ABSTRACT

Research within the context of sex work is challenging. The nature of the subject matter and stigma that surrounds sex work has often privileged a homogenous, academic practice of generating knowledge. Based on the lessons and experiences of an existing sex work programme and a recently completed national public health study with female sex workers (FSWs) in South Africa, we aim to highlight the significance and successes of privileging a bottom-up, community centric approach to the design, data collection, and knowledge generation. A FSW programme provided extensive peer educator skills training and learning opportunities. Lessons were applied to the implementation of a national study on FSW across South Africa. Planning workshops with community members and sites and pre- implementation training of all site staff was undertaken. 3005 FSWs were successfully enrolled and surveyed by their peers, over 6-months. Researchers have a lot to learn from community members and should remain vigilant to the power dynamics that their privilege creates throughout the research process. Those seeking to generate knowledge should practice meaningfully engagement and include population members on the study team in roles that allow them to proactively contribute to the process and create knowledge.

Background

Within the field of health, community participation is viewed as one of the primary principles of health promotion and has the potential to empower individuals, build new and strengthen existing networks, and bring about meaningful change (Cock, Citation2006). By drawing on local knowledge, experience and providing a trusting space that enables meaningful collaboration, community-based engagement empowers local communities to access healthcare resources based on their own perceived needs and solutions (Andrews & Turner, Citation2006; Rifkin, Citation1996). However, community participation has not been as readily adopted within the bio-medical and quantitative research field when compared to the social sciences.

Bio-medical interventions that have attempted to adopt a community centric approach to research have at times taken for granted the meaning of the terms ‘community’, ‘engagement’ and ‘participation’, assuming them to be inherent in community-based interventions or the inclusion of a community advisory board (CAB). The failure to define who is meant by the term community, expectations of engagement and the level of necessary participation can lead to the exclusion of some individuals thus compromising the overall impact of the health intervention (Cleaver, Citation2001). Additionally, existing bio-medical research has traditionally privileged a pragmatic, objective, quantitative approaches to knowledge generation. This approach places research-produced knowledge front and centre of the study process and is predicated on a system of power differentials whereby participant voices throughout the research journey are infrequently, nor meaningfully considered. Such epistemological systems of knowledge generation traditionally assumed a linear causal relationship, that science is objective, and the power of generating information lies in the hands of the scientist or researcher at the expense of communities and the context within which they are based. The systems of data collection often privilege the researcher voice, be it through the manner in which study objectives are conceptualised, the tools used to gather data, the interpretation of data made outside of a community gaze or how these advantage institutional needs. However, we (the authorship team) believe that knowledge creation should be done through acknowledging the subjectivity inherent in research working with people: our curiosities preceding the research questions, the methodologies we select and the questionnaires we include.

The manner in which bio-medical research has traditionally been conducted has excluded the perspectives and experiences of vulnerable and often overlooked key populations. Specifically, the National Research Council (US) (Citation2011) defines bio-medical research as the study of human physiology and the understanding, prevention and treatment of diseases. This definition does not account for the fundamental impact of society on disease progression, individual automony and privilages an academic process of knowledge generation. More recently, bio-medical research has introduced community advisory boards (CABs) in an attempt to ensure community representation (Fregonese, Citation2018). This has been strongly driven by regulatory and funding agencies. However, the manner in which some CABs are imported into research the needs and experiences of key populations are overlooked. One such primary group are sex workers. In South Africa, female sex workers (FSWs): have a high burden of HIV (Coetzee, Jewkes, & Gray, Citation2017; UCSF, Anova Health Institute & WRHI, Citation2015) around which much of the global literature centres. They have also suffered extreme levels of violence from clients, police, intimate partners and other men (Coetzee, Gray, & Jewkes, Citation2017; Fick, Citation2006; SWEAT, Citation2011), have experienced severe stigmatisation and discrimination based on their vocation (Coetzee et al., Citation2018; Richter et al., Citation2014; Wojcicki, Citation2002; Wojcicki & Malala, Citation2001) and struggle to access non-judgemental healthcare services, have challenges accessing childcare facilities during their working hours and many suffer from mood and anxiety disorders (Coetzee et al., Citation2018; Jewkes, Milovanovic, et al., Citation2021). Female sex workers have been reported to have poor linkage and retention in care thus compromising their overall safety and physical and emotional wellbeing (Lancaster et al., Citation2016). Additionally, existing sex work interventions have focused primarily on HIV health indicators often at the expense of the individual’s lived experiences.

Key enabling factors that influence female sex worker retention in care include community mobilisation, peer-to-peer support, and non-judgemental, sensitised health staff (Blanchard et al., Citation2013; Zulliger et al., Citation2015). Over the course of four decades and through the civil pursuit towards a collective objective, community mobilisation has become a key facet of HIV prevention and treatment programmes (Parker, Citation1996). Work conducted by George et al. (Citation2015) highlights the significance of focusing on structural sources of HIV risk and not only the individual behavioural indicators. While the Mbeki-era in South Africa’s public health history is defined by AIDS denialism, the community mobilisation approach -underpinned by the support of South Africa’s rights-based constitution and the strong efforts by the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) and other human rights groups – was fundamental in ensuring access to healthcare services (Heywood, Citation2004). Within sex work communities, mobilisation began in the mid 90’s under the guidance of the Sex Worker Education and Advocacy Taskforce (SWEAT). Although less than 1% of global funding (Kristof & Wudunn, Citation2010) is channelled to sex worker programming (which decreased from 2020 onwards due to funding constraints resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic), South Africa has made a concerted effort to implement community mobilisation HIV programmes. These services have influenced social change by creating awareness of existing health challenges within the sex work sector, collaboratively developing interactive processes and building a safe community space where members would feel empowered to act for one’s own health. Despite the impact of the community mobilisation approach in South Africa, sex worker programmes for HIV related services, operating with the ambient of bio-medical interventions, have often inadvertently reduced the sex worker to a vector of disease and programmes have been ill equipped to address the diverse needs of the population beyond HIV.

For the quantitative researcher interested in collaborating with sex workers there are many challenges that need to be traversed. These include: the size of the sex worker community are often unknown; homogenous definitions of sex work are often applied to a diverse sector with many differences in age, race, class and nationality; and due to the stigmatised nature of the work, issues around confidentiality and privacy need to be considered (Nencel, Citation2017; Shaver, Citation2005).

Despite these challenges, it is imperative that academics adopt inclusive and participatory research methodologies with key populations to ensure that the knowledge produced leads to change (Nencel, Citation2017). Such work has been led by organisations such as AIDSFONDS (Citationn.d.) who privilege a localised, community implemented solution through empowering partner organisations. Additionally, much of the key sex work research has been produced by social scientist who have qualitatively explored experiences and perceptions and challenged common notions of knowledge production.

We aim to describe the lessons derived from our programmatic experiences of working with female sex workers in South Africa and how these lessons then influenced our research with sex work populations. Additionally, we will relate how we co-create and co-share knowledge, within the ambient of an adapted bio-medical research approach, with the sex work community to ensure a respectful, feasible and trusting collaboration.

Methods

In 2013, we established a sex worker programme to sit within an existing public health research organisation with a strong bio-medical focus on HIV treatment and prevention. The programme was located in the largest suburban township, South East of Johannesburg. A predominantly urban and peri-urban, low-income location, the area has the highest population density in South Africa, is home to 43% of residents from the City of Johannesburg and houses approximately two million people. The area has around 3000 (legal and illegal) drinking establishments (Coetzee, Jewkes, et al., Citation2017). Up to this point, the sale of sexual services had been considered to take place predominantly within formalised venues such as brothels, strip clubs and along certain streets, or in mining communities (Campbell, Citation2000), but not extensively within a suburban Township setting. Prior to the programme implementation, there were no sex work specific, or sensitised healthcare services available, needs-based linkage-to-care, and no community mobilisation of the sector in this area. Having previously worked on research with sex workers in Johannesburg we felt that the presence of extensive formal and informal drinking venues, coupled with low levels of education and high unemployment meant that ‘sex for gain’ transactions – be they formal or informal, were likely to be a prominent feature of the landscape.

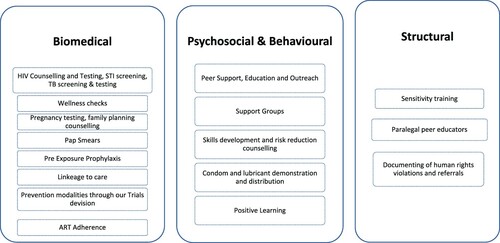

Thus, we began the process of setting up a health programme for female sex workers, drawing on a peer-to-peer support model, commonly used in HIV prevention work amongst female sex workers (REF). The established programme was funded to offer an initial range of biomedical services including: HIV counselling and testing, wellness checks, linkage to care, condom and lubricant distribution, further supplemented by peer support, education and outreach. After some time engaging with the community, the programme was adapted to provide community-initiated interventions focusing on contextual structures such as documentation of human rights violations and paralegal assistance. Structural interventions provide a strong approach to HIV prevention by focusing on contextual factors of risk over individual behavioural factors (REF). In line with changes to HIV treatment guidelines and with the introduction of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), the programme adapted to provide services to female sex workers, including the intimate partners of sex workers to encourage adherence. illustrates the variety of services offered by the programme.

During the nine years that the programme ran, there were many incredible lessons learnt, and insights gained into the lives of women who engage in ‘sex work’. These lessons heavily influenced our approach in engaging with sex worker communities and the manner in which we think about, develop and implement research. Since starting the programme, it has facilitated eight research studies. Herein we draw heavily on the lessons learnt in relation to the development, implementation and interpretation of the first national level sex worker study conducted in South Africa (Milovanovic et al., Citation2021). Below we describe some of the pivotal lessons that had resulted in meaningful programmatic and research change within the context of our work – our descriptions move fluidly between both programme and research, as lessons apply across both as they influenced one another.

Defining the community

The area in which the programme was established did not comprise of formal commercial sex work-type venues, and no mobilisation had previously been done. While our funding was to run an HIV programme for sex workers, as we began to embed the programme within the community, and build trust it rapidly became apparent that women who sold sex in the area that our programme covered did not refer to themselves as a ‘sex worker’. In fact, they proactively avoided all potential associations with ‘ladies of the night’, ‘prostitutes’, or ‘magosha’ (a derogatory term to describe women who sell sex). Respecting their experienced and how they chose to define themselves was fundamental to our project. Furthermore, as highlighted by Nencel (Citation2017) the term sex worker does not necessarily encompass all sex workers interests. Thus, understanding how sex work took place in this Township and who our use of the term ‘community’ included were fundamental.

Despite our research specifically only focusing on cis female sex workers, our programmatic efforts taught us that the term ‘community’ was defined by additional factors including: geolocation, the type of venue where sex was sold, and the frequency with which the women engaged in sex for cash transactions. Both programmatically and from our research, it became apparent that each of these factors influenced exposure to violence, alcohol consumption, mental wellbeing, family relations, and many more aspects. We drew on a number of stakeholders to guide our work in defining the community that we served, and allowing the community to evolve or expand this definition in line with their changing contextual dynamics. These meant listening to: the women themselves, advocacy groups, establishment owners, clients, police, public sector healthcare workers, and at times their surrounding communities who often took umbrage at sex being sold in the area. Our work required a subtlety to it both to engage the women, while not drawing attention to the general sector as sex work is still criminalised in South Africa. Through this steep learning curve on how to engage the Township sex work community, what became apparent was that sex work is a set of behaviours used by science to describe a population group, it is not a person, and cannot define their humanity nor their lived experiences. In considering sex work to function along a continuum of behaviours rather than a blanket occupation, we became empowered to understand the individual nuances seen within and between sex work programmes, and to bring a greater humanity into our projects. Further, it allowed our research and programme to adapt or consider this continuum in ensuring we reached persons who may otherwise have fallen through gaps caused by fixed definitions that may not have been contextually sensitive, or have considered identity management strategies used by marginalised populations.

The conscious decision to look at individuals who engage in a pattern of behaviour around their vocation has heavily influenced our research and knowledge creation. It allowed us the freedom to use community knowledge-bases to influence how we structured our scientific endeavours, and has allowed for better results in both spheres of work. It has truly humanised the population within a traditionally HIV bio-medical sphere. We have acknowledged the broader needs of the population – which oftentimes supersede our HIV agenda – and in doing so can tailor our work appropriately. Knowledge generation has become a collective activity, with the voices of sex workers being privileged in relation to their lived experiences and the realities of the industry – thus the majority of our team have or do work in the sex work industry.

The importance of language

In an effort to empower the team to better understand the importance of collecting accurate information while on outreach, all peer educators were provided basic computer literacy training. One of our team members, 53-year-old women with less than 4 years of primary education, and limited English literacy, was highly resistant to the training. The first few training sessions were conducted in English, and her responses indicated a disconnect from the content and a resistance to the process – frankly, she was quite angry at being tasked with developing computer skills. In an effort to re-engage the team member, alternative training sessions were organised which were conducted in Zulu, her first language. The reengagement with the training content improved and about a week after the Zulu language training sessions our team member arrived on site with a computer. When questioned about the desktop, she stated that she had organised an additional device in order to practice and improve her computer literacy. By shifting our heteronormative methods of academic training from English to a more suitable language of communication we had provided a space within which individuals could feel included and comfortable to engage and learn new skills. Additionally, our team member expressed immense pride in herself and her new skill set. This was a significant lesson in potential and empowerment within the context of what is often a challenging project to run.

Our research projects leveraged this learning, through not privileging English as the dominant discourse for training, allowing staff to translate between languages and hold discussions in multiple languages. Interviews were conducted in multiple languages, with translations and back translations being overseen by community members to ensure consistency between meanings. Cognitive interviews were undertaken to ensure the reliability of translated questionnaires. Care was also taken to assess questionnaire validity between languages during analyses through various sensitivity analyses being conducted.

Peer-on-peer HIV testing

Outreach services, education and commodity distribution were key funded, peer-support services. An additional critical indicator for the programme was HIV testing services. While the initial testing targets were not excessive (two digit figures), our team found it challenging to ensure a successful referral for HIV testing. In the beginning of the programme, HIV testing was done through a partner project or a primary healthcare facility. This meant that HIV testing was done by a person with no understanding of the dynamics in selling sex, and counselling was predicated on the standard assumptions of a heteronormative, single partner relationship, abstinence, and condom use. The community shared their desire to be HIV testing by peers, who would understand the dynamics of sex work, and be able to provide a non-judgemental service while simultaneously sharing relevant health knowledge. As a result, we trained two staff members in HIV counselling and testing services. Our programme adapted the HIV counselling and testing provided to account for the lived experiences of the community of sex workers that we served thus responding to their needs. We developed a feedback loop between peers, community and programme team members. Rather than reinforcing feedback such as only having one sex partner and assuming condom use was easy to negotiate, we suggested alternative methods to encourage clients to wear a condom, and informing them that certain sex positions were riskier than others as a male client could remove or break the condom without her seeing it. Our counselling messaging was predicated on real life scenarios and not on an ideological and moral debate around number of sexual partners, and who controls women’s bodies.

Where previously we had only managed to test a total of 12 women in 6 months, within four weeks of implementing our peer-on-peer strategy we had tested over 38 women, and consistently managed to exceed our monthly targets during the first phase of our funding. The trust built through this intervention has enabled us to implement HIV testing during research projects, with a 100% uptake of both the testing and obtaining results. Further, we only use peers from each community -capacitated in counselling and interview skills – undertake all interviews. Considering that sex work research is highly politicised (Nencel, Citation2017) we recognise that without a community-centric approach where our work is imbedded within the community, we would neither have achieved the funder targets, nor have been able to co-create knowledge through research on HIV prevalence and other related factors.

Mental health matters – even when you are a peer educator

Peer educators in ‘sex work’ programmes are often the first responders to violence exposure by women. Not only have they themselves been exposed to high levels of violence across their lifetime, but they are expected to innately know how to deal with violence in the communities that they work. However, in the early days of the programme, an assumption was made that peer educators would not be affected by work related exposure to violence, and not be emotionally triggered due to their own experiences. Through carefully observing and discussing with our team of peers, we were able to understand the challenges they were facing both personally and professionally, relating to past, current and vicarious trauma.

In response, we implemented an 8-week, lay psychosocial training for all peer educators. Training was geared to move the peers towards a counselling mindset. Thus, enabling them to better probe for information, allow them to contain for women in the programme who had experienced trauma, and to empower them in their own lives towards a healthier sense of wellbeing. We knew the training would be important to facilitating the containment of programme attendees, but we underestimated the value it would add on a personal level.

One of our younger team members was a really challenging woman to work with. She was very aggressive and could be quite divisive in the programme. Despite a number of unsuccessful in house interventions, we did not anticipate that she would continue with her position for much longer. Mid way through the counselling training, we met with the facilitator and asked who she thought our really skilled counsellors were. She highlighted our problematic young peer. Through the training provided, this peer had developed skills to help contextualise and contain her own emotional anguish while also learning how to support others without internalising their emotions.

The primary lesson learnt was the necessity to ensure that programmatic (and research) staff are equipped to deal with complex events that have the potential to trigger past experiences thus impacting on their daily work. Despite peer educators frequently being the first responders to violence, their wellbeing has traditionally been an afterthought. Since the first psychosocial training, our programme has continued to provide annual sessions to team members, helping not only to retain a healthy staff compliment, but seeing greater commitment to the programme. Additionally, our programme was equipped to provide regular debriefing sessions for peers to assist them with coping with any vicarious trauma. Our responsiveness to the needs of our peers has resulted in a far richer knowledge co-creation experience for us. Peers are as committed to the programme and its participants, as the non-sex work researcher staff are to ensuring peer wellbeing. Thus they proactively engage and offer insights into our research projects.

Translating programme learnings into meaningful community-centric research

While we had experimented with some community focused approaches to research between 2013 and 2018, it was only in 2019 that we were able to take our learnings to scale. Our lessons had taught us that successful research collaborations with the community were predicated on giving back to the community through programme interventions. Thus, our work has focused on embedding research projects within or alongside supportive community-focused interventions. Through the support of both a local and an international funder, we embarked on the first national study of HIV prevalence, incidence and drug resistance, violence exposure, and mental ill health amongst women who sold sex across 12 programmes and all nine provinces of South Africa (Milovanovic et al., Citation2021). This was the first project in South Africa that aimed to enrol participants from less researched areas in the country with the aim of garnering a broader understanding of different sex work contexts. Our project aimed to use a meaningful community centric approach to quantitative bio-psychosocial research – from design through to implementation. Furthermore to leverage HIV related funding, to unpack a much broader scope of need and vulnerability in the community.

Community engagement began early in the project. We leveraged community workshops and safe spaces at our existing programme in Johannesburg (described above), where we were able to put forward suggestions and actively listen to feedback from the sex worker communities and peer teams. From understanding the varying needs of the different communities and their unique complexities, we were better equipped to develop specific aims that were responsive to the sex worker communities (while remaining within the ambit of the funding mechanism). Despite our focus on HIV, HIV drug resistance and other related bio-medical outcomes we were more empowered to describe, in detail, the lives of the sex worker participants than has traditionally been done with bio-medical HIV focused studies. This was achieved through the adaptation of the data collection tool to allow for the capture of participant narratives.

In defining a sex work community for the research study to work with, we were able to strategically understand the nuances inherent across the broader population, and to spearhead interventions in South Africa that targeted less formal types of sex work. We were also able to bring to light a broader understanding of informal sex work, and how through only focusing on commercial sex workers, we miss the opportunity to help people who engage in informal sex work. We also then have the ability to create knowledge through a broader and more comprehensive inclusion of women engaging in sex work.

Community members from all nine provinces were brought to the core site for an interactive, and reflective input session. We aimed to understand the questions pertinent to each site in supporting their existing sex work programmes, and to improve our study survey tool. The workshop was run through a series of feedback sessions, where every persons’ voice was privileged by using individual post-it notes for feedback, followed by a group discussion where we actively tried to engage with each person present. The session was important in helping us learn about the needs of other communities of women engaging in sex work from across the country without making assumptions or enforcing standardised views. Feedback from the session was used for the first adaptation of the survey tool.

The survey tool was developed and finalised through a community engagement process, including feedback sessions, cognitive interviews, and discussion groups. What began with 1500 suggested questions was rapidly consolidated to a set of 450 questions covering: detailed demographics, childhood, and pregnancy questions, sexual behaviours and risk, violence exposure, stigma and discrimination, mental wellness, employment and HIV related questions. Every question included was thoroughly examined to ensure its relevance across all sites. Adaptations were made so that translated questions continued to carry the same meaning and resonated with the challenges being faced by the population. For example, extensive questions were asked about violence exposure, some of which were used in earlier sex work studies. During a cognitive interview in 2016 to understand how best to ask questions on violence exposure, it became apparent that women were experiencing regular rape by intimate partners. The question we were testing came from the WHO violence against women questionnaire, ‘in the past year, how many times [have you been raped by your intimate partner] has this happened’ (World Health Organisation, Citation2002). The response we received reflected a horrific reality. During this process a participant had reported that her partner raped her at least once a week. On probing it became evident that this has been ongoing for the past 9 months since he had lost his employment, but it stopped once he regained employment. She even reflected that he stopped raping her because he felt more powerful when he was employed.

The development of a comprehensive and responsive questionnaire was the initial step however, ensuring the capture of lived experiences was equally as imperative. To do this, we needed a database that allowed for narratives to be recorded, and for staff to share the stories they were hearing. This process of data capturing was the starting point for staff debriefing. The online REDCap data capturing system (Harris et al., Citation2009) was designed to be simple and user friendly so that persons with limited technical abilities would be able to engage with it. The database was adaptable enough to accommodate multiple languages, set out in such a way that it was mobile friendly, intuitive and uncomplicated to complete, and allowed peer interviewers to capture longer narratives where necessary.

Peer interviewers were the backbone of our national study teams as they were intimately connected to the communities that they work with, and have personal experience in selling sex and engaging with sex workers. We provided two weeks of training to 25 peer educators, to upskill them to be able to conduct research data collection. The training included lay psychosocial support, trauma containment and debriefing, ethics in research, the study protocol, data collection and data use.

We conducted a training session with all peer interviewers from the 12 sites in the national study (Milovanovic et al., Citation2021) in order to obtain feedback on the layout of the database. Aspects such as which side of the screen the questions should be displayed compared to where the response sets were positioned helped the teams improve their ability to complete the survey. Whether response sets were listed one under the other, or in a dropdown menu or listed alongside each other was critically important to the peer interviewers. Their opportunity to provide meaningful insights and to see the core research team immediately include their feedback into the database structure helped build buy-in to the study.

It was imperative to ensure that our study peer interviewers were appropriately equipped to ask the difficult questions in a compassionate manner while also being able to contain for participants discussing experiences of violence. Simultaneously, peer interviewers needed to be helped to contain their own emotions during the research process and ensure psychological wellbeing.

Successful implementation

The national study aimed to enrol 3000 female sex workers with the objective achieved within a period of 6 months (January–July 2019). Our overall screening failure percentage was only 1.7%, with 3% missing data of which majority was related to missing laboratory specimens and/or results. This is notably less when compared to other studies where the screening failure rate was 12.9% (Coetzee, Jewkes, et al., Citation2017). We believe that engaging the sex work communities across the different sites and inviting peer educators to be part of the study teams was fundamental to obtaining buy-in and commitment to the study. The study findings were shaped by the manner in which the research was developed. This is reflected in the reported differences found across the sites. These differences highlight that a homogenous, one size fits all approach, is not appropriate when considering developing programmatic resources for vulnerable populations.

Discussion

Our experiences in running a female sex worker health programme provided an opportunity to learn pertinent lessons that were successfully applied to the conceptualisation, development and implementation of our national research study. They highlight the importance of embedding both programme and research within the community in order to enrich outcomes.

The manner in which the research was enacted created a space whereby the study outputs were driven by community perceived needs. This is in line with existing literature whereby participating members of the sex worker communities are empowered to gain mastery over their circumstances through the process of participating (Campbell & Jovchelovitch, Citation2000). However, while we would like to believe that the process was a positive and engaging one for the study participants, our inability to change their life circumstances, including their exposure to violence (Jewkes, Milovanovic, et al., Citation2021; Jewkes, Owtombe, et al., Citation2021)) and the continued criminalisation of the profession (Coetzee et al., Citation2018; Coetzee, Jewkes, et al. Citation2017; Huschke & Coetzee, Citation2019) remains a massive limitation to all research on marginalised populations. Further, the power dynamics created through traditional research methods are to some extend mitigated by simulating a more equitable environment. This said, it is important to acknowledge that collaboration, and working together to create knowledge is complex and does not do away with all the tensions, and differences of traditional researcher-participant dynamics. Rather the dynamics are shifted, with power being expressed in novel ways by peer interviewers and communities alike.

In general, research that aims to adopt a community-centric approach applies a blanket assumption to the word ‘community’. However, based on our work, it was imperative to determine when talking about a community which network was specifically being referred to and whom the process of generating knowledge would benefit and who would be excluded from the narrative (Dempsey, Citation2010; McEwan, Citation2003). While our national study focused on female sex workers as the primary population, the 12 sites all represented varied sex worker communities with differing health needs. Additionally, it was essential for us to be able to balance funder needs (often target focused outputs) in the process while ensuring these did not drown-out participants and peer voices during the co-creation of the research project.

By using peer educators to provide health services as part of the programme and upskilling them to peer interviewers as part of research, we hope to facilitate a process whereby community members would utilise their existing knowledge and experiences. Thus, leading to the sustainability of services provided across the programmes, inclusion and participation in the decision-making processes, and the creation and uptake of opportunities to build new skills (Rifkin, Citation1996).

While we have focused on the positive aspects of this research approach, it should not be romanticised as being infallible, or easy to implement. There are risks with approaching co-creation of knowledge in this way, and these need to be carefully thought through and planned for. Strong oversight mechanisms have to be put in place and the core team need to be able to proactively monitor data and respond real-time to any concerns. In an effort to speed-up the survey completion, we discovered that some peer interviewers were guessing participants responses. This resulted in fraudulent data being generated which put in disrepute previously collected survey responses. The lesson was a hard one and led to previous data being excluded. However, the incident was used to improve processes in the research project and as a positive learning experience for all sites. We believe the rewards outweigh threats to reliability and data integrity, which can be mitigated against through a strong training programme, and ongoing intensive support.

Our experiences have highlighted the potential inherent in each person, irrespective of their level of education or current vocation. Tradition modes of researchers have a lot to learn from including community members as part of the research process. In order to successfully overcome inequalities, the development of health interventions have to adopt a community focused from approach that allows space for the sharing of aspirations, and ideas. Those seeking to adopt a truly empowering process, should practice active engagement by providing a space for clearly defined populations to meaningfully partake in different roles that allow them to contribute to the knowledge generation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- AIDSFonds. (n.d.). Young, wild and … free? Change story: Kenya. A youth-centred approach to increasing access to mental health and socio-economic support for young people who use drugs. AIDSFONDS. https://aidsfonds.org/assets/resource/file/0385_YWF%20BTG%20Kenya%20MEWA_PWUD.pdf

- Andrews, R., & Turner, D. (2006). Modelling the impact on community engagement on local democracy. Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit, 21(4), 378–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/026909406009519556

- Blanchard, A. K., Mohan, H. L., Shahmanesh, M., Prakash, R., Isac, S., Ramesh, B. M., Bhattacharjee, P., Gurnani, V., Moses, S., & Blanchard, J. F. (2013). Community mobilization, empowerment and HIV prevention among female sex workers in south India. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 234. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-234

- Campbell, C. (2000). Selling sex in the time of aids: The psycho-social context of condom use by sex workers on a Southern African mine. Social Science and Medicine, 50(4), 479–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00317-2

- Campbell, C., & Jovchelovitch, S. (2000). Health, community and development: Towards a social psychology of participation. Journal of Community and Applied Social Science, 10(4), 255–270. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/index.html. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1298(200007/08)10:4<255::AID-CASP582>3.0.CO;2-M

- Cleaver, F. (2001). Institutions, agency and the limitations of participatory approaches to development. In B. Cook, & U. Kothari (Eds.), Participation: The new tyranny? (pp. 36–55). Zed Books.

- Cock, J. (2006). Public sociology and the social crisis. South African Review of Sociology, 37(2), 293–307. http://www.swopinstitute.org.za/files/pubsoclSoclcrisis_jcock.pdf. https://doi.org/10.1080/21528586.2006.10419159

- Coetzee, J., Buckley, J., Owtombe, K., Milovanovic, M., Gray, G. E., & Jewkes, R. (2018). Depression and post traumatic stress amongst female sex workers in Soweto, South Africa: A cross sectional, respondent driven sample. PlosOne, 13(7), e0196759.

- Coetzee, J., Gray, G. E., & Jewkes, R. (2017). Prevalence and patterns of victimization and polyvictimization amongst female sex workers in Soweto, a South African township: A cross sectional, respondent driven sampling study. Global Health Action, 10(1), 1403815. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2017.1403815

- Coetzee, J., Jewkes, R., & Gray, G. E. (2017). Cross-sectional study of female sex workers in Soweto, South Africa: Factors associated with HIV infection. PloS One, 12(10), e0184775. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184775

- Dempsey, S. E. (2010). Critiquing community engagement. Management Communication Quarterly, 24(3), 359–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318909352247

- Fick, N. (2006). Sex workers speak out: Policing and the sex industry. SA Crime Quarterly, 15, 13–18. https://doi.org/10.10520/EJC47564

- Fregonese, F. (2018). Community involvement in biomedical research conducted in the global health context; what can be done to make it really matter? BMC Medical Ethics, 19(Suppl 1), 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-018-0283-4

- George, A., Blankenship, K. M., Biradavolu, M. R., Dhungana, N., & Tankasala, N. (2015). Sex workers in HIV prevention: From social change agents to peer educators. Global Public Health, 10(1), 28–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2014.966251

- Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Thielke, R., Payne, J., Gonzalez, N., & Conde, J. G. (2009, April 1). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

- Heywood, M. (2004). The price of Denial. Development update: From distaster to development. HIV and AIDS in Southern Africa. http://section27.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/Price-of-Denial.pdf

- Huschke, S., & Coetzee, J. (2019). Sex work and condom use in Soweto, South Africa: A call for community-based interventions with clients. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 1, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2019.1568575

- Jewkes, R., Milovanovic, M., Otwombe, K., Chirwa, E., Hlongwane, K., Hill, N., Mbowane, V., Matuludi, M., Hopkins, K., Gray, G., & Coetzee, J. (2021). Intersections of sex work, mental ill-health, IPV and other violence experienced by female sex workers: Findings from a cross-sectional community-centric national study in South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 11971. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211971

- Jewkes, R., Otwombe, K., Dunkle, K., Milovanovic, M., Hlongwane, K., Jaffer, M., Matuludi, M., Mbowane, V., Hopkins, K. L., Hill, N., Gray, G., & Coetzee, J. (2021). Sexual Ipv and non-partner rape of female sex workers: Findings of a cross-sectional community-centric national study in South Africa. SSM – Mental Health, 1, 100012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2021.100012

- Kristof, S. D., & Wudunn, S. (2010). Half the sky: How to change the world. Hachette Digital, UK.

- Lancaster, K. E., Cernigliaro, D., Zulliger, R., & Fleming, P. F. (2016). HIV care and treatment experiences among female sex workers living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. African Journal of AIDS Research, 15(4), 377–386. https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2016.1255652

- McEwan, C. (2003). ‘Bringing government to the people’: Women, local governance and community participation in South Africa. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 34(4), 469–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/50016-7185(03)00050-2

- Milovanovic, M., Jewkes, R., Otwombe, K., Jaffer, M., Hopkins, K., Hlongwane, K., Matuludi, M., Mbowane, V., Gray, G., Dunkle, K., Hunt, G., Welte, A., Kassanjee, R., Slingers, N., Vanleeuw, L., Puren, A., Kinghorn, A., Martinson, N., Abdullah, F., & Coetzee, J. (2021, January 1). Community-led cross-sectional study of social and employment circumstances, HIV and associated factors amongst female sex workers in South Africa: Study protocol and baseline characteristics. Global Health Action, 14(1), 1953243. PubMed PMID: 34338167; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8330713. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2021.1953243

- National Research Council (US). (2011). Committee to study the national needs for biomedical, behavioral, and clinical research personnel. Research training in the biomedical, behavioral, and clinical research sciences. National Academies Press (US), Basic Biomedical Sciences. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK56989/

- Nencel, L. (2017). Epistemologically privileging the sex worker. In M. Spanger & M. Skilbrei (Eds.), Prostitution research in context methodology, representation and power (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315692586

- Parker, R. G. (1996). Empowerment, community mobilization and social change in the face of HIV/AIDS. AIDS (London, England), 10(Suppl 3), S27–S31.

- Richter, M., Chersich, M. F., Vearey, J., Sartorius, B., Temmerman, M., & Luchters, S. (2014). Migration status, work conditions and health utilization of female sex workers in three South African cities. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 16(1), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-012-9758-4

- Rifkin, S. B. (1996). Paradigms lost: Toward a new understanding of community participation in health programmes. Acta Tropica, 61(2), 79–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-706X(95)00105-N

- Shaver, F. M. (2005). Sex work research. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(3), 296–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260504274340

- SWEAT. (2011). NPA guidelines encourage the abuse of sex workers: Media release.

- UCSF, Anova Health Institute, WRHI. (2015). South African health monitoring survey (SAHMS), final report: The integrated biological and behavioural survey among female Sex workers, South Africa 2013-2014. UCSF.

- Wojcicki, J. M. (2002). Commercial sex work or Ukuphanda? Sex-for-money exchange in Soweto and Hammanskraal area, South Africa. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 26(3), 339–370. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021291922026

- Wojcicki, J. M., & Malala, J. (2001). Condom use, power and HIV/AIDS risk: Sex workers bargain for survivial in Hillbrow/Joubert Park/Berea, Johannesburg. Social Science and Medicine, 53(1), 99–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00315-4

- World Health Organisation. (2002). WHO multicountry study on women's health and domestric violence: Core questionnaire and WHO instrument.

- Zulliger, R., Maulsby, C., Barrington, C., Holtgrave, D., Donastorg, Y., Perez, M., & Kerrigan, D. (2015). Retention in HIV care among female sex workers in the Dominican Republic: Implications for research, policy and programming. AIDS and Behavior, 19(4), 715–722. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0979-5