ABSTRACT

Forcible displacement has reached unprecedented levels, with more refugees and internally displaced people reported since comprehensive statistics have been collected. The rising numbers of refugees requiring health services, the protracted nature of modern displacement, and the changing demographics of refugee populations have created compelling new health needs and challenges. In addition to the risk of malnutrition, infectious diseases and exposure to the elements attendant upon conflict and the breakdown of public health systems, many displaced people now require continuity care for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, asthma, cancer, and mental health, as well as maternal and child health services. In some regions, most refugee health services need to be provided in dispersed settings within host communities, rather than in traditional refugee camps, and the number of refugees suffering protracted displacement is growing rapidly. These realities highlight a significant disconnect between the health needs of twenty-first century refugees, and the global systems that have been established to address them. The global response to the HIV epidemic offers lessons about ways to support continuity care for chronic conditions during complex emergencies and may provide important blueprints as the global community struggles to redesign refugee health services.

Introduction

Forcible displacement has reached unprecedented global levels, with more refugees and internally displaced people reported since comprehensive statistics have been collected. Recent numbers are driven by conflicts in Syria, Iraq, South Sudan, and Ukraine, but war, conflict, and human rights violations are causing internal displacement and cross-border refugees on every continent (United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees [UNHCR], Citation2015). The Middle East is a displacement epicentre, with more than 4.8 million Syrian refugees straining the socio-economic absorptive capacity of Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey, and other neighbouring countries. This ongoing crisis has critical health implications for Syria and its neighbours; it also highlights broader issues about changing health needs in complex and protracted emergencies worldwide.

While relief agencies and health organisations have traditionally largely focused on the prevention of infectious disease, treatment of acute illness, and provision of reproductive health services, all essential, the health needs of displaced people have expanded in recent years, reflecting changes in refugees’ countries of origin and in the burden of disease in these countries. Although chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancers, and chronic lung disease are burdens for refugees and displaced people worldwide, they are particularly important causes of ill health in refugees from middle-income countries, such as Syria, Iraq, and Ukraine.

In addition to this changing burden of disease, today’s refugees are often displaced for longer periods of time; three-quarters live in protracted refugee situations of five years or more, increasing their need for chronic health services (US Department of State, Citation2015). Another important change is that in some regions, refuges increasingly live within host communities rather than in camp settings, further complicating the provision of health services. For example, only 11% of Syrian refugees in the Middle East and Turkey are currently living in refugee camps.

The challenge of providing services for chronic illness in the context of displacement is a daunting one, given that a key element of effective care for NCDs is continuity – the need to deliver coordinated services over time. But evidence from HIV programmes shows that continuity care can be delivered in challenging settings – including in complex humanitarian emergencies – and suggests key priorities for NCD services for forcibly displaced people.

Burden of NCDs amongst Syrian refugees

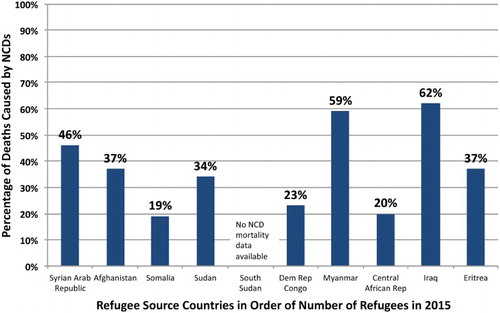

The 10 countries identified by the United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees (UNHCR) as the largest source of refugees in 2015 all have significant NCD burdens, with NCDs accounting for 19–62% of total mortality () and with prevalence of high blood pressure ranging from 23% to 32% amongst adults (World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2015). A systematic review in 2014 found high rates of NCDs amongst urban refugees worldwide (Amara & Aljunid, Citation2014) and a 2012 study of diverse refugees arriving in the U.S. found that 51% of adults had at least one chronic NCD and 9.5% had three or more (Yun et al., Citation2012). Forced migration due to conflict is associated with somewhat higher levels of mental health disorders (Porter & Haslam, Citation2005), although resilience amongst refugees is also widely noted (Siriwardhana, Ali, Roberts, & Stewart, Citation2014).

Figure 1. Percent of total deaths caused by non-communicable diseases in the largest source countries of refugees in 2014 (Adapted from: WHO NCD Country Profiles and UNHCR Citation2015).

Cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancers, and chronic lung disease were the leading cause of death in Syria prior to the war (Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation [IHME], Citation2015) and recent facility-based and community-based surveys confirm a significant prevalence of NCDs amongst Syrian refugees. In 2013, a review by UNHCR found the primary reasons for Syrian refugees to seek health care were diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and chronic lung disease (UNHCR, Citation2013). A cross-sectional survey of 1550 Syrian refugees in Jordan found that more than half of refugee households had a member with at least one NCD; hypertension, arthritis, diabetes, and chronic respiratory disease were the most common examples (Doocey et al., Citation2015). Similarly, a recent study of 1400 Syrian refugees in Lebanon showed that 50% of households reported the presence of hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, or arthritis in one or more household members (Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health and Medicins du Monde, Citation2015). A smaller study of older Syrian refugees in Lebanon found that 60% had hypertension, 47% had diabetes, and 30% had heart disease (Strong, Varady, Chahda, Doocy, & Burnham, Citation2015). Additionally, in Tripoli and the Bekaa Valley in Lebanon, as well as in the Domiz refugee camp in northern Iraq, Médecins Sans Frontières conducted more than 17,900 consultations for displaced Syrians with chronic diseases in 2013 alone (Médecins Sans Frontières, Citation2014).

Available services and systems for refugees

With few exceptions, the health systems and services currently available to refugees were developed more than a half-century ago, and were designed for acute emergencies in lower income countries. UNHCR was established in 1950 with a mandate to safeguard the rights and well-being of refugees worldwide. The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees (UNRWA) was founded in 1949, and now provides assistance to five million registered Palestinian refugees.

UNHCR advocates for free essential health services, which it defines as key primary health care services, emergency services, childhood vaccines, antenatal and delivery care, and care for communicable diseases such as tuberculosis. The agency and its partners provide primary health care and some secondary health services to registered refugees in Jordan and Lebanon, but secondary and tertiary care generally include co-payment requirements which may be unaffordable to refugees. In Turkey, registered Syrians officially have access to the same health services as the general population, largely financed by the Turkish government with some support from external donors. In practice, however, fewer than 50% of Syrians in Turkey are thought to be registered, making it more difficult for them to access health services.

Adapting its systems to meet the needs of Palestinians, who have been displaced for decades, UNRWA provides selected NCD services to these refugees, including routine screening for diabetes and hypertension at UNRWA-supported primary health centres, where nearly 200,000 people with the two conditions were receiving care and treatment by end-2013 (Shahin, Kapur, & Seita, Citation2015). UNRWA’s Family Health Team approach enables family-focused services including NCD prevention, management, and treatment. However, a recent cross-sectional study at UNRWA's 32 largest primary health care centres in Gaza, Jordan, Lebanon, and the West Bank noted that only 28% of diabetic patients had well-controlled blood sugar and blood pressure, indicating ongoing challenges (Shahin, Kapur, Khader et al., Citation2015).

Chronic care for refugees and displaced persons: lessons from HIV

Successful management of chronic diseases requires coordination of multidisciplinary services over time as well as the effective engagement and empowerment of patients to self-manage illness on an ongoing basis. Challenging in the best of circumstances, the delivery of continuity care is especially difficult for persons who are mobile, unstably housed, psychologically stressed, and lacking health coverage, characteristics typical of many refugees. Over the past 15 years, HIV programmes have amassed substantial experience delivering effective chronic care to populations with these challenges, in both resource-rich and resource-poor settings. In addition, HIV treatment has been successfully provided to refugees and internally displaced people; a 2014 review noted that 87–99% of forced migrants with HIV had achieved at least 95% adherence and positive treatment outcomes (Mendelsohn, Spiegel, Schilperoord, Cornier, & Ross, Citation2014). With the appropriate support, HIV treatment outcomes for forced migrants can be similar to that of the host community (Mendelsohn, Schilperoord et al., Citation2014).

Key lessons from HIV programmes () include the importance of using an evidence-based public health approach to service delivery, including simplified standardised treatment regimens, streamlined clinical and laboratory monitoring, and an intensive focus on patient education, engagement, and empowerment via the use of counsellors, outreach workers, and peer educators (Rabkin & El-Sadr, Citation2011). The use of such multidisciplinary teams would assist providers to meet the complex needs of refugees, and enable more effective linkages between facility- and community-based care. As HIV programmes have shown, innovative approaches, such as community-based care, and community treatment groups provide flexibility and contextually appropriate services while decreasing reliance on facility-based health workers (Holmes & Sanne, Citation2015).

Table 1. Lessons from HIV.

There are promising data on the use of mobile phones and text reminders to support retention in HIV treatment (Horvath, Azman, Kennedy, & Rutherford, Citation2012) and on the use of mobile clinics and electronic medical records to support displaced HIV patients during emergencies (Goodrich et al., Citation2013). In the case of forced migrants, cloud-based health records accessed via mobile phone applications could mitigate the challenges of maintaining medical information and test results while in transit, although it will be important to identify and address issues of privacy and security.

Other critical lessons from HIV programmes include the importance of examining health worker roles, and addressing licensing and regulatory barriers to task-shifting and health workforce innovation. In the case of HIV, these innovations have largely focused on enabling nurses and other non-physician clinicians to prescribe and monitor HIV treatment – adaptations that will be equally useful in the case of NCDs. Given the scarcity of Arabic-speaking clinicians in Turkey and European host countries, an additional priority may be finding creative ways to enable refugee health workers – for example, Syrian doctors and nurses – to swiftly return to practice even prior to formal resettlement.

Finally, the scale-up of HIV programmes in resource-limited settings has demonstrated the need for global solidarity and support, both for patients in need of health services and for the under-resourced health systems grappling with providing novel and complex health services to burgeoning numbers of patients in extremely challenging circumstances. Unfortunately, funding for UNHCR’s 2016 Middle East Regional Refugee and Resilience plan only reached 14% as of March 2016 (United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees, Citation2016). It will be necessary to reproduce the successful advocacy that led to the Global Fund for AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and the US President’s Emergency Fund for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) to support refugee health services. Including the issue of refugees and forced migrants in deliberations about Universal Health Coverage may also be a productive approach in some regions.

Gaps and opportunities

The international agencies tasked with care and support of refugees and internally displaced people face ever-increasing needs while experiencing substantial funding shortfalls. Host country health systems and their financial capacity are also strained, as they themselves often have rudimentary public sector NCD services. But the changing health needs of twenty-first century refugees require a reconceptualisation of the global frameworks, policies, and systems designed for their support, with attention to new challenges, such as chronic diseases, that may seem to fall between the mandates of emergency responders and development organisations. The growing burden of NCDs in both resource-rich and resource-poor countries, the extended timeframe of modern-day displacement, and the need for health care outside of refugee camp settings are imperatives that compel new thinking and new policies. The response to the HIV epidemic offers lessons about ways to support continuity care for chronic conditions during complex emergencies and may provide important blueprints as the global community struggles to redesign refugee health services.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Amara, A. H., & Aljunid, S. M. (2014). Noncommunicable diseases among urban refugees and asylum-seekers in developing countries: A neglected health need. Globalization and Health, 10(24), 1–14.

- Doocey, S., Lyles, E., Roberton, T., Akhu-Zahyea, L., Oweis, A., & Burnham, G. (2015, October 31). Prevalence and care-seeking for chronic diseases among Syrian refugees in Jordan. BMC Public Health, 15, 1097. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-2429-3

- Goodrich, S., Ndege, S., Kimaiyo, S., Some, H., Wachira, J., Braitstein P., … Wools-Kaloustian, K. (2013). Delivery of HIV care during the 2007 post-election crisis in Kenya: a case study analyzing the response of the academic model providing access to healthcare (AMPATH) program. Conflict and Health, 7(25). doi:10.1186/1752-1505-7-25

- Holmes, C. B., & Sanne, I. (2015). Changing models of care to improve progression through the HIV treatment cascade in different populations. Current Opinion in HIV AIDS, 10(6), 447–450. doi:10.1097/COH.0000000000000194

- Horvath, T., Azman, H., Kennedy, G. E., & Rutherford, G. W. (2012). Mobile phone text messaging for promoting adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (3). Article no. CD009756. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009756

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. (2015). Global burden of disease data visualization. Retrieved March 31, 2016, from http://www.healthdata.org/data-visualization/gbd-compare

- Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health and Médicins du Monde. (2015). Syrian refugee and affected host population health access survey in Lebanon. Retrieved March 31, 2016, from https://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/download.php?id=9550

- Mendelsohn, J. B., Schilperoord, M., Spiegel, P., Balasundaram, S., Radhakrishnan, A., Lee, C. K., … Ross, D. A. (2014). Is forced migration a barrier to treatment success? Similar HIV treatment outcomes among refugees and a surrounding host community in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. AIDS and Behavior, 18(2), 323–334. doi:10.1007/s10461-013-0494-0

- Mendelsohn, J. B., Spiegel, P., Schilperoord, M., Cornier, N., & Ross, D. A. (2014). Antiretroviral therapy for refugees and internally displaced persons: A call for equity. PLoS Medicine, 11(6), e1001643. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001643

- Médecins Sans Frontières. (2014). Retrieved March 31, 2016, from http://www.msf.org/article/lebanon-treating-chronic-diseases-among-syrian-refugees-priority-msf

- Porter, M., & Haslam, N. (2005). Predisplacement and postdisplacement factors associated with mental health of refugees and internally displaced persons: A meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), 294(5), 602–612. PMID: 16077055. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.602

- Rabkin, M., & El-Sadr, W. (2011). Why reinvent the wheel? Leveraging the lessons of HIV scale-up to confront non-communicable diseases. Global Public Health, 6(3), 247–256. PMID: 21390970. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.552068

- Shahin, Y., Kupur, A., Khader, A., Zeidan, W., Harries, A. D., Nerup, J., … Seita, A. (2015). Clinical audit on the provision of diabetes care in the primary care setting by UNRWA. Journal of Diabetes Mellitus, 5(1). doi:10.4236/jdm.2015.51002

- Shahin, Y., Kapur, A., & Seita, A. (2015). Diabetes care in refugee camps: The experience of UNRWA. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2015.01.035

- Siriwardhana, C., Ali, S. S., Roberts, B., & Stewart, R. (2014). A systematic review of resilience and mental health outcomes of conflict-driven adult forced migrants. Conflict and Health, 8(13). doi:10.1186/1752-1505-8-13

- Strong, J., Varady, C., Chahda, N., Doocy, S., & Burnham, G. (2015). Health status and health needs of older refugees from Syria in Lebanon. Conflict and Health, 9(12). doi:10.1186/s13031-014-0029-y

- United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees. 3RP funding update 2016. (2016, March 14). Retrieved March 31, 2016, from http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/regional.php

- United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees. (2013). UNHCR inter-agency regional response for Syrian refugees: Health and nutrition bulleting issue No. 11, October 2013. Retrieved March 31, 2016, from data.UNHCR.org

- United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees. (2015). Mid-year trends 2015. December 2015, UNHCR, Geneva. Retrieved March 31, 2016, from http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/home/opendocPDFViewer.html?docid=56701b969&query=mid%20year%20trends

- US Department of State website. (2015). Protracted refugee situations. Retrieved March 31, 2016, from http://www.state.gov/j/prm/policyissues/issues/protracted/index.htm

- World Health Organization. (2015). Non-communicable disease country profiles. Retrieved March 31, 2016, from http://www.who.int/nmh/countries/en/

- Yun, K., Hebrank, K., Graber, L.K., Sullivan, M.-C., Chen, I., & Gupta, J. (2012). High prevalence of chronic non-communicable conditions among adult refugees. Journal of Community Health, 37(5), 1110–1118. doi:10.1007/s10900-012-9552-1