ABSTRACT

Despite the extensive literature on the tobacco industry, there has been little attempt to study how transnational tobacco companies (TTCs) coordinate their political activities globally, or to theorise TTC strategies within the context of global governance structures and policy processes. This article draws on three concepts from political science – policy transfer, multi-level governance and venue shifting – to analyse TTCs’ integrated, global strategies to oppose augmented packaging requirements across multiple jurisdictions. Following Uruguay's introduction of extended labelling requirements, Australia became the first country in the world to require tobacco products to be sold in standardised (‘plain’) packaging in 2012. Governments in the European Union, including in the United Kingdom and Ireland, adopted similar laws, with other member states due to follow. TTCs vehemently opposed these measures and developed coordinated, global strategies to oppose their implementation, exploiting the complexity of contemporary global governance arrangements. These included a series of legal challenges in various jurisdictions, alongside political lobbying and public relations campaigns. This article draws on analysis of public documents and 32 semi-structured interviews with key policy actors. It finds that TTCs developed coordinated and highly integrated strategies to oppose packaging restrictions across multiple jurisdictions and levels of governance.

Introduction

Outside of the largely closed Chinese market, controlled by the state-owned China National Tobacco Corporation, the global tobacco industry is dominated by four transnational tobacco companies (TTCs) (Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids, Citation2016) – Philip Morris International (PMI), British American Tobacco (BAT), Japan Tobacco International (JTI) and Imperial Tobacco – and is now undergoing a further phase of consolidation (Financial Times, Citation2016). These corporations operate as oligopolies, segmenting national cigarette markets, controlling prices (Gilmore, Citation2012; Hawkins, Holden, Eckhardt, & Lee, Citation2018; Hedley, Citation2007), and employing sophisticated marketing strategies to drive consumption (Hafez & Ling, Citation2005).

A now extensive literature documents TTCs’ efforts to resist regulation and shape policy environments through lobbying, financial contributions, research funding and the formation of front groups (Hurt, Ebbert, Muggli, Lockhart, & Robertson, Citation2009; Savell, Gilmore, Fooks, & Derrick, Citation2014; Smith, Savell, & Gilmore, Citation2013), including efforts to resist and curtail packaging restrictions, such as the Australian government's efforts to introduce standardised (‘plain’) packaging (Chapman & Freeman, Citation2013; Jarman, Citation2015). Partly as a result of these studies, TTCs began to be marginalised from the policy process in many contexts, with Article 5.3 of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) requiring governments to take measures to protect health policy ‘from commercial and other vested interests of the tobacco industry’ (World Health Organizations [WHO], Citation2003). Imperfect implementation of Article 5.3 (Fooks, Smith, Lee, & Holden, Citation2017), however, means political access and influence is still extensive in many settings (Savell et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, as their access to decision makers has eroded, TTCs have developed both more covert and more confrontational strategies to achieve their political objectives. This has involved the use of third parties and cross-industry trade associations (Katz, Citation2015) and legal challenges in an attempt to prevent, amend or delay anti-tobacco measures. This includes cases brought under World Trade Organization (WTO) law (Eckhardt, Holden, & Callard, Citation2015) and bilateral investment treaties (BITs) via investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanisms (Hawkins & Holden, Citation2016). The objective for the industry in mounting legal challenges may not only be to defend sales in the market in question, but to protect their interests globally (Côté, Citation2014; Hawkins & Holden, Citation2016).

Despite the large volume of literature detailing tobacco industry political activities, there is little research explicitly analysing the ability of TTCs to coordinate such activities across multiple jurisdictions (see Holden & Lee, Citation2011 for an exception). This is particularly noteworthy given the now global nature of tobacco control debates and the similar policy challenges which the industry faces in different national markets as a result of international advocacy networks and the FCTC, which sets out best practise for signatory states seeking to implement effective tobacco control policies. This has meant that policies, such as standardised packaging (SP), are often the subject of global debate before being taken up by national policy makers and, once they do come onto the policy agenda in one country, may spread quickly to others. Country-level case studies of the tobacco industry have made an important contribution to understanding TTC activities and have been invaluable in promoting the cause of tobacco control. However, they are unable to explain fully the political strategies of global economic actors operating within the institutional context of a complex system of overlapping global, regional and national regulatory jurisdictions. Furthermore, they fail to capture the precise nature of the policy challenges facing the tobacco industry in this globalised policy environment, or the new opportunities that it affords them to stymie tobacco control measures. A global perspective on TTCs’ strategies is needed to understand in greater depth the ways in which TTCs are adapting and responding to transnational policy processes and multi-level governance structures by coordinating their activities across jurisdictions.

In this article we begin to address the gap in the current literature, adopting a global perspective to understand the ways in which TTCs pursue globally-coordinated political strategies to respond to global policy challenges across multiple jurisdictions. To understand TTC strategy it is necessary to examine the policy context in which they are acting. To do this we draw on three concepts from political science: policy transfer, multi-level governance, and venue shifting. Together, these provide an important analytical toolkit for examining both the policy context in which TTCs operate and the strategies which they pursue. Below, we elaborate on these key analytical concepts, before setting out our methods.

Policy transfer

Advances in information and communication technologies in the last two decades have facilitated processes of ‘policy learning’ (Dunlop & Radaelli, Citation2013) and ‘knowledge transfer’ (Shaxson & Bielak, Citation2012) between countries, as issues and interventions current in one location come onto the agenda in another. This process, often referred to as policy transfer, may be particularly prevalent where transnational mechanisms exist to facilitate this. The process of European integration, for example, facilitates policy transfer between both member states and different levels of decision making within the context of broader processes of Europeanization (Radaelli, Citation2008), although the UK's vote to leave the European Union (EU) indicates that such processes are not irreversible. In the field of tobacco control we have witnessed the emergence of international advocacy and expert networks that have been influential in driving forwards tobacco-control measures globally (Gneiting, Citation2015; Wipfli, Citation2015), whilst the FCTC provides a strong normative framework for such policy transfer.

Multi-level governance

The period since the Second World War has seen the emergence of a highly developed, and overlapping, set of political and legal structures above the level of the nation state, which attempts to manage globalisation through the creation of rules-based systems of supranational governance. Scholars have argued that these developments represent a process of ‘global constitutionalization’, which may disproportionately serve the needs of transnational corporations (TNCs) versus citizens (Hawkins & Holden, Citation2016; Thompson, Citation2012). The creation of new policy-making forums means that decisions affecting a given policy area (such as tobacco control) can potentially be taken in multiple forums and at different levels. The concept of multi-level governance has been applied extensively to examine policy making within the EU (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2001; Marks, Hooghe, & Blank, Citation1996), but is relevant also to other supranational forms of governance (Bache & Flinders, Citation2004; Marks & Hooghe, Citation2004; Stephenson, Citation2013).

Venue shifting

The existence of multiple policy-making venues potentially allows policy actors to influence and challenge policies simultaneously through multiple channels and to engage in venue shifting (Baumgartner & Jones, Citation1993): attempting to move the locus of decision making to the level or forum in which their interests are most likely to be served . Baumgartner and Jones (Citation1991) note that venue shifting may involve the redefinition of the ‘policy image’, and requires mastery of the ‘specialized and arcane language’ and ‘complicated rules’ of alternative venues. This latter point is of particular relevance when considering legal processes, especially those of trade and investment law. Such forms of transnational law offer the possibility for corporations to tackle potentially global policy threats such as SP in a highly effective way. Establishing the incompatibility of packaging restrictions with bodies of law such as these would with one stroke stymie the implementation of such policies across all jurisdictions to which the body of law applies.

The institutional structures of multi-level governance and the processes of policy transfer between jurisdictions thus provide the crucial context within which TTC political strategies must be understood. This context requires TTCs to respond in a coordinated way across jurisdictions if they are to successfully pursue their interests, but if they are able to do so it affords them additional opportunities to oppose public policies via attempts at venue shifting.

We apply these concepts to map the spread of strengthened packaging and labelling requirements across jurisdictions and to examine the coordinated nature of TTCs’ strategies to obstruct such requirements across these jurisdictions. We focus on packaging and labelling requirements because they are at the forefront of contemporary tobacco-control initiatives, have spread extensively between jurisdictions, and are of fundamental importance to TTCs’ commercial strategies. Given the fungibility between manufactured cigarettes (Hurt et al., Citation2009), product differentiation depends on branding and marketing (Hoek et al., Citation2012) and TTCs vehemently oppose restrictions on this. In many contexts, cigarette packs are among the last remaining sites of marketing activity for TTCs. As such, it is an issue of the utmost importance to the tobacco industry. We focus principally on policy developments in Uruguay, Australia – the first country in the world to introduce SP – and the EU. Whilst stopping short of SP, the Uruguay case was an early example of strengthened packaging requirements and was opposed by the industry in similar ways to SP. The EU Tobacco Products Directive (TPD) contained an explicit acknowledgement that member states could implement SP, leading to its introduction initially in Ireland and the UK. Below, we outline our methods, before presenting our findings. Given the significant volume of data provided, the article makes extensive use of tables and figures to demonstrate the concurrent and overlapping policy developments and industry responses across jurisdictions.

Methods

We used both documentary and interview sources to examine connections between policy developments relating to strengthened tobacco packaging requirements in Uruguay, Australia, the UK, Ireland and at EU level. Case selection was purposive, reflecting the jurisdictions in which packaging first entered onto the policy agenda globally and in the European context. Australia was the first country in the world to adopt SP, whilst the UK and Ireland were the first EU member states to follow suit, with policy debates developing in parallel. Ireland also played a key role in the development of the EU TPD during its presidency of the Council of the EU. Developments in Uruguay were a precursor to global debates on SP and show the wider significance of packaging restrictions beyond the specific issue of SP. The article is part of a wider study of tobacco industry influence over policy in the context of globalisation. Here, we draw principally on documentary sources, but use interviews conducted as part of the broader study to add additional details to our timeline of events on SP and the industry responses to these. The objective of the article is not to examine the positions or perceptions of different policy actors (in either the industry or public health sectors), but to take a macro-level view of the development of SP policy globally and the coordinated TTC response to this across national policy spaces and at different levels of governance.

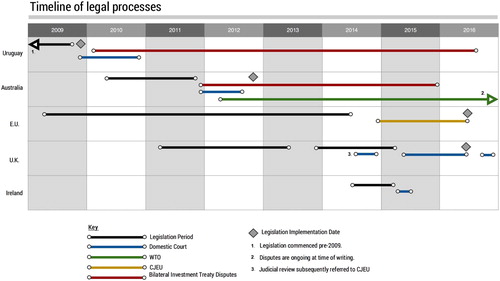

Documents relating to these debates were retrieved by SM from online searches relating to policy debates on tobacco products packaging in those jurisdictions and industry responses to such requirements, including documents relating to litigation in domestic courts and trade and investment disputes in bilateral and regional forums and the WTO. Internet searches were conducted initially using key words relating to the relevant tobacco packaging legislation in each jurisdiction. Thereafter a ‘snowballing’ search technique was used to follow up sources and key phrases cited in the documents initially retrieved. Documents originating from relevant sources such as government departments, courts, international agencies, TTCs or allied organisations, or tobacco-control organisations were included in the study. Using these, we compiled a timeline of the development of tobacco packaging measures across these jurisdictions and TTCs’ responses to these (see and ). Documentary and interview data were used to compile a matrix of industry tactics to oppose packaging requirements in these jurisdictions, in order to summarise and provide examples of the types of tactics used and the venues in which they were deployed (see ).

Table 1. Timeline of significant events relating to strengthened cigarette packaging requirements in different jurisdictions.

Table 2. Cross-jurisdictional comparison of TTC strategies.

Semi-structured interviews (Rubin & Rubin, Citation2011) for the wider project were conducted with government ministers and officials from national governments, officials from the European Commission, Members of the European Parliament, public health advocates and other civil society actors engaged in the policy process. BH undertook 17 interviews related to tobacco control issues at the EU level in Brussels between September 2014 and December 2016 and 15 interviews in Dublin, Edinburgh and via skype between October 2015 and October 2016 to examine policy developments at the national level and the role of the Irish government in the conclusion of the TPD during its Presidency of the Council of the EU in 2014. Skype interviews included representatives of the Australian tobacco control community, but not actors engaged in Uruguayan policy. This reflects both the practical and linguistic challenges of undertaking such interviews and the principle focus of the article on SP.

Interviewees were identified through purposive sampling via a review of documents relating to the TPD and the plans to introduce SP in Ireland, and through online searches of actors and organisations engaged in these policy debates. ‘Snowballing’ was employed to identify further potential contacts from interviewees. Interviews were recorded, transcribed and coded by BH using Nvivo 10 qualitative data analysis software. Interview data are not quoted here due to space constraints, but have been used to inform the analysis and have been triangulated with documentary material.

The global spread of tobacco packaging policy

The entry into force of the FCTC in 2005, and the adoption of guidelines on packaging and labelling by the FCTC Conference of the Parties in 2008, were key moments in the global spread of tobacco packaging regulations. While the FCTC stopped short of mandating plain packaging, the guidelines encouraged governments to consider adopting such measures. The WHO's ‘MPOWER’ package of policy guidance, also developed in 2008, particularly encouraged the use of graphic warning labels (WHO, Citation2008). In 2009 various governments began making concrete moves to legislate on the issue. The EU set in motion the process of revising the TPD, with the issue of packaging and labelling requirements at the head of proposals from the European Commission and a key objective for tobacco-control advocates. In Uruguay, President Tabaré Vazquez introduced legislation stipulating that graphic health warnings would take up 80% of the front and back of cigarette packs (raised from 50%). At the same time, a National Health Task Force in Australia released a report that strongly recommended plain packaging as part of a comprehensive approach.

Following the successful introduction of SP in Australia, it quickly came onto the policy agenda elsewhere, including several EU member states. This represented precisely the kind of policy transfer which TTCs had feared and which they sought to avoid through legal challenges in Australia. Western Europe remains a key market for TTCs, accounting for around 19% of the global cigarette market (Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids, Citation2016) and preventing SP there was strategically important in preventing the wider spread of SP. Ireland became the first country in the EU to enact legislation to introduce SP in March 2015, closely followed by the United Kingdom (UK) and France, with similar measures under consideration in other member-states.

The response of the global tobacco industry

TTC responses are notable for the simultaneous utilisation of multiple legal venues, including both domestic courts and trade and investment disputes systems, in parallel with lobbying and other policy-influencing strategies. The range of tactics utilised by TTCs is presented in and . shows how cigarette packaging policy developed over time across the five jurisdictions examined here and how TTCs responded with various forms of political activity and litigation. It demonstrates how packaging policies developed contemporaneously, but at different speeds, in different jurisdictions and how TTCs responded to these policy initiatives with similar tactics in each context.

distils the tactics used by TTCs into four broad categories – litigation, lobbying, threatening plant closures, and the use of third parties – indicating how specific instances of these were used in each jurisdiction. Activities included direct lobbying of legislators and officials, public relations campaigns to mobilise the support of other businesses and the general public, and attempts to refocus the ‘policy image’ of the issue away from health and onto trade and intellectual property as well as the alleged negative consequences of the policy, such as increased smuggling and associated criminality. The similarity of these tactics across jurisdictions suggests a high level of coordination globally. Attempts to mobilise third parties to flood consultations with negative submissions are just one example of similar tactics used in multiple jurisdictions.

The use of similar forms of litigation in multiple jurisdictions is clear. This involved attacking new policies on multiple fronts using both national and supranational legal mechanisms to challenge proposed laws; identifying the most effective channels for challenging laws; and attempts to establish their general incompatibility with transnational bodies of law that could strike down packaging restrictions simultaneously in multiple jurisdictions. illustrates the overlapping timing of legislative processes and litigation initiated by TTCs in response, suggesting both a process of policy transfer between jurisdictions, and coordination of strategies employed by TTCs in different jurisdictions. The latter include the use of domestic courts in all countries and the simultaneous use of different transnational forms of law, including those of the WTO, ISDS mechanisms and the EU.

In Australia, different forms of litigation were pursued concurrently, with an ISDS dispute under the Australia-Hong Kong Bilateral Investment Treaty (AHKBIT) and a WTO dispute launched by sympathetic countries before Australia's domestic courts had ruled. Similarly, an ISDS dispute was launched in Uruguay at the same time that domestic court action was pursued. In the UK and Ireland, legal action was initiated under both national and EU law, but not under international trade or investment agreements. This mainly reflects the existence of an alternative body of law, overseen by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), through which TTCs could seek to protect their interests. This avenue offered TTCs the normative force of a highly developed and institutionalised supranational legal system with robust enforcement mechanisms. Furthermore, a successful challenge under EU law would invalidate measures across all 28 members-states in one move. Similarly, the WTO and AHKBIT cases against Australia were not only intended to prevent the policy there, but to serve as deterrents to other governments considering similar measures, with the prevarication and delay apparent in the UK case suggesting that this had some effect.

It appears that TTCs used sophisticated forms of venue shifting to oppose SP. PMI, for example, restructured its Asian operations in order to move formal ownership of its Australian company to its Hong Kong subsidiary, thus facilitating its use of the AHKBIT to initiate a dispute with the Australian government. Legal challenges by private actors under EU law are filed through domestic courts in member-states (with referrals from national courts to the CJEU on specific points of EU law possible), although the rulings in these cases are applicable across the EU. This means plaintiffs have the potential to take action against EU law in any one of the 28 member-states in which they have relevant interests. Even with the oversight of the CJEU, decisions by national courts and their interpretation and application of EU law may vary in subtle but important ways for a variety of reasons, including the different juridical traditions in these countries (e.g. the UK system of common law). Thus, there may be perceived advantages for plaintiffs in initiating legal action in one jurisdiction over another.

In the case of the TPD, PMI initiated its legal challenge through the High Court in London. This appears to be part of a strategy by TTCs to test the compatibility of SP with EU law in the jurisdiction most likely to favour their interests. In a legal challenge mounted by JTI against the Irish government's introduction of SP, for example, the company successfully opposed attempts by Ireland to refer the case to the CJEU for a preliminary ruling, with parties agreeing to be bound by the judgement of the European Court in the referral from the London courts in a parallel case. TTCS’ decision to oppose multiple referrals to the CJEU would seem to run counter to their strategy of attacking national policies on multiple fronts. However, in this instance the strategy appears instead to be to seek a single knock-out blow to SP across the EU by attempting to establish its illegality under single market rules, and reflected their belief that this was the arena in which they were most likely to succeed.

Discussion

TTCs’ activities to oppose SP across jurisdictions suggests that these were part of a coherent global strategy. This builds on past findings about TTCs’ strategies in opposing SP (Jarman, Citation2013, Citation2015) and the effects of multi-level governance arrangements in augmenting the power of TNCs to oppose regulation through venue shifting (Holden & Hawkins, Citation2016). The attempt by TTCs to redefine SP as a trade and intellectual property issue, rather than a health issue, constitutes an example both of attempted ‘policy image’ change and of an attempted shift to venues with highly specialised rules, such as the WTO, consistent with Baumgartner and Jones’ early work on venue shifting (Citation1991).

Within the multi-level institutional structures that have emerged in the context of globalisation, TTCs were able to take concurrent action in multiple jurisdictions. For example, tobacco industry actors simultaneously initiated disputes in domestic courts, at the EU level (in the case of the UK and Ireland), at the WTO and via BITs (with Uruguay and Australia). This finding is consistent with previous evidence that TTCs have coordinated political activity across multiple jurisdictions (Holden & Lee, Citation2011). It is also consistent with recent analysis by Reuters journalists, using internal PMI documents and published subsequent to our study, which confirms the globally-coordinated and multi-level nature of PMI's lobbying and legal strategies (Kalra, Bansal, Wilson, & Lasseter, Citation2017). The simultaneous actions against Australia perhaps contradict the expectation that TTCs would act sequentially in order to delay the implementation of legislation for as long as possible. In part, this may reflect the fact that new laws can be implemented even while WTO and BIT cases are proceeding, as was the case in Australia. It may also reflect the fact that defeating SP was so important to the industry that a strategic decision was taken to attempt to block it in Australia, the first country to adopt it, with every means available, or to undermine government responses by forcing them to act on multiple fronts simultaneously. The high costs of defending multiple cases, in terms of money, time and human resources, may have presented a disincentive to proceed. The prospect of facing multiple concurrent legal challenges alongside concerted lobbying campaigns would also deter other resource-limited governments considering similar measures, particularly low and middle-income countries and/or those undergoing austerity programmes. This analysis is supported by previous studies that have identified such ‘chilling effects’ on policy and the explicit objective of corporations to deter others when initiating ISDS cases, including by the tobacco industry (Côté, Citation2014; Fooks & Gilmore, Citation2013; Tavernise, Citation2013).

The strategies employed by TTCs have had mixed success. The recourse to legal challenge underlines their relative marginalisation in policy debates in many jurisdictions. Unable to shape or prevent unfavourable policies as insiders through relationship building and lobbying, they may resort to challenging governments as outsiders in legal forums. So far, legal challenges have failed to prevent the introduction of SP in the countries examined here. This again reflects the shifting political and legal consensus about the harmfulness of smoking, the necessity of effective tobacco-control policies and thus their ability to trump other legal obligations and political objectives such as trade liberalisation. Both the Australia-Hong Kong and Uruguay-Switzerland BIT panels found against PMI, as did courts in all national jurisdictions and at the EU level. At the time of writing, the WTO disputes were still outstanding, although early indications were that here too the panel would find against TTCs.

The failure of cases brought under EU law establishes jurisprudence around SP confirming its compatibility with EU law for any member state considering its adoption. A similar ruling in the ongoing WTO case may also pave the way for yet more countries to act. This is the very opposite of TTCs’ intentions, which sought to block the policy at the global and European levels. However, there have been significant delays in the implementation of SP (e.g. in the UK) which may have stemmed in part from TTCs’ actions, whilst packaging requirements in the TPD were watered down from the original proposals. The various legal actions may also have exerted a deterrent or ‘chilling’ effect on other governments considering strengthened tobacco-control laws while these issues remained sub judice (Hawkins & Holden, Citation2016).

Conclusion

This article has begun to address the gap in the literature on TTC behaviour by establishing the importance of the global institutional and policy-process context within which TTC strategies must be crafted and to which they must respond. Understanding the context of multi-level governance and the interconnected nature of policy debates across jurisdictions, and TTCs’ strategies in response to this, is vital both for policy analysts seeking to understand policy outcomes and practitioners attempting to implement effective tobacco-control policies. Drawing on three key concepts from political science – policy transfer, multi-level governance and venue shifting – we have demonstrated how effective public health policy initiatives can travel quickly between different jurisdictions, but also how TTCs have acted in a coordinated manner globally to take advantage of supranational governance structures to challenge these policies via multiple litigation and lobbying processes. This underlines both the effectiveness of international collaborations between policy makers and advocates and the need to coordinate policy responses at different levels of governance. Whilst TTCs have been unsuccessful in blocking stronger packaging requirements thus far, their concerted and coordinated opposition makes policy innovation costly for governments, can substantially delay policy adoption and implementation, and may exert a ‘chilling effect,’ particularly on less well-resourced governments. Furthermore, the possibility that a specific measure can be ruled illegal at the European or even global level by a single decision underlines the need for careful drafting of international agreements and the firm establishment of the norm that health considerations be granted priority over other objectives, such as trade liberalisation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jed Meers for his assistance with the formatting of .

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Benjamin Hawkins http:\\orcid.org\0000-0002-7027-8046

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bache, I., & Flinders, M. (2004). Multi-level governance and the study of the British state. Public Policy and Administration, 19, 31–51. doi: 10.1177/095207670401900103

- Baumgartner, F. R., & Jones, B. D. (1991). Agenda dynamics and policy subsystems. The Journal of Politics, 53, 1044–1074. doi: 10.2307/2131866

- Baumgartner, F. R., & Jones, B. D. (1993). Agendas and instability in American politics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids. (2016). The global cigarette industry [Online]. Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids. Retrieved from http://global.tobaccofreekids.org/files/pdfs/en/Global_Cigarette_Industry_pdf.pdf

- Chapman, S., & Freeman, B. (2013). Removing the emperor’s clothes: Australia and tobacco plain packaging. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

- Commonwealth of Australia. (2009). Tobacco Control in Australia: making smoking history. Retrieved March 2, 2018, from http://www.health.gov.au/internet/preventativehealth/publishing.nsf/Content/96CAC56D5328E3D0CA2574DD0081E5C0/$File/tobacco-jul09.pdf

- Côté, C. (2014). A chilling effect? The impact of international investment agreements on national regulatory autonomy in the areas of health, safety and the environment. London: London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE).

- Dunlop, C. A., & Radaelli, C. M. (2013). Systematising policy learning: From monolith to dimensions. Political Studies, 61, 599–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00982.x

- Eckhardt, J., Holden, C., & Callard, C. D. (2015). Tobacco control and the world trade organization: Mapping member states’ positions after the framework convention on tobacco control. Tobacco Control. Retrieved from http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/25/6/692

- Financial Times. (2016). BAT lights way for further consolidation in big tobacco [Online]. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/7f97be50-97a0-11e6-a1dc-bdf38d484582

- Fooks, G., & Gilmore, A. B. (2013). International trade law, plain packaging and tobacco industry political activity: The trans-pacific partnership. Tobacco Control. Retrieved from http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/early/2013/06/19/tobaccocontrol-2012-050869

- Fooks, G., Smith, J., Lee, K., & Holden, C. (2017). Controlling corporate influence in health policy making? An assessment of the implementation of article 5.3 of the world health organization framework convention on tobacco control. Globalization and Health, 13, 597. doi: 10.1186/s12992-017-0234-8

- Gilmore, A. B. (2012). Understanding the vector in order to plan effective tobacco control policies: An analysis of contemporary tobacco industry materials. Tobacco Control, 21, 119–126. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050397

- Gneiting, U. (2015). From global agenda-setting to domestic implementation: Successes and challenges of the global health network on tobacco control. Health Policy and Planning. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czv001

- Hafez, N., & Ling, P. M. (2005). How Philip Morris built Marlboro into a global brand for young adults: Implications for international tobacco control. Tobacco Control, 14, 262–271. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.011189

- Hammond, D. (2014). Standardized packaging of tobacco products evidence review prepared on behalf of the Irish Department of Health. Retrieved March 2, 2018, from http://health.gov.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/2014-Ireland-Plain-Pack-Main-Report-Final-Report-July-26.pdf

- Hawkins, B., & Holden, C. (2016). A corporate veto on health policy? Global constitutionalism and investor–state dispute settlement. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 41, 969–995. doi: 10.1215/03616878-3632203

- Hawkins, B., Holden, C., Eckhardt, J., & Lee, K. (2018). Reassessing policy paradigms: A comparison of the global tobacco and alcohol industries. Global Public Health, 13, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2016.1161815

- Hedley, D. (2007). Consolidation endgame in sight—but is there one more big throw of the dice [Online]. Euromonitor. Retrieved from http://www.euromonitor.com/Consolidation_endgame_in_sight_but_is_there_one_more_big_throw_of_the_dice

- Hoek, J., Gendall, P., Gifford, H., Pirikahu, G., McCool, J., Pene, G., … Thomson, G. (2012). Tobacco branding, plain packaging, pictorial warnings, and symbolic consumption. Qualitative Health Research, 22, 630–639. doi: 10.1177/1049732311431070

- Holden, C., & Hawkins, B. (2016). Health policy, corporate influence and multi-level governance: The case of alcohol policy in the European Union’. In N. Kenworthy, R. Mackenzie, & K. Lee (Eds.), Case studies on corporations and global health governance: Impacts, influence and accountability (pp. 145–158). London: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Holden, C., & Lee, K. (2011). ‘A major lobbying effort to change and unify the excise structure in six central American countries’: How British American Tobacco influenced tax and tariff rates in the central American common market. Globalization and Health, 7, 15. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-7-15

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2001). Multi-level governance and European integration. Boulder, CO: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Hurt, R. D., Ebbert, J. O., Muggli, M. E., Lockhart, N. J., & Robertson, C. R. (2009). Open doorway to truth: Legacy of the minnesota tobacco trial. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 84, 446–456. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60563-6

- Jarman, H. (2013). Attack on Australia: Tobacco industry challenges to plain packaging. Journal of Public Health Policy, 34, 375–387. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2013.18

- Jarman, H. (2015). The politics of trade and tobacco control. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kalra, A., Bansal, P., Wilson, D., & Lasseter, T. (2017). Inside Philip Morris’ campaign to subvert the global anti-smoking treaty [Online]. Reuters. Retrieved from http://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/pmi-who-fctc/?utm_medium=Social&utm_source=Twitter#sidebar-vignette-playbook

- Katz, A. (2015). The influence machine: The US chamber of commerceand the corporate capture of American life. New York, NY: Spiegel and Grau.

- LALIVE. (2009, July 23). Why plain packaging is in violation of WTO Members' international obligations under TRIPS and the Paris Convention, Truth Tobacco Industry Documents, Bates no. JB2818. Retrieved October 2017, from http://www.tobaccolabels.ca/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Philip-Morris-Intl-Why-Plain-Packaging-is-in-Violation-of-WTO-Members%E2%80%99-International-Obligations-2009.pdf

- Marks, G., & Hooghe, L. (2004). Contrasting visions of multi-level governance. In I. Bache & M. Flinders (Eds.), Multi-level governance (pp. 15–30). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Marks, G., Hooghe, L., & Blank, K. (1996). European integration from the 1980s: State-centric v. Multi-level governance. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 34, 341–378.

- Radaelli, C. M. (2008). Europeanization, policy learning, and new modes of governance. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 10, 239–254. doi: 10.1080/13876980802231008

- Rubin, H. J., & Rubin, I. S. (2011). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Savell, E., Gilmore, A. B., Fooks, G., & Derrick, G. E. (2014). How does the tobacco industry attempt to influence marketing regulations? A systematic review. PloS One, 9, e87389. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087389

- Shaxson, L., & Bielak, A. (2012, April). Expanding our understanding of K* (KT, KE, KTT, KMb, KB, KM, etc.). A concept paper emerging from the K* conference held in Hamilton, ON. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08a6e40f0b649740005ba/KStar_ConceptPaper_FINAL_Oct29_WEBsmaller.pdf

- Smith, K. E., Savell, E., & Gilmore, A. B. (2013). What is known about tobacco industry efforts to influence tobacco tax? A systematic review of empirical studies. Tobacco Control, 22, e1–e1. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050098

- Stephenson, P. (2013). Twenty years of multi-level governance: ‘Where does it come from? What is it? Where is it going?’ Journal of European Public Policy, 20, 817–837. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2013.781818

- Tavernise, S. (2013). Tobacco firms’ strategy limits poorer nations’ smoking laws [Online]. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/13/health/tobacco-industry-tactics-limit-poorer-nations-smoking-laws.html?_r=0

- Thompson, G. (2012). The constitutionalization of the global corporate sphere? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wipfli, H. (2015). The global war on tobacco. Baltimore, ML: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- World Health Organizations (WHO). (2003). WHO framework convention on tobacco control [Online]. Retrieved from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2003/9241591013.pdf?ua=1

- World Health Organizations (WHO). (2008). MPOWER: A policy package to reverse the tobacco epidemic. Geneva: WHO.