ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the impact of the targeting of key players by law enforcement on the structure, communication strategies, and activities of a drug trafficking network. Data are extracted from judicial court documents. The unique nature of the investigation – which saw a key player being arrested mid-investigation but police monitoring continuing for another year – allows to compare the network before and after targeting. This paper combines a quantitative element where network statistics and exponential random graph models are used to describe and explain structural changes over time, and a qualitative element where the content of wiretapped conversations is analysed. After law enforcement targeting, network members favoured security over efficiency, although criminal collaboration continued after the arrest of the key player. This paper contributes to the growing literature on the efficiency-security trade-off in criminal networks, and discusses policy implications for repressive policies in illegal drug markets.

Introduction

More than ten years after Morselli and Petit’s article on law enforcement disruption of a drug importation networkFootnote1, our understanding of network recovery and adaptation after law enforcement targeting is still based on a limited number of empirical studies, and even fewer focusing on drug trafficking networksFootnote2. Simulation studies have attempted to fill this gap by comparing different targeting strategies, and considering various ways in which network members may adapt to new conditions and continue their illicit activitiesFootnote3. There remains, however, a need for further research on the adaptive capacities of criminal networks to further our understanding of the drivers of network structure, and to inform law enforcement policy and practiceFootnote4.

Inspired by Morselli and Petit’s original study, this paper investigates how a drug trafficking network recovers and adapts after one of his key players is arrested by law enforcement agencies. It focuses on criminal collaboration patterns in a context of increased law enforcement risk, and on the impact of law enforcement targeting on communication strategies and illegal activities of network members. It combines a quantitative analysis of the main drivers of criminal collaboration – using social network analysis measures and Exponential Random Graph Models (ERGMs) – with a qualitative analysis of the content of wiretapped telephone conversations, which helps make sense of the quantitative results.

This study identifies the social processes that facilitate organisational survival and adaptation. Throughout the analyses, Carlo Morselli’s idea of ‘flexible order’ was a reminder that network structure is not planned but rather emerges from interactionsFootnote5. After law enforcement targeting, criminal network members show a preference for security over efficiency by favouring indirect ties and limiting communication, although criminal collaboration continues. Kinship ties help reduce uncertainty and facilitate trust among network members. While the number of drug consignments decreases after the arrest of the key player, the network maintains its operational activity until it is eventually dismantled a year later when most of its members are arrested.

The paper begins with a discussion of common strategies to target key players in criminal networks, and the impact that they might have based on whether network members will favour efficiency or security. The following section introduces the data and the analytical strategy, and discusses the use of ERGMs for the analysis of the drivers of criminal collaboration. After a section reporting the main findings of the social network analysis and the content analysis of telephone conversations, the final section considers some avenues for future research, and discusses some of the policy implications that can be drawn from empirical analyses of law enforcement targeting and criminal resilience.

Key player targeting and network adaptation

Since Sparrow’s seminal article on criminal network vulnerabilities, scholars have put forward a variety of strategies to identify actors whose removal is likely to lead to network disruptionFootnote6. While suggestions range from focusing on actors’ positioning within the network to targeting individuals who possess certain attributes or resources (e.g., money or specialised skills), there seems to be agreement on the value of adopting a key player strategyFootnote7. Simulation studies have proven that targeting central actors could indeed be effective, especially when law enforcement efforts are concentrated on those with a brokerage position within the networkFootnote8. However, the effectiveness of this approach depends on whether and how criminal networks adapt to disruptionFootnote9.

Most research on key players and their removal has focused on network robustness (i.e., how to increase network vulnerability via targeted interventions) rather than network recovery and adaptation after law enforcement interventionFootnote10. The aftermath of disruption has seldom been considered in criminal network research, leaving us with little information on how network members respond to variation in law enforcement activityFootnote11. This is particularly surprising given that criminal networks are often described as flexible and able to quickly adapt to new conditions and re-organise beyond node replacementFootnote12. Criminal networks need to constantly balance ‘the need to act collectively and the need to assure trust and secrecy in these risky collaborative settings’Footnote13. In the context of increased law enforcement risk, it may be reasonable to assume that the efficiency-security dilemma becomes even more acute.

After law enforcement targeting, network participants are likely to have a higher perception of risk. This may lead them to prioritise security over efficiency in the aftermath of an arrestFootnote14. They might limit interactions with other network participants and minimise communication channels, making the network sparser than beforeFootnote15. Key actors not targeted by law enforcement may reduce their direct involvement in the illicit activities carried out by the group, and start to delegate more. Geodesic distances (i.e., shortest paths between any two nodes) are likely to increase in length, and chain-like patterns of connection may appear or become more prevalentFootnote16. As a result, the network might become more decentralised, with no or fewer highly connected individuals, and a more uniform degree distributionFootnote17.

Whether new individuals enter the network, or new ties are formed between two existing members, trust may drive individual decisions to collaborateFootnote18. Sharing similar individual attributes (e.g., ethnicity, language) can make interaction easier and contributes to building trust between network participants, even when this is based on stereotypes or shared valuesFootnote19. Pre-existing relations might become relevant for recruitmentFootnote20. Kinship and formal organisational ties contribute to reducing uncertainty and increasing trust among network members, thus making collaborations more likelyFootnote21. These types of ties (and multiplex ties more generally) are particularly relevant for criminal collaboration, because they can lead to highly cohesive – and therefore efficient – networks while also building trust among network members, and maintaining some level of security.Footnote22,Footnote23

Despite a preference for security, network members will need to continue engage in profitable illegal activities. The need to re-organise and make up for losses in the aftermath of law enforcement targeting might require even more co-ordination among network members than prior to disruption. Actors with different roles or at different stages of the crime commission process (e.g., drug importation and distribution) might need to communicate frequently to ensure illegal activities are carried out without any further problemsFootnote24. Key actors might become more involved in day-to-day operations, increasing network centralisation as well as their own vulnerabilityFootnote25. New ties will likely shorten geodesic distances and favour collaboration in dense, local groups, resulting in triadic closureFootnote26.

The way in which network actors resolve the efficiency-security dilemma will impact on the internal structure of the criminal group. Adaptation to law enforcement targeting can therefore be understood as a self-organised process that emerges from the way in which the remaining (and new) network participants interact with each otherFootnote27. This study builds on the little yet informative research on law enforcement disruption and illicit network dynamics, and investigates co-offending patterns and communication strategies of the members of a drug trafficking network before and after targetingFootnote28. In contrast to previous research, it adopts a case study approach (vs. a simulation one), goes beyond descriptive networks statistics, and focuses on the impact of key player targeting (vs. seize-but-do-not-arrest strategy). By focusing on how law enforcement control shapes criminal network structure and activity, this study contributes to our understanding of the adaptive capacities of criminal networks and, more generally, of the impact of law enforcement interventions in drug markets.

Data and methods

Empirical analyses of the impact of targeting of key players on the structure, activities, and communication strategies of criminal networks require longitudinal data to observe co-offending patterns both before and after the intervention. Accessing data of this kind can be challenging given that law enforcement agencies rarely gather relevant information after a key actor is removed from the networkFootnote29. The current study focuses on Operation Cicala, a two-year investigation of a criminal network trafficking drugs from Colombia and Morocco to Italy via Spain. The unique nature of the investigation – which saw a key player being arrested mid-investigation, but police monitoring continuing for another year – allows to compare the network before and after targeting, unlike previous research on criminal network dynamics.

While the context of law enforcement control is peculiar to this investigation, the type of data used is common to other analyses of criminal networksFootnote30. The data for the study were extracted from criminal justice records, more specifically, from the request for remanding the suspects in custody. The document was drafted by the state prosecutor at the end of the investigation, and includes relevant evidence against the suspects which was gathered via an extensive use of electronic surveillance, as well as more traditional methods such as covert observation. It contains not only relational data on criminal collaborations, but also information on other types of ties (e.g., kinship and formal organisational ties) and on the persons involved (e.g., their role in the network). The transcripts of wiretapped telephone conversations provide rich information on the suspects’ interactions with other network members, their illegal activities, and any protection methods against law enforcement surveillance.

All coding was done manually given the informal style of conversation and the frequent use of jargonFootnote31. Relational data comprise criminal cooperation – which derives from both telephone and face-to-face conversations between any two suspects –, kinship ties, and formal organisational ties – which are based on the suspects’ affiliation to the ‘Ndrangheta as well as other ethnic criminal organisationsFootnote32,Footnote33. Attribute data include details on the suspects’ nationality, affiliation to the ‘Ndrangheta, main task, role in the drug supply chain, and statusFootnote34. Tasks are based on previous research on drug trafficking, and consider the main activity each individual was involved in (e.g., trafficker, support, courier)Footnote35. Roles instead represent the position of each individual in the drug supply chain – supply, importation, or distribution. Both were often immediately apparent from the wiretapped conversations in the criminal justice records and, following Bright and Delaney’s example, were kept separateFootnote36. The actors’ status was identified based on their formal role within the criminal organisation, and their tendency to give or receive orders in the wiretapped communications reported in the criminal justice records. A dummy variable was also created to identify whether network members were targeted by the Italian law enforcement agencies during the investigation, as it may affect individual connectivity.

The criminal collaboration network is the main focus of the analyses. Three binary, undirected matrices were created for each investigative phase. A combination of ‘event-based’ split and ‘time-based’ split was used to identify the three phasesFootnote37. The first investigative phase starts in November 2008 and ends in June 2009, when N3 – a key player in the trafficking network – was arrested. Given the length of the investigation after N3’s arrest, two more phases were identified after June 2009. They both last 197 days (against the 217 days of the first one), and the third one ends in July 2010, together with the end of the investigation. The two investigative phases after N3’s arrest allow to assess its short- and long-term impact, as well as consider the network’s recovery timeFootnote38. Each network has its own set of attributes to account for changes in the actors’ task and role over timeFootnote39. Separate kinship and formal organisation networks were also created for each phase. includes descriptive statistics for the criminal collaboration network in each phase, and the suspects’ main attributes.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

The analysis combines a quantitative element where Exponential Random Graph Models (ERGMs) are used to identify the main drivers of criminal collaboration in each investigative phase, and a qualitative element where the content of the wiretapped conversations is analysed to make sense of the quantitative results, and add to our understanding of network structure and processesFootnote40. The content analysis helps assess levels of criminal activity in the aftermath of law enforcement targeting, the actors’ perception of risk, and any changes in communication strategies and protection methods against law enforcement surveillanceFootnote41.

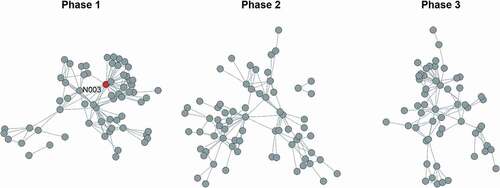

shows the criminal collaboration network in each investigative phase, while identifies changes in observed actors and ties across phases. Temporal models for social networks such as Stochastic Actor-Oriented Models (SAOMs) and Temporal Exponential Random Graph Models (TERGMs) require relative stability of actors across phases, which is not present in the Cicala network. Following the approach taken in prior studies, this paper therefore uses separate ERGMs at each investigative stageFootnote42. ERGMs are a class of statistical models that assess the probability of a tie between two network actors based on node-level attributes (e.g., status), dyad-level attributes (e.g., homophily by task), and network properties (e.g., triad closure)Footnote43. Each ERGM allows to identify the processes that, in each investigative phase, led to tie formation, and whether network members favoured security over efficiency, or vice versa (or a combination of the two). While the ERGMs are not able to explain change in network structure over time, differences across phases may suggest the network adapted after law enforcement intervention.

Table 2. Changes across investigative phases

Figure 1. Criminal collaboration networks across investigative phases

lists the set of parameters included in the models, their statnet name, and their interpretation. In addition to these, two controls were added to account for law enforcement targeting and homophily by nationalityFootnote44. The network analyses were performed using the statnet suite of packages for RFootnote45. For all dyad dependence models, the maximum likelihood was approximated using Markov Chain Monte Carlo simulation methodsFootnote46. The goodness of fit was assessed by comparing the observed networks with simulated ones, and goodness-of-fit plots are reported in the AppendixFootnote47. For a more detailed discussion of ERGM network statistics and their relation to the security-efficiency trade-off, please see Malm et al.’s and Bright et al.’s workFootnote48.

Table 3. ERGM parametersFootnote82

Results

Between November 2008 and June 2009, the criminal network organised nine consignments of cocaine (ranging between 5.2–14.6 kilos), and one consignment of hashish (225 kilos). The drugs were purchased in Spain from suppliers who had contacts with Colombian producers (for cocaine) and Moroccan traffickers (for hashish). The drugs were often hidden in the trucks of N3’s transport company, and smuggled to Italy by one of his couriers together with licit goods. New arrangements continued despite half of the consignments were seized by the Italian law enforcement agencies, suggesting that the group was fairly resilient to drug seizures, and managed to involve new buyers that would finance the purchase of drug in exchange for a share.

When N3 was arrested in June 2009, he had the highest degree centrality score in the network, which was a consequence of his many direct contacts with suppliers in Spain – including a small group of Romanian citizens – and with the employers of his transport company, many of whom were also members of the criminal group. The company was used as a front for the smuggling activities, and the drug was often hidden in trucks to cross the border. N3 also had the highest betweenness centrality score, and acted as a broker between several other network members, such as the suppliers based in Spain, and the wholesale dealers in Italy. The criminal network thus relied on N3, as well as a few other traffickers, to purchase the drug in Spain, and transport it to Italy.

With his high degree and betweenness centrality scores, N3 fits the definition of key player found in the literature on criminal network vulnerabilities. His arrest, however, was not the consequence of a well-thought law enforcement strategy, but rather the result of miscommunication between police forces. In the months approaching his arrest, N3 had been under surveillance by both the Anti-mafia District Directorate of Reggio Calabria – who ran Operation Cicala – and the Anti-mafia District Directorate of Trento. In June 2009, the latter decided to wrap up the evidence and formulate the request for remanding the suspects in custody, including N3. Meanwhile, Operation Cicala was carried on, allowing law enforcement agencies to continue monitoring all remaining suspects and collecting evidence (and network data) for another year.

The descriptive statistics of the criminal collaboration network in show some of the changes in network structure after N3’s arrest. Both the overall network density and the actors’ mean degree dropped in the second investigative phase (from 0.07 to 0.05, and from 4.63 to 3.24, respectively), and only slightly increased towards the end of the investigation. Degree centralisation and the clustering coefficient also decreased after the first investigative phase. After law enforcement intervention, the network became sparser and more decentralised, with fewer dense, local groups, suggesting a stronger focus on security over efficiency. The ERGMs for each investigative phase in offer a better understanding of the drivers of criminal collaboration before and after law enforcement intervention. The interpretation of the parameters is similar to logistic regression coefficients. Positive parameters indicate that the probability of a tie increases if the new tie increases the corresponding network statistic, conditional on the rest of the networkFootnote49.

Table 4. Estimates and standard errors from ERGMs

Before N3’s arrest, actors with high status were more likely to form direct ties than those with medium or low status, suggesting an involvement in day-to-day operations rather than a tendency to delegate. The parameter for homophily by role is also positive and significant, indicating that two actors who have the same role in the drug supply chain are more likely to share a tie than any other pair of actors with different roles. In the second investigative phase, the two parameters are no longer statistically significant. This may suggest that high-status actors limited their direct involvement in trafficking operations and were as likely to form ties as other co-offenders, and that network members reduced their collaboration with those at the same stage of the supply chain, thus reducing the efficiency of the network. The activity spread parameter for high-status actors regains statistical significance in the third and final investigative phase, suggesting an attempt of high-status individuals to bounce back to pre-disruption activity levels.

The parameter for indirect connections is not significant before N3’s arrest. In contrast, chain-like patterns of connection are likely to exist in the third investigative phase, hinting at an increased focus on security after law enforcement intervention. Taken together, these findings suggest a preference for security over efficiency after N3’s arrest, with high-status actors avoiding direct involvement in day-to-day operations in the shorter term, and network members favouring longer communication chains in the longer term. N2 – a trafficker belonging to the same ‘Ndrangheta family as N3 – provides a good example of this behaviour in the phases after law enforcement intervention. Instead of communicating directly with some of the buyers based in Calabria, he sent and received messages via N1, who was also in Calabria and thus able to arrange meetings with them.

Other ERGM parameters are relevant to understand criminal collaboration patterns both before and after N3’s arrest. Sharing kinship ties or formal organisational ties was associated with criminal collaboration in all three investigative phases, suggesting that network members resorted to pre-existing relations to reduce uncertainty and increase trust. For example, in the first investigative phase, N3’s wife and two sons were actively involved in the group’s illicit activities. Kinship ties were also valued among the members of the Moroccan and the Romanian clans, reflecting the importance of trusted relations in criminal contexts and beyond mafia-type organisations. Another similarity across investigative phases is the positive parameter for preferential attachment, which indicates that highly connected actors are more likely to form new ties than peripheral ones. Highly connected actors, however, seem to have changed over time, with traffickers being particularly active in the second investigative phase, and ‘Ndrangheta members being exceptionally careful in the final stages of the investigation, as suggested by the negative and statistically significant parameter for activity spread.

This tendency towards centralisation is paired with a tendency to triadic closure across all investigative phases. Transitivity can lead to highly cohesive networks characterised by quick information sharing and thus efficiency, but can equally foster security by ensuring incriminating or sensitive information does not spread too far in the network. Assortative mixing (i.e., the interaction with similar others) can induce transitivity, since a tie is more likely to form when two actors not only share an indirect tie, but also the same attributeFootnote50. In the criminal network under investigation, kinship and formal organisational ties likely contribute to the observed tendency to triadic closure. As noted earlier, these types of ties are particularly relevant for criminal collaboration, because they build trust among network members and maintain some level of security while simultaneously favouring efficiencyFootnote51.

Changes in network structure after N3’s arrest suggest an increased focus on security by reducing the direct involvement of high-status actors in the aftermath of law enforcement intervention and, in the longer term, by lengthening the distance between any two actors through indirect connections. Despite a reduction in centralisation and clustering scores after the first investigative phase, the network maintained a tendency towards them, while often basing criminal collaboration on pre-existing kinship or formal organisational ties. The observed changes in network structure may be a consequence of a heightened perception of risk after N3’s arrest, which may have contributed to network members modifying their communication strategies and altering their security measures. They might have also been affected by the broader context of law enforcement control. In addition to N3’s arrest, throughout the investigation network members suffered from a series of drug seizures which imposed losses on the criminal network. This led to the creation of subsequent importations to compensate from previous losses, and to the involvement of new buyers to finance these new importations.

The observed changes in network structure may also be, at least partly, a consequence of the data collection strategy and boundary specification criteria. ERGMs assume that network data are complete – which is unlikely to be the case in the context of illicit networks drawn from criminal justice records – and are particularly sensitive to missing data in relatively small networksFootnote52. We also do not have any information about the ‘master network’, that is, the pool of potential co-offenders from which new members are recruitedFootnote53. This is particularly relevant in light of the high turnover between investigative phases observed in the Cicala network, and results in little information on the way in which criminal opportunities arise and new collaborations are formed. With this in mind, the qualitative element of the analyses helps provide some context for the changes observed in the network structure.

The content analysis of wiretapped telephone conversations suggests that criminal network members were aware of the risk of law enforcement control since the beginning of the investigation in November 2008. N3 himself told another member of the group that ‘these phones are tapped … I tell you’Footnote54. Network members therefore used a series of protective measures against surveillance even before N3’s arrest. Most protection methods were specifically intended to counter electronic surveillance and prevent law enforcement agencies from obtaining evidence. While some measures were constantly used by network members, others were adopted after specific events, such as the seizure of a drug consignment or the discovery of bugs in their houses or cars. Changing SIM cards or avoiding telephone communications for a limited period of time was a common measure, as evidenced by the following conversation between N2 and N65 in the aftermath of discovering a bug:

N65: I’m going to throw this thing [phone] away … I was waiting for you to call, and now I can throw it away.

N2: I’m going to throw everything away, too.

The replacement of SIM cards or mobile phones used to communicate with other network members was relatively frequent. The majority of wiretapped telephone lines were used by a small group of 38 actors who frequently changed their SIM cards to avoid law enforcement surveillance. Before his arrest, N3 was particularly careful in his use of mobile phones, and at times scolded his co-offenders for not paying enough attention (‘if you bought two new phones to talk … and we don’t use them … why did you spend money on them?’). The transcripts of wiretapped conversations include a few mentions of alternative communication devices that the police are unable to wiretap, such as Skype and Msn, and of public phones. However, evidence of their use is limited, and the actors who adopted these solutions continued to discuss illegal activities on the telephone, too.

The use of code words was one of the main protective measures adopted by network members since the beginning of the investigation. Co-offenders often used nicknames or ‘network-based paraphrases’ (i.e., paraphrases that represent a feature of the person or kin relations, and that only affiliates can understand) to refer to each otherFootnote55. For example, N6 was ‘the blond girl’, and N29 was ‘the giant’. Code words were also used to discuss illegal activities without openly mentioning them. For example, N5 said that he ‘spent the night with a blond woman [drug], but it was not good [poor quality]’. On another occasion, N10 complained that ‘the fish from last time is gone bad’, that is, the drug was not of good quality. Code words, however, were not necessarily enough to prevent law enforcement agencies from building a case against many network members, especially when their use was inconsistent:

N65: The shoes [drug] are not good quality ones … quality is only 70%.

While neither protective measures nor the content of telephone conversations changed after law enforcement intervention, the number of calls dropped since May 2009, possibly reflecting a stronger focus on security by network members. After N3’s arrest, the number of drug consignments also decreased. In the second investigative phase, the traffickers managed to organise and complete only one importation of 6.8 kilos of cocaine. In March 2010, 12 kilos of cocaine were smuggled to Italy, followed by another importation of cocaine in May, and the importation of 61 kilos of hashish in June, which were seized by law enforcement. The constant increase in the number of wiretapped telephone lines throughout the investigation, and the fact that only in rare occasions network members discussed telephone conversations that had not already been intercepted, may indicate that the investigators were able to identify most new members recruited after law enforcement intervention. However, the opposite conclusion – that is, new network members and trafficking activities remained outside of the investigation’s scope – cannot be completely ruled out.

Law enforcement targeting seems to have impacted on both the internal structure and the trafficking activities of the Cicala network. After N3’s arrest, network members seemed to favour security over efficiency, although criminal collaboration continued. While the remaining network members lost both their contacts with the group of Romanian suppliers, and the possibility to use N3’s transport company to smuggle drugs to Italy, they managed to keep contacts with the suppliers in Spain, and to adapt their modus operandi by smuggling the drug by car. The three drug consignments organised in early 2010 suggest that, after a period of reorganisation, the network adapted and maintained, at least in part, its operational activity before being eventually dismantled by law enforcement following the arrest of most of its members in July 2010.

Discussion

As Morselli notes, ‘criminal networks are not simply social networks operating in criminal contexts’Footnote56. Maximising security and minimising exposure to law enforcement is fundamental to their survival. It is therefore not surprising that, in the aftermath of law enforcement intervention, network members showed a greater tendency to maximise security over efficiency than before N3’s arrest. While the separate ERGMs for each investigative phase could not explain change in network structure over time, they helped identify a reduction in high-status actors’ direct involvement in illicit activities immediately after the arrest of one of the key players, and a preference for indirect ties in the final stage of the investigationFootnote57.

Kinship was confirmed as the ‘hidden glue’ maintaining collaboration in criminal contextsFootnote58. These findings speak to a long and well-established body of knowledge on the importance of familial ties as the foundation of various criminal enterprisesFootnote59. The overlap between kinship and co-offending ties (and formal organisational ties) may have contributed to the adaptive capacities of the Cicala network. Multiplexity and, more specifically, the overlap between personal and criminal connections, has indeed been identified as a source of network resilienceFootnote60. In a context where reciprocal distrust and recourse to violence are common, social relations – including, but not restricted to, kinship ties – contribute to increasing the levels of trust and favour criminal cooperationFootnote61.

In line with previous empirical research, the network favoured efficiency in the first investigative phase, when law enforcement risk was lower, and later decentralised under the pressure of police targetingFootnote62. For example, terrorist networks have been found to increase density and cohesion as they approach the attack stage and need to coordinate the attackFootnote63. These findings, however, are in contrast with Duijn et al.’s simulation results, which predicted a greater focus on efficiency after law enforcement interventionFootnote64. They also describe dynamics that are opposite to those of Bright and Delaney’s network, which was under continual surveillance but never directly targeted, and over time moved away from a focus on security to prioritise efficiency and increase its profitsFootnote65.

These differences could reflect variations in opportunity structures, including those deriving from the ‘master network’ in which the smaller, observed network is embedded in. The Cicala network took time to recover after targeting, suggesting that previous simulations may not have been able to take into account the range of constraints to recruit new members and adapt to increased law enforcement riskFootnote66. For example, they may have downplayed issues of trust that arise when recruiting from the larger pool of available criminals rather than the smaller network of trusted associatesFootnote67. Furthermore, simulations may not have been able to take into account the full complexity of recovery and adaptation processes, which in the case of the Cicala network entailed the recruitment of new members with specific resources, a change in the modus operandi to smuggle drug from Spain to Italy, and the introduction of new distribution chainsFootnote68.

In addition to providing a quantitative and qualitative account of the adaptive capacities of the Cicala network, this study confirms the need for more research on criminal network recovery and adaptation after law enforcement targeting. First, the data and methods used are not free from limitations, which should be addressed in future studies. Law enforcement data only provide a partial picture of the network and are affected by the criminal justice records used as the main source of informationFootnote69. This is especially problematic when ERGMs are used for modelling, because they assume that network data are completeFootnote70. Accessing a wider range of data sources on the same criminal network, and adopting alternative modelling strategies that account for actors’ high turnover, would help address these issues. Analytical strategies that considered different kinds of law enforcement interventions simultaneously could also improve our understanding of network resilience. While N3’s arrest had a considerable impact on the structure and activities of the Cicala network, the economic losses resulting from drug seizures may have also contributed to the observed changes. With little information on the new network members, it also remains difficult to assess whether changes are a consequence of their individual characteristics or of drug seizures and arrestsFootnote71.

Second, a wider range of case studies focusing on different criminal, and drug trafficking, networks in various settings and exposed to various targeting strategies will contribute to a solid knowledge base to produce more realistic simulations. Findings from case studies are limited in their generalisabilityFootnote72. While the current study focused on the arrest of one key player, we know little about the impact of, e.g., the subsequent removal of critical nodesFootnote73. An additional limitation to the generalisability of the current study may be due to the focus on the Italian ‘Ndrangheta rather than looser trafficking networks. Calderoni, however, demonstrated how its formal hierarchy does not play a role when its members are involved in drug trafficking operationsFootnote74. Finally, future studies using temporal models for social networks will allow to further test the efficiency-security trade-off framework, and assess whether it identifies the main determinants of criminal network structureFootnote75.

Empirical contributions on network recovery and adaptation are not only a way to enhance our theoretical understanding of criminal networks, but also a valuable tool to inform law enforcement policy and practice. Sparrow’s rationale for the analysis of criminal network vulnerabilities came from the observation that ‘crime levels are not diminishing, despite countless “successes” against individual criminal enterprises.’Footnote76 While law enforcement agencies have gradually embraced the key player strategy, this tend to be based on the ‘Mr Big’ assumption, and an assessment of its implementation is often missingFootnote77. Whether we can consider the Cicala network resilient ultimately depends on the expected outcomes of law enforcement intervention. N3’s arrest reduced the rate of information flow as well as the ability to organise the purchase, smuggling, and wholesale of drugs, at least temporarilyFootnote78. However, the network remained active for another year after law enforcement intervention, maintained some of its operational activity, and was eventually dismantled only when most of its members were arrested in July 2010Footnote79.

This study is a small, additional piece of evidence suggesting that law enforcement interventions may not be as effective as expected given the flexibility and resilience of drug trafficking networks. Even when entire networks are dismantled by law enforcement following multiple arrests, drug markets show their resilience as new dealers replace those who are sentenced and imprisonedFootnote80. If prohibition remains the preferred policy option by governments, research on the impact of repressive policies on criminal networks structure and activities can help identify effective interventions, and avoid any unintended, harmful consequencesFootnote81.

Acknowledgments

This article is dedicated to Professor Carlo Morselli, who was unlike any other who worked in the field of criminal networks. This article would not exist without his prior work on networks and crime. I would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers and Dr Francesco Calderoni for their constructive and helpful comments that have significantly improved the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Morselli and Petit, “Law-Enforcement Disruption of a Drug Importation Network”.

2. Helfstein and Wright, ‘Covert or Convenient? Evolution of Terror Attack Networks’; Bright and Delaney, “Evolution of a Drug Trafficking Network: Mapping Changes in Network Structure and Function across Time”; Bright, Koskinen, and Malm, “Illicit Network Dynamics: The Formation and Evolution of a Drug Trafficking Network”; Ouellet, Bouchard, and Hart, “Criminal Collaboration and Risk: The Drivers of Al Qaeda’s Network Structure before and after 9/11”; McMillan, Felmlee, and Braines, “Dynamic Patterns of Terrorist Networks: Efficiency and Security in the Evolution of Eleven Islamic Extremist Attack Networks”.

3. Duijn, Kashirin, and Sloot, “The Relative Ineffectiveness of Criminal Network Disruption”; Bright et al., “Criminal Network Vulnerabilities and Adaptations”; Duxbury and Haynie, “Criminal Network Security: An Agent-Based Approach to Evaluating Network Resilience”.

4. Morselli, Inside Criminal Networks.

5. Morselli.

6. Sparrow, “Network Vulnerabilities and Strategic Intelligence in Law Enforcement”.

7. Bright et al., “Criminal Network Vulnerabilities and Adaptations”; Carley, Lee, and Krackhardt, “Destabilising Networks”; Carley, “Destabilisation of Covert Networks”; Robins, “Understanding Individual Behaviours within Covert Networks: The Interplay of Individual Qualities, Psychological Predispositions and Network Effects”; Schwartz and Rouselle, “Using Social Network Analysis to Target Criminal Networks”.

8. Bright et al., “Criminal Network Vulnerabilities and Adaptations”; Cavallaro et al., “Disrupting Resilient Criminal Networks through Data Analysis: The Case of Sicilian Mafia”; Duxbury and Haynie, “Criminal Network Security: An Agent-Based Approach to Evaluating Network Resilience”.

9. Albert and Barabási, “Statistical Mechanics of Complex Networks”; Morselli, Giguere, and Petit, “The Efficiency/Security Trade-off in Criminal Networks”; Duijn, Kashirin, and Sloot, “The Relative Ineffectiveness of Criminal Network Disruption”.

10. Malm and Bichler, “Networks of Collaborating Criminals: Assessing the Structural Vulnerability of Drug Markets”.

11. Morselli and Petit, “Law-Enforcement Disruption of a Drug Importation Network”; Duijn, Kashirin, and Sloot, “The Relative Ineffectiveness of Criminal Network Disruption”; Duxbury and Haynie, “Criminal Network Security: An Agent-Based Approach to Evaluating Network Resilience”.

12. Morselli, Giguere, and Petit, “The Efficiency/Security Trade-off in Criminal Networks”; Bright and Delaney, “Evolution of a Drug Trafficking Network: Mapping Changes in Network Structure and Function across Time”; Morselli and Petit, “Law-Enforcement Disruption of a Drug Importation Network”; Eilstrup-Sangiovanni and Jones, “Assessing the Dangers of Illicit Networks: Why al-Qaida May Be Less Threatening Than Many Think”.

13. Morselli, Giguere, and Petit, “The Efficiency/Security Trade-off in Criminal Networks,” 144.

14. Erickson, “Secret Societies and Social Structure”.

15. Morselli, Inside Criminal Networks; Baker and Faulkner, “The Social Organization of Conspiracy: Illegal Networks in the Heavy Electrical Equipment Industry”.

16. Helfstein and Wright, “Covert or Convenient? Evolution of Terror Attack Networks”; Baker and Faulkner, “The Social Organization of Conspiracy: Illegal Networks in the Heavy Electrical Equipment Industry”; Krebs, “Mapping Networks of Terrorist Cells”; Bright, Koskinen, and Malm, “Illicit Network Dynamics: The Formation and Evolution of a Drug Trafficking Network”.

17. Duxbury and Haynie, “Criminal Network Security: An Agent-Based Approach to Evaluating Network Resilience”.

18. Tremblay, “Searching for Suitable Co-Offenders”; McCarthy, Hagan, and Cohen, “Uncertainty, Cooperation, and Crime: Understanding the Decision to Co-Offend”; Campana and Varese, “Cooperation in Criminal Organisations: Kinship and Violence as Credible Commitments”.

19. von Lampe and Johansen, “Organised Crime and Trust: On the Conceptualisation and Empirical Relevance of Trust in the Context of Criminal Networks”; Grund and Densley, “Ethnic Homophily and Triad Closure: Mapping Internal Gang Structure Using Exponential Random Graph Models”.

20. See note 14 above.

21. Smith and Papachristos, “Trust Thy Crooked Neighbour: Multiplexity in Chicago Organised Crime Networks”; Campana and Varese, “Cooperation in Criminal Organisations: Kinship and Violence as Credible Commitments”.

22. Multiplexity exists when a pair of individuals shares various types of relationships. Please see Kadushin, Understanding Social Networks: Theories, Concepts, and Findings for an introduction and further details.

23. Malm, Bichler, and Van De Walle, “Comparing the Ties That Bind Criminal Networks: Is Blood Thicker than Water?”.

24. Bright and Delaney, “Evolution of a Drug Trafficking Network: Mapping Changes in Network Structure and Function across Time”; Malm and Bichler, “Using Friends for Money: The Positional Importance of Money-Launderers in Organised Crime”.

25. Baker and Faulkner, “The Social Organization of Conspiracy: Illegal Networks in the Heavy Electrical Equipment Industry”; Duijn, Kashirin, and Sloot, “The Relative Ineffectiveness of Criminal Network Disruption”; Morselli, Inside Criminal Networks; Duxbury and Haynie, “Criminal Network Security: An Agent-Based Approach to Evaluating Network Resilience”; Bright, Koskinen, and Malm, “Illicit Network Dynamics: The Formation and Evolution of a Drug Trafficking Network”.

26. Morselli, Giguere, and Petit, “The Efficiency/Security Trade-off in Criminal Networks”.

27. Morselli, Inside Criminal Networks; Baker and Faulkner, “The Social Organization of Conspiracy: Illegal Networks in the Heavy Electrical Equipment Industry”; Duijn, Kashirin, and Sloot, “The Relative Ineffectiveness of Criminal Network Disruption”.

28. Morselli and Petit, “Law-Enforcement Disruption of a Drug Importation Network”; Bright and Delaney, “Evolution of a Drug Trafficking Network: Mapping Changes in Network Structure and Function across Time”; Bright, Koskinen, and Malm, “Illicit Network Dynamics: The Formation and Evolution of a Drug Trafficking Network”; Duijn, Kashirin, and Sloot, “The Relative Ineffectiveness of Criminal Network Disruption”; Duxbury and Haynie, “Criminal Network Security: An Agent-Based Approach to Evaluating Network Resilience”.

29. Morselli, Inside Criminal Networks; Duxbury and Haynie, “Criminal Network Security: An Agent-Based Approach to Evaluating Network Resilience”.

30. Bright, Brewer, and Morselli, “Using Social Network Analysis to Study Crime: Navigating the Challenges of Criminal Justice Records”.

31. Campana and Varese, “Cooperation in Criminal Organisations: Kinship and Violence as Credible Commitments”.

32. The ‘Ndrangheta is a mafia-type criminal organisation of Calabrian origin, with ramifications in other Italian regions and abroad. A brief but informative introduction to the ‘Ndrangheta, and a discussion of its involvement in drug trafficking, can be found in Calderoni (2012).

33. Campana, “Eavesdropping on the Mob: The Functional Diversification of Mafia Activities across Territories”; Malm, Bichler, and Van De Walle, “Comparing the Ties That Bind Criminal Networks: Is Blood Thicker than Water?”.

34. Calderoni, “The Structure of Drug Trafficking Mafias: The ‘Ndrangheta and Cocaine”; Wood, “The Structure and Vulnerability of a Drug Trafficking Collaboration Network”.

35. Calderoni, “The Structure of Drug Trafficking Mafias: The ‘Ndrangheta and Cocaine”.

36. Bright and Delaney, “Evolution of a Drug Trafficking Network: Mapping Changes in Network Structure and Function across Time”.

37. Bright and Delaney.

38. See note 17above.

39. See note 36 above.

40. Vargas, “Criminal Group Embeddedness and the Adverse Effects of Arresting a Gang’s Leader: A Comparative Case Study”; Morselli, Inside Criminal Networks.

41. See note 17 above.

42. Ouellet, Bouchard, and Hart, “Criminal Collaboration and Risk: The Drivers of Al Qaeda’s Network Structure before and after 9/11ʹ; Gill et al., “Lethal Connections: The Determinants of Network Connections in the Provitional Irish Republican Army, 1979–1998ʹ.

43. Lusher, Koskinen, and Robins, Exponential Random Graph Models for Social Networks: Theory, Methods, and Applications; Robins et al., “An Introduction to Exponential Random Graph (P*) Models for Social Networks”.

44. Baker and Faulkner, “The Social Organization of Conspiracy: Illegal Networks in the Heavy Electrical Equipment Industry”; Campana and Varese, “Cooperation in Criminal Organisations: Kinship and Violence as Credible Commitments”.

45. Handcock et al., ergm; Butts, sna: Tools for Social Network Analysis; R Core Team, R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.

46. Hunter et al., “ergm: A Package to Fit, Simulate and Diagnose Exponential-Family Models for Networks”.

47. Hunter, Goodreau, and Handcock, “Goodness of Fit of Social Network Models”.

48. Malm, Bichler, and Van De Walle, “Comparing the Ties That Bind Criminal Networks: Is Blood Thicker than Water?”; Bright, Koskinen, and Malm, “Illicit Network Dynamics: The Formation and Evolution of a Drug Trafficking Network”; see also McMillan, Felmlee, and Braines, “Dynamic Patterns of Terrorist Networks: Efficiency and Security in the Evolution of Eleven Islamic Extremist Attack Networks”.

49. Ouellet, Bouchard, and Hart, “Criminal Collaboration and Risk: The Drivers of Al Qaeda’s Network Structure before and after 9/11ʹ.

50. Goodreau, Kitts, and Morris, “Birds of a Feather, or Friend of a Friend? Using Exponential Random Graph Models to Investigate Adolescent Social Networks”.

51. I would like to thank the anonymous reviewer for their suggestions on how to improve the interpretation of triadic closure in the context of the security-efficiency trade-off.

52. See note 30 above.

53. Morselli, Inside Criminal Networks, 168.

54. All excerpts from criminal justice records are the author’s translation from Italian.

55. Gambetta, Codes of the Underworld: How Criminals Communicate, 245.

56. Morselli, Inside Criminal Networks, 8.

57. Bright, Koskinen, and Malm, “Illicit Network Dynamics: The Formation and Evolution of a Drug Trafficking Network”.

58. Malm, Bichler, and Van De Walle, “Comparing the Ties That Bind Criminal Networks: Is Blood Thicker than Water?”, 69.

59. Paoli, Mafia Brotherhoods: Organised Crime, Italian Style; Antonopolous, “Cigarette Smuggling: A Case Study of a Smuggling Network in Greece”; Zhang, Chin, and Miller, “Women’s Participation in Chinese Transnational Human Smuggling: A Gendered Market Perspective”.

60. Morselli and Petit, “Law-Enforcement Disruption of a Drug Importation Network”; Malm, Bichler, and Van De Walle, “Comparing the Ties That Bind Criminal Networks: Is Blood Thicker than Water?”

61. Kleemans and van de Bunt, “The Social Embeddedness of Organised Crime”; Paoli and Reuter, “Drug Trafficking and Ethnic Minorities in Western Europe”; van de Bunt, Siegel, and Zaitch, “The Social Embeddedness of Organised Crime”; von Lampe and Johansen, “Organised Crime and Trust: On the Conceptualisation and Empirical Relevance of Trust in the Context of Criminal Networks”; Gambetta, “Mafia: The Price of Distrust”.

62. Morselli and Petit, “Law-Enforcement Disruption of a Drug Importation Network”; Ouellet, Bouchard, and Hart, “Criminal Collaboration and Risk: The Drivers of Al Qaeda’s Network Structure before and after 9/11ʹ.

63. Helfstein and Wright, “Covert or Convenient? Evolution of Terror Attack Networks”; McMillan, Felmlee, and Braines, “Dynamic Patterns of Terrorist Networks: Efficiency and Security in the Evolution of Eleven Islamic Extremist Attack Networks”.

64. Duijn, Kashirin, and Sloot, “The Relative Ineffectiveness of Criminal Network Disruption”.

65. See note 36 above.

66. Duxbury and Haynie, “Criminal Network Security: An Agent-Based Approach to Evaluating Network Resilience”; Duijn, Kashirin, and Sloot, “The Relative Ineffectiveness of Criminal Network Disruption”.

67. Gambetta, Codes of the Underworld: How Criminals Communicate; Bright et al., “Criminal Network Vulnerabilities and Adaptations”.

68. Williams, “Transnational Criminal Networks”; Morselli and Petit, “Law-Enforcement Disruption of a Drug Importation Network”; Bright and Delaney, “Evolution of a Drug Trafficking Network: Mapping Changes in Network Structure and Function across Time”.

69. Campana and Varese, “Listening to the Wire: Criteria and Techniques for the Quantitative Analysis of Phone Intercepts”; Berlusconi, “Do All the Pieces Matter? Assessing the Reliability of Law Enforcement Data Sources for the Network Analysis of Wire Taps”.

70. Malm, Bichler, and Van De Walle, “Comparing the Ties That Bind Criminal Networks: Is Blood Thicker than Water?”

71. See note 49 above.

72. Bright et al., “Criminal Network Vulnerabilities and Adaptations”.

73. Duijn, Kashirin, and Sloot, “The Relative Ineffectiveness of Criminal Network Disruption”; Duxbury and Haynie, “Criminal Network Security: An Agent-Based Approach to Evaluating Network Resilience”.

74. See note 35 above.

75. See note 17 above.

76. Sparrow, “Network Vulnerabilities and Strategic Intelligence in Law Enforcement”, 256.

77. See note 4 above.

78. See note 64 above.

79. Morselli and Petit, “Law-Enforcement Disruption of a Drug Importation Network”; Bright and Delaney, “Evolution of a Drug Trafficking Network: Mapping Changes in Network Structure and Function across Time”.

80. Bouchard, “On the Resilience of Illegal Drug Markets”; Duijn, Kashirin, and Sloot, “The Relative Ineffectiveness of Criminal Network Disruption”.

81. Dickenson, “The Impact of Leadership Removal on Mexican Drug Trafficking Organizations”; Vargas, “Criminal Group Embeddedness and the Adverse Effects of Arresting a Gang”s Leader: A Comparative Case Study.

82. Adaptation of Lusher, Koskinen, and Robins, Exponential Random Graph Models for Social Networks: Theory, Methods, and Applications, 175.

Bibliography

- Albert, R., and A.-L. Barabási. “Statistical Mechanics of Complex Networks.” Reviews of Modern Physics 74, no. 1 (2002): 47–97. doi:https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.74.47.

- Antonopolous, G. A. “Cigarette Smuggling: A Case Study of A Smuggling Network in Greece.” European Journal of Crime, Criminal Law and Criminal Justice 14, no. 3 (2006): 239–255. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/157181706778526504.

- Baker, W. E., and R. R. Faulkner. “The Social Organization of Conspiracy: Illegal Networks in the Heavy Electrical Equipment Industry.” American Sociological Review 58, no. 6 (1993): 837–860. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2095954.

- Berlusconi, G. “Do All the Pieces Matter? Assessing the Reliability of Law Enforcement Data Sources for the Network Analysis of Wire Taps.” Global Crime 14, no. 1 (2013): 61–81. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17440572.2012.746940.

- Bouchard, M. “On the Resilience of Illegal Drug Markets.” Global Crime 8, no. 4 (2007): 325–344. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17440570701739702.

- Bright, D. A., R. Brewer, and C. Morselli. “Using Social Network Analysis to Study Crime: Navigating the Challenges of Criminal Justice Records.” Social Networks 66 (2021): 50–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2021.01.006.

- Bright, D. A., and J. J. Delaney. “Evolution of a Drug Trafficking Network: Mapping Changes in Network Structure and Function across Time.” Global Crime 14, no. 2–3 (2013): 238–260.

- Bright, D. A., C. Greenhill, T. Britz, A. Ritter, and C. Morselli. “Criminal Network Vulnerabilities and Adaptations.” Global Crime 18, no. 4 (2017): 424–441. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17440572.2017.1377614.

- Bright, D. A., J. Koskinen, and A. E. Malm. “Illicit Network Dynamics: The Formation and Evolution of a Drug Trafficking Network.” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 35 (2019): 237–258. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-018-9379-8.

- Butts, C. T. sna: Tools for Social Network Analysis (version 2.6). R package, 2020. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=sna

- Calderoni, F. “The Structure of Drug Trafficking Mafias: The ‘Ndrangheta and Cocaine.” Crime, Law, and Social Change 58, no. 3 (2012): 321–349. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-012-9387-9.

- Campana, P. “Eavesdropping on the Mob: The Functional Diversification of Mafia Activities across Territories.” European Journal of Criminology 8, no. 3 (2011): 213–228. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370811403442.

- Campana, P., and F. Varese. “Listening to the Wire: Criteria and Techniques for the Quantitative Analysis of Phone Intercepts.” Trends in Organized Crime 15, no. 1 (2012): 13–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-011-9131-3.

- Campana, P., and F. Varese. “Cooperation in Criminal Organisations: Kinship and Violence as Credible Commitments.” Rationality and Society 25, no. 3 (2013): 263–289. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1043463113481202.

- Carley, K. M. “Destabilization of Covert Networks.” Computational and Mathematical Organization Theory 12 (2006): 51–66. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10588-006-7083-y.

- Carley, K. M., J.-S. Lee, and D. Krackhardt. “Destabilizing Networks.” Connections 24, no. 3 (2002): 79–92.

- Cavallaro, L., A. Ficara, P. De Meo, G. Fiumara, S. Catanese, O. Bagdasar, S. Wei, and A. Liotta. “Disrupting Resilient Criminal Networks through Data Analysis: The Case of Sicilian Mafia.” PLOS ONE 15, no. 8 (2020): e0236476. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236476.

- Dickenson, M. “The Impact of Leadership Removal on Mexican Drug Trafficking Organizations.” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 30, no. 4 (2014): 651–676. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-014-9218-5.

- Duijn, P. A. C., V. Kashirin, and P. M. A. Sloot. “The Relative Ineffectiveness of Criminal Network Disruption.” Scientific Reports 4 (2014): 4238. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/srep04238.

- Duxbury, S. W., and D. L. Haynie. “Criminal Network Security: An Agent-Based Approach to Evaluating Network Resilience.” Criminology 57, no. 2 (2019): 314–342. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12203.

- Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, M., and C. Jones. “Assessing the Dangers of Illicit Networks: Why al-Qaida May Be Less Threatening than Many Think.” International Security 33, no. 2 (2008): 7–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/isec.2008.33.2.7.

- Erickson, B. H. “Secret Societies and Social Structure.” Social Forces 60, no. 1 (1981): 188–210. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2577940.

- Gambetta, D. “Mafia: The Price of Distrust.” In Trust: Making & Breaking Cooperative Relations, edited by D. Gambetta and . Oxford: Basic Blackwell 158–175 , 1988.

- Gambetta, D. Codes of the Underworld: How Criminals Communicate. Princeton & Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2009.

- Gill, P., J. Lee, K. R. Rethemeyer, J. Horgan, and V. Asal. “Lethal Connections: The Determinants of Network Connections in the Provitional Irish Republican Army, 1979-1998.” International Interactions 40, no. 1 (2014): 52–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03050629.2013.863190.

- Goodreau, S. M., J. A. Kitts, and M. Morris. “Birds of a Feather, or Friend of a Friend? Using Exponential Random Graph Models to Investigate Adolescent Social Networks.” Demography 46 (2009): 103–125. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.0.0045.

- Grund, T. U., and J. A. Densley. “Ethnic Homophily and Triad Closure: Mapping Internal Gang Structure Using Exponential Random Graph Models.” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 31, no. 3 (2015): 354–370. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1043986214553377.

- Handcock, M. S., D. R. Hunter, C. T. Butts, S. M. Goodreau, P. N. Krivitsky, and M. Morris. ergm (Version 4.1.2). R package, 2021 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ergm.

- Helfstein, S., and D. Wright. “Covert or Convenient? Evolution of Terror Attack Networks.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 55, no. 5 (2011): 785–813. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002710393919.

- Hunter, D. R., S. M. Goodreau, and M. S. Handcock. “Goodness of Fit of Social Network Models.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 103, no. 481 (2008): 248–258. doi:https://doi.org/10.1198/016214507000000446.

- Hunter, D. R., M. S. Handcock, C. T. Butts, S. M. Goodreau, and M. Morris. “Ergm: A Package to Fit, Simulate and Diagnose Exponential-Family Models for Networks.” Journal of Statistical Software 24, no. 3 (2008). doi:https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v024.i03.

- Kleemans, E. R., and H. van de Bunt. “The Social Embeddedness of Organized Crime.” Transnational Organized Crime 5, no. 1 (1999): 19–36.

- Krebs, V. E. “Mapping Networks of Terrorist Cells.” Connections 24, no. 3 (2001): 43–52.

- Lusher, D., J. Koskinen, and G. Robins, eds. Exponential Random Graph Models for Social Networks: Theory, Methods, and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Malm, A., and G. Bichler. “Using Friends for Money: The Positional Importance of Money-Launderers in Organized Crime.” Trends in Organized Crime 16, no. 4 (2013): 365–381. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-013-9205-5.

- Malm, A. E., and G. M. Bichler. “Networks of Collaborating Criminals: Assessing the Structural Vulnerability of Drug Markets.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 48, no. 2 (2011): 271–297. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427810391535.

- Malm, A. E., G. M. Bichler, and S. Van De Walle. “Comparing the Ties that Bind Criminal Networks: Is Blood Thicker than Water?’.” Security Journal 23, no. 1 (2010): 52–74. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/sj.2009.18.

- McCarthy, B., J. Hagan, and L. E. Cohen. “Uncertainty, Cooperation, and Crime: Understanding the Decision to Co-Offend.” Social Forces 77, no. 1 (1998): 155–184. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/3006013.

- McMillan, C., D. Felmlee, and D. Braines. “Dynamic Patterns of Terrorist Networks: Efficiency and Security in the Evolution of Eleven Islamic Extremist Attack Networks.” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 36 (2020): 559–581. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-019-09426-9.

- Morselli, C. Inside Criminal Networks. New York, NY: Springer, 2009.

- Morselli, C., C. Giguere, and K. Petit. “The Efficiency/Security Trade-off in Criminal Networks.” Social Networks 29, no. 1 (2007): 143–153. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2006.05.001.

- Morselli, C., and K. Petit. “Law-Enforcement Disruption of a Drug Importation Network.” Global Crime 8, no. 2 (2007): 109–130. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17440570701362208.

- Ouellet, M., M. Bouchard, and M. Hart. “Criminal Collaboration and Risk: The Drivers of Al Qaeda’s Network Structure before and after 9/11.” Social Networks 51 (2017): 171–177. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2017.01.005.

- Paoli, L. Mafia Brotherhoods: Organized Crime, Italian Style. (Original edition: “Fratelli di Mafia: Cosa Nostra e ‘Ndrangheta”, Il Mulino, Bologna, 2000). New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Paoli, L., and P. Reuter. “Drug Trafficking and Ethnic Minorities in Western Europe.” European Journal of Criminology 5, no. 1 (2008): 13–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370807084223.

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (version 4.1.1). Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2021. https://www.R-project.org

- Robins, G. “Understanding Individual Behaviors within Covert Networks: The Interplay of Individual Qualities, Psychological Predispositions and Network Effects.” Trends in Organized Crime 12, no. 2 (2009): 166–187. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-008-9059-4.

- Robins, G., P. Pattison, Y. Kalish, and D. Lusher. “An Introduction to Exponential Random Graph (P*) Models for Social Networks.” Social Networks 29 (2007): 173–191. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2006.08.002.

- Schwartz, D. M., and T. D. A. Rouselle. “Using Social Network Analysis to Target Criminal Networks.” Trends in Organized Crime 12, no. 2 (2009): 188–207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-008-9046-9.

- Smith, C. M., and A. V. Papachristos. “Trust Thy Crooked Neighbor: Multiplexity in Chicago Organized Crime Networks.” American Sociological Review 81, no. 4 (2016): 644–667. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122416650149.

- Sparrow, M. K. “Network Vulnerabilities and Strategic Intelligence in Law Enforcement.” International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence 5, no. 3 (1991): 255–274. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08850609108435181.

- Tremblay, P. “Searching for Suitable Co-Offenders.” In Routine Activity and Rational Choice: Advances in Criminological Theory, edited by R. V. Clarke and M. Felson, 17–36. Vol. 5. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1993.

- van de Bunt, H. G., D. Siegel, and D. Zaitch. “The Social Embeddedness of Organized Crime.” In The Oxford Handbook on Organized Crime, edited by L. Paoli, 321–339. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Vargas, R. “Criminal Group Embeddedness and the Adverse Effects of Arresting A Gang’s Leader: A Comparative Case Study.” Criminology 52, no. 2 (2014): 143–168. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12033.

- Von Lampe, K., and P. Ole Johansen. “Organized Crime and Trust: On the Conceptualization and Empirical Relevance of Trust in the Context of Criminal Networks.” Global Crime 6, no. 2 (2004): 159–184. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17440570500096734.

- Williams, P. “Transnational Criminal Networks.” In Networks and Netwars: The Future of Terror, Crime, and Militancy, edited by D. F. Ronfeldt and J. Arquilla, 61–97. Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2001.

- Wood, G. “The Structure and Vulnerability of a Drug Trafficking Collaboration Network.” Social Networks 48 (2017): 1–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2016.07.001.

- Zhang, S. X., K. Chin, and J. Miller. “Women’s Participation in Chinese Transnational Human Smuggling: A Gendered Market Perspective.” Criminology 45, no. 3 (2007): 699–733. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2007.00085.x.

Appendix

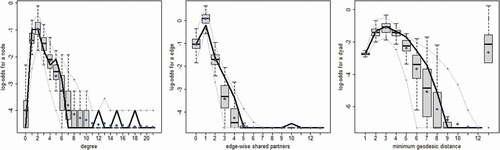

below present the goodness-of-fit plots for the three models in . The three columns represent the statistics for the degree distribution (left), the distribution of shared partners (centre), and the distribution of geodesic distances (right). The dark solid line represents the observed statistic in the network whereas the box plots represent the same statistic for 100 simulated networks. Despite including a statistic for triadic closure (gwesp), the models underestimate the level of clustering in the networks. This suggests that there might be some assortative mixing processes that are not captured in the models (e.g., because of limited information on the network actors). Overall, the models do a fair job estimating the distribution of geodesic distances, which is not directly related to any of the terms included the models.