ABSTRACT

The Stigma Assessment and Reduction of Impact project aims to assess the effectiveness of stigma-reduction interventions in the field of leprosy. Participatory video seemed to be a promising approach to reducing stigma among stigmatized individuals (in this study the video makers) and the stigmatisers (video audience). This study focuses on the video makers and seeks to assess the impact on them of making a participatory video and to increase understanding of how to deal with foreseeable difficulties. Participants were selected on the basis of criteria and in collaboration with the community health centre. This study draws on six qualitative methods including interviews with the video makers and participant observation. Triangulation was used to increase the validity of the findings. Two videos were produced. The impact on participants ranged from having a good time to a greater sense of togetherness, increased self-esteem, individual agency and willingness to take action in the community. Concealment of leprosy is a persistent challenge, and physical limitations and group dynamics are also areas that require attention. Provided these three areas are properly taken into account, participatory video has the potential to address stigma at least at three levels – intrapersonal, interpersonal and community – and possibly more.

Introduction

The woman quoted in the title of this paper is 26 years of age and lives in Cirebon District, Indonesia. She married a couple of years ago and has a daughter. She has been affected by leprosy and has completed multi-drug therapy (MDT). She is cured and has no impairments or visible signs but nevertheless feels insecure and ashamed because of having been infected by the disease. Health-related stigma is an important problem in the field of public health as it affects the lives of those who experience it and plays a role in the control and management of stigmatised conditions. Leprosy is the archetypal stigmatised health condition, but stigma also plays a role in other diseases such as HIV and AIDS, tuberculosis, a range of mental illnesses, Buruli ulcer, lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis and leishmaniasis (Atre, Kudale, Morankar, Gosoniu, & Weiss, Citation2009; Person, Bartholomew, Gyapong, Addiss, & van den Borne, Citation2009; Rafferty, Citation2005; Root, Citation2010; Rüsch, Angermeyer, & Corrigan, Citation2005; Weiss, Citation2008).

Leprosy continues to affect millions of people in large parts of Asia, Africa and Latin America. In 2013, 215,656 new leprosy cases were reported worldwide (WHO, Citation2014). Indonesia – with 16,856 new cases in 2013 – ranks third after India and Brazil as having the highest number of recorded new cases (WHO, Citation2014). Of the 34 provinces in Indonesia, 12 have detection rates of new cases in excess of 10/100,000 population and West Papua has a rate above 100/100,000 (Ministry of Health Indonesia, Citation2012). Stigma can result in delaying the presentation of symptoms and thus delaying the diagnosis of leprosy (Heijnders, Citation2004a; Nicholls, Wiens, & Smith, Citation2003). This prolongs the period of infectiousness and undermines control and management of the disease in general. Delayed treatment also increases the risk of disability, which in turn increases the risk of experiencing stigma.

The Stigma Assessment and Reduction of Impact (SARI) project aims to develop and assess the effectiveness of three stigma-reduction interventions in Cirebon District, Indonesia. VU University Amsterdam and Universitas Indonesia started the project in 2010. The SARI project adopted the interactive learning and action (ILA) approach, an action–research methodology, the key principles of which are participation, inclusion and transdisciplinarity. These principles were reflected in the recruitment of the research assistants, some of whom are affected by leprosy or have a disability.

There have been a number of studies on efforts to combat stigma (Brown, Macintyre, & Trujillo, Citation2003; Heijnders & van der Meij, Citation2006) and leprosy-related stigma in particular (Benbow & Tamiru, Citation2001; Cross & Choudhary, Citation2005; Ebenso et al., Citation2007; Floyd-Richard & Gurung, Citation2000; Gershon & Srinivasan, Citation1992). The SARI project focuses on counselling, socio-economic development and contact. ‘Contact’ was selected because it has shown promise in other fields, in particular mental health and HIV and AIDS (Brown et al., Citation2003; Heijnders & van der Meij, Citation2006). Contact is described as ‘all interaction between the public and persons affected, with the specific objective to reduce stigmatising attitudes’ (Heijnders & van der Meij, Citation2006, p. 359). This interaction may be direct, for instance when a stigmatised person speaks to an individual or group, or indirect, most commonly through the use of a video (Brown et al., Citation2003).

Participatory video involves using a set of techniques with the aim of helping people to explore the issues they face and voice their concerns (Lunch & Lunch, Citation2006). Positive outcomes of participatory video include building confidence, fostering empowerment and enabling advocacy, activism and thus social change (Lunch & Lunch, Citation2006; Milne, Mitchell, & de Lange, Citation2012; Shaw & Robertson, Citation1997; White, Citation2003). Both the process of developing a video and the final product have their own purposes and potential outcomes or applications. This makes participatory video promising as part of a contact intervention to address the challenges of stigma both for people who experience it (the video makers) and for those who express it (video audience). In this paper, we focus on the video makers. The impact on the stigmatisers is also very important and will be addressed elsewhere (work in progress).

There is very limited experience of using participatory video as an approach to reducing stigma, and we are aware of only one study in the field of mental health (Buchanan & Murray, Citation2012). In the field of leprosy – the focus of this study – there are three foreseeable difficulties, which might also be relevant for other stigmatised conditions. First, people affected by leprosy sometimes choose to conceal their illness (Heijnders, Citation2004b; Kaur & Ramesh, Citation1994). This raises the question of their willingness to participate in the process. Second, physical limitations such as leprosy-related impairments to the hands might make it hard to use the equipment. Third, internalised stigma might influence individuals’ willingness to participate and group dynamics in general. This study aimed to demonstrate the impact of the participatory video process on video makers who are affected by leprosy and to increase understanding of how to deal with the foreseeable difficulties. We hope thereby to contribute to the practice of and research on reducing stigma and to broaden the applications of participatory video.

Stigma

The body of theory and research on stigma has been developed over 50 years since its original conceptualisation. Goffman (Citation1963) referred to stigma as an ‘attribute that is deeply discrediting’ (p. 3) and that reduces the bearer ‘from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one’ (p. 3). The usefulness of Goffman's conceptualisation for understanding health-related stigma has been questioned. For example, it is inappropriate in the context of cross-cultural research and its emphasis on social interactions to the exclusion of attention to structural social elements such as class, gender and ethnicity has also been highlighted (Scambler, Citation2006; Weiss, Ramakrishna, & Somma, Citation2006). New definitions and conceptualisations of health-related stigma have since been developed (Bos, Pryor, Reeder, & Stutterheim, Citation2013; Corrigan, Kerr, & Knudsen, Citation2005; Link & Phelan, Citation2001; Parker & Aggleton, Citation2003; Weiss et al., Citation2006). For instance, Link and Phelan (Citation2001) define stigma as the co-occurrence of five components – labelling, stereotyping, separation, status loss and discrimination – and underline the importance of power. Weiss (Citation2008) described different types of stigma prevalent among the stigmatised and stigmatisers, including internalised, anticipated and enacted stigma. The definitions of stigma vary, mainly because the concept has been applied to an array of circumstances and because research on stigma is multidisciplinary (Link & Phelan, Citation2001), which results in conceptual ambiguity. Recently, Staples (Citation2011) argued that stigma ‘can become a lazy shortcut for multiple “social aspects” of leprosy’ (p. 91) and Tal (Citation2012) even questioned whether it was time to retire the concept. Although these propositions make it tempting to reject the concept of stigma, the overall consensus is that it should not be disregarded. Staples (Citation2011) calls for more critical interrogation: bringing diverse disciplines together and subjecting ‘the experience of leprosy to more rigorous, ethnographic examination’ (p. 96).

Connecting the stages of participatory video to the levels of stigma reduction

Participatory video encompasses a wide variety of practices, purposes and philosophies. High, Singh, Petheram, and Nemes (Citation2012) state that it is a ‘mistake to treat participatory video as though it is unitary: as a single methodology, approach or movement’ (p. 45). Due to the action-oriented nature of participatory video, one of its more common applications is as a methodology for action–research (Mitchell, Milne, & de Lange, Citation2012). One way of looking at the participatory video process in action–research is through the three non-linear ‘stages’ identified by Shaw (Citation2012). Stage A is concerned with the interaction between participants (video makers), referred to as ‘opening in-between communication spaces’. Stage B is concerned with expression, reflection and building agency, during which participants share and reflect on their experiences and concerns, and perhaps reframe assumptions and build agency. Stage C is concerned with exercising this agency and beyond to what Shaw calls ‘social becoming’. The three stages, including the building blocks, are illustrated in . Shaw's work in particular draws attention to the gap between the potential and ideals of participatory video, and the reality of practice, and underlines the importance of acknowledging the possible tensions, limitations and constraints. The framework was built ‘for future critical investigation of actuality’ (p. 225). In this paper, we look at each stage of a participatory video process and use Shaw's building blocks as a guide to describe the impact on the participants.

Table 1. Stages and building blocks in a participatory video process.

We asked ourselves: How does participatory video affect stigma and at which level does the change – if any – take place? The five levels of stigma on which interventions to reduce it may operate are the ‘intrapersonal’, ‘interpersonal’, ‘community’, ‘organisational or institutional’ and ‘governmental or structural’ (Heijnders & van der Meij, Citation2006). illustrates these levels and shows what stigma-reduction interventions aim to achieve, such as increasing knowledge and self-esteem or establishing relationships.

Table 2. Stigma-reduction strategies at different levels.

Methods

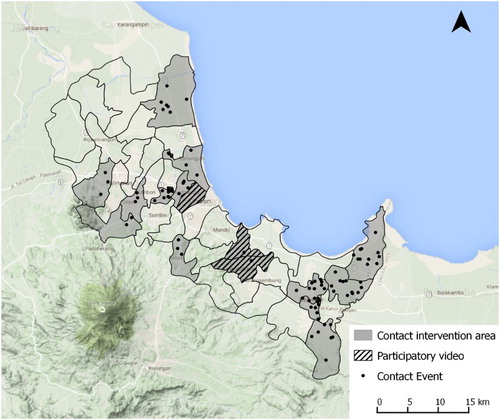

In 2011, the SARI team and stakeholders selected kabupaten Cirebon (Cirebon District) as the area of research and project implementation. Cirebon District is located in Indonesia on the north coast of West Java, bordering Central Java. It has a relatively high number of new leprosy cases each year and – according to national experts – more leprosy-related stigma than in other districts, and no other initiatives to address this. Administratively, Cirebon District consists of 40 kecamatan (sub-districts). This study looks at the processes of the making of two participatory videos. The first participatory process took place in Kedawung sub-district between May and August 2012. The SARI project research assistants selected this sub-district because of the relatively high number of new leprosy cases. After successfully screening the first video during ‘contact events’ in the villages of selected sub-districts in Cirebon District and a generally positive internal evaluation, the SARI team decided to organise the second participatory video process. The SARI project research assistants felt there were still many potentially damaging misconceptions in the community about leprosy-related impairments to be addressed. It was thought that a video made by people who have such impairments would bring added value to the events. The second process therefore took place in the sub-districts of Astana Japura and Lemang Abang, selected for similar reasons, from July 2013 to November 2013. All the participants in the second process had a leprosy-related impairment. In total, 91 ‘contact events’ in which the videos, and also comics, testimonies and an interactive presentation on leprosy, were part of the programme organised in Cirebon District. Not every contact event incorporated all of the methods; a selection was based on the available time, venue and interest of the audience. shows Cirebon District, the 3 sub-districts where the participatory videos were made and the 16 sub-districts where contact events were organised. A paper on the effect of these ‘contact events’ is in progress.

Figure 1. Sub-districts where participatory videos were made and contact events were organised (made with Quantum – Geographic Information System ).

The team responsible for the participatory video process comprised a Dutch researcher (first author) and nine local research assistants who were trained in social research, community-based rehabilitation, leprosy and counselling. The team was divided into two sub-teams, team A facilitated the first process and team B the second. The research assistants divided the four main roles – facilitator, networker, researcher and editor/technical support – among themselves.

The participatory video process started with training the research assistants. The ‘Insights into Participatory Video: Handbook for the Field’ by Lunch and Lunch (Bahasa Indonesia version) was used as a guideline (Citation2006). There was a meeting of all the research assistants and the first author to discuss the potential strengths and challenges in the project context.

The plan for the first process was to work with a group of about 6–10 people, heterogeneous in terms of sex, age and impairments. For the second video, all participants were to have a leprosy-related impairment and, as this is less common, the team agreed on a group size of four to six people. Criteria for participation were sufficient proficiency in Bahasa Indonesia, commitment to the process and living relatively near each other. The SARI project research assistants selected and approached potential participants affected by leprosy, in close collaboration with the leprosy workers at the puskesmas (community health centre). The research assistants met about 600 people affected by leprosy during the course of the project, who were asked whether they would like to join the SARI project's activities. Only those who had agreed or (newly diagnosed) persons recommended by the leprosy worker were approached.

The teams and participants jointly agreed on the aim of the video – to clarify public misconceptions about leprosy and reduce public stigma. The facilitators selected games and activities based on the needs of the group (including the ‘Significant Dates’Footnote1 exercise) from Lunch and Lunch (Citation2006) and allotted these to the sessions. The aim was to acquaint the participants with the equipment and with making a video. Minor changes were made in the selection of games and activities for the second participatory video process. During the sessions the participants’ filming skills were brought to a level that they considered sufficient. The participants selected interesting themes for the final video and made storyboards that showed what needed to be filmed, including testimonies and interviews. A research assistant edited the final videos, with input from the participants. Evaluation meetings to discuss the strengths, challenges and possible solutions were held with the research assistants after each video process.

The study drew on six qualitative methods: (i) semi-structured interviews with the participants before and after the process; (ii) informal discussions with participants during the process; (iii) (participant) observation, with a focus on the participants, the process and areas for improvement; (iv) photos and videos of the process; (v) notes of the initial and evaluation meetings with the research assistants and (vi) written reflections by the research assistants on challenges and opportunities, among other topics. Triangulation by using a range of methods helped to enhance validity. The interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim or comprehensively summarised with important quotes translated into English. NVivo was used for data management and analysis.

The relevant government offices granted ethical approval for the study. The participants gave their written consent. There were two forms: one before the start regarding the process and one at the end regarding the final product. The participants were compensated for lost earnings and made their own decisions about how to share or use this money.

Results

Introducing the participants

For both processes, the networkers visited 11 persons affected by leprosy (for the second only those with impairments) and invited them to join the process. Eight consented to do so for the first video and 4 for the second, while 10 declined. Reasons for declining were work obligations outside town, harvest season, unforeseen problems (fire) at the plantation, unexpected family situation that needed attention, old age and poor health, pregnancy, one mother's hesitations because her son was shy and a husband's denial of permission for his wife to participate. The participants represented a mix of age, sex, marital status, employment and level of impairment.

From initial interviews it became clear that leprosy influenced the lives of the participants in many ways. The three different types of stigma – internalised, perceived and enacted – emerged from the interviews. There were also themes such as the challenges posed by impairments and a range of responses – support versus exclusion – from family and community members. Some participants were still struggling with their leprosy (history) and/or impairments, whereas others had overcome them (see also Peters et al., Citation2013). The following quotes give some impression of leprosy-related perceptions and experiences in participants’ lives before the process started:

At that time many customers bought our yellow rice at school. But there was a gossip … that made that people did not buy our rice. But I never give up. … Even though the food was left over, next day I kept selling the food. The gossip came again, but I kept selling the food. … I sold my bicycle, my hens, I sold everything but I never give up, sir … if I had stopped that meant that I had lost. … Finally, I could sell the food. Things went back to normal. I think if I had given up at that time, I would not have been selling food anymore. (Man, aged 59)

I am the one who feels ashamed. My friends treat me as usual. They do not feel disgusted … . but I cannot help feeling ashamed. I am afraid they will avoid me. (Woman, aged 43)

When people are gathering and chatting, and I come over, those who do not like me will stride off. (Woman, aged 43)

I felt hopeless. If God had taken my life at that time, I would have accepted it gladly. (Man, aged 39)

All participants joined the participatory video process from beginning to end, selecting the locations of meetings and arranging their schedule. For the first process, there were 12 group sessions and 22 in the second. In general, the meetings were held at participants’ homes, apart from one meeting at SARI's office. The length of the sessions varied from an hour to a whole day. The two final videos told the stories that the makers wanted to tell the community, entitled ‘Pastikan badai sirna’ (‘Surely the storm has vanished’) and ‘Empat sahabat yang selalu berbagi’ (‘Four friends who always share’).

Impact on the participants

Stage A

Engaging participants. All participants were very engaged in the process. This was demonstrated by their high attendance, willingness to meet late at night and at the weekend, the food they brought to the meetings so they could eat together, spouses who joined and a small party organised by the first group. The participants emphasised what fun they had. One said, ‘I became a happy person during that time.'

Increasing individual confidence, capacity and sense of ‘can do’. Some participants were surprised that they had been asked to join, and one said, ‘people like me do not make things like that’. Throughout the process their confidence, capacity to handle the equipment, which they had often never used before, and communication skills all grew. Learning new things was stressful and demanding but also joyful:

I had a lot of fun. I gained a lot of experience. Really. I could even shoot someone climbing a tree. I was truly happy. (Man, aged 39)

I was happy, but I was also shaking because I had never done that [interviewing a leprosy officer] before … I was shaking like leaves but happy [laughs] (Woman, aged 26)

Establishing inclusive and collaborative group dynamics. There was a clear sense of togetherness that emerged between the group members and facilitators. Some participants joined because they were keen to meet their peers, with whom they did not have to worry about their condition and no longer felt alone. According to one participant the relationship both with peers and with the facilitators was important. For example, facilitators were not afraid of being associated with people affected by leprosy or of catching the disease:

I wanted to socialise with my friends [peers]. I wanted to know whether I was the only one suffering from leprosy or if there were others out there. It turned out that I was not the only one who is like this [showing his impaired hand]. (Man, aged 61)

At first, I felt so insecure, but the feeling is gone. … Maybe it is because … I also socialise with healthy … people. … This handsome young [research assistant] is willing to get along with someone like me [laughs] and … [this other research assistant] does not mind drinking from the same glass with me. (Man, aged 61)

Participants supported each other in multiple ways. At one point, the facilitators and participants heard that a fellow participant had been fired from his job. There had been a conflict between a participatory video meeting and the participant's work and he had chosen to attend the meeting instead of his job. Although surprised that this had happened, all group members and facilitators discussed and tried to solve the problem together. A few days later a new job was arranged. Another participant thought about leaving because her boyfriend was unhappy about her participating in the activity. Again group members gave support. In the end she decided to stay because she felt the experience was good for her. Another participant who had joined a self-care group initiative (at the community health centre) had learnt how to use a stone to take care of and prevent wounds, and brought a stone for another participant. Another participant encouraged another to continue the MDT treatment so that his then minor impairment would not worsen. Facilitators were surprised by the closeness between participants. One wrote:

The effect of making the participatory video is the proximity between the participants, a sense of caring, knowing each other better and the togetherness. This is a good first step for my friends who have had leprosy. (Reflection by research assistant)

Stage B

Motivating social dialogue focused on participants’ lives and concerns. There were dialogues about leprosy and experiences of having leprosy, sometimes stimulated by exercises such as the Significant Dates exercise and sometimes spontaneously. Simply sharing basic knowledge about leprosy was key. Several participants did know the basics about their illness.

Developing critically: group reflection and reframing. Some participants just had a fun time, made friends and gained new knowledge about the disease, but there the impact more or less stopped. For others, the elements of Stage B were important, whereas for one participant Stage C was most important. Two participants said that they found the Significant Dates exercise the most valuable as it helped them to reflect on their own lives and reframe their experiences by putting them into perspective. Three participants who displayed an exceptional spirit, commitment and attitude to life were role models for others:

I learn about perseverance from him [other participant]. Regardless his impaired condition, he keeps up his spirit, and his wife is very supportive. … It inspires me. He inspires me to do this and that … He does not feel insecure, neither does he worry that no one will buy his chips. (Man, aged 61)

Building agency: purpose. Group members became clearer about their purpose during the process. Some felt a desire to change community perspectives, increase knowledge and call for inclusion as shown by these quotes:

I want the community to change their opinion and attitude so that the affected people do not feel insecure. I hope community can accept us. Really. (Woman, aged 26)

I want people to know that regardless my imperfect physical state, I do not hide myself and keep doing what I can do. I want that people who watch the video see that people like me cannot do some work, on the contrary, I can do many kinds of work. (Man, aged 61)

I realised that there are many other people, in many areas who suffer from the same disease as I did. People who are isolated by the community. I was touched, and I was determined to share my knowledge about leprosy to these people. … That was the sole objective in my mind. … In the past, I did not even go out of my house because every time people saw me, they turned away from me. I felt ashamed of myself. I hope no more people will have such an experience. (Man, aged 39)

Stage C

Group communication action through video production. In various ways, the video production led to unplanned awareness-raising activities beyond the screening. The neighbours of one participant in the second process were concerned about the intentions of the SARI project and hence with his participation. He shared this with the group and proposed to organise a gathering to explain the aim of the video process and the SARI project to his family, neighbours and friends. The research assistants and group members agreed. Contrary to what the research assistants expected, more than 25 neighbours and friends came to the participant's home. According to the research assistants, the neighbours listened ‘enthusiastically’ to the explanation, supported the video process and even offered their help. Other participants realised that it would be worth organising a similar gathering with their own neighbours and one was set up for each of the four members of this group.

Social influence: showing the video in wider forums. The SARI project screened and discussed the video content during 91 village ‘contact events’, attended by over 4440 community members (paper in progress). One participant suggested helping to organise the contact events by giving testimonies. After the first event he shared his initial doubts, but also said that he felt happy:

This is the first time I delivered a testimony in front of many people. I was rather doubtful at first whether I can do it or not, but after the testimony when people started raising questions, I felt happy. I want to keep giving testimonials. (Man, aged 39)

New or restored social identity. First, the video process had an impressive impact on the self-esteem of several participants. Sometimes participants said that the internalised stigma disappeared, some others said it had lessened:

I know more about leprosy now, and if you are asking me about my insecurity, I think there is only a very small part of it left in me. The knowledge I have recently gained made me more confident. I am positive that I have recovered. (Man, aged 21)

After video activity, I feel full of spirit. When people say something bad, I do not let it bother me. We have our private life. As long as I do not cause trouble for other people, I have nothing to worry. [laughs] … I have recovered now, so let people talk! I feel free these days. Nobody stops me from going here and there or from doing this or that. (Woman, aged 26)

Second, some participants describe the normalised relationship with their neighbours:

I do not feel shy towards my neighbours any more. I chat with my neighbours and friends. Things have gone back to normal. (Woman, aged 26)

When someone talked evil about leprosy or an affected person, I lectured him/her even in front of many other people. (Man, aged 39Footnote2)

Third, what stands out in terms of social identity is the renewed focus on others. One participant said that before the process he cared only about his family and his business and that now he cares about the community again. Others had similar experiences. One participant offered to volunteer and help to start up a self-care group in a new area; two participants found new potential leprosy cases and directed them to the community health centre.

Understanding difficulties

Concealment

Even before the process began, the research assistants raised the key challenge of concealment. The teams realised the need to go through an entire process in order to understand how it was influenced by concealment. Most of the participants had disclosed their illness (or at least others knew about it), but a few had not.

One participant in the first process had partially disclosed his illness but had experienced several difficulties. On the one hand, he really enjoyed participating in the process. More than all of the other participants he most seemed to enjoy handling the camera and shooting film and it made him proud. On the other hand, there was the constant worry. He was afraid that acquaintances would learn about his own leprosy history and would then avoid him. He decided not to appear in the final video, but remained involved in the sessions.

Another participant in the second process decided halfway through that she wanted to inform her neighbours about her illness, partly because she was afraid they would in any case find out. She discussed this with the research assistants and co-participants. A gathering was organised where the participant told them, the first final video was broadcast and basic information was shared about leprosy, such as the cause and the fact that leprosy is no longer infectious once medication is taken. The participant said that her neighbours subsequently treated her normally and that nobody talked ‘bad’ about her, but rather that neighbours were interested and asked about the progress of making the video.

The final videos tell the stories of seven participants. Most were happy or even eager to screen the video in the area where they live. For 4 of the 12 participants, however, screening in their own village or sub-district was a step too far. Some were worried about the screening and possible responses of the audience for themselves (n = 2), for other participants (n = 1) or for their family (n = 1). For example, a young woman who appears in the video did not object to broadcasting it, but another, an older man, objected to her being in the video. He was worried about her future as a labourer and as an unmarried woman. He said: ‘her future is still long’. One woman was embarrassed not because of her illness but because she was not fluent in Bahasa Indonesia. The next quote illustrates the anxiety felt by one participant regarding the possible response of relatives:

I do not mind the video being played anywhere because people have known my real condition. There is nothing I can do about it. However, I am afraid that my husband and other relatives object to the idea. I want people to know about this, but I am worried about my family's reaction. (Woman, aged 43)

Due to concerns about disclosure expressed by four participants, the participants asked the SARI team not to broadcast the videos in their own sub-districts. As a result, the participants were unable to benefit from the potential impact of screening the video in their neighbourhood. For one participant the screening element was very important, perhaps even his sole reason for participating, but his wish could not be realised. Screening the videos outside their own sub-district was not a problem and was in fact encouraged by the video makers. Participants’ ownership of the finished videos is a cornerstone of most participatory processes. To prevent involuntary disclosure by screening the videos in the participants’ sub-districts the project decided not to distribute the videos to the participants. The videos are in the hands of a local disabled people's organisation, Forum Komunikasi Difabel Cirebon (FKDC), where some of the SARI project research assistants work and to which some of the video makers belong. Any questions regarding screening and distribution of the videos will go through FKDC.

Physical limitations

Some participants were worried about the impact of making the video on their physical condition. For those whose hands were impaired, it was challenging to learn to operate the devices, in particular zooming and keeping the camcorder stable. There was a need for more than the anticipated number of sessions to acquire the basic skills. Participants and the team jointly found creative solutions, such as an enlarged pin in the tripod to make it easier for the participants to operate the device unassisted. Although the process was challenging and time-consuming, ultimately all participants could use the equipment:

My problem is my physical limitation. I felt tired quickly, but thanks to God, I could stay in the process until the end. I was afraid of getting sick because of the activity because I usually get sick when I am too tired. (Man, aged 61)

You see the condition of my arms and hand. It is not easy to shoot with this kind of arm. However, everything is possible if we are willing to learn. I am happy because I finally could do it. (Man, aged 39)

Behaviour caused by internalised stigma

Most participants seemed reasonably confident during the process and only a few felt insecure and ashamed. As expected, internalised stigma played a role. Some participants needed a bit more time to get familiar with the activities and support from the facilitators:

At first, I felt insecure and ashamed. I cannot tell you how, but that was what I felt … After I knew the activity better, I felt comfortable doing it. I could meet many people and we could share with each other. (Man, aged 21)

Discussion

This paper has explored the impact of a participatory video process on participants affected by leprosy. It focused on three difficulties: concealment, physical limitations and behaviour caused by internalised stigma. The stages outlined by Shaw (Citation2012) were helpful in analysing the impact on the participants. We made two changes in the names of the building blocks; individual rather than collective agency seemed more relevant to this study and a new or restored ‘social identity’ was chosen rather than ‘social becoming’, which was a better fit with the context of stigma. In terms of reducing stigma and the levels identified by Heijnders and van der Meij (Citation2006), the impacts described in Stages A and B operate at the intrapersonal level, whereas the impacts in Stage C operate at the ‘interpersonal’ and ‘community’ levels. Although not explored in this project, it is also possible to broadcast the video at organisational, institutional and governmental levels, making it potentially a multi-level stigma-reduction strategy.

This paper also showed that participatory video is a process from which the participants can benefit in many ways. The diversity of impacts also makes it complex and difficult to pinpoint what exactly contributes to reducing stigma and for whom. This corresponds with the experience of Blazek and Hraňová (Citation2012) who wrote that ‘our experience shows that participatory video is an immensely complex activity because of the range of relationships and positionalities that various actors bring to the collaborative process’ (p. 164). Similar to Buchanan and Murray (Citation2012), the suggestion of Howarth (Citation2006) is relevant and demonstrated ‘in action’:

Howarth (Citation2006) has suggested that by coming together in dialogue, debate and critique, members of a stigmatised group can become aware of themselves as agents not objects. She emphasised that alone the individual cannot develop the confidence and emotional strength to challenge stigma but can do so in combination with others. (Buchanan and Murray, Citation2012, p. 41)

Concealment was a key difficulty. It put some participants in a difficult position, balancing their desire to participate with anxiety about disclosure and possible negative effects. Ultimately, four participants objected to screening the final video in their own sub-district, which created the challenges described. The issue of concealment is also prominent in Buchanan and Murray (Citation2012), but is reflected only in a reluctance to participate. We cannot say that participants in our study were reluctant to participate since the reasons given for declining participation seem very common. In future initiatives, it may be possible to reduce the risk of negative effects due to disclosure, for instance by meeting and filming outside the area in which the participants live. It might also be possible to encourage participants to prepare a video that they would all be content to screen in their own area – but this might undermine the benefit of all participants being able to participate in whatever way they wish without having to consider the aspect of broadcasting. Exploring ways to film anonymously might be interesting, but should be addressed in games and activities early in the participatory video process. Concealment remains a major challenge and should be carefully considered in similar initiatives.

We are aware of two other studies where people who are labelled ‘disabled' – physically or mentally – made a participatory video: Buchanan and Murray's study on mental health (Citation2012) and Capstick's study on dementia (Citation2012). Due to their impairments, participants in this study needed extra time to become familiar with the equipment, but they all succeeded, which gave a real confidence boost to each participant. In this way, an initial challenge became an opportunity. It is important to be aware of the participants’ physical condition. A slower pace and flexibility to adapt the process to the participants’ needs and desires are even more important than usual. We agree with Capstick (Citation2012) that more attention and reflection is needed on how participatory video can be made more inclusive and accessible for people who are labelled ‘disabled’.

The challenge of involving people who have internalised stigma is, to our knowledge, not described elsewhere. The potential to increase self-esteem through the participatory video process is described by others (Buchanan & Murray, Citation2012; Lunch & Lunch, Citation2006; Shaw & Robertson, Citation1997). In our study, internalised stigma was a minor but relevant challenge only for a few participants. Solutions included allowing more time and having well-trained facilitators with a thorough understanding of leprosy and counselling skills. In addition, the local facilitators allowed us to benefit from:

Research being led by community researchers meant that they could navigate the cultural norms and rules so as to create relatively safe spaces for community members to participate and reflect on their experiences. (Wheeler, Citation2009 p. 14)

Aspects that were not addressed in depth here include (i) high expectations, responsibility and dependence on the research assistants (as one research assistant said, ‘what if our spirit had dropped?’); (ii) the dynamics between participants and research assistants; (iii) how to foster an environment to make a long-term or sustainable impact on reducing stigma; (iv) illiteracy, unfamiliarity and practical challenges with some exercises in the handbook (something simple as throwing a die was difficult for those with hand impairments) and (v) a more participatory editing process. It is also important to note that stigma-reduction interventions can, inadvertently, foster stigma. Interventions’ emphasis on leprosy and associated stigma could temporarily reinforce or amplify them. There were no indications that this happened during these processes, but it is important to be aware of the possibility, look for any signs of it and take appropriate action when it occurs. Heijnders and van der Meij also emphasised this danger (Citation2006).

Participatory video as a stigma-reduction strategy is a new field and we therefore have many ideas for further research and practice. First and most important is maximising the communication potential and understanding of the impact of screening the video on community-level stigma. Mistry, Bignante, and Berardi (Citation2014) emphasise the importance of motivation and say that the surfacing of individuals’ motivations should be stimulated in order to ensure better outcomes. In retrospect, this is relevant in our context and seems worth exploring in the future. It might also be worth studying how stigmatised identities intersect with other aspects of identity (such as sex, age or socio-economic status) and how this influences group (power) dynamics. In addition, it would be interesting to see specific groups develop participatory videos, such as children, adolescents, family members, those cured of but with reactions to leprosy, and others including newly diagnosed persons, health workers, family members and policy-makers at the Ministry of Health. In particular, we would encourage a greater involvement of participants in the organisation of screening activities. In our case, there was some involvement, but perhaps less than might have been desirable, due to overall project objectives and time limitations.

Conclusion

Despite some important challenges, participatory video has the potential to address stigma at least at three levels – intrapersonal, interpersonal and community – and possibly more. This is all very promising, but the proof of its impact will be whether demonstrable effects on community stigma are achieved by screenings of the videos. The intervention seems easily replicable and thus scalable. Gradual implementation elsewhere is recommended provided there are well-trained facilitators and with an emphasis on learning and reflection so that the approach can better respond to the challenges posed by concealment, the participants’ physical condition and group dynamics.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants and research assistants of the SARI project. We thank Mike Powell and Deborah Eade for their comments on an earlier draft. We also express our gratitude to the District Health Office in Cirebon, the West Java Provincial Health Office and the Sub-Directorate for Leprosy and Yaws of the Ministry of Health for facilitating this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Exercise described in the handbook (Lunch & Lunch, Citation2006) where participants get to know each other by sharing life events, in our case some related to leprosy.

2. This participant also joined the SARI project's counselling intervention.

References

- Atre, S., Kudale, A., Morankar, S., Gosoniu, D., & Weiss, M. G. (2009). Gender and community views of stigma and tuberculosis in rural Maharashtra, India. Global Public Health, 6(1), 56–71. doi:10.1080/17441690903334240

- Benbow, C., & Tamiru, T. (2001). The experience of self-care groups with people affected by leprosy: ALERT, Ethiopia. Leprosy Review, 72(3), 311–321. Retrieved from http://www.ilep.org.uk/fileadmin/uploads/Documents/Infolep_Documents/Leprosy_Articles/Articles_2001/BENBOW2001.pdf doi: 10.5935/0305-7518.20010038

- Blazek, M., & Hraňová, P. (2012). Emerging relationships and diverse motivations and benefits in participatory video with young people. Children's Geographies, 10(2), 151–168. doi:10.1080/14733285.2012.667917

- Bos, A. E. R., Pryor, J. B., Reeder, G. D., & Stutterheim, S. E. (2013). Stigma: Advances in theory and research. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 35(1), 1–9. doi:10.1080/01973533.2012.746147

- Brown, L., Macintyre, K., & Trujillo, L. (2003). Interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma: What have we learned? AIDS Education and Prevention, 15(1), 49–69. doi:10.1521/aeap.15.1.49.23844

- Buchanan, A., & Murray, M. (2012). Using participatory video to challenge the stigma of mental illness: A case study. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 14(1), 35–43. doi:10.1080/14623730.2012.673894

- Capstick, A. (2012). Participatory video and situated ethics: Avoiding disablism. In E.-J. Milne, C. Mitchell, & N. de Lange (Eds.), Handbook of participatory video (pp. 269–282). Plymouth: AltaMira Press.

- Corrigan, P. W., Kerr, A., & Knudsen, L. (2005). The stigma of mental illness: Explanatory models and methods for change. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 11(3), 179–190. doi:10.1016/j.appsy.2005.07.001

- Cross, H., & Choudhary, R. (2005). STEP: An intervention to address the issue of stigma related to leprosy in Southern Nepal. Leprosy Review, 76(4), 316–324.

- Ebenso, B., Fashona, A., Ayuba, M., Idah, M., Adeyemi, G., & S-Fada, S. (2007). Impact of socio-economic rehabilitation on leprosy stigma in Northern Nigeria: Findings of a retrospective study. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal, 18(2), 98–119.

- Floyd-Richard, M., & Gurung, S. (2000). Stigma reduction through group counselling of persons affected by leprosy – a pilot study. Leprosy Review, 71(4), 499–504. doi: 10.5935/0305-7518.20000052

- Gershon, W., & Srinivasan, G. R. (1992). Community-based rehabilitation: An evaluation study. Leprosy Review, 63(1), 51–59. doi: 10.5935/0305-7518.19920009

- Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- Heijnders, M., & van der Meij, S. (2006). The fight against stigma: An overview of stigma-reduction strategies and interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 11(3), 353–363. doi:10.1080/13548500600595327

- Heijnders, M. L. (2004a). Experiencing leprosy: Perceiving and coping with leprosy and its treatment. A qualitative study conducted in Nepal. Leprosy Review, 75(4), 327–337.

- Heijnders, M. L. (2004b). The dynamics of stigma in leprosy. International Journal of Leprosy and Other Mycobacterial Diseases, 72(4), 437–447. doi:10.1489/1544-581X(2004)72<437:TDOSIL>2.0.CO;2

- High, C., Singh, N., Petheram, L., & Nemes, G. (2012). Defining participatory video from practice. In E.-J. Milne, C. Mitchell, & N. de Lange (Eds.), Handbook of participatory video (pp. 35–48). Plymouth: AltaMira Press.

- Howarth, C. (2006). Race as stigma: Positioning the stigmatized as agents, not objects. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 16, 442–451. doi:10.1002/casp.898

- Kaur, H., & Ramesh, V. (1994). Social problems of women leprosy patients: A study conducted at 2 urban leprosy centres in Delhi. Leprosy Review, 4(65), 361–375.

- Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 363–385. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363

- Lunch, C., & Lunch, N. (2006). Insights into participatory video: A handbook for the field. Oxford: InsightShare.

- Milne, E.-J., Mitchell, C., & de Lange, N. (Eds.). (2012). Handbook of participatory video. Plymouth: AltaMira Press.

- Ministry of Health Indonesia. (2012). Annual Leprosy Statistics Indonesia 2011. Jakarta: Author.

- Mistry, J., Bignante, E., & Berardi, A. (2014). Why are we doing it? Exploring participant motivations within a participatory video project. Area. doi:10.1111/area.12105

- Mitchell, C., Milne, E.-J., & de Lange, N. (2012). Introduction. In E.-J. Milne, C. Mitchell, & N. de Lange (Eds.), Handbook of participatory video (pp. 1–18). Plymouth: AltaMira Press.

- Nicholls, P. G., Wiens, C., & Smith, W. C. S. (2003). Delay in presentation in the context of local knowledge and attitude towards leprosy – the results of qualitative fieldwork in Paraguay. International Journal of Leprosy and Other Mycobacterial Diseases, 71(3), 198–209. doi: 10.1489/1544-581X(2003)71<198:DIPITC>2.0.CO;2

- Parker, R., & Aggleton, P. (2003). HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: A conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science & Medicine, 57(1), 13–24. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00304-0

- Person, B., Bartholomew, L. K., Gyapong, M., Addiss, D. G., & van den Borne, B. (2009). Health-related stigma among women with lymphatic filariasis from the Dominican Republic and Ghana. Social Science & Medicine, 68(1), 30–38. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.040

- Peters, R. M. H., Dadun, L. M., Miranda-Galarza, B., van Brakel, W. H., Zweekhorst, M. B. M., Damayanti R., … Irwanto. (2013). The meaning of leprosy and everyday experiences: An exploration in Cirebon, Indonesia. Journal of Tropical Medicine. doi:10.1155/2013/507034

- Rafferty, J. (2005). Curing the stigma of leprosy. Leprosy Review, 76, 119–126.

- Root, R. (2010). Situating experiences of HIV-related stigma in Swaziland. Global Public Health, 5(5), 523–538. doi:10.1080/17441690903207156

- Rüsch, N., Angermeyer, M. C., & Corrigan, P. W. (2005). Mental illness stigma: Concepts, consequences, and initiatives to reduce stigma. European Psychiatry: The Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 20(8), 529–539. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.04.004

- Scambler, G. (2006). Sociology, social structure and health-related stigma. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 11(3), 288–295. doi:10.1080/13548500600595103

- Shaw, J. (2012). Interrogating the gap between the ideals and practice reality of participatory video. In E.-J. Milne, C. Mitchell, & N. de Lange (Eds.), Handbook of participatory video (pp. 225–239). Plymouth: AltaMira Press.

- Shaw, J., & Robertson, C. (1997). Participatory video: A practical approach to using video creatively in group development work. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Staples, J. (2011). Interrogating leprosy ‘stigma’: Why qualitative insights are vital. Leprosy Review, 82(2), 91–97.

- Tal, A. (2012). Is it time to retire the term stigma? Stigma Research and Action, 2(2), 49–50. doi:10.5463/SRA.v1i1.18

- Weiss, M. G. (2008). Stigma and the social burden of neglected tropical diseases. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 2(5), 237. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000237

- Weiss, M. G., Ramakrishna, J., & Somma, D. (2006). Health-related stigma: Rethinking concepts and interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 11(3), 277–287. doi:10.1080/13548500600595053

- Wheeler, J. (2009). ‘The life that we don't want’: Using participatory video in researching violence. IDS Bulletin, 40(3), 10–18. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.2009.00033.x

- White, S. A. (2003). Participatory video: Images that transform and empower. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- WHO. (2014). Global leprosy update, 2013; reducing disease burden. Weekly Epidemiological Record, 89(36), 389–400.