Abstract

With the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) showing uneven progress, this review identifies possible limitations arising from the MDG framework itself rather than extrinsic issues. A multidisciplinary literature review was conducted with a focus on limitations in the formulation of the MDGs, their structure, content and implementation. Of 1837 MDG-related articles, 90 met criteria for analysis. Articles describe MDGs as being created by only a few stakeholders without adequate involvement by developing countries and overlooking development objectives previously agreed upon. Others claim MDGs are unachievable and simplistic, not adapted to national needs, do not specify accountable parties and reinforce vertical interventions. While MDGs have promoted increased health and well-being in many countries by recognising and deliberating on the possible constraints of the MDG framework, the post-2015 agenda may have even greater impact.

Introduction

In September 2001, based upon the Millennium Declaration, the United Nations (UN) presented the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) as a list of common goals for the world community to achieve by 2015. Since then, remarkable progress has been made towards achieving the MDGs. According to the UN MDG Report 2012, the proportion of people living on less than $1.25 has decreased from 47% in 1990 to 24% in 2008 (from 2 to 1.4 billion). This indicates that Target 1 – Halve the proportion of people living on less than one dollar a day – will be reached by 2015 (UN, Citation2012). Child mortality (Target 4.A) has been steadily decreasing globally, and immunisation rates are over 90% in almost two-thirds of all countries (Overseas Development Institute [ODI], Citation2010). Enrolment rates of primary schools increased from 58 to 76% in sub-Saharan Africa between 1999 and 2010, professional assistance during childbirth has improved from 55% in 1990 to 65% in 2010 (Indicator 5.2) and the aimed reduction of slum dwellers by 100 million (Target 7.D) is already achieved (UN, Citation2012).

However, progress across all MDGs has been limited and uneven across countries. An estimated 15.5% of the world population still suffers from hunger, and many countries, particularly on the African continent, are unlikely to meet the targeted two-thirds reduction in child mortality by 2015 (ODI, Citation2010; UN, Citation2012). The reduction in maternal mortality (Target 5.A) has been slow and mortality remains alarmingly high (UN, Citation2012). In sub-Saharan regions and Southern Asia, where 80% of people in extreme poverty live, progress in reaching MDGs has generally been very limited (UN, Citation2012).

Progress towards Goal 8 (‘Develop a global partnership for development’) – the only MDG directed specifically at high-income countries – has been disappointing. As a possible result of the global financial crisis, development aid has fallen for the first time in more than a decade (UN, Citation2012). In instances where MDGs have been achieved, some of these successes are considered a ‘by-product of the rapid economic growth of China and India’ rather than achievements of MDG-oriented activities (Curtis & Poon, Citation2009).

A variety of reasons for shortfalls in progress towards the MDGs are discussed in the literature. UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon links the lack of progress to ‘unmet commitments, inadequate resources, lack of focus and accountability, and insufficient interest in sustainable development’ (UN, Citation2010). For others, the MDGs cannot be fully met because of how the goals were designed (Clemens, Kenny, & Moss, Citation2007).

Within the literature about successes and shortfalls of the MDGs across the world, there has been very little direct examination of the framework of the MDGs. To more fully understand the possible intrinsic limitations within the MDG framework, we conducted a multidisciplinary literature review that identifies limitations in the development, formulation and content of the MDGs themselves. With less than two years remaining before the MDG deadline, it is critical to the development of a post-2015 agenda to understand these limitations and any lessons that can be learned.

Methods

The review was conducted between July and August 2012 and surveyed the literature in English using MEDLINE and Web of Science databases. MEDLINE was chosen because health is a major component of MDGs and any perceived weaknesses of the MDG framework as reported by researchers and practitioners in the health field was, therefore, considered especially relevant. Web of Science adds other peer-reviewed journals as well as news articles, editorials and book chapters in the areas of natural sciences, social sciences, economics, humanities and development.

The search terms were ‘Millennium Development Goal/s’ in the title, abstract or keywords. Articles were screened first by title, then by abstract and finally, by full text. All articles referring to challenges, weaknesses or lessons that were intrinsically related to the MDG framework's creation, concept, structure, content and implementation were included. Articles were excluded if they (1) showed no relation to the MDG framework, (2) did not discuss any challenges with the MDGs, (3) discussed challenges extrinsic to the MDG framework such as the lack of financial or local political commitment or (4) did not contain original research or viewpoints (e.g. book reviews). It should be noted that articles were selected precisely because they discussed challenges that may appear to be biased samples; only 15% of MDG-related publications expressed concerns with the MDGs and only one-third of these discussed intrinsic limitations. While much of the literature may discuss the successes of the MDGs or extrinsic factors causing limited progress, this study focuses on the relatively under-examined area of challenges arising from the MDG framework itself.

To aid in a systematic analysis and synthesis of the selected literature, a conceptual framework was developed that consisted of four potential challenges related to the MDG framework:

Limitations in the MDG development process.

Limitations in the MDG structure.

Limitations in the MDG content.

Limitations in the MDG implementation and enforcement.

Some arguments and discussions found in the literature belonged to more than one theme and were assigned for analysis to the most relevant theme by the lead author.

Findings

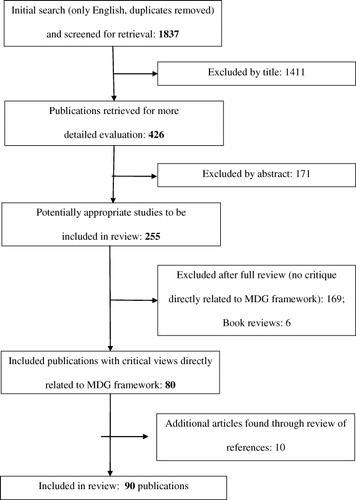

The initial search produced 1837 articles (). A large majority of these were excluded, as they described current MDG progress and strategies on reaching the MDGs but did not examine the MDGs themselves. After screening the titles and the abstracts, the remaining 259 articles described challenges and weaknesses of the MDGs and were fully reviewed. Of these, 80 articles included a discussion of intrinsic limitations of the MDG framework, with the others focusing on extrinsic barriers, such as the financial crisis, lack of political will, etc. Ten additional publications that were appreciably cited by these 80 articles were also added as key references.

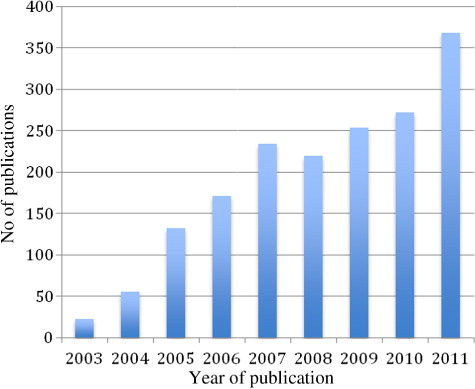

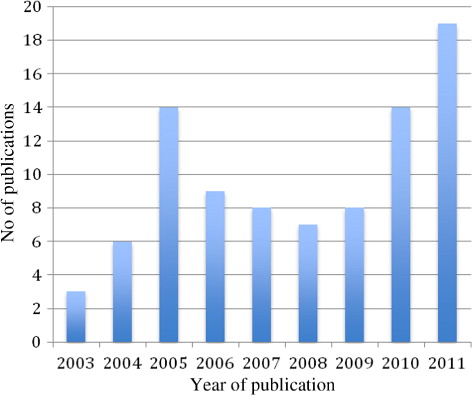

As 2015 approaches, the annual number of publications related to the MDGs and to their intrinsic limitations has increased ( and ). Of all MDG-related articles published each year, 3–10% discuss intrinsic challenges.

1. Limitations in the MDG development process

Critical discussion on the formulation of the MDGs focuses on who identified the goals and targets, how and why certain goals were chosen and what political agendas influenced the structure of the MDGs. The overall creation process of the MDG framework was, as Amin (Citation2006) describes, driven by the triad ‘United States, Europe and Japan’, and co-sponsored by the World Bank, International Monetary Fund and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). According to Eyben (Citation2006), the gender target was restricted to parity in education because the Japanese representative would not agree to broader targets originally proposed by the gender specialists. A small number of UN members influenced the initial rejection of a reproductive health goal. As Hulme (Citation2010) calls it, the ‘unholy alliance’ of the Vatican and conservative Islamic states made the goal disappear from the original MDG list. Oya (Citation2011) and Saith (Citation2006) believe that it was the significant influence of the World Bank that set the main indicator for poverty reduction as the proportion of people living below the poverty line of $1 per day. The exclusiveness of the actors who guided development of the MDGs is underscored by Richard et al. (Citation2011) who add that ‘only 22% of the world's national parliaments formally discussed the MDGs’. Generally, there was very little involvement of developing countries and civil society constituencies in the creational process (Kabeer, Citation2005; Waage et al., Citation2010).

Bond (Citation2006) and Amin (Citation2006) describe the underlying political and conceptual agenda of the MDG framework that carries doctrinaire and characteristics suiting the interests of ‘corporations and rich states’ (Fukuda-Parr, Citation2010). Saith (Citation2007) even adds the provocative formula ‘neo-liberal globalisation + MDGs = development’.

In contrast, the MDGs are also often described as being an outcome of various global summits in the 1990s. Yet several authors believe that for political reasons some ‘hard-fought goals’ got left behind, such as the importance of reproductive health agreed upon in the International Conference on Population and Development (Cairo, 1994) and the Fourth World Conference on Women (Beijing, 1995; Haines & Cassels, Citation2004; Mohindra & Nikiema, Citation2010). Pogge (Citation2004) sees MDG 1 (‘Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger’) as being far less ambitious when compared to the poverty reduction goal set at the 1996 World Food Summit in Rome. With the MDGs, the choice was made to halve the proportion of people suffering from hunger and poverty instead of halving the absolute numbers of people suffering. Pogge calculates that this would result in a reduction of only 101.5 million instead of 547 million people living on less than $1 per day. In regard to education, Robinson (Citation2005) explains that only two out of the three timed goals discussed at the Dakar World Education Forum in 2000 were included in the MDGs; the target of adult literacy, especially for women, and equitable access to basic and continuing education for all adults were not integrated into the MDGs.

Fukuda-Parr (Citation2010) doubts that the original intent of eight goals – to be indicators of progress in the implementation of the objectives presented in the Millennium Declaration – was indeed achieved in the formulation of the MDGs. Various authors explain that only one of the seven key objectives of the Declaration (that of development and poverty eradication) became fundamental to the MDG framework, whereas other goals such as peace, security, disarmament, human rights and democracy were left behind (Hill, Mansoor, & Claudio, Citation2010; Waage et al., Citation2010). Langford (Citation2010) writes that the MDGs of ‘gender equality and the empowerment of women’ were narrowed down to gender equality in education, and the target for ‘affordable water’ was dropped from the MDG list in order to allow for privatisation in the sector.

2. Limitations in the MDG structure

Multiple authors call the goals ‘overambitious’ or ‘unrealistic’ and believe the MDGs ignore the limited local capacities, particularly missing governance capabilities (Mishra, Citation2004; Oya, Citation2011). In contrast, Barnes and Brown (Citation2011) call the MDGs ‘unambitious when viewed against the sheer volume of unmet basic human needs’. For Langford (Citation2010), global goals for low- and middle-income countries fall short because they are too ambitious for some countries and not challenging enough for other countries.

Creating a list of goals – a ‘shopping-list approach’ – risks the omission of important issues and underinvestment in other key areas of development (Keyzer & Van Wesenbeeck, Citation2006). Hayman (Citation2007) argues that the limited list of MDGs makes it easy for donors to justify policies exclusively focused on MDG targets. The MDGs represent a ‘Faustian bargain’ because a consensus was achieved only by ‘major sacrifice’ (Gore, Citation2010). Saith (Citation2006) adds that by concentrating largely on developing countries, the MDG framework serves to ‘ghettoize the problem of development and locates it firmly in the third world’. Using the goals and targets as country-specific goals, according to AbouZahr and Boerma (Citation2010), gives too little consideration to national baselines, contexts and implementation capacities.

Another point of critique of Van Norren (Citation2012) is the focusing of development efforts on such a reduced list of goals and neglecting their interconnectedness. For example, having separate maternal and child health goals results in separating strongly linked maternal and newborn issues (Brikci & Holder, Citation2011). Similarly, Molyneux (Citation2008) points at the separate focus on malaria and HIV that misses the necessity and opportunity to address the synergism between the control and treatment of these communicable diseases. Waage et al. (Citation2010) write that ‘a common, cross-sectoral vision of development’ was not part of the formulation of the MDGs and has resulted in fragmentation, incoherence and gaps in the existing framework.

The absence of accountability for every MDG (except Goal 8) is another conceptual weakness of the MDG framework identified in the literature (Davis, Citation2011; Van Ginneken, Citation2011). Other authors explain that making MDGs national priorities without the initial participation and consultation of developing countries has led to a lack of national ownership for the goals (Fukuda-Parr, Citation2006; Haines & Cassels, Citation2004).

3. Limitations in the MDG content

Even though equality was defined as a core value of the Millennium Declaration, the most often mentioned omission found in the literature is that equity and equality (often used interchangeably) are insufficiently addressed.

Fukuda-Parr (Citation2010) sees a missing goal for reducing inequality within and between countries. Others identify a missing focus on the ‘poorest of the poor’, masked by using national averages or aggregated information (Brikci & Holder, Citation2011). Vandemoortele (Citation2011) even calls it a ‘tyranny of averages’ where issues of inclusive and equitable progress are ignored within the framework due to ‘abstractions and over-generalization’. Others are concerned that the MDGs even push towards un-egalitarian outcomes because most health initiatives would first reach mainly the better-off parts of society (Gwatkin, Citation2005; Waage et al., Citation2010). Reidpath, Morel, Mecaskey, and Allotey (Citation2009) underline this concern referring to MDG 4 where the reduction of under-five mortality rate is easier to reach through targeting those easier to access and leaving out the worst off.

Specifically in regard to MDG 3, authors point out that a target of decreasing gender disparities is not the same as ending gender inequality since focus is reduced to numerical imbalances, whereas substantive asymmetries are left unaddressed (Kabeer, Citation2005; Subrahmanian, Citation2005). Mohindra and Nikiema (Citation2010) criticise the lack of MDG objectives for gender-based violence and economic discrimination.

For Maxwell (Citation2003), the formulation of poverty reduction in MDG 1 ‘prioritizes material aspects of deprivation over non-material ones’ and leads to a reduced concept of poverty. Targeting only 50% of the poor population is believed by some to be unethical and failing to be ‘forward looking’ (Poku & Whitman, Citation2011; Saith, Citation2006). Others consider it oversimplifying for the World Bank to set a specific poverty line of $1 per day (Edward, Citation2006). Pogge (Citation2010) questions the choice of the poverty line which, set at $2.50, would have shown no improvement between 1981 and 2005 and, thus, the $1 per day threshold has been set in order to show progress.

Several authors are concerned that the MDGs fail to include political and human rights. In Ziai's (Citation2011) view, MDG targets are presented not as political but as technical problems, where the solution appears as simply increasing financial resources. A limited focus on only poverty reduction risks to obscure ‘important trade-offs and conflicts of interest’ (Maxwell, Citation2003). In general, civil, political or human rights are not represented enough in the MDG framework, given they represent an important and enduring global consensus (Fukuda-Parr, Citation2010; Saith, Citation2006). Cecchini and Notti (Citation2011) argue that a human rights orientation could have had a positive impact on monitoring and synergism within the MDG framework.

Easterly (Citation2009) describes targets and indicators as ‘unfair to poor countries’, and in particular for Africa because of the way they are constructed. The author explains that MDGs are more difficult to reach for the worst-off countries and are, therefore, drawing a darker picture of the progress made in those regions. He argues that measuring changes in proportions make it harder for countries with worse baselines to show progress. Halving poverty rates from 10 to 5% in Latin America represents more progress (50% poverty reduction) than ‘cutting poverty from 50 to 35%’ in Africa (only 30% reduction).

Of particular concern regarding MDG 2 (‘Achieve universal primary education’) is the limited focus on primary education only, while ignoring the importance of secondary and post-secondary education (Mekonen, Citation2010; Tarabini, Citation2010). Lewin (Citation2005) points out that pushing for primary education results in more graduates that then do not have the opportunity for further education in developing economies. MDG 2 particularly fails to ensure quality issues such as availability of teachers, school infrastructure and maintenance as well as completion rates (Barrett, Citation2011; Lay, Citation2012). Mekonen (Citation2010) criticises not targeting a high pupil–teacher ratio, describing the alarming rate of 25:1 globally, 43:1 in sub-Saharan Africa, 69:1 in Chad and 83:1 in Congo.

Health plays an important role within the MDGs framework, where three of the eight goals directly (MDG 4–6), and several other goals more indirectly, relate to health. James (Citation2006) believes, however, that the MDGs focus on only three aspects of health (maternal mortality, child mortality and specific infectious diseases) is too limited and an overarching goal of ‘freedom from illness’ is missing. Others emphasise the need to integrate trained health care providers and the importance of building effective health systems into the list of MDG targets (Haines & Cassels, Citation2004; Keyzer & Van Wesenbeeck, Citation2006). Several health issues are found to be underrecognised, such as non-communicable diseases (Magrath, Citation2009), mental health (Miranda & Patel, Citation2007) and issues faced by people living with disabilities (Wolbring, Citation2011). Several authors highlight the fact that targets for reproductive health were absent before 2007 and are still insufficient in MDG 5 (Basu, Citation2005; Bernstein, Citation2005; Dixon-Mueller & Germain, Citation2007). Omissions in MDG 5 are the issues of abortion (Basu, Citation2005), a ‘fertility regulation indicator’ (Dixon-Mueller & Germain, Citation2007) and the ‘availability and use of obstetric services’ (Langford, Citation2010).

MDG 7 prompted authors to argue that the goal places too ‘little emphasis on environmental issues’, in particular, climate change (McMichael & Butler, Citation2004). Some suggest that Target 7.C – access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation – overlooks local challenges, including infrastructure, distance, security, costs, contamination as well as a basic understanding of hygiene and sanitation (Dar & Khan, Citation2011; James, Citation2006). Others call Target 7.D – improving lives of at least 100 million slum residents – too moderate, addressing only 7–9% of expected slum residents by 2020 (Di Muzio, Citation2008; Langford, Citation2010).

Goal 8, the only one focusing on commitments by developed countries, is criticised by several authors as having the ‘least explicit targets’, lacking ‘quantitative’ and ‘time bound’ benchmarks (Davis, Citation2011; Fukuda-Parr, Citation2006; Gore, Citation2010). Fukuda-Parr (Citation2006) believes that the emphasis on ‘resource transfer through Official Development Assistance’ (ODA) inhibits the ‘empowerment of developing countries’. making essential drugs and technology available (Target 8.E/F) is not enough, according to James (Citation2006), because it fails to grasp the importance of information and knowledge about correct usage.

Authors also critically look at the time frame set by the MDGs, stating that it is not always clearly specified within which time frame the goals should be achieved (Poku & Whitman, Citation2011). Keyzer and Van Wesenbeeck (Citation2006) believe that 15 years is too short to address development and see progress. Others argue that intermediate milestones and targets would have helped to maintain focus and achieve the goals (Clemens et al., Citation2007; Robinson, Citation2005).

4. Limitations in the MDG implementation and enforcement

Availability and reliability of data are the most often reported challenges with regards to implementation of MDGs and subsequently in the interpretation of progress reports (Dar & Khan, Citation2011; Easterly, Citation2009; Sachs, Citation2012). For AbouZahr and Boerma (Citation2010), the global MDG targets are based on ‘little evidence of feasibility in low-income countries’, and Attaran (Citation2005) explains further that the health-related baselines from 1990 are often based on unreliable household surveys with no birth and death registries, health records or health statistics. For the educational MDG 2, Johnston (Citation2011) found that data on school completion are difficult to obtain because enrolment data are usually collected at the beginning of the academic year, ignoring attendance and drop outs. Quantitative MDG targets also rely on epidemiological and monitoring tools that many countries lack, and even if available, data are not necessarily comparable across countries because of different compilation methodologies or definitions (Poku & Whitman, Citation2011). Progress reports, therefore, are difficult to interpret because their calculations are based on assumptions and poor quality data (Reddy & Heuty, Citation2008). Additionally, unreliable data can also lead to miscalculated cost estimation with important financial consequences for donor and recipient countries (Saith, Citation2006).

Authors also criticise the lack of clear guidance on policy changes or how the goals ought to be achieved (Fukuda-Parr, Citation2006; Gil-Gonzalez, Ruiz-Cantero & Alvarez-Dardet, Citation2009). For Oya (Citation2011), there is not enough guidance to achieve the expected but unrealistic outcomes, which might create pessimism and cynicism in poor countries.

Another concern is the important influence of the MDG framework on data processing, interpretation and research. Institutionalised targets can also lead to misused and manipulated statistics, and a strong financial influence risks narrowing priorities of academic research (Saith, Citation2006). The author adds that this increased need to compete for funds forces organisations (such as non-governmental, civil society and international development organisations) to fall in line with the goals even if this might not always be in the best interest of the institution nor of the beneficiaries.

Finally, authors criticise the MDG framework for promoting ‘quick-fix’ solutions and short-term planning instead of sustainable global management goals and structural changes (Bond, Citation2006; Van Norren, Citation2012). The strong incentives to show a quick impact lead to parallel and uncoordinated programmes that encourage picking of ‘low-hanging fruits’ instead of long-term investments (Lay, Citation2012; Maxwell, Citation2003; Richard et al., Citation2011). It encourages ‘vertical organization of planning, financing, procurement, delivery, monitoring, and reporting’ with no consideration of national needs or broader aspects of the health system (Waage et al., Citation2010).

Discussion

Since the establishment of the MDGs, there has been significant progress in health and well-being in several regions of the globe. Broad consensus suggests that the MDGs have had a positive role in this achievement. A survey of more than 100 Southern NGOs from 27 countries showed strong support of the MDGs (75% of respondents considered the MDGs to be ‘a good thing’) (Pollard, Sumner, Polato-Lopes, & de Mauroy, Citation2011). At the same time, however, both practitioners and policy-makers recognise some limitations within the MDG framework. Most of these critiques do not intend to suggest having no framework altogether but are rather ‘critical friends’, aiming to identify what can be improved (Unterhalter, Citation2012). In this same vein, the purpose of this literature review is to describe the broad variety of limitations found in the literature and, thus, identify opportunities for discussion and improvements for the post-2015 agenda.

Only 15% of MDG-related publications expressed concerns with the MDGs, and only one-third of these discussed intrinsic limitations. After numerous international summits, the consensus that resulted in the Millennium Declaration of 2000 subsequently led to broad positive acceptance of the MDGs. Initially, most authors appeared to look optimistically towards the initiative, and they were more likely to publish about implementation and progress of the MDGs. However, more recently, relatively greater criticism and reflection appeared to develop.

These MDG criticisms were mixed, without clear consensus. What often appeared as a limitation to some was seen as a strength by others. Some authors consider the MDGs to be too ambitious and unrealistic, while others believe they are too narrow to capture the major issues of development. Although the MDGs were originally meant as long-term normative objectives, authors describe their potential of becoming ‘planned targets’ encouraging quick-fix solutions (Fukuda-Parr, Greenstein, & Stewart, Citation2013).

One of the most commonly cited concerns is the manner in which the MDGs were developed. Authors describe the creation of the MDGs as being led by a few country actors who decided on the choice of goals with very little involvement from developing countries. In contrast, the World Health Organization is currently engaging member states, civil society, private sector and academia to help with the post-2015 development agenda (UN Task Team, Citation2013). However, ‘too many cooks in the kitchen’ may make consensus on common goals difficult, according to Vandemoortele, architect of the MDGs and UN advisor for the agenda post-2015 (Jones, Citation2013). Finding the balance between the complexity of development and staying concise and practicable at the same time will be a major challenge for future goals.

Structural concerns with the MDGs include that they are too simplistic, unachievable and have too much of a managerial approach while not identifying who is accountable for achieving them. Furthermore, reducing development objectives to a list of eight artificially separated goals risks ignoring their interconnectedness and subsequently reinforcing a vertical nature in programmes, policies, research and funding. In contrast, Sachs (Citation2012) believes that ‘eight simple goals that fit well on one poster’ are a key to the success of the MDGs. Others have pointed out that synergism between sectors has been made possible through the MDGs; for example, a strong focus on health – in particular, malaria – has helped advance education and economic growth of countries (Berkley et al., Citation2013).

Authors expressed concerns that establishing the MDGs as shared worldwide goals overlooked individual national and regional needs and excluded several notable development issues such as limited governance capabilities. Furthermore, progress is measured in mostly national aggregated data that prevent a detailed understanding of regional progress and obscure within-country disparities. New methods are now being developed to measure the ‘pace of progress’ rather than specific end-targets that are difficult to reach for some countries (Fukuda-Parr et al., Citation2013).

With regard to the content of the MDGs, some authors argue that the limited focus on poverty, and not on reduction of inequity and inequalities, is seen as a major omission of the MDG framework. In fact, along with progress, the issue of equity appears to be receiving increasing attention from the international community. The UN Task Team on the post-2015 UN Development Agenda has acknowledged that major points mentioned in the literature, such as inequalities, social exclusion, biodiversity, and reproductive health, are addressed insufficiently by the MDGs (UN Task Team, Citation2012). In their recommendations the task team included human rights, equality and sustainability as core values of future goals.

Various authors cite concerns over specific MDG targets and indicators. The arbitrary choice of a poverty line is criticised as well as the general use of average and proportions, making it harder to achieve measurable progress in worst-off countries. Despite MDG revisions in 2007, reproductive health is still not adequately included, and MDG 7 does not adequately address increasing environmental challenges.

As might be expected with any examination of a complex issue, there are limitations to this literature review. Given the sheer volume of documents on the topic of MDGs, the search was limited to English-language articles. This and the exclusion of unpublished and non-peer-reviewed reports might ignore important challenges the MDG framework faced under particular social, cultural and political circumstances. This review focused on less-examined intrinsic factors of the framework that may explain uneven progress in MDGs and across countries. This may underplay the role of extrinsic factors like national policies and the recent global financial and food crises. Lastly, this study did not attempt to systematically assess the relative levels of consensus or validity of the arguments published in the literature.

Conclusion

Reasons for slow or limited progress in achieving the MDGs are complex, and with a global recession and inherent challenges with all goals, any limitations in the MDG framework itself cannot be entirely responsible for shortfalls in progress. Nevertheless, the literature identifies a range of important concerns, including limitations in MDG formulation process, structure, content and implementation.

By recognising, and deliberating on, the range of identified intrinsic limitations of MDGs, the next generation of global development goals might address these limitations and potentially have even greater positive impact on the health and well-being of people worldwide.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Roy Ahn, Sanj Karat and David McCoy for reviewing early drafts and providing many useful suggestions. The views presented in this article are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of their institutions. Sridhar Venkatapuram's participation in research is supported through Wellcome Trust [grant number 096986/Z/11/Z].

References

- AbouZahr, C., & Boerma, T. (2010). Five years to go and counting: Progress towards the millennium development goals. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 88, 324. 1–14.

- Amin, S. (2006). The millennium development goals – A critique from the South. Monthly Review-an Independent Socialist Magazine, 57(10). Retrieved from http://monthlyreview.org

- Attaran, A. (2005). An immeasurable crisis? A criticism of the millennium development goals and why they cannot be measured. Plos Medicine, 2, 955–961. doi:10.1317/journal.pmed.0023018

- Barnes, A., & Brown, G. W. (2011). The idea of partnership within the millennium development goals: Context, instrumentality and the normative demands of partnership. Third World Quarterly, 32, 165–180. doi:10.1080/01436597.2011.543821

- Barrett, A. M. (2011). A millennium learning goal for education post-2015: A question of outcomes or processes. Comparative Education, 47(1), 119–133. doi:10.1080/03050068.2011.541682

- Basu, A. M. (2005). The millennium development goals minus reproductive health: An unfortunate, but not disastrous, omission. Studies in Family Planning, 36(2), 132–134. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2005.00051.x

- Berkley, S., Chan, M., Dybul, M.Hansen, K., Lake A., Osotimehin B., & Sidibé, M. (2013). A healthy perspective: The post-2015 development agenda. Lancet, 381, 1076–1077. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60722-9

- Bernstein, S. (2005). The changing discourse on population and development: Toward a new political demography. Studies in Family Planning, 36(2), 127–132. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2005.00050.x

- Bond, P. (2006). Global governance campaigning and MDGs: From top-down to bottom-up anti-poverty work. Third World Quarterly, 27, 339–354. doi:10.1080/01436590500432622

- Brikci, N., & Holder, A. (2011). MDG4-hope or despair for Africa? Revista De Economia Mundial, 27, 71–94. Retrieved from http://www.sem-wes.org

- Cecchini, S., & Notti, F. (2011). Millennium development goals and human rights: Faraway, so close? Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 12(1), 121–133. doi:10.1080/19452829.2011.541793

- Clemens, M. A., Kenny, C. J., & Moss, T. J. (2007). The trouble with the MDGs: Confronting expectations of aid and development success. World Development, 35, 735–751. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2006.08.003

- Curtis, D., & Poon, Y. (2009). Why a managerialist pursuit will not necessarily lead to achievement of MDGs. Development in Practice, 19, 837–848. Retrieved from http://www.developmentinpractice.org

- Dar, O. A., & Khan, M. S. (2011). Millennium development goals and the water target: Details, definitions and debate. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 16, 540–544. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02736.x

- Davis, T. W. D. (2011). The MDGs and the incomplete relationship between development and foreign aid. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 16, 562–578. doi:10.1080/13547860.2011.610888

- Di Muzio, T. (2008). Governing global slums: The biopolitics of target 11. Global Governance, 14, 305–326. Retrieved from https://www.rienner.com/title

- Dixon-Mueller, R., & Germain, A. (2007). Fertility regulation and reproductive health in the millennium development goals: The search for a perfect indicator. American Journal of Public Health, 97(1), 45–51. doi:10.2105/ajph.2005.068056

- Easterly, W. (2009). How the millennium development goals are unfair to Africa. [Article]. World Development, 37(1), 26–35. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.02.009

- Edward, P. (2006). The ethical poverty line: T moral quantification of absolute poverty. Third World Quarterly, 27, 377–393. doi:10.1080/01436590500432739

- Eyben, R. (2006). The road not taken: International aid's choice of Copenhagen over Beijing. Third World Quarterly, 27, 595–608. doi:10.1080/01436590600720793

- Fukuda-Parr, S. (2006). Millennium development goal 8: Indicators for international human rights obligations? Human Rights Quarterly, 28, 966–997. doi:10.1353/hrq.2006.0046

- Fukuda-Parr, S. (2010). Reducing inequality – The missing MDG: A content review of PRSPs and bilateral donor policy statements. Ids Bulletin-Institute of Development Studies, 41(1), 26–35. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.2010.00100.x

- Fukuda-Parr, S., Greenstein, J., & Stewart, D. (2013). How should MDG success and failure be judged: Faster progress or achieving the targets? World Development, 41, 19–30. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.06.014

- Gil-Gonzalez, D., Ruiz-Cantero, M. T., & Alvarez-Dardet, C. (2009). How political epidemiology research can address why the millennium development goals have not been achieved: Developing a research agenda. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 63, 278–280. doi:10.1136/jech.2008.082347

- Gore, C. (2010). The MDG paradigm, productive capacities and the future of poverty reduction. Ids Bulletin-Institute of Development Studies, 41(1), 70–79. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.2010.00106.x

- Gwatkin, D. R. (2005). How much would poor people gain from faster progress towards the millennium development goals for health? Lancet, 365, 813–817.doi:10.1016/s01406736(05)71008-4

- Haines, A., & Cassels, A. (2004). Can the millennium development goals be attained? British Medical Journal, 329, 994–397. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7462.394

- Hayman, R. (2007). Are the MDGs enough? Donor perspectives and recipient visions of education and poverty reduction in Rwanda. International Journal of Educational Development, 27, 371–382. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2006.10.002

- Hill, P. S., Mansoor, G. F., & Claudio, F. (2010). Conflict in least-developed countries: Challenging the millennium development goals. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 88, 562. doi:10.2471/blt.09.071365

- Hulme, D. (2010). Lessons from the making of the MDGs: Human development meets results-based management in an unfair world. Ids Bulletin-Institute of Development Studies, 41(1), 15–25. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.2010.00099.x

- James, J. (2006). Misguided investments in meeting millennium development goals: A reconsideration using ends-based targets. Third World Quarterly, 27, 453–458. doi:10.1080/01436590600587960

- Johnston, D. (2011). Shooting for the wrong target? A reassessment of the international education goals for sub-Saharan Africa. Revista De Economia Mundial, 27, 95–116. Retrieved from http://www.sem-wes.org

- Jones, R. (2013). ‘Too many cooks in the kitchen,’ warns MDG co-architect. Devex. Retrieved from https://www.devex.com/en/news/too-many-cooks-in-the-kitchen-warns-mdg-co-architect/80799

- Kabeer, N. (2005). The Beijing platform for action and the millennium development goals: Different processes, different outcomes. Baku: United Nations Division for the Advancement of Women. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/egm/bpfamd2005/experts-papers/EGM-BPFA-MD-MDG-2005-EP.11.pdf

- Keyzer, M., & Van Wesenbeeck, L. (2006). The millennium development goals, how realistic are they? Economist-Netherlands, 154, 443–466. doi:10.1007/s10645-006-9019-9

- Langford, M. (2010). A poverty of rights: Six ways to fix the MDGs. Ids Bulletin-Institute of Development Studies, 41(1), 83–91. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.2010.00108.x

- Lay, J. (2012). Millennium development goal achievements and policies in education and health: What has been learnt? Development Policy Review, 30(1), 67–85. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7679.2012.00560.x

- Lewin, K. M. (2005). Planning post-primary education: Taking targets to task. International Journal of Educational Development, 25, 408–422. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2005.04.004

- Magrath, I. (2009). Please redress the balance of millennium development goals. British Medical Journal, 338, b2770. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2770

- Maxwell, S. (2003). Heaven or hubris: Reflections on the new ‘new poverty agenda’. Development Policy Review, 21(1), 5–25. doi:10.1111/1467-7679.00196

- McMichael, A. J., & Butler, C. D. (2004). Climate change, health, and development goals. Lancet, 364, 2004–2006. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17529-6

- Mekonen, Y. (2010). A ‘2015’ agenda for Africa: Development from a human perspective. Ids Bulletin-Institute of Development Studies, 41(1), 45–47. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.2010.00102.x

- Miranda, J. J., & Patel, V. (2007). Mental health in the millennium development goals: Authors' reply. Plos Medicine, 4(1), e57. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040057

- Mishra, U. S. (2004). Millennium development goals: Whose goals and for whom? British Medical Journal, 329, 742. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7468.742-b

- Mohindra, K. S., & Nikiema, B. (2010). Women's health in developing countries: Beyond an investment? International Journal of Health Services, 40, 443–467. doi:10.2190/HS.40.3.i

- Molyneux, D. H. (2008). Combating the ‘other diseases’ of MDG 6: Changing the paradigm to achieve equity and poverty reduction? Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 102, 509–519. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.02.024

- Overseas Development Institute. (2010). Millennium development goals report card: Measuring progress across countries. London: Author. Retrieved from http://www.odi.org.uk/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/6172.pdf

- Oya, C. (2011). Africa and the millennium development goals (MDGs): What's right, what's wrong and what's missing. Revista De Economia Mundial, 27, 19–33. Retrieved from http://www.sem-wes.or

- Pogge, T. (2004). The first United Nations millennium development goal: A cause for celebration? Journal of Human Development, 5, 377–397. doi:10.1080/1464988042000277251

- Pogge, T. (2010). Politics as usual: What lies behind the pro-poor rhetoric (p. 62). Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Poku, N. K., & Whitman, J. (2011). The millennium development goals and development after 2015. Third World Quarterly, 32, 181–198. doi:10.1080/01436597.2011.543823

- Pollard, A., Sumner, A., Polato-Lopes, M., & de Mauroy, A. (2011). 100 voices: Southern NGO perspectives on the millennium development goals and beyond. Ids Bulletin-Institute of Development Studies, 42(5), 120–123. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.2011.00263.x

- Reddy, S., & Heuty, A. (2008). Global development goals: The folly of technocratic pretensions. Development Policy Review, 26(1), 5–28. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7679.2008.00396.x

- Reidpath, D. D., Morel, C. M., Mecaskey, J. W., & Allotey, P. (2009). The millennium development goals fail poor children: The case for equity-adjusted measures. PLoS Medicine, 6(4), e1000062. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000062

- Richard, F., Hercot, D., Ouedraogo, C., Delvaux, T., Samake, S., van Olmen, J., … Vandemoortele, J. (2011). Sub-Saharan Africa and the health MDGs: The need to move beyond the ‘quick impact’ model. Reproductive Health Matters, 19(38), 42–55. doi:10.1016/s0968-8080(11)38579-5

- Robinson, C. (2005). Promoting literacy: What is the record of education for all? International Journal of Educational Development, 25, 436–444. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2005.04.006

- Sachs, J. D. (2012). From millennium development goals to sustainable development goals. Lancet, 379, 2206–2211. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60685-0

- Saith, A. (2006). From universal values to millennium development goals: Lost in translation. Development and Change, 37, 1167–1199. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.2006.00518.x

- Saith, A. (2007). Goals set for the poor, goalposts set by the rich. International Institute of Asian Studies Newsletter, 45, 12–13. Retrieved from http://www.iias.nl

- Subrahmanian, R. (2005). Gender equality in education: Definitions and measurements. International Journal of Educational Development, 25, 395–407. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2005.04.003

- Tarabini, A. (2010). Education and poverty in the global development agenda: Emergence, evolution and consolidation. International Journal of Educational Development, 30, 204–212. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2009.04.009

- UN. (2010). Keeping the promise: A forward-looking review to promote an agreed action agenda to achieve the millennium development goals by 2015. Report of the Secretary-General, UN, General Assembly 64th Session. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/reports.shtml

- UN. (2012). The millennium development goals report 2012 ( Vol. ISBN 978-92-1-101244-6). Retrieved from http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/reports.shtml

- UN Task Team. (2012). Realizing the future we want: A report to the Secretary General. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/untaskteam_undf/report.shtml

- UN Task Team for the Global Thematic Consultation on Health in the post 2015 development agenda. (2013). What do people want for health in the post-2015 agenda? Lancet, 381, 1441–1443. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60765-5

- Unterhalter, E. (2012). Trade-off, comparative evaluation and global obligation: Reflections on the poverty, gender and education millennium development goals. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 13, 335–351. doi:10.1080/19452829.2012.681296

- Van Ginneken, W. (2011). Social protection, the millennium development goals and human rights. Ids Bulletin-Institute of Development Studies, 42(6), 111–117. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.2011.00282.x

- Van Norren, D. E. (2012). The wheel of development: The millennium development goals as a communication and development tool. Third World Quarterly, 33, 825–836. doi:10.1080/01436597.2012.684499

- Vandemoortele, J. (2011). If not the millennium development goals, then what? Third World Quarterly, 32(1), 9–25. doi:10.1080/01436597.2011.543809

- Waage, J., Banerji, R., Campbell, O., Chirwa, E., Collender, G., Dieltiens, V., & Unterhalter, E. (2010). The millennium development goals: A cross-sectoral analysis and principles for goal setting after 2015. Lancet, 376, 991–1023. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61196-8

- Wolbring, G. (2011). People with disabilities and social determinants of health discourses. Canadian Journal of Public Health-Revue Canadienne De Sante Publique, 102, 317–319. Retrieved from http://www.cpha.ca.

- Ziai, A. (2011). The millennium development goals: Back to the future? Third World Quarterly, 32(1), 27–43. doi:10.1080/01436597.2011.543811