ABSTRACT

Understanding the mechanisms through which social norms shape contraceptive use can help prevent unintended pregnancies in low-income countries. The Nigerian Urban Reproductive Health Initiative (NURHI) aimed to increase contraceptive uptake through advocacy, service delivery, and demand generation. Using data from focus group discussions, we examined whether social norms around family planning (FP), and specifically use of modern contraception (MC), varied among women and girls of reproductive age exposed to varying levels of the programme in three Nigerian cities. Injunctive social norms were generally unfavourable of unmarried adolescent girls’ use of MC, though participants often shared exceptions for certain types of adolescents whose use of MC would be acceptable. There was greater acceptability for MC use by women who wanted to space or limit pregnancies. Participants reported that norms around FP and MC use have become more accepting in their communities over time. Normative differences between cities were identified. Participants’ perceptions of religious leaders’ support for FP use may have contributed to positively influencing social norms.

Introduction

Social norms, loosely defined as what people in a group believe to be normal – a typical action, appropriate action, or both – govern all parts of human behaviour, including health behaviour (Cialdini et al., Citation1991). Empirical findings from studies in high-income countries have greatly contributed to our understanding of the intersection of social norms and a wide range of health behaviours (Gidycz et al., Citation2011; McAlaney & Jenkins, Citation2015; Peterson et al., Citation2009). Much of this work has focused on the relationship between social norms and the use of alcohol and drugs in high-income countries (Foxcroft et al., Citation2015; Jones, Citation2014; Prestwich et al., Citation2016). There is less evidence around the influence of social norms on health behaviours in low-income countries (Cislaghi & Heise, Citation2019b). However, the family planning (FP) and reproductive health (RH) community is increasingly interested in understanding the mechanisms through which social norms shape fertility preferences and contraceptive use among women, men, and couples in low-income countries, with the goal of preventing unintended pregnancies in these contexts (Costenbader et al., Citation2017).

Distinguishing between descriptive norms – beliefs about what other people do – and injunctive norms – beliefs about what other people think one should do (Cialdini et al., Citation1991; Cialdini & Trost, Citation1998) – is important for deconstructing how norms affect health behaviours and conceptualizing how to intervene on those norms to improve health outcomes (Ajzen, Citation2015). While there is ample evidence that gender norms influence contraceptive use (Okigbo et al., Citation2018; Mejia-Guevara et al., Citation2020; Adams et al., Citation2013), these norms are generally operationalised as attitudes towards gender equity or gender roles (Cislaghi & Heise, Citation2019a). Similarly, collective (social) norms also influence fertility and other FP-related behaviours (Kaggwa et al., Citation2008; Sedlander & Rimal, Citation2019; Storey & Kaggwa, Citation2009), but these are measured as the occurrence, or objective prevalence, of FP-related behaviours or attitudes. In contrast, the evidence around whether and how FP descriptive and injunctive social norms are associated with contraceptive behaviours is limited and varies by norm type and geography. A study in India showed that descriptive norms around FP moderated the effects of spousal influence and interpersonal communication on married women’s use of modern contraception (MC) (Rimal et al., Citation2015). Another study from the Democratic Republic of Congo found that injunctive FP norms among married women and descriptive FP norms among married men were associated with future intention to use MC (Costenbader et al., Citation2019). In Kenya and Ethiopia, a study by Dynes and colleagues highlighted that the alignment or divergence between injunctive norms and personal perceptions about the ideal number of sons influenced women’s MC use (Dynes et al., Citation2012).

Interventions that influence social norms around healthy behaviours may be part of a sustainable solution to improving health status because once norms have shifted, all pieces of the intervention do not need to continue (Cislaghi & Heise, Citation2019a). For example, interventions that demonstrate a misalignment between behaviour and norms can correct misperceptions and attitudes among a core group of people (Berkowitz, Citation2010). This core group can then become change agents in their communities, challenging community members’ perceptions of what others in their communities approve of (Cislaghi & Heise, Citation2019b). This strategy was used in Mali through an intervention that utilised a curriculum, community mobilisation, and dialogue to shift norms, attitudes, and behaviours around female genital mutilation (FGM). Positive changes over time in injunctive norms around FGM were observed in intervention communities, with the greatest change among curriculum participants and their adoptees (persons who participants chose to have dialogues with), and less change observed among other members of the intervention community. No changes were observed in control communities (Cislaghi et al., Citation2019). This suggests that community members can systematically share newly acquired knowledge and understanding with others in their networks and eventually facilitate social norms change.

While family planning investments in Nigeria have been ongoing for decades and knowledge of contraceptive methods is high – about 93% of women of reproductive age have knowledge of at least one contraceptive method – demand for and use of contraceptives remains low (National Population Commission (NPC)/Nigeria and ICF International, Citation2019). Among married women, total demand for FP increased from 31% in 2013 to 36% in 2018. Any contraceptive and MC use increased from 15% and 10%, respectively, in 2013 to 17% and 12%, respectively, in 2018 (National Population Commission (NPC)/Nigeria and ICF International, Citation2014, Citation2019). There is wide geographical variation, with estimates of MC use in 2018 among married women ranging from 3.9% in the North-West region to 25.4% in the South-West region, and total demand for FP ranging from 21.1% in North-West to 57.4% in South-West (National Population Commission (NPC)/Nigeria and ICF International, Citation2014, Citation2019).

Strategic behaviour change communication and interventions that go beyond shifting individual-level attitudes and behaviours have been a relatively recent focus of interventions in sub-Saharan Africa, including Nigeria (Costenbader et al., Citation2019; Ejembi et al., Citation2015). From 2009 to 2014, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) supported the Nigerian Urban Reproductive Health Initiative (NURHI) with the aim of increasing voluntary use of modern contraceptives among women ages 15–49 years in six large cities: Abuja, Ibadan, Ilorin, Kaduna, Benin and Zaira. NURHI received a second grant from BMGF to implement NURHI Phase 2 in three states: Lagos and Kaduna (2015-2020) and Oyo (2015-2018). NURHI aimed to increase contraceptive uptake through advocacy, service delivery, and demand generation (Adedini et al., Citation2018). Demand generation elements included mass media campaigns through radio and television spots, entertainment-education, and social mobilisation through outreach activities. NURHI’s advocacy strategy complemented demand generation efforts by working with policy makers, religious and traditional leaders, and the media to create an enabling environment supportive of FP. NURHI incorporated the theory of ideation, which purports that people’s actions are influenced strongly by their beliefs, ideas, and feelings. Ideation factors include personal attitudes and beliefs (i.e. what a person knows about FP and how they think it will affect them), and social norms (i.e. what a person believes other people will think of them if they use FP). NURHI hypothesised that demand generation elements of the programme would work together to influence ideation factors, including social norms (Krenn et al., Citation2014). NURHI was implemented in one or two phases depending on the location. For further details in the NURHI intervention, please see Krenn et al. (Citation2014) and Adedini et al. (Citation2018). This study focuses on social norms around FP, specifically MC use, among residents of the cities of Kaduna (who were exposed to NURHI 1 and 2), Ilorin (exposed to only NURHI 1), and Jos (not exposed to NURHI).

The objectives of our study are two-fold: First, to qualitatively describe social norms around MC across three locations with varying levels of the NURHI programme and assess differences in norms by location. Second, to examine differences in norms by reason for MC use (preventing first pregnancy, spacing between pregnancies, and limiting childbearing).

Methods

This study uses data from focus group discussions (FGDs) to understand norms around acceptability and use of MC and reported changes in norms over time. In each city, six FGDs were conducted with married and unmarried women between ages 15 and 39 years; 175 women participated across 18 FGDs. Community guides recruited participants using convenience sampling at popular spots within the communities including markets and transportation hubs. Recruitment was undertaken by marital status and age group (15–24 or 25–39) in Christian-majority and Muslim-majority areas as seen in . All study procedures including the study protocol, recruitment procedures, consent forms, and qualitative data collection guides were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH) (No. 17-1215) in the United States and the National Research Ethics Committee of Nigeria (No. NHREC/01/01/2007).

Table 1. Number of participants per FGD.

Data collection instruments and implementation

Research team members from UNC-CH and Centre for Population and Reproductive Health (CPRH) at the University of Ibadan in Nigeria conducted a literature review of social norms measures used in FP studies, and solicited input from multiple stakeholders and subject matter experts in Nigeria and the US to jointly develop the FGD guides. The guides used vignettes to elicit discussion of social norms around contraceptive acceptability and perceptions of use and method choice. FGD questions centred around the constructs of injunctive norms (beliefs about what their community would find acceptable), descriptive norms (beliefs about what women in their communities are doing) and personal attitudes (beliefs about what a character should do). Three vignettes were developed that included (1) a 16-year-old unmarried young woman who was sexually active with her 17-year-old boyfriend and was considering using modern contraception after learning a friend got pregnant; (2) a 21-year-old mother with a six-month-old baby who wanted to space her next pregnancy while her husband wanted another child immediately; and (3) a 28-year-old woman with four children who wanted to prevent future pregnancies. The guides were finalised following pilot testing in Abuja and were translated into Yoruba and Hausa.

The study was implemented after the NURHI intervention was phased out in Ilorin and while it was ongoing in Kaduna. Researchers from CPRH trained local data collectors who collected data in June and July 2018. FGD moderators explained the study to all potential participants; notified them of the voluntary and confidential nature of the FGD; and obtained verbal consent. FGDs were held in private locations, such as community rooms in hospitals and empty classrooms. FGDs lasted, on average, 90 minutes. They were conducted by a moderator and a notetaker and were digitally recorded.

Analysis

Following transcription and translation of FGDs into English, data were uploaded and coded in Dedoose software (v.8.3). After reading transcripts, the lead author created a priori codes based on the research questions and FGD guides. Additional codes were added based on topics and themes that emerged from the transcripts. The lead author and second author worked together to establish coding standards and double-coded sections of one transcript to assess intercoder reliability (k = 0.9). The remaining transcripts were coded by the lead author, with the second author reviewing randomly selected transcripts for consistency.

We applied thematic analysis to systematically identify themes, connections, and patterns in the data through the use of coding and the creation of matrices (Guest et al., Citation2012). We created matrices for community acceptability of MC use, perceptions of the level of MC use in the community, personal attitudes and acceptability of MC use, and changes in MC norms over time. We synthesised code reports into matrices, arranging data by location, age of FGD participants, and type of vignette. This allowed for comparison across domains and identification of similarities and differences between FGD age groups, locations, and reasons for use of MC.

Results

We present results as follows: (1) injunctive norms, personal attitudes, and descriptive norms around non-marital use of MC by adolescents to prevent the first pregnancy; (2) injunctive norms, personal attitudes, and descriptive norms around the use of MC by married women to space or limit pregnancy; and (3) perceptions of changes in norms over time.

Non-marital MC use to prevent first pregnancy

In general, strong injunctive norms held that participants’ communities would deem it unacceptable for the adolescent girl in the vignette to have sex and use MC. Participants said the community would consider the adolescent to be ‘senseless’, ‘useless’, and ‘wayward’ because she was having sex outside of marriage. Some expressed stronger negative reactions saying the adolescent was a ‘harlot’ and would ‘ruin the community’; and some blamed the parents or upbringing. One participant stated:

People in the community would think that she doesn’t have discipline and she is shameless. And for a girl that is not married [that] is after men … she would be look[ed] at as a useless girl and they would see that her parent lacks respect. It would be said that it is the parent that let her to go out after men. Married, 15–24 years, Kaduna

Typically, participants first described the strict community and religious standards that prohibited an unmarried adolescent girl from having sex and using MC, followed by varied personal attitudes that alluded to or directly stated that they believed MC was acceptable in certain situations for the adolescent to continue schooling or to prevent abortion:

… the community people will think this girl is a wayward girl and a senseless girl, because if she is sensible, what will make her … want to use these things? Why not … be patient until she gets a husband to marry. Also, children of nowadays … not all will want to be patient until she gets a husband [to] start having children, so [rather than] getting pregnant and … aborting, it is better to do this family planning, it’s better, it is reasonable in my own thinking. Married, 25–39 years, Jos

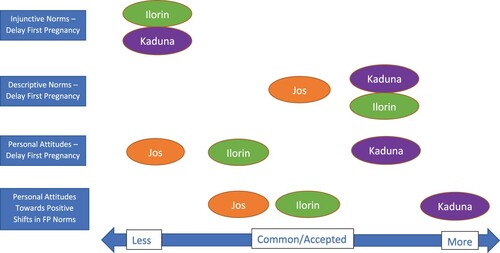

There were no clear differences across locations in injunctive norms, but there were marked differences in personal attitudes. Most participants in four of the six FGDs in Kaduna noted they would personally find unmarried adolescents’ use of MC acceptable in certain circumstances, while most women in only two FGDs in Ilorin and one in Jos stated there were situations where MC would be personally acceptable (see ). There were also small differences between older and younger FGD participants with young women expressing slightly more accepting attitudes of MC compared to older women.

Figure 1. Strength of social norms and personal attitudes favouring use of MC for delaying first pregnancy by study location.

When asked what the girl in the vignette should do, there were mixed personal opinions including the need for prayer, receiving support from an advisor, focusing on school, and, often, getting married, as illustrated below:

She should get married instead of destroying her life … It is better for her to marry than to be following men. Since she can have [a] boyfriend, definitely she can get married. Married, 25–39 years, Jos

… So, the best she should do, she and her boyfriend should meet a specialist because they have gotten so addicted to [sex] that they are not even thinking of staying away from [it], rather looking for solutions for her not to get pregnant. So, they should get … a doctor or a specialist that will advise them on what to do. Unmarried, 15–24 years, Jos

The idea of seeking an ‘advisor’ or ‘counsellor’ for the adolescent to talk to about sex and MC surfaced in about half of the FGDs and was often discussed as an option to help adolescents abstain.

She should just stay off sex. Try and get herself a mentor. I think that is what we lack today in our society. In those days we used to look up to people like this aunty [or] we want to be like this big sister … so I think that child should look for somebody that she admires … Married, 25–39 years, Jos

It is not acceptable … There is no situation that would warrant anything like that, even in a case of a girl that maybe she got raped at an early age - that is not a reason or an excuse for her to engage in subsequent sexual intercourse because at that age a lot of things could go wrong. She could fall pregnant she could abort you know; anything can go wrong and cause damage to her reproductive health. Married, 25–39 years, Ilorin

Despite the perceived lack of community acceptance and mixed personal attitudes towards premarital sex and adolescent’s use of contraception, most participants believed the adolescent would use MC, and that unmarried girls in their communities were using MC. There were some differences across locations with participants in three FGDs in Kaduna, three in Ilorin and one in Jos stating that unmarried girls in their communities were using MC (see ). Some participants noted that they had friends who helped their daughters get MC so the girls did not bring shame on their families; other participants shared that they would take their daughters to access MC.

Participant 12: There are some places in our community that as soon as the lady become 14 or 16, they will [give] family planning [to] her by themselves …

Moderator: So, there are some people that actually [give] family planning for children?

Participant 12: Yes, they [give] it for their children because they don’t want them to have an unwanted pregnancy.

Moderator: Is it [in] Muslim communities or both [Muslim and Christian]?

Participant12: Both.

Participant1: Some parent may not know that their child has done family planning, but friends can group themselves together and go for family planning without their parents notice and they will start flirting around. Married, 15–24 years, Ilorin

There were no clear differences in descriptive norms by age or marital status of respondents, or whether they were recruited in Christian- or Muslim-majority areas.

MC use for spacing and limiting pregnancy

In the spacing and limiting scenarios, participants voiced greater community acceptability around FP and MC use to delay pregnancy while raising a young child or limiting the number of children after having four. Participants acknowledged that not all community members would be supportive, as some might think the woman was using MC to ‘sleep around’ or because she was dissatisfied with her marriage. However, most felt that the community would understand and support the mother, especially given the young age of the child in the spacing scenario:

Participant 10: The community will advise her to do the family planning.

Moderator: Okay. Why do you think they will advise her to do it?

Participant 10: A six-month-old child and you want to get pregnant; it will be stressful for the mother and if care is not taken, something might happen to the six-month-old baby [or] even the baby she wants to give birth to. Married, 15–24 years, Ilorin

Some participants shared that the woman with the 6-month-old would be viewed as ‘wise’, and neighbours would know she wanted to take good care of her children. There were examples of the woman facing negative judgements from community members if she were to get pregnant soon, since it could be risky to the baby’s or mother’s health. Compared to reactions to the vignette about the unmarried adolescent girl, there were fewer descriptions of negative sanctions around the use of MC for spacing and limiting, and several descriptions of positive sanctions the married women would experience. For example:

… Because if she does that [uses FP] people would see her as someone who is taking care of her children and they are in good health … and she is taking care of them as she should and that would attract them to what she is doing. Married, 25–39 years, Kaduna

There was slight variation across locations with respect to injunctive norms in the spacing and limiting scenarios. In Kaduna and Jos women in four FGDs in each site believed there would be community support for use of MC by the vignette character to space her pregnancies, while women in three FGDs in Ilorin believed there would be community support. Only two out of six FGDs in each location were asked about community support for the vignette character to limit her pregnancies; both FGDs in Kaduna and one of the two FGDs in Ilorin and Jos believed there would be community support for limiting pregnancies.

While participants reported that some people in the community would not support MC, they overwhelmingly believed that, as the primary caregiver, the right decision for the woman with a 6-month-old was to use MC.

Participant 3: In my own little knowledge since I have a child and he is six months, and he is insisting that I should get pregnant again I will just go and take drugs quietly then if the child is up to a year or a year and [some months] then I will allow pregnancy to enter.

Participant 9: What I will say is similar because I feel that it is better for her to continue … with the family planning because if she leaves it, she would be the one to suffer for it. The husband would only make her pregnant, but the suffering is her own and it is her body. So, it is better for her to take the family planning so that when it is the right time then she can stop it. Married, 25–39 years, Kaduna

Participants were divided on whether the woman should use MC secretly or take her husband to a clinic to be convinced or ‘enlightened’. Some recommended she use only traditional methods and others noted she should get tested for the kind of method that ‘agrees with her body’. FP and MC were also cited to protect the health and wellbeing of mother and child, including maternal mortality and subsequent remarrying by the husband. Challenging economic situations and school fees were often cited as additional reasons to support using FP.

While MC use for limiting by the vignette woman with four children was usually deemed personally acceptable, there were multiple instances of participants saying the woman should use MC to give her body ‘a rest’, and then decide if she wanted more children. Others felt she should follow her husband’s requests or were against MC because four children might not be enough, especially if any of them died. Others indicated MC was a clear choice.

Participant 4: There is nothing for her to do than for her to do her family planning. That is it.

Moderator: What is the reason why you have said she should go and do family planning?

Participant 4: When she doesn’t want to give birth again, she already has four children, and she feels there is nothing for her again after four children. What she can do is to subscribe for childbearing control measures. Married, 25–39 years, Ilorin

In both the spacing and limiting vignettes, the pattern identified in descriptive norms aligned with injunctive norms and personal attitudes, with participants reporting that FP and MC use were generally acceptable and common in their communities.

Moderator: What do people in this community think that women like this woman … are actually doing?

Participant 4: They are thinking since that is what is best for her, she should do the spacing – that is what they [women in this community] are doing. Married, 25–39 years, Jos

Like injunctive norms, there was only slight variation across locations regarding descriptive norms. In Jos and Ilorin each, participants in three FGDs, and in Kaduna participants in four FGDs, believed other women in their communities used MC to space their pregnancies. Additionally, participants in one FGD in Jos and Kaduna each, and two in Ilorin, believed that women in their communities used MC to limit childbearing. There were no notable differences across age, marital status, or religious-majority areas within each of the three study cities regarding norms for use of MC to space pregnancies and limit childbearing.

Perceptions of changes over time

In nearly all FGDs, there was general agreement that community views on FP and MC use have changed over time. Participants reported that both community perceptions (injunctive norms) and practices (descriptive norms) have shifted:

… in our [community] parents are thinking [family planning] is a normal thing now, everybody is seeing it … Definitely we are in a world now that everything is just, you know, everything is just changing day by day. … But people now are seeing it as a normal thing. Because even if you talk or not, they will still go ahead and do [family planning]. Unmarried, 15–24 years, Jos

Most groups discussed the change in injunctive norms as helpful for preventing and planning pregnancies. There were positive voices in almost all FGDs, and particularly strong sentiments in Kaduna that identified the shift in community acceptability as a positive change for young women:

The community has accepted that family planning is not a bad thing. The word is, if a young girl in the community is seen and she is pregnant people will tell ‘What kind of fool are you? There is family planning. Go and do it now.’ But in the past, nobody will tell her to take that option … So, in my opinion, it is accepted and has changed people’s perception positively. Married, 25–39 years, Kaduna

Civilization has come and this civilization is what has caused a lot of havoc on earth. That is why a 17-year-old girl, 15-year-old girl say they are doing family planning, which ought not to be, and any parent who has a daughter still under her and doesn’t know what she is into, and what our children of these days are getting into. We, their mothers, dare not, we would be scared. But they have no fears. Married, 25–39 years, Ilorin

There were also many examples of women reporting that men’s opinions on FP had shifted. Participants stated that men were recently more willing to allow their wives to use FP, and some men had even begun asking their wives to go to FP clinics. Some of these changes were described within the context of rising economic challenges of raising and supporting children in present-day Nigeria.

Participants also reported that formal and informal clinic policies have changed over time. In the past, women were required to be accompanied by their husbands to clinics to be able to access MC. Similarly, clinics had previously refused to provide contraceptives to adolescents, but some have recently changed this.

When asked about the factors that influenced changes in community perspectives, policies and practices, participants across locations mentioned hospitals, government, and churches being involved. FGDs in Kaduna and Ilorin often reported that churches supported the use of FP to help couples plan their family size and encouraged couples to have only the number of children they could care for:

Like the church that I attend, our pastor used to say to us ‘give birth to only the number of children you can cater for within your means. So, for some of you that just keep giving birth to children, when it comes to pay school fees and feeding the family, it becomes difficult for you’. So, the pastor advice that we should plan and space the birth of our children. Four children, three children, five children should be ok. After you have given birth to them, you can now adopt modern contraception. In my case, when he (the pastor) did the dedication of my last daughter, that’s the fifth child, he said ‘I don’t want to come here for any dedication again unless it is university graduation ceremony for your first child, then you can think another baby … … … ’ (laughter). Married, 25–39 years, Kaduna

NGOs and government programmes were consistently mentioned in Ilorin and Kaduna, while several FGDs in Jos specifically noted that no NGOs discussed FP in the area. Compared to other locations, more participants in Jos described normative changes resulting from women talking to each other and awareness from hospital education. The economy was a strong and recurring theme that was reported as influencing increases in FP use, especially because of the need to pay school fees, and was mentioned in Jos more often than in the other two locations.

Posters, billboards, flyers, and door-to-door education were mentioned in Kaduna and Ilorin, but not in Jos. Radio and TV programmes were mentioned in every FGD in Ilorin and almost every FGD in Kaduna:

Through advertisement, almost all radio stations now after an interval of 30 min, they will advertise for people to go and do family planning. At least when you have about 4 children, that is enough so go for family planning. Married, 25–39 years, Ilorin

Yes, they show advert like that on family planning on how people can protect themselves and their family. All these programmes you watch [on television]. Married, 25–39 years, Kaduna

The programmes that promoted child spacing were reported to have the NURHI tagline of ‘go for family planning’. Most participants indicated there were no FP programmes directed specifically at young people, though several participants noted the changes in community acceptability of and practices around FP applied to MC use among young people, with some examples of mothers taking their adolescents to FP clinics to help their daughters prevent pregnancy and stay in school. One participant described her own initial reluctance to learn about and discuss FP methods with her daughter, followed by a change in personal attitude:

There were some NGO that came and do it for my children. When they saw my daughter and she asked me questions about family planning then I sat quiet, I couldn’t give her any answer but later I felt some strength, then I said I will stand up, I don’t feel any shame for my children. I have big daughters that are up to eighteen and I am not ashamed of them, then I said that is this advice good for them. Married, 25–39 years, Kaduna

Discussion

Our data reveal some normative differences between locations regarding community acceptance and use of contraception, and substantial differences across locations in personal attitudes. Compared to Jos, FGD participants in Kaduna and Ilorin more often reported they believed that sexually active unmarried adolescents in their communities were using MC to delay the first pregnancy. FGD participants in Kaduna also held the most accepting personal attitudes towards unmarried adolescents’ use of MC, particularly to support better life outcomes such as continued schooling and preventing abortions. Given that NURHI was implemented in Kaduna and Ilorin where participants reported being exposed to the programme messages through churches, posters, billboards and flyers, these findings suggest that NURHI may have influenced norms and attitudes to be more positive towards adolescent girls’ use of MC. However, given the qualitative design of the study, establishing a causal association is not possible.

The pattern of differences across locations in norms and attitudes towards MC use for spacing pregnancies and limiting childbearing is less clear. This may be because MC use in these situations was generally more accepted and common, especially compared to use among unmarried girls, and a smaller range of existing differences may not be detectable using qualitative methods.

While all FGDs reported that FP and MC use has become increasingly accepted and common over time, there were differences by location in participants’ attitudes towards those norm changes. Shifts in norms were most accepted by individuals in Kaduna and least accepted by individuals in Jos. This may reflect different levels of discordance between norms and attitudes across locations, with the least discordance in NURHI cities, reflecting the potential positive influence of the NURHI programme on attitudes towards MC use.

Strong injunctive norms around the unacceptability of unmarried adolescent girls having sex stands in contrast to descriptive norms, that is, participants’ perceptions that adolescent girls are having sex. Many participants were adamant that the unmarried adolescent in the vignette should not be sexually active, and therefore should not use MC; but subsequently stated that she would use MC – and in some cases, that she should use MC. This demonstrates nuanced differentiation between descriptive and injunctive norms for unmarried adolescent girls’ RH behaviours. Many respondents offered caveats to qualify their beliefs that the adolescent girls should use MC (e.g. to not bring shame to her family, etc.), likely to reconcile the dual and contrasting motives of descriptive and injunctive norms. The different roles for injunctive and descriptive norms in response to RH behaviours suggest that social standards for unmarried adolescent girls in Nigeria (i.e. the expectation for sexual abstinence) are not aligned with the immediate self-interest of young women (i.e. the desire to have sex) (Jacobson et al., Citation2011). Evidence from US-based studies indicates that the perception that a behaviour is common can aid a group of people to partake in that behaviour, even if they believe the behaviour is not socially acceptable (Jacobson et al., Citation2011). To increase contraceptive use, future interventions should capitalise on existing descriptive norms in Nigeria to communicate that many unmarried adolescents who are having sex are also using contraceptives.

The pervasive belief that adolescents and young women should not have sex outside of marriage is not a new finding in Nigeria or in other settings (Alli et al., Citation2013; Bello et al., Citation2017; Mejia-Guevara et al., Citation2020; Paul et al., Citation2016) and must be considered during the design phase of youth FP programmes and policies. Study participants had noted that they were not aware of any FP programme in their areas that encouraged young people specifically to use contraception, and that church programmes for young people focused on abstinence. One potential leverage point that emerged in our data is the idea of training and working with existing advisors or counsellors for mentoring young unmarried women. This is similar to findings from another study in Nigeria in which adolescents suggested that programmes provide girls with mentors to support them to make good sexual and reproductive health decisions (Iwelunmor et al., Citation2018). Using the local tradition of female community members who act as advisors or counsellors to adolescents and young women could be an opportunity for future projects to advocate with this group for the health and social benefits of MC for unmarried sexually active women, including the ability to stay in school. Such advocacy would aim to shift injunctive norms, specifically in reference to the group of youth advisors, in support of contraceptive use. That is, young unmarried women would increasingly perceive that their female advisors support the use of contraception by unmarried women, thus increasing their adoption of contraception.

Participants in Kaduna and Ilorin reported that church programmes supported FP use for married women to space their pregnancies. This echoes another NURHI study that showed that 40% of women in four intervention states were exposed to religious leaders’ messages in favour of FP. There was also a significant association between exposure to the religious leaders’ messages and MC uptake (Adedini et al., Citation2018). Given NURHI’s focused work with religious leaders to increase male involvement and advocate for positive FP messages, these results indicate that sustained engagement with influential leaders can increase the use of MC. In fact, quantitative evaluations have found that the NUHRI programme has contributed to an increase in the use of MC in intervention areas (Measurement Learning Evaluation Project Nigeria Team, Citation2017), and that the effect of the first phase of NUHRI was sustained and associated with continued increases in MC use (Speizer et al., Citation2019). While attribution is not possible, the positive and sustained impact of the programme may have transpired, particularly in Kaduna, through positive changes in injunctive norms, particularly when considering religious leaders as an important reference group.

This study has several limitations. First, participants sometimes responded to questions about norms with their personal opinions. When it was unclear whether participants were referring to beliefs of what the community would find acceptable or their personal attitudes (or both simultaneously), the authors erred on the side of coding and analysing the data as personal attitudes. Since the greatest variation was found in reports of personal attitudes, the actual patterns of normative differences between locations and vignettes may be greater than what was identified. Additionally, because data were collected at one point in time, our ability to draw conclusions about change in norms and practices over time is based on participants’ recall and interpretation.

This study also has several strengths. First, the use of vignettes to discuss the perceived frequency and level of community acceptance of the character’s MC behaviours, and not that of the participants, may have reduced social desirability bias (Hughes & Huby, Citation2012). Additionally, differentiating between social norms for MC use to delay, space and limit pregnancies can aid in designing targeted MC programmes that meet women’s needs based on where they are in their reproductive lives.

The Government of Nigeria had set its 2020 target for modern contraceptive prevalence rate to 27% (FP 2020). While the country did not reach this target (Scoggin & Bremner, Citation2019), efforts must continue to focus on shifting social norms around MC, in addition to improving availability of and access to services and commodities. Shifting social norms through communication campaigns that include mass media, organised community dialogues, and influential and far-reaching change agents such as religious leaders, implicitly and explicitly encourages women to use FP to prevent, space and limit pregnancies throughout their life course and helps sustain contraceptive behaviours and fertility outcomes across communities and over time.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the data collectors at the Centre for Population and Reproductive Health, University of Ibadan, and the study participants. Under the grant conditions of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Generic License has already been assigned to the Author Accepted Manuscript version that might arise from this submission.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, M. K., Salazar, E., & Lundgren, R. (2013). Tell them you are planning for the future: Gender norms and family planning among adolescents in northern Uganda. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 123(Suppl 1), e7–e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.07.004

- Adedini, S. A., Babalola, S., Ibeawuchi, C., Omotoso, O., Akiode, A., & Odeku, M. (2018). Role of religious leaders in promoting contraceptive use in Nigeria: Evidence from the Nigerian Urban Reproductive Health initiative. Global Health: Science and Practice, 6(3), 500–514. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-18-00135

- Ajzen, I. (2015). The theory of planned behaviour is alive and well, and not ready to retire: A commentary on Sniehotta, Presseau, and Araujo-Soares. Health Psychology Review, 9(2), 131–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2014.883474

- Alli, F., Maharaj, P., & Vawda, M. Y. (2013). Interpersonal relations between health care workers and young clients: Barriers to accessing sexual and reproductive health care. Journal of Community Health, 38(1), 150–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-012-9595-3

- Bello, B. M., Fatusi, A. O., Adepoju, O. E., Maina, B. W., Kabiru, C. W., Sommer, M., & Mmari, K. (2017). Adolescent and parental reactions to puberty in Nigeria and Kenya: A cross-cultural and intergenerational comparison. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(4S), S35–S41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.03.014

- Berkowitz, A. (2010). Fostering healthy norms to prevent violence and abuse: The social norms approach. In K. L. Kaufman (Ed.), The prevention of sexual violence: A practioner’s sourcebook (pp. 147–172). NEARI Press.

- Cialdini, R. B., Kallgren, C. A., & Reno, R. R. (1991). A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 24(20), 201–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60330-5

- Cialdini, R. B., & Trost, M. R. (1998). Social influence: Social norms, conformity and compliance. In D. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (4th ed., pp. 151–192). McGraw-Hill.

- Cislaghi, B., Denny, E. K., Cisse, M., Gueye, P., Shrestha, B., Shrestha, P. N., … Clark, C. J. (2019). Changing social norms: The importance of ‘organized diffusion’ for scaling up community health promotion and women empowerment interventions. Prevention Science, 20(6), 936–946. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-019-00998-3

- Cislaghi, B., & Heise, L. (2019a). Gender norms and social norms: Differences, similarities and why they matter in prevention science. Sociology of Health & Illness, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13008

- Cislaghi, B., & Heise, L. (2019b). Using social norms theory for health promotion in low-income countries. Health Promotion International, 34(3), 616–623. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/day017

- Costenbader, E., Lenzi, R., Hershow, R. B., Ashburn, K., & McCarraher, D. R. (2017). Measurement of social norms affecting modern contraceptive use: A literature review. Studies in Family Planning, 48(4), 377–389. https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12040

- Costenbader, E., Zissette, S., Martinez, A., LeMasters, K., Dagadu, N. A., Deepan, P., & Shaw, B. (2019). Getting to intent: Are social norms influencing intentions to use modern contraception in the DRC? PLoS One, 14(7), e0219617. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219617

- Dynes, M., Stephenson, R., Rubardt, M., & Bartel, D. (2012). The influence of perceptions of community norms on current contraceptive use among men and women in Ethiopia and Kenya. Health & Place, 18(4), 766–773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.04.006

- Ejembi, C. L., Dahiru, T., & Aliyu, A. A. (2015). Contextual factors influencing modern contraceptive use in Nigeria (DHS Working Papers 120). ICF International. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/WP120/WP120.pdf

- Foxcroft, D. R., Moreira, M. T., Almeida Santimano, N. M., & Smith, L. A. (2015). Social norms information for alcohol misuse in university and college students. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 12, CD006748. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006748.pub4

- Gidycz, C. A., Orchowski, L. M., & Berkowitz, A. D. (2011). Preventing sexual aggression among college men: An evaluation of a social norms and bystander intervention program. Violence Against Women, 17(6), 720–742. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801211409727

- Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., & Namey, E. E. (2012). Applied thematic analysis. Sage Research Methods. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483384436

- Hughes, R., & Huby, M. (2012). The construction and interpretation of vignettes in social research. Social Work Social Science Review, 11, 35–61. https://doi.org/10.1921/17466105.11.1.36

- Iwelunmor, J., Blackstone, S., Nwaozuri, U., Conserve, D., Iwelunmor, P., & Ehiri, J. E. (2018). Sexual and reproductive health priorities fo adolescent girls in Lagos, Nigeria: Findings from free-listing interviews. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 17(30), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2016-0105

- Jacobson, R. P., Mortensen, C. R., & Cialdini, R. B. (2011). Bodies obliged and unbound: Differentiated response tendencies for injunctive and descriptive social norms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(3), 433–448. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021470

- Jones, S. C. (2014). Using social marketing to create communities for our children and adolescents that do not model and encourage drinking. Health & Place, 30, 260–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.10.004

- Kaggwa, E. B., Diop, N., & Storey, J. D. (2008). The role of individual and community normative factors: A multilevel analysis of contraceptive use among women in union in Mali. International Family Planning Perspectives, 34(2), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1363/ifpp.34.079.08

- Krenn, S., Cobb, L., Babalola, S., Odeku, M., & Kusemiju, B. (2014). Using behavior change communication to lead a comprehensive family planning program: The Nigerian Urban Reproductive Health Initiative. Global Health: Science and Practice, 2(4), 427–443. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-14-00009

- McAlaney, J., & Jenkins, W. (2015). Perceived social norms of health behaviors and college engagement in British students. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 41(2), 172–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2015.1070399

- Measurement Learning Evaluation Project Nigeria Team. (2017). Evaluation of the Nigerian Urban Reproductive Health Initiative (NURHI) program. Studies in Family Planning, 48(3), 253–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12027

- Mejia-Guevara, I., Cislaghi, B., Weber, A., Hallgren, E., Meausoone, V., Cullen, M. R., & Darmstadt, G. L. (2020). Association of collective attitudes and contraceptive practice in nine sub-Saharan African countries. Journal of Global Health, 10(1), 010705. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.10.010705

- National Population Commission (NPC)/Nigeria and ICF International. (2014). Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2013. NPC and ICF.

- National Population Commission (NPC)/Nigeria and ICF International. (2019). Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018. NPC and ICF.

- Okigbo, C. C., Speizer, I. S., Domino, M. E., Curtis, S. L., Halpern, C. T., & Fotso, J. C. (2018). Gender norms and modern contraceptive use in urban Nigeria: A multilevel longitudinal study. BMC Women's Health, 18, Article 178. doi:10.1186/s12905-018-0664-3

- Paul, M., Nasstrom, S. B., Klingberg-Allvin, M., Kiggundu, C., & Larsson, E. C. (2016). Healthcare providers balancing norms and practice: Challenges and opportunities in providing contraceptive counselling to young people in Uganda – a qualitative study. Global Health Action, 9(1), 30283. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v9.30283

- Peterson, J. L., Rothenberg, R., Kraft, J. M., Beeker, C., & Trotter, R. (2009). Perceived condom norms and HIV risks among social and sexual networks of young African American men who have sex with men. Health Education Research, 24(1), 119–127. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyn003

- Prestwich, A., Kellar, I., Conner, M., Lawton, R., Gardner, P., & Turgut, L. (2016). Does changing social influence engender changes in alcohol intake? A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(10), 845–860. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000112

- Rimal, R. N., Sripad, P., Speizer, I. S., & Calhoun, L. M. (2015). Interpersonal communication as an agent of normative influence: A mixed method study among the urban poor in India. Reproductive Health, 12, Article 71. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-015-0061-4

- Scoggin, S., & Bremner, J. (2019). FP2020: Women at the Center 2018-2019. Family Planning 2020.

- Sedlander, E., & Rimal, R. N. (2019). Beyond individual-level theorizing in social norms research: How collective norms and media access affect adolescents’ use of contraception. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64(4S), S31–S36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.12.020

- Speizer, I. S., Guilkey, D. K., Escamilla, V., Lance, P. M., Calhoun, L. M., Ojogun, O. T., & Fasiku, D. (2019). On the sustainability of a family planning program in Nigeria when funding ends. PLoS One, 14(9), e0222790. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222790

- Storey, J. D., & Kaggwa, E. B. (2009). The influence of change in fertility related norms on contraceptive use in Egypt, 1995-2005. Population Review, 48(1), 1–19.