?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The Taiwan issue continually haunts WHO. However, before addressing Taiwan's inclusion into WHO, we first describe how the era in which WHO was founded, and WHO's resulting constitutional mandate, have focused the Organisation's work on infectious disease eradication. Narrowing in on pandemic management – one aspect of infectious disease eradication – we describe what WHO can offer. These two sections allude to what Taiwan is excluded from. Using Taiwan's COVID-19 experience as a case study, Taiwan's successful management suggests that it is excluded from little, and thus marginally benefits in terms of public health. Yet, there are beneficial political gains in its call for inclusion. Taiwan's recent leveraging and amplification of its COVID-19 success story is thus an extension of its health diplomacy. Extending the call for inclusion online captures a novel digitised health diplomacy effort from Taiwan. The present study computationally analyses press-release and Twitter data to understand how Taiwanese government engages in these channels to frame and respond to the Taiwan/WHO issue. We find that Taiwan brands and propagates a ‘Taiwan Model’ through hashtags that revolve around coordination and solidarity as opposed to exclusion, indirectly criticising WHO. The piece concludes by discussing the foundational weaknesses in WHO's pandemic management effort in contrast to Taiwan's successful effort despite exclusion. Although Taiwan's inclusion to WHO is improbable due to larger geopolitical factors, inclusion is not a zero-sum game, with potential bi-directional benefits and lessons that can fortify domestic health capacities in preparation for the next pandemic.

1. Introduction

Taiwan represents an inconvenience towards sovereign nations. Founded in 1912 on the mainland by Dr Sun Yat-Sen and retreating to Taiwan island following defeat from communist forces, the Republic of China (ROC) government has been the de facto government of the Island since 1949.Footnote1 Yet, under the One China framework permitting only one China to exist, Taiwan is left in a precarious position in international politics as a ‘Ghost Island’. Coined in 2009 by New Power Party member Kwok Kwun-Ying, the term laments Taiwan's existence on the ‘periphery of nations’ as it struggles to become a recognised country.

Yet, the liminality of being politically illegitimate, but functional nonetheless, allows Taiwan to exist dually as a nation and non-nation. As a nation, Taiwan participates through bi- and multilateral engagement with other institutions and countries when permitted. When unrecognised, the island's exclusion requires alternative pathways to integrate into the international stage. This integration oscillates Taiwan's position between the fringe-of-nations to ‘countryhood’; this oscillation challenging the foundational validity of institutions. Evidence of this can be ascertained from its management of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak.

Taiwan has successfully managed its COVID-19 outbreak thus far, and this has increased its visibility internationally. At the time of writing, the outbreak has spread to 219 countries and territories, infected 111 million people, caused 2.46 million deaths globally, disrupted international trade and travel, and curtailed economic activity and growth. In Taiwan, a population of 23.8 million people, 942 cases were reported, 9 deaths recorded, and domestic activities have continued without significant hindrance. While praiseworthy, this accomplishment has a spillover effect of bringing Taiwan to a collision course with The World Health Organisation (WHO), the main organisation for pandemic control. The Organisation has consistently excluded Taiwan's membership on the basis of recognising One China, relegating the island either to the periphery (as a World Health Assembly (WHA) observer) or to total isolation (refusing WHA observance). Taiwan balks annually at this rejection, advocating for its inclusion on grounds of inclusiveness and cooperation for public health matters. This palpable dissonance often erupts into controversies at flashpoints reminding WHO that the Taiwan Issue will continue to haunt the organisation. One particular example is on April 9, 2020, Dr Tedros Ghebreyesus, Director-General of WHO, openly criticised the Taiwan public for an online campaign which he had claimed was slanderous towards his name and ethnicity (World Health Organization, Citation2020). This reinvigorated unproductive political cross-fire and ‘spitspatting’ with the two interpretations of this micro-aggression polarising the Taiwan-WHO debate to its two extremities of supporters and non-supporters.

As ammunition for the Taiwan-WHO conflict, Taiwan leverages its COVID-19 experience in a strategic way. Taiwan's bid for greater WHO inclusion beginning 1997 follows along the trend of pushing for international organisation participation as a means for diplomatic gain (Yang, Citation2010); merely one pawn in the larger chess match of Taiwan-China relations. Through this lens, the motivations behind branding and advocacy of the island's COVID-19 management becomes clearer. Taiwan capitalises on the inherent dual nature of its COVID-19 story as a political jabbing tool, packaged and distributed as a triumphant public health narrative. These two streams – the political and the public health – occur simultaneously and are mutually beneficial, and have provided increased traction for Taiwan's bid for WHO membership.

Missing in the conversations on Taiwan and WHO, however, is deeper understanding of WHO's conceptualised role as an organisation and its concrete roles and shortcomings in pandemic management. With this understanding, one makes sense of what Taiwan misses out on, and what it does instead to compensate or retaliate. This paper addresses these two points in tandem. The article begins by discussing WHO's foundation – its ethos and regulations – for pandemic control, alluding to its inherent restrictions. Following, we analyse Taiwan's engagement with WHO during the COVID-19 pandemic. We continue with a computational media analysis on the leveraging of COVID-19 management as a diplomatic effort calling for Taiwan's inclusion, focusing on messaging through traditional (i.e. press releases) and novel channels (i.e. Twitter). The genesis of the #TaiwanCanHelp and #TaiwanIsHelping hashtags explores how Taiwan frames its success in COVID-19 management to promote its international status. This movement also illustrates how new technologies are used to extend diplomatic efforts to include that of digitised health diplomacy. In addition, it is an example how Taiwan needed to diversify and innovate its global health strategy to stay relevant as a result of its ‘impossible sovereignty’ problem. This insistence on international relevance yields power and agency for the Ghost Island, while also calling for greater cooperation between Taiwan and WHO.

2. WHO: History and pandemic control

2.1. History

The historical origins of WHO reflects the organisation's ethos. In the post-war period, several advocates (notably Mitrany, Citation1944) proposed that international organisations should exist and serve as apolitical and technical organisations providing specialised services. Unifying on function would avoid nation-states' duplication or competition for services in a fragile post-war period. This ‘functional approach’, whereby institutions served one function to meet social and economic needs, also developed parallel to socialised medicine and ‘health as a right’. Thus prior to the nascence of WHO, the post-war functionalist era had ascribed a vision for the Organisation to oversee all things health. The Constitution assigns a broad vision for WHO to address a range of health and health care issues anchored on the Constitutional motto of achieving a state of ‘complete physical, mental and social well-being'. However, delving further suggests that its foundational identity emphasised conceptualising ‘health’ as infectious disease eradication, as opposed to the more holistic goal in the Constitution's preamble. In the 1946 International Health Conference which birthed WHO, the Organisation would ‘have as their broad aim the more effective control and eventual eradication of disease’ (World Health Organization, Citation1948) and its ‘ultimate aim must be to wipe out the foci of these epidemics’ – referring to cholera, plague, smallpox, yellow fever, and typhus, the most pressing infectious issues at the time. Evidence of the ‘health eradication’ narrative is embedded also to Article 2 and 21 of its Constitution. The past programs or initiatives run in the early years of WHO – the Malaria Eradication Programme, Smallpox Eradication Programme, and Global TB Programme – all placed heightened priority of disease eradication as an immutable function delegated to WHO. Disease eradication extends to pandemic control. As the primary organisation in pandemic control, WHO inevitably faces heavy scrutiny during a pandemic. Thus, discussing pandemic management spotlights a blindspot potentially weakening its legitimacy, which this piece attempts.Footnote2

Further analysing the Constitution sheds light as to the institutional power WHO has, both politically and economically. Evidence of political control from Member States can be evidenced in the Constitution, Article 2. Article 2(c) stipulates that WHO's role is ‘to assist Governments, upon request, in strengthening health services’, and in Article 2(d), is to ‘furnish appropriate technical assistance and, in emergencies, necessary aid upon the request or acceptance of Governments’ (WHO Citation2005a). WHO's delegated power is thus only invoked following Member States' governments' requests for help, suggesting the priority of sovereignty of nation states to disease control (Kamradt-Scott, Citation2015a). Member States also exhibit economic control through financial restrictions. In Article 18(f), Member States, through the WHA, can ‘supervise the financial policies of the Organisation and review and approve the budget’ (World Health Organization, Citation2005a, p. 6), as well as ‘approve the budget estimates and apportion the expenses among the Members’ (World Health Organization, Citation2005a, p.14). These political and economic restraints imposed on WHO, in addition to the ascription of infectious disease eradication, relegated the importance of WHO's scope of work to working mostly as an organisation relying on its reputation for its technical expertise and coordination capacity to set normative standards on infectious disease control. The creation of the International Health Regulations (IHR) was a product of this ascribed role. This document, in addition to the Framework Convention for Tobacco Control, still stand as the only international legally binding frameworks empowering WHO to prevent the global spread of disease.

2.2. Pandemic control

The IHR aimed to prevent the spread of threatening communicable diseases of the time. These disease eradication strategies were intended not only to reduce the affliction of suffering from said diseases, but also more importantly to reduce disruptions to international trade. This bias towards trade and trade networks proved to be fundamentally at odds with the coordination mentality they wished to perpetuate. As evidenced by the low compliance towards IHR requirements early-on, Member States consistently ignored reporting duties out of fear of dis-embedding from international trade networks. Those same Member States were, however, quick to propose newer, rigid measures to prevent disease importation from poorer countries. With few incentives for the at-risk Member States to comply (to an agreement which they collectively negotiated), the IHR's utility was severely limited. Several reforms tailoring IHR's communicable disease control agenda were made, with a large reform accomplished in 2005 following SARS.Footnote3 The 2005 IHR attempts to strengthen collective defence against a public health threat by establishing new rules on the existing global outbreak alert and response system, in an extension of its infectious disease control agenda. Member States are required to improve surveillance and reporting of potential ‘public health emergencies of international concern (PHEIC)’ events to WHO while also verifying information regarding such events when requested by WHO, via nationally established contact points. Technical assistance from WHO provides guidance to Member States' on strengthening capacities in several core areas (e.g. legislation, financing, response, risk communication, human resource, laboratory, etc.) related to pandemic control.

We reiterate two points before proceeding. Firstly, WHO has an emphasised role on infectious disease eradication. Although WHO has several roles in public health coordination, the piece focuses on infectious disease management. Secondly, due to Member State restriction, it mainly executes this through intelligence coordination and policy advising. The IHRs strengthen this responsibility. The next section reviews a brief history of Taiwan and WHO, and assesses how Taiwan engages with the WHO/IHR on pandemic threats (i.e. PHEIC), using COVID-19 as a relevant case.

3. Taiwan: WHO, IHR, global health nexus

Progress on Taiwan's inclusion to WHO has ebbed and flowed with the course of cross-strait politics. Since 1997, Taiwan has arduously campaigned for inclusion into the WHA (Herington & Lee, Citation2014) on various humanitarian and scientific grounds.Footnote4 A diplomatic breakthrough was made in 2009 when Taiwan was invited by then Director-General Dr Margaret Chan to observe in the 62nd WHA as ‘Chinese Taipei’ under Dr Ma Ying-jeou's presidency, the island's then-leader representing the Kuomintang (KMT) Party – a more Beijing-friendly party. This brief detente was interrupted in 2011 with political disagreement as to the specific terms of Taiwan's participation, resurfacing underlying tensions. Cross-straits relations worsened in 2016 following the election of Dr Tsai Ing-wen of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) – a less Beijing-friendly party – and with this came the negation of Taiwan's WHA observership.

Although not bound by WHO regulations due to non-Member State status, Taiwan still complied with IHR. Leveraging Article 3, Section 3 of the IHR which states that ‘implementation of these Regulations shall be guided by the goal of their universal applicationFootnote5 for the protection of all people of the world’ (World Health Organization, Citation2005b, p.10), Taiwanese lobbyists attempted to establish contact with WHO. This was eventually accepted by the WHO in 2009 – the same year of WHA invitation – establishing a Contact Point specified by the IHR in Taiwan, giving Taiwan a further step into WHO. Further, Taiwan's participation in the IHR included allowing direct communication to WHO Secretariat; access to the secured Event Information Site (EIS); the bilateral flow of experts to and from Taiwan; and Taiwan's proposition of a public health expert for the IHR global roster (Taiwan Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2009).

Without formal Member State recognition, Taiwan proceeds to participate in global health outside of WHO as a de facto state. Taiwan leverages participation in multilateral forums and bilateral health cooperation efforts where possible. Donations to international agencies such as the Asian Development Bank (Asian Development Bank, Citation2020), Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum (Chien et al., Citation2012), and the Pan American Health Organisation (The Ministry of Foreign Affairs Republic of China (Taiwan), Citation2015) hint its economic willingness to contribute to a public health effort. Engagement with its soft allies – notably the United States and Japan – through educational and informational exchanges allow Taiwan broad access to informational exchanges. Bilateral aid in the form of medical missions, donations of supplies, and support in disasters for Taiwan's allies are managed directly by its International Cooperation and Development Fund (The Ministry of Foreign Affairs Republic of China (Taiwan), Citation2019). When roadblocks to bilateral aid were met for political reasons, Taiwan leveraged its NGO network as informal engagement channels for donating goods (Guilloux, Citation2009, pp. 48–52) (indeed, NGOs were instrumental in Taiwan's WHO observership bid, and at one point Taiwan thought of applying as an NGO observer to WHO). The necessity to capitalise on the non-state sector for engagement was and is a constant reminder to Taiwan and other countries of its fringe position – much to the indignation of the Taiwanese. The consequences of exclusion, though, are harmful insofar as if what the exclusion is from is something necessary. In other words, this indignation is warranted if WHO has something unique to offer. Since Taiwan has done well in developing its domestic public health system, there may be little additional public health utility upon joining as a Member State. However, there still exists large political leverage. For these reasons, Taiwan's call for inclusion as a WHA observer is an extension of its diplomatic and political efforts applied via its the health sector – often termed health diplomacy. Its COVID experience categorises into one of the many tools for implementing this agenda.

The sparring of politics and health is inevitable for Taiwan. Being a ‘functioning-state-sans-recognition’ renders everything Taiwan does an affront to the logic of ‘countries’ and their role in public health. Because of its anticipated exclusion and scrutiny for its actions, Taiwan copes in two ways. First, as stated, Taiwan thoroughly exhausts all potential traditional avenues for participating into the global health framework – establishing of IHR contact, bilateral engagements, relying on dialogue between the U.S. and Japan, and applying for WHO-observership as an NGO (the best foot-in to WHO allowing participation in internal discussions, side meetings, and lobbying). Second, Taiwan must innovate new ways to approach and forge global health engagement and cooperation to avoid being forgotten on the international stage. This consistent offensive position Taiwan finds itself in encapsulates a sort of grit-priming, whereby the dominance of more powerful states results in exclusion, yet primes the adaptation of domestic processes of less powerful states, creating new solutions to problems in the process, and a more resilient state(the 'grit'). Taiwan's historical exclusion from WHO can then be reframed as a primer which catalyses a stepwise adaptation on Taiwan's approach to public health and health diplomacy. No less is this true for Taiwan's COVID-19 story. The following section examines how Taiwan has capitalised on its COVID-19 success story and created a wave of digitised health diplomacy, triply advocating for WHO inclusion, asserting for global cooperation and its inclusion, and strengthening domestic legitimacy.

4. Taiwan and COVID-19

4.1. Overview

The economic and physical proximity between Taiwan and China would have suggested that Taiwan were to be heavily affected by the current pandemic. But, the fear of replaying the fate of SARS 2003 – whereby Taiwanese inexperience in pandemic management and lack of centralised coordination (Hsieh, Citation2003; Schwartz, Citation2012) led to 364 cases and 73 deaths – was a strong imprint transforming the regulatory anatomy which guided the quick response to COVID-19. Amending the Communicable Disease Control Act (CDC Act) in Taiwan and establishing the Central Epidemic Command Centre (CECC), which legally authorised consolidated power to MOH and Taiwan Centres for Disease Control (Taiwan CDC) to coordinate the pandemic effort, were few of many efforts in compliance with IHR and pandemic control following SARS (C. F. Lin et al., Citation2020b; Ministry of Health and Welfare ROC, Citation2019b). According to the Taiwan CDC, they learned about the ‘atypical pneumonia outbreak in Wuhan’ from an online forum in China discussing seven cases of this pneumonia through their own monitoring system (Ministry of Health and Welfare ROC, Citation2019c). Following this alert, Taiwan CDC contacted both the China Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC) and the IHR contact point to inquire into the epidemic situation and whether human-to-human transmission was occurring (Taiwan Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2020a). A response was received from the China CDC saying that experts had been dispatched to investigate. In addition, two medical officers from Taiwan CDC were dispatched to Wuhan to obtain more comprehensive information regarding the outbreak, indicating direct contact across the Taiwan Strait (Taiwan Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2020c). WHO responded only with indication that Taiwan's information was forwarded to experts (Taiwan Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2020b).

With the information stream throughout early January indicating a possibility of outbreak, Taiwan took to a suite of protective actions within the first month of international notification. On 31 December 2019, enhanced fever screening was implemented at all airports for inbound passengers. The same day, passengers that had been to Wuhan were identified through the linking of the unified National Health Insurance (NHI) and immigration systems. Those passengers were contacted about their travel history, evaluated for their health condition, and given health instructions. On-board quarantine was implemented for flights arriving from Wuhan, and a similar evaluation and health instructions were given (Ministry of Health and Welfare ROC, Citation2020a). Several press conferences were given by the MOH to update citizens and urge refrain from sharing unsubstantiated information and hearsay. Following the Wuhan mission, Taiwan classified the coronavirus as a Category V Communicable Disease (Ministry of Health and Welfare ROC, Citation2019a, Article 3) and activated the CECC (Article 17) on 20 January 2020 (Y. Lin et al., Citation2020), allowing them to coordinate the pandemic effort. They continued to implement preventive measures throughout January and February 2020 while monitoring the course of the epidemic (Wang et al., Citation2020). As the virus spread to more of Asia, the Middle East, and to Europe and the Americas, Taiwan increased its global engagement largely through supply donations and joint statements with informal allies (particularly the U.S.) (American Institute in Taiwan, Citation2020) to contain the now global threat. Around March 2020, Taiwan also began its bid for the WHA to be held in May 2020.

Noteworthy in Taiwan's COVID-19 journey is the proliferation of technology-based initiatives. For example, a ‘Mask Map’ was developed and contributed to by civilians as an open-source depository indicating regions where masks supplies were available. Through the assistance of Minister without Portfolio Audrey Tang (self-proclaimed Taiwan's ‘Digital Minister’), this map was integrated to the NHI Administration to establish an island-wide mask-distribution platform to consolidate allocation and rationing of masks, avoiding panic buying (P. Y. Chen et al., Citation2020). Another example was the premeditated drowning-out of the narrative around fake news, which has also been given legal authorisation through the Social Order Maintenance Act (Y. Lin et al., Citation2020). In a civic movement termed ‘Humour over Rumour’, civic hackers hijacked the proliferation process of fake news by burgeoning the web with memes and videos ridiculing the falsehood of fake news narratives (Tang et al., Citation2020). In addition, Taiwan FactChecker Centre, an organisation founded by the Association for Quality Journalism and Taiwan Media Watch, regularly quashed myths surrounding the outbreak (folk remedies, personal protection, virus origins, etc.) (Taiwan FactCheck Centre, Citation2020). The combination of these anti-fake news enterprises attempted a ‘psychological inoculation’ of the general public, desensitising them from sensationalist, inaccurate news (sensationalist media reporting was also blamed for Taiwan's chaos during SARS) (Schwartz, Citation2012). The disposition towards technological seepage into government processes likely arose from synchronous developments of democracy and technology in the 1990s and blossomed after social movements, such as the Sunflower Movement of 2014, and were shown to be more dynamic and flexible and open, thus amplifying civic participation. Taiwan has slowly stitched this into the fabric of its governance, weaving a digital democracy narrative into Taiwan's civil participation and governance. The nexus of this technology use, Taiwan's desire to participate in WHO for political gain, a successful pandemic track record, and an approaching WHA, all led Taiwan to surge its health diplomacy effort on the internet.

4.2. Methods

Flexing Taiwan's COVID-19 story to the international stage is one strategic effort to simultaneously promote good public health cooperation while advancing Taiwan's diplomatic agenda of international recognition through WHO participation. Due to its shrinking, formal diplomatic channels, and following the digitisation wave, the government has tapped into social media as an additional platform for international engagement in its COVID-19 fight. Through the behaviours of three actors of government – President Tsai Ing-Wen, Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA), and Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW) – we can see how the government of Taiwan leverages its COVID-19 experience and amplifies it through traditional (i.e. press releases and statements) and novel (i.e. Twitter) channels to call for inclusion. Both channels thus capture more broadly its health diplomacy effort. These findings are then discussed in context of the WHO-Taiwan debate.

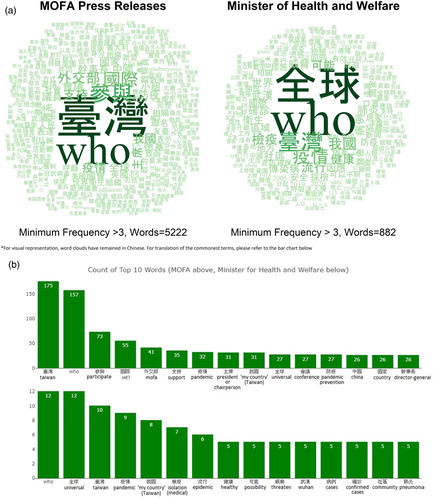

For the traditional channel, the texts of Minister of Health Dr Shih-Chung Chen's letter calling for Taiwan's inclusion, and a series of MOFA issued press releases from January to April 2020, are analysed. All of these were part of the petitioning effort for WHA observership in May 2020. For each arm of the Government, the texts are combined into a singular document called a corpus on which analysis is done. From this corpus, two word clouds and associated bar graphs are created to emphasise the most commonly used words, implying the message frame each arm uses on the Taiwan/WHO issue. A brief descriptive analysis on bilateral engagement is also included to round out the overall efforts the Taiwan government has taken to promote itself.

For the novel channel, we analyse Twitter, focusing on the hashtags ‘#TaiwanCanHelp’ and ‘#TaiwanIsHelping’. The hashtags highlight the willingness for Taiwan to 'help' in public health engagement. To understand their proliferation, which advocates for its WHO bid, we focus on the government and user engagement from the international public – the latter termed the ‘Twittersphere’. For the government, the corpus contains all tweets including the hashtags published by @iingwen, @MOFA_Taiwan, and @MOHW_Taiwan, during the period 15 December 2019 to 4 October 2020. These three accounts represent the President, MOFA, and MOHW, respectively, and are the representative faces of the fight against COVID-19 in Taiwan. For the international public, all of the tweets within the same time frame containing the two hashtags globally are scraped and compiled. Within this corpus, three sets of analyses are done to capture proliferation, messaging, and framing. First, a time-series analysis looks at the use of these hashtags over time to see in how the Government changes messaging quantum over time. Second, a sentiment analysis scores each tweet on the ten most common emotions, which allows an analysis of the emotional frames used. Third, Latent Dirichlet Analysis (LDA), a Bayesian modelling approach, is used to identify the most salient, underlying topics that arise from the tweet corpus. Both the sentiment analysis and the LDA are done to compare the emotions and topics that arise from the international public on Twitter.

4.3. Traditional health diplomacy

Dr Shih-Chung Chen issued a letter titled ‘Global Health Security – A Call for Taiwan's Inclusion’ on 21 April 2020 (S. C. Chen, Citation2020), having it published in 150 news agencies across 45 countries (both online and print) (Ministry of Health and Welfare ROC, Citation2020b). In the letter, a brief reiteration of Taiwan's management methods and the old adage of ‘disease knowing no borders’ and international inclusion is repeatedly stressed. Concurrently, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued various press releases and statements on its webpage from 23 January to 16 April 2020 concerning Taiwan's participation in WHO. According to the word cloud in (a) and bar chart in (b) comparing the content of Dr Shih-Chung Chen's speech with the contents of MOFA's press releases, the messages vary slightly in content, exhibiting a duality in message transmission. The MOFA discusses Dr Tedros Ghebreyesus and China more often (to rebuke the accusations made by the Director-General in April on Taiwan's alleged online racist attack towards him); calls more actively for participation as a member; and appeals to the world to support Taiwan's bid. The term ‘president’/‘chairperson’ used refers to various members of organisations who have close connections with Taiwan (e.g. Republic Senator Cory Gardner from Colorado, European Parliament Member Michael Gahler from Germany). In contrast, Dr Chen focuses on more neutral themes such as the intersectional importance of Taiwan, WHO, and the implications for health. Specifically, he focuses on the growing threat of infectious disease spread and how Taiwan's experience can be an essential part of that fight if allowed into WHO.

Figure 1. (a) Word cloud of most commonly used words for Dr Shih-Chung Chen, Minister of Health and Welfare, and MOFA's speeches regarding Taiwan's participation in the World Health Organisation. (b) Bar charts of top-15 most commonly used words for Dr Shih-Chung Chen, Minister of Health and Welfare, and MOFA's speeches regarding Taiwan's participation in the World Health Organisation.

Taiwan has also attempted to pursue international cooperation and extend bilateral assistance across different regions (The Ministry of Foreign Affairs Republic of China (Taiwan), Citation2020). Most of these engagements have taken the form of pandemic knowledge sharing and medical equipment donation, and have happened through Taiwan's hospital and academic network. An estimated 51 million masks have been donated worldwide since April 2020, with the count growing. Several videoconferences were held by major hospitals (Chi Mei Hospital, National Taiwan University Hospital) in addition to dispatching medical teams in an attempt for bilateral knowledge transfers. Underlying these cooperative acts is the concerted effort in donating only towards allies and ‘like-minded countries’ (western nations, diplomatic allies, and Southeast/South Asian countries). Undisputedly, due to various historical, social, and political reasons, the most important bilateral relationship Taiwan invests into is that with the United States (Chang, Citation2010). This much deeper relationship is reflected in the more pluralised and greater amounts of engagement between the two states. Taiwan-based Medigen Vaccine Biological Corporation signed an agreement with the U.S. National Institutes of Health signifying the latter would share with the former any necessary information to develop a vaccine. Millions of masks alone were donated to the United States in various waves at both federal and state levels. The epitome of this sensitive relationship culminated in a visit to Taiwan by U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services, Alex Azar, on 10 August 2020 to sign a health cooperation memorandum of understanding that strengthened bilateral medical and health cooperation. This visit was the highest-level U.S. official visit since the United States severed diplomatic ties with the Republic of China in 1979. Azar's meeting with Tsai not only reflected the deteriorating relationship across the Strait and the tripartite tension between the U.S., Taiwan, and China, it also representeda strategic diplomatic manoeuvre by Taiwan and the U.S. as a result of Taiwan's success. It is uncoincidental and symbolic that the first U.S. official to test the One China line came from the Department of Health and Human Services.

4.4. Digitised health diplomacy: TaiwanCanHelp, TaiwanIsHelping

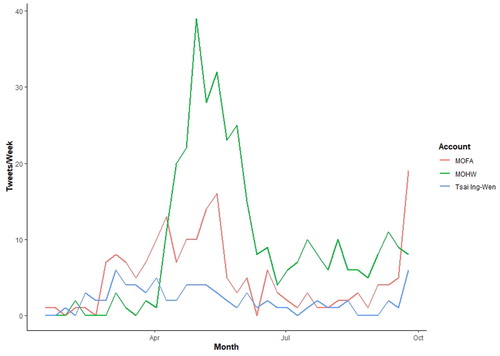

Prominence of the ‘#TaiwanCanHelp’ hashtag and its derivative, ‘#TaiwanIsHelping’ gained traction starting in March 2020 when Taiwan had relative control over the virus. shows how the use of these hashtags proliferated from government during the pandemic (n = 609). Notable is the large publication quantum starting April from all three users, but mainly MOHW, likely in response to Dr Tedros Ghebreyesus' calling out of Taiwan at a press conference with WHO, and in a final push for WHA observership. Thus, while MOFA took to press releases, MOHW took to Twitter. A brief qualitative analysis of the tweets in the April–May period indicate that the Government falsified the claims made by Ghebreyesus, followed by the thanking of partner countries who supported Taiwan. The use of these two hashtags had also begun to rise from Tsai and MOFA at the end of the dataset. Although this data is censored, the proliferation here can possibly be due to the U.N. General Assembly meeting starting September 15 (again, thanking partner countries), as well as in national promotion for Taiwan's national day – colloquially known as ‘Double-Ten’ (October 10, or 10/10).

Figure 2. Number of tweets per week from President Tsai Ing-Wen, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan.

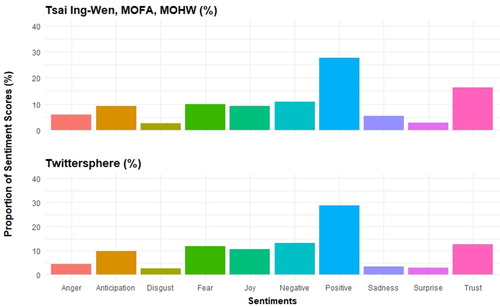

Within the government corpus, we also see that the majority of tweets carried a positive disposition, with the highest scores being in the ‘positive’ (27.72%) and ‘trust’ (16.26%) domains (). In the second tier of sentiments, sentiments related to ‘negativity’ (10.91%) and ‘fear’ (10.02%) scored similarly to positive emotions of‘ anticipation’ (9.26%) and ‘joy’ (9.19%). The reasons for this can be distilled from the scoring process and a comparison with the Twittersphere (n = 16,485). Through a sentiment score, a tweet is ranked across all 10 sentiments and given a score per sentiment based on the vocabulary used. As such, tweets can be composites of multiple or singular sentiments (or ‘multitonal’). Scores also differ between the government and Twittersphere. A low ‘anger’ score (4.52%, , p < .001), higher ‘negativity’ (12.54%

, p < .001), lower ‘trust’ (12.54%

,

), and higher ‘fear’ (11.8%

, p = .004) may indicate that the framing is conceptually different. Hashtags from the government includes sentiments of anger for exclusion, whereby when used the international public, the focus is on criticism and distrust (of other countries or international organisations) while promoting Taiwan. In short, the intentions for publishing, retweeting, or replying to a tweet, and the resulting message frame, between the two groups may be different despite an overall congruency. Sadness, surprise, and disgust ranked relatively low for both.

Figure 3. Proportion of sentiments expressed among corpus of tweets including ‘#TaiwanCanHelp’ and ‘#TaiwanIsHelping’ from the Government and the Twittersphere.

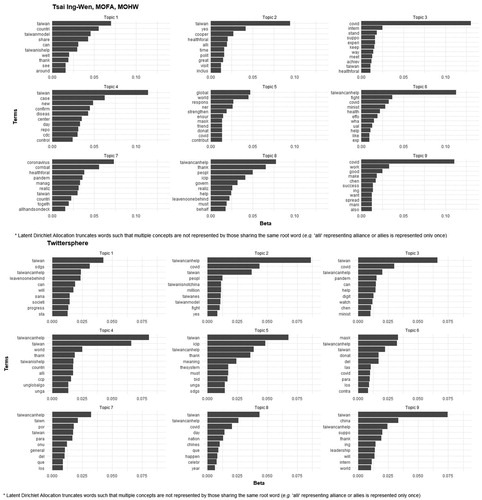

Aligning with the positive and trustworthy sentiment is the arising underlying topics from the Latent Dirichlet Allocation ((a,b)). These graphs shows the probability of the word being generated (the beta) by the underlying topic, with higher values indicating stronger correlation. Several things are noted. First, we can see that several words straddle the topics, a built-in component of the LDA. This is expected and thus focus should be on the cluster of words, not individual ones, in a topic. Secondly, LDA processing requires word strings to be collapsed to their basic root such that similar-root words do not appear twice (e.g. participate and participation are one concept). Third, although the number of topics presented is nine, this is a value chosen to display the strongest cohesion within a topic (strongest relationship among words). With this in mind, Topic 9 likely praises the Taiwanese model for disease control, honouring the leaders who have made it happen – ‘ing’ for Ing-Wen, ‘chen’ for the Minister of Health. The key term ‘mani’ refers to humanitarian, used around August 18 during World Humanitarian Day. Topic 5 specifically mentions ‘mask’, ‘donat’, and ‘contribut’, which highlights the point above of Taiwan's bilateral engagement through supply donation. Topic 6 is particularly noteworthy with words such as ‘ual’, ‘minist’, ‘health’, and ‘effort’, highlighting a virt‘ual’ forum effort of MOHW to share the Taiwanese experience. Other topics – Topic 1, 2, 3, 7, 8 – are active calls of acknowledging the Taiwanese model (Topic 1) and the necessity of ‘healthforall’, and ‘allhandsondeck’ (Topics 3 and 7). These calls are further strengthened by the rhetoric on cooperation and politics (‘cooper’, ‘polit’, Topic 2) as well as participation (‘icip’) and the concept of ‘leavenoonebehind’ (Topic 8). This running narrative on inclusivity can be considered a launched campaign against the supposed exclusivity of WHO due to Taiwan's exclusion.

Figure 4. (a) Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) analysis on underlying topics arising from the tweet corpus from the Government. (b) Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) analysis on underlying topics arising from the tweet corpus from the Twittersphere.

Themes about Taiwan's inclusion differ in the Twittersphere. Topics 1, 3, 9 calling for Taiwan's inclusion are in the context of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) of the U.N. (‘sdgs’),), emphasising the role of the Digital Minister (‘digit’) and Minister of Health (‘chen’, ‘minist’), and the leadership of Tsai (‘ing’). Some themes (2, 4, 5) actively support a Taiwan bid (‘bid’) at the U.N. general assembly, explicitly highlighting the differences between Taiwan (‘taiwanisnotchina’) and the Chinese Communist Party (‘ccp’). Echoing the SDG, this bid is an effort to reach U.N.'s global goals (‘unglobalgo’). Noteworthy in the Twittersphere are two topics (6, 9) that appear to have ‘mask’ and several Spanish words appear. Since the LDA was run in English, the numerous Spanish articles and prepositions appearing (‘los’, ‘para’) have little meaning and any associations are merely speculative. The presence of the Spanish words ‘contra’ – against – ‘mask’, and ‘donat’ (Spanish ‘donatar’ – to donate) may indicate a sizeable voice from Taiwan's Latin American allies in support and thanks for mask donations. One caveat from the Twittersphere data is that many tweets are possibly retweeting Taiwan-related organisations (the ‘embassy’ equivalents abroad) since many terms such as ‘sdg’, ‘unglobalgo’ are unlikely used by ordinary people. Removing retweets reveals 1864 novel, user-generated tweets whose sentiments are still in similar proportions to the dataset including retweets. This likely indicates that the narratives of retweets are aligned.

Who needs Taiwan?

This piece addresses several points. First is a discussion about WHO and IHR's difficulties, and thereby shortcomings, in pandemic management. This sets the scene for Taiwan's launching of a digital health diplomacy ‘narrative’, and helps us understand how and why the island specifically leveraged its successful COVID-19 pandemic response to advocate for inclusion in WHO. The following paragraphs discuss both points, and their potential implications for public health.

The first conclusion is that WHO has an in-built coordination and coordination problem during pandemics. Since establishment of the 2005 IHR, the WHO has trialled the new regulations through the declared PHEICs of H1N1, MERS, Ebola (multiple times), Zika, and COVID-19. Through each pandemic, WHO has collected mounting criticisms on its failures to contain the spread of disease. These shortcomings of WHO point to two more fundamental issues – membership based on statehood, and the ‘dilemma of disease control’ – that are built into the Organisation. The fact that WHO is a composite of 196 Member States with varying agendas and levels of influence will be a limiting factor in its operations. Economically or politically influential Member States – such as the U.S., the E.U. bloc, and China – are likely to have greater weight in the swing of the policy agenda compared to other Members. A direct consequent of balancing the needs of different Member States is thus the impossibility of severing its work from said Members' political agendas, which function as phantom limbs puppeteering the direction of WHO. For this reason, too, Taiwan's diplomatic allies advocating for the Ghost Island's inclusion into the U.N. framework is little more than political white noise, since it clashes with China's One China framework.

In parallel, there is the ‘dilemma of disease control’ that exacerbates this coordination problem and hinders WHO's work. The dilemma arises from the incongruous clash of cooperation, ‘keeping diseases outside borders’, and state sovereignty. States are quick to turn inwards to protect its own citizens (often through border controls) as opposed to coordinate among governments for disease control. These actions are justified both by invoking sovereignty to make domestic decisions, as well as signalling that governments are doing something – anything – to maintain public trust and thus domestic legitimacy. Many Asian states immediately closed borders or cut flights from at-risk regions during the first few months of their respective pandemics, despite no recommendation from the WHO (no less not from IHR) to do so. Those regions that did not were heavily lambasted by the public for limited border closures given the known risk from mainland China. The reflex of countries to isolate as opposed to cooperate, and its implicit justification on grounds of sovereignty and legitimacy, is thus a major roadblock for WHO to implement its mandate of cooperation and coordination, lest WHO should infringe on said sovereignty.

Since this ‘stalemate’ dynamic is a product of larger political factors and built into WHO's foundation, Member States should recalibrate what they expect from WHO within its capacity. An important task post-COVID-19 is strengthening domestic capacities to handle pandemics, since that is the direction they turn upon perceiving the threat of domestic spread. WHO should complement this preparedness effort, not be seen as the pedestal organisation to ‘solve’ the pandemic. Indeed, the difficult position WHO finds itself in has also reinforced its position largely as a norm-setting organisation. Where it fails – and has often failed – in a health-related sector, other organisations will likely arise to fill the void (e.g. GAVI for vaccines, UNAIDS for HIV), resulting in a pluralisation of public health institutions. Over-reliance on the Organisation should not be a substitute for developing domestic public health infrastructure, nor should it be an immediate scapegoat for the continued lack of governance around COVID-19. Taiwan's COVID-19 experience is an example of how WHO participation is not cure-all in pandemic management, and its case serves as a strong example for other countries moving forward post-COVID-19.

Due to these two issues, it appears Taiwan has a small window of opportunity to join and would only receive marginal gains if it were to do so. Recognition of the One China Policy and China's growing influence in international organisations mean Taiwan's participation call is stymied. Taiwan, meanwhile, has managed to develop a strong domestic pandemic management system post SARS, and it has also done so without membership in WHO. This system has so far shown to be resilient in the face of one of the century's largest threats. It has also managed to obtain necessary information regarding pandemics through informal channels and allies, weakening claims that Taiwan needs WHO for its information provision. Furthermore, the exclusion has also forced Taiwan's hand in diversifying its global health strategy. Since Taiwan has proven itself fully capable of managing the current pandemic without WHO, Taiwan's intentions advocating for WHO inclusion can be viewed as more politically-motivated rather than public health motivated.

Revisiting the dual-purpose of pushing for WHO inclusion through COVID-19 sheds light on why Taiwan attempted broadcasting its ‘success narrative’ through multiple channels. The Taiwan-WHO issue is a by-product of the larger geopolitical competition between China and Taiwan. Taiwan's path towards recognition or membership in WHO thus signifies its macropolitical struggle of its statehood, lamenting its ‘drifting’ status as a political ghost island. When analysed in context to the WHO shortcomings discussed, this reveals how the messages target WHO. The public health narrative and branding of the Taiwan Model, both in the traditional and social media, indirectly points out the shortcomings of WHO with regards to inclusion and solidarity. The calls for ‘health for all’, and ‘leaving no one behind’ repurpose WHO's own language on global health goals to rebuke its mandate stipulated in the Constitution and IHR while concurrently advocating for its inclusion through praising the Taiwan Model for doing those precise things. This branding is also beneficial for aligning the overall diplomatic effort from various actors, especially when taken to an informal forum such as the internet. Taking Taiwan's WHO push onto the digital world (i.e. digitisation) decentralises the authority needed to spread messages, thus pluralising the sources of spread. These sources subsequently circulate messages within their networks, positively feeding to an expanding network. Branding unifies the message propagation domestically; digitising the effort amplifies its reach in the international sphere (Nieh et al., Citation2020). This digitised health diplomacy effort thus triply aligns three agenda items: it promotes greater cooperation in public health, strengthens domestic legitimacy through building and disseminating a Taiwan brand, and calls for WHO membership. The increasing reach thus revitalises the discussion of its impossibility sovereignty issue at the battleground of WHO and public health, rebuking its status as a Ghost Island.

To conclude Taiwan's participation in WHO as unnecessary, however, is futile and dangerous for public health cooperation. Moreover, it also runs counter to the TaiwanIsHelping cooperation narrative and more importantly, the broader goal of diplomatic recognition. From discussion on recalibrating expectations from WHO, and accounting for Taiwan's experience in COVID-19, we conclude that support from the Organisation is not a panacea for pandemic control. Rather, it is one factor of many that may bolster a country's pandemic response, making it a necessary but insufficient condition that assists the pandemic effort.

If Taiwan joins WHO, both sides benefit. WHO is able to use Taiwan's participation as a catalyst for rebrand and reform. The thorniness of Taiwan's impossible sovereignty forces a paradigm shift in thinking on how the Organisation defines inclusivity given its own branding as a universal organisation (C. F. Lin et al., Citation2020a) – a blind spot which Taiwan's WHO diplomacy effort targets. Taiwan's roundabout engagements resulting from WHO's exclusion have highlighted that perhaps a more ‘trans-governmental’Footnote6 approach to public health may be a more responsive way to detail with crises (indeed, the digitised health diplomacy effort is an example of this (C. F. Lin et al., Citation2020a)). Expanding inclusion criteria to move beyond that of traditional Westphalian statehood allows freer engagements that potentially strengthen its technical capacity, spilling over to the other functions of WHO. Resulting from this process is also a potential re-accreditation or legitimation of its function in pandemic management. Taiwan can also benefit in multiple ways. One aspect is from reception of more timely information from WHO. Fluid information transfer at the outset has shown to be important since novel-agent pandemics unfold over the span of days. Taiwan also stands to gain from WHO by latching onto the organisation as an established, respected platform to amplify the promotion – and uptake – of its model, allowing unhindered collaboration with other states on buttressing health systems to face pandemics. In the post-COVID-19 era, countries and regions will likely strengthen infrastructure and their regulatory processes for pandemic preparedness. A consultation with successful regions, regardless of political status, will likely materialise, and Taiwan's invitation to that table can contribute to speeding global awareness and preparedness. Since China has historically been and may be a source of, novel pandemics in the future, Taiwan's position in not only physical but academic and experiential proximity make it a key strategic partner in pandemic management.

The nascent narrative arising from Taiwan's online campaign is that of cohesion, run countercurrent to the trend of geopolitical isolation. This enmeshes into public consciousness through the internet as part of its digital diplomacy paradigm and spurns the erasure that other nation states hope to bring it, and in doing so, positively feeds back to draw more attention. This process is emboldened by the experience of knowing the dangers of exclusion and sternly calling for inclusion as a result. Taiwan should continue advocacy through traditional and social media channels for its inclusion into WHO, emphasising the concepts of solidarity in time of crisis, and the Taiwan Model. Only then can countries and WHO actualise the potential symbiotic growth for all parties involved. This is the value of Taiwan's experience in COVID-19 management, and indeed how ‘#TaiwanCanHelp’.

Nomenclature/Notation

CDC Act = Communicable Disease Control Act of Taiwan

CECC = Central Epidemic Command Centre

China CDC = China Center for Disease Control and Prevention

DPP = Democratic Progressive Party

IHR = International Health Regulations (2005)

KMT = Kuomintang

NHI = National Health Insurance (Taiwan's Universal Health Care Programme)

Taiwan CDC = Taiwan Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

MOFA = Ministry of Foreign Affairs

MOHW = Ministry of Health and Welfare

SDG = Sustainable Development Goals

UN = United Nations

WHA = World Health Assembly

WHO = World Health Organisation

Acknowledgments

Dr Thorin Duffin and Kelsey Harris, for their critical eye on grammar and logic; Dr Kelley Lee, for comments and suggestions on structure, and connection to the FMPAT, an organisation advocating for Taiwan's inclusion in WHO; Mr Wong Hoi Wa, for tweet scraping and provision. The three anonymous reviewers who spent time to read and critically comment on the manuscript

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 ‘Taiwan’ will refer to Taiwan island, its outlying islands, and their administration by the ROC government

2 Although disease eradication is a main focus of WHO, it is multifunctional and still provides other services which fulfill the roles stipulated in the Preamble, and broadly the Constitution. Tensions and debates between biomedical and social approaches to international health cooperation are addressed elsewhere.

3 For a deeper discussion on previous revisions and sequences of events leading to the most recent IHR renewal, see Kamradt-Scott's chapter on revising the IHR(Kamradt-Scott, Citation2015b, pp. 106–107)

4 The process for Taiwan's WHO's bid is analysed elsewhere (Guilloux, Citation2009; Herington & Lee, Citation2014)

5 The term ‘universal application’ was explicitly included per request of Taiwan's diplomatic ally during Taiwan's bid for IHR membership (P. K. Chen, Citation2018)

6 Slaughter explores how the state ‘disaggregates into its component institutions, which increasingly interact principally with their foreign counterparts across borders’ in ‘trans-governmental’ networks with minimal supervision by ministries. These networks are structured and built on ‘peer-to-peer ties developed through frequent interactions rather than formal negotiation (Slaughter, Citation2005)

References

- American Institute in Taiwan (2020). U.S.-Taiwan joint statement. Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://www.ait.org.tw/u-s-taiwan-joint-statement/

- Asian Development Bank (2020). Asian development bank and Taipei, China: Fact sheet (Tech. Rep.). Asian Development Bank. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/27800/tap-2019.pdf

- Chang, J.l. J. (2010, June). Taiwan's participation in the World Health Organization: The U.S. “Facilitator” role. American Foreign Policy Interests, 32(3), 131–146. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10803920.2010.487381

- Chen, P. K. (2018). Universal participation without Taiwan? A study of Taiwan's participation in the global health governance sponsored by the World Health Organization. In Advanced sciences and technologies for security applications (pp. 263–281). Springer.

- Chen, S. C. (2020). Global Health Security – A Call for Taiwan's Inclusion (Tech. Rep.). Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of China (Taiwan). https://www.roc-taiwan.org/om_en/post/672.html

- Chen, P. Y., Liu, Y. C., & Hsuan, C. (2020). Mask map – Cooperation between government and community. September 30, 2020, from https://fightcovid.edu.tw/specific-topics/mask-map

- Chien, H. Y., Hsu, Y. C., Pan, L. Y., & Shih, C. S. (2012). An analysis of topics of APEC health projects and participation of APEC member economies in the projects during the post-SARS period. Taiwan Epidemiological Bulletin, 28, 87–98.

- Guilloux, A. (2009). Taiwan, humanitarianism and global governance. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Herington, J., & Lee, K. (2014, October). The limits of global health diplomacy: Taiwan's observer status at the world health assembly. Globalization and Health, 10(1), 71. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-014-0071-y

- Hsieh, Y. H. (2003, May). Politics hindering SARS work [3] (Vol. 423, No. 6938). Macmillan Magazines Ltd.

- Kamradt-Scott, A. (2015a). Introduction. In Managing global health security (pp. 1–20). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Kamradt-Scott, A. (2015b). New powers for a new age? Revising and updating the IHR. In Managing global health security (pp. 101–123). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Lin, Y., Hu, Z., Alias, H., & Wong, L. P. (2020). Knowledge, attitudes, impact, and anxiety regarding COVID-19 infection among the public in China. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 236. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00236

- Lin, C. F., Liu, H. W., & Wu, C. H. (2020a, August). Breaking state-centric shackles in the WHO: Taiwan as a catalyst for a new global health order. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3675481

- Lin, C. F., Wu, C. H., & Wu, C. F. (2020b, June). Reimagining the administrative state in times of global health crisis: An anatomy of Taiwan's regulatory actions in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. European Journal of Risk Regulation, 11(2), 256–272. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2020.25

- The Ministry of Foreign Affairs Republic of China (Taiwan) (2015). International cooperation and development report 2014 (Tech. Rep.).

- The Ministry of Foreign Affairs Republic of China (Taiwan) (2019). International cooperation and development report 2019 (Tech. Rep.). Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of China (Taiwan).

- The Ministry of Foreign Affairs Republic of China (Taiwan) (2020). Taiwan – a force for good in the international community Taiwan can help, and Taiwan is helping! Retrieved October 1, 2020, from https://www.mofa.gov.tw/en/cp.aspx?n=AF70B0F54FFB164B

- Ministry of Health and Welfare ROC (2019a). Communicable disease control act. Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://law.moj.gov.tw/ENG/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?pcode=L0050001

- Ministry of Health and Welfare ROC (2019b). Communicable disease control act: Legislative history. Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://law.moj.gov.tw/ENG/LawClass/LawHistory.aspx?pcode=L0050001

- Ministry of Health and Welfare ROC (2019c). In early dawn, Taiwan CDC learned from online sources that there had been at least 7 cases of atypical pneumonia in Wuhan, China. At 8am, Taiwan CDC contacted the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention to confirm about the latest epidemic situation. Retrieved September 30, 2020, from https://covid19.mohw.gov.tw/en/cp-4868-53673-206.html

- Ministry of Health and Welfare ROC (2020a). Holding a press conference to provide COVID-19 updates, initiating border control according to standard operating procedures, and onboard inspections for direct flights from Wuhan. Retrieved September 30, 2020, from https://covid19.mohw.gov.tw/en/cp-4868-53684-206.html

- Ministry of Health and Welfare ROC (2020b). Taiwan can help, and Taiwan is helping! Retrieved October 1, 2020, from https://covid19.mohw.gov.tw/en/cp-4789-53866-206.html

- Mitrany, D. (1944). A working peace system: An argument for the functional development of international organization. International Affairs, 20(1), 109–109. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3016490

- Nieh, A., Chang, C. C., Chang, K., Du, R., & Lin, Z. (2020). Media coverage. Retrieved October 7, 2020, from https://taiwancanhelp.us/en/media/

- Schwartz, J. (2012, September). Compensating for the ‘Authoritarian advantage’ in crisis response: A comparative case study of SARS pandemic responses in China and Taiwan. Journal of Chinese Political Science, 17(3), 313–331. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-012-9204-4

- Slaughter, A. M. (2005). A new world order. Princeton University Press.

- Taiwan Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2009). WHO agrees to include Taiwan in the implementation of IHR. Retrieved September 17, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov.tw/En/Bulletin/Detail/ijDOgFLf8UnPhkPCa7yYeg?typeid=158

- Taiwan Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020a). In response to pneumonia outbreak in Wuhan, China and related test results, Taiwan CDC remains in touch with China and World Health Organization and Taiwan maintains existing disease control and prevention efforts. Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov.tw/En/Bulletin/Detail/4N96uF-2yK-d7dEFFcwa0Q?typeid=158

- Taiwan Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020b). The facts regarding Taiwan's email to alert WHO to possible danger of COVID-19. Retrieved September 30, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov.tw/En/Bulletin/Detail/PAD-lbwDHeN_bLa-viBOuw?typeid=158

- Taiwan Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020c). Two experts from Taiwan visit Wuhan to understand and obtain information on severe special infectious pneumonia outbreak; Taiwan CDC raises travel notice level for Wuhan to Level 2. Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov.tw/En/Bulletin/Detail/jFGUVrlLkIuHmzZeyAihHQ?typeid=158

- Taiwan FactCheck Centre (2020). COVID-19 section. Retrieved September 30, 2020, from https://tfc-taiwan.org.tw/topic/3826

- Tang, A., Biello, D., & Rodgers, W. P. (2020). How digital innovation can fight pandemics and strengthen democracy. TED2020.

- Wang, C. J., Ng, C. Y., & Brook, R. H. (2020, April). Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan: Big data analytics, new technology, and proactive testing (Vol. 323, No. 14). American Medical Association.

- World Health Organization (1948). Official records of the World Health Organization No. 2 (Tech. Rep.). World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (2005a). Constitution of the World Health Organization. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/governance/eb/who_constitution_en.pdf?ua=1

- World Health Organization (2005b). International health regulations (2005) (Tech. Rep.). http://www.who.int/ihr/publications/9789241580496/en/

- World Health Organization (2020). COVID-19 virtual press conference – 8 April, 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/transcripts/who-audio-emergencies-coronavirus-press-conference-full-08apr2020.pdf?sfvrsn=267145f5_2

- Yang, C. M. (2010, September). The road to observer status in the world health assembly: Lessons from Taiwan's long journey. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1729459