ABSTRACT

The major challenges in controlling the Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) outbreak in Guinea were contact tracing, referral of suspected cases, secure burial and mistrust in the context of a weak health system. Community involvement and uptake of key interventions were very low, contributing to the spread of the epidemic. A community engagement project, using community based organisations (CBOs) and community leaders, was implemented in four affected health districts in rural Guinea. This paper reports on the contribution of the CBOs and community leaders in controlling the EVD outbreak. Base-, mid- and end – line assessments were conducted using a mixed methods approach. In total, 422 CBOs members, 50 community leaders and 40 village birth attendants were engaged in social mobilisation, awareness raising, reaching 154,310 people and leading to the end of reluctance and mistrust. Thus, 95 suspected cases were referred to health facilities, contact tracing and secure burial increased from 88.0% to 96.6% and from 67% to 95.4%, respectively, and institutional deliveries increased from 637 to 806. Involvement of CBOs and community leaders against the EVD outbreak is an effective resource that should also be considered to better respond to possible large-scale epidemic threats in a fragile health system context.

Introduction

In West Africa, during the 2014–2016 Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) outbreak, 28,616 cases (confirmed, probable and suspected) were reported with 40% of deaths (WHO, Citation2016). Taking into account the human, economic and health consequences, the EVD outbreak in West Africa is considered as the largest and worst ever witnessed (Chan, Citation2014; Group of independent experts, Citation2015; Heymann et al., Citation1980). It weakened the economy and the health system of the three most affected countries (Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea) and exacerbated mistrust between communities, governments and humanitarian actors (Group of independent experts, Citation2015). At the end of the EVD outbreak in West Africa, the World Health Organization (WHO) stressed the need for enhanced surveillance and good preparedness to prevent or better manage future public health emergencies (WHO, Citation2016).

In Guinea, 2543 deaths out of 3811 cases (66.7%) were recorded (Ebola Task Force, Citation2016). At the epidemic beginning, key interventions in the affected localities were not optimally implemented and the health system was not prepared to cope with such an epidemic (Chan, Citation2014; Fairhead, Citation2015; Gostin, Citation2014). This resulted in the rapid spread of the outbreak in Guinea and neighbouring countries (Chan, Citation2014; Gostin, Citation2014; Group of independent experts, Citation2015).

The response was mainly focused on medical care strategies, leaving aside culturally sensitive messages and community engagement in the control of the epidemic (Fairhead, Citation2015; Group of independent experts, Citation2015; Thiam et al., Citation2015). However, traditional cultural practices, including funeral and burial customs, contributed to virus transmission (Group of independent experts, Citation2015). Also and essentially, bleak public messaging emphasised that no treatment was available (Group of independent experts, Citation2015). All this led to mistrust between response teams and communities, resulting in some areas in reluctance and violence against humanitarian actors and health personnel (Anoko, Citation2014; Group of independent experts, Citation2015; Thiam et al., Citation2015). Community involvement is critical in public health interventions. And during the EVD epidemic populations can play an essential role particularly in the identification of contacts, early notification, compliance with infection prevention and control and secure burials (Mbonye et al., Citation2014; Schiavo et al., Citation2014).

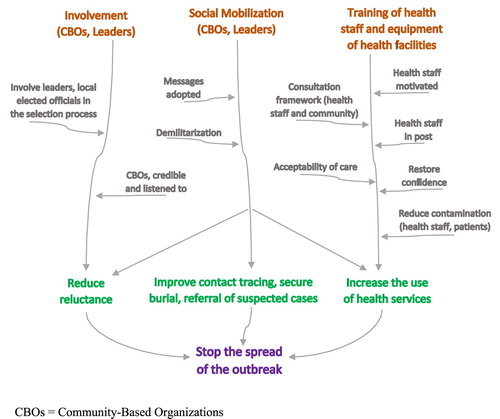

In this context, the leading international health NGO based in Africa, Amref Health Africa on the basis of a needs assessment (Thiam et al., Citation2015), initiated and implemented a community mobilisation project as part of the outbreak response in Guinea. The intervention strategy included the involvement of community-based organisations (CBOs) such as women's groups, youth associations and community leaders in the response. In particular, the NGO worked to empower CBOs about EVD prevention and care, in order to carry out the response activities within their own communities. The involvement of CBOs as actors in health activities is a new approach in Guinea. Health authorities have always relied on community health workers (CHWs) to carry out activities at the local level (Gillespie et al., Citation2016). However, during this outbreak, the community members questioned the credibility of CHWs who make the link between the community and health system (Anoko, Citation2014; Thiam et al., Citation2015). Therefore, empowering community members to engage in health issues during an emergency such as the EVD outbreak was justified and necessary. The project’s overall objective was to stop the spread of the outbreak in four affected health districts. Specifically, the project aimed at (1) ending community reluctance to control measures, (2) improving contact tracing and secure burials and (3) increasing health services utilisation. Thus, the current paper reports on the contribution of CBOs and community leaders in controlling the EVD outbreak in four affected health districts in Guinea.

Methods

Study settings and population

Guinea is a West African country with an estimated population of 12 million inhabitants in 2018 and the majority living in rural areas (64%) (Guinea Ministry of Plan, Citation2018). The Guinean health system includes local (district), intermediate (region) and central (Ministry of health) levels. There are eight regions and 38 health districts. Four health districts (Coyah, Dubréka, Forécariah and Kindia) were targeted by the intervention because of the ongoing EVD related reluctance and resistance reported at that time from these localities (Guinea Ministry of Health, Citation2015).

The four districts covered an estimated population of 1,495,000 inhabitants. The target districts are located near the capital city Conakry, especially Dubréka and Coyah, which are currently considered as high suburbs of the capital. Forecariah and Kindia share borders with Sierra Leone, facilitating cross-border exchange and mobility. Fishing, agriculture and small businesses are the main activities in these areas.

Study design

We conducted this study as part of a community engagement project which was assessed before, during and after, using a parallel mixed method in four health districts (Forécariah, Coyah, Dubréka and Kindia). The base- and end – line assessments were carried out in December 2014 and June 2016, respectively. As for the midline assessment, it took place during the project implementation period, precisely in June 2015 and February 2016. Indeed, the baseline assessment identified the major issues that mainly included the irregular contact tracing, the increase of insecure burials, the under-reporting of suspected cases, the lack of community engagement resulting in the persistence of rumours and reluctance at community level, and the decrease in using health services due to the lack of confidence in health staff (Thiam et al., Citation2015). The midline assessment focussing on the analysis of routine data (quantitative) and the endline assessment (qualitative component only) both aimed at evaluating the effects of the intervention on controlling the outbreak in study sites.

Overview of the project

The project was implemented along three main areas, namely the involvement of CBOs and community leaders (i), social mobilisation (ii) and improvement of the health sector response (training of health staff and equipment of health facilities) (iii) ().

Identification and training of CBOs and leaders

The strategy for identifying CBOs was based on a participatory approach, with the involvement of local elected officials who have a perfect knowledge of the youth and women's associations or groups in their localities. The selection criteria included the notoriety of the association and its dynamism at the community level. These CBOs had in common to be recognised by the various local authorities to develop activities of community interest, such as agriculture, market gardening, dyeing or soap making. Overall 422 members from 38 CBOs, 50 community leaders, and 40 village birth attendants were selected from localities where reluctance persisted in the four health districts. The participation of CBOs in health-related activities was a new approach in these localities, as these organisations usually focus on social or income-generating activities. Therefore, prior to engaging with community awareness raising, these community actors benefited from a two-day practical training conducted in local languages on the basic knowledge of the EVD, the use of image box and the thermo-flash and the filling of data collection tools. In addition to the training, each CBO benefited from institutional capacity building on various aspects including organisational process, financial management, leadership. Furthermore, each CBO was provided a monthly grant to support their social mobilisation activities.

Community mobilisation

Different communication approaches were used, including home visits for household awareness, identification and referral of suspected cases, talks with other community groups, community round tables about issues related to the outbreak control measures, advocacy meetings with community leaders and distribution of hygiene kits to households. Additionally, periodic meetings were held in health centres or administrative facilities, involving actors at the local level (CBOs, community leaders, local elected officials, Red Cross and other humanitarian actors) in order to share information on activities and response strategies, as well as to strengthen collaboration among them. A total of 16 rural communities were covered by social mobilisation activities ().

Table 1. Community mobilisation activities in four health districts, Guinea, 2015.

Improving the health sector response through the training of health staff and equipment of health facilities

Health facilities were identified in close collaboration with district medical officers and district coordinations for EVD response. Prior to any support, a needs assessment was conducted in each health facility. The training of health staff in these facilities on EVD prevention and control measures was carried out by other partners. The intervention improved the reception capacity of 16 health centres and care of patients through donations of hospital beds, delivery tables, chairs, scales weighs – children, surgical boxes. Two of the health centres benefited from drilling (water supply).

Sampling

A simple random sampling was used to select health centres and specific sites to visit in the targeted health districts. A purposive sampling technique along with a snowball sampling were used to recruit the qualitative sample while ensuring maximum variation in the sample and achieving saturation of the answers during data collection. We also followed the principle of the gradual selection of key respondents based on new ideas and according to relevant criteria (locality, administrative responsibility, level of involvement in response interventions, influence in the community).

Study variables

Quantitative variables included routine data on the use of health services (institutional delivery) and epidemiological indicators (contact tracing and secure burials).

Suspected case of Ebola: Either any living person who has been in contact with a confirmed or probable case and who has presented one of the following: sudden onset of high fever OR at least three of the following symptoms: headache, anorexia/loss of appetite, lethargy, muscle/joint pain, breathing difficulties, vomiting, diarrhoea, stomach ache, difficulty swallowing and hiccups, or Anyone with unexplained bleeding.

Confirmed case of Ebola: a suspected case with a positive laboratory result.

Community death: a deceased person outside an Ebola treatment centre (ETC).

Secure burial: death occurred in the community, the result of the harvest is positive and the burial is carried out by the burial agents (Red Cross).

Contact: any person who has been in direct contact with a confirmed patient or a suspected case.

Qualitative variables included the perceptions of beneficiaries of the project regarding its relevance and effectiveness on community reluctance.

Reluctance: any act of violence against the actors of the response or refusal to collaborate with the EVD response teams.

Data collection procedures

Quantitative data (aggregated) were collected from the weekly epidemiological situation reports diffused by the Ministry of Health using a standardised Excel sheet.

As for qualitative data, they were collected through field observation, in-depth interviews (IDIs) and focus group discussions (FGDs). Field observation consisted of participating observations and informal conversations, independent from the interviews. It has been used to compare opinions expressed in IDIs or FGDs. IDIs were performed with key respondents using an interview guide; they allowed to estimate the effects of the intervention on stopping transmission of EVD in covered areas. These IDIs provided information on the relevance, effectiveness of the intervention and its complementarity with other interventions, as well as the effect of its implementation on reducing reluctance and adherence of the community to the national guidelines for response to the EVD epidemic (contact tracing, reporting of deaths and secure burials). FGDs were carried out using an interview frame, with the CBOs and the community leaders benefiting from the intervention; this was to collect their perceptions on the process of its implementation (good practices and challenges). IDIs and FGDs were recorded.

Data analysis

Quantitative strand

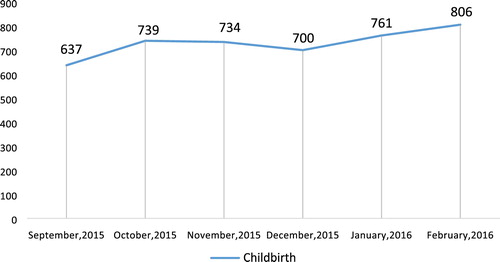

Data from the Excel sheet were exported to Epi Info software, version 7 for analysis. Data were summarised as descriptive statistics (numbers and proportions for contact tracing and secure burials, monthly trend of number of institutional deliveries represented as epidemiological curve).

Qualitative strand

Raw data from notes and recordings were transcribed into French. Data were then analysed using deductive and inductive thematic analysis. Data transcription and analysis were performed simultaneously using an iterative process. At the end of each day, the data transcribed by data collectors were analysed by supervisors and field investigators.

Ethical considerations

As the intervention took place in an emergency context, the evaluation protocols (baseline and final assessments) were not submitted to the Guinea national ethics committee. However, all interviewees were informed before any interview was conducted, about the objectives of the studies, the type of questions and the intended use of the results, as well as their right to withdraw from the interview at any time or have any information removed during or after the interview. The confidentiality of the interviewees was ensured through anonymity of the data collection forms. The investigators obtained an oral consent from all respondents. Oral consent was preferred because of the context of mistrust that prevailed at the moment.

Results

In total, 71 IDIs and 25 FGDs were carried out, alongside 19 out of the 36 health centres existing in the four health districts were visited.

End of community reluctance

In most localities of the four health districts, community tensions existed against health professionals prior to the intervention, increasing the risk of disease spread. They were perceived by the community as actors contributing to the persistence of the outbreak. As a result, health staff were forced to avoid communication about the disease in the community. Sometimes, the health district coordinations for fighting against the EVD were obliged to be accompanied by the military forces to pick up the suspected individuals or dead bodies in the community. But, thanks to the implementation of the project the situation changed.

Today we can go to Molota in a white pickup without fear of being stoned. This change in the behaviour of communities that initially were hostile to any idea of fighting Ebola is attributable to the awareness raising of people by other citizens closer to them. Health Manager, Kindia

This intervention had a place in fighting Ebola outbreak. There was a strong reluctance in our community, but with Amref, everything became well and there is no reluctance at the moment, CBO Member, Tanènè, Dubréka.

The success of the intervention, according to the local authorities, was attributed to the way in which the different stakeholders were involved. The community approach reassured local leaders and communities. This empowerment of communities facilitated their effective and efficient involvement in the observance of the EVD outbreak control measures.

Currently, families have our phone numbers, when there is a community death, we are called and we immediately alert the Red Cross, CBO manager, Wonkifong, Coyah.

Improvement of contact tracing and secure burials

The approach facilitated contact tracing and deaths reporting as well as securing of burials. For instance, contact tracing and secure burials improved respectively from 88.0% to 99.6% and from 67.0% to 95.4%, with no more contact to be traced and community death in the health districts of Coyah and Kindia ().

Table 2. Contact tracing, community deaths and secure burials in four health districts, Guinea, April and June 2015.

Increase of the use of health services

The mistrust between health staff and communities resulted in the reduction of the use of health services such as maternal and child health services. Patients resorted to self-medication or traditional healers, in a context where all patients should normally be screened for EVD symptoms by health staff. Our experience showed that setting up frameworks for consultation and exchange of information between community actors and health staff as well as strengthening the capacity of health centres in equipment and water supply to improve the quality of care, contributed to stop rumours and reduce mistrust. Thus, the trust restored between communities and the local health system led to the abandonment of violence toward EVD response teams. This resulted in the resumption of the use of health services by the communities. Yes, [Amref] support has greatly contributed to the return of the sick people to the health centres. Currently, we have a lot of patients on market days. Healthcare worker, Molota, Kindia. In accordance to what was testified by respondents, the analysis of routine data showed as an example an increase in institutional deliveries from 637 in September 2015–806 in February 2016 ().

Discussion

This study is one of the few to report on direct community engagement in controlling the EVD outbreak in Guinea. It highlights the fact that community engagement was critical in fighting the deadly outbreak in the Guinean context while emphasising the importance of considering incentives for community organisations instead of individuals, depending on the existing economic and socio-cultural needs (Gillespie et al., Citation2016). Therefore, it is crucial, in such contexts, to bridge community interventions with local health system strengthening (Laverack & Manoncourt, Citation2016; Wilkinson et al., Citation2017). Our findings highlight four main areas that needs further attention: community reluctance, contact tracing, secure burials, and health services utilisation.

Community reluctance

This study revealed that the involvement of local communities, including CBOs and community leaders in the EVD response was helpful in reducing community reluctance. Understanding community members’ perceptions about the EVD response along with their expectations guided the common identification of appropriate and urgent actions to be implemented to reverse the trend of the outbreak. The approach was well appreciated by the community leaders who, therefore, took an active part in raising awareness and promoting prevention and hygiene measures. Furthermore, the selection of local actors through a transparent and participatory process led to the selection of credible and respected CBOs and community leaders. Putting the community at the centre of the intervention, as an actor and partner, played a major role in reducing or even stopping reluctance and violence against EVD response teams. This approach was found by community actor as new. In fact, health authorities often rely on CHWs and community relays to carry out activities within communities. Our experience showed that CBOs can be a credible resource and partner in addressing community health issues. Providing training to CBOs members using communication tools adapted to the local context and institutional capacity building were sufficient to get their buy in.

Similar results have been reported in studies from Uganda (Sigridur, Citation2016) and Sierra Leone (Li et al., Citation2016) where community entities were involved in EVD response. These two studies showed that the training and involvement of local residents, especially influential people, helped decrease reluctance and resistance to humanitarian actors. Another study (Gillespie et al., Citation2016) in the three most affected countries by the EVD outbreak in West Africa, showed that local mobilisers played an important role in three key areas: the removal of community resistance, understanding of local context (socio-cultural norms and decision-making processes), and finally the facilitation of the vaccination trial against EVD.

Contact tracing and secure burials

The major challenges in managing the EVD outbreak in Guinea included contact tracing and secure burials (Gillespie et al., Citation2016; Greiner et al., Citation2015). The reasons included the fact that communities were not following the prevention guidelines at the beginning of the outbreak, which explains the rapid spread and persistence of the outbreak in Guinea and neighbouring countries (Gillespie et al., Citation2016; Group of independent experts, Citation2015).

Our experience suggests that empowering local leaders and organisations to carry out response activities in their own communities would facilitate community's understanding of the disease and related health risks. In addition, it would enable communities to adhere to prevention and control measures, including contact tracing and secure burials of dead people. The challenge in such context is to make CBOs the partners and points of contact for humanitarian actors within the community.

Our findings are in line with that of studies in Sierra Leone (Laverack & Manoncourt, Citation2016) and Liberia (Abramowitz et al., Citation2015) on the EVD community response. These studies reported that the involvement of community actors in response activities contributed effectively to contact tracing and the respect of the secure burial protocols. Another study conducted in Sierra Leone (Li et al., Citation2016) reported that the involvement of local mobilisers in contact tracing reduced the time of contamination of the disease to a median time of 1 d as compared to 1.9 days in areas where local mobilisers were not used.

Use of health services

We found that the use of health services increased mainly thanks to the community engagement in response activities. Our results are similar to those reported in a study on EVD outbreak in Uganda in 2012 where health authorities agreed to engage the community in response activities (de Vries et al., Citation2016). In contrast, a study conducted in the Forest Region of Guinea (epicentre of the EVD outbreak) on the impact of the Ebola outbreak on maternal and child health services, showed that indicators declined during and after the outbreak period compared to the pre-epidemic period. The persistence of mistrust between the community and health staff during the outbreak was one of possible reasons reported by the authors (Delamou et al., Citation2017).

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study has the merit to be the first in its kind to report on direct contribution of communities in controlling an outbreak in Guinea. it used a mixed method approach including quantitative and qualitative strands and document review. However, the study has some limitations. First, the substantial decrease of EVD cases to zero in our intervention areas could not be only attributable to the impact of our intervention because there were several other EVD control activities ongoing from many other partners. The end of the epidemic could also be due to its natural evolution. Second, we could not compare our approach to other community mobilisation approaches such as village watch committees implemented in other sites where there was also reluctance. Third, the respondents’ interviews were carried out in an emergency context, which did not allow enough time for deep discussions. Also, because of the susceptibility that prevailed at the moment, we could not record interviews. This could have caused information biases, including memory bias at the time of the interview summary. To address this, each interview was conducted by two interviewers for IDIs and four for FGDs to allow triangulation of summaries.

Conclusion

CBOs can be an effective resource in EVD response at the community level. Involvement of the community in planning and implementation of interventions is paramount for their appropriation of response’s interventions. In addition, capacity building of CBOs and frontline health facilities has the potential to strengthen community resilience to health threats. Future efforts to strengthen the health system should focus on community empowerment, building local leadership and strengthening the linkages between local communities and peripheral health system, and not just on building infrastructure and training the health staff.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank all participants in this study for their collaboration and especially the populations, community leaders, CBOs and health workers and authorities of the four health districts (Forécariah, Coyah, Kindia and Dubréka). We also thank the Amref Health Africa U.S.A. team for their support and the Paul Allen Foundation for funding this project. SC, AD and TMM designed the baseline and endline assessments and developed the tools. ST, BN and SC coordinated the study. TMM led data collection teams (investigators) with supervision from AD and SC. Data analyses were performed by SC, AD and TMM. KK managed the implementation of the project (intervention). TMM drafted the manuscript with AD and SC. AD, ST and BN revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abramowitz, S. A., Lean, K. E., Kune, S. L., Bardosh, K. L., Fallah, M., & Monger, J. (2015). Community-Centered responses to Ebola in urban Liberia: The view from below. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 9(4), e0003706. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0003706

- Anoko, J. N. (2014). Communication with rebellious communities during an outbreak of Ebola virus disease in Guinea: An anthropological approach. http://www.ebola-anthropology.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Communicationduring-an-outbreak-of-Ebola-Virus-Disease-with-rebellious-communities-in-Guinea.pdf

- Chan, M. (2014). Ebola Virus disease in West Africa - no early end to the outbreak. The New England Journal of Medicine, 371(13), 1183–1185. http://www.nejm.org/doi/abs/10.1056/NEJMp1409859

- de Vries, D. H., Rwemisisi, J. T., Musinguzi, L. K., Benoni, T. E., Muhangi, D., & de Groot, M. (2016). The first mile: Community experience of outbreak control during an Ebola outbreak in Luwero district. Uganda. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 161. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/16/161 doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2852-0

- Delamou, A., Ayadi, A. M., Sidibe, S., Delvaux, T., Camara, B. S., & Sandouno, S. D. (2017). Effect of Ebola virus disease on maternal and child health services in Guinea: A retrospective observational cohort study. The Lancet Global Health, 5(4), e448–e457. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28237252/ doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30078-5

- Ebola Task Force. (2016). Epidemiological situation report: Ebola virus disease in Guinea (Sitrep_no 703, unpublished report).

- Fairhead, J. (2015). Understanding social resistance to Ebola response in Guinea. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311752067_Understanding_Social_Resistance_to_the_Ebola_Response_in_the_Forest_Region_of_the_Republic_of_Guinea_An_Anthropological_Perspective

- Gillespie, A. M., Obregon, R., Asawi, R., Richey, C., Manoncourt, E., Joshi, K., Naqvi, S., Pouye, A., Safi, N., Chitnis, K., & Quereshi, S. (2016). Social mobilization and community engagement central to the Ebola response in West Africa: Lessons for future public health emergencies. Global Health, Science and Practice, 4(4), 626–646. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28031301 doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00226

- Gostin, L. O. (2014). Ebola: Towards an international health systems fund. The Lancet, 384(9951), e49–e51. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25201591 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61345-3

- Greiner, A. L., Angelo, K. M., Collum, A. M., Mirkovic, K., Arthur, R., & Angulo, F. J. (2015). Addressing contact tracing challenges-critical to halting Ebola virus disease transmission. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 41, 53–55. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26546808 doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.10.025

- Group of independent experts. (2015). Ebola interim assessment panel. https://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/ebola/report-by-panel.pdf?ua=1

- Guinea Ministry of Health. (2015). Ebola virus disease situation report. http://guinea-ebov.github.io/sitreps.html

- Guinea Ministry of Plan. (2018). National Institute of Statistics: 2018 Statistical Yearbook. Guinea. http://www.stat-guinee.org/

- Heymann, D. L., Weisfeld, J. S., Webb, P. A., Johnson, K. M., Cairns, T., & Berquist, H. (1980). Ebola hemorrhagic fever: Tandala, Zaire, 1977-1978. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 142(3), 372–376. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7441008 doi: 10.1093/infdis/142.3.372

- Laverack, G., & Manoncourt, E. (2016). Key experiences of community engagement and social mobilization in the Ebola response. Global Health Promotion, 23(1), 79–82. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26518037 doi: 10.1177/1757975915606674

- Li, Z. J., Tu, W. X., Wang, X. C., Shi, G. Q., Yin, Z. D., & Su, H. J. (2015). A practical community-based response strategy to interrupt Ebola transmission in Sierra Leone, 2014–2015. Infectious Diseases of Poverty, 5(1), 74. http://idpjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40249-016-0167-0

- Mbonye, A., Wamala, J., Nanyunja, M., Opio, A., Makumbi, I., & Aceng, J. (2014). Ebola viral hemorrhagic disease outbreak in West Africa- Lessons from Uganda. African Health Sciences, 14(3), 495. http://www.ajol.info/index.php/ahs/article/view/107213 doi: 10.4314/ahs.v14i3.1

- Schiavo, R., Leung, M. M., & Brown, M. (2014). Communicating risk and promoting disease mitigation measures in epidemics and emerging disease settings. Pathogens and Glob Health, 108(2), 76–94. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1179/2047773214Y.0000000127

- Sigridur, B. T. (2016). Evaluation of Ebola response – Uganda. https://www.medbox.org/assessment-studies/evaluation-of-ebola-response-uganda/toolboxes/preview?q=

- Thiam, S., Delamou, A., Camara, S., Carter, J., Lama, E. K., Ndiaye, B., Nyagero, J., Nduba, J., & Ngom, M. (2015). Challenges in controlling the Ebola outbreak in two prefectures in Guinea: Why did communities continue to resist? Pan African Medical Journal, 22(1), 22. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26740850

- WHO. (2016). Ebola virus disease situation report. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/208876/1/ebolasitrep_2June2016_fre.pdf?ua=1

- Wilkinson, A., Parker, M., Martineau, F., & Leach, M. (2017). Engaging 'communities': Anthropological insights from the west African Ebola epidemic. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 372(1721), 20160305. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28396476 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0305