ABSTRACT

Campus sexual violence risk reduction and resistance interventions have been developed and tested among female students in the global North and proven effective. Evidence-based interventions to prevent sexual violence tested amongst female students in the global South and in South African campuses are lacking. We present preliminary evidence of promise of Ntombi Vimbela! (NV!), a sexual violence prevention intervention piloted amongst first year female students in eight purposively selected campuses in South Africa. Focus group discussions were conducted with 118 female students who participated in NV! workshops. Most students found the content of NV! relevant and reported having experienced its positive effects. They perceived that NV! empowered them with skills to assess and deal with sexual assault risky situations. NV! changed their attitudes and beliefs about gender, shifted their acceptance of rape myths and beliefs, improved communication skills, enhanced self-esteem, and confidence to defend oneself in risky sexual assault situations. Few participants were unsure whether they will be able to use the skill in real life. These findings indicate a range of short-term positive outcomes which we anticipate would reduce the risk of sexual assault among first year female students. This suggests that NV! should be subject to further evaluation.

Introduction

Research from the global North and South has shown that female students in higher education institutions are at high risk of sexual violence (Herres et al., Citation2018; Senn et al., Citation2015; Ullman & Relyea, Citation2016). More than one in four female students in Canadian and American colleges and universities have experienced sexual violence (Gidycz et al., Citation2006; Mellins et al., Citation2017; Senn et al., Citation2014). In a recent study conducted amongst selected colleges and campuses in South Africa, 20% of female students had experienced either partner or non-partner sexual victimisation, 43% experienced physical, emotional and or sexual intimate partner violence (IPV), and 20% had engaged in transactional sex in the past year (Machisa et al., Citationunpublished).

Women’s risk of sexual violence victimisation can be ascribed to a complex interplay of individual, relationship, and community-level factors (Bonar et al., Citation2020; Herres et al., Citation2018). Research, mainly from the global North, suggests that female, first year undergraduate students, particularly of low socio-economic status have an increased risk of experiencing sexual violence on campus (Campbell et al., Citation2017; Herres et al., Citation2018; Senn et al., Citation2014). Women are more vulnerable if they accept rape myths, and hold gender-inequitable views and attitudes (Aronowitz et al., Citation2012; Kalichman et al., Citation2005). This is often associated with low levels of sexual assertiveness and low self-efficacy, with the consequence that there is a lower likelihood of verbal and physical resistance when faced with sexual assault (Darden et al., Citation2019; Littleton & Decker, Citation2017; Newins et al., Citation2018).

In the United States of America, most incidents of sexual violence on campus occurred when the victim was incapacitated due to alcohol or drugs (Campbell et al., Citation2017; Ullman, Citation2016). Women have been shown to be more vulnerable to sexual assault when they are unprepared for ‘risky sexual assault’ situation (Orchowski et al., Citation2008; Senn et al., Citation2014), engaging in transactional relationships, attending social gatherings involving alcohol (Bonar et al., Citation2020; Clowes et al., Citation2009), and when the campuses have a ‘rape culture’, i.e. an environment in which sexual violence and date rape are accepted or tolerated as part of campus life (Burnett et al., Citation2009; Canan et al., Citation2018).

Evidence-based interventions to prevent sexual violence are lacking (Machisa et al., Citationunpublished; Nunze et al., Citation2019). Two campus sexual violence risk reduction and resistance interventions have been tested among female students in the Global North and proven effective in preventing rape, the self-defense training and the Enhanced Assess, Acknowledge, Act (EAAA) Sexual Assault Resistance program (Hollander, Citation2014; Senn et al., Citation2015).

Research consistently shows that active resistance using any form of physical resistance (forceful or non-forceful) is associated with rape avoidance and that resistance does not increase or decrease physical injury, rather, injury is likely caused by the initial physical attack (Hollander, Citation2014; Senn et al., Citation2014; Citation2015). Forceful verbal resistance is effective when the offender is using verbal threats than non-forceful verbal resistance which has been shown to be ineffective (Hollander, Citation2014; Senn et al., Citation2014; Citation2015). Contextual and environmental factors may present as barriers to effective implementation of rape resistance strategies. These include being intoxicated by alcohol which may impair women’s judgement and mobility, psychological barriers such as fear of embarrassment and social rejection which make women less likely to use resistance strategies if the offender is someone they know (Gidycz & Dardis, Citation2014; Rozee & Koss, Citation2001).

While risk reduction and resistance approaches to sexual violence prevention are increasingly recognised as potentially effective, the resistance approach has been criticised for being victim blaming and perceived as placing the responsibility to prevent rape on women, implying that it is their fault if they were unable to exercise personal agency to stop the rape (Mardorossian, Citation2002). Mardorossian (Citation2002) further argues that these approaches suggest that rape and its prevention is about women who are raped rather than about men who perpetrate. Others argued that self-defense programming restricts women’s freedom by increasing their fearfulness and avoidance of risky situations (See Gidycz & Dardis, Citation2014 critical review).

Sexual violence risk reduction and resistance approach are not designed to make women responsible for the rape but to provide them with information that enables early recognition of behaviours of potential perpetrators and contexts in which sexual violence risk is exacerbated (Hollander, Citation2014; Senn et al., Citation2018). It enhance women’s freedom by equipping them with strategies they can use to assess risk of sexual violence, acknowledge when the situation is dangerous, label it as such, and acting using resistance strategies (Hollander, Citation2014; Rozee & Koss, Citation2001; Senn et al., Citation2018). It is based on the observation that women are more likely to resist rape when they are equipped with skills to anticipate risk and strategies to apply when a potential threat is detected (Hollander, Citation2014; Rozee & Koss, Citation2001; Senn et al., Citation2018).

Over the last two decades research has shown that rape resistance poses no increased risk of injury for women, and does not promote violence amongst women (Gidycz & Dardis, Citation2014; Rozee & Koss, Citation2001; Senn et al., Citation2015). Women who resist are less likely to have the rape completed against them than women who do not resist (Hollander, Citation2014; Senn et al., Citation2015; Wong & Balemba, Citation2018). Furthermore, women who participate in self-defense training have an enhanced sense of self-efficacy and agency as they are more confident in their ability to effectively resist sexual violence than similar women who have not taken such a class (Hollander, Citation2014; Senn et al., Citation2018). Even in situations where women resist but do not avoid rape, research has shown that they feel better and blame themselves less than those who do not resist (Gidycz et al., Citation2015; Senn et al., Citation2015). Having the skills to assess risk and to resist sexual violence does not imply that the burden for preventing sexual violence lies with women, as men are responsible for sexual violence and ultimately their behaviour must change if we are to stop rape completely (Hollander, Citation2014; Rozee & Koss, Citation2001; Ullman, Citation2020). Those who advocate for rape resistance approaches are of the view that it is vitally important that men are taught about rape and its consequences, how to interact with women respectfully, and that social norms no longer promote men’s sexual entitlement and patriarchal privilege (Gidycz & Dardis, Citation2014; Ullman, Citation2007). However, until men stop perpetrating rape, rape resistance advocates argue that women need to be empowered to resist sexual violence (Gidycz et al., Citation2006; Rozee & Koss, Citation2001).

While limited research focusing on campus sexual violence interventions has been conducted in South Africa, it is widely acknowledged that these are much needed. Such research responds to key national priorities focused on prevention which have been identified in the recently developed National Policy Framework to address Gender-Based Violence (GBV) in post school education sector and the National Strategic Plan on GBV and Femicide in South Africa (Department of Higher Education and Training, Citation2020; Republic of South Africa, Citation2020).

Ntombi Vimbela! (NV!) [Ntombi means girl or woman, Vimbela means to prevent, resist or restrain, or deter in isiXhosa and IsiZulu] is a sexual violence risk reduction intervention which has a self-defense component delivered through a series of 10 workshops and targets female students in HEIs aged 18–30 years (Machisa et al., Citationunpublished; Nunze et al., Citation2019). The10 NV workshops run for 35 h (3.5 h each session) of which 7 h are for self-defense training conducted over 2 workshops. Ntombi Vimbela! was developed and tested in a pilot in South Africa. This article presents preliminary findings of the research conducted among first year female students who participated in a pilot of the NV! in five South African Technical and Vocational Education and Training Colleges (TVETs) and three university campuses. South African tertiary education is divided into two, TVETs which focus more on skill transfer, programmes are shorter and qualifications includes national certificates and diplomas; and universities which focus more on transfer of knowledge, programmes are longer, and offer degrees and postgraduate qualifications. The pilot was conducted to establish the relevance and usefulness of the content, and to gather participants’ experiences of the intervention. The Ntombi Vimbela!’s intervention, its development process, including its underpinning theory of change and logical framework is described elsewhere (Machisa et al., Citationunpublished; Nunze et al., Citation2019).

Methods

Description of the Ntombi Vimbela! intervention

Ntombi Vimbela! is a manualised sexual violence risk reduction intervention with a self-defense component. Ntombi Vimbela! was developed and pilot tested amongst first year female students in TVETs and universities in South Africa (Machisa et al., Citationunpublished; Nunze et al., Citation2019). Ntombi Vimbela! is designed to (1) raise awareness about sexual rights, violence against women and girls and its drivers; (2) to sensitise about gender inequality and sexual assault, and build more gender equitable beliefs; (3) to equip participants with skills to assess and act in situations where there is a risk of sexual assault; (4) to build resilience and skills to withstand social and material pressures in college or university; (5) to enable utilisation of health, psycho-social services and access to justice for survivors; (6) to enhance communication skills and building healthy sexual relationships: and (7) to promote mental health, coping and build empathy towards survivors (Machisa et al., Citationunpublished; Nunze et al., Citation2019). NV! comprises of 10 sessions of 3.5 h each, delivered by two trained facilitators per group. It is intended to be facilitated in groups of 15–20 young women by peer women of a similar age (18–30 years), trained and experienced in facilitation. The sessions cover (1) Introductions, risk and safety; (2) Communication skills; (3) Sex, rights and consent; (4) Love and relationships; (5) Intimate partner violence, sexual violence and supporting survivors; (6) Stress, depression and well-being skills; (7) Assessing sexual assault risk; (8&9) Resisting sexual assault and (10) Material pressures and budgeting (Machisa et al., Citationunpublished; Nunze et al., Citation2019).

Ntombi Vimbela! is delivered using participatory learning approaches, critical reflection, and role play to enhance learning and to allow participants to reflect on personal risk and to equip them with strategies they can use to reduce the risk of sexual violence (Machisa et al., Citationunpublished; Nunze et al., Citation2019). The facilitator introduces the topics and allow participants the opportunity to build new understanding and ways of seeing, through reflecting on their own ideas and life experience rather than imposing a version of what that way of thinking should be (Machisa et al., Citationunpublished; Nunze et al., Citation2019). The facilitator draws out knowledge and ideas from the group and help participants learn from each other using participatory group methods including brainstorming in a bigger group; small group discussions, working in pairs and feeding back group ideas to the bigger group (Machisa et al., Citationunpublished; Nunze et al., Citation2019). Report backs during sessions allow participants to practice speaking in front of their peers during the sessions. The self-defense training is conducted over two sessions to allow participants time to learn and practice self-defense skill in a safe space, rehearse and get feedback from trained facilitators (Machisa et al., Citationunpublished; Nunze et al., Citation2019).

Ntombi Vimbela!’s development was informed by formative research conducted in South African campuses and drew on evidence-based interventions, namely Stepping Stones, Creating Futures, SASA! and Enhanced, Assess, Acknowledge and Act (EAAA) (Abramsky et al., Citation2014; Jewkes et al., Citation2014; Senn et al., Citation2015). We borrowed relevant sessions and delivery methods from the evidence-based interventions as they fitted the specific session and exercise. In the adaptation, we ensured that sessions are relevant to the South African context and lives of female students in higher education (Machisa et al., Citationunpublished; Nunze et al., Citation2019). Sessions were made to be cognitively relevant and engaging for the target population. The intervention content was tailored to ensure that the language, visuals, examples, scenarios and activities were appropriate for the target population (Machisa et al., Citationunpublished; Nunze et al., Citation2019). The research team also developed new content unique to life changes associated with adapting to higher education environment and enhancing mental well-being. NV!’s content was drafted and refined through a peer-review process and also incoporating feedback from female students and staff who were recruited to be part of the development process and become facilitators for the intervention (Machisa et al., Citationunpublished; Nunze et al., Citation2019).

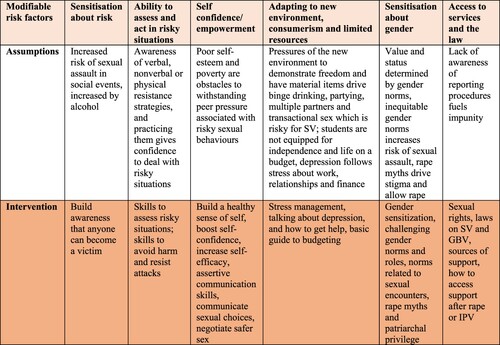

Stepping Stones and Creating Futures are gender transformative interventions designed to promote gender equitable relationships and to empower participants with skills to improve their relationships (Jewkes et al., Citation2014). The exercises on relationships, sex and consent, communication, and violence (sessions 2, 3, 4 and 5) are adapted from the Stepping Stones and Creating Futures. SASA! is a community mobilisation intervention that seeks to change community attitudes, norms and behaviours that result in gender inequality, violence and increased HIV vulnerability for women (Abramsky et al., Citation2014). We also drew from the SASA! intervention to inform development of NV! sessions which focused on changing norms, attitudes and behaviours that contribute to gender inequality, violence and vulnerability for women (sessions 4 and 5). Session 6 was informed by formative research findings and feedback from female students and staff who participated in the early development phase, responds to life changes associated with adapting to higher education environment and the associated mental ill-health issues. EAAA is a sexual assault resistance education program which teaches women to assess situations for risk, acknowledge risky situations, and to verbally and physically act in risky situations. It is designed to enhance women’s ability to resist acquaintance sexual assault and shown to be effective in reducing the incidence of rape up to one-year later amongst women with and without past history of rape (Senn et al., Citation2015). We drew from EAAA and developed NV! sessions on risk and safety, risk assessment acknowledgement and resistance (sessions 1, 7, 8 and 9). Session 10 of NV! draws from Creating Futures and feedback from female students and staff used to develop exercises on life skills and better managing finances as one strategy to withstand material pressure on campus. NV! was also developed after formative research by the study team with first year female students at seven tertiary institutions, which informed the theory of change, shown as follows:

Piloting Ntombi Vimbela!

The Ntombi Vimbela! pilot was conducted in eight purposively selected TVET (five campuses) and university campuses (three campuses) across five provinces in South Africa: in the Eastern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal, Limpopo, Gauteng and Mpumalanga Provinces. The study sites were selected with the input of the National Department of Higher Education and Training (NDHET) and management committees of the selected institutions. The selected campuses were situated in both urban and rural locations, therefore catering to diverse student populations. Seventeen trained peer facilitators recruited first year students between 18 and 30 years of age who gave written consent to participate in the NV! pilot (Machisa et al., Citationunpublished; Nunze et al., Citation2019). The facilitator teams of two conducted the ten NV! workshops in eight selected campuses between August and October 2019, in venues that allowed for privacy, and at workshop times agreed with the participants (Machisa et al., Citationunpublished; Nunze et al., Citation2019).

Risk and empowerment

Sexual violence risk refers to the likelihood that one may be sexually victimised. Sexual violence risk is reduced when a woman is able to detect risky situation, resist or reduce the likelihood of victimisation (Gidycz et al., Citation2006; Hollander, Citation2014). Empowerment refers to a process of becoming more confident after being equipped with skills, making women think differently about themselves in relation to others. Women are described as empowered when they are confident and believe that they possess the skill to detect and respond in a potentially threatening situation without having to avoid social interaction (Gidycz & Dardis, Citation2014).

Data collection

End of intervention focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted with participants in each of the eight sites, facilitated by female members of the research team. Of the 118 participants who participated in NV! workshops, 96 (81%) attended the end of intervention FGDs. A semi-structured FGD guide was used to structure the discussion which lasted between 1–2 h. The FGDs were conducted in both English and vernacular languages spoken by participants in each site. The FGDs explored participants’ views about the relevance and usefulness of NV! content, their experiences of participation, shifts in participants’ knowledge, gender attitudes and practices, and sought their thoughts on the gaps in NV! and other recommended areas for improvement. To assess relevance of the intervention, participants were asked: Were the topics discussed in Ntombi Vimbela! relevant to your lives? Which were these and how relevant were they? Was any content not relevant for you? What did you find not relevant? What other topics should have been covered to make Ntombi Vimbela! more relevant for young women like you? What would you have loved to have more of? Participants were also asked to reflect on the content and materials: What did you think about the activities in the exercises, how they were organised or ordered? What materials or content was difficult, embarrassing or stressful for you? Participants were also asked: If and how the session/intervention made them think or see things differently? What they learnt in Ntombi Vimbela! and started to use in their life? What they learnt in Ntombi Vimbela! that they are finding hard to implement in their lives and relationships and why?

Data analysis

Research assistants translated the FGD audio recordings into English and transcribed them verbatim. The translated and transcribed audios were checked by PM and MM for accuracy. Data were analysed inductively using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Transcripts were read repeatedly, and initial codes developed based on the FGD guide. The first (PM) and second (MM) authors used the codes to develop a codebook. Following this stage, PM and MM reviewed and tested the applicability of the codebook using the raw data from the transcripts, which led to the expansion of codes. Next, PM, MM, YS and NN coded text which seemed to fit under specific codes (Nowell et al., Citation2017). Further to this, PM, MM, YS and NN explored the data and identified numerous open codes. Similar open codes were grouped together under defined categories (Nowell et al., Citation2017). Last, PM, MM, YS and NN explored the relationships between the categories and interpreted what they saw emerging (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). PM, MM, YS and NN discussed and selected quotes that illustrate the point, and are representative of the dominant patterns in the data from both the TVETs and university campuses (Lingard, Citation2019). Quotes which were representing participant’s views about areas where they thought the intervention might not work were also considered in the analysis and included in the results.

Ethical considerations

Ethics approval for the study was granted by the South African Medical Research Council’s Human Research Ethics Committee. Approval to conduct the research in the selected sites was granted by the NDHET and by management in the selected TVETs and universities. All research participants signed informed consent. Participants were reimbursed R50 for their participation in the FGDs.

Results

Nine emergent themes were generated from the analysis of data: relevance of NV! to female students, expressed changes in gender attitudes including shift in rape myths, changes in assessment of sexual assault risk, improved communication skills, change in self-confidence, awareness of sexual rights and sexual communication, change in confidence in one’s ability to protect oneself, perceptions about physical self-defense skills, and journey to healing.

Relevance of content of Ntombi Vimbela!

The majority of students indicated that NV! was relevant and that they could already experience its positive effects on different aspects of their lives, as the following quote shows:

Everything that we did here [workshops] was relevant, like it was relating to everything that is happening in our lives starting from the beginning, I won`t mention everything one by one but knowing that we were talking about sexual violence which most of us have experienced. (FGD, University)

Ok the NV! program is relevant based on the things that are happening around the campus, things such as rape, so it is relevant because it gave us some defense mechanisms that we can use if one faces one of those incidences that happen around the campus so I could say that it is relevant. (FGD, University)

Those things [sexual assault risky situations] are happening in our daily lives … especially about the danger cues, we were not aware of them but now at least we know how to identify them, and how to see when you are in danger. (FGD, TVET)

Yes, there is this other topic that for me was relevant, I don’t think I will ever forget about it even if I could be asked about it on my sleep! The one about the danger cues. There have been situations where we go out as friends and we meet people out there and they ask to join us, but before attending this program I did not have a problem with that but now I know that when someone you do not know comes and ask to join you and buy you few drinks of alcohol, sometimes they even say let’s change the spot, let’s go seat there or even ask you to accompany him somewhere, now I know that`s a danger cue because you do not know that person so that could be danger to you. (FGD, TVET)

Another participant described: I found the discussion on assertive communication very relevant. I think is important because as young women sometimes we are not clear in our communication and that makes us vulnerable and people taking advantage, doing things we do not want. (FGD, University)

Moreover, what most participants found particularly relevant was information about strategies they could use to remove themselves from risky sexual assault situations. None of the participants had previously attended self-defense training, so most appreciated the new knowledge and skills they gained through NV! They considered that it was important for them to learn self-defense skills, in the light of the environment in which they lived. One participant explained:

I have learnt how to defend myself maybe when there is a thug following me or in case, I get hijacked. These are the skills one needs to know. (FGD, University)

I also say yes, because by coming here [NV! workshop] we found out that the things that were discussed are the things that we face in our lives outside here, like our families, communities and in our relationships. So, we were equipped on how we can handle such things and how to defend ourselves when we find ourselves in such situations maybe when we are being attacked. (FGD, TVET)

You see I think we should talk more about hygiene because we are growing up, we get sexually active and sometimes there are diseases that are being sexually transmitted and when they get to one’s body they do not sit well, so you need to talk about sexual hygiene especially to girls in general. (FGD, TVET)

Things like PrEP were not discussed or things like how to regularly check yourself as a female looking out for STÌs and STD`s and maybe just touching base on that and how we can avoid those things or just a brief description of how we can try and keep healthy as possible. (FGD, University)

I would have loved to hear more about contraceptives. I think we are not given enough clarity about how contraceptives work (FGD, TVET)

Change in gender attitudes

The NV! intervention impacted attitudes and beliefs about gender relations. In the FGDs, some students demonstrated enhanced empowerment and challenged social norms that support gender inequality. They talked about how they now saw themselves as equal to men and were able to make their own decisions without seeking permission from men. The quote below is illustrative:

Ok, I feel like we can actually equalize ourselves with men and even be higher, what they can do, even better because wève empowered ourselves to that point of knowing that we can do anything that we put our minds to we don’t need any approval from men, we do what we want. (FGD, University)

The expectations on young women by the society, when I started joining this group some of the things started happening and I was able to see them. I remember at home there was a meeting and they asked me about my age then I told them that I am 24 years old, they said it’s time for me to find someone that loves me and get married. I was so surprised about the marriage part because therès lot of things that I [still] need to do. They also asked me if my baby daddy is maintaining my baby and I said yes, so they suggested that I move in with him because they hope that we get married. They do not care about how I planned my life so they have their expectations towards me. Now I am able to tell them that I matter first before everyone else and they should understand that I make such decisions about my life. And the person that they want me to get back to, was very abusive so now if I go back there that would mean I am signing my death penalty … that is what I learnt here. (FGD, TVET)

Before coming here [workshop] I thought that women are raped because of how they dress, now I know, that is not the case. (FGD, University)

No, I’m not the same because I used to think that women who are raped, who are abused, it’s because they wanted to because if they did not, they should have walked away but now I realized that there is more that is happening, some women can`t walk away because their men are breadwinners and some need a lot of things, so yah. (FGD, University)

Ntombi Vimbela! sought to enhance awareness about sexual assault risk and protective strategies and many participants shared how NV! had enhanced their knowledge about violence against women and empowered them with strategies to use to assess risky situations. The narrative to follow is illustrative:

Ok, the sexual assault thing [session] I think it worked so much that even the danger cues that they told us about, some of them I did not really know if they were cues or things just happening in general after that lesson or session now I actually know more than I did and what I would do if I would find myself in a similar situation. (FGD, University)

Yes, there is this other topic that I loved so much; I don’t think I will ever forget it even if I could be asked about it on my sleep! The one about the danger cues. There have been situations where we go out as friends and we meet people [men] out there and they ask to join us, but before attending this program I did not have a problem with that, but now I know that when someone [a man] you do not know comes and asks to join you and buy you few drinks of alcohol, sometimes they even say let’s change the spot, let’s go sit there or even asks you to accompany him somewhere, now I know that`s a danger cue because you do not know that person so that could be a danger to you. (FGD, TVET)

There are also the danger cues that I also learnt about here in this program, that when I go out to a club, [I have to use] my money … ok [now] I have this tendency of going out to a club with my own money to buy my own alcohol, I do not expect someone to buy me alcohol and when I want to go home I tell her and she should do the same then we take a taxi and we go, you see. (FGD, TVET)

Improved communication skills

Ntombi Vimbela! sought to equip participants with skills to assertively communicate in intimate relationships, as well as in relationships with family, peers and others. In the workshops, participants were also taken through a process of reflection aimed to bring awareness about barriers to assertive communication, and how to overcome them. In the FGDs, many participants spoke of having overcome their fear of expressing themselves, and that they were now able to raise issues they previously found difficult to talk about in their relationships:

I learnt about the ‘I’ statement where you are able to tell the next person when you do not like something, I was not able to express myself when I do not like something, I would keep quiet because I don’t want to disappoint them but at the end of the day I would end up being the one who gets disappointed because of that, so now I have learnt a lot. (FGD, TVET)

Communicating assertively, I even told him that no let`s stop this [relationship] and just end it because of this and that, and if we were meant to be, we can still date in the upcoming years because I don’t want anything that will bother me emotionally. (FGD, TVET)

No I am not the same girl, I use to be like this stubborn girl who doesn’t want to [listen], like if you did something I wouldn’t want to hear your side as to why you did it and those I statements, but at least now I can listen that you did what you did because of whatever and at least I can understand but if it was that time [before attending NV! workshop], if yoùve wronged me, eish … Ìm matured now. (FGD, TVET)

While others have learned to express their point without being aggressive, I have learnt that you can also talk to a person without being aggressive towards them and make them understand what you are saying to them, so yes, we learnt a lot here. (FGD, TVET)

Participant: The ‘I statement’, I can use it to other people, but to my parents it’s hard.

Interviewer: Why do you think it’s hard?

Participant: Because it’s difficult to have a conversation with these people [parents], they do not want you to backchat to them and won’t give you what you ask them. (FGD, TVET)

I have gained confidence through this program, now I am able to stand in front of people and I have grown through this program in many ways. (FGD, University)

‘I was lacking confidence so by coming here it was boosted’

One of the objectives of NV! is to reassure women of their worth, regardless of the difficult experiences they had including surviving rape or experiencing intimate partner violence. Participants were taken through exercises where they learned about self-worth, their bodies, and how to appreciate them. Several participants said NV! challenged them to love and appreciate themselves and to not internalise negative criticism they receive from other people. This improved self-worth is best illustrated in one participant’s assertion that:

And also this thing maybe your boyfriend told you that there is no man that can ever want you, you find out that now you are stressed and have low self-esteem. Now you do not have to listen to that, but you have to love yourself more. (FGD, TVET)

When I first came here [NV! workshop] I was lacking confidence, by coming here it was boosted. (FGD, TVET)

I had a problem of [low] self-esteem, struggling with what to wear because I worry about how people look at me because of the structure of my body, I know a lot of people like to comment about my big bums, so that made me to be less confident and I would be scared to walk in front of people because of that, but when I got here [workshop] they taught me to be free and comfortable about what I am wearing and forget about what others are saying as long as I feel good about myself when I look at myself in the mirror, that`s all that matters … yes, you should see me when I walk, I walk with confidence and have no stress. (FGD, TVET)

‘No, it does not work like that, if you don’t want [sex] then you do not want’

Participants’ understanding of sexual rights and bodily rights was enhanced. They became more confident and were able to assert themselves in negotiating sexual encounters:

If I don’t want to have sex with a man, I have a right to say no and refuse. I also have a right to wear whatever I want [to wear] at any given time. I learnt [in the workshop] about unwanted touches and sexual harassment as well as issues in relations to rape, I also learnt to speak freely. (FGD, TVET)

I learnt that if you have a partner that does everything for you he does not have a right to … let’s say just because he takes care of you now when he wants to have sex with you even if you don’t feel like it, because he does for you, no it does not work like that, if you don’t want [sex] then you do not want. (FGD, TVET)

Confidence in the ability to defend oneself

For most participants, the NV! sessions that focused on how to verbally and physically resist sexual assault enhanced confidence that they would be able to resist and remove themselves from sexual assault risky situations. One participant explained:

So, this [self-defense session] really worked, and I feel more comfortable because now at least I know how to defend myself. Like my expectations compared to what we did here have been met. I have learnt about how to defend myself. (FGD, University)

I would advise another woman to join this [NV!] group because it empowers you as a young woman and it uplifts your self-confidence and to know how to defend yourself in any case or situation that you face. (FGD, TVET)

You know sometimes I was scared to even go out but now I have that courage because at least … you know, now I am so cool, I was even scared in class guys, if I go to study alone and a guy [man] come in, I would be scared and shake and decide to just go, but now I’m more confident. (FGD, University)

Some participants had started using the self-defense skills they have learned from NV! They extract below evidence:

Yes, like yesterday my boyfriend tried hurting me, and I did the whole thing of grabbing the balls [testicles] … He was shocked and asked ‘ … what are you doing’? (FGD, University)

We were taught how we can defend ourselves when a perpetrator comes to you trying to rape you, but we were not taught on how we can defend ourselves when he has a weapon. (FGD, TVET)

It’s going to be difficult when I am scared. (FGD, TVET)

The part of self-defense, I feel that it could be difficult for me to implement it because when you are in that situation you do not need to look brave to the attacker because they might be very rough on you seeing that you are fighting back. (FGD, University)

I can`t say always because you might never know the person who might attack you might overpower you but at least you have some skills. (FGD, University)

The journey to healing through talking and seeking help

Many participants said they had never spoken about, nor sought professional help in dealing with, the painful and traumatic events they experienced, including rape in childhood or while enrolled in higher education. NV! workshops enabled some participants to realise the importance of sharing and not ‘bottling-up’ their traumatic experiences. As reflected in the extract below:

I was also able to share my personal story [in the workshop] about my experience where I was abused by someone I dated, so that [workshop] is where I noticed that I can speak now and have stopped bottling up things. (FGD, TVET)

Growing up I would have loved to have someone to talk to about my problems, someone that you can trust and would give you advice, so this program brought us such people, sisters. Now I know that if I have a problem, I can share it with one of them and it will be kept confidential, they will give me advice and listen to me when I need that. (FGD, University)

The reason I joined this program is because of what I went through when I first came here at X university, I was sexually assaulted, so the program has helped me to be able to speak out and I was able to deal with the emotions even though it did not get to the point of legal actions so I could say I was able to let it go through this program and I was able to let it go. (FGD, University)

It [NV!] has helped me because there are things that we shared here that were private, hurting me, that I shared and learnt to let bygones be bygones. (FGD, TVET)

I would say yes because it is rare for us to get such chances as girls, such as counselling, as a result if something has happened to you, you keep it to yourself and not knowing who to talk to about it, so by coming here we also received counselling in a way. (FGD, TVET)

Ok, it was hard to talk about the past because it was reminding me of what happened but now I feel free so I am happy about these sessions and I also wish that it can continue so that even other people can know about it so that they can be relieved and be able to speak up about their problems and get peace of mind. (FGD, TVET)

We explored the data to understand why participants experienced the workshop as supportive. The participants suggested that the manner in which confidentiality was maintained in the workshop made them perceive the workshop as a safe space in which to disclose their painful experiences and expect empathy and not ridicule or be gossiped about. The following narratives evidence this:

If you maybe share a story and then the next session when you come to attend they don’t look at you and judge you because of what you shared, they are always fine as if nothing happened and that is what gave me the power because they did not judge me or look at me as if they have questions they are all right and I feel free around them. (FGD, TVET)

What I noticed about this group is that we all kept to the confidentiality, ever since I got here I have never heard of … ok maybe there are those who have but on my side, I have never heard even in my class of people talking about someone else’s story outside, not even a single day. Even conflicts here, I have never noticed someone arguing with the other person here. (FGD, TVET)

Discussion

By analysing data from the pilot with female students in campuses in South Africa, we were able to assess how participants experienced Ntombi Vimbela!, if and how specific elements of Ntombi Vimbela! equipped participants to deal with sexual violence risky situations. Students found the content of NV! relevant, appropriate for the settings, indicating promise in reducing individual-level risk factors of sexual violence victimisation among first year female students. Data also suggest NV!’s potential promise in improving communication skills, transforming gender attitudes and beliefs, shifting rape myths, and enhancing awareness about sexual rights and body autonomy. Participants reported enhanced awareness about sexual assault risk and gained verbal and physical resistance skills. Some felt confident to use, while others were not sure they would be able to do so.

The change in gender attitudes and beliefs reported by participants shows that NV! is gender transformative. The findings point to a shift towards gender equitable views, a shift in acceptance of rape myths, and greater support and empathy towards survivors of sexual violence. These positive changes were achieved through participants critically reflecting on social and gender norms that increase women’s risk to sexual violence victimisation cf. Kerr-Wilson and colleagues (Kerr-Wilson et al., Citation2020). We have shown that a few participants had started critical reflection and challenging some of the practices in their families that endorse gender-power imbalances. Critical reflection allows people to appraise and reappraise themselves in ways that improve their life situations (MacPhail & Campbell, Citation2001; Shai et al., Citation2017). The positive effect of Ntombi Vimbela! was also noted in how the use of participatory methods during intervention delivery created a safe space for participants to share, even about painful experiences and to develop emotionally supportive relationships with others (Stern et al., Citation2020).

Our findings show that NV! participants improved their communication skills, which positively impacted their relationships with peers and intimate partners, enabling them to be more expressive about what they want and do not want (Jewkes et al., Citation2010). Moreover, assertive communication skills learned in NV! enabled participants to verbally resist sexual and other unwanted behaviours from others. Assertive communication of sexual desires is associated with a reduced risk of sexual coercion and victimisation (Beres, Citation2010; Krahé et al., Citation2000). These findings are consistent with those of the Stepping Stones evaluation in the rural Eastern Cape province which showed improved communication skills amongst participants who attended the Stepping Stones workshops (Jewkes et al., Citation2010).

It is important to note, however, that, assertive communication was difficult to use when students were communicating with their parents. This can be understood through Sikweyiya and Jewkes (Citation2009) who contend that many black African communities and families in South Africa are organised hierarchically by age and gender, with the utmost authority entrusted to older people. It could be that young women were cautious that assertive communication could be perceived as being rude and disrespectful to elders.

Ntombi Vimbela! empowered participants with knowledge about situations that expose women to risk of sexual assault, and provided women strategies they can use to assess and remove themselves from risky sexual assault situations. These finding are consistent with what was found in other risk reduction interventions which showed improved women’s assessment of the risk of sexual assault by male acquaintance, ability to acknowledge danger, and to resist unwanted sexual behaviours of men whom they know (Senn et al., Citation2015). Improved assessment of sexual assault risk and ability to act was associated with reduction of incidence of completed rape amongst Canadian first year female students (Senn et al., Citation2015). To our knowledge, NV! is amongst the first few risk reduction and resistance interventions developed and pilot tested amongst first year female students in colleges and universities in sub-Saharan Africa.

Ntombi Vimbela! bolstered women’s self-efficacy to remove themselves from potential sexual violence risk situations, indicating preliminary evidence of promise, consistent to risk reduction interventions that included self-defense (Hollander, Citation2014; Senn et al., Citation2015). The self-defense skills acquired through NV! improved participants' confidence that they will be able to act and remove themselves form risky situations. Furthermore, a few participants said they had started to use assertive communication and self-defense tactics to resist unwanted sexual advances from their partners. When followed-up, women who utilised active resistance strategies were less likely to be victimised (Senn et al., Citation2017).

Although the experience of self-defense skills through NV! was empowering for most, a few women had concerns whether they will be able or remember to use these skills in real-life situation. This pilot study was limited in that the timing of the FGDs minimised our ability to further understand actual use of acquired self-defense skills in real life by most women. Future research is needed to explore this over time. The findings from this pilot show positive short-term outcomes in the direction as has been observed in other evaluations of effective evidence-based risk reduction and resistance interventions. The impacts of NV! must be determined through a well-designed impact evaluation with a control group. Not having a control group in the pilot of NV! limited our ability to compare to other similar women and make conclusions about impact of the intervention. There is a potential of respondent bias given that the FGDs were conducted by researchers who were involved in the design of NV!, who also analysed the data. This might have introduced potential power dynamics. Future impact evaluation will involve a neutral person who will not be part of the research team involved in the design of NV!.

Conclusion

The pilot has highlighted preliminary evidence of promise of Ntombi Vimbela!, a sexual violence risk reduction and resistance intervention targeting first year female students in South African higher education settings. It shows promise in female student’s empowerment, gender transformation and sexual assault risk reduction, aswell as being relevant, appropriate for campus settings, and suggesting some impact in reducing individual-level risk factors of sexual violence victimisation among first year female students. Risk reduction and rape resistance approaches show promise and are critical in reducing individual-level risk factors of sexual violence victimisation. However, to holistically address gendered violence there is a need to intervene at other levels of the socio-ecological model (Heise, Citation1998). For instance, at the societal level, it is important to address structural drivers of sexual violence perpetration including customary laws around male inheritance, socio-cultural norms that promote women’s subjugation, income, social and gender inequality, and normalisation of violence (Fulu et al., Citation2013; Gibbs et al., Citation2020).

Acknowledgements

Our sincere gratitude goes to all the study participants, the peer facilitators, and the National Department of Higher Education and Training that supported this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abramsky, T., Devries, K., Kiss, L., Nakuti, J., Kyegombe, N., Starmann, E., … Musuya, T. (2014). Findings from the SASA! study: A cluster randomized controlled trial to assess the impact of a community mobilization intervention to prevent violence against women and reduce HIV risk in Kampala, Uganda. BMC Medicine, 12(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-014-0122-5

- Aronowitz, T., Lambert, C. A., & Davidoff, S. (2012). The role of rape myth acceptance in the social norms regarding sexual behavior among college students. Journal of Community Health Nursing, 29(3), 173–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370016.2012.697852

- Beres, M. (2010). Sexual miscommunication? Untangling assumptions about sexual communication between casual sex partners. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 12(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050903075226

- Bonar, E. E., DeGue, S., Abbey, A., Coker, A. L., Lindquist, C. H., McCauley, H. L., … Ngo, Q. M. (2020). Prevention of sexual violence among college students: Current challenges and future directions. Journal of American College Health, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2020.1757681

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Burnett, A., Mattern, J. L., Herakova, L. L., Kahl Jr, D. H., Tobola, C., & Bornsen, S. E. (2009). Communicating/muting date rape: A co-cultural theoretical analysis of communication factors related to rape culture on a college campus. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 37(4), 465–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909880903233150

- Campbell, J. C., Sabri, B., Budhathoki, C., Kaufman, M. R., Alhusen, J., & Decker, M. R. (2017). Unwanted sexual acts among university students: Correlates of victimization and perpetration. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(1--2), NP504–NP526. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517734221

- Canan, S. N., Jozkowski, K. N., & Crawford, B. L. (2018). Sexual assault supportive attitudes: Rape myth acceptance and token resistance in Greek and non-Greek college students from two university samples in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(22), 3502–3530. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516636064

- Clowes, L., Shefer, T., Fouten, E., Vergnani, T., & Jacobs, J. (2009). Coercive sexual practices and gender-based violence on a university campus. Agenda (Durban, South Africa), 23(80), 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2009.9676236

- Darden, M. C., Ehman, A. C., Lair, E. C., & Gross, A. M. (2019). Sexual compliance: Examining the relationships among sexual want, sexual consent, and sexual assertiveness. Sexuality & Culture, 23(1), 220–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-018-9551-1

- Department of Higher Education and Training. (2020). Policy framework to address gende-based violence in the post School Education and Training system. Goverment printers. www.dhet.gov.za.

- Fulu, E., Jewkes, R., Roselli, T., & Garcia-Moreno, C. (2013). Prevalence and risk factors for male perpetration of intimate partner violence: Findings from the UN multi-country study on men and violence in Asia and the pacific. The Lancet Global Health, 1(4), e187–e207. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70074-3

- Gibbs, A., Dunkle, K., Ramsoomar, L., Willan, S., Jama Shai, N., Chatterji, S., … Jewkes, R. (2020). New learnings on drivers of men’s physical and/or sexual violence against their female partners, and women’s experiences of this, and the implications for prevention interventions. Global Health Action, 13(1), 1739845. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2020.1739845

- Gidycz, C. A., & Dardis, C. M. (2014). Feminist self-defense and resistance training for college students: A critical review and recommendations for the future. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 15(4), 322–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838014521026

- Gidycz, C. A., Orchowski, L. M., Probst, D. R., Edwards, K. M., Murphy, M., & Tansill, E. (2015). Concurrent administration of sexual assault prevention and risk reduction programming: Outcomes for women. Violence Against Women, 21(6), 780–800. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801215576579

- Gidycz, C. A., Rich, C. L., Orchowski, L., King, C., & Miller, A. K. (2006). The evaluation of a sexual assault self-defense and risk-reduction program for college women: A prospective study. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30(2), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2006.00280.x

- Heise, L. L. (1998). Violence against women: An integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women, 4(3), 262–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801298004003002

- Herres, J., Wang, S. B., Bobchin, K., & Draper, J. (2018). A socioecological model of risk associated with campus sexual assault in a representative sample of liberal arts college students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(7--8), NP4208–NP4229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518785376

- Hollander, J. A. (2014). Does self-defense training prevent sexual violence against women? Violence Against Women, 20(3), 252–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801214526046

- Jewkes, R., Gibbs, A., Jama-Shai, N., Willan, S., Misselhorn, A., Mushinga, M., … Skiweyiya, Y. (2014). Stepping Stones and Creating Futures intervention: Shortened interrupted time series evaluation of a behavioural and structural health promotion and violence prevention intervention for young people in informal settlements in Durban, South Africa. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 1325. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1325

- Jewkes, R., Wood, K., & Duvvury, N. (2010). ‘I woke up after I joined Stepping stones’: Meanings of an HIV behavioural intervention in rural South African young people's lives. Health Education Research, 25(6), 1074–1084. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyq062

- Kalichman, S. C., Simbayi, L. C., Kaufman, M., Cain, D., Cherry, C., Jooste, S., & Mathiti, V. (2005). Gender attitudes, sexual violence, and HIV/AIDS risks among men and women in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Sex Research, 42(4), 299–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490509552285

- Kerr-Wilson, A., Gibbs, A., McAslan Fraser, E., Ramsoomar, L., Parke, A., Khuwaja, H., & Jewkes, R. (2020). A rigorous global evidence review of interventions to prevent violence against women and girls. What works to prevent violence among women and girls global programme.

- Krahé, B., Scheinberger-Olwig, R., & Kolpin, S. (2000). Ambiguous communication of sexual intentions as a risk marker of sexual aggression. Sex Roles, 42(5-6), 313–337. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007080303569

- Lingard, L. (2019). Beyond the default colon: Effective use of quotes in qualitative research. Perspectives on Medical Education, 8(6), 360–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-019-00550-7

- Littleton, H., & Decker, M. (2017). Predictors of resistance self-efficacy among rape victims and association with revictimization risk: A longitudinal study. Psychology of Violence, 7(4), 583–592. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000066

- Machisa, M., Mahlangu, P., Sikweyiya, Y., Shai, N., Nunze, N., Dartnall, E., … Jewkes, R. (unpublished). Mapping the process of development of Ntombi Vimbela intervention, a sexual violence risk reduction intervention for female students in South African tertiary education institutions.

- MacPhail, C., & Campbell, C. (2001). I think condoms are good but, aai, I hate those things’:: Condom use among adolescents and young people in a southern African township. Social Science & Medicine, 52(11), 1613–1627. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00272-0

- Mardorossian, C. M. (2002). Toward a new feminist theory of rape. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 27(3), 743–775. https://doi.org/10.1086/337938

- Mellins, C. A., Walsh, K., Sarvet, A. L., Wall, M., Gilbert, L., Santelli, J. S., … Benson, S. (2017). Sexual assault incidents among college undergraduates: Prevalence and factors associated with risk. PloS one, 12(11), e0186471. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186471

- Newins, A. R., Wilson, L. C., & White, S. W. (2018). Rape myth acceptance and rape acknowledgment: The mediating role of sexual refusal assertiveness. Psychiatry Research, 263, 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.02.029

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- Nunze, N., Machisa, M., Mahlangu, P., Sikweyiya, Y., Pillay, M., Chirwa, E., … Jewkes, R. (2019). Developing a sexual gender based violence intervention targeting female students in south African tertiary institutions: Mapping the process. Paper presented at the Sexual Violence Research Initiative Forum 2019, Cape Town.

- Orchowski, L. M., Gidycz, C. A., & Raffle, H. (2008). Evaluation of a sexual assault risk reduction and self-defense program: A prospective analysis of a revised protocol. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32(2), 204–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00425.x

- Republic of South Africa. (2020). National Strategic Plan on Gender-Based Violence and Femicide. Pretoria, South Africa: Government printers https://www.justice.gov.za/vg/gbv/NSP-GBVF-FINAL-DOC-04-05.pdf.

- Rozee, P. D., & Koss, M. P. (2001). Rape: A century of resistance. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 25(4), 295–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-6402.00030

- Senn, C. Y., Eliasziw, M., Barata, P. C., Thurston, W. E., Newby-Clark, I. R., Radtke, H. L., & Hobden, K. L. (2015). Efficacy of a sexual assault resistance program for university women. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(24), 2326–2335. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1411131

- Senn, C. Y., Eliasziw, M., Barata, P. C., Thurston, W. E., Newby-Clark, I. R., Radtke, H. L., … Team, S. S. (2014). Sexual violence in the lives of first-year university women in Canada: No improvements in the 21st century. BMC Women's Health, 14(1), 135. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-014-0135-4

- Senn, C. Y., Eliasziw, M., Hobden, K. L., Newby-Clark, I. R., Barata, P. C., Radtke, H. L., & Thurston, W. E. (2017). Secondary and 2-year outcomes of a sexual assault resistance program for university women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 41(2), 147–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684317690119

- Senn, C. Y., Hollander, J. A., & Gidycz, C. A. (2018). What works? Critical components of effective sexual violence interventions for women on college and university campuses sexual assault risk reduction and resistance. (pp. 245–289) Elsevier.

- Shai, N., Sikweyiya, Y., van der Heijden, I., Abrahams, N., & Jewkes, R. (2017). I was in the darkness but the group brought me light": development, relevance and feasibility of the sondela HIV adjustment and coping intervention. PloS one, 12(6), e0178135. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178135

- Sikweyiya, Y., & Jewkes, R. (2009). Force and temptation: Contrasting South African men's accounts of coercion into sex by men and women. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 11(5), 529–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050902912783

- Stern, E., Willan, S., Gibbs, A., Myrttinen, H., Washington, L., Sikweyiya, Y., … Jewkes, R. (2020). Pathways of change: Qualitative evaluations of intimate partner violence prevention programmes in Ghana, Rwanda, South Africa and Tajikistan. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2020.1801843

- Ullman, S. E. (2007). A 10-year update of “review and critique of empirical studies of rape avoidance”. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 34(3), 411–429. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854806297117

- Ullman, S. E. (2016). Sexual revictimization, PTSD, and problem drinking in sexual assault survivors. Addictive Behaviors, 53, 7–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.09.010

- Ullman, S. E. (2020). Rape resistance: A critical piece of all women’s empowerment and holistic rape prevention. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2020.1821851

- Ullman, S. E., & Relyea, M. (2016). Social support, coping, and posttraumatic stress symptoms in female sexual assault survivors: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 29(6), 500–506. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22143

- Wong, J. S., & Balemba, S. (2018). The effect of victim resistance on rape completion: A meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 19(3), 352–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838016663934