ABSTRACT

Japan Tobacco International (JTI) is the international division of Japan Tobacco Incorporated, and the world’s third largest transnational tobacco company. Founded in 1999, JTI’s rapid growth has been the result of a global business strategy that potentially serves as a model for other Asian tobacco companies. This paper analyses Japan Tobacco Incorporated’s global expansion since the 1980s in response to market opening, foreign competition, and declining share of a contracting domestic market. Key features of its global strategy include the on-going central role and investment by the Japanese government, and an expansion agenda based on mergers and acquisitions. The paper also discusses the challenges this global business strategy poses for global tobacco control and public health. This paper is part of the special issue ‘The Emergence of Asian Tobacco Companies: Implications for Global Health Governance’.

Introduction

In 1999, Tokyo-based Japan Tobacco (JT) created its international tobacco division with the goal of becoming ‘the most successful and respected tobacco company in the world’ (Japan Tobacco International [JTI], Citation2016a). In less than two decades, JTI has followed a global business strategy of determined expansion based on mergers and acquisitions to become the third largest transnational tobacco corporation (TTC). Parent company JT is itself a relatively new corporation, launched by the Japanese government in 1985. Until then, Japan’s tobacco business was overseen by a state-owned monopoly established at the end the nineteenth century. In the 1980s the government converted the monopoly into a publicly traded stock company, but continues to hold a significant investment in the privatised operation.

Despite the emergence of JTI as a key global actor, there is limited research into its evolution from a domestic monopoly into a leading TTC. While most work on tobacco industry globalisation treats TTCs as part of a homogeneous industry in pursuit of global expansion (Lee, Eckhardt, & Holden, Citation2016), this paper analyses the specific factors and strategies that have underpinned JTI’s global expansion, related implications for global tobacco control, particularly the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), and assesses whether these strategies may provide a model for other Asian tobacco companies contemplating similar expansion.

Background

The origins of JTI lie in nineteenth century tax evasion and Japan’s military build-up in the early 1900s. Tobacco in Japan was treated as an agricultural product until 1873, when the first of a series of taxation measures was introduced by the newly created Ministry of Finance (Levin, Citation1997). Widespread tax evasion led the Ministry to recommend the introduction of a monopoly system, which it could more closely control. Opposition by the small number of domestic and overseas producers that had come to dominate the market meant that a semi-monopolistic compromise agreed in 1898 was limited to the sale of tobacco leaf. Full nationalisation in 1904 was aimed at raising revenue for Japan’s war with Russia and, as Levin (Citation1997, Citation2005) notes, as a way to force foreign interests, particularly the American Tobacco Company, from the domestic market.

Monopoly operations changed little until the post-Second World War reconstruction of the Japanese economy, a process that included the creation of the Japan Tobacco and Salt Public Corporation in 1949. The new organisation was given responsibility for all domestic tobacco production as well as the tobacco leaf sector, wholesale and retail distribution (Levin, Citation2005), and domestic tobacco production and consumption rose steadily over the next 35 years. In 1982, the monopoly accounted for 98.5% of all cigarette sales in Japan (see ), a degree of dominance created by a 90% tariff rate on imported cigarettes; state-control of licensed tobacco retail shops, which allowed only a limited number to sell foreign tobacco products; and particularly restrictive rules on advertising and promotion of imported brands (Honjo & Kawachi, Citation2000; Lambert, Sargent, Glantz, & Ling, Citation2004).

Figure 1. Cigarette sales Japan. Domestic vs. imported brands, 1982–2014. Source: Compiled from Japan Health Promotion & Fitness Foundation. (2015). Import Tobacco Share [data from Tobacco Institute of Japan: Tobacco Statistics] http://www.health-net.or.jp/tobacco/product/pd080000.html; Euromonitor (Citation2015a). Cigarettes in Japan. London: Euromonitor International.

![Figure 1. Cigarette sales Japan. Domestic vs. imported brands, 1982–2014. Source: Compiled from Japan Health Promotion & Fitness Foundation. (2015). Import Tobacco Share [data from Tobacco Institute of Japan: Tobacco Statistics] http://www.health-net.or.jp/tobacco/product/pd080000.html; Euromonitor (Citation2015a). Cigarettes in Japan. London: Euromonitor International.](/cms/asset/f1bef389-f407-44b9-9620-b4049d90cacc/rgph_a_1273368_f0001_b.gif)

By the 1980s, Japanese political opinion had shifted toward privatisation of state enterprises (Higashi & Lauter, Citation1987) as part of wide-ranging initiatives aimed at reforming the national administration system, and addressing labour relations in the telephone, long-distance rail, and tobacco monopolies (Levin, Citation2005). Subsequent reform of the tobacco sector was formalised by the 1984 Tobacco Business Act, designed to achieve industry growth, secure government revenue, and contribute to the ‘healthy’ expansion of the national economy. The Act also stipulated that the newly privatised company had to purchase the entire usable domestic tobacco leaf crop, which would have long term implications. The Japan Tobacco Incorporated Act of 1 April 1985 established a publicly traded stock company that was 100% government owned until 1994. Government control has since declined to a one-third holding in 2016 (JT, Citation2009; Levin, Citation2005; Levin, Citation2013).

The new corporation continued to operate as an effective monopoly, protected by high import tariffs, and a labyrinthine domestic distribution system, which combined to limit imports to approximately 2% of all cigarettes smoked in the country (Chaloupka & Laixuthai, Citation1996). This situation was short-lived. In 1985, the United States Trade Office (USTR) commenced an investigation into Japanese restrictions on imported cigarettes, beginning a process that would lead to a fundamental alteration of the domestic market (Chaloupka & Laixuthai, Citation1996) and cause JT to look to overseas markets for growth and revenue.

Methods

Google Scholar, PubMed, and JSTOR were initially searched for scholarly literature on the Japanese tobacco industry, focusing on public health, business, and regional studies, as well as political science and international relations. These searches returned information and data on various aspects of the Japanese tobacco market, although there were limited studies on the global business strategies of JT. We also reviewed available the company’s annual reports (2006–2015), as well as financial updates and fact sheets, and consulted industry publications including Tobacco Journal International, Tobacco Reporter, and Tobacco Asia, general business news sources including the Financial Times and Bloomberg News, and economic data from Euromonitor International, MarketLine, and the UN trade database to triangulate material retrieved. The scope and evolution of the project did not allow for interviews with Japanese policy-makers or others stakeholders, and limited it to English-language resources. The paper adopts the analytical framework developed by Lee and Eckhardt (Citation2016) to structure and analyse the key drivers behind JTI’s global business strategy, and the extent to which the company has succeeded in pursuing its global ambitious.

Findings

What are the key factors behind JTI’s global business strategy?

JT expansion strategies have been largely in response to aggressive competition from TTCs in a declining domestic market (Japan News, Citation2015). In the 1980s, Philip Morris International (PMI), RJ Reynolds (RJR) and Brown & Williamson (B&W) formed the U.S. Cigarette Export Association to lobby the U.S. government to demand access to the restricted domestic cigarette markets of Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand. The resulting actions taken by the USTR, and their outcomes, have been comprehensively analysed (Chaloupka & Laixuthai, Citation1996; MacKenzie & Collin, Citation2012; Taylor, Chaloupka, Guidon, & Corbett, Citation2000). The threat of U.S. trade sanctions by the USTR convinced all four countries to drop barriers to imported cigarettes.

In 1982, the Japanese government lowered the import tariff from 90% to 20%, and allowed TTCs to advertise on television, billboards, and in magazines. The number of licensed shops permitted to sell foreign cigarettes rose from 15,000 to 260,000, and TTCs were allowed to establish their own sales networks, and to set prices with governmental approval. In 1987, an ad valorem tax that had kept imported cigarettes more expensive after the tariff reduction was also withdrawn by the Japanese government following further pressure from U.S. officials, significantly reducing the price gap between domestic and imported brands (Honjo & Kawachi, Citation2000). Around the same time, the U.S., France, Japan, United Kingdom, and West Germany signed the Plaza Accord (1985), an agreement aimed at depreciating the U.S. dollar in relation to the German Mark and Japanese Yen. The resulting appreciation of the Yen saw an immediate drop in the price of foreign cigarettes.

JT’s market share dropped from 98.5% to 84.1% between 1982 and 1990, and has continued to decline, to 59.9% in 2015 (see ) due, according to the company, to ‘intensifying competition’ (JT, Citation2016a, p. 31). Yet, with almost 60% of domestic cigarette sales, and the producer of nine of the country’s 10 bestselling brands, JT has remained the key player in the domestic tobacco market (Euromonitor, Citation2015a).

TTC competition resulted in increased smoking rates, particularly among Japanese women (Honjo & Kawachi, Citation2000; Sato, Araki, & Yokoyama, Citation2000). Longer term however, there has been a clear decline in smoking in Japan (see ), suggesting a further motivation for JT to look to overseas growth opportunities. Male smoking rates have steadily dropped from 82.3% in 1965 to 30.3% by 2014; rates among women have declined from 15.7% in 1965 to 9.8% (), and the overall smoking rate is now below 20% for the first time (Hongo, Citation2014). Per capita consumption has also declined markedly since the 1975 peak of 3497 cigarettes in the late 1970s to 1618 in 2015 (Levin, Citation2016).

Figure 2. Japan, smoking prevalence by gender. 1965 to 2014 (20 yrs+). Source: Japan Health Promotion & Fitness Foundation. Adult Smoking Rate [JT’s Japan Smoking Rate Survey] http://www.health-net.or.jp/tobacco/product/pd090000.html.

![Figure 2. Japan, smoking prevalence by gender. 1965 to 2014 (20 yrs+). Source: Japan Health Promotion & Fitness Foundation. Adult Smoking Rate [JT’s Japan Smoking Rate Survey] http://www.health-net.or.jp/tobacco/product/pd090000.html.](/cms/asset/9eff01e4-8bd3-40eb-ab4f-3a67bf1afb76/rgph_a_1273368_f0002_b.gif)

This decline has occurred despite Japan’s limited commitment to tobacco control. Levin (Citation2013, p. 474) argues that the Tobacco Business Act ‘reflects a political economy where tobacco interests have extraordinary control via sympathetic legislators and, more importantly, potent agency protection given by taxation and budgetary bureaucrats in Japan’s Ministry of Finance’. In this environment, the only significant policy developments have been the 2002 Health Promotion Act and Japan’s ratification of the FCTC, which have legitimised the profile of tobacco control and created increased discussion among the public, policy-makers, and in the media. These have been augmented by gradual, and contested, tax increases, a small number of administrative measures, and local level smoke-free decrees (Levin, Citation2013).

In the absence of comprehensive regulation, the drop in smoking rates appears attributable to a combination of the international obligations inherent in Japan’s ratification of the FCTC; the later onset of the tobacco epidemic and related morbidity and mortality, compared to the U.S.A.; the pharmaceutical industry’s promotion of smoking cessation products which signals the entry of another key economic actor into the smoking and health dialogue, and, seemingly, to changes in cultural attitudes to smoking (Levin, Citation2013).

A further motivation for JT’s global expansion has been to secure tobacco leaf at lower price, and of better quality. The Tobacco Business Act 1984 requires the corporation to purchase the entire usable domestic tobacco leaf crop, negotiate contracts with domestic leaf growers, and determine the total area used for tobacco cultivation and tobacco leaf prices (JT, Citation2009). This provision ensures that the country’s tobacco farming lobby plays a key role in the politics of the company, including the government’s continued shareholding. JT has been increasingly concerned about the quality and reliability of the domestic crop, leading to become a global ‘natural resource seeker’ (Lee & Eckhardt, Citation2016).

These concerns were exacerbated by the 2011 tsunami and nuclear disaster in Fukushima prefecture, one of the country’s most significant agricultural areas (Johnson, Citation2011) and an important supplier of tobacco leaf (Smith, Citation2011). In 2011, the cost of domestic leaf was roughly 2.8 times higher than imported, contributing to JT’s growing dependence on imported crops. The tsunami also led to the government’s decision to sell approximately one-third of its shares in 2013 to fund recovery and reconstruction; it currently retains 33% of JT shares, the minimum holding required by law (Euromonitor, Citation2015a). Discussions aimed at full privatisation continue, but political considerations would pose obstacles in the medium term (Nikkei Asian Review, Citation2015).

Which global business strategies has JTI pursued?

Diversification, restructuring, and acquisition

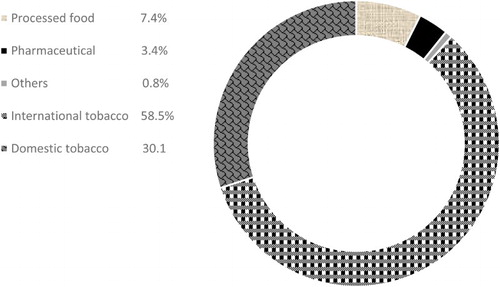

JT’s initial response to competition from TTCs was to diversify into the pharmaceutical, food, and beverage sectors and to expand its tobacco operations (JT, Citation2016a). Despite diversification, tobacco still accounts for 88.6% of revenue (see ), and the decision to leave the beverage sector at the end of 2015 is likely to mean increased concentration on the tobacco business (Euromonitor, Citation2015a).

Figure 3. Japan Tobacco: revenue by segment and percentage, 2015. Source: Japan Tobacco Inc. (2016). Annual Report FY2015.

Domestic tobacco operations have undergone significant restructuring in recent years that includes factory closures in 2009, 2011, and 2012 (Euromonitor, Citation2015a). In October 2013, closure of a further four factories, a leaf processing facility, and cigarette vending machine manufacturer due to the ‘increasingly competitive environment’ was announced, leading to the loss of 1600 jobs through voluntary retirement by 2016 (JT, Citation2013). Despite these cuts, the number of employees in the domestic tobacco business has remained relatively stable, dropping only slightly from 11,940 in 2006 to 11,648 in 2014 (JT, Citation2010a, Citation2014b, Citation2016a).

Predominance of the international tobacco division within the corporation is largely the result of two key acquisitions of competitor operations. In 1999, the non-U.S. operations of RJR Nabisco were purchased for US$8 billion. While deemed an excessive price by some analysts at the time (Strom, Citation1999), it was also acknowledged that few other options to acquire a leading competitor existed, particularly as PMI and British American Tobacco (BAT) were rumoured to also be interested in RJR’s non-U.S. business. JTI was created to oversee international operations, and immediately became the third largest TTC based on its rights to newly acquired leading international brands such as Camel, Winston, and Salem, and access to markets in Europe and Canada (Strom, Citation1999).

If acquisition of RJR Nabisco announced the arrival of JTI as a key global actor, the US$15 billion takeover of the Gallaher Group in 2007, then the fifth largest TTC, consolidated its leading position within the industry. The deal was the largest overseas acquisition by any Japanese company to that point, and effectively doubled JTI’s operations through new market share in the UK and Europe (New York Times, Citation2007). It also significantly expanded its global flagship brand portfolio which accounts for 60% of sales (JTI, Citation2016b). Gallaher brands Benson & Hedges, Silk Cut, Sobanie, LD, and Glamour were added to Mild Seven (renamed Mevius in 2012), which originated in Japan, and Winston and Camel, acquired in the RJR deal.

The 2016 US$5 billion acquisition of international rights of the Reynolds American subsidiary, Santa Fe Natural Tobacco which produces Natural American Spirit cigarettes (Craver, Citation2016), is JTI’s largest and most recent acquisition since the Gallaher takeover (). Planned as an addition to its Global Flagship Brand portfolio (JT, Citation2016a), the company describes Natural American Spirit as ‘the only truly global “additive free”, premium cigarette with a marketing theme that is environmentally conscious and socially progressive’ (JTI, Citation2015b). Natural American Spirit is currently sold in 13 countries, and popular in Western Europe, but Japan is the biggest market for the brand outside of the U.S. (Japan Times, Citation2015), suggesting the takeover had both domestic and foreign consumers in mind.

Table 1. Japan Tobacco acquisitions, 1992–2015 (JTI from 1999).

Geographic distribution

JTI brands are produced in 25 factories and sold in 120 countries. As a result of the RJR and Gallaher takeovers, markets in Western Europe and those of former Soviet Union countries, particularly Russia, are JTI’s most important operations. In Western and Eastern Europe, JTI holds a 20.8% and 27.5% regional share respectively (see ).

However, JTI has been overtaken in Eastern Europe by PMI, and is no longer market leader in any region. Over-reliance on European markets has made the company vulnerable to localised volatility in smoking and sales. Market contraction in Russia, Ukraine, and Kazakstan in 2013/2014, for example, resulted in a 10.5% drop in regional shipments (Euromonitor, Citation2016b; JT, Citation2015a), and a significant impact on overall volume sales (see ).

Figure 4. Global Cigarette Volume Sales Versus Japan Tobacco Sales, 2011–2014. Source: JTI annual report 2015.

Taiwan is JTI’s main Asian market with a 37% market share, based largely on sale of Mevius (Euromonitor, Citation2015b). In 2015, the company received permission from the Taiwanese government to construct a new production facility under the terms of a 2011 Taiwan-Japan Bilateral Investment Agreement (Taiwan-Japan, Citation2011). The decision has provoked protest among public health advocates, which may delay construction (Eckhardt, Fang, & Lee, Citation2017), but when completed the new factory will be JTI’s largest offshore site and manufacture cigarettes for both Taiwanese smokers, thereby saving on import taxes, and for export to Southeast Asia (Gerber, Citation2015). Other key Asian operations include the relatively small Singapore market, as well as Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan in Central Asia ( and ).

Table 2. Retail market share (%); selected regions and leading cigarette manufacturers.

Table 3. JTI export volumes by regiona in billion sticks.

China, the world’s largest cigarette market, remains all but closed to foreign manufacturers, and the China National Tobacco Corporation’s (CNTC) 98.3% share of sales leaves little room for competitors. JTI is third among TTCs in China at 0.1% of sales, behind BAT (0.6%) and PMI (0.5%) (Euromonitor, Citation2016a). In 2003, JT established a China Division to oversee operations in China, Hong Kong, and Macau within its domestic tobacco operations, transferring these markets from JTI (He, Takeuchi, & Yano, Citation2010). Reported sales volumes from the China Division are combined with Domestic Duty-Free in company annual reports, making assessment of operations in China difficult. Between 2008 and 2014, the two divisions sold approximately 3.5 billion cigarettes annually, accounting for an average of 3.5% of sales by JT’s domestic operation (JT, Citation2014b).

JTI has a 14% share of the Middle East and African markets despite significant gains made by PMI and, particularly, Imperial Tobacco over the past decade. Negligible presence in Latin America (2.1% of sales) is based on operations in Bolivia, Argentina, and Mexico, and it has a presence in North America, capturing just 1.3% of sales.

Recent acquisitions in the Middle East and Africa, aimed at expanding sales beyond its key European markets, have included purchase of the Tehran-based Arian Tobacco Industry by Iranian subsidiary JTI Pars in 2015 resulted in 40% market share, and moved JTI ahead of BAT as market leader (Bozorgmehr, Citation2015). Expansion in Africa, where large increases in smoking rates will occur in coming decades have been particularly important. In 2011, a JTI executive vice-president underlined the importance of ‘gaining a foothold’ in this ‘very energetic and growing market’ (Ozasa & Onomitsu, Citation2011), and company brands are now sold in more than 20 African countries. In 2011, the company increased its share in the Tanzania Cigarette Company from 51% to 75%, and now controls a 97% market share in the country (Ozasa & Onomitsu, Citation2011).

It also acquired the Haggar Cigarette & Tobacco Factory which holds an 80% market share in the Republic of Sudan, along with operations in South Sudan that same year (JTI, Citation2011). In 2015, JTI announced the purchase of a 40% share of National Tobacco Enterprise Ethiopia, providing the company with the ‘opportunity to leverage our successful experience in other Middle East and African markets’ (JTI, Citation2015a). African leaf producers have also been targeted for takeovers and investment to improve security of supply. JTI took over Africa Leaf (Malawi) in 1999 (JTI Malawi, Citation2016) and, since 2010, JTI Leaf Zambia has been supported by the Zambia-Japan Trade and Investment Promotion program which contracts farmers to grow tobacco in collaboration schemes (Chanda, Citation2014). In 2009, JTI bought the leaf tobacco business of the UK-based dealer Tribac Leaf which includes operations in Malawi, Zambia, China, and India.

Efforts to raise its relatively low Latin America profile have included acquisition of two Brazilian companies, Kannenberg & Cia and Kannenberg, Barker, Hail & Cotton Tabacos (KBH&C), and agreeing a joint venture with the U.S. producers Hail & Cotton, and JEB International (Tobacco International, Citation2009). In 2016, JTI’s purchased the Brazilian cigarette distributer Fluxo Brasil Distribuidora do Produtos for an undisclosed amount (Nikkei Asian Review, Citation2016a), and a 50% stake in the Dominican cigarette manufacturer La Tabacarela (Nikkei Asian Review, Citation2016b).

Product diversity and development

Although JTI relies on eight global flagship brands for 60% of cigarette sales (JTI, Citation2016a), it produces more than 100 tobacco products. It continues to extend its product range, concentrating on three key portfolio categories: manufactured cigarettes; fine, or loose cut tobacco; and what are described as ‘emerging products’ (JT, Citation2015a). In May 2012, it purchased Gryson, a Belgium-based manufacturer of roll-your-own and loose tobacco products that holds a 21% share of the market in France (Yamaguchi & Boyle, Citation2012). Reflecting changes in global tobacco use, JTI has also added non-cigarette tobacco products to its holdings, investing in e-vapour and tobacco-vapour products. In 2014, the company bought UK-based Zandera, producer of E-Lites electronic cigarette (Schroter, Citation2014), and introduced E-Lites Curv in the UK, Ireland, and Germany (JT, Citation2016a). Logic Technology Development of Florida, which accounts for approximately 20% of e-cigarette sales in U.S. convenience store, was acquired in 2015, making JTI the third largest e-cigarette company in the U.S. (JT, Citation2016a). The company also acquired U.S.-based Ploom’s heat-not-burn vaporiser system, which is being adapted for initial release in the Japanese market, with longer term plans to expand into other markets (JT, Citation2016a).

In 2013, the company also moved into the shisha (hookah) tobacco market by acquiring the Al Nakhla Tobacco Company and Al Nakhla Tobacco Company of Egypt, described in one market analysis as a deal ‘with exquisite rationale’ (MacGuill, Citation2012) for JTI. Both takeovers and investments have been central to JTI’s strategies in Africa. Among the world’s largest shisha producers, Nakhla’s products are sold in 80 countries, primarily in the Middle East and North Africa. JTI smokeless tobacco products also include the Zerostyle Mint, described as a new-style snuff tobacco product that has been aimed, so far, at the domestic market (JT, Citation2010b). JTI’s snus brands, including versions of Camel, and LD tobacco, are aimed primarily at Scandinavian consumers (JT, Citation2016a).

Management and expertise

Like market leader PMI, JTI is headquartered in Switzerland. The Geneva office oversees operations in 120 companies and some 26,000 employees representing, according to company information, more than 100 nationalities. In a break from Japanese corporate tradition, in which the national hierarchical management style is imposed on foreign operations (Yuk, Citation2010), only two of its 17-member Executive Committee are Japanese nationals. The company reportedly relies heavily on international management and expertise (JTI, Citation2016c).

Marketing, advertising and corporate social responsibility initiatives

Detailed figures on JTI marketing spending are not readily available. It is known, however, that tobacco companies spent approximately US$9 billion on marketing activities in the U.S. alone in 2013, which provides some indication of the scale of marketing undertaken by leading TTCs (United States. Federal Trade Commission, Citation2016).

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is an important element of current industry promotional strategy, and if counterintuitive in the case of cigarette manufacturers, related initiatives can be an effective means of counteracting criticism, and influencing the tobacco control agenda by pre-empting legislation (Fooks and Gilmore (Citation2013). JTI (and parent company JT) has employed extensive CSR and philanthropy initiatives aimed at burnishing its image by highlighting financial support for social projects and a commitment to sustainability (JT, Citation2015b). Recent JTI projects include on-going financial support for communities recovering from the 2011 earthquake, and more than 250 projects connected to well over 120 partnerships in the fields of social welfare, arts and culture, environmental protection, and disaster relief.

Many of these CSR activities are initiated by the JTI Foundation, which reportedly works with 21 partner organisations in nineteen countries (JT, Citation2015b). Presumably in response to criticisms of tobacco industry operations in Sub-Saharan Africa, including use of child labour (Otañez, Muggli, Hurt, & Glantz, Citation2006), JT established the Achieving Reduction of Child Labour in Supporting Education (ARISE), in partnership with the U.S. NGO Winrock International, and the International Labour Organization with the aim of eliminating child labour where it did business (JT, Citation2016b).

How globalised is JTI to date?

Applying the key indicators set out by Lee and Eckhardt (Citation2016) suggests that JTI’s global business strategy has been successful, and response to current downturns in key markets and development of new smoking technologies suggests a continued pursuit of take-over opportunities across the supply chain as a key part of its globalisation strategies. As recently as 2007, JT’s domestic operations accounted for almost three-quarters (71.7%) of group net sales (JT, Citation2008), but this has now been surpassed by international operations in terms of revenue share (Euromonitor, Citation2015a) (see ). The company’s global profile is underlined by inclusion in Fortune’s Global 500 list of the world’s largest companies by revenue, and its ranking among the world’s 75 most transnationalised companies by the United Conference on Trade and Development’s (UNCTAD) transnationality index. Furthermore, JTI is ranked 90th on UNCTAD’s list of global companies with the largest amount of foreign assets (Hawkins, Holden, Eckhardt, & Lee, Citation2016).

Discussion

JTI’s emergence as the third largest TTC has been based on an aggressive strategy of major foreign acquisitions, licensing agreements, and joint ventures with a range of tobacco product manufacturers, leaf growers, and distributors. This has been accompanied by the development and diversification into new smoking technologies.

As with the tobacco industry more generally, the company faces major challenges in upcoming decades however. Declining smoking rates in many of its key markets, most notably Russia and the UK, and the potential impact of greater adoption to tobacco control measures in Eastern Europe are compounded by the decreasing proportion of smokers in Japan (Hedley, Citation2016). JTI’s likely continued pursuit of mergers and acquisitions has led to speculation that it may bid for UK-based Imperial Tobacco, currently the fourth-largest TTC (Euromonitor, Citation2016b) The latter’s product range, which includes Davidoff, Winston and Kool cigarettes, Drum loose tobacco, blu e-cigarettes, and Rizla rolling papers, would significantly enhance JTI’s existing product portfolio. A merged JTI/Imperial would create an industry leader across the Middle East and Africa; joint market leader with PMI in Eastern and Western Europe; and hold a 25% share across Australasian markets (Euromonitor, Citation2016a). There would, however, be only modest gains in the Americas and Asia.

JTI would face significant obstacles if it were to attempt a takeover. Imperial’s stock price has risen as speculation that BAT (Chambers, Citation2015), and possibly the CNTC (Elder, Citation2015), are also interested. There are also concerns that a takeover by JTI or BAT would breach anti-trust regulations in many countries. In the UK, for instance, JTI and Imperial currently hold a combined 71% market share (Euromonitor, Citation2016a), leading analysts to suggest that any takeover is likely to involve a carve-up in which JTI and BAT acquire different parts of Imperial’s operations (Geller & Berry, Citation2015).

Implications for public health

As a leading company in an industry that causes an estimated 6 million annual deaths (World Health Organization, Citation2015), JTI’s successful globalisation strategy has clear implications for public health. The 1999 takeover of RJR and formation of JTI, was a key event in the globalisation of the tobacco industry during the late twentieth century, a period characterised by consolidation that has left four TTCs with a 40% share of global cigarette salesFootnote1 and aggressive expansion into low and middle-income countries that has been facilitated by trade liberalisation (Taylor et al., Citation2000).

TTC strategies to block, impede, and circumvent meaningful tobacco control regulation are well-established, and claims of compliance and responsible corporate conduct are rightly met with scepticism (Lee, Ling, & Glantz, Citation2012; Proctor, Citation2001). Recent industry response to plain packaging is a case in point. JTI, with the other three leading TTCs, has mounted unsuccessful legal challenges in Australia (Martin, Citation2016) the United Kingdom (Croft, Citation2016), and France (Tobacco Journal International, Citation2016), and has announced plans to appeal the decisions in the two European countries. JTI’s public position, that ‘[e]xtreme measures, such as plain packaging of tobacco products … will not eliminate smoking by minors, or cause minors to stop smoking’ reflects the company’s broader stance on tobacco control, which is to reserve ‘right to question, and if necessary challenge, regulation that is flawed, unreasonable, disproportionate, or without an evidentiary foundation, in order to protect its legitimate business interests’ (JTI, Citation2012).

Publications establishing tobacco industry complicity in global cigarette smuggling are summarised in a 2016 analysis by Joossens, Gilmore, Stoklosa, and Ross (Citation2016). JTI’s involvement in illicit trade has been described by Wen et al. (Citation2006) in their analysis of Taiwan’s 1986 decision to drop restrictions on imported cigarettes that allowed leading U.S.-based producers and BAT to enter the domestic market, but excluded JTI. Faced with uncompetitive excise rates, JTI resorted to ‘massive smuggling’ of its brands into Taiwan via a Swiss subsidiary that created legal cover (Wen et al., Citation2006). In 2007, JTI settled a dispute with the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) to avoid smuggling-related litigation that involved cooperation in tackling the contraband cigarette trade, payment of a €400 million fine, and agreement to make payments equal to 100% of evaded taxes related to future seizure of illicit volumes of their brands (PMI, BAT, and Imperial have reached similar agreements) (Joossens et al., Citation2016). Subsequent analysis, however, indicates that JTI and competitor TTCs have continued their involvement in illicit trade, and that JTI has been ‘less than less than compliant with the EU agreement’ (Joossens et al., Citation2016).

Industry opposition extends to global governance and challenges to the FCTC (WHO, Citation2003), which are well-documented. Strategies have included lobbying national FCTC delegations and governments; arguing that the treaty would have negative economic impacts; raising doubts about the WHO’s mandate to develop a legally binding international agreement; and to propose less rigorous alternative agreements (Balwicki, Stokłosa, Balwicka-Szczyrba, & Tomczak, Citation2015; Mamudu, Hammond, & Glantz, Citation2008; Weishaar et al., Citation2012). Japan’s ratification of the treaty in 2004, (United Nations, Citation2016) given that the country is ‘an especially important player in the global governance regime under the FCTC in light of profound conflicts arising from its Minister of Finance’s on-going position as the controlling shareholder of Japan Tobacco Inc’ (Levin, Citation2016).

Assunta and Chapman (Citation2006) found that Japanese government negotiators, looking to protect JT’s domestic and international business, successfully exploited the treaty’s consensus formula to have proposals for optional measures included, and the final text of the treaty accommodates flexibility on interpretation and implementation of key tobacco control issues. Since ratification, Japan has continued to take an ambiguous position on the treaty. For instance, Japan sent senior members of the Ministry of Finance’s tobacco and tax divisions as part of its delegation to the November 2012 Fifth Conference of the Parties in direct contravention of FCTC Article 5.3 (Levin, Citation2013), which requires Parties to protect their tobacco control policy-making from tobacco industry interference (WHO, Citation2003). Inclusion of Ulle Geir, JTI’s director of international trade among the speakers at UNCTAD’s World Investment Forum in Kenya in 2016 provides a more recent illustration of the company’s seeming strategies to influence the global health discourse (UNCTAD, Citation2016). Geir was removed from the list of speakers following complaints by global tobacco control advocates, who argued that tobacco was a barrier to development and cited the UN General Assembly’s recognition of the fundamental conflict of interest between the tobacco industry and public health in 2011 (Framework Convention Alliance, Citation2016).

In 2014, JTI offered its own, idiosyncratic, interpretation of Article 5.3. In his criticism of closed door meetings at the Sixth Conference of the Parties, the company’s vice-president for global regulatory strategy described the situation as an abuse of 5.3 ‘which is now commonly used as an excuse to shut out the tobacco sector and anyone who is perceived to be linked to us’ leaving the meetings to be ‘again hijacked by the tobacco control lobbyists who freely exercise undue influence’ (JTI, Citation2014). The government’s attitude toward the treaty is neatly summarised in its 2014 FCTC implementation report which confirms that it does protect public health related to tobacco control from the interests of the tobacco industry (WHO, Citation2014).

Speculation around the government’s future role in the company has continued since it reduced its holding to 33% under the terms of the Reconstruction Act, 2011. The Act also directs the government to assess, by 2023, the potential of withdrawing completely from JTI, a scenario mentioned by the company’s 2015 annual report (JTI, Citation2015b). Government disposal of its remaining shares would, according to one market analysis, would be likely to lead to a ‘profound liberalisation and restructuring of the company’ that would include selling off non-tobacco divisions and further international acquisitions (Euromonitor, Citation2016b). Yet, such restructuring may not be in the company’s best interest as the current situation allows JTI to rest ‘easily at home in its Tokyo sanctuary’ (Levin, Citation2013) where it benefits from government support for global expansion.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Jappe Eckhardt http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8823-0905

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. PMI (14.7), BATA (10.8%), JTI (10.8%) and Imperial (5.0%) accounted for 39.3% of global cigarette sales in 2015. Sales within China by the CNTC accounted for 44% of total (Euromonitor, Citation2016a).

References

- Assunta, M., & Chapman, S. (2006). Health treaty dilution: A case study of Japan’s influence on the language of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60(9), 751–756. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.043794

- Balwicki, Ł, Stokłosa, M., Balwicka-Szczyrba, M., & Tomczak, W. (2015). Tobacco industry interference with tobacco control policies in Poland: Legal aspects and industry practices. Tobacco Control. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052582

- Bozorgmehr, N. (2015, October 18). Japan Tobacco buys Iranian cigarette maker to boost dominance. Financial Times. Retrieved from http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/626e5c5a-7576-11e5-a95a-27d368e1ddf7.html.

- Chaloupka, F., & Laixuthai, A. (1996). U.S. trade policy and cigarette smoking in Asia. NBER, p. 5543.

- Chambers, S. (2015, November 20). Imperial Tobacco gains on speculation BAT preparing a bid. Bloomberg Business. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-11-20/imperial-tobacco-gains-on-speculation-bat-raising-money-for-bid

- Chanda, D. (2014). Strategies to entice investors bearing fruit. Retrieved from http://www.times.co.zm/?p=7801

- Craver, R. (2016, January 14). Reynolds completes $5B sale of international rights to super-premium brand. Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved from http://tinyurl.com/z4u5cdj

- Croft, J. (2016, May 19). High court rejects big tobacco’s appeal against plain packaging. Retrieved from http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/6b0164e0-1dbc-11e6-b286-cddde55ca122.html

- Eckhardt, J., Fang, J., & Lee, K. (2017). The Taiwan tobacco and liquor corporation: To ‘join the ranks of global companies’. Global Public Health. doi:10.1080/17441692.2016.1273366

- Elder, B. (2015, September 24). Imperial Tobacco climbs on break-up talk. FT.com. Retrieved from http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/94f540d0-62de-11e5-a28b 50226830d644.html#axzz3zY0YxxpW

- Euromonitor International. (2015a). Japan Tobacco Inc. in Tobacco (Japan). London: Euromonitor.

- Euromonitor International. (2015b). JT Tobacco international Taiwan Corp in Tobacco (Taiwan). London: Euromonitor.

- Euromonitor International. (2016a). Global cigarette sales, company shares. London: Euromonitor.

- Euromonitor International. (2016b). Japan Tobacco Inc. in Tobacco (World). London: Euromonitor.

- Fooks, G. J., & Gilmore, A. B. (2013). Corporate philanthropy, political influence, and health policy. PLoS One, 8(11), e80864. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080864

- Framework Convention Alliance. (2016, July 20). Letter to Dr Mukhisa Kituyi, United Nations conference on trade and development. Retrieved from http://www.fctc.org/images/stories/UNCTAD_Art53_Final.pdf

- Geller, M., & Berry, F. (2015, November 26). Any Imperial Tobacco takeover would face major hurdles. Reuters. Retrieved from www.reuters.com/article/us-imperial-tobacco-m-a-idUSKBN0TF1XW20151126.

- Gerber, J. (2015, August 22). Group calls for a stop to Japan Tobacco investment. Taipei Times. Retrieved from http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2015/08/22/2003625930

- Hawkins, B., Holden, C., Eckhardt, J., & Lee, K. (2016). Reassessing policy paradigms: A comparison of the global tobacco and alcohol industries. Global Public Health. doi:10.1080/17441692.2016.1161815

- He, P., Takeuchi, T., & Yano, E. (2010). Analysis of a tobacco vector and its actions in china: The activities of Japan Tobacco. Tobacco Induced Diseases, 8, 13. doi:10.1186/1617-9625-8-13

- Hedley, D. (2016). The big four – performances compared. London: Euromonitor.

- Higashi, C., & Lauter, P. G. (1987). The Internationalization of the Japanese Economy. Boston: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Hongo, J. (2014, July 31). Smoking rate drops below 20% in Japan. Japan Realtime. Retrieved from http://blogs.wsj.com/japanrealtime/2014/07/31/smoking-rate-drops-below-20-in-japan/

- Honjo, K., & Kawachi, I. (2000). Effects of market liberalisation on smoking in Japan. Tobacco Control, 9(2), 193–200. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.2.193

- Japan Health Promotion & Fitness Foundation. Adult smoking rate [JT’s Japan Smoking Rate Survey]. Retrieved from http://www.health-net.or.jp/tobacco/product/pd090000.html

- Japan News. (2015, December 28). 30 years of JT; resolute long-term plan stems from monopoly. The Japan News, p. 6.

- Japan Times. (2015, September 30). JT to buy natural American spirit outside U.S. for $5 billion. Japan Times. Retrieved from: http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2015/09/30/business/corporate-business/jt-buy-natural-american-spirit-outside-u-s-5-billion/#

- Japan Tobacco. (2008). Annual Report FY2007. Retrieved from http://www.jt.com/investors/results/annual_report/pdf/annual2007_E_all.pdf

- Japan Tobacco. (2009). Annual Report FY2008. Retrieved from http://www.jt.com/investors/results/annual_report/index.html

- Japan Tobacco. (2010a). Annual Report FY2009. Retrieved from http://www.jt.com/investors/results/annual_report/pdf/annual2009_E_all.pdf

- Japan Tobacco. (2010b). JT to launch new style of smokeless tobacco product ‘Zerostyle Mint’. Retrieved from http://www.jt.com/investors/media/press_releases/2010/0317_01/

- Japan Tobacco. (2013). Media release. Japanese domestic tobacco business to further strengthen its competitiveness. Retrieved from https://www.jt.com/media/press_releases/2013/pdf/20131030_04.pdf

- Japan Tobacco. (2014b). Fact sheets. FY2014. Retrieved from http://www.jt.com/investors/results/fact_sheet/pdf/20150320_8.pdf

- Japan Tobacco. (2015a). Annual Report FY2014. Retrieved from http://www.jt.com/investors/results/annual_report/pdf/annual.fy2014_E_all.pdf

- Japan Tobacco. (2015b). JT Group Sustainability Report FY2014. Retrieved from http://www.jti.com/files/2814/3436/2259/JT_Group_Sustainability_Report_FY2014_.pdf

- Japan Tobacco. (2016a). Annual Report FY2015. Retrieved from https://www.jt.com/investors/results/annual_report/pdf/annual.fy2015_E_all.pdf

- Japan Tobacco. (2016b). Corporate social responsibility. ARISE. Retrieved from https://www.jt.com/csr/supply_chain/agricultural_labor_practices/modalwindow3.html

- Japan Tobacco International. (2011). Media release. JT completes its acquisition of a leading tobacco company in the Republics of Sudan and South Sudan. Retrieved from https://www.jt.com/investors/media/press_releases/2011/pdf/20111201_02.pdf

- Japan Tobacco International. (2012). Product regulation. Retrieved from http://www.jti.com/how-we-do-business/product-regulation/

- Japan Tobacco International. (2014, October 13). Press Release. WHO throws out public at Moscow meeting: ‘What do they have to hide?’ asks JTI. Retrieved from http://www.jti.com/files/8314/1321/4894/JTI_Press_Release_COP6_Exclusion_13-10-2014.pdf

- Japan Tobacco International. (2015a). JT acquires 40% of Ethiopia’s NTE: Company continues expansion into Africa. Retrieved from http://www.jti.com/media/news-releases/jt-acquires-40-ethiopias-nte/

- Japan Tobacco International. (2015b, September 29). Media release. JT acquires natural American spirit business outside the United States. Retrieved from http://www.jti.com/media/news-releases/jt-acquires-natural-american-spirit-business-outside-united-states/

- Japan Tobacco International. (2016a). Global flagship brands. Retrieved from http://www.jti.com/brands/global-flagship-brands/

- Japan Tobacco International. (2016b). Leadership. Retrieved from http://www.jti.com/our-company/leadership/

- Japan Tobacco International. (2016c). Business culture. Retrieved from http://www.jti.com/how-we-do-business/business-culture/

- Japan Tobacco International Malawi. (2016). JTI Malawi. Retrieved from http://www.jti.com/our-company/where-we-operate/africa/malawi/english/overview/

- Johnson, R. (2011). Japan’s 2011 earthquake and tsunami: Food and agriculture implications. United States. Congressional Research Service. Retrieved from https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R41766.pdf

- Joossens, L., Gilmore, A. B., Stoklosa, M., & Ross, H. (2016). Assessment of the European Union’s illicit trade agreements with the four major transnational tobacco companies. Tobacco Control, 25, 254–260. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052218

- Lambert, A., Sargent, J. D., Glantz, S. A., & Ling, P. M. (2004). How Philip Morris unlocked the Japanese cigarette market: Lessons for global tobacco control. Tobacco Control, 13(4), 379–387. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.008441

- Lee, K., & Eckhardt, J. (2016). The globalisation strategies of five Asian tobacco companies: An analytical framework. Global Public Health. doi:10.1080/17441692.2016.1251604

- Lee, K., Eckhardt, J., & Holden, C. (2016). Tobacco industry globalization and global health governance: Towards an interdisciplinary research agenda. Palgrave Communications, 2, 16037.

- Lee, S., Ling, P., & Glantz, S. (2012). The vector of the tobacco epidemic: Tobacco industry practices in low and middle-income countries. Cancer Causes and Control, 23, 117–129. doi:10.1007/s10552-012-9914-0

- Levin, M. (1997). Smoke around the rising sun: An American look at tobacco regulation in Japan. Stanford Law Policy Review, 8, 99–123.

- Levin, M. (2005). Tobacco industrial policy and tobacco control policy in Japan. Asian-Pacific Law & Policy, 6(1), 298–313.

- Levin, M. (2013). Tobacco control lessons from the Higgs Boson: Observing a hidden field behind changing tobacco control norms in Japan. American Journal of Law & Medicine, 39, 471–489. doi: 10.1177/009885881303900212

- Levin, M. (2016). Puffing precedents: The impact of the WHO FCTC on tobacco product liability litigation in Japan. Asian Journal of WTO & International Health Law and Policy, 11(1), 19–48.

- MacGuill, S. (2012). Japan Tobacco extends scope with acquisition of world’s largest shisha manufacturer. London: Euromonitor.

- MacKenzie, R., & Collin, J. (2012). ‘Trade policy, not morals or health policy’: The US Trade Representative, tobacco companies and market liberalization in Thailand. Global Social Policy, 12, 149–172. doi:10.1177/1468018112443686

- Mamudu, H. M., Hammond, R., & Glantz, S. A. (2008). Project Cerberus: Tobacco industry strategy to create an alternative to the framework convention on tobacco control. American Journal of Public Health, 98(9), 1630–1642. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.129478

- Martin, P. (2016, May 17). Australia versus Philip Morris. How we took on big tobacco and won. Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved from http://tinyurl.com/jrk54wo

- New York Times. (2007, April 18). Japan Tobacco acquires Britain’s Gallaher Group for $15 billion. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/18/business/worldbusiness/18iht-tobacco.1.5332040.html

- Nikkei Asian Review. (2015, June 18). Government to retain Japan Tobacco shares for time being. Retrieved from http://asia.nikkei.com/Politics-Economy/Policy-Politics/Government-to-retain-Japan-Tobacco-shares-for-time-being

- Nikkei Asian Review. (2016a, February 12). Japan Tobacco buys Brazilian cigarette distributer. Retrieved from http://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Deals/Japan-Tobacco-buys-Brazilian-cigarette-distributor

- Nikkei Asian Review. (2016b, March 2). JT buys half of Dominican producer in Latin American Push. Retrieved from http://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Deals/JT-buys-half-of-Dominican-producer-in-Latin-American-push

- Otañez, M. G., Muggli, M. E., Hurt, R. D., & Glantz, S. A. (2006). Eliminating child labour in Malawi: A British American Tobacco corporate responsibility project to sidestep tobacco labour exploitation. Tobacco Control, 15, 224–230. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014993

- Ozasa, S., & Onomitsu, G. (2011). Japan tobacco to pay $450 million for Sudan cigarette maker. Bloomberg Business. Retrieved from http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2011-07-28/japan-tobacco-agrees-to-pay-450-million-for-sudan-cigarette-maker-haggar

- Proctor, R. (2011). Golden holocaust. Origins of the cigarette catastrophe and the case for abolition. Berkeley, CA: U Calif Press.

- Sato, H., Araki, S., & Yokoyama, K. (2000). Influence of monopoly privatization and market liberalization on smoking prevalence in Japan: Trends of smoking prevalence in Japan 1975–1995. Addiction, 95(7), 1079–1088. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95710799.x

- Schroter, S. (2014). Japan Tobacco to buy E-Cigarette Maker Zandera. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://www.wsj.com/articles/japan-tobacco-to-buy-e-cigarette-maker-zandera-1402489693

- Smith, E. (2011). Japan’s radioactive food found in major local producer. CNN. Retrieved from http://edition.cnn.com/2011/WORLD/asiapcf/03/19/japan.radioactive.food/

- Strom, S. (1999, March 11). Few in Japan see bargain in price of tobacco deal. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1999/03/11/business/international-business-few-in-japan-see-bargain-in-price-of-tobacco-deal.html

- Taiwan-Japan. (2011, September 22). Arrangement between the association of East Asian relations and the interchange association for the mutual cooperation on the liberalization, promotion and protection of investment (Taiwan-Japan Bilateral Investment Arrangement, BIA). Retrieved May 25, 2016, from http://www.moea.gov.tw/TJI/main/content/ContentLink.aspx?menu_id=3613

- Taylor, A., Chaloupka, F. J., Guidon, E., & Corbett, M. (2000). The impact of trade liberalization on tobacco consumption. In P. Jha & F. J. Chaloupka (Eds.), Tobacco control in developing countries (pp. 343–364). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tobacco International. (2009). JTI gets active in global leaf acquisition. Retrieved July/August, from http://www.tobaccointernational.com/0809/manufacturer.htm

- Tobacco Journal International. (2016, May 23). Deadline set for plain packs, JTI to appeal. Retrieved from http://www.tobaccojournal.com/Deadline_set_for_plain_packs_JTI_to_appeal.53517.0.html

- United Conference on Trade and Development. (2016). World investment forum. Preliminary Programme – as of 13 July 2016. Nairpobi, Kenya 15–22 July 2016. Retrieved from http://unctad14.org/OtherDocuments/UNCTAD14PreliminaryProgramme.pdf

- United Nations. (2016). Treaty collection. WHO framework convention on tobacco control. Retrieved from https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=IX-4&chapter=9&clang=_en

- United States. Federal Trade Commission. (2016). Federal Trade Commission Cigarette Report for 2013. Washington: Federal Trade Commission. Retrieved from https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/federal-trade-commission-cigarette-report-2013/2013cigaretterpt.pdf

- Yamaguchi, Y., & Boyle, M. (2012, May 25). Japan Tobacco buys Belgium’s Gryson for $597 Million. Bloomberg Business. Retrieved from http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2012-05-25/japan-tobacco-buys-belgium-s-gryson-for-597-million

- Yuk, P. K. (2010, May 5). Japan Tobacco’s Gallaher move catches light. Financial Times. Retrieved from http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/6fcc9700-5866-11df-9921-00144feab49a.html#axzz3yUeAcflI

- Weishaar, H., Collin, J., Smith, K., Grüning, T., Mandal, S., & Gilmore, A. (2012). Global health governance and the commercial sector: A documentary analysis of tobacco company strategies to influence the WHO framework convention on tobacco control. PLoS Medicine, 9(6), e1001249. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001249

- Wen, C. P., Peterson, R. A., Cheng, T. Y. D., Tsai, S. P., Eriksen, M. P., & Chen, T. (2006). Paradoxical increase in cigarette smuggling after the market opening in Taiwan. Tobacco Control, 15(3), 160–165. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.011940

- World Health Organization. (2003). Framework convention on tobacco control. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/fctc/text_download/en/

- World Health Organization. (2014). Framework convention on tobacco control. Japan. Fourth Implementation Report. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/fctc/reporting/party_reports/jpn/en/

- World Health Organization. (2015). Fact sheet no. 339. Tobacco. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs339/en/