ABSTRACT

The Prevention of Mother-to-child Transmission (PMTCT) of HIV program in Zambia has undergone several policy iterations over the past 10 years. This qualitative study aimed to contribute towards addressing this knowledge gap by analysing the evolution and actors’ influence during the policy process using the Walt and Gilson policy triangle as our evaluation framework. Document review and key informant interviews with policy makers were undertaken to identify the contextual factors that had shaped the PMTCT policy evolution in Zambia. Overall, the study revealed that over the past decade, at least five PMTCT policy changes have occurred, averaging three years per policy with extensive overlap between policies. This resulted in more than two policies being implemented at a given time. Pressure from the international community and scientific evidence were the main drivers of policy change in Zambia, with local actors being mainly reactive. Among international agencies, UNICEF and WHO were the key actors who had driven the policy changes as they had the power and resources. The rapid changes, negatively impacted the health system, disrupted service delivery, which was unprepared to effectively and efficiently shift from one policy to another.

Introduction

The Prevention of Pother-to-Thild Transmission (PMTCT) of HIV programme is a public health intervention primarily implemented to reduce transmission of HIV from the mother to the child through the provision of antiretroviral treatment (ART) to both HIV-infected pregnant/postpartum women and prophylaxis treatment to exposed babies (Chiya et al., Citation2018) (UNEP, Citation2014). Although some countries have attained low mother-to-child transmission of HIV (MTCT) rates in sub-Saharan Africa, several others, including Zambia, are still behind (Gumede-Moyo et al., Citation2019).

Zambia’s antiretroviral coverage of pregnant women living with HIV was 92% [78–>95] in 2017, a slight decrease from 95% in 2015 (UNAIDS, Citation2018). There are currently approximately 1.2 million people living with HIV in Zambia; 94,000 of these individuals are children under the age of 15 (Qiao et al., Citation2018).

At the global level, policies guiding PMTCT implementation have undergone considerable rapid changes in response to World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations (Chiya et al., Citation2018; UNAIDS & WHO, Citation2009). These changes were mainly accelerated in 2011 with the launch of the UNAIDS ‘Global Plan towards the elimination of new HIV infections among children by 2015 and keeping their mothers alive’ (UNAIDS, UNICEF & World Health Organization, Citation2011). However, progress towards the global targets has varied considerably from one country to another and over the past 10 years, the field has seen rapid and often controversial policy changes (Mutabazi et al., Citation2017).

In the context of Zambia, the need for a clear policy to support HIV/AIDS interventions was realised soon after the government announced that HIV/AIDS was a major health, economic and social concern in 1999. Since then, the country has formulated and implemented various policy changes with support from several local stakeholders and external partners.

The rapid policy changes, however, have not been accompanied by health system research to understand the health system preparedness, particularly programme feasibility and economic concerns (Coutsoudis et al., Citation2013). The 5-year PMTCT country report conducted by the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and supported by African Development Bank found that there were many policies formulated and implemented. However, in certain cases, policies and practices did not match due to the non-consideration of time to implement new policies resulting in mixed implementation or overlapping of the guidelines (SADC, Citation2009). The report further stated that while the HIV and PMTCT programmes have demonstrated the need for additional trained staff, the policies to make these available are not in harmony; leading to a situation where these programmes are run by fewer staff and sometimes by staff with lower skills than required (SADC, Citation2009).

Other studies conducted elsewhere have shown that the rapid implementation of PMTCT policy guidelines resulted in increased workload and negatively affected health workers’ motivation (Naburi et al., Citation2017; Nguyen et al., Citation2009). Hence, it is critical to understand the evolution and impact of rapid changes in PMTCT policy and guidelines in Zambia and draw lessons for future programming.

This study therefore aimed at contributing towards addressing the knowledge gap by analysing the evolution and actors’ influence during the policy process using the Walt and Gilson policy triangle as our evaluation framework (Citation1994). Using this framework, we aimed to identify the contextual factors that had shaped the PMTCT policies, to analyse the policy processes, actor involvement, their relationship and the power structures that were at play during the PMTCT policy evolution, and to identify and analyse the content of the available government policy documents and literature.

Method

Study setting

The Zambian health system is comparatively centralised, with the Ministry of Health (MOH) headquarters responsible for formulating national health policies as well as direct oversight of the general health sector in the country. As a result, all in-depth interviews were conducted with national-level respondents only from the public (MOH) and private sector. Respondents for this study were drawn from Lusaka, the capital city of Zambia.

Study design

This was a qualitative study that employed document review and in-depth interviews to collect data. We analysed the content, context, process, including actors, relationships and power structures that were at play during PMTCT policy evolution in Zambia.

Document review

The first step in data collection involved the review of documents in terms of content (effectiveness and feasibility), process (consultation, political context, actors, policy gains), context (drive for policy change, capacity, policy problem, cost) and actors (power). To achieve this, we reviewed relevant policy documents and literature. This process also assisted with the identification of players who were involved in the PMTCT policy processes. Several strategic records and documents were reviewed, covering the period between 2006 and 2021. These documents were identified through the MOH website and included health sector review reports, national health strategic plans, PMTCT policy guidelines, Zambia National HIV/AIDS guidelines and published literature relevant to PMTCT in Zambia. These are outlined in .

Table 1. Documents reviewed.

In-depth interviews (IDIs)

The document review guided the selection of the key informants. Key informants were invited to participate if they were listed in the documents as actively participating in the policy-making process or if, based on the document review, they were reasonably expected to have participated in the PMTCT policy process. Key informants were also identified using purposive sampling techniques, by asking each informant after the interview if they knew anyone else who would have information related to the study. The key informants identified were then contacted either physically at their office or electronically through email or phone call and asked to participate in the study. If they agreed, an appointment was set. Written consent for all interviews and audio recordings was obtained for all interviews conducted. In total, 15 key informants from the national level in the health sector were interviewed. In-depth interview guides were developed for each category of respondents (Ministry of Health, Implementing partners, muiltilateral agencies, Researchers/Consultants) ().

Table 2. Key Informants interviewed for the study.

Data collection

We conducted face-to-face interviews with key informants from both the public sector and private organisations relevant to HIV/AIDS in Zambia, particularly those associated with PMTCT policy formulation and implementation.

Data collection for this study was carried out between February 2019 and July 2020. All IDIs were conducted in English by the first author and transcribed verbatim to word files. On average, the interviews took 30–45 min to complete. Transcriptions were performed by the researcher and research assistants.

Data analysis

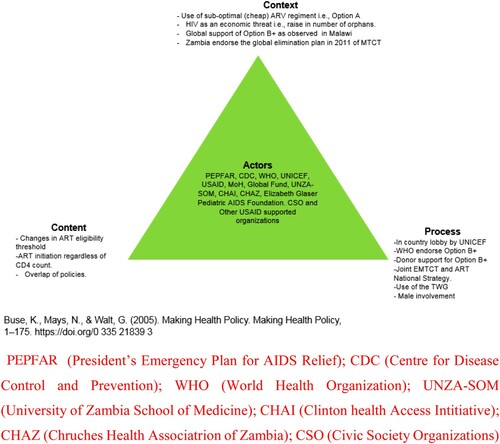

Data were analysed through thematic content analysis (Donovan, Citation2016). Walt and Gilson’s Policy Triangle Framework was used, and it focused on four fields: content, context, process and actors who play a critical role in policy formulation (Gilson & Raphaely, Citation2008). Interview transcripts were entered into Nvivo 12 Pro software, a qualitative analysis software that aids in managing data ideas, data queries, data visualisation and data reporting (Brandão et al., Citation2015). The data was reviewed several times and coded thematically using concept and data-driven coding by coding the transcripts according to pre-defined codes from the policy analysis framework and also identifying other themes emerging from the data. The policy analysis triangle framework was populated with findings from the study, as illustrated in .

Table 3. Selected codes, categories and themes for the data analysis.

Firstly, all the documents were read for familiarisation of the content. Special attention was paid to the content of the documents that were addressing mother-to-child transmission of HIV/, actors involved in the policy process and their roles, Option B+ and test and treat (if included) to establish the relevance of that document to the study. A summary (annotation) of the document was then made. After this, the document was read more critically to identify the key concepts (codes) in the documents. Thereafter, key concepts identified were categorised according to the broad idea that they represented. These categories were then analysed manually and grouped according to the predetermined themes from the policy analysis framework. The categories that were developed from the document analysis were the ones that were applied to the data from the key informant interviews.

Ethics

Ethical clearance for the study was granted by the Tropical Diseases Research Centre Ethics Review Committee, reference number(s) TRC/C4/04/2018, TRC/C4/08/2020 and the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) clearance certificate number M180228. Interviews were conducted in private, and informed consent processes were followed with written consent being provided. Permission was sought before the recording of the interviews. Data were managed, stored, analysed and presented in a manner that ensured full confidentiality.

Results

shows the key findings of the study according to the Walt and Gilson Policy Analysis Triangle Framework (Walt & Gilson, Citation1994).

Figure 1. The key findings of the study according to the framework. Source: PEPFAR (President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief); CDC (Centre for Disease Control and Prevention); WHO (World Health Organization); UNZA-SOM (University of Zambia School of Medicine); CHAI (Clinton health Access Intitiative); CHAZ (Chruches Health Associatrion of Zambia); and CSO (Civic Society Organizations).

Content and focus of the Zambian consolidated guidelines for prevention and treatment of HIV infections

The document review demonstrated several changes and overlaps in the content of different guidelines between 2006 and 2021. In 2006, Zambia introduced Option A and recommended ART initiation of pregnant women based on clinical staging WHO stage 3/4 and daily Zidovudine (AZT) Monotherapy. Option A regimen included AZT starting at 14 weeks gestation. It was followed by a single dose of Nevirapine (sd-NVP) and AZT/ Lamivudine (3TC) at delivery for seven days postpartum for mother and daily NVP from birth until one week after breastfeeding cessation or 4–6 weeks if not breastfeeding (MOH, Citation2006). The guidelines were then revised in 2010, with recommendations for Option A and Option B. Unlike option A, option B allows HIV-positive women to receive maternal triple ARV prophylaxis from 14 weeks gestation through 1week postpartum, sd-NVP at delivery, and daily 3TC from delivery through 1 week postpartum (MOH, Citation2006). The cluster of Differentiation Four (CD4) based antiretroviral therapy (ART) eligibility threshold gradually increased from 200 cells/μL in 2006 (MOH, Citation2006) to 350 cells/μL in 2010 (MOH, Citation2010).

In 2013, the country introduced Option B+. In this policy guideline, Option B remained operational, while Option B+, which consisted of a triple ARV regimen, was initiated at first contact at a health facility to all HIV-positive pregnant and breastfeeding women regardless of CD4 cell count and was continued for life whilst their infants received daily NVP or AZT from birth to 4–6 weeks (MOH, Citation2013). One respondent noted

We had a mix of PMTCT policies running at the same time despite knowing that Option B had better mother to child transmission of HIV outcomes than Option A. This was because of limited resources, we could only afford Option A in some places and then where we had a bit more resources, we did Option B. (Key informant # 2)

In 2018, the general UTT policy was updated with a directive to initiate ART on the day of HIV diagnosis (MOH, Citation2018). New ARV drugs such as Atazanavir (ATV-r) or Lopinavir (LPV) were introduced as an alternative regimen to replace the 2016 recommendation of NVP for HIV-positive pregnant and breastfeeding mothers (MOH, Citation2018). The guidelines also recommended universal routine HIV testing for all pregnant and breastfeeding women who did not know their status (MOH, Citation2018).

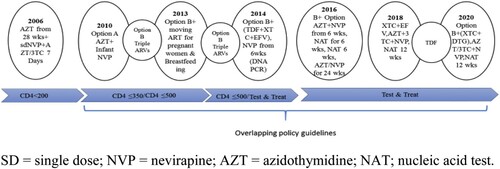

The current guidelines (Citation2020) provide further changes. For instance, individuals who have tested positive for HIV will have their sample tested for recency of HIV in order to determine whether they are recently infected or have long-term HIV. The new guidelines further recommend new ARV agents such as Darunavir-ritonavir (DRV-r) as part of second-line HIV treatment while emphasising the use of newer agents like Dolutegravir (DTG), Tenofovir Alafenamide (TAF) and Efavirenz-400mg (EFV), and introduction of Darunavir-ritonavir (DRV-r) dosed as 800mg/100mg, as a part of the Second-Line regimen for adults (MOH, Citation2020). shows a description of PMTCT Policy changes over time in Zambia.

Contextual factors in PMTCT policy development in Zambia

The documents reviewed suggest that the HIV context was urgent, and mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of HIV was a crucial driver of infection. According to the 2010 HIV/AIDS guidelines, the overall adult HIV prevalence was 14 per cent and 1.6 per cent of the adult population became newly infected each year (MOH, Citation2010). To counter the increasing HIV infection rate among infants and young children in the country, the PMTCT programme and the National PMTCT Technical Working Group (PMTCT-TWG) were created in 1999 (Kankasa et al., Citation2018). The PMTCT-TWG was tasked with coordinating the policy change using new evidence which was rapidly generated (MOH, Citation2017). The policy change was influenced by both internal and external contextual factors. Internal contextual factors included; increased number of orphans and the high mortality of women due to the scourge of HIVas observed by an informant;

PMTCT program was initially started to protect children who were dying like insects because most of them had lost their mothers due to HIV/AIDS. Option A which the country had adopted then despite being a inexpensive option was difficult to implement due to changes in drugs and CD4 requirements. (Key Informant #3)

Malawi was one of the countries where evidence for successful implementation of Option B+ was solid. Evidence suggested that the regimen was efficacious, easy to implement, cost effective and removed CD4 cell threshold for ART eligibility, although that came with its challenges. (Key Informant # 3)

Policy process

The key step in the process of developing PMTCT policy and guidelines was the consultative workshop which was held in April 2014 (Kieffer et al., Citation2014) with some of the key international and local stakeholders who are part of the PMTCT - TWG. While several key informants postulated that the MOH led the agenda-setting within the PMTCT-TWG, they also claimed that, ‘the process of rapid policy changes and moving towards option B+ was initiated by UNICEF who engaged government on what WHO was proposing in the global health community’ (Key Informant #3).

Another informant added,

UNICEF role was to sit down and engage government on what WHO was recommending on HIV policy guidelines. UNICEF’s interest was in the welfare of the child, thus, theyprovided technical assistance and funded the policy adoption and scaling up, (Key Informant #3)

During the PMTCT-TWG meetings, various local and international evidence is taken into consideration before PMTCT policy drafts. However, most of the evidence is generated by partners and very limited by the government, (Key Informant #6)

This policy process sometimes starts with WHO or USG who would make certain recommendations to the TWG for review and consideration. Whatever is agreed by the TWG is forwarded to the Ministry of Health for consideration and approval. However, the policies take a long time to trickle to the end users who are base facilities. (Key Informant #3)

Participants’ views noted that the MOH itself exerted the most influence in the policy process. However, a strong civil society and involvement of the community and frontline staff were critical to initiating and sustaining the process, as noted by a key informant who claimed that ‘during the formulation and implementation of health policies, all concerned stakeholders, governance issues, and other related policies are considered and used to guide new policy’ (Key Informant #5).

Having a pool of different stakeholders on board necessitated a coordination mechanism to guide the process. Hence, a sustainably funded coordination mechanism called the National AIDS Council (NAC) was created to facilitate the formulation process, as noted by a key informant:

If there is a coordinating body like we have NAC it should be well funded and our strategies should be built from a multisectoral approach starting from the community. Once people in the village understand what we want to achieve as a nation, implementing different PMTCT policies won’t be a challenge. (key Informant #5)

Men’s lack of involvement in PMTCT and lack of support supervision to primary health care facilities during the implementation of new policies by higher authorities were cited as hindering programme implementation outcomes at the facility-level and among newly infected women. One key informant from an international organisation observed that there are ‘few women who have not tested, and if they have tested, some are not consistent with collecting their ARVs. An issue which I think borders on disclosure to their partners’ (Key Informant #5).

Document review revealed that the country experienced policy overlaps, meaning different policies were being implemented at different health facilities due to the non-consideration of health system requirements across the continuum of care. As one informant observed:

There have been cases where development of new policies is underway when similar ones are still in draft form awaiting approval. We also had situations where two different policies were running concurrently. That created confusion, especially that rapid changes do not consider other health system requirements to implement the new shift. (Key informant # 6)

Furthermore, donor support to the policy process and implementation has continued to be the largest contributor to HIV funding, at 85.6 per cent in 2015, increasing very slightly to 85.8 per cent in 2017. The biggest donor source was direct bilateral funding mostly driven by PEPFAR funding (65 per cent of the total in 2017), (PEPFAR, Citation2019; NAC, Citation2019) followed by multilateral agencies (20 per cent of which 19 per cent was from the global fund) while international not-for-profit organisations formed just under 1 per cent (NAC, Citation2019).

Actors involved in the policy process

The major actors in the development of the policy guidelines were the PMTCT-TWG working through the MoH. The TWG sets the agenda in the development of the PMTCT guidelines; however, the decision on what components will comprise the final document is decided by the MoH. Actors drawn from the stakeholders in the health sector were mainly involved during the consultative workshops which are organised through the TWG where the draft policy is developed. The majority of the respondents described stakeholder participation through the TWG consultative meetings as active. The TWG is composed of representatives from the Department of Paediatrics, University Teaching Hospital; Elizabeth Glaser Paediatric AIDS Foundation; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia (CIRDZ); The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; UNICEF; MOH; WHO; Population Council; Institute of Economic and Social Research, University of Zambia and the Zambia Prevention Care and Treatment Partnership (Kankasa et al., Citation2018).

The roles of the actors that were identified by informants and through document review are UNICEF and WHO, who have provided advocacy and technical support. According to an Informant;

WHO provided the expertise, evidence, and global guidelines for countries to adopt and domesticate. UNICEF on the other hand supported the core activities such as policy process, developing and printing of guidelines, protocols, funding key meetings, support supervision, training of staff on Option B+/test and treat and procurement of the drugs during the initial beginning of the PMTCT program, a situation that changed after the coming of USAID/PEPFAR, CDC and Global Funds. (Key Informant 5)

However, according to some respondents, the sustainability of the PMTCT programme was a concern for many actors due to the programme’s heavy reliance on donor support. One respondent asserted that;

What will happen in an event of reduced donor support? Even with the existence of donor support, we still experience policy implementation challenges such as inadequate financial resources, support supervision, national stock-outs of ARVs and lab logistics (DBS Cards, HIV Test Kits, and lab reagents) which impact negatively on the health system and service delivery. (Key informant # 13)

Finally, according to informants, post-Option B+ implementation, the USG has a major influence among other stakeholders because they provide substantial funding for ARVs in Zambia (). Total spending on HIV in Zambia by source between 2010 and 2012.

Table 4. Total spending on HIV in Zambia by source between 2015 and 2017.

Discussion

Our findings reveal that over the past decade, at least 5 PMTCT policy changes occurred in Zambia, with extensive overlap between policies resulting in more than one policy being implemented at a given time. Document review established that the HIV context was urgent and MTCT is one of the key drivers of the HIV epidemic (Kankasa et al., Citation2018; WHO, Citation2013). Similar findings were observed in other studies (Chi et al., Citation2020; Muyunda et al., Citation2020). Consequently, the PMTCT programme and the PMTCT-TWG were created in 1999 to coordinate policies using new evidence which was being generated rapidly (Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation, Citation2013).

The policy changes were influenced by internal and external contextual factors such as the increased number of orphans and high mortality of women due to the scourge of HIV (Jamison et al., Citation2006) and the country adoption of a cheaper alternative (Option A) which was difficult to implement (WHO, Citation2012). the HIV/AIDS pandemic posed a big threat to the economy and prosperity of the country because of its negative impact on the human resource base (ILO, Citation2005). This was also evident from studies conducted in other Low-Middle-Income countries (Chersich et al., Citation2018; Doherty et al., Citation2017).

Consistent with other findings (Coutsoudis et al., Citation2013; Tenthani et al., Citation2014), this study found that Zambia’s endorsement of the global call to lifelong ART treatment and evidence of Option B+ implementation outcomes in Malawi formed the momentum for rapid policy changes (Harries et al., Citation2016).

Our findings further suggest that the policy process of PMTCT in Zambia began through a consultative process with key international and local stakeholders through the PMTCT-TWG. Evidence from document review and key informant interviews further suggests that while the MOH exerted the most influence in the policy process, international organisations such as UNICEF, WHO, USAID/PEPFAR and CDC influenced the process due to considerable funding linked to the policies they propagate.

While positive results in the implementation of different PMTCT policies overtime have been noted in the literature, such as reduction of MTCT of HIV at population-level, protection of HIV-negative male partners, improved maternal and infant health and increased ARV coverage (Coutsoudis et al., Citation2013), majority of local stakeholders and actors felt the changes were too rapid and impacted negatively on the health system and service delivery. For instance, the implementation of Option B+ resulted in national stock-outs of ARVs and lab logistics (DBS Cards, HIV Test Kits and lab reagents). Similar concerns were raised by different public health experts and organisations at the international level from different studies (Coutsoudis et al., Citation2013; Nsagha et al., Citation2012; MSF, Citation2016).

Other far-reaching consequences included lack of supportive supervision to primary health care facilities during the implementation of new policies by higher authorities which was attributed to inadequate transport and lack of resources. Our results confirm findings from other studies done on Option B+ implementation in Africa (Chersich et al., Citation2018; Doherty et al., Citation2017; Gamell et al., Citation2017; Mutabazi et al., Citation2017). Similarly, previous studies contend that there remained reservations from primary healthcare (PHC) providers that health system capacity constraints may limit same-day ART policy assimilation and result in variations in implementation at the facility level (Onoya et al., Citation2020).

Furthermore, respondents revealed that guidelines delay trickling to the end-users who are base facilities, and that when new policies are being implemented, they tend to be limited to facilities with well-established infrastructure. This meant that other facilities lagged in implementing the guidelines. Similar findings have been documented in other studies (Kalua et al., Citation2017; Kim et al., Citation2013).

Overall, it is apparent that the global health community and scientific evidence were the main drivers of policy change in Zambia. Among international agencies, UNICEF (Chersich et al., Citation2018; Doherty et al., Citation2017) and WHO were the key actors and had largely driven the policy changes in the country which other studies (Chersich et al., Citation2018; Doherty et al., Citation2017) described as having stemmed from the firm relationship around technical support, their readiness to fund policies they promoted and power to influence change.

This study has highlighted that critical elements of the health system required to implement PMTCT policies were dependent on donor support. Thus, the findings in this study imply that the current scenario in which PMTCT guidelines are formulated and implemented is inadequate for the Zambian setting. Continued and intensified use of the TWG for consultation, use of local health system data and experiences from Option B+ implementation in Malawi, which shares similar characteristics with Zambia, to support policy shifts may be important considerations in future policy changes.

There is a need for the government and stakeholders to invest in tools and systems such as feedback through frontline staff and managers on the operation of a current policy programme to generate local data to guide the development of comprehensive and relevant policies. The government also needs to strengthen the health system capacity to absorb future rapid PMTCT policy changes and possibly give each guideline a specific timeline it can be implemented and evaluated before new evidence is considered.

Study limitation

Given that we examined events that happened several years back, there is a risk of recall bias or loss of institutional memory among informants and actors and also accessing the respondents for interviews. To mitigate this, we included people who were no longer in the targeted institutions.

Conclusion

The country has achieved tremendous gains in the scaling up of different guidelines on PMTCT from the time it was launched. However, sustaining these gains through rapid policy changes has proved to be detrimental to the cause. It is thus imperative that the health system’s readiness for such changes be considered and proper measures set in place to facilitate the change.

Furthermore, future policy development and implementation must take into consideration local actors’ views and prepare the health system when scaling up new interventions for any health condition to minimise health system gaps.

Consent for publication

Consent to publish this work was obtained from the Ministry of Health.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank all national-level informants who volunteered to participate in this study and shared their experiences. The authors also thank the MOH Zambia for the permission to conduct this study, and UNC-UNZA-Wits Partnership for HIV and Women’s Reproductive Health (UUW) Ph.D. training programme.

Data availability statement

The dataset supporting this analysis is not available as the key informant interviews contain information that would make the participants identifiable, compromising their confidentiality.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Brandão, C., P. Bazeley, & K. Jackson. (2015). Qualitative data analysis with NVivo (2nd ed.). Qualitative Research in Psychology, 12(4), 492–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2014.992750

- Chersich, M. F., Newbatt, E., Ng’oma, K., & de Zoysa, I. (2018). UNICEF’s contribution to the adoption and implementation of option B+ for preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV: A policy analysis. Globalization and Health, 14(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-017-0319-4

- Chi, B. H., Mbori-Ngacha, D., Essajee, S., Mofenson, L. M., Tsiouris, F., Mahy, M., & Luo, C. (2020). Accelerating progress towards the elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: A narrative review. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 23(8), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25571

- Chiya, H. W., Naidoo, J. R., & Ncama, B. P. (2018). Stakeholders’ experiences in implementation of rapid changes to the South African prevention of mother-to-child transmission programme - As experiências das partes interessadas na implementação de mudanças rápidas na prevenção da África do Sul do programa. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 10(1), e1–e10. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v10i1.1788

- Coutsoudis, A., Goga, A., Desmond, C., Barron, P., Black, V., & Coovadia, H. (2013). Is option B+ the best choice? Southern African Journal of HIV Medicine, 14(1), 8–10. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhivmed.v14i1.94

- Doherty, T., Besada, D., Goga, A., Daviaud, E., Rohde, S., & Raphaely, N. (2017). “If donors woke up tomorrow and said we can’t fund you, what would we do?” A health system dynamics analysis of implementation of PMTCT option B+ in Uganda. Globalization and Health, 13(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-017-0272-2

- Donovan, D. (2016). Mental health nursing is stretched to breaking point. Nursing Standard, 30(25), 33. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.30.25.33.s40

- Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation. (2013). Zambia policy analysis for the elimination of pediatric HIV.

- Gamell, A., Luwanda, L. B., Kalinjuma, A. V., Samson, L., Ntamatungiro, A. J., Weisser, M., Gingo, W., Tanner, M., Hatz, C., Letang, E., Battegay, M., & Charpentier, C. (2017). Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV Option B+ cascade in rural Tanzania: The One Stop Clinic model. PLoS One, 12(7), e0181096. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181096

- Gilson, L., & Raphaely, N. (2008). The terrain of health policy analysis in low and middle income countries: A review of published literature 1994-2007. Health Policy and Planning, 23(5), 294–307. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czn019

- Gumede-Moyo, S., Todd, J., Schaap, A., Mee, P., & Filteau, S. (2019). Increasing proportion of HIV-infected pregnant Zambian women attending antenatal care are already on antiretroviral therapy (2010-2015). Frontiers in Public Health, 7(JUN), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00155

- Harries, A. D., Ford, N., Jahn, A., Schouten, E. J., Libamba, E., Chimbwandira, F., & Maher, D. (2016). Act local, think global: How the Malawi experience of scaling up antiretroviral treatment has informed global policy. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3620-x

- International Labour Organization. (2005). Policy paper on educational perspectives related to the impact of HIV / AIDS on child labour in Zambia. ILO.

- Jamison, D. T., Breman, G. J., Measham, R. A., Alleyne, G., Claeson, M., Evans, B. D., Jha, P., Mills, A., & Musgrove, P. (2006). Disease control priorities in developing countries (2nd ed., Vol. 48, Issue 6). World Bank and Oxford University Press. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/7242

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). (2017). HIV prevention 2020 road map. Accelerating prevention to reduce new infections by 75%. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/hiv-prevention-2020-road-map_en.pdf%0Ahttp://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/hiv-prevention-2020-road-map_en.pdf.

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). (2018). UNAIDS data 2018. UNAIDS. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2018/unaids-data-2018.

- Kalua, T., Barr, B. A. T., Van Oosterhout, J. J., Mbori-ngacha, D., Schouten, E. J., Gupta, S., Sande, A., Zomba, G., Lungu, E., Kajoka, D., Tih, P., Jahn, A., Clinic, L., Union, I., Tuberculosis, A., Disease, L., Development, C., Convention, B., & Services, H. (2017). Lessons learned from option B+ in the evolution toward “Test and Start” from Malawi, Cameroon, and the United Republic of Tanzania. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 75(Suppl 1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001326

- Kankasa, C., Simbaya, J., Musokotwane, K., Nambao, M. C., Yam, E., Moyo, T., Phiri, L., Kalibala, S., & Moonga, A. (2018). Evaluation of the prevention of mother-to- child transmission of HIV program in Zambia, 1(1), 48. Unpublished manuscript.

- Kieffer, M. P., Mattingly, M., Giphart, A., Van De Ven, R., Chouraya, C., Walakira, M., Boon, A., Mikusova, S., & Simonds, R. J. (2014). Lessons learned from early implementation of option B+: The Elizabeth Glaser pediatric aids foundation experience in 11 African countries. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 67(Supplement 4), S188–S194. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000372

- Kim, Y. M., Chilila, M., Shasulwe, H., Banda, J., Kanjipite, W., Sarkar, S., Bazant, E., Hiner, C., Tholandi, M., Reinhardt, S., Mulilo, J. C., & Kols, A. (2013). Evaluation of a quality improvement intervention to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) at Zambia defence force facilities. BMC Health Services Research, 13(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-1

- Kunguma, O., & Ncube, A. (2016). Combating HIV and/or AIDS: A challenge to millennium development goals for disaster managers in the Southern African development community. Jamba: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies, 8(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4102/jamba.v8i2.173

- Médecins Sans Frontières. (2016, April). Out of focus: How millions of people in West and Central Africa are being left out of the global HIV Response.

- Ministry of Health. (2006). Scale-up plan for HIV care and antiretroviral therapy services (Issue May). Government of the Republic of Zambia.

- Ministry of Health. (2010). Adult and adolescent antiretroviral therapy protocol. Government of the Republic of Zambia.

- Ministry of Health. (2012). Business case for an improved eMTCT protocol in Zambia moving to option B+ (Issue November). Government of the Republic of Zambia.

- Ministry of Health. (2013). Zambia consolidated guidelines for treatment and prevention of HIV infection. December, 1–57. Republic of Zambia.

- Ministry of Health. (2016). Consolidated guidelines for treatment and prevention of HIV infection. Government of the Republic of Zambia. https://aidsfree.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/zambia_hiv_gl2016.pdf

- Ministry of Health. (2017). Zambia national health strategic plan 2017–2021. 172. https://www.medbox.org/countries/zambia-national-health-strategic-plan-2017-2021/preview%0Ahttp://www.moh.gov.zm/docs/ZambiaNHSP.pdf

- Ministry of Health. (2018). Zambia consolidated guidelines for prevention and treatment of HIV infection. Government of the Republic of Zambia.

- Ministry of Health. (2020). Zambia guidelines for treatment and prevention of HIV infection. Government of the Republic of Zambia.

- Mutabazi, J. C., Zarowsky, C., & Trottier, H. (2017). The impact of programs for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV on health care services and systems in sub-Saharan Africa – A review. Public Health Reviews, 38(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-017-0072-5

- Muyunda, B., Musonda, P., Mee, P., Todd, J., & Michelo, C. (2020). Effectiveness of lifelong ART (Option B+) in the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV programme in Zambia: Observations based on routinely collected health data. Frontiers in Public Health, 7(January), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00401

- Naburi, H., Mujinja, P., Kilewo, C., Orsini, N., Bärnighausen, T., Manji, K., Biberfeld, G., Sando, D., Geldsetzer, P., Chalamila, G., & Ekström, A. M. (2017). Job satisfaction and turnover intentions among health care staff providing services for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Human Resources for Health, 15(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-016-0176-x

- National AIDS Council. (2019). Zambia national AIDS spending assessment: HIV and TB spending, 2015-2017 (Issue July). UNAIDS.

- Nguyen, T. A., Oosterhoff, P., Pham, Y. N., Hardon, A., & Wright, P. (2009). Health workers’ views on quality of prevention of mother-to-child transmission and postnatal care for HIV-infected women and their children. Human Resources for Health, 7(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-7-39

- Nsagha, D. S., Bissek, A.-C. Z., Nsagha, S. M., Assob, J.-C. N., Kamga, H.-L. F., Njamnshi, D. M., Njunda, A. L., Obama, M.-T. O., & Njamnshi, A. K. (2012). The burden of orphans and vulnerable children Due to HIV/AIDS in Cameroon. The Open AIDS Journal, 6(1), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874613601206010245

- Onoya, D., Sineke, T., Hendrickson, C., Mokhele, I., Maskew, M., Long, L. C., & Fox, M. (2020). Impact of the test and treat policy on delays in antiretroviral therapy initiation among adult HIV positive patients from six clinics in Johannesburg, South Africa: Results from a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open, 10(3), e030228. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030228

- PEPFAR. (2019). PEPFAR Zambia Country Operational Plan (COP) 2019 Strategic Direction Summary April 12, 2019. https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Zambia_COP19-Strategic-Directional-Summary_public.pdf.

- Prendergast, A. J., Essajee, S., & Penazzato, M. (2015). HIV and the millennium development goals. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 100(Suppl 1), S48–S52. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2013-305548

- Qiao, S., Zhang, Y., Li, X., Menon, J. A., Yotebieng, M.(2018). Facilitators and barriers for HIV-testing in Zambia: A systematic review of multi-level factors. PLoS ONE, 13(2), e0192327–27. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192327

- Southern African Development Community. (2009). The development of harmonized minimum standard for guidance on HIB testing and counselling and prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in the SADC region. Policy, March, 22.

- Tenthani, L., Haas, A. D., Tweya, H., Jahn, A., Van Oosterhout, J. J., Chimbwandira, F., Chirwa, Z., Ng’Ambi, W., Bakali, A., Phiri, S., Myer, L., Valeri, F., Zwahlen, M., Wandeler, G., & Keiser, O. (2014). Retention in care under universal antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected pregnant and breastfeeding women (‘Option B+’) in Malawi. AIDS (London, England), 28(4), 589–598. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000000143

- UNAIDS, UNICEF & World Health Organization. (2011). Global HIV/AIDS response. Epidemic update and health sector progress towards Universal Access. Progress Report 2011, 1–224. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44787

- UNAIDS & WHO (2009). AIDS epidemic update. AIDS (London. England), 37(6), 1287–1296. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/unaids/2007/9789291736218_eng.pdf

- UNEP. (2014). The Emissions Gap Report 2014: A UNEP synthesis Report. ISBN 978-92-9253-062-4.

- Walt, G., & Gilson, L. (1994). Reforming the health sector in developing countries: The central role of policy analysis. Health Policy and Planning, 9(4), 353–370. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/9.4.353

- World Health Organisation. (2013). Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach. WHO Guidelines, June, 272.

- World Health Organization. (2016). Global health sector strategy on HIV 2016-2021. World Health Organization (Issue June 2016). http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/246178/1/WHO-HIV-2016.05-eng.pdf?ua=1%0Afile:///C:/Users/Harrison/Desktop/Consult/Mubaric/A1/WHO-HIV-2016.05-eng.pdf

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2012, April). Programmatic update: Use of antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/mtct/programmatic_update2012/en/

- Wynn, M., & Jones, P. (2019). The sustainable development goals. Routledge.