ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the extent to which national laws and policies shape public health and economic security. Paid leave policies enable parents to meet children’s health needs while maintaining job and income security. These policies matter immensely to children’s health every year. Yet, little is known about the extent to which policies exist to support the full range of childhood health needs. Using a novel dataset constructed from legislative text in 193 countries, this study assesses whether laws in place in 2019 are adequate to support meeting children’s everyday, serious, and disability-related health needs. Globally, only half of the countries guaranteed working parents access to any paid leave that could be used to meet children’s health needs. Only a third addressed everyday health needs, including leave that matters to reducing infectious disease spread. For serious health needs, even when paid leave was available, it was often too short for complex health conditions. Moreover, although all children require parental presence at medical appointments and for serious illness, fewer countries guaranteed paid leave to care for older children than younger. Addressing these gaps is crucial to supporting child health and working families during times of public health crisis and every year.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has increased the visibility of the importance of paid sick leave policies, highlighting their critical role in slowing disease spread while enabling workers to respond to health needs without fear of job or significant income loss (Fong, Ms, et al., Citation2020; Heymann et al., Citation2020). The pandemic has also markedly increased caregiving needs due both to the widespread closure of schools and rules that keep children home when schools are open due to more routine childhood illnesses or potential exposures to COVID-19 (CDC, Citation2020; UNICEF, Citation2021). While the debate has expanded over the past two years around paid personal sick leave, despite the increased visibility of care needs, less attention has been paid to the long-term policies in place to support working parents caring for their children’s health needs.

Role of paid leave in supporting health

Paid leave supports children’s health by providing parents with the time they need to support children’s health needs while simultaneously ensuring job and income security. Parental presence is recognised as central to children’s care and recovery (O'Connor et al., Citation2019). At the same time parents’ continued attachment to the labour force and the corresponding economic security for families is critical to long-term health outcomes for children, particularly during times of economic downturn when jobs are scarce (Sigurdsen et al., Citation2011). Economic security during childhood can also have long-run impacts due to the foundational role that income plays as a social determinant of health (Coker et al., Citation2013; Donkin et al., Citation2017).

Countries around the world have recognised the importance of providing paid leave to support parental attachment to the labour force while meeting young children’s care needs through paid parental leave (Heymann et al., Citation2017), which is leave that is available to parents to provide care after the birth of a child. Research has shown that paid parental leave policies matter to children’s health outcomes, as well as to economic outcomes for families, particularly mothers’ employment (Nandi et al., Citation2018). Specifically, research in both high and low-income settings links paid parental leave to lower infant mortality (Nandi et al., Citation2016; Tanaka, Citation2005). Plausible mechanisms for this relationship include by ensuring income security and supporting quality parental care that ensures parents have the time they need to respond to and prevent illness and injury. Multiple studies have examined the link between paid leave and increased vaccination rates (Choudhury & Polachek, Citation2021; Hajizadeh et al., Citation2015) and increased exclusive breastfeeding (Chai et al., Citation2018; Huang & Yang, Citation2015) which also supports reduced diarrheal disease (Chai et al., Citation2020)., Yet, while paid parental leave policies are nearly universal, initial research suggests that paid leave to meet children’s health needs beyond infancy is far less common (Heymann et al., Citation2017).

Children’s routine and preventive health needs

As the pandemic has highlighted, childcare needs persist far beyond infancy and continue even after children have transitioned to school. Illness is a leading reason for children to miss school in countries around the world (Kearney, Citation2008), and especially common amongst young children as they start childcare or school (Colds in Children, Citation2005). Infectious and gastrointestinal disease is even more prevalent in settings where children lack access to adequate handwashing and sanitation facilities (Jasper et al., Citation2012). Seasonal illnesses, such as influenza, are also a regular concern in countries around the world (Ambrose & Antonova, Citation2014; Pourabbasi et al., Citation2012; Principi et al., Citation2003).

Beyond benefits to individual families, paid leave also supports a stronger public health system. Strategies for reducing the spread of seasonal illnesses and gastrointestinal disease include keeping children home while sick (Fong, Ms, et al., Citation2020). Paid leave helps to reduce the spread of infectious disease in communities and decreases unnecessary emergency room visits (Fong, Gao, et al., Citation2020; Li & Leader, Citation2007). This is important in any year, but particularly critical in the context of a pandemic.

Paid leave also matters to ensuring that parents can meet children’s preventive health needs. Studies show that parents without access to paid leave are less likely to be able to meet their children’s preventive health needs, including childhood vaccinations that matter to reducing future disease spread (Asfaw & Colopy, Citation2017; Clemans-cope et al., Citation2008; Seixas & Macinko, Citation2020; Shepherd-Banigan et al., Citation2017).

Serious and complex health needs

Beyond routine illnesses and preventive health needs, some children face additional health challenges, whether due to serious illnesses or injuries, chronic health conditions, or disabilities, that require parental presence. One study estimated that, on average, children with special health needs miss 20 days of school or childcare a year (Chung et al., Citation2007). Yet, looking at the average time needed hides variation in care needs for children with serious and complex health needs. Among the highest level of disease burden for children globally are congenital birth defects, malaria, meningitis, HIV/AIDS, and childhood cancer (Force et al., Citation2019). For some of these diseases, care needs are both lengthy and on-going. For example, Down Syndrome, a type of congenital birth defect, requires on-going and intensive care. One US study found nearly a third of parents of children with Down Syndrome report spending 11 or more hours per week on health care (Phelps et al., Citation2012). Similarly, childhood cancer may also require lengthy periods of care, particularly in the first year after diagnosis; one study highlighted in a systematic review found Swiss parents used on average 240 working days to respond to their child’s treatment after a cancer diagnosis (Roser et al., Citation2019). Other serious illnesses may require shorter periods of care to respond to acute attacks. For example, one study of malaria in Sri Lanka estimated that on average children missed 5.4 days of school for an uncomplicated, acute attack of malaria, but many children suffered multiple attacks over the two-year period studied (Fernando et al., Citation2003). Similarly, a common first-line treatment for meningitis in low- and middle-income countries typically takes five days to see clinical improvement, but some children will suffer long-term impacts that require on-going care (WHO, Citation2019). In cases where chronic illness or disability is well-managed, the majority of care needs may be short to attend more frequent medical appointments. For example, a study of HIV-infected children in Botswana found that while 60% of children had missed at least one day of school in the previous month, most of these absences were short (1–3 days) and related to medical appointments (Anabwani et al., Citation2016).

Numerous studies have highlighted the impact of these care needs on parental employment, particularly for mothers (Earle & Heymann, Citation2012; Gnanasekaran et al., Citation2016; Roser et al., Citation2019). Paid leave can play a critical role in mitigating the impacts of serious health conditions on families (Earle & Heymann, Citation2012). A review study of the economic effects of a childhood cancer diagnosis suggests that differences in impacts on parental employment across countries could be driven by differences in access to paid leave (Roser et al., Citation2019). Conversely, a lack of paid leave can also impact the care that children receive. One U.S. study found that 41% of parents of children with special health needs reported not being able to miss work when their child needed them and parents who did take leave also frequently reported having to return to work too early (Chung et al., Citation2007). Moreover, the job and income security provided by paid leave can also help to support caregiver health (Earle & Heymann, Citation2011; Schuster et al., Citation2009), a critical concern for parents of children with special health needs given the prevalence of parental caregiving stress and the impact that has on children (Cousino & Hazen, Citation2013).

Existing research on paid leave

Despite the importance of paid leave for children’s health, family economic security, and public health, there has been limited research on the existence and adequacy of paid leave for children’s health needs. Earle and Heymann provided a first comprehensive analysis of whether short-term leave for family health needs exists, but this review did not distinguish between leave available for routine and serious health needs (Citation2006). A subsequent study examined the adequacy of the availability of paid leave for serious illnesses in high-income countries (Raub et al., Citation2018).

Previous studies have also not examined the structure of paid leave for children’s health needs policies that disproportionately matter to different family types. In high- and low-income countries alike, single parents and families with a large number of children are at greater risk of living in poverty (Boudet et al., Citation2021; Castañeda et al., Citation2016; Thévenon et al., Citation2018). Yet, research from high-income countries on paid parental leave has identified policy gaps that leave single-parent families with access to less total leave than two-parent families (Jou et al., Citation2020). Understanding the extent to which paid leave for children’s health needs is adequate for these families is critical to supporting child health and reducing poverty.

Moreover, comparative studies to date have not deeply examined how the structure of paid leave policies can exacerbate gender disparities in caregiving. Around the world, women are disproportionately responsible for care responsibilities (ILO, Citation2018), including children’s health needs (Daly & Groes, Citation2017; Maume, Citation2008; Roser et al., Citation2019), which contributes to gender inequality in economic outcomes. Gendered expectations around care impact not only women’s economic opportunities, but also men who want to be involved caregivers (Berdahl & Moon, Citation2013; Kuo et al., Citation2018). Evidence from Sweden suggests that structure of the paid leave for children’s health needs matters to men’s leave usage with gender disparities when leave is shared between parents (Boye, Citation2015; Eriksson, Citation2011). These findings are consistent with the larger body of research on gender disparities in the usage of paid parental leave and evidence that policy innovations such as incentives and use-it-or-lose it policies are needed to support men’s utilisation of paid leave (Heymann et al., Citation2017). Moreover, a recent study using data from nine countries found that these policy approaches can shift norms held by both men and women towards a more egalitarian view of women’s roles (Omidakhsh et al., Citation2020).

This is the first study to look comprehensively across all 193 United Nations (UN) member states to examine whether adequate paid leave policies exist to address a full range of children’s health needs. It looks separately at (1) leave available for everyday health needs, such as seasonal illnesses or preventive health needs, (2) leave available for serious health needs, such as when a child is hospitalised or undergoing cancer treatments, and (3) leave available to support the on-going health needs of children with disabilities. For each area, we examine the adequacy of paid leave as measured in both duration and wage replacement rate. We also examine factors that matter to leave adequacy and availability to larger families, single parents, and gender equality in taking leave.

Methods

Data

This study uses original data created by the WORLD Policy Analysis Centre. To construct data on legislative approaches to paid leave for children’s health needs, a team of researchers conducted a systematic review of labour and social security legislation in place as of March 2019 across all 193 UN member states. The primary source for the data was original, full-text legislation sourced through the International Labour Organisation (ILO)’s NATLEX database supplemented with legislation sourced from country government websites, law libraries, and other sources. Information was also corroborated using data from Social Security Programmes Throughout the World, the Mutual Information System on Social Protection, and the Mutual Information System on Social Protection of the Council of Europe.

For each country, two researchers read the legislation in full and answered questions about it. Whenever possible, legislation was read in its original language by a team fluent in English, French, Spanish, Portuguese, and other languages. Translation services were used as needed when legislation was unavailable in an official translation. Researchers then reconciled their answers and discussed any difficult cases as a team to ensure a comparable method was used across all 193 countries. Once coding was complete, additional quality checks were conducted, including outlier and randomised checks.

Policy indicators

Identifying leave

Our analysis of paid leave included both leave provided specifically for children’s health needs and other types of leave that could be used to meet children’s health needs. Leave specifically for children’s health needs included paid leave that is mandated to be provided by employers and social security-provided benefits for parents caring for children’s or more generally family members health needs. These social security benefits may be provided independently of job protection. Our analysis of other types of leave that could be used to meet children’s health needs included emergency leave, family needs leave, discretionary leave, or casual leave. Our measure of paid leave captures leaves broadly available to workers in the private sector. Provisions specific to the public sector were excluded because in many countries they do not cover the majority of workers. When paid leave was legislated sub-nationally or by industry, the least generous policy was captured. That is, if one state did not guarantee paid leave for children’s health needs or only workers in factories were guaranteed paid leave, we did not capture a guarantee of paid leave for the country as a whole. Paid leave provided by collective bargaining was only included when it broadly applied to the private sector.

Throughout this paper, ‘no paid leave’ refers both to countries that have no leave policies to meet children’s health needs and countries that guarantee unpaid leave. Prior research suggests that unpaid leave is primarily a benefit for higher wage workers.

Types of leave

We differentiate between three types of leave specifically available for children’s health needs. The first is to leave available for children’s everyday health needs. This is leave that is specifically available for parents to meet their children’s health needs and includes references broadly to health, to care for sick children, or to take children to medical appointments. The second type is leave for children’s serious health needs. These are leaves that place additional restrictions on the circumstances that parents can take paid health leave, including for imminent death, specific illnesses, only in the case of hospitalisation, for chronic illnesses, and for serious health needs only. The third type of leave is leave specifically care for or meet the health needs of children with disabilities. For serious health needs, we considered both leave generally available for children’s health needs and leave specifically for serious health needs, assuming that when multiple types of leave exist, parents would make use of all sources of leave. Similarly, for disability-related health needs, we considered both disability-specific paid leave and leave generally available for children’s health needs.

Duration of leave

We categorised the duration of leave available in weeks. When legislation specified the duration of leave in calendar days, we converted to weeks by dividing by 7. When legislation specified the duration of leave in working days or days without clarifying whether it was calendar or working, we accounted for country differences in a 5 or 6 d work week to convert to weeks. For everyday or disability-specific health needs, we considered leave to be ‘available as needed’ when leave was available until recovery without specifying a maximum amount of leave or when at least three days of leave was available for each incident of illness without specifying a maximum number of days per year that leave could be taken. For serious health needs, we also separately captured when leave was available ‘for the duration of hospitalisation’ for countries that did not specify a maximum amount of leave in a given year, but did make leave available for the full duration of hospitalisation or in-patient treatment.

In some countries, leave availability differed by the age of the child. Accordingly, we analysed differences in the duration of paid leave for children ages 2, 5, 8, 12, and 15 years old to capture the full range of policy differences as children grow. While younger children may require more direct supervision, parental presence is still needed to take children of all ages to medical appointments and support care, particularly for more serious illnesses and injuries.

Conditions on use of leave for serious health needs

We separately categorised when countries placed conditions on the use of leave for serious health needs that might limit parents’ ability to respond in the event of emergent serious health conditions, including accidents and injuries, and chronic serious health conditions. Restrictions on using leave identified include leave available only for imminent death or risk of imminent death, for specific illnesses, in cases of hospitalisation, and only for children with chronic illnesses. We considered leave to be available generally for serious health needs when countries broadly referred to serious illnesses or injuries or if leave specifically covered both hospitalisation and chronic illnesses.

Wage replacement rates

We categorised the wage replacement rate of paid leave based on the percentage of wages parents were guaranteed while on leave. Higher wage replacement rates make taking leave more affordable for low-income families, but are also costlier to administer. We separately coded the minimum and maximum wage replacement rate to capture variation that exists in some countries. We captured payments as a ‘flat rate or adjusted flat rate’ when countries did not base payment on a workers’ wages, but instead guaranteed workers a flat rate payment or a percentage of unemployment benefits.

Structure of leave

To assess the adequacy of paid leave policies to support a diversity of families and gender equality, we assessed whether everyday or serious illness leave was available as an individual or family entitlement and differences in leave availability based on the number of children and parent’s marital status.

Analysis

Variables were constructed and analysed using Stata 14. Differences were assessed by country income group using the Pearson’s chi-square statistics to address questions of whether all countries can afford to provide parents with access to paid leave for children’s health needs. Differences were also assessed by region. Country income level and region were categorised according to the World Bank’s country and lending groups as of 2019.Footnote1

Results

Availability of any leave for children’s health needs

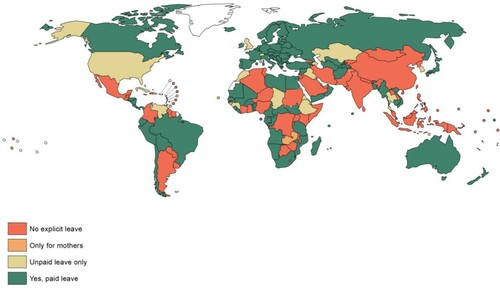

Globally, only half of all countries (51%) guaranteed any leave that can be used to meet children’s health needs, including more general leave, such as family needs and emergency leave, or leave that is only available to respond to serious illnesses. An additional 12% of countries guaranteed only unpaid leave that can be used to meet children’s health needs. In two percent of countries leave for children’s health needs was only available to working mothers, reinforcing gender inequality in caregiving ().

Guarantees of some approach to paid leave to meet children’s health needs were more common in high-income countries (69%) than middle- (41%, p < 0.01) or low-income countries (48%, p < 0.1). Similarly, while countries guaranteeing some approach to paid leave for children’s health needs could be found in every region in the world, these guarantees were most common in Europe and Central Asia (85%) and South Asia (50%).

Availability and adequacy of paid leave for children’s everyday health needs

Fewer countries (35%) guaranteed an approach to paid leave that can be used to meet children’s everyday health needs, such as providing care during routine illnesses or taking children for preventive medical care. High-income countries were more likely to guarantee this paid leave than middle-income (47% compared to 28%, p < 0.05), but not statistically different compared to low-income countries (35%). Sixty percent of countries in Europe and Central Asia took some approach to guaranteeing paid leave for children’s everyday health needs, followed by 38% of countries in both Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Only nine percent of countries in the Americas took an approach (p < 0.01 compared to Europe and Central Asia).

Among countries that guaranteed paid leave that could be used to meet children’s everyday health needs, the majority guaranteed working parents at least two weeks of paid leave to meet a five-year-old child’s health needs. Eight countries guaranteed less than a week of paid leave which may be insufficient for parents’ to adequately respond to the multiple routine illnesses young children typically have and meet preventive health care needs. In two of these countries (Brazil and Nicaragua), paid leave was limited to time to take children to a doctor’s appointment.

In some countries, parents had less paid leave to meet older children’s health needs than younger children’s. These differences were driven by two policy approaches. First, in some countries paid leave was only available for younger children. Second, even among countries that provided paid leave for all ages, some provided fewer days of leave for older children compared to younger. Only one country (Luxembourg) provided more leave for school-aged children (ages 4–12) than younger children (ages 0–3). Overall, only 16% of countries ensured at least 2 weeks of paid leave to meet a 15-year-old’s everyday health needs compared to 24% of countries for a 5-year-old ().

Table 1. Duration of paid leave available to meet a child’s everyday health needs by child age.

In most countries, the duration of paid leave for children’s everyday health needs was an entitlement to a set amount of leave per year. Hence, whether sufficient leave is available may depend on the number of children, disadvantaging families with more children compared to single child families if children are ill at different times. Ten countries that guaranteed paid leave for a 5-year-old’s everyday health needs took an approach to supporting the health needs of families with more children by guaranteeing a leave entitlement for each episode of illness, rather than a limit across the calendar year. For example, in Slovenia, employees can take 15 days off per event to care for an ill child aged seven or younger and seven days for older children. Only one country (Liechtenstein) that makes this form of episodic paid leave available sets the duration at less than a week. Another approach countries took to addressing the increased health needs of larger families was to provide separate leave entitlements for each child (Russia and Sweden) or to guarantee more leave to parents with multiple children than single child households (Germany, Norway, and Portugal).

Adequacy of the duration of leave available may also depend on the number of caregivers. In the majority of countries, leave is an individual entitlement. This structure of leave may encourage both parents to take leave in two-parent households. However, in the absence of other policies, individual entitlements can disadvantage single-parent households. Only five countries explicitly guaranteed additional paid leave to single parents. In four countries (Germany, Hungary, Israel, and Norway), single parents had double the allocation as each individual parent in a two-parent household. In the Czech Republic, single parents could take 16 days per episode of illness compared to 9 days for each parent in a two-parent household. In six countries, grandparents could also take paid leave for children’s everyday health needs. In four countries, leave is a family entitlement, rather than an individual entitlement. While this structure provides as much leave to single parents as two-parent households, research suggests that it may discourage gender equality in leave-taking (Boye, Citation2015; Eriksson, Citation2011).

Wage replacement rates for paid leave available to meet children’s everyday health needs were generally high with the majority countries that have paid leave guaranteeing a minimum wage replacement rate of 80% or more of wages. The lowest wage replacement rate was 50% of wages. In 10 countries, wage replacement rate varied, often ensuring workers with a longer employment history or more contributions received a higher wage replacement rate. Two countries provided a higher wage replacement rate to employees with larger families ().

Table 2. Wage replacement rate of paid leave available to meet children’s everyday health needs.

Adequacy of paid leave for serious health needs

Leave available for serious health needs was more common and generally longer than for everyday health needs. Whereas only a quarter of countries guaranteed at least two weeks of paid leave that could be used to meet a 5-year-old child’s everyday health needs, more than a third did so for serious health needs. However, while leave for serious health needs was generally longer, it may still be insufficient to meet serious health needs. Less than 20% of countries provided six weeks or more of paid leave which would be needed to support many more serious health conditions.

Fewer countries provided paid leave for serious health needs for older children than younger children. Among those that did, no country varied the duration of paid leave specifically available for children’s serious health needs with the age of the child ().

Table 3. Duration of paid leave available to meet children’s serious health needs by age of child.

A small number of countries made paid leave for serious health needs available only under limited circumstances. These include only for imminent death (1 country), for specific illnesses (1 country), during hospitalisation (2 countries), and for chronic illnesses (1 country). These limitations may make it more challenging for families to take leave when it is needed. An additional 12 countries limited paid leave to these circumstances, but also had separate entitlements to paid leave for everyday health needs. In 47 countries, there was no paid leave available specifically for children’s serious health needs, only leave available more generally for health needs (24 countries) or leave available for family needs, emergencies or discretionary reasons (23 countries).

The majority of leave entitlements were available each year to each worker. In three countries, leave specifically to respond to children’s serious illness was available as a shared family entitlement. In four countries, the leave entitlement was capped across the employee’s working life or the child’s lifetime. For example, in Japan, up to 93 days of paid leave can be taken by each parent or carer over the course of a child’s lifetime. Approaches specific to single parents or families with multiple children were the same for serious health needs as everyday health needs. Fourteen percent of countries had provisions that enabled grandparents to take paid leave available for children’s serious health needs, although some were limited to grandparents living in the same household as the child.

While wage replacement rates remained generally high for paid leave that can be used to meet children’s serious health needs, 5 countries did not tie payments to previous earnings and instead paid a flat rate or adjusted flat rate. In these countries, paid leave was available for an extended period of time (more than 26 weeks) to care for severely ill children ().

Table 4. Wage replacement rate of paid leave available to meet children’s serious health needs.

Adequacy of paid leave for the everyday and disability-specific health needs of children with disabilities

Compared to paid leave for serious health needs, fewer countries (39%) took an approach to ensuring paid leave for the everyday and disability-specific health needs of children with disabilities. In 15% of countries, there were separate leave entitlements explicitly for disability-related health needs alongside other forms of paid leave for children’s health needs. Only one country (Uruguay) made paid leave available specifically to care for children with disabilities without making other forms of paid leave available to meet children’s health needs more generally.

Disability-specific health leaves varied tremendously. In some countries, these separate leave entitlements are very short, but would support parents being able to attend on-going medical and therapy appointments. For example, in Estonia, parents of children with disabilities are entitled to one day of paid leave per month in addition to separate leave entitlements for both everyday and serious health needs. In other countries, these leaves are lengthy to support more intensive caregiving over a longer period. For example, in Croatia, parents of children with severe disabilities are entitled to take paid leave on a full or part-time basis until the child is eight years old.

Fewer countries guaranteed paid leave that could be used to meet the everyday and health-specific needs of older children with disabilities compared to younger children. Whereas nearly a third of countries guaranteed at least 2 weeks of paid leave that could be used to meet the everyday and disability-specific health needs of a two-year-old child with disabilities, less than a quarter of countries did so for a teenager with disabilities ().

Table 5. Duration of paid leave available to meet the everyday and disability-specific health needs of a child with disabilities by age of child.

Discussion

Nearly every country in the world guarantees paid leave to parents after the birth of a child (Heymann et al., Citation2017), but only a third of countries globally guaranteed paid leave that can be used to meet children’s everyday health needs. Caregiving for children does not end with infancy. These gaps in paid leave matter profoundly to individual children’s health, but also undermine countries’ ability to contain disease spread, whether gastrointestinal, seasonal illness, or during a pandemic, with economic costs to businesses and communities.

Globally, only half of the countries had paid leave policies in place to support parents caring for children with serious health needs and only 39% did so for children with disabilities. Even among countries that do have paid leave, it is often insufficient to support children with complex health needs. These gaps may put families in a precarious financial position during a time when economic security is needed the most and disproportionately jeopardise women’s economic opportunities. Paid parental leave has provided feasible models of how caregiving can be supported during lengthier periods of childcare and the benefits that providing workers with paid leave can have on health and economic outcomes (Heymann et al., Citation2017; Nandi et al., Citation2018).

For every type of leave examined, more leave was available for older children than younger: 17 countries guaranteed paid leave to meet everyday health needs for toddlers but not teenagers, 9 did so for serious health needs, and 12 for disability-related needs. While older children may require less supervision than younger children, parental presence is still needed at all ages to attend medical appointments and support better health outcomes. This is especially critical for children with serious health needs and disabilities who are more likely to require hands-on care.

To adequately support the health needs of all children, including those with disabilities or other complex health needs, parents need access to paid leave that can support shorter, but sometimes frequent, absences from work, as well as longer term leave in the less common event that their child requires lengthier treatment or care. These approaches are feasible in a range of different settings. While paid leave to meet children’s everyday health needs is most common in high-income countries, more than 1 in 4 low-income countries ensure that parents have at least two weeks of paid leave for these routine needs. Lengthier paid leave policies for serious health needs are found in 42% of high-income countries, but remain rare in low- and middle-income countries. However, if countries can afford paid parental leave after the birth of a child, they should be able to finance equally lengthy paid leave for the much smaller number of families dealing with the challenging problem of caring for a child with a serious health need.

The lack of sufficient paid leave for children’s health needs disproportionately impacts women’s economic opportunities. As countries seek to recover from the pandemic and build resilience for future pandemics, it is important that paid leave policies recognise caregiving needs beyond infancy and that these policies be structured in a way that supports gender equality in providing care and equality across families. The pandemic has disproportionately affected women’s employment opportunities (Carli, Citation2020), making it imperative that countries address gender inequalities in care that have long impacted economic opportunities and were exacerbated during the pandemic. Increasing wage replacement rates and allowing parents to alternate care responsibilities are two approaches that could support more equal care. Here too, innovations from parental leave that use incentives or other mechanisms to encourage both parents to take leave could also be considered. Similarly, while the majority of countries provide workers with separate entitlements to paid leave, few take explicit steps to ensure single parents can provide care for as long as a two-parent family would be able to. Addressing this gap is particularly important given the higher poverty rates for single parent households in countries around the world.

This analysis focuses on paid leave policies available to workers in formal employment. Future research should consider the approaches countries are taking to covering workers in informal, vulnerable, and gig employment. Similarly, this research focuses on legal rights to paid leave. While having a law on the books is a critical first step, previous research has found that a lack of awareness of policies may be a barrier to taking leave, particularly for low-income parents (Schuster et al., Citation2008), and retaliation, particularly for male caregivers, may also hinder taking leave (Rudman & Mescher, Citation2013). More research is needed to understand how these policies can be effectively implemented to ensure they reach all families. As part of understanding effective implementation, future research should also look at supportive policies that can work alongside paid leave policies to enable parents to balance their dual roles as workers and caregivers, such as flexible working hours or the right to request part-time work when more intensive care needs arise when caring for a child with a chronic condition or disability. Finally, little systematic research exists on the impact that paid leave laws have on children’s health outcomes and employment outcomes for parents. While compelling evidence exists to build the investment case for both paid parental leave and paid sick leave, paid leave for children’s health needs is comparatively understudied. Future research should look at the impact of these laws to support evidence-based policy decisions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 While Malta is classified as part of the Middle East and North Africa by the World Bank (WB), it is also a member of the European Union (EU) and therefore more likely to have legislation reflecting the EU’s principles and directives. Thus, we classified Malta as a part of Europe and Central Asia. All other countries retained their WB classifications.

References

- Ambrose, C. S., & Antonova, E. N. (2014). The healthcare and societal burden associated with influenza in vaccinated and unvaccinated European and Israeli children. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 33(4), 569–575. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-013-1986-6

- Anabwani, G., Karugaba, G., & Gabaitiri, L. (2016). Health, schooling, needs, perspectives and aspirations of HIV infected and affected children in Botswana: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Pediatrics, 16(1), 106. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-016-0643-5

- Asfaw, A., & Colopy, M. (2017). Association between parental access to paid sick leave and children’s access to and use of healthcare services. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 60(3), 276–284. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.22692

- Berdahl, J. L., & Moon, S. H. (2013). Workplace mistreatment of middle class workers based on sex, parenthood, and caregiving. Journal of Social Issues, 69(2), 341–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12018

- Boudet, M., Maria, A., Bhatt, A., Azcona, G., Yoo, J., & Beegle, K. (2021). A Global View of Poverty, Gender, and Household Composition. Policy Research Working Paper, 9553.

- Boye, K. (2015). Can you stay home today? Parents’. Occupations, relative resources and division of care leave for sick children. Acta Sociologica, 58(4), 357–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699315605161

- Carli, L. L. (2020). Women, gender equality and COVID-19. Gender in Management, 35(7/8), 647–655. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-07-2020-0236

- Castañeda, A., Doan, D., Newhouse, D., Nguyen, M. C., Uematsu, H., & Azevedo, J. P. (2016). Who are the poor in the developing world? In Policy research working papers. The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-7844.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020). Screening Students for Symptoms. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/schools-childcare/symptom-screening.html.

- Chai, Y., Nandi, A., & Heymann, J. (2018). Does extending the duration of legislated paid maternity leave improve breastfeeding practices? Evidence from 38 low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Global Health, 3(5), e001032. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001032

- Chai, Y., Nandi, A., & Heymann, J. (2020). Association of increased duration of legislated paid maternity leave with childhood diarrhoea prevalence in low-income and middle-income countries: Difference-in-differences analysis. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 74(5), 437–444. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2019-212127

- Choudhury, A., & Polachek, S. W. (2021). The impact of paid family leave on the timely vaccination of infants. Vaccine, 39(21), 2886–2893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.03.087

- Chung, P. J., Garfield, C. F., Elliott, M. N., Carey, C., Eriksson, C., & Schuster, M. A. (2007). Need for and use of family leave among parents of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics, 119(5), 5. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-2337

- Clemans-cope, L., Perry, C. D., Kenney, G. M., Pelletier, J. E., & Pantell, M. S. (2008). Access to and use of paid sick leave Among Low-income families with children. Pediatrics, 122(2), e480–e486. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-3294

- Coker, T. R., Thomas, T., & Chung, P. J. (2013). Does well-child care have a future in pediatrics? Pediatrics, 131(Suppl 2), S149–S159. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-0252f

- Colds in children. (2005). Paediatrics & Child Health, 10(8), 493–495. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/10.8.493

- Cousino, M. K., & Hazen, R. A. (2013). Parenting stress Among caregivers of children With chronic illness : A systematic review. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 38(8), 809–828. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jst049

- Daly, M., & Groes, F. (2017). Who takes the child to the doctor? Mom, pretty much all of the time. Applied Economics Letters, 24(17), 1267–1276. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2016.1270410

- Donkin, A., Goldblatt, P., Allen, J., Nathanson, V., & Marmot, M. (2017). Global action on the social determinants of health. 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000603.

- Earle, A., & Heymann, J. (2006). A comparative analysis of paid leave for the health needs of workers and their families around the world. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, 8(3), 241–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876980600858465

- Earle, A., & Heymann, J. (2011). Protecting the health of employees caring for family members with special health care needs. Social Science & Medicine, 73(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.016

- Earle, A., & Heymann, J. (2012). The cost of caregiving : wage loss among caregivers of elderly and disabled adults and children with special needs. Communi, 15(3), 357–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2012.674408

- Eriksson, H. (2011). The gendering Effects of Sweden’s gender-neutral care leave policy. Population Review, 50(1). DOI: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/433541#info_wrap

- Fernando, D., de Silva, D., & Wickremasinghe, R. (2003). Short-term impact of an acute attack of malaria on the cognitive performance of schoolchildren living in a malaria-endemic area of Sri Lanka. Transactions of The Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 97(6), 633–639. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0035-9203(03)80093-7

- Fong, M. W., Gao, H., Wong, J. Y., Xiao, J., Shiu, E. Y. C., Ryu, S., & Cowling, B. J. (2020). Nonpharmaceutical Measures for pandemic influenza in nonhealthcare settings — Social distancing measures. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 26(5), 976–984. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2605.190995

- Fong, V. C., Ms, C., & Iarocci, G. (2020). Child and family outcomes following pandemics : A systematic review and recommendations on COVID-19 policies. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 45(10), 1124–1143. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa092

- Force, L. M., Abdollahpour, I., Advani, S. M., Agius, D., Ahmadian, E., Alahdab, F., Alam, T., Alebel, A., Alipour, V., Allen, C. A., Almasi-Hashiani, A., Alvarez, E. M., Amini, S., Amoako, Y. A., Anber, N. H., Arabloo, J., Artaman, A., Atique, S., Awasthi, A., … Bhakta, N. (2019). The global burden of childhood and adolescent cancer in 2017: An analysis of the global burden of disease study 2017. The Lancet Oncology, 20(9), 1211–1225. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30339-0

- Gnanasekaran, S., Choueiri, R., Neumeyer, A., Ajari, O., Shui, A., & Kuhlthau, K. (2016). Impact of employee benefits on families with children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 20(5), 616–622. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315598891

- Hajizadeh, M., Heymann, J., Strumpf, E., Harper, S., & Nandi, A. (2015). Paid maternity leave and childhood vaccination uptake: Longitudinal evidence from 20 low-and-middle-income countries. Social Science & Medicine, 140, 104–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.07.008

- Heymann, J., Raub, A., Waisath, W., Mccormack, M., Moreno, G., Wong, E., Earle, A., Heymann, J., Raub, A., Waisath, W., Mccormack, M., Heymann, J., Raub, A., Waisath, W., Mccormack, M., & Weistro, R. (2020). Protecting health during COVID-19 and beyond : A global examination of paid sick leave design in 193 countries * Protecting health during COVID-19 and beyond : A global. Global Public Health, 15(7), 925–934. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1764076

- Heymann, J., Sprague, A. R., Nandi, A., Earle, A., Batra, P., Schickedanz, A., Chung, P. J., & Raub, A. (2017). Paid parental leave and family wellbeing in the sustainable development era. Public Health Reviews, 38(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-017-0067-2

- Huang, R., & Yang, M. (2015). Paid maternity leave and breastfeeding practice before and after California’s implementation of the nation’s first paid family leave program. Economics & Human Biology, 16, 45–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2013.12.009

- International Labour Organisation (ILO). (2018). Care work and care jobs for the future of decent work. In Care work and class: Domestic workers’ struggle for equal rights in Latin America. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094306114545742h.

- Jasper, C., Le, T. T., & Bartram, J. (2012). Water and sanitation in schools: A systematic review of the health and educational outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9(8), 2772–2787. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9082772

- Jou, J., Wong, E., Franken, D., Raub, A., & Heymann, J. (2020). Paid parental leave policies for single-parent households: An examination of legislative approaches in 34 OECD countries. Community, Work & Family, 23(2), 184–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2018.1517083

- Kearney, C. A. (2008). School absenteeism and school refusal behavior in youth : A contemporary review. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(3), 451–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.012

- Kuo, P. X., Volling, B. L., & Gonzalez, R. (2018). Gender role beliefs, work-family conflict, and father involvement after the birth of a second child. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 19(2), 243–256. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000101

- Li, S., & Leader, S. (2007). Economic burden and absenteeism from influenza-like illness in healthy households with children (5–17 years) in the US. Respiratory Medicine, 101(6), 1244–1250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2006.10.022

- Maume, D. J. (2008). Gender differences in providing urgent childcare among dual-earner parents. Social Forces, 87(1), 273–297. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20430857. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.0.0101

- Nandi, A., Hajizadeh, M., Harper, S., Koski, A., Strumpf, E. C., & Heymann, J. (2016). Increased duration of paid maternity leave lowers infant mortality in Low- and middle-income countries: A quasi-experimental study. PLOS Medicine, 13(3), e1001985. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001985

- Nandi, A., Jahagirdar, D., Dimitris, M. C., Labrecque, J. A., Strumpf, E. C., Kaufman, J. S., Vincent, I., Atabay, E., Harper, S., Earle, A., & Heymann, S. J. (2018). The impact of parental and medical leave policies on socioeconomic and health outcomes in OECD countries: A systematic review of the empirical literature. Milbank Quarterly, 96(3), 434–471. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12340

- O'Connor, S., Brenner, M., & & Coyne, I. (2019). Family - centred care of children and young people in the acute hospital setting : A concept analysis. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(17-18), 3353–3367. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14913

- Omidakhsh, N., Sprague, A., & Heymann, J. (2020). Dismantling restrictive gender norms: Can better designed paternal leave policies help? Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 20(1), 382–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/asap.12205

- Phelps, R. A., Pinter, J. D., Lollar, D. J., Medlen, J. G., & Bethell, C. D. (2012). Health care needs of children With Down Syndrome and impact of health system performance on children and their families. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 33(3), 214–220. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0b013e3182452dd8

- Pourabbasi, A., Shirvani, M. E., & Khashayar, P. (2012). Sickness absenteeism rate in Iranian schools during the 2009 epidemic of type A influenza. Journal of School Nursing, 28(1), 64–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059840511420262

- Principi, N., Esposito, S., Marchisio, P., Gasparini, R., & Crovari, P. (2003). Socioeconomic impact of influenza on healthy children and their families. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, 22(10), 2001–2004. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.inf.0000092188.48726.e4

- Raub, A., Earle, A., Chung, P., Batra, P., Schickedanz, A., Bose, B., Jou, J., Chorny, N. D. G., Wong, E., Franken, D., & Heymann, J. (2018). Paid leave for family illness: A detailed look at approaches across OECD countries. UCLA World Policy Analysis Center.

- Roser, K., Erdmann, F., Michel, G., & Winther, J. F. (2019). The impact of childhood cancer on parents’ socio-economic situation - a systematic review. Psycho-Oncology, 28(6), 1207–1226. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5088

- Rudman, L. A., & Mescher, K. (2013). Penalizing Men Who request a family leave: Is flexibility stigma a femininity stigma? Journal of Social Issues, 69(2), 322–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12017

- Schuster, M. A., Chung, P. J., Elliott, M. N., & Garfield, C. F. (2009). Perceived effects of leave from work and the role of paid leave Among parents of children With special health care needs. American Journal of Public Health, 99(4), 33–35. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.138313

- Schuster, M. A., Chung, P. J., Elliott, M. N., Garfield, C. F., Vestal, K. D., & Klein, D. J. (2008). Awareness and use of California’s paid family leave insurance among parents of chronically Ill children. JAMA, 300(9), 1047–1055. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.300.9.1047

- Seixas, B. V., & Macinko, J. (2020). Unavailability of paid sick leave among parents is a barrier for children’s utilization of nonemergency health services: Evidence from the National Health Interview Survey. International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 35(5), 1083–1097. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.2988

- Shepherd-Banigan, M., Bell, J. F., Basu, A., & Booth-laforce, C. (2017). HHS public access. Medical Care Research and Review, 74(2), 208–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558716634555.Mothers

- Sigurdsen, P., Berger, S., & Heymann, J. (2011). The Effects of economic crises on families caring for children: Understanding and reducing long-term consequences. Development Policy Review, 29(5), 547–564. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2011.00546.x

- Tanaka, S. (2005). Parental leave and child health across OECD countries. The Economic Journal, 115(501), F7–F28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0013-0133.2005.00970.x

- Thévenon, O., Manfredi, T., & Govind, Y. (2018). Child poverty in the OECD : Trends, determinants and policies to tackle it. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, 218.

- UNICEF. (2021). COVID-19 and School Closures: One Year of Education Disruption. https://data.unicef.org/resources/one-year-of-covid-19-and-school-closures/.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2019). Defeating Meningitis by 2030: baseline situation analysis.