ABSTRACT

Violence in the community can impact access to health care. This scoping review examines the impact of urban violence upon youth (aged 15–24) access to sexual and reproductive health and trauma care in Low and Middle Income Countries (LMICs). We searched key electronic health and other databases for primary peer-reviewed studies from 2010 through June 2020. Thirty five of 6712 studies extracted met criteria for inclusion. They were diverse in terms of study objective and design but clear themes emerged. First, youth experience the environment and interpersonal relationships to be violent which impacts their access to health care. Second, sexual assault care is often inadequate, and stigma and abuse are sometimes reported in treatment settings. Third is the low rate of health seeking among youth living in a violent environment. Fourth is the paucity of literature focusing on interventions to address these issues. The scoping review suggests urban violence is a structural and systemic issue that, particularly in low-income areas in LMICs, contributes to framing the conditions for accessing health care. There is a gap in evidence about interventions that will support youth to access good quality health care in complex scenarios where violence is endemic.

Introduction

Access to quality health services is a human right that is limited for many young people living in urban, low-income and violence-endemic neighbourhoods in Low and Middle Income Countries (LMICs). Our definition of urban violence is based upon a modified World Health Organisation (WHO) definition of violence which refers to ‘the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual … that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation’ (WHO, Citation2002, p. 4). We also draw upon representations of urban environments which highlight discourses of the city as a dangerous place because dangerous people live there (Body-Gendrot, Citation1995). Urban violence defined in this way affects many countries globally, particularly in low-income settings, with LMICs most severely affected (Matzopoulos et al., Citation2008).

Youth violence as defined by the WHO is a global public health problem (WHO, Citation2015) and in many low-income neighbourhoods violence is a structural part of everyday life, and young people, are disproportionally affected (de Ribera et al., Citation2019). Worldwide, homicides are the fourth leading cause of death for youth aged 10–29 (84% of whom are males) and one in eight young people (mainly girls) report sexual abuse (WHO, Citation2020).

The adverse impacts of violence not only include mortality, direct injury/physical trauma but also a deterioration of mental health and well-being that may in turn impose a direct (and measurable) burden on the health system, while at the same time driving rates of violence even higher within afflicted communities (Matzopoulos et al., Citation2008). Moreover, perceived fear and exposure to community violence is associated with a decreased likelihood of seeking care (Mmari et al., Citation2016). Urban violence can impede access to care and also negatively impact the operation of an effective health system (Bowers, Citation2008; Cooper et al., Citation2019; Michelman & Patak, Citation2008). Violence is thus a barrier to universal health coverage by inhibiting youth utilisation and access to acceptable health care.

This scoping review aimed to improve understanding of the barriers (and ways to overcome such barriers) created by urban violence on youth health care access. There is no available review of youth access to care in the context of violence in LMICs. This review thus complements the existing literature about the association between violence and health, the great majority of which is based on studies conducted in high-income countries rather than in LMICs. This includes: health systems response to violence against women, particularly to support women subjected to intimate and sexual violence (García-Moreno et al., Citation2015); the impact of stigma on care-seeking (Kinsler et al., Citation2007); literature on aspects of youth violence (e.g. Involvement in gangs, violence and place, negative health consequences of violence), much of which focuses on violence prevention (Nation et al., Citation2021).

We sought to review the available evidence in order to identify key characteristics or factors related to urban violence and youth access to sexual, reproductive and trauma care. We sought to answer the question: What is known about how urban violence impacts access to and delivery of health care for sexual and reproductive health and trauma services for youth in LMICs?

Our focus is on violence in public spaces rather than in domestic settings, which we categorise into three broad and intersecting forms. Our first category is interpersonal violence in both physical and psychological domains – either directly as victims or perpetrators themselves or as members of communities where such violence is highly prevalent. Gender-based violence including sexual assault and rape are implicitly included as their effects span both the physical and psychological domains. Our second category is community violence as defined by Wright and colleagues (Citation2016). This refers to violence occurring outside the home but does not include acts of war and terrorism. Both victimisation by community violence (i.e. being the recipient of an intentional act intended to cause harm) and witnessing community violence (i.e. seeing an event that involves loss or injury of some kind, including death) are included. Our final category is institutional/systemic violence within the health system. Institutional violence includes expressions of racism and disrespect to cultures and ethnicities (Fernandes et al., Citation2018) as well as stigma and discrimination (see Parker, Citation2012), which can be experienced and perpetuated at individual and community levels.

This review synthesises the evidence base we identified and provides valuable insights for the design of future interventions to limit the impact of urban violence on access and delivery of health care for young people.

Method

A scoping review was selected rather than a systematic review as the purpose was to review a broad body of literature to identify knowledge gaps and identify key characteristics related to the concept (Munn et al., Citation2018). Scoping reviews are well suited to address explanatory research questions, identify key concepts and enable the use of broad inclusion criteria to identify a range of available evidence (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005).

We focused on sexual and reproductive health (SRH) and trauma services as these are most frequently sought by young people. In addition, sexual assault (primarily affecting females) and trauma (primarily affecting males) are risks for youth exposed to violence. SRH includes a range of treatment and care services (contraception, abortion, maternal health, sexually transmitted infections, HIV testing and treatment, reproductive tract infections, sexual violence, menstrual problems). Trauma includes services dealing with wounds and other physical injuries as well as psychological trauma.

Search strategy

A combination of keywords to identify articles including youth, violence and health care were developed by the authors (see Supplementary Material: Appendix 1). The following electronic databases were searched: PUBMED; SCI Web of Science; SCOPUS; the Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE); PsycINFO; Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE) NLM Gateway;, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL); LILACS; the Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC). The search was performed in early July 2020.

Eligibility criteria

This review was conducted as part of a grant for research about health care systems in LMICs as defined by the World Bank classification. Our decision to limit the review to LMICS was not only made in relation to the funding body but also because LMICS face different challenges to high-income countries in relation to health systems, services and general social context. The focus on LMICS would thus allow for more meaningful analysis of challenges and responses. The impact of urban violence is likely to vary according to resources available to health care systems and there is a relative dearth of LMIC literature despite the disproportionate burden of interpersonal violence on health and development in LMICs. We were also keen to explore contemporary experiences and were mindful that urban violence contexts change over time as the country contexts (health system, characterisation of violence, programmes and interventions) around which issues of violence operate are likely to change significantly over a period of ten years, We, therefore, restricted our review to papers published between January 2010 and June 2020 and included those that met the following criteria: based on primary research; focused on LMICs; focused on youth aged 15–24 (at least two-thirds of the sample or the article presented age-specific results); were conducted in an urban setting or had a predominantly urban-dwelling sample (at least two-thirds of the sample); focused on SRH treatment, prevention (but not health promotion) or care and trauma services; included violence outside the domestic setting; were written in English, Portuguese or Spanish (languages in which the research team were proficient).

We excluded papers that: focused exclusively on intimate partner and/or domestic violence; state violence; poverty; inequality; health promotion; war; cyber victimisation, self-harm (including suicide/suicidal ideation).

Article selection

The first two authors reviewed titles and abstracts of all the references and identified candidate articles for full-text review. The first author reviewed the full-text articles to determine inclusion in the review based on parameters that were developed and refined in discussions between the first three authors.

Data extraction

The first author extracted the following data for all included studies: aims, location, type of violence, type of service sought, details of any intervention, study population, method, key relevant findings.

Data analysis

The characteristics of the studies were first summarised (see ) and presented descriptively to illustrate the type and scope of the included literature. As the studies we identified were extremely heterogeneous both in terms of focus and method used, we used a thematic synthesis approach to summarise the substantive findings. We were broadly guided by a socio-ecological model (Brofenbrenner, Citation1979) where individual, interpersonal, organisational, community and systems level factors interact to impact health care access. Initially the first two authors extracted study findings that reported an association between urban violence and health care access. We then used an inductive approach to identify ten preliminary themes. We mapped these against a conceptual framework of access to health care (Levesque et al., Citation2013) that explores: health care needs; perception of need and desire for care; health care seeking; health care reaching; health care utilisation; health care consequences. In attempting to map our findings against this framework, we realised that several themes needed to be further synthesised. Hence some were expanded and others collapsed into broader thematic categories. This process was undertaken initially by the first 3 authors and later involved the broader interdisciplinary research team, that includes perspectives from public health, health systems, sociology and anthropology. The final agreed themes are presented in the results section.

Table 1. Details of studies included in the scoping review.

Results

Study selection

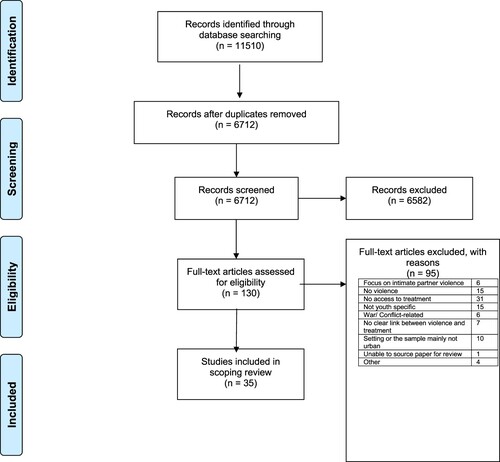

The search identified 11,510 citations, and, following the removal of duplicates, a total of 6712 titles and abstracts were screened for relevance. A total of 6582 articles were excluded at this stage and 130 full-text articles were appraised for eligibility. Of these 95 were excluded, based on assessment using the criteria described above, with 35 articles included in the scoping review ().

Characteristics and study designs

The studies that met the inclusion criteria following the screening process were heterogeneous in relation to: context and population, study objective, violence reported, type of care, and methodological approach.

Over two-thirds (24) of the studies were based in Africa (including 12 from South Africa) and 5 from Central America, 3 from Brazil and 3 based on multi-country studies. There was heterogeneity in the primary objectives of the studies but all included a direct link between experience of interpersonal, community or institutional violence and seeking or receiving health care (mainly SRH or trauma care). In terms of our categorisation of violence, 28 were about interpersonal violence ( nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 24, 25, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34), 20 of which included sexual assault or rape. Five were about community violence ( nos. 17, 18, 21, 31, 32). Twelve were about institutional/systemic violence ( nos. 5, 6, 10, 14, 15, 16, 21, 23, 24, 26, 27, 35). Nine studies included more than one category including one study that reported findings related to all three categories (see nos. 6, 14, 15, 16, 17, 21, 24, 31, 32). The care categories included: 11 receiving post rape/sexual assault or other emergency trauma treatment ( nos. 1, 2, 3, 7, 8, 11, 12, 13, 20, 24, 33); 5 HIV treatment or prevention ( nos. 4, 23, 26, 27, 35); 8 seeking SRH care ( nos. 5, 9, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19, 34); 6 seeking generic health care ( nos. 10, 17, 21, 22, 31, 32); 5 receiving no care with the articles focussing on barriers to care seeking ( nos. 6, 25, 28, 29, 30).

The study populations included young people in the general population mainly those living in low-income neighbourhoods, as well as some specific sub-populations: people living with HIV, sex workers, substance misusers, those with disabilities.

The body of literature is characterised by diverse disciplinary approaches from health services research to psychology and draws on a variety of methodological approaches and study designs. In total, there were 16 quantitative studies (including 1 randomised control trial, 9 based on (mostly cross-sectional) surveys, 6 based on analysis of medical records); 16 qualitative studies (13 using focus groups and/or interviews, 2 ethnographic methods and 1 case study) and 3 using mixed methods.

Themes identified

In relation to the research question what is known about how urban violence impacts access to and delivery of health care for youth, themes were identified. These are displayed in which also links each theme with the associated papers.

Table 2. Themes and papers.

Theme 1: Contexts of violence experienced by youth shape access to services

Structural contexts, including social, political, economic, historical and geographical forces, influence the use of health services. For example, poverty interacts with gender power relations and undermines good reproductive outcomes (Macleod & Feltham-King, Citation2020). Young women who use alcohol or drugs often do not seek support services as they cannot see the potential for their lives to improve. They have also often experienced mistreatment such as exclusion and stigma from service providers (Myers et al., Citation2016). Social norms and (often restrictive and conservative) national laws impact on adolescents’ health decisions resulting from violence and unintended pregnancy whereby the criminalisation of abortion can result in unsafe abortion (Luffy et al., Citation2019).

All the papers included in the scoping review allude to a context in which violence is commonly experienced by young people, yet there is evidence that many do not access care. In a study of adolescents in a low-income area of Johannesburg, 67% of males and 48% of females reported being a victim of violence in the past 12 months. Yet they were generally either unaware of how or where to access support services or doubted their ability to meet their needs (Scorgie et al., Citation2017). In another South African study, 28% of the young women surveyed reported that abuse, sexual harassment and rape were one of their most common life concerns, but 9% indicated that they did not know where to go for help (Lince-Deroche et al., Citation2015). Sexual abuse was reported among young people living in an urban slum in Kampala with 34% affirming that it was alright for a boy to force a girl to have sex if he had feelings for her and 73% affirming that it was common for strangers and relatives to force young females to have sexual intercourse with them without consent (Renzaho et al., Citation2017). However, less than half (48%) had visited a health facility to obtain information about contraception and sexually transmitted infections in the preceding 12 months; and the proportion was significantly lower for younger participants (37.3% vs. 52.8%, p < 0.01).

Within the broader socio-structural context, some groups are particularly vulnerable. In Honduras, among street-based adolescents aged 10–18, 59% self-reported exposure to physical violence in the last year and 44% sexual violence. Yet they were much less likely than adults to access care, with 50% seeking care following severe physical assault and only 14% seeking treatment following severe sexual assault (Navarro et al., Citation2012). Violence, rape, including by gangs (often drug use related) was a key theme reported in focus groups with teenagers in Cape Town who had dropped out of school (Sawyer-Kurian et al., Citation2011), with many women saying they would not disclose rape, including gang rape, due to fear of the perpetrator or other gang members. Among young women who sell sex in Mombasa 30% and 29% respectively had experienced physical and sexual violence, yet there was little awareness of programmes providing support (Roberts et al., Citation2020).

A study of urban poor living in three cities in three separate continents found that violence and/or fear of violence had significant impact on health and well-being, particularly for women. Participants in all three cities described a variety of health issues arising directly from violence, including physical and mental trauma (Maclin et al., Citation2020). They also reported that violence and coping strategies to avoid violence constrained mobility resulting in restricted access to health care. For example, community members in Port-au-Prince said it was unsafe travelling at night and they had to wait until morning to visit a clinic. Respondents in Dhaka said they sometimes avoided seeking health care as the men who worked at the service made them feel unsafe (Maclin et al., Citation2020).

Theme 2: Services that are available are inadequate

There is a need for young people to access safe spaces and efforts to connect adolescents to health care need to build trust (Mmari et al., Citation2016). However, a key theme in the literature was that services often failed to provide this.

Stigma and abuse in treatment settings. A study of an informal residential treatment centre in Mexico City run by marginalised populations shows how violence and care can co-exist (Garcia, Citation2015). Stigma and violence are also reported in formal treatment settings. A study covering four countries reports high rates of physical abuse, verbal abuse, and stigma during childbirth, particularly among younger age groups (Bohren et al., Citation2019). Young pregnant women in a South African township reported poor provider attitudes and numerous health system failures (Macleod & Feltham-King, Citation2020).

Stigma and discrimination can act as a barrier to care. Provider attitudes were cited as a main barrier to SRH care among people with disabilities (Burke et al., Citation2017). Young women recruited from a general population in Soweto, South Africa reported providers unsupportive attitudes and anticipated stigma to be a barrier to accessing SRH services (Lince-Deroche et al., Citation2015). For vulnerable young people living with HIV, enablers to access SRH and HIV services were privacy and confidentiality and limited stigma and discrimination, and barriers included negative attitudes from health providers (Ritchwood et al., Citation2019; Robert et al., Citation2020). Fear of unintended disclosure of HIV status, stigma and discrimination and treatment fatigue negatively influenced adherence in a low-income area in Cape Town (van Wyk & Davids, Citation2019) and can lead to non-retention in HIV care (Pantelic et al., Citation2020).

Sexual-assault care provided generally does not meet need. Provision of post rape care includes post-exposure prophylaxis to HIV (PEP) and/or HIV testing and counselling and sometimes emergency contraception (Akinlusi et al., Citation2014; Daru et al., Citation2011; Gatuguta et al., Citation2018; Muriuki et al., Citation2017). There is evidence that adolescents receive less care than older people (Figueiredo et al., Citation2012; Gatuguta et al., Citation2018) and, with some exceptions (Selenga & Jooste, Citation2015), generally do not receive care needed to address the full range of needs (Place et al., Citation2019).

The literature suggests that there is a range of reasons underlying the inadequate provision of post sexual assault care, particularly for young people. In Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, professionals treating victims of violence feel powerless due to lack of resolution of cases and delays in referrals (Souza da Silva et al., Citation2019). Other studies report: limited availability of PEP or other equipment (Gatuguta et al., Citation2018); poor coordination and/or organisation of services including a lack of training among health care workers (Daru et al., Citation2011; Figueiredo et al., Citation2012; Gatuguta et al., Citation2018; Taquette et al., Citation2017). Stigma is also reported (Gatuguta et al., Citation2018) and prejudice towards adolescent sexual practices and abortion (Figueiredo et al., Citation2012; Place et al., Citation2019).

Theme 3: Low rates of health seeking

A study of adolescents living in low-income urban settlements in five cities across the world found that many do not disclose abuse and/or seek health care often linked to embarrassment, perceived stigma and a lack of trust in the services (Mmari et al., Citation2016). In Johannesburg, more than 30% of adolescents did not seek care even when they knew it was needed. Perceived fear and exposure to community violence was associated with a decreased likelihood of seeking care (Mmari et al., Citation2016). Not seeking support was also linked to gender inequity, whereby women may be stigmatised if they were raped, which may prevent them disclosing or seeking service support (Sawyer-Kurian et al., Citation2011).

Delayed presentation of young people to health services is also reported. Studies based on retrospective analysis of medical records suggest that delayed presentation post sexual assault is common (Akinlusi et al., Citation2014; Badejoko et al., Citation2014; Daru et al., Citation2011; Place et al., Citation2019). Young people are less likely to seek help and more likely to report later than older people (Daru et al., Citation2011; Deschamps et al., Citation2019; Navarro et al., Citation2012). Those more likely to present earlier are those experiencing physical violence during assault (Deschamps et al., Citation2019; Harrison et al., Citation2017) and those assaulted by an unknown person (Harrison et al., Citation2017). Perhaps linked to the inadequacy of much of the care provided, low rates of adherence with sexual assault care are reported (Muriuki et al., Citation2017), with, for example, only 13% of survivors returning for follow-up from a hospital in Nigeria (Badejoko et al., Citation2014).

There is limited knowledge about SRH services. A lack of knowledge of SRH services is reported among particular groups. Young people with disabilities reported very low knowledge about, and use of, SRH services with only 9 out of 50 interviewed ever having accessed SRH services (Burke et al., Citation2017). There was limited knowledge about SRH services among young females living on the street in Cote D’Ivoire and seeking medication from street vendors or a pharmacy was often used for unintended pregnancy, abortion and other SRH concerns (Moss et al., Citation2019). The majority (77%) of young people living in an urban slum in Uganda knew where and how to access contraception, but the proportion was significantly lower among 13–17 year old participants than those who were older (Renzaho et al., Citation2017). Among young women who sell sex, only 26% were aware of any programmes providing services to female sex workers (Roberts et al., Citation2020).

Theme 4: Insufficient attempts to address inadequate services/low uptake

Interventions that build young peoples’ social capital and resilience are essential for reducing violence-related trauma and long-term health and social consequences (Scorgie et al., Citation2017). There are opportunities to target interventions at high risk youth in health care settings as, for example, almost half (47%) of assault-injured youth in emergency centres in Cape Town reported a history of fighting requiring medical treatment in the previous six months (Leeper et al., Citation2017). However, this scoping review identified only three interventions in place to address these issues. Two aimed to enhance youth access to care through developing their empowerment and/or resilience. In a low-income neighbourhood in Johannesburg, a peer club using a structured empowerment approach improved use of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis to HIV and increased self-efficacy and self-esteem (Baron et al., Citation2020). In Kenya, empowerment classes for adolescent girls led to a significantly (P = .001) decreased rate of sexual assaults at follow-up and an increased rate of disclosure from 56% to 75% (P = .006) (Sarnquist et al., Citation2014). In South Africa, a randomised control trial of provision of telephonic psychosocial found that it did not significantly improve PEP adherence among rape survivors (Abrahams et al., Citation2010).

Discussion

This scoping review provides evidence and valuable insights about how exposure to urban violence impacts youth access to sexual, reproductive and trauma health care in LMICs – a topic about which there have not been other reviews.

Two-thirds of the 35 articles we identified were based in Africa including 12 from South Africa and there were 5 from Central America and 3 from Brazil reflecting the high levels of urban violence in these areas in the global South (Salahub et al., Citation2019). The majority of articles focused on SRH including sexual assault rather than physical trauma and there were more that focused on young women than men.

There was diversity in terms of primary aims, methods and samples but some clear themes nevertheless emerged. The scoping review has confirmed that young people living in low-income urban settings experience their environments and interpersonal relationships as violent and this has a negative impact of their access to health care. All the papers reviewed either presented evidence or implied that violence constituted a structural part of everyday life. They illustrated how violence in the community operates, e.g. through conflicts involving drug dealers, gangs or local police. These are portrayed as sporadic and normalised (Scorgie et al., Citation2017). This suggests that there is a need to focus on power relations and structural inequalities, rather than individual responsibility in terms of understanding and addressing youth access to health care. Poverty interacts with gender power relations in a way which undermines young women’s pursuit of sexual and reproductive justice (Macleod & Feltham-King, Citation2020). Gender inequality and stigma toward young women who use alcohol or drugs leads to their social exclusion from education and employment opportunities and health care (Myers et al., Citation2016). Urban violence and structural inequalities can limit how young people move about the community and restricts access to health care (Maclin et al., Citation2020). It is also linked to desensitisation to violence whereby violence is not always reported or recognised as such with high rates of non-disclosure of violence and non-presentation or late-presentation to health care (Navarro et al., Citation2012). Young people may fail to seek care when they need it often because of a lack of trust in providers or embarrassment or feeling stigmatised for seeking services (Mmari et al., Citation2016).

They may also be deterred by the quality of health care services, which in many cases were inadequate. Institutional violence within health services, often in the form of stigma, discrimination and/or hostile attitudes towards young people emerged as a key issue (Lince-Deroche et al., Citation2015). Youth report that they do not feel welcome and are discriminated against, feeling that health professionals have a moralistic reproach to what they do or say (Burke et al., Citation2017; Lince-Deroche et al., Citation2015). This may impact on youth access to services and on adherence to treatment (Ritchwood et al., Citation2019).

Vulnerability in terms of violence’s impact on sexual and mental health requires an intersectional understanding and integrated approach to providing health services (Moss et al., Citation2019). Despite this, and the barriers to young people accessing health care in areas with high levels of urban violence, there is a paucity of literature based on interventions that address the impact of violence on health care access in LMIC settings. The three studies we identified (Abrahams et al., Citation2010; Baron et al., Citation2020; Sarnquist et al., Citation2014) all focused on modifying the behaviour of individuals. The ubiquity of violence in some low-income urban environments, which impacts on both young people and those involved in the delivery of care, would suggest that a whole-system approach would be most effective.

There are several examples of intervention studies to draw on reported in systematic reviews or in non-LMIC settings, which due to our criteria for papers based on primary data, were not included in our review. For example, a systematic review of studies of SRH interventions for young people in LMIC and humanitarian settings suggests preliminary support for the effectiveness of several evidence-based SRH interventions targeting young people in humanitarian and low resource settings. However, there were a number of methodological weaknesses identified in this body of literature, e.g. short follow-up periods and few studies that focused on the feasibility, implementation and sustainability of interventions on a broad scale (Desrosiers et al., Citation2020). A systematic review of intervention programmes conducted across the globe (not just LMIC settings) targeting gender inequality among young people found that they generally focus on improving individual agency, rather improving broader systems (Levy et al., Citation2020). There is, however, recognition that multisectoral perspectives are required to address youth violence (Bolton et al., Citation2017).

Limitations

A major limitation of this scoping review was the breadth of the literature searched, due to the exploratory nature of our project. We identified a vast range of different types of studies focusing on varying aspects of urban violence and youth access to health care. This made summation a challenge as the studies were not comparing like with like and their aims and outcomes were very varied. In addition, our requirement that papers had to include links between urban violence and youth health care access meant that there were many papers of interest about either violence or health care access alone that we could not include. Most notably were the many intervention studies that aimed to tackle either violence or health care access but not both. A further limitation is that we did not assess the quality of the papers, selected although all were published in peer-reviewed journals.

In addition, it should also be noted that the search on which this review is based was carried out in early July 2020 and some important studies published in the intervening period between our study ending and publication may have been missed. Also, this is not a global review as we did not include papers based on data from high-income countries. It nevertheless provides a very useful body of evidence for countries which face similar developmental and health related issues.

Conclusions and recommendations

Urban violence is a structural and systemic issue that, particularly in low-income areas in LMICs, both determines health and frames the conditions for accessing health care. It impacts on who and who does not seek health care, what type of services they seek, which services are developed and the experiences of care provided. This suggests that a multi-sectoral approach involving inter-disciplinary and cross-sector collaboration is required to minimise the negative impact of violence on youth access to health care. We would also recommend the creation of a global repository to harness knowledge and practice in the area.

There is a clear need for feasible interventions which address broader issues of violence and youth access to health care. Many interventions take a top-down approach rather than working with the communities, although violence prevention initiatives that have used community participatory approaches, for example carried out in the United States (Kia-Keating et al., Citation2017), provide clear evidence that community engagement is key to implementation, scale-up and sustainability in high-violence, low resource settings (Shadowen et al., Citation2017). This would suggest that community engagement and a multi-sectoral approach are key to ameliorate the impact of violence on youth health care access.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (13.7 KB)Acknowledgements

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. Any opinion, finding and conclusion or recommendation expressed in this material is that of the author and the NIHR does not accept any liability in this regard.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abrahams, N., Jewkes, R., Lombard, C., Mathews, S., Campbell, J., & Meel, B. (2010). Impact of telephonic psycho-social support on adherence to post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) after rape. AIDS Care, 22(10), 1173–1181. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121003692185

- Akinlusi, F. M., Rabiu, K. A., Olawepo, T. A., Adewunmi, A. A., Ottun, T. A., & Akinola, O. I. (2014). Sexual assault in Lagos, Nigeria: A five year retrospective review. BMC Women’s Health, 14(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-14-115.

- Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Badejoko, O. O., Anyabolu, H. C., Badejoko, B. O., Ijarotimi, A. O., Kuti, O., & Adejuyigbe, E. A. (2014). Sexual assault in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Nigerian Medical Journal: Journal of the Nigeria Medical Association, 55(3), 254–259. https://doi.org/10.4103/0300-1652.132065

- Baron, D., Scorgie, F., Ramskin, L., Khoza, N., Schutzman, J., Stangl, A., Harvey, S., Delany-Moretlwe, S., & Team, E. S. (2020). You talk about problems until you feel free: South African adolescent girls’ and young women’s narratives on the value of HIV prevention peer support clubs. BMC Public Health, 20(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09115-4

- Body-Gendrot, S. (1995). Urban violence: A quest for meaning. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 21(4), 525–536. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.1995.9976510

- Bohren, M. A., Mehrtash, H., Fawole, B., Maung, T. M., Balde, M. D., Maya, E., Thwin, S. S., Aderoba, A. K., Vogel, J. P., Irinyenikan, T. A., Adeyanju, A. O., Mon, N. O., Adu-Bonsaffoh, K., Landoulsi, S., Guure, C., Adanu, R., Diallo, B. A., Gülmezoglu, A. M., Soumah, A.-M., & Sall, A. O. (2019). How women are treated during facility-based childbirth in four countries: A cross-sectional study with labour observations and community-based surveys. Lancet, 394(10210), 1750–1763. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31992-0

- Bolton, K. W., Maume, M. O., Jones Halls, J., & Smith, S. D. (2017). Multisectoral approaches to addressing youth violence. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 27(7), 760–767. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2017.1282913

- Bowers, L. G. (2008). Does your hospital have a procedure for recognizing and responding to gang behavior? Journal of Healthcare Protection Management, 24(2), 80–83. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18800664/.

- Brofenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press.

- Burke, E., Kebe, F., Flink, I., van Reeuwijk, M., & le Maye, A. (2017). A qualitative study to explore the barriers and enablers for young people with disabilities to access sexual and reproductive health services in Senegal. Reproductive Health Matters, 25(50), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2017.1329607

- Cooper, D., Green, G., Tembo, D., & Christie, S. (2019). Levels of resilience and delivery of HIV care in response to urban violence and crime. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(8), 1723–1731. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14022

- Daru, P. H., Osagie, E. O., Pam, I. C., Mutihir, J. T., Silas, O. A., & Ekwempu, C. C. (2011). Analysis of cases of rape as seen at the Jos University Teaching Hospital, Jos, north central Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice, 14(1), 47–51. https://doi.org/10.4103/1119-3077.79240

- de Ribera, O. S., Trajtenberg, N., Shenderovich, Y., & Murray, J. (2019). Correlates of youth violence in low- and middle-income countries: A meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 49, 101306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2019.07.001

- Deschamps, M. M., Theodore, H., Christophe, M. I., Souroutzidis, A., Meiselbach, M., Bell, T., Perodin, C., Anglade, S., Devieux, J., Cremieux, P., & Pape, J. W. (2019). Characteristics and psychological consequences of sexual assault in Haiti. Violence and Gender, 6(2), 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1089/vio.2018.0005

- Desrosiers, A., Betancourt, T., Kergoat, Y., Servilli, C., Say, L., & Kobeissi, L. (2020, May). A systematic review of sexual and reproductive health interventions for young people in humanitarian and lower-and-middle-income country settings. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08818-y

- Fernandes, H., Sala, D. C. P., & Horta, A. L. M. (2018). Violence in health care settings: Rethinking actions. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 71(5), 2599–2601. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2017-0882

- Figueiredo, R., Bastos, S., & Telles, J. L. (2012). Profile of the free distribution of emergency contraception for adolescents in São Paulo’s counties. Journal of Human Growth and Development, 22(1), 105–115. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84863991864&partnerID=40&md5=b61dbb94b2542b6b89853460b1091ba8. https://doi.org/10.7322/jhgd.20058

- García-Moreno, C., Hegarty, K., d'Oliveira, A. F. L., Koziol-McLain, J., Colombini, M., & Feder, G. (2015). The health-systems response to violence against women. The Lancet, 385(9977), 1567–1579. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61837-7

- Garcia, A. (2015). Serenity: Violence, inequality, and recovery on the edge of Mexico city. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 29(4), 455–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12208

- Gatuguta, A., Merrill, K. G., Colombini, M., Soremekun, S., Seeley, J., Mwanzo, I., & Devries, K. (2018). Missed treatment opportunities and barriers to comprehensive treatment for sexual violence survivors in Kenya: A mixed methods study. BMC Public Health, 18(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5681-5

- Harrison, R. E., Pearson, L., Vere, M., Chonzi, P., Hove, B. T., Mabaya, S., Chigwamba, M., Nhamburo, J., Gura, J., Vandeborne, A., Simons, S., Lagrou, D., De Plecker, E., & Van den Bergh, R. (2017). Care requirements for clients who present after rape and clients who presented after consensual sex as a minor at a clinic in Harare, Zimbabwe, from 2011 to 2014. PLoS One, 12(9), e0184634. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184634

- Kia-Keating, M., Santacrose, D. E., Liu, S. R., & Adams, J. (2017, Apr–Jun). Using community-based participatory research and human-centered design to address violence-related health disparities among Latino/a youth. Family & Community Health, 40(2), 160–169. https://doi.org/10.1097/fch.0000000000000145

- Kinsler, J. J., Wong, M. D., Sayles, J. N., Davis, C., & Cunningham, W. E. (2007). The effect of perceived stigma from a health care provider on access to care among a low-income HIV-positive population. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 21(8), 584–592. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2006.0202

- Leeper, S., Lahri, S., Myers, J., Patel, M., Martin, I. B. K., & Van Hoving, D. J. (2017). Assault-injured youth in the emergency centers of Khayelitsha, South Africa: Population characteristics and opportunities for intervention. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 70(4), S65–S66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.07.190

- Levesque, J.-F., Harris, M. F., & Russell, G. (2013). Patient-centred access to health care: Conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. International Journal for Equity in Health, 12(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-12-18

- Levy, J. K., Darmstadt, G. L., Ashby, C., Quandt, M., Halsey, E., Nagar, A., & Greene, M. E. (2020, Feb). Characteristics of successful programmes targeting gender inequality and restrictive gender norms for the health and wellbeing of children, adolescents, and young adults: A systematic review. Lancet Global Health, 8(2), E225–E236. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(19)30495-4

- Lince-Deroche, N., Hargey, A., Holt, K., & Shochet, T. (2015). Accessing sexual and reproductive health information and services: A mixed methods study of young women’s needs and experiences in Soweto, South Africa. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 19(1), 73–81. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26103697/.

- Luffy, S. M., Evans, D. P., & Rochat, R. W. (2019). Regardless, you are not the first woman: an illustrative case study of contextual risk factors impacting sexual and reproductive health and rights in Nicaragua. BMC Women’s Health, 19(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-019-0771-9

- Macleod, C. I., & Feltham-King, T. (2020). Young pregnant women and public health: Introducing a critical reparative justice/care approach using South African case studies. Critical Public Health, 30(3), 319–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2019.1573313

- Maclin, B. J., Bustamante, N. D., Wild, H., & Patel, R. B. (2020). To minimise that risk, there are some costs we incur: Examining the impact of gender-based violence on the urban poor. Global Public Health, 15(5), 734–748. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1716036

- Matzopoulos, R., Bowman, B., Butchart, A., & Mercy, J. A. (2008). The impact of violence on health in low- to middle-income countries. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion, 15(4), 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457300802396487

- Michelman, B., & Patak, G. (2008). Gang culture from the streets to the emergency department. Journal of Healthcare Protection Management, 24(1), 23–30. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18409448/

- Mmari, K., Marshall, B., Hsu, T., Ji Won, S., Eguavoen, A., & Shon, J. W. (2016). A mixed methods study to examine the influence of the neighborhood social context on adolescent health service utilization. BMC Health Services Research, 16(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1597-x

- Moss, T., Muriuki, A. M., Maposa, S., & Kpebo, D. (2019). Lived experiences of street girls in Cote d’Ivoire. International Journal of Migration Health and Social Care, 15(2), 150–162. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijmhsc-12-2017-0052

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- Muriuki, E. M., Kimani, J., Machuki, Z., Kiarie, J., & Roxby, A. C. (2017). Sexual assault and HIV postexposure prophylaxis at an urban African hospital. AIDS Patient Care & STDs, 31(6), 255–260. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2016.0274

- Myers, B., Carney, T., & Wechsberg, W. M. (2016). Not on the agenda: A qualitative study of influences on health services use among poor young women who use drugs in Cape Town, South Africa. International Journal of Drug Policy, 30, 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.12.019

- Nation, M., Chapman, D. A., Edmonds, T., Cosey-Gay, F. N., Jackson, T., Marshall, K. J., Gorman-Smith, D., Sullivan, T., & Trudeau, A.-R. T. (2021). Social and structural determinants of health and youth violence: Shifting the paradigm of youth violence prevention. American Journal of Public Health, 111(S1), S28–S31. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2021.306234

- Navarro, J. R., Cohen, J., Arechaga, E. R., & Zuniga, E. (2012). Physical and sexual violence, mental health indicators, and treatment seeking among street-based population groups in Tegucigalpa, Honduras. Revista Panamericana De Salud Publica-Pan American Journal of Public Health, 31(5), 388–395. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1020-49892012000500006

- Pantelic, M., Casale, M., Cluver, L., Toska, E., & Moshabela, M. (2020). Multiple forms of discrimination and internalized stigma compromise retention in HIV care among adolescents: Findings from a South African cohort. Journal of the International Aids Society, 23(5), e25488. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25488

- Parker, R. (2012). Stigma, prejudice and discrimination in global public health. Cadernos de Saude Publica, 28(1), 164–169. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-311(2012000100017

- Place, J. M. S., Billings, D. L., & Valenzuela, A. (2019). Women’s post-rape experiences with Guatemalan health services. Health Care for Women International, 40(3), 278–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2018.1545230

- Renzaho, A. M. N., Kamara, J. K., Georgeou, N., & Kamanga, G. (2017, Jan). Sexual, reproductive health needs, and rights of young people in slum areas of Kampala, Uganda: A cross sectional study. PLoS One, 12(1), e0169721. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169721

- Ritchwood, T. D., Ba, A., Ingram, L., Atujuna, M., Marcus, R., Ntlapo, N., Oduro, A., & Bekker, L.-G. (2019). Community perspectives of South African adolescents’ experiences seeking treatment at local HIV clinics and how such clinics may influence engagement in the HIV treatment cascade: A qualitative study. AIDS Care, 32(1), 83–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2019.1653442.

- Robert, K., Maryline, M., Jordan, K., Lina, D., Helgar, M., Annrita, I., Wanjiru, M., & Lilian, O. (2020). Factors influencing access of HIV and sexual and reproductive health services among adolescent key populations in Kenya. International Journal of Public Health, 65(4), 425–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-020-01373-8

- Roberts, E., Ma, H. T., Bhattacharjee, P., Musyoki, H., Gichangi, P., Avery, L., Musimbi, J., Tsang, J., Kaosa, S., Kioko, J., Becker, M. L., Mishra, S., & Transitions Study, T. (2020). Low program access despite high burden of sexual, structural, and reproductive health vulnerabilities among young women who sell sex in Mombasa, Kenya. BMC Public Health, 20(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08872-6

- Salahub, J. E., Gottsbacher, M., de Boer, J., & Zaaroura, M. D. (Eds.). (2019). Reducing urban violence in the global south. Routledge.

- Sarnquist, C., Omondi, B., Sinclair, J., Gitau, C., Paiva, L., Mulinge, M., Cornfield, D. N., & Maldonado, Y. (2014). Rape prevention through empowerment of adolescent girls. Pediatrics, 133(5), E1226–E1232. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-3414

- Sawyer-Kurian, K. M., Browne, F. A., Carney, T., Petersen, P., & Wechsberg, W. M. (2011). Exploring the intersecting health risks of substance abuse, sexual risk, and violence for female South African teen dropouts. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 21(1), 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2011.10820425

- Scorgie, F., Baron, D., Stadler, J., Venables, E., Brahmbhatt, H., Mmari, K., & Delany-Moretlwe, S. (2017). From fear to resilience: Adolescents’ experiences of violence in inner-city Johannesburg, South Africa. BMC Public Health, 17(S3), 441. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4349-x

- Selenga, M., & Jooste, K. (2015). The experience of youth victims of physical violence attending a community health centre: A phenomenological study. Africa Journal of Nursing & Midwifery, 17(3), S29–S42. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ccm&AN=116066806&site=ehost-live. https://doi.org/10.25159/2520-5293/214

- Shadowen, N. L., Guerra, N. G., Rodas, G. R., & Serrano-Berthet, R. (2017). Community readiness for youth violence prevention: A comparative study in the US and Bolivia. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 12(2), 117–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450128.2017.1286423

- Souza da Silva, M., Marten Milbrath, V., Lucia Freitag, V., Bärtschi Gabatz, R. I., Stragliotto Bazzan, J., & Lemes Maciel, K. (2019). Care for children and adolescents victims of violence: Feelings of professionals from a psychosocial care center. Anna Nery School Journal of Nursing/Escola Anna Nery Revista de Enfermagem, 23(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1590/2177-9465-EAN-2018-0215

- Taquette, S. R., Monteiro, D. L. M., Rodrigues, N. C. P., Rozenberg, R., Menezes, D. C. S., Rodrigues, A. D. O., & Ramos, J. A. S. (2017). Sexual and reproductive health among young people, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Ciencia & Saude Coletiva, 22(6), 1923–1932. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232017226.22642016

- van Wyk, B. E., & Davids, L. A. C. (2019). Challenges to HIV treatment adherence amongst adolescents in a low socio-economic setting in Cape Town. Southern African Journal of HIV Medicine, 20(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhivmed.v20i1.1002

- World Health Organization. (2002). World report on violence and health: Summary. https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/en/summary_en.pdf.

- World Health Organization. (2015). Preventing youth violence: An overview of the evidence. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/181008.

- World Health Organization. (2020). Global status report on preventing violence against children. Geneva: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health/violence-prevention/global-status-report-on-violence-againstchildren-2020

- Wright, A. W., Austin, M., Booth, C., & Kliewer, W. (2016). Systematic review: Exposure to community violence and physical health outcomes in youth. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 42(4), 364–378. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsw088