ABSTRACT

It is easy but mistaken to think that public health emergency measures and social policy can be separated. This paper compares the experiences of Brazil, Germany, India and the United States during their 2020 responses to the COVID-19 pandemic to show that social policies such as unemployment insurance, flat payments and short-time work are crucial to the effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical interventions as well as to their political sustainability. Broadly, public health measures that constrain economic activity will only be effective and sustainable if paired with social policy measures that enable people to comply without sacrificing their livelihoods and economic wellbeing. Tough public health policies and generous social policies taken together proved a success in Germany. Generous social policies uncoupled from strong public health interventions, in Brazil and the US during the summer of 2020, enabled lockdown compliance but failed to halt the pandemic, while tough public health measures without social policy support rapidly collapsed in India. In the COVID-19 and future pandemics, public health theory and practice should recognise the importance of social policy to the immediate effectiveness of public health policy as well as to the long-term social and economic impact of pandemics.

Introduction

In assessments of responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a strong focus on comparing the strictness of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) such as business closures, travel restrictions, or masking, across countries and on the operation of testing, tracing, and isolation systems (Markel et al., Citation2007). Each of these public health policies, crucial to controlling any outbreak in the absence of widespread vaccination, imposes costs on individuals and businesses. Those costs can undermine individual willingness to comply as well as political support for public health measures. We ask if social policies are necessary to support the adoption and sustainability of public health policies. Our hypothesis is that the ‘pre-existing social policies of the country as well as the ones enacted specifically to respond to the COVID-19 challenge will shape the extent of compliance with public health measures’ (Greer et al., Citation2020).

To understand the relationship between social policies and public health we employ a conceptual framework drawn from prior empirical analysis of state responses (Greer et al., Citation2021) and informed by prior work in the fields of global health policy and political science (Jarman, Citation2021). Governments taking coercive actions use their authority to restrict the behaviour of individuals, organisations and businesses.

Social policy refers to policies that are ‘beneficent, redistributive, and concerned with economic as well as non-economic goals’ which effectively means the welfare state including health care, pension, family, educational, and similar policies (Titmuss, Citation2001). We separate out healthcare in this analysis, using social policy to refer to all the other areas of policy which enable compliance with public health measures. In the case of COVID-19, especially relevant social policies include automatic stabilisers such as unemployment insurance as well as specific actions including eviction moratoria, universal cash transfers, distribution of free food, support for small businesses, worker protections and short-time work in which the government finances payroll for firms so that they do not need to lay off employees for whom there is no work due to the crisis (kurzarbeit). The thesis that social policy is required to support pandemic response is encapsulated in phrases such as ‘test, trace, isolate’ or ‘test, trace, isolate, support’ (Rajan et al., Citation2020) or the idea that ‘compliance requires not just things like good communication and trust, but also a political economy that permits people to stay at home without starving’ (Greer et al., Citation2020).

We can distinguish a ‘social policy baseline’ predating the pandemic from specific actions taken in response to the pandemic and to support public health policies. Thus, unemployment insurance for formal workers is an automatic stabiliser, but additional top-up payments for it could be an additional crisis response policy. Many countries enacted additional social policies during the pandemic, generally temporary ones, but the need for such policies could logically be lesser if they already had well-funded and effective social policies in place.

Materials and methods

We analyse the experiences of four countries in the global first wave of COVID-19 from the arrival of the disease until November 2020: Brazil, Germany, India and the United States. There are not enough countries in the world to conduct frequentist statistical analyses, which is why we exploit the richness of case studies to understand the reciprocal interactions of policies, societies, and the virus (Jarman & Greer, Citation2020). We selected these countries to represent different policy responses to the pandemic among countries with different background fiscal and economic situations but enough decision space to enact social policies. Our case selection approach is what Skocpol and Somers’ classic comparison called the ‘Parallel Demonstration of Theory’ and the ‘Macro-Causal Analysis’ approaches, in which a broad theoretical hypothesis (in our case, that emergency response rests on successful social policy) is tested in a range of cases, but combined with experiences learned on the ground (Skocpol & Somers, Citation1994; also Mätzke, Citation2009). It is part of the intellectual lineage of John Stuart Mill's method of difference, in which finding similar outcomes (or mechanisms) in otherwise different cases allows us to infer the cause from whatever they do share (Ragin, Citation1987). The purpose of the case selections is thus to test the idea in diverse cases. We selected four large and complex countries, with an aim towards geographical diversity, that were all experiencing the COVID-19 pandemic in spring 2020. Two of the countries are middle-income and two are higher-income ones, reflecting our interest in states with the capacity to enact significant social policy measures. They are also geographically diverse and all saw significant COVID-19 in the first wave. In the discussion section, we address some of the limitations this entails.

Conceptually, strong social policy responses invest significant resources in managing shocks such as those associated with the pandemic. This could mean, for example, increasing the investment in existing labour policies or creating new programmes to support the unemployed. Strong public health policy responses involve early major NPIs as well as construction of an effective TTIS system. These initiatives should be as strong as, or stronger, than WHO guidelines and coordinated at the highest level (given that our cases are large federations).

Our operationalisation of strength and weakness is qualitative. As with any social policy, use of aggregate numbers to represent social policy priorities and effectiveness is difficult. In many cases, cross-nationally comparable data do not exist, and even when they do, details of targeting and priorities (e.g. who exactly received income support) are rarely available with the specificity and comparability we would want. presents the size of both specific COVID-19 related expenditure and some statistics that imply the baseline of public social policy expenditure for our four cases. The best data on social policy baselines, from the OECD SOCX dataset, is only available for two of our cases (Germany and the US). Government expenditure as a percentage of GDP is obviously problematic since it includes non-social-policy expenditures of all sorts, but we report it to give a sense of the general size of government, and we report health (almost entirely healthcare) expenditure according to the World Bank to give a sense of the size of social expenditures in the absence of cross-nationally comparable social policy data outside the OECD states.

Table 1. Basic indicators of social policy baseline and response.

As evident from the compromises required to produce and read , it is difficult to compare quantitative data. Thus, our judgements on the social policy baselines and responses are informed by country-specific policy literature, including media and grey literature, and emphasise the intended targets and programme design rather than raw sums of money, given that even big and well-measured sums can be directed in ways that are only indirectly related to social policy (e.g. support to businesses).

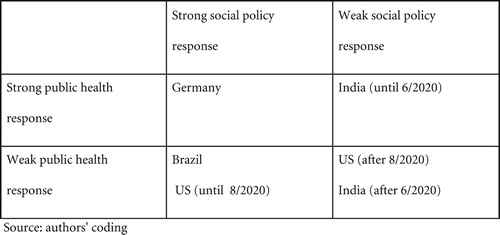

maps out our cases. The United States and India had erratic trajectories in 2020 such that we can effectively count them as two different cases. The United States enacted a strikingly large social policy response and then let it expire in autumn 2020 without having developed an effective public health response. India enacted a large-scale national public health response and then let it lapse, with many of its federal states failing to manage public health responses. We, therefore, place both countries in two different cells.

Results

In each of our four cases, the interaction and articulation of public health and social policies were crucial to the success of emergency public health measures and management of the pandemic in its first six months, from March to the end of September 2020.

The United States

The United States in 2020 combined a public health debacle with a social policy roller-coaster, in which it started with an inegalitarian social policy and society, briefly adopted a nearly European welfare state, failed to build an effective public health response, and then let its social policy response lapse. A series of stopgap spending measures maintained some emergency social policies to the end of 2020 before large-scale legislation in 2021. The federal government, unlike state and local governments, had the borrowing capacity to lead both public health and social policy responses. While its public health response has been abundantly critiqued, its social policy response in March was on a scale comparable to the most responsive European welfare states and innovative in its use of policy tools. The result was a likely reduction in poverty. This was not matched by stringent nationwide NPIs or the construction of a useful test-trace-isolate-support programme. The extraordinary social policies expired in late summer, leaving the United States in a difficult position by autumn. One might have initially feared that the United States would have adopted a strong public health response without corresponding social policies to buffer the effects of coercive actions; instead, the United States adopted the social policies without the public health policies, let the social policies expire, and entered the winter of 2020–2021 with weak public health and ad hoc social policies.

The United States federal system lodges the ‘police powers’ to impose NPIs primarily at the state level, and it was at the state level that most NPIs took place. State and local governments are economically competitive and bound by balanced and other budget rules which tend to make their fiscal policy impact procyclical. Their situation gave them considerable incentives not to invest in extensive public health infrastructures or enact or maintain NPIs. In some, such as Michigan and Wisconsin, partisan state courts deprived governors of their coercive powers in mid-pandemic. The federal government had both more substantial legal and public health resources to create a TTIS system – and vastly larger ability to finance social policy measures (Greer, Citation2020; Singer et al., Citation2021). Under Trump, it did not use these public health resources, let alone explore its legal authority for effective national NPIs.

Social policy baseline

United States social policy is fragmented and ungenerous by the standards of most rich welfare states, with a bias towards education spending rather than social support, and its spending is distorted by a fragmented, non-universal, and expensive health care system that connects health insurance to employment. The only near-universal benefits are for people over 65, who can receive health care and a limited pension; other benefits are generally means-tested, vary by state, delivered in complex ways, and ungenerous (Elliott et al., Citation2019). Weak and fragmented social policy is one reason why the United States has a high level of racial, income and wealth inequality as well as poverty. For example, 17.5% of its children lived in poverty in 2017 (Children's Defense Fund, Citation2020), and 10.5% of households experienced food insecurity at some point in 2019 (USDA, Citation2020) – both years when unemployment was strikingly low. Inequality and poverty might help to explain why the United States, unusually for a rich country, had seen several years of declining life expectancy even before the pandemic (Woolf & Schoomaker, Citation2019).

Social policy in pandemic response

Initially, state governments adopted highly variable NPI measures (Adolph et al., Citation2021). The federal government, meanwhile, dominated social policy since states lacked the fiscal resources to adopt major social policy responses. The federal government responded with enormous aid to individuals as well as firms, most notably authorised in legislation called the CARES Act (Parrott et al., Citation2020). In total, the federal government authorised over two trillion dollars ($2,000,000,000,000) additional expenditure on pandemic response in March and April alone, about 10% of GDP (Anderson et al., Citation2020) (by the end of the year, it was around 13.2%; ). Salient components included aid to individuals (a flat $1200 per adult and $500 per child), a large increase in normal unemployment insurance benefits coupled to expanded eligibility, aid to companies, and a remarkable adoption of a variant short-work scheme in which firms could receive loans that amounted to grants if they were used to pay staff who were not working, called the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). In other words, the United States, for a few months, had something like a northern European welfare state, with flat payments to citizens, enhanced unemployment insurance, and a widespread short-work scheme as well as an eviction moratorium. The novelty of this period in the context of American social policy history is not always appreciated.

Data on the impact of federal action must be treated with some care because pandemic-related disruption might have interfered with sampling, but it nonetheless appears that the United States simultaneously experienced the largest increase in unemployment in its recorded history (a 14% increase in April 2020 alone) and a remarkable 21% reduction in its poverty rate (Han et al., Citation2020). While household savings rates increased, state and local governments were often surprised to find smaller budgetary gaps than they had initially planned, in part because overall economic activity did not drop as much as they expected and in part because CARES Act funding for pandemic response took pressure off of other budget lines.

While NPIs in the United States were highly variable in length, content, and seriousness, the CARES Act did permit a massive reduction in economic activity and mobility with limited damage to household wellbeing. Households, enabled by these social policies, vastly reduced their mobility, with the populations of many states voluntarily reducing interactions even when their governments chose only weak NPIs. In late summer, however, the most important of these temporary packages expired amidst a high-stakes election campaign. Their expiration exacerbated pressure on NPIs (from people, businesses, and governments losing revenue) (Rocco et al., Citation2020).

Interaction of social policies and pandemic response

The expiry of most CARES Act provisions over August and September 2020 reflected the initial assumption by policymakers that the federal government would effectively manage the COVID-19 pandemic and the country would resume normal economic life in autumn 2020. That assumption was sadly mistaken. The non-renewal of extraordinary social policy measures meant that the United States faced autumn 2020 and its economic disruption with little COVID-specific federal social policy and a pre-existing social policy baseline not equipped to respond to smaller problems than the pandemic. Given the continuing spread of the virus, it also meant that the economic damage would likely ramify, since even without stringent NPIs traffic in large areas of the economy was down as people eschewed businesses such as bars, restaurants, physical retail and travel.

The United States briefly created an extensive safety net in the summer of 2020. That might have enabled coercive measures sufficient to control the virus, but the federal government and most state governments failed to sustain it or match it with public health measures sufficient to restore anything like a normal economy by autumn 2020. By October, therefore, the United States was trapped in a highly partisan debate about the value of NPIs, the White House Chief of Staff told CNN that ‘we are not going to control the pandemic’ (Cole, Citation2020), public health infrastructures were largely overwhelmed, and the summer's limited economic progress was at risk.

India

India was initially noteworthy for its stringent public health response to the pandemic. Its federal government failed, however, to coordinate economic and social versus health priorities and lifted the country-wide lockdown, leaving states responsible for managing their pandemic response. Social policy action was primarily left to the central government while states initiated individual, small-scale social policies to manage population needs. Ultimately social policies failed to address individuals’ frustration about restrictions on working and fulfilling essential needs – food, housing, and money. By late autumn India faced uncontrolled spread as well as economic damage and serious social consequences of the NPIs and pandemic, particularly among the poor.

India’s federal system warrants its 28 states to have their own legislatures which can make laws regarding criminal justice, education, health taxation, public order, lands, and forests. Once a state of emergency has been declared, the central government has the authority to temporarily assume executive and financial control of a state.

Social policy baseline

India’s population is estimated at over 1.3 billion with people residing in different formal and informal housing environments, across rural and urban regions, and spanning a variety of topographies. India has made significant strides in reducing poverty; over 640 million people in the country were considered impoverished in 2005, and that number was roughly 365 million in 2017 (McCarthy, Citation2019). The unemployment rate in India was at roughly 6% prior to the pandemic and the government has launched several policies since the 1970s to reduce unemployment ranging from skills training for youth and programmes to foster entrepreneurship (Government of India, Citation2021). The 2005 National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme has been pivotal in guaranteeing wage employment to adults agreeing to do manual labour (e.g. building roads) (Kugler & Sinha, Citation2020).

Social policy in pandemic response

India’s central government announced a complete national lockdown on March 24 with unified implementation across the states, varying primarily in enforcement of the lockdown. However, once the national lockdown was lifted in May to enable movement of migrant workers from their place of work to their home and to revitalise the economy (Athrady, Citation2020; Maji et al., Citation2020) the effectiveness and coherence of the national effort eroded quickly. Individual states such as Odisha, Punjab, Maharashtra, Karnataka, West Bengal, and Telangana had individually extended their lockdowns (Economic Times, Citation2020a; Hindustan Times, Citation2020). Although the central government exerts financial control including allocation of funds to states, states have the authority to manage epidemics and disasters.

One of the major centralised social policy actions in India was Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s announcement of a Rs 20 lakh crore (307 billion USD) stimulus package in March 2020 following the national lockdown. Funding (roughly $24 billion USD) was intended to support all individuals with food and cooking gas. However, the direct cash transfers – intended to avoid delays – did not reach everyone because of complications with identification processes, inter-state travel, and challenges with identifying individuals residing in informal housing environments (Economic Times, Citation2020b). The stimulus package was successful at enabling people to survive in a temporarily frozen economy, but only among those the money actually reached.

States took on responsibility for social actions first in extending their individual lockdowns and then in their management of compound threats. For instance, Kerala, Karnataka and Odisha had implemented state-level lockdowns before the national lockdown. Others followed suit and extended their lockdowns after the national lockdown was lifted. However, enforcement varied across states and compound threats informed differences in prioritisation across the country. For example, West Bengal’s cyclone Amphan in mid-May sparked the rapid deployment of relief teams. Nevertheless, thousands were left homeless due to the cyclone and had to decide between staying endangered in what was left of their homes or relocating to cyclone shelters where infection could spread. After the national lockdown ended, states made decisions about lockdowns, which created confusion about which states had extended lockdown and which hadn’t, resulting in individual violations as well as the commencement of large gatherings.

Interaction of social policies and pandemic response

Even though many states and even the central government’s public health response was strong, we observe barriers to the effect of social policy actions on public health in India: the lack of standardised social policies across the country and barriers to social policy actions such as the stimulus package actually reaching everyone. Community groups – such as the Sikh community – in various states took it upon themselves to make food available to community members through the langar, or community kitchen. As marketplaces also began opening up to provide food and other necessities to communities, these places became crowded gathering areas.

Sustaining a lockdown was challenging without a means of enabling people to stay in their homes. Social distancing measures became secondary to the need for essential items. Individuals must acquire essential items, requiring that they go to often crowded areas to buy groceries and other items, and many must work. Health care organisations are undergoing salary cuts and doctors have left their positions, leaving communities – especially those at risk of needing high volume health care – in a vulnerable position without providers (Times of India, Citation2020).

Moreover, there was no way to assess in such a vast, populated country who actually received their stimulus money and who did not. As a result, the well-intentioned centralised social policy did not leave states with enough information to provide stimulus funds of their own outside of facilitating employment.

Brazil

Brazil’s story resembles that of the United States in the summer of 2020 in some ways, combining a strong social policy intervention with fragmented and politicised public health policies in which the federal government was otiose if not actively unhelpful. Its social policy actions were not as tightly connected to the pandemic, however, and remained in place after the US social policy response had collapsed.

In Brazil, the Ministry of Health (MoH) has the responsibility of coordinating health policies, particularly during public health crises. The state and local governments, through 438 regional healthcare areas, are in charge of administering Brazil’s public health system. Although coordination at the central level was seen in HIV/AIDS, Zika, H1N1 influenza, and other national health crises, COVID-19 was different. At the outset of the pandemic, the MoH acted promptly in alliance with several subnational governments. However, after the return of president Bolsonaro from a visit to the U.S. in mid-May, the promulgation of denialist, anti-science statements began, apparently in coordination with those of President Trump. In the absence of a strong, central public health response, state governments ended up taking responsibility for NPIs. The strong central social policy response, though, enabled what NPIs were adopted and limited economic damage.

Social policy baseline

COVID-19 struck Brazil during an economic crisis (Deweck et al., Citation2018). Responding to COVID-19 in Brazil demanded increased social expenditure against a backdrop of austerity policies, high unemployment rates, and social inequalities. Nearly half of Brazil's population lives in poverty (less than US$5.50 per day, PPP) or is vulnerable to falling into poverty; therefore, Brazil’s population is particularly susceptible to the negative socio-economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic (World Bank, Citation2020).

Social policies to protect the poor, informal workers, and the unemployed would be crucial in Brazil. Brazil has one of the world’s most successful conditional cash transfer programmes, known as the Family Allowance Program (Bolsa Familia) (Rasella et al., Citation2013). In 2020 Brazil provided one of the most generous social assistance packages in the Latin American region, despite its unhealthy fiscal condition.

Social policy in pandemic response

During the pandemic, the government promoted adjustments to the Family Allowance Program, and also created a new social programme to provide salary relief to vulnerable populations: the Emergency Allowance (Auxilio Emergencial), also known as ‘coronavoucher’. Notably, Brazil also created the Emergency Labor Program, designed to allow the reduction of labour hours for 90 days or temporary suspension of labour contracts for 60 days. During that time the government would either complement the salary or, in the case of contract suspension, cover the full unemployment insurance. Here we focus on the Family Allowance and the Emergency Allowance as these were the two most important social programmes implemented in Brazil during the pandemic, and are seen as exemplary counter-pandemic measures (World Bank, Citation2020).

The programme was announced mid-March 2020 after strong pressure on legislators from the Ministry of Economy. Initially, the executive government announced a R$200 allowance (US$37) per month which, after a debate in Congress, was increased to R$600 (US$110) (Piovesan & Siqueira, Citation2020). In May, the government came under further pressure to extend the allowance for additional months. Again, there was a dispute between the Minister of Economy and Congress. The former suggested an increase of the allowance by R$200 (US$38) per month for an additional two months. Ultimately, in September, a presidential decree extended payouts by another three instalments of R$300 (US$55.83).

Enrolment could be done through the Government Single Registry of Social Programs (CadUnico, acronym in Portuguese), which consolidates information on families receiving social benefits, or through an online registration of new beneficiaries (ExtraCad). More than half of the beneficiaries were not registered in any social programme. This created additional challenges, e.g. how to identify and verify the eligibility of these new entrants. Brazil adopted a fully online strategy to enrol new individuals, but not all vulnerable people had access to the internet or a cell phone. Additionally, problems with incomplete applications or documentation had to be solved in person, which led to long waiting lines in social security offices and banks throughout the country (Veloso, Citation2020).

Interaction of social policies and pandemic response

The impact of the programme is impressive. As a result of the Emergency Allowance, poverty fell to a historic low of 50 million people, the lowest level since the 1970s. Poverty reduction was higher in poorer northern and northeastern states (Neri, Citation2020).

Beneficiaries of the Emergency Allowance had the lowest rates of social distancing. In August, 6.15% of this group was in full at-home lockdown, while 40.7% reported to be remaining at home and leaving only for basic necessities. These numbers are below the average for the Brazilian population. Thus, while social policy influenced income levels, the poor demonstrated lower levels of adherence to social distancing measures imposed in response to the pandemic. A possible explanation of these findings is that social programme beneficiaries tend to work in service or informal jobs, which by their very nature, do not allow for as much implementation of social distancing measures (Garcia, Citation2020). As the Emergency Allowance will end in December 2020, it is expected that 16 million people will return to poverty (Canzian, Citation2020).

Brazil’s impressive social policies were not designed in agreement with the MoH. Brazil’s response to COVID-19 was highly uncoordinated within the executive government, which contributed to poor compliance with NPIs. Ironically, despite Bolsonaro and his economic minister’s initial reluctance to increase public expenditure, the popularity of the president increased considerably as social policies were implemented (a term record of 37% good/excellent) (Datafolha, Citation2020). Whether this was serendipitous, or a shrewd political strategy, is unclear.

Germany

Germany shows how substantial social policy actions benefit the economy not only on a macro level, but also on a micro and individual level. The Eurozone's biggest economy put together an aid package of historic proportions (Bundesministerium der Finanzen [BMF], Citation2020). This package controlled unemployment and protected vulnerable groups such as single parents, pensioners and children were adequately and quickly protected without tremendous bureaucratic barriers and businesses large and small were sufficiently supported. Effective social policy enabled effective public health policy.

In the federal republic of Germany, the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) is the national authority for the prevention of communicable diseases. The RKI works with the responsible authorities on the federal and Länder level to develop and implement epidemiological and laboratory-based analyses as well as research on the cause, diagnosis and prevention of communicable diseases; however, the nationwide infection protection law Infektionsschutzgesetz assigns the 16 German Länder the task of determining and implementing specific measures (Bundesamt für Justiz und Verbraucherschutz, Citation2020). During the corona pandemic, this resulted in divergent measures and regulations as every Land had different rules to physical distancing, mask wearing and gatherings (Desson et al., Citation2020).

Social policy baseline

Germany might not be the most egalitarian society in Europe, but is the most equal society of the four that we discuss here, with substantially lower income, wealth, and, in most cases, racial inequities. It also has the most extensive and developed welfare state and public administration of the four with fiscally stronger federal states (Länder) and a high degree of shared rule between federal and state governments in the context of a national party system. These make its policies and institutions more resilient in crises. Notably, Germany has strong automatic stabilisers such as income support programmes and unemployment insurance, which limit the effects of downturns on peoples’ lives and the broader economy.

Social policy in pandemic response

The public health measures implemented by Germany to fight the pandemic resulted in a multitude of social, economic and political collateral and consequential damages (Iskan, Citation2020). To alleviate these losses, the government established substantial social policy actions including two social protection packages with the goal of cushioning the social and economic consequences of the corona pandemic. On 22nd March, federal Chancellor Angela Merkel took control by coordinating all of the Länder in a nationwide contact ban as well as the closure of all restaurants, bars, cafes and businesses in the field of personal care (hairdressers, tattoo studios, etc.) (Bundesregierung, Citation2020).

These stringent NPIs and other pandemic-related economic shocks created problems which social policy was intended to address. On 25th March, the German federal government put together a protective shield for employees, self-employed and companies in the largest aid package in the history of the Federal Republic (BMF, Citation2020) and the world's largest at the time (Jerzy, Citation2020). The budget measures totalled € 353.3 billion (about 9% of GDP) and the guarantees totalled € 819.7 billion (BMF, Citation2020). This financial aid umbrella helped secure necessary social policy action throughout the country resulting in less unemployment (Urmersbach, Citation2020) and GDP losses less than the EU average as a result of the pandemic (Statista, Citation2020b).

On 27th March, the social protection package was implemented. This consisted of measures simplifying the process to attain additional benefits such as child allowances, grants for social services, continued employment after retirement and it extended the maximum duration for marginal employment (Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales [BMAS], Citation2020). While other countries such as Austria increased the bureaucratic hurdles people in need had to jump through to receive aid, Germany made things less challenging. Access to additional subsistence benefits and child allowance was simplified, further grants for social services were made available and additional earnings for people in ‘Kurzarbeit’ were made possible (BMAS, Citation2020).

On 28th April, the Social Protection Package II was implemented wherein the social protection in the event of short-time work and unemployment as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic was improved. These measures included improved conditions for short-time work benefits, an extension of entitlement to unemployment benefits, warm lunches despite closings due to the pandemic and improvements to the Social Service Provider Employment Act (SodEG) thereby ensuring the continued payment of orphan's pensions (BMAS, Citation2020). Further financial protection measures for individuals included the child bonus, the child allowance, support for single parents, Kurzarbeit money and basic security (Bundesministerium für Familie Senioren Frauen und Jugend, Citation2020). These measures essentially expanded the existing programmes making more money available to particularly vulnerable groups (children, single parents and those with limited incomes).

The Corona aid for commercial and freelance companies was the largest aid package of its kind whose paramount goal was to support businesses of all kinds including start-ups, large businesses, SME’s as well as small (under 10 employees) businesses, the self-employed and freelancers. A total of €70.4 billion in corona aid had already been approved as of 13 October 2020 (Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie, Citation2020). The money has been allocated to everything from an economic stabilisation fund, quick credits, special programmes, merchandise credit, insurances and export credit guarantees to tax measures.

Interaction of social policies and pandemic response

Germany's emergency social policy showed results. Administrative burdens were limited, aid was targeted across most categories (individuals, families, businesses of all sizes and infrastructure) and the unemployment rate did not drastically increase (as was the case in other countries) Soforthilfe, immediate (financial) help, was intended to speed disbursement of funds and limit administrative burdens. The federal government provided €50 billion of easily available emergency aid for small businesses, self-employed and freelancers to cover operating costs for three months and they do not have to be repaid (BMF, Citation2020).

Thanks to the comprehensive aid package for commercial and freelance companies the unemployment rates increased compared to 2019 but did not do so substantially. In September of 2019, the unemployment rate in Germany was 4.9% and by September 2020 it increased to 6.2% (Brandt, Citation2020). The fact that the unemployment levels did not surge is a direct result of the Kurzarbeit scheme. According to the last available figure from August, 4.5 million people are receiving these short-time work benefits (Statista, Citation2020a). In fact, for the first time since the beginning of the coronavirus crisis, unemployment in Germany has fallen. According to the Federal Employment Agency, 108,000 fewer people were unemployed in September than in August (Bundesargentur für Arbeit, Citation2020). However, the balance looks less favourable compared to the previous year: In September 2019, 613,000 more people were employed than in September of this year (Brandt, Citation2020).

Discussion

While a strong public health response is arguably the most important and necessary step in addressing the urgent infectious threat, like COVID-19, it will not be sufficient to meet the short-term consequences and the longer-term impacts that disease control measures may have. As the case studies of Brazil, Germany, India and the United States demonstrate social policy matters for pandemic response and alignment between social policy and public health policy is crucial. Even if there are clear historical and political reasons why Angela Merkel's Germany was more politically inclined to supportive social policy than the Brazil of Bolsonaro, the India of Modi or the United States of Trump, recognising the need for social policy can affect advice and decision-making.

Paying attention to the social policy responses allows for a more nuanced glance at the social determinants of health. Underlying social and economic inequities exacerbate the health risks associated with the virus and are at risk of expanding if social policies are not implemented. Understanding the intersection between public health and social policy is also important because social policy is not only a way to address the short-term public health threat of COVID-19 but can also be an opportunity to address underlying social and economic inequities (Abrams & Szefler, Citation2020). Social policies are crucial in the short term, as they allow people to afford to comply with recommended and mandatory NPIs. Social policies are likely to continue to support people during the long-lasting hardships that individuals, organisations, and communities will likely face.

The duration of the COVID-19 pandemic means that social policy is also shaping the long-run consequences of the pandemic. Instead of a clearly defined period of emergency followed by recovery and ‘lessons learned’ reports, COVID-19 is a long-running crisis in which emergency measures might last for years. In particular, social policies taken in the context of emergency can shape the trajectory of a country’s recovery by determining whose losses are compensated and whose are not.

Our analysis has a number of limitations. The first is that our research strategy, which is designed to identify a similar dynamic across countries as well as across time within the countries that changed approaches, is better suited to finding similarities rather than identifying scope conditions. One obvious scope condition, though, is that the ability to rapidly enact social policy is not universal – not all countries have the money or state capacity, regardless of their politics. The second limitation, therefore, is that our hypothesis is broadly less likely to be relevant in lower-income countries as well as some middle-income countries with weakly developed social policy and large informal workforces (e.g. Ezeibe et al., Citation2020). Another obvious scope condition is that some states may be able to achieve compliance with public health by applying coercion in place of enabling social policies. That leads to the third limitation, which is that it seems a few authoritarian regimes (notably Vietnam and the People’s Republic of China) were able to ensure compliance with NPIs despite weak social policy. It is not clear that many regimes in the world have such a combination of authoritarian capacity and lack of popular democratic accountability; many authoritarian regimes saw poor compliance with NPIs in 2020 (and Vietnam largely kept the pandemic out in 2020, which reduced the need for broad NPIs and supportive solicy policy).

The fourth, finally, is that some countries that otherwise have little in common were able to ensure compliance with NPIs despite limited social policy measures. As far as we can tell, this was because they managed to control the pandemic inside their borders when there were only a few cases. Australia, Hong Kong, Mongolia, New Zealand, South Korea, Taiwan, and Vietnam, and arguably the People's Republic of China and Singapore were able to move quickly enough that long-lasting and socially or economically harmful NPIs were not required in most of 2020, which meant that their economies could function more or less normally and there was less damage for NPIs to redress.

The success and failure of public health emergency response depend on its alignment with social policy. Separating social policy and public health, in theory or in practice, undermines both, and heightens the risk that both will fail. Policymakers discussing pandemic response strategies now or in the future should pay close attention to social policy supports for their strategies in the face of public health emergencies.

Disclosure statement

SLG has consulted for the U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center and the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. MF has consulted for the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. No potential conflict of interest was reported by the other author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abrams, E. M., & Szefler, S. J. (2020). COVID-19 and the impact of social determinants of health. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 8(7), 659–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30234-4

- Adolph, C., Amano, K., Bang-Jensen, B., Fullman, N., & Wilkerson, J. (2021). Pandemic politics: Timing state-level social distancing responses to COVID-19. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 46(2), 211–233. https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-8802162

- Anderson, J., Bergamini, E., Brekelmans, S., Cameron, A., Darvas, Z., Jíménez, M. D., & Midões, C. (2020, June). The fiscal response to the economic fallout from the coronavirus. Bruegel.

- Athrady, A. (2020, June 25). Coronavirus lockdown: Indian Railways suspends regular train services till August 12. Deccan Herald.

- Brandt, M. (2020). Arbeitslosigkeit in Deutschland gestiegen. Statista.de. 2020. https://de.statista.com/infografik/22188/entwicklung-der-arbeitslosenquote-in-deutschland-waehrend-der-corona-krise/

- Bundesamt für Justiz und Verbraucherschutz. (2020). Gesetz zur Verhütung und Bekämpfung von Infektionskrankheiten beim Menschen (Infektionsschutzgesetz - IfSG). http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/ifsg/BJNR104510000.html#BJNR104510000BJNG000201116

- Bundesargentur für Arbeit. (2020). Entwicklung des Arbeitsmarkts 2020 in Deutschland arbeitsagentur.de. https://www.arbeitsagentur.de/news/arbeitsmarkt-2020

- Bundesministerium der Finanzen. (2020, March 13). Kampf gegen Corona: Größtes Hilfspaket in der Geschichte Deutschlands. https://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/DE/Standardartikel/Themen/Schlaglichter/Corona-Schutzschild/2020-03-13-Milliarden-Schutzschild-fuer-Deutschland.html

- Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales. (2020). Sozialschutz-Pakete [Internet]. bmas.de. https://www.bmas.de/DE/Schwerpunkte/Informationen-Corona/Sozialschutz-Paket/sozialschutz-paket.html

- Bundesministerium für Familie Senioren Frauen und Jugend. (2020). Finanzielle Unterstützung. https://www.bmfsfj.de/bmfsfj/themen/corona-pandemie/finanzielle-unterstuetzung

- Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie. (2020). Corona-Hilfen für Unternehmen https://www.bmwi.de/Redaktion/DE/Infografiken/Wirtschaft/corona-hilfen-fuer-unternehmen.html

- Bundesregierung. (2020, March 22). Pressekonferenz von Bundeskanzlerin Merkel zu der Besprechung mit den Regierungschefinnen und Regierungschefs der Länder zum Coronavirus. https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/suche/pressekonferenz-von-bundeskanzlerin-merkel-zu-der-besprechung-mit-den-regierungschefinnen-und-regierungschefs-der-laender-zum-coronavirus-1733286

- Canzian, F. (2020, October 8). Fim do auxílio emergencial levará 1/3 do país à pobreza. Folha de Sao Paulo.

- Children's Defense Fund. (2020). Child poverty in America 2017: National analysis. Children's Defense Fund. https://www.childrensdefense.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Child-Poverty-in-America-2017-National-Fact-Sheet.pdf

- Cole, D. (2020, October 23). White House Chief of Staff: “We are not going to control the pandemic”. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2020/10/25/politics/mark-meadows-controlling-coronavirus-pandemic-cnntv/index.html

- Datafolha. (2020, August 13). Aprovação de Bolsonaro sobe para 37%, a melhor do mandato, e reprovação cai para 34%.

- Desson, Z., Lambertz, L., Peters, J. W., Falkenbach, M., & Kauer, L. (2020). Europe’s Covid-19 outliers: German, Austrian and Swiss policy responses during the early stages of the 2020 pandemic. Health Policy and Technology, 9(4), 405–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlpt.2020.09.003.4

- Deweck, E., Oliveira, A., & Rossi, P. (2018). Austeridade e Retrocesso: Impactos Sociais da Política Fiscal No Brasil. Brasil Debate e Fundação Friedrich Ebert.

- Economic Times. (2020a, April 12). Coronavirus India live updates: Telangana follows Maha and West Bengal, extends lockdown till April 30.

- Economic Times. (2020b, May 15). India’s Rs 20 lakh crore Covid relief package one among the largest in the world.

- Elliott, H., Greer, S. L., & Mauri, A. (2019). United States: Territory in a divided society. In S. L. Greer & H. Elliott (Eds.), Federalism and social policy: Patterns of redistribution in 11 democracies (pp. 270–288). University of Michigan Press.

- Ezeibe, C. C., Ilo, C., Ezeibe, E. N., Oguonu, C. N., Nwankwo, N. A., Ajaero, C. K., & Osadebe N. (2020). Political distrust and the spread of COVID-19 in Nigeria. Global Public Health, 15(12), 1753–1766. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1828987

- Garcia, D. (2020, October 13). Pesquisa mostra que trabalho informal eleva contágio e morte por Covid-19 no Brasil. Folha de Sao Paulo.

- Government of India. (2021). Startup Scheme. https://www.startupindia.gov.in/content/sih/en/startup-scheme.html

- Greer, S. L. (2020). Debacle: Trump’s response to the COVID-19 emergency. In M. del Pero & P. Magri (Eds.), Four years of Trump: The US and the world (pp. 88–111). ISPI Open Access. https://www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/four-years-trump-us-and-world-27375

- Greer, S. L., King, E. J., Massard da Fonseca, E., & Peralta-Santos, A. (2020). The comparative politics of COVID-19: The need to understand government responses. Global Public Health, 15(9), 1413–1416. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1783340

- Greer, S. L., King, E. J., Massard da Fonseca, E., & Peralta Santos, A. (Eds.). (2021). Coronavirus Politics: The Comparative Politics and Policy of COVID-19. University of Michigan Press.

- Han, J., Meyer, B. D., & Sullivan, J. X. (2020). Income and poverty in the COVID-19 pandemic (No. w27729). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Hindustan Times. (2020, April 11). Covid-19: Karnataka extends lockdown by 2 weeks, throws in some relaxations.

- Iskan, S. (2020). Corona in Deutschland: Die Folgen für Wirtschaft, Gesellschaft und Politik. Kohlhammer Verlag.

- Jarman, H. (2021). State responses to the COVID-19 pandemic: Governance, surveillance, coercion and social policy. In S. L. Greer, E. J. King, E. Massard, & A. Peralta-Santos (Eds.), Coronavirus politics: The comparative politics and policy of COVID-19 (pp. 51–64). University of Michigan Press.

- Jarman, H., & Greer, S. L. (2020). What is the affordable care act a case of? Understanding the ACA through the comparative method. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 45(4), 677–691. https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-8255589

- Jerzy, N. (2020, April 22). Corona-Hilfen: Diese Länder geben am meisten aus Capital. https://www.capital.de/wirtschaft-politik/corona-hilfen-diese-laender-geben-am-meisten-aus

- Kugler, M., & Sinha, S. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 and the policy response in India. Brookings Institution.

- Maji, A., Sushma, M. B., & Choudhari, T. (2020). Implication of inter-state movement of migrant workers during COVID-19 lockdown using modified SEIR model. Mumbai. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2005.04424.pdf

- Markel, H., Lipman, H. B., Navarro, J. A., Sloan, A., Michalsen, J. R., Stern, A. M., & Cetron, M. S. (2007). Nonpharmaceutical interventions implemented by US cities during the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic. JAMA, 298(6), 644–654. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.6.644

- Mätzke, M. (2009). Welfare policies and welfare states: Generalization in the comparative study of policy history. Journal of Policy History, 21(3), 308–329. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0898030609090150

- McCarthy N. (2019, July). India lifted 271 million people out of poverty in a decade. Forbes.

- Neri, M. (2020). Covid, Classes Econômicas e o Caminho do Meio: Crônica da Crise até Agosto de 2020. FGV Social.

- Parrott, S., Stone, C., Huang, C. C., Leachman, M., Bailey, P., Aron-Dine, A., Dean, S., & Pavetti, L. (2020, March 27). CARES Act includes essential measures to respond to public health, economic crises, but more will be needed. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

- Piovesan, E., & Siqueira, C. (2020, March 23). Relator anuncia acordo para auxílio emergencial de R$600. Agência Câmara de Notícias.

- Ragin, C. C. (1987). The comparative method: Moving beyond qualitative and quantitative strategies. University of California Press.

- Rajan, S., Cylus J, D., & Mckee, M. (2020). What do countries need to do to implement effective ‘find, test, trace, isolate and support systems? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 113(7), 245–250. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076820939395

- Rasella, D., Aquino, R., Santos, C. A. T., Paes-Sousa, R., & Barreto, M. L. (2013). Effect of a conditional cash transfer programme on childhood mortality: A nationwide analysis of Brazilian municipalities. The Lancet, 382(9886), 57–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60715-1

- Rocco, P., Béland, D., & Waddan, A. (2020). Stuck in neutral? Federalism, policy instruments, and counter-cyclical responses to COVID-19 in the United States. Policy and Society, 39(3), 458–477. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2020.1783793

- Singer, P. M., Willison, C. E., Moore-Petinak, N., & Greer, S. L. (2021). Anatomy of a failure: COVID-19 in the United States. In S. L. Greer, E. J. King, E. Massard, & A. Peralta-Santos (Eds.), Coronavirus politics: The comparative politics and policy of COVID-19 (pp. 478–493). University of Michigan Press.

- Skocpol, T., & Somers, M. (1994). The uses of comparative history in macrosocial inquiry. In T. Skocpol (Ed.), Social revolutions in the modern world (pp. 72–98). Cambridge University Press.

- Statista. (2020a). Anzahl der Kurzarbeiter in Deutschland von 1991 bis 2019 (Jahresdurchschnittswerte) und in den Monaten von Januar bis Oktober 2020 [Internet]. https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/2603/umfrage/entwicklung-des-bestands-an-kurzarbeitern/

- Statista. (2020b, October 1). Europäische Union: Arbeitslosenquoten in den Mitgliedsstaaten im August 2020. https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/160142/umfrage/arbeitslosenquote-in-den-eu-laendern/

- Times of India. (2020, September 2). G. R. Salary cut, 900 Kerala Covid doctors resign.

- Titmuss, R. (2001). What is social policy. In P. Alcock, H. Glennerster, A. Oakley, & A. Sinfield (Eds.), Welfare and wellbeing: Richard Titmuss's contribution to social policy (pp. 209–214). Policy Press.

- Urmersbach, B. (2020). Aktuelle Prognosen zur Entwicklung des BIP weltweit in der Corona Krise Veröffentlicht. Statista.de.

- USDA. (2020, October). United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Food Security and Nutrition Assistance. https://docs.google.com/document/d/14WPyq1INBdvkkoABusxnzlLx7AyTE-UmJ5Vyb_6E_zE/edit#

- Veloso, A. (2020, April 28). Agências da Caixa voltam a ter longas filas. Extra.

- Woolf, S. H., & Schoomaker, H. (2019). Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States, 1959-2017. JAMA, 322(20), 1996–2016. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.16932

- World Bank. (2020). COVID-19 in Brazil: Impacts and policy responses.