ABSTRACT

This article explores the meaning, manifestations, and ramifications of medical neutrality in conflict zones. We analyse how Israeli healthcare institutions and leaders responded to the escalation of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in May 2021 and how they represented the role of the healthcare system in society and during conflict. Based on content analysis of documents, we found that healthcare institutions and leaders called for cessation of violence between Jewish and Palestinian citizens of Israel, describing the Israeli healthcare system as a neutral space of coexistence. However, they largely overlooked the military campaign that was simultaneously taking place between Israel and Gaza, which was considered a controversial and ‘political’ issue. This depoliticised standpoint and boundary work enabled a limited acknowledgement of violence, while disregarding the larger causes of conflict. We suggest that a structurally competent medicine must explicitly recognise political conflict as a determinant of health. Healthcare professionals should be trained in structural competency to challenge the depoliticising effects of medical neutrality, with the aim of enhancing peace, health equity, and social justice. Concomitantly, the conceptual framework of structural competency should be broadened to include conflict-related issues and address the needs of the victims of severe structural violence in conflict areas.

Introduction

In recent years, there has been a growing recognition of the structural determinants of health (e.g. Harvey et al., Citation2022; Hiam et al., Citation2019; Unger et al., Citation2022a, Citation2022b). This concept relates to a variety of upstream, macro-level forces that impact health and healthcare, such as public policies and legislation, social, economic, and legal systems, and political decisions and processes. The educational framework of structural competency has been developed to allow healthcare personnel to identify, acknowledge, and address structural determinants in their professional practice.

However, violent political conflict is largely overlooked in the structural competency training and research, and, more broadly, in most of the scholarship on global public health, bioethics, and health promotion. Abuelaish et al. (Citation2020) assert that although conflict always affects health, public health and health promotion experts have often failed to recognise the interrelations between health and peace. In the context of mental health, Kienzler (Citation2019) argues that in conflict-affected settings, upstream social and political determinants are rarely addressed. Specifically, Lederman (Citation2021) notes that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is a neglected bioethics problem. This misrecognition likely stems from the dominance of the ethos of medical neutrality, the normative position that armed conflict does not affect medical ethics,Footnote1 and the focus on the US context in the existing literature on structural competency.

Many clinicians dismiss structural factors as peripheral due to medicine’s traditional focus on biologic mechanisms, individual behaviours, and medical technologies (Carrasco et al., Citation2019; Holmes et al., Citation2020). Consequently, these clinicians often miss opportunities to improve health outcomes and may even ‘fail at medicine's core responsibilities to diagnose and treat illness and to do no harm’ (Holmes et al., Citation2020, p. 1083). We propose that this is equally true for disregarding structural political violence and armed conflict as crucial determinants of health.

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is a significant structural determinant of health that creates deep health inequalities between Israelis and Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. The conflict and the chronic occupation of the Palestinian territories limit Palestinians’ access to healthcare as well as the availability and quality of food, water, electricity, housing, social services, education, and employment. In May 2021, there was a 12-day military campaign between Israel and the Palestinians in the Gaza Strip, as well as intergroup violence within Israel between Jewish Israelis and Palestinian Israelis. This article examines how Israeli healthcare institutions and leaders of health organisations responded to the eruption of violence in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and how they represented the role of the healthcare system in society and during conflict.

The findings illuminate that while healthcare leaders became engaged in the public discourse on the political violence inside Israel, between Jewish Israelis and Palestinian Israelis, they refrained from referring to the Israel-Gaza battles. We examine the meaning, manifestations, and repercussions of neglecting conflict-related structural determinants of health. We call for a broader framing of structural competency that would include conflicts, hostilities, political violence, and occupation as globally and locally recognised structural determinants of health. This new framing would encourage healthcare professionals in conflict settings to become critical intellectuals in the sense that Edward Said proposed: individuals who belong on the same side with the vulnerable and unrepresented people, who cannot be easily co-opted by governments, as they are ‘unwilling to accept easy formulas, or ready-made clichés, or the smooth, ever-so-accommodating confirmations of what the powerful or conventional have to say, and what they do’ (Said, Citation1994, p. 23).

Medical neutrality

According to the normative arrangement of medical neutrality, healthcare practitioners and their patients are positioned outside of the field of politics (Redfield, Citation2013, Citation2016). Medical neutrality differentiates a zone of clinical practice in which patients are treated impartially, and medical personnel are shielded from the demands of politics and conflict (Redfield, Citation2016). The origins of medical neutrality lie in humanitarian political and legal regimes defining the role of medical personnel and the status of the wounded in contexts of war (Redfield, Citation2011). Thus, according to the first and fourth Geneva Conventions, in armed conflict, medical personnel, the wounded and sick, and healthcare facilities must be protected (International Committee of the Red Cross, Citation1949a, Citation1949b).

Redfield (Citation2016) characterises medical neutrality as a principle that, on the one hand, protects medical staff and patients from state power and violence and even offers possibilities for contesting them, and, on the other hand, often reifies hegemonic forms of power. On the one hand, medical neutrality aims to make the hospital and the clinic safe havens, professional spaces where all patients get equal treatment regardless of their ethnicity, race, class, gender, religion, or other axes of difference and discrimination. In some instances, medical neutrality may even be wielded against state power, as it offers a basis for authoritative claims about the preservation of life in the face of military violence (Hamdy & Bayoumi, Citation2016) or as a form of witnessing (témoignage) that casts light on humanitarian violations (Redfield, Citation2013).

On the other hand, the ethos of medical neutrality can also lead to overlooking or denying the macro-level political, policy, social, economic, and legal factors that impact patients’ health. This ethos often entails depoliticisation in which ‘issues are driven outside the political realm and actors minimize, avoid or conceal the political dimension of their action’ (Louis & Maertens, Citation2021, pp. 5–6). The ethos of medical neutrality can benefit those in power by perpetuating the existing repressive systems and precluding the ability to criticise them (Barnes & Parkhurst, Citation2014; Orr & Unger, Citation2020a).

As a result of this duality embedded in the idea of medical neutrality, medicine serves as ‘both a site to contest, suppress, uphold or reproduce political violence presumed to occur outside its boundaries’ (Benton & Atshan, Citation2016, p. 153). In this way, medical neutrality ironically operates as a thoroughly political tool or stance, and medical humanitarianism can become a terrain of political struggle (Aciksoz, Citation2016; Benton & Atshan, Citation2016). In an increasing number of cases of intrastate conflicts, medical professionals and institutions were targeted by state violence, and in turn, healthcare professionals resisted state oppression, politically aligned with the dissidents in the conflict, and actively aided in protest efforts using their professional practice (Adams, Citation1998; Roborgh, Citation2018; Salunke, Citation2020).

In Israel, the supposedly depoliticised and neutral approach prevails. Particularly, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is usually not perceived as a legitimate topic for in-depth discussion or action within healthcare (Orr & Unger, Citation2020a). The ethos of neutrality has been credited with enabling healthcare to become one of the most diversely integrated sectors (Keshet & Popper-Giveon, Citation2017) and even with constructing a legitimised standpoint from which Palestinian healthcare professionals can produce testimony of state violence (Shalev, Citation2016). However, Shalev explains that this neutrality, which he sees as ‘a shared fiction’, is applied selectively, imposing limitations on some while enabling others (Shalev, Citation2018, p. 177).

While Palestinian Israeli professionals working in the Israeli healthcare system recognise that the ethos of neutrality may support their inclusion within this system, neutrality also works to mask experiences of discrimination and the unequal effects of political conflict (Keshet & Popper-Giveon, Citation2017). Claims to neutrality in the medical sphere also operate as a powerful justification for ignoring unequal conditions that shape health for Palestinian citizens of Israel (Razon, Citation2016).

Furthermore, critical scholars and organisations contend that the ethos of neutrality serves not only to overlook systemic violations of human rights, including the right to health, but also to mask or justify support for and complicity in these violations and alignment with oppressive state policies. For example, Tanous and Majadli (Citation2022) explain that the Israel Medical Association supported the establishment of the Adelson School of Medicine at Ariel University, located in an Israeli settlement in the West Bank. In their response to Physicians for Human Rights Israel, the Israel Medical Association used the principle of neutrality and the Association’s apolitical stance to justify their position regarding a politically contested issue, arguing that it is ‘wrong to enter political disputes in matters of such importance … ’ Tanous and Majadli show how this response ‘applies a selective understanding of what constitutes ‘political’’.

Another example is torture. Summerfield (Citation2022) points to medical complicity with torture in Israel, which has been the subject of international appeals signed by hundreds of physicians. Physicians for Human Rights Israel (Citation2022) argues that the Israel Medical Association systematically ignores physician participation in torture, refraining from thoroughly examining interrogee complaints. The Israel Medical Association rejected these claims, stating that torture is abhorrent, the Association in no way endorses it, and these accusations are unfounded and political (Blachar, Citation2003). In an article entitled ‘British medical journals play politics’, senior officials in the Israel Medical Association assert that ‘leading British medical journals […] have delighted in publishing political rhetoric disguised as medical articles. […] Through the years, the Israel Medical Association […] has tried to remain politically neutral … ’ (Shoenfeld et al., Citation2009, pp. 325–326).

Medical neutrality is compatible with the broader practice of sanitising institutional spaces of political discussions related to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict (Golan et al., Citation2017; Golan-Agnon, Citation2020; Orr, Citation2016; Shenhav, Citation2008; Zielinska, Citation2018). The findings of Golan and Shalhoub-Kevorkian (Citation2019) indicate three main reasons for this depoliticisation in the context of community engagement in Israeli higher education, which we think help explain the depoliticised engagement of healthcare practitioners. The first reason is a prevailing sense of hopelessness, weariness, apathy, and lack of faith in a potential resolution to the conflict. Second, actors attempt to build stable and positive social connections and avoid discussing the conflict for fear of causing tension in the Israeli-Palestinian group and jeopardising the safe space that had been created in the group. The third reason is related to limited freedom of expression and self-censorship. Many Palestinians are afraid to express political views that are considered illegitimate in the hegemonic Israeli discourse.

However, despite the dominance of the depoliticised approach, there are Israeli healthcare practitioners who promote counter-hegemonic discourse and protest state violence. A prominent example is the activists of Physicians for Human Rights Israel, one of the first Israeli human rights organisations that abandoned the declared ‘apolitical and neutral’ stance (Golan & Orr, Citation2012) by resisting Israel's continued occupation of the Palestinian territories and conceptualising it in terms of apartheid and colonialism (Physicians for Human Rights Israel, Citation2021a).

Despite recent developments in this field of research, scholars point to considerable knowledge gaps. Roborgh (Citation2018) indicates that there are a limited number of contributions on local healthcare workers’ activities during times of conflict. Salunke (Citation2020) notes that more study can be used to broaden and expand this subfield. We aim to contribute to expanding this subfield by examining how in the Israeli-Palestinian context, prominent healthcare organisations and professionals upheld, negotiated, or challenged the notion of medical neutrality, and how this process should be considered in further developing the framework of structural competency.

Structural competency

The COVID-19 pandemic has illuminated global, national, and local issues of health disparities, biases, institutional discrimination, structural racism, and the crucial role of the structural determinants of health (Chen & Krieger, Citation2021; Metzl et al., Citation2020). Structural competency is a framework that has been developed in the past decade to help healthcare personnel identify and address these issues (Metzl & Hansen, Citation2014). Neff et al. (Citation2020) define structural competency as ‘the capacity for health professionals to recognize and respond to health and illness as the downstream effects of broad social, political, and economic structures’ (p. 2). Structural competency allows healthcare professionals to discern and acknowledge how social-political structures, such as public policies, economic and legal systems, social hierarchies, and healthcare delivery systems, shape diseases and their unequal distribution (Harvey et al., Citation2022; Metzl & Hansen, Citation2014). Structural competency training encourages healthcare professionals to consider these multiple, entangled, extra-clinical structural forces and their influence on health outcomes when treating their patients (Metzl & Roberts, Citation2014). This conceptual framework also increases healthcare providers’ understanding of how structurally-generated health disparities are naturalised, i.e. viewed as natural and deserved rather than unjust and imposed (Harvey et al., Citation2022; Neff et al., Citation2020), leading to overlooking or denying the socio-political origins of health inequalities (Farmer, Citation2001; Holmes, Citation2013).

Structural competency has been proposed as a way to broaden the perspective of the earlier, more established concepts of the social determinants of health and cultural competency (Hansen et al., Citation2018; Metzl & Hansen, Citation2014). The social determinants of health, like poverty, seemed insufficient, raising the question about their underlying causes, e.g. what are the structural determinants that produce and reproduce poverty? (Neff et al., Citation2020). Cultural competency was criticised as perpetuating and reifying ethnic and racial biases and stereotypes (Gregg & Saha, Citation2006).

Structural competency motivates medical staff to speak up more vocally about structural forces that affect patients’ health, become more engaged in policy leadership, and create collaboration and alliances between different professionals (physicians, nurses, social workers, lawyers, etc.) who serve the same vulnerable patients – to effectively address the structural determinants that impact these patients (Bourgois et al., Citation2017; Downey et al., Citation2019; Metzl & Roberts, Citation2014). Moreover, structural competency encourages staff members to closely collaborate with disenfranchised patients and marginalised communities. It fosters the development of critical consciousness, which challenges deeply held social-political assumptions, in both the medical staff and the patients with whom they collaborate (Carrasco et al., Citation2019).

Structural competency can contribute to addressing the lasting lesson of COVID-19 that ‘health and illness are political’, and therefore, medicine needs ‘to have an explicit political voice’ (Metzl et al., Citation2020, p. 232). This is by no means a completely new perspective. Already in 1848, Virchow famously stated that ‘medicine is a social science, and politics nothing but medicine at a larger scale’ (Virchow, Citation1848; see Mackenbach, Citation2009). However, although many healthcare providers deal with the consequences of political conflict in clinical settings (Galea, Citation2022), understanding and addressing conflict is generally considered outside the purview of healthcare expertise. Hence, the political conflict is a largely ignored structural determinant of health. While structural competency has been a useful framework for expanding healthcare expertise to include upstream determinants, it was developed largely in the US and has overlooked violent political conflict as a structural determinant. Melino et al. (Citation2022) undertake a concept analysis of structural competency using a systematic literature review on structural competency. They indicate that apart from two articles written by Israeli researchers (Orr & Unger, Citation2020a, Citation2020b, see below), the literature retrieved for their review was entirely written by American scholars. They also note that the concept of structural competency arises out of the American social and health systems context. The literature focuses predominantly on US concerns, such as substantial economic inequalities, systemic racism, and immigration, and does not refer to political conflicts. Another reason for excluding recognition of political conflicts is the dominant ethos of medical neutrality and the depoliticised approach. We propose that broadening the concept of structural competency to include structural determinants that are rooted in political conflicts can challenge the naturalisation of these determinants which reproduces health inequity in conflict settings.

The TOLERance Model

The TOLERance Model (Theory, Observations, Learning from patients, Engagement, Research) was developed for training Israeli nurses in structural competency in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict (Orr & Unger, Citation2020b). This model, which is applicable to other settings, includes five components:

Theory. Participants learn key concepts in structural competency, such as structural violence, naturalising inequality, and structural racism, based on the training curriculum of the Structural Competency Working Group in the San Francisco Bay Area (Neff et al., Citation2020), translated and adapted to the local context. Participants also learn empirical studies on the social, structural, and conflict-related determinants of health and analyse clinical case studies affected by the conflict.

Observations. The training includes field trips that explore how embedding structural competency in healthcare practice can promote health equity. For example, Israeli healthcare providers visit Palestinian hospitals in East Jerusalem and discuss with the Palestinian staff structural, conflict-related problems and how to address them.

Learning from patients. Marginalised patients partake in shaping the training curriculum and training the medical teams, drawing on these patients’ experiences in their encounter with the healthcare system, including experiences stemming from structural violence.

Engagement. Participants are encouraged to partake in community engagement activities that include social and political advocacy and varied structural interventions that participants initiate, plan, and run for over a year. Participants are awarded scholarships for implementing their projects in practice.

Research. The program involves healthcare providers and students in empirical research where they can encounter the structural determinants of health first-hand. This includes research seminars for small groups of up to ten learners. Throughout a year, each group plans and performs all the steps of the research project, under the guidance of faculty researchers.

This training has fostered numerous changes on the ground. One example is an inter-professional intervention led by a nurse practitioner in palliative care to provide home palliative care for Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem living beyond the Israeli West Bank barrier (Separation barrier). This nurse practitioner said that the training increased her knowledge and awareness of structural issues, her understanding of her Palestinian patients, and her ability to offer solutions that address the structural problems (Aharon et al., Citation2021).

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict as a structural determinant of health

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict directly affects the lives and health of both Palestinians and Israelis. According to B'Tselem's data, from the beginning of the Al-Aqsa Intifada (Palestinian uprising) in September 2000 until February 28, 2022, 10,259 Palestinians were killed by Israeli security forces and civilians. During the same period, 1,279 Israelis (of whom 837 civilians and 442 security forces) were killed by Palestinians. Of the fatalities, 2,185 Palestinian minors and 642 Palestinian women were killed by Israeli security forces; 139 Israeli minors and 254 Israeli women were killed by Palestinians (B'Tselem – The Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories, Citation2022). According to the UN data, in the past decade,Footnote2 122,833 Palestinians were physically injured as a result of the conflict.Footnote3 In this decade,Footnote4 4,600 Israelis, of whom 3,845 civilians, were physically injured due to the conflictFootnote5 (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Citation2022).

The people of the Gaza Strip suffer from a continuous land, air, and sea blockade imposed by Israel and Egypt since 2007, when Hamas took control in Gaza. The Israeli government, as well as many Israeli academics, argue that this blockade is necessary to prevent transforming imports into weapons, thereby protecting Israelis from Hamas’s rocket attacks and terrorism (Manor et al., Citation2020). Human rights organisations maintain that Israel’s legitimate security concerns cannot justify the massive violation of rights that the blockade inflicts on the people of the Gaza Strip (Human Rights Watch, Citation2021). They also argue that Israeli authorities abuse their control over the movement of patients to exert political pressure on Hamas; hence, the violations of rights are carried out not just for security concerns.

Due to the blockade, many medical treatments are unavailable in the Gaza Strip. Each year more than 9,000 patients require Israeli exit permits to leave the Gaza Strip for medical treatment, and many patients are left without access to adequate healthcare (Moss & Majadle, Citation2020). For example, in 2018, 39% of patient permit applications were unsuccessful. Over a quarter (28%) of patient applications were for cancer care (World Health Organization, Citation2019a). Furthermore, the closure results in water and electricity crises, high unemployment rate, deep poverty, shortage of medication, medical equipment, and other essential goods – all crucially affect the public health (Moss & Majadle, Citation2020).

There are significant health inequalities between Palestinians in the West Bank and Israelis (Lederman et al., Citation2018). For example, life expectancy at birth in Israel is approximately nine years higher than it is for Palestinians (World Health Organization, Citation2019b). There are disparities in infant mortality rate, maternal mortality rate, and morbidity rate (Physicians for Human Rights Israel, Citation2021a). These inequalities stem, to a large extent, from structural and conflict-related factors (Collier & Kienzler, Citation2018; Fahoum & Abuelaish, Citation2019; Giacaman et al., Citation2009, Citation2011). The ongoing military occupation produces chronic de-development and insecurity, erodes social cohesion, exposes individuals (including children) to everyday violence, and detrimentally affects Palestinians’ underlying conditions of life needed for enjoyment of good health, such as food, water, and housing (Batniji et al., Citation2009; Horton, Citation2009; World Health Organization, Citation2019a).

Research shows how the Israeli-Palestinian conflict significantly limits Palestinians’ access to care, such as maternal and child care (Leone et al., Citation2019). For decades, Israeli governments have imposed separation between the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip, as well as between Palestinian communities in the West Bank, restricting the freedom of movement of patients, healthcare providers, and medical equipment, thus creating barriers to health access and impeding the proper functioning of the Palestinian healthcare system (Moss & Majadle, Citation2020; World Health Organization, Citation2019a). The extensive system of military checkpoints also creates unpredictable delays, including for ambulances (World Health Organization, Citation2019a). For decades, the West Bank population used the advanced healthcare services of the Palestinian hospitals in East Jerusalem. The Israeli West Bank barrier (Separation barrier) that was constructed following the Al-Aqsa Intifada, together with the Israeli permit regime, disconnected the West Bank population – both patients and healthcare professionals – from the healthcare system in East Jerusalem (Physicians for Human Rights Israel, Citation2014). The adverse effects of the political and social determinants have been highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic (Hammoudeh et al., Citation2020; Lederman et al., Citation2022; Mahamid et al., Citation2022).

The conflict’s effects on mental health

The conflict affects the mental health of both Palestinians and Israelis. Palestinians’ mental health is negatively affected by the exposure to the ongoing traumatic stress of the structural violence (Shaheen et al., Citation2020; World Health Organization, Citation2019b). For example, forcible invasions by Israeli soldiers into homes of families have grievous mental health repercussions, including on children (Moss et al., Citation2021). Moreover, political and social factors directly and indirectly impact behavioural determinants of health, including smoking, substance abuse, increasingly sedentary lifestyle, unhealthy diet, and involvement in peer violence (Abu Hamad et al., Citation2021; Collier & Kienzler, Citation2018). Mental health providers in the Gaza Strip argued that the main determinants of psychological burden among their patients are the socio-economic, educational, and health-related consequences of the blockade of the Gaza Strip (Diab et al., Citation2022).

The political conflict also harms the physical and mental health of many Israeli citizens, such as victims of the numerous deadly terror attacks that have taken place in Israel in the past decades (Ad-El et al., Citation2006). Slone and Shoshani (Citation2022) found that a large population of adolescents in Israel suffers from negative emotional effects and damage to subjective well-being due to exposure to the protracted hostilities, threat, and armed conflict. There are positive relations between severity of exposure to political violence and mental health symptoms, emotional and behavioural difficulties, and lower subjective well-being. Pat-Horenczyk (Citation2005) examined adolescents in Jerusalem and nearby settlements who were subjected to intensive terrorist attacks in the context of the Al-Aqsa Intifada. Two-thirds of the participants reported high levels of fear, helplessness, and horror, and 5.1% were diagnosed with PTSD. Participants also experienced functional impairment, somatic symptoms, and depression.

The political violence of May 2021

From May 10th to May 21st, 2021, there was a military campaign between Israel and the Palestinians in the Gaza Strip, which was the worst escalation in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict since 2014. According to UN data, during this escalation, 261 Palestinians were killed, including 67 children and 41 women, and over 2,200 Palestinians were injured, including 685 children and 480 women. In Israel, 13 people, including two children, were killed, and 710 people were injuredFootnote6 (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Citation2021). In addition, the conflict seriously damaged various infrastructures in the Gaza Strip, including hospitals and medical centers, buildings, water and sanitation facilities, and transport, communications, and energy networks (World Bank Group et al., Citation2021).

This violent conflict, which Israel called ‘Operation Guardian of the Walls’, was accompanied by an acute deterioration of relations between Jewish and Palestinian citizens of Israel. Protests by Palestinians which had started in East Jerusalem spread to Palestinian communities in Israel and to ethnically mixed cities in Israel (Eghbariah, Citation2022; Matza, Citation2021; Zeedan, Citation2021). This led to open altercations in the mixed cities and other localities, whereby both young Palestinians and Jews engaged in violent acts. These acts, which were the worst clashes between Jewish and Palestinian citizens of Israel in two decades, included deadly attacks as well as acts of arson and vandalism to religious sites, public and private property, and vehicles (Lavie et al., Citation2021). Most of the Jews involved in these clashes were members of the extreme right, while most of the Palestinians involved were young individuals on the margins of society with no political affiliation (Lavie et al., Citation2021). Israeli police arrested around 2,150 people, of whom more than 90 percent were Palestinians (Eghbariah, Citation2022). Human rights organisations argue that the purpose of these mass arrests was collective punishment and intimidation of Palestinian citizens of Israel, and that these arrests were employed based on racial profiling, using excessive force and violence (Adalah – The Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel, Citation2021).

During the escalation, demonstrations from both sides took place at the doorstep of Israeli hospitals (Danino, Citation2021). Further, thousands of Arab medical staff went on a one-hour strike, protesting that while they save lives, they fear for their own lives due to the political violence. For example, they felt unsecure on their way from home to their workplace, and some heard anti-Arab offensive remarks from patients (Abu Laban & Gawi, Citation2021). A few days later, Palestinian citizens of Israel held a general strike across Israel (Khoury, Citation2021). However, according to the Israeli Ministry of Health, over 90% of the Arab healthcare workers did not attend this strike (Bisharat, Citation2021). This figure may be explained by feelings of fear due to many incidents of threats and harassment on social media and due to the unequal power relations in the healthcare system. Many Palestinian healthcare workers refrained from openly expressing their views for fear of being labeled and targeted in their workplace, losing their jobs, or being denied future professional opportunities (Physicians for Human Rights Israel, Citation2021b; Shalev & Tanous, Citation2021).

Thus, the political conflict began to seep into the Israeli healthcare system, which could potentially have significant ramifications, given that a considerable portion of the employees in this system consists of Palestinian-Arab employees. In 2020, 16% of the physicians, 34% of the dentists, and 48% of the pharmacists aged 67 or younger (Ministry of Health, Citation2021) as well as 24% of the nurses (Yaron, Citation2020) in Israel were Arab (including Druze). In 2020, Arab (including Druze) professionals received 46% of the new licenses given to physicians, 50% of the new licenses given to nurses, 53% of the new licenses given to dentists, and 57% of the new licenses given to pharmacists in Israel (Ministry of Health, Citation2021). Therefore, a deterioration in the Jewish-Palestinian relations in the healthcare system, and a strike of the Palestinian employees, might adversely affect the work of healthcare institutions.

Method

This article is based on content analysis of documents published by Israeli healthcare institutions and leaders of health organisations in response to the hostilities of May 2021. We analysed public statements they made and other documents they published that directly addressed the escalation of political violence. These documents included articles in newspapers and websites, open letters, reports, interviews, recordings of speeches, and other texts. These documents were issued by various organisations and stakeholders, such as public (nongovernmental) hospitals, governmental hospitals and their directors, the Israel Medical Association, the Israeli Nurses Association, Ministry of Health officials, director of a health promotion organisation, a health rights organisation, and senior physicians in the healthcare system. We also examined related texts, such as newspaper articles reporting on the healthcare system during the escalation, which provided broader context. We reviewed 43 public documents and, of these, selected seven documents from the most prominent Israeli medical organisations and stakeholders that made statements regarding the conflict.

We analysed the documents to understand how they represented the ethos of medical neutrality. We propose that these documents represent the dominant perspective and normative position shared within healthcare institutions, and not only the perspectives of individual healthcare practitioners. Using content analysis (Stemler, Citation2001), we coded the documents for their propositions and assumptions about the conflict, the role of the healthcare system in the conflict, and other emergent themes related to political violence.

Results: The reaction of Israeli healthcare institutions and leaders

The exceptional political violence aroused many reactions among senior figures in Israel's healthcare system, which focused on the violence between Jews and Palestinians inside Israel (within the Green LineFootnote7), generally without mention of the hostilities that were simultaneously taking place between Israel and the Palestinians in the Gaza Strip, even though the latter had led to a greater number of casualties. For instance, the forum representing the seven public hospitals in Israel published a public statement that filled an entire page in the Haaretz daily newspaper on May 16, 2021 (Public Hospitals Forum, Citation2021).Footnote8 The goal, as indicated by its title, was ‘The de-escalation of the crisis and cessation of violence on the streets of Israel’. The statement called on citizens to ‘take a deep breath’, avoid violence, and engage in respectful dialogue. The statement described the healthcare system as directly suffering the brunt of the violence and its implications.

The description of the violent incidents in this statement likened them to natural disasters. One description used the metaphor of a tsunami: ‘Waves of violence are flooding our streets in a tsunami of hatred that threatens to annihilate us all’. In another example, a pandemic was the chosen metaphor: ‘Together we have overcome the COVID-19 pandemic and together we shall overcome the pandemic of hatred’.

The authors of this public statement represented the public healthcare services in Israel as an idealised space of coexistence, characterised by solidarity and universal principles: ‘We have the good fortune to be in charge of systems that both separately and cohesively provide the best possible proof that ‘coexistence’ is not merely a theoretical concept or a far-off dream that might never come true. For us, it is our daily reality’.

The healthcare system in Israel was described in this statement as a neutral territory that blurs the ethnic-national identities of the actors involved, emphasising that all the victims of violence, regardless of their ethnic or national identity, are brought to the same hospitals and are treated impartially by all members of the staff, who come from all kinds of backgrounds: ‘In the emergency room […], patients have no idea who will be treating them; who will attend to their wounds, who will offer a word of solace. At that moment, the distinction of ‘Arab’ or ‘Jew’ no longer exists’. Many of the texts published during this period negated the polarity between national identities, which beyond the hospital's perimeters is the source of the conflict, describing rather a universal human identity and Jewish-Arab partnership in the healthcare system (e.g. Danino, Citation2021).

The same message of neutrality and coexistence within the Green Line was conveyed in another public statement published in Hebrew and Arabic by the chair and directors of the Israel Medical Association, chair of the Israeli Nurses Association, directors of two governmental hospitals,Footnote9 chair of the Society for Health Promotion of the Arab Community, and a representative of Clalit, Israel’s largest public health maintenance organisation (Hagay et al., Citation2021). The title of this statement was ‘Medical personnel for reconciliation’, and this reconciliation seemed to refer solely to Jewish and Palestinian citizens of Israel. This statement, which used powerful, declarative, and even dramatic language, began as follows: ‘We, physicians, nurses, and directors, Jews and Muslims, Christians, Druze, and Circassians – refuse to be enemies’. The authors obligated themselves to protect one another ‘for we are brothers’, and to continue working shoulder to shoulder. They refused to see the coexistence that takes place in the clinics and hospitals as an extraordinary miracle. ‘We are not the exception, we are the normal’. They committed to spread this coexistence and tolerance to the entire Israeli society.

This statement, like the public hospitals’ statement, emphasised a central aspect of neutrality: the healthcare professionals’ commitment to treat any human being impartially, ‘regardless of their religion, race, or gender … ’ They also aimed to lead a societal change: ‘We will bring the values that guide us in the healthcare system to every street corner: the tolerance, sensitivity, inclusion, equality, compassion, and kindness’. They stressed their duty ‘to stand up against extremists’ and committed to protect ‘anyone who would be attacked due to their religion or point of view’ (see a similar message in Bisharat, Citation2021).

Other texts by senior officials in the healthcare system put forward similar values. For example, on May 13, Dr. Shoshy Goldberg, the National Head Nurse and Director of the Nursing Division at the Ministry of Health, sent a letter to Israeli nurses and nursing students. She called them to show responsibility, tolerance, and social solidarity, to unite and not take actions that may deepen the existing schism. On May 17, Prof. Ronni Gamzu, the CEO of the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, published an op-ed article emphasising the coexistence in Israeli hospitals and calling for putting an end to the violence, re-establishing security and stability, and addressing the socio-economic gaps in Israel (Gamzu, Citation2021).

The various texts did not refer to the rockets that were being launched from the Gaza Strip to Israel or to the air-raids conducted by the Israeli Air Force on the Gaza Strip, despite the many casualties caused by these events at the time. In this sense, the authors maintained their neutral and apolitical ethos, avoiding issues that are viewed as ‘political’ and controversial. Nevertheless, they took an active role in the public discourse on the relationship between Jewish and Palestinian citizens of Israel (within the Green Line). This is a clearly political issue, but it is often framed as an apolitical – or at least a legitimate and less divisive – issue. This framing springs from an imaginary of the civic sphere as an idealised liberal, public sphere where multicultural difference and tolerance may lead to a society of free and equal citizens. It is not considered ‘political’ or controversial to advocate for a multicultural Jewish-Arab coexistence within Israel, which is almost a consensual goal for Israeli liberals, but it is ‘political’ to comment on issues of war and peace, which are highly contested, controversial, and risky. However, the leading healthcare practitioners’ participation in the discourse on relationships within Israel could signal a change in the policy of neutrality practiced by the healthcare system, albeit without abandoning the overall apolitical ethos (‘the distinction of ‘Arab’ or ‘Jew’ no longer exists’, as the public hospitals claimed).

The National Head Nurse concluded her letter in calling nurses to continue being ‘an island of sanity and coexistence’. The conclusion to the public hospitals’ statement was as follows: ‘We will take any measures necessary to restore peace and coexistence’. However, this state of ‘peace and coexistence’ to which they wish to return is pertinent to the reality as most Jewish Israelis perceive from within the Green Line, but disregards the political reality in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, which even before the military escalation could not have been described as ‘coexistence’. Similarly, the statement of the Israel Medical Association's leaders et al. stressed the healthcare providers’ important role ‘in the current battle, at its center stands the entire Israeli society wounded and bleeding … ’, completely ignoring the people of the Gaza Strip and their suffering. The political violence that took place in May 2021 crossed the Green Line and infiltrated into Israeli society. The attitude expressed by the healthcare sector in their texts can be interpreted as an attempt to uphold the division between the two sides of the Green Line and to situate conflict outside the standard concerns of the healthcare sector.

The depiction of the Israeli healthcare system as ‘an island of coexistence’ also disregards the perspective of many Palestinian employees in this system (Shalev, Citation2018). Shalev and Tanous aptly show that this ‘coexistence’ relies on the Palestinian health professionals limiting their existence and hiding their opinions, national identity, experiences of racism, and fear. The ideal of coexistence has a disciplining power that is exercised unevenly on Jewish and Palestinian staff members. Any ‘political’ speech of Palestinian staff ‘is met with explicit threat of punishment. […] [W]hat seems like coexisting to the Jewish-Israeli side questions the very existence of the Palestinians’ (Shalev & Tanous, Citation2021). By contrast, the hegemonic Jewish-Israeli discourse and its numerous manifestations in the healthcare system is considered apolitical and legitimate.

The reaction of Physicians for Human Rights Israel to the hostilities was the exception that proves the rule. This organisation used the principle of medical neutrality in the sense of the obligation not to harm healthcare personnel and their patients, as well as healthcare facilities, during armed conflict, in accordance with the first and fourth Geneva Conventions (International Committee of the Red Cross, Citation1949a, Citation1949b). In September 2021, Physicians for Human Rights Israel protested the violation of this principle by Israel, listing 23 hospitals, medical centers, clinics, and other health infrastructures that were damaged during the hostilities in May. In some of these healthcare facilities, medical staff and patients were hit, including injured civilians.Footnote10 The organisation stressed that harming medical facilities and personnel allegedly constitutes a violation of international humanitarian law and may amount to a war crime (Physicians for Human Rights Israel, Citation2021c). This aspect of medical neutrality has not been mentioned by the Israeli mainstream healthcare institutions and leaders in their response to the hostilities, who interpreted medical neutrality as a depoliticised approach.

Discussion and conclusion

Studies of medical neutrality have deconstructed claims to a position ‘outside’ of politics. Redfield (Citation2016) portrays medical neutrality as ‘an antipolitics with political possibilities’ (p. 264). While medical neutrality can ensure non-discriminatory care, protect medical staff from political demands, and even offer possibilities for contesting power and structural violence, it can also naturalise repressive systems, mask the root causes of health inequities, and preclude analysis of structural determinants of health (Orr & Unger, Citation2020a).

Both the positive and negative ramifications of medical neutrality are intensified in conflict zones, where healthcare professionals often adopt a purportedly apolitical position, and, according to international law, must not be targeted during hostilities. The ethos of medical neutrality and the apolitical stance of medical institutions divert attention away from political conflicts and their effects on health and healthcare. Oftentimes, the ostensibly apolitical approach also masks de facto complicity of the healthcare system with state and military policies entailing structural violence and violation of human rights, including the right to life and to health.

In May 2021, Israeli healthcare institutions and leaders called for cessation of violence occurring within the Green Line and re-establishing coexistence, describing the Israeli healthcare system as a neutral space of coexistence, characterised by solidarity and universal principles. This vocal public engagement may mark a shift in the paradigm of the healthcare system, that had traditionally been less involved in societal issues. However, the healthcare institutions and leading professionals largely disregarded the military campaign that was simultaneously taking place between Israel and the Palestinians in the Gaza Strip. While calling for an end to violence, the public engagement of healthcare institutions and personnel appealed to precepts of medical neutrality and avoided issues that are viewed as ‘political’ and controversial. This standpoint enabled a limited acknowledgement of violence, while disregarding the larger causes of conflict.

This discourse can be interpreted as boundary work (Keshet, Citation2020) in which the leading healthcare professionals reaffirmed the distinction between the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians living beyond the Green Line, on the one hand, and the relationship between Jewish and Palestinian citizens of Israel within the Green Line, on the other hand. This distinction is a key element in Israel's strategy of defining and separating between different groups of Palestinians in Israel/Palestine, and it was adopted and upheld by Israeli healthcare institutions and leading professionals. The findings suggest that medical neutrality and the normative exclusion of politics are vital but under-appreciated aspects of how political conflict operates as a structural determinant of health.

The prevailing discourse and normative position among Israeli healthcare institutions and leaders differ from those characterising international organisations such as the World Health Organization (Citation2019a, Citation2019b). The latter tend to explain the health disparities and health challenges among Palestinians in political and non-neutral terms, highlighting structural, conflict-related determinants of health. Similarly, Palestinian clinicians are cognizant of the effects of political structures on their patients’ health (Collier & Kienzler, Citation2018; Diab et al., Citation2022). By contrast, Israeli healthcare institutions and leaders usually avoid this political perspective and adopt a declared ‘neutral’ perspective.

Moreover, the Israeli healthcare institutions and leaders presented an ideal of coexistence in the Israeli healthcare system, while at the very same time, Palestinian medical staff in this system who criticised or protested the military assault on Gaza were coerced into silence and even intimidated in the public sphere and social media. The healthcare institutions’ inadequate response to this worrying phenomenon is reflective of an apolitical discourse of coexistence which re-entrenches hegemonic power and aligns with structural violence against Palestinian citizens of Israel. However, it should be noted that the problem is not with having an ideology of coexistence, but rather with the way in which this ideology is deployed, a way that upholds the status quo and prevents dissent. Hence, we do not support abandoning the aspiration for coexistence in the healthcare system, but rather transforming the meaning (or interpretation) of this concept, especially what it implies for Palestinian medical staff in Israeli healthcare institutions, and politicising this concept.

Structural competency in contexts of conflict

We suggest that a locally tailored structural competency training can promote a more adequate social-political engagement of healthcare professionals. Structurally competent medicine must explicitly recognise political conflict as a determinant of health and the inherently political role of the healthcare sector in society. Healthcare professionals should be trained in structural competency to challenge the depoliticising effects of medical neutrality and the neglect of conflict as a determinant of health, with the aim of enhancing peace, health equity, social justice, and solidarity. This training will potentially expose healthcare providers to alternative conceptions of medical neutrality that do not entail problematic ‘states of denial’ (Cohen, Citation2001). It will help providers adopt a holistic view of their patients and understand what made them sick, thus fulfilling their professional role epitomised in the rule of Maimonides (1138–1204): ‘The physician should not treat the disease but the patient who is suffering from it’ (Rosner, Citation1981, p. 250). Furthermore, this training will encourage healthcare providers to become critical, engaged, organic intellectuals who represent subaltern social groups and challenge the hegemonic common sense (Gramsci, Citation1971).

According to Said, the raison d'être of intellectuals is to represent people and issues that are routinely forgotten, denied, or neglected. The intellectuals’ task is to confront dogma, raise embarrassing questions, unearth the forgotten, and cite alternative courses of action that could have avoided war, violence, and suffering (Said, Citation1994). An appropriate structural competency training that addresses the political conflict can encourage healthcare professionals to become critical intellectuals in the sense that Said proposed. Their unique position as those treating the victims of the conflict, and their professional commitment to social advocacy, make them potential agents of socio-political change. Structural competency will enhance their critical consciousness, which will allow them to question deeply seated social-political assumptions (Carrasco et al., Citation2019). An adapted structural competency training will motivate healthcare personnel to speak up about conflict-related forces that affect patients’ health, and lead collaborations between varied professionals and their marginalised patients (Bourgois et al., Citation2017; Metzl & Hansen, Citation2014; Metzl & Roberts, Citation2014).

To realise this goal, the conceptual framing of structural competency, which to date primarily addresses US concerns, should be broadened to include conflict-related issues and address the needs of the victims of severe structural violence in conflict areas. We suggest utilising the five elements of the TOLERance Model explained earlier (Orr & Unger, Citation2020b) to train healthcare providers. This training would include learning theoretical concepts and empirical studies on structural and conflict-related determinants of health; field trips to places that demonstrate the effects of structural forces, e.g. Palestinian hospitals and discussions with their medical staff; learning from structurally vulnerable patients who would co-train the medical professionals; initiating and leading structural interventions and social and political advocacy in funded projects; and conducting research on structural issues related to political violence.

Another new and novel method that can be implemented is the standardised patient simulation for enhancing structural competency in conflict areas (Orr et al., Citation2022). Simulation-based learning can help healthcare professionals to translate the theoretical comprehension of macro-level forces into clinical practices. Israeli-Palestinian activism-oriented workshops can also contribute to translating knowledge into joint action. The training should provide personal guidance and long-term professional, financial, and organisational support to the trainees, especially in the process of implementing their advocacy projects in their workplaces and beyond. Further, a ‘learning from success’ process, in which past successful instances are systematically analysed (Schechter et al., Citation2004), is recommended. Last, peer teaching and learning is highly effective in structural competency training (Rabinowitz et al., Citation2017).

The training should include an interplay between philosophical and empirical aspects; for example, learning philosophical ethical perspectives, such as deontological versus utilitarian approaches and theories of justice, and how they are manifested in concrete socio-political, health-related issues (Orr, Citation2022a, Citation2022b). Likewise, learners should understand both the philosophical and legal foundations of human rights and the right to health, and the practice of human rights and how to defend and promote the right to health.

We propose that academia (e.g. medical and nursing schools) can lead and coordinate this process by training undergraduate and graduate students, as well as professionals in continued education and in healthcare institutions, in all health professions. Academia can effectively incorporate the structural competency principles in the framework of evidence-based practice (Orr & Unger, Citation2020a). Moreover, the academia in many countries is usually more critical and independent than professional associations, such as medical and nursing associations. However, one should aim to involve these associations in the process, as they will likely help legitimise the training and bring it to more mainstream providers. Additionally, critical nongovernmental organisations, such as Physicians for Human Rights, can contribute a great deal to the training. Hospitals and health maintenance organisations should partake in the training programs, for example by hosting and guiding field trips and allowing participants to hold interventions in their frameworks. Finding ‘allies’ in healthcare institutions, who are dedicated to promoting structural competency, is vital. We believe that engaging all these institutions in the process and training as many individuals as possible will eventually affect not only these individuals’ perspective but also the broader dominant institutional perspective, in a bottom-up process.

Creating an adapted version of structural competency requires a collaboration of local and international, inter-professional, and inter-disciplinary team. This team should learn from previous cases of politicised healthcare providers such as in Nepal (Adams, Citation1998) and Egypt (Roborgh, Citation2018), but be sensitive and attentive to the unique needs of and restrictions imposed on local providers in any specific setting.

The proposed process is not without its challenges. Given the current right-wing populist discourse in Israel (Filc & Pardo, Citation2021), political engagement of clinicians may lead state authorities, politicians, nationalistic nongovernmental organisations, mainstream media, and many others in Israel and beyond to delegitimise the engaged clinicians, portraying them as ‘extreme’ or ‘unpatriotic’, as in the case of human rights activists (Lamarche, Citation2019). This backlash may result in reducing the engaged professionals’ social and political power. Prominent political engagement may even cause an opposite reaction by Israeli healthcare organisations that would not want to risk their professional legitimacy, prestige, power, autonomy, and monopoly granted by the state. While these troublesome potential risks must be taken seriously, we believe that the alternative of maintaining the status quo of ‘neutral healthcare’, overlooking chronic and severe violations of the right to health and to life, is more disastrous and less morally and professionally justifiable.

Salunke (Citation2020) shows that healthcare practitioners have increasingly taken a front-line position in many resistance movements worldwide, based on their professional authority over matters pertaining to the body, which gives them a great deal of power that they can use to subvert political exploitation by oppressive actors. Salunke concludes that ‘the medical community may just be at the forefront of sociopolitical revolutions and conflict transformation’ (p. 13). The Israeli healthcare leaders’ proactive and prominent reaction to the political violence of May 2021 can be interpreted as a beginning of such process, even though their engagement remained confined to the Green Line and used the political neutrality ethos. A structural competency training can build on this beginning and take the healthcare providers’ public engagement and leadership to the next phase of courageously confronting the conflict and political violence.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

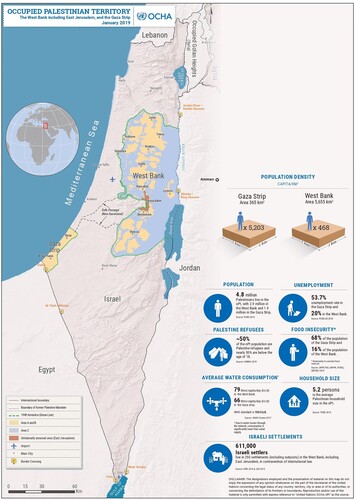

Figure 1. Map of the Occupied Palestinian Territory. Source: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs – Occupied Palestinian Territory. The original figure, which includes additional text boxes, is available at https://www.ochaopt.org/content/west-bank-including-east-jerusalem-and-gaza-strip-january-2019

Notes

1 The International Code of Medical Ethics of the World Medical Association states that ‘Medical ethics in times of armed conflict is identical to medical ethics in times of peace’ (World Medical Association, Citation2022, and see the opposing position of Gross, Citation2006).

2 Between March 16, 2012 and March 15, 2022.

3 These figures do not include indirect reasons such as access delays.

4 Between November 22, 2011 and November 21, 2021.

5 These figures do not include people who were killed or injured in conflict-related incidents that took place in Israel and did not involve residents of the occupied Palestinian territories.

6 Death tolls in the Gaza Strip and Israel Include those who died due to indirect consequences of hostilities, such as cardiac arrest.

7 The Green Line served as the de facto borders of Israel from 1949 until the 1967 war, in which Israel occupied the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip (as well as Sinai, which was later returned to Egypt, and the Golan Heights). Hence, Israel “within the Green Line” does not include the occupied West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip ().

8 The hospitals that comprise the Forum and signed this statement are Hadassah Medical Center (Jerusalem), Shaare Zedek Medical Center (Jerusalem), Mayanei HaYeshua Medical Center (Bnei Brak), The Holy Family Hospital (Nazareth), Nazareth Hospital EMMS (Nazareth), St. Vincent de Paul Hospital (Nazareth), and Laniado Hospital (Netanya).

9 Galilee Medical Center in Nahariya and Ziv Medical Center in Safed.

10 Among healthcare workers, several casualties and about 42 injured staff were recorded (World Bank Group et al., Citation2021).

References

- Abuelaish, I., Goodstadt, M. S., & Mouhaffel, R. (2020). Interdependence between health and peace: A call for a new paradigm. Health Promotion International, 35(6), 1590–1600. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daaa023

- Abu Hamad, B., Jones, N., & Gercama, I. (2021). Adolescent access to health services in fragile and conflict-affected contexts: The case of the Gaza Strip. Conflict and Health, 15(40). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-021-00379-0.

- Abu Laban, N., & Gawi, A. (2021, May 15). “Saving lives and fear for our lives”: Thousands of Arab medical staff went on strike today. Haaretz. https://www.haaretz.co.il/haaretz21/1.9810944 [Hebrew].

- Aciksoz, S. C. (2016). Medical humanitarianism under atmospheric violence: Health professionals in the 2013 Gezi protests in Turkey. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 40(2), 198–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-015-9467-2

- Adalah – The Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel. (2021, May 27). Adalah demands Israeli police end mass arrests of Palestinian citizens. https://www.adalah.org/en/content/view/10334.

- Adams, V. (1998). Doctors for democracy: Health professionals in the Nepal revolution. Cambridge University Press.

- Ad-El, D. D., Eldad, A., Mintz, Y., Berlatzky, Y., Elami, A., Rivkind, A. I., Almogy, G., & Tzur, T. (2006). Suicide bombing injuries: The Jerusalem experience of exceptional tissue damage posing a new challenge for the reconstructive surgeon. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 118(2), 383–387. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000227736.91811.c7

- Aharon, D., Orr, Z., Mana, K., Husseini, A., & Guttman, M. (2021, December 22). Palliative care for a baby in East Jerusalem: The structural determinants of care and the need for structural competency. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Israel Palliative Medicine Association and the Israel Association of Palliative Care [Hebrew].

- Barnes, A., & Parkhurst, J. (2014). Can global health policy be depoliticized? A critique of global calls for evidence-based policy. In G. W. Brown, G. Yamey, & S. Wamala (Eds.), The handbook of global health policy (pp. 157–173). Wiley Blackwell.

- Batniji, R., Rabaia, Y., Nguyen–Gillham, V., Giacaman, R., Sarraj, E., Punamaki, R.-L., Saab, H., & Boyce, W. (2009). Health as human security in the occupied Palestinian territory. The Lancet, 373(9669), 1133–1143. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60110-0

- Benton, A., & Atshan, S. (2016). “Even war has rules”: On medical neutrality and legitimate non-violence. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 40(2), 151–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-016-9491-x

- Bisharat, B. (2021, May 20). Jews and Arabs in the healthcare system, the sane anchor in the country - forever resilient? DoctorsOnly. https://shpac.doctorsonly.co.il/2021/05/228854/ [Hebrew].

- Blachar, Y. (2003). Israel Medical Association: Response to Derek Summerfield. The Lancet, 361(9355), 425. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12382-3

- Bourgois, P., Holmes, S. M., Sue, K., & Quesada, J. (2017). Structural vulnerability: Operationalizing the concept to address health disparities in clinical care. Academic Medicine, 92(3), 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001294

- B’Tselem – The Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories. (2022). Fatalities: All data. https://statistics.btselem.org/en/all-fatalities/by-date-of-incident.

- Carrasco, H., Messac, L., & Holmes, S. M. (2019). Misrecognition and critical consciousness—An 18-month-old boy with pneumonia and chronic malnutrition. New England Journal of Medicine, 380(25), 2385–2389. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1902028

- Chen, J., & Krieger, N. (2021). Revealing the unequal burden of COVID-19 by income, race/ethnicity, and household crowding: US county versus zip code analyses. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 27(S1), S43–S56. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000001263

- Cohen, S. (2001). States of denial: Knowing about atrocities and suffering. Polity.

- Collier, J., & Kienzler, H. (2018). Barriers to cardiovascular disease secondary prevention care in the West Bank, Palestine – A health professional perspective. Conflict and Health, 12(27). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-018-0165-x.

- Danino, B. (2021, May 13). Arabs and Jews, leave the hospitals out of bounds. Haaretz Blogs. https://www.haaretz.co.il/blogs/barrydanino/BLOG-1.9801061 [Hebrew].

- Diab, M., Veronese, G., Abu Jamei, Y., Hamam, R., Saleh, S., Zeyada, H., & Kagee, A. (2022). Psychosocial concerns in a context of prolonged political oppression: Gaza mental health providers’ perceptions. Transcultural Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1177/13634615211062968.

- Downey, M. M., Neff, J., & Dube, K. (2019). Don’t “just call the social worker”: Training in structural competency to enhance collaboration between healthcare social work and medicine. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 46(4), 77–95.

- Eghbariah, R. (2022). Israeli law and the rule of colonial difference. Journal of Palestine Studies, 51(1), 73–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/0377919X.2021.2007000

- Fahoum, K., & Abuelaish, I. (2019). Occupation, settlement, and the social determinants of health for West Bank Palestinians. Medicine, Conflict and Survival, 35(3), 265–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/13623699.2019.1666520

- Farmer, P. (2001). Infections and inequalities: The modern plagues. University of California Press.

- Filc, D., & Pardo, S. (2021). Israel’s right-wing populists: The European connection. Survival, 63(3), 99–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2021.1930409

- Galea, S. (2022). Physicians and the health consequences of war. JAMA Health Forum, 3(3), e220845. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.0845

- Gamzu, R. (2021, May 17). Do not let the intimidation undermine the coexistence between Jews and Arabs. N12. https://www.mako.co.il/news-columns/2021_q2/Article-d8175e230257971027.htm [Hebrew].

- Giacaman, R., Khatib, R., Shabaneh, L., Ramlawi, A., Sabri, B., Sabatinelli, G., Khawaja, M., & Laurance, T. (2009). Health status and health services in the occupied Palestinian territory. The Lancet, 373(9666), 837–849. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60107-0

- Giacaman, R., Rabaia, Y., Nguyen-Gillham, V., Batniji, R., Punamäki, R., & Summerfield, D. (2011). Mental health, social distress and political oppression: The case of the occupied Palestinian territory. Global Public Health, 6(5), 547–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2010.528443

- Golan, D., & Orr, Z. (2012). Translating human rights of the “enemy”: The case of Israeli NGOs defending Palestinian rights. Law & Society Review, 46(4), 781–814. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5893.2012.00517.x

- Golan, D., Rosenfeld, J., & Orr, Z. (2017). Campus-community partnerships in Israel: Commitment, continuity, capabilities, and context. In D. Golan, J. Rosenfeld, & Z. Orr (Eds.), Bridges of knowledge: Campus-community partnerships in Israel (pp. 9–41). Mofet Institute Publishing [Hebrew].

- Golan, D., & Shalhoub-Kevorkian, N. (2019). Engaged academia in a conflict zone? Palestinian and Jewish students in Israel. In D. Y. Markovich, D. Golan, & N. Shalhoub-Kevorkian (Eds.), Understanding campus-community partnerships in conflict zones: Engaging students for transformative change (pp. 15–38). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Golan-Agnon, D. (2020). Teaching Palestine on an Israeli university campus: Unsettling denial. Anthem Press.

- Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the prison notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. International Publishers.

- Gregg, J., & Saha, S. (2006). Losing culture on the way to competence: The use and misuse of culture in medical education. Academic Medicine, 81(6), 542–547. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ACM.0000225218.15207.30

- Gross, M. L. (2006). Bioethics and armed conflict: Moral dilemmas of medicine and war. MIT Press.

- Hagay, Z., Wertheim, E., Barhoum, M., Cohen, I., Kostiner, M., Levin, A., Bisharat, B., Zarka, S., Abu-Rabia, R., Feldman, Z., Bitterman, A., & Wapner, L. (2021). Medical personnel for reconciliation. https://ynet-images1.yit.co.il/picserver5/wcm_upload_files/2021/05/16/S1pp04000u/4_5836819465311882102.docx [Hebrew and Arabic].

- Hamdy, S. F., & Bayoumi, S. (2016). Egypt’s popular uprising and the stakes of medical neutrality. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 40(2), 223–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-015-9468-1

- Hammoudeh, W., Kienzler, H., Meagher, K., & Giacaman, R. (2020). Social and political determinants of health in the occupied Palestine territory (oPt) during the COVID-19 pandemic: Who is responsible? BMJ Global Health, 5(9), https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003683

- Hansen, H., Braslow, J., & Rohrbaugh, R. M. (2018). From cultural to structural competency—Training psychiatry residents to act on social determinants of health and institutional racism. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(2), 117–118. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3894

- Harvey, M., Neff, J., Knight, K. R., Mukherjee, J. S., Shamasunder, S., Le, P. V., Tittle, R., Jain, Y., Carrasco, H., Bernal-Serrano, D., Goronga, T., & Holmes, S. M. (2022). Structural competency and global health education. Global Public Health, 17(3), 341–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1864751

- Hiam, L., Gionakis, N., Holmes, S. M., & McKee, M. (2019). Overcoming the barriers migrants face in accessing health care. Public Health, 172, 89–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2018.11.015

- Holmes, S. M. (2013). Fresh fruit, broken bodies: Migrant farmworkers in the United States. University of California Press.

- Holmes, S. M., Hansen, H., Jenks, A., Stonington, S. D., Morse, M., Greene, J. A., Wailoo, K. A., Marmot, M. G., & Farmer, P. E. (2020). Misdiagnosis, mistreatment, and harm—When medical care ignores social forces. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(12), 1083–1086. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1916269

- Horton, R. (2009). The occupied Palestinian territory: Peace, justice, and health. The Lancet, 373(9666), 784–788. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60100-8

- Human Rights Watch. (2021). A threshold crossed: Israeli authorities and the crimes of apartheid and persecution. https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/media_2021/04/israel_palestine0421_web_0.pdf.

- International Committee of the Red Cross. (1949a). Geneva Convention (I) for the amelioration of the condition of the wounded and sick in armed forces in the field. https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/applic/ihl/ihl.nsf/xsp/.ibmmodres/domino/OpenAttachment/applic/ihl/ihl.nsf/4825657B0C7E6BF0C12563CD002D6B0B/FULLTEXT/GC-I-EN.pdf.

- International Committee of the Red Cross. (1949b). Geneva Convention (IV) relative to the protection of civilian persons in time of war. https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/applic/ihl/ihl.nsf/xsp/.ibmmodres/domino/OpenAttachment/applic/ihl/ihl.nsf/AE2D398352C5B028C12563CD002D6B5C/FULLTEXT/GC-IV-EN.pdf.

- Keshet, Y. (2020). Organizational diversity and inclusive boundary-work: The case of Israeli hospitals. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 39(4), 447–462. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-08-2019-0231

- Keshet, Y., & Popper-Giveon, A. (2017). Neutrality in medicine and health professionals from ethnic minority groups: The case of Arab health professionals in Israel. Social Science & Medicine, 174, 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.12.019

- Khoury, J. (2021, May 18). Arab-Israelis to strike amid surge in Gaza violence; Fatah and Hamas declare ‘day of rage.’ Haaretz. https://www.haaretz.com/middle-east-news/.premium.HIGHLIGHT-arab-israelis-to-strike-amid-surge-in-violence-fatah-hamas-declare-day-of-rage-1.9818099.

- Kienzler, H. (2019). Mental health in all policies in contexts of war and conflict. The Lancet Public Health, 4(11), e547–e548. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30208-7

- Lamarche, K. (2019). The backlash against Israeli human rights NGOs: Grounds, players, and implications. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 32(3), 301–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10767-018-9312-z

- Lavie, E., Elran, M., Shahbari, I., Sawaed, K., & Essa, J. (2021). Jewish-Arab relations in Israel, April-May 2021. https://www.inss.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/no.−1474.pdf.

- Lederman, Z. (2021). Together we lived, and alone you died: Loneliness and solidarity in Gaza. Developing World Bioethics, 21(1), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/dewb.12272

- Lederman, Z., Majadli, G., & Lederman, S. (2022). Responsibility and vaccine nationalism in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Developing World Bioethics, https://doi.org/10.1111/dewb.12343

- Lederman, Z., Shepp, E., & Lederman, S. (2018). Is Israel its brother’s keeper? Responsibility and solidarity in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Public Health Ethics, 11(1), 103–120. https://doi.org/10.1093/phe/phx004

- Leone, T., Alburez-Gutierrez, D., Ghandour, R., Coast, E., & Giacaman, R. (2019). Maternal and child access to care and intensity of conflict in the occupied Palestinian territory: A pseudo longitudinal analysis (2000-2014). Conflict and Health, 13(36). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-019-0220-2.

- Louis, M., & Maertens, L. (2021). Why international organizations hate politics: Depoliticizing the world. Routledge.

- Mackenbach, J. P. (2009). Politics is nothing but medicine at a larger scale: Reflections on public health’s biggest idea. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 63(3), 181–184. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2008.077032

- Mahamid, F. A., Veronese, G., & Bdier, D. (2022). The Palestinian health-care providers’ perceptions, challenges and human rights-related concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Human Rights in Healthcare, 15(4), 373–387. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHRH-04-2021-0083

- Manor, O., Skorecki, K., & Clarfield, A. M. (2020). Palestinian and Israeli health professionals, let us work together!. The Lancet Global Health, 8(9), e1129–e1130. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30324-7

- Matza, D. (2021). The May 2021 riots and their implications. https://besacenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/2067-May-2021-Riots-and-Their-Implications-Matza-English-final.pdf.

- Melino, K., Olson, J., & Hilario, C. (2022). A concept analysis of structural competency. Advances in Nursing Science, https://doi.org/10.1097/ANS.0000000000000442

- Metzl, J. M., & Hansen, H. (2014). Structural competency: Theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Social Science & Medicine, 103, 126–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.032

- Metzl, J. M., Maybank, A., & de Maio, F. (2020). Responding to the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA, 324(3), 231–232. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.9289

- Metzl, J. M., & Roberts, D. E. (2014). Structural competency meets structural racism: Race, politics, and the structure of medical knowledge. American Medical Association Journal of Ethics, 16(9), 674–690. https://doi.org/10.1001/virtualmentor.2014.16.9.spec1-1409.

- Ministry of Health. (2021). Manpower in the health professions 2020. https://www.health.gov.il/PublicationsFiles/manpower2020.pdf [Hebrew].

- Moss, D., & Majadle, G. (2020). Battling COVID-19 in the occupied Palestinian territory. The Lancet Global Health, 8(9), e1127–e1128. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30237-0

- Moss, D., Majadle, G., Milhem, J., & Waterston, T. (2021). Mental health impact on children of forcible home invasions in the occupied Palestinian territory. BMJ Paediatrics Open, 5(1), e001062. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2021-001062

- Neff, J., Holmes, S. M., Knight, K. R., Strong, S., Thompson-Lastad, A., McGuinness, C., Duncan, L., Saxena, N., Harvey, M. J., Langford, A., Carey-Simms, K. L., Minahan, S. N., Satterwhite, S., Ruppel, C., Lee, S., Walkover, L., de Avila, J., Lewis, B., Matthews, J., … Nelson, N. (2020). Structural competency: Curriculum for medical students, residents, and interprofessional teams on the structural factors that produce health disparities. MedEdPORTAL, 16(10888). https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10888.

- Orr, Z. (2016). Managing cultural diversity through multiculturalism in NGOs for social change: An Israeli case study. In C. Braedel-Kühner, & A. P. Müller (Eds.), Re-thinking diversity: Multiple approaches in theory, media, communities, and managerial practice (pp. 193–215). Springer VS.

- Orr, Z. (2022a). Localised medical moralities: Organ trafficking and Israeli medical professionals. The International Journal of Human Rights, https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2022.2081160

- Orr, Z. (2022b). The social construction of moral perceptions and public policies concerning organ trafficking in Israel. Sociological Forum, https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12869

- Orr, Z., Machikawa, E., Unger, S., & Romem, A. (2022). Enhancing the structural competency of nurses through standardized patient simulation. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 62, 25–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2021.09.005

- Orr, Z., & Unger, S. (2020a). Structural competency in conflict zones: Challenging depoliticization in Israel. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 21(4), 202–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527154420948050

- Orr, Z., & Unger, S. (2020b). The TOLERance model for promoting structural competency in nursing. Journal of Nursing Education, 59(8), 425–432. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20200723-02