ABSTRACT

The mental health users’ movement is a worldwide phenomenon that seeks to resist disempowerment and marginalisation of people living with mental illness. The Latin American Collective Health movement sees the mental health users’ movement as an opportunity for power redistribution and for autonomous participation. The present paper aims to analyze the users’ movement in Argentina from a Collective Health perspective, by tracing the history of users’ movement in the Country. A heterogeneous research team used a qualitative approach to study mental health users’ associations in Argentina. The local impact of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the regulations of Argentina’s National Mental Health Law are taken as fundamental milestones. A strong tradition of social activism in Argentina ensured that the mental health care reforms included users’ involvement. However, the resulting growth of users’ associations after 2006, mainly to promote their participation through institutional channels, has not been followed by a more radical power distribution. Associations dedicated to the self-advocacy include a combination of actors with different motives. Despite the need for users to form alliances with other actors to gain ground, professional power struggles and the historical disempowerment of ‘patients’ stand as obstacles for users’ autonomous participation.

Introduction

The mental health users’ movement is about human rights, power distribution, recovery and also making profound changes to mental health services. A worldwide phenomenon, the movement seeks to resist the impact of disempowerment and marginalisation that people living with mental illness have historically experienced (Crane-Ross, Lutz, & Roth, Citation2006).

The mental health users’ movement has received attention in both high income and low and middle-income countries (Chamberlin, Citation1978; Kleintjes, Lund, & Swartz, Citation2013; Yaro & de Menil, Citation2010; Zinman, Citation2009). Though it has adopted heterogeneous characteristics and assumed varied pathways across countries and cultures, the users’ movement has consistently struggled to actuate a redistribution of power. Studies from high-income countries have shown that users’ participation in care and treatment, and in service and policy planning, has not been followed by an increase in decision making and, due to their mental diagnosis, their opinions have not been equally valued as those of professionals (Campbell, Citation2006; Carr, Citation2007; Connor & Wilson, Citation2006; Hodge, Citation2005; Lewis, Citation2009; Rose, Citation2001; Rutter, Manley, Weaver, Crawford, & Fulop, Citation2004; Wallcraft, Read, & Sweeney, Citation2003; Webb, Clifford, Fowler, Morgan, & Hanson, Citation2000). For example, a National Survey of Mental Health Services from Australia found that 46% of mental health services included users in their advisory committees, but only 8% had users in their management committees (Honey, Citation1999). In this sense, users’ participation is limited because professionals still control the process and the result of such participation (Broer, Nieboer, & Bal, Citation2014; Milewa, Dowswell, & Harrison, Citation2002).

The ethos of human rights, social inclusion, and power distribution inherent in the mental health users’ movement resonates with the Latin American Collective Health movement. Argentina, one of the countries where the Collective Health tradition has developed, has a long tradition of social activism and social participation from local grass-root movements (Retamozo, Citation2011; Waitzkin, Iriart, Estrada, & Lamadrid, Citation2001). Following scholars from the Collective Health tradition, we understand social participation as the process through which people take part in the development of actions that aim toward collective goals (Fassin, Citation2006; Menéndez, Citation2006). In this sense, social participation is seen as a psychosocial process where the personal level is articulated with the collective level, mutually constructing each other. Social activism and collective action are key to offering persons ‘the possibility of a joyful discovery of free action’ and, thus, constituting ‘the finest human experience’ (Hilb, Citation2013, pp. 30–31). This specific type of participation ranks high in order to attain full personhood in Argentina.

Particularly in the health field, social participation has been conceived simultaneously as a method --or a means-- and as a goal, a way to achieving health objectives and an indicator of health and citizenship (Menéndez, Citation2006). In addition, social participation is usually related to democracy as a system of political organisation, since it is through participation that power can be redistributed, transforming the social world, including mental health services and systems (Ferullo de Parajón, Citation2006; Rovere, Citation1999).

In the specific case of mental health services users, and under the framework of the Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities (United Nations, Citation2006), social participation has been considered as a fundamental right, as a way to gain social inclusion and to exercise full citizenship, and also as a way to challenge and transform the traditional psychiatric model of care. Social participation is key to the ‘dignity of risk’ --the dignity in making one’s own decisions and being responsible for their consequences (Basz, Citation2014), and has been conceptualised as the opposite of social exclusion (Burchardt, Le Grand, & Piachaud, Citation2002). Given the importance placed on social participation in the Collective Health movement in Argentina, autonomous participation by mental health service users defines a successful mental health service users’ movement from this perspective.

Context: mental health reforms in Argentina

Argentina is an upper-middle income country (World Bank, Citation2017), with significant social and health inequities and almost a third of its population under the poverty line.

The mental health system’s development has not been linear in Argentina. The first mental institutions were created in the second part of the nineteenth century. Several unconnected psychiatric reforms were attempted after 1950, some of them interrupted by military governments and neoliberal reforms, but also by disputes that have interfered with a nationwide mental health reform (e.g. trade unions resisting the closing of asylums because of a threatening loss of working opportunities for administrative and other support staff, power disputes between psychiatrists and psychologists, etc.) (Chiarvetti, Citation2008).

Currently, at a national level, the mental health system is heterogeneous. Psychiatric hospitals still prevail in terms of the distribution of beds for people with mental problems. An overwhelming majority of psychiatric beds (81.5%) are located in psychiatric hospitals (Di Nella et al., Citation2011). Most primary health care facilities include psychologists among their professional staff, and in the specific case of Buenos Aires, Argentina’s capital city, the highest psychologist to population ratio in the world can be found: one in 90 inhabitants is a psychologist (Alonso & Klinar, Citation2013).

A national mental health law was enacted in 2010, in the context of other important laws regarding vulnerable populations that were passed around the same time (e.g. gender identity, migrants, etc.). The success in passing this law has been attributed to a post-neoliberal government that was in power (Grugel & Riggirozzi, Citation2012) and the newly re-empowered social movements from the previous decades.

This 2010 national law followed a rights-based approach and, among other key aspects, mandated that users’ associations participate in psychiatric reform through institutional channels (Honorable Cámara del Senado de la Nación, Citation2010a). Those institutional channels for users’ participation were the Organo de Revisión (OR) or ‘Review Body’, responsible for monitoring how the law is being executed, and the Consejo Consultivo Honorario (CCH) or ‘Honorary Consulting Council’, charged with designing new mental health policy proposals. Both groups, the OR and the CHH, were explicitly required to have among their members a certain number of representatives of users’ associations (Ministerio de Salud, Citation2013). Thereafter, from the moment of the implementation of the law, several organisations self-defined as users’ associations developed.

The aim of this work is to describe and analyze from a Collective Health framework the recent history of the mental health users’ movement in Argentina, mapping key associations and their role in the movement. Specifically, we seek to analyze the extent to which the users’ movement fulfils the Collective Health ideal of users advocating for their own rights—i.e. people with similar experiences advocating for their own needs, collectively strengthening their voice (Mind, Citation2015; Walmsley, Citation2002).

Methods

The research team was composed of one clinician, eight researchers, and two activists.Footnote1 The research design followed a qualitative approach and included: literature review, document analysis, grey literature review, interviews, and participatory observation.

A literature review regarding the users’ participation, users’ perspectives, users’ movement and users’ associations in Argentina was conducted. The term ‘user’ was selected, in line with how these associations have chosen to name themselves in Argentina and how these social actors were named by the 2010 national mental health law (# 26.657). A Pubmed search was conducted using the terms ‘mental health’, ‘user’ and ‘Argentina’. Lilacs, Redalyc and Scielo databases were used with ‘salud mental’, ‘usuario’ and ‘Argentina’ in January 2017.

The analysis of documents included: The national mental health law (# 26.657) and its regulations (Ministerio de Salud, Citation2013), the verbatim transcriptions of the Senate’s debates during 2009 and 2010 in the preparation of the law, National Mental Health Direction’s documents and recommendations, and the human rights report -and its repercussions- on the state of inpatient units of people with mental illness living in several psychiatric hospitals, produced by human rights NGOs (MDRI/CELS, Citation2007). Sections regarding users’ participation were prioritised in search of activists and associations that could be key players in the field of users’ associations. Content analysis was also performed looking into themes relevant to users participating in advocacy activities.

Twenty-five newspapers (three with nationwide circulation and twenty-two local) were reviewed for articles on users’ associations participating in the reviewing body (OR). To be included, users’ associations had to fulfil two criteria: (a) They are composed of mental health services users and, (b) They are doing rights’ advocacy tasks and/or participating from the OR at any level.

Interviews were performed with key informants from the Asamblea de Usuarios/as de Salud Mental por Nuestros Derechos, or ‘Assembly of Mental Health Users for Our Rights’ (Santa Fe Province), from the Usuarios, Familiares y Amigos de los Servicios de Salud Mental, or ‘Users, Family Members and Friends of the Mental Health Services’ (Córdoba Province), and from the Asociación Manos Abiertas y Solidarias (AMAS), or ‘Association of Open Hands in Solidarity’ (Río Negro Province). Topics addressed covered their origins, composition, aims, activities, relationships with other associations, and barriers and facilitators for their daily work and for their intended objectives. A secondary analysis was performed based on a previous study conducted in Asamblea Permanente de Usuarios de los Servicios de Salud Mental (APUSSAM), or “Permanent Assembly of Mental Health Service Users” (Rosales, Citation2014) and with Red de Familiares, Usuarios y Voluntarios por los Derechos de las Personas con Padecimiento Mental (Red FUV), or ‘Network of Family Members, Users and Volunteers for the Rights of People with Mental Suffering’ (López Cirio, Bugoslawski, & Zucchelli, Citation2015). AMAS, APUSSAM and Red FUV participated as representatives of users’ associations in the OR and the CCH. The APUSSAM study analyzed the participation process in the assembly from the participants’ perspective, and the changes attributed to such participation. The Red FUV study focused on the participation of such association in the OR.

Grey literature of users’ associations (e.g. web pages, Facebook and blogs) was analyzed. Based on a previous search (Rosales, Fernández, Agrest, Ardila-Gómez, & Stolkiner, Citation2015), where 18 users’ associations had been identified, the Facebook, web pages and blogs of these associations were reviewed during 2016 in search of the activities performed by the associations. Their composition and links with other associations were integral to the analysis.

Five members of the research team participated in 2016 from the First National Meeting of Mental Health Service Users and acted as participant observers taking field notes and adopting different roles: One was part of the organising committee, two were activists and two others were non-user attendants.

Results

The literature review and secondary citation search identified eight papers focusing on user participation and perspective in Argentina (Agrest, Citation2011; Agrest et al., Citation2017; Ardila, Citation2011; Ceriani, Obiols, & Stolkiner, Citation2010; Michalewicz, Obiols, Ceriani, & Stolkiner, Citation2012; Rosales et al., Citation2015; Stolkiner, Citation2012; Tisera & Lohigorry, Citation2015).

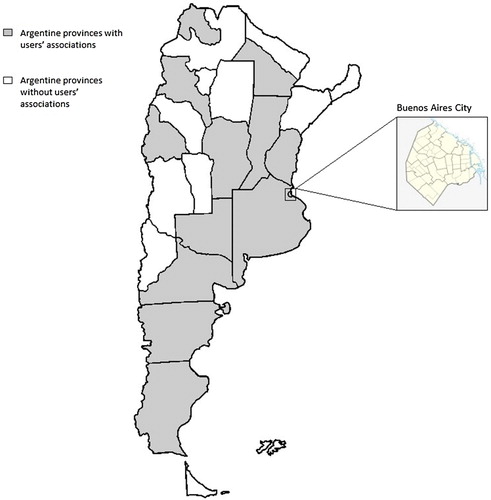

Through these articles, as well as the newspapers reviewed and the key informant interviews, we identified 26 users’ associations in Argentina distributed along 13 of 24 provinces that met the inclusion criteria by the time of the research (See ). None of the association had a national presence and many of them lacked a communication platform (e.g. Facebook, web page or blog) or had considerable delays updating them. Only two of the associations (Red FUV and APEF) have presence in more than one province and only Río Negro province has more than three associations in its territory.

The results are organised according to the two broad categories of analysis above mentioned:

For a historical analysis, two crucial events were considered: (a) The adoption of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) (UN, Citation2006), and (b) the regulations of the national mental health law in 2013 (Ministerio de Salud, Citation2013). These two milestones were selected because the CRPD is an international convention acknowledging the rights of people with disabilities that, at an international level, legitimatises Argentina’s later decision to adopt a rights-based mental health reform law. In addition, the regulations of the mental health law establish concrete areas for users to participate in public policies related to mental health in Argentina, and such regulations have implicitly defined users’ associations as those advocating or promoting users’ civil rights.

For the analysis of the current situation, we considered two major factors: a) How relationships are established among users participating in the associations and, b) how relationships are established between users and other actors (e.g. mental health professionals and family members). These relationships are integral to understanding the degree of users’ autonomous participation in Argentina.

Historical analysis of mental health users’ associations in Argentina

Early users’ associations

Based on the information analyzed, it was possible to establish that users’ associations existed before the CRPD, totalling six by 2006. The first associations of mental health services users were created between late 1980s and early 1990s. They were created around specific mental conditions, as indicated by their names, and they were organised based on mental health professionals’ recommendations or by users’ family members’ initiative. Fundación Bipolares Argentina (FUBIPA), or ‘Bipolar Foundation Argentina’, and Asociación Argentina de Ayuda a la Persona que Padece Esquizofrenia y su Familia (APEF), or ‘Argentinean Association for Helping People with Schizophrenia and their Family’, were described as direct predecessors of users’ associations (Agrest, Citation2011) but did not primarily consist of users advocating for their own rights (Ceriani et al., Citation2010). FUBIPA was created by a psychiatrist in 1989. APEF was created by family members of people diagnosed with schizophrenia in 1994. Their main impetuses when they were formed were: psychiatrists seeking treatment compliance, and family members seeking resources and information that could improve patients’ quality of life, respectively.

AMAS was founded in 1995 in the province of Río Negro. As described by one of its members, AMAS was born in connection to the local psychiatric reform process that culminated with the enactment of provincial mental health law in 1991, and was strongly promoted and supported by one psychiatrist in particular. Following the model of social entrepreneurships, a type of organisation developed by the Italian psychiatric reform (de Leonardis, Mauri, & Rotelli, Citation1995), it aimed for social inclusion through work.

Compared with other associations, AMAS has some features that align well with the Collective Health ideal of users’ rights: Unlike some other associations, it is legally and formally constituted, and rights are addressed in a ‘practical’ fashion, i.e. while other associations offer a more ‘theoretical’ approach to advocacy, AMAS centres its activities around offering working opportunities to people with mental illness through social entrepreneurships associated and dependent on it. AMAS has a formal board which is composed of twelve members: Nine of them are mental health professionals, two are family members of persons with mental illness and one is identified as a mental health service user.

Users organisations involved in the passage of the mental health reform law

The Red FUV association was created in July of 2006, and it is currently formed by relatives, mental health services’ users, volunteers, students and mental health professionals. Red FUV actively participated in the debates surrounding the enactment of the national mental health law (Honorable Cámara de Senadores de la Nación, Citation2010b).

After the enactment of the mental health law, jointly with the Panamerican Health Organization (PAHO), Red FUV convened in 2011 the ‘First National Meeting of Latin American Relatives, Users and Volunteers advocating for Human Rights in Mental Health’, supported by the National Direction of Mental Health and Substance Abuse. A Latin American network of users, relatives and volunteers for the Human Rights in Mental Health was also created during that meeting (PAHO, Citation2011). Two years later, in 2013, Red FUV participated in PAHO’s ‘First Regional Meeting of Mental Health Services’ users and their relatives’ (PAHO, Citation2013).

The Asamblea Permanente de Usuarios de Servicios de Salud Mental (APUSSAM) was created in 2007 in Buenos Aires City with a close collaboration from the Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales (CELS), or Center of Legal and Social Studies, an emblematic human rights organisation. According to a former participant from APUSSAM, this association did not emerge from users’ activities but from CELS’ interest in generating a space where the rights of persons with psychosocial disabilities could be discussed --specifically, their rights to be involved in the planning and execution of mental health policies centred on the CRPD. After ten years of uninterrupted work, APUSSAM still meets at the CELS’ offices, on a fortnightly basis. APUSSAM is centred on raising awareness regarding the rights of mental health service users so other users can acknowledge their own rights and can advocate for themselves. Members of APUSSAM participated in the editing of the national mental health law drafts and, after it was passed, APUSSAM had representatives in the CCH and the provincial OR of Buenos Aires Province.

Users’ organisations arising after the mental health reform law

After the passage of the national mental health law, users’ association blossomed across the country in direct response to the creation of local ORs and their legal mandate to include users. Seven associations, included in our list of 26 existing associations, were created between 2013 and 2016. However, despite the rapid rise of users’ organisations, a national or articulated users’ movement was not clearly seen.

Participants from two users’ associations that were created after 2013 were interviewed for this study: (1) The Asamblea de Usuarios/as de Salud Mental por Nuestros Derechos, was created in the city of Rosario, Santa Fe Province, in 2013. This association started as an extension programme from the university. An initial group composed of faculty members, students and other mental health professionals convened users from several mental health services. This new group, the majority of members being users, began to function as an assembly. (2) The association Usuarios, Familiares y Amigos de los Servicios de Salud Mental, was created in the city of Córdoba, Córdoba Province, in 2014. This association was initiated by one user and university faculty members who were also part of the staff of an asylum but just a few months later this user continued on his own and constituted a ‘one-participant association’.

For a two-year period, starting in 2013, Red FUV was the users’ association taking part in the national OR. Their representatives noted several benefits from participating in the OR: Sharing their experiences of living with mental suffering and their struggle finding appropriate care from different health care providers, identifying and disputing stigmatising or degrading daily practices that had become naturalised by mental health professionals, and producing/receiving materials created by mental health service users rather than the medico-legal community (López Cirio et al., Citation2015).

The other body in which users’ associations participated was the CCH. For APUSSAM’s and for AMAS’ members, participating in the CHH was considered important. According to AMAS participants, being part of the CHH gave them the opportunity to interact with other users across the country and mutually share their experiences. For APUSSAM’s participants it was more about ‘conquering’ their right to participate in the development of mental health policies in concordance with the CRPD and with the national mental health law. APUSSAM’s members mentioned that they felt as if they were ‘regarded as citizens and not only as mental health services users’ (Rosales & Ardila-Gómez, Citation2017).

In 2016 the National Mental Health and Substance Abuse Direction withdrew most of the support to users’ participation it had been given by the previous administration. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that users continue their organisation and a first national meeting of users was held in 2016.

Current analysis of users participating in associations dedicated to advocacy tasks

Participants from APUSSAM who were interviewed and had been involved in the 2010 mental health law preparation expressed that they had felt ‘excited to become members of the Consulting Honorary Council’ and acknowledged several benefits drawing from their participation: ‘[Having a] more positive way of seeing reality and themselves’ and ‘making recovery a reality through helping others’. ‘Greater consciousness of achieved rights and others pending to be achieved’, ‘an evolving identity linked to activism instead of patienthood’ and ‘configuring a new sense of citizenship’ were integral to this transformation (Rosales & Ardila-Gómez, Citation2017).

One user, as an indicator of successful participation and activism, mentioned that he had been ‘able to reach out to thousands of people, sharing ideas and news regarding mental health treatment, and even to debate with a prestigious mental health professional.’ Taking note of this remark, an activist expressed the challenge of users needing to organise themselves when everyone around is denying them full citizenship.

The mental health law has changed, but patronising attitudes by professionals have not. Closing down the asylums and moving to a community care approach, on behalf of mental health professionals, have been the central aspects of mental health rights’ fight. Despite users’ recognition of the importance of this fight, some of the interviewed users expressed that other needs--and infringed rights--would go ‘beyond psychiatric hospital walls’ and should be addressed. Demanding full citizenship is a much broader request than demanding better mental health services or human rights being respected during hospitalisations.

‘By’ users or ‘for’ users

Family members, mental health professionals, academic institutions, non-government organisations, and state organisms, had a decisive role at the beginning of every users’ association. As presented above, in many occasions these actors’ participation was crucial in supporting or maintaining users’ associations. In some cases, the leadership roles were adopted by non-users--despite users having the original initiative. An association located in Entre Ríos Province is representative of this situation: A user convened other users, but it was a mental health professional who ultimately remained as the head of the organisation.

Even if from the perspective of the CRPD it may be understandable that users’ associations may have needed non-users acting as collaborators, it remains unanswered why and how these supports remained as a necessity. In a comparison between building houses and building users’ associations, a mental health activist told us:

When you build a house, engineers and architects may be needed. But once the house is ready they don’t stay living in the house. In the case of users’ associations, professionals do stay.

Although financial support was considered to be necessary, and support as defined by the CRPD was welcome, paternalism and interference by mental health professionals were criticised. Rather than wanting greater support from professionals, activists complained about the existence of too much interference from professional organisms and mental health professionals posing barriers to mental health users to organise by themselves.

According to a participant from the ‘First National Meeting of Mental Health Services Users, for a society without asylums,’ in 2016, in Rosario, Santa Fe Province, ‘a few users attending the reunion were still hospitalised in asylums, and some others were coming with their relatives or with mental health professionals.’ (…) ‘Not many users/activists were there on their own.’ Dependency on relatives or professionals and the existence of asylums were considered as barriers for a full activism.

Nevertheless, some steps have also been taken to move away from paternalism. The 2016 users’ national meeting was convened and organised by the local assembly of users, and funding was provided by the extension programme at the university. Some activities and debates were for users only--and non-users were invited to stay outside. As an activist said, sustaining such differences and excluding non-users from specific activities or decisions may be necessary for the users’ movement to strengthen.

Battleground for professional power

Users’ associations striving for self-advocacy had to navigate an ongoing professional battle between psychologists and psychiatrists. The national mental health law had a profound effect and divided the mental health professionals: Most psychiatrists stood against several of its principles (e.g. closing down the asylums, allowing other mental health professionals to be the head of mental health units, etc.) while a majority of psychologists advocated for passing the law. In the passage and implementation of the mental health law, ample participation of mental health service users was mandated, however registered users’ associations were scarce by the time the mental health law was enacted, and participation from users was fraught with the challenges described above. Therefore, mental health professionals saw a role as ‘mental health user advocate’ --also influencing the mental health reform in their favour.

On some occasions, users reported suspicion of mental health professionals having a different agenda. An activist told us:

“I fight to promote users’ rights and users’ mental health, but the professionals are there for a political fight that has nothing to do with mental health” (…) “There are no mental health professionals working in the association right now … And I would look sideways at them if there were.”

Discussion

From the analysis of data on the mental health service users’ movement in Argentina, we see both great potential for, as well as challenges to power redistribution and users’ self-advocacy. Mental health professionals and users’ families have a central role in the history and current activities of many associations, casting doubt on the potential of these associations to contribute to power redistribution. A similar doubt arises for the institutional channels offered by the State to guarantee the users’ participation (e.g. OR and CCH) and whether through these initiatives the users’ movement will be strengthened or, instead, appeased or co-opted. It is yet to be determined if mental health service users, who have historically been disempowered, can actually benefit from these alliances or if they are succumbing to these greater powers.

On the other hand, in its current form, the users’ movement in Argentina may not be able to oppose psychiatrists and other mental health professionals who have been historically empowered. It remains to be determined which actors could help users become an independent and strong counter-power. By establishing an alliance with human rights advocacy associations, users have tended to be seen as ‘survivors of human rights violations perpetrated mostly by mental health workers.’ By establishing an alliance with psychologists, users have tended to be seen as ‘patients’. And when establishing alliances with people from the academia, users’ identity tended to be as ‘object of study.’ This oversimplification should take into consideration that each of these potential allies may present a wide range of alternatives: Psychologists can centre their approach on disabilities or can have a recovery orientation, people from the academia can have a radical positivist stance or can base their work on critical theory. Overall, such necessary alliances may pose specific challenges and opportunities for the users’ movement.

Our diverse team reflected the differences in the data analysis between a professional and a users’ perspective. While mental health professionals highlighted the disputes regarding the national mental health law, activists perceived the whole professional field as having an overprotective attitude towards them and a neglecting attitude towards the CRPD.

In Argentina, as in other parts of the globe, the users’ movement has not entirely gained autonomy from other actors and powers. It remains unanswered how mental health service users could create associations and organise themselves in order to claim the unrestricted fulfilment of the CRPD when they are not acknowledged by their communities with full legal capacities.

Ultimately, the Argentine Collective Health perspective sees the users’ movement as a social actor that intends to go beyond making mental health services more ‘humane’ and, instead, to fully actualize their human rights. Whilst many mental health professionals tend to see it as ‘domestic’ problem, activists consider it a much broader and general problem.

In conclusion, embracing the right to self-determination and autonomy may be revolutionary, but it is the goal of Argentinean activists participating from users’ movements, who believe, taking the perspective of Latin American Collective Health, that users should be listened to in terms of persons fighting for rights instead of patients claiming services.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Sara Ardila-Gómez http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0022-7438

Martín Agrest http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3756-2229

Marina A. Fernández http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5767-4047

Melina Rosales http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5707-9467

Alberto Rodolfo Velzi Díaz http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6304-2150

Santiago Javier Vivas http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0119-6685

Guadalupe Ares Lavalle http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0027-1540

Pamela Scorza http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8895-8675

Alicia Stolkiner http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9372-7556

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. In the text the term ‘activist’ refers exclusively to social activists who simultaneously or previously self-defined as service users and who have chosen to name themselves as ‘activists’.

References

- Agrest, M. (2011). La participación de los usuarios en los servicios de salud mental. Vertex, Revista Argentina de Psiquiatría, 22(100), 409–418.

- Agrest, M., Barruti, S., Gabriel, R., Zalazar, V., Wikinski, S., & Ardila-Gómez, S. (2017). Day hospital treatment for people with severe mental illness according to users’ perspectives: What helps and what hinders recovery? Journal of Mental Health, 13, 1–7.

- Alonso, M., & Klinar, D. (2013). Los Psicólogos en Argentina. Relevamiento Cuantitativo 2012. Congreso internacional de investigación y práctica profesional en Psicología. Noviembre, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina.

- Ardila, S. (2011). La inclusión de la perspectiva de los usuarios en los servicios de Salud Mental. Vertex, Revista Argentina de Psiquiatría, 22(95), 49–55.

- Basz, E. (2014). La dignidad del riesgo como antídoto al estigma. Retrieved from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/20140703134507-15416747-la-dignidad-del-riesgo-como-antidoto-al-estigma

- Broer, T., Nieboer, A. P., & Bal, R. (2014). Mutual powerlessness in client participation practices in mental health care. Health Expectations, 17(2), 208–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00748.x

- Burchardt, T., Le Grand, J., & Piachaud, D. (2002). Degrees of exclusion: Developing a dynamic,multidimensional measure. In J. Hills, J. LeGrand, & D. Piachaud (Eds.), Understanding social exclusion (pp. 30–43). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Campbell, P. (2006). Changing the mental health system – a survivor’s view. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 13, 578–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2006.00983.x

- Carr, S. (2007). Participation, power, conflict and change: Theorising dynamics of service user participation in the social care system of England and Wales. Critical Social Policy, 27(2), 266–276. doi: 10.1177/0261018306075717

- Ceriani, L., Obiols, J., & Stolkiner, A. (2010). Potencialidades y obstáculos en la construcción de un nuevo actor social: Las organizaciones de usuarios. Memorias del II Congreso Internacional de Investigación y práctica profesional en Psicología. XVII Jornadas de Investigación y Sexto Encuentro de Investigadores en Psicología del Mercosur. Facultad de Psicología, Universidad de Buenos Aires.

- Chamberlin, J. (1978). On our own: Patient controlled alternatives to the mental health system. Michigan: Haworth Press.

- Chiarvetti, S. (2008). La reforma en salud mental en Argentina: una asignatura pendiente. Sobre el artículo: hacia la construcción de una política en salud mental. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 17, 173–183.

- Connor, S. L., & Wilson, R. (2006). It’s important that they learn from us for mental health to progress. Journal of Mental Health, 15(4), 461–474. doi: 10.1080/09638230600801454

- Crane-Ross, D., Lutz, W. J., & Roth, D. (2006). Consumer and case manage perspectives of service empowerment: Relationship to mental health recovery. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 33, 142–155. doi: 10.1007/s11414-006-9012-8

- de Leonardis, O., Mauri, D., & Rotelli, F. (1995). La Empresa Social. Buenos Aires: Nueva Visión.

- Di Nella, Y., Sola, M., Calvillo, L., Negro, L., Paz, A., & Venesio, S. (2011). Las camas del sector público como indicador del proceso de cambio hacia el nuevo paradigma, mayo 2010-mayo 2011. Revista Argentina de Salud Pública, 2(8), 43–46.

- Fassin, D. (2006). Entre ideología y pragmatismo. Ambigüedades y contradicciones de la participación comunitaria en salud. In E. L. Menéndez y H. Spinelli (Eds.), Participación Social. ¿Para qué? (pp. 117–143). Buenos Aires: Lugar Editorial.

- Ferullo de Parajón, A. (2006). El triángulo de las tres p: Psicología, participación y poder. Santiago del Estero: Paidós Tramas Sociales.

- Grugel, J., & Riggirozzi, P. (2012). Post-neoliberalism in Latin America: Rebuilding and reclaiming the state after crisis. Development and Change, 43(1), 1–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7660.2011.01746.x

- Hilb, C. (2013). Usos del pasado. Qué hacemos hoy con los setenta. Buenos Aires: Ed. Siglo XXI.

- Hodge, S. (2005). Participation, discourse and power: A case study in service user involvement. Critical Social Policy, 25(2), 164–179. doi: 10.1177/0261018305051324

- Honey, A. (1999). Empowerment versus power: Consumer participation in mental health services. Occupational Therapy International, 6(4), 257–276. doi: 10.1002/oti.101

- Honorable Cámara de Senadores de la Nación. (2010a). Sesión plenaria de la Legislación General, Justicia y Asuntos penales, Salud y Deporte, y Presupuesto y Hacienda. Versión taquigráfica. 23 de Noviembre, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

- Honorable Cámara de Senadores de la Nación. (2010b). Ley #26.657. Ley Nacional de Salud Mental.

- Kleintjes, S., Lund, C., & Swartz, L. (2013). Organising for self-advocacy in mental health: Experiences from seven African countries. African Journal of Psychiatry, 16, 187–195.

- Lewis, L. (2009). Politics of recognition: What can a human rights perspective contribute to understanding users’ experiences of involvement in mental health services? Social Policy and Society, 8(2), 257–274. doi: 10.1017/S1474746408004776

- López Cirio, L., Bugoslawski, T., & Zucchelli, J. (2015). Análisis del trabajo conjunto entre el Órgano de Revisión Nacional de la Ley de Salud Mental # 26657 y la Red FUV, durante el primer período de acción (2014/2015): potencialidades y obstáculos. Final work. Presented in the Professional Practice on Research (code 818). Facultad de Psicología, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina.

- Menéndez, E. (2006). Las múltiples trayectorias de la participación social. In E. L. Menéndez y H. Spinelli (Eds.), Participación Social. ¿Para qué? (pp. 51–80). Buenos Aires: Lugar Editorial.

- Mental Disability Rights International & Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales (MDRI & CELS). (2007). Vidas arrasadas. La segregación de las personas en los asilos psiquiátricos argentinos. Retrieved from http://www.cels.org.ar/common/documentos/mdri_cels.pdf

- Michalewicz, A., Obiols, J., Ceriani, L., & Stolkiner, A. (2012). Usuarios de servicios de salud mental: del estigma de la internación psiquiátrica a la posibilidad de hablar en nombre propio. IV Congreso Internacional de Investigación y práctica profesional en Psicología. XIX Jornadas de Investigación y VIII Encuentro de Investigadores en Psicología del Mercosur. Ediciones de la Facultad de Psicología, Universidad de Buenos Aires.

- Milewa, T., Dowswell, G., & Harrison, S. (2002). Partnerships, power and the “new” politics of community participation in British health care. Social Policy and Administration, 36(7), 796–809. doi: 10.1111/1467-9515.00318

- Mind, National Association for Mental Health. (2015). Guide to advocacy. London: Mind.

- Ministerio de Salud de la Nación. (2013). Reglamentación de la ley de salud mental # 26.657. Act 603/13. Retrieved from http://servicios.infoleg.gob.ar/infolegInternet/anexos/215000-219999/215485/norma.htm

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). (2011). Buenos Aires Consensus. Retrieved from http://www.paho.org/arg/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=778&Itemid=269

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). (2013). Brasilia Consensus (Newsletter). Retrieved from http://www.paho.org/bulletins/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1689:brasilia-consensus-&Itemid=0&lang=en

- Retamozo, M. (2011). Movimientos sociales, política y hegemonía en Argentina. Polis, Revista de la Universidad Bolivariana, 10(28), 243–227.

- Rosales, M. (2014). Análisis de la Relación entre la Participación en Asociaciones de Usuarios de Servicios de Salud Mental y el Ejercicio de Derechos: Perspectiva de los Usuarios. Estudio de Caso en una Asociación de Usuarios en la Ciudad de Buenos Aires, 2014. Retrieved from: http://www.psi.uba.ar/investigaciones.php?var=investigaciones/ubacyt/becarios/finalizados/estimulo/rosales.php

- Rosales, M., & Ardila-Gómez, S. (2017). El proceso de implementación de la Ley Nacional de Salud Mental: obstáculos y desafíos: ¿Qué dicen los usuarios de servicios de salud mental? I Congreso Provincial de Salud Mental y Adicciones. Ciudad de Tandil, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

- Rosales, M., Fernández, M., Agrest, M., Ardila-Gómez, S., y Stolkiner, A. (2015). Asociaciones para, con y de usuarios de servicios de salud mental: elementos para su conceptualización y desarrollo. I Congreso Latinoamericano de Salud Mental: “Los rostros actuales del malestar”, Salta, Argentina.

- Rose, D. (2001). Users’ voices: The perspectives of mental health service users on community and hospital care. London: The Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health.

- Rovere, M. (1999). Planificación estratégica en salud: Acompañando la democratización de un sector en crisis. Cuadernos Médico Sociales, 75, 31–63.

- Rutter, D., Manley, C., Weaver, T., Crawford, M., & Fulop, N. (2004). Patients or partners? Case studies of user involvement in the planning and delivery of adult mental health services in London. Social Science and Medicine, 58, 1973–1984. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00401-5

- Stolkiner, A. (2012). Subjetividad y derechos: las organizaciones de usuarios y familiares como nuevos actores del campo de la salud mental. Revista Intersecciones Psi. Revista Virtual de la Facultad de Psicología de la UBA, 2(4). Retrieved from http://intersecciones.psi.uba.ar/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=134:las-organizaciones-de-usuarios-y-familiares-como-nuevos-actores-del-campo-de-la-salud-mental&catid=17:investigaciones&Itemid=1

- Testa, M. (2007). Pensamiento estratégico y lógica de programación. Buenos Aires: Lugar Editorial.

- Tisera, A., & Lohigorry, J. (2015). Sentido y significados sobre servicios de salud mental desde la perspectiva de usuarios/as, en la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires. Anuario de Investigaciones, 22, 263–271.

- The United Nations (UN). (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html

- Waitzkin, H., Iriart, C., Estrada, A., & Lamadrid, S. (2001). Social medicine then and now: Lessons from Latin America. American Journal of Public Health, 91(10), 1592–1601. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.10.1592

- Wallcraft, J., Read, J., & Sweeney, A. (2003). On our own terms: Users and survivors of mental health services working together for support and change. London: The Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health.

- Walmsley, J. (2002). Principles and types of advocacy. In B. Gray, & R. Jackson (Eds.), Advocacy and learning disability (pp. 24–37). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Webb, Y., Clifford, P., Fowler, V., Morgan, C., & Hanson, M. (2000). “Comparing patients” experience of mental health services in England: A five-trust survey. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 13(6), 273–281. doi: 10.1108/09526860010373253

- World Bank. (2017). World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Retrieved from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups

- Yaro, P., & de Menil, V. (2010). Lessons from the African user movement: The case of Ghana. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291577383_Lessons_from_the_African_user_movement_the_case_of_Ghana

- Zinman, S. (2009). History of the consumer/survivor movement. Bethesda: SAMHSA, ADS Center.