ABSTRACT

Tuberculosis health care workers (TB HCWs) in low incidence settings have important perspectives on providing TB education and counselling to patients and family members born in other countries. The purpose of this qualitative study was to explore HCWs’ perspectives on barriers and facilitators for capacity-building education and counselling with patients and family members born outside of Canada experiencing advanced infectious TB in Calgary, a city in western Canada. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews and field notes and thematically analysed. Twenty-four HCWs representing clerical staff, nurses, physicians, and allied health professionals employed in TB care were interviewed. HCWs described how multi-level barriers such as patients’ fear of death, complex intra-family communication, information-laden appointments, and patients’ precarious employment collided resulting in overwhelmed patients and reduced connection to family. Some HCWs were unsure how to discuss TB stigma with patients and family members. HCWs perceived that increased continuity of care and providing patients and family members with digestible amounts of information earlier were important steps towards better practice. HCWs identified that patients and families could benefit from preparation for initial appointments, increased continuity, and improved patient education materials. HCWs should also receive skills-training to facilitate individual and family counselling.

Each year, approximately ten million people experience incident tuberculosis (TB) disease (World Health Organization, Citation2021, Citation2014) with an even larger number affected by the fear and socioeconomic losses surrounding this disease. Family members of those diagnosed with incident TB, worried for their own health and the health of their loved ones, are also profoundly affected by TB stigma, lost income, and the demands of preventative testing and treatment (Juniarti & Evans, Citation2011; Tanimura et al., Citation2014). Patients diagnosed with advanced infectious TB have a significant load of bacteria in the lungs which requires them to undergo a period of isolation from the community to protect public health. These patients often have more severe symptoms compared to individuals with other forms of TB (Long & Schwartzman, Citation2014) which may heighten fear in the family and increase exposure to stigma. All patients and families experiencing TB, but particularly those experiencing advanced infectious TB, require biomedical and psychosocial support (World Health Organization, Citation2014).

Canada is a low TB burden country with 1797 new and relapsed cases diagnosed in 2018 (Public Health Agency of Canada, Citation2020) and an annual estimated incidence rate of 5.3/100,000 (World Health Organization, Citationn.d.). Over 73% of those who experience TB in Canada are born outside of the country (Public Health Agency of Canada, Citation2020). Thus, the majority of families experiencing TB in Canada are comprised fully or partly of those born outside of the country. Canadian TB programmes must be attuned to the needs of this population in order to provide supportive care and protect public health (Reitmanova & Gustafson, Citation2012). Over and above distinct linguistic and cultural needs, patients and family members experiencing TB post-migration also require support to overcome stigma, racism, and precarious employment which can deepen the negative impacts of TB (Galabuzi, Citation2016; Gushulak et al., Citation2011; Hira-Friesen, Citation2018; Juniarti & Evans, Citation2011).

Building patient and family members’ capacity for wellbeing through education and counselling is key to supportive TB care. However, the literature is replete with examples of TB education and counselling that does not build patient and family capacity, but instead confuses and reinforces stigma (Brumwell et al., Citation2018; McEwen, Citation2005; Sagbakken et al., Citation2012; Skinner & Claassens, Citation2016). Patient and family centred improvements to current practice are needed, however, there is little evidence available to guide practice (Brumwell et al., Citation2018; Foster et al., Citation2022). We have drawn on the work of others (Castro et al., Citation2016; M'Imunya et al., Citation2012) to define capacity-building TB education and counselling as a process whereby health care workers (HCWs) provide patients and family members with information, guidance, and skills to support self-identification of needs and action towards wellbeing. While patient and family member perspectives are essential for improving capacity-building TB education and counselling, HCW perspectives are also critical. HCWs’ perspectives are informed by daily, often intimate experiences of supporting patient and family members with their self-identified needs amidst the constraints of the health care system. Gathering HCW perspectives can provide a basis from which to address health services barriers. The purpose of this study was to explore HCWs perspectives on barriers and facilitators for capacity-building education and counselling for patients and family members who are born outside of Canada and experiencing advanced infectious TB.

Setting

This study took place at Calgary TB Clinic (CTBC) located in Alberta, Canada. CTBC is the sole provider of TB services for 1.5 million people who reside in the ‘Calgary Zone’ (Alberta Health Services, Citationn.d.). The zone is 39,300 kms2 in size, and compromised of the city of Calgary, neighbouring bedroom communities, and rural regions (Alberta Health Services, Citationn.d.). In terms of population, the zone is dominated by the city of Calgary which contains 1.4 million people in 820 kms2 of the total zone area (Government of Alberta, Citation2022; Statistics Canada, Citation2022). In 2020, 108 people were newly diagnosed with active TB in Calgary; 102 (94%) lived in the city of Calgary, and 106 (98%) were born outside of Canada (Alberta Tuberculosis Program, Citation2021). An on-demand language interpretation service is widely used in the clinic and many patient education materials are available in nine languages including English.

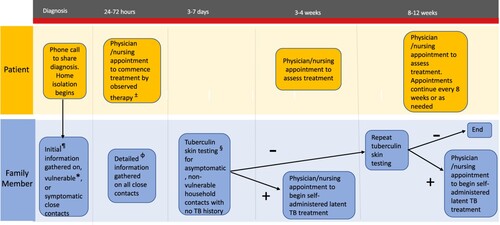

Advanced infectious TB is defined at CTBC as a smear positive result (i.e. any grade) on at least one sputum sample tested for acid fast bacilli with smear microscopy. Routine care for patients and family members experiencing advanced infectious TB in Calgary is based on national guidelines (Menzies, Citation2014) and depicted in . Patients are required to isolate at home for three weeks and asked to attend appointments for assessment and directly observed therapy. Isolation for most patients involves remaining at home, refusing new visitors, and only entering other buildings while masked to attend medically necessary appointments. Family members are also asked to attend appointments for testing and treatment (if required). While numerous contacts between patients, family members, and HCWs over the first 8–12 weeks present many opportunities for TB education and counselling, the process can be complex to navigate and onerous for families.

Figure 1. Routine care for patients and family members 8–12 weeks post diagnosis.

¶Initial information consists of household contact age and current symptoms. *Less than 5 years of age or profoundly immunocompromised. ɸDetailed information consists of age, current symptoms, TB history, and overall health history. ±Nursing appointments for medication five days per week × 8 weeks. Frequency often reduced after 8 weeks. §Consists of two nursing appointments 48–72 hours apart.

A multidisciplinary team comprised of clerical staff, registered and practical nurses, physicians, and allied health workers deliver care at the clinic. Clerical staff communicate with patients and family members to organise appointments. Nurses inform patients of their diagnoses, explain the requirements of home isolation, provide treatment counselling, conduct contact investigations, and organise and administer directly observed therapy with a combination of phone and in person communication. Physicians diagnose, initiate treatment, and monitor patient and family member progress at scheduled appointments. A limited number of allied health workers are employed at the Calgary TB Clinic to support patient and family members’ additional medical and psychosocial needs related to treatment that cannot be adequately addressed by physicians and nurses. Allied health workers communicate with patients and family members through phone and in person communication as needed throughout their TB treatment.

Methods

This research comprised one component of a qualitative case study (Abma & Stake, Citation2014; Stake, Citation1995) which was conducted in Calgary and directed at how education and counselling can be used to improve the experience of patients and their family members who are born outside of Canada. The overall case study was theoretically framed according to the social-ecological levels (Golden & Earp, Citation2012; McLeroy et al., Citation1988). These levels were intrapersonal (i.e. characteristic of the individual), interpersonal (i.e. within social network), institutional (i.e. characteristic of organisations with formal operational rules), and structural (i.e. inclusive of community norms and public policy). The study component presented here was focused on the institutional level. Other study components, presented elsewhere, were directed at individual and family levels, as well as at policy and structural issues (Bedingfield et al., Citation2022a, Citation2022b, Citation2022c).

Recruitment and sampling

Eligible participants were HCWs employed at CTBC for at least 6 months in any capacity involving patient interaction. Participants were recruited through presentations at staff meetings and an email sent by the clinic manager to all staff and physicians. HCWs interested in participation were asked to email the first author (NB) or place a paper ballot in a box located at the clinic. NB then contacted potential participants to provide more information about the study and arrange an interview if appropriate. All willing and eligible HCWs were interviewed. The study was approved by the University of Calgary/Alberta Health Services Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (REB19-0366).

Data collection

Following receipt of informed consent, NB conducted semi-structured, individual interviews with all but two participants whose request to be interviewed together was accommodated. Interviews were 19–63 minutes in duration. The research team, comprised of NB as well as faculty experienced in TB, qualitative methods, and culturally safe care, provided input on the interview guide. Questions were directed at exploring barriers, facilitators, and suggestions to education and counselling for patients experiencing advanced infectious TB and their family members who are born outside of Canada. As a registered nurse and researcher, with 13 years of experience at the CTBC, NB had pre-existing professional relationships with participants. Interviews were conducted during the global COVID-19 pandemic between April and July 2020. To reduce the risk of COVID-19 transmission, workplace health and safety measures for masking and distancing were followed, and in-person interviews (n = 20) were scheduled to coincide with existing clinical work. Three interviews were conducted by secure video call, and in these cases, consent was obtained verbally rather than in writing. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by a trained transcriptionist, subject to a confidentiality agreement. NB recorded field notes after each interview which focused on the interview process and non-verbal communication.

Analysis

NB coded transcripts using NVivo software (QSR International v.12) and reviewed interim and final analyses with the research team. A combination of inductive and deductive techniques were used following the steps for thematic analysis outlined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). NB familiarised herself with the data by listening to interviews whilst reviewing transcripts, then worked line by line, coding data segments with a two-part code. The first part of the code categorised data as a barrier, facilitator, suggestion, or other. The second part of the code was based on the content of the segment (e.g. barrier- physical space; facilitator- family spokesperson; other- priority education topics). First-level codes were then grouped by social-ecological level (Golden & Earp, Citation2012; McLeroy et al., Citation1988) and codes relevant to capacity-building education and counselling were extracted. Finally, themes were produced by progressively refining and collating first-level codes. An audit trail of analytic logic and decisions was maintained using software and paper records.

Results

Participants were predominately women reflecting the gender make-up of the clinic. A detailed breakdown of participants’ gender cannot be provided so as to protect patient confidentiality. Fifteen participants were born in Canada and nine were born in other countries. Eight participants could provide care in languages in addition to English when required, and the remaining sixteen communicated with patients and family members only in English. contains demographic information from participating HCWs.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of Calgary health care workers participating in 2020 data collectionTable Footnotea.

Results are presented in three dimensions. The first dimension, obstacles to communication and family stress, is focused on HCWs perceptions of barriers to effective communication with patients and family members. The second and third dimensions, building trust, and laying a foundation of TB knowledge, are concentrated on strategies HCWs used, or suggested could be used, to facilitate education and counselling. A list of barriers and facilitators identified by HCWs organised by the four social ecological levels is located in (Golden & Earp, Citation2012; McLeroy et al., Citation1988).

Table 2. Health care worker perceptions of barriers and facilitators to advanced infectious TB education and counselling with patients and family members born outside of Canada.

Although participants were asked about their interactions with patients and family members broadly, HCWs’ comments often focused on the first 2 months of treatment. They described this as a difficult period when patient and family members had many significant concerns related to managing disease symptoms and medication tolerance, home isolation, and contact investigation. HCWs observed that multi-level barriers to communication often collided and overlapped during this time resulting in patients receiving too much destabilising information at once, and family members being left anxious, without any information for days or weeks.

Family stress and other obstacles to communication

HCWs reported that patient and family members’ knowledge and beliefs about TB, and corresponding intense emotions, could be a barrier to communication. HCWs identified that patients and family members often felt very stressed and afraid, particularly in days following diagnosis. Many suspected that patient and family members’ fearful misperceptions about TB were the root cause of high stress levels, which impaired their ability to absorb new information. HCWs identified many possible causes for patient and family members’ distress. Some patients and family members were afraid of death, some were very concerned about the ramifications of TB stigma, and still others felt discouraged when they heard about the onerous demands and long duration of TB treatment. HCWs noted that patients and family members were more likely to feel distressed during early interactions when problems appeared to be many and solutions few. SusanFootnote1, an allied health worker highlighted patients’ reaction to home isolation,

Just right from the beginning, we tell them that they have to be off work for 3 weeks. … That instils panic instantly in most people being told that you can't go back to work. There's either a lack of sick time or just lack of instant coverage when you just suddenly leave a job for 3 weeks, as well as the stigma of not wanting their employers to know why they're gone.

HCWs described struggling to navigate the intricacies of family group communication at a sensitive time. Many expressed their desire to both protect the patient's wishes for privacy, and support family members, but found that these objectives sometimes clashed. Olivia, a nurse, described this challenge,

In our (Western) culture, you know, we need confidentiality … if we’re going to talk to a family member, we have to have it signed off. I think (that's) really confusing for some family members.

It turned out that the patient was spending about 2 weeks at one family's house, and then moving to another family's house. … (The story sometimes) … becomes more complicated as you contact people and find out more information

HCWs discussed how the structure and requirements of the health care system could make it difficult to meet patient and family members’ needs. For example, patients and family members needed to be able to attend appointments and answer phone calls between 0815 and 1630, Monday to Friday; often patients and family members were not available during these times. HCWs described making multiple attempts to connect with patients by phone or arrange appointments to fit patient and family members’ commitments to work, school, and family caregiving. Clerical staff, responsible for booking appointments, described a common problem; patients and family members often asked why their appointment was necessary and if attendance was ‘worth’ the high price in terms of missed work and transportation. Clerical staff needed to explain, or even persuade patients and family members to attend and some felt these conversations could extend beyond their scope of practice.

HCWs also described having to manage competing demands with limited time. NB asked HCWs how they prioritised education and counselling when time constraints forced them to make choices. Most said that items related to public health protection and medication safety were attended to, but discussions intended to provide reassurance, clarify confusing topics, or arrange preventative care could be delayed, condensed, or even skipped. For example, several nurses stated that phone calls to family members for preventative care were often delayed longer than they wished. Isabel, a nurse, described why clarifying conversations did not always happen:

Often you’re busy. You have that time pressure which can … make it difficult to have the length of conversation … you need to have based on how the patient is understanding

Some HCWs were uncertain if they had the necessary skills to discuss TB stigma with patients and family members. When asked about communication training taken in the last 5 years, no HCWs had received any training on TB stigma. Lee described her reluctance to raise the issue, ‘you just don't feel quite confident to address it straight-on because you're not even sure. Let's say it's not a thing (for them)? Then you feel bad for assuming’. HCWs were asked how they usually advised patients and family members to manage stigma. Most said they encouraged patients and family members not to share their TB experience outside a small, trusted circle. Katie's response was characteristic of others’, ‘I explain to people not to tell. Like, it's their choice. It's their health information, and so they are under no obligation to tell their employer, or friends, and family’. Only Susan took a different approach, advising patients to carefully weigh the pros and cons of disclosure because discretion was sometimes necessary, but could also be limiting:

If they choose to share, it can really be a good thing and a positive thing. … If they’ve really told no one, they’ve also then boxed themselves in. Like their friend could be going through the exact same thing and (they wouldn't) have that support.

I once talked to a patient with an interpreter. I spent 30 minutes explaining, every (step in the process) was translated. The patient came the following day, and he doesn't understand a single th(ing)

Socioeconomic vulnerability for people who are born outside of Canada was also mentioned frequently. HCWs described how low paying, insecure employment made it difficult for patients and family members to prioritise TB care. This quote from Nala, a member of the clerical team, illustrated how power imbalances in the workplace impaired communication with HCWs through reduced appointment attendance,

If the person is on a work permit or a new immigrant … (yes) we can give them a medical note but … (their employer still) … might not allow that flexibility to take time off

Building trust

HCWs observed that providing education and counselling was much easier once they built trust with patients and family members. HCWs also described how learning the right combination of slow, unrushed appointments, frequent, short educational messages, group conversations, and private interactions that worked for each family was a process which could sometimes be slow. Trust was not only necessary to exchange basic information, but also to reduce patient and family members’ sense of vulnerability. Several multilingual HCWs described the visceral relief they perceived from patients when the conversation switched to a more comfortable language. Amina, a member of the clerical team described this experience,

When I start speaking to them in a language that they understand … it's a sense of relief, because for them they no longer view this place as ‘foreign’ – they view it as, okay, someone is going to be able to help and I'm going to understand what is happen(ing) here.

HCWs noted that they were able to overcome many communication problems once they had consistent interactions with the same patient and family members. Communication became comfortable and many intangible barriers to patient and family member participation fell away. Kathleen, a nurse, described a recent experience, ‘just yesterday (I had a family member say to me), “oh it's you!” She goes, “now I can ask some more questions!”’.

Laying a foundation of TB information

HCWs suggested that patients and family members would be less afraid and better able to use TB information if it was provided earlier, more often, and in simple formats. Given high learning needs at early stages, several HCWs recommended that patients and family members should be prepared for their first appointment. Emma explained how she tried to spend more time on initial phone calls ‘(I do that) so they have a little bit of a base of information … (as opposed to) not knowing anything (when they arrive) and thinking of questions after they leave’. Dr. Garcia described how early phone counselling could set patients up for a better experience: ‘I mean, it would be nice to bring them along. Maybe (the nurses should) even have more than one conversation with the patient before they hit clinic’. Many HCWs noted that when they had extra time at the initial appointment, patients and family members felt less rushed and tended to open up about concerns regarding the impact of TB on employment, finances, and family.

HCWs reported that patients and family members often found aspects of TB care confusing and suggested that repetition, in the form of follow-up conversations and pamphlets, were needed to review and fully explain. Short, simple education messages could be delivered effectively during follow-up conversations, but only if the HCW was consistent from one interaction to the next. HCWs valued the reinforcement provided by print materials but suggested that current materials needed to be improved by being available in more languages, incorporating more images and less text, and containing information on common psychosocial concerns. Kathleen described how she had seen translated pamphlets cut through language barriers,

Its amazing when you do give the written language that that person can read. You see that they actually understand, like how their face kind of lights up. ‘Oh man, I can understand this!’

Discussion

HCWs at CTBC described how factors as far ranging as fear of death, complex intra-family communication, information-laden appointments, and precarious employment collided to leave patients feeling overwhelmed and family members with delayed connection to HCWs. HCWs perceived that increased continuity and providing patients and family members with digestible amounts of information earlier in the process were important steps towards better practice.

Many HCWs in this study expressed concern that psychosocial issues were not adequately addressed by current education and counselling practice. This echoes with concerns reported by TB researchers who have pointed out the general lack of psychosocial counselling in TB care (Brumwell et al., Citation2018; Clarke et al., Citation2021; Daftary et al., Citation2015; McEwen, Citation2005; Moodley et al., Citation2020), despite considerable evidence of the devastating social and emotional losses experienced by families affected by TB (Acha et al., Citation2007; Macintyre et al., Citation2017; Shedrawy et al., Citation2019; Tanimura et al., Citation2014). When emotional and social issues are not addressed, patients and family members miss out on critical opportunities to reduce isolation and problem solve with trained health care providers. Counselling on TB stigma in Calgary is an example of one such missed opportunity. Some HCWs were reluctant to raise the issue of stigma and most advised patients and family members to protect themselves from discrimination by limiting disclosure. However, overt discrimination is only one way stigma can lead to devaluation of character and advising patients and family members to limit disclosure does not ameliorate the negative self-perception and fear of exclusion which are believed by some to be more insidious forms of t (Ritsher & Phelan, Citation2004). There is a dearth of evidence regarding effective ways to fight TB stigma (Macintyre et al., Citation2017; Sommerland et al., Citation2017). Researchers in other fields have demonstrated the effectiveness of psychoeducational sessions which support families by building resilience against stigma through correcting misperceptions, enhancing personal coping skills, and developing supportive social networks (Bhana et al., Citation2014; Ngoc et al., Citation2016). Psychoeducational sessions help to patients and family members experiencing TB, but family sessions can be difficult to conduct, particularly across cultures, and health care providers require training to effectively support everyone present (Singer et al., Citation2016).

Anti-TB stigma interventions at the community and societal level are often overlooked (Craig et al., Citation2017; Sommerland et al., Citation2017) but could be valuable ways to reduce barriers counselling identified by HCWs in this study. For example, a multilingual marketing campaign directed at ethnocultural communities affected by TB could portray people taking TB treatment in a positive light, thereby educating patients and family members on the curability of TB and reducing patient and family member internalised stigma. Similarly, a media campaign directed at the general public raising awareness of the benefits of migration and the importance of better working conditions for people who are born outside of Canada could support TB counselling by reducing patient and family members’ internalised stigma and may eventually reduce work-related barriers to education and counselling for patients and family members.

There is considerable alignment between the barriers and facilitators to capacity-building TB education and counselling identified by HCWs in this study and the broader patient education literature. We highlight three areas of congruence. Firstly, HCWs suggested that providing patients and family members with orientation information in advance of their first appointment could minimise overload and increase participation. Participation has been linked to improved patient outcomes (Clayman et al., Citation2016). Linguistic and cultural dissonance is a well-known barrier to participation (Greenhalgh et al., Citation2006; Lee & Lin, Citation2010; Mantwill & Schultz, Citation2018; Schouten & Meeuwesen, Citation2006) and preparing patients for their first appointment by letting them know what to expect and encouraging them to ask questions has been shown to increase participation and reduce anxiety, particularly in foreign-born populations (Haywood et al., Citation2006; Servellen et al., Citation2005; Sheppard et al., Citation2008). Secondly, HCWs identified that continuity of care facilitated increased patient participation and follow-up education opportunities. Indeed, a lack of continuity is known to impair patient-provider communication, and limited studies have demonstrated a positive relationship between continuity of care, psychosocial support, and patient participation (Armas et al., Citation2018; Barimani & Vikström, Citation2015; Van Wersch et al., Citation1997). Finally, HCWs in Calgary suggested that printed education materials were useful but needed to be updated. Printed teaching materials are known to increase patient comprehension, with materials incorporating images being particularly helpful for those with limited-English proficiency (Clayman et al., Citation2016; Friedman et al., Citation2011; Haywood et al., Citation2006; Schubbe et al., Citation2020). Our research extends the existing literature by demonstrating that clerical staff have an opportunity and are willing to disseminate basic information to patients and family members prior to their appointments.

The findings of this study have high knowledge translation value and can be used to select interventions for improving capacity-building education and counselling. While results are specific to Calgary, TB epidemiology and the social determinants of health for migrants follow similar trends in other high-income countries (Lönnroth et al., Citation2015, Citation2017; Pareek et al., Citation2016; Tomás et al., Citation2013) and findings may have wider application. Study results are detailed, which will help readers assess transferability to their own settings. The pre-existing relationship between NB and participants presented strengths and limitations for this work. Shared knowledge and experience likely facilitated deeper responses but may also have resulted in blind-spots, provoked socially desirable responses, or inhibited participants concerned about confidentiality. Similarly, conducting interviews at the clinic was convenient for many but may have deterred others. Efforts to mitigate limitations presented by the relationship between NB and participants were made at several stages of the research process. Co-authors who did not have connections to the Calgary TB Clinic contributed to development of the interview guide and data analysis. During the informed consent process NB highlighted procedures in the research process to protect participants’ confidentiality. During the informed consent process NB also emphasised the value of gathering diverse perspectives on the research topic to minimise socially desirable responses and encourage participants to speak freely.

Conclusion

Advocacy groups, the World Health Organization, and the United Nations have affirmed patients’ right to a comprehensive TB education and counselling tailored to their unique circumstances (Citro, Citation2020; United Nations General Assembly, Citation2018; World Health Organization, Citation2014). HCWs perceived that numerous barriers existed which inhibited the provision of such capacity-building education and counselling in Calgary. Based on the results of this study, interventions which may improve education and counselling include phone counselling for patients prior to initial appointments, skills-training on psychoeducation counselling for HCWs, and improving translated patient education materials. Such interventions could help to provide patients and family members who are born outside of Canada with the knowledge, skills, and relationships required to manage their own health both during and after TB treatment.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the staff, physicians, and management at the Calgary TB Clinic for their generous support of this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 All quoted participants are identified with pseudonyms.

References

- Abma, T., & Stake, R. (2014). Science of the particular: An advocacy of naturalistic case study in health research. Qualitative Health Research, 24(8), 1150–1161. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732314543196

- Acha, J., Sweetland, A., Guerra, D., Chalco, K., Castillo, H., & Palacios, E. (2007). Psychosocial support groups for patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: Five years of experience. Global Public Health, 2(4), 404–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441690701191610

- Alberta Health Services. (n.d.). Calgary zone stats. Retrieved October 29, 2022, from https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/zone/ahs-zn-calgary-map-brochure.pdf.

- Alberta Tuberculosis Program. (2021). 2020 Active case report. [Unpublished data].

- Armas, A., Meyer, S. B., Corbett, K. K., & Pearce, A. R. (2018). Face-to-face communication between patients and family physicians in Canada: A scoping review. Patient Education and Counseling, 101(5), 789–803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2017.11.008

- Barimani, M., & Vikström, A. (2015). Successful early postpartum support linked to management, informational, and relational continuity. Midwifery, 31(8), 811–817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2015.04.009

- Bedingfield, N., Lashewicz, B., Fisher, D., & King-Shier, K. (2022a). Contextual influences on TB education and counseling for patients and family members who are foreign-born [Unpublished manuscript]. Department of Community Health Sciences. Cumming School of Medicine. University of Calgary. https://prism.ucalgary.ca/handle/1880/114908

- Bedingfield, N., Lashewicz, B., Fisher, D., & King-Shier, K. (2022b). Improving infectious TB education for foreign-born patients and family members. Health Education Journal, 81(2), 170–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/00178969211061522

- Bedingfield, N., Lashewicz, B., Fisher, D., & King-Shier, K. (2022c). Systems of support for foreign-born TB patients and their family members. Public Health in Action, 12(2), 79–84. https://doi.org/10.5588/pha.21.0081

- Bhana, A., Mellins, C. A., Petersen, I., Alicea, S., Myeza, N., Holst, H., Abrams, E., John, S., Chhagan, M., & Nestadt, D. F. (2014). The VUKA family program: Piloting a family-based psychosocial intervention to promote health and mental health among HIV infected early adolescents in South Africa. AIDS Care, 26(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2013.806770

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brumwell, A., Noyes, E., Kulkarni, S., Lin, V., Becerra, M., & Yuen, C. (2018). A rapid review of treatment literacy materials for tuberculosis patients. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 22(3), 336–341. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.17.0363

- Castro, E. M., Van Regenmortel, T., Vanhaecht, K., Sermeus, W., & Van Hecke, A. (2016). Patient empowerment, patient participation and patient-centeredness in hospital care: A concept analysis based on a literature review. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(12), 1923–1939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.026

- Citro, B. (2020). Activating a human rights-based tuberculosis response: A technical brief for policy makers and program implementers. Global Coalition of TB Activitst with Stop TB Partnership and Northwestern Western Pritzker School of Law Centre for Human Rights. Retrieved May 25, 2020, from http://gctacommunity.org/?page_id=7493&v=7d31e0da1ab9.

- Clarke, A. L., Sowemimo, T., Jones, A. S., Rangaka, M. X., & Horne, R. (2021). Evaluating patient education resources for supporting treatment decisions in latent tuberculosis infection. Health Education Journal, 80(5), 513–528. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896921990066

- Clayman, M. L., Bylund, C. L., Chewning, B., & Makoul, G. (2016). The impact of patient participation in health decisions within medical encounters: A systematic review. Medical Decision Making, 36(4), 427–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X15613530

- Craig, G. M., Daftary, A., Engel, N., O’driscoll, S., & Ioannaki, A. (2017). Tuberculosis stigma as a social determinant of health: A systematic mapping review of research in low incidence countries. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 56(C), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2016.10.011

- Daftary, A., Calzavara, L., & Padayatchi, N. (2015). The contrasting cultures of HIV and tuberculosis care. AIDS (London, England), 29(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000000515

- Foster, I., Nathavitharana, R., & Sullivan, A. (2022). The role of counselling in tuberculosis diagnostic evaluation and contact tracing: Scoping review and stakeholder consultation of knowledge and research gaps. BMC Public Health, 22(90), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12556-8

- Friedman, A. J., Cosby, R., Boyko, S., Hatton-Bauer, J., & Turnbull, G. (2011). Effective teaching strategies and methods of delivery for patient education: A systematic review and practice guideline recommendations. Journal of Cancer Education, 26(1), 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-010-0183-x

- Galabuzi, G. (2016). Social exclusion. In D. Raphael (Ed.), Social determinants of health: Canadian perspectives (3rd ed, pp. 388–418). Canadian Scholar's Press Inc.

- Golden, S. D., & Earp, J. L. (2012). Social ecological approaches to individuals and their contexts: Twenty years of health education & behavior health promotion interventions. Health Education & Behavior, 39(3), 364–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198111418634

- Government of Alberta. (2022). Calgary population. Retrieved October 29, 2022, from https://regionaldashboard.alberta.ca/region/calgary/population/#/?from=2017&to=2021.

- Greenhalgh, T., Robb, N., & Scambler, G. (2006). Communicative and strategic action in interpreted consultations in primary health care: A Habermasian perspective. Social Science & Medicine, 63(5), 1170–1187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.033

- Gushulak, B. D., Pottie, K., Roberts, J. H., Torres, S., & DesMeules, M. (2011). Migration and health in Canada: Health in the global village. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 183(12), E952–E958. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.090287

- Haywood, K., Marshall, S., & Fitzpatrick, R. (2006). Patient participation in the consultation process: A structured review of intervention strategies. Patient Education and Counseling, 63(1–2), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2005.10.005

- Hira-Friesen, P. (2018). Immigrants and precarious work in Canada: Trends, 2006–2012. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 19(1), 35–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-017-0518-0

- Juniarti, N., & Evans, D. (2011). A qualitative review: The stigma of tuberculosis. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20(13–14), 1961–1970. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03516.x

- Lee, Y.-Y., & Lin, J. L. (2010). Do patient autonomy preferences matter? Linking patient-centered care to patient–physician relationships and health outcomes. Social Science & Medicine, 71(10), 1811–1818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.08.008

- Long, R., & Schwartzman, K. (2014). Chapter 2: Pathogenesis and transmission of tuberculosis. In D. Menzies (Ed.), Canadian tuberculosis standards (7th ed.) (pp. 25–42). Public Health Agency of Canada. Retrieved February 28, 2020, from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/infectious-diseases/canadian-tuberculosis-standards-7th-edition/edition-14.html.

- Lönnroth, K., Migliori, G. B., Abubakar, I., D'Ambrosio, L., De Vries, G., Diel, R., Douglas, P., Falzon, D., Gaudreau, M.-A., & Goletti, D. (2015). Towards tuberculosis elimination: An action framework for low-incidence countries. European Respiratory Journal, 45(4), 928–952. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00214014

- Lönnroth, K., Mor, Z., Erkens, C., Bruchfeld, J., Nathavitharana, R., Van Der Werf, M., & Lange, C. (2017). Tuberculosis in migrants in low-incidence countries: Epidemiology and intervention entry points. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 21(6), 624–636. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.16.0845

- Macintyre, K., Bakker, M. I., Bergson, S., Bhavaraju, R., Bond, V., Chikovore, J., Colvin, C., Craig, G., Cremers, A., & Daftary, A. (2017). Defining the research agenda to measure and reduce tuberculosis stigmas. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 21(11), S87–S96. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.17.0151

- Mantwill, S., & Schultz, P. (2018). Chapter 4: Patient involvement exploring differences in doctor–patient interaction among immigrants and non-immigrants with back pain in Switzerland. In Y. Mao, & R. Ahmed (Eds.), Culture, migration, and health communication in a global context (pp. 63–86). Routledge.

- McEwen, M. M. (2005). Mexican immigrants’ explanatory model of latent tuberculosis infection. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 16(4), 347–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659605278943

- McLeroy, K. R., Bibeau, D., Steckler, A., & Glanz, K. (1988). An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly, 15(4), 351–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019818801500401

- Menzies, D. (Ed.). (2014). Canadian tuberculosis standards (7th ed.). Public Health Agency of Canada. Retrieved March 20, 2020, from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/infectious-diseases/canadian-tuberculosis-standards-7th-edition.html.

- M'Imunya, J. M., Kredo, T., & Volmink, J. (2012). Patient education and counselling for promoting adherence to treatment for tuberculosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 5, Article CD00659. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006591.pub2

- Moodley, N., Saimen, A., Zakhura, N., Motau, D., Setswe, G., Charalambous, S., & Chetty-Makkan, C. (2020). ‘They are inconveniencing us’ – Exploring how gaps in patient education and patient centred approaches interfere with TB treatment adherence: Perspectives from patients and clinicians in the Free State Province, South Africa. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08562-3

- Ngoc, T., Weiss, B., & Trung, L. (2016). Effects of the family schizophrenia psychoeducation program for individuals with recent onset schizophrenia in Viet Nam. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 22, 162–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2016.06.001

- Pareek, M., Greenaway, C., Noori, T., Munoz, J., & Zenner, D. (2016). The impact of migration on tuberculosis epidemiology and control in high-income countries: A review. BMC Medicine, 14(48), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-016-0595-5

- Public Health Agency of Canada. (2020). Tuberculosis in Canada: 2008–2018 data. Retrieved October 30, 2022, from https://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/4dbb9bff-022d-4aab-a11d-0a2e1b0afaad.

- Reitmanova, S., & Gustafson, D. (2012). Rethinking immigrant tuberculosis control in Canada: From medical surveillance to tackling social determinants of health. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 14(1), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-011-9506-1

- Ritsher, J. B., & Phelan, J. C. (2004). Internalized stigma predicts erosion of morale among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatry Research, 129(3), 257–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2004.08.003

- Sagbakken, M., Bjune, G. A., & Frich, J. C. (2012). Humiliation or care? A qualitative study of patients’ and health professionals’ experiences with tuberculosis treatment in Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 26(2), 313–323. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2011.00935.x

- Schouten, B. C., & Meeuwesen, L. (2006). Cultural differences in medical communication: A review of the literature. Patient Education and Counseling, 64(1–3), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2005.11.014

- Schubbe, D., Scalia, P., Yen, R. W., Saunders, C. H., Cohen, S., Elwyn, G., van den Muijsenbergh, M., & Durand, M.-A. (2020). Using pictures to convey health information: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects on patient and consumer health behaviors and outcomes. Patient Education and Counseling, 103(10), 1935–1960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2020.04.010

- Servellen, G. V., Nyamathi, A., Carpio, F., Pearce, D., Garcia-Teague, L., Herrera, G., & Lombardi, E. (2005). Effects of a treatment adherence enhancement program on health literacy, patient–provider relationships, and adherence to HAART among low-income HIV-positive Spanish-speaking Latinos. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 19(11), 745–759. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2005.19.745

- Shedrawy, J., Jansson, L., Röhl, I., Kulane, A., Bruchfeld, J., & Lönnroth, K. (2019). Quality of life of patients on treatment for latent tuberculosis infection: A mixed-method study in Stockholm, Sweden. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 17(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-019-1228-4

- Sheppard, V. B., Figueiredo, M., Cañar, J., Goodman, M., Caicedo, L., Kaufman, A., Norling, G., & Mandelblatt, J. (2008). Latina a LatinaSM: Developing a breast cancer decision support intervention. Psycho-Oncology, 17(4), 383–391. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1239

- Singer, A. E., Ash, T., Ochotorena, C., Lorenz, K. A., Chong, K., Shreve, S. T., & Ahluwalia, S. C. (2016). A systematic review of family meeting tools in palliative and intensive care settings. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®, 33(8), 797–806. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909115594353

- Skinner, D., & Claassens, M. (2016). It’s complicated: Why do tuberculosis patients not initiate or stay adherent to treatment? A qualitative study from South Africa. BMC Infectious Diseases, 16(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-2054-5

- Sommerland, N., Wouters, E., Mitchell, E., Ngicho, M., Redwood, L., Masquillier, C., van Hoorn, R., van den Hof, S., & Van Rie, A. (2017). Evidence-based interventions to reduce tuberculosis stigma: A systematic review. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 21(11), S81–S86. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.16.0788

- Stake, R. (1995). The art of case study research. SAGE.

- Statitics Canada. (2022). Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities). Retrieved October 29, 2022, from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=9810000202&geocode=A000248.

- Tanimura, T., Jaramillo, E., Weil, D., Raviglione, M., & Lönnroth, K. (2014). Financial burden for tuberculosis patients in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. European Respiratory Journal, 43(6), 1763–1775. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00193413

- Tomás, B. A., Pell, C., Cavanillas, A. B., Solvas, J. G., Pool, R., & Roura, M. (2013). Tuberculosis in migrant populations. A systematic review of the qualitative literature. PloS one, 8(12), Article e82440. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0082440

- United Nations General Assembly. (2018). Resolution 73/3: Political declaration of the high-level meeting of the General Assembly on the fight against tuberculosis. Retrieved March 28, 2020, from https://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/73/3.

- Van Wersch, A., Bonnema, J., Prinsen, B., Pruyn, J., Wiggers, T., & van Geel, A. N. (1997). Continuity of information for breast cancer patients: The development, use and evaluation of a multidisciplinary care-protocol. Patient Education and Counseling, 30(2), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0738-3991(96)00950-0

- World Health Organization. (2014). The end TB strategy: Global strategy and targets for tuberculosis prevention, care and control after 2015. Retrieved March 28, 2020, from http://www.who.int/tb/post2015_strategy/en/.

- World Health Organization. (2021). Global tuberculosis report 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2022, from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240037021.

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). Tuberculosis profile Canada. Retrieved October 30, 2022, from: https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/tb_profiles/?_inputs_&entity_type=%22country%22&lan=%22EN%22&iso2=%22CA%22.