ABSTRACT

Addressing the politics of corporate political activity and policy interference in response to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) is a new area of scholarly research. The objective of this article is to explain how, in Mexico and Brazil, the ultra-processed foods and beverages industry succeeded in creating the political and social conditions conducive for their on-going regulatory policy influence and manipulation of scientific research. In addition to establishing partnerships within and outside of government, industry representatives have succeeded in hampering civic opposition by establishing allies within academia and society. Ministries of Health have simultaneously neglected to work closely with civil society, while legislative representatives have continued to benefit from industry campaign contributions. Findings from this article suggest that ultra-processed foods and beverages industries wield on-going regulatory policy influence in Mexico and Brazil, and that government is still not fully committed to working with civil society on these issues.

Introduction

In response to the rise of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), recently several upper-middle-income countries have successfully introduced a myriad of public health prevention programmes, i.e. policies focused on individual interests, motivations, and behaviours, that help to monitor and reduce NCDs, such as obesity, type-2 diabetes, stroke, and cancer (Checkley et al., Citation2014; Verstraeten et al., Citation2012). A new area of global public health research focuses on understanding how ultra-processed foods and beverages industries in these countries continue to hamper the creation of public health regulatory policies, i.e. efforts to circumvent industry’s activities and profit strategies, such as limiting the marketing and sale of their products, while distorting scientific research on the efficacy of these policies (Burlandy et al., Citation2020; Carriedo et al., Citation2021; Mialon et al., Citation2020a; Ojeda et al., Citation2020). Even more puzzling is how industry’s ongoing distortion of regulatory policy has occurred in a context of increased government commitment to introducing innovative national NCD prevention programmes focused on individuals, such as a soda tax, nutritional programmes, and public awareness campaigns (Jaime et al., Citation2013; James et al., Citation2020; Zhang & Ma, Citation2018). As a general observation, this disparity in policy priorities – prevention versus regulation – suggests that governments are often more willing to prioritise NCD prevention programmes targeting individuals rather than pursuing policies that directly threaten the activities of industries. NCD prevention programmes often emphasise, among other factors, addressing individual behaviours by providing nutritional information and education while discouraging consumption through food taxes (Budreviciute et al., Citation2020; Mendis, Citation2010). Alternatively, regulatory policy approaches to reducing NCDs often appear to focus on, among other factors (e.g. improving the physical environment, nutritious food subsidies), industries’ economic activities, such as regulating the sale and marketing of products, taxation, food reformulation, while establishing effective laws and leadership (Kaldor et al., Citation2018; Magnusson et al., Citation2018). These regulatory efforts are often necessary because it is not in the interests of industries to engage in voluntary regulatory practices (Magnusson et al., Citation2018) – though some may contend that it is, especially when viewed from a corporate social responsibility approach (Vogel, Citation2008), although these measures are often ineffective. When comparing NCD prevention versus regulation, however, it is not clear that governments often pursue both policies simultaneously, preferring instead to pursue prevention programmes due, perhaps, to their lower levels of industry contestation (Gortmaker et al., Citation2012), lower political costs, i.e. industry opposition to regulation, highlighted as a chief policy obstacle for governments (Swinburn, Citation2008). The author of this article, therefore, agrees with others claiming that emphasising prevention policies alone without an equal commitment to regulation hampers a government’s ability to create a healthier environment and diets for its citizens (Greenhalgh, Citation2019).

This article builds upon a growing body of literature that addresses the politics of ultra-processed foods and beverages industries interfering with NCD prevention and regulatory policy within upper- and middle-income countries (Fooks et al., Citation2019; Jaichuen et al., Citation2018; Tangcharoensathien et al., Citation2019). While research on industry interference has a longer history in the United States and Western Europe, especially with respect to the tobacco and alcohol industries, recently scholars have explored the various political and policy tactics that these industries have pursued in these countries to manipulate policy in their favour (Jaichuen et al., Citation2018; Mialon et al., Citation2016). This literature is emblematic of a larger field of study, Corporate Political Activity (CPA), which critically examines corporation’s efforts to influence government policy in ways that favour corporate interests (Hillman et al., Citation2004). Beginning with an examination of the tobacco industry, the CPA literature has underscored the various political tactics used by industries to influence NCD policy (Hillman & Hitt, Citation1999; Savell et al., Citation2014).

This article applies and builds upon the CPA literature by comparing and analysing the politics of how ultra-processed foods and beverages industries interfere in the policymaking process in Mexico and Brazil. In alignment with this literature, the author’s findings suggest that these industries in these countries have been successful in obstructing the creation of government policies targeting industry’s ability to increase the marketing and sale of their products while manipulating scientific policy research. These two policy outcomes appear to be attributed to several factors. First, and building on Hillman and Hitt’s (Citation1999) and Savell et al. (Citation2014) concepts of industry’s information and constituency-building interference tactics, industry can succeed in building policy partnerships within the bureaucracy, often through the creation and joint sponsorship of innovative NCD prevention programmes, building on long-standing partnerships with senior health officials, while establishing new partnerships with poor communities through the provision of employment programmes. However, the author goes further than the CPA literature by claiming that constituency-building activities can create divisions within society, in turn limiting its ability to mobilise in opposition to industry policy interference. Second, and illustrating Hillman and Hitt (Citation1999) and Savell et al., (Citation2014) discussion of industry’s financial incentives tactics, in Mexico and Brazil industry’s policy influence has been facilitated through the provision of largesse to legislative representatives, mainly by way of electoral campaign contributions. And finally, the author underscores yet another important factor: the health bureaucracy’s historic unwillingness to listen to and work closely with civil society in the area of NCD prevention and industry regulation, in turn revealing government preferences to selectively work with civil society on health policy issues.

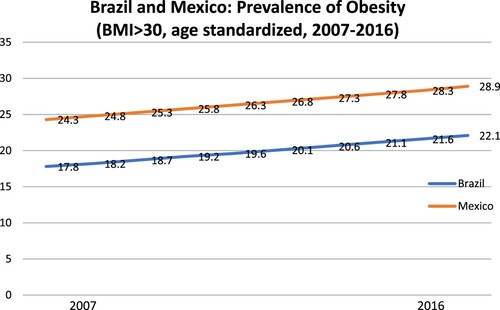

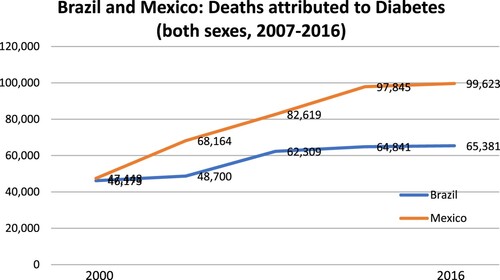

The Mexico and Brazil case studies were chosen because they have arguably the highest number of obesity and type-2 diabetes cases in Latin America (Gallardo-Rincón et al., Citation2021), share similar levels of poverty (though slightly higher in Mexico due to different welfare policy strategies) and inequality (Troyano & Martín, Citation2017), and have decentralised healthcare systems with sub-national governments playing an increasingly important role in health financing, policy-making, and administration (Collins et al., Citation2000; Fritscher & Zamora, Citation2016). The purpose of the author’s comparative analysis was two-fold: first, to underscore the historical and contemporary uniqueness (i.e. their unique institutional designs, government-industry relationships, and NCD policies) of the Mexican and Brazilian case studies, thus employing an idiographic approach, where the goal is to obtain new data and insights that can generate hypotheses to be evaluated by future studies (Bennett, Citation2012); and second, to evaluate the CPA literature with qualitative case studies (Levy, Citation2008). Because these case studies did not illustrate differences on the primary outcomes of concern, i.e. industry interference in NCD policy-making (present in both cases), and because there were only two cases studies examined, the goal was not to establish a new theory about corporate political activity and policy regulation in upper-middle-income countries.

Materials and methods

The author conducted a comparative qualitative case study comparison of Mexico and Brazil. The research for this article took place from 2018 to 2020. The author of this study reads and speaks Spanish and Portuguese fluently, has lived and worked in Mexico and Brazil, and has several years of experience conducting research in these countries.

This study also relied on the usage of qualitative data sources. Qualitative primary data sources from Mexico and Brazil included journal articles, books, policy reports, and news articles in the Spanish and Portuguese languages from these countries. This study also used secondary qualitative data, such as articles, books, and news reports written in English. These qualitative sources were obtained from Google’s on-line search engine through the usage of specific keyword search terms in the English, Spanish, and Portuguese languages. In the Results section of this paper, the author’s case studies relied on the usage of both primary and secondary qualitative data. In accordance with a comparative historical approach to political and social analysis, the Results section provided an in-depth informative description of events in Mexico and Brazil. For each of the case studies in this section, information was obtained from these qualitative sources on the roles and influence of industry representative associations, such as ABIR (Associação Brasileira das Indústrias de Refrigerantes), ABIA (Associação Brasileira da Indústrias de Alimentos) SBAN (Sociedade Brasileira de Alimentação e Nutrição), and specific corporations, such as Nestlé in Brazil; and in Mexico, information was obtained on foundations aligned with industries, such as ConMéxico, FunSalud, and the Coca-Cola and PepsiCo corporations. Quantitative data on obesity and diabetes prevalence and deaths were obtained from the WHO, Global Health Observatory data repository, and was used to compare epidemiological trends in Mexico and Brazil ( and ).

Results

Revisiting the literature: The politics of industry NCD policy interference

Public health researchers have recently underscored the political strategies that industries pursue to influence NCD policy in their favour. Often referred to as the Corporate Political Activity (CPA) literature, the seminal contributions of Hillman and Hitt (Citation1999), for example, highlighted the political tactics that industries used to influence policy, such as information strategy, which includes industry lobbying and providing information to policy-makers; constituency-building, i.e. industry partnering with communities on policy initiatives (Hillman & Hitt, Citation1999); and financial incentives, a process that financially targets politicians directly (Hillman & Hitt, Citation1999). Savell et al., (Citation2014) subsequently adopted these strategies and introduced alternative ones, such as information, which focuses on lobbying, providing and manipulating empirical evidence, and partnering with government through working groups and advice; legal, that is, industry’s threat of legal action towards market competitors (Savell et al., Citation2014); policy-substitution, e.g. proposed industry self-regulation (Savell et al., Citation2014); opposition/fragmentation, e.g. industry criticisms of industry competitors in the media (Savell et al., Citation2014); and financial incentives, such as industry’s provision of bribes/largesse (Savell et al., Citation2014). Savell et al., (Citation2014) also went beyond Hillman and Hitt (Citation1999) to provide several discursive frames used by industry to justify and defend their policy position, such as the negative unintended consequences of policy, regulatory redundancy and insufficient evidence. Recent studies have not only built upon Hillman and Hitt’s (Citation1999) and Savell et al., (Citation2014) analytical frameworks but have also underscored several other corporate political tactics and their NCD policy influence (Lima & Galea, Citation2018; Mialon & Mialon, Citation2018; Reeve & Gostin, Citation2019).

Building on this CPA literature, and the recent work of Gómez (Citation2020), the cases of Mexico and Brazil in this article once again highlight the importance of information, constituency-building, and financial incentives tactics used by industry to influence NCD policy. The first tactic is industry’s policy partnership with government, as emphasised by Savell et al.'s (Citation2014) information tactic. That is, and as seen in both countries, the ultra-processed foods and beverages industry leaders often work with health officials to create NCD prevention programmes, in turn helping bolster industry’s political and social acceptability. The second CPA tactic seen in both countries was Hillman and Hitt (Citation1999) and Savell et al.’s (Citation2014) notion of constituency-building, mainly by way of industry’s creation of social allies. That is, industry leaders in Mexico and Brazil have supported academic researchers and poor communities through the provision of research grants, social services, and employment programmes. Through these efforts, it appears that industries have built the political and social support needed to avoid either the creation of stringent policy regulations and/or the enforcement of existing regulations. However, to further ensure that policies work in their favour, industry representative associations in both countries have also engaged in the provision of largesse to legislative representatives, thus illustrating Hillman and Hitt’s (Citation1999) and Savell et al.'s, (Citation2014) position about the importance of financial incentives as industry policy tactics.

Nevertheless, through the cases of Mexico and Brazil in this study, the author went a step further than the CPA literature to address the collective action consequences associated with industry’s constituency-building partnership with society. Indeed, and as discussed in more detail shortly, yet another lesson that emerges from these countries is the negative effects that these industry partnerships with society have on civic mobilisation and opposition to industry’s political involvement. Like the work of Gómez (Citation2019, Citation2020), the author’s findings suggest that these industry’s partnership with non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and scientific researchers may contribute to the creation of divisions within society, where researchers and civic advocates (e.g. economic libertarians) compete with those NGOs and/or activists striving to defend the public’s health interests. In Mexico and Brazil, these divisions may limit the latter’s ability to effectively mobilise in opposition to industry’s policy interference.

Nevertheless, it is important to emphasise that not all scientists work in defence of industry. Mexico and Brazil have several nutrition scientists that are conducting objective research, critiquing industry’s policy position, while advocating for effective public health measures. The National Institute of Public Health in Mexico has evaluated and provided recommendations for improved food labelling throughout Latin America (Barquera, Citation2016), while the University of São Paulo, with its studies on the effectiveness of a potential soda tax (Claro et al., Citation2012), has provide examples of where research scientists are defending the public’s health interests.

In addition, this article suggests that it is important to understand how the broader political and historic bureaucratic context further constrains the national government’s willingness to partner with society with respect to NCD policy. For example, within those countries displaying high concentrations of political authority, politicians and bureaucrats are historically disinclined to proactively work with civil society on health policy issues, for a variety of reasons, ranging from elitism in politics to a lack of confidence in society’s policy knowledge (Gómez & Ménzez, Citation2021). As the author discusses with the case of Mexico below, governments were often unwilling to listen to activists defending the public’s nutrition and obesity policy interests. And even in Brazil, which has historically seen the government work closely with NGOs and activists on the issue of healthcare, going so far as to create national, state, and municipal health participatory councils guaranteeing civil society’s voice and influence within government, this article suggests that politicians and bureaucrats have not been as committed to working with them when it comes to regulating ultra-processed foods and beverages industries, while nevertheless doing so with respect to prevention policy. These findings, therefore, suggest that the government is often selective on the particular NCD policy issues it is willing to work with civil society on ( and ).

Table 1. Mexico – Industrial, government, and civil societal actors.

Table 2. Brazil (industrial, government, and civil societal actors).

Mexico

Policy and research manipulation

In recent years, Mexico’s government has positively responded to their obesity and diabetes epidemic by passing national legislation seeking to prevent and treat these ailments. Authorised by the congress in 2014, a major initiative has been the National Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Overweight, Obesity, and Diabetes. This policy emphasises three key areas: public health, medical attention, and health regulation. Through a variety of primary care initiatives, the Secretariat of Health (SoH) prioritised the prevention and treatment of NCDs such as diabetes and hypertension. At the state-level, Seguro Popular, which provides health insurance for the poor, has also helped to increase awareness about proper nutrition through local primary care clinics.

After years of negotiating with activists and the international community, in January 2014, the Enrique Peña Nieto (PRI, 2012–2018) administration passed a national tax on soda consumption, which entailed a tax of one peso per litre on sugary drinks. The goal was to prevent ailments such as obesity and diabetes by disincentivising soda consumption, while in the process collecting revenue and reinvesting in public health programmes. This tax was part of a broader tax reform effort. Shortly thereafter several studies emerged claiming that the tax was successful, leading to a reduction on consumption, while others claimed that it essentially had no effect on consumption (Villafranco, Citation2016). Nevertheless, many viewed the tax as marking an unwavering government commitment to challenging the soda industry head-on. Furthermore, taxes were also imposed on fast foods. In January 2014, the Senate succeeded in introducing an 8 per cent ad valorem tax on high-caloric foods (increased from 5 per cent), such as chocolates, ice cream cookies, and sugary meals, although this legislation excluded some unprocessed foods (Gutiérrez, Citation2013).

But did Mexico’s government succeed in curbing the policy influence of ultra-processed foods and beverages industries? This does not appear to be the case. With respect to the sale of industry products, in 2010, the government worked with industry leaders to establish the National Agreement on Food Health (ANSA), which led to two main documents: The Technical Bases of the National Agreement and the General Guidelines for the Sale or Distribution of Food and Beverages in School Consumption Facilities (Secretaria de Salud, Citation2010). However, Taylor and Jacobson (Citation2016) claim that neither the government nor industry complied with ANSA’s regulations. And in 2012, after researchers from the National Institute of Public Health (NIPH) worked with the Secretary of Health (SoH) to create a national recommendation on the daily consumption of beverages, complete with a visual diagram in the shape of a drinking jug, it was never officially adopted (Rosenberg, Citation2015). One of the authors of this recommendation, Dr. Juan Rivera of the NIPH, claimed that ‘opposition from the industry was tremendous’ (Rivera quoted in Rosenberg, Citation2015, p. 1).

Yet another area where ultra-processed foods and beverages industries have been successful has been in manipulating scientific research. For example, the ConMéxico foundation, which is supported by Coca-Cola and other industries, funded university academics at prestigious universities to question the effectiveness of the aforementioned sugar tax on reducing soda consumption (Arena Pública, Citation2016; Gómez, Citation2019). Another tactic these industries have used is to work with non-profit organisations, such as the Mexican Diabetes Association, to organise academic conferences on nutrition (Gómez, Citation2019; Rosenberg, Citation2015). Prior to the 2014 vote on the soda tax, for example, Coca-Cola worked with the Monterrey chapter of the Mexican Diabetes Association to fund a presentation given by a prominent nutrition scientist, Dr. Jorge A. Mendoza López, titled ‘Physical Activity for People Living with Diabetes’ (Rosenberg, Citation2015, p. 1).

Some soda industries have taken the extra step of financing the creation of international foundations that conduct research and advocate for public health messages supporting their research claims. For example, in 2014, Coca-Cola donated $1.5 million to support the creation of the Global Energy Balance Network (O’Connor, Citation2015). This foundation is focused on raising awareness about the importance of daily physical exercise, claiming that it is the lack of sufficient exercise and not excess calories that contributes to obesity (Kilpatrick, Citation2015; O’Connor, Citation2015). Coca-Cola was also a founding partner of the Exercise is Medicine (EIM) global foundation and selected Dr. Jorge A. Mendoza López to head its Mexican branch (Rosenberg, Citation2015). In 2006, Coca-Cola even partnered with the SoH’s CONADE (Comisión Nacional de Cultura Física y Deporte) to create an obesity and diabetes prevention programme titled Ponte al 100, which was focused on helping children exercise in schools in order to reduce obesity (Coca-Cola Mexico, Citation2013). This has been one of several strategies that Coca-Cola has used to improve its image as a socially conscious, caring industry that tries its best to help reduce obesity, diabetes, and associated diseases. Other social marketing tactics have included sponsoring sporting events, regional and national soccer clubs, and even working with government to provide annual prizes. Indeed, in 2015, Coca-Cola partnered with Mexico’s national science research funding agency, CONACyT (Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Technología), to fund a prize titled ‘Mejoramiento de la Salud de la Población Mexicana’ (Improving the Mexican Population’s Health) (CONACyT, Citation2016; Lajous & López-Ridaura, Citation2015). Through these activities, Coca-Cola has for the most part succeeded in swaying attention away from the scientific truths underlying the connection between the consumption of sugar, excess weight, obesity, and diabetes.

Industry’s political activities and policy influence

Mexico and information processes

In Mexico, ultra-processed foods and beverages industries were particularly successful in establishing allies within government, a key component of CPA’s information tactics, as mentioned earlier. For example, within the Secretariat of Health (SoH), several industries worked closely with the former Secretary of Health, Mercedes Juan López, who served under the Enrique Peña Nieto administration (2012–2018) (Cecile, Citation2017; Gómez, Citation2019). Her partnership with these industries emerged even before she entered the bureaucracy in her position as president of FunSalud (Fundación Mexicana para la Salud, Mexican Foundation for Health) (Lira, Citation2018). Both at FunSalud and the SoH, Mercedes supported these industries’ emphasis on the importance of exercise as a solution to weight control (Rosenberg, Citation2015). In another instance, in 2007, PepsiCo worked with the Secretariat of Public Education, namely Josefina Vazquez Mota (Proceso, Citation2008). PepsiCo representatives and Mota worked together to create the Vive Saludable Escuelas programme, which encourages daily exercise in schools to help burn calories and avoid overweight and obesity (Proceso, Citation2008). Former Secretary of Health, Julio Frenk, had also worked with PepsiCo, inaugurating one of their plants, while publicly stating that there are no bad ingredients in diets, just informed and uninformed diets (Proceso, Citation2008). These allies within the highest echelons of the bureaucracy, therefore, appeared to help ultra-processed foods and beverages industries decrease government support for programmes that went against their interests.

Mexico, constituency-building, and its civic consequences

Yet another challenge has been industry’s impact on civil society. For instance, in recent years Coca-Cola has provided funding and technical support to a group of supportive NGOs and research scientists championing the former’s cause. In addition to working with prestigious university academics through foundations, such as ConMéxico (Coca-Cola, Sala de Prensa, Citation2018; Taylor & Jacobson, Citation2016), Coca-Cola is associated with NGOs focusing on protecting individual liberties, as well as think-tanks, such as FunSalud (Cecile, Citation2017; Lira, Citation2018). As previously mentioned, Coca-Cola has also worked with Mexico’s National Diabetes Association to fund conferences and researchers supporting Coca-Cola’s public health messages on the importance of physical exercise.

At the same time, however, other NGOs and academics have focused on mobilising against industry’s interests, such as El Poder del Consumidor, Fundación Mídete, ContraPESO, and researchers from the National Institute of Public Health (El Poder del Consumidor, Citation2012). Together, they have created the Alianza por la Salud Alimentaria (El Poder del Consumidor, Citation2012). While receiving limited financial support from the Bloomberg Foundation (Bonilla-Chacín et al., Citation2016), these NGOs and the Alianza have received insufficient funding, thus making it difficult to compete with the aforementioned civic organisations working with industry, who have comparatively far more resources (Barquera et al., Citation2013). Thus, by targeting and supporting activists and researchers that could potentially work with the Alianza, industries have in essence divided society and its ability to more effectively mobilise and pressure the government for effective regulatory policies.

The government’s repeated unwillingness to work closely with those activists in favour of regulating the ultra-processed foods and beverages industry has further complicated matters. With respect to the soda tax, several years before the 2014 decision to introduce this policy, activists had been pressuring the government to adopt a tax (Bonilla-Chacín et al., Citation2016). Activists were also raising awareness about the country’s health crisis for several years (Bonilla-Chacín et al., Citation2016). The government’s unwillingness to pay heed to these pressures reflected its historic unwillingness to work closely with civil society on public health matters, reflecting an enduring culture of elitism in health policy-making (Gonzalez-Rossetti, Citation2001). This was especially the case when it came to nutritional issues. Indeed, the founding director of the Centre for Research in Nutrition in the National Institute of Public Health, Dr. Juan Rivera, claimed in 2015 that ‘There is no tradition in Mexico of listening to civil society on the issue of food … the tradition here is that aristocrats don’t talk to anyone who isn’t of their social class. Civil society is seen as making trouble’ (Rivera quoted in Rosenberg, Citation2015, p. 1).

Mexico and industry financial incentives

In addition, congressional members have also benefited from receiving formal and informal contributions from industry lobbyists in order to influence policy. Indeed, in recent years, the Chamber of Deputies (House) has been seen as an institution that industries can rely on for support. Some claim that representative Deputies are often absent and seen at expensive restaurants paid for by industry (Cecile, Citation2017). Some, in fact, view the congress as ‘home turf’ for big food industry lobbyists (Rosenberg, Citation2015, p. 1). One Senator from the PAN political party, Marcela Torres Peimbert, even stated that: ‘When we want help with a campaign, they [industry] are here to help’ (quoted in Rosenberg, Citation2015, p. 1). Research by Gómez (Citation2019) reveals that these lobbying contributions contributed to the delayed passage of the soda tax (attempted in 2008 and 2012) and other industry regulatory policies. However, constitutional reforms introduced in 2011 now prohibit corporate donations to the congress (O’Neil, Citation2013). Thus, these findings appear to illustrate the CPA’s literature’s emphasis on financial incentives as a tactic used by industry to obstruct the policy-making process.

Brazil

Policy and research manipulation

Similar to Mexico, since the transition to democracy and the introduction of free markets, ultra-processed foods and beverages industries in Brazil have had a considerable amount of influence over public health policy and scientific research. In recent years Brazil’s Ministry of Health (MoH) has nevertheless been successful in introducing a host of measures focused on increasing awareness about the health consequences associated with consuming industry products, such as the 1996 Política Nacional de Alimentação e Nutrição (PNAN, National Policy of Nutrition), the 2007 Programa Saúde nas Escolas (PSE, Programme of School Health), while working with primary care providers through the Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS), Brazil’s decentralised universal healthcare system, via the 2010 Plano de Ações Estratégicas para o Enfrentamento das Doenças Crônicas Não Transmissíveis (DCNT, Strategic Action Plan for Confronting NCDs). The DCNT programme creates several national programmes focused on promoting increased physical activity, the promotion of nutritious foods and healthy eating, and regulations on tobacco and alcohol consumption (Malta et al., Citation2011). Since 2014, several additional MoH programmes have been created to help increase family awareness about the importance of home cooking and eating more nutritious meals. However, when it came to policies preventing NCDs and regulating industry marketing and sales, the MoH was not nearly as successful.

Indeed, with respect to establishing a national soda and snack food tax as a policy tool helping prevent obesity and diabetes, in contrast to what we saw in Mexico, despite recommendations from the MoH for a tax (Militão, Citation2019), no concrete government effort has been made to achieve this. It seems that the reluctance to introduce a soda tax may be the result of intensive lobbying pressures from industry representatives to question the tax proposal. Analysts note that in October 2017, ABIR’s (Associação Brasileira das Indústrias de Refrigerantes) president, Alexandre Jobim, attended a congressional hearing within the Câmara dos Deputados (e.g. Congress) to debate the creation of a soda tax, questioning its justification when considering an individual’s nutritional and physical behaviours (Peres, Citation2017). In 2018, at a public hearing organised by the congressional Social Security Commission, Jobin once again argued against a proposed tax, claiming that the government should not turn into a nanny state, advocating instead for individual choice (Mugnatto, Citation2018). That same month, SBAN (Sociedade Brasileira de Alimentação e Nutrição) also argued against the introduction of a tax during a public congressional debate, with SBAN’s representative, Marcia Terra, claiming that, while still awaiting a final decision on the matter, the evidence would eventually prove the tax’s ineffectiveness (Secretaria Geral, Citation2017). At this meeting, congressional representatives were divided over the introduction of a soft drink tax (Secretaria Geral, Citation2017). In this context, what has resulted instead has been ongoing debates about the need for a soda tax (Whitehead et al., Citation2016).

With respect to the marketing of ultra-processed foods and beverages, in 2006 the ANVISA (Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária) introduced for public discussion proposed regulations on the marketing of ultra-processed foods to children on TV commercials, radio, and the usage of cartoon characters in advertisements (Hartung & Karageorgiadis, Citation2016). While these discussions eventually led to the passage of the Resolução da Diretoria Colegiada (RDC), n. 24/2010 (Hartung & Karageorgiadis, Citation2016), these regulatory efforts were fiercely contested by the food industry, motivating them to submit 11 lawsuits in response (Hartung & Karageorgiadis, Citation2016). Industry’s opposition was based on its belief that these policies were acts of government censorship – indeed, it was industry (who worked in a low profile through the Association of Food Industries, ABIA, Associação Brasileira da Indústria de Alimentos) that referred to years of censorship under the military dictatorship of the 1960s and 1970s when justifying their claims (Jacobs & Richtel, Citation2017). However, in 2013, RDC n. 24/2010 was surprisingly revoked by the 6th Committee of the 1st region of the Federal Regional Court, based on ABIA’s vehement appeal (Kassahara & Sarti, Citation2018; see also Jacobs & Richtel, Citation2017). ABIA claimed that the courts lacked ‘ … jurisdiction for the imposition of penalties on food and beverage advertisements by ANVISA’ (Kassahara & Sarti, Citation2018, p. 590). The Conselho Nacional de Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional (CONSEA, National Council for National Nutrition Security) counteracted by proposing to the congress that new regulatory measures be introduced, grounded on the issue of human rights and access to sound nutrition and information (especially for children) (Kassahara & Sarti, Citation2018), while the Conselho Nacional dos Direitos da Criança e do Adolescente (CONANDA, National Council for the Rights of the Child and the Adolescent) claimed that industries marketing their products towards children were unjust and abusive (Kassahara & Sarti, Citation2018). Nevertheless, the politics surrounding the obstruction of the RDC 24/2010 was a good example of the policy interference of industry’s in Brazil, to the detriment of children’s health (Mariath & Martins, Citation2020).

Despite these demands for heightened government regulation, to this day, no such federal regulations, upheld by the constitution, exist. Instead, industries have opted to self-regulate the advertisement of their products, agreeing to work with, and be monitored by, an NGO that works closely with the MoH, namely the Conselho Nacional de Autorregulamentação Publicitária (CONAR, Council of Self-Regulatory Publicity). CONAR works to ensure that industries adhere to their self-imposed regulations (Vendrame & Pinsky, Citation2010). Nevertheless, research finds that CONAR has been limited in punishing industries for their violations (Kassahara & Sarti, Citation2018). In this context, industries have pushed for ongoing self-regulation. In 2016, for example, 11 industries, Coca-Cola Brasil, Nestlé, PepsiCo, Unilver, Ferraro, McDonald’s, Mondeléz International, Grupo Bimbo, Kellogg’s, General Mills, and Mars created an agreement that they would refrain from marketing their unhealthy products to children under the age of 12 (Alves, Citation2016). And in a move that was supported by nutrition activists from the Instituto Alana, in 2016, ABIR followed suit by announcing that it would not market its unhealthy non-alcoholic products to children up through the age of 12 (Revista ABIR, Citation2019). In 2018, other food industries, such as Italy’s Barilla, launched their own self-regulatory efforts in food advertising, emphasising information transparency, no manipulative or ambiguous/confusing messaging, respectful of the complex nature and needs of the individual (Barilla, Citation2018), while realising that children are a sensitive marketing target (AlimentosProcessados, CitationN/D) and have a right to truthful information (Barilla, Citation2018). Finally, in 2018, the MoH introduced a voluntary partnership agreement with industry to reduce, by 2022, an estimated 144 thousand tons of sugar in their processed food products (ACT Promoção da Saúde, Citation2019).

When it came to regulating ultra-processed foods and beverages sales, essentially no federal regulations confirmed by the constitutional courts exist (Lott, Citation2018). Instead, industry leaders, together with the Brazilian Association of Beverage Companies (IBIR, Associação Brasileira das Industrias de Refrigerantes e de Bebidas não Alcoólicos), have succeeded in engaging in self-regulatory practices (see also Johns & Bortoletto, Citation2016). IBIR has managed to convince lawmakers that it will refrain from selling their products within schools, in turn giving the impression that it supports the MoH’s strategy to increase the provision of more nutritious foods in schools, in partnership with local farmers through the MoH’s Saúde Nas Escolas programme. Sugary beverages with added sugars nevertheless continue to be sold in schools, often purchased through third parties rather than directly from industry retailors (Johns & Bortoletto, Citation2016). In response, when the idea of creating formal regulations restricting sales at schools was proposed, industry leaders argued that this was not a good idea, that the government was too overwhelmed with other matters, such as responding to the Zika public health outbreak at the time (Johns & Bortoletto, Citation2016). In 2016, the government's interim Health Minister, Ricardo Barros, was noted as publicly stating his commitment to banning the sale of ultra-processed foods within government agencies and hospitals (Huber, Citation2016). Yet these ideas, e.g., sales regulations, was also resisted by several trade groups in Latin America participating in the Latin America Food and Beverage Alliance (Huber, Citation2016).

In contrast to Mexico, Brazil has been more progressive with respect to providing public awareness campaigns focused on sound nutrition. In 2014, for example, the MoH created the Guia Alimentar para a População Brasileira (Food Guide for the Brazilian Population); this guide provides revised nutritional recommendations to the general population for how to improve daily nutrition, emphasising the consumption of natural foods, home cooking, a balanced diet, and a decrease in consumption of processed and fast foods (Oliveira and da Silva Santos, Citation2020). Several other MoH campaigns and guidelines followed suit, focused on improved daily eating, self-awareness, and overall nutrition. However, when it came to policies directly targeting the activities of ultra-processed foods and beverages industries, fewer regulations were found. Instead, industry was more successful at engaging in formal agreements, giving the perception that it agreed with the MoH’s mission to improve overall public health. For instance, in 2007 and 2010, industrial leaders engaged in a formal agreement with the MoH that these companies would reduce the content of trans fat, salt, and sugar in their processed foods (Block et al., Citation2017). In essence, this is a form of self-regulation, with industry repeatedly engaging in dialogue and cooperative agreement with the government in order to thwart the passage of legislation. Nevertheless, the congress and MoH did succeed in passing a law in 2003 requiring food labelling on all products (Block et al., Citation2017). This labelling displayed nutritional and calorie information and adhered to the WHO’s 2004 Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health (Block et al., Citation2017).

Brazil’s ultra-processed foods and beverages industries have also been successful in distorting the science behind nutrition and manipulating scientific research. For example, in 2011, food and soda companies sponsored a ‘science-based’ nutrition conference organised bi-annually by the Sociedade Brasileira de Alimentação e Nutrição (SBAN, Brazilian Society for Health and Nutrition), titled ‘How Scientific Evidence Should Be Determined’ (Canella et al., Citation2015). The diamond sponsor of this event was a world-famous manufacturer of non-alcoholic beverages and syrups, and three other gold sponsors were prominent industry and pharmaceutical companies (Canella et al., Citation2015). Scientific professionals participating at satellite symposiums of this event, e.g. ‘Adoption of Healthy Lifestyles’, seemed to emphasise industry’s simplistic position on the importance of individual responsibility in exercise and consumption, downplaying any socioeconomic and cultural conditions contributing to poor nutrition and health ailments (Canella et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, and similar to what was seen in Mexico, industries have been notorious for providing grants to nutrition science researchers publishing findings that support industrial views (Jack, Citation2011).

Industry’s political activities and policy influence

Brazil and information processes

Similar to what was seen in Mexico, ultra-processed foods and beverages industries in Brazil have also sought to establish strong networks of support within government. Within government, corporations such as Nestlé appear to have been successful in establishing connections with ministers of health and at times taking advantage of their direct access to them to complain about policy ideas (Jacobs & Richtel, Citation2017). In this context, it appears that Nestlé has been able to delay healthcare legislation, such as in the area of infant nutrition (Jacobs & Richtel, Citation2017). In another instance, food industries and their representatives such as ABIA, also partnered with the MoH in 2007 to reformulate their food products, such as reducing sugar, sodium, and fat in their food products (Nilson, Citation2015). And yet, research by Monteiro and Cannon (Citation2017) claims that these partnerships have helped industry by in a sense motivating government not to pursue more stringent regulatory policies, e.g. marketing and sales to children. In accordance with the CPA literature’s emphasis on the challenges of industry information tactics, the government’s policy partnerships with industry appear to have contributed to hampering the creation of stringent regulatory policies.

In contrast to what was seen in Mexico, however, little evidence suggests that Nestlé and other industries in Brazil have been successful in working closely with other areas within the Ministry of Health (MoH) on obesity and diabetes prevention programmes, such as physical exercise in schools. Those MoH departments working on these issues and basic primary care through SUS have for the most part remained isolated from corporate interference, influenced more by their normative and scientific commitment to reducing the consumption of these foods (Gómez, Citation2018).

Brazil, constituency building, and its civic consequences

Nevertheless, industries in Brazil have been successful in dividing civil society’s collective response to their policy influence. Similar to what we saw in Mexico, select industries have been successful at working with vulnerable groups, providing support and it seems incentivising them not to criticise their products. Once again, Nestlé provides a good example. In recent years, this company has worked with the poor in urban slums and rural areas, offering lucrative jobs, particularly woman, through the company’s Nestlé até Você (Nestlé comes to you) programme (Terra, Citation2009); through this initiative, workers help to distribute Nestlé products (Terra, Citation2009). Moreover, through this programme Nestlé has provided families with additional income (Jack, Citation2011; Jacobs & Richtel, Citation2017). Nestlé has also worked with NGOs in Brazil, through its Nestlé Torce por Vocé (Nestlé Cheers for You) programme to promote the importance of being physically active and good nutrition, even sponsoring cooking clubs (Nutrição em Pauta, Citation2008). Other companies, such as Coca-Cola, have also sponsored conferences on physical activity and public health (Hérick de Sa, Citation2014) while working with universities to promote physical education (Peres, Citation2018). These activities align with the CPA literature’s emphasis on constituency-building in society. Some pundits claim that these activities, e.g. partnering with universities, have been done to bolster industry’s image within government, while legitimising industry’s position on the importance of individual responsibility with respect to obesity (Peres, Citation2018).

At the same time, several NGOs have emerged to criticise and oppose Nestlé and other industry’s policy interference. Building on a long history of civic mobilisation on the issue of good nutrition as a human right, organisations such as the Instituto Alana, Instituto Brasileiro de Defesa do Consumidor (IDEC), ABESO, ACT+, ASBRAN (Brazilian Association of Nutrition) have worked together to raise awareness about industry’s negative effects on nutrition, while lobbying government for more aggressive regulatory policies against this industry (Gómez, Citation2018). Nevertheless, the latter’s voice and influence has been hampered due to the lack of support that they receive from large segments of the poor that support industries, primarily for economic gain but also for access to food.

But why have activists been unable to influence the government’s regulatory stance against industry? This is puzzling if one considers the rich history in Brazil, stemming from the 1960s and 1970s, of activists working with government to promote the idea of sound nutrition and health as a human right (Aranha et al., Citation2009). In 1993, CONSEA (Conselho Nacional de Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional, National Council for Food and Nutritional Security) was formed as a government-sponsored participatory institution, governed and chaired by activists, guaranteeing the latter’s input into nutritional policy-making. During this transitional period of government from the President Itamar Franco (1992–1995) to the Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1995–2003) administration, CONSEA’s role was somewhat insignificant amidst a severe economic recession. Eventually, the Cardoso administration extinguished CONSEA and appeared to replace it with other similar federal initiatives (Vasconcelos, Citation2005). For example, in December 1995, Cardoso introduced via executive decree N 1.366 the Programa Comunidade Solidária (Community Solidarity Programme), a collaborative state-civil societal partnership with the goal of eradicating poverty and social exclusion, while also creating the Conselho da Comunidade Solidária (Council of Community Solidarity), led by First Lady Ruth Cardoso (Vasconcelos, Citation2005). Subsequent to these initiatives the Coordenação-Geral da Política de Alimentação e Nutrição (CGPAN) (General Coordination of the Policy for Food and Nutrition) was created in 1998, within the MoH, which focused on health, nutrition, establishing national guidelines in these areas (Vasconcelos, Citation2005), while committing to establishing the human right to food, with an initial focus on addressing Anemia (Bomtempo Birche de Carvalho et al., Citation2011). CGPAN, through the National Food and Nutrition Policy (PNAN) created in 1999, with PNAN being an important policy strategy for CGPAN, also established one of the world’s first national obesity prevention programmes, while focusing on improving the nutrition and health of nursing mothers, pregnant women, and children through the Bolsa Alimentação programme, a beneficiary cash transfer programme, managed by CGPAN (Vasconcelos, Citation2005).

The Lula administration (2002–2010) re-introduced CONSEA and placed it within the office of the presidency, essentially guaranteeing access to key policy-makers and presidential support (Leão & Maluf, Citation2012). However, CONSEA was only successful in influencing MoH public awareness and prevention programmes, as reflected in the phalanx of nutritional and NCD prevention programmes that the MoH adopted during Lula’s term (Gómez, Citation2018). At no point were activists’ views on the importance of proactively regulating the marketing and sale of industry products considered. Worse still, under the conservative Jair Bolsonaro presidency (2019-present), CONSEA ceased to exist, a radical institutional change undermining nutrition activists’ ability to influence policy (Motta, Citation2020).

Brazil and industry financial incentives

Furthermore, in recent years ultra-processed foods and beverages lobbyists have been able to hamper the policy-making process by aggressively lobbying and paying-off legislatures, mainly through the form of campaign donations (Weissheimer, Citation2017). Such activities are in accordance with the aforementioned CPA literature’s emphasis on the usage of financial incentives by industry, that is, using industry funds to target and influence policy-makers. In 2014, for example, major food companies donated an estimated $158 million to several congressional members, a ‘three-fold increase over 2010’ (Jacobs & Richtel, Citation2017, p. 1). According to Jacobs and Richtel (Citation2017, p. 1), an in-depth study provided by Transparency International in 2016 found that ‘ … more than half of Brazil’s current federal legislators had been elected with donations from the food industry – before the Supreme Court banned corporate contributions in 2015’. The biggest contributor was the Brazilian meat conglomerate JBS (Jacobs & Richtel, Citation2017). In 2014, JBS provided candidates with $112 million in funds (Jacobs & Richtel, Citation2017). Coca-Cola also provided $6.5 million in 2014, followed by McDonalds with $561,000 (Jacobs & Richtel, Citation2017). In this context, it appears that industries have been very successful in thwarting regulations that can potentially thwart their operations. Nevertheless, it is also important to note that in 2015, Brazil’s Supreme Court officially banned corporate donations from major industries, which emerged amidst a major corruption scandal that involved then President Dilma Rousseff (Douglass, Citation2015).

Discussion

In conclusion, it should not come as a surprise that within upper-middle-income countries, big businesses have considerable political and policy influence. The goal of this article has not been to question this fact but to provide additional insights into how and to what extent ultra-processed foods and beverages industries have been able to obstruct public health policies targeting their marketing and sales while manipulating scientific research.

While the recent corporate political activities (CPA) literature provides several empirical approaches to understanding the tactics that industries use to influence NCD policy, we know less about the strategies that these industries adopt to shape the political and social context of the policy-making process. As we saw in Mexico and Brazil, industries are quite entrepreneurial in establishing partnerships both within and outside of government, securing advocates and defending their interests. Industries also create divided societies, that is, pitting their civic supporters, often acquired through academic partnerships and employment opportunities, against those defending the public’s health interests. With decreasing sales in their traditional home markets, such as in the United States and Europe, these industries have had incentives to become innovative in how they go about establishing allies and ensuring that they can continue to obstruct regulatory policies, even in a context where governments, as seen in Mexico and Brazil, succeed in creating innovative prevention programmes addressing NCDs.

Evidence from Mexico and Brazil aligns with the CPA literature emphasising how industry partnerships with government can hamper the NCD policy-making process (Savell et al., Citation2014). In addition, an important lesson that emerges from this article is how industries are strategically partnering with government to create innovative obesity and type-2 diabetes prevention programmes in order to garner political and social support. Through these endeavours, industries are viewed as socially-conscious and committed to avoiding these ailments. This is a political tactic that these industries are using to thwart any potential opposition and the introduction of potentially threatening regulations, a finding that comports with other scholars on this issue (Tanrikulu et al., Citation2020).

Nevertheless, industry’s ability to shape domestic politics provides necessary but insufficient conditions for their on-going policy influence. This article has introduced other aspects that we should consider, such as the importance of a comparative historical analysis of federal government commitment to working closely with civil society on all aspects of NCD policy, including prevention and regulation. Indeed, with respect to industry regulatory policies, equally as important has been the government’s unwillingness to work closely with civil societal activists on this issue, either due to a lack of trust or fear in the latter’s ability to obstruct the policy-making process. As seen in Brazil, while some governments have created participatory institutions providing voice to those activists clamouring against business, evidence suggests that these institutions matter less when it comes to regulatory policies directly affecting industries. This, in turn, suggests that governments are selective in the types of health policy issues it is willing to work with civil society on, i.e. working closely with society on general NCD prevention programmes but not on regulatory policies directly threatening industry’s marketing and sales activities.

Going forward, those focused on addressing the CPA literature may consider the historical and contemporary political reasons for why governments have been selective in their relationship with civil societal actors in the area of NCD policy. Have politicians and bureaucrats been captured more by industry’s interests in the area of industry regulation as opposed to malnutrition and food security?

In addition, findings in this article go a step further then the CPA literature by illustrating how industry’s constituency-building partnerships can generate divisions within society, while examining the obstacles that civil societal actors have in mobilising in response to lacklustre regulatory policy – and the fears and threats from industries that activists face when mobilising and raising awareness about industries harmful products and policy obstruction (Mialon et al., Citation2020b). The findings from Mexico and Brazil in this article suggest that industry’s alliance with other segments of society, such as influential university researchers and conservative-leaning NGOs, is hampering the rest of society’s ability to effectively mobilise in opposition to industry’s ongoing policy influence. CPA scholars may, therefore, benefit from partnering with social scientists in addressing these critical issues and improving CPA approaches to explaining industry’s ongoing NCD policy influence.

Future work will also need to consider other issues that have not been addressed in this article. For example, to what extent have industries not only shaped domestic politics and policymaking, but also fast-food cultures, in turn leading civil society – especially the poor – to ignore nutritional advice and refrain from collective mobilisation? How have politicians strategically used these new cultures to deflect further regulatory initiatives? And within an increasingly decentralised context, to what extent have industries been as successful in shaping local municipal politics and politicians’ interests? There is ample room for further investigation. This should motivate social scientists and public health experts to work together in understanding and explaining why these industries continue to be so successful in upper-middle-income countries, even in a context where governments have been more proactive in preventing and treating NCDs.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Ally Wolloch for editorial assistance during the research and writing of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- ACT Promoção da Saúde. (2019). Doenças Crônicas Não Transmissíveis no Brasil. https://ncdalliance.org/sites/default/files/resource_files/Civil%20Society%20Status%20Report%20ACT.pdf

- AlimentosProcessados. (N/D). Publicidade e propaganda responsáveis. iTAL, Secretaria de Agricultura, Governo do Estado de São Paulo. https://alimentosprocessados.com.br/iniciativas-empresariais-publicidade-propagenda.php

- Alves, G. (2016). Indústrias de alimentos criam regras de publicidade para crianças. Folha de São Paulo, December 16.

- Aranha, A., da Costa Lunas, A., Basco, C. A., Marcatto, C., Moreira, C., Recine, E., Pierri, F., da Fonseca Menezes, F. A., Peiter, G. M. C., Tubino, J., Muller, L., Filho, M. R., Beghin, N., Heck, S., & Porto, S. (2009). Building up the national policy and system for food and nutrition security. CONSEA, Office of the President.

- Arena Pública. (2016). Refresqueras pagan a Universidades Mexicanas para Cuestionar Impactos del Impuesto a las Gaseosas. Retrieved December 31, 2020, from https://www.arenapublica.com/articulo/2016/10/11/5176

- Barilla. (2018). Barilla’s principles on responsible food marketing. Barilla Group. Retrieved May 11, 2021, from https://www.barillagroup.com/sites/default/files/Responsible%20Marketing%20Principles.pdf

- Barquera, S. (2016). Review of current labelling regulations and practices for food and beverage targeting children and adolescents in Latin American countries (Mexico, Chile, Costa Rica, and Argentina) and recommendation for facilitating consumer information. UNICEF Publications.

- Barquera, S., Campos, J., & Rivera, A. (2013). Mexico attempts to tackle obesity: The process, results, push backs and future challenges. Obesity Reviews, 14(Suppl 2), 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12096

- Bennett, A. (2012). Case study methods: Design, use, and comparative advantages. In D. Sprinz, & Y. Wolinsky-Nahmias (Eds.), Models, numbers, and cases: Methods for studying international relations (pp. 19–55). University of Michigan Press.

- Block, J. M., Arisseto-Bragotto, A. P., & Feltes, M. M. C. (2017). Current policies in Brazil for ensuring nutritional quality. Food Quality and Safety, 1(4), 275–288. https://doi.org/10.1093/fqsafe/fyx026

- Bomtempo Birche de Carvalho, D., Malta, D. C., Duarte, E. C., Sardinha, L. M. V., de Moura, L., Libânio de Morais Neto, O., Vasconcelos, A. B., & de Oliveira Pinheiro, A. R. (2011). Estudo de caso do processo de formulação da Política Nacional de Alimentação e Nutrição no Brasil. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde, 20(4), 449–458. https://doi.org/10.5123/S1679-49742011000400004

- Bonilla-Chacín, M., Iglasias, R., Agustino, S., Claudio, T., & Claudio, M. (2016). Learning from the Mexican experience with taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages and energy-dense foods of low nutritional value. Health, nutrition and population discussion paper. The World Bank Group.

- Budreviciute, A., Damiati, S., Sabir, D. K., Onder, K., Schuller-Goetzburg, P., Plakys, G., Katileviciute, A., Khoja, S., & Kodzius, R. (2020). Management and prevention strategies for non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and their risk factors. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 574111. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.574111

- Burlandy, L., Alexandre-Weiss, V. P., Canella, D. S., Feldenheimer da Silva, A. C., Paes de Carvalho, C. M., & Ribeiro de Castro, I. R. (2020). Obesity agenda in Brazil, conflicts of interest and corporate activity. Health Promotion International, 36(4), 1186–1197. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daaa085

- Canella, D., Martins, A. P., Silva, H. F. R., Passanha, A., & Lourenço, B. (2015). Food and beverage industries’ participation in health scientific events: Considerations on conflicts of interest. Revista Panamericana de Salud Publica, 38(4), 339–343.

- Carriedo, A., Koon, A., Encarnación, L. M., Lee, K., Smith, R., & Walls, H. (2021). The political economy of sugar-sweetened beverage taxation in Latin America: Lessons from Mexico, Chile, and Colombia. Globalization and Health, 17(1), 5. https:/doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00656-2

- Cecile, A. M. (2017). Big soda: Buying chronic disease. CrossFit Journal. Retrieved July 11, 2018, from https://journal.crossfit.com/article/soda-cecil-2017-2

- Checkley, W., Ghannem, H., Irazola, V., Kimaiyo, S., Levitt, N., Miranda, J. J., Niessen, L., Prabhakaran, D., Rabadán-Diehl, C., Ramirez-Zea, M., Rubinstein, A., Sigamani, A., Smith, R., Tandon, N., Wu, Y., Xavier, D., & Yan, L. (2014). Management of noncommunicable disease in low- and middle-income countries. Global Heart, 9(4), 431–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gheart.2014.11.003

- Claro, R. M., Levy, R. B., Popkin, B., & Monteiro, C. (2012). Sugar-sweetened beverage taxes in Brazil. American Journal of Public Health, 102(1), 178–183. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300313

- Coca-Cola Mexico. (2013). CONADA presenta PONTE AL 100, programa de educación en actividad física y nutrición con el cual se buscará contribuir a reducir los íncides de sobrepeso y obesidad en el país. Sala de Prensa. https://www.coca-colamexico.com.mx/sala-de-prensa/comunicados/conade-presenta-ponte-al-100-programa-de-educaci-n-en-actividad-f-sica-y-nutrici-n-con-el-cual-se-buscar-contribuir-a-reducir-los-ndices-de-sobrepeso-y-obesidad-en-el-pa-s

- Coca-Cola, Sala de Prensa. (2018). Impulsan proyectos de investigación para la creación de soluciones en favour del bienestar de los mexicanos. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- Collins, C., Araujo, J., & Barbosa, J. (2000). Decentralising the health sector: Issues in Brazil. Health Policy, 52(2), 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-8510(00)00069-5

- CONACYT. (2016). Premio de investigación en biomedicina Dr. Rubén Lisker.

- Douglass, B. (2015, September 18). Brazil bans corporations from political donations amid corruption scandal. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/18/brazilian-supreme-court-bans-corporate-donations-political-candidates-parties

- El Poder del Consumidor. (2012). Nace la Alianza por la Salud Alimentaria. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- Fooks, G. J., Williams, S., Box, G., & Sacks, G. (2019). Corporations’ use and misuse of evidence to influence health policy: A case study of sugar-sweetened beverage taxation. Globalization and Health, 15(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-019-0495-5

- Fritscher, A. M., & Zamora, C. R. (2016). An evaluation of the 1997 expenditure decentralization reform in Mexico: The case of the health sector. Public Finance Review, 44(5), 563–588. https://doi.org/10.1177/1091142115571578

- Gallardo-Rincón, H., Cantoral, A., Arrieta, A., Espinal, C., Magnus, M., Palacios, C., & Tapia-Conyer, R. (2021). Review: Type 2 diabetes in Latin America and the Caribbean: Regional and country comparison on prevalence, trends, costs, and expanded prevention. Primary Care Diabetes, 15(2), 352–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcd.2020.10.001

- Gómez, E., & Ménzez, C. (2021). Institutions, policy, and non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in Latin America. Journal of Politics in Latin America, 13(1), 114–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/1866802X20980455

- Gómez, E. J. (2018). Geopolitics in health: Confronting obesity, AIDS, and tuberculosis in the emerging BRICS nations. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Gómez, E. J. (2019). Coca-Cola’s political and policy influence in Mexico: Understanding the role of institutions, interests and divided society. Health Policy & Planning, 34(7), 520–528. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czz063

- Gómez, E. J. (2020). Junk food politics in emerging economies. Johns Hopkins University Press (forthcoming).

- Gonzalez-Rossetti, A. (2001). The political dimension of health reform: The case of Mexico and Colombia. PhD Dissertation, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

- Gortmaker, S., Swinburn, B., Levy, D., Carter, R., Mabry, P., Finegood, D., Huang, T., Marsh, T., & Moodie, M. (2012). Changing the future of obesity: Science, policy and action. The Lancet, 378(9793), 838–847. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60815-5

- Greenhalgh, S. (2019). Soda industry influence on obesity science and policy in China. Journal of Public Health Policy, 40(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41271-018-00158-x

- Gutiérrez, M. A. (2013). Senado de México aprueba reforma fiscal, modifica impuesto clave y otro a comida chatarra. Noticias Principales, Reuters. Retrieved December 17, 2020, from https://www.reuters.com/article/latinoamerica-economia-mexico-reformafis-idLTASIE99U05H20131031?edition-redirect=ca

- Hartung, P. A. D., & Karageorgiadis, E. V. (2016). A regulação da publicidade de alimentos e bebidas não alcoólicas para crianças no Brasil. Revista de Direito Sanitário, 17(3), 160–184. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-9044.v17i3p160-184

- Hérick de Sá, T. (2014). Can Coca Cola promote physical activity? The Lancet, 383(9934), 2041. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60988-0

- Hillman, A., & Hitt, M. (1999). Corporate political strategy formulation: A model of approach, participation, and strategy decisions. ” The Academy of Management Review, 24(4), 825–842. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1999.2553256

- Hillman, A., Keim, G., & Schuler, D. (2004). Corporate political activity: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management Studies, 30(6), 837–857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jm.2004.06.003

- Huber, B. (2016, July 28). Welcome to Brazil, where a food revolution is changing the way people eat. The Nation.

- Jack, A. (2011, April 8). Brazil’s unwanted growth. Financial Times.

- Jacobs, A., & Richtel, M. (2017, September 16). How big business got Brazil hooked on junked food. The New York Times.

- Jaichuen, N., Phulkerd, S., Certthkrikul, N., Sacks, G., & Tangcharoensathien, V. (2018). Corporate political activity of major food companies in Thailand: An assessment and policy recommendations. Globalization & Health, 14, 115. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-018-0432-z

- Jaime, P. C., da Silva, A. C. F., Gentil, P. C., Claro, R. M., & Monteiro, C. A. (2013). Brazilian obesity prevention and control initiatives. Obesity Reviews, 14(S2), 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12101

- James, E., Lajours, M., & Reich, M. (2020). The politics of taxes for health: An analysis of the passage of the sugar-sweetened beverage tax in Mexico. Health Systems & Reform, 6(1), e1669122. https://doi.org/10.1080/23288604.2019.1669122

- Johns, P., & Bortoletto, A. P. (2016). Obesity follows soda consumption like night follows day. NCD Alliance. https://ncdalliance.org/news-events/blog/obesity-follows-soda-consumption-like-night-follows-day

- Kaldor, J. C., Thow, A. M., & Schönfeldt, H. (2018). Using regulation to limit salt intake and prevent non-communicable diseases: Lessons from South Africa’s experience. Public Health Nutrition, 22(7), 1316–1325. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018003166

- Kassahara, A., & Sarti, F. M. (2018). Publicidade de alimentos e bebidas no Brasil: Revisão de literatura científica sobre regulação e autorregulação de propagandas. Interface (Botucatu), 22(65), 589–602. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-57622016.0630

- Kilpatrick, K. (2015, August 19). Taxing soda, saving lives: Mexico's surcharge on sugary drinks is the real thing. Aljazeera America.

- Lajous, M., & López-Ridaura, R. R. (2015). Premio CONACYT-Coca-Cola en medicina: Ciiencia y transparencia. El Poder del Consumidor.

- Leão, M. M., & Maluf, R. (2012). A construção social de um sistema pública de segurança alimentar e nutricional: A experência brasileira (Abrandh and Oxfam). https://raisco.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/a-construc3a7c3a3o-social-de-um-sistema-adrandh.pdf

- Levy, J. (2008). Types, designs, and logics of inference. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 25(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/07388940701860318

- Lima, J. M., & Galea, S. (2018). Corporate practices and health: A framework and mechanisms. Globalization & Health, 14, 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-018-0336-y

- Lira, I. (2018). La salud de los Mexicanos se ha decidido desde el sector privado durante años, dicen especialistas. Senembargo.mx. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- Lott, D. (2018). Publicidade infantil deve ser feita com responsabilidade em vez de proibida, dizem especialistas. Folha de São Paulo, May 18.

- Magnusson, R., McGrady, B., Gostin, L., Patterson, D., & Taleb, H. A. (2018). Legal capabilities required for prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 97(2), 108–117. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.18.213777

- Malta, D. C., de Morais Neto, O. L., & da Silva Junior, J. B. (2011). Apresentação do plano de ações estratégicas para o enfrentamento das doenças crônicas não transmissíveis no Brasil, 2011 to 2012. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde, 20(4), 425–438. https://doi.org/10.5123/S1679-49742011000400002

- Mariath, A. B., & Martins, A. P. B. (2020). Ultra-processed products industry operating as an interest group. Revista de Saúde Pública, 54, 107. https://doi.org/10.11606/s1518-8787.2020054002127

- Mendis, S. (2010). The policy agenda for prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. British Medical Journal, 96(1), 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldq037

- Mialon, M., Charry, D. A. G., Cediel, G., Crosbie, E., Scagliusi, F. B., & Tamayo, E. M. P. (2020a). ‘The architecture of the state was transformed in favour of the interests of companies:’ Corporate political activity of the food industry in Colombia. Globalization and Health, 16, 97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00631-x

- Mialon, M., Khandpur, N., Mais, L. A., & Martins, A. P. B. (2020b). Arguments used by trade associations during the early development of a new front-of-package nutrition labelling system in Brazil. Public Health Nutrition, 24(4), 766–774. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020003596

- Mialon, M., & Mialon, J. (2018). Analysis of corporate political activity strategies of the food industry: Evidence from France. Public Health Nutrition, 21(19), 3407–3421. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018001763

- Mialon, M., Swinburn, B., Wate, J., Tukanam, I., & Sacks, G. (2016). Analysis of the corporate political activity of major food industry actors in Fiji. Globalization and Health, 12, 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-016-0158-8

- Militão, E. (2019). Contra obesidade, Ministério da Saúde quer encarecer refrigerantes. Polítca, UOL Noticias. Retrieved December 18, 2020, from https://noticias.uol.com.br/politica/ultimas-noticias/2019/01/26/obesidade-ministerio-saude-encarecer-imposto-refrigerantes-acucar.htm

- Monteiro, C., & Cannon, G. (2017). The impact of transnational ‘Big Food’ companies on the South: A view from Brazil. PLoS Medicine, 9(7), e1001252. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001252

- Motta, C. (2020). Lula, sobre programas de combate á fome: tanto tempo para construer, tão fácil destruir. Rede Brasil Atual. Retrieved December 18, 2020, from https://www.redebrasilatual.com.br/cidadania/2020/10/lula-programas-combate-a-fome-tanto-tempo-construir-tao-facil-destruir/

- Mugnatto, S. (2018). Aumento da tributação para bebidas açucaradas não é consenso em comissão. Câmara dos Deputados. https://www.camara.leg.br/noticias/549626-aumento-da-tributacao-para-bebidas-acucaradas-nao-e-consenso-em-comissao/

- Nilson, E. A. F. (2015). The strides to reduce salt intake in Brazil: Have we done enough? Cardiovascular Diagnosis and Therapy, 5(3), 243–247. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2223-3652.2015.04.03

- Nutrição em Pauta. (2008). Fundação Nestlé anuncia os dez projetos sociais contemplados pela promoção ‘Nestlé Torce Por Você’. https://www.nutricaoempauta.com.br/noticias/noticias110.html

- O’Connor, A. (2015, August 9). Coca-Cola fund scientists who shift blame for obesity away from bad diets. The New York Times.

- Ojeda, E., Torres, C., Carriedo, Á, Mialon, M., Parekh, N., & Orozco, E. (2020). The influence of the sugar-sweetened beverage industry on public policies in Mexico. International Journal of Public Health, 65(7), 1037–1044. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-020-01414-2

- Oliveira, M. S. S., & da Silva Santos, L. A. (2020). Guias alimentares para a população Brasileira: Uma análise a partir das dimensões cultrais e sociais da alimentação. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 25(7), 2519–2528. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232020257.22322018

- O’Neil, S. (2013). Campaign financing in Mexico. Council on Foreign Relations.

- Peres, J. (2017). Alimentos: O ‘manual’ da indústria para frear a regulação na América Latina. O Joio e o Trigo. Retrieved April 21, 2021, from http://ojoioeotrigo.hospedagemdesites.ws/2017/12/alimentos-o-manual-da-industria-para-frear-regulacao-na-america-latina/

- Peres, J. (2018). Crescem reações á relação entre ciência e indústria de ultraprocessados. O Joio e o Trigo. Retrieved August 27, 2019, from https://ojoioeotrigo.com.br/2018/02/crescem-reacoes-relacao-entre-ciencia-e-industria-de-ultraprocessados/

- Processo. (2008). Obesidad, corrupción, y complicidad oficial. Retrieved August 11, 2018, from https://www.proceso.com.mx/89928/obesidad-corrupcion-y-complicidad-oficial

- Reeve, B., & Gostin, L. (2019). Big food, tobacco, and alcohol: Reducing industry influence on noncommunicable disease prevention laws and policies. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 8(7), 450–454. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2019.30

- Revista ABIR. (2019). Brasil é o 2 maior mercado de bebidas não alcoólicas. Retrieved August 28, 2019, from https://abir.org.br/abir/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/REVISTA-ABIR2019.pdf

- Rosenberg, T. (2015, November 3). How one of the most obese countries on earth took on the soda giants. The Guardian.

- Savell, E., Gilmore, A., & Fooks, G. (2014). How does the tobacco industry attempt to influence marketing regulations? A systematic review. PLoS One, 9(2), e87389. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087389

- Secretaria de Salud. (2010). Acuerdo Nacional para la Salud Alimentaria Estrategia contra el Sobrepeso y la Obesidad. Secretaría de Salud.

- Secretaria Geral. (2017). Conflito de interesses: indústria de alimentos ocupa espaços da universidade na Anvisa. Amestro-SN. https://asmetro.org.br/portalsn/2017/11/27/conflito-de-interesses-industria-de-alimentos-ocupa-espacos-da-universidade-na-anvisa/

- Swinburn, B. (2008). Obesity prevention: The role of policies, laws and regulations. Australia and New Zealand Health Policy, 5, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-8462-5-12

- Tangcharoensathien, V., Chandrasiri, O., Kunpeuk, W., Markchang, K., & Pangkariya, N. (2019). Addressing NCDs: Challenges from industry market promotion and interferences. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 8(5), 256–260. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2019.02

- Tanrikulu, H., Neri, D., Robertson, A., & Mialon, M. (2020). Corporate political activity of the baby food industry: The example of Nestlé in the United States of America. International Breastfeeding Journal, 15, 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-020-00268-x

- Taylor, A. L., & Jacobson, M. F. (2016). Carbonating the world. Centre for Science in the Public Interest.

- Terra, T. (2009). Nestlé bate na porta do consumidor para vender na base da pirîmide. Mundo do Marketing. https://www.mundodomarketing.com.br/entrevistas/12123/nestle-bate-na-porta-do-consumidor-para-vender-na-base-da-piramide.html

- Troyano, M. C., & Martín, R. D. (2017). Poverty reduction in Brazil and Mexico: Growth, inequality, and public policies. Revista de Economía Mundial, 45, 23–42.

- Vasconcelos, F. A. G. (2005). Combate á fome no Brasil: uma análise histórica de Vargas a Lula. Revista de Nutrição, 18(4), 439–457. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1415-52732005000400001

- Vendrame, A., & Pinsky, I. (2010). Ineficácia da autorregulamentação das propagandas de bebidas alcoólicas: Uma revisão sistemática da literature internacional. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 33(2), 196–202. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1516-44462011005000017

- Verstraeten, R., Roberfroid, D., Lachat, C., Leroy, J., Holdsworth, M., Maes, L., & Kolsteren, P. (2012). Effectiveness of preventative school-based obesity interventions in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 96(2), 415–438. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.112.035378

- Villafranco, G. (2016). Impuesto a refrescos no redujo consumo, pero recuadó 38,000 mdp. Forbes. Retrieved February 20, 2019, from https://www.forbes.com.mx/impuesto-a-refrescos-no-redujo-consumo-pero-recaudo-38000-mdp/

- Vogel, D. (2008). Private global business regulation. Annual Review of Political Science, 11(1), 261–282. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.053106.141706

- Weissheimer, M. (2017). Conflitos de interesse: JBS financiou 36% da atual bancada do Congresso Nacional. Brasil de Fato. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- Whitehead, R., Watson, E., Chu, W., Michail, N., Gore-Langton, L., & Arthur, R. (2016). The year of the sugar tax. BeverageDaily.com. https://www.beveragedaily.com/Article/2016/12/15/2016-The-year-of-the-sugar-tax