ABSTRACT

The Creative Change Laboratory (CCoLAB) was conceived as an immersive learning space in which young people from the Western Cape province of South Africa could develop unconventional solutions to problems in their communities. Unlike most art-activism projects, CCoLAB harnessed a wide range of expressive forms (visual art, interactive drama, narrative writing and photography/videography) to identify, analyse and respond to social justice challenges. In many ways, CCoLAB was an experiment, asking what could be achieved if an art-activism project was held over a long period and was not constrained by a focus on just one theme/topic. Over eight months, CCoLAB’s twenty collaborators were exposed to different ways of thinking and doing activism, culminating in the development of original creative prototypes. Many of the final artworks spoke to the nuances of sexuality, gender and health, exploring topics such as sexual- and gender-based violence, the everyday challenges facing queer and trans youth, and physical, mental and emotional wellbeing. Drawing on artworks produced during the project, facilitator/collaborator reflections, and audio and visual recordings made during the process, this paper investigates the benefits and challenges of long-term, well-resourced art-activism interventions.

The Creative Change Laboratory (CCoLAB) was conceived as an immersive learning space for young people interested in arts-based activism (). The project brought together a diverse group of collaborators from the greater Cape Town region, with an emphasis on youth at the margins of society, including young women of colour, young migrants and refugees, and young lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) people. Its objective was to support collaborators in developing unconventional solutions to problems in their communities. Those who took part were introduced to a wide range of expressive modes – drama, photography, videography, visual art, narrative writing and zine-making – which were then used to identify, analyse and respond to social justice issues.

Unlike most arts-based interventions, CCoLAB did not focus on a single community or address one specific topic. However, as the project developed, several dominant themes emerged. Perhaps the most obvious of these was the intersection of sexuality, gender and health. At face value, collaborators’ creative prototypes and written/spoken reflections show that sexual and gender health inequalities are important to the young people who took part in CCoLAB. Yet, when interrogated more closely, this data points to potential shortcomings in long-term, well-resourced interventions like CCoLAB. Using sexuality, gender and health as its entry point, this paper argues that arts-based methods can both encourage and stifle critical thinking. It shows how in facilitated spaces, where disparate identities, histories, experiences, objectives and political orientations jostle for legitimisation, tensions around the production, representation and dissemination of knowledge can emerge.

Pedagogical and epistemological orientation

Connection is really important because we want to hear other people’s stories, and we want our stories to be heard … We all have in common the fact that we struggle … It’s important to connect over these issues, and to listen to each other so that we can make the world a better place. – Jules (young cisgender queer female)

The methodology that was subsequently developed drew heavily on popular education pedagogies, specifically the theories of Paulo Freire (Citation1970) and the practices of Augusto Boal (Citation1979). CCoLAB’s approach prioritised collective and experiential modes of learning. This allowed collaborators to draw connections between their personal realities as racialised, gendered and sexed bodies in an unequal society and to use these reflections as the foundation for political analysis. The goal was conscientização (Freire, Citation1970) – critical awareness of how oppression manifests and can be resisted. Conscientização occurs through iterative processes of learning, creating and reflecting. As a practice, conscientização attempts to create a space in which people can draw on their collective lived experiences to formulate an analysis of inequality and then use that knowledge to push against unjust and exploitative systems (Francis & Khan, Citation2020). Importantly, Freire speaks about conscientização in relation to both the oppressed and the oppressor, as in the teacher–student dichotomy on which formal education systems are based. Thus, conscientização requires an awareness of power dynamics within learning spaces and a commitment to challenging hierarchical organisational models.

Throughout this paper we intentionally use the term collaborator rather than participant, as we did during the project itself. We do this to foreground the active role that collaborators played in the process. Freire argues that true liberation can only occur when those leading interventions actively collaborate with those experiencing oppression, rather than viewing themselves as the sole proprietors of history, expertise, authority and empowerment. Our goal with CCoLAB was to work with marginalised groups to (re)interpret, (re)imagine and respond to their social realities. The collaborators played a critical role in curating the laboratory space. At points, they pushed back against certain pedagogical and creative activities, leading to important shifts in the process.

In addition to drawing inspiration from conscientização, the CCoLAB methodology was grounded in the practices of arts-based research (ABR), in that it sought to generate collaborative knowledge through expressive techniques. ABR is particularly useful for unlocking and exploring the sensuous, affective, tacit and embodied aspects of human experience. For Barone and Eisner (Citation2012), ABR represents ‘an effort to extend beyond the limiting constraints of discursive communication in order to express meanings that otherwise would be ineffable’ (p. 2). As a method for participatory knowledge creation, ABR has the potential to serve ‘as a vehicle for liberation, radical social transformation and the promotion of solidarity’ (Chatterton et al., Citation2007, p. 218). Activists and scholars from South Africa echo this position, arguing that ABR methods build intellectual and political links between marginalised communities, socially responsive researchers and broader struggles for social justice (Khan, Citation2014; Marnell et al., Citation2021; Moletsane et al., Citation2009). Finally, and perhaps most importantly, ABR techniques have the potential to create ‘transformative moments for all involved – researchers, participants and public audiences alike’ (Oliveira, Citation2016, p. 276) by evoking strong cognitive and emotional responses.

Despite this enormous potential, arts-based methodologies cannot be regarded as innately liberatory. Savneet Talwar (Citation2015) argues that creative methodologies can inadvertently reinforce inequalities. Similar concerns have been flagged by Elizabeth Ellsworth (Citation1989), who argues that the lexicon of participatory methods (‘empowerment,’ ‘dialogue,’ etc.) is actually a repressive myth that sustains oppressive power dynamics, and by Sara Ahmed (Citation2006), who notes that ‘progressive’ interventions sometimes produce the opposite of what they set out to achieve (e.g. anti-racist actions that reproduce structural racism). These limitations are key to theorising the challenges faced by CCoLAB.

Finally, CCoLAB was an experiment in decolonising the production, dissemination and application of knowledge. Its methodology drew directly on the work of decolonial scholars and activists (e.g. Jackson & Shanks, Citation2017; Seidl-Fox & Sridhar, Citation2014). Our praxis attempted to trouble the supremacy of Euro-American pedagogical and epistemological frameworks, especially the inferiorisation of African worldviews and expressive modes (Abdi, Citation2012). By drawing on popular education theories, arts-based methods and decolonial approaches, we strived to create a democratic learning space in which collaborators and facilitators discovered, tested and refined creative responses to oppression.

The workshop process

CCoLAB [is] literally a space where you can explore with different artistic methods ways in which you can tackle the problems you are facing in society. – Lance (non-binary and mixed race)

Selection was based on an online application process. The call for collaborators was circulated through the facilitators’ networks and advertised as sponsored posts on Facebook and Instagram. The project was aimed at young people aged between fifteen and twenty-five, though other ages were considered. Interested candidates were asked to complete a form that captured their self-identifications, interests and artistic experiences. Applicants were also asked to provide a simple analysis of a challenge in their community. Efforts were made to recruit a diverse group of collaborators, not only in terms of demographics (e.g. racial and gender diversity) but also in terms of political orientations and creative interests. Twenty collaborators were selected for the project, although this number fluctuated as people came in and out of the process.

Collaborators signed a participation agreement, which included a consent declaration, at the start of the project. As well as outlining the scope and purpose of CCoLAB, the agreement stipulated that participation/consent could be withdrawn at any point. Collaborators were free to specify how they would be described in project outputs. Thus, collaborators are identified here using their own descriptors rather than in a uniform style. For example, Winnie offered the following description of herself: ‘I am a black Zimbabwean girl … crowned with my kinky hair and large arms and long legs … I am a girl … black … Zimbabwean … girl’.

Collaborators used terms such as ‘womxn,’ ‘gender-liminal,’ ‘female,’ ‘woman,’ ‘queer,’ ‘non-binary,’ ‘straight’ and ‘man’ to make sense of their gendered locations. There were often accompanied by markers of race, ethnicity and culture, including ‘Xhosa,’ ‘Tswana,’ ‘Zulu,’ ‘black,’ ‘coloured,’Footnote1 ‘white’ and ‘mixed race but I identify as black’.

While it is possible to provide a demographic breakdown based on these descriptions, doing so fails to do justice to the complex ways in which collaborators understood their social locations. We offer the following summary as a guide only: nine collaborators identified as women, four as men and five as transgender or gender-nonconforming; twelve collaborators identified as black, four as coloured and two as white. Collaborators also used an array of terms to refer to sexuality, including a number who rejected stable identity markers.

As facilitators, we saw ourselves as active collaborators in the CCoLAB process. Thus, we believe it is equally important for our social locations to be interrogated. Gabriel identifies as a gender-nonconforming queer person but is primarily read as a man, while John identifies as a cisgender queer man. Gabriel is South African of South Asian origin and John is a white Australian based in South Africa.

CCoLAB was funded through the Facebook Community Leadership Programme, which supported initiatives that used Facebook, Instagram and/or WhatsApp to empower communities. This generous grant allowed us to purchase a wide variety of arts supplies, rent dedicated venues and recruit guest facilitators. It also allowed us to boost posts on the aforementioned platforms. By its conclusion, CCoLAB had reached approximately 200,000 people via Facebook and Instagram. This allowed us to amplify the voices of young people to a degree not normally seen in arts-based projects.

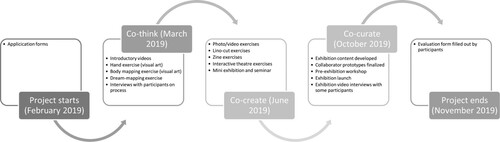

The project was delivered as three learning blocks:

Co-think: The first learning block enabled collaborators to identify and consider various forms of injustice and exclusion (e.g. individual, community and structural violence). It also introduced three critical frameworks – gender, race and decolonialism – for analysing oppression.

Co-create: The second learning block introduced collaborators to a broad range of arts techniques and enabled them to design, develop and test creative solutions to social challenges. It culminated in the development of individual prototypes that drew on one or more creative method.

Co-curate: The final learning block was an opportunity for collaborators to curate their prototypes and other artworks into an exhibition and public seminar. In addition to placing their works within an exhibition space, collaborators developed supporting content, such as framing questions and promotional materials ().

The length and intensity of CCoLAB meant that a great deal of data was generated. In a typical arts-based intervention, one or two arts methods are used and data is collected in a participatory manner at key points (usually after each activity and at the conclusion of the workshop). Because CCoLAB ran for so long, we had to collect data on a more ad hoc basis, although there were specific points when structured reflection processes took place. It quickly became apparent that gender, sexuality and health were key areas of interest (among other crosscutting themes). It is important to stress that these themes did not present in a linear manner, nor can they be considered discrete. Interest in gender, sexuality and health emerged in a multitude of ways as collaborators experimented with new art techniques and responded to different social issues. Thus, it is difficult to explicate the myriad ways in which collaborators engaged with these concepts.

Situating the project: Sexuality, gender and health in South Africa

CCoLAB took place in South Africa, a country that faces staggering rates of inequality and violence. In Citation2019, Stats SA – South Africa’s national statistics agency – reported stark wealth disparities along racial lines, with black and coloured South Africans facing persistent unemployment and social exclusion, a reality more acutely felt for women, young people and those living in rural areas. These socio-economic inequalities have a direct impact on health outcomes. Very few South Africans have private health insurance, forcing them to use strained and at times failing public services (Omotoso & Koch, Citation2018). Access is further compromised for those who are socially marginalised, such as migrants (de Gruchy et al., Citation2021), LGBT persons (Luvuno et al., Citation2019) and those living with disabilities (Van der Heijden et al., Citation2020).

One cannot talk about health in South Africa without acknowledging the prevalence of sexual- and gender-based violence. There is also significant evidence showing that South Africa’s progressive laws have done little to stem discrimination against those perceived to be LGBTI. Data suggests that homophobic/transphobic violence often intersects with other forms of oppression, leading to targeted persecution against black lesbian women and gender-nonconforming individuals (Matebeni, Citation2013), LGBTI refugees and migrants (Marnell et al., Citation2021) and LGBTI youth (Khan, Citation2014).

The collaborators in this project live within mutually constitutive systems of oppression that discriminate against or empower young people based on their geographical and social locations, as embodied through their race, class, nationality, ability, documentation status, gender identity and sexual orientation. In this regard, theories such as intersectionality (Crenshaw, Citation1989) and assemblage (Puar, Citation2013) can be useful in making sense of the inequalities that cut across South African society, especially as they pertain to gender and sexuality. However, caution is required when discussing the role of gender and sexuality within systems of oppression. It is important to recognise that these concepts are deeply rooted in imperialism (McAllister, Citation2013). Furthermore, geopolitical inequalities have created a research environment in which Euro-American ways of producing knowledge are seen as legitimate and rigorous, whereas alternative scholarly or activist responses are less valued (Nyanzi, Citation2011).

In recent years, African feminist theories have emerged as a counterpoint to Euro-American frameworks (Bennett, Citation2011; Matebeni, Citation2014). Local scholars argue that research on African genders and sexualities should acknowledge the complex histories, social contexts and regulatory processes that shape the production of meanings (Tamale, Citation2011). They call for scholarship that looks beyond simple readings of sex, gender and sexual orientation and that incorporates analyses of key social factors, such as knowledge, attitudes and behaviours, as well as practices of pleasure, dress, identity and power.

Both during CCoLAB and in this article, we take ‘health’ to mean ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ (World Health Organisation, Citation1948, p. 1). In the outputs discussed here, collaborators rarely speak directly about health services; instead, they reflect on what it means to belong, thrive and feel safe.Footnote2 Thus, it is best to see these works as a response to physical, mental and emotional wellbeing. Reading CCoLAB outputs through the lens, rather than applying a physical or mental health framework, acknowledges that the struggles faced by South African youth are as much about social factors (violence, poverty, exclusion, etc.) as they are about pathology.

Additionally, decolonial scholars have offered a critique of the hierarchical relationship between Western mental health classifications and indigenous and community healing practices (Mkhize, Citation2004; Motsi & Masango, Citation2012). Community healing practices focus on a person’s connection to their past, their community and their ancestors, allowing for a social understanding of their wellbeing (Volks et al., Citation2021).

Finally, it is important to recognise the impacts of apartheid on physical, mental and social wellbeing. Research shows that intergenerational trauma is transferred through personal relationships, family systems and socio-cultural processes (Hoffman, Citation2004). In the South African context, organisations have used arts-based methods to deal with gender-based violence and political violence (e.g. Seidman & Schaer, Citation2011).

The interplay of these dynamics is reflected in the collaborators’ artworks and analyses. In the quote below, Masechaba – who describes herself as a black womxn – identifies social and environmental factors linked to mental health:

My artwork … explores the issue of mental health, emotional and mental wellbeing, and the strain that people living in impoverished and very dense areas, very low-income areas, are struggling with. … [I]t’s also saying there is a lack of green spaces in township areas.

A note on the facilitators

Finding a balance between the facilitators’ vision and the participants’ [evolving] expectations is always an issue in creative workshops, but it’s amplified here because of the length and intensity of the project. And on top of that we have strict donor outputs to meet. – John

On one hand, we have our vision, which includes learning processes [and] outcomes, and on the other are [collaborator] expectations. I wonder how we keep a space democratic while not losing sight of those learning outcomes. How do we acknowledge challenges or voices in the moment, while not losing sight of learning goals? – Gabriel

The two of us met while working for Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action, a Johannesburg-based NGO. As part of our work, we facilitated short workshops across Southern Africa, with Gabriel leading on art for activism and John on citizen journalism. Through co-facilitating over many years, we were able to identify gaps and opportunities in our praxis, inspiring us to develop the CCoLAB methodology, which we hoped would enable a deeper kind of learning and potentially generate real change.

Facilitating CCoLAB was physically and emotionally draining, and it strained our relationship as friends, colleagues and activists. Gabriel, who was based in Cape Town during the project, played a more hands-on role, taking responsibility for logistics and administration on top of facilitation. This led him to be bogged down in managing a large laboratory space, including dealing with venues and catering, organising transport and procuring specialised art equipment. This put Gabriel in a more top-down position, one of manager rather than facilitator, and impacted their engagements with collaborators. On the flip side, John, who lives and works in Johannesburg, flew down to co-facilitate each CCoLAB learning block. This provided him with critical distance and positioned him as a neutral inciter (Boal, Citation1979). John played an important role, channelling feedback from the collaborators to Gabriel and working with collaborators to ensure the direction and pace of CCoLAB suited their expectations.

The roles we played gave rise to different experiences and relationships. This was reflected in the writing of this paper, with the two of us approaching the task from different directions. Gabriel, who has more knowledge about the operationalisation of CCoLAB, brought in perspectives from the intervention as a whole, including the parts where creating and disseminating art products were not a priority, whereas John could focus more on specific art products and the interpretation/feedback related to them. Additionally, factors like race and nationality shaped our interactions with collaborators and partners. At different points in the project, collaborators pushed us to confront our own complicity in systems of racism. For example, collaborators highlighted how they felt unwelcome at one of the venues we had selected. Our previous work on gender and sexuality also likely produced a selection bias (i.e. prioritising collaborators interested in these themes) and greater emphasis on queer analyses.

We share these thoughts as a form of political action. We want to acknowledge that facilitating and writing about intensive processes can be hard, even for those who have worked closely for many years. For us, three issues became visible: tensions related to personal relationships (e.g. collaborating with white people as people of colour in contexts of structural racism); tensions over facilitation styles/approaches when we come with different skills, responsibilities and interests, especially when facing critiques of our praxis; and tensions over how we analyse and write about our work so as to generate honest and productive reflections.

A note on creative materials

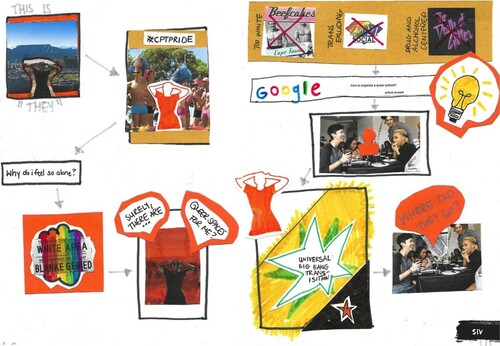

We use images and other creative products as more than decoration. Their inclusion here is intended to encourage researchers and readers to re-vision and re-present hard-to-quantify concepts like ‘sexuality’ and ‘wellbeing’ (Fischman, Citation2001). For example, Siv’s zine spread is a textured, multi-layered collage that lends itself to multiple interpretations. Unlike a spoken or written narrative, Siv’s work encourages audiences to interact with it, to follow its flow and to draw meaning from its interplay of words, images and symbols. It does not provide a complete or obvious answer, but rather invites audiences to ask/answer questions for themselves. Put another way, the spread tells us a lot about Siv’s personal struggles as a ‘Black gender-queer, gender-fuck, gender-liminal trans artist-activist-academic’ (self-description), but it also encourages us to contemplate loneliness, substance use and access to social spaces/services within our own lives.

Struggling for equality: Spotlight on sexuality, gender and health

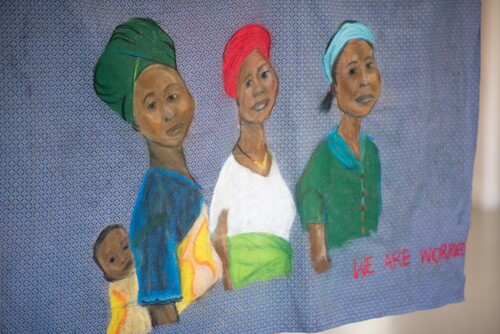

By the end of the project, it was evident that many collaborators had an interest in one or more dimensions of sexuality, gender and health. This can be seen in the prototypes displayed in the final exhibition. Winnie used quilting to explore discrimination and resilience among refugee women of African origin (). She saw her prototype as a statement on sexism, racism, xenophobia and skin-tone bias:

My artwork is about raising awareness of gender-based violence as well as refugees. I used, um, dark-pigmented women, instead of light-pigmented women, because even though there is discrimination against race in general, there is also colourism. So the darker you are … it’s just worse for you. So I’m just trying to remind people that women are human and they don’t deserve to be treated the way that society treats them.

No body should be excluded because of its size or its shape or whether it’s ‘unattractive’ or too flabby. It’s a body. We want to be touched; we want to be loved … You’re a great woman. You’re a great black woman. Feel it!

Each hand on a rope is of a different survivor. … The reason the hands are connected together in a circle is so that they can show solidarity with each other. Thinking of all my female friends, I don’t know one who hasn’t experienced some form of sexual assault. It’s been a part of our lives since we were incredibly small … It’s a plague in our community. … I feel that art really, really, really helps and is a great form of therapy – like, [an] untraditional form of therapy when it comes to healing.

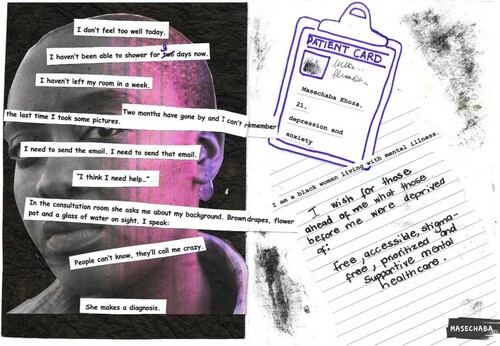

Masechaba: ‘I don’t feel too well today’ ()

On the left side of the spread, an image of Masechaba dissolves and bleeds colour. Floating above the image are short reflections on Masechaba’s own experience of mental health, including statements about not feeling well, not being able to shower, the trepidation associated with seeking help and the shame associated with struggling. In the text, a healthcare practitioner makes a judgement. The clipped nature of this interaction suggests that the ‘diagnosis’ did not adequately respond to Masechaba’s needs. Rather than foster a space for healing and action, the diagnosis ends the conversation. This spread not only offers an account of Masechaba’s experiences, but also creates an opening for the reader/viewer to reflect on their own situation. That Masechaba wanted to talk about shortcomings in the provision of mental health services using a gender perspective is evident from her spoken reflections. In the excerpt below, she uses the word ‘fight’ to describe her personal experiences as a young black womxn:

On a daily basis the body is in a constant battle with the world, with the mind. Because I am a womxn, because I am black, I am in a constant fight, and sometimes it feels like a losing battle, but nevertheless I continue to fight.

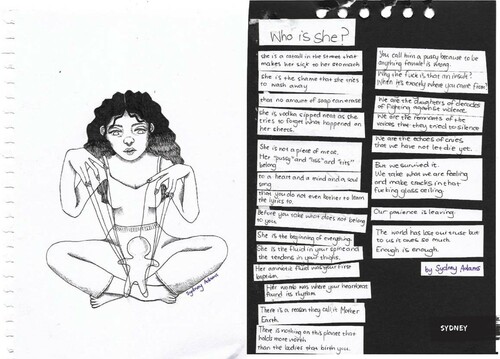

Sydney: ‘Who is she?’ ()

Sydney, a young woman, divided her spread into two sections: the left side has an image of a woman with a marionette, while the right features a poem. Sydney, like Masechaba, opted for a linear narrative using cut-out blocks. Her text includes a vivid, emotive and at points explicit description of the afterlife of sexual violence, specifically how it affects women survivors. The text echoes the puppet imagery, detailing how women’s bodies are objectified and sexualised and how society’s obsession with women’s bodies draws attention away from their hearts, minds and souls. The text also poses questions for the reader/viewer. For example: ‘You call him a pussy because to be anything female is wrong. Why the fuck is that an insult?’ Unlike the other collaborators featured here, Sydney’s narrative begins in the singular third person (she) and then transitions to the plural first person (we) for the last few lines. This pushes the reader/viewer to identify with women’s struggle against sexual violence and to consider their role in the systems that perpetuate it. Sydney offered the following analysis of her work:

My zine spread is about the seemingly inescapable objectification of women: how women are reduced to concepts, often based off their bodies, and not much thought is given to who women are, only what they are … I would be happy if my zine spread made the reader uncomfortable, maybe sad. I want them to sit with the understanding that the experiences my writing describes are everyday occurrences for women – they have been happening for centuries, and they are happening now.

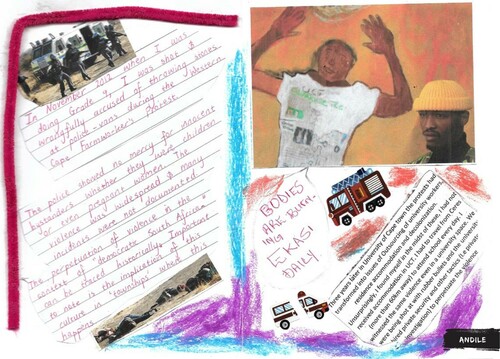

Andile: ‘Bodies are burning daily in ekasi’ ()

Andile created a collage using text, stickers, newspaper images, a photograph and tactile materials. The text recounts his experience participating in, and being a bystander to, protest action in ekasi (a Nguni term for a township). Through his bold words and images, Andile challenges the reader/viewer to rethink their opinions on ekasi life. Unlike the other examples, Andile offers a structured autobiographical story with a clear timeline. His story shares a unique and personal insight into events the reader/viewer might have learnt about through the news or other sources. In locating himself as a ‘marginalised young black man’ (self-description), Andile offers insight into the masculinist nature of violence in South Africa (Ratele, Citation2013). In doing so he offers an important perspective on how intersecting aspects of his identity (race, gender, socioeconomic position, etc.) shape his experiences of inequality and drive negative health and wellbeing outcomes. In an interview, Andile shared two phrases to reflect on his work:

Knowledge of self – this speaks to our history, my history personally as a black person. I feel like little has been said about my history, and I feel like I know little, except of the historical injustices. The status of the youth – I feel like the youth are marginalised in a sense that they are unrecognised, their struggles are unrecognised. [emphasis added]

Intersectional-ish

One of the things CCoLAB tried to do differently was bring together a diverse group of collaborators. This strengthened the intervention by allowing divergent perspectives into the workshop space. Yet it also created friction on more than one occasion. Perhaps the most salient of these tensions involved some collaborators’ disregard of race. In one incident, a collaborator whose topic was sexual- and gender-based violence shared the initial concept for their prototype. This involved using blank figures to symbolise women who had survived abuse. Other collaborators objected to the concept, arguing that plain white figures are not ‘blank’ but rather speak to a positioning of whiteness as the universal norm. Concerns were also raised about the use of whiteness to evoke particular emotional responses and the inferred symbolic connection between whiteness and innocence. These critiques led to a heated debate over the politics of representation, artistic licence/freedom and interpretative differences. Most importantly, it surfaced concerns over how race is sidelined within gender activism and how black people are forced to carry out ‘race work’ (Anthym & Tuitt, Citation2019).

As facilitators, we saw this debate as a pivotal moment, welcoming the friction points as key steps towards conscientização. At the same time, we recognised the importance of managing such emotionally charged exchanges. This was particularly evident when the original collaborator pushed back against the critique, labelling it a personal attack grounded in misogyny. In the end, this incident served as a learning moment that did shift how collaborators engaged with one another, even as some individuals continued to minimise the interplay between racism and other systems of oppression. As the project continued, we encouraged collaborators to bring debates such as these out into the open, using them to reflect on their learning and development, but concerns over potential embarrassment were used to avoid any public recognition of dissent or critique. For many collaborators, it was more important to share their finished prototypes than to acknowledge the contestations that informed their development. In making this point, we are not suggesting that collaborators did the wrong thing or were being deceptive. It is understandable that people prefer to share polished works rather than drafts (especially when these have been critiqued) but this tension still reveals something important about the shortcomings of arts-based projects as pedagogical and political interventions.

The limits of collaborative work

Our decision to bring together individuals with different backgrounds and skills was motivated by an interest in how these disparate perspectives might circulate among the group, hopefully leading to cross-pollination and strong inter-personal collaborations. This goal was supported by activities encouraging people to explore and respond to topics outside of their comfort zone or primary interests. Yet, as is often the case with pilot interventions, our objective landed differently than we had hoped. While some collaborators embraced the opportunity to try out new expressive modes or to engage with unfamiliar political issues, many pushed back against what they saw as a prescriptive methodology. These individuals felt that they should be allowed to stick to their preferred expressive mode and focus more on individual artworks. Given the participatory nature of the project, we felt it necessary to heed this feedback and adapt the process. Two ‘streams’ were subsequently created: collaborators who wanted to stick with the original workshop schedule were allowed to, while the others were given more freedom to work on their prototypes. This created a tension for us as facilitators: on the one hand, we were committed to a safe, comfortable and open environment for collaborators; on the other, we wanted to encourage people to learn about new ways of thinking, creating and responding – not just from us but also from each other.

Questions also need to be asked about what this negotiation really achieved. Collaborators did get to shift the direction of the learning process, but this may be an example of ‘false generosity’ (Freire, Citation1970, p. 42) – that is, moments when predetermined outcomes/processes limit real collaboration. For projects like CCoLAB, where their shape and form are approved by donors prior to any activities taking place, the potential for adaptation is constrained. Such interventions present tremendous opportunities, but the limits of their ‘participatory’ approach must be made transparent.

It is indisputable that the exhibited prototypes were striking artworks that focused attention on sexuality, gender and health. As facilitators, however, we wonder whether our goal of provoking cross-pollination was achieved. In many cases, collaborators were reluctant to draw on each other’s skills in ways that might deepen their thinking or produce new forms of creative activism. Focusing so pointedly on their individual experiences stopped some collaborators from recognising the structural dimensions of their chosen issue. This created missed opportunities for analysing and responding to sexuality, gender and health as a lived reality shaped by various social, political, cultural and emotional forces. In highlighting this tension, we do not wish to imply that collaborators refused to engage. Many formed strong bonds and assisted each other over the course of the project. Still, one must ask whether the same result could have been achieved with a short-term intervention and whether having extra resources is the best way to foster experimentation.

Aesthetics vs. activism

The final tension stems from opposing perspectives on the relationship between art and activism. The CCoLAB methodology emerged out of an interest in using creative techniques to support learning, research and advocacy. As facilitators, we see art as a vehicle for knowledge creation and dissemination, in that it can help people formulate innovative responses to social justice issues. Early on, it became apparent that some collaborators felt differently about how art can and should be used. This does not mean they were uninterested in exploring political or activist themes. Rather, some individuals preferred to produce aesthetically pleasing artworks that gestured towards social change rather than using creative expression to think critically about responding to inequality. It might be argued that some prototypes prioritised look and feel over analysis or action, although we recognise that collaborators may feel differently about this.

These contrasting priorities were felt most strongly during the lead-up to the exhibition. We encouraged collaborators to share a wide variety of artworks and reflections, but most chose to focus on aspects of their work that looked striking. For example, one participant spent a great deal of time finding the right colour tablecloth for their installation but less time focusing on the politics of their work; another focused on the costume they would wear during a short performance rather than the script they would use; and a third settled on an art technique that would lead to a polished final product but may not have conveyed their thinking in the best way.

How this tension should be understood is up for debate. As facilitators, we come to a project with specific interests, goals and expectations, and these push us to view the prioritising of aesthetics as a shortcoming, perhaps even a failing. This is very different to collaborators. From their perspective, visual impact/coherency was key to being taken seriously. Aesthetics can also contribute to their ability to move their activism forward. Regardless of one’s stance, the question remains of whether CCoLAB, with its emphasis on experimentation and collaboration, achieved its goals. The project certainly generated impressive responses to sexuality, gender and health, while also producing rich data on the lived realities of marginalised youth in South Africa, but whether it was more successful than shorter, less-resourced interventions remains to be seen.

Implications for research and activism on sexuality, gender and health

You know, it’s only in retrospect that one gets to really appreciate the significance of the programme/CCoLAB, not just to society but also at an individual level. Some of us have never really had a chance to experiment with art and also to socialise beyond racial, class and gender lines. (Andile)

Conclusion

In many ways, CCoLAB was a success: it retained a core group of collaborators who excelled in actualising their creative visions, as is attested by the powerful examples shared in this paper. However, the tensions that emerged during the process, the collaborators’ occasional critiques of the methodology and the misalignment of facilitator and collaborator visions indicate that the project did not succeed in the fullest sense of the word. But activism is always about learning – if we already had a solution to oppression, we would not need to experiment with different approaches. The ways in which collaborators pushed back against the process allowed us, as facilitators, to recognise the limits of CCoLAB, our broader praxis and dominant theoretical frames. This offers a useful opportunity to rethink the potential of long-form arts-based activism, the role of facilitators in such processes and what we might understand as failure and success within multifaceted learning processes. As facilitators, we have a responsibility to reflect critically on our project, our learning and our social locations, just as the collaborators themselves were asked to reflect on their experiences. CCoLAB, as a pilot project, offers a new direction and an adapted praxis for arts-based research. We are excited to see what can be achieved by future iterations of CCoLAB-like interventions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 ‘Coloured’ is used here to refer to a specific identity and cultural group in South Africa. The term does not carry the pejorative connotations found in other parts of the world.

2 See, for example, the video profiles from Diego, Masechaba, Sydney and Amanda, available on the CCoLAB Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/CreativeChangeLaboratory.

References

- Abdi, A. A. (2012). Decolonizing philosophies of education: An introduction. In A. A. Abdi (Ed.), Decolonizing philosophies of education (pp. 1–14). Sense Publishers.

- Ahmed, S. (2006). The non-performativity of anti-racism. Meridians, 7(1), 104–126. https://doi.org/10.2979/MER.2006.7.1.104

- Anthym, M., & Tuitt, F. (2019). When the levees break: The cost of vicarious trauma, microaggressions and emotional labor for black administrators and faculty engaging in race work at traditionally white institutions. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 32(9), 1072–1093. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2019.1645907

- Barone, T., & Eisner, E. (2012). What is and what is not arts-based research? In T. Barone, & E. Eisner (Eds.), Arts-based research (pp. 1–12). Sage.

- Bennett, J. (2011). Subversion and resistance: Activist initiatives. In S. Tamale (Ed.), African sexualities: A reader (pp. 77–100). Pambazuka Press.

- Boal, A. (1979). The theatre of the oppressed. Pluto Press.

- Chatterton, P., Fuller, D., & Routledge, P. (2007). Relating action to activism: Theoretical and methodological reflections. In S. Kindon, R. Pain, & M. Kesby (Eds.), Participatory action research approaches and methods: Connecting people, participation and place (pp. 216–222). Routledge.

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. The University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1, 139–167. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1052&context=uclf

- de Gruchy, T., Vearey, J., Opiti, C., Mlotshwa, L., Manji, K., & Hanefeld, J. (2021). Research on the move: Exploring WhatsApp as a tool for understanding the intersections between migration, mobility, health and gender in South Africa. Globalization and Health, 17(1), 71. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-021-00727-y

- Ellsworth, E. (1989). Why doesn't this feel empowering? Working through the repressive myths of critical pedagogy. Havard Education Review, 59(3), 297–324.

- Fischman, G. E. (2001). Reflections about images, visual culture and educational research. Educational Researcher, 30(8), 28–33. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X030008028

- Francis, D., & Khan, G. H. (2020). ‘I decided to teach … despite the anger': Using forum theatre to connect queer activists, teachers and school leaders to address heterosexism in schools. In D. A. Francis, J. I. Kjaran, & J. Lehtonen (Eds.), Queer social movements and outreach work in schools (pp. 237–259). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Herder and Herder.

- Hoffman, E. (2004). After such knowledge: Memory, history and the legacy of the holocaust. Secker and Warburg.

- Jackson, K., & Shanks, M. (2017). Decolonizing gender: A curriculum. Self-published zine. https://www.decolonizinggender.com/the-zine.

- Khan, G. H. (2014). Cross-border art and queer incursion: On working with queer youth from Southern Africa. Agenda (Durban, South Africa), 28(4), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2014.976043

- Luvuno, Z. P., Mchunu, G., Ncama, B., Ngidi, H., & Mashamba-Thompson, T. (2019). Evidence of interventions for improving healthcare access for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people in South Africa: A scoping review. African Journal of Primary Health Care and Family Medicine, 11(1), https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v11i1.1367

- Marnell, J., & Khan, G. H. (2016). Creative resistance: Participatory methods for engaging queer youth. Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action.

- Marnell, J., Oliviera, E., & Khan, G. H. (2021). ‘It's about being safe and free to be who you are’: Exploring the lived experiences of queer migrants, refugees and asylum seekers in South Africa. Sexualities, 24(1/2), 86–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460719893617

- Matebeni, Z. (2013). Decontructing violence towards black lesbians in South Africa. In S. Ekine, & H. Abbas (Eds.), Queer African reader (pp. 343–353). Pambazuka.

- Matebeni, Z. (2014). How not to write about Queer South Africa. In Z. Matebeni (Ed.), Reclaiming Afrikan: Queer perspectives on sexual and gender identities (pp. 56–60). Modjadji Books.

- McAllister, J. (2013). Tswanarising global gayness: The ‘unAfrican’ argument, western gay media imagery, local responses and gay culture in Botswana. Culture, Health and Sexuality, 15(1), 88–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2012.742929

- Mkhize, N. (2004). Psychology: An african perspective. In D. Hook, N. Mkhize, P. Kiguwa, & A. Collins (Eds.), Critical psychology (pp. 24–52). UCT Press.

- Moletsane, R., Mitchell, C., De Lange, N., Stuart, J., Buthelezi, T., & Taylor, M. (2009). What can a woman do with a camera? Turning the female gaze on poverty and HIV and AIDS in rural South Africa. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 22(3), 315–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518390902835454

- Motsi, R., & Masango, M. (2012). Redefining trauma in an African context: A challenge for pastoral care. HTS Theological Studies, 68(1), 96–104. http://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v68i1.955

- Nyanzi, S. (2011). Unpacking the [govern]mentality of African sexualities. In S. Tamale (Ed.), African sexualities: A reader (pp. 477–501). Pambazuka Press.

- Oliveira, E. (2016). Empowering, invasive or a little bit of both? A reflection on the use of visual and narrative methods in research with migrant sex workers in South Africa. Visual Studies, 31(3), 260–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2016.1210992

- Oliveira, E., & Vearey, J. (2016). The sex worker zine project. MoVE/ACMS.

- Omotoso, K. O., & Koch, S. F. (2018). Assessing changes in social determinants of health inequalities in South Africa: A decomposition analysis. International Journal for Equity in Health, 17(1), 181. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0885-y

- Puar, J. (2013). Rethinking homonationalism. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 45(2), 336–339. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002074381300007X

- Ratele, K. (2013). Subordinate black South African men without fear. Cahiers D'Études Africaines, 53(209/210), 247–268. https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesafricaines.17320

- Seidl-Fox, S., & Sridhar, S. (2014). Conflict transformation through culture: Peace-building and the arts. Salzburg Global Seminar report. https://issuu.com/salzburgglobal/docs/salzburgglobal_report_532.

- Seidman, J., & Schaer, C. (2011). Naledi yameso. Curriculum Development Project Trust.

- Stats, S. A. (2019). Inequality trends in South Africa: A multidimennsional diagnosic of Inequality. http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-03-10-19/Report-03-10-192017.pdf.

- Talwar, S. (2015). Creating alternative public spaces: Community-based art practice, critical consiousness, and social justice. In D. E. Gussak, & R. L. Marcia (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of art therapy (pp. 840–847). Wiley and Sons.

- Tamale, S. (2011). Researching and theorizing sexualities in Africa. In S. Tamale (Ed.), African sexualities: A reader (pp. 11–35). Pambazuka Press.

- Van der Heijden, I., Harries, J., & Abrahams, N. (2020). Barriers to gender-based violence services and support for women with disabilities in Cape Town. Disability and Society, 35(9), 1398–1418. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1690429

- Volks, C., Khan, G. H., & Alves, S. (2021). Inclusive solutions to mental health challenges: Creative resistance from the margins. In K. April, & P. Daya (Eds.), 12 lenses into diversity in South Africa (pp. 149–158). KR Publishing.

- World Health Organisation. (1948). Constitution of the World Health Organization. http://apps.who.int/gb/bd/PDF/bd47/EN/constitution-en.pdf?ua=1.