the reviews reveal that parents have power over children’s access to the app and schedule children’s beyond-task actions (e.g., when and how long). For example, six comments mentioned that children would ‘be clamouring for’ (吵着) access to the app every day, indicating that parents served a gate-keeping function and had the final say on when and for how long children could access it.

Children’s role in scheduling

Despite designating adults as gatekeepers and time managers, iHuman does offer some possibilities for children to organise their time when using the app. For example, provided parents have enabled skipping, children could vary their own pace by moving for-/backward between tasks in a unit. Meanwhile, progress indicators such as timers and progress bars allow children to monitor their own learning pace. Notably, an iOS review praises the app as one that could help the child keep learning in general (Excerpt 2: ‘(I am) particularly fond of apps like iHuman ABC that enable children to control the learning progress.’‘特别喜欢洪恩这种能自己掌握学习进度的软件’). However, as our analysis of the app’s design reveals, children’s autonomy to schedule their actions (e.g., pause, skip and monitor their progress) is offered only within tasks or units, which is managed by options in the parental settings.

Discussion

By analysing the representation and management of time in the design of iHuman ABC and related discourses, we found that the app mainly positions children as subjected to time management decisions by the app’s designers and by parents. Approaching the app as a semiotic resource, we found that at the macro-level, it imposed sequences in which modules and tasks should be completed, and applied forced rests away from the screen at set intervals and for set durations, which only adults could modify. At the micro-level, learning tasks incorporated time summons such as prompts, time limits and countdowns. Offering further insight into the social practice of teaching children English with the app, our analysis of the app’s promotional materials and user reviews revealed positive evaluation of these time management features, in favour of the power the app grants parents to substitute teachers in controling the timing of children’s learning activities and determining the degree of agency children could have to vary their pace and monitor their own learning progress in iHuman.

iHuman’s approach to time management is consistent with the educational philosophy of instructivism. Proponents of instructivism believe that the teaching process and content should be carefully designed. iHuman’s claim of its ‘scientifically designed learning route’ matches this belief. This also echoes Henderson’s (Citation1996) finding that a predefined linear learning path is a typical feature of an instructivist design in educational technology. The time management mechanisms in iHuman like prompts, timers, and countdown to continue and parents’ time supervision serve to urge children to take actions with predefined duration and frequency. While structured time controls highlight efficiency, they downplay individual and local variation in learning, as do other standardised time controls in education (Adam Citation1995). Furthermore, they reflect a ‘non-idleness’ style of pedagogy with a strong belief that time wasting is forbidden (Foucault Citation1995). While the pedagogical goal in iHuman is no longer to get children accustomed to mechanical operations, as in the schools mentioned by Foucault, the ‘non-idleness’ style fits the efficiency-oriented marketisation of education in China (Crabb Citation2010) and goes against efforts to promote children’s agency and play-based learning in ECE.

Rather than contemporary philosophy and research recommendations for ECE practices, the design choices in iHuman seem to be motivated by its target consumers and China's education policies. The limited freedom that iHuman’s instructivism affords children might satisfy many Chinese parents’ anxiety about children’s limited time management skills and desire to closely monitor children’s learning activities (Xia and Gao Citation2022). The focus on effectiveness and efficiency in instructivist pedagogies might also cater to parents’ expectations for children to make the best of their time as a response to the increased educational competition in China (see Crabb Citation2010), where many for-profit education providers are still repeating the ‘winning at the first line’ mantra (Peng Citation2023). Additionally, iHuman's affordances align with recent education policies that charge parents with responsibility for monitoring children’s digital learning (a role traditionally performed by teachers), while calling for creative learner-centred approaches to teaching, a dynamic explored by Li and Christophe (Citation2024).

iHuman's instructivist approach to time management has several drawbacks for learners. Firstly, the linear and predefined learning route renders iHuman a ‘closed app’, with content that cannot be changed nor extended by learners (Flewitt, Messer, and Kucirkova Citation2015). While closed apps might sometimes be effectively used to teach phonics and vocabulary, they risk positioning learners as mere recipients of narrowly defined literacy knowledge. Secondly, the significant time constraints iHuman imposes on children deny them autonomy and opportunities to manage their own learning time. This approach plays down ‘individual and local differences, special circumstances and personal preferences’ (Adam Citation1995, 62). Thirdly, iHuman perpetuates the highly structured schedules and lack of opportunities for children-led activities in traditional preschool English classes, failing to meet the expectation that English learning apps could help children transcend the schedules set by schools (Schuck, Kearney, and Burden Citation2017).

The design of time management in iHuman does not align with research recommendations for teaching letter-sound correspondences to children learning EFL. For example, young Chinese-speaking children may find some English phonemes challenging because these phonemes (e.g., /v/, /z/) do not occur in Mandarin (Lin and Johnson Citation2010). They are therefore also more likely than English-speaking learners to mispronounce /v/ as /b/ or produce similar ‘negative transfers’ (Barone and Xu Citation2008). These are just some reasons why research has recommended planned (sequenced and regular) phonics instruction from preschool to primary school level (Linan-Thompson and Vaughn Citation2007). For instance, the sequence in which letters are introduced in phonics instruction should be ‘based on systematic principles such as notions of difficulty or of the potential for certain combinations of letters to create the maximum number of real words’ (Arnold and Rixon Citation2014, 28). iHuman’s design clearly does not follow such recommendations: the sequential linear path of the ‘Alphabet’ (reflected in its layout) simply follows the alphabetic order from A to Z and for each letter, only one corresponding phoneme is taught – for the letter in word-initial position (e.g., for the letter A, only /æ/ as in apple). The app thus is inadequate for teaching phonics, as it covers only 23 out of 43 to 44 phonemes in English, which is a common limitation in English teaching materials for young learners (Rixon, Citation2011).

To sum up, iHuman’s instructivist orientation to time management highlights efficiency and might appeal to parents’ expectations but does not align with contemporary philosophy and research recommendations for ECE practices.

Implications

We argue that educators and parents should be aware of the functions and implications of a particular design and combine approaches that best suit the characteristics of their target learners and learning area. Contrary to the instructivist conceptualization of learning as a knowledge transmission process, constructivism holds that learners should actively construct their knowledge system by exploring and experimenting with ideas, with scaffoldings from educators (Li and Chen Citation2023). The two approaches are not irreconcilable. Rather, combining them could allow app designers to encourage learners to engage with complex learning phenomena from different perspectives, accounting for multiple social and cultural realities and incorporating tasks fitted for various learning goals (Henderson Citation1996). Combining them would also resonate with the recommended transition from modelling to scaffolding and then self-directed learning, also known as the ‘to-with-by’ approach, in literacy education (Shin and Crandall Citation2018). Specifically, the instructivist approach (explicit teaching to learners) is suitable for introducing new content that does not rely on learners’ prior knowledge (e.g., letter-sound correspondences of ‘Cc’), while constructivist approaches (guided teaching with learners and self-learning by learners) are more useful for creative and context-dependent problems (e.g., teachers prepare content area texts that are contextually relevant to the children and help them utilize background knowledge for comprehension, see Shin (Citation2017)).

Conclusion

As English learning apps for preschoolers have gained widespread popularity in China, more research should investigate their potential to recontextualise the social practice of English teaching. This study examined this recontextualisation with a focus on time management using iHuman ABC as a case study and adopting a critical multimodal perspective. Our analysis of iHuman ABC revealed that the app promotes an instructivist approach towards time management, which might constrain children’s ability to use and organise their learning time. We argued that while such time management may suit parental expectations and other aspects of the preschool English education contexts, it does not align with research-based recommendations for teaching young children English and provides only limited opportunities for children to manage their time.

This study illustrated the value of Djonov and Van Leeuwen’s (Citation2018) approach for understanding the potential of software to transform teaching and learning practices. Detailed analysis of the design of a learning app enabled us to evaluate it in relation to research-based recommendations for teaching and learning in a particular learning area. Such a critical examination could contribute to the design, assessment, improvement and use of a learning app based on research evidence. This study also contributed to critical studies about software by incorporating the data from iOS reviews, a type of discourse that represents the design of the app and its potential or actual use. Although iOS comments, in contrast to observations of user interactions, provide only limited insight into an app’s actual use, they can reveal stakeholders’ perspectives about the app and legitimation of how they use its various features. Reviews can also offer insight into the views and experiences of users in different locations and across time, which would be difficult, or even impossible, to capture through observation.

While we elaborated on the representation of the management of time in an educational app, more empirical studies are needed to explore its implication from the perspective of other stakeholders, including preschool English teachers and preschoolers. For example, future studies may focus on questions like teachers’ stance on the temporal features of the app design and use, teachers’ legitimations for their evaluations and the implications of such design/use on young learners’ autonomy, motivation and learning results.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We term it as a section, instead of the level (‘级别’) or stage (‘阶段’) that may suggest an imposed order, because users can randomly choose any one of them anytime.

2 iHuman provides English translations of the modules, three of which are not literal translations: 听 is ‘to hear’, 看 is ‘to watch’ and 读 is ‘to read’. The Chinese words highlight expected actions in a task, while their English translations are about the purpose (e.g., hearing the sound to warm up) or medium (e.g., video to watch and story to read) of a task.

3 iHuman received its first comment in iOS App Store in Jan 2018.

References

- Adam, Barbara. 1995. Timewatch: The Social Analysis of Time. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Arnold, Wendy, and Shelagh Rixon. 2014. “Making the Moves from Decoding to Extensive Reading with Young Learners: Insights from Research and Practice around the World.” In International Perspectives on Teaching English to Young Learners, edited by Sarah Rich, 23–44. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Barone, Diane M, and Shelley Hong Xu. 2008. Literacy Instruction for English Language Learners Pre-K-2. New York: Guilford Publications.

- Booton, Sophie A., Alex Hodgkiss, and Victoria A. Murphy. 2021. “The Impact of Mobile Application Features on Children’s Language and Literacy Learning: A Systematic Review.” Computer Assisted Language Learning 36 (3): 1–30.

- Boteanu, Adrian, Sonia Chernova, David Nunez, and Cynthia Breazeal. 2016. “Fostering Parent–Child Dialog Through Automated Discussion Suggestions.” User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction 26 (5): 393–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11257-016-9176-8.

- Callaghan, Melissa N., and Stephanie M. Reich. 2018. “Are Educational Preschool Apps Designed to Teach? An Analysis of the App Market.” Learning, Media and Technology 43 (3): 280–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2018.1498355.

- Crabb, Mary W. 2010. “Governing the Middle-Class Family in Urban China: Educational Reform and Questions of Choice.” Economy and Society 39 (3): 385–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2010.486216.

- Djonov, Emilia, Chiao-I Tseng, and Victor Fei Lim. 2021. “Children’s Experiences with a Transmedia Narrative: Insights for Promoting Critical Multimodal Literacy in the Digital Age.” Discourse, Context & Media. 43: 100493–100504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2021.100493.

- Djonov, Emilia, and Theo Van Leeuwen. 2018. “Social Media as Semiotic Technology and Social Practice: The Case of Research Gate’s Design and Its Potential to Transform Social Practice.” Social Semiotics 28 (5): 641–664. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2018.1504715.

- Djonov, Emilia, and Sumin Zhao. 2014. “From Multimodal to Critical Multimodal Studies through Popular Discourse.” In In Critical multimodal studies of popular discourse, edited by Emilia Djonov, and Sumin Zhao, 1–14. New York: Routledge.

- Edu, Jiemian. 2018. “A Survey Report on User Behavior in the English Enlightment Market of China.” In. Shanghai.

- Falloon, Garry. 2013. “Young Students Using IPads: App Design and Content Influences on Their Learning Pathways.” Computers & Education 68:505–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.06.006.

- Flewitt, Rosie, David Messer, and Natalia Kucirkova. 2015. “New Directions for Early Literacy in a Digital Age: The IPad.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 15 (3): 289–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798414533560.

- Foucault, Michel. 1995. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, translated by Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage.

- Gibson, David, and Jody Clarke-Midura. 2015. “Some Psychometric and Design Implications of Game-Based Learning Analytics.” In E-Learning Systems, Environments and Approaches: Theory and Implementation, edited by Pedro Isaías, J. Michael Spector, Dirk Ifenthaler, and Demetrios G. Sampson, 247–261. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Henderson, Lyn. 1996. “Instructional Design of Interactive Multimedia: A Cultural Critique.” Educational Technology Research and Development 44 (4): 85–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02299823.

- Herodotou, C. 2018. “Young Children and Tablets: A Systematic Review of Effects on Learning and Development.” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 34 (1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12220.

- Hirsh-Pasek, Kathy, Jennifer M. Zosh, Roberta Michnick Golinkoff, James H. Gray, Michael B. Robb, and Jordy Kaufman. 2015. “Putting Education in “Educational” Apps: Lessons from the Science of Learning.” Psychological Science in the Public Interest 16 (1): 3–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100615569721.

- Kapp, Karl M. 2012. The Gamification of Learning and Instruction: Game-Based Methods and Strategies for Training and Education. San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

- Kress, Gunther, and Theo Van Leeuwen. 2021. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. 3rd ed. London, New York: Routledge.

- Kvåle, Gunhild. 2021. “Stars, Scores, and Cheers: A Social Semiotic Critique of “Fun” Learning in Commercial Educational Software for Children.” In Multimodal Literacies Across Digital Learning Contexts, edited by Maria Grazia Sindoni, and Ilaria Moschini, 57–71. New York: Routledge.

- Li, Xuan. 2022. “Preschool English Language Provision in China Under the Government Ban.” Cogent Education 9 (1): 2152257. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2022.2152257.

- Li, Hui, and Jennifer J Chen. 2023. The Glocalization of Early Childhood Curriculum, The Glocalization of Early Childhood Curriculum: Global Childhoods, Local Curricula. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Li, Kaiyi, and Barbara Christophe. 2024. “Oscillating Between the Techniques of Discipline and Self: How Chinese Policy Papers on the Digitalization of Education Subjectivize Educators and the Educated.” Learning, Media and Technology, 1–13. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17439884.2024.2306552.

- Liang, Luyao, Hui Li, and Alice Chik. 2020. “Two Countries, One Policy: A Comparative Synthesis of Early Childhood English Language Education in China and Australia.” Children and Youth Services Review 118:105386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105386.

- Light, Ben, Jean Burgess, and Stefanie Duguay. 2018. “The Walkthrough Method: An Approach to the Study of Apps.” New Media & Society 20 (3): 881–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816675438.

- Lin, Lu-Chun, and Cynthia J. Johnson. 2010. “Phonological Patterns in Mandarin–English Bilingual Children.” Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics 24 (4-5): 369–386. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699200903532482.

- Linan-Thompson, Sylvia, and Sharon Vaughn. 2007. Based Methods of Reading Instruction for English Language Learners: Grades K-4. Alexandria: Ascd.

- Liu, Junyan, and Mark Bray. 2022. “Responsibilised Parents and Shadow Education: Managing the Precarious Environment in China.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 43 (6): 878–897. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2022.2072810.

- MOE. 2012. The Developmental Guide for Children Aged 3-6”.

- Peng, Yuanyuan 2023. Early Education Helps Children ‘Win at the Starting Line'? (Zaojiao nengrang haizi ‘yingzai qipaoxian shang ma’).” In Nanning Evening News (Nanning Wanbao). Nanning: Nanning Daily. http://www.gxnews.com.cn/staticpages/20230315/newgx6411a906-21096221.shtml.

- Porcaro, David. 2011. “Applying Constructivism in Instructivist Learning Cultures.” Multicultural Education & Technology Journal 5 (1): 39–54. https://doi.org/10.1108/17504971111121919.

- Purgina, Marina, Maxim Mozgovoy, and John Blake. 2019. “WordBricks: Mobile Technology and Visual Grammar Formalism for Gamification of Natural Language Grammar Acquisition.” Journal of Educational Computing Research 58 (1): 126–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633119833010.

- Rixon, S. 2011. Beyond ABC: Investigating Current Rationales and Systems for the Teaching of Early Reading to Young Learners of English (PhD thesis). Centre for Applied Linguistics, University of Warwick. https://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/id/eprint/49792/~.

- Schuck, Sandy, Matthew Kearney, and Kevin Burden. 2017. “Exploring Mobile Learning in the Third Space.” Technology, Pedagogy and Education 26 (2): 121–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2016.1230555.

- Shin, Joan Kang. 2017. Literacy Instruction for Young EFL Learners: A Balanced Approach. Boston, MA: National Geographic Learning.

- Shin, Joan Kang, and JoAnn Jodi Crandall. 2018. “Teaching Reading and Writing to Young Learners.” In The Routledge Handbook of Teaching English to Young Learners, edited by Sue Garton, and Fiona Copland, 188–202. London: Routledge.

- Sun, Jerry Chih-Yuan, and Pei-Hsun Hsieh. 2018. “Application of a Gamified Interactive Response System to Enhance the Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation, Student Engagement, and Attention of English Learners.” Journal of Educational Technology & Society 21 (3): 104–116.

- Tang, Fengling, and Shirley Maxwell. 2007. “Being Taught to Learn Together: An Ethnographic Study of the Curriculum in Two Chinese Kindergartens.” Early Years 27 (2): 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575140701425282.

- Thompson, Jim, Barnaby Berbank-Green, and Nic Cusworth. 2007. Game Design: Principles, Practice, and Techniques – The Ultimate Guide for the Aspiring Game Designer. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

- Troseth, Georgene L., Gabrielle A. Strouse, Israel Flores, Zachary D. Stuckelman, and Colleen Russo Johnson. 2020. “An Enhanced eBook Facilitates Parent–Child Talk During Shared Reading by Families of Low Socioeconomic Status.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 50:45–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2019.02.009.

- Vaala, Sarah, Anna Ly, and Michael H Levine. 2015. “Getting a Read on the App Stores: A Market Scan and Analysis of Children's Literacy Apps.” Paper presented at the Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop.

- Van Leeuwen, Theo. 2008. Discourse and Practice: New Tools for Critical Discourse Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Van Leeuwen, Theo. 2018. “Moral Evaluation in Critical Discourse Analysis.” Critical Discourse Studies 15 (2): 140–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2018.1427120.

- Van Leeuwen, Theo, and Ditte Lund Iversen. 2017. “Semiotiska teknologier och lärande -M exemplet Mathletics [Semiotic technologies and learning - The example of Mathletics].” In Didaktik i omvandlingens tid: Text, Representation, Design [Didactics in the age of transformation: Text, Representation, Design], edited by Eva Insulander, Susanne Kjällander, Fredrik Lindstrand, and Anna Åkerfeldt, 52–66. Stockholm: Liber.

- Welbers, Kasper, Elly A. Konijn, Christian Burgers, Anna Bij de Vaate, Allison Eden, and Britta C. Brugman. 2019. “Gamification as a Tool for Engaging Student Learning: A Field Experiment with a Gamified App.” E-learning and Digital Media 16 (2): 92–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042753018818342.

- Xia, Jiapei, and Xuesong Gao. 2022. “Parental Involvement in Chinese Preschool Children’s Mobile-Assisted Foreign Language Learning.” Porta Linguarum Revista Interuniversitaria de Didáctica de las Lenguas Extranjeras, Special Issue: 65–81.

- Yang, Yi. 2018. Kindergartens Can’t Teach English? Expert: Misunderstanding. Game-Based Teaching Is Not Prohibited. (You'er yuan buneng jiao yingyu? Zhuanjia: Zheshi wudu youxishi jiaoxue buzai jinzhi zhi lie) Nanjing Daily (Nanjing Ribao). http://www.ourjiangsu.com/a/20181207/1544151276456.shtml.

- Zhang, Kunkun, Emilia Djonov, and Jane Torr. 2022. “Evaluating a Children’s Television Show as a Vehicle for Learning About Historical Artefacts: The Value of Multimodal Discourse Analysis.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 43 (6): 866–885. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2021.1913995.