ABSTRACT

While the United Nations has long implemented strategies to tackle deep-rooted gender-based inequalities and discrimination in its programmes and policies, there is limited evidence on successful strategies to foster institutional structures and practices that promote gender equality or institutional gender mainstreaming. This paper explores and analyses the experience of institutional gender mainstreaming within UN Agencies working on global health, highlighting potential areas for learning. Overall, progress on institutional gender mainstreaming has been modest, with slow increases (if any) in investments in financial and human resources. The findings highlight the importance of well-established strategies, such as enforcing accountability, a robust gender architecture, and a cohesive capacity-building policy. Drawing on the experiences of gender experts, the paper shows that equally or more critical to the success of institutional gender mainstreaming were approaches such as leveraging strategic internal and external support and identifying strategic entry points for gender mainstreaming. There is considerable scope for strengthening gender mainstreaming within UN Agencies by reviewing and learning from UN system successes. In addition to learning from practice, the way forward lies in making visible and developing strategies to challenge embedded patriarchal organisational norms and systems.

1. Introduction

Deep-rooted gender-based inequalities and discrimination, pervasive across all countries, pose a major threat to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for 2030, including ensuring healthy lives and wellbeing at all ages (UN Women, Citation2017). There is an urgent need to identify and implement evidence-based approaches to bring about gender equality in global health policies, programmes, and workplaces. Drawing on the many decades of experience promoting gender equality and women's empowerment within the United Nations (UN) Agencies working on global health could be a useful starting point. There are many reasons for focusing on the experiences of UN Agencies. The United Nations System (UNS) has extensive outreach globally and works in diverse socio-economic, cultural, and political settings. The UNS has also been at the forefront of promoting gender equality since the first World Conference on Women in Mexico in 1975. It has set global norms and standards and reviewed progress periodically.

The Beijing Platform for Action, adopted at the 1995 UN World Conference on Women, established gender mainstreaming as a strategy in international gender equality policy. In 1997, the UN Economic and Social Council (UNECOSOC, Citation1997) defined gender mainstreaming (GM) and officially adopted it into all UNS policies and programmes. Since 2012, UN Women has been coordinating the UN's gender mainstreaming efforts through the UN Sector-Wide Action Plan on Gender Equality and Women's Empowerment (UN-SWAP).

At an institutional level, gender mainstreaming calls for addressing gender equality and women's empowerment concerns in the organisation's rules and policies and in its way of doing business referred to as ‘institutional gender mainstreaming.’ Addressing gender equality and women's empowerment concerns in the strategies, programmes, and projects implemented by the organisation is called ‘programmatic gender mainstreaming’ (Ravindran & Kelkar-Khambete, Citation2008; UNEG, Citation2018). It is widely acknowledged, including in the UN-SWAP conceptualisation, that institutional gender mainstreaming constitutes the essential foundation for programmatic gender mainstreaming (UN Women, Citation2012).Footnote1 Consequently, institutional gender mainstreaming has received considerable attention in many UN Agencies.

UN Agencies working on global health have achieved small to moderate gains in corporate gender policies and gender architecture, developing tools and guidelines, and building capacity for gender mainstreaming (ADB, Citation2012; UN ECOSOC, Citation2017; UN Women, Citation2015). Within each organisation, a small group of committed gender champions have found ways to keep the gender agenda alive and move it forward whenever a window of opportunity presented itself. We could learn from their experiences and ensure more effective gender equality work in global health.

Unfortunately, there is limited descriptive and analytical information on gender mainstreaming experiences, especially on institutional gender mainstreaming, within the UN Agencies and beyond, supporting such learning. This paper is a modest attempt at pulling together the available evidence on the implementation of gender mainstreaming at the institutional level within key UN Agencies working on global health. This paper seeks to

assess the institutional gender mainstreaming policies and practices of selected UN Agencies with mandates in health, and

document promising strategies and continuing challenges in institutional gender mainstreaming among the Agencies, drawing on gender experts’ experiences within the Agencies.

2. Methods and materials

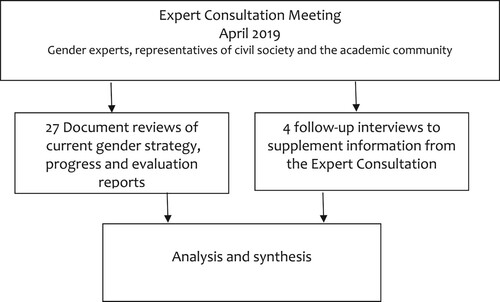

We collected data on six UN Agencies working on global health: UN Women, UNAIDS, UNDP, UNFPA, UNICEF, WHO. Although UN Women does not technically have a direct health mandate, it was included because of the intersection of its mandates with health-related targets in the SDGs and given its inclusion as a key global health institution under the SDG 3 Global Action Plan (WHO, Citation2019). This paper employed a mixed-method qualitative approach involving an expert consultation, a document analysis, and follow-up interviews to supplement information gathered in the consultation (see ). The data-collection process utilised in this paper is part of a larger study that received ethics approval from the Institutional Review Board, Monash University in Malaysia.

In April 2019, a two-day expert consultation of 30 gender experts from the six UN Agencies, civil society, and academia was convened in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia by the United Nations University International Institute for Global Health (UNU-IIGH) and WHO Headquarters, to take stock of progress in gender mainstreaming, and to critically assess the factors that have contributed to successes and failures (Lopes et al., Citation2019). The experts were identified in consultation with the UN Agencies. All participants consented to the use of the proceedings of the meeting as data for this study. As a neutral convener within the UNS, the UNU-IIGH provided technical and logistic support and the space to enable exchange and conversations, generate and identify practice-based evidence and action gaps to effectively deliver on gender and health. While UNU-IIGH partners with and supports UN agencies on gender equality, its staff and associates maintain their academic independence. This positionality allows us to critically reflect on the UN system’s response to gender mainstreaming and ensure objectivity and impartial analysis of evidence and meeting outputs.

We also carried out a document analysis in preparation for the meeting, which included current strategic plans and policies related to gender, the most up-to-date progress reports to governing bodies, and UN-SWAP evaluations. All Agency documents (e.g. strategic plan, gender strategies and annual reports) were purposively selected from the Agencies’ websites. For reports such as the UN-SWAP, most of which were not publicly available, they were requested directly from the Agencies. The documents were reviewed by two team members and analysed deductively with pre-determined themes utilising the institutional categorisation of gender mainstreaming provided by the UN-SWAP framework. We then highlighted and synthesised texts regarding Agencies aspirations and (or) commitments, and where possible, the actions taken and successes (if any) drawing on the annual and UN-SWAP reports.

We complemented the data from the expert group meeting and document analysis with follow-up interviews with four purposively selected key informants from the WHO, UNICEF, and UN Women (see ). These were mid-and senior-level gender specialists with over 10 years of work experience in gender in the UNS, and they were selected from the expert consultation invitees to further clarify or unpack ongoing challenges and promising strategies that had been raised. With prior informed consent, semi-structured interviews were remotely conducted, audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and analysed. The interview transcripts were reviewed by two team members and coded by themes inductively (emerging issues from document reviews) and deductively, along the critical domains of institutional gender mainstreaming. Data from the strategic plans and gender equality strategies provided context and insights into an agency’s commitment to gender mainstreaming. The UN-SWAP and annual gender reports provided evidence of the translation of policy commitment (or ongoing efforts) on gender equality and women empowerment into action. The expert consultative meeting report and interview data highlighted practice-based strategies that have enabled gender mainstreaming within the UN system. Collectively, these data sources allowed us to confirm, clarify and obtain an overview of the experience and critical challenges of implementing gender mainstreaming within the UN global health agencies

3. Results

3.1. Institutional gender mainstreaming: approaches and experiences

All six Agencies have an institutional mandate for gender mainstreaming. Five of the six Agencies (except for WHO) are guided by a Gender Equality Strategy or a Gender Action Plan with clear objectives and indicators. WHO has a gender policy dating back to 2002, a gender mainstreaming strategy adopted by a World Health Assembly resolution (2007) and more recently (2014-2019), a roadmap for implementing its gender, equity and rights-related goals (WHO Citation2013).

Key areas of action towards institutional gender mainstreaming across the Agencies may be broadly categorised into the following four areas:

Advancing gender parity across staff levels and gender-equal work environment

Building a robust gender architecture and building staff capacity

Committing financial resources to institutional and programmatic gender mainstreaming

Strengthening accountability for gender equality

3.2.1. Advancing gender-parity across staff levels and gender-equal work environment

presents the latest available data on gender parity in the six UN Agencies. UN-Women is the exception, with 80% of overall staff being women and a women majority across all levels. UNAIDS, UNFPA, and UNICEF have just achieved or are close to achieving gender parity among all fixed and permanent employees. UNDP and WHO have yet to achieve overall gender parity among their fixed or permanent positions. However, women remain underrepresented in senior positions at the P5, D1, and D2 levels across all organisations.

Table 1. Gender parity in fixed/permanent/continuous positions in the six UN Agencies, 2017.

In the context of organisational change, to facilitate an inclusive, diverse, and safe environment for gender equality and the empowerment of women, all the organisations have policies in place for preventing and addressing sexual exploitation and abuse, and sexual harassment (UNAIDS, Citation2018a; UNDP, Citation2018; UNFPA, Citation2017; UNICEF, Citation2019; WHO, Citation2017ab). Additionally, most of the Agencies (e.g. UNAIDS, UNDP, UNICEF, WHO) highlight processes and strategies to enhance staff empowerment through a healthy work-life balance. Some of the facilitative policies include the single parental policy–including adoption, surrogate, and paternity leave (4–18 weeks), maternity leave (16–28 weeks), and time off for breastfeeding; study leaves; flexible work arrangement – e.g. compressed hours, teleworking and breastfeeding facilities (UNAIDS, Citation2018a; UNDP, Citation2018; UNICEF, Citation2018; WHO, Citation2015). Beyond these, UNAIDS's GAP has called for an interagency effort to consider coverage of pre-school costs and childcare facilities, a dimension not emphasised in the UN-SWAP reports (UNAIDS, Citation2018a).

In the expert consultative meeting and in the follow-up interviews, some gender experts observed that despite efforts, most organisations in the UN System were intrinsically patriarchal and hierarchical. Unless ways were found to alter the gender power dynamics within the organisational culture, they would not expect gender parity or the policies advancing gender equality to make a significant difference in the workplace.

3.2.2. Gender architecture and staff capacity-building

Effective gender mainstreaming in the Agencies’ activities calls for adequate in-house gender expertise to provide leadership and technical guidance for achieving gender equality objectives.

The nature and strength of the gender architecture vary across the Agencies. Both document review and interviews highlighted the presence of a team of gender specialists working at the Headquarters level across all Agencies. However, not all Agencies have staff with exclusive responsibility for gender mainstreaming at the Regional Office level. At the Country Office level, gender expertise is more limited, with gender specialists in some countries, and non-expert Gender Focal Points (GFP) holding responsibility for gender mainstreaming in others. Gender Focal Points are also critical actors in the gender architecture, although they often do not have clear terms of reference or dedicated time allocation for their work on gender per UN-SWAP requirement. The WHO has an integrated gender, human rights, and equity unit at the Headquarters. In most Regional Offices, a single person is responsible for these three areas.

Many participants in the expert meeting and all key informants raised concerns about the limited gender capacity in Country Offices and, in some instances, even in Regional Offices or Headquarters of Agencies. There also is an absence of gender specialists in technical departments or sectors. Even when gender positions are filled, there often is a lack of ‘appropriate’ gender capacity, i.e. the ability to apply the tools of gender analysis to any technical area in health, using a language that the technical staff can easily understand. The ability to spell out how to make a programme gender-responsive requires a high level of gender expertise. There was a sense that the practice of appointing non-specialists to hold gender portfolios may be counterproductive given the wide range of specialised areas in health.

The document review showed that most Agencies have ongoing activities to build gender capacities across all staff. Some of these are mandatory, such as ‘I know gender,’ for all UN Agencies; UNFPA's ‘One Voice’ course on gender analysis in all programming; UNDP's mandatory ‘Gender Journey’ course for all staff. WHO has a virtual course on ‘Gender and Health: Awareness, Analysis, and Action’. The Gender-Pro is a promising capacity-building initiative by UNICEF and is described in detail in the next section on ‘promising strategies.’ The focus of these activities is the dissemination of technical knowledge on gender and its intersections with health. In most instances, however, sex and gender continue to be defined in binary terms and as homogenous categories. In addition to these, several programme-specific and ad-hoc training workshops are also mentioned in the reports analysed.

The reports of capacity-building initiatives focus more on the number of staff trained. The effectiveness of these training initiatives in enhancing technical staff capacity for gender mainstreaming is not clear. In the expert consultations and interviews, several respondents were concerned that capacity-building initiatives for technical staff, while important, often miss the mark. For example, one key informant highlighted a gap in most gender training workshops for technical staff within the UN system, noting that while ‘participants learn a lot about gender, some cannot see how this knowledge will translate into modified action on the ground’. Staff needed to be provided with the essential ‘skills to apply the tools of gender analysis to their respective technical areas.’

3.2.3. Committing financial resources for gender mainstreaming.

Three Agencies – UNAIDS (Citation2018a), UNDP (Citation2018), and UNICEF (Citation2018) – have benchmarks of 15% of their programme budgets for programming for gender equality and women's empowerment (GEWE). Data from their respective UN-SWAP reports indicate progress, with some (UNICEF, UNAIDS, and UNFPA) exceeding their benchmark in the most recent period (UNICEF, Citation2019; UNAIDS, Citation2018b; UNFPA, Citation2018). In the case of WHO, allocations on gender sit under a budget heading combining ‘Gender, Equity, Rights, and Social Determinants.’ The approved budget for this heading in 2018–19 was US$ 50.5 million, representing 1.14% of the total WHO budget for that period (WHO, Citation2017b). We could not find information on gender-related activities funded as part of other technical programmes.

3.2.4. Strengthening accountability for gender equality.

The Gender Action Plans emphasise political and leadership commitments from senior management as key to changing gender unequal hierarchies and discriminatory practices and striving towards gender-equitable outcomes, both within programmes and institutional processes (UNAIDS, Citation2018a; UNDP, Citation2018; UNICEF, Citation2018; WHO, Citation2013).

The extent of leadership accountability for gender equality and women's empowerment varied across the Agencies. Some Agencies (e.g. UNICEF, UNDP, and UNAIDS) have assigned primary responsibility to executive leadership (e.g. heads, deputies, administrators, regional and country directors/reps), supported by steering committees with oversight and implementation responsibilities. While the organisational Gender Action Plans provide an overarching framework, the executive officers at Regional and Country Offices are responsible for developing context-specific and appropriate actionable and measurable goals. Other Agencies have assigned responsibility to a gender department/unit (e.g. GER Unit, Gender, and Human Rights), which works in collaboration with other branches (e.g. Evaluation Unit) within the organisation to implement and monitor gender results (WHO, Citation2013).

However, while the top leadership is nominally accountable, several expert consultation participants indicate that much of the pressure for delivering on gender mainstreaming falls on the often understaffed and poorly funded gender unit. In addition, there are no effective and (or) mandatory organisational mechanisms to ensure that the responsibility of gender-related work is driven by the leadership of all technical divisions. In some instances, when committed gender champions in the Agencies, who had worked against all the odds and continuously strived to win support for the gender agenda from senior management and peers, move to another position or location, gains have been lost, with some agencies having to ‘go back to square one’.

Another accountability mechanism for institutional gender mainstreaming is the Gender-Marker, a tagging system that allows Agencies to assess the degree to which each expenditure contributes to gender equality results and mainstreaming. (UN Women, Citation2020). While the gender marker is key to revealing gaps in financing for gender programming, the lack of a coherent approach to implementation within and across agencies does not allow for cross-comparison and potentially risks being used as another box-ticking tool. For example, the UNFPA codes at the activity level, UNDP at the output level, and UNICEF at intermediate results (UNDP, Citation2018; UNFPA, Citation2017; UNICEF, Citation2018).

Beyond these in-house accountability mechanisms, the UN-SWAP represents an important mechanism to hold Agencies accountable for delivering gender mainstreaming across the UN system. A detailed description of the UN-SWAP follows in the next section on promising strategies (UN Women, Citation2020).

3.2. Promising strategies for incremental progress in institutional gender mainstreaming

This section presents six strategies identified in the expert meeting and supplemented with information from subsequent key informant interviews. Amidst formidable challenges, gender experts have found these strategies to have contributed towards some advances in institutional gender mainstreaming and contributed to programmatic gender mainstreaming.

There is no systematic evidence that all these strategies have led to positive outcomes for gender equality or health. However, discussions from the meeting and interviews highlighted that they are promising practice-based examples of how the UN Agencies and the gender champions within them have strived to keep the gender mainstreaming agenda alive and moving forward. While the strategies are described discreetly, there are many overlaps, and, in most instances, it is the simultaneous adoption of multiple strategies that contributed to the success.

3.2.1. Developing accountability frameworks

Many informants acknowledged the UN-SWAP as representing a significant step in providing a UNS-wide mandate for gender mainstreaming, which stimulated action within their respective Agencies. The UN-SWAP requires all UN Agencies to report on 17 indicators, most of which pertain to institutional gender mainstreaming. These are consolidated into a UN system-wide report to the Secretary-General and agency-specific reports on the achievements and opportunities to advance gender equality and women's empowerment.

According to a key informant from UN Women, the UN-SWAP has managed to achieve much more for institutional gender mainstreaming within a short span of seven to eight years (2012–19) compared to what had been possible between 1995 and 2012. Three reasons for this success were highlighted. First, the UN-SWAP enabled each UN Agency to move forward at its own pace without any cross-agency comparisons. In the first phase of UN-SWAP, the ratings of individual Agencies were not published; only aggregate data on the UN system gender mainstreaming efforts were reported. Secondly, the UN-SWAP was flexible and gave UN Agencies room to address the different UN-SWAP elements (financial and human resources, political will, policy systems, planning, capacity, and audit) one step at a time. Third, the UN-SWAP had created an interagency community of about 400 gender focal points (GFPs) in human resources and gender departments, which served as a supportive space for the gender focal points to share problems and seek solutions. Since its inception, the UN-SWAP help build buy-in among staff, ensuring that gender was no longer perceived as the exclusive responsibility of the gender focal points. For example, reporting on some indicators also lies with the administrative and financial divisions of Agencies.

Other informants pointed out some critical limitations. Performance assessment is based on self-reporting, with no requirements for cross-validation. More importantly, there are no apparent consequences or remedial action if progress is not being made. Nevertheless, the UN-SWAP has created a benchmark of minimum institutional requirements for gender mainstreaming and thus represents an important gain.

3.2.2. Using external evaluations as springboards for accelerating institutional gender mainstreaming

Some gender champions within Agencies found recommendations by external evaluation reports to be important entry points for action on gender mainstreaming. For example, an external evaluation of the HIV programme in the WHO recommended that the programme address gender issues, which gave gender experts an opening to push for action within the division. In UNICEF, a detailed gender assessment that documented suggestions from gender experts and Gender Focal Points from various levels in the organisation became the basis for significantly strengthening the Agency's gender architecture (see section 3.2.3). In both instances, the push forward became possible because of the simultaneous adoption of other strategies, as described below.

3.2.3. Putting in place a robust gender architecture

According to participants in the expert-group meeting, a robust gender architecture is critical and should follow a hub-and-spoke model, where the ‘hub’ consists of gender experts at the Headquarters and in the Regional Offices, and the ‘spokes’ are the gender experts within each major division or sector. At the same time, each Country Office should also have a gender focal point with a substantive proportion of time allocated to gender mainstreaming.

As an example, a robust gender architecture meeting this description was put in place in UNICEF, making it possible for the organisation to make advances in programmatic gender mainstreaming. A key informant who had prepared a gender assessment report in the Headquarters indicated that the number of in-house gender experts had dwindled during the previous decade. The regional directors of the Agency favoured strengthening gender architecture because it would result in additional gender capacity in the Regional Offices. The Agency's governing board also supported the move and allocated the requisite funds.

The process of hiring senior gender advisors (P5 level) for Regional Offices was streamlined. The hiring was completed in a single batch, with uniform terms of reference for all. The regional advisors were to report to the deputy regional director, which placed them in a position of power with direct access to the top leadership. Together, the senior gender experts at the Headquarters and Regional Offices became the Agency's core gender team. They identified a strategic area of focus, developed a common strategy, and communicated regularly through a monthly video conference. Soon, the larger Country Offices (with more than a US$ 20 million annual budget) were challenged to try and meet the ‘standard’ of having a dedicated gender person. UNICEF also invested in developing gender expertise within each sector through an innovative capacity-building initiative, as described in section 3.2.4.

3.2.4. Cohesive organisation-wide efforts at building capacity

All the gender experts interviewed believed that a single technical unit at the Headquarters or one or two gender experts at the Regional and Country Offices cannot meet in-house requirements for gender mainstreaming. There was a need for gender expertise among other technical staff. For example, technical staff working on climate change, non-communicable diseases, or nutrition should be enabled to carry out gender analysis within their respective subject areas. There was a sense that short-term and ad-hoc gender and health training workshops do not help build capacity for gender mainstreaming across all technical areas. UNICEF's GenderPro is perceived as an example of an initiative developed to meet this critical gap.

Funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the ‘Gender Pro’ Initiative is a Capacity-Building and Credentialing Program hosted at the George Washington University in partnership with UNICEF. The programme is designed to be hands-on and skills-oriented and adopts a blended format, with a 14-week online programme and three days of in-person learning. It involves about an hour and a half of work per week across about four months, and an applied practicum focused on a work deliverable (Global Women's Institute, Citation2020).

The Credentialing System consists of an evaluation of candidates on their demonstrated skillset in gender. The assessment is done by the GenderPro Credentialing Board, consisting of subject experts from George Washington University and other universities around the world. There is a two-level credentialing system for Gender Specialists and Sector Gender Specialists (e.g. gender and education; Gender and health). Any candidate with gender expertise may apply for credentialing. While those who complete the GenderPro Capacity Building Program are expected to fulfil the credentialing competencies, they must apply for the credential, as this is not automatically awarded (Global Women's Institute, Citation2020).

The first batch of forty technical staff from UNICEF's health and education sectors completed their training in 2019. Being housed in a university, the Capacity Building and Credentialing Program has the potential to become self-sustaining, catering not only to UNICEF but also to other Agencies and organisations. This is a promising initiative that could enhance the competencies and skillsets of gender experts and contribute significantly to advancing gender mainstreaming within UN Agencies, bilateral donors, and countries.

3.2.5. Building and leveraging support from leadership and major divisions/sectors within the organisation

Gender champions within Agencies talked of their efforts at ongoing advocacy and engagement with organisational leaders at the Headquarter, Regional, and Country Office levels to build awareness and buy-in for gender mainstreaming. In-house gender experts used every possible opportunity to highlight the importance of gender for health, such as when writing speeches for senior managers and the top leadership and providing inputs to strategy documents.

When supportive and committed leaders came on board, this leadership was leveraged to institutionalise processes for gender mainstreaming. They could include gender-related objectives in the organisation's work plans or strategy documents or put structures and mechanisms in place to engage with priority sectors within the organisations.

Pushing the gender agenda forward within the organisation also called for support from and collaboration with other technical divisions and sectors. While the Gender units in all Agencies had to make an effort to secure buy-in from the technical leads, an organisation-wide mandate such as a Gender Strategy or Gender Action Plan made for a more enabling environment than in Agencies where a mandate did not exist. Two factors were crucial for a successful engagement. The first was the gender experts’ willingness to engage in a dialogue with experts from technical divisions and demonstrate that attention to gender would help the technical departments meet the desired health or sectoral outcomes more effectively. In one instance, the gender expert could demonstrate to the technical head that removing gender-based barriers to accessing care would help meet the programme’s objectives by increasing coverage for all. The second is the gender experts’ ability to translate gender concepts into practical and tangible actions. Merely stating that their programme must become gender-responsive is often not helpful to the technical divisions. Technical experts were interested in knowing what would need to be done differently in terms of, for example, case-detection in tuberculosis or in health promotion outreach to prevent non-communicable diseases. Successful engagement became possible when gender experts could apply gender concepts to technical areas and keep abreast of emerging areas of concern such as climate change and digital health.

3.2.6. Using strategic entry points for gender mainstreaming

The Gender Action Plans and Strategies usually spell out priorities for programmatic gender mainstreaming, but not always. Gender experts at the meeting recommended three criteria, at least two of which must be satisfied, in order to choose a technical programme as an entry-point for gender mainstreaming. The first criterion is buy-in and commitment to gender mainstreaming from the concerned technical division or sector. The second and third criteria are donor interest and pressure from advocacy groups/civil society organisations for gender mainstreaming, respectively. According to one key informant, two programme areas that meet the above criteria and are ripe for gender mainstreaming within WHO are health systems and the health workforce.

In UNICEF's experience, identifying adolescent girls as the Agency's signature area of contribution was in keeping with the organisation's mandate of working for children's rights and wellbeing. This entry point allowed each of the organisation's sectors – health, education, and child protection – to identify their specific areas of action towards gender mainstreaming. Four areas of focus were chosen around adolescent girls’ lives and needs: ending child marriage, supporting married adolescents, preventing adolescent pregnancies, and increasing secondary schooling.

3.2.7. Leveraging strategic external support

Advocacy and engagement by the gender machinery within Agencies can be strengthened by advocacy and lobbying from stakeholders on the outside, particularly strong civil society actors and the Member States. For instance, there have been significant advances in gender mainstreaming in sexual and reproductive health, HIV/AIDS, and gender-based violence. These are areas where there is a long history of advocacy by civil society organisations and investment in evidence building by researchers. Building relationships with these external like-minded partners and stakeholders, including through collaborative initiatives, has been a useful strategy for successfully integrating gender concerns.

The presence of influential advocacy groups also often influences donor and Member States’ support for addressing gender concerns within specific health issues. The significant donor support, especially for HIV/AIDS and gender-based violence, has also triggered support and commitment for these issues from the Agencies’ top leadership.

Senior gender experts from UN Agencies also have leveraged support from their Executive Boards and Advisory Committees whenever an opportunity presented itself. For example, UNICEF's expansion of gender architecture was made possible from the support that in-house gender champions received from the Executive Board. In the UN co-sponsored Special Programme of Research on Human Reproduction (HRP) housed in the WHO, a Gender and Rights Advisory Panel (GAP) was constituted as far back as in 1996. The GAP has proved to be an essential institutional mechanism to mainstream gender and rights in research on sexual and reproductive health, building research capacity, and translating research to policy.

4. Discussion and conclusions

In this paper, we described the gender mainstreaming policies and practices of selected UN Agencies with mandates in global health and ongoing challenges. We then identified some promising strategies that can be leveraged to advance institutional gender mainstreaming to create the necessary conditions for successful programmatic gender mainstreaming.

Almost half a century has elapsed since the first International Conference on Women was held in Mexico in 1975, and gains have undoubtedly been made in advancing gender equality and women's empowerment. At the same time, it would not be an exaggeration to say that despite bold declarations, the UN's system-wide commitments, a plethora of conferences and workshops, progress on institutional gender mainstreaming has remained modest.

An organisation-wide mandate for gender mainstreaming existed in the Agencies studied but did not always translate into a clear road map for action, with accountability enforced. More attention has been paid to some domains, such as achieving gender parity. In contrast, the more difficult areas have made less progress, such as a robust gender architecture with the power and resources to implement gender-responsive health programmes.

Gender expertise at the senior level across all levels of an Agency is critical, without which little progress may be expected in programmatic gender mainstreaming. An early review of progress in institutional gender mainstreaming within UN Agencies, Moser and Moser (Citation2005) found that the most effective gender focal points tended to be gender specialists, appointed at a senior level and with an adequate budget. Ten years later, it was found that most gender focal point (GFP) networks and individual GFPs were predominantly junior staff who already have other full-time responsibilities. These responsibilities were not scaled back when they took on the responsibility of GFP. Most of them did not have clear terms of reference for their gender-related work (WHO, Citation2015).

Gender mainstreaming has received inconsistent support from most organisations’ top leadership and especially from the technical leads. Agency-level accountability structures do not seem to enforce answerability for gender mainstreaming among managers of technical programmes, making it the responsibility of the Gender Units to secure buy-in for gender concerns. While the UN-SWAP has provided a unifying framework in benchmarking progress towards gender mainstreaming across the UNS, it is focused on quantitative indicators. This is understandable, given that the framework is based on what is feasible across 66 UN entities (Kamioka & Cronin, Citation2019). It is important to remember that the UN-SWAP framework outlines the minimum requirements. Achieving these do not necessarily indicate that an Agency has succeeded in institutional (or programmatic) gender mainstreaming. Recent examples of UN Agencies with high UN-SWAP performance, which have done poorly in terms of preventing gender discrimination, sexual harassment, and abuse of power indicate the need to re-examine the UN-SWAP framework and process.

Gender experts in the UN Agencies have found strategies to make incremental changes within the constraints of their organisational culture and systems by leveraging the critical strengths available within and outside their organisations. These do not necessarily challenge the gender power inequalities within organisations, and the respondents were well aware of this.

A seminal paper by Longwe (Citation1997) helps us understand the ways in which gender inequalities are embedded in the culture of organisations and prove intractable. Longwe argued that unless patriarchal structures of powers within international organisations are tackled, gender mainstreaming would be unlikely to succeed. Gender policies would evaporate in the ‘patriarchal cooking pot.’ In other words, gender concerns would be wilfully ignored or not prioritised by multiple individuals at different bureaucratic chains, even when the institution makes a formal commitment to gender equality (Longwe, Citation1997). It appears that action for gender mainstreaming in the Agencies studied has prioritised relatively easier gains, tinkering with the periphery, leaving the ‘elephant in the room’ (i.e. patriarchal structures of power) untouched (Sandler et al., Citation2012).

What then needs to happen for meaningful institutional gender mainstreaming? Seminal work carried out by ‘Gender At Work’ points to a way forward (Rao et al., Citation1999; Rao et al., Citation2016; Rao & Kelleher, Citation2002; Rao & Sandler, Citation2012). This body of work focuses on the deep structures of organisations, conceptualised as a ‘collection of the deepest held, stated, and unstated norms and practices that govern gender relations in all societies’ (Rao et al., Citation2016, p. 5). Deep structures are internalised by the members of an organisation and need to be acknowledged, challenged, and changed to enable sustained gender equality in the workplace. They propose the ‘Gender and Work’ Analytical Framework that can be used to ‘make visible the deep structure of gender bias in organizations, develop strategies and change processes to challenge it, and map changes and outcomes to which these strategies have contributed’ (Rao et al., Citation2016, p. 9).

In addition to finding ways of addressing the many ongoing challenges to gender mainstreaming, including confronting patriarchal power structures, gender champions and experts must turn their attention to knowledge management and the generation of new knowledge, as well as conceptual advancement. The UN-SWAP's focus on institutional gender mainstreaming during its first five years (2012–2017) and the approach taken by many Gender Action Plans rest on the implicit assumption that institutional gender mainstreaming is a necessary condition for programmatic gender mainstreaming. While this assumption appears logical, we do not know enough about how, when, and under what circumstances one leads to the other. Two critical questions arise. Will institutional mainstreaming always support, accelerate, and sustain programmatic mainstreaming? Are there conditions under which programmatic gender mainstreaming may be possible even when institutional gender mainstreaming is not complete? We do not know, and research is needed to share insights into these linkages for better gender mainstreaming outcomes. If not, we may be in danger of ‘the means becoming the end’ – we could be investing substantially on a gender-equal organisational structure with little to show on the ground in terms of gender equity in health outcomes.

Our very understanding of gender mainstreaming needs to be updated, factoring in the conceptual developments in gender over the past quarter of a century. There has been a move away from gender as binary and fixed, acknowledging the broad spectrum of gender identities and the fluidity of gender identity and the intersection of gender with other axes of power-inequalities (Tolhurst et al., Citation2012). These developments have a greater bearing on programmatic gender mainstreaming and, consequently, important to consider when developing Gender Strategies and Gender Action Plans, thinking about gender parity and the gender architecture, planning the content of capacity-building initiatives, and defining what count as ‘gender projects’. This is also critical for resource allocation purposes.

There are some limitations to our analysis. First, the depth and extent of our analysis and conclusions about institutional gender mainstreaming across the Agencies are constrained by our reliance on available documents and experts present at the meeting. In the absence of complete datasets and a representative sample of experts for all Agencies, interpretations should be made with some caution. Further research is also needed to provide critical insights on promising strategies, particularly the contexts or mechanisms that enabled gender experts to drive change. Secondly, our focus was limited to institutional gender mainstreaming, which constitutes only one part of the gender mainstreaming agenda. More importantly, the information that we have provided on promising strategies does not allow us to capture the specific contextual factors that have enabled the strategies to work well. Further research on the contextual factors and mechanisms that lead to successful institutional and programmatic gender mainstreaming is critical for better-informed gender mainstreaming efforts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 ‘To be successful leaders on gender equality and women’s empowerment need clear guidelines as to what they are accountable for, aspirational indicators towards which to strive, and adequate resources and capacity in their entities.’ (UN Women, Citation2012, p. 3).

References

- ADB. (2012). Mainstreaming gender equality-a road to results or a road to nowhere? - Working Paper. https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/document/2012-mainstreaming-gender-equality-a-road-to-results-or-a-road-to-nowhere-working-paper-24585/.

- Global Women’s Institute. (2020). GenderPro. https://genderpro.gwu.edu/.

- Kamioka, K., & Cronin, E. (2019). Review of the United Nations System-Wide Action Plan on Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment (2012–2017). United Nations Joint Inspection Unit (UNJIU). JIU/REP/2019/2. https://www.unjiu.org/sites/www.unjiu.org/files/jiu_rep_2019_2_english_0.pdf.

- Longwe, S. H. (1997). The evaporation of gender policies in the patriarchal cooking Pot (L’évaporation des politiques relatives au genre dans la marmite patriarcale / A evaporação das políticas de gênero no caldeirão patriarcal / La evaporación de políticas de género en la cacerola patriarcal). Development in Practice, 7(2), 148–156. JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614529754611

- Lopes, C. A., Allotey, P., Vijayasingham, L., Ghani, F., Ippolito, A. R., & Remme, M. (2019). “What works in gender and health? Setting the agenda”. Meeting Summary Report, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia United Nations University-International Institute for Global Health. https://i.unu.edu/media/iigh.unu.edu/news/6852/UNU-IIGH_Final-Meeting-Report_What-works-in-Gender-and-Health.pdf.

- Moser, C., & Moser, A. (2005). Gender mainstreaming since Beijing: A review of success and limitations in international institutions. Gender & Development, 13(2), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552070512331332283

- Rao, A., & Kelleher, D. (2002). Unraveling institutionalized gender inequality. AWID Occasional Paper 8. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/278675390_Unravelling_Institutionalized_Gender_Inequality.

- Rao, A., & Sandler, J. (2012). E-discussion on gender & organizational change: Summary. Toronto: Gender at Work. http://www.genderatwork.org/Resources/GWintheNews.aspx.

- Rao, A., Sandler, J., Kelleher, D., & Miller, C. (2016). Gender at work. Theory and practice for 21st century organizations. Routledge.

- Rao, A., Stuart, R., & Kelleher, D. (1999). Gender at work: Organizational change for equality. Kumarian Press.

- Ravindran, T. K. S., & Kelkar-Khambete, A. (2008). Gender mainstreaming in health: Looking back, looking forward. Global Public Health, 3(sup1), 121–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441690801900761

- Sandler, J., Rao, A., & Eyben, R. (2012). Strategies of feminist bureaucrats: United Nations experiences. IDS Working Papers, 2012(397), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2040-0209.2012.00397.x

- Tolhurst, R., Leach, B., Price, J., Robinson, J., Ettore, E., Scott-Samuel, A., Kilonzo, N., Sabuni, L. P., Robertson, S., Kapilashrami, A., Bristow, K., Lang, R., Romao, F., & Theobald, S. (2012). Intersectionality and gender mainstreaming in international health: Using a feminist participatory action research process to analyze voices and debates from the global south and north. Social Science and Medicine, 74(11), 1825–1832. Epub 2011 Sep 24. PMID: 21982633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.025.

- UN. (2019). Mainstreaming a gender perspective into all policies and programmes in the United Nations system - Report of the Secretary-General. E/2019/54. United Nations. https://undocs.org/pdf?symbol=en/E/2017/57.

- UNAIDS. (2018a). Final Self-Report 2018 - UN-SWAP performance by indicator [Internal Report. Unpublished].

- UNAIDS. (2018b). Gender Action Plan, 2018–2023 — A framework for accountability. http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2018/jc2925_unaids-gender-action-plan-2018–2023.

- UNDP. (2018). Gender Equality Strategy 2018–2021. https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/womens-empowerment/undp-gender-equality-strategy-2018-2021.html.

- UNECOSOC. (1997). UN Economic and Social Council Resolution 1997/2: Agreed Conclusions. https://www.refworld.org/docid/4652c9fc2.html.

- UNECOSOC. (2017). Mainstreaming a gender perspective into all policies and programmes in the United Nations system. Report of the Secretary-General. E/2017/57. https://undocs.org/pdf?symbol=en/E/2017/L.22.

- UNEG. (2018). Guidance on Evaluating Institutional Gender Mainstreaming. (p:6). www.unevaluation.org › document › download 2827.

- UNFPA. (2017). Strategic Plan 2018–2021, DP/FPA/2017/9. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/DP.FPA_.2017.9_-_UNFPA_strategic_plan_2018-2021_-_FINAL_-_25July2017_-_corrected_24Aug17.pdf.

- UNFPA. (2018). SWAP Report 2018 [Internal Report. Unpublished]. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/DP.FPA_.2017.9_-_UNFPA_strategic_plan_2018-2021_-_FINAL_-_25July2017_-_corrected_24Aug17.pdf.

- UNICEF. (2018). Gender Action Plan, 2018–2021 (E/ICEF/2017/16). https://undocs.org/E/ICEF/2017/16.

- UNICEF. (2019). SWAP Report 2019 [Internal Report. Unpublished].

- UN Women. (2012). UN System-Wide Action Plan for implementation of the CEB United Nations System Wide Policy on Gender Equality and Women's Empowerment. (p. 3). https://unsceb.org/sites/default/files/High-Level%20Committee%20on%20Programmes/Public%20Document/SWAP.pdf.

- UN Women. (2015). Pre UN SWAP: What have we learned from evaluations? (TRANSFORM 5: 7–21).

- UN Women. (2017). Strategic Plan, 2018–2021, UNW/2017/6/Rev.1. http://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/executive%20board/2017/second%20regular%20session%202017/unw-2017-6-strategic%20plan-en-rev%2001.pdf?la=en&vs=2744.

- UN Women. (2020). Promoting UN accountability (UN-SWAP and UNCT-SWAP). UN Women. https://www.unwomen.org/en/how-we-work/un-system-coordination/promoting-un-accountability.

- WHO. (2013). Roadmap for action, 2014–2019, WHO/FWC/GER/15.2. https://www.who.int/gender-equity-rights/knowledge/roadmap/en/.

- WHO. (2015). Strategic approaches to reducing the gaps in gender parity in staffing 2016–17. https://www.who.int/gender-equity-rights/knowledge/gender-parity-in-staffing.pdf?ua=1.

- WHO. (2017a). Code of ethics and professional standards. Geneva. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/documents/ethics/code-of-ethics-pamphlet-en.pdf?sfvrsn=20dd5e7e_2.

- WHO. (2017b). Proposed Programme Budget 2018–19. Retrieved October 7, 2020, from https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA70/A70_7-en.pdf.

- WHO. (2019). Delivered by women, led by men: A gender and equity analysis of the global health and social workforce (No. 24; Human Resources for Health Observer Series). https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311322/9789241515467-eng.pdf?ua=1.