ABSTRACT

China has been contributing to new approaches to global governance. The Health Silk Road (HSR), a significant component of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), was proposed by China in 2016. This paper claims that HSR is a new institution introduced alongside the existing WHO-led multilateral health system, and its relationship with the existing system can be described as layering. Having explored the new development of HSR during COVID-19, this paper further argues that while HSR has its unique strength in making contributions to global health governance and economic recovery, it faces a prominent issue of securitisation in the context of China-U.S. strategic competition, suspicion of the quality of medical products and sectoral fragmentation.

Introduction

In 2015, the Chinese National Health and Family Planning Commission revealed the ‘Three-Year Plan for Belt and Road Health Exchange and Cooperation (2015–2017)’, indicating the direction for building the Health Silk Road (HSR) (CIDCA, Citation2017). In June 2016, Chinese President Xi Jinping proposed for the first time ‘working together to build the HSR’ when visiting Uzbekistan (Xinhua Net, Citation2016). During the general debate session of the 72nd World Health Assembly, Ma Xiaowei, the Minister and Secretary of the Leading Party Members’ Group of the National Health Commission of China, claimed, ‘for building the HSR and joining hands with relevant countries to address health challenges, we will continue to actively advocate and promote global health cooperation under the framework of the United Nations and WHO, and make positive contributions to seeking the health and well-being of all human beings and building a community of shared future for mankind’ (CCTV, Citation2019). This is an explicit official statement made by the Chinese government on the relationship between implementing the HSR and promoting global health governance.

At the end of 2019, the coronavirus pandemic broke out and began to spread globally. A few months later, the WHO Director-General announced the new coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) as a ‘global pandemic’ (WHO, Citation2020). On March 16, 2020, Chinese President Xi Jinping mentioned the concept of HSR in a telephone call with Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte. Xi said, ‘China stands ready to work with Italy to contribute to international pandemic cooperation and the building of the Health Silk Road’ (China Daily, Citation2020).

The HSR, proposed initially as an integral part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), has aroused scholarly attention. On the one hand, some scholars argue that the BRI is a product of China-U.S. geostrategic competition (Clarke, Citation2020; Demir, Citation2020), which has led to growing anxiety in the West about Beijing’s new geopolitical master plan to overturn the existing world order and rebuild a nascent one (Hong, Citation2017; Silvius, Citation2021). Accordingly, HSR is depicted as an initiative of China to pose a significant challenge to western-designed norms of global health governance, which has exacerbated pre-existing tensions between China and the West (Hillman & Tippett, Citation2021; Zoubir, Citation2020; Zoubir & Tran, Citation2022).

On the other hand, some other scholars contend that Beijing designs BRI to shoulder the responsibilities of a great power with no intention to replace the existing liberal order (Jones, Citation2020; Qin & Wei, Citation2018; Zheng & Zhang, Citation2016). In particular, the HSR, rather than a new geopolitical strategy within the BRI framework, is regarded as an emerging diplomatic initiative for enhancing health cooperation under the existing system (Cao, Citation2020; Tillman et al., Citation2021). Additionally, some scholars also point out that HSR is set further to advance China’s leading role in global health governance. However, it cannot fundamentally challenge U.S. leadership in health-related development assistance due to limited professional and organisational capabilities (Huang, Citation2022; Tang et al., Citation2017). These scholars thus argue that Beijing has neither the intention nor the ability to replace or overthrow the existing health governance system.

This paper contributes to the study of the HSR by further exploring its nature and impacts. We argue that the HSR is designed neither to alter the existing architecture of global health system fundamentally nor to maintain the status quo, but rather to improve the established institutions by layering gradually. We collect qualitative materials on HSR’s practices in three ways. First, we deploy HSR-related documents, research reports, and expert inquiries on HSR’s interaction with existing health systems and new developments of HSR after the outbreak of COVID-19 as qualitative data. Second, we collect data relevant to HSR’s practices and Chinese leader’s speeches from official websites (e.g. State Council of the People’s Republic of China, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Republic of Indonesia), and news reports (The Washington Post, Xinhua Net, BBC). Third, we interviewed public health authorities, staff of Chinese biopharmaceutical companies, and experts from top universities in China.Footnote1

This paper is structured as follows. First, we expound on the ‘layering’ relationship between the HSR and the existing global health governance system from the perspective of institutional change. Through tracing the development of the HSR and the interaction between China and WHO, we demonstrate that overthrowing or reinterpreting WHO-centre norms of the existing health system is not an intention of Beijing in designing and implementing HSR. Second, we analyze the contribution made by the HSR as a new institutional layer during COVID-19. In this section, we further illustrate the unique role of HSR in promoting global health governance and economic recovery and development. Finally, we examine the obstacles in the construction of the HSR. A conclusion follows by summarising the findings.

Relationship between the HSR and the existing global health governance system

There are four types of relationships between new institutions and old ones: displacement, layering, drifting, and conversion. Displacement refers to the removal of existing rules and the introduction of new ones; layering occurs when new rules are introduced on top of or alongside existing ones; drifting is present when rules remain formally the same, but their impact changes as a result of shifts in external conditions; and conversion occurs when existing rules remain the same in form but are interpreted and enacted in a new way (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010).

In the above four modes of institutional change, displacement implies that new institutions are designed to replace the old ones. With drifting, new rules remain unchanged in form but grow out of the failure of the old institution to adapt in a changing environment. With conversion, actors often actively exploit the inherent ambiguities of the old institutions for reinterpretation. In contrast to the other three types, layering is the only mode that allows for the coexistence of old and new institutions. More importantly, the new institution does not replace or reinterpret the old but is parallel to it (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010). By tracing the development of the HSR and its interaction with WHO, we can find that the HSR, different from WHO in form, is created alongside the existing WHO-led multilateral health system that is not removed, and its relationship with the existing system can be described as layering (Hanrieder, Citation2014).

Development of the HSR

Layering generally occurs when reformers cannot or do not alter core institutions because of legal lock-in and graft additional components upon the institutional core instead (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010). In the case of China, it has firmly supported WHO, which is legally empowered by member states to play a leading role in international health cooperation (State Council Information Office of the PRC, Citation2020). The HSR Initiative was also proposed by Beijing in 2016 to strengthen cooperation with the WHO and to comprehensively improve the health of people in China and countries along the Belt and Road, which is in line with the mission of WHO on ‘achieving good health for all’ (State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, Citation2017b).

To carry out such a mission, China has built multifaceted health partnerships with most countries and international organisations along the Belt and Road, emphasising strengthening international public health capacity. China has been promoting the institutionalisation of the HSR by organising several multilateral high-level forums, for example, the Silk Road Health Forum, the China-ASEAN Forum on Health Cooperation, the China-Central, and Eastern European Countries Health Ministers Forum, and the China-Arab States Health Forum (Central People’s Government of the PRC, Citation2016; Central People’s Government of the PRC, Citation2019; Cao, Citation2020). As presented in , various platforms have also been established for hospital cooperation.

Table 1. International Hospital Alliances under the HSR.

China has signed a series of bilateral cooperation agreements with HSR countries. . Cooperation with HSR countries and regions was mainly conducted in the following issues: (1) strengthening cooperation in the prevention and control of acute infectious diseases and provision of technical support; (2) strengthening infrastructure building; (3) enhancing medical personnel training; (4) promoting international cooperation in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). In concrete terms, plenty of medical teams have been sent by Beijing to provide technical assistance for controlling infectious diseases, bringing China’s experience in combating SARS and HINI influenza in 2003 and 2009, respectively (Tillman et al., Citation2021). After the Ebola outbreak, China also pledged $20 million for pandemic control along the HSR in 2017 (Tang et al., Citation2017).

Additionally, China has improved its financial capacities and skills on hard infrastructures to provide health aid projects, for instance, aiding the establishment of the Africa Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC). China has also invested nearly $4 million to train more than 930 professional medical personnel in ASEAN countries (Xinhua Net, Citation2018). Furthermore, in May 2018, Belt and Road International Medical Education Alliance (BRIMEA) was formally established to strengthen cooperation in medical personnel training in countries along the route (BRIMEA, Citation2020).

Moreover, as a unique medical diagnosis and treatment approachFootnote2, TCM has spread to 183 countries. Nearly 100,000 overseas TCM institutions have been opened in more than 30 countries so that people along the HSR could benefit from high-quality and inexpensive Chinese medicines. In addition, 86 TCM cooperation agreements have been signed with HSR countries and regions (Xinhua Net, Citation2017). In June 2018, the Chinese Traditional Medicine Foreign Exchange and Cooperation Alliance was officially established to exchange and cooperate with countries along the Belt and Road in TCM (NATCM, Citation2018).

Overall, the initial mission of the HSR was to strengthen health cooperation with Belt and Road countries under the leadership of WHO, such as organising high-level regional forums for health officials and establishing a public health network in BRI countries. In specific projects like building international hospital alliances, HSR is primarily driven by the Chinese government while allowing for the participation of social sectors like hospitals and research institutions. However, the HSR during this period was less known than other BRI projects.

After the outbreak of COVID-19, the construction of HSR was accelerated. On June 18, 2020, a Joint Statement of the High-level Video Conference on Belt and Road International Cooperation stated that HSR should be strengthened through the sharing of timely and necessary information and best practices for diagnosis and treatment of the COVID-19, the equitable access to health products, and the investment in building sound and resilient health-related infrastructures (Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China, Citation2020).

On November 24, 2020, The 3rd China-ASEAN Forum on Health Cooperation towards a Health Silk Road was held in Nanning, with an announcement to continue to support WHO’s leadership role in fighting together against the COVID-19 (China-ASEAN Panorama, Citation2021). Furthermore, on December 31, 2021, the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (SACM) formerly issued a notice on ‘Promote High-Quality Integration of Traditional Chinese Medicine into the Development Plan of Belt and Road Initiative (2021 −2025)’. In highlighting the positive role of TCM in the global fight against COVID-19, the notice sets out the main task for the next five years to share the treatment and rehabilitation programme of TCM for infectious diseases (National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2021). Apart from significant announcements or notices, the HSR has been constructed by implementing various projects, such as supplies of medical products and vaccine cooperation, which we will discuss in detail in the next section.

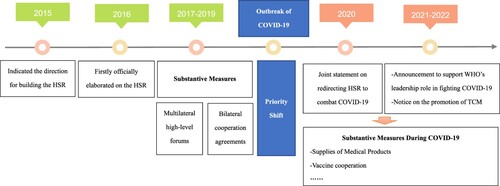

From the timeline for the development of HSR (see ), the objectives of HSR have been highly aligned with WHO to improve people’s health along the Belt and Road, shifting the focus to fighting against global infectious diseases after COVID-19.

Interaction between China and WHO

We can find support for the ‘layering’ relationship between HSR and the existing system in the interactive process between China and the WHO. Specifically, WHO’s officials are invited regularly to attend HSR-relevant seminars and meetings, such as the China-Central and Eastern Europe Countries Health Ministers’ Forum, the China-Arab Countries Health Ministers’ Forum, the BRICS Health Ministers’ Meeting, and the BRICS High-Level Meeting on Traditional Medicine (State Council Information Office of the PRC, Citation2017a).

On March 22, 2016, China and WHO jointly issued the China-WHO Country Cooperation Strategy (2016–2020) in Beijing. Beijing clearly stated that ‘the Chinese government has always attached great importance to cooperation with WHO, and China is willing to actively participate in global health with the support of WHO and work with the majority of developing countries to achieve sustainable development’ (State Council of the People’s Republic of China, Citation2016). Furthermore, the WHO affirmed its continued support for China’s active participation in global health during 2010–2012, donating $285 million to multilateral institutions (State Council of the People’s Republic of China, Citation2016; WHO, Citation2016).

On January 18, 2017, President Xi and former WHO Director-General Margaret Chan signed the Memorandum of Understanding between China and WHO on the BRI regarding health cooperation. Chan recognised China’s long-standing contributions to global health and WHO’s work and its leadership in global health governance. She expressed WHO’s willingness to strengthen cooperation with China under the BRI framework to improve the health and hygiene of countries along the Belt and Road (State Council Information Office of the PRC, Citation2017a). On May 13, 2017, China and WHO signed an action plan for cooperation (National Health Commission, Citation2017).

In addition, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the Director-General of the WHO, led a delegation to the Belt and Road High-Level Meeting for Health Cooperation in Beijing, where he stressed China’s role in global health and how future leadership can make a solid contribution to its health and the well-being of others (WHO, Citation2017a). In an article entitled ‘Building a Safe and Healthy Silk Road Together’, published in China Daily, Dr. Ghebreyesus said that ‘China can share its successful experience and best practices with other countries’ and that ‘WHO and China aim to build a safe and healthy Silk Road’ (WHO, Citation2017b).

After the outbreak of COVID-19, China deepened its cooperation with WHO. By August 2021, Beijing had provided two batches of $50 million as cash assistance to the WHO, assisted it in procuring personal protective equipment, and established a stockpile of supplies in China. Furthermore, Beijing donated through the COVID-19 Solidarity Response Fund for WHO and participated in its Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A) and COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC, Citation2022). Meanwhile, Dr. Ghebreyesus stated that the WHO should not be afraid of the increasing pluralist landscape of global health institutions, and pluralism in global health leadership strengthened the WHO (Horton, Citation2019).

The above analysis suggests that overthrowing or reinterpreting WHO-centered norms of the existing health system, neither before nor after COVID-19, is not an intention on the part of Beijing to design HSR, which does not match the theoretical modes of displacement and conversion. Besides, as a regional initiative, HSR is formerly different from WHO and thus does not match the drift model. Therefore, the relationship between HSR and the existing system is in line with what institutional change theory called ‘layering’, which occurs when new institutions are attached to existing ones (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010).

The HSR as a new institutional layer during COVID-19

The initial focus of the BRI is economic development, while infrastructure construction makes up its core. From 2013 to 2019, China invested about $730 billion in countries along the Belt and Road (Nedopil, Citation2022). Among the most critical industries that receive BRI investments are energy (about 39%) and transport (about 26%), followed by real estate (about 10%) and metals (about 7%). The HSR, in the first place, was built with a much lower profile than other BRI projects. The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, however, has led to the acceleration and expansion of the HSR.

Contributing to global health governance

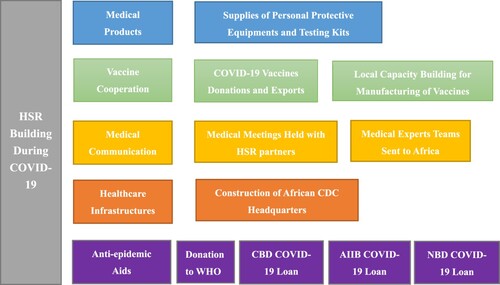

As shown in , the HSR created a new cooperation space for BRI (Zheng, Citation2021). At the 73rd session of the World Health Assembly in May 2020, President Xi promised a series of measures to help the world fight COVID-19, including providing $2 billion in assistance over two years, ensuring the security and efficiency of anti-epidemic supply chains by establishing global humanitarian response depot and hub in China in collaboration with the UN, accelerating construction of African CDC headquarters, providing Chinese-developed vaccine as a global public good, and so on(Xinhua Net, Citation2020).

Such pledges are delivered, with most medical and health assistance being provided through the HSR and BRI transportation networks. By May 2022, China has provided 4.6 billion pieces of protective clothing, 18 billion test reagents, 430 billion masks, and other anti-epidemic materials to 153 countries and 15 international organisations. In addition, as of March 2022, China-Europe freight trains have shipped 13.6 million pieces of pandemic prevention materials through 73 routes to 23 European countries, guaranteeing the stability of the global industrial chain and supply chain to fight the pandemic (State Council of the PRC, Citation2022). China-Europe freight trains have thus become a ‘lifeline’ and a ‘link of destiny’, as air and sea shipments have been blocked during the pandemic (State Council of the PRC, Citation2021b).

According to data from the Chinese government, as of July 2022, China has kept its commitment by engaging in extensive vaccine cooperation with many countriesFootnote3 and has donated and exported over 2.2 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines to more than 120 countries, most of which are HSR partners (UNICEF, Citationn.d.). China has also cooperated with HSR partners, Egypt, for example, to build its local manufacturing capability for COVID-19 vaccine production (Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China, Citation2021). Besides, Cainiao, a Chinese cross-border logistics company, has launched two controlled temperature chain flights per week with Ethiopian Airlines to export vaccines (State Post Bureau of the People’s Republic of China, Citation2020).

China and its HSR partners have held over 100 meetings to share their experience with COVID-19 prevention and control. Besides, 15 ad hoc medical expert teams and 46 Chinese medical teams have been sent to Africa to help with COVID-19 containment (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC, Citation2021a). Furthermore, in November 2021, the main building of the China-aided future headquarters for the Africa CDC also marked structural completion (Xinhua Net, Citation2021b).

Additionally, Beijing has donated $50 million to WHO and provided substantial anti-pandemic loans to HSR partners in 2020 and 2021. As presented in , China Development Bank (CDB) and the two new multilateral development banks, with China being the most important shareholder, i.e. the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the New Development Bank (NDB), provided billions of COVID-19 related loans abroad.

Table 2. COVID-19 Related Aids to HSR Partners.

When global multilateral approaches, such as WHO-led ACT-Accelerator and COVAX, have been criticised for being incompetent, multiple bilateral efforts under HSR appear to be more efficient (Huang, Citation2022). Beijing’s health assistance has received positive feedback from partner countries. According to a 2022 assessment among ASEAN countries of global partners’ vaccine support, China received a 57.8 percent positive perception score, compared with the EU’s 2.6 percent and the United States’ 23.2 percent (ASEAN Studies Centre at ISEAS—Yusof Ishak Institute, Citation2022).

Helping restore economy during the COVID-19

The emergence of COVID-19 confirms ‘how disruptive health crises can be for trade, transport, and economic activities’ (Taylor et al., Citation2020). The HSR was thus brought up again to build a community of shared future for mankind and to expand the BRI (People’s Daily, Citation2020; Wang, Citation2019). In this regard, HSR, as a pillar of the BRI, is directly linked to economic recovery and development.

At an early stage of the pandemic, countries blocking their borders, and the economies of countries and regions along the BRI have all been impacted. As early as February 25, 2020, China’s National Health Commission provided health guidance for the resumption of work and production (National Health Commission of the PRC, Citation2020). When China took the lead in containing the spread of the pandemic in March 2020, it began to actively help resume work and production in countries along the HSR. On June 17, 2020, President Xi emphasised at the Extraordinary China-Africa Summit on Solidarity Against COVID-19, the importance of ‘strengthening the joint construction of BRI, focusing on health, resumption of work and production, and improvement of people’s livelihood’ (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC, Citation2020). That marks China’s drive toward the resumption of work and economic production in countries along the BRI.

In particular, China’s HSR did have a significant impact on the resumption of production among partner countries. For example, Indonesia has procured two batches of three million doses of vaccine and one batch of 15 million semi-finished doses from China to lay the foundation for the launch of vaccination. Both countries have jointly conducted a successful Phase III clinical trial of the COVID-19 pneumonia vaccine (Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Republic of Indonesia, Citation2020). Under Beijing’s health assistance before June 2020 (), COVID-19 in Indonesia was under control, revitalising the local economy, with companies resuming work and production (Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Republic of Indonesia, Citation2020). In September 2020, the Java 7 Coal Fired Power Plant, built with Chinese investment, was brought back to service, marking the resumption of production by Chinese enterprises in Indonesia (PR Newswire, Citation2020).

Table 3. Health Assistance from China to Indonesia during COVID-19.

Also, in Brunei’s case, when it was first hit with the infection, China assisted the country in setting up an emergency testing laboratory and enterprises to improve case tracking and quarantine management (Sidek & Halim, Citation2022). As Brunei suffered the second wave of COVID-19, China further donated 100,000 doses of the Sinopharm vaccine (Kon, Citation2021). Brunei’s economy has thus recovered with Chinese health assistance. For example, as a significant project of BRI in Brunei, an oil refinery and petrochemical plant are operated by Brunei-China joint venture Hengyi Industries on Pulau Muara Besar (PMB). Despite the pandemic, this plant’s aromatics production was expanded by a suite of technologies (Brelsford, Citation2021). According to the Department of Economic Planning and Statistics (DEPS) statistics, Hengyi Industries maintained a high workload in their first full year of operations and recorded $3.5 billion in revenue in 2020, accounting for 4.48 percent of Brunei’s GDP (Wong, Citation2020).

The positive impact of HSR on the economic recovery of host countries with better political relations with China is more clearly pronounced than in other HSR countries (Yang et al., Citation2022). In addition, better political relations help China’s HSR construction in host countries. Given that bilateral relations are more friendly, the host countries tend to have a higher level of trust with China, and the HSR will be advanced more smoothly there. Also, amiable political relations and similar diplomatic stances contribute to China’s willingness to provide further support. As such, we chose the cases of Indonesia and Brunei maintaining benign relationships with China to illustrate the positive impact of HSR on the economic recovery of host countries.

With an international ‘firewall’ built by HSR against the pandemic, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said in June 2021 that since last year, the BRI cooperation has not pressed the ‘pause button’, but rather moved forward against the wind and showed strong resilience and vitality (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC, Citation2021b). As a result, in 2020, China’s trade volume of goods with BRI partners reached a record high of $1.35 trillion (Xinhua Net, Citation2021a). In 2021, China’s total import and export to countries along the BRI was up to ¥10.43 trillion, with an increase of 23.5% year-on-year (State Council of the PRC, Citation2021a).

Obstacles in the construction of the HSR

The HSR, as a new institutional layer, has contributed to global health governance and economic recovery during COVID-19 with its unique strength. Nevertheless, the construction of HSR has encountered several obstacles.

First, HSR is challenged with a prominent issue of securitisation in the context of China-U.S. strategic competition (Mao, Citation2021; Mao & Wang, Citation2021). In particular, the U.S. has been prone to adopt security-related discourses, emphasising the possible security threats from the extension of the HSR to western and recipient countries. Moreover, driven by such logic of securitisation, the U.S. has maintained a precautious attitude toward Chinese health assistance abroad, attempting to limit the influence of China’s HSR (Hillman & Tippett, Citation2021).

Since the outbreak of Covid-19, health assistance provided by Beijing through the HSR has been criticised by western media and academia about its hidden strategic and geopolitical purposes (Banerji, Citation2022; Huang, Citation2021; Karásková & Blablová, Citation2021; Kurlantzick, Citation2020; Kurtzer & Gonzales, Citation2020; Mardell, Citation2020; Pairault, Citation2021). At the beginning of the outbreak, critics noted that Beijing was using the HSR to ‘shift the story away from China as the epicenter of the pandemic’ and ‘change the Covid-19 narratives’ (Baier & Re, Citation2020; Culver & Gan, Citation2020; Rogin, Citation2020; Verma, Citation2020). Furthermore, with China’s efforts to supply more countries with medical equipment and vaccines, the HSR was further labelled as ‘Mask Diplomacy’ or ‘Vaccine Diplomacy’ of Beijing to ‘export its political system’ and ‘expand its political sphere of influence’ (Karásková & Blablová, Citation2021; Mardell, Citation2020; Rudolf, Citation2021). As such, the HSR was regarded as a tool for Beijing to seek ‘predatory’ business interests and establish itself as an ‘indispensable force’ in the global health area (Heldt, Citation2020; Sibley, Citation2020). Moreover, China’s vaccine donation was accused of reaping ‘political dividends’ by trading vaccine aid for other countries’ support of China’s core interests (Hillman & Tippett, Citation2021).

Perceiving the existential threat posed by the HSR, the U.S. has taken measures to limit the influence of Beijing in global health governance. In the early stage of COVID-19, the absence of the U.S. in providing health assistance abroad during Donald Trump’s presidency fuelled a narrative that a battered and insular U.S. cannot help lead the world out of this crisis (Poling & Hudes, Citation2021). This situation, however, changed after Joe Biden took office. In June 2021, the Biden Administration unveiled a strategy for global vaccine sharing, announcing an allocation plan for the first 25 million doses to be shared globally (The White House, Citation2021). Specifically, the United States would share 75% of these vaccines through COVAX and share 25% for the immediate need to help with surges around the world. This vaccine strategy, as a vital component of the U.S. overall global strategy to ‘re-lead’ the world to follow the U.S. value in defeating COVID-19 (Smith-Schoenwalder, Citation2021; The White House, Citation2021), has thus hedged against growing Beijing’s influence abroad via HSR (Bartlett, Citation2021). Moreover, as in Latin America, by ramping up delivery of coronavirus vaccines to the area, the U.S. attempted to curb China’s efforts to ‘wield its vaccine exports’.

Secondly, skepticism of the West towards the HSR has partially shaped the perception of countries along the HSR, damaging the HSR’s reputation. As in the case of Nigeria, part of its public showed opposition to Beijing’s health assistance through the HSR (Adebowale-Tambe, Citation2020; Asaju, Citation2020). In April 2020, the Nigerian Medical Association (NMA) rejected the federal government’s proposed invitation of an 18-member Chinese medical team to support the country in fighting against coronavirus, the reason that bringing in doctors from ‘the hotbed of the plague’ would expose Nigerian citizens to further risks (Onyeji, Citation2020). The concerns by Nigerian doctors about the arrival of a Chinese medical team also attribute to several different issues ranging from blaming China for the spread of the pandemic and perceiving Chinese medical aids as ‘hypocritical’ to growing ‘anti-Chinese sentiment’ in the country (Anadolu Agency, Citation2020; Olander, Citation2020). Although Nigerian National Orientation Agency (NOA) clarified that Chinese medical teams were only coming to share experiences (Premium Times, Citation2020), it still did not stop Nigerian doctors from opposing the invitation (Onyeji, Citation2020).

In Southeast Asian Countries, China’s vaccine donation has also been labelled as the ‘Vaccine Diplomacy’ of Beijing to achieve geopolitical goals (Anh, Citation2021b; CNA, Citation2021; Nguyen An Luong, Citation2021; Strangio, Citation2021). Although early as 2015, Vietnam announced its participation in the BRI, it is the country where actual progress in the construction of BRI is relatively slow (Hong Hiep, Citation2018). The major challenges facing the BRI in this country are Vietnamese concerns about falling into a ‘debt trap’ or being threatened by Beijing’s ‘expanding political influence’ (Van Huy, Citation2020). The distrust in China impeded the promotion of the HSR in Vietnam during COVID-19. As for Beijing’s vaccine donation, Vietnam, among Southeast Asia countries, is the most reluctant to choose the Chinese vaccines (Luong, Citation2021; Nguyen An Luong, Citation2021; Strangio, Citation2021). It was only in June 2021 that Vietnam approved the Sinopharm vaccines for emergency use (Nga, Citation2021a), while it had singled out Chinese vaccines from the vaccine procurement programme. Despite Hanoi accepting a donation of 500,000 doses of Sinopharm in June, an overwhelming majority in Vietnam said they would rather wait and pay extra money to get western vaccines (Hoang Thi Ha, Citation2021; Jennings, Citation2021). Many rejected the vaccines outright on local social media, either out of visceral anti-China attitudes or an entrenched distrust of made-in-China products (Zaini & Thi Ha, Citation2021). Vietnam thus relies primarily on western vaccines, such as AstraZeneca, Pfizer, and Moderna, in its vaccination drive (Viet Nam News, Citation2021).

Thirdly, numerous health products donated or exported by Beijing to the HSR partners, have been accused of ‘poor’ quality or ‘limited efficacy’, hampering the development of the HSR. For instance, a lot of foreign countries, including Spain, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Turkey, United Kingdom, Australia, and India, complained about ‘faulty’ coronavirus test strips and ‘counterfeit’ masks purchased from Chinese companies in the first half of 2020 (BBC, Citation2020a). Consequently, some countries, like Spain, Netherlands, Turkey, and India, have cancelled orders for Chinese test kits and masks afterward (Los Angeles Times, Citation2020).

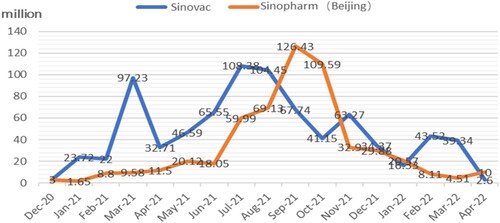

In addition, the efficacy of Sinopharm and Sinovac, the two most widely distributed Chinese vaccines in the world, has come under scrutiny since late 2021 since concerns about the protection Chinese vaccines offer against both the Delta and the Omicron variants were raised (BBC, Citation2021; Brown, Citation2022). Many countries along the HSR, such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Singapore, have thus changed their vaccine procurement plans and shifted to Pfizer vaccines (Watanabe & Takedan, Citation2022; Taylor, Citation2022). As presented in , the decline of both Sinopharm and Sinovac vaccines delivered by China through bilateral deals and donations since late 2021 has consequently been seen as the ‘fallout from these efficacy questions’ (Watanabe & Takedan, Citation2022).

Figure 3. Covid-19 Vaccines Deliveries of Sinovac and Sinopharm(Beijing) through Bilateral Deals and Donations. Source: UNICEF (Citationn.d.).

Lastly, the expansion of the HSR, particularly during COVID-19, has been achieved mainly through short-term and fragmented assistance projects for medical products or teams (Beg, Citation2020). Therefore, the challenge lies in how to build long-term and coordinated multilateral health mechanisms along the HSR in the post-epidemic era (Xin & Wen, Citation2020). In the case of China-Africa HSR, Beijing has launched various medical assistance projects to African countries, including medical team sending, material donation, infrastructure construction, and expert training (Zheng, Citation2020). Such projects, however, were generally isolated from each other without coordination. For instance, China has supported many African nations, such as Côte d'Ivoire and Mauritius, through hospital construction, but its impact on the local health system is limited (Wang et al., Citation2015). That is because, in practice, projects to support hospital construction are not well integrated with other health projects, like medical team sending or hospital-to-hospital technical cooperation, to help with the follow-up operations of target hospitals (Wang et al., Citation2017). Chinese medical teams sent to partner countries are primarily managed by the Economic and Commercial Counselor’s Office of the Chinese Embassy. At the same time, the Ministry of Commerce takes charge of the construction of local medical facilities and the donation of medical supplies (Zeng, Citation2021). Besides, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Finance are involved in health diplomacy and budget support, respectively. In the absence of an effective integration scheme for health assistance, sectoral fragmentation and divisional interests largely impede China from building a high-impact regional health initiative in the construction of the HSR (Zeng, Citation2021).

Conclusion

China’s HSR aims to supplement the existing global health governance system to improve people’s health among partner countries, leading to a layering relationship between them. Through flexible and intensive medical assistance, the HSR has shifted priority to the fight against COVID-19 with countries along the Belt and Road as a new institutional layer to the existing health system. Unlike other health-themed initiatives, the HSR also played a distinct role in helping partner countries to revitalise the economy and mitigate the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the BRI construction.

Although the HSR, with its unique advantages, has a positive impact on global health governance and economic recovery, it has encountered certain obstacles. Particularly in the context of China-U.S. strategic competition, the development of HSR has been facing a prominent issue of securitisation in the context of China-U.S. strategic competition. In addition, the distrust of several partner countries in HSR has hindered the implementation of relevant projects. Moreover, the HSR has been plagued with product quality issues and fragmentation of projects, preventing it from serving as a coordinated, institutionalised, and high-impact health initiative in the long run.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the journal’s anonymous reviewers for helpful and detailed comments on an earlier version of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We interviewed 16 actors involved in the HSR from September 2020 to April 2022, including staff members from Chinese vaccine companies Sinopharm and Sinovac, and members of the China Hospital Association, which takes charge of the China-ASEAN Hospital Cooperation Alliance. We participated in an academic conference entitled ‘Medicine and International Relations’ in October 2020. We exchanged views with Chinese officials and experts from top Chinese universities on topics such as TCM development under the framework of HSR.

2 According to an interviewee who specialises in traditional medicine,‘TCM, with a long history of 5,000 years, is the most complete, influential, and widely used traditional medical system. As a holistic approach to combining prevention, health care, treatment, and rehabilitation, TCM has attracted widespread attention […] The unique advantages of TCM lie in lower costs, a more relaxing treatment process, and reportedly fewer side effects’.

3 In the words of staff in Chinese vaccine companies whom we interviewed in September 2020: ‘Few countries have R&D capacity for COVID-19 vaccines, most of them thus depend on vaccine imports […] In the context of the global scarcity of vaccines, many countries welcome our companies to do phase 3 clinical trials for earlier access to vaccines, and we are committed to prioritising them with COVID-19 vaccines after R&D success’.

References

- Adebowale-Tambe, N. (2020, May 14). Chinese ‘doctors’ not really our guests—Health Minister. Premium Times. https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/top-news/392860-chinese-doctors-not-really-our-guests-health-minister.html.

- Anadolu Agency. (2020, June 4). COVID-19: Nigerian doctors oppose Chinese team’s visit. Anadolu Agency. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/covid-19-nigerian-doctors-oppose-chinese-teams-visit/1794073.

- Anh, V. (2021b, June 21). U.S., China vaccine diplomacy crucial but will fade away: analysts. VnExpress. https://e.vnexpress.net/news/news/us-china-vaccine-diplomacy-crucial-but-will-fade-away-analysts-4296902.html.

- Asaju, T. (2020, May 26). Covid-19 and the face of government scam. Daily Trust. https://dailytrust.com/covid-19-and-the-face-of-government-scam.

- ASEAN Studies Centre at ISEAS—Yusof Ishak Institute. (2022, February 16). The State of Sou-theast Asia: 2022 Survey Report. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/articles-commentaries/ state-of-southeast-asia-survey/the-state-of-southeast-asia-2022-survey-report/.

- Baier, B., & Re, G. (2020, April 15). Sources believe coronavirus outbreak originated in Wuhan lab as part of China’s efforts to compete with US. Fox News. https://www.foxnews.com/politics/coronavirus-wuhan-lab-china-compete-us-sources.

- Banerji, A. (May 15, 2022). Health Silk Route: China and the Middle East. Modern Diplomacy. https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2022/05/15/health-silk-route-china-and-the-middle-east/.

- Bartlett, J. (2021, June 9). Why Biden should extend vaccine diplomacy to sanctioned states like Venezuela, Iran, and North Korea. Center for A New American Security. https://www.cnas.org/publications/commentary/why-biden-should-extend-vaccine-diplomacy-to-sanctioned-states-like-venezuela-iran-and-north-korea.

- BBC. (2020, April 28). Coronavirus: India cancels order for ‘faulty’ China rapid test kits. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-52451455.

- BBC. (2021, July 19). Covid: Is China’s vaccine success waning in Asia? BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-57845644.

- Beg, Z. (2020, April 29). The ‘health silk road’: Implications for the EU under COVID-19. European Institute for Asian Studies. https://eias.org/publications/op-ed/the-health-silk-road-implications-for-the-eu-under-covid-19/.

- Brelsford, R. (2021, February 25). Hengyi lets contract for aromatics expansion at Brunei comp-lex. Honeywell. https://uop.honeywell.com/en/news-events/2021/february/hengyi-industries-selects-honeywell-technology-for-brunei-petrochemical-complex.

- BRIMEA (Belt and Road International Medical Education Alliance). (2020, September 1). Brief Introduction of the BRIMEA. https://www.cmu.edu.cn/brimea/info/1886/1201.htm.

- Brown, S. (January 2022). The waning efficacy of China’s vaccines presents a ‘smart power’ opp-ortunity for the West. British Foreign Policy Group. https://bfpg.co.uk/2022/01/vaccine-efficacy-china-smart-power/.

- Cao, J. (2020). Toward a health silk road: China’s proposal for global health cooperation. China Quarterly of International Strategic Studies, 6(01), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1142/S2377740020500013

- CCTV (China Central Television). (2019, May 21). 打造“健康丝绸之路” 携手应对健康挑战 [Building ‘Healthy Silk Road’ to Address Health Challenges Together]. CCTV. http://jiankang.cctv.com/2019/05/21/ARTI3mFcZ9BtimtsAqRS89c5190521.shtml.

- Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. (2016, October 29). 首届中国—东盟卫生合作论坛在广西南宁市成功召开 [The first China-ASEAN Forum on Health Cooperation was successfully held in Nanning, Guangxi]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-10/29/content_5125850.htm.

- Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. (2019, August 16). 第二届中阿卫生合作论坛在京举办 [The Second China-Arab Health Forum held in Beijing]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019-08/16/content_5421752.htm.

- Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. (2021, July 8). 世卫组织驻埃及代表赞赏中埃合作生产首批新冠疫苗 [WHO Representative in Egypt Applauds Sino-Egyptian Collaboration in Production of First New Crown Vaccine]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-07/08/content_5623670.htm.

- China-ASEAN Panorama. (2021). China-ASEAN is responsible for strengthen health cooperation under the epidemic. http://en.china-asean-media.com/show-45- 1047-1.html.

- China Daily. (2020, March 19). Word of the day—Health Silk Road. China Daily. https://cn.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202003/19/WS5e72d248a3107bb6b57a773c.html.

- CIDCA (China International Cooperation and Development Agency). (2017, August 16). Healthy Silk Road: to benefit people’s livelihoods. http://www.cidca.gov.cn/2017-08/16/c_129972358.htm.

- Clarke, M. (2020). Beijing’s pivot west: The convergence of innenpolitik and aussenpolitik on China’s ‘belt and road’? Journal of Contemporary China, 29(123), 336–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2019.1645485

- CNA. (2021 July 13). Commentary: Vietnam’s attitude towards Chinese vaccines is very telling. CNA. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/commentary/commentary-vietnams-attitude-towards-chinese-vaccines-very-telling-2022376.

- Culver, D., & Gan, N. (2020, December 1). China coronavirus vaccine diplomacy. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/12/01/asia/china-coronavirus-vaccine-diplomacy-intl-hnk/index.html.

- Demir, E. (2020). Competing regional visions China’s: Belt and road initiative versus the indo-pacific partnership. In A. Rossiter, & B. J. Cannon (Eds.), Conflict and cooperation in the indo-pacific: New geopolitical realities (pp. 94–114). Routledge.

- Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Republic of Indonesia. (2020). 抗击新冠肺炎疫情 [Combating COVID-19 Pneumonia: Important Notice]. Retrieved 1 May, 2022. http://id.china-embassy.org/chn/ztbd/xxxdddd/default_1.htm.

- Hanrieder, T. (2014). Gradual change in international organisations: Agency theory and historical institutionalism. Politics, 34(4), 324–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9256.12050

- Heldt, E. C. (2020, December 9). China’s ‘Health Silk Road’ offensive: how the West should re-spond. Global Policy. https://mediatum.ub.tum.de/1584296.

- Hillman, J., & Tippett, A. (2021). A robust U.S. response to China’s health diplomacy will reap domestic and global benefits. Think Global Health. https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/robust-us-response-chinas-health-diplomacy-will-reap-domestic-and-global-benefits.

- Hoang Thi Ha. (2021, July 12). A tale of two vaccines in Vietnam.ISEAS—Yusof Ishak Institute. https://fulcrum.sg/a-tale-of-two-vaccines-in-vietnam.

- Hong, Y. (2017). Motivation behind China’s ‘One belt, One road’ initiatives and establishment of the Asian infrastructure investment bank. Journal of Contemporary China, 26(105), 353–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2016.1245894

- Hong Hiep, L. (2018). The Belt and Road Initiative in Vietnam: challenges and prospects. ISEAS—Yusof Ishak Institute. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/articles-commentaries/ iseas-perspective.

- Horton, R. (2019). Offline: WHO powers up in 2019. The Lancet, 393(10166), 14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30004-2.

- Huang, Y. (2022). The health silk road: How China adapts the belt and road initiative to the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Public Health, 112(4), 567–569. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2021.306647

- Huang, Y. Z. (2021, March 11). Vaccine diplomacy is paying off for China. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2021-03-11/vaccine-diplomacy-paying-china.

- Jennings, R. (2021, September 18). China’s COVID-19 vaccine diplomacy reaches 100-plus countries. VOA. https://www.voanews.com/a/china-s-covid-19-vaccine-diplomacy-reaches-100-plus-countries/6233766.html.

- Jones, L. (2020). Does China’s belt and road initiative challenge the liberal, rules-based order? Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences, 13(1), 113–133. doi:10.1007/s40647-019-00252-8

- Karásková, I., & Blablová, V. (March 2021). The logic of china’s vaccine diplomacy. The Diplo-mat. https://thediplomat.com/2021/03/the-logic-of-chinas-vaccine-diplomacy/.

- Kon, J. (2021, August 22). China reaffirms its commitment to help Brunei fight COVID-19. Borneo Bulletin. https://borneobulletin.com.bn/china-reaffirms-its-commitment-to-help-brunei-fight-covid-19/.

- Kurlantzick, J. (2020, May 21). China uses the pandemic to claim global leadership. The Washi-ngton Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/china-uses-the-pandemic-to-claim-global-leadership/2020/05/21/9b045692-9ab4-11ea-ac72-3841fcc9b35f_story.html.

- Kurtzer, J., & Gonzales, G. (2020, November 17). Humanitarian agenda: China’s humanitarian Aid: Cooperation amidst competition. Center for Strategic & International Studies. https://www.csis.org/analysis/ chinas-humanitarian-aid-cooperation-amidst-competition.

- Los Angeles Times. (2020, April 10). Faulty masks. Flawed tests. China's quality control problem in leading global COVID-19 fight. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2020-04-10/china-beijing-supply-world-coronavirus-fight-quality-control

- Luong, D. (2021, March 27). Vietnam proves immune to China’s vaccine diplomacy campaign. Nikkei Asia. https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/Vietnam-proves-immune-to-China-s-vaccine-diplomacy-campaign.

- Mahoney, J., & Thelen, K. (2010). A theory of gradual institutional change. In J. Mahoney, & K. Thelen (Eds.), Explaining institutional change: Ambiguity, agency, and power (pp. 1–37). Cambridge University Press.

- Mao, W. Z. (2021). 发展——安全互动中的全球基础设施议题 [global infrastructure issue in the ‘development-security’ nexus]. International Security Studies, 39((05|5)), 92–118. https://doi.org/10.14093/j.cnki.cn10-1132/d.2021.05.004

- Mao, W. Z., & Wang, Q. L. (2021). 大变局下的中美人文交流安全化逻辑 [study on securitization of people-to-people exchange between China and U.S. In momentous changes]. Global Review, 05, 34–55. https://doi.org/10.13851/j.cnki.gjzw.202106003

- Mardell, J. (2020, November 24). China’s vaccine diplomacy assumes geopolitical importance. Mercator Institute for China Studies. https://merics.org/en/short- analysis/chinas-vaccine-diplomacy-assumes-geopolitical-importance.

- Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China. (2020, June 18). “一带一路”国际合作高级别视频会议联合声明 [Joint statement of the high-level video conference on ‘Belt and Road’ international cooperation]. http://policy.mofcom.gov.cn/pact/pactContent.shtml?id=3293.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. (2020, June 17). 习近平在中非团结抗疫特别峰会上的主旨讲话 [Xi Jinping’s keynote speech at the extraordinary China-Africa Summit on solidarity against COVID-19]. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/zyxw/t1789549.shtml.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. (2021a, May 21). 习近平在全球健康峰会上的讲话 [Xi Jinping’s Speech at the Global Health Summit]. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/zyxw/t1877663.shtml.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. (2021b, June 24). 面对疫情,“一带一路”的合作并没有按下“暂停键” [In the face of the epidemic, the ‘Belt and Road’ coopera-tion did not press the ‘pause button’]. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/wjdt_674879/wjbxw_674885/202106/t20210624_9176977.shtml.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. (2022, May 13). 外交部发言人举行例行记者发布会 [Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian hosts regular press conference]. https://www.mfa.gov.cn/web/fyrbt_673021/jzhsl_673025/202205/t20220513_10685849.shtml.

- NATCM (National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine). (2018, July 12). Chinese Traditional Medicine Foreign Exchange and Cooperation Alliance was established. http://www.satcm.gov.cn/xinxifabu/gedidongtai/2018-07-02/7265.html.

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. (2017, May 16). China’s health department and WHO enhance cooperation. http://en.nhc.gov.cn/2017-05/16/c_71642.htm.

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. (2020, February 25). Resumption of work and production is imminent, how to ‘safely’ startwork. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/kpzs/202002/af330c0037ad49f8a50d6a58b17f307d.shtml.

- Nedopil, C. (2022). Investments in the belt and road initiative. Green Finance & Development Center, FISF Fudan University. www.greenfdc.org.

- Nga, L. (2021a, June 3). Vietnam approves Sinopharm Covid vaccine for emergency use. VnEx-press. https://e.vnexpress.net/news/news/vietnam-approves-sinopharm-covid-vaccine-for-emergency-use-4288933.html.

- Nguyen An Luong, D. (2021, May 20). Vietnam may not want China’s Covid-19 vaccines, but how long can it stay immune to them? South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/ week-asia/opinion/article/3134085/vietnam-may-not-want-chinas-covid-19-vaccines-how-long-can-it.

- Olander, E. (2020, April 6). Coronavirus aid: Chinese medical teams arrive in Africa to mixed reactions. The Africa Report. https://www.theafricareport.com/25746/coronavirus-aid- chinese-medical-teams-arrive-in-africa-to-mixed-reactions/.

- Onyeji, E. (2020, April 6). Coronavirus: Nigerian doctors reject country’s plan to invite Chinese medical team. Premium Times. https://www.premiumtimesng.com/health/health-news/386163-coronavirus-nigerian-doctors-reject-countrys-plan-to-invite-chinese-medical-team.html.

- Pairault, T. (2021, August 11). China’s presence in africa is at heart political. The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2021/08/chinas-presence-in-africa-is-at-heart-political/.

- People’s Daily. (2020, December 12). 疫苗也搞“美国优先” [Vaccines also engage in ‘America First’]. People’s Daily. http://world.people.com.cn/n1/2020/1212/c1002-31963991.html.

- Poling, G., & Hudes, S. (2021, January 28). Vaccine diplomacy is Biden’s first test in South East Asia. Center for Strategic & International Studies. https://www.csis.org/analysis/vaccine-diplomacy-bidens -first-test-southeast-asia.

- Premium Times. (2020, April 4). COVID-19: Why Chinese doctors are coming to Nigeria. Premium Times. https://www.premiumtimesng.com/coronavirus/385950-covid-19-why-chinese-doctors-are-coming-to-nigeria-official.html.

- PR Newswire. (2020, October16). A Megawatt unit of Indonesia java No.7 coal-fired power generation project fully put into operation. PR Newswire. https://en.prnasia.com/releases/apac/a-megawatt-unit-of-indonesia-java-no-7-coal-fired-power-generation-project-fully-put-into-operation-295032.shtml.

- Qin, Y. Q., & Wei, L. (2018). New global governance concept and the practice of ‘belt and road’ cooperation. Diplomatic Review, 02, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.13569/j.cnki.far.2018.02.001

- Rogin, J. (2020, April 4). State Department Cables warned safety issues Wuhan lab studying bat coronaviruses. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/04/14/state-department-cables-warned-safety-issues-wuhan-lab-studying-bat-coronaviruses/.

- Rudolf, M. (2021, January 26). China’s health diplomacy during COVID-19. German Institute for International and Security Affairs. https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/publication/chinas -health-diplomacy-during-covid-19.

- Sibley, N. (2020, March 20). Failure toconfront corruption will exacerbate coronavirus crisis.https://www.hudson.org/research/15846-failure-to-confront-china-s-corruption-will-exacerbate-coronavirus-crisis.

- Sidek, R., & Halim, N. (2022). China’s vaccine diplomacy in Brunei: boon or bane? The Diplo-mat. https://thediplomat.com/2022/01/chinas-vaccine-diplomacy-in-brunei-boon-or-bane/.

- Silvius, R. (2021). China’s belt and road initiative as nascent world order structure and concept? Between sino-centering and sino-deflecting. Journal of Contemporary China, 30(128), 314–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2020.1790905

- Smith-Schoenwalder, C. (2021, May 17). Biden: US to share more coronavirus vaccine supply than Russia China. U.S. News. https://www.usnews.com/news/national-news/articles/2021-05-17/biden-us-to-share-more-coronavirus-vaccine-supply-than-russia-china.

- State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China. (2017a, January 19). 习近平欢迎世界卫生组织共建“健康丝绸之路” [Xi Jinping: China welcomes WHO to joint construction of ‘Health Silk Road’]. http://www.scio.gov.cn/31773 /35507/gcyl35511/Document/1540574/1540574.htm.

- State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China. (2017b, January 19). “健康丝绸之路”未来光明 [Healthy Silk Road’ has a bright future]. http://www.scio.gov.cn/31773/35507/35510/35524/ Document/1540561/1540561.htm.

- State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China. (2020, June 7). 抗击新冠肺炎疫情的中国行动 [Fighting Covid-19 China in action]. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2020-06/07/content_5517737.htm.

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. (2016, March 24). 《中国—世界卫生组织国家合作战略 (2016-2020)》在京签署 [China-WHO Country Cooperation Strategy (2016-2020) signed and released in Beijing]. http://www.gov.cn/guowuyuan/vom/2016-03/24/content_5057354.htm.

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. (2017, April 24). 共谋健康福祉 中国-中东欧国家医院合作联盟推动多领域合作 [Seeking health and well-being together china-central and eastern European countries hospital cooperation alliance promotes multi-field cooperation]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2017-04/24/content_5188650.htm.

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. (2021a, January 25). 高质量共建“一带一路”成效显著 [High-quality joint construction of the Belt and Road has achieved remarkable results]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-01/25/content_5670280.htm.

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. (2021b, August 1). 中国对外援助和出口新冠疫苗数量超过其他国家总和——让疫苗成为全球公共产品,中国做到了![China’s foreign aid and exports of Covid-19 vaccines exceed the total does of other countries——making vaccines a global public good, China does it]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-08/01/content_5628795.htm.

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. (2022, May 2). 中欧班列 畅通中外商贸往来 [China-Europe Class Train Smooth trade and commerce between China and abroad]. http://www. gov.cn/ xinwen/2022-05/02/content_5688414.htm.

- State Post Bureau of the People’s Republic of China. (2020, December 3). 菜鸟与埃塞俄比亚航空开通温控药品空运专线 [Cainiao and Ethiopian airlines open special airfreight line for temperature-controlled medicines].http://www.spb.gov.cn/xw/xydt/202012/t20201203_3593967.html.

- Strangio, S. (2021, June 9). Vietnam approves Chinese covid-19 vaccine, reluctantly. The Diplo-mat. https://thediplomat.com/2021/06/vietnam-approves-chinese-covid-19-vaccine-reluctantly/.

- Tang, K., Li, Z., Li, W., & Chen, L. (2017). China’s silk road and global health. The Lancet, 390(10112), 2595–2601. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32898-2

- Taylor, A. (2022, Jan 11). Beijing and Moscow are losing the vaccine diplomacy battle. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/01/11/china-russia-omicron-vaccine/.

- Taylor, A. L., Habibi, R., Burci, G. L., Dagron, S., Eccleston-Turner, M., Gostin , L. O., Meier, B. M., Phelan, A., Villarreal, P. A., Yamin, A. E., Chirwa, D., Forman, L., Ooms, G., Sekalala, S., & Hoffman, S. J. (2020). Solidarity in the wake of COVID-19: Reimagining the international health regulations. The Lancet, 396(10244), 83. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31417-3

- The White House. (2021, June 3). Biden-Harris administration unveils strategy for global vacci-ne sharing, announcing allocation plan for the first 25 million doses to be shared globally. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/06/03/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration-unveils-strategy-for-global-vaccine-sharing-announcing-allocation-plan-for-the-first-25-million-doses-to-be-shared-globally/.

- Tillman, H., Ye, Y., & Jian, Y. (2021). Health silk road 2020: A bridge to the future of health for all. Shanghai Institutes for International Studies. http://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3830380.

- UNICEF. (n.d.). COVID-19 Market Dashboard. Retrieved 1 May, 2022. https://www.unicef.org/supply/covid-19-vaccine-market-dashboard.

- Van Huy, D. (2020). A Vietnamese perspective on China’s belt and road initiative in Vietnam. Contemporary Chinese Political Economy and Strategic Relations, 6(1), 145–VIII. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2436132124?pq-origsite=gscholar& fromopenview = true.

- Verma, R. (2020). China’s ‘mask diplomacy’ to change the COVID-19 narrative in Europe. Asia Europe Journal, 18(2), 205–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-020-00576-1

- Viet Nam News. (2021, August 10). HCM City clarifies Sinopharm COVID-19 vaccine deal, may donate some to other localities. Viet Nam News. https://vietnamnews.vn/society/1008125/hcm-city-clarifies-sinopharm-covid-19-vaccine-deal-may-donate-some-to-other-localities.html.

- Wang, J. (2019). Xi jinping’s ‘major country diplomacy’: A paradigm shift? Journal of Contemporary China, 28(115), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2018.1497907

- Wang, Y. P., Jin, N., & Pan, X. D. (2017). 中国对外援助医疗卫生机构的历史、现状与发展趋势 [history, current situation and trend of China’s overseas health facilities aid]. Chinese Journal of Health Policy, 10(8), 60–67. http://journal.healthpolicy.cn/html/20170812.htm

- Wang, Y. P., Liang, W. J., Yang, H. W., Cao, G., Pan, X.D., Jin, N., & Wang, X. (2015). 中国卫生发展援助的理念与实践 [ideology and practice of development assistance for health in China]. Chinese Journal of Health Policy, 8(5), 37–43. http://www.cqvip.com/qk/89515x/201505/665126410.html

- Watanabe, S., & Takedan, K. (2022, May 8). China’s vaccine diplomacy spoiled by omicron variant. Nikkei Asia. https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Coronavirus/COVID-vaccines/China-s-vaccine-diplomacy-spoiled-by-omicron-variant.

- WHO. (2016). China-WHO country cooperation strategy.viii. https://iris.wpro.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665.1/13117/WPRO_2016_DPM_003_chi.pdf.

- WHO. (2017a, August 15). Director-General leads WHO delegation to the Belt and Road Forum for Health Cooperation. https://apps.who.int/mediacentre/news/ notes/2017/who-delegation-belt-and-road/en/index.html.

- WHO. (2017b, August 17). China can help WHO improve global health. https://apps.who.int/mediacentre/commentaries/healthy-silk-road/en/.

- WHO. (2020, March 11). WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director- general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on- covid-19 - 11-march-2020.

- Wong, A. (2020, January 16). Hengyi Industries records US$3.5 billion revenue in 2020. Biz Brunei. https://www.bizbrunei.com/2021/01/hengyi-industries-records-us3-5-billion-revenue-in-2020.

- Xin, Q., & Wen, S. B. (2020). 健康丝路”视角下的中国与全球卫生治理 [China and global health governance in the perspective of ‘health silk road’]. Modern International Relations, 6, 19–27. http://www.cqvip.com/qk/81437x/202006/7102448520.html

- Xinhua Net. (2016, June 27). “Belt and Road Initiative”:growing in cooperation—Notes on Pres-ident Xi Jinping’s visit to Uzbekistan and attendance at the Tashkent Summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Xinhua Net. http://www.xinhuanet.com//world/2016-06/27/c_ 1119118742.htm.

- Xinhua Net. (2017, February 24). The effectiveness of building a ‘Healthy Silk Road’ is beginning to show. Xinhua Net. https://www.imsilkroad.com/news/p/12848.html.

- Xinhua Net. (2018, September 20). China-ASEAN establishes hospital cooperation alliance and proposes five health cooperation initiatives. Xinhua Net. http://www.xinhuanet.com/2018-09/20/c1123461984.htm.

- Xinhua Net. (2020, May 18). China announces concrete measures to boost global fight against COVID-19 as Xi addresses WHA session. Xinhua Net. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/ 2020-05/18/c_139067269.htm.

- Xinhua Net. (2021a, June 24). Wang Yi: Encountered the Pandemic, BRI cooperation fail to press ‘pause button’, but moves forward against the wind. Xinhua Net. http://www.xinhuanet.com/silkroad/ 2021-06/24/c1127592318.htm.

- Xinhua Net. (2021b, November 27). China-aided Africa CDC Headquarters main building marks structural completion. Xinhua Net. http://www.news.cn/english/2021-11/27/c_1310337402.htm.

- Yang, Z. L., Chen, C., & Yang, J. X. (2022). 一带一路”倡议与东道国的国家治理 [The conditional impact of the belt and road initiative on national governance]. World Economics and Politics, 3, 4–29. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-SJJZ202203001.htm

- Zaini, K., & Thi Ha, H. (2021). Understanding the selective hesitancy towards Chinese vaccines in Southeast Asia. ASEAN Studies Centre at ISEAS—Yusof Ishak Institute. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/articles-commentaries/iseas-perspective/2021-115-understanding-the-selective-hesitancy-towards-chinese-vaccines-in-southeast-asia-by-khairulanwar-zaini-and-hoang-thi-ha/.

- Zeng, A. P. (2021). China-Africa health silk road: Practices, challenges and solutions. China In-Ternational Studies, 87, 111–131. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/chintersd87&div=9&id=&page=

- Zheng, D. (2021, December 2). 加快共建健康丝绸之路步伐 [Accelerate the pace of jointly building the Health Silk Road]. http://www.qstheory.cn/llwx/2020-09/11/c_1126481118.htm.

- Zheng, Y. (2020, October 15). Analyzing China’s health assistance to Africa with data. https://www.yicai.com/news/100800644.html.

- Zheng, Y. N., & Zhang, C. (2016). Belt and road’ and China’s grand diplomacy. Contemporary World, 2, 28–11. https://doi.org/10.19422/j.cnki.ddsj.2016.02.003

- Zoubir, Y. H. (2020). China’s ‘health silk road’ diplomacy in the MENA. Med Dialogue Series, 27, 1–17. https://www.kas.de/documents/282499/282548/MDS_China(Health(Silk(Road(Diplomacy.pdf.

- Zoubir, Y. H., & Tran, E. (2022). China’s health silk road in the Middle East and north Africa amidst COVID-19 and a contested world order. Journal of Contemporary China, 31(135), 335–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2021.1966894