Abstract

Botswana has been running Safe Male Circumcision (SMC) since 2009 and has not yet met its target. Donors like the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Africa Comprehensive HIV/AIDS Partnership (funded by the Gates Foundation) in collaboration with Botswana's Ministry of Health have invested much to encourage HIV-negative men to circumcise. Demand creation strategies make use of media and celebrities. The objective of this paper is to explore responses to SMC in relation to circumcision as part of traditional initiation practices. More specifically, we present the views of two communities in Botswana on SMC consultation processes, implementation procedures and campaign strategies. The methods used include participant observation, in-depth interviews with key stakeholders (donors, implementers and Ministry officials), community leaders and men in the community. We observe that consultation with traditional leaders was done in a seemingly superficial, non-participatory manner. While SMC implementers reported pressure to deliver numbers to the World Health Organization, traditional leaders promoted circumcision through their routine traditional initiation ceremonies at breaks of two-year intervals. There were conflicting views on public SMC demand creation campaigns in relation to the traditional secrecy of circumcision. In conclusion, initial cooperation of local chiefs and elders turned into resistance.

Introduction

Voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) is esteemed by UNAIDS and World Health Organization (WHO) as a great contribution towards the reduction of HIV infections. The motivation to use VMMC for HIV prevention originates from three large-scale randomised control trials (RCTs) in Rakai, Uganda; Kisumu, Kenya and Orange Farm, South Africa which concluded that VMMC reduces the risk of men acquiring HIV through vaginal sex by 50–60%, is safe and has potential to give lifelong benefits (Auvert et al., Citation2005; Bailey et al., Citation2007; Gray et al., Citation2007). WHO made policy recommendations that countries with high HIV prevalence (specifically African countries) and low prevalence of male circumcision (MC) scale up VMMC as a priority in HIV prevention (WHO, Citation2007). While critics note hastiness in pushing to implement VMMC, the very energetic response by WHO and UNAIDS demonstrates the motivation and deep desire to control this longstanding pandemic (Dowsett & Couch, Citation2007). However, VMMC adds to the number of HIV/AIDS strategic programmes that are not initiated locally but are negotiated into African countries by external bodies (UNAIDS, Citation2010).

Botswana is included among the 14 countries of southern and eastern Africa that follow the WHO recommendations on the implementation of VMMC (Ministry of Health, Citation2010; UNAIDS, Citation2010). After initial reports of a positive response in terms of numbers of males being circumcised (UNAIDS, Citation2010) subsequent reports by WHO and UNAIDS show that, although Kenya and the Gambella region in Ethiopia have achieved over 85% of their targets, most countries are far from meeting their targets for 2016 (WHO, Citation2014). A qualitative study done by USAID in the Turkana county of Kenya revealed that younger and urban men spoke of increasing acceptance of circumcision, while older men were resistant to accept it because of cultural issues (Macintyre et al., Citation2013). The social and cultural context in the countries implementing VMMC might contribute to the reasons why targets are not being met. Very little research has been carried out to explore communities' views on VMMC or to examine tensions between existing social and cultural MC practices and the introduction of biomedical MC.

The objective of this paper is to explore responses to VMMC in relation to MC as part of traditional initiation practices in Botswana. More specifically, we present the views of two communities (with contrasting cultural views on circumcision) on the VMMC consultation and implementation procedures, and campaign strategies.

Biomedical marketing

Social marketing is increasingly used in public health to promote behaviour change (Grier & Bryant, Citation2005) and has been widely used in the promotion of condom use for HIV prevention in developing countries (Sweat, Denison, Kennedy, Tedrow, & O’Reilly, Citation2012). Biomedical marketing is a form of social marketing but used to promote biomedical procedures and pharmaceuticals for example through campaigns in social media (Nelson, Citation2012). Biomedical marketing related to VMMC typically involves accelerating service delivery through mass campaigns that make use of innovative communication and education media strategies (WHO, Citation2011). The public health establishment, which includes UNAIDS, WHO, World Bank, IMF (Ferguson, Citation2006; Jilberto, Citation2004) as well as US institutions like CDC and Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, makes extensive use of biomedical marketing. The focus of biomedical marketing is a central characteristic of a neoliberalist approach that encourages individuals’ application of their entrepreneurial freedom and skills in the market economy as opposed to collective decisions (Finn, Nybell, & Shook, Citation2010; Harvey, Citation2005). The purpose of marketing is to increase the take-up of services by using enticing strategies that are intended to generate demand, increase coverage and uptake rapidly (Finn et al., Citation2010). However, such strategies seem to face challenges in collectivist cultures. Even so, the HIV field that heavily relies on results from large-scale biomedical prevention trials has built its intervention strategies around the neoliberal approach (Rosengarten & Michael, Citation2009). Biomedical marketing strategies for VMMC seem to work in mobilising more men for circumcision in countries like Kenya, while they have had very little impact in other African countries like Botswana (Macintyre et al., Citation2013; NACA, Citation2013; WHO, Citation2014). This contradicts predictions by the Botswana-based acceptability study of 2003 which concluded that 81% of males in Botswana would be willing to circumcise through VMMC (Kebaabetswe et al., Citation2003). Although biomedical marketing has had little success in some countries, the advantage of such a strategy is that it gives individuals freedom of choice for health services (Finn et al., Citation2010). However, authors like Dowsett and Couch (Citation2007) and Aggleton (Citation2007) argue against the insensitivity of recommendations from randomised controlled trials to people's cultural and taboo practices, sexual orientations and social phenomena. In fact, the WHO (Citation2007) technical consultation report recommends sensitivity to culture and drawing on local language and symbols, but the 2011 WHO progress report in the scale-up of MC for HIV prevention in Eastern and Southern Africa focuses on service delivery – and does not capture cultural or social issues (WHO, Citation2011).

Many HIV/AIDS prevention strategies are exclusively based on evidence from biomedically and epidemiologically driven behavioural research agendas. In their contention against these biomedical decisions, Lock and Nguyen (Citation2010, p. 18) argue that scientists work with pre-conditioned ways of seeing and understanding, hence ‘health-related matters are routinely objectified as technical problems to be solved through the application of technology and the conduct of science’. Scientific evidence exerts little or superficial effort in considering local social and cultural realities (Aggleton, Citation2007). Several social scientists, including Dowsett and Couch (Citation2007), Lock and Nguyen (Citation2010) and Parker (Citation2001), advocate that in order to examine the efficacy and effectiveness of the RCTs, they should be considered as a social phenomenon with real human settings, and the local social realities, psychological, behavioural and sexual responses of the research subjects should be incorporated fully when making decisions about medical interventions. Additionally, Campbell, Skovdal, Mupambireyi, and Gregson (Citation2010) encourage sensitivity to cultural factors when implementing HIV prevention strategies.

Much of research carried out on VMMC thus far is biomedical, focusing on exploring the association between MC and HIV; or it involves acceptability studies in different countries (see Kebaabetswe et al., Citation2003; Lukobo & Bailey, Citation2007; Wambura et al., Citation2011); or mathematical models used to estimate the impact of behaviour change and condom use (for example Andersson, Owens, & Paltiel, Citation2011). Very little research has been done on the sociocultural response and behavioural dynamics of the subjects who are recipients of the service. The few qualitative studies carried out in Africa reveal varying sociocultural factors inhibiting the expected response predicted through quantitative research. One study carried out in West African countries by Niang and Boiro (Citation2007) found antagonistic relations between VMMC and cultural practices. Research in Tanzania among traditionally circumcising tribes shows that such cultures would embrace VMMC as long as it is done in a culturally sensitive manner (Wambura et al., Citation2011). Another qualitative study on the impediments to the uptake of VMMC in Botswana by Sabone and colleagues (Citation2013) found that in general, societies accept circumcision; however, the communities were against the fact that the VMMC programme disturbs the social order. They also observed conflict between traditional initiation systems and VMMC. ‘Participants observed that the government would have better outcomes if the MC strategy had taken aboard the traditional initiation systems through a collaborative process’ (Sabone et al., Citation2013, p. 3).

Male circumcision in Botswana

In Botswana traditional initiation for men was conducted in the wilderness in selected sites and commonly during winter (Mosothwane, Citation2001). The initiates were separated from the community for skills training and challenges and only men were allowed (Comaroff, Citation1985; Mosothwane, Citation2001). All initiates underwent circumcision at the same time; their collective endurance of the pain reflected masculine strength (Meissner & Buso, Citation2007; Mosothwane, Citation2001). One knife was used to circumcise all initiates (Meissner & Buso, Citation2007) as a rite of affirmation marking transformation to manhood (Comaroff, Citation1985; Mosothwane, Citation2001; Turner, Citation1969). Missionaries considered the practice barbaric and indecent and therefore enforced its abolishment during the twentieth century (Comaroff, Citation1985; Mosothwane, Citation2001). A few tribal communities like the Bakgatla of Mochudi village resisted the abolition of initiation (Mosothwane, Citation2001). The practice went through a wave of changes throughout the years with some tribal chiefs disregarding it in fear of punishment and others reinstating it, sometimes without MC. The current tribal leadership of Mochudi has revived the practice and the community upholds it as a special identity of their tribe (Setlhabi, Citation2014).

VMMC represents a new phase in the context of MC in Botswana. External funding has supported biomedical marketing in the media including, bill-board, radio and TV advertising. In addition, a pop artist has been contracted as the campaign ambassador to attract men into the programme. Dedicated clinics have been set up in selected areas in addition to general public health centres where MC is conducted in hygienic, clinical conditions throughout the year by both female and male medical practitioners. Procedure in the clinics follows WHO recommendations (Ministry of Health, Citation2010). UNAIDS (Citation2013, p. A7) records that in 2012 in Botswana the HIV prevalence rate for adults 15–49 years was 23%. External organisations like the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Africa Comprehensive HIV/AIDS Partnership (ACHAP) funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation partner with the Government of Botswana's Ministry of Health (MH) to scale up VMMC and encourage HIV-negative men of ages 13–49 to circumcise. The programme in Botswana is called safe male circumcision (SMC). The acceptability study that was done by Kebaabetswe et al. (Citation2003) among 15 ethnic groups in the country contributed to the decision for implementation of SMC in Botswana. The study included a total of 605 respondents of which 238 were uncircumcised men; among these men 61% stated they were willing to circumcise and this percentage increased to 81% after they received further information on MC (Kebaabetswe et al., Citation2003, p. 214). This study largely covered the traditionally non-circumcising tribes (Kebaabetswe et al., Citation2003). Botswana progress reports from MH and external organisations like CDC and ACHAP reflect very low numbers of circumcisions were performed among HIV-negative males: only 39% of the 2012 annual target was circumcised (NACA, Citation2013).

Methods

This study used ethnographic methods to explore the cultural relevance of SMC for HIV prevention in Botswana.

Research sites

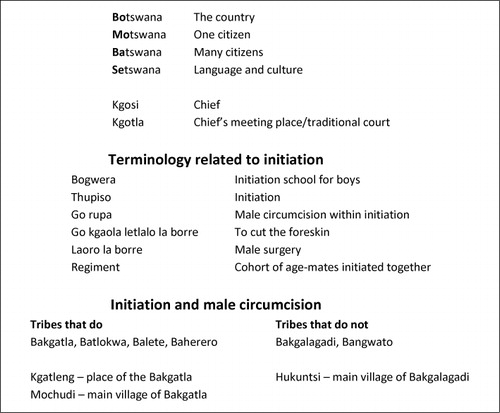

Besides collecting data in Gaborone, the capital, from the leaders of the partner organisations, two rural research sites were purposefully selected in order to contrast responses of tribes that conduct or do not conduct traditional MC and initiation. Mochudi, a village 40 km to the east of Gaborone, is home to the Bakgatla tribe which practices initiation and MC while Hukuntsi, a village in the remote western part of the country, is home to the Bakgalagadi tribe which does not practice initiation or MC ().

Participants and recruitment

Data were collected from four groups of participants. The first group included leaders from the three partner organisations, namely MH SMC Co-ordinator, CDC SMC Co-ordinator and ACHAP Programmes Director. In addition, the MH Project Adviser (adviser on technicalities and current research) and the MH Northern Regional Co-ordinator (oversees implementation in the northern part of country) were included. All leaders were contacted directly to arrange meetings. The second group of participants included implementers in the two rural research sites. The ACHAP team in Mochudi was contacted through the District Health Management Team (DHMT). Contact with the DHMT in both Mochudi and Hukuntsi was facilitated through MH. Third, social workers who advise men about participation in SMC were included. The fourth group of participants included traditional leaders. The intention was to interview only the chief in each of the rural research sites (in each case they had been contacted directly by the first author), but on the agreed day of the interview with the Bakgatla chief in Mochudi, the first author was introduced by the chief to the group of 25 traditional leaders who happened to be meeting the chief that day. See for details.

Table 1. Details of participants and data collection methods.

Data collection

Data were collected through participant observation (for example at meetings between the partner organisations; at SMC marketing campaigns), in-depth interviews (IDIs) and focus group discussions (FGDs). The leaders of the partner organisations and the chiefs were interviewed individually in their own offices. Data were collected from the implementers and the social workers through focus group discussions (see for details). The first author, who collected all the data, is a woman. Interviewing men on issues that deal directly with the most secretive part of their body came with opposition at village level. This being anticipated, the first author dressed very conservatively and followed all customary protocol. The meeting with the Bakgatla traditional leaders was not planned and, given the taboos surrounding the topic, the participants initially resisted. However, as the interview continued they became fully engaged and rich data were generated; the interview ended with the traditional leaders asking the first author to be their envoy to the MH. It was too large a group to be called a focus group discussion, although several of the leaders responded to each issue. In all the data collection, topic guides were used to explore issues such as the leadership of the SMC strategy, differences and overlaps between SMC and traditional initiation practices, the consultation processes and response at different levels of the community, the response of the community towards the uptake of SMC, the impact of the demand creation strategies and the community response.

Data analysis

All interviews and focus group discussions were audio recorded with permission from the participants. They were later transcribed by research assistants and, where necessary, translated from Setswana into English by the first author. The transcripts were then imported into NVivo 10 (a computer software package designed for qualitative data management) and analysed following the steps in Attride-Stirling's (Citation2001) Thematic Network Analysis. The data analysis team comprising the first author and two Ph.D. students read the transcripts several times to acquaint themselves with the data. Each of them created labels to represent similar re-occurring codes, and text segments were inductively coded. Basic themes were abstracted and refined from the coded text segments and clustered to form the organising and then the global themes. The team discussed organising and global themes to reach a consensus, strengthening the objectivity of the data. The last two groups of themes can be seen in . Links between the themes were then explored and cross-analysed across communities and different groups of participants. Information from reviewed literature was used to contextualise the analysis.

Table 2. Themes emerging from data analysis.

Ethics

Research clearances were obtained from the Norwegian Social Sciences Data Services and MH in Botswana. At MH level, we had to acquire two written permits: one was a general acceptance of the topic of the research, and the other was permission allowing the interviewing of health personnel. At the organisational level, ACHAP and CDC accepted the MH permits as appropriate ethical clearance. Informed consent was obtained from individual and focus group participants of all organisations that we sought data from and from the leaders of participating village communities. At community level the chief signed the consent form and gave verbal permission to interview the traditional leaders. This reflects customary ethical protocol where the chief consents on behalf of his elders (who we have called traditional leaders). Culturally, this is a highly sensitive research exploration; therefore, substantial effort was made to assure confidentiality to informants.

Findings

Our exploration of responses to SMC in relation to circumcision as part of traditional initiation practices is presented according to themes emerging from the data analysis. Organising themes were grouped under four global themes: cultural circumcision taboos breached, public marketing, consultation and participation, and HIV testing.

Cultural circumcision taboos breached

Secrecy

Traditional leaders clearly described cultural circumcision as a secret domain not to be shared with women. They expressed astonishment and initially objected that a woman researcher asked for general information about the cultural practice of initiation and circumcision. During discussions with 25 elders of Mochudi, one elder spoke loudly as he threw arms in the air, as if to say go away: ‘We never did those things… These are the things we are not allowed to ask about. You cannot just ask about that’. The words of wrath expressed by this first respondent were reiterated in a discussion with a taxi driver later in the year: ‘Young as you are, a woman for that matter! You are asking men, even old men…, about their penis’?

Breaching of secrecy was also questioned in the public campaign approaches and the circumcision surgical services done in public clinics. One elder said:

We know our tradition differently. We gather first for initiation in the wilderness. It is a special training for men… We are not initiated in the village; we are initiated in the wilderness. They are talking about it [the penis] anyhow in public. In initiation men are recruited house to house. Things concerning initiation are a secret.

you don't tell anybody, you don't advertise, you don't say anything that you will be at a particular village doing circumcision because there is an initiation going on. No you don't. So that's how it is. We see it as a challenge. Truly speaking, with tribes in our country which are doing initiation we seriously have a challenge.

Male domain

Traditionally, circumcision was distinguished as a male domain. This was strictly upheld in traditionally circumcising cultures. Upholding such cultural principles caused conflict between the traditional and the biomedical provision of circumcision. One of the partners expressed such conflict as frustrating. The SMC programme used women health personnel to circumcise, but women were not allowed in the traditional initiation practices. This was revealed through stipulated requirements forwarded by the chief of Ramotswa village to the SMC team assigned to circumcise the graduating regiment:

And then what happened last year with the Balete? They organized their own traditional initiation. They told us they didn't even want to see a lady during circumcision, totally no ladies that side. So we complied… The tent was pitched in between the village and the initiation site, far from the initiation site.

We do come to the hospital for circumcision. But it should be men who circumcise men.… Well some say it is ok for women to circumcise men. No, it is against tradition.

Language controversies

One officer explained that different tribes used specific language phrases to describe and explain traditional initiation and performances related to it like circumcision. SMC health personnel struggled to find the right words to use for medical circumcision, and their attempts to adapt to traditional phrases misrepresented traditional meanings and led to serious controversies ending in publicly demonstrated protests by chiefs.

One elder expressed unhappiness in the misuse of the traditional phrase ‘go rupa’ that means circumcision within initiation, contesting it as wrongly used by the SMC team to mean removing the foreskin:

E1: They are just beating about the bush using our language to attract men. Haven't you seen it on TV?

Researcher: I have seen it

E1: No, answer and say you have seen the advert showing men heading the ball calling men for ‘Go rupa!’ I want you to say that if you have seen it. That is a wrong phrase!

No no no… Then let them use the word ‘thupiso’ [initiation] in their own communities, not here. They really hurt us. I do not want this phrase ‘go rupa’ [circumcision within initiation] used on radio to mean just cutting the foreskin. SMC is not about initiation.

So they came here, the chiefs, very angry with us. They met with [Ministry of Health] They gave us instructions not to talk about ‘go rupa’. They instructed us to use the phrase ‘go kgaola letlalo la borre’ [to cut the male foreskin]… We complied. A few years down the line we were blamed by the same House for using the phrase ‘go kgaola letlalo la borre’. They said to us ‘these words that you are using are insults, you are insulting us’.

Public marketing

The chief's voice is stronger

In several instances the chief's voice proved to be stronger and commanded obedience to the traditional standards rather than the SMC approach to public marketing. This was seen as a stumbling block to the progression of SMC. One officer said:

that is where the gap is currently. And I think it is really haunting us. The circumcising tribes in the country, Batlokwa, Balete, Bakgatla are giving us a very big challenge … of resistance to this government program. And we cannot convince the chiefs there, we just can't. Our main target group of men 25 years and above is hard to reach because the chiefs are very clear, they are going to wait for the next Bogwera [initiation school].

I would say Ministry of Health should talk to the chiefs. They should ask the chiefs to call the public on their behalf. The chief could make arrangements with his people to participate in SMC without giving up the culture. Let it come from the chief; [he emphasized very strongly and even stood up]. We will listen to the chief. Not Vee.

We have expressed that we thought Ministry of Health was going to help. Now they send us Vee and young people to insult us. They should respect our culture and not confuse it. Go and tell them to come and talk to our chief.

Generational clashes

Biomedical marketing strategies were reported to be causing generational clashes – between adults and children. Public campaigns were viewed as contributing to children's waywardness in contrast to initiation practices which built and moulded personhood. One man said: ‘You know our children no longer listen to us. They listen to Vee's music in public’. One of the 25 elders described how SMC public talks about the male penis caused children to unintentionally disrespect their elders:

They do their education on radio. It is embarrassing. When a child gets home he asks ‘Papa, it is said that all males have to cut the foreskin, do we have to go Papa!’ How do you answer that? …These adverts just raise questions in the listeners' minds.

Sexualising circumcision

Comments from traditional elders, professionals and other community members revealed strong dissatisfaction in the sexual language used to appeal to men for circumcision. Six social workers who work as advocates of SMC in Hukuntsi district saw Vee's SMC campaigns as sexualized and only benefiting the campaigners themselves. This made the community question the quality of the campaigns. One social worker said:

I think that Vee's campaigns benefit Vee himself moneywise. It does not benefit the masses, what we question is the quality of information they give people. They just make the whole thing colourful; it swipes people's emotions without their understanding. It creates confusion in the masses. It's all about enjoying sex and prevention of cervical cancer.

I don't know… How exactly are the men benefiting out of this? We are just told about the 60% chances of reduction. The rest is just additional colourful attractions like ‘If you are circumcised you will enjoy sex more’. Male circumcision is sexualized.

with Vee I would say we use him to pull a crowd and get people to register for circumcision but at the end of the day we don't see those numbers. But of course Vee is a crowd puller.

I hate it when it is announced on radio that all Bakgatla men who want to go for initiation should go for SMC. Vee's music and dancing is disgusting. This MC campaign done by Vee is insulting us.

Consultation and participation

Initial cooperation

Initially, the community embraced SMC and cooperated with the health teams in anticipation that it would complement their culture. The community elders explained: ‘So in our Sekgatla initiation there is circumcision to prove manhood. That is why when SMC was introduced Bakgatla responded well through their initiation regiments’.

This initial cooperation was affirmed by one of the ACHAP team members, who explained:

From the beginning the leadership were receiving and supporting the SMC programme. In 2009 they had a group of men for initiation. They brought everyone from the wilderness to the clinic for circumcision. Even though not all of them circumcised…. Kgatleng as compared to other districts had large numbers of circumcision through the help of this initiation, especially in 2009.

Disillusionment, frustration and resistance

Later events revealed that SMC partners’ consultation with traditional leaders was done with a seemingly superficial, non-participatory approach. Local leaders were disappointed by the fact that practices surrounding the traditional rite of circumcision were not adhered to, as they expected. Interestingly, both the SMC implementers and the traditional leaders expected compliance by the other party to their own strategies, which left the issue controversial and men declining medical circumcision. The implementing officers explained the change from embracing the programme to rejection of programme between the period 2009 and 2011.

but over time like in the year 2011 when they went for initiation, they did not come for circumcision at the clinic because of many challenges with the culture … like the use of clinics for circumcision, HIV testing. Also they have a special time in which it is done. You see, they believe that circumcision should only be done in winter.

Lack of genuine consultation

Lack of genuine consultation caused resistance beyond circumcising cultures. Bakagagadi, a non-circumcising culture residing in the village of Hukuntsi, also had resisted SMC at its initial introduction. A traditional leader explained that they viewed SMC as government imposing other cultures into their culture:

We wondered when this SMC came. We do not want other cultures transferred to our culture. Bakgatla and Balete are people who do circumcision culturally. Why couldn't they go to them? Our men here never did that. How could I speak to the tribe about this?

Another form of resistance

The Herero culture, which practice private traditional circumcision for individual males, were reported to ignore SMC campaigns in silence and, instead, to continue their private traditional circumcision. An officer narrated this with frustration:

Now we have a challenge which is coming out clearly with the Herero culture, what happens that side is that they do things in silence. They are not coming out to say don't come in to our village. They use traditional circumcisers from their fellow tribes in Namibia to do home based circumcision on boys at a particular time, collect their earnings and go back.

because it is their secret and done so privately we have not even accessed their way of circumcising, and it may be hard to get the right information about how it is done so that we could collaborate. It is the hearsay you know. I have not personally sat with the traditional circumcisers to get the explanation. We hear from other Hereros that have information.

There was an indication that when the health personnel explained SMC clearly to the communities, men showed interest to participate. This was explained by an officer in Hukuntsi:

When I got here there was this talk of bringing a foreigner, a different culture to their culture, but after explaining … now I think people are starting to understand why circumcision is being brought to the area. They are now slowly coming.

Genuine consultation crucial

It seems partners, in their frustration, realised that consultation with the communities was crucial. An officer admitted this and recommended the need to consult the communities through their leaders:

So that's the main challenge, the main reason why we are not succeeding. I think looking back I will never do a programme like this again … I would start with the key partner who is the people of Botswana, the beneficiaries and the cultural structures like the community leaders or the religious leaders.

HIV testing

Elements of the minimum package for SMC that include counselling and voluntary HIV testing were repeatedly mentioned as other barriers that blocked men from circumcising. HIV testing, in particular, seemed to scare men away even if they would opt for circumcision. One of the partners said:

You see most people these days are scared to test for HIV, which also chases them away. Some are scared to go to the hospital for SMC, not that they do not want to circumcise. They do. They are scared.

Discussion

This study reveals the challenges international organisations and MH faced to meet their targets. It reveals frustrations on both sides in the interaction between communities and programme partners. The frustrations are rooted in the different underlying assumptions and ideologies. There was collision of different underlying beliefs and views on MC. Traditional circumcision is deeply interwoven within the concept of collectivism and masculinity. Even though MH made attempts to work with villages to incorporate SMC into part of the initiation practice, its individual-based procedure and marketing strategies still breached the requirements of secrecy and the collective nature of the rite. This is not all surprising because the strategic recommendations for VMMC come from part of the global public health establishment, WHO, which like others, has a neoliberal bent (Harvey, Citation2005). Aggleton (Citation2007) contends that cultural MC is a performance connected to deep-seated beliefs and ideologies. It is not just a simple prevention technology.

Finn et al. (Citation2010) argue that the introduction of neoliberalism put some governments under pressure since its emphasis on individual empowerment compelled them to change their social structures. Even though neoliberalism offers possible new perspectives, it has been criticised for intruding into local contexts in different ways raising new and challenging questions on implementation of practices (Ferguson, Citation2006; Finn et al., Citation2010).The study reveals that some of the marketing strategies for SMC in Botswana focus on the market and the individual; marketing phrases are fashioned to make sure that individuals want the product (Finn et al., Citation2010). In opposition to collectivism, neoliberalism sets processes that favour privatisation of services – the primacy of individual as opposed to collective responsibility (Finn et al., Citation2010). The enticing language used in marketing SMC to generate demand (Hankins, Forsythe, & Njeuhmeli Citation2011) brought discomfort to community leaders. ‘Disgusted’ and ‘Frustrated’ were the terms uttered by the traditional leaders towards the marketing of individualised SMC – working against the local tradition of collectivism (Comaroff, Citation1985). This indeed is what McFalls (Citation2010) calls ‘iatrogenic violence’ – medical intervention that violates societal practice. Even though SMC disturbs the cultural equilibrium, global health politics would still view the SMC implementation strategy as ethical because medical intervention is exempted from ethical critique as it is dedicated to saving human life (McFalls, Citation2010). The biomedical marketing approach serves as an advantage and a rival to the culture as well as an impediment to men's response to circumcise.

Planning for SMC was based on the assumption of acceptability as per Botswana's acceptability study on medical circumcision (Kebaabetswe et al., Citation2003). While VMMC would be accepted by both circumcising and non-circumcising communities, the top-down management and lack of input from the community worked against its acceptability in practice. Community responses to the actual implementation depict lack of acceptability. Acceptance of interventions is shaped by the complex local context. Dowsett and Couch (Citation2007) contend that medical interventions that concern human behaviour and societal networks are bound to fail if such decisions are based only on clinical trials and cross sectional surveys. The voice of social researchers has demonstrated that embracing the social context is paramount in implementing ‘foreign’ biomedical interventions specifically those that concern men's sexuality (Parker, Citation2001). Notwithstanding published studies done years back by Heald (Citation2002) and the recent study by Sabone and colleagues (Citation2013) that advocate for sensitivity to local understandings of male sexuality, WHO and international donors still seem to resist reflecting on these but continue to impose their top-down global agendas.

There were two types of resistance to SMC. One tribe counterattacked, while the other was shocked and confused. The Bakgatla tribe initially cooperated but resisted SMC out of disillusionment; the Bakgalagadi, a non-circumcising tribe, were confused about foreign practice ‘being imposed’ into their culture. Other tribes referred to by the respondents include the Herero who ignored the SMC campaigns and carried out its cultural practices secretly; another, Balete, negotiated so that SMC was conducted on their terms. In all these communities SMC workers were frustrated by the low turn-up of men for circumcision. Even though the SMC workers claim that the communities were consulted, it is clear that consultation with custodians of culture was done in a superficial manner. International interventions’ consultations are often presented as preconceived proposals where the ‘process is not an attempt to ascertain the outcome and priorities, but rather to gain acceptance for an already assembled package’ (Botes & van Rensburg, Citation2000, p. 43). Rifkin (Citation1996) explains that target-oriented programmes tend to dominate and control because they value the cost of time over and above the value of negotiations hence they rush implementations leaving the communities behind. Designers of medical programmes like this one should know that people live within a social cultural context and reason with their cultural standards and expectations before accepting externally imposed programmes (Skovdal et al., Citation2011). We concur with anthropologists’ and sociologists’ views that efficiency of programmes would be maximised by embracing sociocultural contexts in implementation (Aggleton, Citation2007; Dowsett & Couch, Citation2007).

In order to avoid disillusion, frustration and resistance, genuine community consultation is crucial. Community's initial cooperation was a loud message for openness and flexibility while the ultimate resistance was a cry to be heard. SMC programme leaders could have avoided language controversies, the breaching of cultural taboos like secrecy and male domain spaces if they had genuinely explored crucial cultural observances and aligned their biomedical approach to circumcision within the operations of the existing cultural environment. Comaroff (Citation1985) explains that circumcision is an integral part of initiation that is done in seclusion of males being initiated with a high level of secrecy about what the cohorts experience when in the wilderness. In agreement with Niang and Boiro (Citation2007) and Sabone et al. (Citation2013), our study reveals antagonism between the cultural practice of secrecy in circumcision proceedings and the SMC strategy that has no restrictions to participants in their procedures. Collision between the biomedical approaches and the requirements of traditional practices in Mochudi and Ramotswa discredited the assumption that, in places where male persons are expected to be circumcised traditionally, there is high desire to conform and get circumcised under VMMC for HIV prevention (UNAIDS, Citation2007). While the assumption could be true, we notice that discrediting the voice and opinions of chiefs is a fundamental mistake since they are the traditional medium used to convince the community for participation (Comaroff, Citation1985). This study suggests an urgent need for a high level of cultural sensitivity, embracing and incorporating cultural taboos when biomedical interventions are to be carried out. In fact, the tension between traditional and public health strategies is likely to emerge with other new biomedical HIV prevention strategies, if cultural conditions are not taken into consideration.

While the sociocultural concerns are paramount to the success of SMC programme, it should be appreciated that these programmes operate within a set of constraints, some of which might be flexible and others which are more rigid. These constraints include funding environment, indicators used to measure success and time for scale required to achieve the desired outcome (i.e. infections averted). The traditional leaders therefore need to be challenged to ensure that men's enactment of the socially constructed versions of manhood does not place men at a disadvantage by inhibiting them from taking advantage of life-saving HIV services (Skovdal et al., Citation2011). The perception of men is that HIV testing is mandatory within SMC and they do not want to go for HIV testing. This puts them at risk of not taking timely advantage of knowing their HIV status and benefiting from the SMC HIV prevention service (Skovdal et al., Citation2011). Given the pointers on how to make HIV prevention services more culturally acceptable, MH and its implementing partners need to prioritise preparation of communities and participatory consultation prior to implementation so that resources are channelled towards relevant approaches suggested by communities. In agreement with Skovdal et al. (Citation2011) and Aggleton (Citation2007), we argue that incorporating societal values on male sexuality and adapting male friendly services is vital in shaping sexual practices relevant to HIV transmission and prevention.

We propose a future research agenda that focuses on exploring a step by step relevant and effective approach that communities could structure for advice and guidance to the VMMC programme donors and implementers. Such community-defined strategies could help save on a lot of resources that are otherwise used without much results.

Limitations of the study

While reflexivity was systematically applied throughout data collection, it is possible that the first author's gender, as a woman, may have restricted responses by men; the objections quoted above show that the involvement of women is considered culturally insensitive. Also, open ended questions allow room for expression of passionate and emotional views that may not be a general view of the communities or organisations represented. While the results may not be specifically generalisable they do provide an insight into cultural reasons for the resistance to SMC. Also, the lessons learnt, like the need for genuine consultation, are valuable for other countries to consider. The findings of this study are particularly relevant for rural settings and do not give the perspective of how this is working in larger and urban communities. The response given by the cultures represented in this study may not necessarily represent the views of other ethnic groups within the country.

Conclusion

The findings from this study show substantial cultural resistance to and superficial participation in SMC in Botswana both in circumcising and non-circumcising cultures. Issues that have generated resistance include the public marketing campaigns, the sexualized language and the fact that implementing health staff includes women. Chiefs and traditional leaders at first cooperated with SMC but later discouraged their men from participating. Cultural resistance has a significant impact on the SMC programme. This study particularly reveals consequences of superficial consultation and how biomedical interventions fail to take full advantage of sociocultural channels to maximise demand for health services. VMMC does not fit well in the two cultural settings examined in this study.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants in this study, without whom this paper would not have been possible. We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for the enormous work they have done in helping us produce a paper of good quality.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aggleton, P. (2007). ‘Just a snip’? A social history of male circumcision. Reproductive Health Matters, 15(29), 15–21. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(07)29303-6

- Andersson, K. M., Owens, D. K., & Paltiel, A. D. (2011). Scaling up circumcision programs in southern Africa: The potential impact of gender disparities and changes in condom use behaviors on heterosexual HIV transmission. AIDS and Behavior, 15, 938–948. doi:10.1007/s10461-010-9784-y

- Attride-Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1, 385–405. doi:10.1177/146879410100100307

- Auvert, B., Taljaard, D., Lagarde, E., Sobngwi-Tambekou, J., Sitta, R., & Puren, A. (2005). Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: The ANRS 1265 Trial. PLOS Medicine, 2(11), e298. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298.st003

- Bailey, R. C., Moses, S., Parker, C. B., Agot, K., Maclean, I., Krieger, J. N., … Ndinya-Achola, J. O. (2007). Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 369, 643–656. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60312-2

- Botes, L., & van Rensburg, D. (2000). Community participation in development: Nine plagues and twelve commandments. Oxford University Press and Community Development Journal, 35, 41–58.

- Campbell, C., Skovdal, M., Mupambireyi, Z., & Gregson, S. (2010). Exploring children's stigmatisation of AIDS-affected children in Zimbabwe through drawings and stories. Social Science & Medicine, 71, 975–985. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.028

- Comaroff, J. (1985). Body of power spirit and resistance: The culture and history of a South African people. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Dowsett, G. W., & Couch, M. (2007). Male circumcision and HIV prevention: Is there really enough of the right kind of evidence? Reproductive Health Matters, 15(29), 33–44. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(07)29302-4

- Ferguson, J. (2006). Global Shadows: Africa in the neoliberal world order. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Finn, J. L., Nybell, L. M., & Shook, J. J. (2010). The meaning and making of childhood in the era of globalization: Challenges for social work. Children and Youth Services Review, 32, 246–254. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.09.003

- Gray, R. H., Kigozi, G., Serwadda, D., Makumbi, F., Watya, S., Nalugoda, F., … Chen, M. Z. (2007). Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: A randomised trial. The Lancet, 369, 657–666. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60313-4

- Grier, S., & Bryant, C. A. (2005). Social marketing in public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 26, 319–339. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144610

- Hankins, C., Forsythe, S., & Njeuhmeli, E. (2011). Voluntary medical male circumcision: An introduction to the cost, impact, and challenges of accelerated scaling up. PLOS Medicine, 8(11), e1001127. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001127

- Harvey, D. (2005). A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Heald, S. (2002). It's never as easy as ABC: Understanding of AIDS in Botswana. African Journal of AIDS Research, 1(1), 1–10. doi:10.2989/16085906.2002.9626539

- Jilberto, A. E. F. (2004). The political economy of neoliberal governance in Latin America: The case of Chile. In J. Demmers, A. E. F. Jilberto, & B. Hogenboom (Eds.), Good governance in the era of global neoliberalism: Conflict and depolitisation in Latin America, Eastern Europe, Asia and Africa (pp. 33–55). London: Routledge.

- Kebaabetswe, P., Lockman, S., Mogwe, S., Mandevu, R., Thior, I., Essex, M., & Shapiro, R. L. (2003). Male circumcision: An acceptable strategy for HIV prevention in Botswana. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 79, 214–219. doi:10.1136/sti.79.3.214

- Lock, M., & Nguyen, V. K. (2010). An anthropology of biomedicine. West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell.

- Lukobo, M. D., & Bailey, R. C. (2007). Acceptability of male circumcision for prevention of HIV infection in Zambia. AIDS care, 19, 471–477. doi:10.1080/09540120601163250

- Macintyre, K., Moses, N., Andrinopoulos, K., Bornstein, M., Ochieng, A., Muraguri, N., … Bertrand, J. T. (2013). Exploring aspects of demand creation and mobilisation for male circumcision in Turkana, Kenya. Baltimore, MD: USAID.

- McFalls, L. (2010). Benevolent dictatorship: The formal logic of humanitarian government. In D. Fassin & M. Pandolfi (Eds.), Contemporary states of emergency: The politics of military and humanitarian interventions (pp. 317–334). New York, NY: Zone Books.

- Meissner, O., & Buso, D. L. (2007). Traditional male circumcision in the Eastern Cape – scourge or blessing? South African Medical Journal, 97, 371–373.

- Ministry of Health. (2010). Safe male circumcision: Additional strategy for HIV prevention: A national strategy. Gaborone: Government of Botswana.

- Mosothwane, M. N. (2001). An ethnographic study of initiation schools among the Bakgatla ba ga Kgafela at Mochudi 1874–1988. Pula Botswana Journal of African Studies, 1, 144–165.

- NACA. (2013). National AIDS council report HIV and AIDS program performance: October to December 2012 quarterly report. Gaborone: Ministry of State President.

- Nelson, B. (2012). Business and science: In the market. Nature, 487, 261–263. doi:10.1038/nj7406-261a

- Niang, C. I., & Boiro, H. (2007). ‘You can also cut my finger!’: Social construction of male circumcision in West Africa, a case study of Senegal and Guinea-Bissau. Reproductive Health Matters, 15, 22–32. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(07)29312-7

- Parker, R. (2001). Sexuality, culture, and power in HIV/AIDS research. Annual review of anthropology, 30, 163–179. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.30.1.163

- Rifkin, S. B. (1996). Paradigms lost: Toward a new understanding of community participation in health programmes. Acta Tropica, 61(2), 79–92. doi:10.1016/0001-706X(95)00105-N

- Rosengarten, M., & Michael, M. (2009). Rethinking the bioethical enactment of medically drugged bodies: Paradoxes of using anti-HIV drug therapy as a technology for prevention. Science as Culture, 18, 183–199. doi:10.1080/09505430902885565

- Sabone, M., Magowe, M., Busang, L., Moalosi, J., Binagwa, B., & Mwambona, J. (2013). Impediments for the uptake of the Botswana Government's male circumcision initiative for HIV Prevention. The Scientific World Journal, 2013, 1–7. doi:10.1155/2013/387508

- Setlhabi, G. K. (2014). I took an allegiance to secrecy: Complexities for conducting ethnographic research at home. Africa, 84, 314–334. doi:10.1017/S0001972014000059

- Skovdal, M., Campbell, C., Madanhire, C., Mupambireyi, Z., Nyamukapa, C., & Gregson, S. (2011). Masculinity as a barrier to men's use of HIV services in Zimbabwe. Globalization and health, 7(13), 1–14. doi:10.1186/1744-8603-7-13

- Sweat, M. D., Denison, J., Kennedy, C., Tedrow, V., & O’Reilly, K. (2012). Effects of condom social marketing on condom use in developing countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis, 1990–2010. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 90, 613–622.

- Turner, V. (1969). The ritual process: Structure and anti-structure. London: Routledge and Keegan Paul.

- UNAIDS. (2007). Male circumcision: Context, criteria and culture (part 1). Feature Stories. Retrieved from http://www.UNAIDS.org/en/resources/presscentre/featurestories

- UNAIDS. (2010). Report on the global AIDS epidemic. Geneva: Author.

- UNAIDS. (2013). Report on the global AIDS epidemic. Geneva: Author.

- Wambura, M., Mwanga, J. R., Mosha, J. F., Mshana, G., Mosha, F., & Changalucha, J. (2011). Acceptability of medical male circumcision in the traditionally circumcising communities in Northern Tanzania. BMC Public Health, 11, 373. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-373

- WHO. (2007). New data on male circumcision and HIV Prevention: Policy and programme implications. Geneva: Author.

- WHO. (2011). Progress in scale-up of male circumcision for HIV prevention in eastern and southern Africa: Focus on service delivery. Geneva: Author.

- WHO. (2014). Global uptake on the health sector response to HIV. Geneva: Author.