ABSTRACT

Gender equity is an important element of health promotion and is vital to ensuring that the benefits and burdens of participation in health promotion activities are fairly distributed. Yet, the gendered consequences of participatory interventions are often overlooked. This is particularly relevant for water and sanitation initiatives, given that women are generally responsible for maintaining domestic hygiene and procuring water. This study uses a qualitative approach to assess the gender dynamics of participation in community-led total sanitation (CLTS) activities in Mpwapwa District, Tanzania. We used semi-structured interviews and focus-group discussions to investigate men’s and women’s involvement in health promotion initiatives and their key motivators for and challenges to participation. We interviewed 77 community members from four villages and analysed the responses using qualitative content analysis. The study supports the notion that participation reinforces gender inequity and reproduces gendered norms due to activity-specific participation, women’s passive participation within activities, and their limited opportunities for decision-making. However, there were also indications that participation provided a platform to increase the status of women, prioritise women’s needs and demand a stronger position in decision making within the household and the community. CLTS organisers should, therefore, harness the opportunity to address gender inequalities within the community.

Introduction

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) place a strong emphasis on equitable access to healthcare, to clean water and to adequate sanitation; furthermore, they have identified gender equality as a key issue which needs to be ensured globally (Kayser et al., Citation2019; UN General Assembly, Citation2015). Gender equality has wide-ranging consequences, not only for economic and societal development, but also for health equity and the fair distribution of benefits and burdens relating to healthcare services and resources. Equity is, therefore, seen as a pre-condition for health, and one aim of health promotion is to promote equity on a community, national and global setting (World Health Organization, Citation1986). In order to accelerate the achievement of the SDG’s, gender is often included as a cross-cutting issue in health promotion participatory projects aiming to empower vulnerable sections of society to demand equitable access to health services. Yet, despite the importance of gender equity to the success of health promotion interventions (Judd et al., Citation2020; Prokopy, Citation2004), previous research has concluded that participatory methods may reproduce existing relations of inequality between women and men (Cornwall, Citation2003; Routray et al., Citation2017). Women are often only involved in providing labour during the implementation stage, have little say in decision-making, may not be in a position to represent women’s issues and are ‘volunteered’ by more powerful community members, all of which replicates existing power hierarchies in project activities (Cornwall, Citation2003; Nchanji et al., Citation2021; Vaughan et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, the positive effects of women’s involvement in community actions may be offset against the time demanded of them (Prokopy, Citation2004). There is still limited knowledge of potential negative effects of community participatory approaches in development, as these are not often reported (Brewis et al., Citation2019; Smith et al., Citation2017). The success of a community health initiative relies on the full participation of all sections of society, as doing so leads to improved sustainability, increased utilisation, and a better distribution of benefits and burdens within the community (Suphian & Jani, Citation2021). Many of the studies that assess participation do so in a quantitative way. Doing so, however, fails to assess the impacts of participation, the motivation behind participation and the extent to which participation is meaningful for different individuals and groups.

Community Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) is a self-sustainable, low-cost participatory approach that aims to mobilise communities to eliminate open defecation and improve environmental sanitation. Key CLTS activities are the improvement and construction of latrines, the production of dish racks and hand washing facilities at the household level and changing sanitation behaviour (Kar, Citation2005). The inclusion of women in CLTS is essential, them being generally the main users of water at the household level, and often responsible for family hygiene (Fisher, Citation2006). A gender mainstreaming approach to water and sanitation interventions can draw from women’s contextual knowledge on water and sanitation provision, and address issues of privacy, safety and convenience (Kayser et al., Citation2019; Prokopy, Citation2004). To date, however, there is limited and contradicting information on the gender dynamics of CLTS implementation. While some studies suggesting that gender norms are reinforced by participation in CLTS activities (Routray et al., Citation2017; Tribbe et al., Citation2021), others indicate that women’s empowerment may benefit as a result of CLTS (Prabhakaran et al., Citation2016). There is also evidence that factors relating to gender may impact the success of CLTS actions (Lawrence et al., Citation2016). While scarce, evidence in the African context suggests that there is a focus on equal representation within CLTS committees, but that encouraging both men and women towards meaningful participation is challenging (Adeyeye, Citation2011; Aranda, Citation2016). Studies have also shown that the work burden of implementing change generally falls to women, as it is difficult to motivate men and boys to participate beyond decision making (Cavill, Wamera, et al., Citation2018). There is, however, a limited amount of research specifically focusing on the reasons that determine the gender dynamics of participation in health promotion activities. Furthermore, no research has fully investigated the effects that participation in CLTS activities may have on ambient gender dynamics within a community.

The study presented, was embedded in the Health Promotion and System Strengthening (HPSS), funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation and implemented by the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute. Since 2011, the HPSS project has supported the Government of the United Republic of Tanzania (hereinafter, Tanzania) in its effort to reform the health sector based on the four of the pillars of health system strengthening: health financing, medicines management, health technology management and health promotion (De Savigny & Adam, Citation2009; Swiss, Citation2020). As part of the progress of the health promotion component, the objective of the current study was to assess the gender dynamics of participation in CLTS activities in Mpwapwa District by (i) describing the involvement of women and men in CLTS activities; (ii) exploring the key factors relating to women’s and men’s participation in CLTS; and (iii) identifying the challenges faced by male- and female-headed households in improving hygiene and sanitation.

Materials and methods

Study area

The study took place between April and June 2014 in the Mpwapwa District of Dodoma Region, Tanzania. Mpwapwa District was purposefully selected due to the high level of engagement in community actions for health, implemented by HPSS. Mpwapwa District had at the time an average household size of 4.6 and a sex ratio of 93 males to 100 females. The population was predominantly rural and ∼90% of the inhabitants engaged in agricultural or livestock activities (National Bureau of Statistics. The United Republic of Tanzania, Citation2012). In the district, the population served with clean water within 400 m of their homes had been decreasing from 74% in 2006/2007 to 56% in 2008/2009 according to the National Water Policy (Ministry of Water and Livestock Tanzania, Citation2002).

Study design

A qualitative design including interviews, observations and focus group discussions (FGD) was used to collect, validate and triangulate data. Interviews and FGDs were semi-structured with predefined questions and probes, informed by evidence in the literature and initial exploratory observations. Observations were made to determine gendered work roles and dynamics within the communities. The three main key informant groups interviewed were district level duty-bearers comprising CLTS Facilitators, District Community Development Officers, District Environmental and Sanitation Officers and the District Health Officers, community leaders and community members (both CLTS participants and non-participants). Gender analysis was used to explore relationships within the household and to relate these to relationships at the community, country and international level (March et al., Citation1999). The study protocol and all measurement instruments were approved by the Ethical Committee of Northwest and Central Switzerland (Ethikkommission Nordwest- und Zentralschweiz; EKNZ 2014-140) and the National Institute for Medical Research in Tanzania. Regulations concerning informed consent and data protection were strictly observed and all participants signed an informed consent form. The study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki.

Location sampling

Four communities were selected to compare between HPSS-supported CLTS initiatives with differing levels of progress in the early stages of implementation. Criterion-based purposive sampling was used to identify suitable communities. Monitoring data were available for only 16 of the 23 villages engaged in health promotion activities due to the failure of some villages to fully follow the monitoring protocol. These data were used in order to identify the four best-performing and the four worst-performing villages measured by CLTS indicators. The indicators were collected before and after CLTS implementation and included (i) the number of households without a latrine; (ii) the number of households with a temporary, basic or improved latrine; (iii) the number of households that practice regular hand washing; and (iv) the number of households that had installed a dish drying rack. The per cent change in households without latrines in each village was calculated. The four villages with the biggest and smallest decrease in households without a latrine were selected as the best and poorest performing villages, respectively. Two high performing villages, ‘Ilolo’ and ‘Luhundwa’ and two low performing villages ‘Igoji 1’ and ‘Kiegea’ were then randomly sampled for study participants.

Participant sampling

Purposeful sampling was used to identify information-rich informants and participant identification was led by individuals within the local administration. The first target group of key informants at the district level was identified by HPSS district coordinators. The key informants at district level were CLTS Facilitators, District Community Development Officers, District Environmental and Sanitation Officers and the District Health Officers. The second target group of key informants at the community level were community health workers and community leaders in the selected villages. The third target group were community members who had attended at least one village meeting concerning either CLTS or health issues identification. Maximum variation purposive sampling was used aiming to capture and describe the main themes in the community. The sampling strategy for CLTS participants and non-participants aimed to recruit individuals using the following criteria (i) individuals of different status at different stages in the life course; (ii) individuals from female-headed households; (iii) individuals from male-headed households; (iv) divorced, separated, unmarried individuals; and (v) widowers/widows. For the FGD groups, we purposively selected different groups from within the communities in order to represent different views in peer groups comprising one mixed group; one group of older women; one of younger women; and one of men to enable communication and the representation of different voices. The composition of the groups, however, depended on the motivation of individuals within each community to participate.

Data collection and analysis

Interviews and FGDs were used to map the division of labour within the community initiative, household and community level gender roles and norms, time demands of the project, determinants of participation in the project, the evolution of gender roles and dynamics over time and evidence of gender-based violence or tensions (see Table S1 for questionnaire). The interview guide was piloted in a village within the Dodoma region. Questions and probes were then discussed and updated. If context-specific topics were found within separate villages, probes were adapted accordingly. Probes were also adapted if new information or themes were discovered. The interview guide was prepared with semi-structured questions and probe prompts. The interview guide for district-level informants was used to give us insights into the CLTS activities and provide use with information in order to inform our interviews at the community-level and triangulate results. The discussions in the FGDs were guided by images displaying different forms of participation in activities and meetings. FGD participants were then asked to describe how they interpreted the images and whether these images reflected the situation in their community. FGDs specifically focused on ambient gender dynamics, rather than on the specifics of involvement in CLTS activities.

Throughout the testing phase, questions and probes were translated from English to Swahili and then back again, to ensure correct meaning. Data were collected by the principal investigator (HT), with the support of a local assistant to provide translation and cultural information. The FDGs were facilitated by the Tanzanian research assistant and efforts were made to encourage participation from all respondents. Interviews were conducted in the homes of the respondents and privacy was ensured by conducting interviews in a room or space away from other family members or neighbours. Interviews and FGDs lasted between 30 and 90 min, and the data obtained was translated verbatim and reviewed to clarify any misunderstandings and gaps. Observations were simultaneously paper-documented by HT and the assistant. At the completion of interviews and FGDs in each village, data were entered into Atlas ti (ATLAS.ti. Version 7.1.8, Berlin, Scientific Software Development). Demographic information on the respondents’ data was entered into Excel for later use in STATA (StataCorp. 2011. Release 12. TX: StataCorp LP). Analysis of qualitative data was guided by qualitative content analysis (Mayring, Citation2015). Analysis of community-level and FGD transcripts followed the procedure set out in Figure S1, and content of district-level interview transcripts and FGD transcripts was used to provide background information and validate results. The majority of data on which this article is based are taken from the analysis of interview data. The whole process was iterative with repeated movement back and forth between raw data (narrative text), codes, categories, themes and plausible explanations that emerged using Atlas ti software.

Results

The study included 82 individual interviews (5 with district-level representatives, 21 with community leaders and 56 with community members) and 11 FGDs, assessing information from 134 participants. gives an overview of the demographic data of the 77 interviewees from the community level (community leaders and community members) consisting of 52% female and 48% male participants. On average, participants were 42 years old and had four children. Most participants had attended primary school (69%) and lived in a male-headed household (65%).

Table 1. Demographic data of the 77 interviewees from the study community.

Gender and involvement in community-led total sanitation

Of the 77 respondents, all but one stated that men in the household, male relatives or male workers were responsible for construction of the sanitation facilities identified in the CLTS process. Women and children were often responsible for fulfilling roles such as farming, which men could no longer take on due to their construction activities, or assisted in construction by carrying water, sand and bricks. A young man commented on the involvement of women and men:

… Overall women have more work than men to build a toilet. When I look at the women, they make bricks, put mud [on the wall], fetch greens, cook for children, and all the time the women have a child on their back. This isn’t fair. The men only build. Most of the time the women accept it because they think it is their role to have a lot of work. (Male, 40, Luhundwa, married, 3 children, interview)

Men were predominantly responsible for financing domestic latrine upgrades and newbuilds. Financing of sanitation amenities caused conflict within some households, as women were generally the drivers of development activities, but men held control over financial decisions.

Intergender tension/cooperation

Although traditional gender roles were often reaffirmed through men and women’s participation in construction, gender roles were also challenged in some circumstances, particularly in households headed by younger people with a higher education level, and opportunities for male and female cooperation were observed, for example when constructing together, as described by a young woman in the following quote:

Now people cooperate together to build a toilet. It increases cooperation and happiness within the family. Even the children used to go to the bushes … now the children know they should use a toilet. (Female, 29, Igoji, married, 1 child, interview)

Some of them (men) are like terrorists, they don’t talk to them (their wives) they just demand bricks. (Female, 20, Ilolo, unmarried, no children, interview)

Participation in public meetings concerning hygiene and sanitation

Fewer female respondents had attended a CLTS meeting compared to male respondents and those with no education were less likely to attend a meeting compared to those with primary or secondary education. Generally, respondents felt able to attend meetings and that their presence in meetings was accepted by the community. Some older women however did not feel that their attendance was valued. As one 77-year-old woman commented:

In the past they listened to me but now they say I have an old view … I feel bad about this. That’s why I don’t attend meetings. Old women are not listened to in the meetings. When I have an idea I just leave it, I don’t pass the information on. (Female, 77, Igoji, widower, 3 children, interview)

Mfumo dume: patriarchy

There were three common responses to the question of why women felt they were unable to voice their opinions within a public meeting. Firstly, the patriarchal system ensures that women are disempowered and gives them a position of lower power and status, secondly their personal fear of speaking in public or shyness, and thirdly the reaction of other women and men. Some men vocally abused women when they spoke in public, and some women regarded women vocalising opinions in public to be ‘masculine’; this was less so for women with a secondary education than those without. The recurrent use of the term ‘Mfumo dume’ (male-dominated system) among respondents suggested that patriarchy is an endemic concept within the community, although men and women conceptualise it differently. For men, patriarchy is seen as a given feature of society, while women identify it as a social problem linked to feelings of exclusion and discrimination as expressed in interviews.

Womens’ participation in meetings

There were three key themes relating to male perceptions of why women attend community meetings such as those held for CLTS: (i) the notion that sanitation and hygiene is a women’s domain; (ii) the concept of women representing their husbands or husbands ordering their wives to attend meetings; and (iii) the concept of women’s innate curiosity and interest in development issues. The following quote shows how men expected women to represent them in meetings:

Most of the time in the meeting it is nature that women attend the meeting. In the afternoon the men go to the Pombe (local beer) shop. Men tell them to attend because they are drunk. The women are curious. Most of the time the women are interested in the meeting, they can pass the information on to the men who will then decide. (Male, 38, Igoji, married, 6 children, interview)

Women as agents of change

One pervasive theme throughout the study was the active role women played in initiating community action. Key informants at the district and village level stated that, in development activities at the community level, women were often the first to show interest and an intention to act. This was reported to have led to conflict in some household where women seek to drive change, while men have control over finances and decisions. As one 45-year-old woman commented:

Women have pressure to implement because if they don’t it affects the children and grandchildren. It causes conflicts between couples. Men are saying women have ambitions. (Female, Luhundwa, 45, married, 2 children, interview)

Key factors relating to women’s and men’s participation in CLTS

Intrinsic factors

Women placed importance on intrinsic factors such as shame, disgust, privacy, responsibility for care giving and hygiene within the household, while men gave more importance to extrinsic factors such as prestige, social status and law enforcement. A third of all women mentioned the health of their children as their main motivating factor for participating in the HPSS-supported CLTS initiatives, as illustrated by the following quote:

The mother is responsible, even if the woman knows why the men should help. She does it because she knows the importance of the health of the children. She is the one who has to take care of the sick children. (Female, Iwondo, 75, married, 5 children, interview)

Extrinsic factors

When discussing motivating factors in the community as a whole rather than their own personal motivating factors, women stated that the community is responding to the CLTS action initiative due to (i) Local bylaws and the threat of fine enforcement; (ii) the cleanliness of the environment; and (iii) lack of private space. Ensuring privacy was stated as being culturally important for women. The main reason men gave for participating in CLTS action was the clearing of the environment for harvest and the construction of more houses, resulting in fewer sheltered places for open defecation, as shown in the following quote:

Before we went to the bushes, at that time we didn’t see the importance of toilets. Now the place is very open and we can see the importance. People try to clear the farms, people are moving and constructing new houses, the bushes are getting fewer. (Male, 90, Iwondo, married, 4 children, interview)

Challenges faced by heads of household to achieving hygiene and sanitation goals

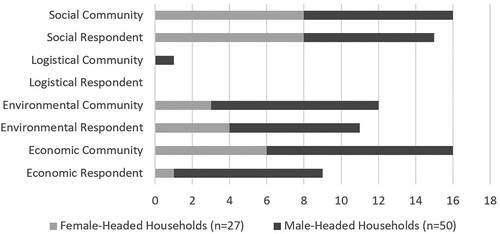

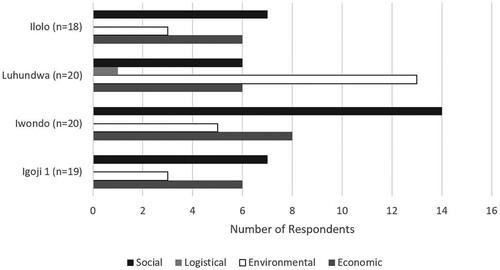

Assessment of the self-perceived barriers to completing CLTS related actions, revealed four main themes, i.e. social, economic, environmental and logistic (). Within those themes, two sub-themes were identified, i.e. barriers relating to the respondent themselves or barriers relating to the community in general. There were also geographical determined barriers, e.g. Luhundwa particularly prone to flooding () was facing a repeating cycle of latrine destruction due to flooding, poor soil quality and lack of availability of materials owing to its remote location, as expressed by one of the men:

… after the rain all the toilets were destroyed, this is something that happens every year. It would help to build these improved toilets. Where I live, the soil is not good for building. A neighbour built one and it was taken by the flood. (Male, 33, Luhundwa, married, no children, interview)

Figure 1. Barriers to completing community-led total sanitation activities reported by female and male informants.

Figure 2. Barriers to implementation of community-led total sanitation actions in different study villages.

I know of people who paid somebody to build their toilet. They wouldn’t have been able to do this work by themselves, they wouldn’t have been able to dig the hole. I don’t have any children to help me … I would have to pay somebody too. (Female, 45, Luhundwa, divorced, 3 children, interview)

People have the resources, if they don’t have money they can exchange food or pombe (local beer) for construction. There are many different ways of being able to build. People are just lazy (wavivu). (Female, 60, Iwondo, married, 6 children, interview)

Collective action in the community to achieve CLTS aims

Only three of the 77 respondents reported voluntarily providing time or resources, non-reciprocally to assist a non-relative in the community to construct or improve domestic latrines. This aspect of collective CLTS action was perceived as inappropriate by the community because they took place within the personal sphere of the home. In contrast, a relatively large proportion of respondents shared a latrine, mostly with family members of different households, so that they could overcome issues such as land scarcity, lack of materials and lack of workforce. Conflicts were reported to arise from these circumstances due to issues with sharing fairly cleaning responsibilities and the perceived increased threat of disease. Also, those choosing to construct new latrines or improve existing latrines were attaching locked doors to discourage their use by neighbours, thereby prohibiting any shared use.

Ambient gender dynamics

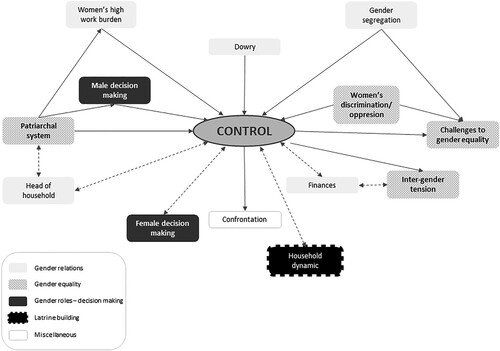

At the community level, the ambient gender dynamics of the study villages did not seem to influence the objective CLTS performance, which was largely dependent on access to resources and environmental conditions. However, at the household level, gender dynamics influenced the extent to which CLTS activities were taken and how successful these were. Gender dynamics were particularly influenced by the decision-making structure, work burden distribution and the influence of the patriarchal system including dowry payments. illustrates the intersections of control in issues surrounding gender equality in the context of CLTS activities. As can be seen from the multiple interconnections, control is a central issue in shaping gender dynamics within the four selected study villages. Control exerts itself in decision-making ability and in work burden, and is associated with discrimination, segregation and inter-gender tension. It is shaped by traditional practices and systems, such as the paying of dowry and the patriarchal system, as men as one man commented:

The woman is paying her price in labour once they are married … we don’t help because we pay dowry so we are not supposed to help with women’s work. (Male, 28 years, FGD)

Figure 3. Control as a central concept in explaining gender dynamics in the four selected study villages. The figure shows the interconnections between different codes used in the data analysis. The shading of the codes shown in the diagram relates to the higher order codes of gender relations, gender equality, gender roles, latrine building and miscellaneous shown in the key. The connections between the codes were created as the codes were commonly used together on specific quotes.

Discussion

Using a qualitative approach, this study provides insights into how involvement in community action for health, within the frame of CLTS is shaped by gender dynamics, in Dodoma, Tanzania. The study provides evidence that participation in community water and sanitation health promotion activities may reinforce gender inequities and reproduce gendered norms. Gendered norms are reproduced by activity-specific participation, women’s passive participation in community meetings and women’s limited decision-making opportunities. In contrast, findings also suggest that participatory health promotion activities may provide a platform to increase the status of women and women’s needs within the community. Furthermore, the active participation of both genders enabled women and men to work together in some settings, and for some women to demand more in terms of participation in decision making within the household and the community.

Our study found that the involvement of women and men in CLTS predominantly followed traditional gender lines. Men led in construction and actively participated in community meetings. They also held power over household sanitation decisions, for example, whether a domestic latrine should be constructed or an existing one be improved. This is common in other low- and middle-income settings (Adeyeye, Citation2011; Cavill, Mott, et al., Citation2018; Kilsby, Citation2012; Masanyiwa et al., Citation2014) and can reinforce gendered labour divisions. By involving men and boys more in all areas of participative water and sanitation programmes, including those traditionally held by women, the burden and benefits would be better distributed in communities, and labour burdens would not only fall to women (Cavill, Wamera, et al., Citation2018). Men and boys heightened involvement in sanitation and hygiene issues would also potentially have knock-on effects within households and go some way to transforming ambient gender norms (Cavill, Mott, et al., Citation2018; Cavill, Wamera, et al., Citation2018).

In community meetings, we saw a great disparity between the contributions of women and those of men. Numerically, both were equally present but in terms of influence and power, men had much more precedence. Men reported that women were often obliged to attend to act as representatives of their husbands, reflecting the male perception that women were passive agent. The findings in our study are in line with those from another study from the same region of Mpwapwa in Tanzania (Masanyiwa et al., Citation2014). This study also found that women who did contribute in meetings were often considered to be ‘gender-neutral’, i.e. those that are older, married and with grandchildren. Masanyiwa et al. also found there to be several perceived constraints to women’s effective participation in public discussions and decision-making processes, including the patriarchal system, household responsibilities of women and the personal qualities of women (Masanyiwa et al., Citation2014; Prokopy, Citation2004, Citation2005). Water and sanitation committees may offer a concept to counteract those practices and increase community involvement and ownership. They may furthermore encourage and foster women’s participation. Women-only sub-committees might act as a platform for women to gain confidence in speaking out and to learn vital skills needed for bargaining and negotiating in the public sphere (Ziaey, Citation2021).

In Tanzania, the Prime Minister’s Office recognises women as ‘potential drivers of change’ (Masanyiwa et al., Citation2014). In our study, however, women were found to be drivers of change at the household rather than the community level, placing pressure on male decision-makers in order to commence and complete CLTS implementation. The negotiating and bargaining skills acquired when convincing others in the household to act on hygiene and sanitation matters, may be used to negotiate in other household matters. Women’s participation is often treated as synonymous with empowerment (Cornwall, Citation2003). There are several findings in our study which point towards an increase in female empowerment, such as a greater involvement in decisions regarding hygiene and sanitation, and the increase in status and importance of themes within the women’s domain. These findings are similar to those of other studies conducted in India and Bangladesh in the early 2000s (Mahbub, Citation2008; Prokopy, Citation2004).

In terms of factors motivating women to participate and take action for health, we found intrinsic factors, such as the perceived responsibility for family health and notions of privacy and shame to be the most important. This corresponds with findings in other studies whereby the feminisation of health, water and social welfare were seen to be drivers of women’s involvement in health promotion initiatives addressing hygiene and sanitation (Masanyiwa et al., Citation2014). Mahbub also found in Bangladesh that women were motivated by shame, the preservation of self-dignity and feelings of disgrace of defecating in public (Mahbub, Citation2008). Men, on the other hand, were motivated more by external factors, such as the threat of being fined, highlighting the contrasting perspectives of men and women (Pandey & Moffatt, Citation2020).

Another main trend observed was the lack of community support for older women living alone, highlighting a lack of the intended collective action of CLTS in this setting. Elderly or vulnerable persons in Tanzania are culturally perceived to be the responsibility of the family; when this resource is not available, individuals need to find a way to be self-sufficient, as help from outside the kin network is not generally offered (Obrist & van Eeuwijk, Citation2014). Globally, female-headed households are particularly affected by lack of support as they have smaller kin and social networks, exacerbating the problem of a limited workforce for physical labour within the household (Chant, Citation2004). Although lack of physical labour was a primary concern among female-headed households, there were also issues relating to lack of construction knowledge reported among women in both female- and male-headed households. By increasing access to construction knowledge or by providing financial assistance, women may be enabled to complete CLTS actions in the absence of male relatives.

Informants from male-headed households reported being more restricted by the lack of funds to purchase materials for the construction of improved latrines than by the lack of physical labour. The whole CLTS concept, however, revolves around communities’ abilities to innovate novel solutions to resolve open defecation problems without subsidisation of materials (Kar, Citation2005). This does not necessarily require expensive materials, but requires that the community are inventive with local materials. By focusing more on the eradication of open defecation rather than the construction of improved latrines with a prescribed design, there may be more scope for community innovation and ownership (Crocker et al., Citation2017; Noy & Kelly, Citation2009) (Tribbe et al., Citation2021).

The classic identifiers of patriarchy were reported to be a cause of gender inequality and women’s subordination in our study. Women’s lack of control over resources and decision-making, women’s higher work burden and the unbalanced division of labour, were found to have particularly negative consequences on gender equality. Cultural practices such as the payment of dowry and the pervasive cultural norms prescribed by the patriarchal system put women at a lower position in society and within the household. The act of paying dowry before marriage was reported, especially by men in our study, to form in part the hierarchy experienced in the patriarchal system, but the continuation of the dowry ritual was never questioned by them. Ambient gender dynamics, therefore, had an influence on men’s and women’s involvement in CLTS activities, while involvement in CLTS activities had an influence on ambient gender dynamics. Masanyiwa et al. explored this issue in central Tanzania and found that it was highly interconnected with peer pressure between young men (Masanyiwa et al., Citation2014). Our study also showed women to be more willing to assume traditionally male roles in comparison to men taking on female roles. Women may be increasingly able to take on new roles but they struggle to share existing responsibilities, which is increasing their work burden and expanding the ‘feminisation of responsibility’ (Chant, Citation2006; Routray et al., Citation2017).

Limitations and strengths

There are several limitations to our study which may have led to bias. The translation of interview data by the research assistant in real-time during the interviews may have limited the quality of the transcription script, owing to the time pressure. The recruitment of participations was undertaken by individuals in the village administration which may have led to selection bias. There were no data collected on individuals who did not want to participate which may lead to non-response bias. The principal investigator and both research assistants were female; this was purposively decided upon due to the sensitive nature of some issues. However, in doing this, the responses from male informants may be inaccurate or biased towards a more socially acceptable form. This may have been particularly so, as the research team were from outside of the community and the principal investigator was foreign. Our status as outsiders may also have influenced responses if informants perceived us to have control or influence over incoming resources linked to the initiative.

These limitations are balanced by several strengths such as the high number of interviews, the elaborated sampling strategy, the extensive participant observation allowing to establish the interview questionnaire and the fact that all interviews were carried out by the principal investigator (HT) and a research assistant.

Conclusion

The gender dynamics in the study villages had an impact on women and men’s participation in community actions of the CLTS initiative. Activity-specific participation, women’s passive participation in the community setting, and their limited decision-making opportunities at times reinforced and reproduced traditional gender norms. However, participation in CLTS activities, set in the context of the traditionally ‘female’ domain of water and sanitation, has provided the opportunity for the HPSS project’s participatory health promotion approaches to have a positive influence on gender dynamics. The focus of water and sanitation has increased the status of women and women’s needs within the community. Furthermore, the active participation of both genders enabled women and men to work together in some settings, and for certain women to assume more control within the household and the community. CLTS activities should, therefore, harness the opportunity to address gender inequalities within the communities where they take place, and encourage active participation from both men and women in all CLTS activities.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (37.2 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (27.4 KB)Acknowledgements

Firstly, the authors would like to thank of all the participants of the study for their time and generosity. We would like to acknowledge the assistance of the Health Promotion and Systems Strengthening (HPSS) team; Manfred Stoermer, Prof Manoris Meshack, and other team members. We would like to thank Dr Jasmina Saric, for her critical review of the paper as well as Dr Leah Bohle for her assistance in designing the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adeyeye, A. (2011). Gender and community-led total sanitation: A case study of Ekiti State, Nigeria. Tropical Resources: Bulletin of the Yale Tropical Resources Institute, 30, 18–27.

- Aranda, S. N. (2016). Role of gender on community led total sanitation processes in Kanyingombe community health unit, rongo sub County, Kenya [Dissertation, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology].

- Brewis, A., Wutich, A., du Bray, M. V., Maupin, J., Schuster, R. C., & Gervais, M. M. (2019). Community hygiene norm violators are consistently stigmatized: Evidence from four global sites and implications for sanitation interventions. Social Science & Medicine, 220, 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.10.020

- Cavill, S., Mott, J., Tyndale-Biscoe, P., Bond, M., Edström, J., Huggett, C., & Wamera, E. (2018). Men and boys in sanitation and hygiene: A desk-based review (report no. 1781184879). Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex.

- Cavill, S., Wamera, E., Jimmy, M. K., & Yondu, S. (2018). Involving men and boys in CLTS: East and Southern Africa region. Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex.

- Chant, S. (2004). Dangerous equations? How female-headed households became the poorest of the poor: Causes, consequences and cautions. IDS Bulletin, 35(4), 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2004.tb00151.x

- Chant, S. (2006). Re-thinking the “feminization of poverty” in relation to aggregate gender indices. Journal of Human Development, 7(2), 201–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649880600768538

- Cornwall, A. (2003). Whose voices? Whose choices? Reflections on gender and participatory development. World Development, 31(8), 1325–1342. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(03)00086-X

- Crocker, J., Saywell, D., & Bartram, J. (2017). Sustainability of community-led total sanitation outcomes: Evidence from Ethiopia and Ghana. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 220(3), 551–557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2017.02.011

- De Savigny, D., & Adam, T. (2009). Systems thinking for health systems strengthening. World Health Organization.

- Fisher, J. (2006). For her it’s the big issue: Putting women at the centre of water supply, sanitation and hygiene. Evidence Report, Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council.

- Judd, J. A., Griffiths, K., Bainbridge, R., Ireland, S., & Fredericks, B. (2020). Equity, gender and health: A cross road for health promotion. Health Promotion Journal of Australia. 33(3), 336–339. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpja.422

- Kar, K. (2005). Practical guide to triggering community-led total sanitation (CLTS). Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex.

- Kayser, G. L., Rao, N., Jose, R., & Raj, A. (2019). Water, sanitation and hygiene: Measuring gender equality and empowerment. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 97(6), 438. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.18.223305

- Kilsby, D. (2012). Now we feel like respected adults’: Positive change in gender roles and relations in a Timor-Leste WASH program, research conducted by International Women’s Development Agency. WaterAid Australia, Melbourne and WaterAid Timor-Leste, Dili.

- Lawrence, J. J., Yeboah-Antwi, K., Biemba, G., Ram, P. K., Osbert, N., Sabin, L. L., & Hamer, D. H. (2016). Beliefs, behaviors, and perceptions of community-led total sanitation and their relation to improved sanitation in rural Zambia. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 94(3), 553. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.15-0335

- Mahbub, A. (2008). Social dynamics of CLTS: Inclusion of children, women and vulnerable persons. CLTS Conference (pp. 16–18).

- March, C., Smyth, I. A., & Mukhopadhyay, M. (1999). A guide to gender-analysis frameworks. Oxfam.

- Masanyiwa, Z. S., Niehof, A., & Termeer, C. (2014). Gender perspectives on decentralisation and service users’ participation in rural Tanzania. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 52(1), 95–122. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X13000815

- Mayring, P. (2015). Qualitative inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und techniken. Beltz.

- Ministry of Water and Livestock Tanzania. (2002). National water policy.

- National Bureau of Statistics, The United Republic of Tanzania. (2012). The United Republic of Tanzania: 2012 population and housing census. http://www.nbs.go.tz/sensa/new.html

- Nchanji, Y. K., Ramcilovic-Suominen, S., & Kotilainen, J. (2021). Power imbalances, social inequalities and gender roles as barriers to true participation in national park management: The case of Korup National Park, Cameroon. Forest Policy and Economics, 130, 102527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2021.102527

- Noy, E., & Kelly, M. (2009). CLTS: lessons learnt from a pilot project in Timor Leste. 34th WEDC International Conference, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Obrist, B., & van Eeuwijk, P. (2014). Ageing: A new health challenge in Indonesia and Tanzania. EPH Seminar, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute.

- Pandey, U., & Moffatt, M. (2020). Gender and poverty approach in practice: Lessons learned in Nepal. In A. Coles, & T. Wallace (Eds.), Gender, water and development (pp. 189–207). Routledge.

- Prabhakaran, P., Kar, K., Mehta, L., & Chowdhury, S. R. (2016). Impact of community-led total sanitation on women’s health in urban slums: a case study from Kalyani municipality. IDS Evidence Report No 194: Empowerment of Women and Girls. Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex.

- Prokopy, L. S. (2004). Women’s participation in rural water supply projects in India: Is it moving beyond tokenism and does it matter? Water Policy, 6(2), 103. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2004.0007

- Prokopy, L. S. (2005). The relationship between participation and project outcomes: Evidence from rural water supply projects in India. World Development, 33(11), 1801–1819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.07.002

- Routray, P., Torondel, B., Jenkins, M. W., Clasen, T., & Schmidt, W.-P. (2017). Processes and challenges of community mobilisation for latrine promotion under Nirmal Bharat Abhiyan in rural Odisha, India. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4382-9

- Smith, H., Portela, A., & Marston, C. (2017). Improving implementation of health promotion interventions for maternal and newborn health. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1450-1

- Suphian, R., & Jani, D. (2021). Local participation and satisfaction with developmental projects: Segmentation of Saemaeul Undong participants in Tanzania. Tanzania Journal of Development Studies, 18(1), 105–115.

- Swiss, T. P. H. (2020). Swiss-Tanzania cooperation: Health Promotion and System Strengthening Project (HPSS). https://issuu.com/communications.swisstph/docs/hpss_brochure

- Tribbe, J., Zuin, V., Delaire, C., Khush, R., & Peletz, R. (2021). How do rural communities sustain sanitation gains? Qualitative comparative analyses of community-led approaches in Cambodia and Ghana. Sustainability, 13(10), 5440. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105440

- United Nations General Assembly. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. United Nations.

- Vaughan, C., Gill-Atkinson, L., Devine, A., Zayas, J., Ignacio, R., Garcia, J., & Marco, M. J. (2020). Enabling action: Reflections upon inclusive participatory research on health with women with disabilities in the Philippines. American Journal of Community Psychology, 66(3-4), 370–380. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12468

- World Health Organization. (1986). Ottawa charter for health promotion. Health and welfare Canada. Canadian Public Health Association.

- Ziaey, A. J. (2021). Applying community-driven approaches to rural development and women’s empowerment in Afghanistan. Political Science Policy Perspectives. 1–15. https://doi.org/10.4079/PP.V28I0.9