ABSTRACT

In two co-related studies about Two-spirit people in Atlantic Canada, the coming out stories share critical cultural perspectives about gender identity and sexuality from a L'nuwey (Mi'kmaw) perspective. This qualitative research implemented Etuaptmumk or Two-Eyed Seeing, a co-learning methodology using Indigenous and western perspectives for data collection and analysis. The findings surface stories about resiliency among Two-spirit people who face distress and anxiety, with supports mainly coming from family and community. According to their narratives, coming out is part of their cultural awakening process. The paper shares that Two-spirited people come out in intervals or phases, especially trans people. Sexuality and gender identity development are in flux until they reach a balanced and spiritual state. The Two-spirit identity process is non-linear that may evolve in a life cycle. The study captures the ongoing resurgence of regional Indigenous perspectives of gender identity and sexuality. The narratives share the physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual states of Two-spirit people during their coming out process. The stories are a source of hope and empowerment for the Two-spirit community relating to gender and sexuality. This study is the only current community-based evidence about coming out experiences of Two-spirit people in Atlantic Canada.

Introduction

In 2008 and 2009, ten people died because of suicide in my home reserve. The community rallied to understand what happened – it was considered a health crisis. It was discovered that four of the then people who died were Two-spirit people. There was no evidence to understand what had happened, except that families of the dead young people said that their loved ones were not out as Two-spirit people. It was precisely at that moment that I wanted to learn more about Two-spirit identity, which eventually led me to research the coming out process for Two-spirit people from our cultural perspective.

This paper comes from research exploring Two-spirit stories and narratives about the coming out process, written by a Two-spirit Mi'kmaw person for Two-spirit people of Atlantic Canada. The generous nature of Two-spirit people is the central theme of this paper. It is about Two-spirit stories and narratives and how Two-spirit people come to terms with their gender identity and sexuality as part of a life cycle. Most importantly, it is the first time the Two-spirit coming out process has been explored and analyzed by integrating Mi'kmaw perspectives.

Two-spirit influencers and warriors

I refer to Two-spirit people as warriors. Two-spirit authors and their perspectives are imprinted throughout this paper. I refer to them as Two-spirit influencers and mentors. Dr. Margaret Robinson, L'nu from Lennox Island, has influenced the understanding of Two-spirit experiences from a bisexual perspective. Dr. Robinson's integration of health and identity is critical to understanding wellness (Robinson, Citation2014, Citation2019). Tuma Young, a L'nu scholar, shares L'nuwitasimk (Young, Citation2016), Mi'kmaw perspectives from a legal perspective, which is translatable knowledge about the cycle of life as a process for coming out. Young's content is the core of L'nuwey worldview in the paper.

There are other Two-spirit academics from other parts of Canada who radically opened my eyes to Two-spirit perspectives. Dr. Alex Wilson, a Cree scholar, directly influenced the Two-spirit conceptualisation about how gender, sexuality and spirituality emerge together as a Two-spirit identity. Dr. Albert McLeod, a Nisichawayashik Cree, shares knowledge using oral tradition and the importance of Two-spirit positionality as activists, knowledge-keepers, and Elders (Lezard et al., Citation2021). He is a strong advocate of the Two-spirit oral tradition for knowledge development. Another notable Two-spirit activist is Percy Lezard, a Sqilxw scholar and researcher, who shares intersectionality perspectives, including disability and anti-racism, and creates a healing culture (Laslet, Citation2020) in research.

Two-spirit: being and living

Nin na L'nu. I am Mi'kmaq and a Two-spiritFootnote1 person from the Millbrook First NationsFootnote2 in Nova Scotia. Also, I am an educator, researcher, activist, and knowledge-seeker. One of the roles as a Two-spirit person is implementing and seeking knowledge to respond to our people's challenges in a world of rapid flux. According to our L'nuweyFootnote3 worldview, identity is an evolving process physically, emotionally, mentally and spiritually throughout one's life (Sylliboy, Citation2019).

Content development and background

The paper's content, data, and findings are excerpts from the report ‘Coming Out Stories: Two-spirit Narratives in Atlantic Canada’ (Sylliboy, Citation2017a), which is this paper's principal source. However, only the data that relates to the topic about the coming out process as a life cycle will be explored in this paper. The report's content also provided data for my master's thesis called ‘Two-spirits: Conceptualisation in a L'nuwey Worldview’ (Sylliboy, Citation2017b), and its consequent chapter publication, also an excerpt called ‘Using L'nuwey Worldview to Conceptualise Two-spirit’ (Sylliboy, Citation2019). The culmination of the report and the thesis findings are the sources for understanding the coming out cycle for Two-spirit people. Community validation about the coming out process came from the first report's advisory circle, which consisted of three Elders and two knowledge-keepers. It was further validated when I defended my thesis in front of 25 Elders in Membertou First Nation in October 2017.

Conceptualising two-spirit from a L'nuwey worldview

One of the outcomes of the paper is a conceptualisation of Two-spirit from a L'nuwey worldview. The term includes gender expressions of identity and sexuality; they are related concepts and overlapping but not necessarily situated as a strict male-female binary, or sexual orientation. Being Two-spirited recognises the fluid nature of gender in singular, dual or plural states of expression, which may or may not intersect with sexuality. The Missing & Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls & Two-spirit people (MMIWG2S) Sub-working Group offers a definition as the ‘term may also be used interchangeably to express one's sexuality, gender, and spirituality as separate terms for each or together as an interrelated identity that captures the wholeness of their gender and sexuality … ’ (Lezard et al., Citation2021, p. 8). The term recognises the inherent and derivative link between ‘historical, cultural and spiritual contexts that constitute identity’ (Sylliboy, Citation2017b, p. 97). Further conceptual analysis of Two-spirit is in the forthcoming sections.

Two-spirit, a pan-Indigenous term, is most often used without culturally specific terms among Nations. Some Indigenous groups may have specific terms that are not easily interpreted as English terms or classifications because they derive from Indigenous socialisation of gender and sexuality (Lezard et al., Citation2021; Sylliboy, Citation2017b). The impacts of colonialism, patriarchy and heteronormative policies have impacted cultural knowledge about gender and sexuality, resulting in erasure of Two-spirit content (Lezard et al., Citation2021).

There are no exact translatable terms for Two-spirit among the Mi'kmaq, Wolastoqiyik, Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Abenaki, and the Inuit people, which make up the Wabanaki region (Sylliboy, Citation2017a). These Nations shared that Two-spirit identity has always existed in Wabanaki Nations. There is an interconnectedness among the Nations; those Nations’ Elders supported the first study and my thesis findings. Indigenous People share socio-historical experiences through kinship or inter-relatedness in the Wabanaki region, part of the L'nuwey worldview (Young, Citation2016). The inter-relatedness may transcend into a pan-Indigenous practice among various Indigenous groups in a shared ecological space, or territory bound by treaties or alliances that Young refers to as ‘the great circle of friendship’ (Young, p. 99). That is the foundational approach in addressing issues among the Wabanaki region and the impetus for a community-based study.

The term Two-spirit resonates among Wabanaki Nations because the concept of ‘Two-spiritedness’ of sexuality and gender identity is active within their collective consciousness despite the absence of specific terms or words in their languages. Wabanaki Elders and knowledge-keepers shared that sense of familiarity when consulted about this research project. When one specific language group like the Mi'kmaq researches Two-spirit content, the study's findings are often relatable with other Wabanaki Nations, especially between the Mi'kmaq and Wolastoqiyik that are linked through regional tribal or cultural similatires and closely related languages. However, this study only captured limited data about Labrador's Inuit perspectives, and there were no self-identified Innu participants in the study. Therefore, all the Wabanaki perspectives are not entirely relatable because of the two groups’ lack of data.

Why do you need to study about two-spirits?

I shared previously that ten people committed suicide in my home community; four were Two-spirited people (IODE, Citation2016) between 2008 and 2009. Community members concerned about Two-spirited youths’ wellbeing reached out to Tuma Young, a highly respected Two-spirit activist and academic, to express their concerns. The community families suspected that their loved ones suffered from low self-acceptance as Two-spirited young adults. They also disclosed that the victims struggled with mental health and addictions, which they believed may have been part of the cause of their suicide.

In 2008, I had recently self-identified as a Two-spirit person. At the time, I worked in health policy, and Tuma contacted me about the suicide crisis. We agreed that hosting a Two-spirit gathering was the best course to address the urgency as a collective. According to Meyer-Cook and Labelle (Citation2004), gatherings provide a safe space for Two-spirit people to be with others of the same community where mutual empowerment is part of collective healing, especially for people dealing with trauma or cultural isolation. The healing takes place when Two-spirit people get together, which acts as reverse isolation, especially for those people who suffer from loneliness and feeling isolated (p. 46).

As the first call to action, Tuma and I co-founded the Wabanaki Two-spirit Alliance (W2SA) in 2010 as the regional support group. In 2011, the Alliance received funding from the National Aboriginal Youth Suicide Prevention Strategy (NAYSPS), Health Canada, to host a regional Two-spirit gathering. Additional resources came from the Atlantic Aboriginal Health Research Program (AAHRP) to fund the gathering's research consultation portion. Between 2011–2013, the Alliance hosted more gatherings to consult on research priorities and to conduct assessment of needs. In 2014, I applied for a research grant from the Urban Aboriginal Knowledge Network (UAKN) for the Alliance's coming out study and my thesis research.

Review of two-spirit content in Atlantic Canada

Part of my master's research was to review literature about the concept of Two-spirit and related Indigenous LGBTQQIA+ content to identify gaps and review existing sources in Canada and the United States. The review confirmed a dearth of publications from the Atlantic region (Sylliboy, Citation2017a). On the positive side, there is a growing number of Indigenous and Two-spirit writers that are expanding the understanding of Two-spirit perspectives in the last two decades offering Indigenous perspectives about being Two-spirit — but none from a L'nuwey perspective analyzing the coming out process.

Two-spirit data about mental health is scarce. There is a lack of data collected in Canada in general; for example, there is an undercount in suicides among gay and bisexuals based on autopsy studies (Hottes et al., Citation2015). This information is relevant because it speaks to the four suicides of our community. We only knew about the deaths from family and friends who reached out; otherwise, those numbers would have been uncounted statistics. Other studies indicate that Indigenous people face disproportionately high levels of chronic mental health conditions (Hunt, Citation2016; John-Henderson & Ginty, Citation2020) that are linked to systemic oppression(s) (Goha et al., Citation2021). The precarious condition faced by Indigenous people is further exasperated by the intersection of racism with homophobia and transphobia among the Two-spirit community.

Research indicates inequities among sexual and gender minorities (SGM) with increased mental health risks, like depression and suicide (Ferlatte et al., Citation2020). Researchers acknowledge the limitations of policies that target Two-spirit people because they are categorised together with the general SGM group causing erasure of Two-spirit specific health needs. Openly living Two-spirit people face challenges in their home reserves and urban centres (Assembly of First Nations National Youth Council, Citation2016; TASSC, Citation2013). Two-spirited youth often suffer from mental health distress caused by stigmatised sexual identities (Government of Canada, Citation2017; Ryan & Canadian AIDS Society, Citation2003; Toomey, Citation2010), leading to suicide (Evans-Campbell, Citation2012; Health Canada, Citation2016; Hill, Citation2003). Even though the objective is to share strength-based research, it is critical to understand potential correlations from this study's findings with existing data. The implications for not having evidence-based data about Atlantic Two-spirit people puts the W2SA organisation at a disadvantage for lobbying services or developing health policies. More specific data about the rate of suicide among Two-spirit people was an identified gap in research.

Two-spirits: impacted by contemporary residue of colonialism

According to the Assembly of First Nations National Youth Council (Assembly of First Nations National Youth Council, Citation2016), Indigenous youth who identify as Two-spirited or other terms under the acronym 2SLGBTQQIA+Footnote4 suffer social oppression, transphobia and homophobia in Canada due to a lack of cultural acceptance and negative cultural identity because of their gender and sexuality (Ryan & Canadian AIDS Society, Citation2003). Intergenerational trauma from Indian Residential Schools (Bombay et al., Citation2014; Castleden et al., Citation2012; Linklater, Citation2014), the imposition of Christianity (Battiste, Citation1998), and a correlation of outcomes have directly affected Indigenous people who identify as Two-spirited.

Two-spirited people, once revered as leaders, healers, and knowledge-keepers in their communities (Brown, Citation1997; Cromwell, Citation1997; Gilley, Citation2006; Roscoe, Citation1998; Williams, Citation1986), suffered persecution and cultural displacement from colonisation in Canada (Government of Canada, Citation2017). Indigenous communities adopted stringent binary, heteronormative policies (Canon, Citation1998), and the imposition of the Indian Act and colonialism impacted Two-spirits’ (Robinson, Citation2019) cultural perspectives because of colonial paradigms (Wilton, Citation2000) that redefined gender roles in Indigenous society. Studies have illustrated the deleterious effects of colonialism (Reading & Wien, Citation2009); for instance, the rate of suicide among the broader populations of Indigenous nations is five to seven times higher than it is in the mainstream Canadian population (Health Canada, Citation2016; Kirmayer et al., Citation2007). The rates have remained constant in 30 years (Yuen et al., Citation2019).

Two-spirits identify sharing of coming out stories as a healing journey

In the Two-spirit gathering of 2011, the Sharing Circle's dominant theme was how Two-spirit participants described the sharing of coming out stories as medicine, which Indigenous scholars consider storytelling as part of a healing process (Hodge et al., Citation2002; Smylie et al., Citation2014). The impetus in using Two-spirits’ stories as a data-gathering method is to link research and healing (Smylie et al., Citation2014). The authors share that ‘stories themselves can be perceived as holding ‘medicine’ and the act of sharing stories as acts of healing’ (p. 3). Two-spirit Elders and knowledge-keepers’ suggestion to move away from deficit-based research and implement a strength-based approach (Ranahan et al., Citation2017) is a deliberate act of decolonisation.

Another emerging theme from the Sharing Circle was how people survived and celebrated their lives as Two-spirits after coming to terms with their sexuality and gender identity. The Circle evolved naturally into a ceremonial healing process. At least 50 per cent of Two-spirit attendees shared how they coped with suicidal ideation or attempts (Wabanaki Two-spirit Alliance, Citation2011). Elders and support people were present in case of triggers or distress. On the last day, the participants shared their final thoughts and ideas for research and policies. They recommended gathering stories about Two-spirits’ coming out experiences because they felt it was part of a healing journey to share their stories. They wanted to celebrate Two-spirits identity using storytelling, especially for Indigenous youth facing similar challenges, as a strategy of life promotion (Yuen et al., Citation2019).

It was mentioned before that there was next to no data about the suicides caused by homophobia, bullying, or lack of health supports for youth who suffered challenges with gender and sexuality in Atlantic Indigenous communities (Sylliboy, Citation2017a). The relevant information was from the oral tradition shared by families and community members after the suicide crisis in the community. The families warned of possible correlations between suicide, substance use disorders, and challenges youth face with their self-identity as Two-Spirited people. The community was alarmed that 40 per cent of the deaths were Two-spirited young adults under 25 (Wabanaki Two-spirit Alliance, Citation2011). It was evident from the Sharing Circle and families’ input that oral tradition should be implemented in Two-spirit research. The research methodology emerged, and the participants recommended using Etuaptmumk or Two-Eyed Seeing (E/TES) as a research framework because of its Mi'kmaw foundations for knowledge gathering.

Research ethics and design

Through its Mi'kmaw Ethics Watch, Cape Breton University approved the research project with the Mi'kmaw community. As the P.I. doing my master's, I went through my university ethics board at Mount Saint Vincent University. The research study adhered to the Tri-Council Policy Statement on Research with Indigenous People (Chapter 9) (Government of Canada, Citation2018) and implemented the principles of the OCAP (Ownership, Control, Access, Possession) (First Nations Information Governance Centre, Citation2020) as the overarching ethical guidelines.

I established a Two-spirit Advisory Circle consisting of two Elders, two knowledge-keepers, and a senior mentor to guide the research process. The senior researcher advised on the proper research protocols from a Wabanaki perspective. The advisory circle guided the whole research process. I had regular meetings with the mentor and the advisory circle to provide updates. As previously mentioned, the idea to gather coming out narratives for research was a recommendation from the Two-spirit gatherings in 2011, 2012 and at the International Two-spirit Gathering in Madawaska First Nation in New Brunswick in 2013.

Participation in interviews and surveys

We recruited Two-spirit participants by targeting members of the Wabanaki Two-spirit Alliance via social media networks (Facebook and Twitter). It also posted calls for research participants on targeted Facebook groups and friendship centres, community health centres, and On-Reserve websites in the Atlantic region. The participants all volunteered freely and were compensated for their time with gift cards. As for the survey, we posted the online survey with clear instructions that it was for participants who identify as Two-spirit, or terms under the acronym 2SLGBTQ (acronym used in 2017 by the Alliance). The Alliance confirmed the anonymity of the participants, principal investigator, and the transcriptionists sign confidentiality forms. I shared the anonymous online surveys link to the members of the Alliance (500+ members during that time) and the previously mentioned sites.

Etuaptmumk/two-eyed seeing framework

The qualitative study is a community-based, community-led study using mixed methods with guided interviews (n=20) with demographic and self-reported health forms and online survey responses (n=70) for data gathering guided by Etuaptmumk/Two-Eyed Seeing (E/TES) framework (ACHH Initiative, Citation2017; Hall et al., Citation2017; Hovey et al., Citation2017; Iwama et al., Citation2009; Martin, Citation2012; Sylliboy & Hovey, Citation2020). E/TES brings together different ways of knowing from the strengths of Indigenous and non-Indigenous perspectives in a co-learning and integrative process. Elders Albert and Murdena Marshall coined the term ‘Two-Eyed Seeing’ and shared that the importance of conducting research is understanding that our knowledge is authentic, sacred, and spiritual (ACHH Initiative, Citation2017). Each eye symbolically represents each perspective's strengths (Bartlett et al., Citation2012).

Stories heal us

The participants’ stories or narratives are the primary sources of data, and they are the source of Indigenous knowledge development and translation (Battiste, Citation2009; Bear, Citation2009; Kovach, Citation2009). Analysis from Two-spirit participants’ perspectives provides a holistic perspective of the Two-spirit coming out process using the E/TES approach. Gathering stories as a method to build knowledge about Two-spirits’ lived experiences resembles the way Indigenous people often transmit knowledge culturally. Naturally, the research advisory circle of Elders and knowledge-keepers recommended this method for the coming out stories study.

The participants’ coming out stories are critical voices embedded with lived experiences, and they are core components of knowledge development through Indigenous research (Battiste, Citation2009; Kovach, Citation2009; Smith, Citation2009; Wilson, Citation2008). It was indispensable to implement a meaningful and relational method to respectfully discuss the lived experiences from which themes about anxiety, distress, depression, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts surfaced without retriggering undue mental, emotional, spiritual, or physical stress during the interviews. Great care was taken to avoid direct and indirect questions about suicide and suicide ideation as a trauma-informed approach. It is also crucial to comprehend that coming out is a cultural journey for many Two-spirit people, directly relating to Marshall's point about research as a spiritual process for its participants. We come back to the idea that coming into or discovering one's identity as a Two-spirit person (Wilson, Citation1996) is process that involves physical, mental, emotional and spiritual realms of identity maturation and coming into Two-spiritedness (Sylliboy, Citation2019).

Affirming kinship and swapping stories

Etuaptmumk/Two-Eyed Seeing (E/TES) enables the interview process to be more cultural-like because it emulates a relational interaction between community members while storytelling. While the western approach for interviewing has goals to engage the participants by employing set strategies that maintain a sterile and objective setting, E/TES comes from kinship and relationship building (Sylliboy et al., Citation2021) that allows a natural conversation setting for the storytelling process. E/TES integrates the standards of western-based methods for data collection while maintaining the cultural tradition of kinship and building trust to establish a safe space (Latimer et al., Citation2018). I established trust by swapping personal stories with the interviewees (n = 20). It was to establish mutual positionality and accountability that eventually led to storytelling in a culturally meaningful way. The engagements were in the interviewee's selected safe place. The E/TES approach considers cultural protocols for adequate time for interaction, kinship exploration, and story-swapping, so it was not too time-restricted or clinical.

Additionally, exchanging stories is a process of inter-relationality (Smylie et al., Citation2014) between the interviewer and interviewee to respect the spiritual process of knowledge sharing as a collective action. Sharing or exchanging stories is similar to sharing ‘tea’ (Castleden et al., Citation2012; Iwama et al., Citation2009). It prepares the space for knowledge interaction. Applying the proper social-cultural protocol is essential, such as having that time for tea and storytelling, especially when interviewing Elders.

The stories were autobiographical, whereby each participant's shared lived experience was a process of composing annals and chronicles (Clandinin & Connelly, Citation2000). According to Laslet, ‘individual life stories are very much embedded in social relationships and structures and they are expressed in culturally specific forms; read carefully, they provide unique insights into the connections between individual life trajectories and collective forces and institutions beyond the individual’ (Laslet, Citation2008, p. 3). The collection of stories shared emerging processes, which the participants mentioned as part of their life cycle.

The questions for the interview guide were developed to prompt storytelling while maintaining a sense of purpose, gathering data. The interviewer recognises that stories are lived experiences and, when shared, have an added dimension of connectivity between the participants. Two-spirited voices transform into a L'nuwey/Indigenous/collective consciousness (Iwama et al., Citation2009); therefore, each story has a spiritual tense for healing through language that evolves into collective knowledge of that group. Many of the stories mention spirituality as part of their reawakening of cultural identity interests; it is when the discussions ended on a high note. In order to lift the spirits of the interviewees, the interviewer maintains the cycle approach by organising the mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual questioning according to themes to make sure that the interviewee feels that they are making a difference by providing their perspective in the research or project at hand. I ask strength-based questions at the end of the interview, focus group, or talking circle to end on a positive note.

Coming out stories are traditional storytelling

Reliving stories is an essential component of knowledge translation (Battiste, Citation2009; Kovach, Citation2009). Storytelling is a source of empowerment and transformative knowledge based on experience (Dworkin, Citation1959). The stories have a spiritedness that can be complex because of their multidimensionality. Stories are three-dimensional, concerning time, space, and personal/social settings (Clandinin & Connelly, Citation2000). That was the case in the study, as each Two-spirit participant regressed in memory to the point of time to share their experience about coming out. They recalled the associated emotions and experiences they felt during their coming out, such as distress, anxiety, or relief. They retold their narratives in the present tense, which often resurfaced sensitive emotions. During the whole process, the participant was reactivating their lived experience. The stories are relived in the same intensity as those told during storytelling sessions by Elders or knowledge-keepers; therefore, they could be considered part of traditional storytelling in a contemporary setting.

Elder Murdena Marshall shares her wisdom when stating that ‘As Indigenous people whose connectiveness with our cultures and those who enliven them has been damaged, we are learning to integrate that which is withheld and devalued’ (Iwama et al., Citation2009, p. 15). According to Elder Murdena, it is vital to understand that the stories are about hope and resilience, and their healing essence remains intact by using stories. The stories offer a sense of a cultural or spiritual connectiveness (Iwama et al., Citation2009) between all the elements that make up the research- like the researcher, research team, collaborators, and participants in the study. It is an acknowledgement of centreing the research in Indigenous worldviews.

Analysis of findings using medicine wheel or four directions model

The advisory circle committee directed the development of the survey, interview questions, and data analysis using the Four Directions Model or Medicine Wheel. The questions did not include words like suicide ideation or suicide. The questions aligned with the Medicine Wheel teaching (Doucette et al., Citation2004; Fiedeldey-Van Dijk et al., Citation2017). The four quadrants represent the holistic nature of wellbeing as emotional, physical, mental and spiritual. The transcriptions in verbatim were coded to analyze types of supports under the same four headings. In the analysis process, the stories were maintained as a collective unit of stories, rather than sharing individual participant's experiences. One reason is to honour the stories as a collective, which keeps the integrity of the stories’ spirit, and more importantly to maintain the spirit of the collective consciousness of Two-spirited participants. The other reason is to maintain the stories’ theme of coming out as a whole thread, rather than disintegrating the stories into individual parts for analysis and coding, which can be viewed as disrespectful for the sake of research (Simonds & Christopher, Citation2013). I purposely did not include individual statements to maintain and respect the anonymity of the participants in the study.

The stories or narratives (n = 20) provide a comprehensive interpretation of the coming out process for Two-spirit people. The terms, phrases, and words that describe the coming out process, including the ways of coping, and terms for emotions, feelings, and experiences, were coded using the Four Directions model (Fiedeldey-Van Dijk et al., Citation2017). The model allows categorising the terms under four quadrants that capture emotional, physical, mental, and spiritual dimensions for coming out. The terms were coded based on the goal of the question. For example, as the P.I., I coded terms for the coming out process under each heading, which helped identify such characteristics as processes/stages, time, emotions, and coping mechanisms for Two-spirited people during their coming out experiences. In the coming out study, I used the same model as the one I had used in pediatric pain research to analyze the narratives and art expressions by Indigenous children and youth to express their pain experiences in Atlantic Canada (Latimer et al., Citation2018).

In analyzing the data, intricate details surfaced about the coming out process and its deep sense of kinship linked to tribal consciousness (Marshall, Citation2005) about survival, especially those who faced suicide ideation and even suicide attempts. According to Brown (Citation2011), coming out stories can be analyzed using an intersectional framework concerning class, gender, and race. A critical consideration using narrative analysis is how the stories were told from Two-spirit participants as actors who lived through those emotions and experiences. A cross-sectional analysis of self-reported experiences using demographic forms and the surveys provided a more in-depth understanding of the intersectionality of Two-spirit peoples’ experiences. That information included self-reported mental health and wellbeing and the degree to which Two-spirit people live openly as ‘Two-spirited’ in their immediate settings. The limitation of the survey was that the findings did not provide a cross-sectional perspective about the coming out process to the same degree as the individual interviews.

There were stories of bouts with substance use disorders, self-harm, feelings of displacement, fear of rejection from the community, and fear of not being loved by their families in their home communities. Many participants shared how they moved into urban centres, like Halifax, Moncton, and Fredericton or as far as Montreal and Toronto, to live more openly as Two-spirit people. They tried to balance their ‘closeted’ lives in their home communities while being ‘out’ in urban centres. The flux between the reserve and urban life was disruptive and stressful, but many had no alternative.

The analysis provides a wealth of understanding of what coming out (Brown, Citation2011) is for Atlantic Two-spirited people. The stories capture dimensions of how social, cultural, and environmental contexts play a role in determining what it is to be a Two-spirited person (Robinson, Citation2019). The personal stories as narratives are a potent source of framing historical, cultural, temporal, and spatial realities from an individual's lived experiences (Maynes, Citation2008) based on a L'nuwey worldview.

Meaningful research about two-spirit people

Indigenous youth who identify as Two-spirited face an intersection of discrimination because of homophobia on their reserves, and they often deal with racism outside of the community. In turn, the lack of language to self-identify and cultural understanding about Two-spirit identity contributes to their cultural erosion, thus increasing the risk of suicide among the youth (Chandler & Lalonde, Citation1998). As an emerging L'nu researcher, I recognise the vulnerability of Two-spirited people and the sensitivity of the correlated themes. There is a potential for misinterpretation of findings, so I avoid further stigmatising Two-spirited and Indigenous people by selecting data that is relevant to the paper. However, I share the lived experiences of trans people because it is directly related to the coming out process.

Self-identification of participants for the guide interviews

The participants used English terms to self-identify as the following: Two-spirit (7/20 = 35 per cent), Gay (7/20 = 35 per cent), Trans (4/20 = 20 per cent), Bisexual (3/20 = 15 per cent), Lesbian (2/20 = 10 per cent), Pansexual (2/20 = 10 per cent), Queer + (1/20 = 5 per cent). The total sum does not exactly equal 100 per cent because some self-identified with more than one label. For example, 15 participants self-identified using one term, two participants self-identified using two terms, and three participants self-identified using three terms. One of the questions was to provide terms or words to self-identify in their respective languages, which resulted in no identified terms of the Atlantic region. The following results are self-reported cases from the stories of four out of 20 (20 per cent) participants.

Two-spirit – trans participants

Four out of 20 or 20 percent (4/20 = 20 per cent) of the participants self-identified as trans people for the guided interviews. There was an equal number of trans males (2/4 = 50 per cent) and trans females (2/4 = 50 per cent) in the study. While the total number of participants is low, the stories are the most relevant evidence about trans peoples’ experiences in the Atlantic region. I reiterate that a simple statistical breakdown demonstrates the importance of continuing research with larger targeted populations in Canada's other regions to gain a broader perspective.

Narratives offer findings of coming out process

The research advisory circle interpreted the data as essential community-based evidence to lobby for services and policies for Two-spirit people in Atlantic Canada. For example, trans people require more culturally appropriate and culturally safe mental health supports. The findings demonstrate that trans people face unique challenges in their gender-affirming process.

According to our study, trans people come out more than once, sometimes on three or more occasions. Their stories talked about dealing with gender dysphoria as the leading cause of their anxiety, distress and depression. Two-spirit participants shared their experiences in confusing gender identity with sexuality, which they recognised as the primary cause of their mental health distress. In all four trans shared lived experiences, the individuals believed that they were gay or bisexual during their early adolescent years. As time progressed, their mental health deteriorated because they became increasingly aware that it was not their sexuality but their gender that was not balanced or aligned with their real inner and outer spirits.

The experiences of Two-spirit /trans individuals coincide with the flux explanation outlined in my master's thesis, which is explained further in the paper. The experiences by Two-spirit participants shared that their gender identities were in a continuous flux during their lifetime until they matured into their balanced state. The Two-spirits’ narratives motivated me to explore the state of flux perspective further—their stories about coming out were critical components in understanding the coming out process from a L'nuwey worldview.

L'nuwey worldview and the cycle of life

I analyzed various Mi'kmaw, or Indigenous perspectives by Dr. Marie Battiste, Tuma Young, Sakej Henderson, Dr. Margaret Robinson, and Elders Albert Marshall and Murdena Marshall to conceptualise our worldview. I explored how kinship, the interconnectedness of spirits, and the state of flux to explain the Two-spirit coming out process.

The description of the L'nuwey worldview summarises the original text from the thesis (Sylliboy, Citation2017b), an excerpt about L'nuwey worldview and its relation to coming out that was later published (Sylliboy, Citation2019). The dominant thread among the authors is that the Mi'kmaw worldview directly relates to the cycle of life, whereby the natural order of life binds all spirits, plants, animals, and humans within an ecosystem. The idea is that all spirits within that ecosystem are interdependent and interconnected to maintain a balance in that realm. The outcome is that the spirits of all living things are in flux within the system to achieve that balance. I analyzed Mi'kmaw perspectives about the cycle of life and gender and sexuality perspectives derived from various publications about Two-spirit content to develop a conceptual framework that further explores that coming out process from our cultural perspectives.

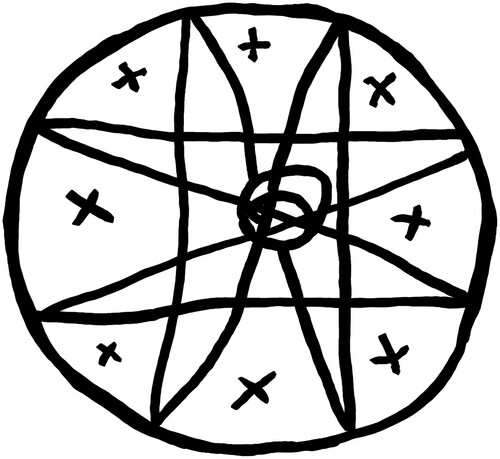

Kloqowej: Mi'kmaw star and relations of being mi'kmaq

I explored the origins of our worldview concerning the Mi'kmaw star (), which is the source of the cycle of life perspectives for Mi'kmaw teachings. I used Tuma Young's interpretation of the Mi'kmaw star or Kloqowej to understand the cycle of life about how people relate to each other (Young, Citation2016). Essentially, the star represents how the spirits are bound to each other in kinship within Mi'kma'ki, our ancestral territory, to establish a sense of relations as a collective. The diagram represents the eight Mi'kmaw districts of Mi'kma'ki, with the ‘+’ or the cross representing each district. They are bound together by a system, the natural order of life. The districts are connected and intersect in the centre – the primary cultural way of being, doing and knowing unites the districts. They follow cultural protocols that regulate their relations among the people and all living things. Their relations are part of the natural order within the confines of their ecosystem (the circular outer boundary that represents the Mi'kmaw territory).

Figure 1. Kloqowej or Mi'kmaw star Courtesy of the Nova Scotia Museum, Ethnology Collection (Young, Citation2016, p. 99).

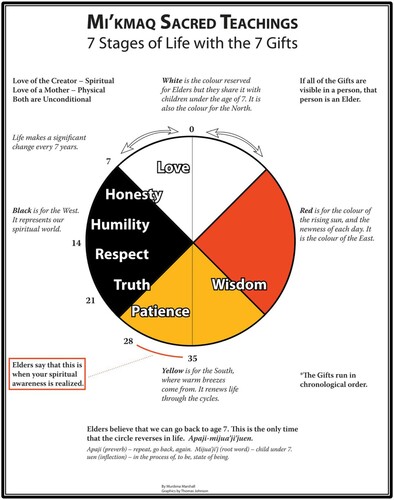

Mi'kmaq seven sacred teachings: 7 stages of life with 7 gifts

The advisory circle recommended that I implement the Mi'kmaw teachings to explain the coming out process while integrating our worldview perspectives. The advisory circle understood the complexity of developing a visual representation for coming out, yet it was clear how the process circularly evolved in peoples’ lives. Therefore, I agreed to use Elder Murdena's diagram () as a visual source because it incorporated the breakdown in stages of life that are similar to the development stages that Two-spirit participants shared in their coming out process. The advisory circle also acknowledged that the cycle is their L'nuwey or Mi'kmaw perspective of how coming out occurs for Two-spirit people. They strongly recognise that it is a visual representation, not a model, to describe the steps for coming out. A model may be developed with further engagement with the Two-spirit community in the region for validation, which is part of the ongoing process as it is shared in this paper.

My role was to use the perspectives and the advisory's guidance to develop a model that interprets the wholeness of being Two-spirited. Elder Marshall interpreted the cycle of life and the developmental stages in acquiring the gifts of life as stages when a person acquires love, honesty, humility, respect, truth, patience and wisdom.

The participants’ narratives about coming out shared that their process was non-linear, or cycle-like, yet gradual, and at times an ebbing between stages over some time. This description coincides with Dr. Alex Wilson's circle model of how identity develops as Two-spirits (Wilson, Citation1996), which provided a sense of assurance that the interpretation of the process was correct. However, the final validation occurred when we presented the model to the community and Elders before knowledge dissemination.

The circular dimensions of Elder Murdena's image include the representation of the four quadrants of mental, emotional, physical, and spiritual domains for acquiring the sacred gifts of life. The other significant representation is the developmental stages that people experience every seven years of life cycles. Elder Murdena had a keen sense of cultural perspectives as a spiritual healer and Elder. Her research, knowledge development and publications served to advance the Mi'kmaw culture for education, language preservation, and to understand how to humanise healthcare encounters for Indigenous People (Sylliboy & Hovey, Citation2020).

Elder Marshall's diagram offers the cultural understanding of cultural identity development that can be reinterpreted into other ways of studying Two-spirit identity. For example, the following can be explored further to dissect the developmental stages. Hypothetically, the first seven years of the coming out process of Two-spirit people may involve a Two-spirit child within their cultural surroundings, language, social interactions with other children, family, and school in the first seven years. The second stage could represent how Two-spirited youth explore their body, hormonal awakening, and the interconnected nature of their gender and sexuality. In the third phase, they are young adults in the maturing stage of their physical development. It is most likely that their sexuality is more mature but not necessarily fully developed or balanced within the four quadrants of their Two-spirit identity. The latter adult stages would be about maturity, evolving into the adult stages, which may include Two-spirited people evolving into their mature trans identity. The final stage of development may represent the final evolution to become Two-spirit Elders in the community. There is a significant opportunity to explore the development process as stages in future research.

The cycle of life as a coming out process

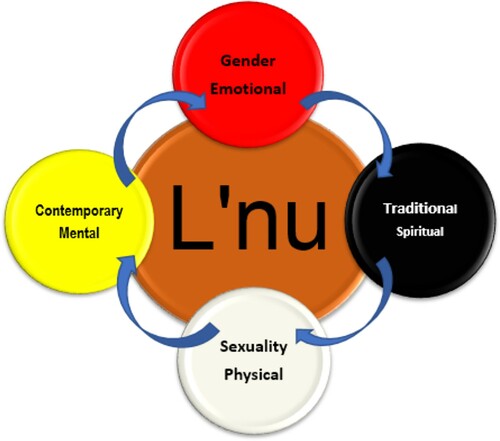

The L'nuwey worldview offered a conceptualisation of the coming out process that is part of a continuum or a part of one's evolving development as a Two-spirit person. The following process was to develop a visual representation of a contemporary expression of how a person or L'nu evolves into their gender, sexuality, and spirituality as a Two-spirit person. represents the outcome of a person who has evolved into their identity as a Two-spirit person.

The figure is a personal interpretation visualising the core identity of L'nu with its evolving identity that includes sexuality, or gender, with spirituality, within the context of space and time. It is meant to incorporate the life cycle of one's identity evolving within concepts of gender (non-binary, non-conforming, fluid, multi-gendered, non-gender, trans, etc.), and sexuality (gay, bisexual, pansexual, queer, etc.), separately or together. The process may include other components like tradition (beliefs, culture, history, and worldview) that intersects with contemporary ways of expression and being (Indigiqueer, evolving terms with the acronym – 2SLGBTQQIA+, or the right to not to identify as anything). All the identity components are not static; if anything, they are continuously negotiating within the four quadrants representing the emotional, mental, physical, and spiritual aspects that make us whole and balanced.

I interpreted all the knowledge and integrated it to explain how the most minute levels of coming out may occur from the micro to the macro levels as a Two-spirit person. Essentially, spirits (internal and external) that make up our body composition negotiate with each other to reach a state of balance. They negotiate internally in the body, for example, hormonal stages, simultaneously with the outer body's growth. The spirits are also influenced by the external spirits that define how we look, behave, and perceive ourselves. The social aspects of our coming out process are also influenced within the four realms.

I apply Elder Murdena's model () to incorporate that cycle of life and the concept of flux into the coming out process. The coming out process is a continuum of development that continuously evolves through the various stages of life (like acquiring the 7 gifts in the 7 stages of life) to reach the utmost balance as a L'nu. The Two-spirit development goes through negotiation of one's inner spirits (body makeup, hormonal development, etc.) with the outer spirits (gender, sexuality, sociability, culture) to become balanced or mature into a whole person as a Two-spirit being.

According to this worldview, a trans person goes through states of flux, the ebbing of spirits, to find the best representation of their being as a Two-spirit person. The spirits (inner and outer components that make up the identity as a human) of a trans person are continuously ‘transitioning’ or growing into their spiritual, emotional, mental, and physical being. However, their most central identity will always be as L'nu, or a Mi'kmaq (or the equivalent of their Indigenous self, or being human). Suppose the trans person's journey elements are adequately nurtured, protected, and supported as they transition into their balanced state; they will achieve balance as a Two-spirit person. In that case, they are more faithful to themselves and how they live socially. The belief is that trans people will go through that coming out process in various stages in their lives. Elders say that trans people and people who support them must embrace that process as part of the life cycle. The figure () and explanation of the coming out process were validated by Wabanaki trans youth at a Pride Gathering in 2017 at Mount Saint Vincent University.

Interestingly, L. Silko shares that ‘sexual identity is changing constantly’ (Silko, Citation1996, p. 13), which our study's participants felt about their sexuality or even their gender identity. I feet that Alex Wilson's explanation of identity and spirituality in a circular way (Wilson, Citation1996) and Silko's concept of sexuality that is constantly changing, are congruent concepts related to Two-spirit participants’ narratives about coming out as a non-linear process. Then, incorporating our L'nuwey worldview and integrating the Kloqowej concept of interconnectedness and Elder Murdena's teachings of the Seven Sacred Teachings further evidenced the coming out process as part of a life cycle for the Mi'kmaq as well as the Wabanaki People of Atlantic Canada. The community validation of the conceptualisation of Two-spirit and the coming out process as a cycle of life occurred when I defended my thesis in 2017.

There are models that exist which may contrast to our L'nuwey worldview about gender identity and sexuality. While this paper is not to contrast or compare the models, it is worth mentioning that the Kinsey scale (Kinsey Institute, Citation2019), also called the Heterosexual-Homosexual Rating Scale, is a linear based model that uses a scale system to determine your rate or level of ‘homosexuality’. Another settler model is outlined in a report by the Canadian AIDS Society (Ryan & Canadian AIDS Society, Citation2003) by Vivienne C. Cass as a theoretical model that outlines the six-phase process for identity formation. Neither model integrates Indigenous perspectives, however, it would be important to further analyze these models and understand any comparable ideas – for another study.

Decolonising systemic barriers for two-spirits

Community and urban barriers

The Indigenous population remains the fastest-growing demographic in Canada at 4.3 per cent, yet it remains a vulnerable population because of social determinants of health and the historical and ongoing colonisation effects (Assembly of First Nations National Youth Council, Citation2016). By not addressing health inequities for Indigenous people, there is a chance they will ‘likely result in a great burden of ill health’ (Latimer et al., Citation2014, p. 25) which continues to put Indigenous people at a disadvantage. There is a growing population of Indigenous people in urban centres in Canada who seek better employment opportunities, education and amenities provided in larger urban centres (Ristock et al., Citation2011). The Urban Indigenous Peoples Study (UAPS) reported evidence that ‘Two-spirits youth in their sample moved to the city to avoid homophobia and seek a better life’ (Ristock et al., Citation2011, p. 6).

Generally speaking, Two-spirit youth do not feel safe in their communities because of religion, misappropriation of cultural beliefs, and homophobia (Lerat, Citation2004) in Canada. Two-spirit youths still feel pressure to leave their families and communities to explore their identity in safer environments like cities (Lerat, Citation2004). Youth face forced mobility due to family and community pressure and to conform to heteronormative expectations. There is a sense of urgency to involve Two-spirit youth to develop initiatives for Two-spirit people by Two-spirit people in all areas of their development and safety.

The coming out study brings to the surface what Maynes identifies as a ‘historical and social dynamic that has been deliberately silenced’ (Citation2008, p. 9). The coming out stories may be the first step of social action to improve the outcomes for Two-spirited youth. The study is part of an ongoing effort by fellow Two-spirit scholars, researchers, writers, and advocates to deconstruct the ongoing inequities because of homophobia, transphobia and misogyny faced by Two-spirit youth.

Many Indigenous groups have language and culture that contextualises Two-spirits’ identity (Sylliboy, Citation2017a). Part of mental health and suicide prevention for indigenous youth is health promotion and empowerment through cultural pride through language and ceremony. A self-ascription process (Medicine, Citation2002) will need to reconceptualize the Two-spirits identity whereby language and collective identity instill cultural pride in reawakening the Two-spirits’ spiritual and ceremonial practices as a means of cultural continuity.

Suppose young people are provided love and nurturing in the families and communities. In that case, they are more likely to have stronger cultural values and cultural identity as means of suicide prevention and encourage the integration of a healthy identity (Garrett & Barret, Citation2003). According to the study, Two-spirit participants reconnected with their spirituality and cultural identity after coming out. The key is to explore ways to implement culture and health promotion strategies for Two-spirits awareness and education and build cultural identity through language to promote wellbeing for Two-spirited people, especially our youth (Hallett et al., Citation2007).

Advocacy and policy development

According to the findings from the online survey, part of the broader coming out research project (Sylliboy, Citation2017a), First Nations are becoming more welcoming places for Two-spirited youth, at least in the Atlantic region. The report published with these findings shows that seventy percent (70%) of youth remained in close contact with their families and home communities after coming out. Seventy percent (70%) of participants came out between thirteen and nineteen. Only about ten percent (10%) of Two-spirits who came out later in life shared stories of forced relocation to urban centres. There is a definite shift in tolerance and acceptance of the Two-spirit community.

Further study results show that Two-spirits are supported by their immediate loved ones, with friends (60%) and parents (45%) supporting them in the coming out process. It is worrisome that only twenty-five percent (25%) of the participants sought support with a clinician when they faced mental distress when coming out. Friends and family should not have to replace adequately trained clinicians to provide supportive services, especially for trans youth who may face mental distress during the coming out process. However, it speaks about the strong cultural ties that Two-spirit youth have in their community setting.

Supports include parents and peers

The coming out process is considered one of the most important milestones in one's life. There is a strong justification in establishing Gay-Straight Alliances (GSAs) and similar peer programmes for Indigenous youth. Peer mentor programmes would give youth space and a voice to share with others who share similar lives and experiences. Indigenous youth need safe spaces to explore their reality among people of their age groups. There could be workshops on strategies for youth empowerment, cultural identity, Two-spirits awareness, such as ‘cultural continuity, cultural connectedness, and cultural revitalisation’ (Yuen et al., Citation2019, p. 2). These would be proactive and cost-efficient health promotions for schools or communities.

MORE stories

Canada is a data-driven giant that continuously produces evidence-based research for policy and decision-making. Currently, Two-spirit people are not a demographic priority for research and policy development in Canada. Two-spirit people fall under the umbrella of 2SLGBTQQIA+ policies, which can cause the erasure of their specific needs. Although 2SLGBTQQIA+ organisations include the 2S in the acronym, much work is needed to properly represent the interests of our Two-spirit community in every sector.

Research about Two-spirit people is slowly increasing, but not compared to the amount of research about gay males, for instance. While there are campaigns for trans awareness and to combat transphobia in Canada, there is not enough data or content about Two-spirit people who identify as trans. Two-spirit allies, mainly Indigenous women and girls, lobbied for Two-spirits-trans women to be included in the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. The opportunity to build partnerships with allies in both the Indigenous community and outside the Indigenous context is critical for the Two-spirit community.

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) released the Calls to Action (Truth & Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Citation2015), but Two-spirit people are not identified in the 94 Calls to Action. It is a significant oversight on behalf of the TRC. In 2014, Justice Murray Sinclair invited Two-spirit leaders of Two-spirits organisations across Canada to share their stories of the injustices that the Two-spirit community endured in the Indian Residential Schools. The Commission expressed their sorrow and support for Two-spirit people, and they promised to include the witness stories in a report. Those stories need to be included to begin the healing process for Two-spirit people who attended the residential schools.

Sharing stories is a meaningful way to build knowledge about Two-spirit people and their lived experiences to better health. However, the Two-spirit community across Canada and Turtle Island wants more efforts to expand research and services for Two-spirited people in all areas, not just by-products of the 2SLGBTQQIA+ groups. Research should include Indigenous perspectives and methods about Two-spirit people furthering the elimination of patriarchy, misogyny, racism, homophobia, and transphobia.

Two-spirited people are among the most resilient Indigenous groups because they continue to survive and thrive despite historical and social traumas experienced by forced assimilation of patriarchal and heteronormative policies. Moreover, Two-spirited people prevail in all Indigenous communities. They are not vaccinated from societal injustices, yet they have developed natural ‘antibodies’ to survive the onslaught of settler colonialism and institutionalised patriarchy. This paper is about Two-spirit people celebrating life.

Disclosure statement

There are no competing interests to declare, and there are no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

Data availability statement

That data set associated with the paper, including the report's results, was submitted to the Urban Aboriginal Knowledge Network in 2017. The link to the report is: https://uakn.org/research-project/coming-out-stories-two-spirit-narratives-in-atlantic-canada/

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Two-spirit spelling may vary according to use: Two-spirit (noun), Two-spirited (adjective). The paper uses Two-spirit and 2S intermittently. Two-spirit(s) may be used to include people who may use other terms in English or in quotations.

2 The term Nations is used to represent Indigenous groups, which may include First Nations and the Labrador Inuit in this paper.

3 L’nu means the person or human who speaks the same language (Mi’kmaq). L’nu is the root word for the L’nuwey. By adding the suffix wey, the noun L’nu+wey changes the word into a proper adjective to describe worldview.

4 Acronym representing Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Queer, Questioning, Intersex, Asexual and the ‘+’ represents any other identifiers that represent non-conforming, non-binary expressions of sexuality or gender identity, and emerging terms. The acronym is used to identify mainstream people with Two-spirits (2S) interchangeably in this paper.

References

- ACHH Initiative. (2017). ACHH Video: Two-Eyed Seeing Approach. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F-Duzbupcfs.

- Assembly of First Nations National Youth Council. (2016). AFN NYC Calls to Action. http://health.afn.ca/en/news/general/afn-nyc-calls-to-action.

- Bartlett, C., Marshall, M., & Marshall, A. (2012). Two-Eyed Seeing and other lessons learned within co-learning journey bringing together Indigenous and mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 2(4), 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-012-0086-8

- Battiste, M. (2009). Maintaining Indigenous identity, language, and culture in modern society. In M. Battiste (Ed.), Reclaiming Indigenous voice and vision (pp. 191–208). UBC Press.

- Battiste, M. S. (1998). Protecting Indigenous knowledge and heritage: A global challenge. Purich Publishing Ltd.

- Bear, L. L. (2009). Jagged worldviews colliding. In M. Battiste (Ed.), Reclaiming Indigenous voice and vision (pp. 76–85). UBC Press.

- Bombay, A., Matheson, K., & Anisman, H. (2014). The intergenerational effects of Indian Residential Schools: Implications for the concept of historical trauma. Transcultural Psychiatry, 50(3), 320–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461513503380

- Brown, L. B. (1997). Two-spirits people: American Indian lesbian women and gay men. Harrington Park Press.

- Brown, M. A. (2011). Coming out narratives: Realities of intersectionality. [Doctoral dissertation, Georgia State University]. Sociology Dissertations. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1062&context=sociology_diss.

- Canon, M. J. (1998). The regulation of First Nation sexuality. The Canadian Journal of Canadian Studies, 18(1), 1–18.

- Castleden, H., Morgan, V., & Lamb, C. (2012). I spent the first year drinking tea: Exploring Canadian university researchers’ perspectives on community-based participatory research involving Indigenous peoples. The Canadian Geographer, 56(2), 160–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0064.2012.00432.x

- Chandler, M. J., & Lalonde, C. (1998). Cultural continuity as a hedge against suicide in Canada's First Nation. Transcultural Psychiatry, 35(2), 191–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/136346159803500202

- Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research (1 ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Cromwell, J. (1997). Traditions of gender diversity and sexualities: A female-to-male transgendered perspective. In S.-E. W. Jacobs (Ed.), Two-spirited people: Native American gender identity, sexuality, and spirituality (pp. 119–142). University of Illinois Press.

- Doucette, J., Bernard, B., Simon, M., & Knockwood, C. (2004). The medicine wheel: Health teachings and health research. [PowerPoint presentation]. http://www.integrativescience.ca/uploads/articles/2004June-Doucette-Bernard-Simon-Knockwood-Medicine-Wheel-Indigenous-health-Integrative-Science.pdf.

- Dworkin, M. S. (1959). Dewey on education selections. Teachers College Press.

- Evans-Campbell, T. K. (2012). Indian boarding school wxperience, substance use, and mental health among urban Two-spirit American Indian/Alaska natives. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 38(5), 421–427. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2012.701358

- Ferlatte, O., Salway, T., Rice, S. M., Oliffe, J. L., Knight, R., & Ogrodniczuk, J. S. (2020). Inequities in depression within a population of sexual and gender minorities. Journal of Mental Health, 29(5), 573–580. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2019.1581345

- Fiedeldey-Van Dijk, C., Rowan, M., Dell, C., Mushquash, C., Hopkins, C., Fornssler, B., Hall, L., Mykota, D., Farag, M., & Shea, B. (2017). Honouring Indigenous culture-as-intervention: Development and validity of the native wellness assessment. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 16(2), 181–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332640.2015.1119774

- First Nations Information Governance Centre. (2020). The First Nations principles of OCAP®. https://fnigc.ca/ocap.

- Garrett, M. T., & Barret, B. (2003). Two-spirit: Counseling Native American gay, lesbian and bisexual people. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 31(2), 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1912.2003.tb00538.x

- Gilley, B. J. (2006). Becoming Two-spirit: Gay identity and social acceptance in Indian country. University of Nebraska Press.

- Goha, A., Mezue, K., Edwards, P., Madu, K., Baugh, D., Tulloch-Reid, E. E., … Madu, E. (2021). Indigenous people and the COVID-19 pandemic: The tip of an iceberg of social and economic inequities. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 75(2), 207–208.

- Government of Canada. (2017). Apology to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and two-spirit federal public servants. https://www.canada.ca/en/privy-council/news/2017/11/apology_to_lesbiangaybisexualtransgenderqueerandtwo-spiritfedera.html.

- Government of Canada. (2018). TCPS 2 – Chapter 9: Research involving the First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples of Canada. https://ethics.gc.ca/eng/tcps2-eptc2_2018_chapter9-chapitre9.html.

- Hall, L., Dell, C. A., Fornssler, B., Hopkins, C., Mushquash, C., & Rowan, M. (2017). Research as cultural renewal: Applying Two-Eyed Seeing in a research project about cultural interventions in First Nations addictions treatment. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 6(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2015.6.2.4.

- Hallett, D., Chandler, M. J., & Lalonde, C. E. (2007). Aboriginal language knowledge and youth suicide. Cognitive Development, 22(3), 392–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogdev.2007.02.001

- Health Canada. (2016). Suicide prevention. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/first-nations-inuit-health/healthpromotion/suicide-prevention.html.

- Hill, D. M. (2003). HIV/AIDS among First Nations people: A look at disproportionate risk factors as compared to the rest of Canada. The Canadian Journal of Native Studies, 23(2), 239–359.

- Hodge, F., Schanche, A. P., Marquez, C. A., & Geishirt-Cantrell, B. (2002). Utilizing traditional storytelling to promote wellness in American Indian communities. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 13(1), 6–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/104365960201300102

- Hottes, T. S., Ferlatte, O., & Gesink, D. (2015). Suicide and HIV as leading causes of death among gay and bisexual men: A comparison of estimated mortality and published research. Critical Public Health, 25(5), 513–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2014.946887

- Hovey, R. B., Delormier, T., McComber, A. M., Lévesque, L., & Martin, D. (2017). Enhancing Indigenous health promotion research through Two-Eyed Seeing: A hermeneutic relational process. Qualitative Health Research, 27(9), 1278–1287. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317697948

- Hunt, S. (2016). An introduction to the health of Two-spirit People: Historical, contemporary and emergent issues. https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/emerging/RPT-HealthTwoSpirit-Hunt-EN.pdf.

- IODE (Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire). (2016). The IODE RCMP Community Service Award 2016. http://www.iode.ca/iode-rcmp-community-service-award-2016.html.

- Iwama, M., Marshall, M., Marshall, A., & Bartlett, C. (2009). Two-Eyed Seeing and the language of healing in community-based research. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 32(2), 3–23. http://search.proquest.com/openview/3a5489d04bdc935a971d94d6654ef640/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=30037.

- John-Henderson, N. A., & Ginty, A. T. (2020). Historical trauma and social support as predictors of psychological stress responses in American Indian adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 139, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110263.

- Kinsey Institute. (2019). The Kinsey Scale. Indiana University. https://kinseyinstitute.org/research/publications/kinsey-scale.php.

- Kirmayer, L., Brass, G., Holton, T., Paul, K., Simpson, C., & Tait, C. (2007). Suicide among Indigenous people in Canada. Indigenous Healing Foundation, http://www.ahf.ca/downloads/suicide.pdf.

- Kovach, M. (2009). Indigenous methodologies: Characteristics, conversations, and contexts. University of Toronto Press.

- Laslet, B. M. (2008). Telling stories: The use of personal narratives in the social sciences and history. Cornell University Press.

- Latimer, M., Simandl, D., Finley, A., Rudderham, S., Harman, K., Young, S., MacLeod, E., Hutt-MacLeod, D., & Francis, J. (2014). Understanding the impact of the pain experience on Aboriginal children’s wellbeing: Viewing through a Two-Eyed Seeing lens. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 9(1), 22–36.

- Latimer, M., Sylliboy, J. R., MacLeod, E., Rudderham, S., Francis, J., Hutt-Macleod, D., & Finley, G. A. (2018). Creating a safe space for First Nations youth to share their pain. PAIN Reports, 3(Suppl 1), e682. https://doi.org/10.1097/pr9.0000000000000682.

- Lerat, G. (2004). Two spirit Youth Speak Out! analysis of the needs assessment tool. Urban Native Youth Association.

- Lezard, P., Prefontaine, Z., Cedarwall, D. M., Sparrow, C., Maracle, S., Beck, A., & McLeod, A. (2021). MMIW2SLGBTQQIA+ National Action Plan: Final Report. https://mmiwg2splus-nationalactionplan.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/2SLGBTQQIA-Report-Final.pdf.

- Linklater, R. (2014). Decolonising trauma work: Indigenous practitioners share stories and strategies. Fernwood Books Ltd.

- Marshall, M. (2005). On tribal consciousness: The trees that hold hands. Institute for Integrative Science & Health. http://www.integrativescience.ca/uploads/articles/2005November-Marshall-WIPCE-text-On-Tribal-Consciousness-Integrative-Science.pdf.

- Martin, D. H. (2012). Two-Eyed Seeing: a framework for understanding Indigenous and non-Indigenous approaches to Indigenous health research. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research Archive, 44(2), 20–42.

- Maynes, M. J. (2008). Telling stories: The sse of personal narratives in the social sciences and history. Cornell University Press.

- Medicine, B. (2002). Directions in gender research in American Indian societies: Two spirits and other categories. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 3(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1024

- Meyer-Cook, F., & Labelle, D. (2004). Namaji: Two-spirit organizing in Montreal, Canada. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 16(1), 29–51. https://doi.org/10.1300/J041v16n01_02

- Ranahan, P., Yuen, F., & Linds, W. (2017). Suicide prevention education: Indigenous youths’ perspectives on wellness. Journal of Indigenous Wellbeing: Te Mauri – Pimatisiwin, 2(1), 15–28.

- Reading, C. L., & Wien, F. (2009). Health inequalities and social determinants of Aboriginal peoples’ health. National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health.

- Ristock, J. Z., Zoccole, A., & Potskin, J. (2011). Aboriginal Two spirit and LGBTQ migration, mobility, and health research project: Final report. Vancouver.

- Robinson, M. (2014). “A hope to lift both my spirits”: preventing bisexual erasure in Indigenous schools. Journal of Bisexuality, 14(1), 18–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2014.872457

- Robinson, M. (2019). Two-spirit identity in a time of gender fluidity. Journal of Bisexuality, 67(12), 1675–1690. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2019.1613853

- Roscoe, W. (1998). Changing ones: Third and fourth Ggenders in Native North America. St. Martin's Press.

- Ryan, B., & Canadian AIDS Society. (2003). A new look at homophobia and heterosxism in Canada. Canadian AIDS Society.

- Silko, L. M. (1996). Yellow woman and a beauty of Two-spirit: Essays on Native American life today. Simon & Schuster.

- Simonds, V. W., & Christopher, S. (2013). Adapting western research methods to Indigenous ways of knowing. American Journal of Public Health, 103(12), 2185–2192. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301157

- Smith, L. T. (2009). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples (2 ed.). Zed Books.

- Smylie, J., Olding, M., & Ziegler, C. (2014). Sharing what we know about living a good life: Indigenous approaches to knowledge translation. Journal of the Canadian Health Libraries Association, 35(1), 16–23. https://doi.org/10.5596/c14-009

- Sylliboy, J. R. (2017a). Coming out stories: Two-spirits narratives in Atlantic Canada. Urban Indigenous Knowledge Network. http://uakn.org/research-project/coming-out-stories-two-spirit-narratives-in-atlantic-canada/.

- Sylliboy, J. R. (2017b). Two-spirits: Conceptualization in a L'nuwey Worldview. [Master’s thesis, Mount Saint Vincent University]. MSVU Theses. http://dc.msvu.ca:8080/xmlui/handle/10587/1857.

- Sylliboy, J. R. (2019). Using L'nuwey Worldview to conceptualize Two-spirit. Antistasis, 9(1), 96–116.

- Sylliboy, J. R., & Hovey, R. B. (2020). Humanizing Indigenous peoples’ engagement in health care. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 192(3), E70–E72. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.190754.

- Sylliboy, J. R., Latimer, M., Marshall, E. A., & MacLeod, E. (2021). Communities take the lead: Exploring Indigenous health research practices through Two-Eyed Seeing & kinship. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 80(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/22423982.2021.1929755.

- TASSC. (2013). Forgotten voices. Toronto Aboriginal Support Services Council. https://www.tassc.ca/uploads/1/2/1/5/121537952/_forgotten_voices-booklet-final.pdf.

- Toomey, R. B. (2010). Gender – Non-conforming lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: School victimization and young adult psychosocial adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 1(11), 1580–1589. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020705

- Truth & Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Canada's residential schools: Reconciliation: The final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Volume 6. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2015/trc/IR4-9-6-2015-eng.pdf.

- Wabanaki Two-spirit Alliance (W2SA). (2011). Mawita’jik Puoinaq: A Gathering of Two Spirited People. Unpublished Report.

- Williams, W. L. (1986). The spirit and the flesh: Sexual diversity in American Indian culture. Beacon Press.

- Wilson, A. (1996). How we find ourselves: Identity development and Two-spirit people. Harvard Educational Review, 66(2), 303–317. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.66.2.n551658577h927h4

- Wilson, S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Fernwood Pub.

- Wilton, T. (2000). Out/performing our selves: Sex, gender and cartesian dualism. Sexualities, 3(2), 237–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/136346000003002008

- Young, T. (2016). L'nuwita'simk: A foundational worldview for L'nuwey justice system. Indigenous Law Journal, 13(1), 75–102.

- Yuen, F., Ranahan, P., Linds, W., & Goulet, L. (2019). Leisure, cultural continuity, and life promotion. Annals of Leisure Research, 24(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2019.1653778