ABSTRACT

Young migrants in sub-Saharan Africa are particularly vulnerable to HIV-acquisition. Despite this, they are consistently under-served by services, with low uptake and engagement. We adopted a community-based participatory research approach to conduct longitudinal qualitative research among 78 young migrants in South Africa and Uganda. Using repeat in-depth interviews and participatory workshops we sought to identify their specific support needs, and to collaboratively design an intervention appropriate for delivery in their local contexts. Applying a protection-risk conceptual framework, we developed a harm reduction intervention which aims to foster protective factors, and thereby nurture resilience, for youth ‘on the move’ within high-risk settings. Specifically, by establishing peer supporter networks, offering a ‘drop-in’ resource centre, and by identifying local adult champions to enable a supportive local environment. Creating this supportive edifice, through an accessible and cohesive peer support network underpinned by effective training, supervision and remuneration, was considered pivotal to nurture solidarity and potentially resilience. This practical example offers insights into how researchers may facilitate the co-design of acceptable, sustainable interventions.

Introduction

Young migrants in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) are particularly vulnerable to HIV-acquisition (Camlin et al., Citation2010; Coffee et al., Citation2005; Jochelson & Leger, Citation1991; Schuyler et al., Citation2017), and thus constitute a population of unique public health significance (Bernays et al., Citation2020; Vearey, Citation2018) within the context of broader efforts to address the burden of adolescent HIV. In Eastern and Southern Africa, where the burden of global HIV is greatest (UNAIDS, Citation2020), 41% of new adult HIV-infections occurred amongst youth aged 15–24 years in 2018 (UNAIDS, Citation2020) (94,000 new youth infections in South Africa; and 19,000 in Uganda) (UNAIDS, Citation2020); with a disproportionate impact upon girls and young women (UNAIDS, Citation2020). These are settings characterised by widespread youth unemployment, affecting more than one-third of youth in South Africa and Uganda (stats sa, Citation2019; Uganda, Citation2017). Exposure to violence features prominently in their daily lives, with two-thirds of young people having experienced physical violence in South Africa and Uganda (Richter et al., Citation2018; Uganda, Citation2017), and one in four South African youth (Richter et al., Citation2018) and one in ten Ugandan youth (Uganda, Citation2017) reporting having experienced sexual violence. These risks are amplified by both interprovincial and international migration; with disadvantage most pronounced in rural provinces (stats sa, Citation2019).

Many young people in rural and remote SSA aspire for ‘a better life’ in a town, where they hope to find employment and forge their livelihood (Bond et al., Citation2011; Seeley et al., Citation2009). While their migration may not represent a large geographical distance (Barratt et al., Citation2012; Schuyler et al., Citation2017), the small towns to which they migrate offer a new social landscape (Barratt et al., Citation2012). Newly independent from their communities of origin, the young migrants are moving with increased autonomy in contexts of pervasive poverty, unemployment and sexual violence (Bernays et al., Citation2018). They experience a heightened risk of HIV acquisition (Camlin et al., Citation2010; Schuyler et al., Citation2017) and unintended pregnancy (Bernays et al., Citation2018). Patterns of early sexual debut, coercive and transactional sex, multiple sexual partners, and economic hardship exacerbate vulnerabilities, especially amongst adolescent girls (Bernays et al., Citation2020; Hardee et al., Citation2014).

From the early stages of the HIV epidemic to the present day, migration has been identified as a risk factor for young people (Erulkar et al., Citation2006; Olawore et al., Citation2018; Operario et al., Citation2011). Recent research indicates that young migrants are negotiating sexual behaviour decisions amidst exposure to broader sexual networks, loosened bonds with protective support networks, and often inequitable intergenerational and gender power relations (Jones, Citation2016). Consequently, with limited experience-based knowledge and skills, their increased mobility alongside limited caregiver surveillance and an increase in substance use (Bernays et al., Citation2020), results in greater potential involvement in exploitative relationships (including rape), and greater pressure to engage in sexual ‘transactions’ to ensure financial support (Erulkar et al., Citation2006; Operario et al., Citation2011).

Engaging young migrants in harm reduction services

The limited effectiveness of existing HIV services in engaging young migrants has been partially attributed to the practical difficulties in engaging an inherently transient population group. However, the argument that this group is ‘hard to reach’ has received increasing criticism and there is growing recognition of the need to develop contextually appropriate HIV services as a matter of central public health concern. This is particularly important given the influence that micro-epidemics may have in disrupting progress in broader HIV epidemic control efforts (Marukutira et al., Citation2019; Vearey, Citation2018).

A central principle in harm reduction services for young people is fostering sustained resilience. We adopt Fergus and Zimmerman’s definition of resilience: ‘the process of overcoming negative effects of risk exposure, coping successfully with traumatic experiences, and avoiding negative trajectories associated with risks’ (Citation2005, p. 399). A young person’s resilience may be contingent upon their personal, familial, community and religious resources (Fergus & Zimmerman, Citation2005; van Breda & Theron, Citation2010, Citation2018). However, resilience is fluid and shaped by context, changing with the risks faced and available protective factors (Kabiru et al., Citation2012). For a young migrant, away from their family and no longer in education, an important alternative factor is connectedness: being able to count on others to help materially and emotionally (Punch, Citation2015; Tutu, Citation2013). This connectedness, in which togetherness becomes a source of strength, may support young people to navigate and thus minimise the need to lean on ‘quick fixes’, such as providing sex in exchange for money to buy food.

Community based participatory research (CBPR) approaches, which invest time in developing a shared understanding of local problems and feasible solutions, have been shown to be an effective innovative strategy in addressing HIV-prevention issues in diverse and minority population subgroups (Corbie-Smith et al., Citation2011; Coughlin, Citation2016). We conducted research among young migrants living in small trading centres in South African and Uganda over a period of 15 months (2017–2019), to co-design an intervention with them that would meet their specific needs and would be appropriate for delivery in their local contexts.

In this paper, we delineate the logic underpinning the co-development of an intervention, which aims to address mobile youth’s intersecting vulnerabilities. In doing so, we provide an example of how researchers may facilitate the co-design of more acceptable, sustainable, capacity-enhancing health interventions. We present our applied theory of change to demonstrate how the intervention seeks to effectively foster protective factors in order to develop resilience in ‘high-risk’ settings, in ways that are locally pertinent (Breuer et al., Citation2016; De Silva et al., Citation2014; Fergus & Zimmerman, Citation2005).

Theoretical framing

In analysing the formative research, an alignment was identified between our empirical findings and the ‘protection-risk’ conceptual framework developed by Jessor (Citation1991), Jessor et al. (Citation2003), and subsequently adapted by Kabiru and colleagues in their research conducted among adolescents in Nairobi. Specifically, the need to consider the influence of both contextual and individual constructs in the determination of ‘risk’, and the potential to moderate this through enhancement of protective factors (Jessor et al., Citation2003; Olsson et al., Citation2003). This framework identifies three categories of risk factors: models risk, opportunity risk, and vulnerability risk; and three categories of protective factors: models protection, controls protection, and support protection (Jessor et al., Citation2003; Kabiru et al., Citation2012). Adapting from Kabiru and colleagues (Citation2012), ‘models of risk’ includes role models that promote health compromising behaviour (such as practicing unsafe sex or engaging in alcohol and drug misuse); opportunity risk entails exposure to situations which encourage risk behaviours (working in a bar, for example, where it is expected that additional income can be made from providing sex); and vulnerability risk includes individual factors which increase the chances of engaging in risk behaviour (being socially isolated, feeling worthless, or having no hope for the future). Protection operates at different levels. Models protection is conceptualised as including familial and peer role-models who promote prosocial behaviour. Controls protection includes protective factors operating at an individual-level (such as religious faith) or social environment level (such as monitoring by family, an older friend or trusted adult) which serve as regulatory controls. Support protection includes contextual support, such as peer networks or work colleagues, that promote pro-social, health enhancing behaviour and build protective social assets.

Our previous work in the region (Bernays et al., Citation2020) suggests that within the first year of arriving in a new place, young migrants’ lives were characterised by instability, transience and high ‘opportunity risk’ (i.e. exposure or access) due to the prevalence of substance use, unsafe coerced sex, crime and violence. Individual ‘vulnerability risk’ emerged (particularly among women), with a paucity of attainable options for young migrants with limited fiscal and social capital, in settings of entrenched socio-economic disadvantage and gendered employment opportunities. Many needed to rely on the income and resources that they could leverage through engaging in transactional sexual relationships (Bernays et al., Citation2020).

Young people in both locations considered that their exposure to HIV-risk was unavoidable but temporary, rendering harm-reduction services pertinent for ‘others’ but not them. They held firmly to identities characterised by individual agency and onward progress toward their real or imagined futures. This discordance between the presumed (higher) risks faced by others and the minimised risk that they faced personally remained unexamined by young people, or at least were presented as such in their accounts of their experience. The exceptionalism that they applied to themselves as individuals was justified by their aspirational pathways in which they anticipated being successful. These imagined futures were ones which they could not reconcile with having become HIV infected when young (Bernays et al., Citation2020).

Materials and methods

Study setting and recruitment

We undertook formative research in 2017–2018 with 78 young people (aged 16–24 years) in small towns in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa, and in Kalungu District, Uganda. We used qualitative research methods to gather data from young people who had recently moved to the area (approximately within the previous year). In both sites, many participants had lived in various places before arriving.

The South African research site was a small town in northern KwaZulu-Natal, an area where annual HIV incidence is 8% amongst women aged 20–24 and 4% in men aged 25–29 (Chimbindi et al., Citation2018). Most participants came from within KwaZulu-Natal province. uMkhanyakude District is one of the most deprived districts in South Africa with high rates of unemployment. There are limited resources such as water and electricity and few recreation activities for young people (Department of Health, Citation2018).

We conducted the same study in south-western Uganda, in Kalungu district. The young people involved in this study lived in Lukaya, a trading town on the highway leading from Uganda to Tanzania and Rwanda or in the surrounding more rural area in Kalungu District. The overall HIV-prevalence is 12.5% (Kiwuwa-Muyingo et al., Citation2020). The area has been a hub for the sale of produce from the rural areas, and from nearby fishing sites, for many years. Recently a rice farm and processing plant opened on the outskirts of the two, which employs several hundred young people as labourers.

Data collection

We investigated the experiences of young people who had moved to the towns from a rural setting through a series of data collection phases. Over a month we conducted a rapid participatory assessment of the study sites, holding informal discussions with both young and older people we encountered in the community, individually and in groups, to inform our approach to recruitment of young people (many of whom had recently moved into the area) and topic guides.

After this formative stage, we conducted in-depth interviews (IDIS) with 78 young people (n = 40, Ugandan site; n = 38 in the South African site). In both places, our recruitment strategy predominately involved approaching young people in the community. We then asked participants to subsequently introduce us to other young people within their social networks. In Uganda, the sample was evenly distributed across gender. In South Africa, where recruitment was more difficult, it was not feasible to pursue a purposive sampling approach. Instead, we relied on a convenience sampling approach in which we recruited anyone eligible and willing to participate. This meant that the South African sample had more women (n = 28) than men (n = 10).

In Uganda, we followed up 20 of these same young people (split evenly across genders) and in South Africa, only 11 participants (eight women and three men) participated in a second individual interview approximately six months later. Ideally, our tapered sample would have been shaped by emerging analytical interests, however, several of the participants in the original sample had left the sites and were no longer contactable. In South Africa, challenges with retention due to onward mobility were made more acute by the cohort’s reticence to engage with an organisation heavily associated with HIV research and service provision. These challenges were not encountered in Uganda. In both sites, availability and willingness to participate were the most influential factors in the constitution of the follow-up sample.

The focus of our research was to explore young people’s perceptions, experience and exposures associated with migration, and how this shapes HIV-risk behaviours. We investigated their experiences of HIV-risk, HIV-prevention and treatment-seeking behaviours, and patterns of drug and alcohol use. In both locations, the peri-urban environments of small trading centres in which the young people live are characterised by high availability of alcohol, high unemployment and few constructive social activities (Dlamini, Citation2017). Reflecting on their first year in their new settings, young men and women described the early influences on their heightened risk behaviour, including new friendships which provided access to sex and drugs; and often encouraged a lifestyle beyond their limited means. To elicit reflections on their experiences, in the interviews we asked questions such as: What brought you here? Have your plans changed since arriving? Do you know of any services that have been provided that you have thought have been really good for young people?

The final phase of data collection was conducted six months later. We invited all of the second phase interview participants who were still contactable and living in the study sites to participate in workshops. The purpose of these workshops was to discuss emerging findings and engage in co-design activities to develop an intervention model to address the concerns identified in the study. In Uganda, seven participants (five young men and two young women) attended the workshops and in South Africa five participants (two young men and three young women) attended. We sought to identify the young people’s needs as they interpreted them and incorporate their suggestions and comments on contextually appropriate opportunities for intervention. In this paper, we trace how the data from the participatory workshops underpin and interact with the theoretical framing to explain our subsequent intervention design. Extracts are presented anonymously. Individuals are identified by gender and country. If statements were articulated on behalf of the group in the workshops these are referred to as consensus statements.

Data analysis

We conducted a thematic analysis of our data, which began through discussions at weekly team meetings during data collection. This approach informed ongoing recruitment, sampling and the revision of topic guides and formed the basis of analytical memos in which emerging themes were identified and explored. To expedite the data management process, we summarised audio-recorded data into detailed interview scripts in English using a mixture of reported speech and verbatim quotes. Pertinent linguistic phrases, such as idioms, were written verbatim and then translated into English with attention paid to capture their equivalent meaning. The completeness of the scripts was tested by transcribing verbatim some of the interviews and comparing them with draft scripts for detail. Requiring a high degree of training and skill, this is an approach increasingly adopted to facilitate timely analytical attention to emerging data, which can be disrupted by delays in transcription and translation. More detailed descriptions of this process have been reported elsewhere (Bernays et al., Citation2018; Rutakumwa et al., Citation2020). Scripts were coded initially using an open-coding approach, then using a coding framework developed by SB and CL. Coded data were checked against themes identified in the team’s ongoing analytical discussions, which involved the above authors with the support of JS, ET, AA and VD. Emergent themes were corroborated between the analytical memos and the coding process using Word processing software by the above analysts (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1990). To ensure inter-rater reliability these were extensively discussed by the team to ensure accuracy of representation. These were developed into the key findings. The preliminary analysis from the in-depth interviews were presented to the participants within the participatory workshops for member checking. The design of the related intervention which emerged from the overall dataset were presented to youth in the community through subsequent local youth advisory meetings as part of preparations to implement the intervention.

Research ethics approvals were granted by the University of KwaZulu-Natal Biomedical Research Committee in South Africa (BE471/15), Uganda Virus Research Institute Research Ethics Committee/Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (SS4298), London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Ethics Committee (ref- 11259). Participants were approached and invited to take part in the study by the local research team and were asked to provide written consent. Following Uganda National Council for Research and Technology guidance on Human Subjects Research (https://www.uncst.go.ug/guidelines-and-forms/), participants aged 16–17 living independently and providing for themselves financially were considered emancipated minors and able to give their own consent without requiring guardian approval. In South Africa where such exemption is not allowed for, guardian consent was necessary for participants aged 16–17 years old, alongside the adolescents’ assent.

Results

.

Table 1. Study participants by phase of data collection.

Addressing ‘our’ needs; enhancing ‘protective factors’

Informed by the preliminary findings of the interview data the young people identified four key features of a potential intervention. The intervention would be open to all young people who have migrated, giving particular attention to new migrants (within six months of resettlement) and would:

Establish a small peer supporter network. The peer supporters would provide advice and support over the telephone to young migrants.

Offer a drop-in centre or hub (a small rented shop or similar) staffed by a peer supporter during the day, early evenings and weekends, to provide information and onward referral to local health and social services, free condoms, access to a counsellor and/or nurse for advice and the use of a computer and a printer (for letters and job applications).

Identify local champions to enable a more supportive local environment for young migrants.

Ensure that the intervention remains available over time and when they are moving in and out of the area.

We present, in further detail, the rationale behind these four elements from the participatory workshops.

Local peer supporters’ network

Not knowing who to trust or where to turn upon first arriving in a new place was a common feature of the experience of youth mobility. Many participants described how necessity demanded that they rely heavily on casual or recent social contacts, which tended to deepen individual vulnerabilities through cynical exploitation or leading to risky lifestyle ‘choices’. Young people emphasised how much they needed someone they could trust to give them local advice to help them navigate their new place and to be able to facilitate their access to healthcare services. They considered that peers, who had recently been in similar situations would be well placed to fulfil this role, as ‘someone who has already had an experience of life here’ (Young woman, South Africa). They wanted these peers to offer individual counselling and support over the phone and be a point of contact for relevant advice and reliable information. They envisaged that these young people would provide ‘models protection’ as peer role-models, champions and enablers of prosocial behaviours.

To the young people, this approach had two distinct advantages. The first was that the reasonable availability of, even reliance on, mobile phones meant that such support could be accessible and available to young people: ‘you tell them that here is this mobile number, when you have got this kind of a problem or when there is something you want to enquire about this issue, you can call on it, it will help you’ (Young woman, Uganda). It also provided a degree of connectedness with a peer and protection from being socially recognised by having to physically access a service. The virtual connection enabled by the phone service would mean that it could continue to be accessible even if the young person moved in and out of the area as they moved to follow short-term employment opportunities: ‘I would like that maybe I can be called (on his mobile phone) because I am a person who doesn’t stay here a lot of time’ (Young man, South Africa).

Secondly, they considered that young people of a similar age who had the experience of being in similar situations, had received training and were well-informed, would be more approachable and their advice more credible and influential than that offered by adults. Young people articulated a desire to feel connected to someone, whose circumstances were relatively similar to their own, who they deemed trustworthy to provide information and support. ‘You find that I see the issue, but I am not sure where I will report it. If I inform the peer, they can be the one to find help’ (Young man, South Africa).

Very few participants had previously engaged with existing health services, in part because they considered that the adults providing counselling, who were of a different generation, were not able to connect with or understand the nature of the issues they encountered.

The participants considered that the relative evenness in age and experience between the peer supporters and beneficiaries would enable a candour that did not tend to feature in their interactions within standard health services, which was hampered by the generation divide.

When I talk to them (peer supporter) I would not conceal my experience and be trying to cover them and show only what is outside. If you are to talk to her, you have to tell the truth and show her what it is. I can trust her and say; ‘let me also do it like that, if that is what you have told me’. (Young woman, Uganda)

In addition to being able to draw on their life experiences, an important benefit of engaging with peer supporters/navigators would be timely linkage of newly arrived migrants with relevant local health and support services.

When you are chatting […] you can share with her (a peer supporter) about many different things […] and then she can tell you whether you are correct. I can go with her to find out more from them. I can even then talk to her about other things and she can also help me with these things. This is what someone like that could do for me. (Young woman, Uganda)

The young people anticipated that a critical element of success rested on the provision of training and ongoing support to the peer supporters. This was proposed as a necessary component to elevate peers from being seen as well-intentioned but unskilled, to being in a position to effectively and confidently fulfil their roles and for their value to be credible to young people. This was an indication that the intervention would need to provide structural support (training, stipends, technology) to peer-supporters to help realise the experience of togetherness and connectedness that could be generated through these specific social interactions between young people. Creating this supportive edifice, through the development of a cohesive peer support network which is underpinned by effective training, supervision and remuneration, was considered a pivotal component to nurture solidarity and potentially resilience among youth on the move.

First train us then we shall counsel them (young people) because we are always with them. If I am trained well and I am supported I can help other young people. (Young man, Uganda)

Additionally, the young people cited the need for the service to be connected to and endorsed by a respected local health care service-provider. This would both confer credibility onto the peer supporters and enable the peer supporters to facilitate referrals for young people as needed. By extension, peer supporters were characterised as being uniquely positioned to play a facilitation role in linking young people to services that would otherwise have been dismissed by young people as irrelevant or inaccessible. In this way, the intervention could offer a collaborative link between young people ordinarily disenfranchised from existing health services.

‘Drop-in’ resource centre

Although participants emphasised the advantages of offering support through phone calls and messages, they still wanted the service to have a physical ‘drop-in’ centre where young people could come to receive counselling and advice, as well as access to practical resources, including condoms, as well as printing and computer services. Reliable, free access to these resources was emphasised as being an attractive feature and anticipated ‘hook’ for attendance at the drop-in centre, due to ongoing difficulties accessing these desired resources elsewhere (including suitable condoms products). Once present at the centre, engagement with peer supporters could be initiated. The proposed ‘drop-in’ centre may thus constitute a safe space and a centralised source of ‘support protection’ by providing contextual support for the development of protective individual and social assets, as well as improved financial literacy.

Another reason for having a physical hub was so that young people could access practical support and information to pursue locally available training and employment opportunities. The paucity of employment opportunities was considered to drive young people’s exposure to risk, and few had access to necessary information or means to identify relevant opportunities. Being able to practise effective HIV prevention was intimately connected to already having the security of economic opportunities. This structural relationship was alluded to by workshop participants: ‘help create jobs for the youth so that they don’t spend time doing wrong things because they have nothing to do’ (Consensus statement in workshop, South Africa).

This drop-in service needed to be available to young people at times that were convenient to them. For many young people, the limited hours of operation and long waiting times at clinics was off-putting. Instead, they wanted a service that was open in the evenings or some weekends.

There should be a service like this one of yours where you find us, because I will be at work where I know that l leave late, I will not get time to go to the health facility. (Young man, Uganda)

Local adult community champions

Two further components were identified as being integral to the success of the intervention: local adult community champions and facilitating sustained support over time. Young people considered that the intervention should be supported by influential adult stakeholders within the community who could provide young migrants with employment opportunities and apprenticeships. Community champions may further convey ‘controls protection’ through the provision of trusted adult mentoring, serving as a regulatory control mechanism in the (relatively recent) absence of close parental supervision and support.

Absence of a supportive parenting framework for many of the young migrants, after leaving home, was cited as a risk-factor for engagement in risk-associated activities; ‘Some young people were not nurtured by their parents, they grew up on their own and learnt all sorts of bad behaviours’ (Young man, Uganda). There were multiple instances in which young people’s accounts demonstrated that there was an evident absence of prosocial adult role models, and feasible professional pathways, with which the young migrants may identify and aspire. The silence in their accounts demonstrated the dearth of experience they had had of positive role models. Inversely, they were vocal in their enthusiasm to connect and engage with new, potentially trustworthy adults in the community setting: ‘There is an individual who does not give a chance to their parents to counsel them, but might listen to other people’ (Young woman workshop participant, Uganda). For a young migrant who has left home, and those without a close parental connection, employers, educators and trusted stakeholders in the new community with whom they have contact have the potential to provide instrumental guidance and practical support.

Facilitating sustained support and change over time

As exposure to the various risk factors is anticipated to persist over time, the second essential component was a need for temporal and geographical sustainability of the intervention (such as availability of ongoing support remotely by phone). The participants explained the intervention would take time to develop and to influence young people’s lives, and support would need to be consistent and sustained over time to overcome existing barriers to change. They explained the relevance of this characteristic to establish local credibility.

When they know that you are right, they will come and those who come will bring others, twenty will bring another twenty because they have now known you. At the start they do not trust you, there is nothing that starts big, it starts small but gains pace. (Young man, Uganda)

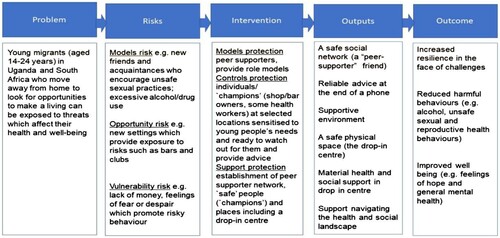

Applying the theory of change

These findings were used to inform the intervention design, which was developed using our applied ‘Theory of Change’ (ToC) model (). The ToC emphasises concepts of protection-risk and resilience among adolescents (Bolzan & Gale, Citation2012; Bottrell, Citation2009; Cote & Nightingale, Citation2012); to enhance protective factors through harm reduction interventions in order to moderate the impact of context-specific risks, and to encourage increased resilience as an outcome (Olsson et al., Citation2003). We theorise that supporting individual migrants’ abilities to manage and adapt to their new places of settlement through engagement with the components of our intervention (positive role models, pro-social friendship networks, safer environment, and local health and social supports) may afford protection. This is intended to support young migrants to resist and overcome potentially detrimental effects of risk exposure (Fergus & Zimmerman, Citation2005) with tangible impacts on health (including safer sexual and reproductive health behaviours), wellbeing (such as retaining hope), and thereby future developmental trajectories.

Discussion

We designed an empirically based and theoretically informed combination HIV-prevention intervention tailored to young migrant populations in SSA, in collaboration with young people from within the target population group. These young people were our partners in designing an intervention, through the participatory workshops, to address this risk-imbued context. They emphasised the specific, practical support needs of this transient population, including the provision of relevant information and skill-development to support their nominated priorities of gaining employment and further education. They also highlighted the need to focus on broader conceptualisation of their identities by placing the emphasis on their aspirations as well as their vulnerabilities. They argued that these were crucial elements if the target population were to engage in relevant harm-reduction and health services. Notably, affiliation with HIV-specific services was viewed as undesirable due to the potentially stigmatising nature of such interactions.

Three additional lessons emerge from the applied learning process of collaborative intervention design. The first relates to the necessity of investing time in formative research to be able to find, engage, and enable partnerships to develop with mobile youth in Uganda and South Africa (Jumbam, Citation2020). Young migrants in SSA have typically been regarded as ‘hard to reach’ by researchers and clinicians alike (Vearey, Citation2018). However, as demonstrated by our early formative research, and by the work of Corbie-Smith and colleagues among rural African American communities characterised by entrenched HIV-risk in the Southeast United States (Corbie-Smith et al., Citation2011), careful attention to process and partnership development can result in effective collaboration and improved HIV-prevention outcomes. We suggest that labelling people as ‘hard to reach’ is a misnomer. Rather it indicates that the methods conventionally utilised to engage them are not suitable. The intervention design developed with the young people provides a positive example of how we may ‘reach’ young migrants populations in SSA; with significant implications for public health and the broader adolescent HIV response. However, it is important to note that prior to implementing the intervention, while our design anticipates that we ‘reach’ more young people, its outcomes and effectiveness are still unknown so young people may remain ‘hard to reach’ or underserved.

Secondly, we have shown how understanding nuances of local context is vital to developing interventions which appeal to target population groups. Young people were involved in the study and process of designing the intervention because they were young migrants, who were considered in epidemiological terms to be at high risk of acquiring HIV through their economic precarity and social networks. In contrast though, young people emphasised how being characterised as acutely ‘at risk’ did not readily resonate with their perceptions of self, and so an emphasis on their aspirations, rather than one more singularly focused on their vulnerability, aligned better with their perspectives on their own lives. Their own priorities rarely neatly converged with national epidemiological concerns. Rather, in both locations, we observed a reticence to engage with closely HIV-affiliated organisations and services due to the potentially stigmatising nature of such interactions, limiting their utility. Reducing rates of HIV acquisition among this group was not considered to be as pressing a concern as economic stability through improved and sustained access to education, employment and income. For many young people, the narrative of aspiration and momentum was pivotal to how they saw themselves, and so interventions instead need to offer opportunities to enhance their ambitions. In addition, circling local discourses promoting xenophobia and suspicion of newcomers and migrants highlights the need for interventions to be framed in ways that are attuned to concerns about promoting services for ‘migrants’ and mobile youth (Bernays et al., Citation2020; Vearey, Citation2018). As we observed when trying to increase engagement in our own research, there are risks to engagement if we place too narrow an emphasis on seeking out ‘migrants’ specifically, or by marketing services as exclusively for the provision of HIV-care (Bernays et al., Citation2020).

Attending to their concerns enabled us to develop a contextually appropriate interventions, which are aligned with their priorities. However, this did not necessarily mean that there was divergence in design across the sites. For example, although there is variation between mobile phone ownership between the two sites in reality the higher phone ownership in Northern KZN may lead to an over-estimation of access to being able to easily use mobile phones. In both sites, young people struggle to afford airtime and also with uneven and intermittent reception, even with access to a phone it would not necessarily work (Cele & Archary, Citation2019; Kreniske et al., Citation2021; Wanyama et al., Citation2018). To be able to maximise the value of phone-based peer-support additional investment in improving the infrastructure and supporting costs of engagement is critical (Cele & Archary, Citation2019; Kreniske et al., Citation2021). But it also illustrates the value in listening to young people’s need for a ‘drop-in’ centre which can serve as a physical hub. Our intervention design was predicated on a hybrid approach to support young migrants’ connection to services and peer support, reflecting our locally embedded response and design.

Young people emphasised the need to allow young people to develop trust in the intervention over time. This included offering them support with employment opportunities through the ‘drop-in’ centre, as well as connecting them with trustworthy adults in the community. Enabling young people to engage with the intervention over time, including if they moved out of the area, was a core tenet and suggests that the pathways to promote changes in behaviour to produce sustained harm reduction may need to involve offering sustained support (Mavhu et al., Citation2020).

The third lesson, which underpins the intervention design, is the potentially transformative effect of the solidarity that can emerge through peer support engendering resilience among youth on the move. For the young people, their social networks and opportunities to access peer support were potentially vital resources to enable them to reduce their risky behaviour, identifying their peers if adequately trained and supported, as having a harm reduction influence. Young people placed considerable emphasis on the value in feeling connected to others with similar experiences through whom they can access trustworthy information and support. This has translated in our intervention into peer supporters who will have to access training, stipends and resources, such as phones and mobile data, to develop a social network of young people through sharing virtual and physical safe spaces (Falb et al., Citation2016). The logic of the intervention anticipates that the experience of togetherness may evolve into supportive solidarity. Incrementally, this may, in turn, provide collective pathways, in collaboration with local adult champions, to realise a more empowered environment for young people to challenge the structural conditions, including intergenerational power dynamics, which currently shape and heighten their health risks (Blanchard et al., Citation2013). Although subject to increasing attention, there has been a little empirical investigation into the mechanisms of impact of peer support for improving young people’s HIV prevention and treatment outcomes (Grimsrud et al., Citation2020). The nascent evidence-case indicates the significance of ‘connectedness’ and the importance of the provision of adequate resourcing for training and supervising peer supporters to sustain the potential considerable gains (Mavhu et al., Citation2020; Shahmanesh et al., Citation2020; Wogrin et al., Citation2021).

The strengths of this study relate to the time invested in collaborating with young people from the intervention communities in order to develop an understanding of their concerns and then co-design an intervention which can attend to their needs, employing contextually appropriate approaches. However, to maintain an ongoing dialogue with groups of young people in both sites meant that we collaborated with a relatively small group and so may have been influenced by a narrow group of concerns, which may have limited conceptual generalisability.

The intervention has since been funded, and we are in the early stages of implementation. We will seek to deliver this intervention as widely as possible within these communities, which will enable us to test the feasibility and appropriateness of our design. In alignment with best-practice recommendations for youth engagement in implementation science research, young migrants will continue to fulfil leadership roles during project implementation as peer-supporters/navigators and will be asked provide feedback in a variety of forms for contribution to project evaluation.

Conclusion

Through intentional engagement of young migrants throughout project development, we have sought to avoid over-simplification of the complexities which contribute to the perpetuation of vulnerability among young migrants and instead have focused on the emphasis that they place on their nominated priorities. We intend for this case study to highlight the value of participatory approaches using qualitative methods for exploring the dynamic concerns of a target population, to inform the development of community-based and theory-driven interventions to reduce risk and promote well-being and resilience among this population.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all the participants who contributed their time and effort to the study. We thank Sthembile Ngema, Xolani Ngwenya and Dumile Gumede for their contribution to the study. We are very grateful for the support of the community members where we work in carrying out our research and we thank the wider Africa Health Research Institute and MRC/ UVRI and LSHTM Uganda Research Unit teams for their contributions to our work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barratt, C., Mbonye, M., & Seeley, J. (2012). Between town and country: Shifting identity and migrant youth in Uganda. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 50(2), 201–223. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X1200002X

- Bernays, S., Bukenya, D., Thompason, C., Ssembajja, F., & Seeley, J. (2018). Being an ‘adolescent’: The consequences of gendered risks for young people in rural Uganda. Childhood, 25(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568217732119

- Bernays, S., Lanyon, C., Dlamini, V., Ngwenya, N., & Seeley, J. (2020). Being young and on the move in South Africa: How ‘waithood’ disrupts the success of current HIV prevention interventions. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 15(4), 368–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450128.2020.1739359

- Blanchard, A. K., Mohan, H. L., Shahmanesh, M., Prakash, R., Isac, S., Ramesh, B. M., & Blanchard, J. F. (2013). Community mobilization, empowerment and HIV prevention among female sex workers in south India. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 234. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-234

- Bolzan, N., & Gale, F. (2012). Using an interrupted space to explore social resilience with marginalised young people. Qualitative Social Work, 11(5), 502–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325011403959

- Bond, V., Chiiya, C., Chonta, M., & Clay, S. (2011). Sweeping the bedroom: Children in domestic work in Zambia.

- Bottrell, D. (2009). Understanding ‘marginal’ perspectives: Towards a social theory of resilience. Qualitative Social Work, 8(3), 321–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325009337840

- Breuer, E., Lee, L., De Silva, M., & Lund, C. (2016). Using theory of change to design and evaluate public health interventions: A systematic review. Implementation Science, 11(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0422-6

- Camlin, C. S., Hosegood, V., Newell, M. L., McGrath, N., Bärnighausen, T., & Snow, R. C. (2010). Gender, migration and HIV in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. PLoS One, 5(7), e11539. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0011539

- Cele, M. A., & Archary, M. (2019). Acceptability of short text messages to support treatment adherence among adolescents living with HIV in a rural and urban clinic in KwaZulu-Natal. Southern African Journal of HIV Medicine, 20(1), 1–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajhivmed.v20i1.976

- Chimbindi, N., Mthiyane, N., Birdthistle, I., Floyd, S., McGrath, N., Pillay, D., & Shahmanesh, M. (2018). Persistently high incidence of HIV and poor service uptake in adolescent girls and young women in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa prior to DREAMS. PLoS One, 13(10), e0203193. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203193

- Coffee, M. P., Garnett, G. P., Mlilo, M., Voeten, H. A., Chandiwana, S., & Gregson, S. (2005). Patterns of movement and risk of HIV infection in rural Zimbabwe. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 191(Supplement_1), S159–S167.

- Corbie-Smith, G., Adimora, A. A., Youmans, S., Muhammad, M., Blumenthal, C., Ellison, A., & Lloyd, S. W. (2011). Project GRACE: A staged approach to development of a community-academic partnership to address HIV in rural African American communities. Health Promotion Practice, 12(2), 293–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839909348766

- Cote, M., & Nightingale, A. J. (2012). Resilience thinking meets social theory: Situating social change in socio-ecological systems (SES) research. Progress in Human Geography, 36(4), 475–489. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132511425708

- Coughlin, S. S. (2016). Community-based participatory research studies on HIV/AIDS prevention, 2005–2014. Jacobs Journal of Community Medicine, 2(1), 019.

- Department of Health. (2018). uMkhanyakude district health plan 2018/19–2020/21.

- De Silva, M., Breuer, E., Lee, L., Asher, L., Chowdhary, N., Lund, C., & Patel, V. (2014). Theory of change: A theory-driven approach to enhance the Medical Research Council’s framework for complex interventions. Trials, 15(1), 267. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-15-267

- Dlamini, V. (2017, 13th-15th November). The social environment of young people in rural northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. 13th AIDS Impact Conference Cape Town.

- Erulkar, A. S., Mekbib, T. A., Simie, N., & Gulema, T. (2006). Migration and vulnerability among adolescents in slum areas of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Journal of Youth Studies, 9(3), 361–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260600805697

- Falb, K. L., Tanner, S., Ward, L., Erksine, D., Noble, E., Assazenew, A., & Neiman, A. (2016). Creating opportunities through mentorship, parental involvement, and safe spaces (COMPASS) program: Multi-country study protocol to protect girls from violence in humanitarian settings. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 1–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2894-3

- Fergus, S., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2005). Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health, 26(1), 399–419. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357

- Grimsrud, A. T., Pike, C., & Bekker, L. G. (2020). The power of peers and community in the continuum of HIV care. The Lancet Global Health, 8(2), e167–e168. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30544-3

- Hardee, K., Gay, J., Croce-Galis, M., & Afari-Duamena, N. A. (2014). What HIV programs work for adolescent girls? Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 66(Suppl. 2), S176–S185. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000182

- Jessor, R. (1991). Risk behaviour in adolescence: A psychosocial framework for understanding and action. Journal of Adolescent Health, 12(8), 597–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/1054-139X(91)90007-K

- Jessor, R., Turbin, M., Costa, F., Dong, Q., Zhang, H., & Wang, C. (2003). Adolescent problem behavior in China and the United States: A cross-national study of psychosocial protective factors. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 13(3), 329–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/1532-7795.1303004

- Jochelson K., & Leger, J. P. (1991). Human immunodeficiency virus and migrant labor in South Africa. International Journal of Health Services, 21(1), 157–173. https://doi.org/10.2190/11UE-L88J-46HN-HR0K

- Jones, G. (2016). Migration, young people and vulnerability in the urban slum. Switzerland Springer Nature.

- Jumbam, D. T. (2020). How (not) to write about global health. BMJ Global Health, 5(7), e003164. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003164

- Kabiru, C., Beguy, D., Ndugwa, R., Zulu, E., & Jessor, R. (2012). “Making it”: Understanding adolescent resilience in two informal settlements (slums) in Nairobi, Kenya. Child and Youth Services, 33(1), 12–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2012.665321

- Kiwuwa-Muyingo, S., Abongomera, G., Mambule, I., Senjovu, D., Katabira, E., Kityo, C., & Seeley, J. (2020). Lessons for test and treat in an antiretroviral programme after decentralisation in Uganda: A retrospective analysis of outcomes in public healthcare facilities within the Lablite project. International Health, 12(5), 429–443. https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihz090

- Kreniske, P., Basmajian, A., Nakyanjo, N., Ddaaki, W., Isabirye, D., Ssekyewa, C., & Chang, L. W. (2021). The promise and peril of mobile phones for youth in rural Uganda: Multimethod study of implications for health and HIV. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(2), e17837. https://doi.org/10.2196/17837

- Marukutira, T., Yin, D., Cressman, L., Kariuki, R., Malone, B., Spelman, T., & Dickinson, D. (2019). Clinical outcomes of a cohort of migrants and citizens living with human immunodeficiency virus in Botswana: Implications for Joint United Nation Program on HIV and AIDS 90-90-90 targets. Medicine, 98(23), e15994. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000015994

- Mavhu, W., Willis, N., Mufuka, J., Bernays, S., Tshuma, M., Mangenah, C., & Cowan, F. M. (2020). Effect of a differentiated service delivery model on virological failure in adolescents with HIV in Zimbabwe (Zvandiri): a cluster-randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Global Health, 8(2), e264–e275. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30526-1

- Olawore, O., Tobian, A. A. R., Kagaayi, J., Bazaale, J. M., Nantume, B., Kigozi, G., & Grabowski, M. K. (2018). Migration and risk of HIV acquisition in Rakai, Uganda: A population-based cohort study. The Lancet, 5(4), e181–e189. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(18)30009-2

- Olsson, C., Bond, L., Burns, J., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Sawyer, S. (2003). Adolescent resilience: A concept analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 26(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-1971(02)00118-5

- Operario, D., Underhill, K., Chuong, C., & Cluver, L. (2011). HIV infection and sexual risk behaviour among youth who have experienced orphanhood: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 14(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/1758-2652-14-25

- Punch, S. (2015). Youth transitions and migration: Negotiated and constrained interdependencies within and across generations. Journal of Youth Studies, 18(2), 262–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2014.944118

- Richter, L., Mathews, S., Kagura, J., & Nonterah, E. (2018). A longitudinal perspective on violence in the lives of South African children from the birth to twenty plus cohort study in Johannesburg-Soweto. South African Medical Journal, 108(3), 181–186. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2018.v108i3.12661

- Rutakumwa, R., Mugisha, J. O., Bernays, S., Kabunga, E., Tumwekwase, G., Mbonye, M., & Seeley, J. (2020). Conducting in-depth interviews with and without voice recorders: A comparative analysis. Qualitative Research, 20(5), 565–581. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794119884806

- Schuyler, A. C., Edelstein, Z. R., Mathur, S., Sekasanvu, J., Nalugoda, F., Gray, R., … & Santelli, J. S. (2017). Mobility among youth in Rakai, Uganda: Trends, characteristics, and associations with behavioural risk factors for HIV. Global Public Health, 12(8), 1033–1050. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2015.1074715

- Seeley, J., Tumwekwase, G., & Grosskurth, H. (2009). Fishing for a living but catching HIV: AIDS and changing patterns of the organization of work in fisheries in Uganda. Anthropology of Work Review, 30(2), 66–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1417.2009.01022.x

- Shahmanesh, M., Okesola, N., Chimbindi, N., Zuma, T., Mdluli, S., Mthiyane, N., & Harling, G. (2020). Thetha Nami: Participatory development of a peer-navigator intervention to deliver biosocial HIV prevention for adolescents and young men and women in rural South Africa. https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-42209/v1.

- stats sa. (2019). SA population reaches 58,8 million. http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=12362.

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Sage Publications.

- Tutu, R. (2013). Exploring social resilience among young migrants in Old Fadama, an Accra Slum. Springer.

- Uganda, U. (2017). Uganda’s youthful population: Quick facts. https://uganda.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/YoungPeople_FactSheet%20%2811%29_0.pdf.

- UNAIDS. (2020). Eastern and Southern Africa. http://rstesa.unaids.org/.

- van Breda, A., & Theron, L. (2010). A critical review of studies of South African youth resilience, 1990–2008. South African Journal of Science, 106(7-8), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajs.v106i7/8.252

- van Breda, A., & Theron, L. (2018). A critical review of South African child and youth resilience studies, 2009–2017. Child and Youth Services Review, 91, 237–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.06.022

- Vearey, J. (2018). Moving forward: Why responding to migration, mobility and HIV in South(ern) Africa is a public health priority. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 21(Suppl. 4), e25137. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25137

- Wanyama, J. N., Nabaggala, S. M., Kiragga, A., Owarwo, N. C., Seera, M., Nakiyingi, W., & Ratanshi, R. (2018). High mobile phone ownership but low internet access and use among young adults attending an urban HIV clinic in Uganda. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 13(3), 207–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450128.2017.1418037

- Wogrin, C., Willis, N., Mutsinze, A., Chinoda, S., Verhey, R., Chibanda, D., & Bernays, S. (2021). It helps to talk: A guiding framework (TRUST) for peer support in delivering mental health care for adoelscents living with HIV. PLOS One, 16(3), e0248018. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248018