ABSTRACT

Due to barriers in accessing and using healthcare services, a large proportion of the care homeless populations receive comes from informal providers. In Delhi, one such informal programme, called Street Medicine, provides healthcare outreach to homeless communities. Clinical practice guidelines are set to be developed for Street Medicine teams in India and form the object of this research. This study uses a social-ecological model to understand the barriers facing Street Medicine teams and the homeless as they attempt to address the latter’s healthcare needs; coupling it with an analytical approach which situates these barriers as the issues within practice through which standardisation can take place. A qualitative inquiry, comprising three months of observations of Street Medicine outreach and interviews with over 30 key informants, was conducted between April and July 2018. The analysis identified novel barriers to addressing the needs of homeless individuals, which bely a deficit between the design of health and social care systems and the agency homeless individuals possess within this system to influence their health outcomes. These barriers – which include user-dependent technological inscriptions, collaborating with untargeted providers and the distinct health needs of homeless individuals – are the entry points for standardising, or opening up, Street Medicine practices .

Introduction

Accessing and receiving joined-up healthcare services is a major challenge for homeless populations. While measurements of homeless persons’ unmet healthcare needs in countries of the global North (Argintaru et al., Citation2013; Baggett et al., Citation2010; Canavan et al., Citation2012; Fazel et al., Citation2014) are missing for the global South, research on the barriers to accessing healthcare in a few Southern countries, such as India (HIGH, Citation2003; Mander, Citation2008; Prasad, Citation2011) and Brazil (Borysow & Furtado, Citation2014; Oliveira et al., Citation2021), evidence homeless populations face similar constraints across both regions. Homeless individuals’ lower engagement in services compromises treatment efficacy, increasing the likelihood of premature mortality for homeless persons (Beijer et al., Citation2011; Morrison, Citation2009), while also being more likely to use higher cost, acute and emergency care services, with longer duration of stays (Hwang et al., Citation2011, Citation2013). There are, as yet, few treatment and care models for the homeless which establish a true continuum of care, within and across formal and informal providers.

The approaches to understanding homelessness and the issues they face in addressing health needs vary. Schools of research and practice can be categorised by either their focus on individual (Calsyn & Roades, Citation1994; Rae & Rees, Citation2015) or structural (Burt, Citation2001; Lowe et al., Citation2017) determinants of homelessness, with a shift from former to latter as explanations of individual culpability broadened to implicate the state (Kennett & Marsh, Citation1999; Neale, Citation1997; Speak, Citation2013). The third group of integrative models for homelessness has attempted to bridge the divide created by positioning the causes of homelessness as dichotomous (Haber & Toro, Citation2004; Levy, Citation1998; Nooe & Patterson, Citation2010; Speak, Citation2013). These models share an ecological focus on the interactions between individuals and their social context, which is often split across levels or domains, ranging from an individual’s immediate environment to the wider policy context. This perspective seeks to avoid the reductionism of earlier explanations given it ‘does not advance an etiological understanding of homelessness reflective of the phenomenon’s actual complexity nor does it foster robust, multi-systemic response options from communities, agencies, organizations, and practitioners’ (Nooe & Patterson, Citation2010, p. 106). The influence of context on one’s behaviour or needs is no more apparent than for homeless individuals; the aforementioned impact of shelter, or lack thereof, on health serving as a centre point from which a network of numerous health determinants branch off (Commission on Social Determinants of Health, Citation2008). The criticism of social-ecological models, however, is that while giving an exhaustive description of the relationship between individuals and their environment, they do not help discern which relationships are most important for intervening.

Aside from housing homeless individuals – which has been associated with an improved ability to seek non-urgent care (Kushel, Citation2001; O’Toole et al., Citation1999) – there are few comprehensive, national strategies for their healthcare provision. One group of affiliated programmes seeking to fill this gap is united under the name ‘Street Medicine’, which now has researchers and health practitioners working on homeless outreach and service provision in 85 cities and across 15 countries (Street Medicine Institute, Citation2018; Van Laere & Withers, Citation2008). These informal providers now work towards developing a model of care which accounts for the broad and complex social determinants of health for the homeless. The task is thus translating theoretical understandings of homelessness into actionable programmes and policies.

Medical protocols are set to be developed for Street Medicine teams in India and form the object of this research. The adoption of a universal guideline appears at odds with approaches informed by social-ecological understandings of homeless, which are particularly sensitive to the influence of contexts on behaviour. This study uses the social-ecological model to understand the barriers facing Street Medicine teams and the homeless as they attempt to address the latter’s healthcare needs, yet marries it with an analytical approach which situates these barriers as the issues within practice through which standardisation can take place. This ‘situated standardisation’ (Zuiderent-Jerak, Citation2015) reconfigures the numerous influences elucidated by the social-ecological model to local problems in Street Medicine practice, identifying points of entry for adapting and standardising practices. The research aim thus becomes to unpack these barriers to addressing homeless health needs as sites of contestation for the standardisation of Street Medicine practice. The application of this approach to the current case is discussed in more detail in the following section.

Methods

Approach and theory

The study was conducted in collaboration with the Centre of Equity Studies (CES) in Delhi and began as two separate inquiries on understanding barriers to: (i) the utilisation of formal healthcare facilities or services (i.e. any healthcare facility whose services are reimbursed by government or paid through a prepayment system, such as private insurance) by homeless individuals; and (ii) the provision of Street Medicine to homeless groups. These inquiries form the basis of the analysis into barriers as entry points for standardisation.

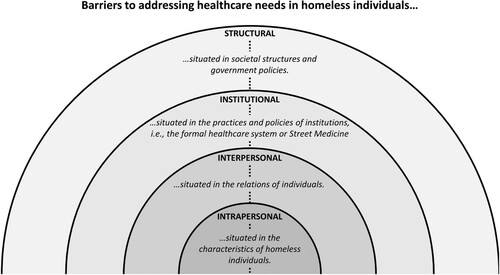

Academic and institutional research conducted in the U.K. has established that homeless vulnerability is the product of both individual factors, and synergistic effects of intersecting factors at multiple levels (Bramley et al., Citation2015; Clinks et al., Citation2009; Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2011). Street Medicine teams wish to design guidelines that avoid singular perspectives of homeless vulnerability: designing solutions with the health system view in mind leads to solutions that aim to overcome the ‘personal deficiencies’ of homeless individuals, such as a lack of citizenship, knowledge or resources. Conversely, designing solutions as the result of health system failures denies the intervention the crucial ingredient in addressing the health need, i.e. the individual. This study uses a social-ecological understanding of homelessness to understand the perceived barriers to addressing homeless health needs across levels of influence, from the proximal (i.e. within an individual’s sphere of influence) to the distal (i.e. only distantly influenced by an individual). The framework characterises levels of influence, or barriers, that are grouped as: the intrapersonal, i.e. characteristics of homeless individuals affecting behaviour, such as demographics or personal choice; the interpersonal, i.e. features of the relations between homeless individuals, or homeless individuals and healthcare providers, such as patient-provider trust or peer pressure; the institutional, i.e. the practices and policies of the healthcare provider (formal providers or Street Medicine teams), such as resourcing problems or institutional norms, and; the structural, i.e. the societal structures and government policy that affect behaviour, such as structural discrimination or political priorities ().

Figure 1. The influences on barriers to addressing homeless healthcare needs across ecological levels.

In Street Medicine, the best, evidence-based practices recommended in clinical guidelines can quickly become unworkable in the ever-changing, ‘on-the-street’ process of care delivery and its management, which is limited by time and resources. Even common features of clinical practice, such as follow-up or medicine dispensation, can be impeded by a lack of a fixed address and storage. This problem ties to common pitfalls in standardisation debates: (i) the ‘gap’ of adherence by clinicians to clinical practice guidelines (Ament et al., Citation2015); and (ii) the implied trade-off between a universal guideline applied to all patients and the growing agenda for personalised medicine (Epstein, Citation2008). Foregrounding the influence of disparate factors on behaviour, as social-ecological models are used, can see their holistic and nuanced understandings as inconsistent with the aim of developing universalised interventions in guidelines. The approach of this study is informed by sociological interventionist research into standardisation of healthcare practices and aims to overcome these pitfalls by, rather than standardising on the level of categorical group, standardising on the ‘specific issues patient groups face because they have to make use of the same resource’ (Zuiderent-Jerak, Citation2015, p. 80). In addition, this study does not seek to identify barriers with the health system design in mind or those that assume some health agency on the part of the patient, but those grounded in Street Medicine practice. The barrier is no longer understood as what must be overcome for ‘better’ Street Medicine practice, but the tool through which to examine competing ideas about the best way of standardising Street Medicine practice and addressing homeless healthcare needs. This ‘situated’ standardisation ‘tries to empirically elucidate specific issues in care delivery so that an assessment can be made of which aspects of the organization of care should be given space and which aspects should be standardized’ (Zuiderent-Jerak, Citation2015, p. 72). The analysis describes barriers as these issues in care delivery that obstruct meeting homeless healthcare needs for the actors implicated in the problem (Street Medicine, the homeless and formal healthcare providers).

Healthcare provision for the homeless in Delhi

Estimates of the size of the homeless population in Delhi vary, with counts from the 2011 Census at 47,000 for the National Capital Territory of Delhi (ORGI, Citation2011), and surveys by different organisations ranging from estimates over 150,000 (Indo-Global Social Service Society, Citation2012) to 324,375 (Supreme Court Commissioner’s Office, Citation2011). In theory, below-poverty line (BPL) individuals receive fully subsidised health insurance coverage through the publicly funded National Health Protection Scheme. Launched in 2018 and nicknamed ‘Modicare’, it covers hospital treatments in secondary and tertiary facilities up to INR₹ 500,000 (USD$ 6575) per year for a family of five (Press Information Bureau, Citation2018). Availing these services, however, is contingent on overcoming resourcing shortfalls and governance issues that plagued the scheme’s previous incarnation and stopped its widespread use (Angell et al., Citation2019; Sharma, Citation2018). The Street Medicine teams in Delhi, managed by CES, are one informal provider of healthcare in the city attempting to plug these shortfalls. CES deploys two Street Medicine teams that, per week, each cover eight different routes or locations where homeless groups congregate. Each team consists of one doctor, one nurse or auxiliary-nurse-midwife, one social worker and one driver-cum-social worker.

Research activities

Both inquiries comprised of observations and semi-structured, key informant interviews that took place between April and July 2018. The study design was part of a proposal to the external ethics committee of the Banyan Academic of Leadership in Mental Health (BALM), Chennai, India, which was approved in July 2018. Over these months, the second and third authors conducted field observations with Street Medicine teams during their schedule of outreach visits to 20 locations that repeats every two weeks; visiting each location at least once. Field notes documenting these observations were made later the same evening.

Each researcher was responsible for a single inquiry, either focusing on barriers to healthcare utilisation for the homeless or the barriers to providing Street Medicine for the homeless. Each researcher conducted a series of interviews, using their observations to inform a purposive selection of stakeholders. The former inquiry comprised: six interviews with formal healthcare providers and researchers, five interviews with Street Medicine personnel, and six shortened and less structured interviews with homeless individuals; using Andersen, Davidson and Baumeister’s behaviour model of healthcare utilisation to operationalise the barriers concept (Andersen et al., Citation2013). The latter inquiry included interviews with fourteen members of the Street Medicine team, adapting Mrazek and Haggerty’s intervention spectrum (Citation1994) to identify barriers at each stage of a standard Street Medicine consultation and care pathway. Both sets of interviews were conducted with a Hindi translator when necessary.

Field notes and interviews were transcribed and analysed by each researcher. The coding strategy was first inductive, iterating towards concepts related to utilisation or provision barriers. Although identified separately, the barriers to using healthcare for the homeless were then matched to barriers in the provision of Street Medicine where the phenomenon described was the same or related. In this way, the phenomenon was repositioned as a barrier to addressing the healthcare needs of the homeless, and these barriers were finally categorised across the social-ecological levels. During this final stage, the first three authors worked to integrate the separate analyses.

Findings

The barriers described are not seen as obstructions to improving Street Medicine practice but defined as areas of contestation where the adaptation of practices (either standardised or not) can be discussed. In identifying these barriers, respondents also characterised their ‘desired’ utilisation behaviours or Street Medicine practices, by virtue of what was occluded by the barrier they described. Based on this, barriers to using healthcare services for homeless individuals could be classified by whether they imply (i) timely health need identification, (ii) access and treatment based on need, or (iii) both. On the other side, the ‘desired’ Street Medicine practices obstructed by barriers could be categorised as: (i) prioritising the right areas and patients to target; (ii) balancing their mobility and diagnostic/therapeutic capacity; (iii) providing timely healthcare services to all those in need; (iv) coordinated case management including referrals, emergencies, social care and outreach; and (v) facilitating long-term change for homeless groups. These ‘desired’ behaviours are reflected upon further in the discussion as they reveal what aims must be reconciled in the design of interventions and their standardisation. The barriers described here are split across the ecological levels of influence specified above.

Intrapersonal barriers

Homeless individuals’ devalued need for care was mentioned by both homeless respondents and health professionals, affecting the timely identification of health needs and healthcare provision. This devalued need derives from the self-assessment of health status, functioning and symptoms, which in turn is a product of health beliefs and personal characteristics. A 17-year-old homeless female described discovering she was pregnant after visiting a hospital for the first time, five months into her term:

Yes, I have been [to a hospital]. I had pain in my stomach. And I was pregnant. Maybe something was wrong with the child, so I went. Now I know the child's head is not growing properly.

The identification of health needs was also delayed by homeless individuals’ competing priorities, where food and shelter were the first concern before acting on health needs. The health counsellor at the homeless shelter highlighted their precarious income streams, most evidently for daily wage labourers, where a single day of work missed precludes buying food or other necessities. For Street Medicine, identifying the people and places to work is made complex by the homeless’ subsistence reality, and the stringent prioritisation of needs based on survival. As employment outweighs health needs, reliably finding the same groups or individuals to treat across multiple visits can be impossible. Similarly, the treatment regimens can be discontinued once initial benefits in health status are observed, as described by one of the Street Medicine doctors:

So, after two or three months, things start improving. And then once again he starts to think that now he is okay and stops taking the medicine or leaves [the shelter].

Finally, health professionals raised homeless’ limited health agency that affects their identification of care needs, access to treatment and Street Medicine’s case management. The contrasting conceptions of this agency, which could be seen as a hindrance or distinct quality, were considered by a public health researcher at the George Institute:

I don’t think you need to be highly literate to seek care. […] I think the way in which the homeless people operate through their networks, it’s an exercise of their own agency to increase their own literacy. […] I think that more than the system itself reaching out it’s very much the formal and informal networks that homeless have themselves that guide these decisions.

For me advice is not enough. You need to tell them where the safe water is, where the tap water is and if they can get to it. Where is the toilet, [where] there is no toilet!

Interpersonal

The interpersonal relationships between homeless individuals and with the Street Medicine teams affected their utilisation in the form of timely health-seeking and treatment access, and Street Medicine’s healthcare provision in their attempts at case management. At the behest of hospitals, access to treatment can be denied or complicated without a next of kin or guardian, entangling the many homeless individuals living alone in a bureaucratic mess when trying to address their health needs. For Street Medicine, their patients’ deep-rooted distrust towards authority, and the public health system, often caused them to refuse hospital referrals from the team, even in emergency situations. This lack of trust could also make sharing patient information difficult or unreliable and feed into healthcare-seeking delays which cause Street Medicine teams to diagnose at later stages of illness or injury. Aside from building trust with homeless communities themselves, the Street Medicine teams also tried to smooth relations between homeless individuals and formal care providers, such as when designating a specific team member (a so-called ‘referral manager’) to accompany homeless individuals needing specialised care to formal healthcare facilities. Finally, the effect of homeless’ interpersonal relationships could manifest as a limiting health-seeking environment in the norms and practices of their social relations. For example, entire communities of substance users resided in specific areas, and thus individuals’ balance of risk-taking to health-seeking could be influenced by others in their environment.

Institutional

A number of barriers to addressing the health needs of the homeless stem from the institutional conflict that arises between Street Medicine and formal healthcare providers. The attempted management of cases by Street Medicine teams leads them to collaborate with other healthcare providers and authorities, who are all untargeted to homeless individuals unlike themselves. In certain cases, the prejudices of healthcare providers or authorities towards homeless individuals can hinder this collaboration. Referral can be delayed as police and ambulance staff were described to take a long time to arrive in emergency situations, with teams having to bargain with, beg and bribe the police to take patients to the hospital. Even when patients are transferred to the police, interviewees explained they may likely be dropped off around the corner. This behaviour, in part, derives from a fear of becoming the responsible party for that homeless individual, in the absence of their own family ties or identification. Further, the extensive and time-consuming bureaucracy of the Indian health system requires the Street Medicine referral manager on hand to help the homeless navigate their treatment.

For the homeless seeking care, they confront a system that is poorly targeted towards their needs. Both homeless individuals and Street Medicine professionals described ‘inscriptions’ of healthcare technologies on users of the formal healthcare system. These inscriptions are parts of a technology – broadly defined, such as a care pathway – that is contingent on the involvement or some capacity of the end-user (the patient). For example, a 17-year-old homeless female described being denied care due to not having her medical history on her person. As the hospitals in Delhi require patients to manage their own medical records, the technology fails to work for homeless individuals with little or no storage. Combined with this, and perhaps as a result of this misalignment, are negative perceptions toward the homeless, described by Street Medicine team members and other respondents, at both the institutional and structural levels. This lack of respect from formal healthcare givers was suggested – by the public health researcher at the George Institute – to drive homeless groups to rely on their network for health needs or choice of providers:

Where they are getting care [doesn’t matter], as long as it is with respect […] What ends up happening, because of the lack of connect [with healthcare providers], they rely very much on their own network.

The barriers to Street Medicine’s care when collaborating with formal providers, of which the user-based technological inscriptions form a part, stem from the lack of standardised care practices and pathways for homeless individuals in their own practice and the health system at large. Street Medicine confronts this for recording patient information, triage and prioritising cases, diagnosis, managing long-term care patients and follow-up, which makes the care received vary depending on the team member. While on the health system’s side, a physician at Safdarjung Hospital described the lack of institutional norms and standards for homeless patients who died at the hospital, leaving the health system fearing the responsibility of coordinating their end-of-life arrangements. Similarly, this barrier is also impacted by the broader curative orientation of the health system, determined by policy, which makes the narrow scope of the Indian health system insufficient for the more holistic needs of homeless individuals.

Contributing to Street Medicine’s coordination problems is the lack of a digital and remote-access system for managing patient information, which would harmonise terminology and facilitate follow-up. Means to verify and incentivise adherence, as well as other systems for effective follow-up or tracking would greatly assist Street Medicine’s case management and their scope for effecting long-term change in homeless communities. The inability to facilitate longer term changes, by joining up care for the homeless, was a source of grief and frustration for many Street Medicine team members.

Finally, one of the barriers most frequently mentioned by Street Medicine members was their mobility/resource constraints which can limit their diagnostic and therapeutic capacity. A key constraint is the lack of female care-givers, which makes some examinations impossible and could deter health-seeking from homeless women. Yet, for both men and women, certain examinations, particularly genital, are virtually impossible given diagnoses happen on the street. The limited capacity to specify the aetiology of symptoms was described the Street Medicine nurse:

It’s like a temporary diagnosis. Most of them are temporary. But there are also cases where I also don’t know what the real cause is. For example, fungal infections. You also have ringworms. When you have both it’s hard to know which is the cause and if we are treating the right thing.

Structural

There was a clear connection between the barriers described at the institutional level and their antecedents at the structural level linked to policy. The aforementioned difficulties of collaborating with authority also have connections to wider societal perceptions of homeless individuals – Street Medicine teams described having to ‘clean up’ patients before taking them to hospital – and the lack of trust this engenders within homeless communities. Negative societal perceptions of the homeless were described, which feed into the healthcare they receive, while the wider design of the health system assumes user capacities and involvement. This assumption of health agency on the part of the patient creates difficulties for homeless individuals when required to keep medical records, store medications or attend other outpatient services on different days. Given the health system’s design is centred on curative healthcare, it acts as its own barrier to health-seeking for the homeless. This combines with Street Medicine’s general lack of health promotion or preventive therapies for a distinct population like the homeless, i.e. one that can account for their lack of health agency.

The limits of the health system’s design for homeless individuals are also derivative of broader policy norms and prescriptions, evidenced in the lack of bureaucratic standards for those without citizenship or address. As with homeless individuals who die in hospital, access to healthcare is more difficult for those without proof of citizenship. The ability to target therapies for the homeless, within and outside Street Medicine, also derives from deeper issues in the supply of relevant healthcare services, particularly primary care within urban areas. Without accessible primary care or addiction clinics and mental healthcare services, the continuum of care Street Medicine attempt to provide can be cut short. Finally, the culturally-bound understandings of medicine can affect health-seeking and treatment compliance. Team members described the difficulty of diagnosing STDs given its stigma and the scepticism shown towards certain therapies, increasing non-adherence.

The aforementioned social isolation of homeless individuals was also attributed by health professionals to the geographic isolation of some homeless communities to society’s margins, where spatial access to health and other public facilities is harder. Street Medicine teams have to contend with the internal displacement of homeless communities enforced by local government authorities, alongside ongoing ‘beautification’ that seals off increasing amounts of public space, such as large traffic islands or under motorways, and pushes them onto roads or other exposed areas. These marginalised communities can become harsh social environments, which, in some cases, are associated with high rates of drug use, theft and abuse, constraining the health-seeking agency of its members.

Aside from mirroring barriers at other levels, there were also barriers discretely situated at the structural level. A physician at AIIMS described the cultural norms surrounding gender and their effect on homeless individuals’ access to treatment:

A patient: a female child, but you have brothers at home who are normal, healthy. So, they will not bring you to the hospital. Because that’s like investing their time. Until she becomes the age of marriage, then they’ll panic and go.

Discussion

The aim of this research was to unpack barriers as the sites of contestation for adapting Street Medicine practices. First, the majority of barriers described here, primarily to healthcare utilisation, are repeated in earlier research. Although mostly conducted in global North countries, these barriers include their exclusion from citizenship and forms of identification for receipt of public entitlements (Crisis, Citation2002; Mander, Citation2008; Rae & Rees, Citation2015), the bureaucracy of healthcare access (Wise & Phillips, Citation2013), the deterring attitudes of providers and public officials (Rae & Rees, Citation2015), the homeless’ competing priorities (Gelberg et al., Citation1997; Kushel et al., Citation2006), and their limited spatial access to providers (Gelberg et al., Citation2004; Vuillermoz et al., Citation2017).

By grounding the problems in Street Medicine practice, however, a number of novel barriers were described which are points of entry for standardisation, given that they are conceptualised from the vantage of Street Medicine’s practice. For example, late-stage health need identification can also be traced back to poor past healthcare experiences, yet conceptualising the barrier as the latter would be impossible for Street Medicine teams to change. These barriers include user-dependent technological inscriptions, collaborating with untargeted providers and the distinct health needs of homeless individuals. Each of these barriers highlights a gap that could be filled by a (informal) healthcare provider, contrary to attributing the barrier to a personal deficiency. The application of this approach within the practice of an informal care provider to the homeless reveals issues that bely a deficit between the design of health and social care systems and the agency homeless individuals possess within this system to influence their health outcomes. The interventions taken by Street Medicine to give back this agency or bridge these capacity gaps are instructive for other informal providers acting as intermediaries between healthcare providers and vulnerable populations marginalised from these services.

As they attempt to address their health needs, the issues the homeless face can be viewed as endeavours to maintain agency while doing so, and this yields potential opportunities for changing standard care practices in Street Medicine. An example of an agency-based care standard comes from current Street Medicine practice in Delhi, where they have developed ‘referral managers’: on-call personnel for the Street Medicine teams, who accompany homeless individuals to hospitals if they need more specialised care. These referral managers assist in navigating both the physical layout and bureaucracy of the hospital. In this case, health agency is conferred ‘by proxy’ from the referral manager to the homeless individual, and bridges the gap between the misaligned needs of homeless individuals and the health system’s design. While this would be an example of a ‘procedural standard’, as defined by Timmermans and Berg, which ‘delineate a number of steps to be taken when specified conditions are met’ (Timmermans & Berg, Citation2003, p. 25 ), other standards – such as design standards, performance standards and terminological standards – are possible. Equally, the practices to be standardised are not just those in the business of ‘providing healthcare’ but also the administrative, bureaucratic or political organisation of those services. The remainder of this section outlines other issues in Street Medicine which are entry points for standardising, or opening up, practices.

A key issue in delivering the most effective care to homeless individuals was the confusion surrounding certain roles’ responsibilities. There needs to be a clear delineation in how responsibilities are divided or shared across Street Medicine’s healthcare professionals, coordinators, and auxiliary staff to reduce ‘task uncertainty’. Research into medical problem-solving suggests categorising tasks as high vs low task uncertainty (i.e. based on the knowledge required to perform a task), as they require different organisational structures to execute them (Holmberg, Citation2006). High task uncertainty decisions lend themselves to the thematic groupings of activities around the decision-making process, the greater distribution of tasks (i.e. referrals) through the organisation, the decreased formalisation of activities (i.e. in standards) and more nuanced forms of evaluation that consider norms and values. Thus, for Street Medicine, this starts with cataloguing all tasks performed by members of the team and ends with design standards, which would be detailed job descriptions in this case. Without a clear of assignment of tasks to individuals, many individuals end up performing the same task and doing so differently; their execution being influenced by the information available to them and personal values, a form of discretion that corresponds to ‘street-level bureaucracy’ (Lipsky, Citation1980). One example of this is in the prioritisation of cases: is priority given on a discretionary basis by healthcare professionals when conducting outreach or on the basis of directions from coordinators? This is a case where task uncertainty could be reduced by standardisation, both in the assignment of the task (i.e. in a design standard) and in its execution (i.e. in a procedural standard). In seeking to strike the ‘right’ balance between addressing a high number of (coverage), and high needs (severity), cases, prioritisation lends to a deliberative process that is compatible with Street Medicine’s coordinator role, rather than an ad-hoc decision for care-givers. For these coordinators, standardising the process of prioritisation entails using the information available to them, on high needs cases and areas of high numbers of homeless individuals, to create criteria that reconcile Street Medicine’s aims for coverage vs severity.

Another set of problems confront Street Medicine teams as, in the process of giving care, they are attempting to reconcile the delivery of their medical therapies with homeless individual’s contextual reality. Given the limited agency the homeless possess to make decisions about and affect their own health – in finances, time, dietary choice, citizenship, spatial access – all therapies provided must be cognisant of this contextual reality, which starts by understanding the communities in which they reside. This issue defines standardising Street Medicine practice, as mapping capacities of homeless communities provides the ‘inputs’ to begin targeting interventions and practices toward the causes of ill health among the homeless. Additionally, part of this mapping would be to understand homeless communities’ capacity to contribute to the care and other services they receive through Street Medicine. CES’ already does this, for example in the identification of individuals for Aadhar registration, yet this could be expanded based on the primacy of the homeless’ networks in guiding care decisions, as suggested by this research and previous (Hwang et al., Citation2009; Meeks & Murrell, Citation1994; Reitzes et al., Citation2011). Understanding these networks, and the advice and help they distribute, could be key to shifting the health-seeking and decision-making of an aggregate population, rather than individuals. This engagement can become a standard part of Street Medicine practice, yet must necessarily remain flexible to the different levels of buy in from homeless communities. Thus, homeless communities could be mapped using a standardised assessment (e.g. questionnaire), but certain actions, such as enlisting community members in Street Medicine activities, could remain on a case-by-case basis.

In Brazil, Borysow and Furtado (Citation2014) describe similar obstacles to uptake and care continuity for homeless populations – in their study, with severe mental illness – due to the conflict between the unique and competing needs of homeless individuals and the design of public services: whether health services, social assistance or public safety. Interruptions and abandonment of treatment by homeless persons can also occur when care pathways rely on referrals or coordination between targeted (e.g. Street Medicine) and untargeted (e.g. public hospital) providers; and, as Borysow and Furtado describe, the ‘antagonisms between the paradigms of the involved sectors’ (Citation2014, p. 1071). As such, they advise designing interventions between the sectors involved, in order to create a ‘common’ object for intervention that can transcend each sector’s paradigm. For Street Medicine teams, they have the option to, either, unilaterally develop processes that facilitate continuity of care for homeless individuals between themselves and untargeted providers, or alternatively, work with formal and public providers, as much as possible, to align parts of their care processes to better support continuity of care for homeless individuals.

Finally, the design of prospective interventions for the homeless, and their standardisation, should be informed by the central issues elucidated here in Street Medicine practice: the disconnect between the distinct needs of homeless individuals and the user-based technological inscriptions of the health system, the limited health agency the homeless possess to manage their health and act on advice, and Street Medicine’s collaboration with the untargeted health system. Street Medicine has already surpassed some barriers in being an outreach provider and dedicating human resources (referral manager) to supporting the usually difficult transition between multiple care providers across institutions for homeless individuals. More treatments are required which endow agency, provide it ‘by proxy’ such as the referral manager, or remove conditions on which subsequent health agency is contingent. This could, for example, include the transfer of medical record management from homeless individuals to Street Medicine teams, or the facilitation of treatment regimens or measures to improve compliance behaviours.

This study positioned the barriers to addressing healthcare needs for the homeless within the specific issues facing Street Medicine practices. The standardisation of such practice is changed from the implementation of ‘gold standard’ medical knowledge towards adapting practices in the face of locally-defined issues. For Street Medicine, applying the same practice across different homeless communities requires a clear definition of institutional roles, an understanding of the resources and capacities of communities being served, and therapies grounded in the community’s contextual realities. The findings also indicate that there are different demands to practice based on the homeless sub-group seeking care. Rather than developing a guideline or pathway from the characteristics of a sub-group, documenting the current standard pathways for these groups is a first step in identifying common issues these groups face.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the team at the Centre for Equity Studies who work for homeless and other disadvantaged communities in India, and those who made this work possible, particularly Armaan Alkazi, as well as the respondents for their alliance and insight.

Disclosure statement

There are no financial interests to declare. HM is the founder and director of the Centre for Equity Studies, which runs the Street Medicine programme at the centre of this published work. However, the data, findings and interpretation of these have no influence on this author’s position in the organisation. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability statement

The underlying data of this paper are stored on personal machines with copies limited to the authors. Depositing the data in a publicly available depository would contravene the terms of the informed consent given by participants, and given the research includes vulnerable individuals, there are ethical implications to sharing responses more widely. The authors would be happy to discuss requests for underlying data once the purpose of such secondary data use is known.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ament, S. M. C., de Groot, J. J. A., Maessen, J. M. C., Dirksen, C. D., van der Weijden, T., & Kleijnen, J. (2015). Sustainability of professionals’ adherence to clinical practice guidelines in medical care: A systematic review. BMJ Open, 5(12), e008073. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008073

- Andersen, R. M., Davidson, P. L., & Baumeister, S. E. (2013). Improving access to care. In G. F. Kominski (Ed.), Changing the US Health Care System: Key Issues in Health Services Policy and Management (pp. 33–70). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Angell, B. J., Prinja, S., Gupt, A., Jha, V., & Jan, S. (2019). The Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana and the path to universal health coverage in India: Overcoming the challenges of stewardship and governance. PLOS Medicine, 16(3), e1002759. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002759

- Argintaru, N., Chambers, C., Gogosis, E., Farrell, S., Palepu, A., Klodawsky, F., & Hwang, S. W. (2013). A cross-sectional observational study of unmet health needs among homeless and vulnerably housed adults in three Canadian cities. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 577. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-577

- Baggett, T. P., O’Connell, J. J., Singer, D. E., & Rigotti, N. A. (2010). The unmet health care needs of homeless adults: A national study. American Journal of Public Health, 100(7), 1326–1333. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.180109

- Beijer, U., Andreasson, S., Ågren, G., & Fugelstad, A. (2011). Mortality and causes of death among homeless women and men in Stockholm. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 39(2), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494810393554

- Borysow, I. d. C., & Furtado, J. P. (2014). Access, equity and social cohesion: Evaluation of intersectoral strategies for people experiencing homelessness. Revista Da Escola de Enfermagem Da USP, 48(6), 1069–1076. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0080-623420140000700015

- Bramley, G., Fitzpatrick, S., Edwards, J., Ford, D., Johnsen, S., Sosenko, F., & Watkins, D. (2015). Hard edges: Mapping severe and multiple disadvantage. London: Lankelly Chase.

- Burt, M. R. (2001). Helping America’s homeless: Emergency shelter or affordable housing?. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute Press.

- Calsyn, R. J., & Roades, L. A. (1994). Predictors of past and current homelessness. Journal of Community Psychology, 22(3), 272–278. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6629(199407)22:3<272::AID-JCOP2290220307>3.0.CO;2-X

- Canavan, R., Barry, M. M., Matanov, A., Barros, H., Gabor, E., Greacen, T., Holcnerová, P., Kluge, U., Nicaise, P., Moskalewicz, J., Díaz-Olalla, J. M., Straßmayr, C., Schene, A. H., Soares, J. J. F., Gaddini, A., & Priebe, S. (2012). Service provision and barriers to care for homeless people with mental health problems across 14 European capital cities. BMC Health Services Research, 12(1), 222. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-222

- Clinks, Drug Scope, Homeless Link, & Mind. (2009). Making every adult matter (MEAM): A four point manifesto for tackling multiple needs and exclusions. London: Making every adult matter.

- Commission on Social Determinants of Health. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: WHO.

- Crisis. (2002). Policy brief: Critical condition, vulnerable single homeless people and access to GPs. Crisis, https://doi.org/10.1049/et:20080116

- Epstein, S. (2008). Inclusion: The politics of difference in medical research. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Fazel, S., Geddes, J. R., & Kushel, M. (2014). The health of homeless people in high-income countries: Descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. The Lancet, 384(9953), 1529–1540. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6

- Fitzpatrick, S., Johnsen, S., & White, M. (2011). Multiple exclusion homelessness in the UK: Key patterns and intersections. Social Policy and Society, 10(4), 501–512. https://doi.org/10.1017/S147474641100025X

- Gelberg, L., Browner, C. H., Lejano, E., & Arangua, L. (2004). Access to women’s health care: A qualitative study of barriers perceived by homeless women. Women & Health, 40(2), 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1300/J013v40n02_06

- Gelberg, L., Gallagher, T. C., Andersen, R. M., & Koegel, P. (1997). Competing priorities as a barrier to medical care among homeless adults in Los Angeles. American Journal of Public Health, 87(2), 217–220. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.87.2.217

- Haber, M. G., & Toro, P. A. (2004). Homelessness among families, children, and adolescents: An ecological–developmental perspective. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 7(3), 3. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:ccfp.0000045124.09503.f1

- HIGH. (2003). Health care beyond zero. New Delhi: Health Initiative Group for the Homeless.

- Holmberg, L. (2006). Task uncertainty and rationality in medical problem solving. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 18(6), 458–462. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzl043

- Hwang, S. W., Chambers, C., Chiu, S., Katic, M., Kiss, A., Redelmeier, D. A., & Levinson, W. (2013). A comprehensive assessment of health care utilization among homeless adults under a system of universal health insurance. American Journal of Public Health, 103(S2), S294–S301. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301369

- Hwang, S. W., Kirst, M. J., Chiu, S., Tolomiczenko, G., Kiss, A., Cowan, L., & Levinson, W. (2009). Multidimensional social support and the health of homeless individuals. Journal of Urban Health, 86(5), 791–803. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-009-9388-x

- Hwang, S. W., Weaver, J., Aubry, T., & Hoch, J. S. (2011). Hospital costs and length of stay among homeless patients admitted to medical, surgical, and psychiatric services. Medical Care, 49(4), 350–354. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e318206c50d

- Indo-Global Social Service Society. (2012). The unsung cityMakers: A study of the homeless residents in Delhi. New Delhi: Indo-Global Social Service Society.

- Kennett, P., & Marsh, A. (1999). Homelessness: Exploring the new terrain. Bristol: The Policy Press.

- Kushel, M. B. (2001). Factors associated with the health care utilization of homeless persons. Journal of the American Medical Association, 285(2), 200. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.285.2.200

- Kushel, M. B., Gupta, R., Gee, L., & Haas, J. S. (2006). Housing instability and food insecurity as barriers to health care among low-income Americans. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(1), 71–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00278.x

- Levy, J. S. (1998). Homeless outreach: A developmental model. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 22(2), 123–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0095255

- Lipsky, M. (1980). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services. Russell Sage Foundation, https://doi.org/10.1086/643898

- Lowe, E. T., Poubelle, A., Thomas, G., Batko, S., & Layton, J. (2017). The U.S. conference of mayors’ report on hunger and homelessness: A status report on homelessness and hunger in America’s Cities, December 2016. Washington, D.C.: United States Conference of Mayors.

- Mander, H. (2008). Living rough, surviving city streets: A study of the homeless populations in Delhi, Chennai, Patna and Madurai for the Planning Commission of India. New Delhi: Planning Commission.

- Meeks, S., & Murrell, S. A. (1994). Service providers in the social networks of clients with severe mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 20(2), 399–406. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/20.2.399

- Morrison, D. S. (2009). Homelessness as an independent risk factor for mortality: Results from a retrospective cohort study. International Journal of Epidemiology, 38(3), 877–883. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyp160

- Mrazek, P. J., & Haggerty, R. J. (1994). Reducing risks for mental disorders: Frontiers for preventive intervention research. National Academy Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/2139

- Neale, J. (1997). Homelessness and theory reconsidered. Housing Studies, 12(1), 47–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673039708720882

- Nooe, R. M., & Patterson, D. A. (2010). The ecology of homelessness. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 20(2), 105–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911350903269757

- Oliveira, M. A. d., Boska, G. d. A., Oliveira, M. A. F. d., & Barbosa, G. C. (2021). Access to health care for people experiencing homelessness on Avenida Paulista: Barriers and perceptions. Revista Da Escola de Enfermagem Da USP, 55, e03744. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1980-220(2020033903744

- ORGI. (2011). Census of India 2011. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India.

- O’Toole, T. P., Gibbon, J. L., Hanusa, B. H., & Fine, M. J. (1999). Preferences for sites of care among urban homeless and housed poor adults. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 14(10), 599–605. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.09258.x

- Prasad, V. (2011). A study to understand the barriers and facilitating factors for accessing health care amongst adult street dwellers in New Delhi, India. University of the Western Cape.

- Press Information Bureau. (2018, March 21). Cabinet approves Ayushman Bharat – National Health Protection Mission. https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid = 177816.

- Rae, B. E., & Rees, S. (2015). The perceptions of homeless people regarding their healthcare needs and experiences of receiving health care. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(9), 2096–2107. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12675

- Reitzes, D. C., Crimmins, T. J., Yarbrough, J., & Parker, J. (2011). Social support and social network ties among the homeless in a downtown Atlanta park. Journal of Community Psychology, 39(3), 274–291. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20431

- Sharma, S. D. (2018). Health care for India’s 500 million: The promise of the National Health Protection Scheme. Harvard Public Health Review, 18, 1–14. (Fall 2018).

- Speak, S. (2013). Alternative understandings of homelessness in developing countries. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Global Urban Research Unit.

- Street Medicine Institute. (2018). About us. https://www.streetmedicine.org/about-us-article.

- Supreme Court Commissioner's Office. (2011). Delhi homeless shelter plan: rapid survey for mapping of urban homeless populations for shelter planning in Delhi. New Delhi: National Resource Team for the Homeless, Supreme Court Commissioner’s Office.

- Timmermans, S., & Berg, M. (2003). The gold standard: The challenges of evidence-based medicine and standardization in health care (issue February). Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Van Laere, I., & Withers, J. (2008). Integrated care for homeless people - sharing knowledge and experience in practice, education and research: Results of the networking efforts to find homeless health workers. European Journal of Public Health, 18(1), 5–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckm107

- Vuillermoz, C., Vandentorren, S., Brondeel, R., & Chauvin, P. (2017). Unmet healthcare needs in homeless women with children in the Greater Paris area in France. PLoS One, 12(9), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184138

- Wise, C., & Phillips, K. (2013). Hearing the silent voices: Narratives of health care and homelessness. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 34(5), 359–367. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2012.757402

- Zuiderent-Jerak, T. (2015). Situated standardization in hematology and oncology care. In T. Zuiderent-Jerak (Ed.), Situated intervention: Sociological experiments in health care (pp. 61–93). Cambridge: The MIT Press.