ABSTRACT

While the COVID-19 pandemic now affects the entire world, countries have had diverse responses. Some responded faster than others, with considerable variations in strategy. After securing border control, primary health care approaches (public health and primary care) attempt to mitigate spread through public education to reduce person-to-person contact (hygiene and physical distancing measures, lockdown procedures), triaging of cases by severity, COVID-19 testing, and contact-tracing. An international survey of primary care experts’ perspectives about their country’s national responseswas conducted April to early May 2020. This mixed method paper reports on whether they perceived that their country’s decision-making and pandemic response was primarily driven by medical facts, economic models, or political ideals; initially intended to develop herd immunity or flatten the curve, and the level of decision-making authority (federal, state, regional). Correlations with country-level death rates and implications of political forces and processes in shaping a country’s pandemic response are presented and discussed, informed by our data and by the literature. The intersection of political decision-making, public health/primary care policies and economic strategies is analysed to explore implications of COVID-19’s impact on countries with different levels of social and economic development.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

In 2015, Bill Gates alerted the world that a pandemic was coming, and that we needed to get ready (Gates, Citation2015). He prophesised that an airborne viral infection could cause millions of deaths and devastate the global economy. He advocated for a global alert surveillance system to track the spread of disease, a prepared trained workforce, strong primary health care (PHC) in poorer countries which might be hit harder, and research and development technology for rapid development of diagnostics and vaccines.

Three years later, in the New England Journal of Medicine, Ron Klain identified that ‘social trends, political movements and policy failures’ heighten the risk of a catastrophic pandemic (Klain, Citation2018). He opined that the rise of national isolationism, especially in high-income countries, the growing trend of anti-scientific thinking and anti-vaccination movements, and the disease-related danger from climate change forcing wildlife and humans into closer proximity, all escalated the risk of a global pandemic. He called for medical leaders to take on the difficult challenge of shaping pandemic plans and policies.

As we know, this advice largely went unheeded. In December 2019, the COVID-19 disease emerged in Wuhan, China, found to be caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). COVID-19 spread rapidly, with cases recorded in 19 countries by 30 January 2020. WHO officially declared the spread of COVID-19 a pandemic on 11 March 2020.

While COVID-19 now affects the entire world, countries have had diverse responses. Some responded faster than others, with considerable variation in strategy. Some countries initially considered letting the virus run its course, in order to develop indirect protection through herd immunity (Fine et al., Citation2011). Producing widespread SARS-CoV-2 immunity can only occur with mass application of a safe and effective vaccine, or sufficient natural immunity in the population over time. However, exposing low-risk young people with no comorbidities while protecting the vulnerable will not achieve herd immunity, and viral spread will continue. A large percentage of the population needs to be immune to prevent onward transmission, not just clinical disease, as asymptomatic people can still be contagious and spread the infection (Altmann et al., Citation2020).

If left unchecked, the spread of SARS-CoV-2 can rapidly not only overwhelm a health system, resulting in deaths from COVID-19, but also increase all-cause mortality. This is particularly devastating for low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) with limited hospital capacity, poor primary care and public health infrastructure, along with vulnerable populations, such as migrant workers, the homeless, elderly or imprisoned (Randolph & Barreiro, Citation2020).

In early March, the United Kingdom (UK) considered the herd immunity strategy (Stewart & Busby, Citation2020), but then tardily implemented lockdown. Sweden allowed controlling spread of the virus, leaving strategies to reduce transmission to individual responsibility (Anderson, Citation2020). Although varying in stringency, eventually all countries adopted some form of strategy to flatten the curve, delaying the peak of active cases while increasing the capacity of health services to manage surging demand.

The only selective pressure on SARS-CoV-2 is transmission – stop transmission and you stop the virus. Preventing person-to-person transmission includes use of personal protective equipment by frontline workers and face masks by the public, physical distancing between individuals, closure of events and locations where people congregate, hand washing and surface cleaning to prevent fomite spread, and identification and quarantining of infected cases identified at borders and through contact tracing. Once there is exponential rise in the number of cases and deaths, the most successful approach has been isolating the population (Yuan et al., Citation2020), with the most stringent measures requiring all but essential workers confined to their homes, except to purchase food or receive medical care.

Isolation strategies that reduce the health burden of direct morbidity and mortality from COVID-19 also reduce economic activity. Preventing people gathering and confining them to their homes has downstream repercussions on many businesses, including those dealing with transport, hospitality, entertainment and trade (Lenzen et al., Citation2020). Closing borders has serious consequences when tourism plays a major economic role, not to mention the potential impact on international relations. Country strategies, therefore, must balance the reduction in disease and death from COVID-19 with the direct and indirect effects on the economy, political fall-out, increased morbidity due to reduced access to general healthcare services, and the social effects due to isolation and unemployment.

A country’s pandemic strategy may be politically mediated. Isolating people in their homes, and protective measures, such as mask-wearing, can be considered infringements on individual rights. In some democracies, mandated behavioural control may be viewed as restrictions on liberty, and open debate over individual freedoms versus collective well-being. In such cases, the primary driver for politicians may be pleasing their voting constituency, as well as potentially supporting their re-election. Alternatively, authoritarian states may limit the internal and external flow of valid information, whereby the prevalence of COVID-19 infection and mortality goes under-reported, to make their regime look good (Greer et al., Citation2020). Authoritarian leaders may institute emergency measures, such as mobilisation of state power and far-reaching surveillance systems, to further consolidate their power base.

The relevant level of decision-making authority is also important. Federal states may devolve responsibility to sub-national governments, leading to a nationally fragmented response (Greer et al., Citation2020). On the other hand, the public may have more trust in their local leaders, resulting in increased social compliance.

Our international study of primary care experts sought their perspectives on whether their country had a pre-existing plan, and whether the decision-making and pandemic response in their respective countries was primarily driven by medical facts, economic models, or political ideals, as well as the level of decision-making authority. We hypothesised that having and executing a pandemic plan, a national-level response, primarily based on health considerations and aimed at flattening the curve, would correlate with lower death-rates from COVID-19.

The aim of this paper is to correlate these measures with country-level death rates, augmented by the rich text responses provided by our respondents, and assess the implications of political pressure in shaping a country’s pandemic response.

Materials and methods

These analyses were conducted as part of a broader international project which solicited primary care experts’ perceptions of their respective countries’ primary care strength, pandemic plan implementation, border control measures, movement restriction and testing correlated against COVID-19 mortality rates. Full methodological details are published elsewhere (Goodyear-Smith et al., Citation2020). This mixed-method paper provides analysis of respondents’ perceptions on their country’s pandemic plan and political decision-making correlated with their country’s current mortality rate. Ethical approval was granted for three years on 9 April 2020 by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (UAHPEC), Ref number 024557.

Setting and participants

We used a convenience sample of international primary care experts (clinicians, researchers, and policy-makers) employing the researchers’ collective networks plus a snowball recruitment strategy. The online anonymous survey, available in English and Spanish from 15 April to 4 May 2020, comprised 34 questions to better understand how preparedness and the response to the pandemic was perceived by the survey participants from a primary care perspective (Supplementary Figure 1).

This paper focuses specifically on the five survey questions which the researchers considered to be closely related to the politics associated with pandemics and authority and decision-making measures. Respondents were asked to rank the importance of medical, economic and political impact on the pandemic response decision-making in their country; the level (national, state or local) which the majority of the public saw as having ultimate authority in decision-making; indicate whether they felt a pandemic plan existed and was executed, and were invited to elaborate on responses in free text. Furthermore, they were asked whether their country’s initial response was primarily intended to facilitate herd immunity or flatten the curve.

The original study consisted of 1035 completed responses from 111 countries. The number of responses from each country varied from a single respondent (34 countries) to 163 respondents (Australia) (Supplementary Table 1). Thirty-eight countries with five or more responses accounted for 897 (87%) of all responses. Countries from all world regions and economic tiers were represented. The majority (57%) of respondents were female; 51% were aged between 30 and 49 and 41% between 50 and 69 years old; 756 (73%) identified themselves as primary care clinicians, 175 (17%) as academics, 60 (6%) as policy-makers, with the remainder (4%) as ‘other’. The English version was completed by 954 (92%) and Spanish by 81 (8%). The remainder of this paper will report results from the 38 countries with at least five respondents to protect the anonymity of participants from countries with fewer respondents, and to ensure adequate representation of perspectives from each country.

Response variable

The response variable is defined as the cumulative death rate for a country per 1,000,000 population. For this current analysis, country-level data on mortality rates from COVID-19 were extracted from an online source on 11 September 2020 (Johns Hopkins University of Medicine, Citation2020). Every measure of mortality from COVID-19 has limitations. Cases and deaths may be under-reported e.g. Brazil (Veiga e Silva et al., Citation2020), or where there is extensive testing strategy, may be accurately or even over-reported e.g. Belgium (Molenberghs et al., Citation2020). Because the pandemic reached countries at different times, our earlier paper used a country’s maximum death rate on a 7-day moving average basis to quantify the severity of the pandemic in a country at its worst point, to compensate for these differing trajectories (Goodyear-Smith et al., Citation2020). However, COVID-19 has now spread to nearly every country, with rising case numbers, and in some cases second waves of infection, hence cumulative death rates were used in this current analysis to allow for more realistic comparisons. The intention of the study is to assess the relationship between countries’ health systems and preparedness as it existed before or at the start of the pandemic (January 2020), with the eventual outcome, as measured by COVID-19 deaths. As such, the later in the pandemic the cumulative deaths per capita measure is taken, the better it will approximate the eventual outcome of interest.

Quantitative analyses

Individual participant responses were aggregated to country-level responses to perform bivariate analysis with country-level outcomes in cases where there were five or more respondents. There were 38 countries in this cohort, including China. However, respondents came from both Mainland China and Hong Kong, which have different regimes and death-rates (3.37 and 1.32/million, respectively). Because we could not determine respondents’ origins, we excluded China from all correlation analyses.

For multiple-choice answers, the country-level response was calculated as the proportion of respondents from each country who selected each response. For ranking questions, the country-level response was calculated as the proportion of respondents who ranked each choice as most important.

The relationship between decision-making and mortality was explored by comparing the cumulative mortality rates observed to date for each country, with bivariate analyses to determine the correlations. Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated for pairs of variables. Statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.6.3.

Qualitative analyses

The survey provided options for open-text responses for the question addressing the priority of governmental decision-making and general experiences around their country dealing with COVID-19. Thematic analysis was conducted by four members of the research team, led by an experienced qualitative methodologist. A codebook, using a priori codes, was established using the survey questions and initial hypotheses of the research project. Emerging codes, during the initial coding, were discussed and implemented using a constant comparative approach. The four researchers reviewed, discussed, and refined coded survey entries and code definitions to reach inter-reader reliability.

There were 1,075 unique responses, from 591 respondents, representing 103 of the 111 countries. These were compiled in Excel for analysis. Spanish survey open text entries were first translated through Google Translate and then checked by a research team member proficient in the language. Only quotes submitted in English were used in this paper. Spanish entries were not excluded, but none provided data we chose to use to illustrate the narrative of the paper. Quotes presented in this paper were slightly adjusted to correct spelling and typographical mistakes, while maintaining the substance of the message. Only quotes from the 37 countries in which quantitative analysis are provided, were used, to limit potential outlier perspectives of one respondent speaking for an entire country.

Results

Results are presented by examining cumulative death rates by country in comparison to whether survey respondents believed their country had a pandemic plan in place and whether it was executed. Illustrative quotes are provided to further the analysis by exploring themes of medical, political, and economic decision-making, as well as the perception of level of authority, and effectiveness of national leadership, including attempts to flatten the curve versus reaching herd immunity.

Relative mortality

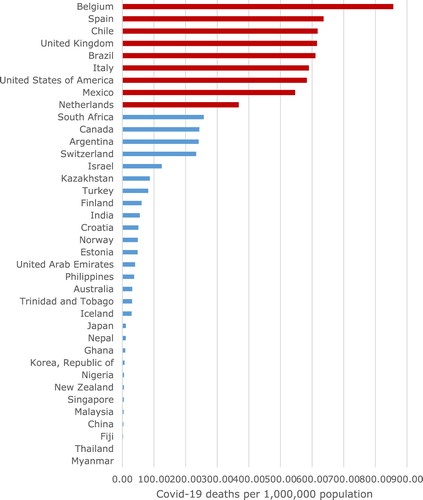

For the 38 countries, the cumulative death rate from COVID-19 (expressed per 1,000,000 population) ranged from 0.26 (Myanmar) to 855.68 (Belgium) (). Those highlighted in red are above the 75th percentile of death rate for these 38 countries.

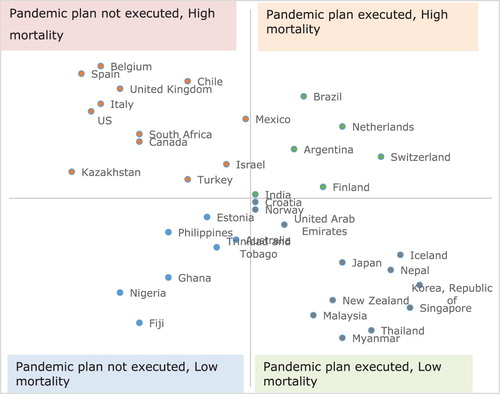

Relationship between mortality and pandemic plan

Respondents were asked whether their country had a published national strategy for dealing with pandemics as of 1 January 2020, and whether such a strategy was executed during the response. The scatter plot in shows each country’s relative ranking among the 37 countries in terms of mortality on the vertical axis, and the proportion of respondents who believed that a pandemic strategy existed and was executed on the horizontal axis. Countries in the top-left quadrant experienced relatively high mortality and ranked low in terms of respondents believing that a pandemic strategy existed and was executed. Conversely, countries in the bottom-right quadrant experienced relatively low mortality and ranked high in terms of respondents believing that a pandemic strategy existed and was executed. Conversely, countries in the bottom-right quadrant experienced relatively low mortality and ranked high in terms of respondents believing that a pandemic strategy existed and was executed. There is a moderately strong correlation between the extent to which a country’s respondents felt a national pandemic strategic plan existed and was initially executed, and lower COVID-related mortality, rs = −0.5039 (, also Supplementary Figure 2).

Using the Plan/Mortality quadrants in , provides open-text comments to further illustrate these findings. Respondents in countries with higher death rates discussed the importance of executing a plan, not only inclusive of primary health care (e.g. Belgium), but also appropriate to their country’s health care system and geopolitical context (e.g. Brazil). Respondents from Belgium, which had an early and high death rate (855.68/million), indicated their country had a plan but was initially not well implemented, and the PHC response was not mobilised. The situation was similar in Spain (635.21/million).

Table 1. Illustrative quotes from countries with and without executed plan with high and low death-rates.

In contrast, in Brazil, also with a high death rate (609.34/million), respondents generally thought that a plan had been executed. However, this may have depended on the part of Brazil where they resided. Several commented on geographic variation (‘Brazil is a big country with a huge disparity between the states’), and respondents highlighted a public/private health system divide (see quotes in ).

Countries without a pandemic plan that have experienced low death rates described early actions taken. For example, while Fijian respondents thought that initially no plan was executed, they had only two deaths (2.23/million) and were able to eliminate community spread of COVID-19. This was a result of the outer islands closing their borders early and the mobilisation of the military to enforce a strict self-isolation regime and curfew ().

Respondents from countries with low death rates often described the early implementation of a pandemic plan appropriate to that country. Respondents from the Republic of Korea indicated that their country had appropriately executed their plan, and their death rate has been low (6.83/million). New Zealand (NZ) was also able to initially eliminate COVID-19 (death-rate 4.98/million), and still has very limited community spread. Because NZ was not one of the first countries that COVID-19 reached, it was able to learn from the experience of other countries.

Decision-making priority in COVID response

Respondents from most countries thought that their nation’s pandemic responses were principally based on medical grounds (). The exceptions were respondents from Kazakhstan (death-rate 87.02/million) and the United States (US) (582.05/million), who considered pandemic decision-making to be based on primarily political grounds, and Fiji (2.23/million), who deemed them principally economically based. None of these three countries executed a plan although they had varying death-rates. Overall, there was no correlation between whether the decision was primarily based on medical facts and death-rate (rs = −0.12), or on economic factors (rs = −0.1) or for political reasons (rs = −0.024).

Table 2. Priority and level of authority guiding COVID decision-making.

In Kazakhstan, respondents were particularly critical about the lack of support for PHC in the pandemic response:

Unfortunately, primary health care has been ignored in the entire process of covid-19 response until now. Primary care providers were not equipped with proper PPE at all, apart from surgical masks … they continue to see patients in the same way, no distant evaluation (by phone/video calls/e-mails, etc) has been introduced on the national level;

After COVID-19 contacts were locked at homes, family doctors and their nurses had to visit all contacts at home without whole PPE. … Some non-COVID hospitals because of confirmed cases within were locked with health workers and patients. Doctors and nurses have to sleep on the corridors on the floor. Food is provided by charity … as a result Kazakhstan has highest proportion of SARS-C0V-2 infected health workers – more than 20% of all infected people.

Action based on medical grounds did not necessarily lead to lower death-rates. Respondents indicated that their country’s response was medically driven from nations both with high death-rates e.g. Belgium (‘health of the public/population came clearly in the first place’) and Spain (‘the medical issue and the health of citizens was the most important aspect’), and those with low death-rates e.g. Republic of Korea (‘medical considerations were the most important’) and Singapore (‘[introduced] medical impact-based measures’).

Level of ultimate authority guiding COVID decision-making

There was a moderately strong correlation between death-rate and decision-making being at local level (rs = 0.53); a weak correlation at national level (rs = 0.26), and no correlation at state or regional level (rs = 0.03) (). Correlations between pandemic strategy and level of decision-making were weak: national-level government rs = 0.2, state-level rs = 0.017, and local-level rs = 0.14.

Canada (death-rate 243.37/million) and the US (582.05/million) were the two countries where respondents were more likely to indicate decision-making occurring at state rather than national or federal level. One Canadian respondent comments:

Canada was a little slow to present a national strategy. In the early phase provincial health officers determined provincial responses,

US federal response to this crisis is an embarrassment and will go down in history as a textbook example of how NOT to respond to a pandemic. Individual state governors have had variable responses and time will tell who among them made good decisions,

I don’t have the energy to properly disparage the failure of leadership at the federal level in the US. I live in the state of xx and I think our governor and in particular my university (my employer) has done a great job locally.

Responsibility for health advice falls to Chief Medical Officer and State Chief Health Officers leading to different approaches on either side of arbitrary state border,

Federal Government in Australia has done the best job possible of following expert medical advice and were well ahead of most of the world in terms of response that achieved favorable outcomes.

Herd immunity or flatten the curve

The majority of respondents from all countries agreed that the initial intent for their country was to flatten the curve through physical distancing and restricted movement to increase the ability of the health system to respond, with the exception of the UK (death-rate 614.22/million) and Turkey (81.75/million) where only 40% of respondents agreed. Note that Sweden, where the strategy to develop herd immunity was most strongly expressed, is not one of the 37 countries included in the presented results, as it had fewer than five respondents.

UK respondents commented:

The rhetoric from politicians and the media was around ‘herd immunity’, although it may be unfair to say this was government policy. The government did not look at and learn from what was happening in other countries and delayed the decision to implement mass social distancing or ‘lockdown’ much too late.

The barmy ‘herd immunity’, it’s a mild disease for most, for about 5–7 days was confusing and undoubtedly increased cases.

Leadership and communication

Although the survey did not ask specifically about leadership or about communication, these two themes strongly emerged during analyses of the free text qualitative data. Many respondents from various countries identified that the strength and quality of leadership, effectiveness of communication strategies, and degree of population support to comply with directions, affected outcomes.

Many countries with high death-rates indicated poor leadership, while more countries with low mortality rates described effective leadership (). There were a few exceptions. For example, in Mexico (545.02/million), strong scientifically based leadership was reported, yet outcomes have been poor:

The leader of the response is an academic and very high technical level physician. This has helped a lot in order to have medical priorities and a national response.

Table 3. Leadership and communication associated with COVID-19-related mortality.

There is good collaboration between the task force and government.

Communication strategy with citizens also play an important role for avoiding transmitting the disease.

Population education on Covid-19 is essential via media, Facebook, Twitter … a lot of different opinions … caused a lot of confusion among the population.

Discussion

We hypothesised that if a country had a pre-existing pandemic plan, made decisions and pandemic responses based on public health principles and population data, and held the decision-making authority at the national level, it would have greater success combatting COVID-19, specifically lower death rates. From the perspective of our respondents, this does not appear to be the case. Having and executing a pandemic plan did not always correlate with better outcomes. In Iceland, the Netherlands and Switzerland, respondents indicated that a strategic national pandemic plan existed and was executed, yet they experienced high mortality, whereas Kazakhstan, Nigeria and Fiji experienced low mortality despite lacking a national plan. The importance of preparedness is illustrated by Korea and NZ – both implemented strong national pandemic plans early, which may have been the key to the low death-rates they experienced.

Belgium, where the response was reported as being based on the health of the people, has fared relatively badly. However, Belgian respondents thought that a pandemic plan was not initially executed. Furthermore, Belgium has a high-density population, and COVID-19 spread there rapidly from people returning from skiing trips in Italy, plus thousands of Belgians congregating for carnival (Vervoort, Citation2020).

In Fiji, however, respondents indicated the primary driver was the economy, and that the pandemic plan was not rapidly implemented, yet COVID-19 was eliminated. After its initial inaction, the island state had only air and sea borders to close, and it mobilised its military forces to enforce lockdown, and screen for cases.

Most respondents noted that authority for pandemic response was held at the national level, with the exception of the US and Canada, where it was seen to be regional. Having a democratic or dictatorial government also does not appear to be correlated to outcomes (). While some full democracies (Hale et al., Citation2020), such as NZ and Australia, have done well, others such, as the UK, have not. Conversely, more authoritarian states, such as China and Fiji, have experienced low death-rates (). Some full democracies relied on tools such as states of emergency to effectively manage the pandemic in an authoritarian fashion, which also blurs the line. Management professor Mauro Guillen writes ‘in democracies, greater transparency, accountability, and public trust reduce the frequency and lethality of epidemics, shorten response time, and enhance people’s compliance with public health measures’, it, however, has little impact on epidemic spread and fatalities (Guillen, Citation2020). Regardless of regime type, countries with resources, capacity and state structures to respond to a national emergency have fewer cases and deaths. While Spain and Italy are democracies, their governmental response to the pandemic was ‘completely disorganised’, they did not have the resources other European countries mobilised, and Southern Europe has greater economic inequality compared with Northern and Central Europe (Guillen, Citation2020).

Table 4. Geopolitical characteristics of the 37 study countries.

Income inequality exacerbates a poor epidemic outcome. People at the lower end of the socio-economic scale have poorer nutrition, less access to health care, cannot self-isolate as they need to get food, work and use public transport, often live in cramped accommodation, and may have limited access to basic hygiene measures such as hand washing, hence are more at risk from COVID-19 (Guillen, Citation2020).

Fukuyama extends this argument, saying that as well as state capacity, social trust and good leadership are necessary for a successful pandemic response (Fukuyama, Citation2020). Countries with a competent state apparatus, a government that the people respond to, and strong leadership, such as NZ, have performed well. On the other hand, countries with dysfunctional organisation and lack of coherent leadership, such as identified in the US, have done poorly.

A pandemic response demands collective action. Clear unambiguous messaging, a defined purpose (in NZ, this was ‘to minimise harm to lives and livelihoods’ (Wilson, Citation2020)), led by trusted experts who listen and respond to public concerns, will engender trust in the strategy, mobilise the collective effort (Wilson, Citation2020). Another route to collective action is that taken by Mainland China, which successfully introduced extreme stringent measures, including enforced lockdown and mandatory quarantine for 50 million people in Wuhan and nearby cities, and mobile app contact tracing. In this case, the collective response was produced through rigid social control and intrusive surveillance that would not be accepted in a democratic country (He et al., Citation2020).

PHC becomes more critical as detection, contact tracing, patient triage and avoidance of ‘COVID collateral’ (morbidity and mortality from non-pandemic sources) becomes possible. Primary care, the smaller, clinical portion of PHC, is important in the beginning stages for triage functions, and later for immunisations and managing related health care including comorbidities that might exacerbate disease. Differences in how primary care and PHC are configured, and their roles in national epidemic response plans, contribute to inconsistencies of our findings. For example, in the US, public health was a featured element of epidemic response plans, but primary care had no explicit role, so even if a plan had been effectively executed, the largest platform for healthcare was on its own. Variations at all levels – from federal planning, to execution of plans, to governmental structure and authority, to robustness and involvement of PHC – make learning from the pandemic experience about what to do next time difficult.

Strengths and limitations

This original and innovative study used a mixed methods approach with a rich qualitative dataset and robust analyses. The global reach was broad, with good geographical and economic spread of countries.

The study focused on the perspectives of primary care experts, not more objective measures of pandemic decision-making by countries. We used cumulative death-rates as our response variable, but acknowledge potential limitations from both under- and over-reporting, and the pandemic trajectories of different countries.

Multivariate regression modelling was performed, but the nature of the data did not support this approach, given the wide variation in the number of responses per country. Since the dependent variable was at country level, survey responses were also aggregated at country level. To estimate country-level responses with any degree of reliability, responses per country were required. However, only 38 countries had five or more responses. Given reasons explained earlier, China was excluded from the 38 countries, leaving only 37 presented in the analyses. High variance in the dependent variable and within-country in the predictors were compounded, given the small sample size which resulted in unreliable results. Further challenges were high levels of collinearity between the primary care strength and other control variables, such as income, population age and country income.

Implications/Conclusion

While Gates hypothesised that a pandemic could be controlled through global alert surveillance, a well-trained workforce, strong PHC especially in LMIC, and research and development technology for rapid development of diagnostics and vaccines (Gates, Citation2015), clearly there are other important considerations, including effective leadership to implement a plan, robust scientific advice, clear communication, and appropriate plans for specific geopolitical contexts.

Our findings about the COVID-19 pandemic remind us how difficult it is to find consistent and uniform predictors of early success in responding to an unpredictable, once per generation event. While some countries noted having pandemic response plans, most fell short on public capacity to rapidly and efficiently detect disease and execute a co-ordinated response. The study also highlights the capricious nature of spread, even in the face of planning coordination and the importance of favourable geography (such as island nations) when transit and border management are essential.

However, some policy-relevant and actionable patterns did emerge. Acting collectively, whether in a democracy or not, with rapid mobilisation of resources was associated with a reduced mortality rate. Similarly, countries with an absence of coherent leadership and social trust tended to have worse outcomes. Travel restrictions, while difficult in some geographies, were associated with early success, as well as clear and coherent communication with the public, and adequate resource mobilisation.

The lack of correlation between greater primary care capacity and integration with public health with strong relationships with early mortality is not surprising, when one considers how little was known about this novel coronavirus, its degree of contagion, much less its containment, in the early phase of the pandemic. The 2018 Astana Declaration for Primary Health Care (World Health Organization, Citation2018) may be worth revisiting to consider shared policies about preparedness of PHC to be part of a global response. What the pandemic has exposed about the Astana Declaration is that implementation of PHC around the globe is polar, meaning that less-developed countries tend to focus on public health and have weak primary care, and developed countries lean towards primary care with weaker public health. Few countries have well integrated public health and primary care capable of leading an epidemic response.

Ultimately, it is striking how the temporal distance between deadly pandemics leads to a lack of appreciation for the need for preparedness plans and infrastructure. While we hope that it is another century before the next one, it is difficult to stomach that the lessons are painfully relearned each time.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (907.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Altmann, D. M., Douek, D. C., & Boyton, R. J. (2020). What policy makers need to know about COVID-19 protective immunity. The Lancet, 395(10236), 1527–1529. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30985-5.

- Anderson, J. (2020, April 28). Sweden’s very different approach to Covid-19. Quartz. https://qz.com/1842183/sweden-is-taking-a-very-different-approach-to-covid-19/.

- Fine, P., Eames, K., & Heymann, D. L. (2011). ‘Herd immunity’: A rough guide. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 52(7), 911–916. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cir007.

- Fukuyama, F. (2020, July/August). The pandemic and political order: It takes a state. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2020-06-09/pandemic-and-political-order.

- Gates, B. (2015, March). TED2015. In The next outbreak? We’re not ready.

- Goodyear-Smith, F., Kinder, K., Mannie, C., Strydom, S., Bazemore, A., & Phillips, R. (2020). Relationship between perceived strength of countries’ primary care system and COVID-19 mortality. British Journal of General Practice Open. Published online 9 September. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgpopen20X101129.

- Greer, S. L., King, E. J., da Fonseca, E. M., & Peralta-Santos, A. (2020). The comparative politics of COVID-19: The need to understand government responses. Global Public Health, 15(9), 1413–1416. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1783340.

- Guillen, M. (2020). The politics of pandemics: Democracy, state capacity, and economic inequality. . Wharton Business School.

- Hale, T., Webster, S., Petherick, A., Phillips, T., & Kira, B. (2020). Oxford COVID-19 government response tracker. Blavatnik School of Government. Retrieved May 29, 2020, from https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/coronavirus-government-response-tracker.

- He, A. J., Shi, Y., & Liu, H. (2020). Crisis governance, Chinese style: Distinctive features of China’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Policy Design and Practice, 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2020.1799911.

- Johns Hopkins University of Medicine. (2020). COVID-19 Data repository by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved May 29, 2020, from https://github.com/CSSEGISandData/COVID-19.

- Klain, R. (2018). Politics and pandemics. New England Journal of Medicine, 379(23), 2191–2193. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1813905.

- Lenzen, M., Li, M., Malik, A., Pomponi, F., Sun, Y. Y., Wiedmann, T., Faturay, F., Fry, J., Gallego, B., Geschke, A., Gomez-Paredes, J., Kanemoto, K., Kenway, S., Nansai, K., Prokopenko, M., Wakiyama, T., Wang, Y., Yousefzadeh, M., & Xue, B. (2020). Global socio-economic losses and environmental gains from the Coronavirus pandemic. PLoS ONE, 15(7), e0235654. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235654.

- Molenberghs, G., Faes, C., Aerts, J., Theeten, H., Devleesschauwer, B., Bustos Sierra, N., Braeye, T., Renard, F., Herzog, S., Lusyne, P., Van der Heyden, J., Van Oyen, H., Van Damme, P., & Hens, N. (2020). Belgian Covid-19 mortality, excess deaths, number of deaths per million, and infection fatality rates (8 March–9 May 2020). medRxiv. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.20.20136234.

- Randolph, H. E., & Barreiro, L. B. (2020). Herd immunity: Understanding COVID-19. Immunity, 52(5), 737–741. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.012.

- Stewart, H., & Busby, M. (2020, March 13). Coronavirus: science chief defends UK plan from criticism. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/13/coronavirus-science-chief-defends-uk-measures-criticism-herd-immunity.

- Veiga e Silva, L., de Andrade Abi Harb, M. D. P., Teixeira Barbosa dos Santos, A. M., de Mattos Teixeira, C. A., Macedo Gomes, V. H., Silva Cardoso, E. H., S da Silva, M., Vijaykumar, N. L., Venâncio Carvalho, S., Ponce de Leon Ferreira de Carvalho, A., & Lisboa Frances, C. R. (2020). COVID-19 mortality underreporting in Brazil: Analysis of data from government internet portals. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(8), e21413. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2196/21413.

- Vervoort, D. (2020, July 24). Make all COVID-19 deaths count. Global Health Now. https://www.globalhealthnow.org/2020-07/make-all-covid-19-deaths-count.

- Wilson, S. (2020). Pandemic leadership: Lessons from New Zealand’s approach to COVID-19. Leadership, 16(3), 279–293. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715020929151.

- World Health Organization. (2018). Astana declaration on primary health care.

- Yuan, Z., Xiao, Y., Dai, Z., Huang, J., Zhang, Z., & Chen, Y. (2020). Modelling the effects of Wuhan’s lockdown during COVID-19, China. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 98(7), 484–494. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.20.254045.