ABSTRACT

Worldwide, interest is increasing in community-based arts to promote social transformation. This study analyzes one such case. Ecuador's government, elected in 2006 after decades of neoliberalism, introduced Buen Vivir (‘good living’ derived from the Kichwan sumak kawsay), to guide development. Plans included launching a countrywide programme using circus arts as a sociocultural intervention for street-involved youth and other marginalised groups. To examine the complex ways by which such interventions intercede in ‘ways of being’ at the individual and collective level, we integrated qualitative and quantitative methods to document relationships between programme policies over a 5-year period and transformations in personal growth, social inclusion, social engagement and health-related lifestyles of social circus participants. We also conducted comparisons across programmes and with youth in other community arts. While programmes emphasising social, collective and inclusive pedagogy generated significantly better wellbeing outcomes, economic pressures led to prioritising productive skill-building and performing. Critiques of the government's operationalisation of Buen Vivir, including its ambitious technical goals and pragmatic economic compromising, were mirrored in social circus programmes. However, the programme seeded a grassroots social circus movement. Our study suggests that creative programmes introduced to promote social transformation can indeed contribute significantly to nurturing a culture of collective wellbeing.

Introduction

The election of a national government in Ecuador in 2006 that dubbed itself the ‘Citizens’ Revolution’ responded to the demand for social change that was sweeping Latin America. The new Ecuadorian Constitution enacted in 2008 proposed Buen Vivir as the guiding principle for government policies (Government of Ecuador, Citation2008), with national development plans (Secretaria Nacional de Planificación y Desarrollo [SENPLADES], Citation2009, Citation2013), emphasising wellbeing beyond conventional economic indicators. Buen Vivir translates roughly to ‘good living’ derived from the Kichwa Sumak Kawsay, albeit not without considerable controversy (Macas, Citation2010). The Buen Vivir Plan set the stage for one of the world's largest government-sponsored programmes using circus arts as a sociocultural intervention with communities in precarious situations.

Popularised in the later decades of the twentieth century, there are now over 350 ‘social circus’ programmes around the world (Cirque du Soleil home page) -using a combination of juggling, clowning, acrobatics, aerials, and balancing disciplines amongst others, to promote inclusivity, trust, and creative expression (Spiegel, Citation2014). While many programmes approach circus as a means of promoting psychological and social transformation of participants, some programs focus on artistic training for economically marginalised groups, with the professionalisation of its participants – or at least labor and economic inclusion – increasingly constituting ‘success’, others some programs focus particularly on artistic training for economically marginalised groups.

Building from grassroots circus and theatrical initiatives already underway, Circo Social Ecuador materialised in April 2011 through an agreement between the then Vice-President, Lenin Moreno (now President) and several municipalities in Ecuador, followed a month later by an accord with the giant Montreal-based transnational circus company, Cirque du Soleil (Spiegel, Citationin press-b; Spiegel, Breilh, Campana, Marcuse, & Yassi, Citation2015).Footnote1 While Cirque du Soleil's branding as well as the ‘services’ it offers communities have been frequently problematised (Hurley & Léger, Citation2008; Leroux, Citation2012; Leslie & Rantisi, Citation2016), it remains the world's largest diffuser of social circus pedagogy. Drawing on the social circus model developed by this transnational entertainment corporation, the extensive Ecuadorian State support for this national community arts programme was remarkable for the ways in which it explicitly aims to promote a transformation in social and cultural logic. According to Mr. Moreno, Circo Social Ecuador was designed to: (1) create a cultural alternative for empowering vulnerable communities; (2) support protection of children and adolescents at-risk; (3) bring together young people to promote social movements and strengthen their sense of national cultural identity in a manner appropriate to each locality; (4) facilitate integrative activities with other national social projects as well as public and private initiatives; and (5) develop values of solidarity, participation, discipline, concentration, cooperation, self-esteem, personal and collective development, and a sense of belonging. Importantly, the goal was also explicitly to ‘achieve a multiplier effect throughout the country’ (Programa Circo Social Ecuador, Citation2012).

As practices are appropriated and re-appropriated, disbursed through global networks of ‘development programmes’, the ‘beneficiaries’, and indeed, even the ‘practitioners’ of such circulating practices are caught in the nexus of the institutional cultures through which they encounter and diffuse the arts deemed ‘transformative’. As Homi Bhabha (Bhabha, Citation2012) famously theorised, this practice of engaging with new images and visions can involve cultural submission, cultural resistance, or sometimes both simultaneously, particularly within the context of colonial practices and cultural hierarchies. Commenting on the new social vision of the Ecuadorian government, cultural theorist Catherine Walsh queried:

It is a project that entails, and demands, the creation of radically different conditions of existence and of knowledge, power, and life, conditions that could contribute to construct really intercultural societies, where the values of complementarity, relationality, reciprocity, and solidarity get to prevail … . [But] Are they willing to think and act with the historically subordinated and marginalized peoples; to unlearn their uninational, colonial, and monocultural learning; and to relearn to learn so as to be able to complement each other, and co-exist and co-live ethically? (Walsh, Citation2009, p. 235, 212)

The extent to which various visions of social circus are being actualised worldwide, under what conditions, and with what challenges has only begun to be examined. Gains have been found in helping participants to ‘reconnect to their bodies’ and increase their physical expression and mobility (Kelaher & Dunt, Citation2009; Loiselle, Citation2015; Spiegel & Parent, Citation2017), ‘feel empowered’ or ‘self-confident’ (Archambault, Citation2014; Kelaher & Dunt, Citation2009; Loiselle, Citation2015; McCaffery, Citation2011; Savolainen & Suoniemi, Citation2015; Spiegel & Parent, Citation2017; Trotman, Citation2012), as well as increase their general ‘sense of happiness’, wellbeing or ‘fun’ (Cadwell & Rooney, Citation2013; Kinnunen, Lidman, Kakko, & Kekäläinen, Citation2013; Trotman, Citation2012). Improvements in interpersonal skills, intercultural relations, and ‘social participation’ or ‘engagement’ are also being reported and analysed (Kelaher & Dunt, Citation2009; Kinnunen et al., Citation2013; Loiselle, Citation2015; Savolainen & Suoniemi, Citation2015; Spiegel, Citation2016b; Spiegel & Parent, Citation2017; Trotman, Citation2012). In studying the role of the Machincuepa social circus in Las Aguilas, Mexico (McCauley, Citation2011) – a community described as struggling with the impacts of poverty, including open drug use in the streets – McCauley stressed that social circus offered an otherwise non-existent ‘safe’ gathering place, thus providing youth with an essential space to combat alienation and share experiences and resources.

To examine the impacts of Ecuador's social circus programme, we begin by discussing the Ecuadorian context followed by a description of our methodology and research techniques. We then proceed to (1) analyze how political ideologies and social discourses affected the operationalisation of social circus in the various municipalities; (2) assess how these policies and programmes shaped the ways in which participants were able to access and control the conditions of their own lives and that of their communities; and (3) examine how the implementation of this sociocultural initiative influenced personal growth as well as individually and collectively constructed behaviours that impact how health and well-being are experienced and transformed. We conclude by analysing the significance of our study for deepening understandings of the relationships amongst politics, social policy and the ways in which community arts programmes impact collective health, drawing parallels between the operationalisation of Buen Vivir and Ecuador's social circus programme itself.

Toward a post-colonial methodology: a community-based transdisciplinary approach

The neoliberal economic model that dominated Ecuador from the 1990s and into the twenty-first century led to poverty rates exceeding 60% (Weisbrot, Johnston, & Merling, Citation2017). Despite the new government's considerable investment in infrastructure and social services including health and education (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos (INEC), Citation2011), and despite greater attention to the rights of children and youth (UNICEF, Citation2002), 70% of youths were still living in poverty by 2011 (Carriel Mancilla, Citation2012). In this socioeconomic context, Moreno saw the potential of social circus to improve health and social outcomes.by:

Creating a cultural alternative for empowering vulnerable communities … and developing values of solidarity, participation, discipline, concentration, cooperation, self-esteem, personal and collective development, and a sense of belonging.

Amidst these debates, our study sought to investigate how Ecuador's social circus programme has been altering ways of interacting, creating, realising potential and accessing collective resources needed for health and wellbeing. Our analysis adopts the notion of ‘social determination of health’ whereby health is conceptualised as a complex multidimensional dialectic deeply rooted in social and political processes in which social groups have ‘ways of living’ defined by their position in class/gender/ethno-cultural relations, in turn expressed in individual lifestyles and bio-psychological embodiments (Breilh, Citation2010, Citation2013; Krieger, Citation2011). The social determination of health approach, in contrast to the more traditional social determinants of health analytic framing, focuses attention not merely on the discrete factors or conditions that impact health and wellbeing (e.g. nutrition, housing, education, income, etc.), but rather on the structural processes at the societal level that lead to these social inequities, and the interrelationships among these (Breilh, Citation2008). The overall research objective of the study was thus to better understand how social policies, as well as their associated social interventions employing the arts (sociocultural interventions), intercede in the dominant modes of constructing ways of being and lifestyles at the individual and collective level.

Building on a longstanding collaboration between Ecuadorian and Canadian researchers, the study was conducted over an almost 5-year period beginning in 2013, drawing in researchers from the arts, humanities, health and social sciences. The metaphor of the rhizome (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987) characterises the way in which we merged disciplines (Boydell, Spiegel, & Yassi, Citationin press); dissimilar from the root of a tree, a rhizome has no beginning and ending, only points connecting to other points with multiple points of entry. This metaphor of the rhizome reflects how our study blended epistemologies; its relational focus (Fox & Alldred, Citation2015) allowed for creativity, connection, experimentation and multiplicity in thinking to flourish (Fornssler, McKenzie, Dell, Laliberte, & Hopkins, Citation2014). Drawing from the lead author's previous studies of social circus in Quebec (Spiegel, Citation2015, Citation2016b; Spiegel & Parent, Citation2017), we also combined our interdisciplinary methods with the potentialities of community artists, including Ecuadorian author BO who trained instructors for Circo Social Ecuador [CSE]) in 2012 and had been the pedagogical director of CSE for 5 months in 2013, to analyze how transformations in ‘ways of living’ and lifestyles of youth were being effected by their participation in social circus. By interacting extensively and sharing data from one source to inform the others, we also sought to analyze the extent to which the processes operationalised embodied the vision and/or constraints associated with Buen Vivir in Ecuador and/or surfaced new potential for social transformation.

Our qualitative data gathering methods included participant observation in which lead author JBS observed social circus training, participating in the workshops where she could, and interacted with participants and instructors to understand their experiences, their concerns, their joys, and the challenges they faced. Other team members also visited the programmes in the various municipalities. Discussions were held with personnel from Cirque du Soleil, Ecuador's Vice Presidency and Ministry of Culture, as well as municipal programme directors, social workers, coordinators and instructors. JBS also conducted 16 confidential interviews to supplement the group discussions that involved well over 100 participants in these various sessions.

We analysed documents, training materials, programme plans and a myriad of information that helped us understand how and the extent to which the programmes were meeting goals. The considerable expertise of co-author BOC regarding the history of the programmes, the pedagogy and the challenges, facilitated appreciation of the nuances of each situation, always conscious of positionality. Indeed, we adopted a high degree of reflexivity (Rice & Ezzy, Citation1999), well aware that research perspectives are continuously bound up not only with academic biographies but also with the ‘interpersonal, political and institutional contexts in which researchers are embedded’ (Mauthner & Doucet, Citation2003).

The quantitative component of the study consisted of a large retrospective-prospective longitudinal survey, with comparison group, specifically including 254 youth or young adults who were participating – or had participated – in social circus across the country, and 167 youths enrolled in various other art and cultural activities in the Casa Metro youth centres in Quito's metropolitan area, including 63 involved in collective creative practices generally more physically demanding – such as personal defense, dance, break dancing, capoeira, and parkour – as well as 104 participating in other pursuits – including music, guitar, percussion, art, language studies and other activities. We adapted questionnaires that had been used in other studies by JBS and included questions focused specifically on understanding the impact of community-based creative practice on the emotional and physical wellbeing of participants. We asked respondents to compare how they remember feeling, or what their situations were, before they began social circus or their other arts-related activities, compared to afterwards, using a retrospective post-then-pre questionnaire design (Rockwell & Kohn, Citation1989), to avoid ‘loss to follow-up’ that characterises many studies of street-involved youth (Hampshire & Matthijsse, Citation2010). The questionnaire included constructs of personal growth (Robitschek, Citation1998) and social inclusion, understood as ‘the means, material or otherwise, to participate in social, economic, political and cultural life’ (Huxley et al., Citation2012). In addition, it comprised questions that probed social engagement and health-related outcome (nutrition, fitness, substance use, housing, income, etc.), as well as an index of social class (Breilh, Campaña, Felicita, & al., Citation2009).Footnote2

The analysis presented here is drawn from the larger study1 that further incorporated arts-based research methods (Marcuse, Fels, Boydell, & Spiegel, Citationin press), as well as analysis of the pedagogical philosophy and practices (Fels & Ortiz Choukroun, Citationin press). Several workshops served as sites of encounter at once providing a space for sharing and problematising research techniques, modes of study and ways of developing and experiencing praxis. The institutional hierarchies of knowledge, the ways in which they continue to stratify social and professional participation, and the complexity of overcoming colonial dynamics were, however, omnipresent; in our data collection and analysis across methods we sought to mitigate and transforms these dynamics as much as possible.

Ecuador's national social circus programme: operationalisation of new social policy

In history we were conquered, we also had bad governments that suppressed communities. … By revitalizing the spiritual part of a person, as with social circus, we can start to work to improve self-esteem … have an Ecuadorian point of view not from a submissive stance but from a position of being able and capable of creating and proposing new ideas and change. … Depending on who is in charge of the social circus [program] it can just be a local spectacle and the essence of social change could be completely lost. We [the central government] must look after preventing that. Official from the Ecuadorian Ministry of Culture and Heritage, November 2014

A social circus programme driven so strongly by a national government was unprecedented, as was the level of investment of public funds.Footnote3 This provided an opportunity to promote values consistent with the 2013–2017 Plan Nacional Buen Vivir, such as ‘social inclusion, self-esteem and profound collective confidence in the country’ (SENPLADES, Citation2013), with government documents suggesting that social circus could act ‘as a powerful lever of social transformation’. The emphasis on social principles contrasts with goals in social circus programmes elsewhere; for example, the partnership of La Tarumba in Perú, Circo del Mundo in Chile, and Circo Social del Sur in Argentina, with the Inter-American Development Bank and Cirque du Soleil, describes itself as ‘an alternative to improve the employability … . training of entrepreneurship and … a model to help lower the rate of youth unemployment in the region’ (MIF, Citation2013). While CSE also offers participants the opportunity for professionalisation and decent work, the declared focus is on promoting personal and social development as a form of social transformation.

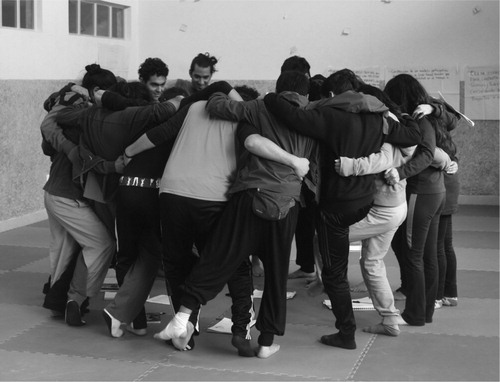

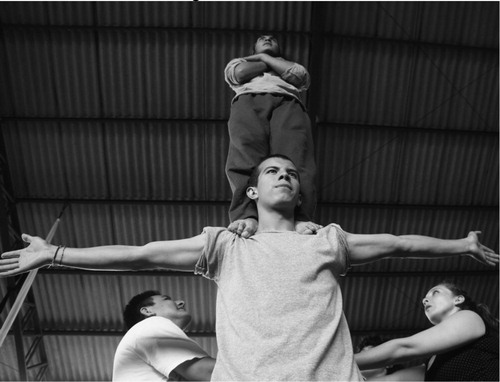

There are four main activities in CSE: First, instructor training () to prepare instructors with the social pedagogy needed to be effective mentors. Secondly, réplicas – workshops offered to groups of usually up to 20 participants in sessions once to three times per week, lasting about 3–4 months conducted either at the location of a partner civil society organisation or onsite at a municipal venue ( and ); these workshop sessions are the backbone of the programme. Third are the ‘open circus’ sessions where instructors and volunteers (usually youth with advanced training) work with children and other members of the public using circus arts ( and ), often involving hundreds of participants; and fourthly performances/demonstrations ( and ). However, the relative importance of each of these activities varies by programme site, as do the target populations prioritised and the pedagogical structure, in turn influenced by the political stances of the various governmental authorities (see ). Notably, misperceptions of the objectives of social circus were exacerbated by the influence of Cirque du Soleil imagery (Fricker, Citation2016; Hurley & Léger, Citation2008) creating inappropriate expectations of marginalised groups performing in large costume-clad majestic productions. Moreover, the grandiose (never-achieved) government plan to mount a ‘big tent’ in each city (against the advice of its social circus pedagogy advisors) distracted considerably from the programme's social objectives (Spiegel, Ortiz Choukroun, Campaña, & Yassi, Citationin press). In light of these discrepancies, we ask, was social circus indeed encouraging broader co-construction of the cultural life of the country across ethnic and class divisions? And if so, what were the broader well-being implications of the shift?

Photo 1. Volunteers in Cuenca learning a group confidence-building exercise, reflecting the social pedagogy (2013). Photo credit: B. Ortiz Choukroun.

Photo 2. Instructor/volunteer training session in Loja discussing pedagogical approaches (2014); the social theory behind each exercise is taken quite seriously. Photo credit: A. Compaña.

Photo 3. Demonstration by instructors/volunteers in Tena at the culmination of a training session (2012). Photo courtesy of Circo Social Tena.

Photo 4. Réplica with youth in Loja; the instructor adapts the exercise on silks to the level of the participants (2015). Photo credit: B. Ortiz Choukroun.

Photo 5. Social worker and volunteer in replica in Cuenca. (2013); Cirque du Monde pedagogy emphasises the importance of direct involvement of social workers in all the workshops. Photo credit: B. Ortiz Choukroun.

Photo 6. Children from la Fundación REMAR Ecuador enjoying an Open Circus event by Circo Social Quito 2013; an estimated well over 50,000 children have attended Open Circus or social circus performance events across Ecuador. Photo credit: B. Ortiz Choukroun.

Photo 7. Youth volunteers working with children in an Open Circus event of Circo Social Quito, REMAR, 2013. Photo credit: B. Ortiz Choukroun.

Photo 8. Volunteers from Circo Social Ecuador performing with international circus artists in Parque Calderón in Cuenca (2013). Photo credit: B. Ortiz Choukroun.

Photo 9. Juggling, clowning, acrobatics, and collective acrobatics (pyramid) by Circo Social Quito and Circo Social Cuenca volunteers in 2013 rehearsing for a show at the inauguration of the big tent in Cuenca (2013). Photo credit: B. Ortiz Choukroun.

Table 1. Socioeconomic and political profile, social policies and pedagogy, programme metrics and observations/outcome overall and by city.

Social reach, cultural participation, and collective wellbeing

The driving force behind dominant theories of change related to social circus is the conviction that embodying collective creation, collective risk-taking and collective trust builds solidarity and propels positive socially transformative actions. It is hoped that when those who have been marginalised from social, cultural and economic access create together in this way, social inclusion will improve, thereby increasing social equity and improving collective living conditions (Spiegel & Parent, Citation2017). This desire is not unique to Ecuador's programme, but rather anchored in the very vision for social circus disseminated by Cirque du Soleil's social citizenship programme, Cirque du Monde, operating in over 80 communities globally (Cirque du Monde, Citation2014). However, brought to Ecuador, where disparity propelled by decades of neoliberalism is stark, and adapted to a new paradigm that aimed to trigger transformative mobilisation to redress social inequities, these objectives take on a particular tenor.

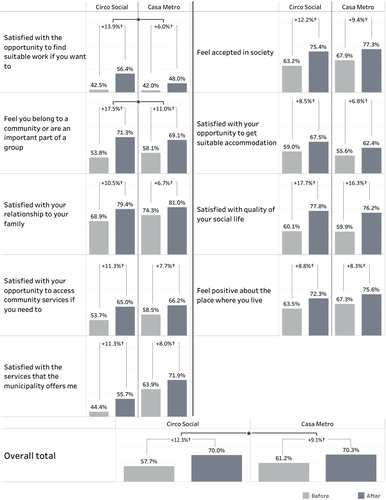

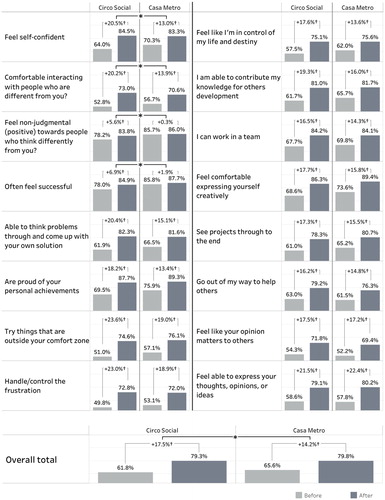

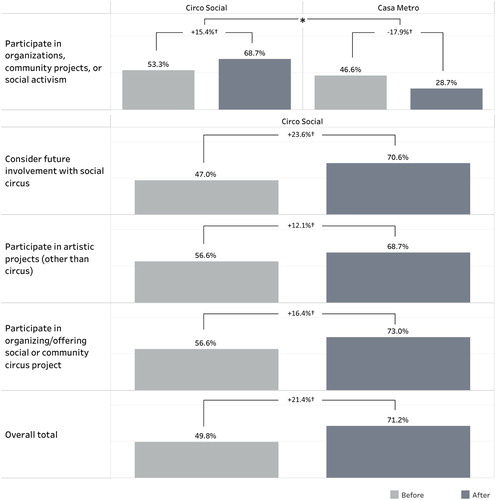

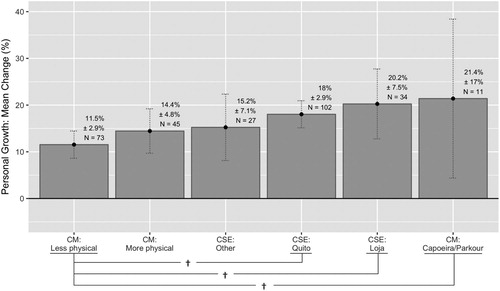

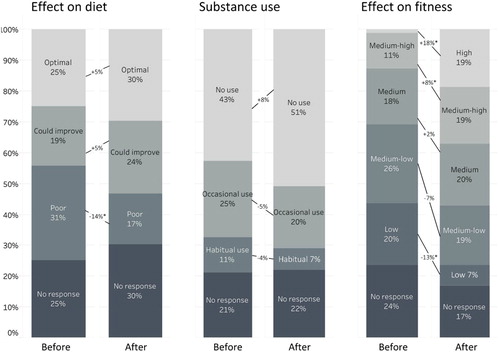

Our survey showed significant transformations in educational goals and career prospects amongst social circus participants, as well as in softer indicators of social inclusion such as ‘satisfied with social life’ and ‘sense of group-community belonging’ (). However, living conditions and food security were only slightly improved (8% increase in ‘satisfaction with housing’; 39% still reporting inadequate diet), understandable given that such changes require longer-term effort at the macro societal level. Participants in other community arts (Casa Metro) also showed significant improvements, however social circus participants reported significantly more impact than their counterparts in other arts and cultural activities for both social inclusion and personal growth (). Social circus participants also significantly increased their social engagement while those from Casa Metro did not. Indeed social circus respondents scored higher on all four social engagement questions after participation in social circus, with a significant upsurge in ‘participate in organizations, community projects or social activism’ (), suggesting this programme may indeed be spurring activism needed for macro-level social transformation.

Figure 1. Changes in social inclusion pre versus post beginning social circus, ages 12–39, comparing respondents from Circo Social with respondents from Casa Metro programmes. † Paired t-test shows the average participant response improved significantly with 95% confidence; * T-test shows that the average change between programmes is significantly different, with 95% confidence.

Figure 2. Personal growth mean comparison pre versus post participation and between Circo Social Ecuador and Casa Metro (ages 12–39). †,* -see legend for .

Figure 3. Social engagement mean comparison pre versus post participation of various indictors, and between Circo Social Ecuador and Casa Metro (ages 12–39) overall. †,* -see legend for .

Interestingly, parkour and capoeira had results that were similar to social circus for personal growth and social inclusion, and less consistent with findings for the other Casa Metro programmes (), an observation likely explained by similarities in the activities and profile of youth they tend to draw. Our interviews with the Casa Metro director suggested that, like social circus, parkour and capoeira attracted youth from lower socio-economic backgrounds, and/or who are interested in collective counter-cultural activities, consistent with the literature on youth involvement in these art forms (Ugolotti & Moyer, Citation2016), including youth attraction to social circus (Hurtubise, Roy, & Bellot, Citation2003). Scholars discuss youth engagement with capoeira and parkour as the medium through which struggles about belonging and citizenship take place (Ugolotti & Moyer, Citation2016), describing how participants ‘challenge dominant regimes of representation, while also attempting to improve their life conditions and reach their personal goals’.

Figure 4. Social inclusion change, comparison by physical level, ages 18–39. † T-test shows a significant different between groups, each individual t-test having 95% confidence; none of the differences reach statistical significance for age-group 12–39, nor using the more rigorous Tukey test, nor when controlling for differences in baseline values within the groups. (It is noteworthy that CS Loja had significantly lower baselines compared to all other groups except the Capoeria/Parkour group).

It is important to note that the socio-cultural and political conditions varied substantially between the Ecuadorian cities that hosted social circus programmes, manifesting in marked differences between their programmes, and thus the impacts achieved varied, as shown in . The target population for Circo Social Quito, which we studied most intensively, fluctuated considerably over the years. In November 2014, the coordinator described their participants as follows:

It is diverse. Many of them come because they don't have a place to go and then they stay because they like it; others like circus arts a lot and come to exercise and learn techniques. People are from different social classes […] including street children who were [performing] at the traffic lights or kids in school who like arts and want to spend the evening, or kids who have decided to become circus artists and want to become professional.

As explained by a former social worker with Circo Social Quito interviewed in October 2015, the changes since the programme began in 2011 had far reaching implications on programme demographics:

Most of the young people [recruited in the early years] were living in the streets, and did not want to study or improve their quality of life . … They consumed drugs, alcohol,[and were] involved in that world. So that's what the initial project was about, trying to help them out of those high-risk situations . … The new kids, from what I have seen, come from a different background . … It's no longer because they are in a vulnerable situation … I think that reflects the current vision of the program … , Before it felt like a family, I am not sure what they [the participants] think now … Maybe it's just like another program.

Relationships between individual and collective wellbeing

The impact of the social circus in my life is integral. It made me a more humanitarian, empathetic and proactive person. Female participant, Loja

Figure 5. Attitudes and practices related to diet, substance use and physical fitness at baseline and after participation, for participants in a Circo Social Ecuador programme (ages 12–39). * Chi-squared tests show proportions before and after are significantly different with 95% confidence.

I don't even want to remember what it was like before. It was very bad. I had no future – [I was an] enemy of my own family and myself . … It [social circus] made me love myself and my family. It was a time to re-evaluate. I became a better human being, more sensible. Because we are circus artists we can express our feelings when we perform, this enables us to communicate our deepest emotions, sadness, happiness, crying … . All the things that have happened to you as a child and throughout our lives, I really like that. It's almost like falling into an unconscious state and in that state you are able to let go of those deep feelings, no matter what those are. Male participant, Quito

Travel and be able to have that experience with social circus, go to other places and try with a difference audience /demographics and culture. It's very interesting to see people how they really are and learn to respect that as well.

The objective is to transform each individual and gradually change society. Learn not to judge others for their condition, appearance or way of thinking. It's a journey … I feel it [social circus] has helped me find other alternatives, roads. I feel a need to communicate with society … . Before I had no interest at all in dealing with society, I wanted to be left aside. Now I am very interested in children. … When you recognize yourself as an individual, then you can be part of society and have some sort of impact. Change starts with oneself.

Collective culture, neoproductivism, and the politics of transition

A major critique of the government's operationalisation of its Buen Vivir strategy is that it relies too heavily on a neo-productivist logic that prioritises product and performance over respect for the processes and contributions of all (Alonso González & Vázquez, Citation2015). Much of the tension that emerged in the social circus programme could be linked to the uneasy relationship between the ways in which the well-being of the ‘collective’ and of ‘society’ became linked to the extent to which participants, often economically and otherwise vulnerable, were expected to perform for the ‘greater good’.

Given the importance of economic resources, we asked why ‘volunteers’ who work with children in the réplicas, or who perform at events at the request of the Municipality, are not provided with financial remuneration. In response, the coordinator of the Quito programme noted that the training provided was their main compensation, also describing the different ways social circus participants can generate income, including a mask-making business, a coffee shop with baked goods, and a shop to build monocycles. Explaining that the Municipality supported such endeavours by providing physical space, promotion and some expertise, she noted:

Because these are business ventures, they require some level of commitment and additional effort. Throughout this process they learn to share their skills with others … those who are studying different careers can actually use those skills at these new business ventures. For example, one of them is studying business development and management, the group has an expectation that this person will become the future manager of the business venture . … We are planning a big event soon and … masks were going to be very important. So, everyone made a commitment to creating two masks each to sell. So this is what we consider a “Colectivo”.

Once the local government put money into the project, they had the feeling of ownership of the project and the kids. It was like they could ‘rent’ them and make them perform during the different events the city organized.

promoting and developing social circus in Ecuador … both in the country and the region as in the rest of the world, aiming to improve society and lead to the construction of a just and creative world through horizontal work with individuals and the community.

Community arts as a microcosm of the Buen Vivir paradox: implications for thinking about the socio-politics of community art and wellbeing

The attempt to actualise the concept of Buen Vivir via social circus suggests multiple avenues for rethinking the relationship between individual and collective wellbeing and the role of cultural and artistic practice therein.

Our study highlighted the ways in which personal transformation, social inclusion and collective practice are intrinsically linked and mutually affect one another. Consistent with Bourdieu's theories on the relationships among economic capital, cultural capital and social capital (Bourdieu, Citation1997 [Citation1986]; Spiegel & Parent, Citation2017), the study not only reinforced research noting that those from lower social classes had lower starting scores for personal growth and social inclusion indicators (Richman, Clark, & Brown, Citation1985; Twenge & Campbell, Citation2002), but that the net benefit was greater where programmes put in place policies to reach out to youth in precarious conditions. It thus supports the call by health promotion scholars for such programmes to provide widespread coverage but pay special attention to those most vulnerable (Frohlich & Potvin, Citation2008), while also underlining the benefits of encouraging interaction between youth who might not otherwise come in contact with one another, offering exposure to different styles of living and breaking down class and cultural prejudice.

The ongoing challenges in realising the visions of the programme – and in particular, in blending a desire for inclusive collectively-oriented processes with high-performance products as techniques for supporting collective wellbeing – point to a broader tension. Scholars have argued that the declared social aims of Buen Vivir programmes were constrained by economic compromising and short-term political considerations, characterising the actions of Ecuador's government as pragmatic (Caria & Dominguez, Citation2016), aiming to redistribute resources without antagonizing Ecuadorian exporters, or as Becker put it, embracing ‘the humaneness of socialism while pursuing the efficiency of capitalism’ (Becker, Citation2014, p. 132). Instructors being drawn away from social pedagogy to prepare performances can be linked to the pragmatic need to ‘show’ benefit in technical terms. This tension dogged all the programmes, albeit to different extents and at different time periods; the ambitious plans for technical achievement under expensive big circus tents that never did materialise, became a distraction from the main purpose of the social circus programme. Indeed, the contradiction revealed here may be inherent in the social policy of capital-driven societies more broadly, and is linked to the very ‘need’ to approach sociocultural interventions as forms of building ‘capital’ for essentially economically-oriented development models.

The pressure and pull away from collective wellbeing toward utilising a collective process for productive ends, advancement of select individuals, and, as such, national cultural and economic ‘success’ as oriented by market values, is far from unique to Ecuador. It is a trend that has been seen worldwide, in social circus programmes as well as in the repurposing of public programmes more broadly. Indeed, in Quebec, home of Cirque du Soleil, official partner of Ecuador's social circus programme, the first venue created for social circus has long since been repurposed as a recreational and professional training centre (Spiegel, Citation2016a). In Ecuador, however, ongoing commitment to the collective wellbeing goals of the programme particularly by instructors, volunteers and participants themselves, suggests an avenue for rethinking the connection between the promotion of cultural agency and collective wellbeing as a factor not only increasing short-term indicators of health (fitness, nutritious diet, personal growth, etc.), but in acting as a force towards establishing future policy and institutions committed to the principles of inclusivity and social support. As Escobar noted: ‘The most interesting cases [of social transformation] might arise at moments when the State/social movement nexus is capable of releasing the potential for imagination and action of autonomous social movements’ (Escobar, Citation2010). In generating a movement to conjoin artistic processes to the transformation of conditions associated with the social determination of health, our study suggests that such creative programmes can contribute significantly to the development of a global culture of collective wellbeing. As such a culture grows, research must embrace epistemologies able to go beyond the development of positivist markers of individual improvement to also value holistic changes in social dynamics and cultures of transformations themselves.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank all the participants, volunteers, current and former staff of the programmes as well as the Ecuadorian government, municipal directors and Cirque du Soleil personnel who generously gave their time. We thank the individuals and participating organisations for giving us permission to use the photos. We are also grateful to our inspiring research collaborators especially Lynn Fels and Judith Marcuse at Simon Fraser University and Patrick Leroux at Concordia University, as well as Karen Lockhart, Steven Barker and the other skilful staff at the University of British Columbia and Universidad Andina Simon Bolivar.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. As this goes to press, a book written about this project, entitled ‘The Art of Collectivity: Social Circus and the Cultural Politics of a Post-Neoliberal Vision’, edited by Jennifer Beth Spiegel and Benjamin Ortiz Choukroun, is currently under review. We reference chapters from this book, as it is expected to be available in 2019.

2. For cohort definition in each city and programme, data gathering techniques, response rates, measures to mitigate ‘survivor bias’ as well as the specific statistical tests and statistical programmes employed in each set of analyses, see Yassi and Campaña (Citationin press).

3. In a 2015 Cirque du Monde's survey with responses from over 200 social circus organisations, social circus programmes in Ecuador reported that 91% of their funding was from government, compared to only 31% worldwide, where there is much greater dependence on foundations or the private sector – see Spiegel (Citationin press-b), and www.cirquedusoleil.com/en/about/global-citizenship/social-circus/cirque-du-monde.aspx.

4. Circo Social participants with low baselines saw a 54.8% greater improvement in personal growth (p < 0.0001), 17.5% greater improvement in social inclusion [p < 0.0001], and 35.4% greater improvement in social activism (p < 0.0001) compared to those with higher baselines. Other statistical analyses indicated that this was not simply a ceiling effect – see Yassi and Campaña (Citationin press).

5. The 78 volunteers who responded to the survey had an overall 21.6% change in personal growth compared to 15.8% in the 176 non-volunteering participants; p = 0.03.

References

- Acosta, A. (2011). Extractivism and neoextractism: Two sides of the same curse. In M. Lang & D. Mokrani (Eds.), ‘Mas alla del desarrollo’ (pp. 61–85). Quito: Abya Yala Ediciones.

- Alberto, A. (2016). Aporte al debate. El extractivsmo como categoría de saqueo y devastación. FIAR, 9(2), 24–33.

- Alonso González, P., & Vázquez, A. M. (2015). An ontological turn in the debate on Buen Vivir-Sumak Kawsay in Ecuador: Ideology, knowledge, and the common. Latin American and Caribbean Ethnic Studies, 1–20. doi:10.1080/17442222.2015.1056070

- Archambault, K. (2014). Évaluation d’un programme novateur de réadaptation par les arts de la scène pour des jeunes présentant un trouble psychiatrique stabilisé: Le programme Espace de Transition. London: Université de Montréal.

- Becker, M. (2011). Correa, indigenous movements, and the writing of a new constitution in Ecuador. Latin American Perspectives, 38(1), 47–62. doi:10.1177/0094582×10384209

- Becker, M. (2014). Rafael Correa and social movements in Ecuador. In S. Ellner (Ed.), Latin America’s radical left: Challenges and complexities of political power (pp. 127–148). Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Bhabha, H. K. (2012). The location of culture. London: Routledge.

- Bourdieu, P. (1997 [1986]). The forms of capital. In A. Halsey, H. Lauder, P. Brown & A. Stuart Wells (Eds.), Education: Culture, economy, society (pp. 46–58). Oxford: OUP.

- Boydell, K., Spiegel, J. B., & Yassi, A. (in press). Collectivity and the art of transdisciplinary community-based research: A rhizomatic approach. In J. B. Spiegel & B. Ortiz Choukroun (Eds.), The art of collectivity – Social circus and the cultural politics of a post-neoliberal vision. Montreal: McGill – Queen’s University Press.

- Breilh, J. (2008). Latin American critical (‘social’) epidemiology: New settings for an old dream. International Journal of Epidemiology, 37, 745–750. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn135

- Breilh, J. (2010). La epidemiología crítica: una nueva forma de mirar la salud en el espacio urbano. Quito, Ecuador.

- Breilh, J. (2013). La determinación social de la salud como herramienta de transformación hacia una nueva salud pública (salud colectiva). Revista de la Facultad Nacional de Salud Pública, 31(suppl 1), S13–S27.

- Breilh, J. (2017). Extractivismo petrolero, crisis múltiple de la vida y los desafíos de la investigación. Quito: UASB.

- Breilh, J., Campaña, A., Felicita, O., & al., e. (2009). Environmental and health impacts of floriculture in Ecuador. Quito, Ecuador. Retrieved from Research Report Project IDRC-CRDI (103697-001)

- Cadwell, S., & Rooney, B. (2013). Galway community circus – Community impact survey. Retrieved from http://www.academia.edu/10219178/Galway_Community_Circus_Impact_Study

- Caria, S., & Dominguez, R. (2016). Ecuador’ Buen Vivir: A new ideology for development. Latin American Perspectives, 43(1), 18–33. doi: 10.1177/0094582X15611126

- Carriel Mancilla, J. (2012). Public expenditure in health in Ecuador [Gasto público en salud en el Ecuador]. Rev Med FCM-UCSG, 18(1), 53–60. Retrieved from http://editorial.ucsg.edu.ec/ojs-medicina/index.php/ucsg-medicina/article/view/603/547

- Cecchi, L. E. (2015). New models of cultural policy in Latin America: A comparative analysis (2000–2014). VIII Congreso Latinoamericano de Ciencia – Política, organizado por la Asociación Latinoamericana de Ciencia Política (ALACIP). Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Lima.

- Cirque du Monde, Cirque du Soleil. (2014). ParticiPant handbook cirque du Monde training – Part 1. Retrieved from www.educircation.eu/documentation/

- Cirque du Soleil home page. Social circus – Cirque du Monde. Retrieved from http://www.cirquedusoleil.com/en/about/global-citizenship/social-circus/cirque-du-monde.aspx

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia (trans. Brian Massumi). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Escobar, A. (2010). Latin America at a crossroads. Cultural Studies, 24, 1–65. doi: 10.1080/09502380903424208

- Fels, L., & Ortiz Choukroun, B. (in press). Pedagogy of Circo Social Ecuador: Launching the ball. In J. B. Spiegel & B. Ortiz Choukroun (Eds.), The art of collectivity – Social circus and the cultural politics of a post-neoliberal vision. Montreal: McGill Queen’s University Press.

- Fornssler, B., McKenzie, H. A., Dell, C. A., Laliberte, L., & Hopkins, C. (2014). “I got to know them in a new way” Rela (y/t) ing rhizomes and community-based knowledge (brokers’) transformation of western and indigenous knowledge. Cultural Studies? Critical Methodologies, 14(2), 179–193. doi: 10.1177/1532708613516428

- Fox, N. J., & Alldred, P. (2015). New materialist social inquiry: Designs, methods and the research-assemblage. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 18(4), 399–414. doi: 10.1080/13645579.2014.921458

- Fricker, K. (2016). “Somewhere between science and legend”: Images of indigeneity in Robert Lepage and Cirque du Soleil’s Totem. In L. P. Leroux & C. Batson (Eds.), Cirque global – Quebec’s expanding circus boundaries (pp. 140–160). Montreal: McGill – Queen’s University Press.

- Frohlich, K., & Potvin L. (2008). Transcending the known in public health practice. American Journal of Public Health, 98(2), 216–221. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114777

- Gago, V. (2017). Neoliberalism from below: Popular pragmatics and baroque economies. Durham, NC: DUKE University Press.

- Government of Ecuador. (2008). Republic of Ecuador – Constitution of 2008. Retrieved from http://pdba.georgetown.edu/Constitutions/Ecuador/english08.html

- Gudynas, E. (2009). Diez Tesis Urgentes sobre el Nuevo Extractivismo: Contextos y Demandas Bajo el Progresismo Sudamericano Actual. In J. Schuldt, A. Acosta, A. Barandiará, A. Bebbington, M. Folchi, A. Alayza & E. Gudynas (Eds.), Extractivismo, Política y Sociedad (pp. 187–225). Quito: caap/claes.

- Hampshire, K. R., & Matthijsse, M. (2010). Can arts projects improve young people’s wellbeing? A social capital approach. Social Science and Medicine, 71, 708–716. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.015

- Hurley, E., & Léger, I. (2008). Les corps multiples du Cirque du Soleil, translated by Léger. Globe: revue internationale d’études québécoises, 11(2), 135–157. doi: 10.7202/1000525ar

- Hurtubise, R., Roy, S., & Bellot, C. (2003). Youth homelessness: The street and work: From exclusion to integration. In L. Roulleau-Berger (Ed.), Youth and work in the post-industrial city of North America and Europe (pp. 395–407). Boston: Brill Leiden.

- Huxley, P., Evans, S., Madge, S., Webber, M., Burchardt, T., McDaid, D., & Knapp, M. (2012). Development of a social inclusion index to capture subjective and objective life domains (phase II): Psychometric development study. Health Technology Assessment, 16(1), 1–248. doi: 10.3310/hta16010

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos (INEC). (2011). Ultimos resultados de pobreza, desigualdad y mercado laboral en el Ecuador. Quito, Ecuador.

- Kelaher, M., & Dunt, D. (2009). Evaluation of the community arts development scheme. Retrieved from https://www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/~/media/…/arts/cads/cads_final_for_web.pdf?la=en

- Kinnunen, R., Lidman, J., Kakko, S., & Kekäläinen, K. (2013). “They’re smiling from ear to ear” wellbeing effects from social circus. Retrieved from http://www.uta.fi/cmt/index/wellbeing-effects-from-social-circus.pdf

- Krieger, N. (2011). Epidemiology and the people’s health: Theory and context. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Leroux, L. P. (2012). Cirque in Space! The ethos, ethics, and aesthetics of staging and branding the individual of exception. Guest talk at the Centre for Canadian Studies, Duke University, Durham North Carolina.

- Leslie, D., & Rantisi, N. (2016). Creativity and place in the evolution of a cultural industry: The case of Cirque du Soleil. In L. P. Leroux & C. Batson (Eds.), Cirque global Quebec’s expanding circus boundaries (pp. 223–239. Montreal: McGill Queen’s University Press.

- Loiselle, F. (2015). Retombées du cirque social (Cirque du Soleil) en contexte de réadaptation sur la participation sociale de jeunes adultes avec déficiences physiques en transition vers la vie active – Étude qualitative. London: University of Montreal.

- Macas, L. (2010). Sumak Kawsay. La vida en plenitud. América Latina en Movimiento, 452, 14–16. Retrieved from http://icci.nativeweb.org/yachaikuna/Yachaykuna13.pdf

- Marcuse, J., Fels, L., Boydell, K., & Spiegel, J. B. (in press). Through their own bodies, eyes and voices: Social circus, social inquiry and the politics of facilitating “collectivity”. In J. B. Spiegel & B. Ortiz Choukroun (Eds.), The art of collectivity – Social circus and the cultural politics of a post-neoliberal vision. Montreal: McGill – Queen’s University Press.

- Mauthner, N., & Doucet, A. (2003). Reflexive accounts and accounts of reflexivity in qualitative data analysis. Sociology, 37(3), 413–431. doi: 10.1177/00380385030373002

- McCaffery, N. (2011). Streetwise Community Circus, Knockavoe School evaluation An evaluation of the impact of teaching circus skills to people with learning disabilities. Retrieved from www.sccni.co.uk/assets/knockavoe-final-evaluation2.pdf

- McCauley, J. (2011). The circus she calls me: Youth at risk in a social circus. (International Development MSc.), University of Amsterdam.

- Mezzadra, S., & Gago, V. (2017). In the wake of the plebeian revolt: Social movements, ‘progressive’ governments, and the politics of autonomy in Latin America. Anthropological Theory, 17(4), 474–496. doi: 10.1177/1463499617735257

- MIF. (2013). The MIF, Cirque du Soleil and three Latin American social circus schools join forces to promote youth employability, press release. Retrieved from http://www.fomin.org/en-us/Home/News/PressReleases/ArtMID/3819/ArticleID/995.aspx

- Programa Circo Social Ecuador. (2012). Mision y objectivos. Quito. Retrieved from http://www.vicepresidencia.gob.ec/programas/sonrieecuador/circo-social-yartistico

- Rice, P. L., & Ezzy, D. (1999). Qualitative research methods: A health focus. Melbourne, Australia.

- Richman, C., Clark, M., & Brown, K. (1985). General and specific self-esteem in late adolescent students: Race× gender× SES effects. Adolescence, 20(79), 555–566.

- Robitschek, C. (1998). Personal growth initiative: The construct and its measure. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 30, 183–198.

- Rockwell, S. K., & Kohn, H. (1989). Post-then-pre evaluation: Measuring behavior change more accurately. Journal of Extension, 27(2). Retrieved from http://www.joe.org/joe/1989summer/a1985.html

- Savolainen, A., & Suoniemi, S. (2015). Hoitsusirkus Namibiassa-sosiaalisen sirkuksen voimauttava ja ryhmäyttävä vaikutus namibialaisten lasten keskuudessa. Retrieved from https://www.theseus.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/98828/savolainen_aleksei.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Secretaria Nacional de Planificación y Desarrollo. (2009). Plan nacional para el buen vivir 2009–2013: Construyendo un estado plurinacional e intercultural. Quito: Government of Ecuador.

- Secretaria Nacional de Planificación y Desarrollo. (2013). Plan nacional para el buen vivir 2013–2017. Quito.

- Spiegel, J. B. (2014). Social circus as an art for social change: Promoting social inclusion, social engagement and cultural democracy. In K. Kekäläinen (Ed.), Studying social circus: Openings & perspectives (pp. 70–75). Tampere: University of Tampere.

- Spiegel, J. B. (2015). The value of social circus: creative process, embodied critique, and the limits of ‘capital’. Canadian Association for Theatre Research, Montreal.

- Spiegel, J. B. (2016a). Singular bodies, collective dreams: Socially engaged circus, arts and the “Quebec spring”. In L. P. Leroux & C. Batson (Eds.), Cirque global – Quebec’s expanding circus boundaries (pp. 266–283. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Spiegel, J. B. (2016b). Social circus: The cultural politics of embodying “social transformation”. TDR: The Drama Review, 60(4), 50–67. Retrieved from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1162/DRAM_a_00595

- Spiegel, J. B. (in press-a). Creativity and the condition of precarity: Embodied social transformation in a changing socio-political landscape. In J. B. Spiegel & B. Ortiz Choukroun (Eds.), The art of collectivity – Social circus and the cultural politics of a post-neoliberal vision. Montreal: McGill Queen’s University Press.

- Spiegel, J. B. (in press-b). Social circus, Buen Vivir: A critical inquiry into one bold political vision. In J. B. Spiegel & B. Ortiz Choukroun (Eds.), The art of collectivity – Social circus and the cultural politics of a post-neoliberal vision (pp. 3–44). Montreal: McGill Queen’s University Press.

- Spiegel, J. B., Breilh, M., Campana, A., Marcuse, J., & Yassi, A. (2015). Social circus and health equity: Results of a feasibility study to explore the national social circus program in Ecuador. Arts & Health: An International Journal for Research, Policy and Practice, 7(1), 65–74. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2014.932292

- Spiegel, J. B., Ortiz Choukroun, B., Campaña, A., & Yassi, A. (in press). Cultural policy and the Buen Vivir debate: Politics of transition and the development of Circo Social Ecuador. In J. B. Spiegel & B. Ortiz Choukroun (Eds.), The art of collectivity – Social circus and the cultural politics of a post-neoliberal vision. Montreal: McGill Queen’s University Press.

- Spiegel, J. B., & Parent, S. (2017). Re-approaching community development through the arts: A ‘critical mixed methods’ study of social circus in Quebec. Community Development Journal, 42(3), 1–18. doi: 10.1093/cdj/bsx015

- Trotman, R. (2012). Building character and community. Community circus: A literature review. Retrieved from http://www.simplycircus.com/node/631

- Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2002). Self-esteem and socioeconomic status: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6(1), 59–71. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0601_3

- Ugolotti, N., & Moyer, E. (2016). ‘If I climb a wall of ten meters’: Capoeira, parkour and the politics of public space among (post) migrant youth in Turin, Italy. Patterns of Prejudice, 50(2), 188–206. doi: 10.1080/0031322X.2016.1164435

- UNICEF, Ecuador. (2002). Observatory for the rights of children and adolescents. Retrieved from http://www.unicef.org/ecuador/english/children_2991.htm

- Walsh, C. (2009). Interculturalidad, estado, sociedad: luchas (de) coloniales de nuestra época. Quito: : Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar.

- Walsh, C. (2010). Development as Buen Vivir: Institutional arrangements and (de)colonial entanglement. Development, 53(1), 15–21. doi: 10.1057/dev.2009.93

- Weisbrot, M., Johnston, J., & Merling, L. (2017). Decade of reform: Ecuador’s macroeconomic policies, institutional changes, and results. Retrieved from http://cepr.net/publications/reports/decade-of-reform-ecuador-s-macroeconomic-policies-institutional-changes-and-results

- Yassi, A., & Campaña, A. (in press). The impact of Circo Social Ecuador and other community arts on health: A longitudinal comparative quantitative analysis. In J. B. Spiegel & B. Ortiz Choukroun (Eds.), The art of collectivity – Social circus and the cultural politics of a post-neoliberal vision. Montreal: McGill – Queen’s University Press.

- Yates, J., & Bakker, K. (2013). Debating the ‘post-neoliberal turn’ in Latin America. Progress in Human Geography, 30, 0309132513500372. doi: 10.1177/0309132513500372