ABSTRACT

There is a dearth of evidence-based post-rape clinical care interventions tailored for refugee adolescents and youth in low-income humanitarian settings. Comics, a low-cost, low-literacy and youth-friendly method, integrate visual images with text to spark emotion and share health-promoting information. We evaluated a participatory comic intervention to increase post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) knowledge and acceptance, and prevent sexual and gender-based violence, in Bidi Bidi refugee settlement, Uganda. Following a formative qualitative phase, we conducted a pre-test post-test pilot study with refugee youth (aged 16–24 years) (n = 120). Surveys were conducted before (t0), after (t1), and two-months following (t2) workshops. Among participants (mean age: 19.7 years, standard deviation: 2.4; n = 60 men, n = 60 women), we found significant increases from t0 to t1, and from t0 to t2 in: (a) PEP knowledge and acceptance, (b) bystander efficacy, and (c) resilient coping. We also found significant decreases from t0 to t1, and from t0 to t2 in sexual violence stigma and depression. Qualitative feedback revealed knowledge and skills acquisition to engage with post-rape care and violence prevention, and increased empathy to support survivors. Survivor-informed participatory comic books are a promising approach to advance HIV prevention through increased PEP acceptance and reduced sexual violence stigma with refugee youth.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04656522.

Introduction

Sexual violence prevention and post-rape clinical care are key intervention areas for the more than 82.4 million forcibly displaced persons globally (Robbers & Morgan, Citation2017; UNHCR, Citation2020). An estimated one-fifth of refugee adolescent girls and women across diverse regional contexts report sexual violence experiences (Stark et al., Citation2017; Stark & Landis, Citation2016; Vu et al., Citation2014). While understudied among boys and men, evidence suggests that refugee boys and men experience sexual violence during conflict, border crossings and in host countries (Chynoweth et al., Citation2020). Sexual violence risks are elevated among conflicted-affected populations both in transit and in host countries due to a confluence of factors, including displacement, constrained access to social and economic resources, disrupted community networks, and gender inequity (Robbers & Morgan, Citation2017; Stark & Ager, Citation2011; Vu et al., Citation2014; Ward & Vann, Citation2002; Wirtz et al., Citation2014). Impacts of sexual violence are both immediate and long-lasting, including unplanned pregnancy, HIV and other sexually transmitted infection exposure, mental health challenges, and stigma (Logie et al., Citation2017, Citation2019; Murray et al., Citation2018; Robbers & Morgan, Citation2017). These effects may be exacerbated for refugee youth in East African contexts who may experience barriers to sexual and reproductive healthcare, including refugee and age-related stigma among other access-related barriers (e.g. language, transportation) (Logie, Okumu, Kibuuka Musoke, et al., Citation2021; O’Laughlin et al., Citation2021; Robbers & Morgan, Citation2017). Yet systematic reviews of sexual and reproductive health interventions in humanitarian contexts note critical gaps in evidence-based interventions for sexual violence prevention and post-rape clinical care with refugee adolescents and youth (Robbers & Morgan, Citation2017; Singh, Aryasinghe, et al., Citation2018; Singh, Smith, et al., Citation2018).

Post-rape clinical care involves post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and emergency contraception uptake and adherence – however, it is not known if refugee adolescents and youth have adequate knowledge and acceptability of PEP and post-rape clinical care at large (Barot, Citation2017; Murray et al., Citation2018; Robbers & Morgan, Citation2017). Researchers have called for further attention to strategies to enhance PEP completion following sexual assault among general, non-refugee populations in diverse global contexts, particularly among adolescents (Ford et al., Citation2014; Inciarte et al., Citation2020). There is also a dearth of studies focused on strategies to reduce sexual violence stigma – the devaluing, blame, shame, rejection, mistreatment and reduced access to social, health, economic and educational opportunities and resources experienced by conflict-affected sexual violence survivors that impacts both physical and mental health (Albutt et al., Citation2017; Kelly et al., Citation2017; Murray et al., Citation2018). Sexual violence stigma can create barriers to disclosure and accessing support (Schmitt et al., Citation2021), including engaging with post-rape sexual and reproductive health services (Muuo et al., Citation2020), and completing PEP (Abrahams & Jewkes, Citation2010). There is an urgent need to identify strategies to reduce sexual violence stigma and increase access to PEP among refugee adolescents and youth in order to improve physical and mental health post-rape (Singh, Aryasinghe, et al., Citation2018; Singh, Smith, et al., Citation2018).

Sexual violence prevention and care require multi-faceted approaches that engage all genders, transform community norms and practices that underpin violence perpetration – including inequitable gender norms, reduce sexual violence stigma, equip persons with skills to safely and appropriately interrupt violence as an active bystander, and provide physical and mental support to survivors (Abrahams et al., Citation2021; García-Moreno et al., Citation2015; Kyegombe et al., Citation2014; McMahon et al., Citation2011; McMahon & Banyard, Citation2012; Miller, Citation2018; Samarasekera & Horton, Citation2015). Participatory approaches span community, interpersonal and intrapersonal levels and engage community members as agents of change (Michau & Namy, Citation2021; What Works, Citation2016). Due to the need for contextual specificity in approaches (What Works, Citation2016), strategies should be adapted and tailored for local communities such as youth in refugee settlement contexts where there are knowledge gaps regarding efficacious approaches to increase engagement in post-rape clinical care (Singh, Aryasinghe, et al., Citation2018; Singh, Smith, et al., Citation2018) and reduce sexual violence stigma. The 2018 Interagency Field Manual Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) for humanitarian settings recommends youth participation in developing sexual violence prevention programs (Foster et al., Citation2017). While this guide addresses post-rape clinical care, it is focused on healthcare providers (Foster et al., Citation2017). To address this recommendation, we engaged refugee adolescents and youth in Bidi Bidi refugee settlement, Uganda, in creating a gender, age, and contextually tailored participatory comic post-rape care and sexual violence prevention intervention (Logie, Okumu, Lukone, et al., Citation2021).

Comics, a low-cost, low-literacy and youth-friendly method, are part of the graphic medicine field that integrates visual images with text to spark emotion and share information with both patients and health care providers (Green & Myers, Citation2010; Myers & Goldenberg, Citation2018). While not explicitly applied to PEP or other post-rape care issues, comics were applied in the Undetectables Intervention that was efficacious in increasing HIV adherence with adults living with HIV in the United States (US) (Ghose et al., Citation2019). Comics have also been used to explore PrEP motivations among Black men who have sex with men (MSM) in the US (Kuhn & Maatman, Citation2021), in safer sex prevention campaigns with MSM in the US and Belgium (Greenblatt, Citation2019), in a human papillomavirus vaccine intervention in the US (Chan et al., Citation2015), and in school-based HIV education in Kenya (Obare et al., Citation2013). Comics were employed to share lived experiences of HIV health care providers and people living with HIV to foster empathy and understanding (Czerwiec & Huang, Citation2017; Wessner, Citation2017). Among refugee youth, comics were used in qualitative studies of mental health programs in Greece (Moore, Citation2017) and Lebanon (Bosqui et al., Citation2020). We located no quantitative assessments of comic book efficacy in health interventions with refugee youth.

We aimed to contribute to the knowledge base of comic-based approaches for increasing PEP knowledge and acceptability, and sexual violence prevention, with refugee youth in a low-income humanitarian context. Pilot studies offer opportunities to test the feasibility of a method and examine preliminary evidence on the effectiveness of an intervention (Thabane et al., Citation2010). The study objective is to explore the feasibility and preliminary evidence of the effectiveness of a participatory comic book pilot study for post-rape care and sexual violence prevention with refugee youth aged 16–24 years living in Bidi Bidi refugee settlement, Uganda.

Methods

Study setting

Between December 2020 and February 2021, we conducted a pre-test post-test study of a post-rape care and sexual violence prevention workshop with refugee youth aged 16–24 years in Bidi Bidi refugee settlement, Uganda. Bidi Bidi has 239,000 residents – 23% aged 15–24 years – and is the second-largest refugee settlement globally (UNHCR, Citation2021). Multiple factors, including limited medical supplies and constrained access to mental health care, transportation barriers, and sexual violence and HIV-related stigma, reduce post-rape clinical care access in this settlement (ReliefWeb, Citation2017). This study was conducted in Zone 3 in Bidi Bidi where the community-based implementing partners Uganda Refugee and Disaster Management Council (URDMC) are located, and is the most populated settlement zone with 56,637 residents as of July 2021 (UNHCR, Citation2021).

Study procedures

Ngutulu Kagwero (roughly translated to ‘Agents of Change’ in Bari) was a one-day workshop using a participatory comic book with refugee youth aged 16–24 years focused on the impacts of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), PEP knowledge and awareness, and stigma towards SGBV survivors, which has been detailed elsewhere (Logie, Okumu, Lukone, et al., Citation2021). The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (#NCT04656522). The study began with a preliminary qualitative formative phase (data not presented) that generated data to inform the design of the one-day workshop and comic book. The results presented in this manuscript focus on the second phase of the study regarding the implementation of the Ngutulu Kagwero workshop intervention. Below we describe: (a) the intervention development phase; (b) the intervention; and (c) the study population.

Ngutulu Kagwero intervention development phase

A formative phase was first conducted to understand experiences of sexual violence, including post-rape clinical care awareness and engagement (e.g. PEP), sexual violence stigma, and contexts in which violence occurred, which was used to design the intervention. This formative phase involved conducting six focus groups with refugee youth (aged 16–24 years) sexual violence survivors and in-depth interviews with refugee youth sexual violence survivors (Logie, Okumu, Latif, et al., Citation2021), refugee elders (aged 55 and older and/or persons identified as an elder by their community), healthcare providers (n = 8) and police officers (n = 2) living in Bidi Bidi. Community collaborators at URDMC hired peer navigators, refugee youth living in Bidi Bidi aged 18–24 with lived experiences of sexual violence, to conduct purposive sampling to recruit participants for formative phases. There was an emphasis in formative phase recruitment to invite an equal proportion of participants aged 16–19 and aged 20-24, and an equal number of women identified and men identified participants.

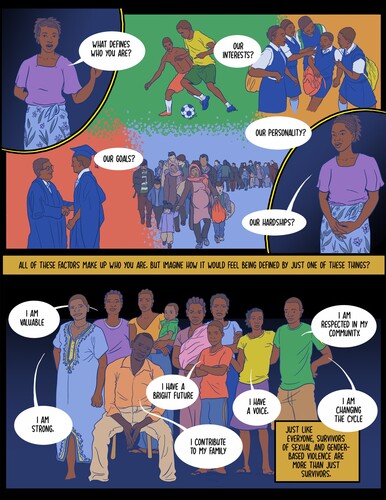

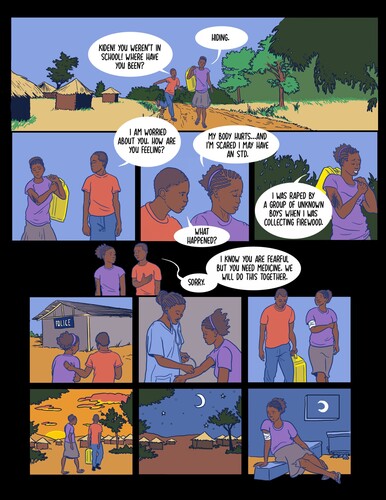

While the Ngutulu Kagwero development process is described in detail elsewhere (Logie, Okumu, Lukone, et al., Citation2021), in brief, we identified the following themes from the qualitative formative phase that were developed into scenarios for a comic book: (1) peer support for survivors to seek post-rape clinical care; (2) peer gossip as a conduit for sexual violence stigma; (3) confidentiality concerns in health care settings when accessing post-rape clinical care; (4) supportive post-rape care strategies by health providers, including PEP counselling; (5) supportive strategies for police officers to work with sexual violence survivors; (6) reducing stigmatising community beliefs toward sexual violence survivors; (7) reflecting positive masculinities to engage men in challenging violence; and (8) addressing forced, child, and early marriage consequences in families for adolescent girl and young women sexual violence survivors. An example of a comic scenario on peer support to access post-rape care is presented in . Further design of the workshop activities, detailed in the study protocol (Logie, Okumu, Lukone, et al., Citation2021), included a review of existing sexual violence programs and adapting these activities with a team of refugee youth peer navigators for enhancing local contextual relevance.

Figure 1. Example of comic book image from the Ngutulu Kawero post-rape care intervention with refugee youth in a humanitarian setting in Uganda focused on peer support to access post-rape care.

An example of a comic scenario focused on reducing stigma toward SGBV survivors is presented in .

Description of the Ngutulu Kagwero intervention

The one-day workshop included activities regarding: group norms (Welbourn et al., Citation2016), understanding SGBV and its impacts (Kyegombe et al., Citation2014; Namy et al., Citation2019), PEP knowledge and awareness (International Rescue Committee Inc., Citation2014; Kyegombe et al., Citation2014; Namy et al., Citation2019), sexual violence stigma (Kyegombe et al., Citation2014; Namy et al., Citation2019), and bystander practices (Hollaback!, Citation2021). Following these group-based activities, participants read and discussed the comic book scenarios together. They then were provided with a second comic book that was blank and were provided time and support to complete a blank version of the comic scenarios to share their own perspectives and solutions. Participants actively engaged with materials and shared their own experiences through stories and role play.

Study population for the Ngutulu Kagwero intervention

Refugee youth in Bidi Bidi were invited to participate in this one-day participatory comic book workshop. Inclusion criteria were: aged 16 and 24 years; identifying as a refugee or displaced person; residing in the Bidi Bidi refugee settlement in Zone 3; capable of providing informed consent; and speaking Juba Arabic, Bari or English. Purposive, non-random sampling methods were used for participant recruitment. Eight youth peer navigators, who identified as refugees and sexual violence survivors living in Bidi Bidi, shared information about the study with their social networks. Bidi Bidi research partners also shared information about the study with youth, elders, healthcare providers, and community leaders in Zone 3 of Bidi Bidi to recruit participants. A sample size of 109 was estimated to be sufficient to conduct paired sample t-tests to explore preliminary effectiveness as calculated with G*Power (two-tailed, effect size: 0.35, p = .05, power 0.95, critical t: 1.98) (Faul et al., Citation2007). Research ethics board approval for this study was provided by Mildmay Uganda Research Ethics Committee, Uganda National Council for Science and Technology, and the University of Toronto.

There was a total of six workshops, each with 20 participants. The workshops were gender segregated; three workshops were conducted exclusively with adolescent boys/young men (20 men per workshop; total 60 men) and three exclusively with adolescent girls/young women (20 women per workshop; total 60 women). Four young women peer navigators co-facilitated the young women’s workshops, and four young men peer navigators co-facilitated the young men’s workshops, along with two senior research coordinators who co-facilitated both workshops.

Data collection and measures

Data were collected from participants at three timepoints: directly before participating in the workshop (Time 0), later the same day immediately following the workshop (Time 1), and approximately eight weeks after the workshop (Time 2). Surveys were conducted in all study languages using a structured questionnaire administered by trained research assistants, and data were recorded on tablets using SurveyCTO (Dobility, Cambridge, U.S.A.). At Time 2, we included an open-ended question (‘What was your experience with the sexual and gender-based violence workshop that you participated in 2 months ago?’) to assess participants’ experiences of the workshop and what they had learned. Responses were audio-recorded on tablets using SurveyCTO (Citation2020) and transcribed verbatim. Scales were translated into Juba Arabic and Bari and pilot tested with bilingual translators and peer navigators to ensure cultural and linguistic appropriateness of measures.

To assess feasibility (Bell et al., Citation2018), we collected information on process (e.g. recruitment rates), resources (e.g. retention, survey completion length), management (e.g. time and capacity required to implement intervention), and scientific outcomes (e.g. survey challenges, estimated intervention effects on outcomes). Sociodemographic data including gender, age, education, and family structure were collected. Participant’s experience with sexual and physical violence in the past 12 months was also collected at Time 0. The following outcomes were measured at Time 0, and at Time 1 and Time 2 to assess preliminary evidence on the effectiveness of Ngutulu Kagwero: PEP knowledge and acceptability; bystander beliefs and behaviours; sexual violence stigma; and resilient coping. Depression was only assessed at Time 0 and Time 2 as the measure assessed depression symptoms over the past two weeks. To understand PEP knowledge and acceptability, we included questions on correct PEP use and accepting attitudes toward PEP use and adherence used in prior research (Logie et al., Citation2020). This was a categorical variable assessed at all three timepoints; response options (agree, disagree, don’t know) were dichotomised into knowledgeable/not knowledgeable and accepting/non-accepting.

Bystander behaviour refers to the processes and conditions through which persons who witness an emergency are likely to intervene to offer help, and has been applied to understanding the ways in which persons witnessing violence engage in prosocial behaviour to take action to help in the situation (Slaby & Wilson-Brewer R, Citation1994). To assess changes in bystander beliefs and behaviours we used two scales at Time 0, Time 1, and Time 2. These scales included the Slaby Bystander Efficacy Scale to assess beliefs on the potential to prevent violence (Slaby & Wilson-Brewer R, Citation1994) (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86 in present study), and the Banyard et al. Readiness to Change Scale (Banyard et al., Citation2007) to evaluate readiness to change one’s behaviour in order to prevent sexual assault with three items on contemplation (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.76 in present study) and one question on action. We assessed sexual violence stigma, referring to attitudes and beliefs toward sexual violence, including survivors, at the three timepoints using a scale that was based on Murray et al.’s scale developed in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Murray et al., Citation2018). The team added eight additional items to the sexual violence scale based on the formative qualitative phase findings to tailor the scale to our study population, increasing the number of scale items from 8 to 16 (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.81 in present study).

The Patient Health Questionnaire 2-item (PHQ-2) (Kroenke et al., Citation2003) was used to assess changes in depression symptoms at Time 0 and Time 2. Participants identified as having any suicidal ideation were referred to a local organisation that provides psychological support in Bidi Bidi and someone from this organisation was present during data collection to facilitate referrals. To assess adaptive coping, we used the Brief Resilient Coping Scale (BRCS) (Sinclair & Wallston, Citation2004) at Time 0 and Time 2, this assesses beliefs in being able to manage challenging circumstances, active problem solving, and positive growth from hardship (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.61 in present study).

Data analysis

The analytical cohort included all participants enrolled into the study who were available at all three timepoints. We investigated differences in demographic and baseline outcome variables between participants in the analytic cohort and those who were lost to follow-up using Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. Descriptive analyses were used to explore baseline sociodemographic factors, stratified by gender (women and men). Number and proportions were reported for each categorical factor and means and standard deviations (SD) or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) were reported for each continuous factor depending on the distribution. P-values from chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests for proportions and two-sample t-test for means are reported for differences by gender.

We assessed PEP knowledge and acceptance as answering at least three of four questions correctly (PEP knowledge) or in the affirmative (PEP acceptance). Following standard PHQ-2 procedures (Kroenke et al., Citation2003), depression was defined as a score of ≥1. The items included in the bystander and BRCS scales were summed to calculate scores for each outcome. The sexual violence stigma scale was calculated by taking the mean of the items for each participant and reporting the overall mean and standard deviation (Murray et al., Citation2018). The number and proportion of participants for each categorical outcome and the mean and SD or median and IQR for each continuous outcome were reported before (Time 0) and after the intervention (Time 1 and/or Time 2).

The McNemar’s test was used to assess the difference in proportions pre- and post-intervention for PEP knowledge and acceptance (McNemar, Citation1947). For each outcome, we estimated the change in outcome between Time 0–Time 1 and Time 0–Time 2, using time as the primary exposure. We conducted unadjusted and adjusted generalised estimating equation (GEE) regression models with robust standard errors to measure changes in sexual violence prevention and post-rape clinical care outcomes. The GEE models accounted for correlation among responses from multiple timepoints per participant with an exchangeable correlation matrix (Goldstein, Citation2006). Logistic GEE regression models were used for categorical outcomes (depression) and linear GEE regression models were used for continuous outcomes (bystander outcomes, resilient coping, sexual violence stigma). The GEE regression models were adjusted for covariates determined a priori as potentially associated with our main outcomes, including gender and age. All regression analyses were performed as a complete case analysis; odds ratios from logistic regression and beta coefficients from linear regression, along with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) and p-values are reported. We conducted a secondary analysis to examine outcome differences by gender at each timepoint and reported p-values comparing outcomes among men to women at each timepoint from chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact test for proportions, two-sample t-test for means, or Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test for medians. We then conducted the linear and logistic GEE regression models used above for the primary analysis and included an interaction term between time and gender to examine intervention effects by gender across each timepoint. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, U.S.A.). Open-ended responses were coded by three trained research assistants using Dedoose software (SocioCultural Research Consultants, LA, U.S.A.) (Dedoose, Citation2016) with thematic analysis approaches to identify preliminary codes that were collated into sub-themes and an overarching thematic map (Attride-Stirling, Citation2001; Braun & Clarke, Citation2006).

Results

Study population characteristics

There was an even split in gender among youth enrolled in the study (60 women, 60 men) (see ). Compared to young women participants, young men were on average older, more educated, and more likely to report earning any money in the past 12 months. Almost all participants were refugees from South Sudan (99.2%). Participants’ current relationship status significantly differed by gender: more men were married compared to women, whereas a higher proportion of women were separated compared to men. Experiences of physical violence were high among all participants (71.7%), as was sexual violence (53.3%); however, sexual violence was significantly higher among women than men.

Table 1. Baseline sociodemographic characteristics of refugee youth enrolled in Ngutulu Kagwero, Bidi Bidi, Uganda (n = 120).

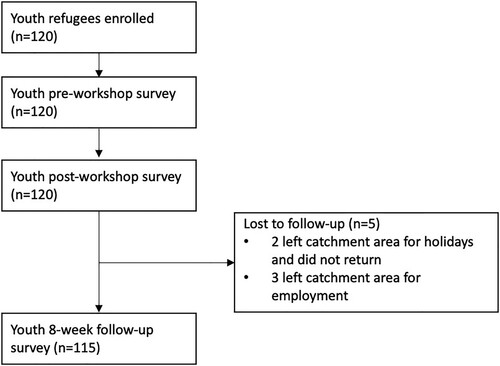

Five participants were lost to follow-up at Time 2 because they left the catchment area. There were no significant differences in key demographics nor sexual violence prevention and post-rape clinical care outcomes at baseline between those that were lost to follow-up and those that remained in the study to Time 2 (see Supplementary Table S1). There were also no differences by gender in study outcomes at baseline (see Supplementary Table S2).

Feasibility outcomes

There were 120 refugee adolescents and youth enrolled in the Ngutulu Kagwero workshops in December 2020. Study collaborators invited 120 persons to participate in the study, and 120 agreed to participate. All (100%) of the participants enrolled completed the surveys directly before and after the intervention (Time 0 and Time 1) and 95.8% completed the survey at the eight-week follow-up visit (Time 2) ().

Figure 3. Flow diagram of refugee youth through the Ngutulu Kawero study from enrolment to the eight-week follow-up visit in a humanitarian setting in Uganda.

In terms of the time and capacity required to implement the intervention, each workshop took on average 8 h to complete, including pre- and post-surveys, role plays, and comic books. The workshops took place in a classroom-style space, where tables and chairs were arranged in a circle to facilitate discussion. The workshops required very little equipment including print-outs of the comic books, pens and a chalkboard. COVID-19 protocols were followed including physical distancing, masking, and use of hand sanitiser following the Ugandan Ministry of Health protocols.

During baseline (t0), the survey took an average 23.2 min (SD: 8.48 min) to complete. The survey given after the workshop (t1) did not include demographic information collected in the baseline survey (t), hence was shorter in duration (t1 mean = 12.4 min (SD: 3.79 min). At Time 2, the survey took on average 36.9 min (SD: 13.83 min) to complete as it included more sociodemographic questions that were omitted from baseline in order to reduce the amount of time for the survey during the same day as the workshop. At Time 0 and 1, the number of interviews completed by a single research assistant ranged from 16 to 25, with a total of six research assistants collecting data. At Time 2, we increased the number of research assistants to seven due to the increased number of questions, and so the number of interviews completed by a single research assistant ranged from 12 to 23. Cronbach’s alphas were calculated and reported for each scale to assess the internal consistency of each scale in the study population. We utilised scales with an acceptable level of reliability, assessed by Cronbach’s alpha ≥0.60 (Hinton et al., Citation2014; Nunnally & Bernstein, Citation1994). All outcome measures used had adequate reliability; we excluded one outcome measure regarding equitable gender norms as the reliability for the Gender Equitable Men’s Scale (Pulerwitz & Barker, Citation2008) in this sample was Cronbach’s alpha = 0.54.

Comprehension of the survey was assessed through piloting and daily data quality checks. Academic researchers conducted training with research assistants based in or nearby Yumbe before surveys 1 and 2 in November and December 2020, and before survey 3 in February (trainings took place over 3 h for two days before Time 0, and for two days before Time 2). Trainings involved role play via web-based platform, as well as pilot testing the survey questionnaire and SurveyCTO platform with youth in Bidi Bidi to ensure that the topic of each question was understood by the study population. Overall, comprehension was good, but we faced a challenge when using the bystander efficacy scale where most of the questions were phrased in the affirmative and only a few phrased in the negative. This switching between affirmative and negative phrasing of the questions within the validated scale was not always understood by participants. Due to the short timeframe in which the survey took place, it was important to remind research assistants to not rush data collection and ensure participant comprehension of all questions. Through data quality checks we also identified questions that may have been subject to social desirability bias by participants, such as ‘Do you think PEP is important?’.

PEP knowledge and acceptance

presents changes in PEP outcomes over time. PEP knowledge increased significantly from Time 0 to Time 1 and remained high at the eight-week follow-up at Time 2. PEP acceptance also increased significantly from Time 0 to Time 1 and remained high at Time 2 (). There were no significant gender differences in PEP outcomes at baseline or across timepoints (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3).

Table 2. Distribution of sexual violence prevention and post-rape clinical care outcomes before, directly after and approximately eight weeks after the intervention, among Ngutulu Kagwero participants, Bidi Bidi, Uganda (n = 115).

Bystander efficacy and readiness to change

In adjusted analyses, bystander efficacy increased significantly from Time 0 to Time 1 and remained significantly higher at Time 2 than Time 0 (). There was a significant difference in bystander efficacy between men and women at Time 2 (Supplementary Table S2). However, there was no significant interaction between time and gender (Supplementary Table S3), suggesting no significant gender differences in intervention effects on bystander efficacy.

Table 3. Crude and adjusted models for post-rape clinical care and sexual violence prevention outcomes among Ngutulu Kagwero participants, Bidi Bidi, Uganda (n = 115).

In adjusted analyses, the precontemplation and contemplation stages of the readiness to change scale did not significantly change from T0 to T1 but were reduced significantly from T0 to Time 2 (). This reflects less people responding in ways that reflected precontemplation, a lack of awareness of sexual violence (e.g. not believing sexual violence is a big problem) or contemplation, planning but not yet acting on gaining new knowledge or actions to address sexual violence (Banyard et al., Citation2010). Scores on the action stage of the readiness to change scale, indicating engaging in learning and activities for being a proactive bystander and ending sexual violence, increased significantly at both Time 1 and Time 2 compared to Time 0 (). There were no significant gender differences in readiness to change outcomes at baseline or across timepoints (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3).

Sexual violence stigma

In adjusted analyses, sexual violence stigma reduced significantly at Time 1 compared to Time 0 and with a larger magnitude at Time 2 compared to Time 0 (). There were no significant gender differences in sexual violence stigma at baseline or across timepoints (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3).

Depression and resilience

Depressive symptoms were significantly reduced from 77.4% of participants reporting at least one of two symptoms at Time 0 to 33.0% at Time 2 ( and ). Resilient coping increased significantly at Time 2 compared to Time 0 (). There were no significant gender differences in depression or resilience outcomes at baseline or across timepoints (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3).

Open-ended feedback

Participants’ open-ended feedback at Time 2 on their workshop experiences highlighted the learning acquired on HIV prevention through PEP among 61/115 (53.0%) participants (26 women, 45 men). For instance, a young woman described learning new information on PEP: ‘Before I did not know what PEP was. And I didn’t know how or when to return back to the health centre after taking PEP’ (woman, A). PEP for post-rape care was new information for many participants, such as with this respondent: ‘I learnt about PEP. I did not know that it is given to a victim of rape’ (man, A). Many participants reported learning the steps for receiving PEP following sexual violence: ‘I also learned that a survivor of sexual and gender-based violence will be given PEP within 72 hours, and to be taken for 28 days’ (60,201 man, B). Others noted learning about HIV more generally, including HIV testing and HIV preventive measures. For instance: ‘It was a good experience on HIV and preventative measures, HIV testing, and advising us on [being a] bystander’ (man, C) and ‘Good experience. I learned about HIV. And also, PEP. PEP is a medicine to reduce the spread of the HIV virus’ (man, D). Participants additionally recalled learning about emergency contraception: ‘When a girl was raped, unwanted pregnancy can be prevented by giving a pill to prevent the pregnancy, they can be given tips that can prevent HIV’ (woman, B).

Learning about sexual violence prevention was reported by three-quarters of participants (86/115; 50 women, 36 men). This included identifying the difference forms of violence:

The experiences I got from the workshop, is what SGBV does. Sexual assault and gender-based violence is a violation of human rights. And different forms of violence: physical violence, emotional violence, sexual violence, and economical violence. (man, E)

Young women noted learning about what child, early and forced marriage (CEFM) is: ‘I learned about sexual and gender-based violence. Forced marriage without your will, how to support your friends who were forced to get married’ (30,503 woman) as well as the importance of CEFM prevention: ‘I also learned about sexual and gender-based violence, that people should not force marriage’ (woman, C), and ‘We learned about early marriage, how to reduce or stop early marriage’ (woman, D).

Others specifically reported learning about being a bystander and supporting survivors, and the role of the bystander:

It helped me also to know how to respond to violence as a bystander, how to handle victims of SGBV, how to use PEP, also how to offer psychosocial support to those that are stigmatised as a result of being exposed to SGBV. (man, F)

Participants reported understanding how to provide support and care to sexual violence survivors:

In the comic books, I've learned more about, in case a person, a friend is just raped. We can sit her down, we can try to ask what is going on, try to help her explain it to you and then find good ways on how her case can be supported. (man, G)

This involved specifically noting the importance of linking survivors to health and police services alongside awareness of stigma: ‘I got to know about a bystander, a person who is a witness. Learnt also about stigma. How to help the person who has been raped, reporting to the police after taking her to the hospital’ (woman, E). This workshop information was described as helpful for sharing with others: ‘I am now able to pass information on SGBV to others. The benefit I got, I learned how to act as a bystander or eyewitness’ (woman, F).

Finally, nearly half of participants (54/115, 27 women, 27 men) discussed learning about stigma. This included describing what stigma was and its impacts: ‘What I learned is stigma is negative beliefs or attitudes about a person experiencing sexual and gender-based violence in the community’ (man, D) and ‘Stigma is like when you are raped, you are now scared to share it and stay with your group’ (woman, G). Others described learning to cope with experiences of stigma (‘in the workshop, I learned how to manage stigma, like being social with friends’ [woman, H]) and feeling more equipped to support survivors (‘I learned not to abandon my friends who experience sexual violence’ [woman, I]). Wanting to support survivors was linked to a better understanding of stigma’s effects: ‘they feel neglected, they feel isolated, which is not good, but when I learnt all this, I am even able to help someone who has already been raped.’ (man, H)

Discussion

Our study demonstrates the feasibility and potential of a participatory comic book intervention for improving knowledge and acceptability of PEP, reducing sexual violence stigma, and increasing bystander efficacy among refugee youth in Uganda. Participants’ qualitative feedback on workshop experiences reinforced the quantitative data that signalled improved PEP knowledge and acceptance nearly two-months following the intervention, alongside sexual violence stigma reduction and increased bystander efficacy. This study is unique in its approach to developing and integrating comic book scenarios based on lived experiences of refugee youth sexual violence survivors into a participatory intervention whereby youth could fill in their own comic book responses, thoughts and feelings on a range of sexual health issues (Logie, Okumu, Lukone, et al., Citation2021). It is also novel in its focus on PEP, bystander practices, and sexual violence stigma with refugee youth in a low-income humanitarian context who are understudied in sexual and reproductive health interventions (Singh, Aryasinghe, et al., Citation2018; Singh, Smith, et al., Citation2018). This pilot study was shown to be feasible and acceptable, with high follow-up at two months (96%), and implementation by local study collaborators, including refugee youth.

Findings build on literature that point to the benefits of participatory sexual violence prevention strategies that engage all genders, address stigma and gender inequity, and provide tangible skills for responding to the continuum of violence inclusive of prevention and post-rape care (García-Moreno et al., Citation2015; Kyegombe et al., Citation2014; McMahon et al., Citation2011; McMahon & Banyard, Citation2012; Miller, Citation2018; Samarasekera & Horton, Citation2015). We found no significant differences in the intervention effect between young women and men, suggesting the promise of this approach across genders. We applied prior research recommendations to engage persons as agents of change (Michau & Namy, Citation2021; What Works, Citation2016) through a comic-based approach, which we found increased refugee youth’s beliefs regarding the potential to prevent violence (Slaby & Wilson-Brewer R, Citation1994) but readiness to change one’s behaviour was not significantly impacted (Banyard et al., Citation2007). Our findings contribute to the nascent knowledge base of comic-based interventions for the HIV prevention and care cascade among non-refugee populations. For instance, the Undetectables Intervention included a toolkit with graphic novels with adults living with HIV in the US, and was associated with increased viral suppression (Ghose et al., Citation2019). Qualitative feedback from the Undetectables Intervention revealed that participants felt motivated through the comics and connected with who they aspired to be (Ghose et al., Citation2019). The qualitative feedback in the present study similarly revealed acquisition of knowledge and skills, and increased empathy, to engage with PEP and other post-rape care, violence prevention, and support survivors.

Our findings of reduced depression and increased resilient coping corroborate prior research with refugee youth in diverse global contexts on comic-book approaches to improving mental health, where studies found this method facilitated goal setting (Moore, Citation2017) and provided psychoeducation, including communication skills (Bosqui et al., Citation2020). Prior psychoeducational group-based workshops with displaced women in Haiti also noted decreased depression following intervention implementation (Logie et al., Citation2014); it is plausible that the workshop provided an opportunity to connect with others and increase social support (Logie & Daniel, Citation2016). Our finding of reduced sexual violence stigma aligns with the literature on graphic medicine’s ability to evoke emotion, empathy and understanding regarding stigmatising topics, including HIV (Czerwiec & Huang, Citation2017; Green & Myers, Citation2010; Myers & Goldenberg, Citation2018; Wessner, Citation2017).

There are several study limitations. As this was a pilot study with a non-random sample, generalisability of findings is limited. Youth with greater social networks, and less sexual violence stigma, may have been more likely to participate and thus we may overestimate the intervention appropriateness for youth with smaller networks or greater stigma. There was no control group, precluding verifying that changes in outcomes are attributable to workshop participation rather than other influences. Participants were not blinded to treatment allocation due to the single-group design. There were insufficient health and financial resources to offer HIV testing as part of this study, hence we did not collect HIV serostatus information that could directly relate to knowledge/acceptability of PEP. The single open-ended question on intervention experiences did not allow for in-depth probing. Also, the two-month follow-up did not permit us to explore long-lasting intervention effects. Despite these limitations, pilot studies ‘are an almost essential pre-requisite’ (p. 1) (Thabane et al., Citation2010) to larger randomised controlled trials, and our findings on feasibility and preliminary evidence of effectiveness suggest the need for a larger study of Ngutulu Kawero with a rigorous study design.

Conclusions

Taken together, findings signal the utility of participatory comic book approaches such as Ngutulu Kawero with refugee youth focused on clinical and mental health dimensions of post-rape care, sexual violence prevention, and survivor support. PEP is a feasible and acceptable HIV prevention tool in rural Uganda with non-refugee adults (Ayieko et al., Citation2021); however, PEP adherence is low across diverse global settings and populations, particularly for sexual assault (estimated at 40.2%). Our findings address calls for sexual health interventions focused on refugee adolescents and sexual assault survivors that are multi-faceted, including both clinical care (i.e. PEP) and mental health support and empowerment (Ford et al., Citation2014; Singh, Aryasinghe, et al., Citation2018; Singh, Smith, et al., Citation2018). Methods could be integrated as a tool in humanitarian health settings to complement the Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) implementation with health providers (Foster et al., Citation2017). Comic book approaches offer an innovative approach to address gaps in motivation, access, and use of HIV prevention tools such as PEP to advance the HIV prevention cascade (Moorhouse et al., Citation2019) with refugee youth in humanitarian contexts and empower refugee youth to reduce stigma and intervene when witnessing violence in their communities.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (28.3 KB)Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the participants, peer researchers, research assistants, and collaborations with the International Research Consortium, Uganda Refugee and Disaster Management Council, and the Ugandan Ministry of Health. We also acknowledge Hugh Goldring and Nicole Marie Burton at Petroglyph Comics for the comic art and design.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abrahams, N., & Jewkes, R. (2010). Barriers to post exposure prophylaxis (PEP) completion after rape: A South African qualitative study. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 12(5), 471–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050903556316

- Abrahams, N., Mhlongo, S., Dunkle, K., Chirwa, E., Lombard, C., Seedat, S., Kengne, A. P., Myers, B., Peer, N., Garcia-Moreno, C., & Jewkes, R. (2021). Increase in HIV incidence in women exposed to rape. AIDS (London, England), 35(4), 633–642. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000002779

- Albutt, K., Kelly, J., Kabanga, J., & VanRooyen, M. (2017). Stigmatisation and rejection of survivors of sexual violence in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Disasters, 41(2), 211–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12202

- Attride-Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 385–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/146879410100100307

- Ayieko, J., Petersen, M. L., Kabami, J., Mwangwa, F., Opel, F., Nyabuti, M., Charlebois, E. D., Peng, J., Koss, C. A., Balzer, L. B., Chamie, G., Bukusi, E. A., Kamya, M. R., & Havlir, D. V. (2021). Uptake and outcomes of a novel community-based HIV post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) programme in rural Kenya and Uganda. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 24(6), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25670

- Banyard, V. L., Eckstein, R. P., & Moynihan, M. M. (2010). Sexual violence prevention: The role of stages of change. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(1), 111–135. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260508329123

- Banyard, V. L., Moynihan, M. M., & Plante, E. G. (2007). Sexual violence prevention through bystander education: An experimental evaluation. Journal of Community Psychology, 35(4), 463–481. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20159

- Barot. (2017). The growing challenge of meeting the reproductive health needs of women in humanitarian situations. Guttmacher Policy Review, 20, 24–30. https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/article_files/gpr2002417_1.pdf

- Bell, M. L., Whitehead, A. L., & Julious, S. A. (2018). Guidance for using pilot studies to inform the design of intervention trials with continuous outcomes. Clinical Epidemiology, 10, 153–157, https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S146397

- Bosqui, T., Mayya, A., Younes, L., Baker, M. C., & Annan, I. M. (2020). Disseminating evidence-based research on mental health and coping to adolescents facing adversity in Lebanon: A pilot of a psychoeducational comic book ‘Somoud’. Conflict and Health, 14(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-020-00324-7

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Chan, A., Brown, B., Sepulveda, E., & Teran-Clayton, L. (2015). Evaluation of fotonovela to increase human papillomavirus vaccine knowledge, attitudes, and intentions in a low-income hispanic community. BMC Research Notes, 8(1), 615. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1609-7

- Chynoweth, S. K., Buscher, D., Martin, S., & Zwi, A. B. (2020). Characteristics and impacts of sexual violence against Men and boys in conflict and displacement: A multicountry exploratory study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(9-10), NP7470–NP7501, https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520967132

- Czerwiec, M., & Huang, M. N. (2017). Hospice comics: Representations of patient and family experience of illness and death in graphic novels. Journal of Medical Humanities, 38(2), 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-014-9303-7

- Dedoose. (2016). Web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data (7.0.23). SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC.

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

- Ford, N., Irvine, C., Shubber, Z., Baggaley, R., Beanland, R., Vitoria, M., Doherty, M., Mills, E. J., & Calmy, A. (2014). Adherence to HIV postexposure prophylaxis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS (London, England), 28(18), 2721–2727. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000000505

- Foster, A. M., Evans, D. P., Garcia, M., Knaster, S., Krause, S., McGinn, T., Rich, S., Shah, M., Tappis, H., & Wheeler, E. (2017). The 2018 inter-agency field manual on reproductive health in humanitarian settings: Revising the global standards. Reproductive Health Matters, 25(51), 18–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2017.1403277

- García-Moreno, C., Zimmerman, C., Morris-Gehring, A., Heise, L., Amin, A., Abrahams, N., Montoya, O., Bhate-Deosthali, P., Kilonzo, N., & Watts, C. (2015). Addressing violence against women: A call to action. The Lancet, 385(9978), 1685–1695. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61830-4

- Ghose, T., Shubert, V., Poitevien, V., Choudhuri, S., & Gross, R. (2019). Effectiveness of a viral load suppression intervention for highly vulnerable people living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior, 23(9), 2443–2452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02509-5

- Goldstein, R. (2006). Regression Methods in biostatistics: Linear, logistic, survival and repeated measures models. Technometrics, 48(1), 149–150. https://doi.org/10.1198/tech.2006.s357

- Green, M. J., & Myers, K. R. (2010). Graphic medicine: Use of comics in medical education and patient care. BMJ, 340(2), c863–c863, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c863

- Greenblatt, J. (2019). The banality of anal: Safer sexual erotics in the gay men’s health crisis’ safer sex Comix and Ex Aequo’s Alex et la vie d’après. Journal of Medical Humanities, 40(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-018-9535-z

- Hinton, P., McMurray, I., & Brownlow, C. (2014). SPSS explained. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315797298

- Hollaback!. (2021). Bystander intervention training. https://www.ihollaback.org/bystander-resources/

- Inciarte, A., Leal, L., Masfarre, L., Gonzalez, E., Diaz-Brito, V., Lucero, C., Garcia-Pindado, J., León, A., García, F., Manzardo, C., Nicolás, D., Bodro, M., del Río, A., Cardozo, C., Cervera, C., Pericás, J. M., Sanclemente, G., García-Pindado, J., Cobos, N., … García, L. L. (2020). Post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV infection in sexual assault victims. HIV Medicine, 21(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/hiv.12797

- International Rescue Committee Inc. (2014). Clinical care for sexual assault survivors: A multimedia training tool facilitator’s guide.

- Kelly, J., Albutt, K., Kabanga, J., Anderson, K., & VanRooyen, M. (2017). Rejection, acceptance and the spectrum between: Understanding male attitudes and experiences towards conflict-related sexual violence in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. BMC Women’s Health, 17, 127. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-017-0479-7

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2003). The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care, 41(11), 1284–1292. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C

- Kuhn, A., & Maatman, T. (2021). Annals graphic medicine – Should I PrEP? Barriers to HIV-related preventive care faced by black MSM. Annals of Internal Medicine, 174(4), W37–W44. https://doi.org/10.7326/G20-0086

- Kyegombe, N., Abramsky, T., Devries, K. M., Starmann, E., Michau, L., Nakuti, J., Musuya, T., Heise, L., & Watts, C. (2014). The impact of SASA! a community mobilization intervention, on reported HIV-related risk behaviours and relationship dynamics in Kampala, Uganda. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 17(1), 19232, https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.17.1.19232

- Logie, C. H., & Daniel, C. (2016). My body is mine’: Qualitatively exploring agency among internally displaced women participants in a small-group intervention in Leogane, Haiti. Global Public Health, 11(1–2), 122–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2015.1027249

- Logie, C. H., Daniel, C., Newman, P. A., Weaver, J., & Loutfy, M. R. (2014). A psycho-educational HIV/STI prevention intervention for internally displaced women in leogane, Haiti: Results from a non-randomized cohort pilot study. PLoS One, 9(2), e89836–e89836. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089836

- Logie, C. H., Kaida, A., de Pokomandy, A., O’Brien, N., O’Campo, P., MacGillivray, J., Ahmed, U., Arora, N., Wang, L., Jabbari, S., Kennedy, L., Carter, A., Proulx-Boucher, K., Conway, T., Sereda, P., & Loutfy, M. (2017). Prevalence and correlates of forced sex as a self-reported mode of HIV acquisition among a cohort of women living with HIV in Canada. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(21-22), 5028–5063, https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517718832

- Logie, C. H., Okumu, M., Kibuuka Musoke, D., Hakiza, R., Mwima, S., Kacholia, V., Kyambadde, P., Mimy Kiera, U., Mbuagbaw, L., Bandow, G., Chang, A., Chua, S., Dlova, N., Enbiale, W., Forrestel, A., Fuller, C., Griffiths, C., Hay, R., Hughes, J., … Williams, T. (2021). The role of context in shaping HIV testing and prevention engagement among urban refugee and displaced adolescents and youth in Kampala, Uganda: Findings from a qualitative study. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 26(00), 572–581. https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.13560

- Logie, C. H., Okumu, M., Latif, M., Musoke, D. K., Odong Lukone, S., Mwima, S., & Kyambadde, P. (2021). Exploring resource scarcity and contextual influences on wellbeing among young refugees in Bidi Bidi refugee settlement, Uganda: Findings from a qualitative study. Conflict and Health, 15(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-020-00336-3

- Logie, C. H., Okumu, M., Lukone, S. O., Loutet, M., Mcalpine, A., Latif, M., Berry, I., Kisubi, N., Mwima, S., Neema, S., Small, E., Balyejjusa, S. M., Logie, C. H., Okumu, M., Lukone, S. O., Loutet, M., Mcalpine, A., Latif, M., Berry, I., … Kagwero, N. (2021). Ngutulu Kagwero (agents of change): study design of a participatory comic pilot study on sexual violence prevention and post-rape clinical care with refugee youth in a humanitarian setting in Uganda. Global Health Action, 14(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2021.1940763

- Logie, C. H., Wang, Y., Lalor, P., Williams, D., & Levermore, K. (2020). Pre and post-exposure prophylaxis awareness and acceptability among sex workers in Jamaica: A cross-sectional study. AIDS and Behavior, 25(2), 330–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02972-5

- Logie, C., Okumu, M., Mwima, S., Hakiza, R., Irungi, K. P., Kyambadde, P., Kironde, E., & Narasimhan, M. (2019). Social ecological factors associated with experiencing violence among urban refugee and displaced adolescent girls and young women in informal settlements in Kampala, Uganda: A cross-sectional study. Conflict & Health, 13(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-019-0242-9

- McMahon, S., & Banyard, V. L. (2012). When can I help? A conceptual framework for the prevention of sexual violence through bystander intervention. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 13(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838011426015

- McMahon, S., Postmus, J. L., & Koenick, R. A. (2011). Conceptualizing the engaging bystander approach to sexual violence prevention on college campuses. Journal of College Student Development, 52(1), 115–130. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2011.0002

- McNemar, Q. (1947). Note on the sampling error of the difference between correlated proportions or percentages. Psychometrika, 12(2), 153–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02295996

- Michau, L., & Namy, S. (2021). SASA! together: An evolution of the SASA! approach to prevent violence against women. Evaluation and Program Planning, 86, 101918, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2021.101918

- Miller, E. (2018). Reclaiming gender and power in sexual violence prevention in adolescence. Violence Against Women, 24(15), 1785–1793. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801217753323

- Moore, T. (2017). Strengths-based narrative storytelling as therapeutic intervention for refugees in Greece. World Federation of Occupational Therapists Bulletin, 73(1), 45–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/14473828.2017.1298557

- Moorhouse, L., Schaefer, R., Thomas, R., Nyamukapa, C., Skovdal, M., Hallett, T. B., & Gregson, S. (2019). Application of the HIV prevention cascade to identify, develop and evaluate interventions to improve use of prevention methods: Examples from a study in east Zimbabwe. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 22(S4), 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25309

- Murray, S. M. I., Robinette, K. L., Bolton, P., Cetinoglu, T., Murray, L. K., Annan, J., & Bass, J. K. (2018). Stigma Among survivors of sexual violence in Congo: Scale development and psychometrics. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(1), 491–514. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515608805

- Muuo, S., Muthuri, S. K., Mutua, M. K., McAlpine, A., Bacchus, L. J., Ogego, H., Bangha, M., Hossain, M., & Izugbara, C. (2020). Barriers and facilitators to care-seeking among survivors of gender-based violence in the Dadaab refugee complex. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 28(1), 1722404. https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2020.1722404

- Myers, K. R., & Goldenberg, M. D. F. (2018). Graphic pathographies and the ethical practice of person-centered medicine. AMA Journal of Ethics, 20(2), 158–166. https://doi.org/10.1001/journalofethics.2018.20.2.medu2-1802

- Namy, S., Ghebrebrhan, N., Lwambi, M., Hassan, R., Wanjiku, S., Wagman, J., & Michau, L. (2019). Balancing fidelity, contextualisation, and innovation: Learning from an adaption of SASA! to prevent violence against women in the Dadaab refugee camp. Gender & Development, 27(2), 203–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2019.1615290

- Nunnally, J., & Bernstein, I. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Obare, F., Birungi, H., Deacon, B., & Burnet, R. (2013). Effectiveness of using comic books to communicate HIV and AIDS messages to in-school youth: Insights from a pilot intervention study in Nairobi, Kenya. Etude de La Population Africaine, 27(2), 203. https://doi.org/10.11564/27-2-441

- O’Laughlin, K. N., Greenwald, K., Rahman, S. K., Faustin, Z. M., Ashaba, S., Tsai, A. C., Ware, N. C., Kambugu, A., & Bassett, I. V. (2021). A social-ecological framework to understand barriers to HIV clinic attendance in nakivale refugee settlement in Uganda: A qualitative study. AIDS and Behavior, 25(6), 1729–1736. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03102-x

- Pulerwitz, J., & Barker, G. (2008). Measuring attitudes toward gender norms among young men in Brazil: development and psychometric evaluation of the GEM scale. Men and Masculinities, 10(3), 322–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X06298778

- ReliefWeb. (2017). Uganda refugee response monitoring settlement fact sheet: Bidi Bidi (December 2017) – Uganda | ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/uganda/uganda-refugee-response-monitoring-settlement-fact-sheet-bidi-bidi-december-2017

- Robbers, G. M. L., & Morgan, A. (2017). Programme potential for the prevention of and response to sexual violence among female refugees: A literature review. Reproductive Health Matters, 25(51), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2017.1401893

- Samarasekera, U., & Horton, R. (2015). Prevention of violence against women and girls: A new chapter. The Lancet, 385(9977), 1480–1482. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61775-X

- Schmitt, S., Robjant, K., Elbert, T., & Koebach, A. (2021). To add insult to injury: Stigmatization reinforces the trauma of rape survivors – Findings from the DR Congo. SSM – Population Health, 13, 100719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100719

- Sinclair, V. G., & Wallston, K. A. (2004). The development and psychometric evaluation of the brief resilient coping scale. Assessment, 11(1), 94–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191103258144

- Singh, N. S., Aryasinghe, S., Smith, J., Khosla, R., Say, L., & Blanchet, K. (2018). A long way to go: A systematic review to assess the utilisation of sexual and reproductive health services during humanitarian crises. BMJ Global Health, 3(2), e000682. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000682

- Singh, N. S., Smith, J., Aryasinghe, S., Khosla, R., Say, L., & Blanchet, K. (2018). Evaluating the effectiveness of sexual and reproductive health services during humanitarian crises: A systematic review. PLoS One, 13(7), e0199300. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0199300

- Slaby, R., & Wilson-Brewer R, D. H. (1994). Final report for aggressors, victims, and bystanders project.

- Stark, L., & Ager, A. (2011). A systematic review of prevalence studies of gender-based violence in complex emergencies. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 12(3), 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838011404252

- Stark, L., Asghar, K., Yu, G., Bora, C., Baysa, A. A., & Falb, K. L. (2017). Prevalence and associated risk factors of violence against conflict-affected female adolescents: A multi-country, cross-sectional study. Journal of Global Health, 7(1), 10416. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.07.010416

- Stark, L., & Landis, D. (2016). Violence against children in humanitarian settings: A literature review of population-based approaches. Social Science & Medicine, 152(1982), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.01.052

- SurveyCTO. (2020). In SurveyCTO. https://www.surveycto.com/

- Thabane, L., Ma, J., Chu, R., Cheng, J., Ismaila, A., Rios, L. P., Robson, R., Thabane, M., Giangregorio, L., & Goldsmith, C. (2010). A tutorial on pilot studies: The what, why and how. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 10(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-10-1

- UNHCR. (2020). Global trends: forced displacement in 2020. In UNHCR (Issue 265). https://www.unhcr.org/60b638e37/unhcr-global-trends-2020

- UNHCR. (2021). Refugees and aslyum seekers in Uganda (Issue July).

- Vu, A., Adam, A., Wirtz, A., Pham, K., Rubenstein, L., Glass, N., Beyrer, C., & Singh, S. (2014). The prevalence of sexual violence among female refugees in complex humanitarian emergencies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Currents, 6. https://doi.org/10.1371/currents.dis.835f10778fd80ae031aac12d3b533ca7

- Ward, J., & Vann, B. (2002). Gender-based violence in refugee settings. The Lancet, 360, s13–s14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11802-2

- Welbourn, A., Kilonzo, F., Mboya, T. J., & Mohamed Liban, S. (2016). Stepping stones and stepping stones plus. https://doi.org/10.3362/9781780448916

- Wessner, D. (2017). Using a nurse’s graphic medicine memoir to help students learn about HIV/AIDS. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education, 18(3), 3. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v18i3.1410

- What works to prevent violence against women and girls in conflict and humanitarian crisis: Synthesis Brief. (2016). What Works to Prevent VAWG. https://www.whatworks.co.za/resources/policy-briefs/item/662-what-works-to-prevent-violence-against-women-and-girls-in-conflict-and-humanitarian-crisis-synthesis-brief.

- Wirtz, A. L., Pham, K., Glass, N., Loochkartt, S., Kidane, T., Cuspoca, D., Rubenstein, L. S., Singh, S., & Vu, A. (2014). Gender-based violence in conflict and displacement: Qualitative findings from displaced women in Colombia. Conflict and Health, 8(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1505-8-10