ABSTRACT

The East Asian experience in tackling COVID-19 has been highly praised, but this high-level generalisation neglects variation in pandemic response measures adopted across countries as well as the socio-political factors that shaped them. This paper compares the early pandemic response in Singapore and Hong Kong, two Asian city-states of similar sizes, a shared history of SARS, and advanced medical systems. Although both were able to contain the virus, they did so using two very different approaches. Drawing upon data from a cross-national, probability sample Internet survey conducted in May 2020 as well as media and mobility data, we argue that the different approaches were the result of the relative strength of civil society vs. the state at the outset of the outbreak. In protest-ridden Hong Kong, low governmental trust bolstered civil society, which focused on self-mobilisation and community mutual-help. In Singapore, a state-led response model that marginalised civil society brought early success but failed to stem an outbreak among its segregated migrant population. Our findings show that an active civil society is pivotal to effective outbreak response and that trust in government may not have been as important as a factor in these contexts.

1. Introduction

East Asia has arguably been the most successful region in the world in terms of tackling COVID-19. Despite its geographic proximity to the epicentre of the pandemic, most states in the region managed to initially keep both the number of cases and deaths relatively under control. Many factors, including a shared common history with SARS and other infectious disease outbreaks, the speed at which countries implemented public health response measures (Han et al., Citation2020), and the strength and capacities of the health systems (Legido-Quigley et al., Citation2020), are all believed to have contributed to the region’s relatively effective response. However, this high-level aggregated view and public health focus overlook the fact that countries within the region did not all respond in the same way and that there were likely important differences in the socio-political factors that shaped their outbreak response.

In January, Hong Kong and Singapore were both at extremely high risk of importing COVID-19 cases from China. While both were able to contain the virus during the early phases of the pandemic, both eventually went on to experience localised outbreaks: Hong Kong experienced significant community transmission starting in mid-March, mainly due to an influx of imported cases, while Singapore did not experience a sharp spike of infections until mid-April, most of which were concentrated in migrant workers’ dormitories. Hong Kong went on to quickly control this wave as well as another wave which began in late June, whereas it took Singapore until August to get its outbreak under control. As of 31 August 2020, there had been 4,810 confirmed cases and 89 deaths in Hong Kong, and 56,812 confirmed cases and 27 deaths in Singapore.

These two highly-developed, East Asian city-states share many common features. Although one is an independent sovereign state and another a semi-autonomous city in China, both were former British colonies operating on semi-authoritarian political systems. Both have similar geographic areas, population sizes, and income levels; and both have strong health systems that have heavily invested in preparing for outbreaks like COVID-19 since the 2003 SARS outbreak (An & Tang, Citation2020). Despite these similarities and their relative success in their containment efforts, the two city-states mounted very different responses to the pandemic. This raises the question of what factors led them to respond in the way they did. There has been great interest in using comparative political theories and methods to explain variation in policy responses to COVID-19 (Greer et al., Citation2020). Some of the early findings have already challenged commonly held beliefs. For example, although it is widely accepted that democratic countries produce better health outcomes, in the early phases of the pandemic many authoritarian states appear to have outperformed in their ability to tackle the virus (Kavanagh & Singh, Citation2020).

This study echoes the call to understand the adoption of COVID-19 responses by examining their underlying socio-political drivers. Comparing these similar city-states through process tracing and a rich set of data, we focus on the role of political trust and social mobilisation and argue that differences in these two underlying sociopolitical factors resulted in two different trajectories in their pandemic responses. Overall, we find that while both city-states had been relatively successful in containing the outbreak, the emergence of their different approaches resulted from the relative strength of civil society vis-à-vis the state at the outset of the outbreak. In protest-ridden Hong Kong, low trust in the government bolstered civil society-led responses that focused on self-mobilisation and community mutual-help to provide speedy intervention when the government was perceived to be incapable. In Singapore, a state-led response model, enabled by high trust in the government but with a marginalised civil society, brought early success to the containment effort. However, it failed to stem a sudden outbreak among its segregated migrant population, which highlighted government ineptitude and the underappreciated contribution of civil society actors. Our findings show that an active civil society can play a pivotal role in contributing to effective pandemic responses and that trust in government may not be as important.

2. The role of political trust and social mobilisation in public health responses

Political trust and social mobilisation are key socio-political factors that could shape public health responses to the pandemic (Abramowitz et al., Citation2015; Bavel et al., Citation2020; Blair et al., Citation2017; Parker, Citation2009; Terpstra, Citation2011). Previous studies, however, have not compared the relative importance of these factors alongside each other. We review these two concepts before providing empirical evidence of the distinct trajectories of responses in the two city-states. To begin, political trust – including trust in government or other public institutions – is widely measured in the study of public health responses. Trust is commonly defined as the belief in which one’s interest would be carefully taken care of (Easton, Citation1975). Trust is also relational, meaning that trust involves at least two different actors; and it is contextual, meaning that it has to be associated with a specific type of action (van der Meer, Citation2017). Therefore, when we talk about trust, it is usually expressed in the form of an object trusting a subject to perform an action.

In the context of pandemic containment efforts, political trust is about whether the public would believe the government or health department would take timely, appropriate, and effective measures to contain the spread of the disease. Trust is also associated with the government or public institutions’ competence and their predictability on issues (Green & Jennings, Citation2012). A higher level of trust means that citizens are more likely to endorse and comply with government actions in dealing with the pandemic. In the literature on public health responses, it was widely believed that high levels of trust in government are essential for states to mount effective responses due to the need to ensure compliance among the general public as well as to provide accurate information regarding the state of the outbreak (Bavel et al., Citation2020). In the West African Ebola outbreak, higher levels of trust were associated with higher compliance with public health measures, such as social distancing, mask-wearing, and quarantine (Blair et al., Citation2017). Indeed, in the current pandemic, higher levels of institutional trust have been associated with more effective responses in Europe (Oksanen et al., Citation2020) and in articulating greater perceptions of risk (Jang et al., Citation2020).

Social mobilisation refers to the collective effort initiated by civil society actors to serve the common good. Specifically, social mobilisation (1) offers a sense of group solidarity through community-based initiatives; (2) offers access to protective resources through mutual assistance; (3) increases public awareness of the severity of the crisis; and (4) pressures authorities to introduce more effective and attentive policies. In contrast to the top-down view of responses to the pandemic, social mobilisation can be either bottom-to-bottom or bottom-up. These two approaches are distinct and have been well documented in the literature on public health responses. The bottom-to-bottom approach is characterised by citizens’ self-reliance effort that seeks to tackle or alleviate problems of the pandemic on their own. In Liberia, for instance, local people use a community-based self-reliance approach to contain the outbreak of Ebola in the absence of quality health support and infrastructure from the government in the area (Abramowitz et al., Citation2015). The community may even at times discourage efforts from the top to manage the outbreak of the disease. On the other hand, the bottom-up approach generates needs and demands related to public health issues among societal actors and relays it to the government or other political institutions. For example, in Brazil, the pressure mounted by a broad-based civil society coalition on the government was instrumental to the later success of the country’s responses to HIV and AIDS (Parker, Citation2009).

Political trust and social mobilisation are thus expected to be important factors in the containment efforts during COVID-19 pandemic. Several scholars have already pointed out that social mobilisation, particularly at the community level, was able to compensate for the lack of formal state capacity and low political trust in responding to the pandemic (Hartley & Jarvis, Citation2020; Miao et al., Citation2020; Wan et al., Citation2020). Following a similar perspective, this article continues to examine how these two factors combine and interact in shaping country’s pandemic responses. To what extent is political trust a precondition to effective responses? What role does social mobilisation have to play under different levels of political trust? The nuanced processes and outcomes in our most-similar case design will contribute to these timely questions regarding the role of these factors in responding to public health challenges.

3. Materials and methods

We conducted a comparative case study to explore the underlying factors that may explain the different approaches pursued by Hong Kong and Singapore during the first eight months of the COVID-19 pandemic. As previously described, Hong Kong and Singapore are two East Asian city-states that share many common features, making them ideal for a paired comparison. To explore how responses varied with political trust and social mobilisation across the two cases, we relied on a variety of original and publicly available data sources. In the first part, we used process-tracing to trace the different trajectories of anti-pandemic responses in the two city-states. We focused on the period between January and August 2020, the first eight months of the pandemic when responses were most critical. The thick descriptions of both cases will provide the empirical foundation for more in-depth comparison.

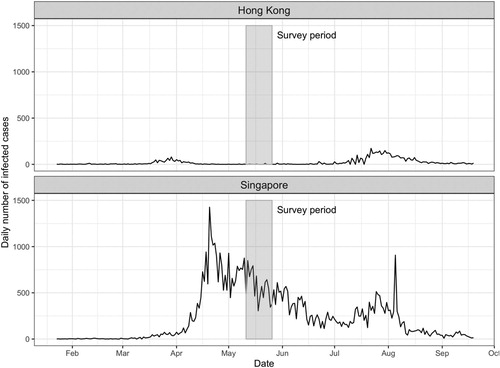

In the second part, we further analyze their differences in the pandemic responses on the individual level through the combination of survey, mobility, and newspaper data. First, we conducted cross-national surveys to gauge public attitudes in Hong Kong and Singapore between 11 May 2020 and 26 May 2020 concerning COVID-19. Ethical approval for conducting the survey was obtained by one of the authors from the City University of Hong Kong (H002400). shows that the survey was conducted when the outbreak had come under control after the ‘second wave’ in Hong Kong while Singapore was in an intense phase of their outbreak. The online surveys were conducted through Dynata, a global digital research agency, with representative samples of 2,034 and 2,027 respondents in Hong Kong and Singapore respectively.

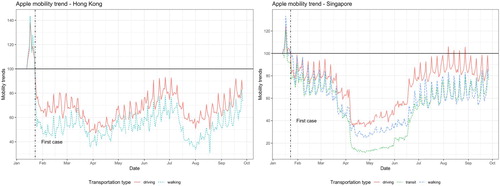

Second, we analyzed mobility data in Hong Kong and Singapore provided by Apple, a global technology company, to help policymakers and public health researchers to track people’s movements in different countries during the pandemic. The data (covid19.apple.com/mobility) shows the relative volume of direction requests enquired by their users in their Apple Map service in the two city-states with a baseline volume at 100 on 13 January 2020. The dataset distinguishes the direction requests by driving and walking (also by transit in Singapore). We downloaded the daily time-series data between 13 January and 26 September 2020. Data collected from Apple’s users may not reflect the movements of the population. Nonetheless, Apple is widely used by many in Hong Kong and Singapore and thus the data represents a good illustration of people’s movement.

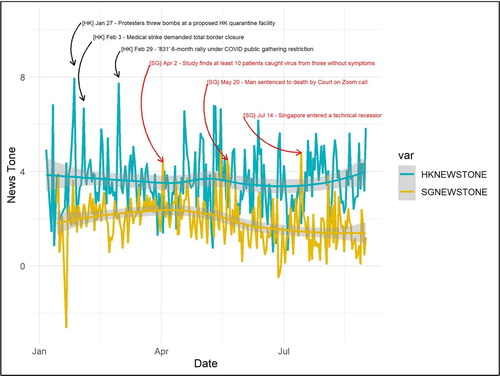

Finally, we analyzed a media dataset called the Global Database of Events, Language, and Tone (Leetaru & Schrodt, Citation2013), which records world events reported by all national and international news on Google News and provides the attributes of the event such as location, theme, and tone. We downloaded the GDELT data between 1 December 2019 and 18 September 2020, and filtered the data by locations (‘Hong Kong’ or ‘Singapore’) and theme (‘Coronavirus’ and {‘POLICY’ or ‘GOVERNMENT’ or ‘MINISTER’ or ‘NATIONAL_LEADER’ or ‘TAX_FNCACT_CHIEF_EXECUTIVE’ or ‘TAX_FNCACT_PRIME_MINISTER’}). In total, 43,207 documents were obtained. Among all the documents, 22,641 and 20,566 of them were records of Hong Kong and Singapore events respectively. The top three web domains of the news sources are: Hong Kong – reuters.com (5.8%), thestandard.com.hk (3.4%), and msn.com (2.5%); Singapore – straitstimes.com (10.4%), reuters.com (6.5%), and yahoo.com (4.5%). The average ‘tone’ of the document reporting the event is then extracted from the GDELT dataset.

4. Responses to COVID-19 in Hong Kong and Singapore

Hong Kong confirmed its first cases of COVID-19 on January 22, following speculation that the number of cases was growing rapidly in Mainland China. On January 25, the government activated the Emergency Response Level system and formed a Steering Committee that brought together government officials and public health experts. Control measures, including the suspension of flights and high-speed train services from Wuhan as well as the expansion of health declaration arrangements to all border checkpoints, were introduced. However, there were no restrictions for people travelling from other parts of Mainland China. Many citizens criticised the government for reacting too slowly to the spread of infection from the mainland, while others demanded a full border closure and stricter regulations. Several new cases from inbound mainland travellers arriving on high-speed rail further intensified these concerns. On February 4, three local cases were discovered, suggesting that community transmission had begun. It was only until then did the government shut down numerous border checkpoints with the Mainland and imposed more stringent measures.

The surge of coronavirus infections evoked painful memories of the SARS epidemic, which took 299 lives and devastated the city’s economy. But the memories also prompted preparedness and mobilised mask-wearing among Hongkongers early on. A study showed that 75% of adults wore surgical masks in public areas in late January, and this increased to 95% in February and March (Cowling et al., Citation2020). Because of this, the city soon faced a severe shortage of masks. Local supplies were sold out and new masks could not be imported because of the disruption of international shipments and closure of Chinese factories. Online rumours that other household essentials also could not be imported from the Mainland prompted widespread panic buying, prompting shoppers to snap up toilet paper and rice in supermarkets. The resulting shortages further weakened citizens’ confidence in the government. On February 8, Bloomberg published an article with a sensational headline (Marques, Citation2020) – ‘Hong Kong Is Showing Symptoms of a Failed State’ – which was generally reflective of the public sentiments at that time.

Amidst the widespread criticisms against the government, Hong Kong’s civil society mobilised quickly. But rather than being a collection of the individual actions of people sharing the SARS memory, the mobilisation efforts were collective and coordinated. This was largely a result of the Anti-Extradition Bill Protests of 2019, the largest anti-government protest in Hong Kong’s history, in which as much as 42% of the population had participated (Lee et al., Citation2019). On January 23, two District Councils run by pro-democracy activists announced the purchase of masks and disinfectants for mass distribution. Many other District Councils followed suit. Some councillors even flew to Taiwan and Japan to source surgical masks to ease local shortages. According to Wan et al. (Citation2020), 82% of District Councilors held at least one mask sharing activity by February. Similar efforts were made by other pro-democracy groups. For instance, Demosisto, a now-disbanded political party led by young activist Joshua Wong, ordered 1.2 million masks from Honduras in mid-February, emphasising that the country – an ally of Taiwan – was ‘chosen’ because it does not trade with China. Sensing that the containment efforts had become a new arena of political contestation, pro-government parties mobilised in tandem. They sourced masks from the mainland using their political connections and distributed them to grassroots citizens through mass organisations and native-place networks.

The mobilisation of the pro-democracy camp was, to some extent, the continuation of the 2019 protests. Although the extradition bill was no longer an imminent threat, the pandemic became an opportunity for the activists to discredit the government by highlighting its poor crisis management. This was illustrated by the irony that many of the masks distributed to citizens were in fact stocks left over from the protests, which had become a symbol of resistance when an anti-mask law had been introduced by the government to stem the protests. Telegram, an encrypted messaging app that had been used widely to coordinate the 2019 protests, swiftly became a platform for disseminating anti-pandemic information. A search in a protest archive (https://antielabdata.jmsc.hku.hk/) compiled by one of the authors identified close to 2,000 e-posters about the epidemic circulating on Telegram groups. A website that was designed by pro-democracy activists to provide fact-checked information about the District Council election was renamed into ‘COVID-19 in HK’ (https://wars.vote4.hk/en) to dispatch updates on the pandemic. Meanwhile, although protests had waned from 2019, numerous smaller protests sprang up across the city to demonstrate against government plans to set up designated coronavirus clinics and quarantine sites near residential areas. In one protest, protesters even threw petrol bombs at a newly constructed block after rumours emerged that it would be used as a government quarantine site. All of these reflected the deep distrust toward the government.

The biggest protest, however, was held by an unlikely group of protesters – medical workers – who became the most vocal in demanding the government to close all border checkpoints at a time when the city’s testing capacity was limited and hospitals were under immense pressure. Cross-border travel between Hong Kong and the Mainland has long been a contentious issue in the city but the pandemic galvanised it and turned border closure into a new demand among pro-democracy supporters. The demand also gained support from prominent public health experts, creating further pressure on the government. On January 31, the Hospital Authority Employee Alliance, a pro-democracy labour union established by medical professionals, announced plans to organise a hospital staff strike and 9,000 medical workers pledged to join the strike. The strike, which was held from February 3–7, demanded the immediate closure of the border and the stable supply of surgical masks and equipment for frontline medical staff. Despite creating disruptions in hospital services, the strike received strong public support: according to a late January poll, 61% of respondents supported the strike, while 75% were unsatisfied with how the government handled the pandemic, and 80% supported the complete closure of borders (Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute, Citation2020). The mounting pressure, coupled with the confirmation of the first locally-transmitted cases, eventually forced the government to close several checkpoints. A full border closure, however, was rejected by the Chief Executive Carrie Lam who argued that it would be ‘discriminatory’ to ban all Mainlanders.

A more stringent set of public health measures ensued. Civil servants were asked to work remotely from home; schools and universities were closed; and all recreational facilities were shut down. The government also learned from their mistakes in the SARS epidemic and concentrated their efforts on preventing intra-hospital transmissions, implementing quarantines, and initiating contact-tracing. These measures managed to curb the infections by late February; but as cases rebounded in mid-March during the ‘second wave’, additional measures were introduced, including a ban on group gatherings and restriction on the opening hours of restaurants. Nonresidents arriving from overseas were now banned from entering Hong Kong while returning residents were subject to a mandatory 14-day quarantine. The stringent measures again paid off in controlling the contagion by late April. However, their relaxation precipitated a third wave of infections that started in early July but eventually came under control in late August.

In contrast to the salient role of civil society in Hong Kong, Singapore adopted a much more state-led and top-down approach. Such kind of approach was expected in Singapore in light of the centralised nature of authority, coupled with the uninterrupted dominance of the People’s Action Party (PAP), the ruling party which has been in power for 61 years (Abdullah & Kim, Citation2020). The city–state discovered its first confirmed case on January 23. Learning from its SARS experiences, the Singaporean government also reacted rapidly by setting up a Multi-Ministry Taskforce, which brought together public officials, medical professionals, and scientists to facilitate inter-departmental coordination. The National Centre for Infectious Diseases, a purpose-built medical facility established in July 2019, also became a critical infrastructure in the anti-pandemic fight. Unlike in Hong Kong, control measures were quickly introduced to prevent virus-infected arrivals from abroad, especially from China. These policies include implementing temperature screening in all border checkpoints; issuing a travel advisory against nonessential trips to China; introducing a 14-day quarantine order for visitors arriving from Hubei Province; and imposing a ban on entry and transit for visitors who had been to China recently. Singapore’s preparedness and rapid state-led responses, which stalled the spread of infections, earned praise from the World Health Organization, which saw the city–state as the gold standard of crisis management (Cher, Citation2020). However, this early success proved short-lived as confirmed cases began to rise in late March. New non-traceable infections and secondary local transmission were also discovered. The surge of infections prompted Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong to introduce a series of ‘circuit breaker’ measures starting from April 3 to effectuate a partial lockdown, including the closure of workplaces and schools as well as the restriction of movement and gatherings. Also, in contrast to earlier advice that discouraged healthy individuals from wearing masks due to the concern of availability, mask-wearing was made compulsory in public spaces.

The tightening of measures failed to prevent the emergence of a key phase that started around mid-April, when foreign workers, who make up almost 10% of Singapore’s 5.6 million population (Ministry of Manpower, Citation2020a), accounted for most of the coronavirus clusters. Cases quadrupled from 1,000 on April 1 to 4,427 on April 16, 60% of which were foreign workers living in dormitories. By early June, infections in worker dormitories, which were often overcrowded and poorly ventilated, already accounted for more than 90% of Singapore’s total cases. In response to this major loophole, the government introduced a series of sweeping measures, such as isolating infected patients from the dormitories, conducting mass testing, and establishing on-site healthcare facilities in the dormitories (Koh, Citation2020). An inter-agency task force was also formed, bringing together health, workforce, military, police, and NGO personnel to coordinate containment efforts in the migrant workers’ community. These government-led efforts succeeded in flattening the curve of infections among migrant workers by mid-August, but the outbreak revealed Singapore’s poor treatment of its guest workers and showed that it was too early for the government to feel complacent about its responses.

To be sure, it was the dense living environment of the migrant workers, rather than the government’s top-down approach, that led to the surge of infections. But it is important to note that government oversight was also an important contributing factor. Woo (Citation2020) argues that while Singapore’s strong fiscal, operational and political capacities, accumulated after the SARS crisis, helped contribute to its low fatality rate and contact tracing capabilities, its lack of analytical capacities was a key reason why the government was not cognizant of the infection risks in the densely-populated dormitories. We add to this state-oriented perspective and argue that the long-term marginalisation of civil society groups also accounted for the failure to detect such risks. Compared with Hong Kong, civil society in Singapore played a more peripheral role when the pandemic started. While there were civil society groups and ground-up initiatives organised to distribute food and surgical masks to vulnerable citizens from early on, their scale remained small and their works were largely complementary with government initiatives rather than taking a critical approach. PAP’s dominance in the bureaucracy and local constituencies, coupled with the lack of press freedom, also meant that it was difficult for the opposition to organise its responses and for the media to hold the government to account. Besides, as the government continued to crack down on protests and online expressions with a new anti-fake news law, there was little room for criticisms against government responses (CIVICUS, Citation2020). Under this restrictive environment, the most critical voices were from civil society groups that work on migrant issues, such as Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2) and Humanitarian Organization for Migrant Economics (HOME), which had been advocating for migrants’ rights for years and made early warnings that workers’ dormitories could become infection hotspots (Kathleen, Citation2020). Their advice, however, was largely ignored by an overconfident government. Neither did the migrant workers themselves have a political voice. As a transient and disenfranchised minority, these workers had been discouraged from participating in collective actions to protect their rights. Those who attempted to do so would face the risk of deportation or not having their contracts extended.

The large-scale outbreak in the migrant workers’ community provided a rare political opportunity for civil society groups to play a more proactive and high-profile role in the containment efforts that is rarely seen in the semi-authoritarian city–state. In response to the lockdown of the dormitories, a spreadsheet that aimed to compile resources and coordinate societal volunteering efforts quickly spread online. Websites that offered Bengali, Tamil, Thai, and Hindi translations (https://translatefor.sg/) from English were soon developed for overcoming the language barrier between health professionals and migrant workers (Koh, Citation2020). Several grassroots NGOs and social enterprises also formed an informal alliance known as COVID Migrant Support Coalition to distribute free meals to quarantined workers. Meanwhile, staunch migrant advocates such as TWC2 and HOME continued to put pressure on the government, lobbying officials to reduce dormitory density and to improve the welfare of foreign workers (TWC2, Citation2020). This quick mobilisation of civil society was arguably quite effective in checking the government and keeping officials vigilant about the developing situation. For instance, when a photo that showed the poor quality of food delivered to the workers went viral online, the government quickly apologized and promised to improve food quality (Chia, Citation2020). Meanwhile, advocacy pressure also forced the government to build new dormitories to reduce crowdedness (Asokan, Citation2020).

Nevertheless, despite their increased role, these civil society actors remained subsumed under the government’s top-down efforts directed by the newly established inter-agency taskforce. The taskforce brought in Migrant Workers’ Centre, a state-affiliated NGO, to coordinate other grassroots NGOs and ground-up initiatives, which became the conduits for the government to reach out to more foreign workers and address their basic needs. The top-down mentality remained prominent, however. For instance, public donations had to be centralised by the task force before distributing it to the dormitories. As the Ministry of Manpower, which headed the task force, stated on their website (Ministry of Manpower, Citation2020b), ‘[h]aving dedicated vast amounts of public resources across the whole of government, we must not risk uncoordinated actions compromising the integrity of ground operations and weakening their effectiveness.’ Still, the mere recognition of civil society actors was an important shift. And without their deeper involvement, state-led responses in this key phase might not have been so successful.

In sum, despite their relative successes in curbing the spread of infections, the two city-states experienced different trajectories. In Hong Kong, given the immense distrust toward the government, civil society played a crucial role in mobilising self-help containment efforts early on in the outbreak. Although the government learned from its mistakes in SARS, its initial responses were widely perceived to be inadequate and tougher measures were only introduced because of pressure mounted by civil society actors. In Singapore, the government adopted a top-down approach from the beginning, which left little space for civil society. The marginal role of civil society partly accounted for the government’s overconfidence and its neglect of its weak spot – the migrant workers’ community. The loophole pushed civil society actors to a more prominent position; and even though they remained confined by a top-down governmental structure, their contributions were instrumental to overcoming the crisis.

5. Data analysis

The differences in the pandemic responses between Hong Kong and Singapore can be further analyzed on the individual level through the combination of survey, mobility, and newspaper data. To what extent and when did citizens in the two city-states comply with public health measures? How much did people trust the authorities, and to what extent do they appreciate the contribution of the government to the disease containment efforts? To what extent did social mobilisation and political trust play a crucial role in motivating self-protective behaviour in the two city-states?

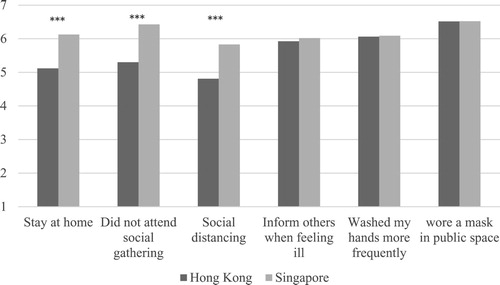

A cursory glance into our survey data indicates that Hong Kong and Singapore both have high levels of compliance with public health measures. When respondents were asked whether they complied with a particular measure on a 7-point Likert scale, both Hongkongers and Singaporeans indicated an average score of above 6 for wearing a mask in public space and washing hands frequently and around 6 for informing others when exhibiting symptoms of sickness. However, compared with Hongkongers, Singaporeans are more compliant in terms of staying at home, not attending social gatherings, and practicing social distancing (), with t-tests indicating that the differences are statistically significant (p < 0.001). The discrepancy may be because the survey was conducted from mid to late May when Singapore was implementing circuit breaker measures while the outbreak in Hong Kong came temporarily under control. This point can be further illustrated by the mobility data trends. As the trend in Singapore shows ( right), the period between January and April only saw a slight overall decline of travelling from the pre-pandemic baseline; but the trend dropped dramatically from early April onwards when the circuit breaker measures were introduced. When the survey was conducted in Singapore, public transit was only 20% of the baseline and it was not until July that it climbed back to the level before April. In Hong Kong ( left), mobility plummeted immediately after the first two confirmed cases were announced on January 22, and remained at only around half of the baseline until reaching the bottom in early April. The survey was implemented at a time after mobility had begun to rebound.

Figure 2. Compliance with self-protective behaviour (1 = very inaccurate, 7 = very accurate). Note: t-test is statistically significant when *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

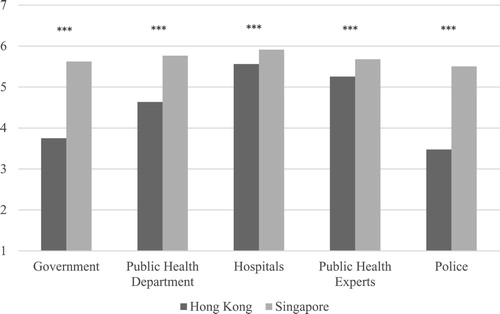

The mobility trend in Hong Kong highlighted another important point – that citizens reacted swiftly to reduce social activities even before the government introduced stringent measures. This is in sharp contrast with Singapore, where travelling only declined dramatically after the circuit breakers were imposed. One likely explanation may have to do with citizens’ trust in the government. As our survey shows, Singaporeans trusted their government much more than Hongkongers (). In Hong Kong, trust in government is significantly lower than trust in all other public institutions, except the police, which is a result of the 2019 protests (Cheng, Citation2020). This low level of trust in the government may explain the early mobilisation of citizens and civil society as they perceived the government to be acting slowly and insufficiently. In Singapore, however, trust in the government is only slightly lower than, if not on par with, trust in hospitals and public health experts. This may account for why Singaporeans’ mobility remains rather high even after the first coronavirus case was confirmed, as citizens saw government responses as effective and adequate.

Figure 4. Trust level in public institutions, Hong Kong vs. Singapore. Note: t-test is statistically significant when *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

The GDELT news tone data further illustrates the difference of trust in the government between the two city-states.Footnote1 As indicates, Hong Kong generally has a more negative tone in its news about the government policy and the leaders compared with Singapore, which makes sense because the former territory, despite its authoritarian regression in recent years, has stronger press freedoms, according to the ranking released by the Reporters Without Borders (Reporters Without Borders, Citation2020). However, setting the overall trend aside, it is important to point out that the period between January and April in Hong Kong saw a number of negative spikes that likely reflected the immense distrust toward the government during the early stage of the pandemic, i.e. the medical strike in early February and the protest against the location of quarantine facility in late January. In contrast, Singapore did not experience such spikes in negative news tone in the same period; and there was even one day (the day before the first confirmed case was announced) in which the news tone became unusually positive. The negative spikes did not appear until between April and May, when the outbreak in migrant workers’ dormitories sparked growing criticisms against the government.

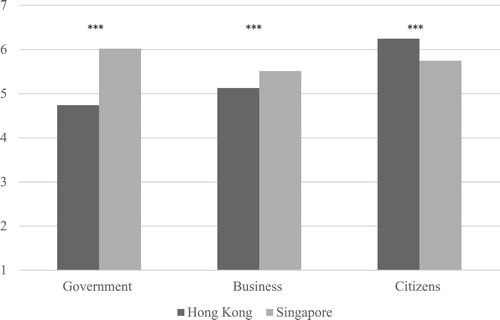

The differing level of trust in government between Hongkongers and Singaporeans is perhaps most reflected in their different opinions over who contributed the most to the disease containment effort. When asked how significantly certain actors contributed on a 7-point Likert scale (), respondents from Hong Kong, on average, considered citizens as the most important contributor (6.24), followed by businesses (5.13). The government came last (4.74). Respondents from Singapore, meanwhile, saw the government as the most significant contributor (6.02), followed by citizens (5.74) and businesses (5.51). T-tests show that the differences between Hong Kong and Singapore are statistically significant in all three items (p < 0.001).

Figure 6. Contribution to disease containment effort (1=very insignificant, 7=very significant). Note: t-test is statistically significant when *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Given the respective importance of citizens and the government in the containment efforts across the two city-states, one would expect to find correlations between these factors and various self-protective behaviours. In Hong Kong, if civil society mobilisation is indeed crucial in curbing infections, then people who engaged more in such social mobilisation efforts were likely to be more self-protective and careful themselves. Likewise, in Singapore, given the prominent role of the government in leading disease containment efforts, then people who had higher trust in the government were likely to be more committed to self-protective behaviours.

To test these relationships, we estimated a series of OLS regression models on the Hong Kong and Singapore survey data respectively. We specify the six self-protective behaviours asked in the survey as dependent variables and also aggregate them into a composite index to create an extra dependent variable, known hereafter as ‘aggregate self-protection’. We focus on three sets of independent variables that are of particular analytical interest. The first looks at political trust and includes two variables: (1) trust in government; (2) trust in public health experts. The second set focuses on social behaviour and also includes two variables: (3) social mobilisation, which is a sum of two survey items – how frequent the respondent donated money, masks or other supplies and how frequency he/she participate in volunteering activities to help those who are vulnerable to the pandemic; (4) the belief that neighbours have made an effort in containing the outbreak, which can be a proxy for social capital. The final set are two key personal attributes, including (5) worriedness about being infected with coronavirus, which measures risk perception; and (6) memory of SARS, which measures the effect of the personal experience in dealing with past epidemics. We finally control for age group, gender, socioeconomic status, education and housing. and shows the descriptive statistics of the key variables and the control variables respectively.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of key variables of interest.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of control variables.

and presents the results of the regression models.Footnote2 Our first observation is that social capital – the belief that neighbours had made an effort – positively predicts all kinds of self-protective behaviour in both Hong Kong and Singapore. This shows that a greater mutual expectation that others would do their part is conducive to a higher awareness of self-protection; and there was no difference between the two city-states. We also found that people in Hong Kong who were more active in social mobilisation are indeed more likely to have engaged in aggregate self-protection (β = 0.038, p = 0.0034), which aligns with our expectation. This was, however, the opposite in Singapore: people who were more active in social mobilisation are less likely to engage in aggregate self-protection. The finding in Singapore, in fact, makes more intuitive sense. People who donated and volunteered more probably should have stayed at home less and should have participated in more social gatherings. This was indicated by the regression models on the two constituent dependent variables – stay at home and no social gatherings – in which the coefficients for social mobilisation is negative and statistically significant (β = −0.068, p = 0.0005; β = −0.110, p = 0.0000). Hong Kong, in contrast, shows a rather counterintuitive result because those who mobilised more tended to stay at home more frequently (β = 0.146, p = 0.0000). Although such respondents did not tend to attend fewer social gatherings, they were likely to have practiced social distancing more faithfully (β = 0.207, p = 0.0000). This implies that social mobilisation in Hong Kong amounts to some form of self-help mobilisation, in which people mobilised on their own and likely within their community to help with the containment efforts. Interestingly, in both Hong Kong and Singapore, social mobilisation has a negative and statistically significant relationship with mask wearing. This result is against our expectation. One possible reason may have to do with the low variance of mask wearing, since most people in both city-states reported to be wearing masks frequently. Indeed, the mask wearing variable has the lowest standard deviation among the variables of all six self-protective behaviours.

Table 3. OLS regression models for Hong Kong.

Table 4. OLS regression models for Singapore.

On the other hand, contrary to expectations, trust in the government does not predict engagement in all kinds of self-protective behaviour in Singapore. Neither does trust in public health experts. One explanation is that the survey was conducted more than one month after the implementation of circuit breaker measures in Singapore, and their mandatory nature meant that people would have followed them regardless of their trust in government or experts. In Hong Kong, trust in the government similarly does not predict engagement in aggregate self-protection. Nevertheless, trust in public health experts do have a positive and statistically significant relationship with it (β = 0.09, p = 0.0000), as well as all kinds of self-protective behaviour. This shows that political trust is specific to the institution in question, and is reflective of the fact that Hongkongers have much higher trust towards public health experts than the government. Interestingly, trust in the government even predicted lower engagement in some self-protective behaviour, namely informing others when feeling ill, washing hands frequently and wearing masks in public spaces.

On the personal level, worriedness about being infected by coronavirus is a strong and statistically significant predictor of all types of self-protective behaviour, lending support to similar scholarly findings that risk perception enhances the willingness to follow public health advice (Bish & Michie, Citation2010). Meanwhile, memory of SARS strongly predicts all except one kind of self-protective behaviour in Hong Kong, but only two out of the six in Singapore. This finding can be anticipated because the SARS epidemic was a more traumatic experience for citizens in Hong Kong than citizens in Singapore.

6. Discussion and conclusion

This paper analyses the responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong and Singapore: two East Asian city-states with many common features at the onset of the pandemic. And while the two city-states performed relatively well in terms of containing their outbreaks at a global-level through early 2020, the factors that explain their performance differ between the two settings. In Hong Kong, the 2019 pro-democracy protest movement contributed to low governmental trust but also bolstered civil society’s network and experience in collective mobilisation. Instead of relying on government directives, its civil society-led model mobilised resources to overcome barriers, increase compliance, and pressure the authorities to tighten measures. In contrast, in Singapore, a state-led response model brought early success but failed to stem a sudden outbreak among its segregated migrant population and provided necessary care to the under-privileged, partly because civil society actors were marginalised in the country’s initial responses.

Our more detailed comparison of the two cities also demonstrated some more nuanced differences between the two responses. First, while compliance with public health measures in May was high in both settings, the timing of the adoption of these measures by citizens differed. In Hong Kong, mask wearing and the curbing of mobility occurred even before government issued directives whereas in Singapore, citizens only made major changes to their behaviour after the government mandated such changes. There is strong evidence that the strong social mobilisation efforts launched by civil society in Hong Kong was one factor that explained this difference but it may also be the case that high-levels of trust in government in Singapore may have prevented such reactions from citizens as their belief that government was doing the right thing and that the response to that point had been effective.

Second, our study found evidence that also challenges the conventional view that trust in government is a precondition to mounting an effective response to an infectious disease outbreak. Trust in government was very low by relative and historical standards in early 2020 in Hong Kong; yet despite this, a highly effective response was still achieved. If anything, low levels of trust in government may have been a factor that directly led to high levels of social mobilisation, which was likely a key success factor in Hong Kong. In Singapore, while trust in government was high and remained so through May, the outbreak became more serious due to government oversight of the foreign worker community. On the other hand, while citizens in both city-states appeared to have high levels of compliance with public health measures, we find that this had little to do with trust in government. Instead, we find evidence that other forms of trust, for example trust in public health experts may play some role in shaping outcomes. We also find that social capital, which is likely associated with measures of generalised or community trust, was an important predictor of compliance with measures in both settings.

In terms of lessons learned for future pandemics, we believe that the case of Hong Kong and Singapore provide some important lessons for pandemic planning both in these settings and in other countries. There is no one right way to mount an effective response to infectious disease threats. Countries that have high levels of trust should leverage this resource in ways that can benefit response measures, but where such resources are lacking, supporting civil society can also be effective. Also, where trust exists, as it did in the case of Singapore, it cannot be a substitute for more community driven engagement activities. The lack of engagement with the community may have led to them not seeing the important blindspots that were the dormitories that were housing the migrant communities. Engagement with these civil societies was helpful in helping to bring the outbreak under control in those communities.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The positive tone and negative tone scores are the percentages of all words in the article that were found to have a positive and negative emotional connotation respectively. The average tone is calculated by differing the positive tone score and negative score. Since most average scores are less than zero, the visualisation shows the negated average tone score, i.e. the higher value, the more negative emotional connotation in the document on average. Daily average scores for Hong Kong and Singapore are displayed as a time trend in . Smoothed curves are computed by R’s ggplot2 package.

2 All regression models passed the Breusch Pagan Test for heteroscedasticity and robustness checks.

References

- Abdullah, W. J., & Kim, S. (2020). Singapore’s responses to the COVID-19 outbreak: A critical assessment. The American Review of Public Administration, 50(6–7), 770–776. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074020942454

- Abramowitz, S. A., McLean, K. E., McKune, S. L., Bardosh, K. L., Fallah, M., Monger, J., Tehoungue, K., & Omidian, P. A. (2015). Community-centered responses to Ebola in urban Liberia: The view from below. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 9(4), e0003706. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0003706

- An, B. Y., & Tang, S. Y. (2020). Lessons from COVID-19 responses in East Asia: Institutional infrastructure and enduring policy instruments. The American Review of Public Administration, 50(6–7), 790–800. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074020943707

- Asokan, A. (2020, June 10). COVID-19: New migrant worker dorms step in the right direction, say support groups – but could more be done? CNA. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/covid-19-new-migrant-foreign-worker-dorms-singapore-twc2-12818890

- Bavel, J., Baicker, K., Boggio, P. S., Capraro, V., Cichocka, A., Cikara, M., Crockett, M. J., Crum, A. J., Douglas, K. M., Druckman, J. N., Drury, J., Dube, O., Ellemers, N., Finkel, E. J., Fowler, J. H., Gelfand, M., Han, S., Haslam, S. A., Jetten, J., … Willer, R. (2020). Using social and behavioral science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(5), 460–471. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z

- Bish, A., & Michie, S. (2010). Demographic and attitudinal determinants of protective behaviors during a pandemic: A review. British Journal of Health Psychology, 15(4), 797–824. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/135910710X485826

- Blair, R. A., Morse, B. S., & Tsai, L. L. (2017). Public health and public trust: Survey evidence from the Ebola Virus Disease epidemic in Liberia. Social Science & Medicine, 172, 89–97. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.11.016

- Cheng, E. W. (2020). United front work and mechanisms of countermobilization in Hong Kong. The China Journal, 83(1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1086/706603

- Cher, A. (2020, March 31). Countries in lockdown should do what Singapore has done, says coronavirus expert. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/31/countries-in-lockdown-should-try-what-singapore-is-doing-coronavirus-expert.html

- Chia, O. (2020, April 9). MOM working to improve food for quarantined foreign workers. The New Paper. https://www.tnp.sg/news/singapore/mom-working-improve-food-quarantined-foreign-workers

- CIVICUS. (2020, June 24). Civic space restrictions continue unabated in Singapore despite COVID-19 pandemic, as election looms. CIVICUS. https://monitor.civicus.org/updates/2020/06/24/civic-space-restrictions-continue-unabated-singapore-despite-covid-19-pandemic-election-looms/

- Cowling, B. J., Ali, S. T., Ng, T., Tsang, T. K., Li, J., Fong, M. W., Liao, Q., Kwan, M. Y., Lee, S. L., Chiu, S. S., Wu, J. T., Wu, P., & Leung, G. M. (2020). Impact assessment of non-pharmaceutical interventions against coronavirus disease 2019 and influenza in Hong Kong: An observational study. The Lancet Public Health, 5(5), e279–e288. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30090-6

- Easton, D. (1975). A re-assessment of the concept of political support. British Journal of Political Science, 5(4), 435–457. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400008309

- Green, J., & Jennings, W. (2012). Valence as macro-competence: An analysis of mood in party competence evaluations in Great Britain. British Journal of Political Science, 42(2), 311–343. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123411000330

- Greer, S. L., King, E. J., da Fonseca, E. M., & Peralta-Santos, A. (2020). The comparative politics of COVID-19: The need to understand government responses. Global Public Health, 15(9), 1413–1416. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1783340

- Han, E., Tan, M., Turk, E., Sridhar, D., Leung, G. M., Shibuya, K., Asgari, N., Oh, J., García-Basteiro, A. L., Hanefeld, J., Cook, A. R., Hsu, L. Y., Teo, Y. Y., Heymann, D., Clark, H., McKee, M., & Legido-Quigley, H. (2020). Lessons learnt from easing COVID-19 restrictions: An analysis of countries and regions in Asia Pacific and Europe. The Lancet, 396(10261), 1525–1534. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32007-9

- Hartley, K., & Jarvis, D. S. (2020). Policymaking in a low-trust state: Legitimacy, state capacity, and responses to COVID-19 in Hong Kong. Policy and Society, 39(3), 403–423. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2020.1783791

- Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute. (2020, January 31). PORI releases popularity of CE and SAR government and public sentiment index. https://www.pori.hk/press-release/2020/20200131-eng

- Jang, W. M., Kim, U. N., Jang, D. H., Jung, H., Cho, S., Eun, S. J., & Lee, J. Y. (2020). Influence of trust on two different risk perceptions as an affective and cognitive dimension during Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) outbreak in South Korea: Serial cross-sectional surveys. BMJ Open, 10(3), e033026. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033026

- Kathleen. (2020, February 24). Migrant workers NGO voices over impact of Covid-19 outbreak on rights of migrant workers. The Online Citizen. https://www.onlinecitizenasia.com/2020/02/24/migrant-workers-ngo-voices-over-impact-of-covid-19-outbreak-on-rights-of-migrant-workers/

- Kavanagh, M. M., & Singh, R. (2020). Democracy, capacity, and coercion in pandemic response: COVID-19 in comparative political perspective. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 45(6), 997–1012. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-8641530

- Koh, D. (2020). Migrant workers and COVID-19. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 77(9), 634–636. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2020-106626

- Lee, F. L. F., Yuen, S., Tang, G., & Cheng, E. W. (2019). Hong Kong’s summer of uprising: From anti-extradition to anti-authoritarian protests. China Review, 19(4), 1–32. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26838911

- Leetaru, K., & Schrodt, P. A. (2013). GDELT: Global data on events, location, and tone, 1979–2012. International Studies Association Annual Conference. http://data.gdeltproject.org/documentation/ISA.2013.GDELT.pdf

- Legido-Quigley, H., Asgari, N., Teo, Y. Y., Leung, G. M., Oshitani, H., Fukuda, K., Cook, A. R., Hsu, L. Y., Shibuya, K., & Heymann, D. (2020). Are high-performing health systems resilient against the COVID-19 epidemic? The Lancet, 395(10227), 848–850. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30551-1

- Marques, C. F. (2020, February 9). Hong Kong is showing symptoms of a failed state. loomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2020-02-09/coronavirus-hong-kong-shows-symptoms-of-a-failed-state

- Miao, Q., Schwarz, S., & Schwarz, G. (2020). Responding to COVID-19: Community volunteerism and coproduction in China. World Development, 137, 105128. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105128

- Ministry of Manpower. (2020a). Foreign workforce numbers. Ministry of Manpower. https://www.mom.gov.sg/documents-and-publications/foreign-workforce-numbers

- Ministry of Manpower. (2020b, April 17). Inter-agency taskforce coordinating NGOs’ efforts to support the well-being of foreign workers. Ministry of Manpower. https://www.mom.gov.sg/newsroom/press-releases/2020/0417-inter-agency-taskforce-coordinating-ngos-efforts-to-support-the-well-being-of-foreign-workers

- Oksanen, A., Kaakinen, M., Latikka, R., Savolainen, I., Savela, N., & Koivula, A. (2020). Regulation and trust: 3-month follow-up study on COVID-19 mortality in 25 European countries. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 6(2), e19218. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2196/19218

- Parker, R. G. (2009). Civil society, political mobilization, and the impact of HIV scale-up on health systems in Brazil. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 52(Suppl 1), S49–S51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181bbcb56

- Reporters Without Borders. (2020). World Press Freedom Index: “Entering a decisive decade for journalism, exacerbated by coronavirus”. Reporters Without Borders. https://rsf.org/en/2020-world-press-freedom-index-entering-decisive-decade-journalism-exacerbated-coronavirus

- Terpstra, T. (2011). Emotions, trust, and perceived risk: Affective and cognitive routes to flood preparedness behavior. Risk Analysis, 31(10), 1658–1675. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01616.x

- TWC2. (2020, April 3). COVID-19: The risks from packing them in. TWC2. http://twc2.org.sg/2020/04/03/covid-19-the-risks-from-packing-them-in/

- van der Meer, T. W. G. (2017, January 25). Political trust and the “crisis of democracy”. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.77

- Wan, K. M., Ka-Ki Ho, L., Wong, N., & Chiu, A. (2020). Fighting COVID-19 in Hong Kong: The effects of community and social mobilization. World Development, 134, 105055. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105055

- Woo, J. J. (2020). Policy capacity and Singapore’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Policy and Society, 39(3), 345–362. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2020.1783789