ABSTRACT

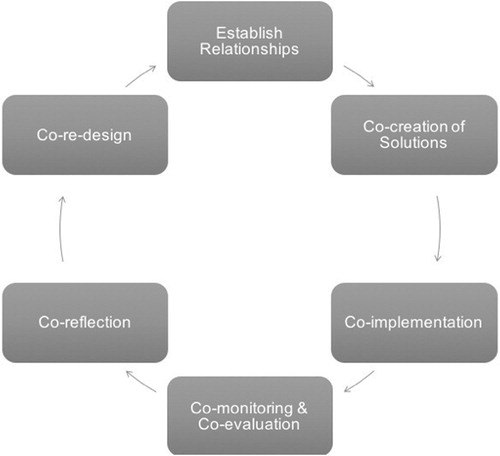

In low-income townships, pests are rife, a nuisance and are vectors of disease. Although alternatives are available, chemical means of pest control is often the first resort due to lack of knowledge of other methods, convenience and presumed efficacy. The demand for chemical pest control has created a unique business opportunity for informal vendors in South Africa servicing predominately low socio-economic communities. That is the selling of ‘street pesticides’, which are either containing agricultural pesticides too toxic for domestic use or illegally imported products. Poisonings from street pesticide exposures, particularly in children, are increasingly common and, along with pest-related diseases, creates a double burden of disease. Solutions are needed to decrease these incidences and to develop pest control strategies that are low- or non-toxic. It is imperative that, for sustainable problem-solving, all stakeholders, including vendors, be part of the solution in tackling this public health issue. This manuscript outlines an engaged scholarship approach for developing a sustainable resolution for reducing street pesticide use. This cyclical and iterative approach encompasses: the establishment of relationships, co-creation of solutions, co-implementation, co-monitoring, co-evaluation, co-reflection and co-re-design. The significance of the research and proposed engagement are discussed, as are anticipated challenges.

Introduction

Inadequate or non-existent service delivery, such as removal of refuse and limited provision of sanitation services, overcrowded living conditions and living in poverty in South Africa’s townships foster an optimal environment for the habitat and breeding of pests (Rother, Citation2010). Pests such as rats, cockroaches and bed bugs are rife in these low-income townships and, are not only a nuisance to residents through biting behaviour, but can also be vectors of disease (Adamkiewicz et al., Citation2014; Rother, Citation2016).

Global projections of climate change include a warmer future with increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather events (IPCC, Citation2014) which favour disruptions to vector activity, distribution and survival, pathogen transmission and feeding behaviour (Barata, Citation2017; Gubler et al., Citation2001; Hunter, Citation2003; Shuman, Citation2010; Zell, Citation2004). This is particularly of concern for low-income, high density communities that already experience high levels of pest infestation. Furthermore, indirect consequences of climate change and rising sea-levels may cause a continued increase in overcrowding and poor living conditions as environmental refugees migrate to areas of greater economic opportunities after livelihoods have been disrupted. An influx of people to high density communities increases pressure on service delivery systems, public health infrastructure and resource availability, ultimately increasing vulnerability. Indeed, new vectors and pathogens might arise due to increased temperatures in regions where they previously did not exist. In an effort to manage this increased pest load, the concern is the likely increased use of chemical pest control and exposure to highly hazardous products (Boxall et al., Citation2009; Harrus & Baneth, Citation2005; Zinyemba, Archer, & Rother, Citation2018).

Indeed, low-toxicity pest control methods, such as glue traps, spring traps and fly sticky tape are available for purchase in low-income, high density communities (). However, research in Cape Town’s low-income townships identified that residents often resort to using chemical methods of pest control as a first port of call, which are sold informally as street pesticides (Rother, Citation2010, Citation2016). There are two main types of street pesticides. The first type is pesticides registered for agricultural uses, decanted into unlabelled drink bottles and plastic packets. Their high acute toxicity and high concentrations of the active ingredients make these chemicals too toxic for domestic use (Ibitayo, Citation2016; Rother, Citation2010). The second type of street pesticides is those that are in labelled packaging, often from China, but are not legally registered for use in South Africa. Many of these products are neurotoxins (Rother, Citation2010). The main pesticide legislation is outdated in South Africa (Act 36 of 1947). Regulations focus on the sale of pesticides in the formal sector and not the informal sector other than making decanting of agricultural pesticides an illegal practice.

Figure 1. Low toxicity alternatives and street pesticides sold on the streets of a low-income community in Cape Town, South Africa.

Street pesticides are conveniently accessible from vendors at informal markets, on trains and at taxi ranks (Rother, Citation2016). The vendors are a transient population with no formal shop space or registrations. Rother (Citation2016) provides a detailed profile of informal vendors selling street pesticides in South Africa’s low-income communities. Swartz, Levine, Rother, and Langerman (Citation2018) discusses the toxic layering of street pesticides being sold and poisoning children in a context of social injustices and economic inequality. In general, informal vendors are often middle-aged women (ages range from the youth to the elderly) working in the informal economy. Some of the informal vendors are migrants from neighbouring countries in search of better employment and socio-economic opportunities. The foreign vendors that we engaged with in the local area of Cape Town are mostly from Zimbabwe. Zimbabweans are known for their high education level given that education is free and has been of a high standard (UNESCO, Citation2019). However, even with a good education level, many informal vendors may well have not had access to information on the hazards of handling and selling street pesticides. As Rother (Citation2016) indicates, poor socio-economic status increases the vulnerability of the informal vendor resulting in ‘trading health for income’. This illustrates the importance of engaging with informal vendors to develop a trust in selling non-chemical products and reducing adverse health effects while still earning a viable income.

Street pesticides are often cheaper than commercially available products. Due to the highly hazardous active ingredients, street pesticides are also very effective in killing pests (Rother, Citation2010). The selling of street pesticides can be a lucrative business for informal vendors in Cape Town and in other low-income areas globally where pest infestation is problematic. Assessing product costs, Rother (Citation2010) found that aliquoting a single bottle of pesticide into smaller quantities could result in a return on investment of up to five times the initial cost. South Africa has a high unemployment rate and selling street pesticides offers vendors an income. Selling and domestic use of street pesticides in low-income townships is a silent public health issue. Poisonings as a result of street pesticide exposure and domestic use are rising, especially amongst children (Balme et al., Citation2010; Balme, Roberts, Glasstone, Curling, & Mann, Citation2012), notwithstanding the health risks posed to the vendor themselves (Rother, Citation2016). Thus, a double disease burden is present in low-income townships of pest-related diseases and pesticide poisonings. A few informal vendors do sell low-toxic alternatives to pest control, alongside street pesticides (), but are reluctant to only sell these low-toxic alternatives given the poor reported efficacy of these methods from customers (personal communication with an informal vendor). Thus, what is needed are low-toxic (or preferably non-toxic) alternatives for pest control which are effective and affordable that informal vendors can sell and promote. Furthermore, highlighting the health risks of selling chemical methods of pest control for both the vendor and the community is also required to reduce the selling and use of street pesticides.

If there is to be a sustainable reduction in street pesticide retail and use, it is imperative that informal vendors along with other key stakeholders work together for sustainable and feasible solutions. These would need to be economically profitable for the informal vendors to ensure their buy-in and have proven efficacy for community buy-in. Simultaneously, improving service delivery, such as refuse removal, improved sanitation to low-income townships and adaptive interventions to climate change would further assist with reducing pest populations and the need for pest control, chemical or otherwise. However, this requires resource allocation and commitment from multiple municipal and provincial government departments and thus, is considered a longer-term approach. Another strategy is to regulate the placement on the market of highly hazardous pesticides. Within the informal sector however, regulating a pesticide does not necessarily remove it from circulation. A risk that could occur is that the removal or banning of one pesticide might lead to replacement with another equally toxic chemical alternative. It is imperative then that pest management strategies which are low- or non-toxic to humans be developed, accessible to low-income communities, and implemented in a sustainable and stakeholder engaged manner. In this manuscript, we explore the process and means of facilitating research engagement around a complex issue and illegal practice with a transient informal work force as part of the project planning phase.

Engaged scholarship approach

As early as Citation1996, Boyer urged academics to reflect on the overall purpose of research in addressing current problems of our communities and cities; particularly to ensure communication with civil society, such that universities are viewed as ‘staging grounds for action’ rather than isolated silos of knowledge generation. More recently, Cooper (Citation2017) explores the broader concept of engaged scholarship against applied and public sociology. Engaged scholarship spans many academic disciplines such as engineering, public health and fine art, not only sociology. Furthermore, engaged scholarship intentionally benefits the public, or is specifically for the purpose of the public, whilst engaging non-academic constituencies in knowledge production, integration, application or dissemination (Cooper, Citation2017; University of Cape Town, Citation2012). As Packman, Rutt, and Williams (Citation2017) state, the role of the academic has changed, and research should now have an impact beyond academia which is facilitated by a shift in language and perspective. There needs to be reconceptualisation of who is the ‘professional community’, who contributes to shared knowledge where meaningful interactions should be of mutual benefit; particularly low socio-economic communities in this case. It is within this ethos of collaboration, communication and participatory action that our engaged scholarship approach is formed for providing a conceptual framework to address challenges through working with key stakeholders to co-create and identify sustainable pest management solutions.

outlines our proposed engaged scholarship approach highlighting that engagement is not a solitary interaction but a process of collaboration occurring through iterative stages that are cyclical. This is particularly key with a transient population such as informal vendors. The continuity of the process is thus not individual based but rather based on continuity of engagement with persons representing the issue, that is, street pesticides in this case. The ultimate goal of this process is the co-construction of knowledge to develop sustainable solutions particularly for this case of informal vendors selling street pesticides. In this scenario, the ultimate goal of this process is the co-construction of knowledge to develop sustainable solutions to low- or non-toxic pest control that will reduce reliance on hazardous chemicals, especially street pesticides, whilst not undermining the economic livelihoods of informal vendors.

Figure 2. Cyclical and iterative engaged scholarship framework to foster stakeholder engagement to improve public health.

Establish relationships

To launch the process of working collectively together, there is a need to establish ‘relationships’ with stakeholders which in this case would be relevant academics, community members, city officials and informal vendors. Relationships in this instance refer to a partnership that is sustainable and long-term where all members or stakeholders devote sufficient time and there is equity and trust between them (Netshandama, Citation2010). Stakeholders often have differing vested interests. For example, in the street pesticide case, informal vendors are making a profit from selling illegal pesticides; Environmental Health Practitioners are mandated to remove illegal pesticides from markets; academics conduct research highlighting the complexity of the problem presented in peer-reviewed articles and develop interventions, whereas the household members are demanding cheap and effective pesticides.

Through the Alignment, Interest and Influence Matrix (AIIM) tool, key stakeholders are identified, and possible courses of engagement are suggested to ensure cohesion surrounding a project (Mendizabal, Citation2010). For example, when considering informal vendors, whilst alignment might be high, interest might be low and therefore one suggestion based on the AIIM tool would be to run an information session that increases informal vendors’ awareness of the concerns with street pesticides, including their role in poisoning children, as well as the chronic health risks for vendors and community members (Balme et al., Citation2010; Rother, Citation2016). Of course, there are challenges associated with this. For example, informal vendors’ illegal pesticides are often confiscated by officials to protect their, and the community members’ health. Yet, the vendors see this as an infringement on their right to sell, making them not trust officials. The key is for a dialogue, to ensue all parties are communicating and on the same problem-solving page. This is discussed later in this manuscript; however, it is important to ensure that all stakeholders are aware of the dangers of these chemicals before any meaningful and sustainable change could take place to promote collective solution finding.

Fostering a collective dialogue in this case, could be achieved with a knowledge broker that is well-connected and can act as an intermediary between stakeholders (Glegg & Hoens, Citation2016). Knowledge brokers and linking agents play multi-faceted roles and should be considered to participate with the longevity of their involvement ideally extending beyond the initial full cycle of the process to foster future engagement and decision-making (Cvitanovic, McDonald, & Hobday, Citation2016; Reed, Citation2008). In the case of street pesticides, the identification of the role players is quite nuanced, which a knowledgeable and trusted knowledge broker could assist in identifying and navigating. Particularly as stakeholders have differing vested interests in participating in the dialogue or initially resisting to participate. Thus, identifying a relevant knowledge broker from the onset is critical for mobilising the right stakeholders and building relationships of trust. For example, the knowledge broker should establish trust with the informal vendors and speak their language, as well as have the trust of others (e.g. government officials, academics, community members). An example from our case would be a chairman of an informal vendors association within a particular community. The project/dialogue aims, objectives and outcomes should be agreed upon during the initial engagements with all stakeholders. To foster productive solution finding, this needs to be a regular engagement of discussion and trust building.

Co-creation of solutions

Once stakeholders are in discussion with one another in a respectful manner, then the process can focus on the co-creation of solutions through meaningful collaboration and input that is sustained with all stakeholders. For example, co-creation of solutions requires engagement at all levels from the initial co-construction of knowledge on potential methods of alternative pest control, through to the development and selling of these alternatives (e.g. making rat traps that are effective for the size of the rat in the local area or low-toxic pest control recipes that take on board feedback provided to the informal vendor from local residents). Participatory research, including for the co-production of knowledge, supports a strong sense of understanding and ownership of the research or project by stakeholders through active engagement in all aspects (Cvitanovic et al., Citation2016; Reed, Citation2008). The process of engagement should be iterative and encourage two-way learning (Johnson, Lilja, Ashby, & Garcia, Citation2004). Cvitanovic et al. (Citation2016) caution however that this approach, whilst effective, can be resource and financially intensive, and requires institutional support. We argue that the process of engagement has multiple layers of varied stakeholder consultation that need to be integrated for solution seeking. Thus, engagement need not always be simultaneous between stakeholders but that agreement with all stakeholders should occur before putting a project plan into action. For example, engagement with informal vendors might be more intensive and require tentative navigation, which allows time to communicate and understand the risks of street pesticides, compared to engagement with academics and government officials, which might require less time for risk communication.

Co-implementation

For co-created solutions to be implemented successfully, we argue that this also requires collaboration at the implementation stage. During stakeholder dialogues, agreement should be attained on how co-created solutions will be developed, distributed or fostered in their specific capacity. The key is that these strategies support co-implementation that works toward the collective goal rather than undermining efforts; for example, the gradual phasing out of selling street pesticides while selling and obtaining community confidence or demand for low-toxic alternatives.

Co-monitoring and co-evaluation

Netshandama (Citation2010), when commenting on the quality of partnerships from the community stakeholder’s perspective, states that the partnerships themselves should be maintained and monitored, and that the termination of a partnership, ideally, should only occur once all parties feel the need for the partnership has come to an end (Netshandama, Citation2010). Indeed, evaluating the engagement process should also be participatory (Blackstock, Kelly, & Horsey, Citation2007) and therefore participatory action research involves ‘constant feedback loops’ between stakeholders (Nelson, Ochocka, Griffin, & Lord, Citation1998). Partnerships and engagement can be evaluated against the five values of participatory action research: (i) empowerment; (ii) social justice and equity; (iii) supportive relationships and inclusion; (iv) mutual learning and reciprocal education; and (v) respect for diversity and power sharing (Nelson et al., Citation1998; Winkler, Citation2013). In this case, co-monitoring and co-evaluation should also take place surrounding the project aims of risk-reducing and income-earning solutions agreed upon during initial engagement. Certainly, by co-monitoring and co-evaluating the project outcomes, the fourth value of participatory action research is being fulfilled, such that stakeholders are iteratively learning between each other. Reed (Citation2008) asserts that relevant stakeholder participation throughout the entire process including monitoring and evaluating outcomes is best practice for quality decisions that are durable and to avoid stakeholders feeling that they have been invited to engage and contribute once proposals or project designs have been finalised (Chess & Purcell, Citation1999; Estrella & Gaventa, Citation1998). Estrella and Gaventa (Citation1998) broadly categorise participatory monitoring and evaluation into four principles: (i) participation, (ii) learning; (iii) negotiation; and (iv) flexibility. The authors highlight that these might be challenging to implement practically but provide useful stages of participatory monitoring and evaluation, as well as relevant tools and techniques. In the case of engaging with informal vendors, quantifying the four principles and defining these at the beginning of project would need to be agreed upon to evaluate if they have been achieved. The challenge is that vendors are a transient group and so the same vendors may not always participate in all sessions of engagement. In the case of street pesticides where there are diverse stakeholders with differing vested interests, again, a knowledge broker would be key to facilitate co-monitoring and co-evaluation; the outcomes of which are then jointly reflected upon.

Co-reflection

To achieve finding solutions to the use and sale of highly hazardous pesticides in an engaged and iterative manner, reflections on the engagement process need to be sought from all stakeholders. Understanding practices and assumptions with a critical appraisal from all stakeholder’s perspectives is key. The introspective work of Winkler (Citation2013) in analysing their university-community engagement provides critical reflections such as: ‘who benefits from community-university partnerships?’. Winkler (Citation2013) confesses that the community does not always benefit from the engagement as the university does, particularly through achieving their learning objectives, and advocates that shared reflection allows for learning from shared experiences and should improve the quality of future engagements. In the case of street pesticides, the community would benefit from reduced exposures to hazardous pesticides leading to a reduction in poisonings and deaths in some cases. Constant reflection (Netshandama, Citation2010) against the five values of participatory action research (Nelson et al., Citation1998; Winkler, Citation2013) is a recommended form of reflection. We recommend that feedback sessions for discussions and reflections are participated in by all stakeholders, which have the potential to directly impact upon interventions. These could be facilitated by the research team or knowledge broker.

Co-redesign

Co-redesign is a vitally important part of not only the co-solution seeking process, but to make the project sustainable, as it involves stakeholders in actualising reflection, monitoring and evaluation and then acting upon these findings. Co-redesign of the existing project at this stage of the process would ensure the engagement of stakeholders as they had worked on the project to this point. Furthermore, perhaps future projects could be designed during this stage as an outcome of the initial project, which would involve stakeholders right at the onset and allow for joint conceptualisation of any future projects. During co-redesign the discussion would identify the need for new relationships and stakeholders that could be brought into the project to take it into the next phase. Thus, we propose that the process of engaged scholarship needs to be cyclical to allow for integrating new knowledge, stakeholders and changes that might need to be implemented.

Bringing theory into practice

The framework presented in and discussed above is largely theoretical however, one workshop has taken place. This workshop was held in June 2018 with informal vendors (50), academia (2) and local city environmental health officials (8). The workshop was held at a local train station meeting room in the area of a local township where the informal vendors usually sell their products. This workshop was facilitated by the chairman of a local vendors association and was run jointly by local city health officials and the local university academics. The agenda, co-created by city health officials and university academics, included: an opening address by city health officials and the vendors association chairman, with an opening prayer by one of the vendors; an input by university academics to discuss the hazards and risks of street pesticides; a question and answer session; and closed by the vendors association chairman and city health officials. Participants of the workshop engaged with the session, asking many questions throughout about health risks, economic sustainability and the willingness to take the risk to sell alternatives with support.

To begin to understand how street pesticides are viewed by the vendors; when asked what street pesticides are, one vendor referred to the pesticide as a form of medicine. This implies that the vendors might not see this as a hazardous ‘poison’ but rather as a method to remedy pest infestations. When the vendors were asked about the hazards of the street pesticides one vendor mentioned that the pesticide is dangerous to the pest that it kills, which might imply a thinking that the street pesticide is only dangerous for pests, rather than posing a danger to human health over the short- or long-term. This workshop has been a crucial first step towards establishing relationships and beginning to bring those parties to a shared understanding that street pesticides are a danger to health and that there are options for reducing health risks while maintaining income generation.

Whilst this is the only empirical aspect of the framework that the authors are able to report on at this time, the occurrence and engagement process of the workshop is indicative of illustrating that relationships can be established with committed and interested stakeholders. The initial reasons for attending the workshop varied – for example, wanting to understand why products are being confiscated, wanting to sell street pesticides, and wanting to inform vendors of the highly toxic nature of the chemicals and child morbidity and mortality happening in the communities. The theoretical framework proposed has shown in this pilot that it is a feasible guide. Of importance is that for the success of engagement, time and safe dialogue is required acknowledging the fragility of some of the relationships. Furthermore, this framework should be used as a theoretical basis at the onset of engagement, rather than only implementing this process of solution-finding retrospectively after attempting a more traditional, top-down approach.

Challenges associated with engagement

Regarding the case on street pesticide use and further and continued engagement with informal vendors to ensure meaningful and sustainable solutions, many challenges are anticipated, with a few listed below.

Since the informal vendors engage in illegal selling of hazardous products, they might initially be reluctant to participate in research. Again, this is when the role of a knowledge broker becomes important. In the 2018 engagement with vendors, the knowledge broker was the chairman of the vendors association and was successful in facilitating the start of the dialogue. Furthermore, research methods with groups conducting illegal activities, such as using drugs, is often by self-reported, anonymous surveys (Harrison, Citation1997). This research method would be difficult, although not impossible, to achieve in an engaged scholarship approach. Lessler and O’Reilly (Citation1997) provide an overview of reporting on sensitive issues using techniques such as indirect questioning and self-administered, rather than interviewer-administered questionnaires, whereby protection of privacy is met. Using open-ended questions and language that implies the behaviour, such as using drugs, are examples of questionnaire techniques that tend to elicit sensitive information. There are limitations of these techniques, such as requiring a certain level of literacy and as such Lessler and O’Reilly (Citation1997) advocate for the use of computer-assisted self-interviewing (CASI) as well as audio-CASI which allow for tailored questions based on participant’s answers as well as other administrative (e.g. language) and standardisation issues (e.g. questions read aloud). Furthermore, using a human voice and headphones provides a more private environment and personalised interaction for the respondent (Lessler & O’Reilly, Citation1997).

The above-mentioned techniques are useful when obtaining information about sensitive issues, such as reporting to researchers on conducting an illegal activity. Indeed, there will be challenges associated with the practicalities of the physical engagement with informal vendors (Hart et al., Citation2013; Packman et al., Citation2017). These challenges include ensuring there is not a dominance of academics overpowering non-academics as well as providing an appropriate venue; for example, conducting meetings at a university building could reinforce academic knowledge capital and Mode 1 knowledge (Gibbons et al., Citation1994; Hart et al., Citation2013). With the case of street pesticides, it might be necessary to share information at the start of the engagement, similar to what was done in the 2018 engagement with vendors, such that all stakeholders are aware of the public health risks of these hazardous chemicals.

Another challenge associated with engagement might be the difficulty in establishing trusting relationships between informal vendors and government officials particularly. This is primarily because the government officials are the ones usually tasked with confiscating street pesticide stocks during raids (Rother, Citation2016). This has been the government’s approach to dealing with the enormous influx of these products in local markets. Prior to Rother’s initial study in 2008, government officials used to regularly arrest the vendors – predominantly women. Again, we stress that to address this challenge, dialogue is necessary brought about by involving a knowledge broker and to rebuild trust. In the 2018 engagement with some Cape Town vendors, the opportunity was provided to indicate that the products were being confiscated to protect the health of community members, especially children, rather than ‘punish’ the vendors as voiced by one vendor.

It is important that the alternative strategies for household pest control that are low- or non-toxic to humans, be economically viable for informal vendors, so as to remove the allure of economic gain from selling a hazardous substance. This is a process of gaining acceptance for the alternative solutions that might involve some degree of trial and error, testing and community demand. Not all informal vendors are aware of potential alternative remedies, thus emphasising the importance of the co-creation of solutions stage (). Alternatives that are currently available for sale by some informal vendors () have not been through such a process and therefore might not be the best solution for the local area with its unique local challenges. Indeed, the popularity of chemical substances are often due to their effectiveness as a result of many agricultural chemical’s high toxicity (Rother, Citation2010). Furthermore, there is no guarantee that, from a marketing and competition perspective, vendors would not begin adding hazardous chemicals into their alternative remedies to improve effectiveness of the control measure and ultimately improve sales. This again amplifies the need for the initial sharing of information on the hazards of these chemicals as well as co-evaluation and co-redesign. Particularly as engagement needs to leave room for making errors as a collective and not giving up on the project but rather coming up with new solutions in the co-design process.

Conclusion

The cyclical and iterative engaged scholarship framework presented in this manuscript was illustrated through a case of informal vendors selling street pesticides. This framework of engagement, however could and indeed, should be used for other projects for the co-construction of knowledge to develop sustainable public health solutions. Regarding the specific case presented here, whilst we advocate for improving service delivery to low-income areas and banning of hazardous chemicals for domestic use we also seek not to undermine the economic livelihoods of informal vendors. Exploring a relationship with a group conducting illegal activities requires well thought out and tentative navigation to not disrupt the fragility of the potential engagement. This is in an attempt to truly integrate engaged scholarship through diverse interaction and create sustainable solutions that maintain the informal vendors’ economic livelihoods but eliminate the community’s health risks of exposure to hazardous products.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Emeritus Professor Shirley Pendlebury for her valuable advice and leadership. CNG and HAR jointly conceptualised the manuscript and contributed to draft manuscript revisions. The manuscript builds on previous research by HAR. Both authors approved the final manuscript. We would also like to thank the University of Cape Town's Research Office and the Engaged Scholarship Programme who provided funding for a writing retreat in which this work was developed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adamkiewicz, G., Spengler, J. D., Harley, A. E., Stoddard, A., Yang, M., Alvarez-Reeves, M., & Sorensen, G. (2014). Environmental conditions in low-income urban housing: Clustering and associations with self-reported health. American Journal of Public Health, 104(9), 1650–1656. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301253

- Balme, K. H., Roberts, J. C., Glasstone, M., Curling, L., Rother, H., London, L., … Mann, M. D. (2010). Pesticide poisonings at a tertiary children's hospital in South Africa: An increasing problem. Clinical Toxicology, 48(9), 928–934. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2010.534482

- Balme, K., Roberts, J. C., Glasstone, M., Curling, L., & Mann, M. D. (2012). The changing trends of childhood poisoning at a tertiary children's hospital in South Africa. South African Medical Journal, 102(3), 142–146. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.5149

- Barata, M. (2017). Climate change and urban human health. In P. Dhang (Ed.), Climate change impacts on urban pests (pp. 165–173). Cambridge: CAB International.

- Blackstock, K. L., Kelly, G. J., & Horsey, B. L. (2007). Developing and applying a framework to evaluate participatory research for sustainability. Ecological Economics, 60(4), 726–742. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.05.014

- Boxall, A. B., Hardy, A., Beulke, S., Boucard, T., Burgin, L., Falloon, P. D., … Williams, R. J. (2009). Impacts of climate change on indirect human exposure to pathogens and chemicals from agriculture. Environmental Health Perspectives, 117(4), 508–514. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800084

- Boyer, E. L. (1996). The scholarship of engagement. Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 49(7), 18–33. doi: 10.2307/3824459

- Chess, C., & Purcell, K. (1999). Public participation and the environment: Do we know what works? Environmental Science and Technology, 33(16), 2685–2692. doi: 10.1021/es980500g

- Cooper, D. (2017). Concepts of “applied and public sociology”: Arguments for a bigger theoretical picture around the idea of a “university third mission”. Journal of Applied Social Science, 11(2), 141–158. doi: 10.1177/1936724417722580

- Cvitanovic, C., McDonald, J., & Hobday, A. (2016). From science to action: Principles for undertaking environmental research that enables knowledge exchange and evidence-based decision-making. Journal of Environmental Management, 183(3), 864–874. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.09.038

- Estrella, M., & Gaventa, J. (1998). Who counts reality? Participatory monitoring and evaluation: A literature review (Institute of Development Studies Working Paper 70).

- Gibbons, M., Limoges, C., Nowotny, H., Schwartzman, S., Scott, P., & Trow, M. (1994). The new production of knowledge: The dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies. Stockholm: Sage.

- Glegg, S. M., & Hoens, A. (2016). Role domains of knowledge brokering: A model for the health care setting. Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy, 40(2), 115–123. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0000000000000122

- Gubler, D. J., Reiter, P., Ebi, K. L., Yap, W., Nasci, R., & Patz, J. A. (2001). Climate variability and change in the United States: Potential impacts on vector- and rodent-borne diseases. Environmental Health Perspectives, 109(Suppl. 2), 223–233. doi:10.1289/ehp.109-1240669. sc271_5_1835 [pii].

- Harrison, L. (1997). The validity of self-reported drug use in survey research: An overview and critique of research methods. In L. Harrison & A. Hughes (Eds.), National Institute on Drug Abuse research monograph, 167 of 1997 (pp. 17–36). Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health.

- Harrus, S., & Baneth, G. (2005). Drivers for the emergence and re-emergence of vector-borne protozoal and bacterial diseases. International Journal for Parasitology, 35(11), 1309–1318. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.06.005

- Hart, A., Davies, C., Aumann, K., Wenger, E., Aranda, K., Heaver, B., & Wolff, D. (2013). Mobilising knowledge in community – university partnerships: What does a community of practice approach contribute? Contemporary Social Science, 8(3), 278–291. doi: 10.1080/21582041.2013.767470

- Hunter, P. (2003). Climate change and waterborne and vector-borne disease. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 94(s1), 37–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.94.s1.5.x

- Ibitayo, O. (2016, September). Reducing agricultural pesticide poisoning in Sub-Saharan Africa: Beyond zero-risk. In Environmental Toxicology and Ecological Risk Assessment. Symposium conducted at the 5th International Conference on Environmental Toxicology and Ecological Risk Assessment, Phoenix, AZ.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2014). Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part A: global and sectoral aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (1132 pp). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Johnson, N., Lilja, N., Ashby, J. A., & Garcia, J. A. (2004). The practice of participatory research and gender analysis in natural resource management. Natural Resources Forum, 28(3), 189–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-8947.2004.00088.x

- Lessler, J. T., & O'Reilly, J. M. (1997). Mode of interview and reporting of sensitive issues: design and implementation of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing. NIDA Res Monogr, 167(366), 382.

- Mendizabal, E. (2010). The alignment, interest and influence matrix (AIIM). London: ODI.

- Nelson, G., Ochocka, J., Griffin, K., & Lord, J. (1998). “Nothing about me, without me”: Participatory action research with self-help/mutual aid organizations for psychiatric consumer/survivors. American Journal of Community Psychology, 26(6), 881–912. doi: 10.1023/A:1022298129812

- Netshandama, V. (2010). Quality partnerships: The community stakeholders’ view. Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement, 3, 70–87. doi: 10.5130/ijcre.v3i0.1541

- Packman, C., Rutt, L., & Williams, G. (2017). The value of experts, the importance of partners, and the worth of the people in between. Participations: Journal of Audience & Reception Studies, 14(1), 376–386.

- Reed, M. S. (2008). Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biological Conservation, 141(10), 2417–2431. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2008.07.014

- Rother, H. (2010). Falling through the regulatory cracks: Street selling of pesticides and poisoning among urban youth in South Africa. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health, 16(2), 183–194. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2010.16.2.183

- Rother, H. (2016). Pesticide vendors in the informal sector: Trading health for income. New Solutions: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy, 26(2), 241–252. doi: 10.1177/1048291116651750

- Shuman, E. K. (2010). Global climate change and infectious diseases. New England Journal of Medicine, 362(12), 1061–1063. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0912931

- Swartz, A., Levine, S., Rother, H. A., & Langerman, F. (2018). Toxic layering through three disciplinary lenses: Childhood poisoning and street pesticide use in Cape Town, South Africa. Medical Humanities, 44, 247–252. doi: 10.1136/medhum-2018-011488

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2019). Paper commissioned for the Global Education Monitoring Report 2019 consultation on migration.

- University of Cape Town. (2012). Social responsiveness policy framework. UCT Senate. Retrieved http://www.socialresponsiveness.uct.ac.za/conceptual-framework-social-responsiveness

- Winkler, T. (2013). At the coalface: Community–university engagements and planning education. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 33(2), 215–227. doi: 10.1177/0739456X12474312

- Zell, R. (2004). Global climate change and the emergence/re-emergence of infectious diseases. International Journal of Medical Microbiology Supplements, 293, 16–26. doi: 10.1016/S1433-1128(04)80005-6

- Zinyemba, C., Archer, E., & Rother, H. A. (2018). Climate variability, perceptions and political ecology: Factors influencing changes in pesticide use over 30 years by Zimbabwean smallholder cotton producers. PloS One, 13(5), e0196901. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196901