ABSTRACT

In Bangladesh, one in five currently married women (CMW) presently experience male intimate partner physical violence (MIPPV). While previous studies analysed women’s individual-level multiple locations–younger age, lower education, income, and poverty in an additive manner, we took an intersectional approach to look at the effects of their multiple intersectional locations on MIPPV. Using McCall’s intercategorical intersectional approach, we examine how women’s intersectional locations are associated with their odds of experiencing MIPPV. Our sample from a 2015 nationally representative survey comprised 14,557 CMW living with their spouses. Thirty-four percent of CMW are young, 49% below primary educated, 19% income earning, 23% poor, and 25% experience MIPPV. We found that CMW in their dual disadvantaged younger age–lower education and single disadvantaged higher education–poor locations have 13.57% (95% CI, 9.25, 17.89) and 12.02% (95% CI, 6.87, 17.17) (respectively) higher probabilities of experiencing MIPPV than their counterparts in the corresponding dual privileged older age–higher education and higher education–nonpoor locations. Consistent with intersectionality theory, instead of prioritising a few groups over others (i.e. Oppression Olympics), we recommend building intersectional solidarity with women, men and communities to disrupt the underlying socio-economic-educational-legal-political structures and processes that have sustained these marginalised locations.

Introduction

Intimate partner violence is the most commonly occurring violence against women around the globe (Devries et al., Citation2013) and particularly in Bangladesh (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics [BBS], Citation2016). While one in three women in the world experience physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence during their lifetime (Devries et al., Citation2013), the prevalence rates of male intimate partner physical violence (MIPPV) against married women in Bangladesh are even higher: one in two, in their lifetime; one in five, in the present time (i.e. in the past 12 months; BBS, Citation2016). The health consequences of such violence are severe not only for women, but also for their children, families, societies and the generations that follow (Campbell, Citation2002; Ehrensaft et al., Citation2003). Considering violence against women a critical, global public health issue (Devries et al., Citation2013), the world leaders have agreed to eliminate intimate partner violence against women in the sustainable development goal (SDG) 5.2 (United Nations, Citation2015). Bangladesh is also committed to achieve this SDG by the year 2030 (Government of Bangladesh, Citation2017b).

Although most Bangladeshi reproductive age women (73% of the 15–49 years old) are married (United Nations Statistics Division, Citation2018), currently married women (CMW) in this country are not monolithic. They occupy various locations in terms of their age, education, income, and poverty; and sometimes, these locations intersect with each other. However, the new World Health Organization (WHO) violence prevention information system (Burrows et al., Citation2018) indicates that women’s multiple locations and MIPPV are examined mostly in an additive manner. In Bangladesh, CMW’s individual-level locations of younger age (Naved & Persson, Citation2005; Sambisa, Angeles, Lance, Naved, & Thornton, Citation2011), lower education (Bates, Schuler, Islam, & Islam, Citation2004; Dalal, Rahman, & Jansson, Citation2009), income (Bates et al., Citation2004; Naved & Persson, Citation2005) and household poverty (Bates et al., Citation2004; Sambisa et al., Citation2011) have been found to be positively associated with MIPPV. Encouragingly, these studies have examined these multiple locations, but they have been considered in a mutually exclusive way so that they do not overlap with each other. For example, they examined whether CMW’s younger age or lower levels of education are risk factors for MIPPV. As a result, CMW who simultaneously occupy multiple locations (e.g. younger age–lower education) are invisible and their experiences remain unknown. Therefore, to expand what we know, our study took an intercategorical intersectional lens (Crenshaw, Citation1998; McCall, Citation2005). We examined Bangladeshi CMW’s present MIPPV experiences in the past 12 months with respect to their individual-level, dual intersectional locations in combinations of their age, education, individual income, and poverty (e.g. whether women at dual disadvantaged locations such as younger age–lower education are more likely to experience MIPPV than their counterparts in dual advantaged older age–higher education location, Supplementary Table 1).

Intersectionality theory

Intersectionality theory, one of the most important feminist theories (McCall, Citation2005), provides a lens to examine individuals’ experiences of privilege, oppression and resistance across their intersecting identities and locations, and interrogate the structures and processes that produce these identities and locations (Crenshaw, Citation1998; McCall, Citation2005). It allows the invisible individuals and groups that are in multiple intersecting disadvantaged locations (e.g. race–gender) to the centre. Crenshaw (Citation1998), who coined the term–intersectionality, provided a lucid example of an invisible group of black-women, and showed how they were treated either as black men or white women (which were dominant minority sub-groups within the categories of race and gender) despite having their own unique discrimination experiences. Although group membership to multiple disadvantaged intersectional locations (e.g. black-women) are often considered as marginalised locations (Warner, Citation2008), intersectionality theory does not give primacy to one location over another, i.e. this theory considers all categories equal (Hancock, Citation2007). As Bangladeshi CMW are located in various intersectional locations, yet the relationships between these locations and MIPPV are unknown, this theory is appropriate to examine the relationship between these marginalised locations and MIPPV.

Intercategorical intersectional approach

To advance intersectional research using the existing categories, McCall (Citation2005) defined an intercategorical intersectional approach. This approach (McCall, Citation2005) allows quantitative analysis of the complex relationships between multiple dimensions of already existing categories of identities and locations, which are often used interchangeably. However, instead of the term ‘identities’ that are one’s personally held belief about the self (Bauer, Citation2014), we have used the term ‘locations’ (in other words, ‘positions’) because these are ‘indicated either by objective measure (e.g. income or wealth) or the way one is perceived and treated by others’ (Bauer, Citation2014, p. 13). As Bangladeshi CMW’s age, education, income, and poverty are already well-known primary marginalised locations (Bates et al., Citation2004; Sambisa et al., Citation2011), an intercategorical approach provides a powerful tool to look at the intersections of these locations. Such analysis makes invisible intersectional locations visible, and most importantly, it draws attention to the structures and processes that have generated these locations (Kelly, Citation2011).

This approach is useful when it is plausible for Bangladeshi CMW to belong to multiple interactive locations; and to have unique MIPPV experiences that are separate from that of the women in each of these primary locations alone. For example, a younger married woman with a lower-level of education belongs to two marginalised groups: younger age and lower education. Although she may have some experiences like members of either of these groups, she may still have experiences that are completely different from them. In Bangladesh, women married young are more likely to have lower education and belong to poorer households (BBS, Citation2015b). This, in turn, may hinder their ability to enhance personal capabilities and get access to better employment opportunities (Boyle, Georgiades, Cullen, & Racine, Citation2009). Younger, 15–29 years old, income-earning women are more likely doing precarious, informal work that neither provides basic social or legal protections nor employment benefits as compared to their 30–64 years old counterparts (BBS, Citation2015a). Thus, earning an income may not automatically render women a higher social status. Therefore, instead of looking at CMW’s younger age, lower education, income and poverty locations in isolation, it is useful to know whether women located at disadvantaged co-locations are more likely to experience MIPPV.

Using the lenses of intersectionality theory (Crenshaw, Citation1998) and an intercategorical intersectional approach (McCall, Citation2005), we have asked the following question: In Bangladesh, how are the CMW’s intersecting dual locations in combinations of younger age, lower education, income, and household poverty associated with their odds of experiencing MIPPV? Answering this question will make CMW’s various intersectional locations that increase their odds of MIPPV visible. Next, the structures and processes that produce and sustain these locations can be examined to reduce MIPPV against women in Bangladesh.

Materials and methods

Sample

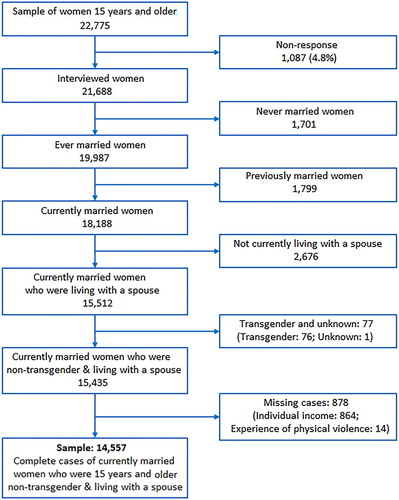

We have used the nationally representative, cross-sectional Bangladesh Violence against Women Survey 2015 (BVAWS2015) dataset (BBS, Citation2016) (Supplementary Appendix 1). The survey employed a two-stage stratified sample of private dwelling households from all the then seven divisions and 911 primary sampling units (PSUs) with 21,688 women of 15 years and older. Details of the survey design and methods have been described elsewhere (BBS, Citation2016). Our study sample includes 14,557 currently married, 15 years and older, non-transgendered women who were living with a spouse during the survey administration (). Thus, our CMW sample is more restrictive than that in the BVAWS2015 survey report.

Ethical issues

BVAWS2015 followed the ethical and safety guidelines of the United Nations Statistics Division (BBS, Citation2016); and we received ethics review exemption at the University of Toronto because we were conducting de-identified secondary data analysis.

Measures

Outcome variable

MIPPV, the outcome variable, measures whether a woman has presently (i.e. in the past 12 months) experienced any physical violent acts by her male intimate partner. The modified Conflict Tactics Scale 2 (CTS2) (Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, Citation1996) measured MIPPV. This scale has been used worldwide (Devries et al., Citation2013) and in Bangladesh (National Institute of Population Research & Training, Mitra and Associates, & ICF International, Citation2009). The scale included 10 items (BBS, Citation2016) (Supplementary Table 2).

Independent variables

Four primary independent variables included CMW’s younger age, lower education, income and household poverty. To manage computational and analytical complexities, these variables were dichotomised. The first three variables were derived from survey questions on women’s age, education, and whether they earned an income while the fourth was generated from the BBS provided household wealth quintile values (Supplementary Table 2). Younger women variable was generated by coding women who were 15–29 years old during the survey as 1 and if otherwise, 0. Lower education variable was generated by coding respondents who reported no education or below primary-level of education as 1 and if otherwise, 0. These cut-off points were selected based on recent literature. Although ‘age group of 15–19’ and ‘no education’ were used as reference categories in an earlier report (Koenig, Ahmed, Hossain, & Mozumder, Citation2003), more recent work suggests that the protective effect of age on MIPPV starts older than 30 years (Sambisa et al., Citation2011). As well, some primary-level of education no longer confers additional benefit over having no education (Sambisa et al., Citation2011). Thus, in this paper, although higher education would generally connote secondary- or graduate-level schooling, given that, about half of the CMW in our population had no or below primary-level education, women with primary or greater than fifth-grade education were coded as higher educated women. The income variable was created by coding respondents reporting earning an income in the past year as 1 and if otherwise, 0. The household poverty variable was created by coding women who had a wealth quintile value of 1 (i.e. the poorest quintile or the bottom 20%) as 1 and if otherwise, 0. This level was categorised as poverty in accordance with other MIPPV literature (Ismayilova, Citation2015).

Control variables

Husband’s younger age, his lower education, woman’s religion and geographical location were initially considered as potential confounders based upon their theoretical relationships to the exposures and outcomes and thus their epidemiologic importance. Although these variables are associated with above mentioned independent variables, they are not an effect of them, while they are risk factors for MIPPV (Fulu, Jewkes, Roselli, & Garcia-Moreno, Citation2013; Koenig et al., Citation2003; Naved, Citation2008; Sambisa et al., Citation2011). We assessed the presence of actual confounding during our statistical modelling (i.e. whether the effect of the exposure variables changed by <=10%) using the Karlson Holm Breen (KHB) method (Kohler, Karlson, & Holm, Citation2011). We removed woman’s religion and geographical location when confounding was not detected. We did this to keep our models parsimonious given statistical power considerations.

Statistical analyses

Cronbach’s alpha for MIPPV items was 0.71, indicating adequate reliability (Cortina, Citation1993). Income and MIPPV variables had 864 and 14 missing cases, respectively (). But as the missingness in income did not vary across outcome and other independent variables, complete case analyses were carried out (Allison, Citation2002). Univariate analyses described outcome and independent variables and, bi-variate analyses, the association between independent and outcome variables. These analyses accounted for complex survey weights (Supplementary Appendix 2) (StataCorp, Citation2017b). Because women were nested within PSUs; and as nesting explained 16.98% variance, we conducted multilevel analyses (Level-1: individuals; Level-2: communities/PSUs).

Before measuring the effects of various intersectional locations, a 2-level fixed-effect binary logistic regression model (Liu, Citation2016) analysed the association between women’s four primary individual-level locations (age, education, income, and poverty) and MIPPV. Next, the cross-product terms of six possible combinations of two-way interactions between the four primary variables were used in six 2-level fixed-effect binary logistic regression models (Supplementary Appendix 3). These models tested the association between women’s each of the six individual-level dual locations and MIPPV. The final model included all intersectional locations.

As odds ratios for the interaction terms represent ratios of odds ratios, we generated interaction plots to interpret the significant interaction terms. While there were 24 intersectional locations (Supplementary Table 1, Panel 1), only locations related to the significant cross-product terms (Supplementary Table 3, Model 7) were further analysed for pairwise comparisons across CMW’s different intersectional locations (Supplementary Table 1, Panel 2). We decided not to compare across all the 24 locations to avoid data dredging and multiple comparisons. Stata 15.1 was used for all analyses (StataCorp, Citation2017a). Procedure melogit with household weights and scaled sample weights of individual women (Rabe-Hesketh & Skrondal, Citation2006) were used to run models (Supplementary Appendices 2 & 3). Margins procedure with mcompare option calculated women’s odds of experiencing MIPPV and pwcompare with Bonferroni adjustments was used to compare women’s vulnerable and privileged locations. Stata codes for the final model and pairwise comparisons will be made available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Results

CMW’s characteristics and MIPPV

Over one-third (34.1%) of CMW, living with their husbands, are 15–29 years old; almost half (49.2%) have below fifth-grade education; about one-fifth (19.1%) earns an income; and 23% live in poverty (). One-quarter (25.1%) of the CMW report to have experienced MIPPV in the past year (). Bi-variate analyses indicate that CMW’s locations of younger age, lower education, and poverty are associated with MIPPV (). The main-effect multilevel logistic regression model that included the four primary locations suggests similar findings (not shown).

Table 1. Characteristics of the currently married women (CMW) across their present experiences of male intimate partner physical violence (MIPPV) in Bangladesh.

CMW’s intersectional dual locations and MIPPV

Interaction on the effects of MIPPV between younger age and lower education, and lower education and poverty are significant (Supplementary Table 3, Models 1, 5 & 7). In addition, interaction between income and poverty on MIPPV has approached significance at (p < .10).

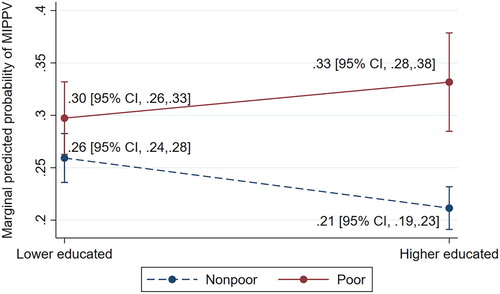

Intersectional locations of age and education

Comparison of marginal predicted probabilities indicate that women occupying dual disadvantaged intersectional location (younger age–lower education) have 13.57% (95% CI, 9.25, 17.89) higher probability of experiencing MIPPV than their counterparts in the corresponding dual privileged older age–higher education location (, Panel-I: A vs. D; ). They also have 8.56% (95% CI, 3.98, 13.14) and 9.64% (95% CI, 5.43, 13.84) higher probabilities of MIPPV than their counterparts in younger age–higher education and older age–lower education locations (respectively) (, Panel-I: A vs. B; A vs. C).

Figure 2. Currently married women’s predicted probability of presently experiencing male intimate partner physical violence (MIPPV) across their levels of education and age groups in Bangladesh.

Table 2. Currently married women’s marginal predicted probability of presently experiencing male intimate partner physical violence (MIPPV) across their dual locations in Bangladesh.

Interestingly, there is no significant difference between younger age–higher education and older age–lower education locations (, Panel-I: B vs. C), while CMW in the former location have higher probability of MIPPV than those in the older age–higher education location (, Panel-I: B vs. D). Lastly, women in older age–lower education location are also more likely to experience MIPPV than their counterparts in older age–higher education location (, Panel-I: C vs. D).

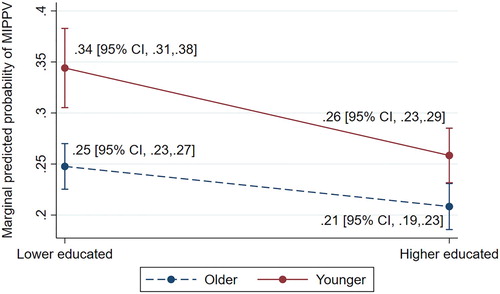

Intersectional locations of education and poverty

Remarkably, higher education–poor is the most marginalised intersectional location because women in this location have the highest predicted probability of MIPPV among all the four intersectional locations. CMW in this location are 12.02% (95% CI, 6.87, 17.17) more likely to experience MIPPV than their counterparts in the most privileged higher education–nonpoor location (, Panel-II: C vs. D, ). Women in dual-disadvantaged lower education–poor location have 8.59% (95% CI, 4.72, 12.46) higher probability of experiencing MIPPV than their counterparts in dual privileged higher education–nonpoor location (, Panel-II: A vs. D, ). However, MIPPV probability is not significantly different for lower educated–poor from that of lower educated–nonpoor and higher educated–poor women (, Panel-II: A vs. B; A vs. C). Interestingly, lower educated–nonpoor CMW are 7.24% (95% CI, −12.47, −2.00) less likely to experience MIPPV than higher educated–poor women (, Panel-II: B vs. C). On the other hand, lower educated–nonpoor women are 4.78% (95% CI, 2.04, 7.51) more likely to experience MIPPV than their higher educated–nonpoor counterparts (, Panel-II: B vs. D).

Discussion

Using an intercategorical intersectional approach (McCall, Citation2005), we have examined how Bangladeshi CMW’s intersectional locations of age, education, income, and poverty shape their odds of experiencing MIPPV. Overall, our findings demonstrate that multiple social locations interact to affect women’s exposure to MIPPV. It is worthwhile noting that the MIPPV prevalence rate is somewhat higher in our study than that reported in the BVAWS2015 study (BBS, Citation2016) – 25.1% vs. 20.5%. This is because our sample includes only the CMW who were living with their spouses during the survey while the BVAWS2015 included all the CMW. We excluded CMW who were not living with their spouses because they would be less likely to experience MIPPV due to less exposure (Chin, Citation2012).

Our analyses of different locations in age and education intersection indicates that younger age is a risk factor for both younger age–lower educated and younger age–higher educated women compared to that of older age–lower educated and older age–higher educated women, respectively. Higher education, in contrast, is a protective factor for both younger age–higher educated and older age–higher educated women when compared to younger age–lower educated and older age–lower educated counterparts, respectively. We found a negative effect of younger age and positive effect of higher education on MIPPV which aligns with additive analyses of data from Bangladesh, Bolivia, Dominican Republic, Egypt, India, Moldova, Rwanda, and Zimbabwe (Ackerson, Kawachi, Barbeau, & Subramanian, Citation2008; Hadi, Citation2005; Hindin, Kishor, & Ansara, Citation2008). Our study, however, shows that younger age–lower educated women are most likely to suffer MIPPV. Interestingly, the benefit of higher education gets muted when younger age–higher educated CMW’s probability of MIPPV experience is compared with that of their older age–lower educated counterparts. Thus, younger women, even when they are higher educated, are not able to occupy a better position in the family than that of their older yet less-educated counterparts. This is not surprising in the context of the hierarchically organised and patriarchal Bangladeshi marital institution. Still rife with child marriage, this system has historically rendered the lower status to younger CMW within the family hierarchy (Amin, Khan, Rahman, & Naved, Citation2013). In a classic patriarchal and patrilocal marital institution, women married young move to their husband’s home which is usually headed by their husband’s father (Kandiyoti, Citation1988). In such a household, younger CMW is not only subordinate to men, but also to senior women in the family; despite education levels, at the bottom of the rung, they are more vulnerable to MIPPV. However, a recent qualitative study, conducted in four Bangladeshi villages where MIPPV is declining, revealed that younger CMW, when educated and employed, no longer occupy a lower status than older women in the family (Schuler, Lenzi, Nazneen, & Bates, Citation2013).

Analysis of the education and poverty intersection indicates somewhat different patterns. Curiously, higher education appears to contribute to higher probability of MIPPV for higher educated–poor women as compared to their higher educated–nonpoor counterparts; and it provides them no additional protection as compared to lower educated–poor CMW. In other words, although higher education reduces the odds of MIPPV among the nonpoor women, it does not for the poor CMW. Remarkably, higher-education renders the poor CMW at higher odds of violence than higher educated–nonpoor women.

This may be because historically, women in Bangladesh lagged in education, but encouragingly the country achieved gender parity in primary- and secondary-level education (Chisamya, DeJaeghere, Kendall, & Khan, Citation2012). However, this gender parity in education, unfortunately, has not rendered a concomitant change in women’s higher quality of education, employment opportunity, upward social mobility, and gender relations at home (Chisamya et al., Citation2012; Del Franco, Citation2010). It is, therefore, possible that when higher education fails to generate an upward mobility and higher status for women, it fails to be a protective factor against violence.

It is noteworthy that higher education enhances the odds of MIPPV for the higher educated–poor women as compared to both lower educated–nonpoor and higher educated–nonpoor women. Previous literature indicates that higher education might make women more assertive in realising their rights, rendering them higher bargaining power (Bates et al., Citation2004) and greater ability to resolve conflicts by speaking ‘tactfully and strategically’ (Schuler et al., Citation2013, p. 254). However, if men in poor households, which are fertile ground for conflict over limited resources, feel threatened by women’s power, then they may resort to backlash and violence (Chin, Citation2012). Women in the beginning stages of empowerment may also not have the necessary resources to fend off violence (Schuler et al., Citation2013).

Taken together, CMW in dual disadvantaged younger age–lower education and single disadvantaged higher education–poor locations are most vulnerable to MIPPV. To reduce MIPPV against women in these locations, an intersectional lens would require us to unpack the underlying structures and processes that produce and sustain these locations.

Women’s locations at the intersections of age–education and education–poverty can be traced to the patriarchal socio-economic-educational-legal-political structures that permeate women’s lives from the national to the regional and community levels, ultimately affecting CMW’s familial relations, their intersecting locations and MIPPV. Patriarchal marriage institutions are founded on gender discriminatory religious and social codes that promote early marriage and dowry practices. Such practices as discriminatory inheritance and family laws support hierarchical family structures maintaining CMW’s subordinate family status (Kandiyoti, Citation1988; Pereira, Citation2002). Additionally, they maintain the lower status to younger than older married women; and condone violence against women and girls (Amin et al., Citation2013; Naved & Persson, Citation2005). Although Bangladesh introduced harsher deterrent against child marriage in its Child Marriage Restraint Act 2017 (Government of Bangladesh, Citation2017a), it, unfortunately, still allows child marriage in special circumstances. Bangladeshi Penal Code 1860 even allows corporal punishment of children at home (Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children, Citation2018), and the government continues to hold reservation against the Convention on Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) Articles 2 and 16.1 (c) which are core components to achieve gender equality and ensure equality in marriage (United Nations, Citation2011). Thus, the current laws fall short to protect CMW sufficiently from these social practices and leave CMW, especially the younger ones, in a precarious position.

Acknowledging the above vulnerabilities, government has worked to keep girls in school and thus delay early marriage by making education free (Amin, Asadullah, Hossain, & Wahhaj, Citation2017). However, given that dowry payment increases with age (Amin & Huq, Citation2008), and marrying off girls is considered a key parental responsibility, some parents put off marriage only to be able to accumulate dowry payment or find an eligible suitor (Del Franco, Citation2010). Thus, despite free education, younger CMW are still likely to remain lower educated. Consequently, the younger age–lower educated CMW continue to find themselves at the lowest level of the family hierarchy with higher odds of experiencing MIPPV. Thus, despite the government’s investment in free education, this has not automatically translated into gender equality in families. Education is necessary; however, what girls get is insufficient to raise their status and stop child marriage (Amin et al., Citation2017).

Further, given the current school curricula neither challenge the patriarchal norms nor are linked to skills training and earning opportunities, they do not help girls effectively challenge gender norms. They do not give girls the perceived opportunity to exit marriage by gaining normative empowerment (Schuler & Nazneen, Citation2018). Thus, the content and implicit biases in the education system needs to change for inequalities to change. Women need to gain normative empowerment so they, men and Bangladeshi society will view women’s empowerment as normal which in turn, might reduce the patriarchal constraints on women and male backlash.

In addition to the unfortunate relation between marriage and educational systems, the economic, legal, and political systems also put constraints in gender relations. These systems, therefore, must be reformed to ensure gender equality in both public and private spheres. In the economic sphere, government needs to accelerate the pace of bringing women into the labour force, ensure equal pay and take steps to provide women with necessary training to take up higher positions in the public and private institutions (Bangladesh Planning Commission, Citation2015). Although millions of women have access to micro-credits, women more generally need to gain adequate access to credit and ownership of assets (Bangladesh Planning Commission, Citation2015). Discriminatory inheritance laws, among other things, leads to a paucity of women’s wealth and creditability in the market. Therefore, in the legal front, full implementation of CEDAW is long overdue. Introducing the Domestic Violence (Prevention and Protection) Act 2010 (DVPPA2010) has been a step in the right direction, unfortunately, awareness of this law and its implementation remain inadequate (Huda, Citation2016). In the political sphere, Bangladesh has recently ranked top 5 in the world in reducing the gender gap in politics (World Economic Forum, Citation2018), but women are vastly unrepresented in the local government (Hossain, Citation2015) and, local government leaders, who are expected to help women who have suffered MIPPV, lack awareness on DVPPA2010 (Huda, Citation2016).

Based on our findings, it might be worth considering methods for disrupting women’s vulnerable MIPPV intersectional locations by undertaking specific programme and policy interventions. First, younger age–lower educated CMW need to have opportunities not only for education, but also skills training, and employment. These will help CMW achieve higher empowerment levels and stronger sense of rights and status in the family. These in turn will enable CMW to escape their younger age–lower education location. Child marriage must be stopped so that women are not pushed into this location in the first place. Likewise, higher educated–poor women need to receive skills training coupled with earning opportunities, so they may leave the location of poverty. Positively, the Bangladeshi National Women Development Policy aims to mobilise the ‘poor women to increase their skills and create … alternative socio-economic opportunities through giving them training’ (Government of Bangladesh, Citation2011, p. 18). However, these opportunities have not been adequately coupled with the government’s initiatives against MIPPV. Violence against women programmes also need to reach out to the men in the communities to help them foster positive, non-violent masculinity and gender-equitable social norms (Jewkes, Flood, & Lang, Citation2015). Encouragingly, a study in Bangladesh found positive effect of working with women and men in the communities towards reducing MIPPV (Naved, Al Mamun, Mourin, & Parvin, Citation2018).

By acknowledging violence against women as a challenge, Bangladesh has been rightly committed to SDG 5.2 (Government of Bangladesh, Citation2017b) and it now ranks top in South Asia in gender equality (World Economic Forum, Citation2018). The country, therefore, has adopted strategies against violence mentioned above through a National Action Plan including a multi-sectoral, violence against women programme (Bangladesh Planning Commission, Citation2015). This programme, in collaboration with non-government organisations and women’s groups, largely focuses on secondary- and tertiary-level preventions, offering access to help-line, one-stop crisis centres, medico-legal services and rehabilitation programmes to MIPPV survivors (Government of Bangladesh, Citation2017b). Sadly, these services remain largely inadequate (Huda, Citation2016) and most women do not know about them (BBS, Citation2016). Thus, fewer than 30% of Bangladeshi women disclose their experiences of violence and only 2.6% take legal action (BBS, Citation2016). Two in five women (39%) do not consider reporting; and more than one in four women attach shame related stigma with such disclosure (BBS, Citation2016). It is, therefore, critical to inform women about these services. Given the high prevalence of violence, information about DVPPA2010 and relevant service-related information should be incorporated in the formal and informal education curricula as well as disseminated through mass media. Most importantly, stigma around MIPPV needs to be dispelled so survivors will speak up and make use of these services.

Thus far, primary prevention of violence against women has been limited to advocacy activities (Al Mamun et al., Citation2018; Amin, Rahman, Hossain, & Naved, Citation2012) with the focus on changing attitudes and correcting inequitable gender norms. Now, our study points to the importance of making additional primary prevention investments such as opportunities for CMW to receive higher education, skills development and employment programmes towards achieving normative empowerment. When women’s empowerment is viewed as normal, they remain surrounded by other women, men and community members who do not tolerate MIPPV and they instantly come to help survivors when such violence occurs (Schuler & Nazneen, Citation2018). Thus, building intersectional solidarity with women at different intersectional locations and different actors may take shape by making structural changes not only to the economic, legal and political systems, but also to the wider society to ultimately achieve gender equality and stop MIPPV against women.

Strengths and limitations

We believe, this is the first study to employ McCall’s (Citation2005) quantitative intercategorical intersectional approach to examine Bangladeshi CMW’s MIPPV. Second, analysing the latest, nationally representative dataset has allowed us to gain insights into the Bangladeshi national rather than just the regional/local-level MIPPV phenomenon. Third, unlike other surveys, this is the first study that has included Bangladeshi women 49 years and older. Inclusion of these women is important, as elderly abuse has become a global public health problem (Dong, Citation2015). Finally, we have used multilevel models to account for women’s nested locations and survey weights to account for the complex survey design.

This study has several limitations. Ideally, an intersectional research would consider women’s multilevel locations. However, in our discussion, we have identified national-level institutions and structures that perpetuate women’s disadvantaged locations. Our next projects will be built on this study to examine women’s (1) triple intersectional locations, especially the intersecting locations of younger age–lower education–poverty and (2) community-level locations. Examining the effects of other locations such as ethnicity, disability, non-heterosexual and dating relationships, and slums (Hadi, Citation2011; Hasan, Muhaddes, Camellia, Selim, & Rashid, Citation2014; Kelly, Citation2011; Rashid, Citation2006) are important, but it is beyond the scope of this study. With a cross-sectional design, we have examined only the association between women’s different intersectional locations and MIPPV, not the causality. Finally, a qualitative inquiry could be a logical next step to make this study findings firmly grounded on Bangladeshi women’s day-to-day lived MIPPV experiences (Yuval-Davis, Citation2011).

Implications and conclusion

We have used a quantitative intersectional lens with a critical awareness of Bangladeshi gender inequalities and systems of oppression to enhance the intersectional MIPPV research scholarship. Our study makes women’s various intersectional locations, particularly their younger age–lower education and higher education–poverty locations visible. As would be expected in an intersectional research, women’s education shows a complicated, interactive relationship with their age and poverty statuses. The protective effect of higher education gets attenuated for both younger age and poor women. Therefore, investing in education is absolutely necessary but not enough (Amin et al., Citation2017).

Policy-makers and programme managers need to partner with CMW to find innovative solutions to enable them to get meaningful education and skills training that might enhance their capabilities to get out of poverty and avoid getting married at a young age. Multi-sectoral socio-economic-educational-legal-political collaboration with women, men and communities are pivotal to empower women and put an end to MIPPV. In consistent with intersectionality theory, instead of prioritising a few marginalised groups over others in an Oppression Olympics (Martinez, 1993, as cited in Hancock, Citation2007), we recommend building intersectional solidarity among the women, men, the communities and multi-sectoral actors to challenge and transform the underlying structures and processes that create and sustain these disadvantaged location.

RGPH-2019-0139-Supplementary_Materials_LR.docx

Download MS Word (44.9 KB)Acknowledgements

LR acknowledges the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics for allowing access to the dataset; Md. Karamat Ali and Tahid Islam deserve special thanks for sharing their insights into the survey. LR is grateful to Dr Robin Mason, the discussant, and participants of the collaborative specialisation in women’s health (CSWH) seminar held at the Women’s College Hospital, Toronto, Canada for their critiques of this study. JDM’s work is supported in part by the Atkinson Foundation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

Data that support the findings of this study are subset of Bangladesh Violence against Women Survey 2015 dataset. These data are available from the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under licence for this study.

ORCID

Laila Rahman http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8117-8481

Janice Du Mont http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4851-1104

Patricia O’Campo http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4549-7324

Gillian Einstein http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0770-5471

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ackerson, L. K., Kawachi, I., Barbeau, E. M., & Subramanian, S. V. (2008). Effects of individual and proximate educational context on intimate partner violence: A population-based study of women in India. American Journal of Public Health, 98(3), 507–514. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113738

- Allison, P. D. (2002). Missing data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Al Mamun, M., Parvin, K., Yu, M., Wan, J., Willan, S., Gibbs, A., … Naved, R. T. (2018). The HERrespect intervention to address violence against female garment workers in Bangladesh: Study protocol for a quasi-experimental trial. BMC PUBLIC HEALTH, 18(1), 512. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5442-5

- Amin, S., Asadullah, M. N., Hossain, S., & Wahhaj, Z. (2017). Eradicating child marriage in the commonwealth: Is investment in girls’ education sufficient? The Round Table, 106(2), 221–223. doi: 10.1080/00358533.2017.1299461

- Amin, S., & Huq, L. (2008). Marriage considerations in sending girls to school in Bangladesh: Some qualitative evidence. Dhaka: Population Council.

- Amin, S., Khan, T. F., Rahman, L., & Naved, R. T. (2013). Mapping violence against women in Bangladesh: A multilevel analysis of demographic and health survey data. In R. T. Naved & S. Amin (Eds.), From evidence to policy: Addressing gender-based violence against women and girls in Bangladesh (pp. 22–51). Dhaka: icddr,b.

- Amin, S., Rahman, L., Hossain, S., & Naved, R. T. (2012). Introduction. In R. T. Naved & S. Amin (Eds.), Growing up safe and healthy (SAFE): Baseline report on sexual and reproductive health and rights and violence against women and girls in Dhaka slums (pp. 1–17). Dhaka: icddr,b.

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). (2015a). Report on labour force survey (LFS) Bangladesh 2013. Dhaka: BBS. Retrieved from Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics website: http://203.112.218.65:8008/WebTestApplication/userfiles/Image/LatestReports/LabourForceSurvey.2013.pdf

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). (2015b). Trends, patterns and determinants of marriage in Bangladesh. Dhaka: BBS.

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). (2016). Report on violence against women survey 2015. Dhaka: BBS. Retrieved from United Nations Population Fund: Asia & the Pacific website: https://asiapacific.unfpa.org/en/publications/2015-report-bangladesh-violence-against-women-survey.

- Bangladesh Planning Commission, Government of Bangladesh. (2015). Seventh five-year plan, FY2016–FY2020: Accelerating growth, empowering citizens. Dhaka: Government of Bangladesh. Retrieved from https://www.undp.org/content/dam/bangladesh/docs/Projects/IBFCR/national/7th%20Five%20Year%20Plan(Final%20Draft).pdf.

- Bates, L. M., Schuler, S. R., Islam, F., & Islam, K. (2004). Socioeconomic factors and processes associated with domestic violence in rural Bangladesh. International Family Planning Perspectives, 30(4), 190–199. doi:10.1363/ifpp.30.139.04 doi: 10.1363/3019004

- Bauer, G. R. (2014). Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: Challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Social Science & Medicine, 110, 10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.022

- Boyle, M. H., Georgiades, K., Cullen, J., & Racine, Y. (2009). Community influences on intimate partner violence in India: Women's education, attitudes towards mistreatment and standards of living. Social Science & Medicine, 69(5), 691–697. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.039

- Burrows, S., Butchart, A., Butler, N., Quigg, Z., Bellis, M. A., & Mikton, C. (2018). New WHO violence prevention information system, an interactive knowledge platform of scientific findings on violence. Injury Prevention, 24(2), 155–156. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2017-042694

- Campbell, J. C. (2002). Health consequences of intimate partner violence. The Lancet, 359(9314), 1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8

- Chin, Y.-M. (2012). Male backlash, bargaining, or exposure reduction? Women's working status and physical spousal violence in India. Journal of Population Economics, 25(1), 175–200. doi: 10.1007/s00148-011-0382-8

- Chisamya, G., DeJaeghere, J., Kendall, N., & Khan, M. A. (2012). Gender and education for all: Progress and problems in achieving gender equity. International Journal of Educational Development, 32(6), 743–755. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2011.10.004

- Cortina, J. M. (1993). What is coefficient alpha? An Examination of Theory and Applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(1), 98–104. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.98

- Crenshaw, K. W. (1998). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 14, 538–554. Retrieved from https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8

- Dalal, K., Rahman, F., & Jansson, B. (2009). Wife abuse in rural Bangladesh. Journal of Biosocial Science, 41(5), 561–573. doi: 10.1017/S0021932009990046

- Del Franco, N. (2010). Aspirations and self-hood: Exploring the meaning of higher secondary education for girl college students in rural Bangladesh. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 40(2), 147–165. doi: 10.1080/03057920903546005

- Devries, K. M., Mak, J. Y. T., García-Moreno, C., Petzold, M., Child, J. C., Falder, G., … Watts, C. H. (2013). The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science, 340(6140), 1527–1528. doi: 10.1126/science.1240937

- Dong, X. Q. (2015). Elder abuse: Systematic review and implications for practice. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63(6), 1214–1238. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13454

- Ehrensaft, M. K., Cohen, P., Brown, J., Smailes, E., Chen, H., & Johnson, J. G. (2003). Intergenerational transmission of partner violence: A 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(4), 741–753. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.4.741

- Fulu, E., Jewkes, R., Roselli, T., & Garcia-Moreno, C. (2013). Prevalence of and factors associated with male perpetration of intimate partner violence: Findings from the UN multi-country cross-sectional study on Men and violence in Asia and the Pacific. Lancet Global Health, 1(4), e187–e207. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70074-3

- Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children. (2018). Corporal punishment of children of Bangladesh. Retrieved from Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children website: https://www.endcorporalpunishment.org/wp-content/uploads/country-reports/Bangladesh.pdf

- Government of Bangladesh. (2011). National women development policy 2011. Dhaka: Ministry of Women and Children Affairs. Retrieved from https://mowca.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/mowca.portal.gov.bd/policies/64238d39_0ecd_4a56_b00c_b834cc54f88d/National-Women-Policy-2011English.pdf

- Government of Bangladesh. (2017a). Bangladesh Child Marriage Restraint Act 2017, Act 6 of 2017. Dhaka: Government of Bangladesh.

- Government of Bangladesh. (2017b). Eradicating poverty and promoting prosperity in a changing world: Voluntary national review. Retrieved from United Nations website: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/15826Bangladesh.pdf

- Hadi, A. (2005). Women's productive role and marital violence in Bangladesh. Journal of Family Violence, 20(3), 181–189. doi: 10.1007/s10896-005-3654-9

- Hadi, S. T. (2011). Perceptions, beliers, and attitudes towards intimate partner violence against women: An exploratory study of urban dating versus married participants in Bangladesh (Doctoral dissertation), Honolulu, HI. Retreived from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (Order no. 3485459).

- Hancock, A.-M. (2007). When multiplication doesn't equal quick addition: Examining intersectionality as a research paradigm. Perspectives on Politics, 5(1), 63–79. doi: 10.1017/S1537592707070065

- Hasan, T., Muhaddes, T., Camellia, S., Selim, N., & Rashid, S. F. (2014). Prevalence and experiences of intimate partner violence against women with disabilities in Bangladesh: Results of an explanatory sequential mixed-method study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(17), 3105–3126. doi: 10.1177/0886260514534525

- Hindin, M. J., Kishor, S., & Ansara, D. L. (2008). Intimate partner violence among couples in 10 DHS countries: Predictors and health outcomes. Calverton, MD: M. I. Inc. Retrieved from Demographic & Health Surveys (DHS) Program website: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/AS18/AS18.pdf.

- Hossain, A. N. M. Z. (2015). Women empowerment in rural local government of Bangladesh. International Journal of Innovation and Applied Studies, 10(2), 584–593.

- Huda, S. (2016). Five years after Bangladesh’s Domestic Violence (Prevention & Protection) Act 2010: Is it helping survivors? Dhaka: Plan International.

- Ismayilova, L. (2015). Spousal violence in 5 transitional countries: A population-based multilevel analysis of individual and contextual factors. American Journal of Public Health, 105(11), e12–e22. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302779

- Jewkes, R., Flood, M., & Lang, J. (2015). From work with men and boys to changes of social norms and reduction of inequities in gender relations: A conceptual shift in prevention of violence against women and girls. The Lancet, 385(9977), 1580–1589. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61683-4

- Kandiyoti, D. (1988). Bargaining with patriarchy. Gender and Society, 21(3), 274–290. doi: 10.1177/089124388002003004

- Kelly, U. A. (2011). Theories of intimate partner violence: From blaming the victim to acting against injustice: Intersectionality as an analytic framework. Advances in Nursing Science, 34(3), E29–E51. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0b013e3182272388

- Koenig, M. A., Ahmed, S., Hossain, M. B., & Mozumder, A. B. M. K. A. (2003). Women's status and domestic violence in rural Bangladesh: Individual- and community-level effects. Demography, 40(2), 269–288. doi:10.2307/3180801 doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0014

- Kohler, U., Karlson, K. B., & Holm, A. (2011). Comparing coefficients of nested nonlinear probability models. Stata Journal, 11(3), 420–438. doi: 10.1177/1536867X1101100306

- Liu, X. (2016). Applied ordinal logistic regression using Stata: From single-level to multilevel modelling (Kindle ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- McCall, L. (2005). The complexity of intersectionality. Signs, 30(3), 1771–1800. doi: 10.1086/426800

- National Institute of Population Research & Training, Mitra and Associates, & ICF International. (2009). Bangladesh demographic and health survey 2007. Dhaka and Rockville, MD: M. A. NIPORT, ICF International.

- Naved, R. T. (2008). Violence against women. In 2006 Bangladesh urban health survey (pp. 287–312). Dhaka and Chapel Hill, NC: NIPORT, MEASURE Evaluation, icddr,b, and ACPR.

- Naved, R. T., Al Mamun, M., Mourin, S. A., & Parvin, K. (2018). A cluster randomized controlled trial to assess the impact of SAFE on spousal violence against women and girls in slums of Dhaka, Bangladesh. PLOS ONE, 13(6), e0198926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198926

- Naved, R. T., & Persson, LÅ. (2005). Factors associated with spousal physical violence against women in Bangladesh. Studies in Family Planning, 36(4), 289–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2005.00071.x

- Pereira, F. (2002). The fractured scales: The search for a uniform personal code. Dhaka: Popular Prakashan.

- Rabe-Hesketh, S., & Skrondal, A. (2006). Multilevel modelling of complex survey data. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (Statistics in Society), 169(4), 805–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2006.00426.x

- Rashid, S. F. (2006). Emerging changes in reproductive behaviour among married adolescent girls in an urban slum in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Reproductive Health Matters, 14(27), 151–159. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(06)27221-5

- Sambisa, W., Angeles, G., Lance, P. M., Naved, R. T., & Thornton, J. (2011). Prevalence and correlates of physical spousal violence against women in slum and nonslum areas of urban Bangladesh. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(13), 2592–2618. doi: 10.1177/0886260510388282

- Schuler, S. R., Lenzi, R., Nazneen, S., & Bates, L. M. (2013). Perceived decline in intimate partner violence against women in Bangladesh: Qualitative evidence. Studies in Family Planning, 44(3), 243–257. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/23654757 doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2013.00356.x

- Schuler, S. R., & Nazneen, S. (2018). Does intimate partner violence decline as women's empowerment becomes normative? Perspectives of Bangladeshi women. World Development, 101, 284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.09.005

- StataCorp. (2017a). Stata statistical software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp.

- StataCorp. (2017b). Stata survey data reference manual: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp.

- Straus, M. A., Hamby, S. L., Boney-McCoy, S. U. E., & Sugarman, D. B. (1996). The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues, 17(3), 283–316. doi: 10.1177/019251396017003001

- United Nations. (2011). Concluding observations of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. Retrieved from United Nations website: https://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/cedaw/docs/co/cedaw-c-bgd-co-7.pdf.

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Retrieved from United Nations Population Fund website: https://www.unfpa.org/resources/transforming-our-world-2030-agenda-sustainable-development.

- United Nations Statistics Division. (2018). Sustainable development goal indicators. Retrieved from United Nations Global SDG Database website: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/database/.

- Warner, L. R. (2008). A best practices guide to intersectional approaches in psychological research. Sex Roles, 59(5), 454–463. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9504-5

- World Economic Forum. (2018). The global gender gap report 2018. Retrieved from World Economic Forum website: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2018.pdf.

- Yuval-Davis, N. (2011). Beyond the recognition and redistribution dichotomy: Intersectionality and stratification. In H. Lutz, M. T. H. Vivar, & L. Supik (Eds.), Framing intersectionality: Debates on a multi-facetted concept in gender studies (pp. 155–170). ( Kindle ed.). Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Ltd.