ABSTRACT

Pleasure and protagonism are two words that define Maria de Jesus Almeida Costa, or Dijé, as friends call her. She was just an adolescent when she first arrived in the São Luiz red light district and began to fight against the violence and injustice she witnessed. Today, she is 62 years old and the leader of the sex worker movement in the Brazilian state of Maranhão, in the Northeast region of the country. She is widely recognised for her tireless fight for the preservation of the historical centre of São Luiz where the red light district remains to this day, and where Jesus also raised her children and lives to this day. In this interview, Jesus talks about the pleasures and dangers of prostitution, her fight against racism and sex work stigma, her relationship with the academy and researchers, the alliances and partnerships she mobilised during the Covid-19 pandemic and the challenges that she is facing in Brazil’s current conservative, far-right government.

Brief introduction to Maria de Jesus and the Brazilian sex worker movement

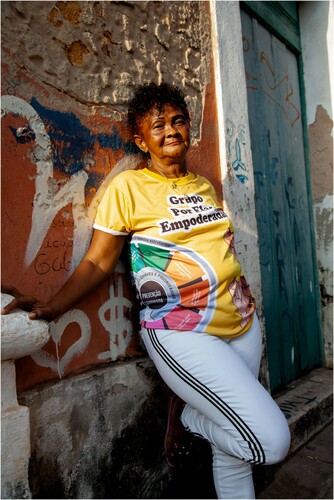

Maria de Jesus Almeida Costa, 62 years old, is from the Brazilian state of Maranhão, in Brazil’s Northeast region. She came to the state’s capital when she was 12 years old. She first worked as a nanny, maid and washed clothes prior to abandoning these jobs and making her way to the July 28th Street, in the heart of the city’s red light district. There she participated in institutions like the Catholic Church’s Casa Ninho, that offered schooling for children of sex workers. She was an activist in the sex worker and Black women’s movement as part of GRUCON (The Group of Black Unity and Consciousness) and entered into the fight against HIV/AIDS in the early years of the epidemic as part of several local NGOS prior to founding APROSMAFootnote1 (The Association of Prostitutes from Maranhão). Today, Jesus, or Dije as her friends call her, is the leader of the prostitute movement in Maranhão, a member of the Brazilian Network of ProstitutesFootnote2 and also the coordinator the Collective for Empowered Women (Coletivo por Elas Empoderadas)Footnote3 in São Luiz (the capital city of Maranhão) ().

Figure 1. Photograph of Maria de Jesus in the Historic Center of São Luis, state of Maranhão. Credit: Jefferson Santiago.

The sex worker movement in Brazil emerged in the 1980s led by Gabriela Leite and Lourdes Barreto who focused their early activism on fighting against police violence, prostitution stigma and affirming prostitution as work. The movement’s early years coincided with the HIV epidemic, and sex workers in Brazil – similar to many other countries – were stigmatised by the media and early State-funded programmes as a ‘risk group’ and often treated as victims needing to be ‘rescued’ from the red light district. Over time, their relationship with the State and other social movements raised questions about identity and terminologies – especially around the words, ‘sex worker’, ‘prostitute’, and ‘puta’ (whore). The dichotomy between the sphere of work and sexual rights reflects an internal discussion in the sex worker movement about the moral standards that discriminate against prostitutes and relegate them to subaltern conditions. Currently, the Brazilian sex worker movement is divided into three national networks: the Brazilian Network of Prostitutes (RBP – acronym in Portuguese), the National Articulation of Sex Professionals (ANPROSEX – acronym in Portuguese) and Unified Front of Sex Workers (CUTS - acronym in Portuguese). This division reflects both the regionalisation of the movement and different political strategies and relationships with the Brazilian State. Jesus is a member of the Brazilian Network of Prostitutes yet always works in close partnership with CUTS and ANPROSEX, because, true to Jesus’ deep sense of solidarity, she believes that all of the networks should fight as one.

I am a researcher and activist-collaborator the Collective for Empowered Women. I have worked closely with Jesus since 2017 in São Luís. In this interview that I conducted with her in 2021, we get a sense of her life history from an intersectional perspective (Collins & Bilge, Citation2020). She talks about the pleasures and dangers of prostitution, about her militancy, the Brazilian sex worker movement and the diverse partnerships and challenges that she is facing in Brazil’s current conservative, far-right government.

Arriving in the red light district

Fernanda Ribeiro (FR): What took you to the São Luis red light district when you were 12 years old?

Maria de Jesus (MJ): My friend and I would leave the houses where we were working as nannies and maids to go out, and we often went out in the cabaret because it was close. I was attracted to the party environment. When I went to see the area for the first time, there was so much going on, all of the bars had music. My friend and I thought we were at a party, we didn’t know that it was a brothel. To me it was a party street, not a street of prostitution.

Around this time, I quit my job as a nanny. I was still a minor, I think I was going to turn 13, and my friend Victoria and I decided to gather our things, but our boss wouldn’t give them to us. She only gave us a skirt and a dress. We took what little she gave us and went back to the red light district to rent a room. Our suitcase was just a plastic bag with our clothes. A young man who had a bar and pension that rented rooms to sex workers let us stay there. It wasn’t exactly a brothel. He let us stay as long as we paid the daily fee. We asked for money to pay for the room. Some people, the men who came to the bar, gave us some change, because neither she nor I were women … we were practically still children.

I was really pretty, a little chubby. I was really perfect. But I didn’t go to the rooms (with clients) because I couldn’t withstand it, you understand? And then when I was about 14, we started having other needs. I met an older man, who was a client of this bar and liked me. He was really rich. He was very white, kind, and pretty old at the time. My friend and I were late on our rent. We forgot to pay every day, we only remembered to party. The owner called us out in front of this man and said we were going to have to leave since we hadn’t paid. We cried, I made a scene, and this older man was sitting there. I didn’t have anywhere to go because my aunt didn’t want me anymore, because she had discovered that I was in the cabaret.

The man saw me crying and called me over to his table. I sat down, and he started to talk with me, asked how old I was, blah blah blah … Then he called the owner of the house over and said, ‘Oh, how much does she owe?’. The owner of the bar was a thug and he made up the amount, if he was 100 he must have said 500. The old guy said: ‘no, take it easy, I’ll pay. From now on she stay in this room, I’ll pay for everything’. Only I wasn’t supposed to leave. You understand? I was married and I didn’t know. I was married to the old guy. I took care of him, but the owner watched over me to make sure I wouldn’t cheat. Only I didn’t sleep with the old man, he came, drank, then he went to sleep. He’d go to sleep and I‘d just watch him.

And then I saw the old guy with another man. I understood what was going on and I relaxed a bit. Then I met a popsicle vender. I think I was about 15 and this popsicle vender came everyday at noon to bring money for my food. Then I traded the popsicle man for someone else. Everything started to go really fast as I began having sex and switching men.

Entry into political activism

FR: In the red light district you also had contact with a lot of institutions that were a jumping off point for your training in politics. Could you tell us a little bit about this trajectory?

MJ: I started at the Ninho, which was a school for the children of prostitutes and others. Younger prostitutes could also study there, if they wanted to. Since I was a minor I went to study at the Ninho. The Ninho wasn’t rigid, but it had all this, ‘Please God, free me from this life that I live’ talk. It was a Church institution, and it had that victimising thing going on. They did good work, but from a victimising perspective. The Ninho had powerful partnerships with politicians’ and judges’ wives and they were able to get me into the Santa Tereza high school. Maybe because I was the most rebellious one, maybe because I was the one who most fought back against things … I studied at Santa Tereza at night, until 10PM and then I’d go to the cabaret. During the day I’d do a bunch of courses at the Ninho for manicurists, hair stylists, first responders, seamstresses. I did all of these courses while studying at Santa Tereza, and then in the last few years of high school, I paid for an intensive course to be able to finish.

By this time I had another head on my shoulders. I started to be a part of The Black Unity and Consciousness Organization (GRUCON – acronym in Portuguese), the first Black organisation in São Luiz. I was a part of this group for some time. I travelled a lot with them and talked about prejudice. I always talked about Black issues, about Black prostitutes. I represented these issues really well with the group.

And then in 1989, more or less, AIDS explodes. Around this time I met a person from Rio who said: ‘Jesus, I’m starting a partnership with a group that is called InterAids,Footnote4 here in Brazil, do you want to be a part of it?’. And I said, ‘Yes, what is it like?’. And he said, ‘they’re going to call some people from Maranhão to work, do AIDS education and prevention, preferably the whores and there should also be a gay man’.

Why whores? Because we spoke the language of the cabarets. I mean, the coordinator didn’t have it, the group social worker didn’t have it. We did because the language was ours. I’m a whore and I can arrive at the nightclub and talk to you whore to whore, right? A social educator, he can't do that, it’s not his fault, he just isn’t politicised for that. And that’s how we started this work. I went with three prostitutes just like me, a gay friend of ours and two other colleagues who weren’t prostitutes but who were called upon to work. We did conscientisation work in more than 100 brothels in Maranhão and we worked every day.

And then we started to lose a lot of friends. Friends and friends of so many friends. And since we were on the frontlines, with our trans colleagues, we lost so many. We lost so many friends. Then there was a huge attack, with people calling it a gay disease, that prostitution was spreading it … but sex workers never took the brunt of it, because generally in reports, campaigns and research we were never at the top (of the prevalence rates). There was a big study and we had 4% (prevalence). We always did a good job with prevention, talked about how to have safe sex, all that.

Then the Maranhão State STD/AIDS programme was created and we started a group called GEAD (Group to Fight HIV/AIDS) that had more than 100 people, people that really stood up for the cause. We weren’t priests. We were people losing their colleagues who went out to fight.

This is a little different than Covid-19, right? Covid-19 scares you as much as it scares me. It’s impossible for people not to express solidarity, but we also can’t be close to one another. AIDS gave us this opening to express solidarity without being afraid of having contact, of facing people face to face. And this was cool because we worked for something, we worked on prejudice, because it was a time when what killed was prejudice, not AIDS.

Founding São Luis’s first sex worker organisation

FR: How did APROSMA (The Association of Sex Workers in Maranhão) come about?

MJ: First we started GEAD, it was very active. But then there came a time came when we started to see that what’s yours is yours. We have to be partners, walk together, fight together, work a lot, but who has to talk about gay politics are gays, and travesti politics, travestis. The travestis also worked the strip in downtown São Luis, they spent a lot of time with us, because they were sex workers and shared space with whores. So we worked on policies for whores and travestis together.

Around this time, a person who was part of our group was killed after they told some guys he went out with that he was HIV positive. They killed and buried him. We spent weeks looking for him before discovering he had been killed. It was very painful for us, so painful. So after that happened, it wasn’t just AIDS that we worked on, we started also working on violence because we were also losing people to violence.

In 2001, we started to think that the group format wasn’t working and we started to organise as an association. People started to get tired of doing things for free. The State always called on us to work together, and we ended up working for free, but we didn’t want to take the women out of the cabaret to earn nothing. We founded APROSMA in 2003 and

today we are part of the Coletivo Por Elas Empoderadas (The Collective for Empowered Women), which has women from the Women’s Secretariat, the Legislative Assembly, the health post. These women aren’t whores, but they fight with us. I think that it is much more viable to have these people in the group, who will make a difference in the places they are, instead of having an entity where members just stay in their own contexts.

So it’s a group walking together as a network. There are women in the cabaret that want to be a part of the group, who says, ‘Oh, I want to be a part of these group’ and why not? Come here, be an empowered woman!

I know that I’ve been a stone in the shoe of some people because I’ve always let people be very free. I think that we need to have a movement that is a movement of freedom. So if I want to be a whore, I’ll be a whore. If I want to be a working girl, I’ll be a working girl.Footnote5 My role as an activist is to respect what a woman wants to be at that moment. Because if I don’t, I disrespect that women need to be where they want, and do what they want. I’m in the prostitute movement, but Fernanda doesn’t need to be in the movement and say, ‘I’m a prostitute’. Fernanda is in the movement because she is a person who supports the movement, she stands up for it and she knows the politics. I can’t make you say, ‘I’m in the prostitute movement. I’m a prostitute’. No. ‘I’m a professor, I’ve got a college degree, I’m in the prostitute movement because I like the fight, and that’s enough.’

Stigma, racism and violence

FR: What about the presence of stigma and violence in prostitution and your activism today?

Prostitution today has advanced. We say it hasn’t, but it has. It has advanced because the prostitution of years ago stayed in history, and it was very cruel. The women went to the room, and if she didn’t do everything that the man wanted, he hit her, and she went back out to the main room, she had to justify why she didn’t do what was asked. And the owner would think that the client was right, because the client was paying. The client paid for the drinks, the client got the key … that was the misinformation that people had. Today that doesn’t happen anymore because there is more information. Before only women considered pretty earned well, those who were considered less attractive earned less. And if you were Black, you were even less, and worked in conditions of much more vulnerability.

Today, women continue to be vulnerable in places that have violence, prejudice and sickness. Sometimes as women, we have prejudices towards ourselves that we don’t recognise. We stop doing something because we say, ‘Oh, I’m not going to study because I’m a whore. I’m not going to mass because I’m a whore, I’m not going to the show because I’m a whore … ’. That is within us because we carry it around almost like a culture. 'Whores can’t do this, they can’t do that.'

But whores can do anything! We build things stone by stone. If a whore is studying, even if she’s at the university she doesn’t stop being a whore for society. So I think that some things really need to be discussed. Because people still face a lot of prejudice to work, but as I said, things have advanced. We have advanced because now there are people who stand up without shame and fight.

FR: Within all of these struggles for sex worker rights, what has it been like to fight as a Black woman?

MJ: It’s another acronym, another title. Being a whore, poor and Black. Black whores have two strikes against them, that is being Black and a whore. Because we know that Black is Black. Black is Black! No matter where they are. In whatever instance they can be rich, but they won’t be more than a Black rich man. People say things like this: ‘Damn! So and so has a lot of money, but shit, he’s Black. I know a bunch of Blacks with white souls. That girl is pretty as shit, but it’s because Black women are hotter’.

Today these things aren’t said so much, but if you go to a bar and you see three white women and three Black women, who’s the first one to go to the room? The white women. Even if the Black women are sexier, the white women go first. Take another context, the prisons, what colour is most common in the prison system? Black. If you go out and look at who is living on the street, who do you see? Black men and women.

But in prostitution, there are more white women than black women. This is something for us to understand. I think that this is related to prejudice. ‘Damn, aside from being Black, I’m going to go to the cabaret and be a whore? No, no that won’t work.’ I think that they avoid it and I don’t know if that’s historic, but I know that it’s true. Another example, in the fanciest brothels, there are more white women, they are preferred. And I’m not saying that with bitterness, it’s true. I felt this myself. You hear things like, ‘She’s Black, but she’s pretty. She’s Black, but she’s hot. I’m going with her because she’s a hot Black woman, she’s got a big butt.’ These are some things that we need to understand more.

Once I was in Goiânia (a state) with the Black Movement for a mission, and at night we got all dressed up to go out to a bar and drink. When we got to the door of the party, we were stopped. We didn’t go in because they said that it was invitation only. But later we discovered that it wasn’t, it was a question of colour, understand?

Another time I started a relationship with a person and I left him because he told his friends, ‘look, I have two women because I had a strong desire to know the taste of a Black woman and a white woman’. That bitterly offended me. It offended me a lot. The person was only with me to know the taste of a Black woman.

Relationship with researchers

FR: Throughout these years, what has your relationship been like with researchers and academic institutions?

MJ: It’s been good, but I think that up until recently researchers used us a lot. For example, they'd come to do a study saying, ‘Oh I’m studying social work, I’m studying law, I’m doing this or that and I’m studying prostitution … ’. And we spilled everything, talked a bunch, but then they would use what we said and leave. For them it was great, because we’d run into them and they’d say, ‘we got a 10 on our project’. That’s how it usually goes, but then we started to pay more attention and wake up to the fact that it shouldn’t be like that. If we were going to share a bunch about our work, intimate details of our lives, talk about everything, then we have to have something in return. Not a financial return, but true exchange about what was learned.

Usually the first thing that we notice with researchers is prejudice. They come armed and we need to disarm them, right? Because it’s not their fault that they come armed with prejudices. Sometimes they get surprised by things, such as, ‘Ah! I thought that prostitution was related to violence, robbery, and it’s not, is it?’. They were educated to think that. That women who are prostitutes aren’t worth anything, that they steal husbands, take bread from children and that’s not true. So we questioned a lot of that. I tell all of them, ‘I’ll get you a good grade, but what are you going to give me in return?’ ‘You are coming with questions, but I also need to question you. What are you going to do with this information? Are you going to use them for something worthwhile in your life? Someone opened up to you and you just used that to benefit yourself?’

I think that we need to do it [research], because we can’t die holding all this just for ourselves; we need to pass on this knowledge to someone. I think that people that are in the universities need to understand, they need to know, and it is part of our duties to make them know, even knowing at the time that it isn’t going to result in anything. But they need to at least hear truths directly from the people who have lived them.

As whores and activists it's important that we have dialogues with people who influence opinions, make laws. I think though that the impact when you talk about your life is much more with the person who asked about it. The impact isn’t for us, it’s for who we are responding to, who ends up either leaving the interview lighter or heavier (laughs), or better informed. So sometimes, we do get a good return on our time, but that is only 5%, because the rest of the time we lose. The rest of the time is like this, ‘I got a 10, great!’, and so what?! But that’s life.

Politics and alliances

FR: You are legendary for your ability to form partnerships and do politics. What is your secret for mobilising so many people around the cause of sex worker rights?

MJ: I always say that in an organised movement, no one has a party, we don’t have political parties because we are politics. Our political party is whore. The DP party, for Direito das Putas (Whore’s Rights). Within this universe I need to make sure that people understand that politics - political parties, the boss, the governor, the major, the city councilman - that they are there to get things done. For example, if I’m talking to the Secretary of Human Rights, I need to make sure that the Secretary of Human Rights understands that whores have the same rights as women farmers, as teachers, as lesbians, as Black women. I can’t just be an activist for whores. I need to be an activist for my community too, for people ().

Figure 2. Photograph of Maria de Jesus with members of the Coletivo Por Elas Empoderadas. From left to right: França Sousa, Fernanda Ribeiro, Paixão Gonçalves, Etiene Mendes and Jesus Costa. Credit: Jefferson Santiago.

If I’m going to demand rights though, it’s different. I’m going to demand rights for my population that I know, the population that I am with everyday. In these cases, then Jesus - the whore and prostitute - comes into play. I think that we always have two ways we could go, and I always knew very well which one to take. I know when it’s time to be a lady, when it’s time to tear things up, the time to say what we need.

I think that we, of the movement, shouldn’t be angry at anyone. We have to talk with everyone. Of course our political ideology is one thing and party politics are another. But our politics are to make things happen differently. The State, for example, was always a big partner of ours! A lot of people complain about this partnership in Maranhão, but for us it hasn’t been an issue. Maybe it is because we try and woo everyone. I tend to say this: the mayor isn’t my mayor, he’s the city’s mayor; if I have to dialogue with the mayor, I’ll go after him. I’ll campaign the entire night to talk to him at 7am. I go because he’s the mayor, because he has to do things, but maybe he doesn’t know what my neighbourhood needs. So I have to go after him.

We are enemy number 1 of Bolsonaro,Footnote6 but if I need to say something to Bolsonaro, I’ll go. I hate his politics, I hate him, but if I have to talk to him, we’ll talk to him. My ideology is my ideology, his is his. But if he, with the disgraceful ideology that he has, takes care of my needs, great! It’s not that we need to associate ourselves with bad things. We don’t have to love bad things, but we can’t stop doing what needs to be done.

FR: And what about this current political context, what are the main challenges right now in this far-right government?

MJ: Nothing was ever easy. This is something that we need to get out of our heads. Because sometimes people would say, ‘And what now? and now? And now?’. Now we are going to fight like we’ve always fought. Because nothing was ever for free. Nothing was ever easy. Everything was always with a lot of struggle, right? In all of the previous governments we were always left waiting, we always had to seduce the politicians, the government and wave our flag, right?

The difference is that now, the people that are there [in government] don’t understand that, in fact, they don’t understand a damn thing (laughs). So it’s more difficult because they aren’t going to help anything. First, because they don’t know our politics. They are people who are totally uninformed. The government is terrible and the people who are in it are terrible too. But even with all of these difficulties, in this crazy scenario, we are still able to do our part. And now, we also have the pandemic- so we don’t know if what is making things difficult is the government or the pandemic. They’re two things against us, and not just us, but also against Brazil.

So I think that what is left for us to do is what we do best. It is to talk, dialogue, discuss, not lower our heads to anyone, and continue saying to people: ‘look, it’s necessary … it’s necessary that we come together as the Brazilian whore’s movement’.

I believe in good things, I don’t believe in bad things. I think that good things will come, for example, our national meeting in 2022. We need to understand that we aren’t just women from the cabarets, we are also daughters of God, that have to learn to live in harmony. This is a moment of transformation. Not that what happened before wasn’t important. We are going to do things based on the old, but not do the same things that we did before. We are preparing for other things. We are preparing for new winds. We need to be prepared.

Conclusion

The history of the sex worker movement in Brazil is the life history of women that have been leaders and references in their regions for the political organisation of prostitutes since the 1990s. Women like Jesus who has fought for sex worker and women’s rights ever since she first felt the violence and stigma of ‘being a puta’. And women like Gabriela Leite in Rio de Janeiro (in memoriam), Lourdes Barreto in Pará, Fátima Medeiros in Bahia, Vania Rezende in Pernambuco, Celia Gomes in Piauí, Carmen Lúcia in Rio Grande do Sul, and so many others.Footnote7

As a researcher of the sex worker movement since 2011 (Ribeiro, Citation2013, Citation2015), I’ve perceived how changes in the movement happen first in sex workers’ lives; there is no way to separate the collective – as a fight – from the Individual, protagonist of the fight. In this way, there are deep connections between their subjectivities and force as women and sex workers that influence the way in which they do politics (Olivar, Citation2013). Brazilian sex worker activists have a unique and effective way of organising that reflects these complex connections and contradictions that they navigate in their daily lives and fights, a form of activism that Laura Murray has called puta politics (Murray, Citation2015). This way of ‘doing politics’ was modified in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic in Brazil and the world, and new forms of doing politics also emerged.

As Jesus shows us, throughout the interview, there were always difficulties in fighting for sex worker rights, and now no different the voracious advancement of neoliberalism and waves of conservative politics all of the world has obligated movements, and not just those of sexual minorities, to reinvent themselves to continue (re) existing.

Jesus’ life and her perseverance in the face of great obstacles combined with her ability to mobilise political leaders, even from opposing parties and interests, is an example for those of us in the academy of the need to assume political positions and act in true partnership and solidarity with the groups that form the focus of our research and collaborations. This alliance is fundamental to ensure that lives are livable (Butler, Citation2018) in the current social, economic, political, and environmental chaos and necropolitics imposed by the modern State (Mbembe, Citation2016).

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Laura Murray for translating the interview and for the support given throughout the process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 To learn more about APROSMA, I suggest reading the book Sexualidade e cor: dinâmicas da prostituição feminina nas áreas centrais da cidade de São Luís, Maranhão, by author Tatiana Reis Silva (Citation2015).

2 The Brazilian Network of Prostitutes was founded by Gabriela Leite and Lourdes Barreto in 1987 in Rio de Janeiro. The Charter of the Brazilian Network of Prostitutes' Principles is available on the website https://observatoriodaprostituicao.wordpress.com/carta-de-principios-da-rbp/.

3 The Coletivo Por Elas Empoderadas was launched in 2019 at a national sex worker meeting held in São Luis/MA. The collective is formed by members of the former APROSMA (Association of Prostitutes of Maranhão) and others who fight for the rights of women and sex workers in the city of São Luís. The collective works for the prevention of STIs, HIV/AIDS, and for women's political and economic empowerment.

4 Created in 1980, Inter Aide is a humanitarian organisation specialised in the implementation of development programmes that aim to promote access for the most vulnerable to development. For more information, see: https://www.developmentaid.org/#!/organizations/view/47742/inter-aide.

5 The word used in Portuguese is ‘garota de programa’. ‘Programas’ is the term used in Portuguese to describe sex workers’ exchanges with clients. ‘Garota’ means girl, so literally ‘garota de programa’ is a ‘date girl’. It is a more neutral term than ‘whore’ or prostitute, yet also different than using ‘sex worker’, as this has become a more politicised term. Due to this, we’ve chosen to translate it to ‘working girl’ to convey the difference from more politicized or stigmatized words such as whore and sex worker. Jesus here is referring to how sex workers use a variety of terms in Brazil, and that not all feel comfortable embracing the word ‘puta’ (whore) as prostitute leaders like Jesus, Gabriela Leite and Lourdes Barreto did and do in their activism.

6 Bolsonaro is the current president of Brazil (2019–2022). He was elected and has led on a conservative, far-right platform committed to taking away rights of the LGBT population, women and social minorities.

7 To learn more about the history of the sex worker movement in Brazil, I suggest the texts in the references by Calabria (Citation2020), Leite (Citation2008), Murray (Citation2015), Jose Miguel Olivar (Citation2013), Prada (Citation2018), Simões (Citation2010), and Simões, Silva, and Moraes (Citation2014).

References

- Butler, J. (2018). Corpos em aliança e a política das ruas. Civilização Brasileira.

- Calabria, A. d. M. (2020). Eu Sou Puta: Lourdes Barreto, História de Vida e Movimento de Prostitutas No Brasil [Dissertação (Mestrado em História)]. Instituto de Ciências Humanas e Filosofia, Universidade Federal Fluminense.

- Collins, P. H., & Bilge, S. (2020). Interseccionalidade. Boitempo.

- Leite, G. (2008). Filha, mãe, avó e puta: a história de uma mulher que decidiu ser prostituta. Objetiva.

- Mbembe, A. (2016). Necropolítica: biopoder, soberania, estado de exceção, política de morte. Arte & Ensaios – Revista do PPGAV/EBA/UFRJ, 32(2), 122–151.

- Murray, L. (2015). Not fooling around: The politics of sex worker activism in Brazil [PhD dissertation in Sociomedical sciences]. Columbia University.

- Olivar, J. M. (2013). Devir Puta: políticas de prostituição de rua na experiência de quatro mulheres militantes. Ed. UERJ.

- Prada, M. (2018). Putafeminista. Veneta.

- Ribeiro, F. M. V. (2015). É possível consentir no mercado do sexo? O difícil diálogo entre feministas e trabalhadoras do sexo Revista de Estudos e Investigações Antropológicas, 2(2), 17–29.

- Ribeiro, F. M. V. (2013). Táticas do sexo, estratégias de vida e subjetividades: mulheres e agência no mercado do sexo e no circuito do turismo internacional em Fortaleza/Ceará [Dissertação (Mestrado em Sociologia)]. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Sociologia, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco.

- Silva, T. R. R. (2015). Sexualidade e cor: mulheres negras e prostituição feminina nas áreas centrais da cidade de São Luís. Eduema.

- Simões, S. S. (2010). Identidade e política: a prostituição e o reconhecimento de um métier no Brasil. R@u: Revista de Antropologia Social dos Alunos do PPGAS-UFSCAR, 2(1), 24–46. https://doi.org/10.52426/rau.v2i1.20

- Simôes, S. S., Silva, H. R., & Moraes, A. F. (Org.) (2014). Prostituição e outras formas de amar. Editora da UFF.