ABSTRACT

Occupational groups at high-risk of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) may be at increased risk of substance use because of occupation-related factors. We synthesised qualitative data on determinants and context of alcohol misuse and illicit drug use in these groups. We systematically searched five databases for qualitative studies reporting on alcohol misuse or illicit drug use in fisherfolk, uniformed personnel, miners, truckers, motorcycle taxi riders, and sex workers in SSA. Qualitative data and interpretations were extracted and synthesised using a systematic iterative process to capture themes and overarching concepts. We searched for papers published prior to January 2018. We identified 5692 papers, and included 21 papers in our review, published from 1993 to 2017. Most studies were conducted among fisherfolk (n = 4) or sex workers (n = 12). Ten papers reported on alcohol use alone, three on illicit drug use alone and eight on both. Substance use was commonly examined in the context of work and risky behaviour, key drivers identified included transactional sex, availability of disposable income, poverty, gender inequalities and work/living environments. Substance use was linked to risky behaviour and reduced perceived susceptibility to HIV. Our review underscores the importance of multilevel, integrated HIV prevention and harm reduction interventions in these settings.

KEYWORDS:

Background

Alcohol misuse and illicit drug use are major global health concerns, linked to infectious and non-infectious diseases, with a large social and economic burden born by individuals, families and society at large (United National Office on Drugs and Crime, Citation2018; World Health Organisation, Citation2018). Alcohol and illicit drug use may directly or indirectly facilitate HIV transmission through increased likelihood of risky sexual behaviour (Pandrea, Happel, Amedee, Bagby, & Nelson, Citation2010; Santos et al., Citation2013; Woldu et al., Citation2019), increased HIV shedding and increased inflammation at mucosal sites (Pandrea et al., Citation2010). Among people living with HIV, alcohol and illicit drug use may have negative effects on disease progression through several mechanisms including reduced uptake of HIV prevention and care services (Hendershot, Stoner, Pantalone, & Simoni, Citation2009) and through impacts on viral replication, host immunity and treatment compliance and efficacy (Hill et al., Citation2018; Pandrea et al., Citation2010) with implications not only for high-risk occupational groups but also for the wider general population with whom they may share sexual networks.

In a recent systematic review we showed that alcohol misuses and illicit drug use is common among occupational groups at high-risk of HIV in SSA (e.g. including sex workers (Baral et al., Citation2012), fisherfolk (Kissling et al., Citation2005; Kiwanuka et al., Citation2014; Kiwanuka et al., Citation2017; Kwena et al., Citation2019; Smolak, Citation2014), uniformed personnel (Azuonwu, Erhabor, & Obire, Citation2012), miners(Baltazar et al., Citation2015), motorcycle riders (Lindan et al., Citation2015), and truckers(Delany-Moretlwe et al., Citation2014)). The highest levels of substance use were recorded among sex workers and uniformed personnel (Kuteesa et al., Citation2019). A small number of studies in this review examined the association between alcohol use and HIV infection in SSA (Fisher, Bang, & Kapiga, Citation2007; Pithey & Parry, Citation2009). However, the review focused on quantitative outcomes of substance use and did not provide information on contextual determinants. To address this gap, we undertook a synthesis of multiple qualitative studies to document the individual and contextual factors that shape substance use in high-risk occupational sub-populations, aiming to collate data across different contexts, identify research gaps, and assess evidence for the development, implementation and evaluation of substance use reduction interventions.

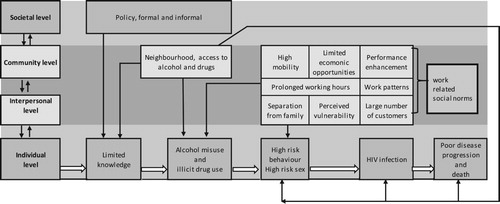

Our hypothesis is that occupation-related factors common to these groups might predict alcohol misuse and illicit drug use and other high-risk behaviour. Our theoretical framework draws upon the social ecological perspective (Scribner, Theall, Simonsen, & Robinson, Citation2010) to illustrate pathways through which social norms, work and work-related hazards including prolonged working hours, stigma e.g. from sex work, and prolonged separation from family might heighten an individual’s risk of substance use, and HIV (). The socioecological framework has been used to demonstrate multi-level influences on sexual risk behaviour and an elevated HIV burden among key population groups (Sileo, Kintu, Chanes-Mora, & Kiene, Citation2016). We do not assume that homogeneity exists across key population groups. The broad categories of sex workers, miners, truckers, motorcycle riders, uniformed personnel and fishing communities, consist of individuals with differential access to and experience of substance use. However, we presume they share common multi-level, work-related factors that may predispose them to increased substance use.

Methods

Search strategy

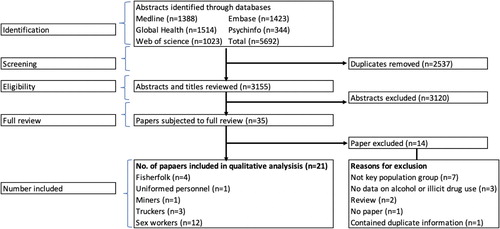

This qualitative data synthesis was conducted as part of a systematic review following Cochrane (Higgins & Green, Citation2011) and PRISMA reporting guidelines (‘Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses., Citation2015’). The review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (registration number CRD42016053495). The synthesis of quantitative papers has been published separately (Kuteesa et al., Citation2019).

We used a fourfold literature search strategy to identify studies on alcohol use, and illicit drug use among select high-risk occupational groups, specifically fisherfolk, uniformed personnel, miners, truckers, motorcycle taxi riders, and sex workers in SSA. First, we searched five online bibliographic data bases: Medline, Embase, Global health, Web of Science, PsycINFO, for peer-reviewed papers published prior to 16th January 2018, with no language restrictions, using single and combined search terms for alcohol, illicit drug use among high-risk occupational groups in SSA [supplemental material Tables 1 and 2]. We used broad search terms and, to ensure good coverage of all relevant literature, we did not include any search terms specifically related to qualitative data. Second, we examined reference lists of retrieved articles for potentially relevant articles based on titles and abstracts; third, we reviewed scientific conference presentations and technical organisational reports such as global state of harm reduction reports. Fourth, we contacted authors for relevant published and unpublished data.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Two reviewers independently reviewed each paper for inclusion in the synthesis. We read the papers several times to familiarise ourselves with the data. We assessed papers for inclusion and exclusion using a priori eligibility criteria. Specifically, we included peer reviewed papers from occupational groups in SSA at high-risk of HIV including fishing communities, uniformed personnel, truckers, miners, sex workers, and motorcycle taxi riders reporting qualitative data that pertained to experiences, risk factors, and context of alcohol misuse or illicit drug use. For purposes of this work, we used Creswell’s definition of qualitative research:

Qualitative research is an inquiry process of understanding based on distinct methodological traditions of inquiry that explore a social or human problem. The researcher builds a complex, holistic picture, analyses words, reports detailed views of informants, and conducts the study in a natural setting. (Cresswell, Citation1998, p. 15)

We excluded papers that did not clearly identify the population or did not provide separate results for high-risk occupational groups, or that reported data from the same study participants as another included paper (with equivalent or less information included) ().

Data extraction, synthesis and quality assessment

To add to the validity and transparency of the review process, we discussed our individual assessments in detail and agreed on how to resolve discrepancies about which studies to include, as they arose. We logged and recorded all decisions.

The first author took the lead in carrying out the analysis and discussed the analysis in detail at each stage with the second author. Included papers were imported into QSR International’s NVivo 12 program. We extracted textual data that represented study objectives, sample, participants’ social demographic characteristics, data collection methods, authors’ findings and interpretations as well as verbatim data from study participants (Noblit, Hare, & Hare, Citation1988). These provided the context for interpretation and explanation for each study. We conducted a qualitative text analysis on findings in the individual articles (Hennink, Hutter, & Bailey, Citation2010).

Data synthesis followed the framework outlined by Whittemore and Knafl (Whittemore & Knafl, Citation2005): data reduction; data display; data comparison; conclusion drawing; and verification. Four researchers coded a subset of the data in parallel to establish a coding framework. Coding was based on original data cited in papers as ‘participant understanding’ or ‘author interpretation’. Each team member drafted first-level codes that were organised initially around the review question. Differences in interpretation of codes were discussed at team meetings until consensus was reached. One main code tree that formed the basis for further coding was developed. Through an iterative process, we continuously adapted the coding tree based on emerging findings. Coding was cyclical and the coding scheme evolved during data analysis to allow deeper understanding and reflection to emerge (Weston et al., Citation2001). There was not consistent coding across all papers since the schedule evolved over time and the final version was not applied to all. To ensure credibility of the findings, the coding team used group consensus to examine codes and to determine if they were in opposition to each other, directly comparable or related. Within the team we condensed the coding list and finalised the coding schedule.

The emerging analysis was discussed among the coding team continuously. Data were categorised under specific subthemes. Primary themes or first-order constructs reflected participants’ views and understanding as reported in included studies whereas secondary themes/secondary order constructs were authors’ interpretations of study findings. We created a preliminary matrix to display sub-themes and concepts within each study under broad headings that reflected the purpose of the synthesis. We clustered related sub-themes together to form themes and used conceptual maps to summarise the data (Novak, Citation1990). Themes became increasingly refined through reciprocal translation, that is, the translation of studies into one another by comparing the themes and concepts in one account with those in others (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). We achieved data saturation when we could not identify new themes and when we had achieved a coherent understanding of the emergent themes whilst preserving nuances in the data. Data was conceptualised under the important or recurrent themes presented in the findings.

We assessed the quality of individual studies using a checklist based on common elements from existing criteria (Critical Appraisal Kills Programme, Citation2002; Mays & Pope, Citation2000; Pope, Mays, & Popay, Citation2006; Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, Citation2007). The assessment criteria included meeting the criteria of being a ‘qualitative study’, clarity of research questions; adequacy of reporting detail on the qualitative approach, study context, researchers’ role, sampling strategy, data collection and analysis; appropriateness of the research question, sampling strategy, data collection and analysis methods; and that the claims made were supported by sufficient evidence, . Three independent reviewers assessed study quality and resolved differences by group consensus.

Results

Description of papers

The search yielded 3155 non-duplicate papers. Following screening, we excluded 3120 papers which did not meet the eligibility criteria leaving 35 publications including one thesis. Of the 35 publications, we then excluded 14 papers because of lack of qualitative data on the topic (n = 1); no paper (n = 1); review (n = 2); no data on alcohol or illicit drug use (n = 3); not key population group (n = 7) (). We excluded the thesis because adequate information was contained in a paper by the same author (Sileo et al., Citation2016). We finally included 21 papers published between 1993 and 2017 in our data synthesis (). Most studies used qualitative descriptive methods, two used mixed methods. Sources of qualitative data included mapping, observation, in-depth interviews, key informant interviews, focus group discussions, and ethnography ().

Table 1. Summary of included studies by population group.

From the synthesis, we generated nine primary themes (identified from participants’ understanding) and secondary themes (identified from authors’ interpretation) (Supplementary Table 3). Some of which are described using direct quotes. We found a range of multi-level occupation-related drivers of substance use (Supplementary Table 4). Most studies met the methodological quality criteria, with a few exceptions (). No studies were excluded or accorded less importance based on quality because interpretations of what constitutes ‘quality’ in terms of methods in qualitative research, and the role of quality criteria and their application to systematic reviews remains an area of debate and evolution, reflecting different epistemological perspectives (Carroll & Booth, Citation2015; Dixon-Woods et al., Citation2007; Dixon-Woods, Shaw, Agarwal, & Smith, Citation2004; Walsh & Downe, Citation2006; Welch & Piekkari, Citation2017).

Table 2. Methodological quality of included studies (n = 21).

Description of themes

Substances used

Ten papers reported on alcohol use alone, three only on illicit drug use and eight on both. Studies by Mbonye et al. (Mbonye et al., Citation2012a) and Needle et al. (Needle et al., Citation2008) reported that sometimes alcohol and illicit drugs were used in combination. Commonly reported illicit drugs included heroin, cocaine, marijuana/cannabis, local synthetic drugs, and cannabis. Substance use was commonly examined in the context of risky behaviour, with substances used mainly as stimulants or disinhibiting agents for sex. Some occupational groups such as sex workers switched between alcohol and different types of illicit drugs according to availability, cost and to achieve different effects i.e. stimulation and disinhibition as ‘uppers’ and ‘downers’ (Needle et al., Citation2008). Studies described conflicting impact/effect of alcohol and illicit drug use. On the one hand, alcohol and illicit drug use was an enjoyable experience, and was not associated with significant self-perceived harm (Lubega et al., Citation2015; Nwokoji & Ajuwon, Citation2004; Parry, Petersen, Carney, Dewing, & Needle, Citation2008; Sileo et al., Citation2016). On the other hand, some papers reported perceived alcohol and illicit drug-related harms including impaired judgement (Erinosho, Isiugo-Abanihe, Joseph, & Dike, Citation2012; Mbonye et al., Citation2012a), vulnerability to sexually transmitted infections (Izugbara, Citation2005), and social harms such as violence, stigma and discrimination and social exclusion (Izugbara, Citation2005; Parry et al., Citation2009) (Supplementary Table 4).

Organisation of working environments

Work environments for truckers, fisherfolk, sex workers, miners and uniformed personnel were often in geographically remote locations and required separation from family for extended periods of time. For instance, papers on migrant miners and uniformed personnel populations described that because they lived away from their families, they felt they could behave differently, and engage in substance use.

… If their families are around, they don’t do that [drink excessively] … . – (uniformed personnel, Lightfoot et al., Citation2009, p. 325)

Gendered patterns of substance use

Studies reported that experiences with drug and alcohol use for women-centered more on the personal and emotional aspects of drug-related experiences while men’s experiences focused more on external factors such as socialisation and financial gain from sale of drugs. For example, in the mining sector, men employed in lower-ranking jobs often drank together in groups without interference from their family members whom they were often separated from, and to foster their group identity (Lightfoot, Maree, & Ananias, Citation2009). Similarly, in fishing communities, fishermen collectively used drugs and alcohol to cope with work-related stress (Sileo et al., Citation2016).

‘Physical and psychosocial stress’

Most occupational groups appeared to suffer some form of physical and psychosocial stress that drove their use of substances. Among fishermen, substance use was used to cope with work-related stress due to inconsistent/unpredictable income (Sileo, Citation2015; Sileo et al., Citation2016), prolonged working hours overnight (Sileo, Citation2015; Sileo et al., Citation2016) and fear of drowning (Lubega et al., Citation2015; Sileo, Citation2015; Sileo et al., Citation2016).

Loneliness was linked to relational deprivations mostly of family and social encounters characterised by some form of separateness. Among miners, feelings of loneliness were exacerbated by the structure of the mining workforce which relies on male migrant workers living in hostels and working irregular hours. Among uniformed personnel feelings of loneliness were triggered by prolonged separation from families. These feelings were counterbalanced by indulging in substance use as explained in the quote from a miner below’.

‘ … People are looking for things to vent their frustrations of loneliness’. Another said: ‘Most of them are not youngsters. They leave their family behind in the north. It’s quite difficult visiting your families. You can take three weeks per year: You don’t know what to do with yourselves. So you get together and have a drink or two … . It’s nice. You don’t feel lonely … ’ – (mine worker, Lightfoot et al., Citation2009, p. 324)

… Most of our women (referring to sex workers) drink and smoke a lot. I too smoke and drink … you know, in a situation where people treat you like the worst sinner you must find a way to feel like you are somebody. Sometimes your mind will be condemning you harshly … but when you drink and you are high, you feel normal … That is how we survive in this work … . – (sex worker, Ediomo-Ubong, Citation2012, p. 99)

External influence from pimps, sex work clients, and peers

Sex workers’ substance abuse patterns were often shaped by sex work clients and pimps who linked clients to sex workers, and sold and used substances themselves (Needle et al., Citation2008; Parry et al., Citation2008; Parry et al., Citation2009). On some occasions, clients invited and or pressured hired sex workers to use or share their illicit drugs with them (Mbonye et al., Citation2013; Sileo et al., Citation2016). Sex workers commonly received alcohol and illicit drugs from their clients as non-monetary payment for sex, and risked condomless sex to access illicit drugs.

… If they [the dealers] know you are a customer of them, you just go there, and you say … give me a wake-up, man. Then they say okay, there’s your wake-up.Footnote1 Then he knows, he will give you the wake-up, but that wake-up will make that you must return to him … so then … you get money, then you will go straight again back to him … . – (male sex worker, Parry et al., Citation2009, p. 856)

Poverty

High-risk occupational groups were mostly characterised by low socio-economic status and used substances as a means for income generation.

… You get these customers, they come to you and they want you … they are rock smokers themselves and it’s the girls, the working girls who put these men on to that. They tell them it’s a love drug, they will make love better. Even me, I have put somebody else onto it, just to get them to smoke so you can get more money … . – (female sex worker, Needle et al., Citation2008, p. 1451)

… Here we have too much money. In other places, they can only buy one or two [drinks}. Here they can buy ten … the richer you go, the worse it [drinking} gets. – (Miner, Lightfoot et al., Citation2009, pp. 324–325)

‘ … during windy periods, fishermen don’t work; [they] don’t have money so they don’t drink … ’. Alcohol sellers also reported that during periods of weak alcohol sales they would also engage in sex work to survive—Female alcohol seller in fishing community. (Sileo et al., Citation2016, p. 542)

Risk of violence

Alcohol and illicit drug use were a means to counter the risk of client violence against sex workers, including rape, refusal to pay for sex, and extortion through giving sex workers courage against abuses and victimisation. This facilitated substance use and consequently addiction among sex workers.

… You have to drink, smoke and be smart. In this work, you cannot be soft and think you will survive. You must be tough. You have to stand up for yourself because if you don’t nobody will do that for you … most women are not naturally strong that is why most of us take a lot of drinks to give us courage so that when a man wants to do something funny, you can defend yourself … . (sex worker, Ediomo-Ubong, Citation2012, p. 99)

Proximity to substance use establishments

Across all occupational groups, substance use patterns were shaped by the work environment. All occupational groups lived or worked in close proximity to bars/lodges and illicit drug selling establishments some of which operated all the time. Members of occupational groups were regular patrons at these facilities to access cheap over-night accommodation, alcohol and illicit drugs. Furthermore, the institutional context of working in bars potentially influenced substance use through inadequate regulation of sale and consumption of substances, and access to pimps. Conversely, although bars were perceived to charge higher prices for alcohol than other alcohol selling stores, some sex workers preferred to work in bars to easily access clients and to reduce the risk of violence.

Performance enhancement

Sex workers, fisherfolk, and truckers all used substances to enhance their individual performance at work, enabling them to meet physical demands, including long working hours, and coping with night chills for sex workers and fishermen (Ediomo-Ubong, Citation2012; Parry et al., Citation2009; Sileo et al., Citation2016).

… Sometimes when there is less fish at the site, the fishermen have little money and they don’t buy us expensively. You have to sleep with many men (5–10) in a day to earn a living so sometimes we have to take alcohol or drugs (marijuana) so we have the courage to do this or even not to feel the psychological pain … . – (barmaid/sex worker, fishing community, Lubega et al., Citation2015, p. 7)

The authors of a few papers reported that sex workers mentioned drinking and illicit drug use before and during sex work, in order to be sexually forward, and to achieve sexual effects such as enhancing the sexual experience including stimulating sexual arousal, prolonging the sexual experience and having multiple sexual partners and ease of negotiating condom and or non-condom use as necessary (Mbonye et al., Citation2013; Parry et al., Citation2009).

… We would take alcohol and even forget to ask for money. I used to take too much of it and it was up to the man to put on the condom … that alcohol eliminates shyness and you become bold. It gives you happiness and you forget about all your worries … . – (sex worker, Mbonye et al., Citation2012a, Citation2012b, p. 6)

Inadequate healthcare services

High-risk occupational groups are vulnerable to substance use due to inadequate prevention, treatment and mitigation measures and limited access to alcohol reduction interventions and harm reduction services more generally (Abikoye, Citation2015).

Discussion

In this review of qualitative data on alcohol misuse and illicit drug use among occupational groups at high-risk of HIV in SSA, we describe multi-level experiences and determinants of substance use. A major finding of our review is that despite differences in local contexts and patterns of use, harmful drinking and illicit drug use are common across the different high-risk occupational groups studied, and are part of the occupational culture. Patterns and frequency of alcohol and illicit drug use were commonly linked with multi-level interacting factors in particular social, workplace and employment characteristics of different occupational high-risk groups. The risk for substance use among these sub-populations was further compounded by the lack of local harm reduction services.

Our review suggests that compared to the general population, occupational groups engaged in high-risk activities might be more vulnerable to hazardous drinking and chronic illicit drug use, and therefore may suffer adverse consequences from the associated complications.

There was substantial overlap in both individual and contextual factors for substance use across the papers reviewed. At individual level, our findings show that substance use consequently directly facilitated participation in work, particularly for sex workers (Needle et al., Citation2008; Parry et al., Citation2008; Parry et al., Citation2009) and fisherfolk (Lubega et al., Citation2015; Sileo et al., Citation2016). The most common pathway to substance use was motivational, both for enhancement of positive emotions – such as improved ability to be sexually forward and – reduction of negative feelings – such as stress management and perceived work-related vulnerabilities. This was similar to pathways identified by Cox and Klingers (Cox & Klinger, Citation2011).

Across the population groups, sex work as a livelihood has received greatest focus, with sex workers viewed as a subset of people whose illicit drug use has become problematic, and who could benefit from harm reduction services (Jeal, Macleod, Turner, & Salisbury, Citation2015; Li, Li, & Stanton, Citation2010). Alcohol and illicit drug use by other occupational groups at high-risk of HIV was less well documented and understood, with a dearth of information on related harms and ways to reduce them in these sub-groups.

Individual behaviour in these sub-populations continues to be shaped by people’s immediate physical and social environment such as residing in an environment with access to bars and lodges for leisure, as well as interactions between systems and individuals (Sallis, Owen, & Fisher, Citation2008). The social and symbolic context of drinking and illicit drug use suggests that effective interventions around substance use should not be limited to drinking environments alone but should mirror the patterns of sale, promotion and distribution of substances many of which occur outside alcohol and drug selling establishments and may involve pimps who largely determine patterns of substance use (Needle et al., Citation2008; Parry et al., Citation2008; Parry et al., Citation2009).

The most common structural drivers of substance use were separation from family and widespread poverty. Poverty related sub-themes interacted in complex ways with implications for problem drinking and illicit drug addiction. In addition, sex workers and fisherfolk (Sileo et al., Citation2016) used substances to gain control over their clients for more money, and to facilitate condom or non-condom use negotiations, as necessary.

Some risk factors for substance use varied by occupational group and gender. Among sex workers, alcohol and illicit drug use was shaped by the social organisation of sex work, including attracting and maintaining relations with clients, enhancing role performance, coping with stigma and threats of violence from clients, pimps and law enforcement agents. In fishing communities, certain gender-focussed roles (such as fishing, mainly conducted by men) were associated with alcohol and illicit drug use. Harm reduction services will need to be responsive to the occupational norms and gender roles of the different high-risk groups.

Most of the occupational groups were mobile or migratory to maintain their livelihoods, and this was reported to increase their likelihood of using substances, firstly to better cope with prolonged separation from family and secondly because the social structures that otherwise constrained substance use in home communities may not apply in the context of their new setting. Migration patterns may contribute not only to increased substance use but also to sexual risk in general (Kissling et al., Citation2005).

Mixing of high-risk occupational groups is common, and there is an overlapping of sex work and illicit drug use, behaviours and economies. This is partly because of the unstable social situations of the groups including high mobility and ‘hot spots’ for commercial sex activity where long-distance truckers, fisherfolk, uniformed personnel, miners regularly commune. Similarly, the different occupational groups spent most of their leisure time in bars and brothels where sex work, alcohol and illicit drugs were commonly sold and consumed. This evidence further highlights the need for alcohol-related and harm reduction services and policies that take into account the social networks of high-risk occupation groups.

Despite reports of alcohol misuse and increasing intravenous injection of illicit drugs and their association with risky sex among young people in SSA (Beckerleg, Telfer, & Hundt, Citation2005; Francis, Grosskurth, Changalucha, Kapiga, & Weiss, Citation2014; Nkowane et al., Citation2004; Reid, Citation2009), research on substance use among young people in high-risk occupational settings is very limited. Yet it is critical to tailored programming. Young people in these settings are likely to be particularly vulnerable to alcohol and illicit drug use related harms for several reasons including developmental, social economic and environmental factors. Furthermore, their vulnerability may be exacerbated by barriers to accessing help ranging from limited information about their risks and rights to legal age and sex work restrictions that impede access to harm reduction services.

Interventions

Drawing on the social-ecological model of occupational factors influencing substance use (), interventions should be designed which acknowledge that substance use is integral to high-risk groups; the role of sexual networks in reinforcing substance use; and the influence of gender and poverty on substance use.

There is a danger that focusing too narrowly on these groups or on substance-using individuals neglects other sub-populations at high-risk, such as young people. We suggest that to avert substance use in these sub-groups, the net of alcohol reduction and harm reduction interventions be cast wider, to include all young people. Interventions should build on social and family support mechanisms, be tailored towards community needs, and not be simply targeted to individuals. In addition, given the overlap between sex work as an occupation, and the other occupations, there may be a place for harm reduction interventions in venues frequented by multiple occupations. High-risk occupation communities in developing countries are often mobile and socially marginalised and have poor access to facilities and medicines and low uptake of available health services (Seeley & Allison, Citation2005). One way to improve the likelihood of both developing effective interventions and improving the success of adoption and implementation in these communities is through renewed efforts to strengthen the structural interventions component of HIV combination prevention services to include alcohol reduction and harm reduction interventions (Campbell, Tross, & Calsyn, Citation2013).

Research could also focus on other structural issues that our systematic review uncovered such as violence (Javalkar et al., Citation2019; Starmann et al., Citation2018), stigma, discrimination and the legal status of sex work as an occupation (Blanchard et al., Citation2018). These social, legal, and economic injustices not only contribute to sex workers’ high risk of acquiring HIV but also substance abuse, and would be important to address (Rusakova, Rakhmetova, & Strathdee, Citation2015).

Recommendations

In addition to harm-reduction research, literature recommends structural interventions in sex work contexts where substance abuse increases vulnerability to HIV including removal of legal barriers through the decriminalisation of sex work (Blanchard et al., Citation2018; Javalkar et al., Citation2019; Shannon et al., Citation2018; Starmann et al., Citation2018). Future research should, in particular, explore: (i) individual and contextual factors associated with substance use (initiation, promotion and continued use) among young people aged 18 years and below, in key population settings; (ii) pathways to substance use among under-researched groups such as uniformed personnel, truckers and miners, paying attention to the unique contribution of their work and work environments.

Study strength

To our knowledge, this is the first review summarising qualitative data on alcohol misuse and illicit drug use among occupational groups at high-risk of HIV in SSA.

Study limitations

The main limitations include firstly the lack of diversity; our search yielded fewer papers from uniformed personnel, truckers and miners, hence biasing our review to sex workers and fisherfolk, whose pathways to alcohol and illicit drug use in the context of their work may be different. Secondly, studies among uniformed personnel and truckers only reported on alcohol and not illicit drugs. It is unclear whether this reflects a lack of usage of other drugs in these populations or simply a lack of research on this. Either way, our exploration of illicit drug use was consequently limited to only certain key population groups. Other limitations are that the final code was not applied to all of the manuscripts and the study quality was not consistent across the included manuscripts.

Conclusion

The findings of this data synthesis highlight that there are interrelated motivations for alcohol misuse, illicit drug use and sex work among occupational groups at high risk of HIV. Joint HIV prevention and harm reduction interventions that are responsive to contextual and occupational risk factors are critical.

RGPH_2019-0028_Supplementary_Material.doc

Download MS Word (318.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Monica O. Kuteesa http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4296-1398

Janet Seeley http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0583-5272

Sarah Cook http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1250-2967

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 ‘wake ups’ are usually small pieces of crack cocaine given to male and female sex workers by pimps (whether they work for them or not) in order to motivate the sex worker to earn money and to ensure that the sex worker returns to buy more drugs from them.

References

- Abikoye, G. E. (2015). Factors affecting the management of substance use disorders: Evidence from selected service users in Bayelsa state. African Journal of Drug and Alcohol Studies, 14(2), 115–123.

- Azuonwu, O., Erhabor, O., & Obire, O. (2012). HIV among military personnel in the Niger Delta of Nigeria. Journal of Community Health, 37(1), 25–31. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9411-5

- Baltazar, C. S., Horth, R., Inguane, C., Sathane, I., Cesar, F., Ricardo, H., … Young, P. W. (2015). HIV prevalence and risk behaviors among Mozambicans working in South African mines. AIDS & Behavior, 19(Suppl. 1), 59–67. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0941-6

- Baral, S., Beyrer, C., Muessig, K., Poteat, T., Wirtz, A. L., Decker, M. R., … Kerrigan, D. (2012). Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 12(7), 538–549. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(12)70066-x

- Beckerleg, S., Telfer, M., & Hundt, G. L. (2005). The rise of injecting drug use in east Africa: A case study from Kenya. Harm Reduction Journal, 2(1), 12. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-2-12

- Blanchard, A. K., Nair, S. G., Bruce, S. G., Ramanaik, S., Thalinja, R., Murthy, S., … Chaitanya, A. T. M. S. (2018). A community-based qualitative study on the experience and understandings of intimate partner violence and HIV vulnerability from the perspectives of female sex workers and male intimate partners in North Karnataka state, India. BMC Women's Health, 18(1), 66. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0554-8

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Campbell, A. N. C., Tross, S., & Calsyn, D. A. (2013). Substance use disorders and HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment intervention: Research and practice considerations. Social Work in Public Health, 28(3-4), 333–348. doi: 10.1080/19371918.2013.774665

- Carroll, C., & Booth, A. (2015). Quality assessment of qualitative evidence for systematic review and synthesis: Is it meaningful, and if so, how should it be performed? Research Synthesis Methods, 6(2), 149–154. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1128

- Cox, W. M., & Klinger, E. (2011). A motivational model of alcohol use: Determinants of use and change. Handbook of Motivational Counselling: Goal-Based Approaches to Assessment and Intervention with Addiction and Other Problems, 131–158. doi: 10.1002/9780470979952.ch6

- Cresswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Critical Appraisal Kills Programme. (2002). Ten questions to help you make sense of qualitative research. Retrieved from https://www.phru.nhs.uk/learning/casp_qualitative_tool.pdf

- Delany-Moretlwe, S., Bello, B., Kinross, P., Oliff, M., Chersich, M., Kleinschmidt, I., & Rees, H. (2014). HIV prevalence and risk in long-distance truck drivers in South Africa: A national cross-sectional survey. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 25(6), 428–438. doi: 10.1177/0956462413512803

- Dixon-Woods, M., Shaw, R. L., Agarwal, S., & Smith, J. A. (2004). The problem of appraising qualitative research. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 13(3), 223–225. doi: 10.1136/qhc.13.3.223

- Dixon-Woods, M., Sutton, A., Shaw, R., Miller, T., Smith, J., Young, B., … Jones, D. (2007). Appraising qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: A quantitative and qualitative comparison of three methods. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 12(1), 42–47. doi: 10.1258/135581907779497486

- Ediomo-Ubong, E. (2012). Sex work, drug use and sexual health risks: Occupational norms among brothel-based sex workers in a Nigerian city. African Journal of Drug and Alcohol Studies, 11(2), 95–105.

- Erinosho, O., Isiugo-Abanihe, U., Joseph, R., & Dike, N. (2012). Persistence of risky sexual behaviours and HIV/AIDS: Evidence from qualitative data in three Nigerian communities. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 16(1), 113–123.

- Fisher, J. C., Bang, H., & Kapiga, S. H. (2007). The association between HIV infection and alcohol use: A systematic review and meta-analysis of African studies. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 34(11), 856–863. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318067b4fd

- Francis, J. M., Grosskurth, H., Changalucha, J., Kapiga, S. H., & Weiss, H. A. (2014). Systematic review and meta-analysis: Prevalence of alcohol use among young people in Eastern Africa. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 19(4), 476–488. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12267

- Hendershot, C. S., Stoner, S. A., Pantalone, D. W., & Simoni, J. M. (2009). Alcohol use and antiretroviral adherence: Review and meta-analysis. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 52(2), 180. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b18b6e

- Hennink, M., Hutter, I., & Bailey, A. (2010). Qualitative research methods. City Road, London: Sage.

- Higgins, J. P. T., & Green, S. (Eds.). (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated July 2018]. The Cochrane Collaboration.

- Hill, L. M., Golin, C. E., Gottfredson, N. C., Pence, B. W., DiPrete, B., Carda-Auten, J., … Flynn, P. M. (2018). Drug use mediates the relationship between depressive symptoms and adherence to ART among recently incarcerated people living with HIV. AIDS & Behavior, doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2355-3

- Izugbara, C. (2005). ‘Ashawo suppose shine her eyes’: Female sex workers and sex work risks in Nigeria. Health, Risk & Society, 7(2), 141–159. doi: 10.1080/13698570500108685

- Javalkar, P., Platt, L., Prakash, R., Beattie, T., Bhattacharjee, P., Thalinja, R., … Heise, L. (2019). What determines violence among female sex workers in an intimate partner relationship? Findings from North Karnataka, south India. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 350. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6673-9

- Jeal, N., Macleod, J., Turner, K., & Salisbury, C. (2015). Systematic review of interventions to reduce illicit drug use in female drug-dependent street sex workers. BMJ Open, 5(11), e009238. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009238

- Kissling, E., Allison, E. H., Seeley, J. A., Russell, S., Bachmann, M., Musgrave, S. D., & Heck, S. (2005). Fisherfolk are among groups most at risk of HIV: Cross-country analysis of prevalence and numbers infected. Aids (london, England), 19(17), 1939–1946. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000191925.54679.94

- Kiwanuka, N., Ssetaala, A., Nalutaaya, A., Mpendo, J., Wambuzi, M., Nanvubya, A., … Balyegisawa, A. (2014). High incidence of HIV-1 infection in a general population of fishing communities around Lake Victoria, Uganda. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource], 9(5), e94932. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094932

- Kiwanuka, N., Ssetaala, A., Ssekandi, I., Nalutaaya, A., Kitandwe, P. K., Ssempiira, J., … Sewankambo, N. K. (2017). Population attributable fraction of incident HIV infections associated with alcohol consumption in fishing communities around Lake Victoria, Uganda. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource], 12(2), e0171200. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171200

- Kohli, A., Kerrigan, D., Brahmbhatt, H., Likindikoki, S., Beckham, J., Mwampashi, A., … Kennedy, C. E. (2017). Social and structural factors related to HIV risk among truck drivers passing through the Iringa region of Tanzania. AIDS Care, 29(8), 957–960. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1280127

- Kuteesa, M. O., Seeley, J., Weiss, H. A., Cook, S., Kamali, A., & Webb, E. L. (2019). Alcohol misuse and illicit drug use among occupational groups at high risk of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. AIDS and Behavior. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02483-y

- Kwena, Z. A., Njuguna, S. W., Ssetala, A., Seeley, J., Nielsen, L., De Bont, J., & Bukusi, E. A. (2019). HIV prevalence, spatial distribution and risk factors for HIV infection in the Kenyan fishing communities of Lake Victoria. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource], 14(3), e0214360. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214360

- Langa, J., Sousa, C., Sidat, M., Kroeger, K., McLellan-Lemal, E., Belani, H., … Needle, R. (2014). HIV risk perception and behavior among sex workers in three major urban centers of Mozambique. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource], 9(4), e94838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094838

- Li, Q., Li, X., & Stanton, B. (2010). Alcohol use among female sex workers and male clients: An integrative review of global literature. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 45(2), 188–199. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp095

- Lightfoot, E., Maree, M., & Ananias, J. (2009). Exploring the relationship between HIV and alcohol use in a remote Namibian mining community. African Journal of AIDS Research, 8(3), 321–327. doi: 10.2989/AJAR.2009.8.3.8.929

- Lindan, C. P., Anglemyer, A., Hladik, W., Barker, J., Lubwama, G., Rutherford, G., … Group, C. S. (2015). High-risk motorcycle taxi drivers in the HIV/AIDS era: A respondent-driven sampling survey in Kampala, Uganda. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 26(5), 336–345. doi: 10.1177/0956462414538006

- Lubega, M., Nakyaanjo, N., Nansubuga, S., Hiire, E., Kigozi, G., Nakigozi, G., … Gray, R. (2015). Risk denial and socio-economic factors related to high HIV transmission in a fishing community in Rakai, Uganda: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource], 10(8), e0132740. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132740

- Matovu, J. K. B., & Ssebadduka, N. B. (2013). Knowledge, attitudes & barriers to condom use among female sex workers and truck drivers in Uganda: A mixed-methods study. African Health Sciences, 13(4), 1027–1033. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v13i4.24

- Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2000). Qualitative research in health care. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ, 320(7226), 50–52. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50

- Mbonye, M., Nakamanya, S., Nalukenge, W., King, R., Vandepitte, J., & Seeley, J. (2013). ‘It is like a tomato stall where someone can pick what he likes’: Structure and practices of female sex work in Kampala, Uganda. Bmc Public Health, 13, 9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-741

- Mbonye, M., Nalukenge, W., Nakamanya, S., Nalusiba, B., King, R., Vandepitte, J., & Seeley, J. (2012a). Gender inequity in the lives of women involved in sex work in Kampala, Uganda. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 15 (no pagination)(633). doi: 10.7448/IAS.15.3.17365

- Mbonye, M., Nalukenge, W., Nakamanya, S., Nalusiba, B., King, R., Vandepitte, J., & Seeley, J. (2012b). Gender inequity in the lives of women involved in sex work in Kampala, Uganda. Journal of The international Aids Society, 15(Suppl. 1), 1–9. doi: 10.7448/ias.15.3.17365

- Mbonye, M., Seeley, J., Nalugya, R., Kiwanuka, T., Bagiire, D., Mugyenyi, M., … Kamali, A. (2016). Test and treat: The early experiences in a clinic serving women at high risk of HIV infection in Kampala. AIDS Care, 28(Suppl. 3), 33–38. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1164804

- Michalopoulos, L. T., Baca-Atlas, S. N., Simona, S. J., Jiwatram-Negron, T., Ncube, A., & Chery, M. B. (2017). “Life at the river is a living hell”: A qualitative study of trauma, mental health, substance use and HIV risk behavior among female fish traders from the Kafue Flatlands in Zambia. BMC Women’s Health, 17(1), 15. doi: 10.1186/s12905-017-0369-z

- Needle, R., Kroeger, K., Belani, H., Achrekar, A., Parry, C. D., & Dewing, S. (2008). Sex, drugs, and HIV: Rapid assessment of HIV risk behaviors among street-based drug using sex workers in Durban. South Africa. Social Science and Medicine, 67(9), 1447–1455. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.031

- Nelson, E.-U. E. (2012). Sex work, drug use and sexual health risks: Occupational norms among brothel-based sex workers in a Nigerian city. African Journal of Drug and Alcohol Studies, 11(2), 95–105.

- Nkowane, M. A., Rocha-Silva, L., Saxena, S., Mbatia, J., Ndubani, P., & Weir-Smith, G. (2004). Psychoactive substance use among young people: Findings of a multi-center study in three African countries. Contemporary Drug Problems, 31(2), 329–356.

- Noblit, G. W., Hare, R. D., & Hare, R. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies (Vol. 11). London: Sage.

- Novak, J. D. (1990). Concept maps and Vee diagrams: Two metacognitive tools to facilitate meaningful learning. Instructional Science, 19(1), 29–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00377984

- Nwokoji, U. A., & Ajuwon, A.J. (2004). Knowledge of AIDS and HIV risk-related sexual behavior among Nigerian naval personnel. Bmc Public Health, 4, 1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-24

- Onyango, M. A., Adu-Sarkodie, Y., Agyarko-Poku, T., Asafo, M. K., Sylvester, J., Wondergem, P., … Beard, J. (2015). It’s all about making a life": Poverty, HIV, violence, and other vulnerabilities faced by young female sex workers in Kumasi, Ghana. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 68, S131–S137. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000455

- Pandrea, I., Happel, K. I., Amedee, A. M., Bagby, G. J., & Nelson, S. (2010). Alcohol’s role in HIV transmission and disease progression. Alcohol Research & Health, 33(3), 203–218.

- Parry, C. D., Dewing, S., Petersen, P., Carney, T., Needle, R., Kroeger, K., & Treger, L. (2009). Rapid assessment of HIV risk behavior in drug using sex workers in three cities in South Africa. AIDS & Behavior, 13(5), 849–859. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9367-3

- Parry, C., Petersen, P., Carney, T., Dewing, S., & Needle, R. (2008). Rapid assessment of drug use and sexual HIV risk patterns among vulnerable drug-using populations in Cape Town, Durban and Pretoria, South Africa. SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS, 5(3), 113–119. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2008.9724909

- Pithey, A., & Parry, C. (2009). Descriptive systematic review of sub-Saharan African studies on the association between alcohol use and HIV infection. SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS, 6(4), 155–169. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2009.9724944

- Pope, C., Mays, N., & Popay, J. (2006). How can we synthesize qualitative and quantitative evidence for healthcare policy-makers and managers? Healthcare Management Forum, 19(1), 27–31. doi: 10.1016/s0840-4704(10)60079-8

- Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. (2015). Retrieved from https://www.prisma-statement.org/

- Reid, S. R. (2009). Injection drug use, unsafe medical injections, and HIV in Africa: A systematic review. Harm Reduction Journal, 6(1), 24. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-6-24

- Rusakova, M., Rakhmetova, A., & Strathdee, S. A. (2015). Why are sex workers who use substances at risk for HIV? Lancet, 385(9964), 211–212. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61042-4

- Sallis, J., Owen, N., & Fisher, E. (2008). Ecological models of health behavior. In K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, & K. Viswanath (Eds.), Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2015.1124456

- Santos, G. M., Coffin, P. O., Das, M., Matheson, T., DeMicco, E., Raiford, J. L., … Herbst, J. H. (2013). Dose-response associations between number and frequency of substance use and high-risk sexual behaviors among HIV-negative substance-using men who have sex with men (SUMSM) in San Francisco. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 63(4), 540–544. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318293f10b

- Schulkind, J., Mbonye, M., Watts, C., & Seeley, J. (2016). The social context of gender-based violence, alcohol use and HIV risk among women involved in high-risk sexual behaviour and their intimate partners in Kampala, Uganda. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 18(7), 770–784. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2015.1124456

- Scribner, R., Theall, K. P., Simonsen, N., & Robinson, W. (2010). HIV risk and the alcohol environment: Advancing an ecological epidemiology for HIV/AIDS. Alcohol Research & Health, 33(3), 179. PMC3860511.

- Seeley, J. A., & Allison, E. H. (2005). HIV/AIDS in fishing communities: Challenges to delivering antiretroviral therapy to vulnerable groups. AIDS Care, 17(6), 688–697. doi:10.1080/09540120412331336698.

- Shannon, K., Crago, A. L., Baral, S. D., Bekker, L. G., Kerrigan, D., Decker, M. R., … Beyrer, C. (2018). The global response and unmet actions for HIV and sex workers. Lancet, 392(10148), 698–710. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31439-9

- Sileo, K. (2015). Motivation for alcohol use in the context of commercial sex work and its influence on sexual risk: A qualitative study in Ugandan fishing communities. Paper presented at the 2015 APHA Annual Meeting & Expo (October 31–November 4, 2015).

- Sileo, K. M., Kintu, M., Chanes-Mora, P., & Kiene, S. M. (2016). “Such behaviors are not in my home village, I got them here”: A qualitative study of the influence of contextual factors on alcohol and HIV risk behaviors in a fishing community on Lake Victoria, Uganda. AIDS and Behavior, 20(3), 537–547. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1077-z

- Smolak, A. (2014). A meta-analysis and systematic review of HIV risk behavior among fishermen. AIDS Care, 26(3), 282–291. doi:10.1080/09540121.2013.824541.

- Starmann, E., Heise, L., Kyegombe, N., Devries, K., Abramsky, T., Michau, L., … Collumbien, M. (2018). Examining diffusion to understand the how of SASA!, a violence against women and HIV prevention intervention in Uganda. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 616. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5508-4.

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- United National Office on Drugs and Crime. (2018). World drug report. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/wdr2018/

- Walsh, D., & Downe, S. (2006). Appraising the quality of qualitative research. Midwifery, 22(2), 108–119. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2005.05.004

- Watt, M. H., Kimani, S. M., Skinner, D., & Meade, C. S. (2016). “Nothing is free”: A qualitative study of sex trading among methamphetamine users in Cape Town, South Africa. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(4), 923–933. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0418-8

- Welch, C., & Piekkari, R. (2017). How should we (not) judge the ‘quality’ of qualitative research? A re-assessment of current evaluative criteria in international business. Journal of World Business, 52(5), 714–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jwb.2017.05.007

- Weston, C., Gandell, T., Beauchamp, J., McAlpine, L., Wiseman, C., & Beauchamp, C. (2001). Analyzing interview data: The development and evolution of a coding system. Qualitative Sociology, 24(3), 381–400. doi: 10.1023/A:1010690908200

- Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

- Woldu, D. O., Haile, Z. T., Howard, S., Walther, C., Otieno, A., & Lado, B. (2019). Association between substance use and concurrent sexual relationships among urban slum dwellers in Nairobi, Kenya. AIDS Care, 1–7. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2019.1595519

- World Health Organisation. (2018). Global status report on alcohol and health. Geneva. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/global_alcohol_report/en/