ABSTRACT

District Health Management Teams (DHMTs) are often entry points for the implementation of health interventions. Insight into decision-making and power relationships at district level could assist DHMTs to make better use of their decision space. This study explored how district-level health system decision-making is shaped by power dynamics in different decentralised contexts in Ghana, Malawi and Uganda. In-depth interviews took place with national- and district-level stakeholders. To unravel how power dynamics influence decision-making, the Arts and Van Tatenhove (Citation2004) framework was applied. In Ghana and Malawi, the national-level Ministry of Health substantially influenced district-level decision-making, because of dispositional power based on financial resources and hierarchy. In Uganda and Malawi, devolution led to decision-making being strongly influenced by relational power, in the form of politics, particularly by district-level political bodies. Structural power based on societal structures was less visible, however, the origin, ethnicity or gender of decision-makers could make them more or less credible, thereby influencing distribution of power. As a result of these different power dynamics, DHMTs experienced a narrow decision space and expressed feelings of disempowerment. DHMTs’ decision-making power can be expanded through using their unique insights into the health realities of their districts and through joint collaborations with political bodies.

Introduction

In many low- and middle-income countries, the district health system is the entry point for the implementation and scale-up of health policies and interventions (Waiswa et al., Citation2016). District health systems comprise a variety of primary health care centres and hospitals managed by district health management teams (DHMTs) (Doherty et al., Citation2018). In decentralised contexts, the decision-making authority is transferred from national to district level (Kwamie et al., Citation2015a). As such, DHMTs and other district-level actors make decisions about which health areas and interventions to prioritise; they contextualise, adapt and implement policies, strategies and interventions developed at the national level; and scale up health interventions at district level.

DHMTs work in complex environments where the type of decentralised system (from deconcentration, delegation to devolution) influences their decision space (Alonso-Garbayo et al., Citation2017). Decision space can be defined as ‘the range of effective choice that is allowed by the central authorities to be utilised by local authorities’ (Bossert, Citation1997, p. 16). The decision space at the district level, including that of DHMTs, tends to remain narrow in a decentralised system, if the existing hierarchies of the previous centralised system prevail (Kwamie et al., Citation2015a). Power dynamics shape both the development and implementation of health policies at national and district levels (Erasmus & Gilson, Citation2008; Mwisongo et al., Citation2016), and the decisions of DHMTs (Mwisongo et al., Citation2016). Power can be seen as ‘the degree of control over material, human, intellectual and financial resources exercised by different sections of society’ (VeneKlasen et al., Citation2002, p. 41). It is exercised between individuals and groups through their political, social and economic relations and alters over time based on changes in context or the interests of actors (McCollum et al., Citation2018). These complex and changing relations can make it difficult to understand how power among different actors is manifested (Mwisongo et al., Citation2016).

DHMTs are often held fully accountable for district health system performance (Kwamie et al., Citation2015a). Therefore, it is important to understand how decisions are made at this level, and particularly how the role of DHMTs in decision-making is influenced by power dynamics between different actors at the district, regional and national levels. There have been few studies that assessed how management decisions are made at district level. Some have focused on how evidence is used to make decisions (Mutemwa, Citation2005; Wickremasinghe et al., Citation2016), on the involvement of the public in decision-making (Kapiriri et al., Citation2003) or how district health managers perceive and use their decision space for human resource management (Alonso-Garbayo et al., Citation2017). However, they do not explore how power influences DHMTs’ roles in district-level decision-making across different contexts. To plan successful implementation and scale-up of health interventions, we need a better understanding of the DHMT's decision-making power and the power relationships with other actors at district, regional and national levels. This study aimed to explore how district-level health system decision-making is shaped by power dynamics between different actors at district, regional and national levels in different decentralised contexts in Ghana, Malawi and Uganda. Study insights may assist DHMTs to reflect upon and optimally use their decision space while implementing and scaling up health interventions.

Materials and methods

Context of the three countries

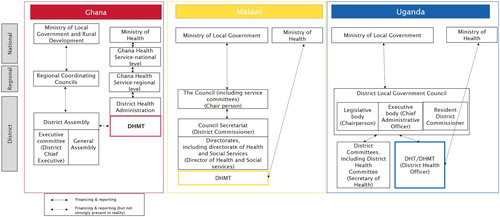

This study was performed as part of the PERFORM2Scale project (an implementation research consortiumFootnote1), which aims to scale-up a management strengthening intervention with DHMTs in Ghana, Malawi and Uganda (2017–2021). These three countries were chosen because of differences in decentralisation, which influence the decision space of DHMTs. In Ghana, the main forms of decentralisation entail delegating health sector management to semi-public institutions and ‘deconcentrating’ authority to regions and district. In Uganda, health service delivery functions are ‘devolved’ to the local governments (Bossert & Beauvais, Citation2002). In Malawi, devolution is envisioned but is still in a transition phase resulting in partial devolution of power and authority (Jagero et al., Citation2014). An overview of the health governance structures in the three countries is provided in .

Ghana

Since 1993, Ghana has been administratively decentralised through delegation and deconcentration (Sumah & Baatiema, Citation2019) and is currently organised into sixteen regions and 260 districts (GhanaDistricts, Citation2019). Decentralisation is regulated by two legislative documents: The Local Government Act of 1993 (Act 462) and The Ghana Health Service and Teaching Hospitals Act (Act 525) (Couttolenc, Citation2012; Kwamie et al., Citation2015a; Sumah & Baatiema, Citation2019). Act 462 describes the District Assemblies as the highest political decision-making body in the district, but does not include their roles and responsibilities regarding health. Act 525 describes the delegation of administrative decision-making from the Ministry of Health to the Ghana Health Service (GHS) at the national, regional and district levels. visualises different structures and how they relate to each other. The GHS is an agency of the Ministry of Health and is responsible for the management and operation of health service delivery at national, regional, district and sub-district levels (Couttolenc, Citation2012); The District Director of Health Services (DDHS), which is the head of the DHMT, reports to the Regional Director of the GHS, and the Regional Director reports to the Director General of GHS (Kwamie et al., Citation2015a). The District Assembly is made up of two central bodies: the General Assembly (the political/legislative body) and the Executive Committee (administrative body) and make decisions about all sectors, not just health (Doh, Citation2017). The General Assembly consists of 70% elected assembly members, with the remaining 30% appointed by the government. The Executive Committee is the highest administrative decision-making body within the District Assembly and is led by the District Chief Executive (DCE), who is assigned by government and confirmed by two-thirds of the District assembly members. The committee also includes heads of sub-committees of the General Assembly and heads of the decentralised agencies, for example the heads of the Ghana Education Service (District Director of Education) and the Ghana Health Service (the DDHS) (Doh, Citation2017; Tettey et al., Citation2003). A brief overview of the difference in function between the political and administrative bodies is provided in . This structure means that DHMTs have dual lines of reporting and financing: from the DHMT to the District Assembly and from the DHMT to the GHS, leading to confusion in roles and responsibilities (Couttolenc, Citation2012; Kwamie et al., Citation2015a; Sumah & Baatiema, Citation2019).

Table 1. Explanation of administrative and political body (Hansen & Ejersbo, Citation2002; Kathyola, Citation2010; Pretorius, Citation2017).

Malawi

The Local Government Act of 1998 established the framework for the decentralisation process in Malawi (Tambulasi & Alawattage, Citation2007). The decentralisation policy envisions devolution to 35 Local Government Areas. Local Government areas include 4 cities, 2 municipalities and 1 town and 28 districts which are governed by authorities called Councils. Councils consist of two bodies: the Council itself (political body) and the Council Secretariat (administrative body), both headed by the District Commissioner (Government of Malawi, Citation2013). The Councils comprise of elected councillors, members of parliament, chiefs and representatives of special interest groups. The Council has seven Service Committees, including one for health. The Council Secretariat (the administrative body) is staffed by civil servants and has several directorates, of which one is the Directorate of Health and Social Services (Government of Malawi, Citation2013).

Changes in health administrative responsibilities continue as decentralisation evolves. Of note are two main changes. First, previously the districts fell under five zone-levels (Borghi et al., Citation2017). At the time of data collection (2018), the zone level no longer exist as a separate level in the health system but instead take on quality assurance roles under the Quality Management Directorate of the national Ministry of Health. Second, instead of the District Health Officer (DHO) being head of the DHMT, there will be a Director of Health and Social Services based at the District Council. As such, the DHMT will fall under the directorate of Health and Social Services and will be headed by the District Medical Officer. Malawi is currently in a state of transition and therefore, not all the planned reforms were implemented as intended resulting in different situations in different districts at the time of data collection.

Uganda

In Uganda, decentralisation policies have been progressively implemented since 1986 across the 127 districts. Political, administrative and financial decentralisation took place, mostly through devolution of the government services (Henriksson, Citation2017). The 1997 Local Government Act limited the roles of the national-level agencies to policy formulation, quality assurance and supervision of the local government (Alonso-Garbayo et al., Citation2017; Uganda Legal Information Institute, Citation1997). One of the major changes that took place was the shift of power from administrative actors at national level to political actors at district level (Jeppsson, Citation2004). The district, which is responsible for the management of health service delivery, is governed by a District Local Government Council, often referred to as the District Council. Within the District Council, the elected chairperson is the head of the legislative body (the political body) and the Chief Administrative Officer (CAO) is the head of the executive body (administrative body) (Jeppsson, Citation2004). In addition, the Resident District Commissioner (RDC), appointed by the president, is tasked with monitoring the implementation of national and local government services(Jeppsson, Citation2004). Members from the District Council form different district committees. One of these is the District Health Committee presided over by the Secretary of Health and this is the political governing body of the health sector. In Uganda, the District Health Team (DHT) implements the health policies and health sector plans and comprises the leads of district health programs. The DHMT is a larger body, which includes not only the DHT but also health centre managers, members from other departments, political and administrative district leaders and representatives from private health care providers and local NGOs and is headed by the DHO. The DHT and DHMT report to the CAO (Tetui et al., Citation2016, p. 3).

Study process and data collection

Political Economy Analysis is used in the Perform2Scale project to analyse changing (power) dynamics in the policy environment that influences the scale-up of a district-level management strengthening intervention. Before the implementation of the project, a context analysis study using qualitative methods was conducted to understand the facilitators of and barriers to policy implementation and scale-up of health interventions in Ghana, Malawi and Uganda, with a focus on the political economy at the district level. This exploratory study on decision-making in the district health system draws on findings from the broader context analysis. Study participants were purposefully selected (Tuckett, Citation2004) based on their position, and knowledge about power relations and hierarchy of decision-making powers in the district. Eighty-two (82) in-depth interviews with national and district-level stakeholders in Ghana, Malawi and Uganda were performed at the beginning of 2018 (). The national stakeholders included heads of departments, directors of commissions from the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Local Government, and representatives from health-related non-governmental organisations (NGOs). The district stakeholders included DHMT members, political and administrative staff, and representatives of NGOs implementing health-related programs in the selected study districts. In Malawi, no interviews with politicians at district level and NGOs took place due to their unavailability. In Ghana, national-level stakeholders from the Ministry of Local Government were not included in the sample because of limited working relationships between this Ministry and the DHMTs. Instead interviews with the Regional Ministry of Health were conducted. Most participants were men, with only 21 out of the 82 interviewees being female (Malawi = 4, Ghana = 11, Uganda = 6).

Table 2. Overview of interviewees.

The district-level interviews were performed in three districts in Ghana, three in Uganda and six in Malawi.Footnote2 The higher number of districts in Malawi was due to a change in the focus districts for the project. Despite trying to get similar numbers of respondents in each district, DHMTs in Malawi districts were too busy to participate in the interviews, and this has resulted in a relatively lower number of respondents in Malawi. A generic interview guide was developed and adapted for each country. The interviews focused on the decision-makers at district level, the (power) relations and collaborations between the actors involved in the district-level health system (within the district and between district, regional and national level) and the reasons behind these (power) relations and collaborations. The interview guide was pretested in each country and minor adaptations were made. Interviews were held in English, by trained and experienced research teams from Ghana, Malawi and Uganda. The interviews took approximately 1 hour. During fieldwork, the research teams held daily debriefings to discuss main findings, refine the interview guide and discuss data saturation. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Field notes were produced in each country.

Analysis

The field notes and transcripts were discussed in a meeting of the research consortium with researchers from the three study countries, and the UK, Ireland, Switzerland and the Netherlands teams in March 2018. After this, an inductive coding process in QSR NVivo v11 was undertaken by the first and second author and emerging themes were shared and discussed among all researchers. Narratives were developed according to the themes of a power framework and the writing was an iterative process between all co-authors.

Conceptual framework

To unravel how power dynamics between different actors at district, regional and national levels influence district health decision-making, the power framework developed by Arts and Van Tatenhove (Citation2004) was applied. This framework has been chosen as it has been previously used and operationalised in relation to policy making, and in particular in health policy dialogue in several African countries (Mwisongo et al., Citation2016) and it seemed to be appropriate to inform our data analysis. The framework distinguishes three forms of power: dispositional, structural and relational power (). Dispositional power refers to organisational rules and resources shaping the power of the agents (Arts & Van Tatenhove, Citation2004); Mwisongo further distinguishes three types of dispositional power: power based on hierarchy, resources, and knowledge (Mwisongo et al., Citation2016). Structural power is ‘concerned with how micro-societal structures shape and guide the conduct of individuals and agents’ (Mwisongo et al., Citation2016, p. 344). This type of power can be related to cultural or organisational norms or practices. For example, the cultural norm that it is not acceptable in Nigeria to interrupt when someone is speaking can result in unequal contributions during discussions (Mwisongo et al., Citation2016); the credibility of decision-makers or influencers being dependent on their characteristics (such as gender or ethnicity). Relational power is based on the idea that power is present in any social relationship (Arts & Van Tatenhove, Citation2004). It can be seen ‘as the dynamics between actors, resources, outcomes and interactions’ (Mwisongo et al., Citation2016, p. 339). Relational power can be a zero-sum game where certain actors have power at the expense of others but it can also be embodied as joint practices of actors resulting in certain outcomes through collective bargaining (Arts & Van Tatenhove, Citation2004). The different forms of power are interlinked and may influence each other (Arts & Van Tatenhove, Citation2004).

Table 3. Different types of power (Arts & Van Tatenhove, Citation2004).

Ethics

Ethical approval was provided by the LSTM Research Ethics Committee, the Ghana Health Service Ethics Review Committee, the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology, the ethics committee of the School of Public Health (Makerere University) and the National Commission for Science and Technology in Malawi. Interviews were conducted in private, informed consent processes were followed with written consent being provided. Permission was sought before recording of the interviews. Data were managed, stored, analysed and presented ensuring full confidentiality.

Results

The findings are presented on how different power dynamics shape health system decision-making at the district level. First, we describe the range of decision-makers at district, regional and national levels. Thereafter, we present the different forms of power observed with regards to health system decision-making at district level. For each power form (dispositional, structural and relational power), we first focus on the (power) dynamics within the district (between DHMT and District Council/District Assembly), then the (power) dynamics between district-, regional and national levels. Although the different forms of power are presented separately, we acknowledge that they are interrelated, which will be further considered in the discussion.

Decision-makers at district, regional and national levels

In Ghana, DHMT members identified the DDHS as the ultimate decision-maker on prioritisation of health areas and interventions, adaptation and implementation of policies, strategies and interventions developed at the national level, and scaling up of public health interventions at district level. Political decision-makers at the district level were only mentioned by local government actors but not by the DHMTs. In Malawi, participants were more divided in their ideas about decision-makers. Some participants identified the DHO as final decision-maker, whilst others saw the DHO as the one who influences the District Commissioner's decisions through technical guidance. Only a few participants described the District Council as a decision-making body. In Uganda, several interviewees voiced that it is difficult to identify one principal decision-maker at district level. They referred to several decision-makers depending on whether the decisions are political or administratively affiliated. Furthermore, in Malawi and Uganda, the entire DHMT was often mentioned as decision-maker at district level, whereas in Ghana this was solely the DDHS.

In Ghana, at the regional level, the Regional Health Director of GHS was mentioned as influencing decision-making at district level and in Malawi, none of the study participants identified the zonal level. Regarding the national-level influence on decision-making at district level, in both Ghana and Malawi, the Minister of Health was cited as the main influencer. In Uganda, the Director-General of the Ministry of Health was identified by some participants as the key influencer.

Decision-making and dispositional power

In all three countries, study participants made reference to dispositional power shaping health system decision-making at the district level. Three different forms of dispositional power will be discussed.

Dispositional power based on hierarchy

Within the district

Especially in Malawi and to a lesser extent in Uganda reference was made to dispositional power based on hierarchy within the district. In Ghana, no reference was made to this. In Malawi, several participants from different levels described that decentralisation has affected the DHMTs’ decision-making power as through devolution the District Councils (should) have more decision-making power. By delegation of authority from national level to the districts, and by moving authority across from DHMTs to District Councils, the DHMTs’ decision-making power within the district is affected. The DHMTs now need to report to and come to an agreement with the District Council. However, despite the District Council being the main decision-maker on paper, DHMTs, led by the DHO, were reported to by-pass the District Council and work directly with the national MoH, indicating the transitional state of decentralisation.

You find the DHO is reporting to the Ministry of Health instead of the District Council […]. They still feel the powers are within their respective ministries not with the District Council. (Ministry of Local Government, Malawi)

Malawian participants mentioned that only a few of the human resource management functions are decentralised to the District Council; hiring and dismissal are still done at national level. In Uganda, the changes in power from the DHMT towards the District Council were also discussed but to a lesser extent than in Malawi, where these changes have more recently taken place. Ugandan participants from different levels described that the DHMT falls under the District Council and reports to the CAO. In addition, the political actors of the district were said to have substantial influence on the health decisions made through the District Health Committee, which limited the decision space of the DHMTs. Furthermore, in Uganda, the influence of hierarchy on district-level decision-making was mentioned by some participants from different levels but did not necessarily follow the hierarchy of the health system structure itself; it seemed to be present between certain individuals within an organisation/institutes within the district. Some participants specifically voiced that is difficult to speak against or oppose your superior.

The Resident District Commissioner comes up with something and says please this is what the policy says. We normally don't want to oppose. (Admin district level, Uganda)

Between the levels in the health system – district, regional and national

With regard to the (power) relations between district, regional and national levels, strong reference was made in Ghana and Malawi and to a lesser extent in Uganda to dispositional power based on hierarchy. Strong hierarchy in the health sector is pervasive in Ghana and to a lesser extent in Malawi and was mentioned by many study participants from different levels. In Malawi, several participants mentioned that much of the decision-making power is with the national-level Ministry of Health instead of the district level. This is because of the existing hierarchy: they are the highest authority within the health sector. In Ghana, all participants reported that despite devolution, DHMTs’ decision-making was heavily influenced by the higher levels in the health system. The national-level GHS retained hierarchical power over the regional health administration, which again had hierarchical power over the DHMT. Lines of influence in decision-making from actors in lower positions towards actors in higher positions were not described. The Director-General of the GHS in Ghana was said to have considerable power and was often described as the final decision-maker for implementation of a health intervention and/or its scale-up, without much say by the DHMTs. GHS is in turn influenced by their higher authority, which is the Minister of Health.

We (DHMT members) are all working under the regional director in the region and the Regional Director cannot do anything without directions from the Director-General. After that, the Regional Director will instruct us at the lower levels and we will abide. The District Director is working under the Regional Director so takes orders from there. (DHMT member, Ghana)

The hierarchy in Ghana was referred to as rigid and important to adhere to. No participant mentioned problems with this, with the majority describing generally good working relationships between district, regional and national level (besides a few personality issues), because decisions are made and influenced according to the hierarchy and everybody knows whom to report to.

If the region is calling you on this day for a program and you also have a program to carry out in the district, you have to postpone yours. Once it's for region by all means you have to be there, the region does its own thing, they cannot change their program. (DHMT member, Ghana)

In Ghana and Malawi, because the national level had greater hierarchical power, the DHMTs described having limited decision space. The districts, and more specifically the DHMTs, were often referred to as implementers, whereas the national level had the mandate and the power to change and develop policies, and decide on their scale-up. In Malawi and Ghana, some DHMT members described that the development of policies included input from the districts, while others reported policies being imposed from above. A Malawian participant from the local government described that actors at national level often behave like ‘bosses’: instructing how the lower level should do certain things, but not understanding the reality on the ground.

Most of the interventions initiated at the national level do not meet the districts because planning is done for districts and not with the districts. (Local Government representative, Malawi)

Dispositional power based on resources

Within the district

Regarding (power) dynamics within the district, in both Uganda and Malawi, many participants from the DHMTs and District Councils described that district-level decision-making power is restricted due to lack of financial resources, despite the District Assemblies or Councils holding the district budget. In Uganda, many study participants indicated that funding coming to the districts from the national level is often in the form of conditional grants. These are grants that are transferred from national level to local governments with a specific purpose and may not be used for other purposes, and that therefore the national level has the actual power.

That is why they want to call the conditional grant, you cannot say you can control (… .) when you are still under the conditional grant. (Local Government representative, Uganda)

In Ghana, power dynamics within the district seemed substantially different from those in Uganda and Malawi. Participants, from both the DHMT and District Assembly, described minimal collaboration between the DHMTs and the District Assembly and that if collaboration is there, it is limited to borrowing cars, construction of Community-Based Health Planning and Services buildings and vaccination campaigns. The DHMTs were said to have a stronger link with the central- and regional-level GHS than with the District Assembly, because funding came from the upper levels. In Ghana and Malawi, some participants mentioned that donors also have an impact on power dynamics because they hold financial resources; participants in Uganda referred less to this. One district-level participant from Malawi described that donors sometimes decide on implementation of projects without consulting the district authorities.

Between the levels in the health system – district, regional and national

Dispositional power based on resources was also visible with regard to the (power) relations between district, regional and national levels. A Malawian participant reported that national-level members of parliament have recently been allowed to vote in the District Council. He described this as a challenge, as the members of parliament have financial resources with which they easily influence decisions made at the Council. District-level participants from Malawi and Uganda reported that national-level stakeholders are resistant to decentralisation, as their control over financial resources diminishes, and as a result decentralisation is not implemented as fully as it should be. In Malawi, district participants stated they do not have financial resources allocated from national level to their identified district priorities. Most of the participants in Ghana, Malawi and Uganda discussed that there is little revenue collection within the districts.

Dispositional power based on knowledge

Within the district

Dispositional power based on knowledge was mainly referred to within the district. In the three countries, senior members of the DHMTs were recognised as having power attributable to their levels of knowledge or expertise: these were the DHOs (Uganda and Malawi) and the DDHSs (Ghana). In Ghana, the DDHS was seen as the main decision-maker related to district health issues, whereas in Uganda and Malawi, the DHMT, headed by the DHO, was said to substantially influence the district's political decision-makers by providing technical guidance.

Despite this dispositional power, in all countries, participants described how DHMTs have limited knowledge and capacity to lobby for funding, to understand policies and to execute monitoring and evaluation and project management activities. In Malawi, some participants linked this lack of capacity to high staff turnover and shortage of human resources, resulting in some people holding positions that are not in line with the required educational level. This was said to negatively influence DHMTs’ power in decision-making.

Decision-making and structural power

Structural power in relation to district decision making was mainly described by district-level respondents. However, more general statements about structural power were provided by participants at all levels. In all three countries, examples of structural power were provided about people in decision-making positions giving preferential treatment towards certain persons or groups. This mostly involved giving jobs and promotions to family members and friends without considering the required qualifications for the job. Another form of favouritism referred to by some Malawian and Ghanaian participants was tribalism. In Ghana, participants reported that political parties are affiliated with ethnicity and therefore voting for a certain party was believed to favour their ethnic groups/tribes. While this seemed to have little impact on health system decision-making at district level because of the limited role of the political body, a national-level NGO participant in Ghana reported that certain ethnicities are dominant in certain areas, and therefore people of that ethnicity who work in the administrative and political bodies, have more decision-making power. In Malawi, it was recognised that tribalism could influence decision-making, but that the region or district of origin was more important, for example, decisions within the DHMTs are more easily taken when people come from the same region. In addition, some Malawian district-level participants reported that a health worker coming from the same region or district as a DHMT member is treated better by this DHMT member than those coming from other regions or districts.

We have a Medical Assistant from District X, he is a drunkard to the extent that they carry him on a wheelbarrow and he stays three or four days without going to work and Healthcare Advisory Committee has been coming to complain but we are not doing anything on that issue just because he is from District X but we had someone here he was suspended but he had a similar situation [but was from another district]. (DHMT Member, Malawi)

Gender was described as influencing perceptions of credibility and therefore power. In all countries, several participants voiced that in general men are seen as more credible decision-makers than women. For example, in Ghana, a participant discussed that men were described as more powerful than women, based on beliefs that men are the main working force and therefore have power over women. In Malawi, some observed that decision-makers at the Council level were more often male than female and as a result, the decisions made may be more in favour of men than women. One Malawian participant from the District Council described how women in managerial positions do not always believe in themselves and that therefore they may not always make the right decisions. However, there was also one national-level Ministry of Health participant in Malawi who described that people are more tolerant and responsive to a female manager.

In Ghana and Malawi, some participants also referenced age as a characteristic influencing the credibility and power of a decision-maker. In Malawi, it was described that the zonal level does not have much power because most of the staff are young.

A DHO, he should be the one with a potbelly and should always wear a jacket and tie, he shouldn't interact with people and shouldn't be seen to be stopping for anyone; he should be scary and then we say yes that's the DHO but when we see someone young we say will this person help us? (Ministry of Health, Malawi)

Decision-making and relational power

In the three countries, politics and the allowance culture were used in negotiation and were perceived as shaping district-level decision making.

Politics

When discussing district-level decision-making, there was a frequent reference to ‘politics’, both within the district and between district, regional and national levels.

Within the districts

Participants often referred to politics within the districts when discussing the power dynamics and relationships between the administrative and political bodies. In Malawi and Uganda, several participants, mostly DHMT members, described that these relationships are sometimes challenging because of the different interests that these actors have. They explained that politicians have power because they represent the community, but in reality they only focus on their own interests of ensuring votes, pleasing their voters and considering how decisions may are affect their political party staying in power. In contrast, DHMT members reported that administrative actors focus more on improving ‘the situation on the ground’.

Okay well the counsellors are accountable to the rural masses that is a rule of thumb but the way things are done here it looks like the counsellors have made themselves gods, they pretend that they are taking the best interest of people at heart but it's something that they want to implement in order to make a political mileage. (Local Government, Malawi)

In Uganda, a DHMT member mentioned that district-level politicians could also positively influence health system decision-making. When an intervention shows positive outcomes, politicians can use this in their political campaign and therefore they are willing to support the implementation of certain initiatives. Another Ugandan DHMT member described that actors from the ruling party sometimes try to ensure their power by not allowing actors from other political parties to perform activities in the communities because they are afraid that they will undermine the government campaign. A participant from a district NGO described that when someone is politically linked, he or she can engage in certain behaviour that normally would not be accepted.

There are districts where actually the lowest cadres may have more authority […] because they are politically attached, the sub-county chief says “I don't want that woman in the facility” then they’ll have to transfer that person. (Implementing partner at district level, Uganda)

In Ghana, less involvement of politics was described in health decision-making, because of limited reported influence of the District Assembly in health.

Between the levels in the health system – district, regional and national

Regarding (power) relations between national, regional and district levels, many participants from all countries highlighted the need to ensure political support at national level for policy development and implementation. If there is limited political support for a health policy intervention, the political leaders have the power to impede implementation. It is very important to ensure that new policies or projects at district level are aligned with the priorities of the political actors.

The political issue might be first addressed because if it is not in line with the ruling government manifesto or what they want to achieve, it will never see the light of day. Even before a policy is developed, it has to be in line with the political leader power. (National level – GHS, Ghana)

Allowance culture

Within district

In all three countries, many participants from different levels and especially within the districts, referred to the ‘allowance culture’ through which people can exercise power by saying that if they do not get a (sufficiently high) allowance, they will not support a certain decision. Less references was made to this between the levels in the health system (district, regional and national levels). The majority of participants mentioned that if district actors involved in decision making do not receive additional allowances (on top of their salaries) to take part in specific activities and meetings (at district and national level), they will not participate in decision-making or be committed to implement projects.

Just know people are intoxicated, they have a lot of toxins, they are corrupt, they are money minded, without facilitation as they said, things will not move to the expectations. (Admin at the district level, Uganda)

In Uganda and Malawi, several participants at different levels described that district actors involved in decision making are primarily motivated by allowances and often go to workshops where the allowance is the highest. In Uganda, a DHMT member described that projects are seen as moneymaking machines because of these allowances.

Discussion

This qualitative study aimed to explore how district-level health system decision-making is shaped by power dynamics between different actors at district, regional and national levels in different decentralised contexts in Ghana, Malawi and Uganda. We discuss three areas: how the stage and type of decentralisation affects the types of power, the inter-relationship between the forms of power and decentralisation and opportunities for increased decision-making at district level.

Stage and type of decentralisation affects the types of power

District-level health system decision-making is shaped by three different forms of power (dispositional, relational and structural power). Depending upon the stage and type of decentralisation, certain forms of power were more predominant than others. Devolution in Malawi and Uganda has made health system decision-making within the district be mainly influenced by the district political body (because of relational and dispositional power based on resources) and this shift in power has the potential to make decision-making and relationships more political (Wickremasinghe et al., Citation2016). Henriksson (Citation2017) also highlighted that DHMTs in Uganda perceive a lack of local decision space, because politicians have the power in the districts and are the final decision-makers regarding the district work plan.

While on paper health system decision-making is decentralised, in reality, the national-level Ministry of Health has substantial influence on district-level health system decision-making in Ghana and Malawi and to a lesser extent in Uganda, because of the dispositional power that they have based on financial resources and hierarchical position. In Ghana, our results indicate stagnated or incomplete decentralisation. DHMTs have little decision-making power in comparison with the Ministry of Health and GHS at national level and DHMTs have limited interaction with the District Assembly. This is in line with the findings of Kwamie et al. (Citation2015b), where DHMTs in Ghana have limited decision space because of the tendency towards centralised decision-making as a result of incomplete fiscal and political decentralisation. In Malawi and Uganda, earmarked funding from national level also limited decision space at district level. District-level health system decision-making was influenced by structural power, due to the prevailing patronage relationships. We found that the origin, ethnicity and gender of decision-makers and their influencers affect the distribution of power and the choices that decision-makers make.

Inter-relationship of types of power

It is important to note that the different forms of power were interrelated. For example, relational power that emerges during negotiation can be influenced by who a person is (structural power, related to how credible others think the person is, based on characteristics that are important according to social-cultural norms, such as ethnicity, gender or age) and what the person represents in terms of knowledge, resources and position (dispositional power). Although in the framework, no differentiation is made with regard to the weight/importance of certain forms of power, in this study, participants from different levels strongly reported dispositional power based on hierarchy and resources as being important in decision making. This might indicate that dispositional power strongly influences district-health system decision making, which again might be reinforced by structural power or other forms of dispositional and relational power. For example, a DHMT member who has a position of authority will be supported by other DHMT members who are from the same district or ethnic group. This will enable her or him to have more decision-making power.

Decentralisation and opportunities for increased decision-making at district level

The substantial influence of the national level in all three countries and the political influence of the district political bodies through devolution in Uganda and Malawi resulted in a narrow decision space for DHMTs. As a result, DHMTs in all three countries expressed feelings of disempowerment, which was aggravated by resource-constraint contexts. DHMTs had little decision-making power regarding health priority setting, contextualisation of policies and decisions on scale-up of interventions. Tetui et al. (Citation2016) also highlighted that in Uganda, negative political influence within the district system disempowered DHMT members and could even block their ability to manage.

Despite the feelings of disempowerment, decentralisation also gives way to opportunities for increased power in health system decision-making of DHMTs in the three countries. First, because of their unique knowledge and insights into the health realities of their district, DHMTs can use their dispositional power both in relation to national and district-level stakeholders, such as the political body, to advocate for the implementation or scale-up of certain health interventions. Second, DHMT members may exercise structural power through their individual characteristics such as their gender or ethnicity. However, the sole use of structural power might not be enough nor desirable to steer implementation or scale-up of specific interventions, partly because of regular transfers of DHMT members. Third, DHMT members could exercise relational power through deliberately not participating in activities or not supporting certain decisions of those who are more powerful, such as the regional/national-level Ministry of Health or donors. Using this type of relational power, however, is difficult in hierarchical settings and in contexts with limited resources and donors. Fourth, through collaborations between DHMTs with the District Assembly/Council, district actors, including DHMTs, can have more power in health system decision-making in relation to national actors. The DHMTs can increase relational power by joint activities with the District Assembly/Council to achieve certain outcomes using collective bargaining (Arts & Van Tatenhove, Citation2004). A study in the Philippines of Liwanag and Wyss (Citation2018) identified good working relationships between the different (administrative and political) district actors as a condition for decentralisation to lead to health system improvements. When reflecting upon the position of DHMTs versus the District Assembly/Council in decentralised contexts, it is important to realise that power is not always a negative form of domination or resistance, but can also take forms of collaboration and transformation (Gaventa, Citation2006). For example, in this study local politicians sometimes positively influenced health system decision-making at district level when they expected positive outcomes that could assist them in their further career. Power is a difficult concept, especially when operationalising it for research (Mwisongo et al., Citation2016). The framework of Arts and Van Tatenhove (Citation2004) helped to structure the analysis of the different forms of power involved in district-level health system decision-making. As the different forms of power are interrelated, it can be challenging to assess what power is used when and by whom. It is however important to reflect on these power dynamics in district-level decision-making as it is critical to better understanding what and how this decision making can be influenced.

Strengths and limitations

The high number of interviews (82) helped to generate rich data, which created insight into the range of processes at play from different perspectives. The continuous discussions within our multi-country team enabled the analysis process. In this study we focused on the power dynamics between the DHMT and actors at district, regional and national levels, we did not explore the power relationships within the DHMTs. In addition, we did not focus on the individual technical or leadership competencies, although these may play an important role in district-level health system decision-making and it is therefore recommended to address these topics in future research.

It needs to be acknowledged that DHMTs are part of a complex environment, in which different actors, factors and the reality of decentralisation influence their decision-making power. Our findings show the importance of gaining an understanding of power dynamics. Reflection on power dynamics with regard to district-level health decision-making may help DHMTs to broaden and make better use their decision-making power when implementing and scaling up health interventions.

Acknowledgments

The study presented in this article is performed as part of the PERFORM2Scale project. PERFORM2Scale is a 5-year international research consortium aiming to develop and evaluate a sustainable approach to scaling up a district-level management strengthening intervention in different and changing contexts. This work was supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant number 733360). The authors would like to acknowledge all participants who gave their time to be interviewed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Susan E. Bulthuis, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The implementation research consortium consists of the following partners: (1) School of Public Health, University of Ghana, (2) Reach Trust, Malawi, (3)Makerere School of Public Health, Uganda, (4) Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, (5) Centre for Global Health, Trinity College, Ireland, (6) Maynooth University, Ireland, (7) Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, UK, (8) Anthrologica, UK, (9) KIT Royal Tropical Institute, Netherlands.

2 In Ghana, the interviews took place in the following districts: Suhum, Yili Krobo and Fanteakwa. In Malawi, they took place in Dowa, Ntchisi, Salima, Lilongwe, Dedza and Ntcheu and in Uganda in Luwero, Wakiso and Nakaseke. Due to privacy reasons, no details on the study participants are provided in the paper.

References

- Alonso-Garbayo, A., Raven, J., Theobald, S., Ssengooba, F., Nattimba, M., & Martineau, T. (2017). Decision space for health workforce management in decentralized settings: A case study in Uganda. Health Policy and Planning, 32(suppl_3), iii59–iii66. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czx116

- Arts, B., & Van Tatenhove, J. (2004). Policy and power: A conceptual framework between the ‘old’and ‘new’policy idioms. Policy Sciences, 37(3-4), 339–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-005-0156-9

- Borghi, J., Munthali, S., Million, L. B., & Martinez-Alvarez, M. (2017). Health financing at district level in Malawi: An analysis of the distribution of funds at two points in time. Health Policy and Planning, 33(1), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czx130

- Bossert, T. (1997). Decentralization of health systems: decision space, innovation and performance. Data for Decision Making (DDM) Working Paper.

- Bossert, T., & Beauvais, J. (2002). Decentralization of health systems in Ghana, Zambia, Uganda and the Philippines: A comparative analysis of decision space. Health Policy and Planning, 17(1), 14–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/17.1.14

- Couttolenc, B. F. (2012). Decentralization and governance in the Ghana health sector. The World Bank.

- Doh, D. (2017). Staff quality and service delivery: Evaluating two Ghanaian District assemblies.

- Doherty, T., Tran, N., Sanders, D., Dalglish, S. L., Hipgrave, D., Rasanathan, K., … Mason, E. (2018). Role of district health management teams in child health strategies. British Medical Journal, 362, k2823. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2823

- Erasmus, E., & Gilson, L. (2008). How to start thinking about investigating power in the organizational settings of policy implementation. Health Policy and Planning, 23(5), 361–368. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czn021

- Gaventa, J. (2006). Finding the spaces for change: A power analysis. Institute of Development Studies Bulletin, 37(6), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2006.tb00320.x

- GhanaDistricts. (2019, 04-10-2019). Summary of 260 MMDAs. http://www.ghanadistricts.com/Home/LinkData/8239

- Government of Malawi. (2013). Guidebook on the local government system in Malawi. Lilongwe, Malawi.

- Hansen, K. M., & Ejersbo, N. (2002). The relationship between politicians and administrators–a logic of disharmony. Public Administration, 80(4), 733–750. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9299.00326

- Henriksson, D. K. (2017). Health systems bottlenecks and evidence-based district health planning: Experiences from the district health system in Uganda. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis.

- Jagero, N., Kwandayi, H. H., & Longwe, A. (2014). Challenges of decentralization in Malawi. International Journal of Management Sciences, 2(7), 315–322.

- Jeppsson, A. (2004). Decentralization and national health policy implementation in Uganda – A problematic process. Department of Community Medicine, Malmö University Hospital.

- Kapiriri, L., Norheim, O. F., & Heggenhougen, K. (2003). Public participation in health planning and priority setting at the district level in Uganda. Health Policy and Planning, 18(2), 205–213. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czg025

- Kathyola, J. (2010). The political-administrative interface The key to good public sector governance and effectiveness in Commonwealth Africa. Commonwealth Good Governance.

- Kwamie, A., Agyepong, I. A., & Van Dijk, H. (2015a). What governs district manager decision making? A case study of complex leadership in Dangme West district, Ghana. Health Systems & Reform, 1(2), 167–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/23288604.2015.1032475

- Kwamie, A., van Dijk, H., Ansah, E. K., & Agyepong, I. A. (2015b). The path dependence of district manager decision-space in Ghana. Health Policy and Planning, 31(3), 356–366. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czv069

- Liwanag, H. J., & Wyss, K. (2018). What conditions enable decentralization to improve the health system? Qualitative analysis of perspectives on decision space after 25 years of devolution in the Philippines. Public Library of Science One, 13(11), e0206809. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0206809.

- McCollum, R., Taegtmeyer, M., Otiso, L., Muturi, N., Barasa, E., Molyneux, S., … Theobald, S. (2018). “Sometimes it is difficult for us to stand up and change this”: an analysis of power within priority-setting for health following devolution in Kenya. Bio Med Central Health Services Research, 18(1), 906. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3706-5

- Mutemwa, R. I. (2005). HMIS and decision-making in Zambia: Re-thinking information solutions for district health management in decentralized health systems. Health Policy and Planning, 21(1), 40–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czj003

- Mwisongo, A., Nabyonga-Orem, J., Yao, T., & Dovlo, D. (2016). The role of power in health policy dialogues: Lessons from African countries. Bio Med Central Health Services Research, 16(4), 213. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1456-9

- Pretorius, M. C. (2017). The influence of political and administrative interaction on municipal service delivery in selected municipalities in the free state province. Central University of Technology, Free State.

- Sumah, A. M., & Baatiema, L. (2019). Decentralisation and management of human resource for health in the health system of Ghana: A decision space analysis. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 8(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2018.88

- Tambulasi, R. I. C., & Alawattage, C. (2007). Who is fooling who? Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 3(3), 302–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/18325910710820319doi:10.1108/18325910710820319

- Tettey, W. J., Puplampu, K. P., & Berman, B. J. (2003). Critical perspectives in politics and socio-economic development in Ghana (Vol. 6). Brill.

- Tetui, M., Hurtig, A.-K., Ekirpa-Kiracho, E., Kiwanuka, S. N., & Coe, A.-B. (2016). Building a competent health manager at district level: A grounded theory study from Eastern Uganda. Bio Med Central Health Services Research, 16(1), 665. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1918-0

- Tuckett, A. G. (2004). Qualitative research sampling: The very real complexities. Nurse Researcher, 12(1), 47–61. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr2004.07.12.1.47.c5930

- Uganda Legal Information Institute. (1997). Local Governments Act 1997. https://ulii.org/ug/legislation/consolidated-act/243

- VeneKlasen, L., Miller, V., Budlender, D., & Clark, C. (2002). A new weave of power, people & politics: The action guide for advocacy and citizen participation. World Neighbors Oklahoma City.

- Waiswa, P., O’Connell, T., Bagenda, D., Mullachery, P., Mpanga, F., Henriksson, D. K., … Peterson, S. S. (2016). Community and District Empowerment for Scale-up (CODES): a complex district-level management intervention to improve child survival in Uganda: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 17(1), 135. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1241-4

- Wickremasinghe, D., Hashmi, I. E., Schellenberg, J., & Avan, B. I. (2016). District decision-making for health in low-income settings: A systematic literature review. Health Policy and Planning, 31(suppl_2), ii12–ii24. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czv124