ABSTRACT

Trauma results in long-term socioeconomic outcomes that affect quality of life (QOL) after discharge. However, there is limited research on the lived experience of these outcomes and QOL from low – and middle-income countries. The aim of this study was to explore the different socioeconomic and QOL outcomes that trauma patients have experienced during their recovery. We conducted semi-structured qualitative interviews of 21 adult trauma patients between three to eight months after discharge from two tertiary-care public hospitals in Mumbai, India. We performed thematic analysis to identify emerging themes within the range of different experiences of the participants across gender, age, and mechanism of injury. Three themes emerged in the analysis. Recovery is incomplete—even up to eight months post discharge, participants had needs unmet by the healthcare system. Recovery is expensive—participants struggled with a range of direct and indirect costs and had to adopt coping strategies. Recovery is intersocial—post-discharge socioeconomic and QOL outcomes of the participants were shaped by the nature of social support available and their sociodemographic characteristics. Provisioning affordable and accessible rehabilitation services, and linkages with support groups may improve these outcomes. Future research should look at the effect of age and gender on these outcomes.

1. Background

Trauma accounts for one-tenth of disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) globally, a burden largely in low – and middle-income countries (LMICs) (GBD, Citation2019 Demographics Collaborators, Citation2020). To address the long-term burden of injury, it is important to understand how well patients recover and what challenges they face (Kruithof et al., Citation2017; Rios-Diaz et al., Citation2017; Wisborg et al., Citation2017). Throughout their recovery, patients face a range of social and economic burdens that extend beyond the clinical setting. Social functioning, job opportunities, community participation, and social relationships are affected (Abodey et al., Citation2020; Gabbe et al., Citation2016; Zuurmond et al., Citation2019). Out-of-pocket expenses and indirect financial costs due to temporary or permanent disability can lead to catastrophic expenditure (Nguyen et al., Citation2017; Word Health Organization, Citation2008). These socioeconomic outcomes substantially affect the health-related quality of life (QOL) in trauma patients (Kohler et al., Citation2017; Rohn et al., Citation2019).

Existing research largely relies on standardised measures of socioeconomic and QOL outcomes such as the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), Craig Hospital Assessment and Reporting Technique (CHART), EuroQol, Short Form (SF-36), and the World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL-BREF) (David et al., Citation2021; Jagnoor et al., Citation2019; Paiva et al., Citation2016; Vu et al., Citation2019) without exploring how different factors shape a patient’s lived experience of these outcomes as they try to recover to their preinjury status (Lasch et al., Citation2010; Rohn et al., Citation2019). Without detailed research exploring post-discharge outcomes from the patient’s perspective, important differences in recovery that may vary socially, remain underspecified.

Detailed studies tend to focus on specific socioeconomic outcomes such as returning to work, they look at trauma through a gender lens, or they focus on specific types of traumas (Fabricius et al., Citation2020; Kavosi et al., Citation2015; Kohler et al., Citation2017; Van Velzen et al., Citation2011). This creates barriers to an array of policies that may build capacity for improved medical management, rehabilitation, and support services. This is especially germane in LMICs, such as India, which have a significant global burden of mortality and morbidity due to trauma and have scope for trauma system improvement (Babhulkar et al., Citation2019; Zuurmond et al., Citation2019).

India accounts for nearly 20% of the global trauma burden (Dandona et al., Citation2020; GBD, Citation2019 Demographics Collaborators, Citation2020). More than one-tenth of all the DALYs in India are due to trauma, which is among the top five causes of morbidity in the country (Menon et al., Citation2019). Yet, the lived experience of post-discharge socioeconomic and QOL outcomes among trauma patients in India constitutes a gap in global public health research. The aim of this study is to explore the different socioeconomic and QOL outcomes that trauma patients in urban India have personally experienced during their recovery to preinjury status after hospital discharge. The study findings will describe post-discharge trauma recovery and may offer unique insights for policymakers and practitioners to improve trauma patient care in India and other similar LMIC contexts.

2. Methods

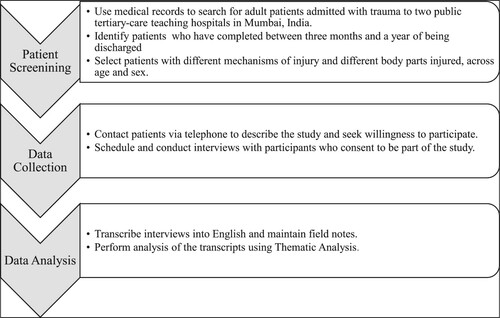

2.1. Design

This qualitative study employs thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews on the lived experiences of socioeconomic and QOL outcomes in post-discharge trauma patients. Semi-structured interviews were chosen as most suitable for gathering descriptive accounts, balancing consistent questions with the scope for probing emergent concerns particular to any given interviewee (Bailey, Citation2008; Hutchinson & Wilson, Citation1992).

2.2. Setting

The study was conducted in Mumbai, a city with a population of 18 million, with more than 9,000 trauma-related deaths each year—the highest in India (National Crime Records Bureau, Citation2020; Press Information Bureau, Citation2011). The city has a network of private and public healthcare facilities, with nearly half the population accessing public healthcare services—especially tertiary care—and predominantly among low-income groups (Praja Foundation, Citation2019). The sites of participant recruitment were two large public tertiary-care teaching hospitals in the city.

2.3. Participants

The participants were adult patients (18 years and older) admitted with a history of trauma. Purposive sampling was used in order to include different mechanisms of injury and different demographics groups. Participants were selected based on the body region injured and the mechanism of injury such as falls, road traffic injury, burns, and railway injury. We excluded patients admitted due to intentional injuries, as we did not have the required psychosocial training or expertise to engage in conversations about circumstances of their trauma and its effect on their post-discharge QOL. Demographic skewness was also kept in mind as most trauma patients in India are young male adults (Dasari, Citation2017). Participants able to speak Marathi, Hindi, or English (the languages of the city) were included. The participants were contacted between 3 months and a year after discharge so that they would have adequate time to settle into their lives and could describe the range of socioeconomic outcomes they experienced. The final number of participants was decided by consensus among the authors that data saturation had been achieved (Saunders et al., Citation2017).

2.4. Data collection instruments

The interview guide was exploratory to elicit responses of the participants’ lived experiences of socioeconomic and QOL outcomes after trauma. It was developed after a review of literature on these outcomes and through an iterative process between SD, MGW, and HS, based on existing literature. It included questions on perceived self-care, participation, economic aspects, and general quality of life. The initial draft was assessed for quality and appropriateness with colleagues working on trauma in India and then revised accordingly. Using the revised guide in the field also led to minor modifications based on the nature of responses from the participants. The final tool is available in the Appendices (Appendix 1). The transcripts were periodically assessed for any modifications in the interview schedule. Any unanticipated challenges during the interviews were immediately discussed with the research team and addressed.

2.5. Data collection

The selected participants were first contacted by telephone; SD and AA explained in detail the purpose of the study with assured anonymity and confidentiality. They were neither offered any incentive nor pressured to be part of the study. After expressing willingness to be interviewed, a time was scheduled as per their convenience. Before the interviews, participants were again briefed about the study and assured confidentiality. It was clarified that they did not have to answer all the questions and could end the interview at any point they wanted. After obtaining their consent the interviews were audio recorded.

The interviews lasted for 40–60 min and were conducted in the participants’ homes to ensure their comfort. Efforts were taken to ensure that the participants were by themselves as much as possible. In case the participant was incapacitated the primary caregiver—a close relative—was interviewed.

Mid-way through the study, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting lockdown, the interviews had to be conducted over the telephone. The interviews were conducted in Hindi and Marathi. SD conducted the face-to-face semi-structured interviews, while SD and AA conducted the telephonic interviews. Additionally, field notes were also maintained as a backup in the event of technical issues with the recordings and to document detailed descriptions and observations relevant to the study.

2.6. Data management

All the interviews were transcribed and translated verbatim into English by SD after each interview. The transcripts and field notes were de-identified for any personal information apart from relevant demographic and injury data. Only anonymised transcripts were stored and used for analysis. All the notes were stored in a digital format, securely maintained by SD, with limited access by MGW and HS .

2.7. Data analysis

The transcripts and notes were analysed using thematic analysis, which is best suited to identify emerging themes within the range of different experiences during post-discharge recovery among the participants and it followed a well-structured approach. (Braun & Clarke, Citation2014; Nowell et al., Citation2017). This analysis method uses codes to identify and summarise important concepts within a dataset and then groups them into sub-themes and themes. The process of identifying and coding the themes and sub-themes was carried out deductively, based on a previous literature review that partly shaped the questions in the interview schedule, and also inductively, based on themes that emerged from the notes using Braun and Clarke’s Phases of Thematic Analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). After reviewing the field notes, SD generated the initial codes and themes (Saunders et al., Citation2017). These were reviewed and discussed by the authors. A table with the codes along with corresponding themes and sub-themes has been included in the Appendices (Appendix 2).

2.8. Techniques to enhance trustworthiness

An audit trail with details of decisions and choices made and a reflexive process journal was maintained by SD and AA. These techniques, along with the transcripts and the detailed field notes, were periodically discussed by the study authors to increase the trustworthiness of the study (Nowell et al., Citation2017).

2.9. Researcher characteristics and reflexivity

SD, who conducted the interviews, has worked in public health research for a decade. He is from Mumbai and is part of the ongoing trauma studies in public hospitals in urban India. AA has been associated with collection and analysis of trauma patient data in Mumbai for over three years. MGW has been the principal investigator of the ongoing trauma projects in India for nearly a decade. HS has been conducting ethnographic work on trauma patients in Mumbai for the last five years (Solomon Citation2017, Citation2021), speaks Hindi and Marathi, and is familiar with the social contexts and home environments of the patients in the city. CSL has ongoing health research collaborations in India, extending for more than 15 years, as well as extensive experience of qualitative research. NR is a trauma surgeon with more than 30 years of experience and knowledge of trauma outcomes in different parts of India and other LMICs.

2.10. Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained for one of the study hospitals as an amendment to the ongoing project that SD and MGW are part of in that hospital (IEC/Pharm/CT/501/2018 dated 21.12.2018) In the other study hospital, approval was obtained as a new study (EC/52/19 dated 09.01.2020). Informed consent was solicited and recorded from all the participants before being interviewed. Permission was also sought to audio-record the interviews. A list of local charitable organisations and relevant public hospital departments were kept to share with the participants in case any assistance was sought when discussing about the range of socioeconomic challenges post-discharge. When contacting the potential participant, we checked if they would like to have the interview at their homes or any other location of their choice. All the participants suggested having the interviews at their homes. The interviews were held at the home of the participant at a time suitable to them, so as to be as non-intrusive to their daily lives as possible. Additionally, this helped in better understanding the outcomes in the context of that the participant was living in. However, this also meant that participants were at times interrupted by their family members or household tasks. Efforts were taken to reduce these distractions by pausing the interview or requesting the family member to let the participant speak. Time of day and place in the house with the least possibility of interruptions were selected to conduct the interview. Nevertheless, there were times that family members were present and this could have affected the responses of the participants.

Participation was voluntary and participants were informed of their right to withdraw or not answer any aspects of the interview at any time. It was also explained to the participants that while they may not directly benefit by being part of the study, the findings from this study may help improving health services for trauma patients in the future. It was decided that no monetary compensation would be provided, as we did not want participation to be influenced by it. There is an ethical concern of utilising the time of participants for something that they would not directly benefit from. However, building evidence on this subject through their interviews can help highlighting such problems and push for allocating more resources for research and improving services for the trauma patients in the future.

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics

A total of 21 post-discharge trauma patients were interviewed. Of these, 11 were interviewed at home, and the remaining participants were interviewed over the phone. In two cases, the patient was either unable to speak or not at home, so their caretakers (son and husband, respectively) were interviewed. The median age of the participants was 35 years and eight of the participants were female. The most common mechanism of injury was road traffic injury. The average time since hospital discharge was between three and eight months (mean 5.5 months, standard deviation = 1.17).

Around two-thirds of the participants were from low-income households living in dense quarters, most of them in poorly-maintained multi-story slum buildings with limited piped water. Many such buildings are on unevenly paved roads with poor drainage and are prone to flooding. Most participants used communal toilets. Dwellings were usually a single room house that served as the kitchen, the bedroom, and the living room. The rest were from lower-middle – and middle-income groups living in small apartments with one or two rooms and indoor plumbing. All the participants lived with their families, which included spouses, parents and/or children .

Table 1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Participants

3.2. Themes and sub-themes

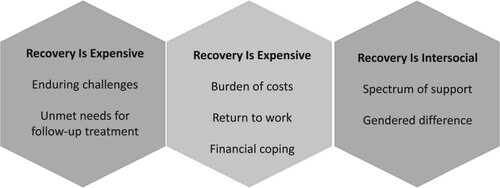

Three themes were identified in relation to the purpose of the research from the interviews: recovery is incomplete, recovery is expensive, and recovery is intersocial. A summary is provided in .

3.2.1. Recovery is incomplete

The participants described that they had not yet fully recovered from the traumatic injury, and experienced challenges in daily activities long after discharge.

3.2.1.1. Enduring challenges: Nearly all the participants reported experiencing some form of pain that persisted after discharge. Some of them had mobility problems and one-third of them reported using some form of mobility aid, such as walking sticks, braces, and walkers, to move around temporarily. Two participants were permanently disabled, one requiring crutches to walk and the other confined to the bed. Many participants reported still being unable to conduct activities of self-care such as bathing, using the toilet, and dressing themselves. Some reported problems with sleep. While almost all reported enduring pain, only two had been prescribed analgesics upon hospital discharge. Some explicitly framed injury-related pain as something that should be borne as a part of life, even though an injury was unexpected.

What is living without pain? Just don’t think about it and you can forget it.

—Male, 57, burns

My wife had to help me with going to the toilet [communal latrine] and keeping myself clean. But she cannot carry me to the toilet, so my nephew helps her. I cannot squat … so I have to hold on to him.

—Male, 54, polytrauma

I would control … . Only when it is really urgent would I go. I would drink less water; otherwise, I would have to urinate every now and then.

—Female, 55, hip injury

Sometimes I think about that day [of the traumatic injury] and my eyes water [crying]. I cannot explain it to anyone.

—Female, 32, hip injury

I just feel empty when I think about it … . I feel nothing.

—Male, 27, polytrauma

Even now when I hear the train whistle … I feel like I am losing my balance and going to fall.

—Female, 42, polytrauma

3.2.1.2. Unmet needs for follow-up treatment: Nearly two-thirds of the participants still required some form of treatment, such as physiotherapy and additional surgical intervention. One was waiting to get a prosthetic leg to aid his mobility. Yet, many noted that the conditions of public hospitals decreased their willingness to seek out this follow-up care.

You have to run around to get anything, and even then, they [hospital staff] are rude and don’t share anything with you. They have no time even to tell me if I am going to be alright or if there is a problem … . Why would I go there?

—Male, 54, polytrauma

It is so difficult to take her and bring her back. [We are] carrying her on our backs.

—Son of Female, 40, head injury

We had to get her discharged as they [hospital staff] told us [to].. That is why she was discharged, even though she was not back in [her] right condition.

—Son of Female, 40, head injury

I wish we could have stayed [at the hospital] … but they discharged him. Why should health be left half-done?

—Wife of Male, 40, polytrauma

3.2.2. Recovery is expensive

Participants shared a range of direct and indirect costs post-discharge, primarily involving medicines and diagnostic tests.

Coming back to normal life takes time and money. It's like an ‘adjustment charge’ … to get back to normal life. It is very expensive to get injured.

—Male, 28, polytrauma

If [we] go to do all the treatments, then we will have to become beggars. So, we only did what was important, and the rest we will have to adjust.

—Male, 35, polytrauma

3.2.2.1. Burden of costs: Nearly all the participants had to pay out-of-pocket for post-discharge treatment; only one returned to the government hospital for follow-up, where treatment was free. However, all participants had to pay out-of-pocket for medication post-discharge from private chemists. Compounded with factors including distance of travel to the government hospital, its quality of services, and perceived attitude of the staff, this meant that most participants sought follow-up treatment at private hospitals or clinics, even if they felt that the costs were exorbitant.

Private hospitals are there just to make money. [But the] service is much better than [in] government hospitals.

—Male, 40, polytrauma

We want to build [a toilet] to make it easy, but how can we spend so much money on this? We have to adjust.

—Female, 49, polytrauma

Work will not stop because you had an accident. Work is work; it feeds us. So, as soon as I was ready to stand up, I went back.

—Female, 42, polytrauma

3.2.2.2. Return to work: Of the 17 participants who had been engaged in some form of employment before suffering trauma, only six participants returned to the same job. Those who returned to the same job had desk-based jobs — clerks, accountants, and secretaries. Four returned to a different job, which paid lower than their original job. The rest of the participants were either semi-skilled or unskilled workers. Returning to work inside or outside the household was an event described as a sign of return to normal life.

I am fully fine now; see, I am going to work every day like before.

—Female, 39, burns

It [bed-rest after trauma] was around 1–2 months. Now I can do all the household chores, back to normal.

—Female, 50, polytrauma

It [economy] is difficult. Hardly any work is available. And now, [there are] no options at all for my line of work.

—Male, 54, polytrauma

If I am not there [at the workplace], there are thousands of younger people to do that work. Why would they want an older person like me?

—Male, 57, burns

I am not that educated to change to [another profession]. I only know this one. Where will I even learn something else in which I don’t have to use my legs?

—Male, 40, polytrauma

I had this plan to finish the course, get a job, and start helping my family. Now, that has all gone.

—Male, 20, leg injury

3.2.2.3. Financial coping: Nesides their own savings, participants described a range of sources for meeting the costs of their trauma care. Around half took advantage of help from family and neighbours, or sold their gold and landholdings. Others borrowed money from private moneylenders and community leaders. The majority of the participants found themselves in debt that would take years to repay, thus pointing out how recovery’s financial effects accrue long after discharge.

I don’t know if I will be able to make a living. The interest itself is more than half of what I bring home. It is not just food and clothing; there are other needs.

—Male, 31, polytrauma

All that I saved for the last 30 years is gone. The money we owe: the interest, and principal sum, will take at least five years to pay back.

—Female, 55, hip injury

3.2.3. Recovery is intersocial

The participants’ narratives detail how the consequences of trauma vary according to one’s social characteristics. Self-reported differences in age, gender, caste, religion, living situation, and economic status were understood to shape the nature of support one might receive, the different pathways of recovery, and one’s ability to cope.

3.2.3.1. Spectrum of support: All participants described the different types of support they received post-discharge. The participants also described the support from their families post-discharge.

My husband would do everything. He used to not go to work, as he had to look after me. So, he would look after me and also do the household chores.

—Female, 50, polytrauma

I am lucky that my father, my mother, and my brother were there.

—Male, 20, leg injury

But that is her duty, right? A wife and husband helping each other is their duty.

—Male, 54, polytrauma

Even if my father is not there … [and my] brother has gone to school, my mother could leave me alone to buy groceries, because my neighbours were there and they could keep an eye on me.

—Male, 20, leg injury

Anything that was not there at home, they [neighbours] would get it … I mean for anything, big or small.

—Female, 32, hip injury

My neighbour … is a Gujarati like us. So, we would get food from her.

—Female, 50, polytrauma

It is better to borrow [money] from them [members of one’s community]; they will not charge high interest rates.

—Male, 45, burns

She [a friend] would call me every day and keep telling me to get well soon and get back to normal. She was such a motivation to go back to work.

—Female, 39, burns

In the hospital, next to me was this old man who had an accident. His wife had died long ago. His children were all working. Who would be helping him at home?

—Male, 20, leg injury

This lady next to me at the hospital had a fall like me. She was quite old; her son must have come once or twice. The poor woman had no one to look after her … . She was stressed about going back home and was hoping that she would die in the hospital.

—Female, 32, hip injury

3.2.3.2. Gendered differences in care: The narratives of participants revealed how trauma recovery can be gendered in terms of support received and care labour obligations. Both men and women talked about returning to formal employment when they discussed returning to ‘normal.’ but almost all of the women in the sample defined recovering from trauma and returning to ‘normal’ in terms of performing household chores such as cooking, cleaning, and looking after the children. By contrast, male participants did not discuss such household care labours. Some of the female participants felt that there was pressure to recover sooner to be able to perform household chores.

As a woman, you have so many things that you have to manage around the house. How long can you just lie down like that?

—Female, 32, hip injury

How can he [the husband] manage the children and the cooking? … The burden on him is too much for a man … Therefore, as soon as I could move around a bit, I started doing all the work.

—Female, 42, polytrauma

Women have different needs. There are other gynaecology needs with which men can’t help us. Only a woman can buy what is required.

—Female, 32, hip injury

Since I lost the job, my wife has to bear all the responsibilities. It doesn’t feel right. If she is doing that, what is my need?

—Male, 35, spinal cord injury

We have to do everything by ourselves. We don’t have any sisters. It is just us brothers. There are no other related sisters or any other women [to help]. It is just us.

—Son of Female, 40, head injury

I am lucky that my husband looked after me the whole time. He managed the house, the children, my needs, and also went to work. How many men do that?

—Female, 39, burns

It was good that she [the mother] came from her village to help. She took care of all the household work. I could focus my attention on getting well.

—Female, 32, hip injury

We told her [the daughter] to come and help us. It was only then that I was relieved. I could look after my health now.

—Female, 49, polytrauma

4. Discussion

In this study we explored how trauma patients in urban India experience dynamic socioeconomic and QOL outcomes during their recovery after discharge in the city of Mumbai. We wanted to understand the participants’ perspectives on how the trauma affected their lives personally, socially, and economically, and how those perspectives might reveal internal differentiation. The participants reported pain, restricted mobility, and the inability to perform self-care, affecting their daily living even six months after discharge. This echoes findings from studies on post-discharge trauma patients in other settings (Gauffin et al., Citation2016; Kohler et al., Citation2017). The participants felt that these health challenges impeded their engagement in community and social activities. Limited physical functioning and pain have been shown to affect the quality of life among post-discharge trauma patients (Carr et al., Citation2017; Gauffin et al., Citation2016; Gopinath et al., Citation2017).

The participants expressed varied psychological needs, as expected in post-discharge trauma patients (Kendrick et al., Citation2017; Shah et al., Citation2017). Additionally, one case was listed as a railway injury, despite it being one of self-harm. However, deeper psychological matters were neither recognised by trauma healthcare providers nor identified as sites of care-seeking by the participants. Previous research has recommended looking at trauma through a psychosocial lens rather than from a perspective based on physiological needs alone, as doing so may improve the quality of life after discharge (Ogilvie et al., Citation2015; Spronk et al., Citation2018). Our results show that the line between the physiological and psychological may be blurred in accounts of QOL outcomes. Amidst narratives of pain and disability, participants often described informal and interpersonal ways of attending to psychological needs, such as receiving support from friends or neighbours; more formal psychological services were not sought out. Screening for psychological needs of the trauma patients at the time of discharge and during follow-ups as well as connecting them to relevant hospital departments or non-government organisations could be included as part of trauma management in health facilities.

Physiotherapy and pain relief were the most commonly reported needs that were not met by available healthcare services. Such existing services were described as expensive, poorly staffed, and inaccessible. The participants stressed the need for having a continuum of care for their recovery to address such unmet needs. Improving the reach of health services, making it affordable, and integrating different types of care has shown to provide a continuum of care for trauma patients, consequently improving QOL (Gudlavalleti, Citation2018; Palimaru et al., Citation2017). However, affordable and good-quality rehabilitation services remain largely unavailable across LMICs, where their need has been growing up to three times faster than in other countries (Jesus & Hoenig, Citation2019). This is an area that government schemes or public insurance programmes may be able to address.

The participants described at length how trauma resulted in a plethora of out-of-pocket direct health expenditures including treatment, medicines, and travelling for seeking care during their recovery. Social class, kin structures, and gender inflected these costs. Additionally, loss of jobs, legal costs, and making structural changes to their homes due to the restricted mobility added to their financial burden. The costs exacerbated the financial hardship on participants from low-income groups. Trauma is among the top causes of health expenditure in India and catastrophic health expenditure has been recognised as a major reason for poverty in India (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Citation2017; National Sample Survey Office, Citation2019; Prinja et al., Citation2016). Financial burden due to trauma has been documented as leading to indebtedness, financial hardships, and poverty (Hossain et al., Citation2020; Meara et al., Citation2015; Nguyen et al., Citation2017). Even in this study, participants have had to adopt strategies such as borrowing money, selling assets, relying on family members, taking up jobs, and cutting their living costs to meet the post-discharge expenses due to trauma.

The ability or inability to return to work was one of the most important features of recovery raised by the participants. Return to work marked the return to a pre-trauma state and economic outcome. Only one-third of the participants who were employed before the trauma were able to return to their previous jobs. Others were either unemployed or working in jobs with lower pay. Studies have shown that 25–75% of patients do not return to work after trauma (Athanasou, Citation2017; Chu et al., Citation2017; Gabbe et al., Citation2016). In our sample, it was participants with semi-skilled or manual labour jobs who could not receive employment. This is consistent with other research, which indicates that better education, skill-sets, and socioeconomic status are positively corelated with returning to work after trauma (Bhattacherjee & Kunar, Citation2016; Dinh et al., Citation2016; Gewurtz et al., Citation2019). Those participants who returned to work reported support from their employers and colleagues along with a suitable work environment to return to. Such workplace conditions have been shown to improve return to work among trauma patients (Bush et al., Citation2016; Hilton et al., Citation2018; Van Velzen et al., Citation2011).

The participants described in detail the range of social support they received during and after discharge. Family members and neighbours helped the participants in moving around, completing self-care needs, and performing daily activities, and they also provided emotional support and financial assistance. Given the physical, psychological, and financial problems participants faced, such support is integral to post-discharge recovery and rehabilitation. It also demonstrates how recovery from trauma is social and relational. The role of social support in returning to preinjury status and as a determinant of QOL has been illustrated in multiple studies (Ferdiana et al., Citation2018; Idrees et al., Citation2017; Songwathana et al., Citation2018). Our findings also demonstrate a need for studies to better account for patients with limited social support who may not have networks to draw on as a resource. Public welfare programmes, non-governmental organisations, and civil-society organisations can play a role in providing support to these groups of patients.

Participants’ narratives highlighted the important role of caregivers such as spouses, parents, and children who looked after the needs of the participants. This care labour often was carried out alongside other domestic tasks, professional responsibilities, and taking time off from formal employment to help. Though the responsibilities of these caregivers were seen as part of familial duty, participants gratefully acknowledged the burden shouldered by these individuals. The informal caregiver is a key aspect of trauma recovery, and the physical, emotional, and financial toll it takes on them has been observed in literature (Aktasa & Sertel-berk, Citation2015; Qadeer et al., Citation2017; Zanini & Amann, Citation2021). Scholars also demonstrate that providing support services to informal caregivers may offset the challenges they face (Hickey et al., Citation2018; Jones et al., Citation2020; Shepherd-Banigan et al., Citation2018). There is an urgency to understand the specific needs of the informal caregivers of post-discharge trauma patients in the Indian context and develop solutions to address their needs.

The gendered dimensions of recovery, especially gendered labour, were key to participants’ experiences. It was difficult to recruit women for the study due to the fact that a smaller proportion of women are admitted with injuries in India. Female participants felt the added pressure of having to get back to performing household chores in addition to returning to formal employment post-discharge. Sometimes, support to female participants post-discharge involved managing her domestic tasks rather than looking after her own needs. Traditional gender roles seem to shape caregiving, as women were the primary caregivers. In situations where no female caregivers were available, female relatives from outside the household would travel to take care of injured female participants. Previous research has shown that gender norms and roles shape post-discharge socioeconomic and QOL outcomes in trauma patients (Colantonio, Citation2016; Haag et al., Citation2016; Levi et al., Citation2018; Mollayeva et al., Citation2018). The guilt expressed by the female participants for not being able to perform their domestic roles and gendered caregiving roles and expectations have also been illustrated (Fabricius et al., Citation2020; Kohler et al., Citation2017). Body image issues were not reported by the female participants in this study, though studies in other settings indicate that body image plays a role in recovery among women (Connell et al., Citation2014). We were unable to identify and contact any transgender participants to include in this study, future studies should include this vulnerable gender group.

Age was not a key factor that differentiated recovery in our study sample. The four participants over the age of 50 years, including one over 70 years, had largely similar socioeconomic experiences as younger patients in the sample. This could be because they did not share specific lack of support or neglect in caregiving. Research indicates that older adults with trauma have poorer post-discharge socioeconomic and QOL outcomes (Rissanen et al., Citation2017). Some of the older participants felt that their age limited their post-discharge opportunities for work. This is consistent with findings reported by other studies linking older age with lower possibilities of returning to work (Awang & Mansor, Citation2018; Cancelliere et al., Citation2016). In India, older populations, especially older women, have limited financial security, and the absence of adequate social and financial support would have poor socioeconomic outcomes due to trauma (Agarwal et al., Citation2016; Agrawal & Keshri, Citation2014; Arokiasamy & Yadav, Citation2014). Therefore, more research is required to study in detail how age and gender intersect as potential sources of difference in socioeconomic and QOL outcomes.

5. Methodological considerations

To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study from India that examines post-discharge recovery among trauma patients. Every effort was employed to make the sample representative of an urban Indian trauma patient population in terms of age, gender, and mechanism of injury. However, certain mechanisms such as assaults and self-harm were not represented in this sample, in terms of the injury reported by the hospital. Additionally, we were unable to include certain types of injury outcomes, such as paraplegia and quadriplegia. The post-discharge experiences of these groups may differ from those of the participants in our study. The city of Mumbai may not completely represent other urban populations of India. All the interviews were conducted at a single point in time, and thus our study reflects experiences of the participants at that moment.

Researcher positions and perspectives may have influenced the analysis and interpretation of data. To address this, the study employed periodic review and discussions between the authors and adherence to principles of thematic analysis. Interviews were conducted at participants’ homes and in the presence of family members, and this may have influenced their responses. Efforts were made to limit the interaction between other family members and the participants. Still, home-based interviews are consistent with the Indian social context and prioritise the convenience of participants. Half the interviews were conducted via telephone due to the COVID-19 restrictions, which limited the possibility for observations and interactions during the interviews.

6. Conclusion

Our study contributes evidence of the diverse and dynamic socioeconomic and QOL outcomes trauma patients experience after discharge in LMICs settings like urban India. The study’s findings indicate that there are unmet health needs, acute financial burdens, types of social support, and various sociodemographic factors among trauma patients that affect their quality of life. There is a need to enhance the trauma service provision by providing affordable and accessible services such as physiotherapy and rehabilitation that can create a continuum of care and reduce barriers to affordable care post-discharge. Options like peer-to-peer support groups, patients support groups, and linkages with local non-governmental organisations might enhance offerings of the healthcare system. Such options might also better address the socially dynamic needs of women, older adults, and people from lower socioeconomic groups differently affected by trauma in the Indian context. Further research into the needs of caregivers, outcomes of patients with limited social support, and the interaction of age and gender on QOL outcomes in LMIC settings is warranted.

Authors’ contributions

SD, NR, HR, CSL, and MGW contributed to the study conception and design of the study. Data collection and analysis was performed by SD and supervised by MGW and HR. The first draft of the manuscript was written by SDD and HR. NR, CSL, and MGW reviewed and commented on the versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of supporting data

The interview tool is provided in the Appendices

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval obtained for one of the study hospitals in this study as an amendment to the ongoing study that SD and MGW are part of in that of the hospitals. In the other study hospital, approval was obtained as a new study (IEC/Pharm/CT/501/2018 dated 21.12.2018 and EC/52/19 dated 09.01.2020). Informed consent was solicited and recorded from all the participants before being interviewed.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their deepest gratitude Anna Aaroke for being part of the data collection process and Dr. Vineet Kumar for all the support in securing permissions for the study. A special thanks to all the members of the Thursday Truth Seekers, Mumbai, especially Rakhi Ghoshal, for their support and feedback in shaping the paper. The authors would also like to thank Anindra Z. Siqueira for proof-reading and editing the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abodey, E., Vanderpuye, I., Mensah, I., & Badu, E. (2020). In search of universal health coverage-highlighting the accessibility of health care to students with disabilities in Ghana: A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research, 20(270), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05138-0

- Agarwal, A., Lubet, A., Mitgang, E., Mohanty, S., & Bloom, D. E. (2016). Population Aging in India: Facts, Issues, and Options, 30(10162), 289–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0230-4_13

- Agrawal, G., & Keshri, K. (2014). Morbidity patterns and health care seeking behavior among older widows in India. PLoS ONE, 9(4), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0094295

- Aktasa, A., & Sertel-berk, H. O. (2015). Social support reciprocity in terms of psychosocial variables in care taking and care giving processes of spinal cord injury patients and their care givers. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 205(May), 564–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.09.076

- Arokiasamy, P., & Yadav, S. (2014). Changing age patterns of morbidity vis-à-vis mortality in India. Journal of Biosocial Science, 46(4), 462–479. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002193201300062X

- Athanasou, J. A. (2017). A vocational rehabilitation index and return to work after compensable occupational injuries in Australia. The Australian Journal of Rehabilitation Counselling, 23(2), 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1017/jrc.2017.8

- Awang, H., & Mansor, N. (2018). Predicting employment status of injured workers following a case management intervention. Safety and Health at Work, 9(3), 347–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2017.11.001

- Babhulkar, S., Apte, A., Barick, D., Hoogervorst, P., Tian, Y., & Wang, Y. (2019). Trauma care systems in India and China. OTA International: The Open Access Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 2(S1), e017. https://doi.org/10.1097/OI9.0000000000000017

- Bailey, K. (2008). Methods of social research (4th ed). Free Press.

- Bhattacherjee, A., & Kunar, B. (2016). Miners’ return to work following injuries in coal mines. Medycyna Pracy, 67(6), 729–742. https://doi.org/10.13075/mp.5893.00429

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2014). What can ‘thematic analysis’ offer health and wellbeing researchers? International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 9(1), 9–10. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v9.26152

- Bush, E. J., Hux, K., Guetterman, T. C., & McKelvey, M. (2016). The diverse vocational experiences of five individuals returning to work after severe brain injury: A qualitative inquiry. Brain Injury, 30(4), 422–436. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699052.2015.1131849

- Cancelliere, C., Donovan, J., Stochkendahl, M. J., Biscardi, M., Ammendolia, C., Myburgh, C., & Cassidy, J. D. (2016). Factors affecting return to work after injury or illness: Best evidence synthesis of systematic reviews. Chiropractic & Manual Therapies, 24(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12998-016-0113-z

- Carr, J. J., Kendall, M. B., Amsters, D. I., Pershouse, K. J., Kuipers, P., Buettner, P., & Barker, R. N. (2017). Community participation for individuals with spinal cord injury living in Queensland, Australia. Spinal Cord, 55(2), 192–197. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2016.169

- Chu, S., Tsai, Y., Xiao, S., & Huang, S. (2017). Quality of return to work in patients with mild traumatic brain injury : a prospective investigation of associations among post-concussion symptoms, neuropsychological functions, working status and stability. Brain Injury, 31(12), 1674–1682. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2017.1332783

- Colantonio, A. (2016). Sex, gender, and traumatic brain injury: A commentary. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 97(2 Suppl), S1–S4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2015.12.002

- Connell, K. M., Coates, R., & Wood, F. M. (2014). Burn injuries lead to behavioral changes that impact engagement in sexual and social activities in females. Sexuality and Disability, 33(1), 75–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-014-9360-x

- Dandona, R., Kumar, G. A., Gururaj, G., James, S., Chakma, J. K., Thakur, J. S., Srivastava, A., Kumaresh, G., Glenn, S. D., Gupta, G., Krishnankutty, R. P., Malhotra, R., Mountjoy-Venning, W. C., Mutreja, P., Pandey, A., Shukla, D. K., Varghese, C. M., Yadav, G., Reddy, K. S., … Dandona, L. (2020). Mortality due to road injuries in the states of India: The global burden of disease study 1990–2017. The Lancet Public Health, 5(2), e86–e98. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30246-4

- Dasari, M. (2017). Comparative analysis of gender differences in outcomes after trauma in India and the USA: Case for standardised coding of injury mechanisms in trauma registries. BMJ Global Health, 2(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000322

- David, S. D., Roy, N., Solomon, H., Lundborg, C. S., & Wärnberg, M. G. (2021). Measuring post-discharge socioeconomic and quality of life outcomes in trauma patients: A scoping review. Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes, 5(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-021-00346-6

- Dinh, M. M., Cornwall, K., Bein, K. J., Gabbe, B. J., Tomes, B. A., & Ivers, R. (2016). Health status and return to work in trauma patients at 3 and 6 months post-discharge: An Australian major trauma centre study. European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery, 42(4), 483–490. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-015-0558-0

- Fabricius, A. M., D’Souza, A., Amodio, V., Colantonio, A., & Mollayeva, T. (2020). Women’s gendered experiences of traumatic brain injury. Qualitative Health Research, 30(7), 1033–1044. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732319900163

- Ferdiana, A., Post, M. W. M., King, N., Bültmann, U., & van der Klink, J. J. L. (2018). Meaning and components of quality of life among individuals with spinal cord injury in Yogyakarta Province, Indonesia. Disability and Rehabilitation, 40(10), 1183–1191. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1294204

- Gabbe, B. J., Simpson, P. M., Harrison, J. E., Lyons, R. A., Ameratunga, S., Ponsford, J., Fitzgerald, M., Judson, R., Collie, A., & Cameron, P. A. (2016). Return to work and functional outcomes after major trauma: Who recovers, when, and How well? Annals of Surgery, 263(4), 623–632. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000001564

- Gauffin, E., Öster, C., Sjöberg, F., Gerdin, B., & Ekselius, L. (2016). Health-related quality of life (EQ-5D) early after injury predicts long-term pain after burn. Burns, 42(8), 1781–1788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2016.05.016

- GBD 2019 Demographics Collaborators. (2020). Global age-sex-specific fertility, mortality, healthy life expectancy (HALE), and population estimates in 204 countries and territories, 1950–2019: A comprehensive demographic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. The Lancet, 396(10258), 1160–1203. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30977-6

- Gewurtz, R. E., Premji, S., & Holness, D. L. (2019). The experiences of workers who do not successfully return to work following a work-related injury. Work, 61(4), 537–549. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-182824

- Gopinath, B., Jagnoor, J., Elbers, N., & Cameron, I. D. (2017). Overview of findings from a 2-year study of claimants who had sustained a mild or moderate injury in a road traffic crash: Prospective study. BMC Research Notes, 10(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2401-7

- Gudlavalleti, V. S. (2018). Challenges in accessing health care for people with disability in the south asian context: A review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(11), 2366. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112366

- Haag, H. L., Caringal, M., Sokoloff, S., Kontos, P., Yoshida, K., & Colantonio, A. (2016). Being a woman with acquired brain injury: Challenges and implications for practice. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 97(2), S64–S70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2014.12.018

- Hickey, L., Anderson, V., Hearps, S., & Jordan, B. (2018). Family forward: A social work clinical trial promoting family adaptation following paediatric acquired brain injury. Brain Injury, 32(7), 867–878. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2018.1466195

- Hilton, G., Unsworth, C., & Murphy, G. (2018). The experience of attempting to return to work following spinal cord injury: A systematic review of the qualitative literature. Disability and Rehabilitation, 40(15), 1745–1753. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1312566

- Hossain, M. S., Harvey, L. A., Islam, M. S., Rahman, M. A., Liu, H., & Herbert, R. D. (2020). Loss of work-related income impoverishes people with SCI and their families in Bangladesh. Spinal Cord, 58(4), 423–429. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-019-0382-1

- Hutchinson, S., & Wilson, H. (1992). Validity threats in scheduled semistructured research interviews. Nursing Research, 41(2), 117–119. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-199203000-00012

- Idrees, S., Faize, F. A., & Akhtar, M. (2017). Psychological reactions, social support, and coping styles in Pakistani female burn survivors. Journal of Burn Care & Research, 38(6), e934–e943. https://doi.org/10.1097/BCR.0000000000000525

- Jagnoor, J., Prinja, S., Nguyen, H., Gabbe, B. J., Peden, M., & Ivers, R. Q. (2019). Mortality and health-related quality of life following injuries and associated factors: A cohort study in chandigarh, north India. Injury Prevention, 26, 315–323. https://doi.org/10.1136/injuryprev-2019-043143

- Jesus, T. S., & Hoenig, H. (2019). Crossing the global quality chasm in health care: Where does rehabilitation stand? Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 100, 2215–2217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2019.07.001

- Jones, K., Theadom, A., Prah, P., Starkey, N., Barker-Collo, S., Ameratunga, S., & Feigin, V. L. (2020). Changes over time in family members of adults with mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Impairment, 21, 154–172. https://doi.org/10.1017/BrImp.2019.27

- Kavosi, Z., Jafari, A., Hatam, N., & Enaami, M. (2015). The economic burden of traumatic brain injury Due to fatal traffic accidents in shiraz shahid rajaei trauma hospital, shiraz, Iran. Archives of Trauma Research, 4(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.5812/atr.22594

- Kendrick, D., Kelllezi, B., Coupland, C., Maula, A., Beckett, K., Morriss, R., Joseph, S., Barnes, J., Sleney, J., & Christie, N. (2017). Psychological morbidity and health-related quality of life after injury: Multicentre cohort study. Quality of Life Research, 26(5), 1233–1250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1439-7

- Kohler, R. E., Tomlinson, J., Chilunjika, T. E., Young, S., Hosseinipour, M., & Lee, C. N. (2017). “Life is at a standstill” quality of life after lower extremity trauma in Malawi. Quality of Life Research, 26(4), 1027–1035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1431-2

- Kruithof, N., de Jongh, M. A. C., de Munter, L., Lansink, K. W. W., & Polinder, S. (2017). The effect of socio-economic status on non-fatal outcome after injury: A systematic review. Injury, 48(3), 578–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2017.01.013

- Lasch, K. E., Marquis, P., Vigneux, M., Abetz, L., Arnould, B., Bayliss, M., Crawford, B., & Rosa, K. (2010). Pro development: Rigorous qualitative research as the crucial foundation. Quality of Life Research, 19(8), 1087–1096. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9677-6

- Levi, B., Kraft, C. T., Shapiro, G. D., Trinh, N. T., Dore, E. C., Jeng, J., Lee, A. F., Acton, A., Marino, M., Jette, A., Armstrong, E. A., Schneider, J. C., Kazis, L. E., & Ryan, C. M. (2018). The associations of gender with social participation of burn survivors: A life impact burn recovery evaluation profile study. Journal of Burn Care & Research, 39(6), 915–922. https://doi.org/10.1093/jbcr/iry007

- Meara, J. G., Leather, A. J. M., Hagander, L., Alkire, B. C., Alonso, N., Ameh, E. A., Bickler, S. W., Conteh, L., Dare, A. J., Davies, J., Mérisier, E. D., El-Halabi, S., Farmer, P. E., Gawande, A., Gillies, R., Greenberg, S. L. M., Grimes, C. E., Gruen, R. L., Ismail, E. A., … Yip, W. (2015). Global surgery 2030: Evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. The Lancet, 386(9993), 569–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60160-X

- Menon, G. R., Singh, L., Sharma, P., Yadav, P., Sharma, S., Kalaskar, S., Singh, H., Adinarayanan, S., Joshua, V., Kulothungan, V., Yadav, J., Watson, L. K., Fadel, S. A., Suraweera, W., Rao, M. V. V., Dhaliwal, R. S., Begum, R., Sati, P., Jamison, D. T., & Jha, P. (2019). National burden estimates of healthy life lost in India, 2017: An analysis using direct mortality data and indirect disability data. The Lancet Global Health, 7(12), e1675–e1684. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30451-6

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. (2017). National health policy 2017. http://cdsco.nic.in/writereaddata/National-Health-Policy.pdf.

- Mollayeva, T., Mollayeva, S., & Colantonio, A. (2018). Traumatic brain injury: Sex, gender and intersecting vulnerabilities. Nature Reviews Neurology, 14(12), 711–722. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-018-0091-y

- National Crime Records Bureau. (2020). Accidental deaths and suicides in India 2019. https://ncrb.gov.in/sites/default/files/ADSI_2019_FULL REPORT_updated.pdf.

- National Sample Survey Office. (2019). Key indicators of social consumption in India: Health. In Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. http://mail.mospi.gov.in/index.php/catalog/161/download/1949.

- Nguyen, H., Ivers, R., Jan, S., & Pham, C. (2017). Analysis of out-of-pocket costs associated with hospitalised injuries in Vietnam. BMJ Global Health, 2(1), e000082. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000082

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- Ogilvie, R., Foster, K., McCloughen, A., & Curtis, K. (2015). Young peoples’ experience and self-management in the six months following major injury: A qualitative study. Injury, 46(9), 1841–1847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2015.05.036

- Paiva, L., Pompeo, D. A., Ciol, M. A., Arduini, G. O., Dantas, R. A. S., Senne, E. C. V. d., & Rossi, L. A. (2016). Estado de saúde e retorno ao trabalho após os acidentes de trânsito. TT - Estado de saúde e retorno ao trabalho após os acidentes de trânsito. TT - health status and the return to work after traffic accidents. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 69(3), 443–450. http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script = sci_arttext&nrm = iso&lng = pt&tlng = pt&pid = S0034-71672016000300443. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167.2016690305i.

- Palimaru, A., Cunningham, W. E., Dillistone, M., Vargas-Bustamante, A., Liu, H., & Hays, R. D. (2017). A comparison of perceptions of quality of life among adults with spinal cord injury in the United States versus the United Kingdom. Quality of Life Research, 26(11), 3143–3155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1646-x

- Praja Foundation. (2019). Report on the state of health in Mumbai (Issue September). https://www.praja.org/praja_docs/praja_downloads/Report on The STATE of HEALTH in Mumbai.pdf.

- Press Information Bureau. (2011). INDIA STATS : Million plus cities in India as per Census 2011. Census Population 2021 Data. http://pibmumbai.gov.in/scripts/detail.asp?releaseId = E2011IS3.

- Prinja, S., Jagnoor, J., Chauhan, A. S., Aggarwal, S., Nguyen, H., & Ivers, R. (2016). Article: Economic burden of hospitalization due to injuries in North India: A cohort study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(7), 673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13070673

- Qadeer, A., Khalid, U., Amin, M., Murtaza, S., Khaliq, M. F., & Shoaib, M. (2017). Caregiver’s burden of the patients with traumatic brain injury. Cureus, 9(8), e1590. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.1590

- Rios-Diaz, A. J., Herrera-Escobar, J. P., Lilley, E. J., Appelson, J. R., Gabbe, B., Brasel, K., Deroon-Cassini, T., Schneider, E. B., Kasotakis, G., Kaafarani, H., Velmahos, G., Salim, A., & Haider, A. H. (2017). Routine inclusion of long-term functional and patient-reported outcomes into trauma registries: The FORTE project. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 83(1), 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000001490

- Rissanen, R., Berg, H. Y., & Hasselberg, M. (2017). Quality of life following road traffic injury: A systematic literature review. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 108, 308–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2017.09.013

- Rohn, E. J., Tate, D. G., Forchheimer, M., & DiPonio, L. (2019). Contextualizing the lived experience of quality of life for persons with spinal cord injury: A mixed-methods application of the response shift model. The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 42(4), 469–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790268.2018.1517471

- Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2017). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity, 52, 1893–1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

- Shah, S. Z. A., Rafiullah, & Ilyas, S. M. (2017). Assessment of the quality of life of spinal cord injury patients in peshawar. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 67(3), 434–437.

- Shepherd-Banigan, M. E., Shapiro, A., McDuffie, J. R., Brancu, M., Sperber, N. R., Van Houtven, C. H., Kosinski, A. S., Mehta, N. N., Nagi, A., & Williams, J. W. (2018). Interventions that support or involve caregivers or families of patients with traumatic injury: A systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33(7), 1177–1186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4417-7

- Solomon, H. (2017). Shifting gears: Triage and traffic in urban India. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 31(3), 349–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12367

- Solomon, H. (2021). Epidemiology in motion: Traumatic brain injuries in Mumbai. South Asia: Journal of South Asia Studies, 44(6), 1134–1145. https://doi.org/10.1080/00856401.2021.1984430

- Songwathana, P., Kitrungrote, L., Anumas, N., & Nimitpan, P. (2018). Predictive factors for health-related quality of life among Thai traumatic brain injury patients. The Journal of Behavioral Science, 13(1), 82–92. https://www.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/IJBS/article/view/81933.

- Spronk, I., Legemate, C. M., Polinder, S., & Van Baar, M. E. (2018). Health-related quality of life in children after burn injuries: A systematic review. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 85(6), 1110–1118. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000002072

- Van Velzen, J. M., Van Bennekom, C. A. M., Van Dormolen, M., Sluiter, J. K., & Frings-Dresen, M. H. W. (2011). Factors influencing return to work experienced by people with acquired brain injury: A qualitative research study. Disability and Rehabilitation, 33(23–24), 2237–2246. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2011.563821

- Vu, H. M., Dang, A. K., Tran, T. T., Vu, G. T., Truong, N. T., Nguyen, C. T., Doan, A. V., Pham, K. T. H., Tran, T. H., Tran, B. X., Latkin, C. A., Ho, C. S. H., & Ho, R. C. M. (2019). Health-Related quality of life profiles among patients with different road traffic injuries in an urban setting of Vietnam. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health [Electronic Resource], 16(8), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16081462

- Wisborg, T., Manskow, U. S., & Jeppesen, E. (2017). Trauma outcome research – more is needed. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica, 61(4), 362–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/aas.12875

- Word Health Organization. (2008). Manual for estimating the economic costs of injuries due to interpersonal and self-directed violence. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43837/1/9789241596367_eng.pdf.

- Zanini, C., & Amann, J. (2021). The challenges characterizing the lived experience of caregiving. A qualitative study in the field of spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord, 59(5), 493–503. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-021-00618-4

- Zuurmond, M., Mactaggart, I., Kannuri, N., Murthy, G., Oye, J. E., & Polack, S. (2019). Barriers and facilitators to accessing health services: A qualitative study amongst people with disabilities in Cameroon and India. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(7), 1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071126

Appendices

Appendix 1: Interview Tool

A.#Background

Could you tell me a bit about yourself?

- Age, religion

- Family

- Education/Work

How long have you been staying here?

Could you describe what happened to you?

How long were you in the hospital?

How long since you were discharged?

Could you describe the problems you faced at discharge?

What are the medicines or treatments you are taking right now?

- drugs, medical treatments, hospital, doctor visits, follow-ups

Could tell me where you are going to seek the above treatments?

- -Hospital (private/public), clinic, family or neighbourhood doctor

Could you tell me why do you seek treatment there?

- -location, costs, better service, etc.

Could you describe the physical problems you face right now?

- disability, movement, pain, sleep, memory, bodily functions (eating, drinking, excretion)

- writing, reading, picking objects

- co-morbidities

B.#Outcomes

1. Social

Since the injury what kind of difficulty do you face in mobility? (capacity)

- walking, sitting, sleeping

What kind of assistance do you require for the above activities? (performance)

- How frequently?

Since the injury what kind of difficulty do you face doing the activities at home? (capacity)

- Getting washed, visiting the toilet, putting on clothes, household chores cooking, etc.

What kind of assistance do you require for these activities? (performance)

- How frequently

Since the injury what kind of difficulty do you face doing activities outside the house? (capacity)

- Shopping

- Travelling

- using services like school, hospitals, religious places

What kind of assistance do you require for these activities? (performance)

- How frequently

How has the injury affected the kind activities and functions are you able to attend?

- Functions, festivals, gatherings, etc.

What is the support that you require from your family, friends and community?

- Primary care giver/s

ix. How do you feel about the support and behavior of your family, friends and community since the injury?

2. Economic

(Direct)

Could you describe the costs due to the injury?

- Ambulance or transport, Hospital treatment, drugs, tests, follow-up (medical)

- changes around the home (wheel chair, changing toilets, etc.), care-takers costs, legal services (non-medical)(Indirect)

How has the injury affected your work/job?

- What are the difficulties faced in performing the work? Assistance required?

- Support from work place

- How long did/will it take for you to get back to your work?

- Could you estimate the costs due to missing work?

- How do you feel that the injury has affected your job-opportunities?

Could you tell me how you were able to meet the expenses due to the injury?

How else has the injury affected you financially?

- Household income

3. General

What are other problems relating to the injury which affect your life currently?

How do you feel your life has changed since the injury? How has the injury affected you overall?

How do you think that the challenges you described because of the injury could be reduced or improved?

Appendix 2: Table with list of codes, categories, sub-themes and themes

Table A1. List of codes, categories, sub-themes and themes.