ABSTRACT

An expansive view of ‘rigorous’ research is needed, particularly when studying complex health and human rights issues in settings where the imbalance of power between research participants, users and producers is heightened. This article examines how applying participatory, feminist and anthropological methods in gender-based violence research can hold researchers accountable to both acknowledging and explicitly addressing these power disparities. Applying these approaches throughout the research process takes time – to build trust and share stories rather than ‘extract’ data, to engage in collective meaning-making with those whose lived experiences are a form of expertise, and to consider how knowledge is represented and with whom it is shared. We provide examples and reflections from Empowered Aid, participatory action research that examines sexual exploitation and abuse in relation to humanitarian aid distributions, and tests ways for making aid safer. The study is grounded in ethnographic research by Syrian and South Sudanese women and girls living as refugees in Lebanon and Uganda, to safely take an active role in asking and answering questions about their own lives.

Introduction

Research methods have been ‘reimagined’ for use in humanitarian settings, adapted from other fields like medicine and behavioural science. When applied to the study of complex health and human rights issues in settings affected by conflict or natural disaster, the imbalance of power between research participants, users and producers is heightened. These existing inequalities can potentially be acted upon by the research process itself, if a view of ‘rigorous’ research is taken in which power is continually discussed, questioned and challenged. Applying participatory, feminist and anthropological methods in gender-based violence (GBV) research can support efforts to decolonise knowledge production by holding researchers accountable to both acknowledging and explicitly addressing power disparities (Bradshaw et al., Citation2016; Chadwick, Citation2021; Singh et al., Citation2021). While not a panacea, in humanitarian settings much research and programming continue to be conducted without any explicit consideration or discussion of power – let alone engagement of affected people as decision-makers. While researchers and aid workers may imagine that the necessary time and space does not exist for such approaches, the reality of global displacement shows us otherwise: the average time a person spends as a refugee is 10.3 years (Devictor, Citation2019).

Refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) often have less power than those residing in host communities, and lack citizenship rights including the right to work and move freely. They often do not know the local language, have educational certificates that do not transfer, and face limited employment opportunities, even when they legally have the right to work. In addition, in times of crisis, pre-existing power imbalances based on gender and age, as well as other forms of identity, can be exacerbated – while the social mechanisms meant to mitigate abuses of power, such as women's activists and movements, may be compromised or even under attack. Feminist research methods seek to understand women and girls’ lived experiences in their own words, to name and confront power imbalances, and to create or support non-hierarchical relationships between the researcher and those being researched (Davis & Srinivasan, Citation1995; Webb, Citation1993; Wise, Citation1987). Feminist research on gender-based violence often prioritises the perspectives of survivors and affected populations, women's rights activists or organisations, other rights-based movements, and practitioners providing services to survivors.

In addition to considering structural power dynamics in humanitarian settings, researchers should reflect on power in relation to their own position within these structures. This includes their role (humanitarian aid worker, researcher, or donor, for example), country of nationality (often referred to as being ‘local’ or ‘international’), educational background, racial or ethnic identity and other characteristics that can affect their access to and control over resources. Resources may include funding, knowledge, the ability to travel, or the ability to write or speak in English. Many research questions and objectives continue to be generated in Global North universities, with minimal or no input from affected communities, or those working to provide services to them, many of whom are nationals of the host country. As Johanna Kistner, Executive Director of a Sophiatown Community Psychological Services in South Africa, explains within the participatory arts-based and storytelling project Mwangaza Mama:

In our organisation, we have learnt to treat any researcher who approaches us with the request for access to clients with a certain degree of suspicion. In whose interest is the research? Who will benefit from the research? What do the women or children who have come to us for emotional (and often material) support have to gain by participating in a research project, often opening up their wounds for all to see only to be abandoned once questionnaires have been filled out or interviews completed? How many more studies need to be done before anybody anywhere acts on what has already been researched, published and disseminated? (Kistner, Citation2019, p. 17)

Feminist and anthropological research practices emphasise positionality, that one's own relation to the subject (topic) and subjects (people) under study – one's ‘position’ in the social, historical and political world – influences one's assumptions about what can be known and how knowledge is acquired (England, Citation1994; Holmes, Citation2020). Engaged activist practice also centres these values, for example in understanding how different members of a movement may face intersectional barriers or enablers to the ways in which they can take action. Maintaining reflexivity over a research process requires intentionality, in how time is allocated and in the presence staff bring to these processes; particularly those with the most power. Anthropological methods, and specifically ethnography, offer a vehicle for privileging the position of those most marginalised in dominant forms of knowledge generation. Recognising the intertwined history of anthropology and colonialism, researchers have sought to ‘decolonize ethnography’ by using it as a tool for action research, in which those closest to the problem build theory from documenting their experiences (Alonso Bejarano et al., Citation2019).

Participatory action research (PAR) methods directly raise questions around ‘What counts as participation?’ and whose voices matter; they also demand careful, ongoing consideration of ethics, safety and transformative social change. PAR stands apart from conventional research in three important ways: it is primarily action-oriented and based on iterative reflection processes; it calls ‘for power to be deliberately shared between the researcher and the researched: blurring the line between them until the researched become the researchers’; and it maintains a sense of place, with data and information remaining in the context from which it was produced, and active engagement of those normally considered passive ‘respondents’ or ‘subjects’ (Baum et al., Citation2006). Arts-based methods, especially when applied within participatory frameworks, can be tools for those living on the margins to challenge their representation and make themselves visible (Mitchell & Sommer, Citation2016; Oliveira & Vearey, Citation2017; Oliveira & Walker, Citation2019, p. 21). In this article, we draw examples and reflections from feminist, ethnographic, participatory action research examining sexual exploitation and abuse in relation to aid distributions.

Materials and methods

Empowered Aid is multi-year (2018–2021), multi-country participatory action research in Lebanon and Uganda, two of the largest refugee-hosting countries in the world. Syrian and South Sudanese women and girls living as refugees undertake ethnographic research, actively asking and answering questions about their own lives: specifically, how they navigate Global North-led systems for distributing aid. Uganda hosts almost 1.5 million refugees and asylum seekers, mostly fleeing ongoing crises in South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Burundi and Somalia. Lebanon also hosts 1.5 million Syrian people fleeing their country's civil war; this means almost one in every four people living there is a refugee. Both countries have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and Lebanon faces intersecting economic and political crises.

The research engaged 29 South Sudanese women and girls living as refugees in rural settlements (Bidi Bidi and Imvepi) in northern Uganda, and 26 Syrian women and girls living as refugees in urban and peri-urban areas of Tripoli, in northern Lebanon. In the first phase, refugee researchers selected the types of aid to be studied and undertook participatory training in ethnographic methods, to systematically observe SEA risks related to aid distributions in the areas where they live. As participant-observers, they used oral, visual and other creative methods to document the risks related to sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) that they and their peers face when seeking access to food; shelter; water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH); fuel and firewood; and cash and voucher assistance. Their observations were shared back through semi-structured, participatory focus group discussions and in-depth, semi-structured interviews held every two weeks over a four-month period. Participatory group discussions were also held with refugee men and boys; women, girls, men and boys from the host community; and persons living with disabilities; and key informant interviews were conducted with stakeholders from community leadership structures and humanitarian personnel. In total, 127 people were engaged in Uganda and 70 in Lebanon. Of the core group of 55 refugee researchers, 13% (4 women and 3 girls) identified as having a disability. In total, 203 interviews and 22 participatory group discussions (PGDs) were held with the core group of refugee researcher, as well as 25 community PGDs with other community groups, and 28 key informant interviews.

The research was conducted by the Global Women's Institute (GWI) at the George Washington University, based in the United States, in partnership with local and international refugee-serving organisations the Union of Relief and Development Associations (URDA), a woman-led Lebanese NGO; CARE International in Lebanon; and the International Rescue Committee and World Vision in Uganda. Rather than ‘capacity-building’, a ‘capacity-sharing’ approach was applied in which each partner's expertise was recognised as contributing to areas in which other partners have less knowledge or experience. National research leads were themselves women from the countries under study, embedded within the NGO partners to increase uptake and use of feminist, participatory methods within aid structures. Their recruitment emphasised experience as service providers and women's rights activists over academic credentials, to address structural barriers that often keep people from crisis-affected countries, and particularly women, out of research leadership roles. GWI provided a series of trainings on safe, ethical GBV research in humanitarian settings to demystify the research process and increase non-academic research team members comfort to question or challenge research processes introduced by academics. The Global South research managers shared their contextual experience and expertise built over years of working to support refugee populations and GBV survivors within their regions. Sharing of these capacities contributed to balancing power and collective decision-making, both central to feminist practice in GBV research collaborations (Raising Voices and SVRI, Citation2020).

Participatory, visual methods were used throughout study design, analysis and synthesis processes to increase participation among the refugee women and girls involved, and ensure multi-directional pathways for learning and knowledge production. As Walker and Oliveira write, ‘When used ethically and responsibly, arts-based research approaches “can facilitate empathetic responses and horizontal channels of learning, both of which are critical to dismantling oppression and advancing social justice”’ (Oliveira, Citation2019, p. 537; as cited in Walker & Oliveira, Citation2020). In the second phase (implementation science), the recommendations put forward by refugee women and girls were applied to aid distributions alongside monitoring tools adapted to better measure safety in relation to the SEA risks they identified. In this way, the systems they must negotiate to access food, water, shelter and other forms of aid are more fit-for-purpose to proactively reduce SEA, and include those most affected in how the systems that affect them are designed and monitored. The George Washington University Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviewed and approved the research protocol for each phase (#NCR191076, NCR191930), including procedures for obtaining informed consent from all research participants.

In both Lebanon and Uganda, SEA was reported as occurring across all types of aid explored, in all stages of the distribution cycle – from communicating and receiving information; to registering or being verified for aid; at the distribution site; travelling to and transporting aid from these sites; and safely storing aid. In addition, women and girls reported multiple barriers to reporting cases of SEA, including lack of knowledge or faith in reporting mechanisms, stigma and other negative repercussions from community and family members, and the normalisation of SEA meaning that for many, they and their families and communities see it as the cost of receiving life-saving assistance. Further information about the methods and findings will be published elsewhere, and those wishing to read more in the interim may access the results reports and briefs that were developed for humanitarian actors to immediately put Empowered Aid's findings into action.Footnote1

Results

The following are reflections on how participatory, feminist and anthropological methods were applied within this participatory action research, in ways that sought to hold researchers accountable to both acknowledging and explicitly addressing power disparities among the research team as well as the contexts within which the research was taking place.

Intentional, reflexive spaces and processes

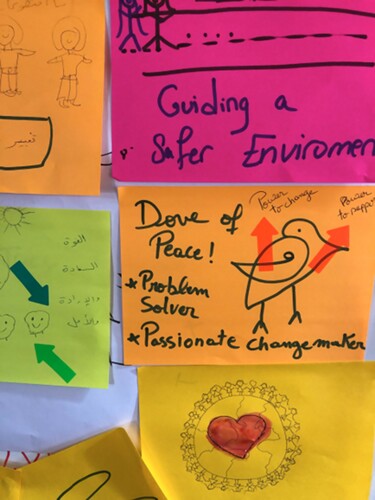

Within Empowered Aid, we began and ended our co-design processes with creative and visual methods for reflective inquiry, such as journaling and visualisation practices. Our first series of participatory action research workshops incorporated interactive exercises about power drawn from Raising Voices SASA! Training Package (SASA!, Citationn.d.; The Global Women’s Institute, Citation2020b). Visualisation exercises at the end of each workshop centred on questions such as, ‘What is my vision for the impact that Empowered Aid can have, alongside my other work to address SEA? How do I see my role in this impact?’ shows how words and images were used to communicate refugee researchers’ motivations and aspirations for participating, including improving their environment and uniting with others to take action in repairing the harms of abuse; drawn as a circle of people around a heart, against a fragmented background.

Figure 1. Participants from the participatory action research workshop conducted in Lebanon used words and pictures to communicate their vision for the impact of the Empowered aid programme and to magnify their desired role in creating this impact. All photos taken and used with informed consent. Photo by: Alina Potts.

Methods for reflecting on one's power and position within the research team, as well as in relation to the topic under study, were placed throughout data collection. These included the use of field notes, a midpoint ‘pause’ for reflection, and the inclusion of body mapping in the concluding participatory group discussions. Field notes were used by those collecting data in writing, to capture their observations, analysis, relevance and ethical reflections immediately following each interview or participatory group discussion. These were analysed alongside research data, as well as used amongst the research team to provide supportive supervision and reflection as data collection proceeded. The following note is from an interview by one of the NGO team members with a South Sudanese adolescent girl living as a refugee in Uganda: ‘The participant was quite absent minded which made it difficult to probe. The translator was also not fully present in the interview as she mentioned after that her mother was in hospital and that affected her concentration’. Rather than consider this interview ‘not useful’, the field notes supported non-refugee members of the research team to reflect on their power and the need to consistently acknowledge the lived realities facing each person in the room – including translators, whose contribution is not always fully valued and who often come from the communities with whom research is being conducted. Such systematic processes for reflection can help guard against translators and respondents being conceived of, even if not consciously, as ‘objects’ or ‘tools’ of research, by prioritising space to note observations and reflections. It is no small thing to actively ask women and girls how they are doing and what works for them, rather than passively assume that they will have the time and ability to seek out channels for feedback. In field notes from an interview with one of the South Sudanese women living as a refugee in Uganda: ‘At the end of the interview, [she] mentioned that there should be immediate feedback of the information being collected because there are so many women suffering’. Many refugee team members emphasised the importance of findings being immediately used for action, and pointed to frustration with how many of their needs go unmet despite engaging with aid actors and systems.

Halfway through data collection, a series of reflection workshops were held to allow research team members to reflect on their role, and their use of power and privilege, within the research process: as women from Global North countries working at an international research institute; as women from the countries under study working at international or national NGOs; and as refugee women and girls forcibly displaced from neighbouring countries, engaged in the research either directly or through their work as translators with the NGOs. These workshops were first held amongst GWI and NGO team members, to surface issues amongst those holding comparatively more privilege and power, and prepare for co-facilitating such reflective space with the refugee team members (The Global Women’s Institute, Citation2020d).Footnote2 Additional power exercises from Raising Voices’ SASA! Toolkit (SASA!, Citationn.d.), in addition to a power continuum exercise developed specifically for this project, were used to facilitate reflections on one's experiences throughout the research process. In Lebanon, NGO team members noted how, ‘Being Lebanese is a form of power when interviewing refugees’. This was discussed amongst staff as well as in the workshop with Syrian women and girls, who spoke to feeling this power imbalance in some of their interactions, especially in terms of setting the schedule for meetings. Syrian refugee women and girls involved in this discussion later said that the ability to share this feedback in the reflection workshop, and then see it responded to, built their trust and reinforced their openness to the research process as a whole. ‘Mona’,Footnote3 one of the Syrian woman researchers in Lebanon, shared, ‘I was very comfortable, and I felt very strong because the team I was working with created a safe and trusting space to speak about the issues we have all held back’.

As noted above, a less-examined power dynamic that often exists within research teams is between translators and other research staff. In Uganda, translators were from the local refugee communities and often work with NGOs. Many reported the reflection workshop as their first experience being asked what they thought should be done or changed in a project they were working on. One shared, ‘It's not just translating but internalising the problems that women and girls share, we feel them as well because we are part of the refugee community’. Another noted that the pace of the study – its longitudinal qualitative design meant that they met with the refugee women and girl researchers about every two weeks over several months – allowed them to build relationships that improved the quality and ease of their conversations over time. This, as well as being included in design and training processes, was reported as helpful in the other work they do with partner NGOs as translators for case management with GBV survivors.

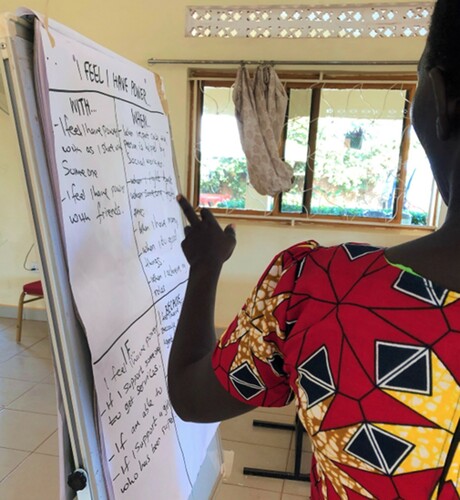

Women and girls in both countries gave examples of times when they felt little power or agency in decisions made. For example, there were times when the logistics of the study, despite being planned with them, failed to meet their needs: such as, ‘confusion around the location of the participatory group discussion training, as it was changed’ and ‘the appointment times [to meet with staff researchers and share what they have observed] change, and it's confusing’. An adolescent girl researcher in Lebanon shared, ‘we’re unsure when is the end of the project, and how it will end’. While the academic and NGO staff felt it had been discussed adequately, her reflection indicated otherwise. It points to the need for ongoing engagement around topics that may still be unresolved or issues of concern; especially among those for whom intersectionality, in this case as a female, adolescent, refugee girl, means they often experience such decisions being made without them or not being communicated to them ().

Figure 2. A South Sudanese adolescent girl living as a refugee in Uganda involved in the research presents her group's discussion on power, during the Research Reflection Workshops in Uganda. All photos taken and used with informed consent. Photo by: Alina Potts.

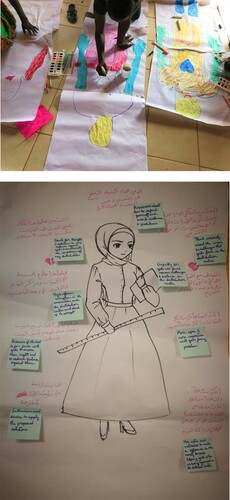

Body mapping is a well-established form of visual storytelling, including in research on health and human rights (Bunn et al., Citation2020; Walker & Oliveira, Citation2020). This method was incorporated in design workshops at the outset of the study (The Global Women’s Institute, Citation2020b), as well as in the closing set of participatory group discussions (The Global Women’s Institute, Citation2020c), with questions about refugee women and girls’ experience of participating in the study. Using large sheets of paper and working in pairs, participants outlined their body and then were asked to think back to their experiences in Empowered Aid activities. Music and lighting were used to create a calm environment supportive of internal reflection. After a few moments, the question was posed:

How has the experience of participating in this research affected you, in terms of your thoughts? Use the art supplies provided to represent this in any way you like – drawings, words, symbols – focusing on the head area of your outline.

Figure 3. Example of body mapping exercise with South Sudanese adolescent girls living as refugees in Uganda, and a body map drawn by a Syrian adolescent girl in Lebanon who preferred to represent herself as an anime-like character. All photos taken and used with informed consent. Photo by: Alina Potts (above) and Loujine Fattal (below).

[Our] legs have taken [us] to places they have not been before.

We also felt happy because some of the questions are about how our mind, how our thinking is.

At the time I felt happy lying [down with] my body because I knew they [the wider team] were going to bring these actions to women and girls.

Participatory, feminist data analysis and synthesis processes

Empowered Aid examines how aid can cause further harm if not delivered safely, including undermining sexual and reproductive health and rights. Participatory action research in particular acknowledges the role of community activism, and refugee women and girls strongly identified this as a motivation for being a researcher. By participating, they felt a sense of ownership in contributing towards safer access to humanitarian aid for all. Amal Koussa, a Syrian woman member of the research team, shared that for her, ‘Through [the research], we tried to help ourselves and other women and girls in the community. We wanted our voices to reach all areas, all humanitarian organisations, and all distribution points’. One of Amal's peer researchers, Lama Sibaii, said, ‘We considered ourselves as the changemakers against the risks faced at distributions’. Among the Syrian adolescent girls involved, Zeina expressed a similar sentiment: ‘My role in this study was to make sure that the voices of all women and girls are heard, so that we can create change’.

In the mid-point reflection workshops with Syrian adolescent girl researchers, one shared, ‘We are happy because we are part of change that can benefit other girls’. Another said that, ‘We are having difficulty because we are confined only to observation without asking’. This highlights the tension between safety and engagement in research on sensitive topics where dominant power structures are challenged. At the design stage, the group agreed that the risks of interviewing others were too great given the potential for retaliation.

Over the course of three months, the Uganda and Lebanese NGO researchers met with the refugee women and girl team members regularly to record their observations around SEA risks associated with a particular type of aid. During this time, the NGO team members testified to a complete shift in their own knowledge and interviewing skills, as well as their commitment towards working to end SEA in humanitarian aid. As one of the NGO social workers who supported data collection shared, during a reflection interview,

… [women and girls] would go and observe what they have experienced for two weeks then we meet with them. They would give us ideas on what they have seen, what they have experienced and ideas on what could be done to solve those issues. The fact is those recommendations came from them, by us implementing their recommendations it will be like we have listened to them and done what they want that can help them to make sure that the aid distribution is safe for them.

The meaning making process is a potent place for sharing power within research. GWI staff trained the national research managers and officers from the countries under study in qualitative data analysis and analytical software packages (Dedoose). Analysis was conducted among the academic and NGO partner staff jointly, including development of the data analysis plan, codebook and coding of all data and field notes (each transcribed data file was coded by at least two people), with weekly meetings to debrief, discuss questions, adapt the codebook as necessary and ensure consistency in how it was applied. An initial set of themes was developed and reflected back to the wider group of NGO research staff, including translators from the refugee communities, in a series of ‘action analysis workshops’ (The Global Women’s Institute, Citation2020a), which were created by the team as a process for making qualitative analysis accessible to all team members, including refugee researchers and NGO team members who were illiterate so could not directly participate in the coding of transcripts. In this series of workshops, the initial themes were collectively developed into visual representations and shared with refugee women and girl team members (see ), who validated the initial themes and expanded upon them using drama, storytelling and visual methods to further organise and prioritise the main findings and recommendations for how to make aid distributions safer. As Angaika Poni, one of the women involved as a refugee researcher in Uganda, shared: ‘I agreed with the findings because they came from our experiences and they allowed us to have more confidence in ourselves’. Another, Mirabel, said:

It was helpful because of the drawings. After they were drawn, we divided into four groups to review them. There were drawings where women would go to fetch firewood in groups. Others were drawings of water tanks, which are next to valleys without light. Others were drawings of constructors and builders who are building houses for persons with special needs in the community. And other drawings were of boda [moto-taxi] men who always take our food to our homes.

Figure 4. Empowered Aid Research Officer Farah Hallak reflects back thematic analyses of findings and recommendations for making aid distributions safer with the Syrian refugee women who generated them, during the Action Analysis Workshop with Refugee Women Researchers in Tripoli, Lebanon. All photos taken and used with informed consent. Photo by: Alina Potts.

The drawings were very good, they reflected everything we discussed to help us understand the risks around the distribution, those we face on the way to the distribution, or at the distribution site. They also reflected our experience with aid distributers.

In Empowered Aid's second phase, the recommendations for making aid distributions safer were piloted with NGO operational partners who distribute food and non-food items (NFIs), using an implementation science approach. The women and girls engaged as refuge researchers in phase 1 elected to continue being involved in the study and formed Refugee Advisory Groups. They input into the adapted distribution monitoring and evaluation tools to ensure their findings were accurately reflected and that the survey and focus group questions could be easily understood, and reviewed the pilot findings on what SEA risks were found and how they were addressed.

Sharing power in data analysis and synthesis processes supports research to remain accountable to those who live closest to the problems under study. Women and girl refugee research team members shared that seeing their contributions in Phase I put into action in Phase II was instrumental in building trust because they could see the information they shared was linked to action in their communities. As ‘Malak’, a Syrian adolescent girl researcher in Lebanon, said,

I felt very comfortable sharing my experiences, especially because we were able to make the voices of women and girls heard. Telling our stories and the stories of other women and girls will give us a lot of strength moving forward.

Co-production of knowledge and consideration for ethics in communicating research

This participatory action research took place within an international system of humanitarian aid that, in many ways, is oriented along the same narratives of white saviourism that underscored the colonial endeavour (Jayawickrama, Citation2018). In communicating who is being helped and who is the helper, there are opportunities to change those narratives. Oliveira and Walker (Citation2019) describe the type of facilitated dialogues necessary to responsibly discuss what it means to publish the stories, art and other creations of those involved in participatory research. With women migrants engaged in the Mwangaza Mama project, they held multiple conversations – collectively and one-on-one – about risks, benefits, consent, the power of stories and the multiple ways they may be used: ‘Many of the women expressed strong sentiments towards the negative stories that are often told in the media, and by politicians, about migrants, refugees and woman migrants’. (pp. 30–31)

Within Empowered Aid, consent was also an ongoing process and included a number of facilitated conversations about how the research was communicated, if and how photographs were taken and used, what messages were intended to be conveyed and other possible perceptions. In considering who to target for dissemination, questions posed included ‘Who has the most power to respond to the findings and the recommendations put forward by women and girls?’, and ‘Who is often left out of research dissemination and uptake efforts?’ Answering them led to local humanitarian stakeholders and affected communities within each country being prioritised for dissemination efforts above preparing findings for publication in academic journals. Creative, visual methods were used to convey results in accessible formats such as short videos and animations disseminated over WhatsApp, for those who may not be able to read traditional research products like reports, briefs, and articles and/or access research products online. The process of publishing the study's findings in peer-reviewed journals is now underway and engages many team members who are new to scientific writing, through a series of interactive workshops to ‘demystify’ this process: from choosing prospective journals, to how to write for publication, to navigating authorship and referencing guidelines.

At the outset of the study, Technical Advisory Groups (TAGs) were set up in each country, and globally, to review the tools, advise the research team and support dissemination. TAG members were drawn from government ministries, multilateral organisations, international aid agencies, national aid agencies, civil society actors including women's rights organisations from affected communities, and Global South academics and researchers. Involving TAG members in the research process established a foundation for deeper understanding of the findings, among key humanitarian stakeholders who hold power to put them into action. It leveraged relationships of varying power to ensure those responsible for the health and rights of crisis-affected populations are receptive to processes in which their own institutions are potentially implicated in doing harm.

Discussion

Take time to build trust and share stories rather than ‘extract’ data

Applying participatory, feminist, and anthropological approaches allows us to put forward a reimagined definition of research as, ‘Taking the time to collectively look for answers to the questions we deem vital’. Taking time is an important consideration in collaborative research, as Walker and Oliveira (Citation2020) write:

… recognition of women's agency and power coupled with our “slow approach” to research offered everyone involved in the project time to get to know one another and time to build trust and confidence. Validating different forms of knowledge and varying levels of expertise also opened up the intellectual and practical space for the women to help guide the pace and direction of the group. (p. 194)

Longitudinal data collection processes that engaged women and girl co-researchers at multiple points, and in multiple ways, contributed to a sense of trust by those sharing their knowledge. Their involvement in deciding how the research would be communicated, described above, increased trust that it will be represented as theirs and acted upon; rather than being extracted to be taken overseas, analysed and used in ways often invisible to study participants. Slower approaches centre the principles of mutual value and respect, and help to minimise the attitude of entitlement that many researchers are perceived to hold by non-research partners and affected communities – as one of our NGO co-researchers describes it, ‘That participants owe them information’.

In addition to time, place played an important role in trust-building. Refugee women and girls chose where and when they wanted to meet, and this was often in Women and Girls Safe Spaces run by partner NGOs, with whom they were already familiar and had built trust over time. Partnering with operational NGOs who operate and provide high-quality gender-based violence prevention and response services also served as an indication that those involved in managing the study wanted women to feel safe, and prioritised partnered with organisations that value and recognise their safety and voice. Partnerships with NGOs in charge of food distribution in the second phase demonstrated the commitment to applying findings from the participatory action research in ways that have a very practical and immediate impact on their lives.

Throughout, multiple avenues for feedback and asking questions were provided, including in-person meetings, WhatApp groups, and the ability to visit the Safe Spaces at any time to ask questions. This does not however mean that there were no trust issues. For example, at times when a translator located at one of the Safe Spaces was unwell and another translator was introduced, some of the refugee women and girls openly expressed their discomfort talking to a new person. At these times, the interview would be rescheduled with a person with whom they felt comfortable. As ‘Mona’, one of the Syrian women refugee researchers in Lebanon shared, ‘My experience was very good. It allowed me to speak and express my opinions freely. All we wanted was for someone to give us the space to express our thoughts. My personality grew stronger through this experience’.

Engage in collective meaning-making with those whose lived experiences are a form of expertise

Current day ‘humanitarian crises’ stem, at least in part, from the legacies of colonisation in Africa, the Middle East and Asia. Extractive research processes share these colonial origins and often lead to indigenous peoples’ feelings of being simultaneously used and rejected (Smith, Citation1999). To undo this process, we must change how meaning is made and by whom:

Decolonization of knowledge is about questioning who has the power over knowledge production, dissemination and management and eventually decentering those sources of power by bringing in others who were marginalized by colonization. In short, it is about re-centering First nation peoples whose erasure was the number one project of colonization. (Iyer, Citation2020)

Research in humanitarian contexts can be carried out in ways that support a re-centring of those living at the ‘intersection’ or ‘collision’ of unequal power dynamics due to sex, race, ethnicity, migration status, citizenship status and other factors (Crenshaw, Citation1989; Kimberlé Crenshaw on Intersectionality, More than Two Decades Later, Citation2017). The ‘do no harm’ approach central to research ethics and humanitarian action requires it; to fail to consider such re-centring is as harmful as actively working against it (Anderson, Citation1999; World Health Organisation, Citation2007). As co-author and Ugandan feminist activist Harriet Kolli, shared during one of the reflection exercises,

We are no longer talking about just responding, but are collectively generating ideas on how we can prevent the risks [of SEA] for women and girls, and how we are mitigating those risks before they even happen. It's the women and girls who will be telling us that these are the risks, they will be the same people who are generating solutions for these risks.

The TANGLED Research Study for Young Women, led by Dr. Kamila Alexander of Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, speaks to the experiences of Black women and the legacy of harm health research has done to their communities in the U.S. and elsewhere: ‘Research takes from our community and never gives us anything back’ (Alexander et al., Citation2021). Dr. Alexander and her team use participatory methods to examine intimate partner violence among young Black women, using a strengths-based approach to increase awareness and response:

For many of them, this is a new dialogue for experiences they have never shared. What's more, their reflections illustrate the possibility for an unorthodox yet critical role that research can play in reforming our approach to preventing systemic violence and abuse: diffusing the awareness that violence is not a natural part of life, and sharing the tools to address it, throughout that person's community and social networks. (Alexander et al., Citation2021)

This echoes feedback from the refugee women and girl researchers involved in Empowered Aid, as well as NGO-based staff and the wider refugee and host community members engaged, including men, boys and people living with disabilities. During a participatory group discussion with refugee women living with disabilities in Uganda, one woman told us, ‘I am happy for you people for having called us to know our concerns and our problems, especially us the disabled we are really going through a lot of problems’. As Leila Billing (Citation2020) writes, specifically in relation to research and programming designed to address SEA (also called ‘safeguarding’):

This commitment to transformation requires us to ‘see’ and work differently with impacted communities, local actors and survivors. It recognises that the production of knowledge is a project of power, and that safeguarding approaches — if they are to foreground the needs and rights of survivors — must be developed in more collaborative ways that disrupt the hierarchical binaries of northern/’expert’ and local/community knowledge. (Billing, Citation2020)

Consider how knowledge is represented and with whom it is shared

The feminist, anthropological, participatory methods we have described here, and the drive to document and share all of the accompanying tools and guidance we have developed for Empowered Aid so that others may take, adapt, and use them, is an expression of solidarity in building not only scholarship, but freely accessible tools for such scholarship that break down barriers of access. The self-published research documents are remediated for readability by those living with low vision, and many are translated. Funding did not allow for full translation, especially into minority languages or other formats, such as braille. This is an important gap to note and account for within research budgets and donor advocacy.

In research on sexuality, health and rights, including research on gender-based violence, there has long been a recognition that naming and documenting the harms that are largely perpetrated by men against women and girls, is a form of solidarity as well as activism. This can be seen as contrary to objectivity in research; yet research methods that fail to incorporate examinations of power and positionality may not be ‘objective’ so much as failing to transparently examine the social, geographical and historical contexts within which any research activity takes place. Drawing on the work of Stacey and Thorne (Citation1985), Tavris (Citation1993), and others, Beth Wigginton and Michelle N. Lafrance (Citation2019) write, ‘Although purporting to be ‘objective’ and value-neutral, science has often functioned in the disservice of marginalised groups, and feminists have been among the most vociferous critics’. The use of field notes, described above, can be applied to any research methodology to reinforce structures for self-reflection and make more visible linkages with what conclusions are drawn, how and by whom. Dr. Raul Pacheco-Vega (Citation2019) describes this as a ‘democratizing’ practice that has implications for the policymakers using research to address social problems as well: ‘Writing field notes is both an exercise in practicing how and what we write, but also who we write into our fieldwork, and who we exclude, and what elements we include in our analysis’ (p. 2).

Systematically reflecting on positionality and power increases space for considering how intersectional dynamics of power and control underpin determinations of legitimacy and credibility in relation to the source of knowledge. As Sharlene Nagy Hesse-Biber (Citation2012) writes:

Feminist perspectives also carry messages of empowerment that challenge the encircling of knowledge claims by those who occupy privileged positions. Feminist thinking and practice require taking steps from the “margins to the center” while eliminating boundaries that privilege dominant forms of knowledge building, boundaries that mark who can be a knower and what can be known. (Hesse-Biber, Citation2012, p. 3)

Within the study's Technical Advisory Groups (TAGs), actors often denied a ‘seat at the table’ in humanitarian decision-making processes contribute at the same level as more powerful actors. Given many TAG members are from agencies potentially implicated in such abuses, engaging their staff as champions of this work and/or opening space for learning about it allowed us to collectively embark on a process of discovery, in which the voices of refugee women and girls led the actions and decisions of aid agency decision-makers. By centreing not only their voices, but also their analysis and recommendations, the research employed structures to address the labels often given to participatory, feminist, anthropological and/or qualitative methodologies as less ‘legitimate’ or ‘credible’, especially in relation to quantitative methodologies that are often seen as more ‘objective’.

Conclusion

The processes through which research is designed, conducted and shared must be as valued as its ‘products’ or ‘findings’. In this article, we consider the ways in which gender-based violence research in humanitarian settings – where power imbalances are heightened and the populations under study may not be able to fully access their rights – can seek to shift power back into the hands of those most affected by crisis. Applying participatory, feminist and anthropological methods and approaches throughout the research process allows for the building of trust and sharing of stories rather than ‘extracting’ data; engages in collective meaning-making with those whose lived experiences are a form of expertise; and carefully considers how knowledge is represented and with whom it is shared. Such research processes expand who is considered a knowledge producer, how knowledge is represented and with whom it is shared.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the 55 South Sudanese and Syrian women who shared their knowledge and expertise as refugee co-researchers (identified by their name or preferred pseudonym in quotation marks): Harriet Opani, Mary Kiden, Sitima, Karaba Peter, Julia, Hellen Manano, Harriet Tabu, Dauphine, Mary C, Janet, Laura Cinthy, Mirabel, Emmy Baraza, Lady Aminah, Rose Monday, Grace Kiden, Esther Namadi, Grace Awate, Margret Kiden, Angaika Poni, ‘Malak’, Suzan Taktak,‘Zeina’, Amal Koussa, ‘Leila’, Imane Ibrahim, ‘Jawaher’, ‘Mona’, ‘Nawal’, and Lama Sibaii. We also acknowledge and deeply thank the Empowered Aid research team who participated in Phase 1 study co-design processes, data collection, analysis, and write-up: globally, Elizabeth Hedge, Amelia Reese, Chelsea Ullman, Aminat Balogun, Amal Hassan, and Zoe Garbis; in Uganda, Esther Apolot, Monica Ayikow, Nancy Awio, Annet Fura, Aminah Likicho, Fatuma Nafish, Chandiru Zamuradi, Lealya Sebbi, Zuleika Munduru, Zahara Beria, Harriet Kezaabu, Anne Grace Aleso, Doreen Abalo, Consolate Apio, Aishah Namugenyi, and Monica Ayite; in Lebanon: Farah Hallak, Georgette Alkarnawayta, Wafaa Obeid, Reem Boukhary, Farah Baltagi, Angeliki Panagoulia, and Marwa Rahhal. Further acknowledgements go to colleagues at the Global Women’s Institute (GWI), International Rescue Committee in Uganda, and CARE International in Lebanon, who supported implementation of the study; and to the members of Empowered Aid’s global and national Technical Advisory Groups, who contributed to research design, analysis, and uptake. We are deeply grateful to the refugee and host community members and humanitarian stakeholders who generously shared their time and stories with us; and appreciate the helpful comments of three anonymous reviewers and the special issue editors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Reports of the findings and recommendations for action, as well as the research tools and guides, are available online at https://globalwomensinstitute.gwu.edu/empowered-aid-resources; a peer-reviewed journal publication is forthcoming.

2 All of the study's tools and resources, including workshop facilitation guides, are documented and made available on GWI's website to facilitate their use and further adaptation by others: https://globalwomensinstitute.gwu.edu/empowered-aid-resources.

3 Quotes collected during primary data collection are anonymised. Those shared during the development of an online course, in which all research team members who consented are involved in teaching others about Empowered Aid's methods and tools, are credited with consent and to the degree the person prefers: their full name, first name only, or a pseudonym (indicated by quotation marks, as with ‘Mona’).

References

- Alexander, K., Goldberg, R., & Eddleton, M., & TANGLED Research Study Team. (2021, February 24). “Tangled” study is overcoming mistrust of research among Black women to reform our approach to systemic intimate partner violence. Johns Hopkins Nursing Magazine. https://magazine.nursing.jhu.edu/2021/02/tangled-study-is-overcoming-mistrust-of-research-among-black-women-to-reform-our-approach-to-systemic-intimate-partner-violence/.

- Alonso Bejarano, C., López Juárez, L., Mijangos García, M. A., & Goldstein, D. M. (2019). Decolonizing ethnography: Undocumented immigrants and new directions in social science. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478004547

- Anderson, M. B. (1999). Do no harm: How aid can support peace–or war. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Baum, F., MacDougall, C., & Smith, D. (2006, October). Participatory action research. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 60(10), 854–857. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2566051/. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.028662

- Billing, L. (2020, October 12). How feminist leadership can strengthen global development’s approach to safeguarding. Medium. https://leila-billing.medium.com/how-feminist-leadership-can-strengthen-global-developments-approach-to-safeguarding-b4fa68e99930.

- Bradshaw, S., Linneker, B., & Overton, L. (2016). Gender and social accountability: Ensuring women’s inclusion in citizen-led accountability programming relating to extractive industries. Oxfam America. https://s3.amazonaws.com/oxfam-us/www/static/media/files/Research_Backgrounder_Gender_and_Social_Accountability_Final.pdf.

- Bunn, C., Kalinga, C., Mtema, O., Abdulla, S., Dillip, A., Lwanda, J., Mtenga, S. M., Sharp, J., Strachan, Z., Gray, C. M. & Culture and Bodies’ Team. (2020). Arts-based approaches to promoting health in sub-Saharan Africa: A scoping review. BMJ Global Health, 5(5), e001987. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001987

- Chadwick, R. (2021, February 24). Reflecting on discomfort in research. Impact of Social Sciences. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2021/02/24/reflecting-on-discomfort-in-research/.

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine. Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 31. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8.

- Davis, L. V., & Srinivasan, M. (1995). Listening to the voices of battered women: What helps them escape violence. Affilia, 10(1), 49–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/088610999501000106

- Devictor, X. (2019, December 9). 2019 update: How long do refugees stay in exile? To find out, beware of averages [World Bank Blogs]. Development for Peace. https://blogs.worldbank.org/dev4peace/2019-update-how-long-do-refugees-stay-exile-find-out-beware-averages.

- England, K. V. L. (1994). Getting personal: Reflexivity, positionality, and feminist research. The Professional Geographer, 46(1), 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0033-0124.1994.00080.x

- Hesse-Biber, S. N. (2012). Feminist research: Exploring, interrogating, and transforming the interconnections of epistemology, methodology, and method. In S. Hesse-Biber (Ed.), Handbook of feminist research: Theory and praxis (pp. 2–26). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483384740.n1

- Holmes, A. G. D. (2020). Researcher positionality – A consideration of its influence and place in qualitative research – A New researcher guide. Shanlax International Journal of Education, 8(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.34293/education.v8i4.3232

- Iyer, P. (2020). Do not colonize decolonization. The Peace Chronicle: The Magazine of the Peace and Justice Studies Association, 12(2), 36–38. https://www.peacejusticestudies.org/chronicle/do-not-colonizedecolonization/#:∼:text=Decolonization%20of%20knowledge%20is%20about,who%20were%20marginalized%20by%20colonization.

- Jayawickrama, J. (2018, February 24). Humanitarian aid system is a continuation of the colonial project. Al Jazeera. www.aljazeera.com/amp/opinions/2018/2/24/humanitarian-aid-system-is-a-continuation-of-the-colonial-project.

- Kimberlé Crenshaw on Intersectionality, More than Two Decades Later. (2017, June 8). Columbia Law School. https://www.law.columbia.edu/news/archive/kimberle-crenshaw-intersectionality-more-two-decades-later.

- Kistner, J. (2019). “I am coming here to get strong.”. In E. Oliveira, & R. Walker (Eds.), Mwangaza Mamas: A participatory arts-based research project (pp. 17–19). The MoVE Project and African Centre for Migration and Society (ACMS), University of the Witwatersrand. https://issuu.com/move.methods.visual.explore/docs/mwangaza_mama_ebook.

- Mitchell, C., & Sommer, M. (2016). Participatory visual methodologies in global public health. Global Public Health, 11(5-6), 521–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2016.1170184

- Oliveira, E. (2019). The personal is political: A feminist reflection on a journey into participatory arts-based research with sex worker migrants in South Africa. Gender & Development, 27(3), 523–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2019.1664047

- Oliveira, E., & Vearey, J. (2017). Beyond the single story: Creative research approaches with migrant sex workers in South Africa. Families, Relationships and Societies, 6(2), 317–321. https://doi.org/10.1332/204674317X14937364476877

- Oliveira, E., & Walker, R. (2019). Making sense of experience. In E. Oliveira, & R. Walker (Eds.), Mwangaza Mamas: A participatory arts-based research project (pp. 21–37). The MoVE Project and African Centre for Migration and Society (ACMS), University of the Witwatersrand. https://issuu.com/move.methods.visual.explore/docs/mwangaza_mama_ebook.

- Pacheco-Vega, R. (2019). Writing field notes and using them to prompt scholarly writing. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, Article 1609406919840093. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919840093

- Raising Voices and the Sexual Violence Research Initiative (SVRI). (2020). Learning together: A guide for feminist practice in violence against women and girls research collaborations. Kampala, Uganda and Pretoria, South Africa.

- SASA!. (n.d.). Raising voices. Retrieved September 16, 2020, from https://raisingvoices.org/sasa/.

- Singh, N. S., Lokot, M., Undie, C.-C., Onyango, M. A., Morgan, R., Harmer, A., Freedman, J., & Heidari, S. (2021). Research in forced displacement: Guidance for a feminist and decolonial approach. The Lancet, 397(10274), 560–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00024-6

- Smith, L. T. (1999). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples (1st ed). Zed Books.

- Stacey, J., & Thorne, B. (1985). The missing feminist revolution in sociology. Social Problems, 32(4), 301–316. https://doi.org/10.2307/800754

- Tavris, C. (1993). The mismeasure of woman. Feminism & Psychology, 3(2), 149–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353593032002

- The Global Women’s Institute. (2020a). Empowered aid: Action analysis workshop facilitation guide for research partner staff. The Global Women’s Institute at The George Washington University. https://globalwomensinstitute.gwu.edu/sites/g/files/zaxdzs1356/f/downloads/GWI-EmpoweredAid-ActionAnalysisWorkshopGuide-Staff-Final_a11y.pdf.

- The Global Women’s Institute. (2020b). Empowered aid: Participatory action research workshop facilitation guide. The Global Women’s Institute at The George Washington University. https://globalwomensinstitute.gwu.edu/sites/g/files/zaxdzs1356/f/downloads/GWI-EmpoweredAid-PARWorkshopFacilitationGuide-Final_a11y.pdf.

- The Global Women’s Institute. (2020c). Empowered aid: Participatory action toolkit. The Global Women’s Institute at The George Washington University. https://globalwomensinstitute.gwu.edu/sites/g/files/zaxdzs1356/f/downloads/GWI-EmpoweredAid-DataCollectionToolkit-Final.pdf.

- The Global Women’s Institute. (2020d). Empowered aid: Research reflection workshop facilitation guide. Washington, DC: The Global Women’s Institute at The George Washington University. https://globalwomensinstitute.gwu.edu/sites/g/files/zaxdzs1356/f/downloads/GWI-EmpoweredAid-ResearchReflectionWorkshopGuide-Final_a11y.pdf.

- Walker, R., & Oliveira, E. (2020). A creative storytelling project with women migrants in Johannesburg, South Africa. Studies in Social Justice, 14(1), 188–209. https://doi.org/10.26522/ssj.v2020i14.2218

- Webb, C. (1993). Feminist research: Definitions, methodology, methods and evaluation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 18(3), 416–423. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1993.18030416.x

- Wigginton, B., & Lafrance, M. N. (2019). Learning critical feminist research: A brief introduction to feminist epistemologies and methodologies. Feminism & Psychology, 1–17 .https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353519866058.

- Wise, S. (1987). A framework for discussing ethical issues in feminist research. In Vivienne Griffiths et al. (Ed.), Writing feminist biography, 2: Using life histories (pp. 47–88). Manchester: Department of Sociology, University of Manchester.

- World Health Organisation. (2007). WHO ethical and safety recommendations for researching, documenting and monitoring sexual violence in emergencies. WHO.