ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic has overwhelmed health systems around the globe, and intensified the lethality of social and political inequality. In the United States, where public health departments have been severely defunded, Black, Native, Latinx communities and those experiencing poverty in the country’s largest cities are disproportionately infected and disproportionately dying. Based on our collective ethnographic work in three global cities in the U.S. (San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Detroit), we identify how the political geography of racialisation potentiated the COVID-19 crisis, exacerbating the social and economic toll of the pandemic for non-white communities, and undercut the public health response. Our analysis is specific to the current COVID19 crisis in the U.S, however the lessons from these cases are important for understanding and responding to the corrosive political processes that have entrenched inequality in pandemics around the world.

The political geography of racism is the pre-existing and ongoing condition to which scholars and policymakers must attend in order to interrupt the devastation being wrought by this politically-discriminating virus. (18)

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has intensified the lethality of social and political inequality. In the United States, Black, Native, Latinx communities and those experiencing poverty in the country’s largest cities are disproportionately infected, and disproportionately dying (CDC, Citation2020). Based on our collective work in three U.S. cities (San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Detroit) we analyse how the political geography of racialisation calibrated the conditions for the COVID-19 crisis, and undercut the public health response. Through historically-informed ethnographic cases, we explore how racial and spatial politics determined the spread of COVID-19, its severity, and the strategies used to respond. With our fine-grained analyses of local geographies, we aim to apprehend how the politics of racial inequality are being extended by this pandemic. Undoubtedly, COVID-19 is deepening inequality the world over; but the local contours of that inequality matter to an informed understanding and effective response.

Our ethnographic analysis places the COVID19 crisis within the context of the political economy of racialisation in America (Davis & West, Citation2016; Robinson, Citation2008; Robinson & Kelley, Citation2000). Through this scholarship, we can more adequately apprehend how the vulnerability of non-white populations to comparatively high levels of COVID-19 infection and death stems from their exposure to other forms of racial exclusion, labour exploitation, discrimination and xenophobia. Black Americans have endured a long trajectory of racialised exploitation and dispossession on U.S. soil and as a result, exhibit the worst general health profiles among U.S. racial/ethnic groups. Black Americans have been subjected to generations of forced labour, Jim Crow and racial segregation, state sponsored violence, mass incarceration, and theft of homes and land (Blauner, Citation1972; Du Bois, Citation2007; Feagin, Citation2006; Hernández, Citation2017; Horne, Citation2017). Latinx Americans were also subjected to deep forms of racism and draconian immigration policies implemented in the late nineteenth and twentieth century U.S (Lee, Citation2002). While Latinx populations in the U.S. from North, Central and South America with low socio-economic backgrounds generally have better overall health profiles than African Americans in terms of birth outcomes and disease rates (Danaei et al., Citation2010; Dwyer-Lindgren et al., Citation2017; Lassetter & Callister, Citation2009), the racist stance of U.S. policy has relegated Latinx groups to some of the lowest rungs of the U.S. work sector. Farmworkers, domestic workers, and blue-collar labourers as well as other essential workers are extremely vulnerable to the spread of the disease due to the nature of their jobs. In addition, these groups have been exposed to increasing criminalisation through punitive immigration policies which also has the effect of limiting their access to health care at a time when the population is in dire need of testing, contract tracing and health care as well as social services such as support for housing, nutrition, and income supplementation.

To understand how instantiations of racialisation have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis, we must recognise how these histories and their social and health effects entrench inequalities in the present. Drawing on an interdisciplinary body of scholarship, we contend it is necessary to recognise that race is a social technology: ‘something more than skin colour or biophysical essence, but precisely as those historic repertoires and cultural, spatial, and signifying systems that stigmatise and depreciate one form of humanity for the purposes of another’s’ (Singh, Citation2005). We draw attention to the spatial embeddedness of race in the urban landscape, reproduced as differential proximity to transportation, jobs, services, and pollutants. We think with geographer Juan De Lara, who has written insightfully about the ways that transformations in global capitalism articulate with local social and spatial relations, resulting in the constant “reterritorialization of race” (De Lara, Citation2018). We also engage with the work of several scholars who theorise the linkages between racial violence, neoliberal politics, and capitalist accumulation (see also Tyner, Citation2019), including Jodi Melamed (Citation2015) who observes, capital “can only accumulate by producing and moving through relations of severe inequality among human groups … and racism enshrines the inequalities that capitalism requires.” Extending this scholarship, we explore how the political geography of racialisation potentiated the COVID-19 crisis, including by exacerbating the social and economic toll of the pandemic for non-white communities, and undercut the possibility of an effective public health response.

Case studies: Three global cities in the United States

Our ethnographic research stitches together data from the histories of cities, epidemiological reports, and clinical observant participation in urban community and safety net hospitals during the COVID-19 crisis. Learning from those with whom we work and care in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Detroit, our topics of analysis range in scope to examine how the political geography of racialisation has impacted non-white people during the COVID-19 pandemic and stifled an effective public health response.

City of San Francisco: District 10

San Francisco was the first major U.S. city to declare a State of Emergency on 25th February 2020, even before the WHO officially characterised COVID-19 as a pandemic (and President Trump issued his Proclamation) (The White House, Citation2020). At that point, there were only 57 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the U.S., nine in the Bay Area, and none originating in the city of San Francisco. Yet, Mayor London Breed recognising the gravity of what was to come, announced at a press conference, ‘By declaring a state of emergency, we are prioritising the safety of our communities by being prepared’ (Fracassa, Citation2020).

Things moved quickly after this. On 5th March, the city was found to have its first two cases. A week later, SF Unified School District announced its closure, gatherings of more than 100 people were banned the following day, and by 16th March, San Francisco and the surrounding five bay area counties were the first to issue a mandatory ‘Shelter in Place’ order. Three days later, Governor of California, Gavin Newsom, followed the Bay Area’s lead by mandating a state-wide ‘Stay at Home’ order.

It may not come as a surprise that San Francisco, a self-proclaimed liberal bastion, was centrally organised and responsive from the very beginning. This vigilant response has been celebrated in national news for contributing to the lowest COVID-19 mortality rate of any city in the United States. What is less immediately apparent is the way decades of economic dispossession and displacement for Black and Brown residents of the city left this subset of the population vulnerable despite early actions taken by San Francisco’s Black woman mayor.

Savannah Shange (Citation2019) describes this paradox of social reform intent and anti-Black impact in San Francisco as ‘carceral progressivisms’ (14). Following Loic Wacquant (Citation2000), the carceral is conceptualised as a continuum extending beyond the jail into the toxic spaces where Black people are made to live. Even as a progressive politics is always explicitly announced – via Black Lives Matter signs and powder pink and blue transgender flags displayed in the windows of multimillion-dollar Queen Anne homes – the City’s racial geography exposes a history of state violence, racial exclusion and an ever-present, always-implied anti-Blackness. As Shange writes, ‘the acknowledgement of systemic injustice serves as an alibi for the retrenchment of that very system’ (14). A series of policies and practices – from forced evictions and redlining to segregated public housing and gentrification driven by speculative real estate markets – has concentrated San Francisco’s dwindling Black populationFootnote1 into neighbourhoods of the south-eastern corner of the city, correlating with District 10 (Brahinsky, Citation2014; Broussard, Citation1993; Moore et al., Citation2019).

Geographically isolated from the rest of the city, District 10 is also the location of the Hunter’s Point toxic Superfund site and heavily impacted by ongoing environmental contamination due to close proximity to landfills, heavy industry, power plants, and highway traffic (Bayview Hunters Point Mothers Environmental Health & Justice Committee, Huntersview Tenants Association, Citation2004). Scarce access to grocery stores and public transportation round out what makes a perfect storm of health risk factors. Residents of District 10 are well aware of the toxicity to which they are exposed, and it often comes up in conversations around their health. Studies have confirmed this local knowledge, revealing that rates of asthma, breast cancer, leukaemia, and chronic diseases are considerably higher in District 10 than in other regions of the city. This is a list that is almost identical to the CDC’s list of ‘serious medical conditions’ that make a person at risk for severe morbidity and mortality from COVID-19. In other words, like compounding interest, risk accumulates in District 10, leaving its residents particularly vulnerable to the impact of COVID-19.

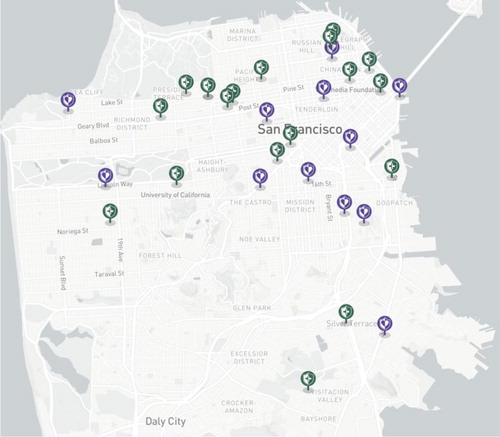

Yet in mid-April, when San Francisco opened its first two ‘CityTestSF’ sites, neither was located in District 10. A map of the testing sites available in the city in Fall of 2020 exposes the ways geographic exclusion creates racial exclusion, and does the job without necessarily being explicit. Of the 30 public and private testing sites available to San Francisco residents, only three are in the south-eastern neighbourhoods of the city (). One is available only to patients of that particular clinic, a second is inconveniently open only twice a week for 4 or 6 hours at a time, and the third is housed in a public health centre with an historically uneasy relationship with its surrounding constituency. Here, the geography of the city – including its transportation infrastructures and its historical legacies – directly influences the efficacy of coronavirus testing, even where testing sites are ‘made available.’

Figure 1. Available COVID-19 testing sites in San Francisco as of October 2020 (https://datasf.org/covid19-testing-locations).

In recognition of the unique challenges faced in south-eastern San Francisco and the city’s disproportionate response, District 10 supervisor Shaman Walton began holding open meetings via Zoom early in the pandemic. These ‘Bayview Resilience’ meetings are held weekly for district residents to be both informed of the rapidly evolving situation and connected to systems of support. These are also meetings where residents are given the opportunity to express their concerns. Access – or more precisely lack thereof – is a central issue in many of these meetings: access to PPE for the at-risk and essential workers; access to food banks for the homebound elderly; access to housing for the growing population living between shelters and tents; access to an incredible array of resources that appeared, seemingly overnight, in the city’s previously ever-underfilled coffers; and, of course, access to COVID-19 testing. This later concern, though interestingly not the most pressing for residents themselves, gained considerable attention likely because it overlapped with both the city government’s desire to contain the disease spread and the research interests of the medically world-renown public institution, UCSF. The university’s footprint in the city, geographically and politically, again complicates the politics of community testing, even as it established and funded many testing programmes.

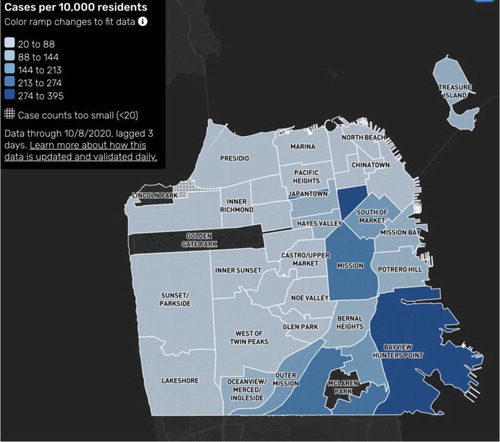

While these virtual meetings were taking place, researchers at UCSF were gearing up to get a better sense of the landscape of COVID-19 in south-eastern San Francisco. A team of physician-scientists were looking to replicate in District 10 a recent UCSF study that had taken place in the Mission neighbourhood, which is home to a majority of San Francisco’s Latinx population. At the first meeting, which was intended by the study investigators to be used to decide which census tract in District 10 would be the focus on the study, the conversation became unexpectedly tense. Attendees expressed their discontent with the study’s focus on testing, the study’s methodological constraints limited to one or two census tracts, and the city’s incessant demand for data as a condition of the resources it provides. One attendee remarked, ‘We don’t need the coronavirus map to tell us the problems that we have in the community because it’s the same map that shows diabetes, it’s the same map that shows unemployment, it’s the same map that shows, you know, disconnection to the rest of the city because of the poor transit. It’s all the same information.’ (). While the UCSF researchers were concerned with getting data that was legible in ways that would allow them to make a claim about shifting city resources to areas where they were most needed, Bayview residents at the meeting were critical of how the immediate research goals did not seem to align with community needs.

Figure 2. Cases of COVID-19 per 100,000 resident by neighbourhood in San Francisco (https://data.sfgov.org/).

The meeting ended before a census tract could be decided as attendees made clear again that they did not need a study to tell them what they already knew about the map of San Francisco. Despite the objections raised, the study took place in two census tracts chosen largely by the researchers. Given the limited access to testing in this part of the city, residents had resigned themselves to supporting the study while still remaining ambivalent. As one attendee put it, ‘I am here to do this project however it turns out, but I am not going to stop telling you right now what you’re doing is setting something up to serve the institutions and the institutions do not serve or protect us.’

Against the backdrop of San Francisco as a ‘site of racialized difference’ (Shange, Citation2019, p. 39) par excellence, the uneven rollout of testing sites and subsequent battles for access in District 10 underscore existing claims about racial exclusion even as institutions like UCSF and the Department of Public Health perform inclusivity through progressive logics. After all, it seems the primary mode through which south-eastern San Francisco is invited to join the rest of the city is via participation in a research study.

Though San Francisco has been exemplary in its early response to COVID-19 and the massive mobilisation of resources toward testing, the logics of carceral progressivism continue to inform the uneven distribution of these resources. Even more important to note for the case of San Francisco is how even a more equal distribution of resources would not necessarily be more just or enough to address histories of anti-Black policies and practices driven by racial capitalism. The racialising dialectic that has entrapped residents in an increasingly small, polluted, and disconnected corner of the city further complicates how residents’ access and experience any citywide efforts to address the impact of COVID-19. As residents of District 10 are well aware, it isn’t enough to study and map the disparities that exist, nor can an easy solution be found in increasing the number of testing sites in District 10 (though this is a reasonable start). Rather, San Francisco must be intentional about addressing legacies of displacement and dispossession by dismantling the violent and predatory policies that govern the historical and ongoing legal, yet anti-Black, distribution of resources and care.

Los Angeles county: South and East LA

As the pandemic has progressed, the epidemiology of the virus in Southern California has diverged from that of cities in the northern part of the state. The skyrocketing cases in Los Angeles have made the county a hotbed of coronavirus, nationally as well as globally. Much of the difference in how and where cases have spread can be traced to the local political geography of the city. The rising rates of incidence in LA also tell a story of worsening inequality patterned on ethnic lines, and radically different ways urban space has been racialised: a metropolis of sprawl, the region nonetheless concentrates immigrant and working class Latinx labourers in the kinds of crowded spaces where coronavirus thrives.

Indeed, Southern California’s reputation for urban sprawl belies the crowded living conditions experienced by many working class and immigrant Angelenos. The lethal combination of crowded housing and essential work that promotes viral exposure has contributed to an explosion of COVID-19 cases in Los Angeles county during the winter of 2020-2021, where 400,000 residents tested positive over the holiday season from Thanksgiving to New Year’s.Footnote2 Increased case counts inevitably led to rising morbidity and mortality rates. During this time period, the county’s intensive care units operated at zero or negative capacity and hospitals reported running of oxygen as deaths climbed to over 3600 (Lin & Money, Citation2021).

Latinx residents have absorbed the brunt of the virus’ impact. While they make up 39% of the California population, they represented 55% of COVID-19 cases and 46% of deaths. Latinx people in Los Angeles are also dying of COVID-19 at significantly younger ages. Among adults 39–45 years old, the disparities have been staggering (CA.gov, Citation2020), with Latinx young men and women making up 75% of the deaths for that age category.Footnote3 The unincorporated neighbourhood of East Los Angeles has become the ‘epicentre’ of the crisis (LA County Department of Public Health). East Los Angeles is 96.7% Latinx and one of the most densely housed areas in the county. It is also considered the birthplace of the Chicano movement in southern California if not in the whole U.S. (Romo, Citation1983). Other hotspots in the county include Boyle Heights, South Gate and Lynwood – all predominantly Latinx neighbourhoods.

Though officially deemed essential, in practice Latinx workers have often been treated as expendable in their workplaces. Disproportionately concentrated in low-wage and informal labour, the provision of protective equipment and COVID-19 testing has been lacking. This inequitable access to testing has been linked to extremely high mortality rates (Rubin-Miller et al., Citation2020). In fact, the death toll among working Latinx adults (ages of 18-64) has reached alarming heights, with fivefold increases between May and August (Hayes-Bautista et al., Citation2020).

The distribution of COVID-19 across LA county has been determined by decades of political violence, the marginalisation of immigrant communities, and geographic discrimination, which displaced African-American communities and funnelled Latinx people into East and South Los Angeles. Between 1980 and 2005, the Los Angeles metropolitan area lost 42% of its manufacturing jobs, dealing a severe economic blow to African American men who were heavily employed in this sector. This led to massive unemployment and forced working-age African Americans out of South Los Angeles (Friedhoff et al., Citation2020; Kim, Citation2008). During this period, thousands of Guatemalan and Salvadoran immigrants fleeing the violence wrought by President Reagan’s anti-communist interventions in Central America took up residence throughout Los Angeles’ poorest neighbourhoods. Denied asylum status and a path to legal residency, many were relegated to working in LA’s growing informal economy and non-unionised light manufacturing sectors (Hamilton & Chinchilla, Citation2001; Kim, Citation2008). During this period, areas such as South Los Angeles, once heavily inhabited by African Americans, began to be bastions for the city’s growing Latinx population (Hondagneu-Sotelo, Citation2014). However, they have only limited ‘Temporary Protected Status’, which the Trump Administration sought to revoke (Miyares et al., Citation2019).

These same neighbourhoods have become very attractive for many of the world’s largest companies – especially those involved in rapidly expanding just-in-time global commodity chains that produce and distribute most of the world’s goods such as Amazon and Walmart (De Lara et al., Citation2016; Gereffi & Christian, Citation2009). The vast pool of flexible labour and proximity to the San Pedro Bay port complex, which handles more containers per ship call than any other complex in the world, has transformed the Los Angeles and Inland Empire region into the warehouse capital of the country for the commodity and logistics industries (Bonacich & Wilson, Citation2008). About one-third of all warehouse jobs are occupied by Latinx immigrants (Gutelius & Theodore, Citation2019). As with agricultural labour, warehouse workers are overwhelmingly employed through temporary staffing agencies (Gutelius & Theodore, Citation2019). Along with marginalised citizenship status, so-called temp labour has become part of a regional ‘matrix of exploitation’ that renders Latinx labour expendable and pliable (Allison et al., Citation2018).

These processes of marginalisation and exploitation have placed workers at increased risk for COVID-19, with little recourse for action – to stop work or prevent illness. One of our authors cared for a man who navigated this labour dilemma during the pandemic. Mr Gonzalez, a 43-year-old primarily Spanish speaking man from Mexico was working in a southern California factory producing machinery parts for military use, when he initially learned he was at risk. His supervisor announced that six out of the company’s 150 employees had tested positive for COVID-19. Despite Mr Gonzalez’s vigilance and the vigilance of his co-workers to continuously wear masks, the crowded conditions made contagion unavoidable. He worked in the factory, untested, until he started to experience shortness of breath. Not only was Mr Gonzalez not tested after learning about his co-workers’ infections, but he continued to go to work while asymptomatic because he was concerned about losing his job. Countless workers have been in a similar position. Amazon, the largest employer in the Inland Empire, recently revealed that nearly 20,000 frontline Amazon and Whole Foods Market employees tested positive or were presumed positive for the virus between March and September (Redman, Citation2020). They were all confronted with this persistent dilemma – preserve their livelihoods or prevent possible infection.

Through a gradual process of union-busting and overrepresentation in informal sector work, such as construction, domestic service and gardening, many Latinx workers in Los Angeles County lack the protections of organised labour (National Immigration Law Center, Citation2020). In addition to lower wages, this lack of representation leads to unsafe working conditions and denial of basic benefits, including sick pay. Non-union labourers, many undocumented in the U.S., cannot afford to quarantine at home and are ineligible for state-sponsored pandemic assistance (Hamilton et al., Citation2020).

The Trump administration sought to reinforce this pandemic-fueled precaritization through implementing a Department of Homeland Security ‘public charge’ rule allowing immigration officials to deny green cards to persons who might need public assistance, such as healthcare. Though Congress has passed laws exempting COVID-19 related programmes from Immigration and Customs Enforcement purview and the ‘public charge’ rule has been blocked by federal courts, immigrant rights groups raise concerns about the ‘chilling effect’ this ruling had on undocumented individuals afraid to access healthcare (Garcia, Citation2020). This was echoed in the COVID-19 Farmworker Study, which found that many farmworkers in California are reluctant to seek care despite concerns about infection out of fear of deportation or detainment (COVID 19 Farmworker Study Collective, Citation2020). The same historical legacies and political economic processes that have made Southern California a significant geographic site of incredible wealth accumulation for agriculture, warehousing, logistics, and other industries have also precipitated and magnified the vulnerabilities experienced by the region’s racialised communities.

Detroit metropolitan area: City and county

Around the same time that COVID-19 cases started to spike in Los Angeles, the virus also moved into the centre of Detroit. Detroit has an iconic place in the ideology of American racism, long revered and feared for its Black political leadership and pro-worker organising, and that ideological legacy continues to define the place itself, particularly in the wake of the city’s 2013 bankruptcy. By the summer of 2020, the nation’s largest majority-Black city, has also become the epicentre of the largest racial disparity in COVID-19 deaths in the country (COVID Tracking Project 2020). Worse still, the pandemic’s arrival in the metropolitan area precipitated longstanding concerns about one of the region’s most divisive issues: water shutoffs. Since 2005, anti-poverty activists in the state have been sounding alarms over the rising costs of water and sewage treatment, leaving many unhoused or without running water. We know from citizen subpoenas of public records that more than ten thousand Detroit households were without water at the start of the pandemic (housing 2–3 people each, on average).

The city’s geographic segregation, and its racialised debt arrangements were kindling for a crisis. Suburban sprawl has siphoned away good jobs, good housing, and the taxes they generate, leading to the city’s infamous dissolution of public goods and services (Sugrue, Citation2014). Historically, Detroit has been union-strong, but in recent decades the city has seen employment erode, with jobs mechanised or moved offshore, while much future demand for labour has been stifled by the lack of investments in infrastructure (Holzer & Rivera, Citation2019). Moreover, historical capital arrangements have left cities saddled with the debt for systems that serve communities across the state. The largest share of that debt arises from the Detroit Water and Sewerage System, an essential infrastructure that has become the subject of intense political conflict in the last decade. With the near-total withdrawal of state and federal funding for water infrastructures, that debt now falls on Detroit, the poorest city in the country.

Following the 2008 financial crisis, the City of Detroit experimented with measures of extreme austerity, including restrictions on garbage collection, street lights, and even water and sewer service (Bhaksharan, Citation2018). At the same time, the city raised prices on all of these services, far exceeding limits set by the international human rights standards. To fill budget holes left from the withdrawal of state and federal infrastructure funds, the city keeps trying to squeeze more from residents. The racial concentration of poverty and precarity is stark, and the effects on daily life are extreme. There are still world-class private hospitals in the city, but the majority who live nearby cannot access them – for lack of insurance, transportation or trust. Detroit residents suffer from a lack of basic infrastructure.

For a family without running water, daily life involves any number of logistical feats to sustain a clean home and healthy family. In 2016, one of our authors interviewed a family of four that lived in a home without running water for most of a year. Laundry was a major challenge. One parent hired a car to drive to the nearest coin operated laundromat – more than two miles away. They spent four hours waiting on the wash to finish before making the return journey home. For laundry alone, they paid nearly $200 a month (Gaber, Citation2019). In America, it is expensive to be poor (Ehrenreich, Citation2001). Those without water spend another $50 a month on bottled water, which they learn to recycle for cooking, bathing, cleaning and flushing, in that order. When word of COVID-19 arrived in Detroit, packs of water were sold out across the city. Churches, food banks, and citizen-led groups that provide water to those in need were no longer given donations from corporate suppliers, and were even unable to purchase water in bulk. Both public and private supplies dried up, as people stockpiled water out of fear of the unknown (People’s Water Board Coalition, Citation2020).

The imminent threat made clear what activists had been saying for years, and what scientists have known since cholera was characterised as a bacterium spread through shared water systems: that lack of access to safe water is a public health hazard. This was only made more visible by the first and most fundamental recommendation to stop the spread of coronavirus: ‘Wash your hands with soap and water for 20 s.’ This simple act has been functionally denied in Detroit, even as the city scrambles to ‘find’ and temporarily restore services to those shut off (Kurth, Citation2020).

As the pandemic demands that people ‘shelter in place’, water shutoffs reinforce the violence of racialised geographies, where basic utilities have been gentrified under new financial schemes. Detroit preacher, scholar and activist Reverend Roslyn Bouier (Citation2020) makes clear that the racialised segregation of housing and the robbery of basic goods from entire neighbourhoods has taken away the ability to safely shelter:

[W]hen your water is shut off and we are given the directive to shelter in — … we’re not using that word correctly. ‘Shelter’ is defined as having a place of safety and comfort and protection. And when you don’t have water on, that’s not shelter. It’s not shelter when children have to take their waste outside and throw it in the garbage. It’s not shelter when you don’t have water in your home and the sanitation is not available, because the city had declared that laundromats were nonessential providers, so laundromats were closed up, as well.

Without doubt, this version of capitalism depends upon, and deepens, historical racisms in post-industrial cities. It proceeds along the template of spatial segregation laid out on ‘redlining’ maps that delineated housing market risk according to racial demographics. Though the laws have technically changed, the divisions are set in space – the majority of Metro Detroit’s suburbs are over 95% white, while Detroit is nearly 80% Black. Over the past four decades, conservatives have ‘ghettoised’ whole cities, while extracting use and profit from their infrastructures.

Smartly, the Governor of Michigan instituted a moratorium on shutoffs and emergency restoration of water services in the face of COVID-19. Residents claimed the city did fewer restorations per week than disconnections, while the water department claimed it had no records of where to find those without service (Einhorn, Citation2020). Advocates demand that the moratorium on water shutoffs be made permanent (Jean, Citation2020). If it is allowed to expire with the expiration of the COVID-19 state of emergency, it will only recreate the conditions of poverty and precarity that breed disease, that fuel distrust, and that auction human dignity on the market of austerity.

Given the extremely exploitative economics of these most basic of services and their racial distribution, it will come as no surprise that Michigan has seen some of the most dramatic racial disparities in COVID-19 outcomes in the country. Water scarcity has been added to a long list of global disparities in resources needed to quarantine or isolate (OECD, Citation2020). Early in the pandemic, the World Health Organization recognised the threat that water insecurity poses to curtailing COVID-19, stating clearly: ‘[w]ater services should not be cut off because of consumers’ inability to pay’ (WHO & UNICEF, Citation2020). In the case of Detroit, the water situation erodes perceived notions about the U.S. as a high-income, or ‘developed’ context, bringing traditionally ‘global’ health concerns to the heart of an iconic American city.

Understanding the city’s history of political violence, racial dispossession, and anti-union austerity is essential to analysing the extreme racial disparity in COVID-19 infections and deaths in Detroit. Though the disparity has often been attributed to biological differences in susceptibility to the virus, or cultural differences in social distancing and safe handwashing practices, the inability of residents to access even water points to a deeper political cause of the coronavirus’ spread. To the extent that pre-existing conditions may exacerbate the course of an infection, and Black Americans are disproportionately burdened by lung disease, heart conditions, and diabetes, the political geography of racism is the pre-existing and ongoing condition to which scholars and policymakers must attend in order to interrupt the devastation being wrought by this politically-discriminating virus.

The political geographies of racialisation in U.S. cities

As the cases demonstrate, Black and Latinx urban residents are suffering some of the worst consequences of the crisis in the U.S. due to decades of discriminatory political and economic processes. These historical processes of disenfranchisement are embedded in municipal geographies and economic opportunities, where they have overdetermined the direction of viral spread, contributing to higher levels of viral exposure, and stifled an effective public health response. While public health agencies have offered recommendations for how people can protect themselves from viral spread through a set of individual practices, such recommendations are not tenable amid the systematic violences of racialised geographies. Learning from these three U.S. cities, we diagnose how the political geography of racialisation calibrated the conditions for this crisis. Corrosive political processes of racial exclusion have also undermined the very possibility of an effective public health response.

We have witnessed how racial segregation and geographic divestment have led to undertesting and undertreatment in racialised neighbourhoods in cities like San Francisco. We have analysed racialised labour exploitation and its concomitant risk factors in cities like Los Angeles. And we have observed how the defunding of basic utilities has systematically undercut the ability to shelter in place for whole communities in cities like Detroit. The fact that populations of colour are experiencing disproportionately high levels of COVID-19 can be traced to these multifaceted threads of social inequality shaped by historical and contemporary expressions of structural racism and geographic exclusion affecting these groups.

In San Francisco, the public health department responded to significant disparities of COVID-19 cases among Black and Latinx residents by creating ‘pop-up’ testing opportunities, without any structural interventions to prevent future infections, and rolled out study protocols to ‘include’ communities most impacted by the virus, but did not design interventions to meet their larger needs. This form of ‘inclusion’ is endemic in biomedicine – it thinly disguises imbalances of power under the heading of ‘access’ (Epstein, Citation2009; Petryna, Citation2009), and thus merely conceals the drivers of social inequality that it cannot heal.

Communities recognise this thin layer of care and resist participating in individual research studies and going to far-off COVID-19 testing sites because the limited timelines of experiments and bounded geographies of pop-up clinics are symptomatic of and a poor solution to deep processes of exclusion. After decades of exclusion from daily life in the city, inclusion in research studies is a weak – and sometimes offensive – bandage. While bioethical principles for racial inclusion should be maintained, these inclusive gestures are weak reactions. They do not address the structural drivers of disease, nor redress systemic issues of exclusion. Institutional and interpersonal racism, which remains pervasive in medicine, from health systems policy to clinical practice, impacts who is tested, who has access to quality health insurance, and how they are treated. Lower rates of health insurance on top of unconscious bias leads to systematic undertreatment, less communication with patients and restricted treatment options, resulting in significant differences in race-stratified mortality rates (Fiscella & Sanders, Citation2016). Testing centres and experimental studies have become sites of contestation – while they may be necessary, they are not a sufficient for ensuring health equity at scale.

In Los Angeles, prevention and testing options were grossly inadequate to keep workers safe. While outreach programmes attempted to quell fears and financial setbacks from quarantine, incentives alone could not keep pace with the toll of the epidemic. Without adequate protections for their jobs or from the virus, workers were forced to return to factories where they were exposed to the virus. Without basic labour protections, workers could not do their jobs safely – they could not even take time off to get tested. Since racial capitalism has entrenched socioeconomic inequalities, Black and Brown people have become more likely to work high-exposure jobs and acquire COVID-19. They have also been less likely to be homeowners, and so more likely to be in multi-generational households where the virus could pass to elders (Desmond, Citation2017). Due to these injustices, people of colour across the spectrum of race and ethnicity have been much harder hit by COVID-19 than have whites in the U.S. Shaped by historical acts of dispossession and capitalist imperatives that expose groups of people to uneven harms, the political geography of racialisation has guided the path of the virus into specific segments of the population, creating further divisions in society.

In Detroit, the same extreme divisions in society that limit access to water limited access to the fair provision of testing for COVID-19. Here, universal testing was deemed necessary yet still proved grossly insufficient because those at highest risk were least able to access tests. While Detroit was one of the first major cities to provide free testing to all, regardless of symptoms or status as ‘essential workers’ (Carmody, Citation2020), these services were functionally inaccessible to much of the city. Histories of geographic divestment and privatisation have segregated cities, limiting access to the most basic utilities. Without basic needs being met, families cannot safely shelter in place or practice the basic preventative act of handwashing to prevent the virus’ spread. Long term structural inequities have undercut economic opportunities, and created racialised vulnerabilities.

Conclusion

The effects of the viral outbreak and responses to it have been insidiously shaped by legacies of racial marginalisation embedded in economic opportunities. Over decades, these harms have been worked into the geography of cities, the dynamics of labour markets, and the environments where people live. The ongoing legacies of racialised marginalisation and geographic disinvestment have multiplied the deadliness of disease and deepened divisions in society. As COVID-19 ripples through populations, it follows these clear rifts in our societies. Unfortunately, this set of corrosive political processes are not unique to the U.S. The U.S. is but one of several ‘liberal democracies’ that has been divided by capitalism and ripped apart by racism, alongside Brazil, France, Germany, India, and the UK – to name only a few. Through our analysis of the COVID-19 crisis in three specific cities, our goal is to move toward comprehending and confronting the nexus of this pandemic and its socio-political acceleration globally (Whitacre et al., Citation2020).

We must continue to examine, document, and confront the ongoing COVID-19 crisis as enacted through the politics of race and space. By redressing structural violence – through socio-political structural change including universal healthcare, workplace protections, equitable homeownership and rental and utility safeguards – we can make the public health response more effective. By understanding and addressing the social determination of health in the pandemic will we be able to realise a more adequate response to the pandemic and the inequities it has laid bare in the U.S. and globally. And only through confronting and ameliorating the social, political and economic structures producing health disparities will we be able to make our global social and public health systems more prepared for future pandemics occurring at the intersection of biological and social pathogens.

To mount an effective response and recover from this global crisis, we need to bridge what divides us and repair what endangers us. We need to broaden the horizon of health equity, expand safety, security and benefits for all – especially those deemed essential with an hourly wage or with limited contracts and limited protections (Neff et al., Citation2020; Holmes, Citation2020). We need to grow investments in housing for communities made vulnerable by discriminatory policies. We need to address the socio-political fissures and redress structural inequities, or we will deepen the inequities that divide us, and kill many of us prematurely.

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant #189186) and a fellowship from the Mediterranean Institute for Advanced Study and the Institut Paoli Calmette. The discussion benefited from a close reading by Emilien Schultz, PhD, Institut Paoli Calmette, Marseille, France. The authors would like to express their deep gratitude to Sam Dubal, MD, PhD, Department of Anthropology, University of Washington, for his constant enthusiasm and intellectual ferocity, which keeps all of our spirits afloat.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 San Francisco’s Black population decreased from 13.4% in 1970 to 5.6 according to the most recent U.S. Census Bureau estimates with the majority living in District 10 (2018).

2 LA County COVID-19 Dashboard, http://dashboard.publichealth.lacounty.gov/covid19_surveillance_dashboard/. Accessed January 22, 2021.

3 California Department of Public Health, https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/Pages/COVID-19/Race-Ethnicity.aspx. Accessed January 22, 2021.

References

- Allison, J. E., Herrera, J. S., Struna, J., & Reese, E. (2018). The matrix of exploitation and temporary employment: Earnings inequality among Inland Southern California’s blue-collar warehouse workers. Journal of Labor and Society, 21(4), 533–560. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/wusa.12366

- Bayview Hunters Point Mothers Environmental Health & Justice Committee, Huntersview Tenants Association. (2004). Pollution, health, environmental racism and injustice: A toxic inventory of Bayview Hunters Point, San Francisco. Greenaction for Health & Environmental Justice. https://greenaction.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/thestateoftheenvironment090204final.pdf

- Bhaksharan, S. (2018). Public health & wealth in post-bankrupcy detroit. Othering & Belonging Institute. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6fp4q9s8

- Blauner, R. (1972). Racial oppression in America. Harper & Row.

- Bonacich, E., & Wilson, J. (2008). Getting the goods: Ports, labor, and the logisticsrevolution. Cornell University Press: Cornell University Press.

- Bouier, R. (2020, April 13). Wash Your Hands? Despite Pandemic, Thousands Still Have No Water in Detroit, a Coronavirus Hot Spot. Democracy Now! https://www.democracynow.org/2020/4/13/detroit_michigan_water_shut_offs

- Brahinsky, R. (2014). Race and the making of Southeast San Francisco: Towards a theory of race-class. Antipode, 46(5), 1258–1276. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12050

- Broussard, A. S. (1993). Black San Francisco: The struggle for racial equality in the West, 1900-1954. University Press of Kansas.

- CA.gov. (2020). COVID-19 Cases Dashboard. COVID-19 Cases. Retrieved January 15, 2021, from https://public.tableau.com/views/COVID-19CasesDashboard_15931020425010/Cases?:embed=y&:showVizHome=no

- Carmody, S. (2020, May 18). Detroit expands COVID-19 testing to all city residents, eyes reopening city businesses. Michigan Radio. https://www.michiganradio.org/post/detroit-expands-covid-19-testing-all-city-residents-eyes-reopening-city-businesses

- CDC. (2020, February 11). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html

- COVID-19 Farmworker Study Collective. (2020). Preliminary data. http://covid19farmworkerstudy.org/preliminary-data/

- Danaei, G., Rimm, E. B., Oza, S., Kulkarni, S. C., Murray, C. J. L., & Ezzati, M. (2010). The promise of prevention: The effects of four preventable risk factors on national life expectancy and life expectancy disparities by race and county in the United States. PLoS Medicine, 7(3), e1000248. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000248

- Davis, Angela Y., & West, C. (2016). Freedom is a constant struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the foundations of a movement. 4th printing edition. Frank Barat (ed.). Haymarket Books.

- De Lara, J. D. (2018). Inland shift: Race, space, and capital in southern California. In Inland shift. University of California Press. https://california.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1525/california/9780520289581.001.0001/upso-9780520289581

- De Lara, J. D. D., Reese, E. R., & Struna, J. (2016). Organizing temporary, subcontracted, and immigrant workers: Lessons from change to win’s warehouse workers united campaign. Labor Studies Journal, 41(4), 309–332. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0160449X16664415

- Desmond, M. (2017). Housing. Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality, Pathways Magazine. State of the Union. Special Issue, 16–19. https://inequality.stanford.edu/publications/pathway/state-union-2017

- Du Bois, W. E. B. (2007). Black reconstruction in America: An essay toward a history of the part which Black folk played in the attempt to reconstruct democracy in America, 1860-1880. Oxford University Press.

- Dwyer-Lindgren, L., Bertozzi-Villa, A., Stubbs, R. W., Morozoff, C., Mackenbach, J. P., van Lenthe, F. J., Mokdad, A. H., & Murray, C. J. L. (2017). Inequalities in life expectancy among U.S. counties, 1980 to 2014: Temporal trends and Key drivers. JAMA Internal Medicine, 177(7), 1003. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0918

- Ehrenreich, B. (2001). Nickel and dimed. New York Metropolitan.

- Einhorn, E. (2020, March 26). ‘It’s just despair’: Many Americans face coronavirus with no water to wash their hands. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/it-s-just-despair-many-americans-face-coronavirus-no-water-n1169351

- Epstein, S. (2009). Inclusion: The politics of difference in medical research (Illustrated edition). University of Chicago Press.

- Feagin, J. R. (2006). Systemic racism: A theory of oppression (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Fiscella, K., & Sanders, M. R. (2016). Racial and ethnic disparities in the quality of health care. Annual Review of Public Health, 37(1), 375–394. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032315-021439

- Fracassa, D. (2020, February 26). SF Mayor London Breed declares state of emergency over coronavirus. SFChronicle.com. https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/SF-mayor-London-Breed-declares-state-of-emergency-15083811.php

- Friedhoff, A., Wial, H., and Wolman H. (2020, November 30). The consequences of metropolitan manufacturing decline: Testing conventional wisdom. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-consequences-of-metropolitan-manufacturing-decline-testing-conventional-wisdom/

- Gaber, N. A. O. (2019). Life after water: Detroit, flint and the postindustrial politics of health. University of California. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1wr9g3s8

- Garcia, J. (2020, June 4). No jobs, no tests, no savings: Southeast LA County hit hard by pandemic. CalMatters. https://calmatters.org/economy/2020/06/southeast-los-angeles-county-pandemic/

- Gereffi, G., & Christian, M. (2009). The impacts of Wal-Mart: The rise and consequences of the world’s dominant retailer. Annual Review of Sociology, 35(1), 573–591. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115947

- Gutelius, B., & Theodore, N. (2019). The future of warehouse work: Technological change in the U.S. Logistics Industry. http://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/future-of-warehouse-work

- Hamilton, N., & Chinchilla, N. S. (2001). Seeking community in global city: Guatemalans & Salvadorans in Los Angeles (1st ed.). Temple University Press.

- Hamilton, D., Fienup, M., Hayes-Bautista, D., & Hsu, P. (2020). LDC U.S. Latino GDP Report (Quantifying the New American Economy). California Lutheran University; UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine.

- Hayes-Bautista, D. E., Hsu, P., & Hernandez, G. D. (2020). COVID-19, Latino Working-Age Adults, and Citizenship. UCLA Health, Center for the Study of Latino Health and Culture. https://www.uclahealth.org/ceslac/workfiles/Research/COVID-19/Report-9-COVID-19-Latino-Working-Age-Adults-and-Citizenship.pdf

- Hernández, K. (2017). City of inmates: Conquest, rebellion, and the rise of human caging in Los Angeles, 1771–1965. University of North Carolina Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9781469631196_hernandez

- Holmes, S. (2020, April 30). As societies re-open in this pandemic, we need social solidarity to survive the summer. The BMJ. https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/04/30/seth-holmes-societies-re-open-pandemic-need-social-solidarity-survive/

- Holzer, H. J., & Rivera, J. (2019). The detroit labor market: Recent trends, current realities. Poverty Solutions Research Publications, 1–26.

- Hondagneu-Sotelo, P. (2014). Paradise transplanted: Migration and the Making of California gardens (1st ed.). https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520277779/paradise-transplanted

- Horne, G. (2017). The apocalypse of settler colonialism: The roots of slavery, white supremacy, and capitalism in 17th century North America and the Caribbean. NYU Press.

- Jean, V. (2020, August 3). Demand a moratorium on shutoffs! People’s Water Board. https://www.peopleswaterboard.org/2020/08/03/demand-a-moratorium-on-shutoffs/

- Kim, J. (2008). Immigrants, racial citizens, and the (multi)cultural politics of neoliberal Los Angeles. Social Justice, 35(2 (112)), 36–56. www.jstor.org/stable/29768487

- Kurth, J. (2020, February 26). Detroit says no proof water shutoffs harm health. Get real, experts say. Bridge Highigan, Michigan Health Watch. https://www.bridgemi.com/michigan-health-watch/detroit-says-no-proof-water-shutoffs-harm-health-get-real-experts-say

- LA County Department of Public Health. COVID-19 Locations & Demographics. Retrieved October 11, 2020, from http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/media/Coronavirus/locations.htm#snf-deaths

- Lassetter, J. H., & Callister, L. C. (2009). The impact of migration on the health of voluntary migrants in western societies: A review of the literature. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 20(1), 93–104. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659608325841

- Lee, E. (2002). The Chinese exclusion example: Race, immigration, and American gatekeeping, 1882-1924. Journal of American Ethnic History, 21(3), 36–62. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27502847

- Lin, R. & Money, L. (2021, January 22). California sees record-breaking COVID-19 deaths, a lagging indicator of winter surge. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2021-01-22/california-sees-record-breaking-covid-19-deaths-a-lagging-indicator-of-winter-surge

- Melamed, J. (2015). Racial capitalism. Critical Ethnic Studies, 1(1), 76–85. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5749/jcritethnstud.1.1.0076

- Miyares, I., Wright, R., Mountz, A., & Bailey, A. (2019). Truncated transnationalism, the tenuousness of temporary protected status, and Trump. Journal of Latin American Geography. https://repository.hkbu.edu.hk/hkbu_staff_publication/6855

- Moore, E., Montojo, N., & Mauri, N. (2019). Roots, race, & place: A history of racially exclusionary housing in the San Francisco Bay Area. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2j08r197

- National Immigration Law Center. (2020). Understanding the impact of key provisions of COVID-19 relief bills on immigrant communities. https://www.nilc.org/issues/economic-support/impact-of-covid19-relief-bills-on-immigrant-communities/

- Neff, J., Holmes, S. M., Knight, K. R., Strong, S., Thompson-Lastad, A., McGuinness, C., Duncan, L., Saxena, N., Harvey, M. J., Langford, A., Carey-Simms, K. L., Minahan, S. N., Satterwhite, S., Ruppel, C., Lee, S., Walkover, L., De Avila, J., Lewis, B., Matthews, J., & Nelson, N. (2020). Structural competency: Curriculum for medical students, residents, and interprofessional teams on the structural factors that produce health disparities. MedEdPORTAL : The Journal of Teaching and Learning Resources, 16(1). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10888

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2020). COVID-19: Protecting people and societies (OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19)). https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/covid-19-protecting-people-and-societies-e5c9de1a/

- People’s Water Board Coalition. (2020). Appeal to Governor Gretchen Whitmer. https://www.peopleswaterboard.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/PWB_AppealToWhitmer.pdf

- Petryna, A. (2009). When experiments travel: Clinical trials and the global search for human subjects (1st ed.). Princeton University Press.

- Redman, R. (2020, October 3). Amazon reports nearly 20,000 COVID-infected frontline workers since March. Supermarket News. https://www.supermarketnews.com/issues-trends/amazon-reports-nearly-20000-covid-infected-frontline-workers-march

- Robinson, W. I. (2008). Latin America and global capitalism: A critical globalization perspective. JHU Press.

- Robinson, C. J., & Kelley, R. D. G. (2000). Black marxism: The making of the black radical tradition (2nd ed.). University of North Carolina Press.

- Romo, R. (1983). East Los Angeles history of a barrio. University of Texas Press. https://utpress.utexas.edu/books/romela

- Rubin-Miller, L., Alban, C., Artiga, S., & Sullivan, S. (2020, September 16). COVID-19 racial disparities in testing, infection, hospitalization, and death: Analysis of epic patient data - Issue brief. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/report-section/covid-19-racial-disparities-in-testing-infection-hospitalization-and-death-analysis-of-epic-patient-data-issue-brief/

- Shange, S. (2019). Black girl ordinary: Flesh, carcerality, and the refusal of ethnography. Transforming Anthropology, 27(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/traa.12143

- Singh, N. P. (2005). Black is a country: Race and the unfinished struggle for democracy. Harvard University Press.

- Sugrue, T. (2014). The origins of the urban crisis. Princeton University Press. https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691162553/the-origins-of-the-urban-crisis

- Tyner, J. (2019). Dead labor: Toward a political economy of premature death. Minnesota Press. https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/dead-labor

- Wacquant, L. (2000). The new “peculiar institution”: On the prison as surrogate ghetto. Theoretical Criminology, 4(3), 377–389. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480600004003007

- We the People of Detroit. (2018). Community research collective. https://www.wethepeopleofdetroit.com/community-research

- Whitacre, R. P., Buchbinder, L. S., & Holmes, S. M. (2020). The pandemic present. Social Anthropology, Forum on COVID-19 Pandemic. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-8676.12829

- World Health Organization [WHO] and United Nations Children’s Fund [UNICEF]. (2020). Water, sanitation, hygiene, and waste management for the COVID-19 virus. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331846/WHO-2019-nCoV-IPC_WASH-2020.3-eng.pdf

- The White House. (2020). Proclamation on declaring a national emergency concerning the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/proclamation-declaring-national-emergency-concerning-novel-coronavirus-disease-covid-19-outbreak/