Abstract

Participatory mapping was undertaken with single-sex groups of grade 5 and grade 8–9 children in KwaZulu-Natal. Relative to grade 5 students, wide gender divergence in access to the public sphere was found at grade 8–9. With puberty, girls' worlds shrink, while boys' expand. At grade 5, female-defined community areas were equal or larger in size than those of males. Community area mapped by urban grade 8–9 girls, however, was only one-third that of male classmates and two-fifths that of grade 5 girls. Conversely, community area mapped by grade 8–9 boys was twice that of grade 5 boys. Similar differences emerged in the rural site. No female group rated a single community space as more than ‘somewhat safe’. Although curtailed spatial access is intended to protect girls, grade 8–9 girls reported most places in their small navigable areas as very unsafe. Expanded geographies of grade 8–9 boys contained a mix of safe and unsafe places. Reducing girls' access to the public sphere does not increase their perceived safety, but may instead limit their access to opportunities for human development. The findings emphasise the need for better violence prevention programming for very young adolescents.

Introduction

Adolescents in post-apartheid South Africa ostensibly face new prospects. Nevertheless, their daily activities are overshadowed by social, economic and physical risks that limit their access to the public sphere and hence to opportunities. In addition to threats from HIV and AIDS, systemic structural inequality and high rates of unemployment, young women and men account for a large proportion of the victims of widespread violence and crime. Although political violence has declined since the democratic transition, South Africa experiences high rates of violent and property crimes as well as domestic abuse and intimate partner violence (Jewkes, Citation2013; Jewkes, Dunkle, Nduna, & Shai, Citation2010; Jewkes, Sikweyiya, Morrell, & Dunkle, Citation2009; Naude, Prinsloo, & Ladikos, Citation2006; Seedat, Van Niekerk, Jewkes, Suffla, & Ratele, Citation2009).

Worldwide, adolescence is the age of highest risk for intentional injury (Lozano, Naghavi, Foreman, AlMazroa, & Memish, Citation2013). According to South Africa's National Injury Mortality Surveillance System, the leading cause of death among 10–19-year-olds in 2008 (the most recent year available) was violence (36%), followed by transport accidents (30%), non-transport accidents (15%) and suicide (13%), with the remaining causes undetermined (6%) (MRC-UNISA, Citation2010). This is one of the few countries in sub-Saharan Africa where violence takes a higher toll on adolescents than does transport accidents. Adolescent concerns about the threat of violence are therefore real and borne out by such statistics. Despite the prevalence of violence and the widespread media attention to it, the relationship between community violence and adolescent access to the public sphere has not been systematically examined in South Africa.

In the USA, neighbourhood violence is linked to earlier sexual initiation (Aneshensel & Sucoff, Citation1996; Choby, Dolcini, Catania, Boyer, & Harper, Citation2012; Kim, Citation2010; Upchurch, Aneshensel, Sucoff, & Levy-Storms, Citation1999), poorer adolescent mental health (Dupéré, Leventhal, & Vitaro, Citation2012; Shields et al., Citation2010; Zona & Milan, Citation2011), higher rates of obesity (Whitaker, Citation2010) and curtailed ability – especially of girls – to conduct basic daily activities: to venture outside the home, safely attend and return from school, stay after school, and play or participate in programmes (Bennett et al., Citation2007; Davison & Jago, Citation2009; Gomez, Johnson, Selva, & Sallis, Citation2004; Kimm et al., Citation2002). Parents in poor, disorganised neighbourhoods tend to exert more control over adolescents than parents in better off, safer neighbourhoods in an attempt to protect their children from harm and girls are much more tightly regulated than boys (Galambos, Berenbaum, & McHale, Citation2009; Hilbrecht, Zuzanek, & Mannell, Citation2008). Attempts to increase girls' safety include requiring them to stay close to home and to play only in ‘safe’ places, thus limiting their movements in the community.

There is little evidence from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) on how crime and interpersonal violence create unsafe conditions that may reduce access to social capital and skill-building opportunities, and, in turn, limit long-term potential for human development. In particular, it is unclear how perceptions of violence – formed through knowledge or witness of violent events, stories and expectations – influence and possibly limit the choices and capabilities of adolescents by sex and age.

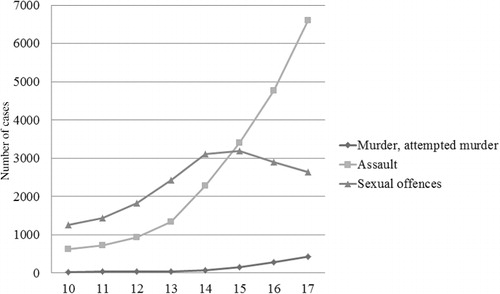

The South African police service (SAPS) annual report 2011/2012 includes statistics on crimes committed against children. While 0–17-year-olds comprise 35% of the population, this group constituted 7% of murder or attempted murder victims, 8% of non-sexual assault victims and 38% of sexual offence victims. Crimes reported against children by victim age () show that victimisation of all types rises with age. Both sexual offences and non-sexual assault increase rapidly after age 10, with reported sexual offences among this age group peaking at ages 14–15. While the SAPS data for child victims are not disaggregated by sex, national crime statistics for adults indicate that women represent 16% of murder or attempted murder victims, 39% of non-sexual assault victims and 81% of sexual offence victims.

Despite this evidence, there is virtually no information on how adolescents themselves perceive violence. Given the rapid social, physical, emotional and sexual changes that occur during this life stage, we hypothesise that variations by age and sex are likely. That such maturation occurs earlier for girls than boys (and perhaps earlier than for previous generations of girls) lends a further possible age–sex dimension to the question. Of particular note is the 10–14-year-old age group, when puberty occurs and gender differences in physical and sexual characteristics manifest (Chong, Hallman, & Brady, Citation2006).

Adolescent geographies

Adolescent geographies can be conceptualised as overlapping ‘action spaces’ through which boys and girls move in their daily lives, exposing them to differing levels of social opportunity and risk. Cummins, Curtis, Diez-Roux, and Macintyre (Citation2007) articulated relational theories that motivate this analysis, in particular the actor network theory as described by Latour (Citation1996) and Murdoch (Citation1998). This theory hypothesises that activities are organised within geographic spaces characterised not only by physical distance but also by the relational proximity and social distance of people of different ranks and hierarchies. This social distance continues to strongly permeate daily life and social relationships in South Africa.

The 2005 South African National Youth victimisation Survey revealed that adolescents faced high rates of violence, with more than 40% having been the victim of a crime in the previous year (Leoschut & Burton, Citation2006). The bulk of homicides and violent injuries are borne by young males, while young females experience exceptionally high rates of rape and sexual assault (Jewkes et al., Citation2010; Seedat et al., Citation2009; Townsend et al., Citation2011). These circumstances are strongly reinforced by gender hierarchies, socially pervasive forms of masculinity and exploitative power dynamics within social institutions (Moffett, Citation2006; Morrell, Citation1998; Seedat et al., Citation2009). Further, the vast majority of perpetrators of crimes committed against and witnessed by adolescents are individuals who reside in the community and are personally known by the adolescent (Jewkes & Abrahams, Citation2002). Often, these perpetrators are the very persons charged with protecting children and adolescents: neighbours, educators and family members (Leoschut & Burton, Citation2006). Thus, adolescents' safety is eroded in familiar private and public spaces by persons whom they should in theory be able to trust.

With the Human Rights Watch (Citation2001) report on sexual violence against girls in South African schools, school-based sexual violence became a topic of research in LMICs. Subsequent studies often focused on girls as victims and boys and/or teachers as perpetrators, with singular concerns about HIV infection, ignoring more widespread patterns and consequences of violence outside of school (see Leach & Humphreys, Citation2007; Mirsky, Citation2003). Much of this research, with the important exceptions of Brookes and Higson-Smith (Citation2004); CIET Africa & Greater Johannesburg Southern Metropolitan Local Council (Citation2000); Jewkes, Levin, Mbananga, and Bradshaw (Citation2002); and Richter, Dawes, and Higson-Smith (Citation2004), failed to explore the wider patterns of community-level or inter-relational violence from the perspective of adolescents, nor did it discuss the effects on children of observing violence (Knerr, Gardner, & Cluver, Citation2011). The violence against children surveys (VACS) led by UNICEF and the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) have demonstrated the high prevalence of violence (sexual, physical and emotional) experienced by girls and boys aged 13–24 throughout sub-Saharan Africa (Swaziland, Kenya, Tanzania and Zimbabwe; CDC, Citation2013). The mapping study we describe below seeks to identify gender- and age-specific variations and deficits in the geographies of safety from the perspective of adolescents.

Methods

Participatory mapping

Published research on adolescents and violence in LMICs consists primarily of police victimisation reports, cause-of-death studies or non-fatal injury surveys. While these are crucial quantitative measures, they fail to lend voice to adolescent perceptions of their community and to locate such perceptions within street-by-street (or field-by-field) geographies. Knowledge of children's perceptions about safety is essential, given that much of the violence experienced by young people is often hidden and largely unreported (Pinheiro, Citation2006). Participatory mapping has been used widely since the 1960s by anthropologists and international development researchers to involve marginalised groups in identifying local problems, often with the goal of informing policy decisions or mobilising grassroots action (Chambers, Citation1994; Creswell, Citation1998; Mukherjee, Citation1993). With increasing attention to adolescent girls within international health research, participatory mapping has been used to gain an understanding of places in the community that are accessible to girls. Following work by Stromquist (Citation1996) on the social cartography of gendered spaces, and by Mitchell, Reid-Walsh, Blaeser, and Smith (Citation1998) on feminist mapping, a variety of girl empowerment initiatives have used this method, often as a way for researchers to interact with girls and their guardians upon first entering a community.

Most adolescent mapping studies involve only a single sex (girls) and do not disaggregate by age, thus limiting the ability to compare geographies by gender and age. Exceptions include the study by Lary, Maman, Katebalila, and Mbwambo (Citation2004) of single-sex groups of 16–24-year-olds in Dar es Salaam; Mitchell, Moletsane, Stuart, Buthelezi, and De Lange (Citation2005) gender-disaggregated study of 12–13-year-old school children in Swaziland; research by Power, Langhaug, and Cowan (Citation2007) on single-sex groups of grade 9–11 students in Zimbabwe; and Winton's (Citation2005) research in Guatemala with mixed-sex groups of young women and men aged 9–23. These studies made enlightening sex-specific observations, but none of the designs permitted analysis of sex-specific findings by human development stage. As far as we know, ours is the only study that examines sex- and age-specific aspects of community safety and violence as perceived by adolescents themselves.

The KwaZulu-Natal study

To explore the relationship between perceived violence and adolescent access to the public sphere by sex, school grade and urban–rural residence, the population council collaborated in 2004–2005 with the crime reduction in schools project (CRISP) trust, UNICEF and the KwaZulu-Natal department of education to conduct participatory exercises with school children in urban and rural communities in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. The study was conducted in one urban township and one rural community. Students in one primary and one secondary school in each area participated, resulting in four groups per community: grade 5 girls, grade 5 boys, grade 8–9 girls and grade 8–9 boys. There was an average of 17 students per group (range 13–22 students). The mean age for grade 5 students was 11 years (range 9–13 years); the mean age for grade 8–9 students was 14.5 years (range 13–17 years). Grade 5 and grades 8–9 were chosen to compare the perceptions of adolescents at two different stages of development: pre-adolescence and early-to-mid-adolescence. Comparing students at these grade levels is also salient because South African grade 5 children attend upper primary, and grade 8–9 children are in the early stage of secondary and thus exposed to different school environments and peers, as well as varying distances and commutes to school.

With the guidance of trained young adult Zulu- and English-speaking bilingual facilitators, each group was given a blank piece of paper of size four by five feet, coloured markers, coloured construction paper and tape. They were asked to draw the area that represented their community and to indicate places in the community and rate each in terms of its safety or lack of safety, using the following categories: extremely safe, very safe, somewhat safe, sometimes safe/sometimes unsafe, somewhat unsafe, very unsafe or extremely unsafe. The research team did not define criteria for the various categories of safety; the groups were allowed to determine these themselves in the course of their discussion. Groups also developed their own symbols for depicting various places on their maps.

Ethical procedures were followed in the research, including informed consent from school principals and from teachers and guardians of children in participating classrooms, as well as informed assent of all child participants (aged 9–17 years) and informed consent from emancipated minors. CRISP Trust retained all informed consent documents in locked file cabinets in their offices in Durban. A social worker and/or school guidance counsellor was present during each group session. Individual participant names were not collected during the research, so the risk of linking information collected with any individual is extremely low. School, road, landmark and community names were removed from any materials disseminated outside the immediate study neighbourhood.

With maps drawn freehand and the place symbols defined differently by each participant group, direct comparison of the maps proved difficult. The contents of each map were therefore analysed by the research team by matching all features depicted on that map with those appearing on Google satellite images for each locality. Given this variation in the raw maps and to maintain the anonymity of the communities and schools where the research occurred, neither the raw maps nor the matched, place-labelled Google satellite images are presented here (the raw participant maps devoid of place names are available from the first author.) Instead, the boundaries of the physical area depicted by each participant group, determined by plotting mapped features on Google satellite images, are presented on unlabelled Google satellite images of each study site. Using the perimeters of each group's mapped area, the relative sizes of different groups' physical ‘community’ were assessed (the Google maps area calculator was used to determine area, available from www.draftlogic.com). In addition to compare varying perceptions of spaces within the same community, we contrast the sex–age safety ratings of places plotted by the four groups in each site.

CRISP Trust presented the results of this exercise to local authorities in each study community as a means to provide information about sex- and age-specific perceptions of safe and unsafe places. Meetings were held with school principals, educators, school boards and inter-sectoral community development forums to bring attention to the adolescents' findings and discuss proposed next steps.

Findings: depictions of community and safe and unsafe spaces

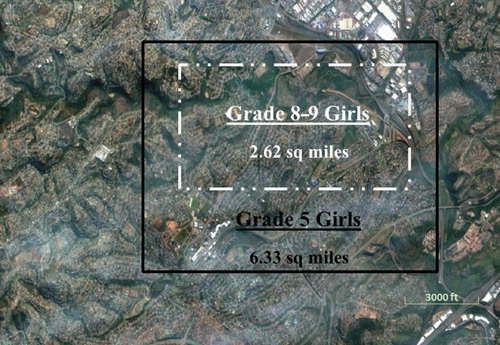

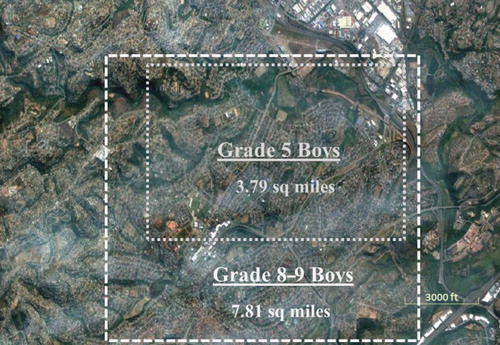

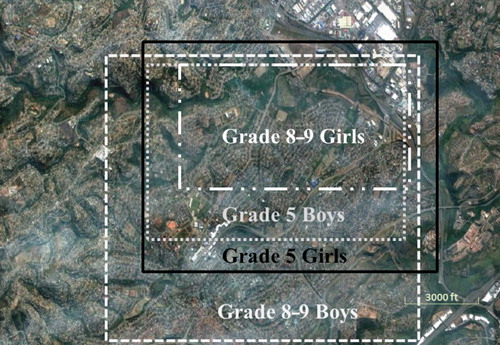

– present the spatial area defined as ‘community’ by each sex, grade and locality group. shows the geographic areas plotted by grade 5 and grade 8–9 urban girls. The size of the area mapped by the younger girls, 6.33 square miles, was substantially greater than that shown by older girls, 2.62 square miles. This disparity represents greatly contracted access to the public sphere with age: younger girls' area is 2.5 times larger than that of older girls. In , on the other hand, boundaries of this same community as defined by urban boys reveal growing male spatial access with age. The area represented by younger boys was 3.79 square miles, versus 7.81 square miles for older boys – a doubling with age.

shows all four group-mapped areas in the urban site. Grade 8–9 girls have by far the smallest geographic range, even less than that of boys and girls in grade 5. Interestingly, among the grade 5 students, girls represented their community as a much larger space than did boys (6.33 versus 3.79 square miles), indicating that girls' spaces do not start out smaller than boys', but become so after puberty. Comparing grade 8–9 girls with their male classmates reveals the substantial relative changes with age in accessible geographic area by sex: girls' self-defined area is only one-third that of boys' (2.62 versus 7.81 square miles).

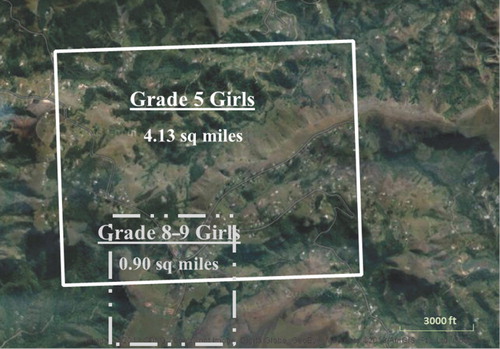

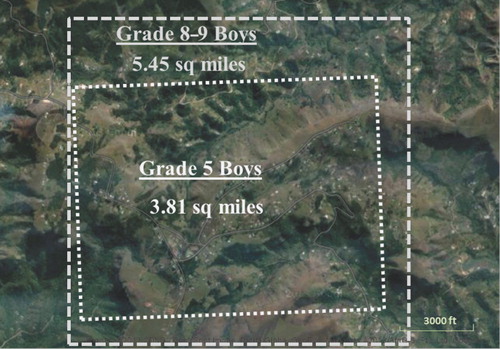

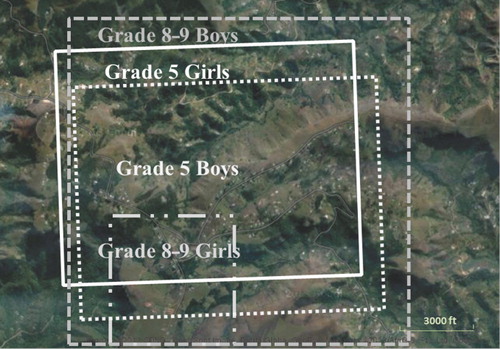

Community spaces for participants in the rural site are shown in –. The representation of girls' spaces () indicates that contraction of female spatial access with puberty is not solely an urban phenomenon. The area outlined here by younger girls was nearly five times that depicted by older girls (4.13 versus 0.90 square miles). Rural boys' geographies expand by nearly 50% between grade 5 and grades 8–9, from 3.81 square miles to 5.46 square miles. Comparing all four rural mapped areas (), by grade 8–9, girls' space is only 17% that of their grade 8–9 male classmates and only about one-fifth that of grade 5 girls or boys.

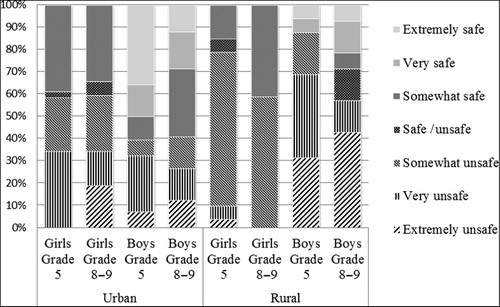

Within areas diagrammed by each group, spaces plotted by safety rating () reveal a distinctive gendered pattern in the urban area: younger and older girls rated about 60% of spaces as unsafe, whereas boys rated 40% of spaces as unsafe. Moreover, the degree of safety fell with age for both sexes but more so for girls. Contrary to expectation, rural participants rated a smaller overall percentage of mapped spaces as safe than did urban participants.

A notable finding is that none of the girls' groups rated any space in their community as more than ‘somewhat safe’, and every girls' group ranked at least 58% of accessible places as unsafe. Boys' ratings of community spaces showed much wider variation and generally contained more spaces perceived as safe. Boys' safety ratings differed by urban–rural residence, with rural boys describing a much higher percentage of places as unsafe.

Group-specific perceptions of various place types (not each individual place) are presented in and by sex and grade. In the urban site (), both sex and grade patterns are manifest. Boys reported a number of place types as very or extremely safe, whereas girls did not plot a single place in these two categories. Moreover, the number and variety of place types plotted decreases with age for girls, but increases with age for boys – in line with their respective shrinking and expanding geographic areas with age.

Table 1. Urban place type safety ratings by sex and grade.

Table 2. Rural place type safety ratings by sex and grade.

Younger and older urban girls reported the library, petrol station and police station as somewhat safe, while older boys described the library and police station as extremely safe (younger boys did not mention these places). Among grade 5 children, the primary school (where the mapping exercise took place) was given a mixed safety rating by girls, but was considered extremely safe by boys; analogously, grade 8–9 girls rated the secondary school (again, the research location) as very unsafe, whereas boys considered it very safe. Clinics were rated as somewhat safe by boys but had mixed safe/unsafe ratings among girls. Most private homes were viewed by girls as somewhat unsafe but by boys as very safe. Transport hubs (‘taxi ranks’) were considered very unsafe by every group except grade 8–9 boys, who viewed them as very safe. Urban grade 8–9 boys and girls each reported two extremely unsafe spaces on their maps (girls: bridge and shopping centre; boys: river and tavern). In the rural site (), virtually no place was described by any group as extremely or very safe. Here age differences were the most striking finding, with younger children perceiving more overall threats than older children, many of these being environmental hazards.

Discussion

Most research on community violence does not assess safety concerns by sex and age, thus limiting insights about the nature and life-course timing of perceived threats. Although adolescence is typically portrayed as a life stage offering expanded social, geographic and intellectual opportunities, safety concerns can derail this expansion (Leoschut & Burton, Citation2006). Accumulated over time, such narrowing has the potential to create lifelong deficits in capabilities.

This study found that the spatial geographies of adolescents in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa change significantly with age and diametrically so by sex. With age, girl areas shrink and even these extremely small geographies are reported as quite unsafe, whereas boy areas expand and contain a balance between safe and unsafe places. None of the girl groups rated any space in their communities as more than ‘somewhat safe’.

Girls in both age groups perceived more intimate bodily dangers than did boys, and systemically reported vulnerability to sexual assault and rape. Grade 5 urban girls repeated a common theme in speaking about unsafe spaces: people know about them, but no one does anything. As one participant commented about a well-known perpetrator in the area, ‘people close their doors when the man is raping someone’. A particular shop was classified by this group as somewhat safe only because ‘children are not raped there’. Such commentary reveals a clear need for better interventions to protect young adolescent girls against sexual violence.

Although grade 8–9 girls diagrammed much smaller geographic spheres than grade 5 girls, this contracted space did not result in fewer perceived threats. To the contrary, urban grade 8–9 girls perceived the majority of spaces and persons in their small spheres as unsafe, indicating a perception that the community itself poses a threat. ‘Anything can happen anytime’, members of the group reported. Participants remarked on what seemed an utter lack of community involvement, which may be a reaction to both the community's failure to provide protection and girls' lack of positive interactions with the community as a result of their confined geographies. Urban girls in both age groups conveyed a sense of helplessness and hopelessness in the community more broadly, without the ability to hold anyone specific accountable.

Younger boys described unsafe physical infrastructure and places lacking uniformed security personnel as unsafe, while older boys identified unsafe spaces as those marked by male-on-male violence, robbery, theft and drug use. Grade 5 rural boys were concerned with natural hazards – snakes, falling rocks, rivers that would flood, dangerous roads – whereas urban grade 5 boys identified social behaviours and violence, including alcohol/drug abuse and fighting, as concerns. Although the expanded geographies of grade 8–9 boys introduced new spheres of opportunity, they also resulted in exposure to violent crime and the potential for becoming participants in or victims of such crime – an indication of how cycles within communities are reproduced, transforming young men from witnesses or victims to possible perpetrators (see Jewkes et al., Citation2006; Seedat et al., Citation2009).

The gendered shifts observed between grade 5 and grade 8–9 students in navigable space and safety concerns are consistent with evidence on sex differences in human development and vulnerabilities at this crucial life stage. Girls are encouraged to become more empathetic and passive and are increasingly viewed as objects of sexual attention (Kaplan, Citation2004); boys, on the other hand, are expected to become more independent (especially from their mothers) and display physical strength and dominance (Aguirre & Guell, Citation2002). During this stage, girls become increasingly subjected to sexual and relational abuse, while boys are more likely to be bullied and experience physical aggression (Breinbauer & Maddaleno, Citation2005). Programmes and policies to increase the safety and protection of young people navigating the puberty transition are clearly needed.

Limitations

Small-scale participatory techniques like this one tailored to children and adolescents are emerging methods that have limitations. The study did not utilise police-reported crime statistics (in part because criminal violence is so severely underreported); student perceptions of safety and risk are obviously subjective. The school classroom itself, while crucial to the success of the project in this context where the majority of children attend school, was a difficult setting in which to conduct research because the time for assembling focus groups and for drawing and labelling the maps was limited and did not permit as much follow-up or in-depth discussion as we had hoped. Systematising and categorising findings across the set of maps was difficult because the parameters and dimensions of the community, as well as symbols used to depict local places, were defined by participants themselves and thus varied. In addition, this study was not longitudinal, so we cannot say that the future experiences of grade 5 participants will necessarily reflect those of their grade 8–9 contemporaries. The sample size for the study was also small.

Nevertheless, participatory mapping proved to be a low-cost, powerful tool for revealing the enormous variations by gender and age in navigable spaces and perceptions of safe/unsafe local places. Maps have political clout – they are a primary language of policy and politicians. As such, when presented to local leaders, maps have the potential to command attention and could bring together disparate actors responsible for the protection of young people, such as police, judicial institutions, health and social service agencies, school administrators and private security forces. This tool could readily be used as part of routine situation analyses for interventions aimed at violence prevention or response. It could be gainfully utilised within the fields of child protection, human rights, economic development and social justice.

Conclusions and recommendations

In contexts such as South Africa where education levels are high, safe spaces are fundamental to transforming education into functional and productive capabilities, defined by Sen (Citation2001) as ‘the ability – the substantive freedom – of people to lead the lives they have reason to value’ (p. 293). Such spaces are needed to provide adolescents with a secure and regularly accessible place to gather, learn and recreate (Brady, Citation2005). Although it is encouraging that attention to the potential importance of ‘safe spaces’ is starting to be explored for girls in LMICs (Austrian, Hewett, Jackson, & Soler-Hampejsek, Citation2012; Bandiera et al., Citation2012; Brady, Citation2005; Dunbar et al., Citation2010; Erulkar, Ferede, Girma, & Ambelu, Citation2013; Underwood & Schwandt, Citation2011), there are still no definitive programming guidelines, and boys' increasing exposure to violence and substance abuse at puberty has received little attention in LMICs (Patton, Citation2011).

An initial concrete step in this direction may include utilising existing spaces in the community that could function as reliably available age- and sex-specific safe places (Mensch, Bruce, & Greene, Citation1998). For example, using the spaces articulated as safe by adolescents in , a local library could be designated as a pre-adolescent female-only space at particular times of the day. Churches could be utilised on non-worship days for youth development activities tailored by age and sex. Boys' clubs could function with the leadership of local police.

As the only study we know of that examines sex- and age-specific aspects of community safety and violence as perceived by adolescents themselves, this research presents powerful findings that emphasise the need for more and better preventive programming for young adolescents as they traverse the puberty transition. The availability or lack of safety during this life stage could greatly influence access to development opportunities and future trajectories and well-being.

Acknowledgements

This working paper is based on a collaborative project undertaken by the CRISP trust, UNICEF, the KwaZulu-Natal department of education and the population council. We acknowledge Nonkululeko Mthembu for leading the mapping fieldwork; Judith Bruce for her tireless efforts to inform policy-makers of the need for safe social spaces for girls; Cynthia B. Lloyd for her support in identifying this endeavour as a potential project; Sibeso Luswata, Andrea Berther, Gerrit Maritz, and Misrak Elias for guidance during the project; Robert Heidel, Sura Rosenthal, Hannah Taboada, Mike Vosika, Christina Tse and Kirk Deitsch for suggestions on the text and graphics; and Wendy Baldwin, four anonymous referees, and participants in the 22–24 July 2013 UNFPA-Population council adolescent programming workshop in New York for helpful comments.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aguirre, R., & Güell, P. (2002). Becoming men: The construction of masculinity in adolescents and its risks. Washington, DC: OPS/WK Kellogg Foundation/UNFPA.

- Aneshensel, C. S., & Sucoff, C. A. (1996). The neighbourhood context of adolescent mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 37, 293–310. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2137258

- Austrian, K., Hewett, P., Jackson, N., & Soler-Hampejsek, E. (2012). Adolescent girls empowerment program. Retrieved from http://www.popcouncil.org/projects/353_ZambiaAGEP.asp

- Bandiera, O., Buehren, N., Burgess, R., Goldstein, M., Gulesci, S., Rasul, I., & Sulaimany, M. (2012). Empowering adolescent girls: Evidence from a randomized control trial in Uganda. Retrieved from http://econ.lse.ac.uk/staff/rburgess/wp/ELA.pdf

- Bennett, G. G., McNeill, L. H., Wolin, K. Y., Duncan, D. T., Puleo, E., & Emmons, K. M. (2007). Safe to walk? Neighborhood safety and physical activity among public housing residents. PLoS Medicine, 4(10), e306. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040306

- Brady, M. (2005). Creating safe spaces and building social assets for young women in the developing world: A new role for sports. Women's Studies Quarterly, 33(1/2), 35–49. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40005500

- Breinbauer, C., & Maddaleno, M. (2005). Youth: Choices and change. Promoting healthy behaviors in adolescents. Washington, DC: PAHO.

- Brookes, H., & Higson-Smith, C. (2004). Responses to gender-based violence in schools. In L. M. Richter, A. Dawes, & C. Higson-Smith (Eds.), Sexual abuse of young children in Southern Africa (pp. 110–129). Pretoria: HSRC Press.

- CDC. (2013). CDC helps prevent global violence. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violencePrevention/globalviolence/index.html

- Chambers, R. (1994). The origins and practice of participatory rural appraisal. World Development, 22, 953–969. doi:10.1016/0305-750X(94)90141-4

- Choby, A. A., Dolcini, M. M., Catania, J. A., Boyer, C. B., & Harper, G. W. (2012). African American adolescent females' perceptions of neighbourhood safety, familial strategies, and sexual debut. Research in Human Development, 9(1), 9–28. doi:10.1080/15427609.2012.654430

- Chong, E., Hallman, K., & Brady, M. 2006. Investing when it counts: Generating the evidence base for policies and programmes for very young adolescents. Guide and toolkit. New York, NY: UNFPA and Population Council.

- CIET Africa & Greater Johannesburg Southern Metropolitan Local Council. (2000). Beyond victims and villains: The culture of sexual violence in South Johannesburg. Johannesburg: Southern Metropolitan Local Council.

- Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Cummins, S., Curtis, S., Diez-Roux, A. V., & Macintyre, S. (2007). Understanding and representing ‘place’ in health research: A relational approach. Social Science & Medicine, 65, 1825–1838. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.036

- Davison, K. K., & Jago, R. (2009). Change in parent and peer support across ages 9 to 15 years and adolescent girls' physical activity. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 41, 1816–1825. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181a278e2

- Dunbar, M. S., Maternowska, M. C., Kang, M. J., Laver, S. M., Mudekunye-Mahaka, I., & Padian, N. S. (2010). Findings from SHAZ!: A feasibility study of a microcredit and life-skills HIV prevention intervention to reduce risk among adolescent female orphans in Zimbabwe. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 38(2), 147–161. doi:10.1080/10852351003640849

- Dupéré, V., Leventhal, T., & Vitaro, F. (2012). Neighborhood processes, self-efficacy, and adolescent mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 53(2), 183–198. doi:10.1177/0022146512442676

- Erulkar, A., Ferede, A., Girma, W., & Ambelu, W. (2013). Evaluation of “Biruh Tesfa” [Bright Future] program for vulnerable girls in Ethiopia. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 8, 182–192. doi:10.1080/17450128.2012.736645

- Galambos, N. L., Berenbaum, S. A., & McHale, S. M. (2009). Gender development in adolescence. Handbook of adolescent psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Gomez, J. E., Johnson, B. A., Selva, M., & Sallis, J. F. (2004). Violent crime and outdoor physical activity among inner-city youth. Preventive Medicine, 39, 876–881. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.019

- Hilbrecht, M., Zuzanek, J., & Mannell, R. C. (2008). Time use, time pressure and gendered behavior in early and late adolescence. Sex Roles, 58, 342–357. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9347-5

- Human Rights Watch. (2001). Scared at school: Sexual violence against girls in South African schools. New York, NY: Human Rights Watch.

- Jewkes, R. (2013). Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental health problems in South Africa. In C. Garcia-Moreno & A. Riecher-Rössler (Eds.), Violence against women and mental health (pp. 65–74). Basel: Karger.

- Jewkes, R., & Abrahams, N. (2002). The epidemiology of rape and sexual coercion in South Africa: An overview. Social Science & Medicine, 55, 1231–1244. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00242-8

- Jewkes, R., Dunkle, K., Koss, M. P., Levin, J. B., Nduna, M., Jama, N., & Sikweyiya, Y. (2006). Rape perpetration by young, rural South African men: Prevalence, patterns and risk factors. Social Science & Medicine, 63, 2949–2961. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.07.027

- Jewkes, R. K., Dunkle, K., Nduna, M., & Shai, N. (2010). Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity, and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: A cohort study. The Lancet, 376(9734), 41–48. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60548-X

- Jewkes, R. K., Levin, J., Mbananga, N., & Bradshaw, D. (2002). Rape of girls in South Africa. The Lancet, 359, 319–320. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07530-X

- Jewkes, R., Sikweyiya, Y., Morrell, R., & Dunkle, K. (2009). Understanding men's health and use of violence: Interface of rape in HIV in South Africa. MRC. Retrieved from http://www.mrc.ac.za/gender/interfaceofrape&hivsarpt.pdf

- Kaplan, P. S. (2004). Adolescence. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Kim, J. (2010). Influence of neighbourhood collective efficacy on adolescent sexual behaviour: Variation by gender and activity participation. Child: Care, Health and Development, 36, 646–654. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01096.x

- Kimm, S. Y., Glynn, N. W., Kriska, A. M., Barton, B. A., Kronsberg, S. S., Daniels, S. R., … Liu, K. (2002). Decline in physical activity in black girls and white girls during adolescence. New England Journal of Medicine, 347, 709–715. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa003277

- Knerr, W., Gardner, F., & Cluver, L. (2011). Preventing child abuse and interpersonal violence in low- and middle-income countries. SVRI briefing paper. Pretoria: Sexual Violence Research Initiative.

- Lary, H., Maman, S., Katebalila, M., & Mbwambo, J. (2004). Exploring the association between HIV and violence: Young people's experiences with infidelity, violence and forced sex in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. International Family Planning Perspectives, 30, 200–206. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1566494 doi:10.1363/3020004

- Latour, B. (1996). On actor-network theory – a few clarifications. Soziale Welt-Zeitschrift fur Sozialwissenschaftliche Forschung und Praxis, 47, 369. http://www.nettime.org/Lists-Archives/nettime-l-9801/msg00019.html

- Leach, F., & Humphreys, S. (2007). Gender violence in schools: Taking the ‘girls-as-victims’ discourse forward. Gender & Development, 15(1), 51–65. doi:10.1080/13552070601179003

- Leoschut, L., & Burton, P. (2006). How right the rewards? Results of the 2005 national youth victimisation study. Cape Town: Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention.

- Lozano, R., Naghavi, M., Foreman, K., AlMazroa, M. A., & Memish, Z. A. (2013). Department of Error 2010. The Lancet, 381, 628–628. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60348-7

- Mensch, B., Bruce, J., & Greene, M. (1998). The uncharted passage: Girls’ adolescence in the developing world. New York, NY: Population Council.

- Mirsky, J. (2003). Beyond victims and villains: Addressing sexual violence in the education sector. London: Panos Institute.

- Mitchell, C., Moletsane, R., Stuart, J., Buthelezi, T., & De Lange, N. (2005). Taking pictures/taking action! Using photo-voice techniques with children. Children FIRST, 9(60), 27–31.

- Mitchell, C., Reid-Walsh, J., Blaeser, M., & Smith, A. (1998, May 31–June 1). Who cares about girls? In Centering on … the margins: The evaded curriculum (pp. 169–176). Proceedings of the second biannual Canadian Association for the Study of Women and Education (CASWE) International Institute. Ottawa, ON: University of Ottawa.

- Moffett, H. (2006). ‘These women, they force us to rape them’: Rape as narrative of social control in post-apartheid South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 32(1), 129–144. doi:10.1080/03057070500493845

- Morrell, R. (1998). Of boys and men: Masculinity and gender in Southern African studies. Journal of Southern African Studies, 24, 605–630. doi:10.1080/03057079808708593

- MRC-UNISA. (2010). A profile of fatal injuries in South Africa: The national injury mortality surveillance system. Cape Town: Medical Research Council.

- Mukherjee, N. (1993). Participatory rural appraisal (Vol. 1). Retrieved from www.conceptpub.com.

- Murdoch, J. (1998). The spaces of actor network theory. Geoforum, 29, 357–374. doi:10.1016/S0016-7185(98)00011-6

- Naude, C., Prinsloo, J., & Ladikos, A. (2006). Experiences of crime in thirteen African countries: Results from the international crime victim survey. Turin: UNODC-UNICRI.

- Patton, G. C. (2011). Global pattern of mortality in young people. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/esa/population/meetings/egm-adolescents/p02_patton.pdf

- Pinheiro, P. S. (2006). World report on violence against children. New York, NY: United Nations.

- Power, R., Langhaug, L., & Cowan, F. (2007). “But there are no snakes in the wood”: Risk mapping as an outcome measure in evaluating complex interventions. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 83, 232–236. doi:10.1136/sti.2006.022434

- Richter, L. M., Dawes, A., & Higson-Smith, C. (2004). Sexual abuse of young children in Southern Africa. Pretoria: HSRC Press.

- Seedat, M., Van Niekerk, A., Jewkes, R., Suffla, S., & Ratele, K. (2009). Violence and injuries in South Africa: Prioritising an agenda for prevention. The Lancet, 374, 1011–1022. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60948-X

- Sen, A. (2001). Development as freedom. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Shields, N., Fieseler, C., Gross, C., Hilburg, M., Koechig, N., Lynn, R., & Williams, B. (2010). Comparing the effects of victimization, witnessed violence, hearing about violence, and violent behavior on young adults. Journal of Applied Social Science, 4(1), 79–96. doi:10.1177/193672441000400107

- Stromquist, N. P. (1996). Mapping gendered spaces in third world educational interventions. In P. Rolland (Ed.), Social cartography: Ways of seeing social and educational change (pp. 223–248). New York, NY: Garland.

- Townsend, L., Jewkes, R., Mathews, C., Johnston, L. G., Flisher, A. J., Zembe, Y., & Chopra, M. (2011). HIV risk behaviours and their relationship to intimate partner violence (IPV) among men who have multiple female sexual partners in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS and Behaviour, 15(1), 132–141. doi:10.1007/s10461-010-9680-5

- Underwood, C., & Schwandt, H. (2011). Go girls! Initiative research findings report. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health/Center for Communication Programs.

- Upchurch, D. M., Aneshensel, C. S., Sucoff, C. A., & Levy-Storms, L. (1999). Neighborhood and family contexts of adolescent sexual activity. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 920–933. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/354013

- Whitaker, R. C. (2010). The infancy of obesity prevention. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 164, 1167. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.218

- Winton, A. (2005). Youth, gangs and violence: Analysing the social and spatial mobility of young people in Guatemala City. Children’s Geographies, 3, 167–184. doi:10.1080/14733280500161537

- Zona, K., & Milan, S. (2011). Gender differences in the longitudinal impact of exposure to violence on mental health in urban youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 1674–1690. doi:10.1007/s10964-011-9649-3