ABSTRACT

Disability in anglophone media, film and culture is often depicted in ways that rarely recognise people with disabilities as whole human beings. This creates deficit perceptions on what it means to live with a disability. Through the use of photo-voice, fifteen working-class coloured men living with paraplegia in the townships of Cape Town – South Africa, created photo-stories depicting the ways in which they think main-stream society sees them and the ways in which they see themselves. The analysis of their photo-stories was used to contribute to a discourse on photo-voice as activism. The photo-stories raise social awareness on the ways in which disability is socially (mis)understood and (mis)represented in their communities. This work contributes to the development of the affirmative model (Swain & French. 2000 Towards an affirmation model of disability. Disability & Society, 15(4), 569–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590050058189) and the active model of disability (Levitt. Citation2017. Developing a model of disability that focuses on the actions of disabled people. Disability & Society, 32(5), 735–747. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1324764). The thought-provoking photo-stories tell a narrative on reclaiming self-identity and redefining deficit meanings of disability. Ultimately, this work illustrates how powerful and radical the use of photo-voice can be as an epistemological tool for social change, representation and transformation.

Introduction

It is not difference which immobilizes us, but silence. (Lorde Citation2020, p. 16)

Globally, numerous scholars have shown how disability has been depicted in problematic, deprecating and diminishing ways in the media, films and some cultures (see Briant et al., Citation2011; Rice et al., Citation2015; Shakespeare, Citation1994). In films, characters with disabilities are often depicted as humorous, villains, evil and helpless, and their disability is portrayed as a tragedy or a marker of vulnerability (Schwartz et al., Citation2010). The media often uses pejorative language like, ‘the crippled’, which signifies disability as ‘pitiable’ or a ‘burden’ (Briant et al., Citation2011). In some African cultures, disability is understood as evil spirits, witchcraft, punishment or a curse (Bunning et al., Citation2017). In these communities, derogatory labels such as ‘amakroko’Footnote1 are attached to disability. Through these violent, patronising and dehumanising perceptions and representations of disability, flawed social stereotypes and discourses of disability are created. Consequently, playing a crucial and integral role in the way we think about people with disabilities.

The purpose of this work is to dismantle problematic representations of disability among colouredFootnote2 men who live with paraplegiaFootnote3 in townshipsFootnote4 on the periphery of Cape Town, and experience stigmatisation, discrimination and oppression on a daily basis. Subsequently, this work promotes the use of photo-voice method as a tool of activism that contributes to work aimed at re-imagining ways of ‘doing’ research and activism on marginalised bodies. The men in this study were encouraged to photograph the ways in which they think people see them and how they see themselves. Through this, the men challenged prevailing negative discourses of disability and reclaimed their self-identity through signifying: ‘this is how I think they see me, but this is how I want to be seen, accepted, and understood in society’.

Scholars, activists and artists have explored participatory art research methodologies to challenge problematic representations of people with disabilities (see Oliffe & Bottorff, Citation2007; Rice et al., Citation2015). More specifically, researchers have shown the usefulness of photo-voice method in exploring notions of self-representation (see Hunt et al., Citation2020; Kessi, Citation2013; Mji et al., Citation2014). The photo-voice method was developed by Caroline Wang and Mary Ann Burris to document experiences and realities through photographs (Wang & Burris, Citation1997). The photographs are accompanied by a narrative to describe the significance of the photograph. In this way, the participants – who are the experts regarding their own realities, give ‘voice’ to their experiences whilst addressing relevant issues in order to create and mobilise social awareness and change in their communities (Luttrell & Chalfen, Citation2010). Here, activism is defined and driven through the process of directing the shoot, capturing the photograph, giving voice to its significance and disseminating the photo-stories. This enunciation is not only personal, but also political, and powerful.

The power dynamic changes between the researcher and the participant; the participant has control and authority over the camera, images, and stories that they want to tell and how they want their stories to look or be disseminated (Mji et al., Citation2014; Ollerton & Horsfall, Citation2013). In creating, constructing and disseminating their photo-stories, the participants become proactive in advocating for social change. However, most of this advocacy has been centred on the lives of white, western, middle class and physically disabled people (Rice et al., Citation2015), while experiences from the global south, and especially working-class, politically, and culturally marginalised populations in sub-Saharan Africa, are unheard and unseen.

To address the lack of knowledge on self-representation among people with disabilities in the global south, this work centres the voices of coloured men who live with paraplegia in townships in the Western Cape, South Africa. Furthermore, it responds to the ways in which disability has been (mis)represented and (mis)understood by utilising photo-voice to expose and resist stigmatising representations. This act of creating, through dismantling unsettling representations and redefining the self, is a strong political tool because agency is practised in the process of (re)presenting the self-identities of coloured men with paraplegia.

This work draws on and contributes to the understanding of the affirmative model (Swain & French, Citation2000) and the active model of disability (Levitt, Citation2017). The affirmative model of disability is held and developed by people with disabilities about people with disabilities. It not only challenges the notion that disability is a personal tragedy, but it also challenges the determination of the identities that able-bodied people presume of people with disabilities (Swain & French, Citation2000). The model is rooted in exploring the social perceptions of disability and how it impacts the lives of people living with disabilities. Albeit the medical and social model of disability has been used to understand the relationship between disability and impairment (see Shakespeare & Watson, Citation2001), not much attention has been given to seeing people with disabilities as valid individuals with a particular focus on positive social identities, culture, and lifestyle (Swain & French, Citation2000). The affirmative model is significant because it puts people with disabilities on the forefront of validating themselves and elevating their own voices.

The ‘active’ model of disability, developed by Levitt (Citation2017), focuses on how the individual and collective actions of people with disabilities may reduce the restrictions and effects of their disability. This model asserts that people with disabilities can act against misrepresentation, social exclusion or participation, prejudice, oppression and discrimination through actively engaging in individual (e.g. self-help) and collective activities (e.g. support groups or activism) to empower themselves.

This article immerged from my master’s research project in Gender Studies at the University of Cape Town, entitled: ‘Half a man? Still a human: Narratives of coloured men living with paraplegia on the Cape Flats’. In this body of work, I position myself as a queer, able-bodied, coloured male, who continuously battle with discomfort in the disconnect on how society sees me and how I see myself. Navigating the world in an identity that is fluid in gender expression and performance, means that my existence is under constant threat of violence – due to deficit social perceptions of who I am, and ‘how’ I am supposed to embody and hold a hegemonic form of masculinity in certain (or all) spaces. Working as a researcher and scholar, in multidisciplinary fields, particularly that of men and masculinities, and disability studies, offers a space to re-imagine and reinforce different ways of embodying the self, and existing, in a world that does not see marginalised bodies as human enough. In this process of re-imagining, I highlight some of the ways in which bodies with paraplegia do not want to be seen. This form of activism is deeply rooted in amplify marginalised voices and self-representation, consciousness raising, and promoting social justice.

Methodology

This empirical study utilised photo-voice method to create photo-stories on the individual experiences of social and self-representation of disability. This entailed the use of fifteen digital cameras as a tool of expression to capture the ways in which the men in this study think people see them, as well as how they see themselves. The men generated a narrative on the significance of each photograph. Over a period of six months, the men took over the role of the researcher through showing and narrating their own realities and highlighting issues that need a change in their communities.

The study focused on fifteen, working-class, coloured men living with paraplegia in townships on the periphery of the Cape Town metropolitan area. The following inclusion criteria were used to identify and recruit the men: (1) the potential participants had to identify as male, and (2) racially self-identify as coloured, (3) had to be clinically diagnosed with a complete paraplegia, (4) must be 18–60 years old at the time of the interviews and lastly and (5) reside in townships in the Western Cape. The age range was between twenty-seven and fifty years. All men were Afrikaans-speaking. The men were recruited and conveniently sampled from a Non-Governmental Organisation that focuses on improving the physical strength of people with spinal cord injuries and assisting them, in various ways, on their transition from rehabilitation to living in their communities and home. below illustrates additional information on the injury and demographic characteristics of the men in this study, followed by the phases of creating photo-stories.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the male respondents (n = 15).

Phase one: Photo-voice workshop

The photo-story workshop was held at the Non-Governmental Organisation and facilitated by me and a professional photographer. Each of the men were given a digital Canon camera. The role of the professional photographer was to explain how a camera can be used as a tool to convey meaning to objects, people and places, as well as illustrate basic ways to operate the digital camera. The photographer emphasised that the men do not need to produce ‘picture perfect’ images but should know how to use the camera – in daylight and nightlight setting – and how to stabilise an image. Having this voice was important in the space, since it was the first time that many of the men used a digital camera. The men were not hesitant to ask questions; especially on their ability to use the camera with their physical limitations. The photographer responded by sharing ideas on different capturing skills, angles, positions of the body, and ways of holding and positioning the camera. I could not have provided these invaluable skills in my own capacity and limited knowledge on photography. More importantly, the photographer encouraged the men to take ownership and control of the camera, and to remember the authority that they hold in terms of making decisions on how the camera is used, how the shoot is directed and what narrative needs to be told.

Thereafter, I initiated a discussion on visual representation by showing the men images on how some people have photographed themselves and created meaning on self-representation and sexuality. This opened a dialogue about the different ways of seeing and interpreting a photograph. In this moment, the use – and power – of photo-voice became clear to the men. I explained the ethics involved for their protection and those they choose to photograph. I explained that the research proposal had been approved by the internal Institutional Review Board (IRB) in the Department of Gender Studies, at the University of Cape Town. The men completed an informed consent document to participate and have their photo-stories featured in the study, articles and exhibition.

Furthermore, approaches on how to ask others to feature in a photo-story was explored. It was emphasised that it is unethical to photograph others without their consent. The men were given copies of informed consent documents for persons they choose to photograph to grant permission to be photographed, featured in the study, articles and exhibition. The only ethical challenge raised by the men was that they did not always travel with these consent forms in public, and albeit verbal consent was given, these photo-stories could not be featured in the study, exhibition and articles.

The men were given two photo assignments. The first assignment required them to photograph the ways in which they think people see them. The second assignment required them to photograph the ways in which they see themselves – how they would like to be seen, understood and ‘accepted’. In addition, they were asked to write down the significance of each photograph in a notebook. The men were encouraged to be confident in themselves as storytellers about themselves and their realities. After the predetermined period of two weeks, we discussed the photo-stories.

Phase two: Discussion of photo assignments

The photographs were transferred to a laptop and stored in a password protected folder named after each man. Individual in-depth interviews on their photo-stories were held in their homes. The men were asked to select three photographs from each photo assignment that best depicted the message that they wished to convey. They explained the significance of the photographs and how it could contribute to social change. The discussions were approximately 60–90 minutes long and in either Afrikaans or English. The photo-stories were voice recorded, transcribed and translated to English.

Phase three: Analysis and dissemination

Following Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), the photo-stories were thematically analysed to explore experiences and meanings of social and self-representation of disability. The analysis focused on ‘what’ is said (the content) of the photo-story (Riessman, Citation2008). The men participated in the analysis of their photo-stories through selecting the photographs and reviewing the transcriptions of the discussions on their photographs. The following themes emerged across transcripts and were defined accordingly: ‘Objectification and dehumanization’; ‘Rejects: voiceless and incapable men’; ‘Half a man’; and ‘Same as any human’.

With the help and assistance of a professional curator, Daniel Rautenbach, we curated an exhibitionFootnote5 of the photo-stories at the University of Cape Town’s Centre for African Studies Gallery. The exhibition was on for three months. The men selected the photographs and gave creative input on how they want their stories to be exhibited. At the opening evening of the exhibition, a few men spoke about their experiences in creating the stories and what it meant for them to see their stories exhibited in the gallery. The exhibition was a public event and well attended by family and friends of the participants, community members, non-governmental organisations, university students, scholars and activists, policy makers, and advocates for people with disabilities. The intention to build partnerships for community change was met through providing a space for different entities and agents of social change to meet and engage in the photo-stories that highlight pertaining social issues on disability, race, class, and sexuality.

Findings and discussion

The findings presented here reflect and expand current scholarship on disability and masculinity. Although there were many overlapping similarities among the photo-stories, the men in this study only selected the photo-stories that they felt were adequate and powerful in addressing notions of social and self-representation. The men were also clear in that the selected photo-stories are the only stories that they feel comfortable in exhibiting or featured in academic platforms/spaces/articles. The following photo-stories reveal the men’s perceptions of the ways in which they think society sees them. Their photo-stories portray social experiences of disability: of the dehumanisation, discrimination, systematic and social exclusion, oppression and social prejudice labelled against them. Their photo-stories also draw on ableist ideas of ‘disabled’ bodies as the ‘other’.

Objectification and dehumanisation

In his earlier writings on disability and representation, Shakespeare (Citation1994) argued that, culturally, people with disabilities are often perceived as objects rather than humans. Devon’s photo-story below, depicts the ways in which he thinks people see him. Devon’s photo-story alludes to Shakespeare’s (Citation1994) notion of objectification, as he describes how people often stare at him, with facial expressions that normally surfaces when one is surrounded by dirt or in a foul-smelling place. The stares not only make him feel uncomfortable and self-conscious about being in the wheelchair but they also dehumanise his identity and status – as a human being – and equate it with garbage. below depicts Devon’s photo-story.

Figure 1. Garbage. People give me dirty looks, as if I am not worth anything. Have you been to a sewage drain? That is how people pull their noses when they see me. This filthy and foul-smelling place is how I think they see me. Photographed by: Devon.

Similarly, Johan created a poignant photo-story of a broken toilet pot that signifies the glare of disgust when people see him sitting in his wheelchair in public spaces (). This results in feelings of inferiority and social exclusion in his community. His identity, as human, is diminished to this broken object.

Figure 2. Broken toilet pot. They look at me as if I stink like the toilet pot in the picture. See, most people are readable. It is in the way that they look down on me. It makes me feel small and withdrawn. Photographed by: Johan.

In Devon and Johan’s photo-stories, it becomes evident that how they think people see them represents an imagery of objectification, subsequent to the status of ‘the other’ – something not quite human. Moreover, their photo-stories highlight some of the invasive behaviours, like stares and facial expressions of disgust, perpetuated by people in their communities. Both men perceive it as rude, arrogant, and disrespectful. Eisenhauer (Citation2007) argues that stares are an act of violence because it has the potential to turn people with disabilities into an object of curiosity as well as an example of a medical condition – something that needs ‘fixing’. Here, seeing is controlling and denigrating. This creates pain. Devon and Johan often felt saddened and frustrated by this form of invasion, and because they do not want to risk attention, they avert their eyes from those who stare at them. Devon mentioned, ‘I just want to ask them, ‘Is there a problem?’ I do not want to be mean, so I just look away’. Similarly, Kurt also experiences stares from the general public, however, he is of the opinion that people first stare at his wheelchair before they see him. Through his photograph, he argues that the wheelchair, rather than his spinal cord injury, is disabling, because it makes his condition visible and his human identity invisible. shows Kurt’s photo-story illustrating the object that people see.

Figure 3. The disabling chair. The first thing that people see is the wheelchair, which is my disability, they cannot see beyond that. It is like they do not see me at all. Photographed by: Kurt.

In Kurt’s experience, there is a strong relationship between disability and visibility; the visibility of his disability plays a crucial role in what is regarded as a socially acceptable physical appearance. Kurt feels that people completely disregard the fact that he is more than just the wheelchair with a man sitting in it. His wheelchair thus becomes fully representative of his identity; it is imposed upon him, leaving no space for him to articulate his own sense of self. His ‘disabled’ physical body and the wheelchair are viewed as one: a faceless entity. The photo-stories of Devon, Johan, and Kurt reflect similarities in the ways in which they think able-bodied people see them. Part of the purpose of this work is to develop and establish new ways of perception between the public and those with disabilities.

Rejects: Voiceless and incapable men

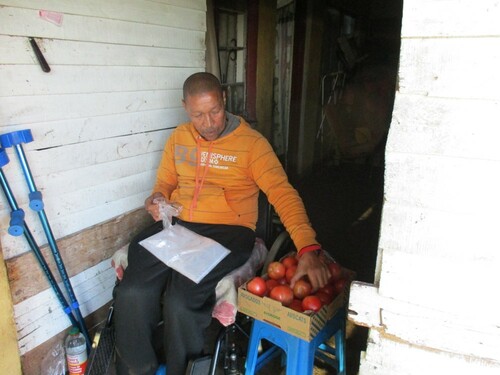

Michael works on a mining site where he acquired a spinal cord injury through rock falls underground. His job entails applying glue to the material on the sockets of knee and arm guards that are used as safety equipment for mine workers. Michael experienced much discrimination in his workplace since the work he performs is the only job assigned to him and other men with paraplegia. This makes him question whether living with paraplegia means that he is perceived as ‘incapable’ of doing any other kind of work in the factory. Decisions in the workplace, which impact him personally, are made for him, signalling a loss of personal agency. Michael photographed the ‘rejects’ container that he sits next to everyday while ‘fixing’ the knee and arm guards that are considered as rejects. The ‘rejects’ container and the work that Michael does, signify the ways in which he thinks people – especially more senior employees – see him.

Figure 4. Reject, patching rejects. People here do not see me as good enough for anything or any other work. I work in a factory, for years, I stitch and glue kneecaps and arm guards. I feel like I am a reject patching rejects because they say that is what I must do. I am only doing this because I need more money to survive. Photographed by: Michael.

The label on the containers constantly reminds him of the diminishing of his identity and dignity to that of a ‘reject’ only capable of ‘patching rejects’. In Michael’s view, the common task among men with paraplegia in the factory strengthens his perceptions of their inability, incapability and irrelevance. Michael’s photo-story puts an emphasis on the need to address exclusion and discrimination in workplaces and in society at large.

In Ridah’s experience, people often think that paraplegia is not his only disability. According to Ridah, people think that the wheelchair represents multiple disabilities. His injury is not a condition that people can see, for example, his legs are not covered in a bandage; there is nothing that tells that he is paralysed. When Ridah is in public spaces, people speak slow and loud to him, as though he has a hearing impairment. Others will talk about him to the people he is with – presuming that he cannot speak for himself. is Ridah’s photo-story challenging the notion of people with disabilities as people with ‘no voice’.

Figure 5. Paraplegic, Deaf, and Voiceless? I will go with family and friends to shops, and often we will bump into people that we have not seen in a while, sometimes even complete strangers. They will speak about me, sometime to each other or to my parents or my sister, in front of me, but not to me. For example, they will ask: ‘How is he doing?’ I am right there in front of them, yet they cannot ask me, they cannot even look at me. But then I answer them, confidently, feeling so annoyed and emotional, ‘I am very well, thank you!’ Photographed by: Ridah.

Ridah’s experience echoes the voices of the respondents in Swartz et al.’s (Citation2018) study, who purport that they have had to work very hard to be seen and participate in activities. Michael and Ridah’s photo-stories highlight the enormous consequences that they, and perhaps other people with disabilities, experience in their lives. For example, visible characteristics, like the wheelchair, may cause people with disabilities to be dismissed from job opportunities or demoted to performing menial tasks that undermine their agency – like the ‘patching of rejects’. The perceptions and misconceptions of disabilities from the society also have a greater impact on the psychological and emotional well-being of those living with disabilities. Michael and Ridah avoid social spaces due to the ways in which they think society sees them. This is disabling.

‘Half a man’

Albert needs assistance in feeding, showering, getting dressed and cleaning after his bowel movements. He sometimes needs to be pushed whilst sitting in the wheelchair. This dependency on others confronts the loss of his independence and makes him think that people often perceive him as a baby ().

Figure 6. Like a baby. This picture took me back to the time when the doctor said to me, ‘Mr, you are now like a baby’. ‘You’ll have to learn to walk again’. It is a terrible feeling of loss in who I thought I was as a man. Some days I do feel like a baby because I cannot do things. It is rather terrible that I am such a big and grown man, but I feel so small. Photographed by: Albert.

In the same way that Albert is constantly confronted with the limitations of his body, Oppies expressed how men in his community would question him on his sexual capacity/incapacity. In his community, he is known as ‘die halwe man’ – ‘half the man’, because half of his body is paralyzed, and he cannot ‘do the things that men do’. In many instances, he felt pressured to prove his worth as a ‘complete’ man by attempting to physically fight with the men who provoked him, but always felt disappointed by his lack of physical strength to do so. This felt humiliating to him.

Moreover, Ostrander (Citation2008) argues that men with disabilities often represent fragility, weakness, vulnerability, and their physical appearance together with the severity of their condition, does not allow them to identify or belong in structures and systems of the hegemonic masculinity that are prevalent in their social context. Oppies acknowledged the importance in creating the photo-story depicted in , as it is one way of using his voice to addresses deficit and hurtful perceptions of him and others with disabilities.

Figure 7. ‘The half-man?’ They will say, ‘look, here comes that half-man’, that is, personal. You cannot say I'm half, I mean how will you feel if someone tells you that you are half? I do not have half a body. I have legs. I am a full man. Photographed by: Oppies.

What becomes evident here is that notions of hegemonic masculinity that are primarily marked through performance, undermine the possibilities and opportunities of men with disabilities, thereby contributing towards the prejudices labelled against people with disabilities. The inability to sustain masculine performances, makes men that fail to embody the hegemonic masculinity vulnerable. In addition, Ostrander (Citation2008) purports that the inability of men with disabilities to perform certain functions, violates social conceptions of what it means to be a man. This appears to be true in the photo-story of Oppies, who is perceived as half a man because he cannot live up to society’s expectations of manliness. This is also reflected in Albert’s photo-story of being perceived as a baby, and in Ridah’s story where the perception is relayed that men living with paraplegia cannot speak for themselves. It is also apparent in Michael’s story where his feelings of rejection are encapsulated in the type of work assigned to him and other men with paraplegia in his workplace. For these men, the physical embodiment of a half-paralyzed body is a true reflection of their experiences of being socially perceived as half a man.

The following photo-stories explore the ways in which the men in the study see themselves. This contributes to the affirmative model of disability (Swain & French, Citation2000), which is primarily rooted in the positive lived experiences of living and embodying a disability. In addition, the photo-stories also reflect the active model of disability (Levitt, Citation2017), which focuses on the ways in which people with disabilities act as agents of change against misrepresentation, oppression, discrimination and social exclusion. Their photo-stories highlight self-defining meanings of ‘disability’ and personhood. Through the process of reflecting on the meanings of each photograph, the men theorised who they are.

‘The same as any human’

Johan understands that society sees him as ‘disabled’, however, he does not self-identify as ‘disabled’. He argued that he does things differently and he often does it even better than able-bodied men. The things that he cannot do, are not significant to his sense of masculinity and self-identity, it is only a bodily limitation that can possibly be ‘fixed’ in due time. He rejects the label of ‘disability’ in constructing his self-identity. His photo-story () elucidates how he sees himself.

Figure 8. The same as other humans. I am the same as any human. I am healthy. I can think. There are many things that I can do, maybe even better than the person who can use his legs. I just happen to sit in a wheelchair. I ride in the wheelchair, and it is as if I am walking. So, it is very hurtful when people say that I am disabled. Photographed by: Johan.

Johan’s photo-story shows how he participates in physical activities with other men, in order to strengthen their muscles and to encourage each other to develop a positive sense of self. This is parallel to the active model of disability as this form of participation and inclusion enhances the self-esteem of people with disabilities, and subsequently, reduces the effects of a disabling society on those with disabilities (Levitt, Citation2017). Paraplegia does not affect his sense of his own worth.

Johan did not relate his participation in physical training to heteronormative and hegemonic constructions of masculinity which emphasises physical exercises for muscle, strength and maintaining a ‘good-looking’ body image. However, the photograph strongly shows what he did not explicitly say – that he is a man, who engages in physical and ‘manly’ activities, as most men do. Moreover, his photo-story is also central to the affirmative model of disability (Swain & French, Citation2000), as he has developed a positive outlook to his identity and does not see himself as the ‘other’ or different to able-bodied men. According to his view, he leads a fulfilling and satisfying life, thereby affirming his identity.

In his photo-story, Michael argues that able-bodied people are responsible for creating barriers and differences that are socially exclusive. This is echoed through the social model of disability (Shakespeare & Watson, Citation2001), which emphasises that society disables people with impairments. For example, being surrounded by other men in a workplace that is designed for people in wheelchairs, gives him the confidence to reject the ‘disabled’ identity category. Michael’s photo-story in corresponds to the development of the affirmative model as Michael and his colleagues were able to construct a collective positive identity amongst themselves; thus, validating themselves and elevating their own voices.

Figure 9. No difference. It is not in my mind to think that I am disabled, because everything that I want to do, I do. So, if your mind is working and your hands is working, you can do many things. Legs are just for going. Photographed by: Michael.

His understanding of himself brings about change in social perspectives on the intersection of disability and labour. Michael ultimately argues that even though he is given a different kind of work – ‘patching rejects’ – there is no difference in his ability and capability to do the work that is assigned to his able-bodied colleagues. The abilities of people with disabilities should not be underestimated.

Oppies wants to be seen and recognised as a human being, first and foremost. He does not see himself as ‘disabled’. He still has all the body parts that make him a whole human being. Even though half his body is paralysed, his mind and most parts of his body functions. This is poignantly expressed in his photo-story ().

Figure 10. Still human. I am still a human being. If you breathe, and then you are still a human. I am still alive. My brain and my mind are still there, I am complete, a whole human being who just cannot walk. I do a lot of things better than the person who can walk because I have a mind and intellectual ability. Photographed by: Oppies.

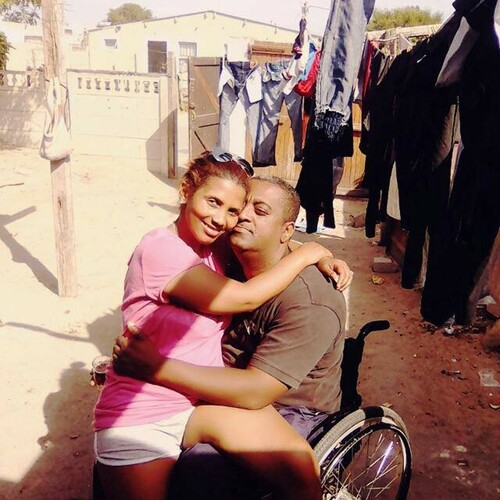

Similar to Oppies, some people in Garth’s community often think of him as asexual. Garth chose to challenge the ideas that people with disabilities have ‘no desire for intimacy and love’ nor are they ‘worth’ experiencing romance. These problematic social perspectives on the intersection of disability and sexuality appears dehumanising and diminishing. In Garth’s trajectory to accepting that his sexual experiences will not be the same as it was for him as an able-bodied man, he often felt emasculated, as he was constantly reminded of his sexual incapacity and inability to perform in penetrative sex – without relying on medication. However, after eight years of living with paraplegia, he found new ways of being and expression.

Garth shows () that there are different ways of experiencing and expressing sexual intimacy, just as there are different understandings of what constitutes as sex.

Figure 11. I am a sexual being. Sometimes just being close to her makes it feel like we are sexually connected. She will sit on my lap and kiss me all over my upper body, she will talk to me in that voice man, you know, that sexy voice. I will also respond to her affection, and in that way, in that moment, we are making love. Photographed by: Garth.

The upper parts of Garth’s body that have sensation become more sensitive, and he associates this sensitivity to that of sex. This is similar to Nick, one of Sakellariou’s (Citation2006, p. 106) informants who said: ‘My nipples are very sensitive to touch. I feel a bit like a woman when this happens’. In Garth’s experience, sexual intimacy and intercourse is more about the closeness, affection, kissing and caressing, that is, shared with his partner rather than penetrative sex. Present here is a symbolism of intimacy that even the physical act of sexual intercourse alone does not necessarily achieve. His understanding and reconceptualising of the sex act have changed through reclaiming his sexuality by engaging in intimacy and sex differently. This is consistent with the findings in Hunt et al. (Citation2018), who found that people with acquired disabilities reclaimed and redefined their sexuality in relation to their disability. For Garth to be an active sexual agent in embracing these new meanings attached to the sex act, represents a re-imagining and reconstruction of fragile masculinity. This signals a ‘coming into being’ of his masculinity.

The notion of ‘doing the same things as I did before the injury, differently’, was strongly portrayed in the photo-stories that the men created on how they see themselves. This is explicit in the photo-story of Allen, who sees himself as ‘differently abled’ as opposed to ‘disabled’. He learned to do the same things that he did prior to his accident in different ways. He challenges the social perceptions that people with physical disabilities are dependent on others and cannot do anything for themselves. His photo-story () is telling of his resistance and determination in achieving his aspirations.

Figure 12. I am differently abled. It just means that you must do it in a different way to achieve it. Now that I am studying at university, my family and friends are proud, but I just feel ‘why are you proud? This is what normal people do. They finish high school, go to university, move out, and things like that’. I think what drives me the most, is that I can carry my own weight. Photographed by: Allen.

Contrary to the other men in this study, Kenneth does not reject the ‘disabled’ identity category. Disability, to him, is a way of being and bodies deteriorating. Thus, he problematises the notion of normality by stating, ‘being normal means that we are all disabled’. In the description of his photograph (), he uses the metaphor of a cracked clay pot, which signifies the human body, and the cracks on the clay pot signifies the brokenness. He, therefore, states that we are all ‘cracked clay pots’ – imperfect. This not only suggests that there is not one impairment that is more disabling than another, but it also puts forward the reality that we are disabled in some way or another – physically, socially, economically.

Figure 13 . All cracked clay pots. We all have our disability. Mine is just more visible than yours. I cannot hide mine. But everyone has a shortcoming. Nobody is perfect. So, it does not make me an exception. There is always something that we are not satisfied with. We are all cracked clay pots. Photographed by: Kenneth.

Kenneth’s photo-story draws attention to the importance of representation and equality. He argues that someone else’s disability might be more hidden, and those who are not disabled will become disabled in their life. Kenneth acknowledges the multiplicity of humanity. Most of the men in this study rejected the ‘disabled’ identity category and see themselves as differently abled men who use their bodies in different ways as they could prior to their injury. Even though they show a great understanding of their self-identities, their construction of self-identity becomes a struggle, because they must constantly challenge the dominant and persistent social representations of who they are.

Conclusion

This study focused on the experiences of representation among fifteen coloured men who live with paraplegia in townships in the Western Cape, South Africa. The men created photo-stories to depict how they think people see them and how they see themselves. The men show self-affirming representations of themselves in ways that signify how they want to be seen, understood and accepted. This speaks to the great determination and agency that those who live with disabilities need in order to claim a legitimate space in the world. The employment of the affirmative model (Swain & French, Citation2000) and the action model of disability (Levitt, Citation2017) has shed much needed insight into the degree of possibility, positivity and active engagement that can exist in the lives of those living with disabilities.

Photo-voice, as a methodological tool, was effective as the photo-stories take the viewer to a reality unknown to them and convey an experience in ways that words alone cannot. In this way, photo-stories present thought-provoking and more explorative narratives than the ethnographic description or in-depth interviews. Photo-voice also allowed the men to become active agents in constructing and conveying social awareness about the (mis)understanding and (mis)conceptions of disability that often marginalise and silence their experiences of living with paraplegia. This type of participation does not only show an awareness that exposes the need for change in the general public’s perceptions of disability, but it also highlights the extent to which the social construction of disability needs to be challenged and taken up as a social justice issue. What emerged from this study is the reality of prejudices, insensitivities and objectification imposed on differently abled bodies which shows society’s unwillingness to humanise disability, as theorised in social models of disability (Shakespeare & Watson, Citation2001), opting rather to engage with a ‘disabled man’ as opposed to a man with a disability.

Activism, in the action model of disability (Levitt, Citation2017), encompasses actions put into play which are enforced by people with disabilities in order to combat exclusion and change society’s attitudes towards them. Photo-voice was a powerful tool in facilitating this kind of activism as the men felt confident enough to leave their homes, participate in sport and create photo-stories in public spaces, which shows how they become actively engaged in reducing constraints imposed on them. Through photo-voice, the men redefined who they are in their multiple roles as men and also as men who live with paraplegia, thereby asserting to themselves and others that they are still human.

This work is not representative of all coloured men living with paraplegia, neither does it represent the realities of those with different disabilities and those from a different demographic background. Albeit this work is rooted in the service of social justice, some voices and realities are unheard. Since insufficient research has been conducted in South Africa on this particular group, this work makes a significant contribution by exploring unique experiences that debunks, challenges and rewrites the stereotypical and seemingly homogenous narratives on paraplegia/disability that currently exist. It may also be said that these men, who are members of a Non-Governmental Organisation, have taken proactive steps towards self-development and creating awareness on the deficit and empowering representations of disability.

Disability is a lived experience that can be told in creative and thought-provoking ways by people who live through disabling experiences. These stories can enable transformative change, not only in the lives of those living with disabilities but also in South African society at large.

Acknowledgements

I will forever be indebted to the men who participated in this study. My appreciation goes to the academic supervisors who guided this project: Dr Rachelle Chadwick, and Dr Gideon Nomdo. Thank you to my teachers who provided insightful feedback on this work: Dr Athena-Maria Enderstein, Dr Lorraine Nencel, Dr Phoebe Kisubi, Dr Frederik Behre, and Sian Halas. I would like to express my gratitude to Daniel Rautenbach who curated the exhibition with me, and Liese Kuhn for her expertise in photography. Thank you to the Department of Art and Culture who funded the exhibition. To the reviewers and editors of this special issue, I appreciate the constructive feedback that elevated the sound of this work. This research study received ethical approval from the African Gender Institute and Department of Gender Studies review board (IRB) at the University of Cape Town (UCT). All participants grated informed consent for the photo-stories to be published.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Translated as ‘the broken one’ and is a nickname for the South African paraplegic team.

2 The coloured racial identity refers to people of mixed racial origins who were not White enough to be classified as White and neither Black enough to be classified as Blacks (Adhikari, Citation2005).

3 An acute, traumatic lesion of the neural elements of the spinal cord that results in temporary or permanent loss of sensation and motor deficit that causes paralysis from the waist of the body downwards (Sakellariou, Citation2006).

4 During apartheid, coloured people were forcibly removed from areas in Cape Town by the Group Areas Act. This act restricted coloured and black people to townships on the Cape Flats.

5 Follow the link to view a short video of the exhibition: https://vimeo.com/288057032.

References

- Adhikari, Mohamed. (2005). Not white enough, not black enough: Racial identity in the South African coloured community. Ohio University Press.

- Braun, Virginia, & Clarke, Victoria. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Briant, Emma, Watson, Nick, & Philo, Greg. (2011). Bad news for disabled people: How the newspapers are reporting disability. Project Report. Strathclyde Centre for Disability Research and Glasgow Media Unit, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK.

- Bunning, Karen, Gona, Joseph K., Newton, Charles R., & Hartley, Sally. (2017). The perception of disability by community groups: Stories of local understanding, beliefs and challenges in a rural part of Kenya. PLoS One, 12(8), e0182214. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182214

- Eisenhauer, Jennifer. (2007). Just looking and staring back: Challenging ableism through disability performance art. Studies in Art Education, 49(1), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00393541.2007.11518721

- Hunt, Xanthe, Braathen, Stine H., Swartz, Leslie, Carew, Mark T., & Rohleder, Poul. (2018). Intimacy, intercourse and adjustments: Experiences of sexual life of a group of people with physical disabilities in South Africa. Journal of Health Psychology, 23(2), 289–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317741761

- Kessi, Shose. (2013). Re-politicizing race in community development: Using postcolonial psychology and photovoice methods for social change. Psychology in Society, 45, 19–35.

- Levitt, Jonathan M. (2017). Developing a model of disability that focuses on the actions of disabled people. Disability & Society, 32(5), 735–747. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1324764

- Lorde, Audre. (2020). The cancer journals. Penguin Classics.

- Luttrell, Wendy, & Chalfen, Richard. (2010). Lifting up voices of participatory visual research. Visual Studies, 25(3), 197–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2010.523270

- Mji, Gubela, Schneider, Marguerite, Vergunst, Richard, & Swartz, Leslie. (2014). On the ethics of being photographed in research in rural South Africa: Views of people with disabilities. Disability & Society, 29(5), 714–723. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2013.844103

- Oliffe, John L., & Bottorff, Joan L. (2007). Further than the eye can see? Photo elicitation and research with men. Qualitative Health Research, 17(6), 850–858. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732306298756

- Ollerton, Janice, & Horsfall, Debbie. (2013). Rights to research: Utilising the convention on the rights of persons with disabilities as an inclusive participatory action research tool. Disability & Society, 28(5), 616–630. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.717881

- Ostrander, R. Noam. (2008). When identities collide: Masculinity, disability and race. Disability & Society, 23(6), 585–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590802328451

- Rice, Carla, Chandler, Eliza, Harrison, Elisabeth, Liddiard, Kirsty, & Ferrari, Manuela. (2015). Project revision: Disability at the edges of representation. Disability & Society, 30(4), 513–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2015.1037950

- Riessman, Catherine K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage.

- Sakellariou, Dikaios. (2006). If not the disability, then what? Barriers to reclaiming sexuality following spinal cord injury. Sexuality and Disability, 24(2), 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-006-9008-6

- Schwartz, Diane, Blue, Elfreda, McDonald, Mary, Giuliani, George, Weber, Genevieve, Seirup, Holly, Rose, Sage, Elkis-Albuhoff, Deborah, Rosenfeld, Jeffrey, & Perkins, Andrea. (2010). Dispelling stereotypes: Promoting disability equality through film. Disability & Society, 25(7), 841–848. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2010.520898

- Shakespeare, Tom. (1994). Cultural representation of disabled people: Dustbins for disavowal? Disability & Society, 9(3), 283–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599466780341

- Shakespeare, Tom, & Watson, Nicholas. (2001). The social model of disability: An outdated ideology? In S. N. Barnartt, & B. M. Altman (Eds.), Exploring theories and expanding methodologies: Where we are and where we need to go (pp. 9–28). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Swain, John, & French, Sally. (2000). Towards an affirmation model of disability. Disability & Society, 15(4), 569–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590050058189

- Swartz, Leslie, Bantjes, Jason, Knight, Bradley, Wilmot, Grey, & Derman, Wayne. (2018). “They don’t understand that we also exist”: South African participants in competitive disability sport and the politics of identity. Disability and Rehabilitation, 40(1), 35–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2016.1242171

- Wang, Caroline, & Burris, Mary A. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24(3), 369–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019819702400309