ABSTRACT

Drawing on ethnographic research conducted from 2011 to 2015 and the authors’ long-term engagement in diverse aspects of HIV and human rights advocacy in Brazil, this paper explores key elements of the Brazilian sex workers’ movement response to HIV and the broader political factors that profoundly influenced its trajectory. We argue that the movement has constantly challenged representations of prostitution by affirming sex workers’ roles as political actors, not just peer educators, in fighting the HIV epidemic and highlight their development of a sex positive and pleasure centred response that fought stigma on multiple fronts. Moments of tension such as the censorship of an HIV prevention campaign and implementation of ‘test and treat’ projects are analysed, as are the complex questions that Brazil’s 2016 political and economic crisis evokes in terms of how to develop and sustain responses to HIV driven by communities but with material commitment from the State. We conclude with what we see to be the unique, central components of Brazilian sex workers’ approach to HIV prevention and what lessons can be learned from it for broader collective health movements in Latin America and beyond.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

In 2016, the founding principles that made Brazil’s widely recognised response to HIV a success (Berkman, Garcia, Munoz-Laboy, Paiva, & Parker, Citation2005) came under direct threat. For the first time since the installation of Brazil’s democratic constitution in 1988, the country had a Minister of Health, Ricardo Barros, who publicly positioned himself against the Universal Health Care System (SUS – acronym in Portuguese) and in favour of expanding private health care plans (Colucci, Citation2016). Michel Temer, Brazil’s president after the impeachment of the country’s first female president, Dilma Rousseff, acted quickly after taking power to pass a Constitutional Amendment that froze the already underfunded health and education budgets for 20 years. Denounced by UN officials as an ‘affront to human rights’ (Melo, Citation2016), many see the amendment as paving the way for the end of the SUS (Dias, Citation2016).

The dismantling of Brazil’s public health system raises critical questions about sustaining a rights-based approach to health in times of political crisis. The SUS is an outcome of extensive civil society mobilizations after two decades of dictatorship (Paiva & Teixeira, Citation2014). It was formalised in Brazil’s 1988 democratic constitution and has been a cornerstone of the AIDS response for a series of interrelated reasons, perhaps most importantly because mobilisation in response to the HIV epidemic in Brazil occurred in parallel to the influential public health reform movement to establish the SUS (Daniel & Parker, Citation1991; Parker, Citation2003). The National AIDS Programme (NAP) invited representatives from social movements active in fights against the dictatorship to be involved in designing the country’s first HIV prevention actions for their peers soon after was founded, bringing together public health reform movements and social movements for sexual rights.

The sex worker movement was one of these movements. Founded amidst Brazil’s redemocratization process in 1987, the movement has its roots in resistances to the military dictatorship and mobilizations against police violence. What contemporary literature refers to as ‘structural determinants of HIV’ (Gupta, Parkhurst, Ogden, Aggleton, & Mahal, Citation2008) have been the foundation of the movement’s politics (and Brazil’s response to HIV) since the beginning along with a strong defense of prostitution as work and a sexual right (Leite, Murray, & Lenz, Citation2015). As Lourdes Barreto, a sex worker from the state of Pará who co-founded the Brazilian Prostitute NetworkFootnote1 stated in a 2012 interview, ‘In prostitution, I learned to see how society has a lot of problems, and that I wasn’t one of them’(Bogea, Citation2012). Lourdes’ affirmation of not being one of the problems is emblematic of the movement’s position that the heightened vulnerability of sex workers to HIV is more of an outcome of stigma, gender inequalities and the continued criminalisation of prostitution than their profession itselfFootnote2.

Sex worker movements around the world have taken a similar stance on rights-based approaches to HIV (Chateauvert, Citation2013; Mgbako, Citation2016). Researchers have focussed more specifically on structural and social determinants of sex workers’ vulnerability to HIV publishing a series of studies conducted in the late 1990s and mid-2000s that emphasise the importance of policy and social contexts and community mobilisation responses (Basu et al., Citation2004; Kerrigan et al., Citation2006; Lippman et al., Citation2012). A growing body of literature has emphasised the role of criminalisation of sex work in increasing sex workers’ vulnerability to HIV and violence (Decker et al., Citation2015; Shannon et al., Citation2015), with The Lancet 2014 special series on HIV and sex work explicitly calling for decriminalisation as the most effective way to fight the HIV epidemic among sex workers (Beyer et al., Citation2015).

These are important advances. There remains, however, little research examining the political dimensions of HIV intervention programmes in sex work contexts beyond legal and policy frameworks. Here, we suggest that the Brazilian sex worker movement’s response to HIV is unique for the ways in which it has maintained sex and pleasure at the centre of its response. The decision by the national network to use the word prostituta (prostitute) in its name, while other international movements have shifted towards ‘sex work,’ is an example of how activists have chosen to reclaim, rather than alter, terminologies and aspects of the profession associated with transgression or immorality. More confrontational than conforming, this strategy is characteristic of many of the Brazilian Prostitute Networks’ actions and illustrative of Jaques Ranciere’s definition of politics as a mode of subjectification that provokes reconfigurations of broader systems of domination and inequality (Rancière, Citation1999).

In this article, we take a closer look at the political dimensions of the sex worker movement in Brazil’s response to HIV. We focus primarily on their relationship with the Ministry of Health, contextualising it within the broader context through which both the movement, and its response to AIDS, grew. We suggest that the changes in taking place at the level of federal government in 2016 are a culmination of a series of setbacks in Brazil over the past decade, and reflective as well of broader neoliberal tendencies and the (re)medicalisation of the HIV response (Nguyen, Bajos, Dubois-Arber, O'Malley, & Pirkle, Citation2011). We highlight what we see to be the unique, central components of Brazilian sex workers’ approach to HIV prevention that make it effective for activism and HIV prevention, and what lessons can be learned from it for broader collective health movements in Latin America and beyond.

Methodology

The research presented in this article is based on the extended case method approach to data collection and analysis (Burawoy, Citation1998), drawing on the authors’ unique and long-term engagement in HIV prevention and sex worker rights in Brazil. The first author has worked in Brazil since 2004 in a series of HIV prevention, advocacy, film and research projects with sex workers, collaborating frequently with the Brazilian Prostitute Network. In 2012, she began an ethnographic study as part of a dissertation on prostitute activism in Brazil that extended through 2014 and included archival research and ethnographic fieldwork with three sex worker organisations (Murray, Citation2015). The second author has worked on issues related to HIV and sex work since 1996, first in the Dominican Republic and then in Brazil, later coordinating international projects surrounding community empowerment as a cornerstone of HIV prevention among sex workers sponsored by WHO, UNFPA and The World Bank. The third author has focussed her research on sexuality and a human rights based approach to health. She has served on a series of Brazilian and WHO/UNAIDS commissions on HIV/AIDS since 1992, and in 2014 was elected to compose Brazil’s National Human Rights Commission (CNDH – acronym in Portuguese), that oversees human rights violations in the country.

Drawing on these experiences allows us to comment on the intersections between the prostitute movements’ activism, HIV policy shifts nationally and internationally, and the political and economic crises that have shaken Brazil. In this way, our analysis is inspired by Lorway and Khan’s ethnography of a large HIV prevention intervention in India (Citation2014). They argue that observing the project across diverse contexts and spaces permitted the ‘opportunity to learn about the complex workings of [its] multiple components’ (Lorway & Khan, Citation2014). We suggest that our viewpoints and engagement with sex work and HIV/AIDS policies in distinct local, national and international contexts allows us to identify both the unique contributions of the prostitute movement and the broader political factors that profoundly influenced their trajectory over the past decade.

The empirical data cited in this article derives from the archival research, participant observation and 65 in-depth interviews with sex workers, activists and government and non-governmental officials that the first author conducted as part of her ethnographic research on sex worker activism in Brazil (Murray, Citation2015). As part of this research process, interviews and field notes were coded, and data was organised into analytical memos to identify themes and systemic patterns (Emerson, Fretz, & Shaw, Citation1995). Analytic field notes were transformed into the conceptual frameworks, and the analysis presented in this paper derives from the theoretical frameworks developed to understand the movement's engagement and activism surrounding HIV/AIDS . This research was approved by the Columbia University Medical Centre Institutional Review Board, along with the Institute of Social Medicine at the State University of Rio de Janeiro (IMS/UERJ) and Brazil’s National Ethics Review Board (CONEP).

Beginnings

Brazil’s first national HIV prevention programme with sex workers, prisoners and drug users was called PREVINA. Dr. Lair Guerra, the first director of the National AIDS Programme, invited prostitute activist and co-founder of the recently formed Brazilian Prostitute Network (RBP – acronym in Portuguese), Gabriela Leite, to Brasilia in the late 1980s to discuss the project. Despite a climate of broad civil society mobilisation and the emerging female sex worker movement, the original project design of PREVINA presented a morally charged vision of prostitution and activities that were more individual than community driven. The general objective was to,

Implant a Program of Control and STD/AIDS Prevention in prostitution [contexts] seeking to raise the consciousness of those who work in it (men as well as women), or that have some sort of relationship with it and risk of contamination and transmission of disease through sexual acts (MOH, Citationn.d.).

Roberto Domingues, a technical advisor to the Brazilian Prostitute Network who formed part of the PREVINA project team, shed light on the early discussions with the Ministry of Health regarding the prevention materials they had initially developed for the project:

We had a life and death fight with the Ministry of Health because we arrived at the conclusion, the group on prostitution, led by Gabriela, that the materials couldn’t have the biological focus that they were taking. We saw these questions of “[how] you get it [HIV], [how] you don’t get it” that weren’t resonant, and we stood firm … And we won, because it was the first large material produced that breaks with a biological approach. And we clearly see in these materials that they have a very large bias towards sex work as an identity.

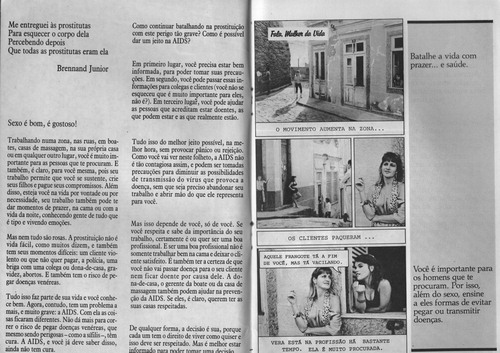

Figure 1. The first two pages of the brochure developed for the PREVINA project by the Prostitution and Civil Rights program at the Institute for Religious Studies (ISER) in Rio de Janeiro. The project was coordinated by Gabriela Leite and the material content written by Flavio Lenz Cesar. The material is called, ‘Speak, Woman of the Life,’ and begins with the phrase, ‘Sex is good, it’s delicious!’. © ISER, 1989. Image is a scanned copy of the original.

Roberto also emphasised that the fight from the very beginning was about much more than health. At the time, sexuality and citizenship were fundamental components of any response to an epidemic. This was reflected across the broader AIDS movement as a whole (Parker, Citation2003). As Roberto said, ‘the AIDS movement won me over as an activist when I perceived that it was part of a fight for democratization … it was a moment of reconstructing citizenship.’ The openness to listening in the National AIDS Programme was also largely due to their connections to the broader social movements for public health reform in Brazil (Galvão, Citation2000; Parker, Citation1987, Citation1994). As Roberto said, ‘It wasn’t only through resistance that we lived. We had a lot of allies who made things happen. Inside the Ministry of Health, but specifically, inside the STD/AIDS [program].’

The PREVINA project team released the Fala, Mulher da Vida materials along with similar materials made specifically for male and transgender sex workers at a national meeting focussed on ‘AIDS and Prostitution’ in 1989. The meeting opened with doctors and specialists talking, but sex workers, led by Gabriela Leite, soon rebelled. As she was quoted by the Brazilian Prostitute Network’s newspaper, Beijo da rua (A Kiss from the street) editor, Flavio Lenz, in an article about the event,

I felt that people were distant from everything and that the doctors were, of course, involved in a debate with themselves. So the next morning, I came back in a low cut black dress, high heels, exaggerated make-up and I talked about my life (1990, p. 4).

The sex-positive approach to prevention and the protagonist role of sex workers in developing and implementing HIV programmes were two of the defining features of the federally funded AIDS programmes during the 1990s. The Ministry of Health developed a manual to train peer educators maintaining the positive and inclusive tone towards prostitution that had characterised the Fala, Mulher da Vida materials. In the section on citizenship, they state:

What ruins a prostitute, what takes away her health and dignity, is not having sex professionally, but the lack of working conditions, the right to personal security, the right to justice, respect for private and family life, liberty of expression and opinion, the right to marry and form a family continuing our profession, etc. (1996, p. 25)

Government AIDS programmes and prostitute rights and AIDS advocacy organisations grew rapidly during the 1990s period with financial support from the World Bank and international foundations. The rapid expansion of NGOs was sanctioned by the government: from 1993 through 1997, the National AIDS Programme funded 564 projects with 181 AIDS NGOs nationally (Nunn, Citation2009, p. 176), 52 of which were for male, female or transgender sex workers, with the majority (44) for female sex workers (Rossi, Citation1998).

During the time period 1998–2003, a second World Bank loan funded even more projects with NGOs, with a total of 2,163 projects with 795 organisations (Nunn, Citation2009). Esquina da Noite (Night Corner), a national-level project implemented as part of the second World Bank loan centred on expanding the number of sex worker-led organisations working in HIV prevention in rural areas and interior cities, where the epidemic was also spreading, and spanned 50 municipalities throughout the country. The project was strategic as it was implemented at a time that the Ministry of Health (MOH) started to increasingly decentralise its actions, meaning that organisations would be funded through municipal and state sources rather than the federal government. Given the climate of decentralisation, Esquina da Noite focussed its attention on forming partnerships between sex worker organisations and state and municipal AIDS programmes; a feat that Beijo da rua identified at the time as one of the largest challenges to implementing the project’s activities.

The principles of solidarity, respect and citizenship that Brazil became so well known for in its HIV programmes made their way into a 2002 national prevention campaign centred around a character named Maria Sem Vergonha (Maria Without Shame). The campaign image has Maria over a row of flowers called sem vergonhas (referred to as shameless because they will grow anywhere), and was accompanied by a series of statements such as, ‘No shame in being a prostitute’ and ‘No shame in valuing your work.’ The campaign included radio spots and print materials distributed in prostitution contexts throughout Brazil.

The Maria Without Shame campaign had even more relevance given its timing. The government launched the campaign the same year that the Ministry of Labour recognised profissionais do sexo (literally, sex professionals) as an official profession within the Brazilian Classification System (CBO acronym in Portuguese) of formal occupations that qualify for federal government benefits such as retirement benefits and government assistance in case of illness. The Ministry of Labour was well aware of the Ministry of Health’s successful HIV campaigns in partnership with sex worker organisations at the time, and invited the Brazilian Prostitute Network to participate in the development of the professional category in the CBO’s database (ABIA & DAVIDA, Citation2013).

The movement’s influence is clear in the definition of the profession’s five main activities included on the Ministry of Labour’s CBO database: finding dates, minimising vulnerabilities (which includes both condom use and combating stigma), attending to clients, accompanying clients, and promoting worker organising (CBO, Citation2017). References in the definition to ‘minimizing vulnerabilities’ are also demonstrative of the ways in which STD and HIV prevention influenced the very meaning of sex work in Brazil. This is another example of the impact of HIV on sex worker organising and of how the movement integrated AIDS as one of its pillars, alongside fighting discrimination and stigma and promoting sexual education and labour organising.

Not everyone in Brazilian society was pleased with these advances, however. Conservative religious organisations (both Evangelical and Catholic) that gained political influence throughout the decade organised large mobilizations against the inclusion of sex work in the classification of occupations. In 2007, the Ministry of Labour called another meeting to ‘minimize the religious and societal pressures’ surrounding the controversy, making small, but symbolic changes such as removing the word puta (whore) which had been included as a synonym, and attributes of the profession that were considered to be too sexual (such as, ‘seducing clients with your eyes’) (ABIA & DAVIDA, Citation2013). Lourdes Barreto and Gabriela Leite defended the importance of using the word puta from early on in the movement, seeing its usage as the most effective way to challenge the gender inequalities and hypocrisies at the core of the stigma around prostitution (Leite, Citation2013). Thus its removal from the CBO, after their hard fought victory years earlier to include it, was particularly symbolic of the changing times.

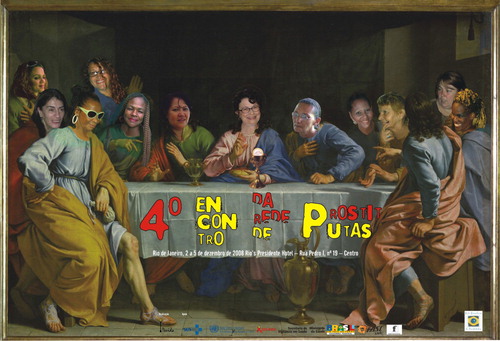

The 4th National Prostitute Network Meeting was held in Rio de Janeiro in December of 2008 in this tense climate. Rather than adjust their politics to the increasingly conservative and religious influences, the RBP confronted them. As can be seen in , the official artwork displayed on a gigantic banner depicted Gabriela Leite as Jesus, surrounding by other leaders from the RBP. The banner states, ‘Fourth Encounter of the Network of Prostitutes,’ yet the designer, the late Sylvio Oliveira, organised the letters of prostituta in a way that highlights the word puta. The combination of the playful, yet transgressive, use of the religious symbolism and prominence of the word puta on the banner are an excellent example of how the movement responded to attempts to diminish aspects of their profession and activism that they understood to be central to advancing both health and citizenship.

Figure 2. The artwork for the 2008 National Meeting of the Brazilian Prostitute Network in Rio de Janeiro. The banner says, ‘Fourth Encounter of the Network of Prostitutes,’ written in a way that also highlights the word ‘Puta’ (whore). It was created by the late Sylvio de Oliveira, artist and Davida member.

An ally from the Ministry of Labour and Employment attended the meeting. In his official powerpoint presentation, however, he took the opportunity to affirm that, ‘The CBO recognises the existence of an occupation, of a job, but does not regulate it. To recognise is different than to legitimize.’ The Ministry’s official stance distinguishing between recognition and legitimation is important and emblematic of how many state institutions had begun to adjust their discourses around prostitution. As the following section explores, the time period between 2005 and 2010 was bittersweet for many sex workers and AIDS activists, and one in which setbacks increasingly outweighed advancements.

Reconfigurations

In 2002, Luiz Ignacio Lula da Silva ‘Lula’ was elected president in Brazil and ushered in an era of hope among the populations that had supported the labour union leader since his days organising for democracy. Lula took office in 2003 and with his election, many activists from Brazil’s women’s, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT), racial equality and AIDS movements took government office in Ministries and the newly established secretariats such as the Special Secretariat for Women’s Policies (SPM) and Special Secretariat for Racial Equality. Lula’s government initially was active in addressing issues of income, racial, gender and sexuality inequalities and did so through tactics that included programmes and plans designed at the federal level, involving large consultations in regional and national conferences with community-based organisations, civil society and social movements.

His first term coincided with several events that had a profound symbolic effect on sex worker activism and HIV prevention. First, in 2005, as part of President Bush’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), the United States government introduced a contractual clause stipulating that all entities receiving US government funds have a statutory clause explicitly opposing prostitution. In partnership with the RBP, the Brazilian government refused to implement this mandate, eventually rejecting nearly US$40 million in HIV prevention funds that had been allocated to the country. Brazil’s decision was heralded by the international community (Okie, Citation2006) and applauded by sex worker activists globally. Second, UNAIDS held a Global Consultation on Sex Work in Rio de Janeiro in 2006 as part of its process to draw up global guidelines for member states to address HIV/AIDS and sex work (Csete, Citation2013). Subsequent meetings were held regionally, in Lima in 2007, and nationally in 2008 (MOH, Citation2008).

The National Consultation on STD/AIDS, Human Rights and Prostitution resulted in the definition of sixty recommendations, largely focussed on broadening the HIV response to structural factors and demanding inter-sectorial committees to move forward a rights-based agenda of HIV prevention with sex workers. The Ministry of Health and National Secretariat of Women’s Policies incorporated more than half of these recommendations into a revised version of a plan they developed in partnership with a variety of civil society groups to confront the increasing prevalence of HIV/AIDS among women in Brazil. The original plan (called ‘Integral Plan to Confront the Feminisation of the AIDS Epidemic and other STDs’) had been launched in 2008 and only mentioned prostitutes once. The Ministry of Health revised it, however, in 2009, including a series of agendas afirmativas, or affirmative agendas, for specific populations, including sex workers (where 34 recommendations from the national consultation were incorporated). The prostitute movement considered the affirmative agenda a victory when it was launched, however, it did not sair do papel (expression meaning ‘leave the paper,’ or turn into action) (ABIA & DAVIDA, Citation2013).

To some extent, the civil society – government partnerships during Lula’s government resulted in the conversion of sexual rights and AIDS activism into federal level secretariats, working groups, and plans that then relied on federal oversight mechanisms to enforce them at the state and municipal levels (Rich, Citation2013). This proved to be quite challenging, despite the work of what Jessica Rich refers to as activist bureaucrats, or ‘reform-minded bureaucrats’ that mobilised civil society groups to (attempt to) implement progressive federal policies and plans on a local level as the AIDS response was increasingly decentralised (Rich, Citation2013). Decentralisation also meant that NGOs had to abide by the extensive and complicated rules and regulations associated with receiving state and municipal level funding. Such requirements substantially increased the administrative burdens on NGOs and gave state administrators ample bureaucratic reasons to justify not funding them. According to Estela Scandola, an activist from the Feminist Health Network, state and municipal governments sought excuses not to fund the organisations perceived as trouble-makers. As she stated:

[A]n NGO that wants to be civil society and autonomous, it is going to be a watchdog, and monitor the councils it participates in. So for example, state governments hate us. For example there was a project request and we did one for sex workers and our project wasn’t approved because it was missing page 2, which is where we described our objectives, etc. In other times, they would have called us, [and said] “look you’re missing page 2.” An organization linked to the church won the money. This was in 2007, 2008.

As Estela points out, the issue was not just increased administrative burdens, but also related to increased influence of religious lobby groups. The Evangelical population expanded locally and regionally during Lula’s two terms, comprising 22.2% of the country’s population by 2010 (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística [IBGE], Citation2010), and forming a powerful Congressional lobby with 77 representatives. The expansion of religious fundamentalist movements within federal and state level governments led to recurrent waves of backlash in all matters related to gender and sexuality (Corrêa, Citation2016). Health and educational policies of the previous decades were challenged and extracted from local policy plans and speaking about sexuality and prevention in schools was eventually prohibited (Paiva & Silva, Citation2015).

Brazil’s economy and position in the global political landscape was also changing rapidly. In 2007, when Brazil was selected to be the host for the 2014 World Cup, and two years later for the 2016 Olympics, the country was still being held up as an emerging global economic power. The economy weathered the 2008 international crisis, yet as Brazil came to be seen as middle income, large funders pulled out of the country. Funders (erroneously) assumed that sexual rights and HIV/AIDS were under control and firmly installed as government priorities; their decision had significant effects on the movements dedicated to these causes. The first decade of 2000 thus ended with a large number of progressive plans and initiatives for HIV in place, yet many organisations were either on the brink of losing funding or lacked the local support from their municipal or state level governments to implement them.

The HIV response with sex workers arguably reached its peak in 2002 when both the social movement and the federal AIDS programme were strong. While the development of the diverse plans and programmes during Lula’s administration had a strong symbolic effect and reflected participatory processes, challenges posed by decentralisation and the increasing power of Evangelical fundamentalists made implementing them nearly impossible as fewer and fewer Ministries and secretariats were willing defend sex worker rights. Parallel to these processes, biomedical approaches to prevention, propelled by global pharmaceutical markets, gained steam on the global health landscape (Biehl, Citation2014; Nguyen et al., Citation2011) and were viewed as economically advantageous under the neoliberal logics governing public health systems (Parker & Aggleton, Citation2014). This provided the government with programmatic justification, and funding, for a shift in approaches. As the following section explores, sex worker activists sensed the government’s support waning and became frustrated, leading to ruptures with the Ministry of Health, and later, within the movement (Leite et al., Citation2015).

Ruptures

In 2011, the Brazilian Prostitute Network made a decision to no longer apply for federal funding for AIDS projects. The decision was made at the Network’s regional conference in Belém, in a statement that began with the phrase, ‘We are professionals of sex, not the government.’ The statement makes various references to the difficulties organisations encountered with state funding and reporting mechanisms and, while it recognises the importance of the partnership with the National AIDS Programme, expresses their dissatisfaction with the directions the Programme was going. In particular, a sense that the ‘risk group’ mentality they had fought so vehemently against in the late 80s had returned through projects that ‘reinforce prostitutes as spreaders of disease and distributors of condoms’ (Leite et al., Citation2015, p. 18).

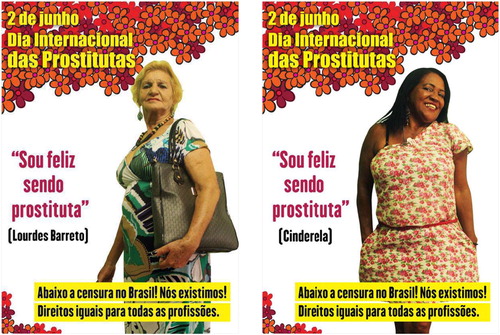

In 2013, the extent to which the MOH’s approach to HIV prevention had changed became even clearer when the MOH censored a campaign developed in a workshop with leaders from prostitute organisations throughout Brazil. The campaign, developed for International Sex Worker Rights Day on June 2nd, lasted less than 24 hours online. The most controversial of the posters, which featured a sex worker with the sentence ‘I’m happy being a prostitute,’ provoked immediate and angry reactions from conservatives in Brazil’s Congress. The Director of the STD and HIV/AIDS Department was fired and the entire campaign was taken offline just two days after its release. An altered campaign was put up in its place and only the posters with phrases about condom use were retained. shows one of the original campaign posters alongside an altered version.

Figure 3. Ministry of Health original (left) and altered campaign (right), both downloaded from the www.aids.gov.br website. The top left of the original image states, ‘June 2nd, International Prostitute's Day.' In the altered image, this is replaced with ‘A prostitute who takes care of herself always uses a condom' and a text on the bottom left stating, ‘Life is better without aids. Get your condom at the health center. AIDS still doesn't have a cure.' Pictured is Cida Vieira, president of the Minas Gerais Prostitutes' Association (APROSMIG). ©Governo do Brasil. No changes were made to the images.

Although the Minister of Health at the time, Alexandre Padilha, expressed concern about the content (Rovai, Citation2013), the official reason for taking down the campaign centred upon a technicality: the campaign had not passed through the appropriate bureaucratic channels for approval. The mass mobilisation protesting the decision to dismantle the campaign disagreed. It was the third time in a year and a half that materials referring to HIV prevention and sexuality had been censored (these included a kit against homophobia designed for schools in 2011 and a Carnival campaign targeting gay youth in 2012). Sex worker organisations responded with strong statements and public actions (). The RBP’s statement makes a direct connection to violations of the SUS principles, drawing attention to what they saw to be political negotiations and agreements:

What arrangements are behind these movements? Is there a project for happiness? Why can only they [politicians] be happy? What is the price to be paid by prostitutes? Our bodies, desires and lives are what are paying the prices of political agreements and party negotiations. This is the cost of the censorship and cutting off dialogue (Brazilian Prostitute Network, Citation2013).

Figure 4. GEMPAC protest campaign. Both posters state (from top to bottom) June 2nd, International Prostitute's Day. ‘I'm happy being a prostitute.' And in yellow: ‘Down with censorship in Brazil! We exist! Equal rights for all professions.' Pictured are Lourdes Barreto and Cinderela. Downloaded from social media campaign. ©GEMPAC. No alterations were made to the images.

The motive of the reactivation of the partnership was a project called Live Better Knowing [your HIV status], a ‘test and treat’ project directed at sex workers, MSM, and people who use drugs. The project caused divisions within the Network because several organisations saw it as contrary to the clause of the RBP’s Letter of Principles, which repudiates the ‘offering of exams and other medical procedures in locations where prostitution is practiced, except in cases that involve the general population.’ Indeed, HIV testing projects have had a long and contentious history with the Brazilian Prostitute Network. The clause against testing was closely connected to their resistance to HIV testing in work locations as they saw such initiatives as further stigmatising prostitution areas. The Live Better Knowing project was distinct from previous projects, however, as rather than researchers or health care staff, testing and counselling was to be conducted by sex workers themselves.

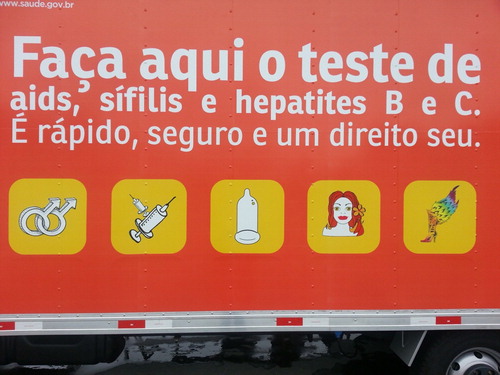

Such ‘test and treat’ actions are part of what Patton (Citation2011) refers to as the Treatment as Prevention (TasP) regime, in which the right to dignity and quality of life has been truncated ‘into a conveyed right to treatment read through the lens of uncontested and falsely promised scientific solutions,’ that, according to Patton, actually violates, rather than protects, rights (263). Patton’s observation regarding the use of rights language in TasP can be seen in the artwork on the rapid HIV testing van that was parked outside the World AIDS Day event in Rio de Janeiro in 2013 (). The text reads, ‘Get tested here for AIDS, Syphilis and Hepatitis B and C. It’s quick and your right.’ Underneath are cartoonish drawings of two male symbols together, a syringe, a condom, Maria Without Shame (the symbol of sex worker campaigns) and a boot with butterfly wings, the symbol of the government’s campaign for travestis. The images of these past rights-based campaigns are resignified as endorsements of the rapid test campaign. Placed against condoms and syringes, populations are turned into prevention methodologies. Rights are reduced to the right to choose a prevention method.

Figure 5. Ministry of Health rapid HIV testing truck, parked at the December 1st World AIDS Day activities in Rio de Janeiro, 2013. Photo by Laura Murray.

As the Ministry of Health’s actions moved further away from a human rights agenda (Basthi, Parker, & Terto Júnior, Citation2016), organisations increasingly turned towards cultural actions to sustain their activism and advocate for sex worker rights from a place of irony and pleasure, rather than as victims or vectors of disease. For example, Davida, a Rio de Janeiro based sex worker rights organisation, founded the clothing line Daspu (as in das putas – of the whores) in 2005 and their playful and provocative fashion shows continue to draw national and international media attention (Lenz, Citation2008). In 2012, the Belém based sex worker rights organisation GEMPAC started Puta Dei (as in ‘day’), a day of cultural and advocacy activities to mark International Sex Workers Rights Day (June 2nd) that by 2014 had spread throughout Brazil. Such cultural actions are emblematic of sex worker activists’ ability to transform and adapt to diverse political contexts. Yet as we’ve attempted to show, their insistence on the central roles of sexuality, stigma and pleasure in preventing HIV has paradoxically been their greatest strength in weathering political upheavals and economic crisis (though they have not gone unscathed), and also their largest challenge to sustaining their organisational structures. The challenges presented by decentralisation, the growing power of the Evangelical lobby and (re)medicalisation of the epidemic made maintaining the affirmative stance towards prostitution in government funded actions difficult.

Pleasure and Putas at the Centre of a Response to HIV

In conclusion, we would like to highlight what we see to be unique aspects of the Brazilian prostitute movement’s approach to HIV prevention. First, by confronting stigma as the primary driver of the AIDS epidemic among sex workers early on, they made respecting sex work a bottom line for collaboration. It is critical to note that this meant affirming the right be a puta, both in the sense of a positive affirmation of a whore identity, and also the right to break with normative gender and sexuality stereotypes of what it means to be a woman. Second, affirmative cultural actions such as Puta Dei and Daspu brought the multiplicities of sex workers’ subjectivities to light and involved partners from a diverse range of fields. While increased dependence on conservative municipal and state governments for funding made maintaining organisational structures difficult (and in some cases, impossible), such strategies were critical to keeping sex worker rights visible and building key alliances outside state structures. Finally, through their advocacy and cultural actions, sex workers constantly shifted attention to the structural factors such as gender, sexuality and economic inequalities that influence sex workers’ vulnerability to HIV. From the focus on pleasure in Fala, Mulher da Vida to their recommendations for cross-sector alliances in the global and national consultations, the movement consistently called for sex workers rights as full citizens to be respected and promoted by the State.

Fighting stigma as a key driver of HIV has been central in social movements’ responses to the epidemic for decades (Gamson, Citation1989). Rather than sanitise sex, the movement’s approach to reducing sex work stigma was to associate it with both pleasure and professionalism. The affirmations that ‘sex is good’ and ‘you will have many moments of pleasure’ in the PREVINA materials is an example of how they addressed the stigma surrounding prostitution and women’s right to pleasure (and to charge for it). Examples of cultural activism (Crimp & Bersani, Citation1988; Ginsburg, Citation1997), Daspu and Puta Dei draw upon fashion, humour, and the body to engage culture as a site of contention and resignify prostitution. One of Daspu’s top selling t-shirts summarises their provocative approach to challenging prostitution stigma: ‘We’re bad, but we could be worse.’ Similar to the word whore in English, in Brazil, puta is also a fluid and transgressive category used to describe any woman who doesn’t conform to normative paradigms of gender and sexuality (Olivar, Citation2013). The reclaiming of the word puta and sexual behaviour associated with the subjective category connects the prostitute movement to broader feminist movements and vindications regarding women’s sexuality and sexual rights. As Roberto Domingues notes, sex workers have long demanded to be seen as women with health needs that go beyond ‘the waist down,’ yet their health and rights have continued to be addressed by the State exclusively in the context of HIV/AIDS, and often, as a separate group from cisgender women (Domingues, Citation2017, p. 17). Rather than confine the issue of prostitution to red light districts or HIV/AIDS, prostitute activist strategies such as Daspu and Puta Dei formed allies and partnerships with a variety of social actors from the fashion world, universities, media and artists that became even more important as State support for sex worker rights dwindled.

Michael Warner (Citation1999) has argued for the importance of counter-hegemonic discourses in the gay and lesbian rights movements, emphasising that until behaviours considered deviant are recognised and respected outside the spaces they have been confined to, larger scale social change, including the reduction of stigma and sexual freedoms, will be compromised. The word ‘whore,’ has also been important to sex worker activism in English speaking countries (Chateauvert, Citation2013; Gira Grant, Citation2014; Leigh, Citation2004; Pheterson, Citation1989). Over time, however, many activist groups in contexts like the United States where prostitution is completely criminalised chose to adopt the term ‘sex work’ in their political advocacy as a way to reinforce the idea of sex work as labour and be more inclusive of all people who engage in sexual commerce (Chateauvert, Citation2013, p. 193). The Brazilian Prostitute Network, on the other hand, has thus far chosen an approach similar to that of Warner. As we’ve attempted to argue here, however, they go beyond word choice to a way of organising and implementing HIV prevention actions that constantly challenge representations of prostitution by affirming their roles as political actors, not just peer educators, in fighting the epidemic. While the project based funding mechanisms created other problems for their actions in terms of sustainability (Galvão, Citation2000), we know both from experience and research that this sort of protagonist role is the backbone to any successful and human rights based response to HIV (Kerrigan et al., Citation2015; WHO, Citation2012).

Indeed, human rights approaches to health depend on a political environment in which all rights – not just those that have financial and political advantages – can be fully realised. At a time when such approaches have been incorporated into the international system, with groups such as the World Health Organisation endorsing structural approaches and decriminalisation of sex work as a way to fight HIV (WHO, Citation2012), we’ve shown how Brazil is going in the opposite direction. The (re)medicalisation of HIV prevention alongside the increased presence and power of the conservative lobby and neoliberalization of Brazil’s public health care system (Seffner & Parker, Citation2016) has meant that previous human rights discourses in prevention have been reduced to the right to be tested. This shift to individual, as opposed to more collective rights (such as legal changes and professional recognition) may contribute to increasing, rather than decreasing sex workers’ vulnerability to HIV.

In this context, we believe that it is increasingly important that there be a shift from looking up to the State, to looking across to other social movements. It was this type of wide mobilisation across the health, political activist and women’s movements that formed the foundation of Brazil’s response to HIV. The Brazilian Prostitute Network’s rights and pleasure based approach is precisely one that invests in fighting multiple fronts with creativity and conviction. Not only does such an approach build allies, it also forces a more structural as opposed to individual response by seeking points of convergence between movements. At a time when austerity measures threaten Brazil’s public health system, such alliances are critical not just for sex workers, but for the health of the population as a whole.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Anthropological research has been important to uncovering the nuances of the terms used to refer to sex work in Brazil (Kulick, Citation1998; Mitchell, Citation2016; Piscitelli, Citation2007; Silva & Blanchette, Citation2005) and noted how prostituta (prostitute) and puta (whore) are the terms preferred by the organised movement, although other terms such as trabalhadora sexual (sex worker) and professional do sexo (sex professional) are also used (Olivar, Citation2013; Williams, Citation2013). This remains an active discussion within the movement today. Do to the diversity of preferences and terms among activists and those not in the organised movement, we will use ‘prostitute/s’ and ‘sex worker/s’ interchangeably. We’ve chosen to leave the word puta in Portuguese due to its specificity as a subjective category in Brazil (Olivar, Citation2013).

2. Sex work is a recognized profession in Brazil in accordance with the Ministry of Labour’s Classification of Brazilian Occupations, yet all third party involvement, including brothel ownership, is illegal.

References

- ABIA, & DAVIDA. (2013). Analysis of prostitution contexts in terms of human rights, work, culture, and health in Brazilian cities. Rio de Janeiro: Brazilian Interdisciplinary AIDS Association - ABIA.

- Basthi, A., Parker, R., & Terto Júnior, V. (Eds.). (2016). Myth vs. reality: Evaluating the Brazilian response to HIV in 2016. Rio de Janeiro: Brazilian Interdisciplinary AIDS Association (ABIA) - Global AIDS Policy Watch.

- Basu, I., Jana, S., Rotheram-Borus, M., Swendeman, D., Lee, S. J., Newman, P., & Weiss, R. (2004). HIV prevention among sex workers in India. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 36(3), 845–852. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200407010-00012

- Berkman, A., Garcia, J., Munoz-Laboy, M., Paiva, V., & Parker, R. (2005). A critical analysis of the Brazilian response to HIV/AIDS: Lessons learned for controlling and mitigating the epidemic in developing countries. American Journal of Public Health, 95(7), 1162–1172. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054593

- Beyer, C., Crago, A.-L., Bekker, L.-G., Butler, J., Shannon, K., Kerrigan, D., … Strathdee, S. A (2015). An action agenda for HIV and sex workers. The Lancet, 385(9964), 287–301. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60933-8

- Biehl, J. (2014). Patient value. In E. Fischer (Ed.), Markets, values and moral economies (pp. 67–90). Santa Fe: SAR Press.

- Bogea, H. (2012, May 25). Na prostituição, aprendi a ver que a sociedade tem muitos problemas, e eu não era a errada da história. Retrieved from http://www.hiroshibogea.coms.br/lourdes-barreto-na-prostituicao-aprendi-a-ver-que-a-sociedade-tem-muitos-problemas/

- Brazilian Prostitute Network. (2013). Statement from the Brazilian Prostitute Network of Prostitutes about Censorship and the Federal Government's Intervention and Alteration of the AIDS Prevention Campaign. Retrieved from: http://www.akissforgabriela.com/?cbg_tz=180&cat=3&paged=6

- Burawoy, M. (1998). The extended case method. Sociologial Theory, 16(1), 4–33. doi: 10.1111/0735-2751.00040

- CBO. (2017). 5198:05 - Profissionais do Sexo. Retrieved from: http://www.mtecbo.gov.br/cbosite/pages/pesquisas/ResultadoFamiliaDescricao.jsf

- Chateauvert, M. (2013). Sex workers unite: A history of the movement from stonewall to slutwalk. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Colucci, C. (2016, May 17). Tamanho do SUS precisa ser revisto, diz novo Ministro da Saúde, Folha de São Paulo. Retrieved from http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/cotidiano/2016/05/1771901-tamanho-do-sus-precisa-ser-revisto-diz-novo-ministro-da-saude.shtml

- Corrêa, S. O. (2016). The Brazilian response to HIV and AIDS in troubled and uncertain times. In A. Basthi, R. Parker, & V. T. Júnior (Eds.), Myth v reality: Evaluating the Brazilian response to HIV in 2016 (pp. 7–15). Rio de Janeiro: Brazilian Interdisciplinary AIDS Association - ABIA - Global AIDS Policy Watch.

- Crimp, D., & Bersani, L. (1988). AIDS: Cultural analysis, cultural activism (1st ed.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Csete, J. (2013). Victimhood and vulnerability: Sex work and the rhetoric and reality of the global response to HIV/AIDS. In L. Murthy (Ed.), The business of sex (pp. 45–80). New Dehli: Zubaan.

- Daniel, H., & Parker, R. (1991). AIDS: A terceira epidemia (ensaios e tentativas). São Paulo: Iglu.

- Decker, M., Crago, A.-L., Chu, S., Sherman, S., Seshu, M., Buthelezi, K., … Beyer, C. (2015). Human rights violations against sex workers: Burden and effect on HIV. The Lancet, 385(9963), 186–199. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60800-X

- Dias, B. (2016). Golpe fatal: PEC 55 é aprovada em meio a manifestações e brutal repressão policial. Retrieved from: https://www.abrasco.org.br/site/noticias/movimentos-sociais/golpe-fatal-pec-55-e-aprovada-em-meio-a-manifestacoes-e-brutal-repressao-policial/24431/

- Domingues, R. (2017). A Batalha Entre Sujeito e Objeto no Sertão da Saúde. Beijo da Rua, 28(2), 15–17.

- Emerson, R. M., Fretz, R. I., & Shaw, L. L. (1995). Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Galvão, J. (2000). AIDS no Brasil: a agenda de construção de uma epidemia. Rio de Janeiro: ABIA.

- Gamson, J. (1989). Silence, death, and the invisible enemy: AIDS activism and social movement newness. Social Problems, 36(4), 351–367. doi: 10.2307/800820

- Ginsburg, F. (1997). From little things, big things grow: Ingidenous media and cultural activism. In R. Fox & O. Starn (Eds.), Between resistance and revolution: Cultural politics and social protest (pp. 188–144). New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Gira Grant, M. (2014). Playing the whore. London and New York: Verso.

- Gupta, G. R., Parkhurst, J. O., Ogden, J., Aggleton, P., & Mahal, A. (2008). Structural approaches to HIV prevention. The Lancet, 372, 764–775. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60887-9

- IBGE (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística) (2010). Censo Demográfico. Retrieved from: http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/censo2010/default.shtm

- Kerrigan, D., Kennedy, C., Morgan-Thomas, R., Reza-Paul, S., Mwangi, P., Win, K. T., … Butler, J. (2015). A community empowerment approach to the HIV response among sex workers: Effectiveness, challenges, and considerations for implementation and scale-up. The Lancet, 385(9963), 172–185. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60973-9

- Kerrigan, D., Moreno, L., Rosario, S., Gomez, B., Jerez, H., Barrington, C., … Sweat, M. (2006). Environmental-structural interventions to reduce HIV/STI risk among female sex workers in the Dominican Republic. American Journal of Public Health, 96(1), 120–125. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042200

- Kulick, D. (1998). Travesti. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Leigh, C. (2004). Unrepentant whore. San Francisco: Last Gasp.

- Leite, G., Murray, L. R., & Lenz, F. (2015). The peer and non-peer: The potential of risk management for HIV prevention in contexts of prostitution. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia, 18(Suppl 1), 7–25. doi: 10.1590/1809-4503201500050003

- Leite, G. (2013). Why Gabriela prefers the word whore? (YouTube video). Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CvKkGPiXv0o

- Lenz, F. (2008). Daspu: Moda Sem Vergonha. Rio de Janeiro: Objetivo.

- Lippman, S., Chinaglia, M., Donini, A., Kerrigan, D., Reingold, A., & Diaz, J. (2012). Findings from encontros: A multi-level STI/HIV intervention to increase condom use, reduce STI, and change the social environment among sex workers in Brazil. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 39(3), 209–216. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31823b1937

- Lorway, R., & Khan, S. (2014). Reassembling epidemiology: Mapping, monitoring and making-up people in the context of HIV prevention in India. Social Science & Medicine, 112, 51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.04.034

- Melo, D. (2016). Toda uma geração está condenada diz relator da ONU sobre a PEC 55. Carta Capital. Retrieved from: http://www.cartacapital.com.br/politica/toda-uma-geracao-esta-condenada-diz-relator-da-onu-sobre-a-pec-55

- Mgbako, C. A. (2016). To life freely in the world: Sex worker activsim in Africa. New York: New York University Press.

- Mitchell, G. (2016). Tourist attractions. Chicago: University of Chicago.

- MOH. (2008). Consulta nacional sobre DST/AIDS, Direitos Humanos e Prostituição. Brasilia: Ministry of Health.

- MOH. (n.d.). Projeto PREVINA. Brasilia: Ministry of Health.

- Murray, L. (2015). Not fooling around: The politics of sex worker activism in Brazil (PhD). Columbia University, New York.

- Nguyen, V.-K., Bajos, N., Dubois-Arber, F., O'Malley, J., & Pirkle, C. M. (2011). Remedicalizing an epidemic: From HIV treatment as prevention to HIV treatment is prevention. AIDS, 25, 291–293. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283402c3e

- Nunn, A. (2009). The politics and history of AIDS treatment in Brazil. New York: Springer.

- Okie, S. (2006). Fighting HIV-lessons from Brazil. New England Journal of Medicine, 354, 1977–1981. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068069

- Olivar, J. M. (2013). Devir puta: Políticas de prostituição de rua na experiência de quatro mulheres militantes. Rio de Janeiro: Ed UERJ.

- Paiva, C. H. A., & Teixeira, L. A. (2014). Reforma sanitária e a criação do Sistema Único de Saúde: notas sobre contextos e autores. História, Ciências, Saúde-Manguinhos, 21, 15–36. doi: 10.1590/S0104-59702014000100002

- Paiva, V., & Silva, V. (2015). Facing negative reactions to sexuality education through a multicultural human rights framework. Reproductive Health Matters, 23, 96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.rhm.2015.11.015

- Parker, R. (1987). Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in Urban Brazil. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 1, 155–175. doi: 10.1525/maq.1987.1.2.02a00020

- Parker, R. G. (1994). A AIDS no Brasil, 1982–1992. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: ABIA: IMS-UERJ : Relume Dumará.

- Parker, R. G. (2003). Building the foundations for the response to HIV/AIDS in Brazil: The development of HIV/AIDS policy, 1982–1996. Divulgação em Saúde para Debate, 27, 143–183.

- Parker, R., & Aggleton, P. (2014). Test and treat from a human rights perspective. Global AIDS Policy Watch. http://gapwatch.org/news/articles/test-and-treat-from-a-human-rights-perspective/118

- Patton, C. (2011). Rights language and HIV treatment: Universal care or population control? Rhtetoric Society Quarterly, 41(3), 260–266.

- Pheterson, G. (1989). A vindication of the rights of whores. Seattle: Seal Press.

- Piscitelli, A. (2007). Shifting boundaries: Sex and money in the North-East of Brazil. Sexualities 10(4), 489–500. doi: 10.1177/1363460707080986

- Rancière, J. (1999). Disagreement: Politics and philosophy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

- Rich, J. (2013). Grassroots bureaucracy: Intergovernmental relations and popular mobilization in Brazil's AIDS policy sector. Latin American Politics and Society, 55, 1–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-2456.2013.00191.x

- Rossi, L. (1998). Prevencao das DST/Aids e a Prostitucao Feminina no Brasil. Brasilia: Ministeiro de Saude: Coordenacao Nacional de DST e Aids.

- Rovai, R. (2013, June 6). Padilha explica por que não permitiu campanha “sou feliz sendo prostituta” [Padliha explains why he didn’t permit the campaign, “I’m happy being a prostitute]. Retrieved from http://revistaforum.com.br/blogdorovai/2013/06/11/padilha-explica-porque-nao-permitiu-o-sou-feliz-sendo-prostituta/

- Seffner, F., & Parker, R. (2016). The neoliberalization of HIV prevention in Brazil. In A. Basthi, R. Parker, & V. Terto Júnior (Eds.), Myth vs. reality: Evaluating the Brazilian response to HIV in 2016 (pp. 22–30). Rio de Janeiro: Brazilian Interdisciplinary AIDS Association (ABIA) - Global AIDS Policy Watch.

- Shannon, K., Strathdee, S., Goldenberg, S., Duff, P., Mwangi, P., Rusakova, M., … Boily, M. (2015). Global epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers: Influence of structural determinants. The Lancet, 385(9962), 55–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60931-4

- Silva, A. P., & Blanchette, T. (2005). Nossa Senhora da Help: Sexo, Turismo, e Deslocamento Transnacional em Copacabana. Cadernos Pagu, 1(25), 249–280. doi: 10.1590/S0104-83332005000200010

- Warner, M. (1999). The trouble with normal. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- WHO. (2012). Prevention and treatment of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases for sex workers in low and middle income countries. Geneva: World Health Organization. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/77745/1/9789241504744_eng.pdf?ua=1

- Williams, E. L. (2013). Sex tourism in Bahia: Ambiguous entanglements. Urbana, Chicago and Springfield: University of Illinois Press.