ABSTRACT

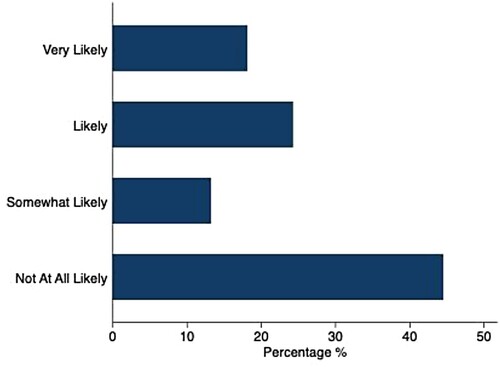

Scant studies have explored COVID-19 vaccine acceptability among refugees. However, contexts of forced migration may elevate COVID-19 vulnerabilities, and suboptimal refugee immunisation rates are reported for other vaccine-preventable diseases. We conducted a multi-methods study to describe COVID-19 vaccine acceptability among urban refugee youth in Kampala, Uganda. This study uses cross-sectional survey data from a cohort study with refugees aged 16–24 in Kampala to examine socio-demographic factors associated with vaccine acceptability. A purposively sampled cohort subset (n = 24) participated in semi-structured in-depth individual interviews, as did key informants (n = 6), to explore COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. Among 326 survey participants (mean age: 19.9; standard deviation 2.4; 50.0% cisgender women), vaccine acceptance was low (18.1% reported they were very likely to accept an effective COVID-19 vaccine). In multivariable models, vaccine acceptance likelihood was significantly associated with age and country of origin. Qualitative findings highlighted COVID-19 vaccine acceptability barriers and facilitators spanning social-ecological levels, including fear of side effects and mistrust (individual level), misinformed healthcare, community and family attitudes (community level), tailored COVID-19 services for refugees (organisational and practice setting), and political support for vaccines (policy environment). These data signal the urgent need to address social-ecological factors shaping COVID-19 vaccine acceptability among Kampala’s young urban refugees.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04631367.

Introduction

High population acceptability and uptake of COVID-19 vaccines is necessary to control local epidemics (Yunus et al., Citation2020). Understanding barriers to vaccine and booster uptake in low and middle-income countries (LMIC) will be instrumental to achieving optimal vaccination coverage. Constrained access to vaccines, inequitable healthcare access, and contextually varying national vaccine distribution strategies – particularly with respect to refugee inclusion – are barriers to expanding LMIC vaccine coverage (Thomas et al., Citation2021). For instance, Uganda is sub-Saharan Africa’s largest refugee hosting nation and only 31% of the general population were fully vaccinated as of July 2022 (IHME, Citation2022). Vaccine equity encompasses distribution within cities, between urban and rural divides, and across countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) has historically reported suboptimal immunisation rates among refugees for other vaccine-preventable diseases due to restricted vaccination supply, healthcare access barriers, and vaccine hesitancy (Citation2019). Thus, refugee COVID-19 vaccine acceptability is a key consideration for health systems. While global research signals widely varying COVID-19 vaccine acceptability, there is limited disaggregated data for refugee populations (Bono et al., Citation2021; Lazarus et al., Citation2021; Sallam, Citation2021; Solís Arce et al., Citation2021).

Refugees may be at increased risk of acquiring COVID-19 due to vulnerabilities associated with forced migration, including population dense living environments, precarious employment, and exclusion from national health systems (Kluge et al., Citation2020; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Citation2020; Singh et al., Citation2020). Refugees may also experience barriers to sustained engagement in COVID-19 prevention practices such as physical distancing, hand washing, and consistent face mask use (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2021) due to crowded living conditions, and insufficient access to water and soap (Claude et al., Citation2020). In addition, emerging evidence indicates that refugees may have low COVID-19 health literacy that could reduce vaccine acceptability (Clarke et al., Citation2021).

The majority of refugee and displaced persons (>80%) live in LMIC, yet there is limited knowledge of refugee vaccine acceptability in LMIC (UNHCR, Citation2020). In a systematic review with refugee and displaced women and children in conflict-affected locations, vaccines for other infectious diseases (e.g. polio, measles) were largely administered within camp settlements rather than outside of these contexts (Meteke et al., Citation2020). Barriers to vaccine acceptability among these populations included limited vaccination supplies, vaccine-related stigma, and mistrust, while facilitators to vaccine acceptability included community engagement and outreach (Meteke et al., Citation2020). A study with Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh noted low coverage of rubella, diphtheria, and tetanus vaccination among child refugees despite immunisation campaigns, and that vaccination was lower for some vaccines and age groups in informal settlements compared to refugee camps (Feldstein et al., Citation2020).

Uganda, Sub-Saharan Africa’s largest refugee hosting nation with more than 1.5 million refugees, is a key context to understand vaccine acceptability among refugees to prepare for COVID-19 vaccination and booster roll-out (UNHCR, Citation2021), in addition to emerging vaccines (e.g. malaria). A study assessing COVID-19 vaccine acceptance across ten LMICs, including Uganda, reported a high mean acceptability among LMIC (mean 80.3%), and included studies in Uganda with rural women (85.8% acceptability), and the general urban population in Kampala (76.5% acceptability) (Solís Arce et al., Citation2021). Motivations for COVID-19 vaccination in these studies included self and family-protection, while the most common reasons for not wanting the vaccine included side effect and vaccine efficacy concerns (Solís Arce et al., Citation2021). Uptake, however, remains much lower than this reported acceptability, with 40% having received at least one dose, and only 31% fully vaccinated (IHME, Citation2022).

Globally most refugee and displaced persons live in urban regions (UNHCR, Citation2021) yet there is a dearth of research exploring COVID-19 vaccine acceptability with urban refugees (Claude et al., Citation2020). As of May 2022, in Kampala, Uganda, there were nearly 116,000 urban refugees or displaced persons, and over a quarter (27%) of this population were aged 15–24 (UNHCR, Citation2022). The presence of unique vulnerabilities among urban refugees in Uganda, who often live in informal settlements, such as slums (Sabila & Silver, Citation2020), signals the need to understand attitudes regarding COVID-19 vaccination among this population.

The social-ecological research framework has been applied to better understand vaccine acceptability, in contexts such as the United States (US) (Kumar et al., Citation2012), and among population groups that experience social marginalisation, such as men who have sex with men (Nadarzynski et al., Citation2021). Social-ecological frameworks explore the interactions between environmental factors spanning multiple levels – from individual to policy – that shape health care access, engagement, and ultimately health outcomes (McLeroy et al., Citation1988). For instance, multi-level domains salient to vaccine acceptability include individual (e.g. vaccine beliefs), community (e.g. social norms regarding vaccination), organisational and practice (e.g. healthcare delivery approaches for affected communities), and policy (e.g. political support and/or mandates for vaccines) factors (Kumar et al., Citation2012; Nadarzynski et al., Citation2021). The social-ecological model offers the potential to explore multi-level factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptability among young refugees age 16-24, as it has been applied to understand other health concerns, such as sexual and gender-based violence with this population (Logie et al., Citation2019). To address research gaps regarding COVID-19 vaccine acceptability among young urban refugees, we conducted a multi-methods study informed by the social-ecological model (Mcleroy et al., Citation1988) to investigate COVID-19 vaccine acceptability among young urban refugees ages 16–24 living in Kampala, Uganda. Research findings aim to inform tailored and responsive refugee vaccine distribution campaigns.

Methods

Study design

Leveraging an existing cohort of urban refugees (age 16-24) living in Kampala (the Tushirikiane cohort) (Logie et al., Citation2021), we conducted the community-based Kukaa Salama (roughly translated from Swahili to ‘staying safe’) multi-methods study focused on COVID-19 prevention, including a focus in this manuscript on investigating COVID-19 vaccine acceptability Detailed study procedures have been described elsewhere (Logie et al., Citation2021). In brief, data were derived from a cross-sectional module with study participants in Kampala on the feasibility and effectiveness of a mobile health intervention for COVID-19 prevention, that was nested in a larger HIV self-testing study. Participants completed questionnaires on topics such as HIV stigma, depression, self-efficacy, condom use, among others, at three time points within a 12-month study period. A questionnaire on COVID-19 attitudes was added to this study at time three (December 2020). Refugees aged 16–24 years were eligible for study inclusion if they lived in one of five informal settlements in Kampala (Kabalagala, Kansanga, Katwe, Nsambya, Rubaga), spoke one of the study languages (English, French, Swahili, Luganda, Kinyarwanda, Kirundi), and had access to a mobile phone. Participants were recruited through purposive sampling methods (Creswell, Citation2013), specifically we conducted peer-driven recruitment by refugee youth peer navigators as well as venue-based recruitment from a refugee youth community-based agency that was the collaborating partner. Urban refugees (age 16-24) and key informants who provide services in Kampala also completed in-depth interviews regarding COVID-19 experiences, including perspectives on vaccination. Here, we report on two main components: cross-sectional survey data (December 2020) and qualitative interviews (March 2021).

Participants and data collection

Data on general health outcomes and socio-demographics were collected in person using structured questionnaires on tablets, which were administered by trained research assistants. A cross-sectional module on COVID-19 attitudes was added to the survey in December 2020. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance was assessed using a single item 4-point Likert scale question (not at all likely, somewhat likely, likely, very likely) on acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine with demonstrated effectiveness and availability. This item was used in other studies of COVID-19 vaccine acceptability (Lazarus et al., Citation2021). Interviews were conducted in all study languages and data were recorded on tablets using SurveyCTO (Dobility, Cambridge, USA).

A subset of the refugee cohort (n = 24) was invited to participate in semi-structured in-depth individual interviews. Young people were purposively recruited to achieve an equal gender distribution, and representation by age and country of birth to the full cohort. Additionally, key informants (KI) (n = 6), professionals in various roles (e.g. refugee youth services, refugee sex work services, ministries of health and education) supporting refugee youth wellbeing in Kampala were purposively sampled for interviews. Using a semi-structured interview guide, refugees (age 16-24) and KI were asked about various aspects of COVID-19 such as differences in their lives during COVID-19 (e.g. economic security, sexual and reproductive healthcare access). This current analysis focuses on a semi-structured interview question specifically regarding COVID-19 vaccine knowledge and acceptance: ‘How likely are you to take a COVID-19 vaccine when it is available in Uganda?’ Following this question, participants were provided with additional prompts, which included further discussion about the participant’s knowledge of the COVID-19 vaccine, reasoning behind vaccine attitudes, and where participants receive their information about the COVID-19 vaccine. All interviews were recorded, transcribed, and translated verbatim to English.

Data analysis

Our quantitative analytic sample included all participants who responded to the module’s COVID-19 vaccine acceptance question. We described participants in terms of socio-demographic characteristics and explored differences in sentiment towards COVID-19 vaccine acceptance between groups using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables, and t-test or ANOVA for continuous variables. Vaccine acceptance was defined as responding ‘very likely’ to the single-item question. Crude odds ratios (ORs) were calculated for vaccine acceptance by each socio-demographic factor using logistic regression, controlling for settlement a priori to account for the clustered sampling design. In a multivariable model, settlement and gender, which were determined a priori, as well as all significant crude demographic factors were carried forward as potential covariates to obtain adjusted ORs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Analyses were conducted in Stata 16.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Coding of the qualitative data was conducted using Dedoose (SocioCultural Research Consultants, LA, USA) to enable group coding and collaboration (Dedoose, Citation2016). All 30 transcripts were coded by three members of the research team. Once coding was completed, one team member re-reviewed each transcript, assessed coding, and resolved discrepancies. Thematic analysis was used to further interpret the data and identify major themes related to COVID-19 vaccine attitudes across transcripts (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Thematic analysis involves the process of reviewing transcript data, creating codes, and identifying themes and subthemes derived from the codes (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). In our analytic process, all excerpts involving vaccine-related beliefs and attitudes were initially coded under the broad category, or parent code, of ‘vaccine acceptability’. Quotes coded as ‘vaccine acceptability’ were then organised into two broad themes of (1) barriers and (2) facilitators of vaccine acceptability. Within these themes, quotes were then assigned ‘child codes’ to identify subthemes (e.g. fear of side effects). Once themes and subthemes were identified, they were mapped onto levels of the social ecological model framework (e.g. individual, community, etc.) (Kumar et al., Citation2012; Nadarzynski et al., Citation2021), as this model fit well with the identified themes and subthemes.

Ethics

The Kukaa Salama data collection was approved as an amendment to the Tushirikiane trial by the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board (REB) (reference 37496); the Mildmay Uganda Research Ethics Committee (reference 0806-2019); and the Uganda National Council for Science & Technology (reference HS 2716). All participants have provided written informed consent for inclusion in this study. The Kukaa Salama trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov Registry (NCT04631367).

Results

Quantitative findings

A total of 326 refugees (age 16–24) who completed the COVID-19 module were included in this analysis, representing 72.2% of the original cohort. The gender distribution among our sample was nearly evenly split between cisgender men and cisgender women. However, we were not able to include the 1 transgender person in data analysis due to the insufficient sample size and to ensure confidentiality. The average age of participants was 19.9 years (standard deviation: 2.4) ().

Table 1. Distribution of demographic factors and associations with vaccine acceptance among urban refugee youth survey participants in Kampala, Uganda (n = 326).

Most participants (n = 227) were from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) (69.6%) or Burundi (16.0%). Vaccine acceptance was low, with only 18.1% of refugee youth participants responding they were very likely to accept an effective COVID-19 vaccine (). In crude analyses, older age (odds ratio [OR]: 1.18, CI: 1.05–1.34, p = 0.005) and birth country (outside of DRC and Burundi) (OR: 0.27, CI: 0.08–0.92, p = 0.026) were associated with vaccine acceptance. After adjusting for each of these factors, as well as informal settlement and gender, odds of vaccine acceptance remained associated with older age (adjusted OR [aOR]: 1.16, 95% CI: 1.02–1.31, p = 0.023). There were also differences in acceptance by country of birth ().

Qualitative findings

A total of 24 urban refugees and six KI completed in-depth individual interviews on the topic of COVID-19 experiences, including attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccines. Interviews were approximately one hour in duration and conducted in all study languages by trained research assistants. Most refugees (mean age = 20.7, SD = 2.3) were Congolese (n = 14), followed by Burundian (n = 8) (). KI included 3 women and 3 men who were social and health care providers with experience working with refugees in Kampala as well as policy makers; further socio-demographics were not collected from KI to maintain confidentiality.

Table 2. Socio-demographic characteristics of qualitative participants among a sample of refugee youth in Kampala, Uganda (n = 24).

Barriers and facilitators to vaccine acceptability emerged as overarching themes, with sub-themes detailed below organised following social-ecological approaches to vaccine acceptability (Kumar et al., Citation2012; Nadarzynski et al., Citation2021).

Theme 1: barriers to vaccine acceptability

Barriers to vaccine acceptability included individual-level factors, including fear of side effects, mistrust and conspiracy beliefs, and low vaccine awareness and knowledge; and community-level factors, including negative community and family attitudes.

Individual level: fear of side effects

Vaccine fears included safety and negative side effects of the COVID-19 vaccine. Respondents reported beliefs that the vaccine caused side effects that included serious health complications. As one participant elaborated, ‘It is not bad to get the injection but I’m also afraid of [it] … according to the news I watch some people are becoming paralyzed, that the vaccine is introducing new diseases’ (ID#15; age 17, woman). Others wanted to know more information about possible side effects before taking the vaccine:

I cannot accept it even though there are some people who are injected before me. I have to be informed about it, how it works and what are side effects … they cannot inject you something you don’t know, which is going to spoil your body and you develop very serious health problems. (ID#7; age 22, man)

Fear of side effects may be exacerbated from vaccine fears in other global contexts. For instance, a young woman explained ‘they say that there are some people who received it and died immediately or after some days, all that can make me fear it … There are people we know who live outside, in Europe and America who told us those vaccines are bad, they can inject you then bring you serious diseases’ (ID#5; age 21, woman). Fear of side effects is not a new phenomenon and exists with other medical treatment issues. As described by a KI: ‘take for example ARVs (antiretroviral therapy), we have been with them for a while but people still claim that you go crazy when you take ARVs’ (KI#6; Ministry of Health representative).

Individual level: mistrust and conspiracy beliefs

Other respondents shared attitudes of mistrust, informed by COVID-19 vaccine-related conspiracies. One participant shared two examples of myths circulating in the community. When asked about what these myths about the vaccine were, the participant elaborated that: ‘The vaccine is meant to eliminate Africans. The other is, we are refugees in this country and they want to find a way to get rid of us’ (KI# 6; Ministry of Health representative). This quotation signals concerns that there may be significant intent to harm refugees with the vaccine. There were also participants that wondered if where the vaccine was developed influenced its appropriateness for the Ugandan context. Another young man also noted that messages regarding the harms of COVID-19 may impact not only vaccination acceptability but other preventive practices such as wearing face masks:

When they advise us to wear masks you refuse and say that maybe they have put bad things in the masks to kill us, and again you may think that the medicine they bring for COVID-19 are there to kill people. (ID#14; age 24, man)

Through information presented on online platforms, others came to believe that the vaccine was intended to cause harm: ‘I don’t know but I always hear them talking bad of the vaccine, that it has come to kill people and not to protect them … Because they watched on internet people have died after being injected the vaccine’ (ID#11; age 17, man). Other participants discussed mistrust from information largely shared through personal engagement with social media or messaging applications.

Individual level: low vaccine awareness and knowledge

One KI shared their belief that youth in Africa needed more information, or to be further ‘sensitized,’ about the COVID-19 vaccine to improve acceptability and reduce negative thinking about the vaccine:

As of today, African youth are very negative to the vaccine … It will depend on how we prepare them and sensitize them about the process … But as we stand right now, majority of youth are not ready to receive the vaccine because they have very negative thinking about the vaccine. (KI# 3; refugee youth advocate)

There also appeared to be a lack of knowledge regarding vaccine eligibility. Two respondents shared beliefs that only those who had previously contracted COVID-19, or who are currently infected, were eligible for vaccination – possibly indicating that vaccines may be viewed as treatment instead of prevention measures. For instance, one refugee stated that ‘if I appear like someone who has it [COVID-19], I will accept it [vaccine] because it will help me fight the virus in my body but if not, I won’t accept it, they cannot inject me [with] the vaccine when I am not yet infected.’ (ID#18; age 16, woman). Others also reinforced this belief that vaccines were only for those already infected with COVID-19: ‘I think that vaccine is for those who have the virus to avoid them getting it again.’ (ID#7; age 22, young man)

Finally, a lack of awareness of vaccination benefits could also stem from certain religious beliefs, illustrated by this participant’s narrative: ‘I cannot accept the vaccine … Only God has the real vaccine. If it’s death I will die, I can’t accept the vaccine’ (ID#24; age 18, woman).

Community level: misinformed healthcare, community, and family attitudes

Respondents shared how fear and hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccines in communities and families influence their own perceptions of the vaccine. For instance, one refugee explained:

Accepting it will be very hard because I don’t trust it, the way they talk about it badly in my community. They said that it is bad, that it has come to kill people, to spoil our bodies and kill you when you’re still young. If people were talking about positive aspects of it we could easily accept it. (ID#2; age 19, young man)

Yes, you have seen parents rejecting vaccines from the government given at school. Parents have a lot of influence on their children, if a parent does not believe in taking the vaccine, do you think the children will accept it? No. It will in fact be the parent telling them, ‘if I see you taking the covid vaccine do not come back to my home’ or ‘I do not want you to take up that covid vaccine.’ This is majorly from the bad publicity that the vaccine has received. (KI# 2; refugee sex worker representative)

Further, health and social service providers also expressed a lack of COVID-19 vaccine knowledge that made it difficult for them to provide information to clients and recipients of services. This lack of knowledge at the healthcare level may impact vaccine uptake. For instance, a social service provider described:

You cannot sensitize about something you do not know. I personally do not know how the vaccine works. For instance, when you take a baby to hospital and a doctor puts 2 drops of something into your baby’s mouth, you want to know what it does. In the same we need to understand how this vaccine works. You have seen video clips of people being injected and they die right in front of the camera. This is doing lots of harm because there is a fear that this may actually happen to them. (KI#2, refugee sex worker representative)

Theme 2: facilitators of vaccine acceptability

Facilitators of vaccine acceptance include: individual level factors of perceived vaccine safety and perceived vaccination benefits; community-level factors, specifically community-engaged health promotion; organisational and practice setting factors, involving tailored COVID-19 services for refugees; and the policy environment, including political support for vaccines.

Individual level: perceived vaccine safety

For many participants, vaccine acceptance was contingent on safety and no significant side effects. One young woman noted that when the vaccine is available, she ‘can first ask if it doesn’t have side effects, if not I can have the vaccine because I don’t want to get any side effects’ (ID#10; age 23, woman). Other refugees shared this belief, stating that ‘if they inform us that it is here, safe, and some people have received then recovered and remain okay, then we will also accept it’ (ID#12; age 22, man). Another young woman explained how she would research vaccines to evaluate safety:

[To see] the side effect I can also use internet [to] search for the name of it … because even the effects of some were shown so you can easily know that it is not good. I will go for the one that the effects are least compared to other ones. (ID#1; age 22, woman)

Individual level: perceived vaccine benefits

Participants expressed thatperceived vaccine benefits were a motivation for acceptability, in particular the understanding of protection from COVID-19 infection. For instance, a participant described: ‘I don’t have a choice; I can take it because I want to protect myself against COVID’ (ID#9; age 24, man). Others discussed the peace of mind knowing one would be protected from infection: ‘I will get it and it will help you know that you are now safe and you cannot easily get infected’ (ID#23; age 19, woman) and ‘it can help me to prevent the infection, never being affected’ (ID#16; age 20, man).

Some presented tangible benefits of vaccinations as a motivation for uptake. These tangible benefits included being able to work without fear: ‘I can take it … I want to protect myself from COVID-19, I will do my work without problem’ (ID#4; age 20, woman). Another perceived benefit was not needing to practice other preventive measures: ‘Yes, I would like to get the vaccine … Because I won't bother to put on masks or wash hands’ (ID#21; age 21, man). Being vaccinated was also discussed as a requirement in the asylum-seeking process:

Am sure they will take the vaccine because the process of getting asylum is really long and tedious, so if at the last minute one is asked about being vaccinated and they have no positive response, it would mean refusal and redoing that process is so difficult. So am sure all those that want asylum will take the vaccine willingly … So if they say that vaccination is a ticket, ahhhhh, they will all go for vaccination. (KI# 6; Ministry of Health representative)

Community level: community-engaged health promotion

Engaging community leaders and champions in health promotion campaigns was recommended for increasing vaccine acceptability. For instance, such campaigns could share experiences of non-serious side effects with communities to increase acceptability. When the interviewer asked: ‘How can you know that it has side effects?’, a participant described:

They said they will start by [vaccinating] elderly people and am sure after vaccinating some people we will get testimonies on television to help people understand that it is safe. Even someone from the community can testify with his or her experience to motivate others. (ID#14, age 24, man)

We also need to educate the church leaders and any other leaders that have a negative attitude towards the vaccine. There is someone who said we are in the end days and they are giving you the mark of the beast. This is a serious conversation with the leaders that needs to be conducted. (KI#3, refugee youth advocate)

Organisational and practice setting: tailored COVID-19 services for refugees

Engagement of healthcare workers in community mobilisation was identified as an important strategy for dispelling COVID-19 vaccine fears. For example, a KI suggested that health workers themselves may need sensitisation toward the vaccine: ‘Even among those essential staff that you mentioned, there are still some with stigma towards the vaccine’ (KI#2; refugee sex worker representative).

Others discussed the larger social environment where refugees needed both vaccine information but also increased access to COVID-19 testing. This tailored information needs to address the lived realities of young refugees, who experience socio-economic stressors and do not yet have access to vaccines due to supply limitations:

You need to tailor the campaign towards the prevailing situation because many people are fatigued with messages on COVID … How can you talk about COVID without addressing the social-economic impact of COVID? The vaccination that is ongoing, has a number of people with questions that need answers: but also most people in that age group are not part of the people being vaccinated currently because we do not have enough vaccines. We may need to provide a lot of information why they are not being targeted. (KI#4; Ministry of Education representative)

Policy environment: political support for vaccines

Participants shared how government support of vaccines would increase their acceptance. For instance, informants described that government officials publicly demonstrating vaccine uptake could build public confidence:

There is nothing people can refuse if the government accepts it … if they want the vaccine to be accepted by population, they should start by injecting it to all members of parliament and ministers in public places to give a good example and the population will easily follow. (KI#1; sexual minority representative)

Refugee inclusion and access integrated into national COVID-19 vaccine distribution plans were also identified as critical to support vaccine acceptability with refugees.

[As] much as we are so positive and are ready to teach people to accept the vaccine, we do not see anywhere in planning where refugees are mentioned. This was the case even for the yellow fever vaccine where the entire country had access to the vaccine except refugees … I have not heard anything from UNHCR or any comment from them on the vaccine and this leaves us questioning everything. Are we even considered? Many refugee leaders are asking these questions; ‘There is a vaccine but shall we ever get a chance to get to it? If yes, why has there not been a conversation about vaccinating refugees?’. (KI#3, refugee youth advocate)

Discussion

Findings from this multi-method study identify low acceptability (18.1%) of an effective COVID-19 vaccine among a sample of urban refugees (age 16–24) in Kampala, and barriers and facilitators to vaccine acceptability that span individual and community levels, organisational and practice settings, and policy environments. These findings align with research on the importance of understanding and addressing multi-level contextual factors that shape COVID-19 vaccine acceptance (Lazarus et al., Citation2021; Sallam, Citation2021; Thomas et al., Citation2021). Participant narratives reflect the utility of a social ecological approach (Kumar et al., Citation2012; Nadarzynski et al., Citation2021) () to understand COVID-19 vaccine acceptability among young urban refugees and can guide the development of contextually tailored vaccine strategies.

The low vaccine acceptability among this sample of refugee, age 16-24, in Kampala is alarming and speaks to the urgent need to bolster public literacy prior to mass vaccine distribution for COVID-19 boosters and other health vaccines. Vaccine literacy materials and resources must also be available among healthcare providers to support vaccine uptake across communities. This finding, combined with different vaccine acceptability among refugees by country of origin, speaks to the need to better understand heterogeneity in vaccine acceptability between and within contexts and to tailor vaccine messaging for refugee communities (Mipatrini et al., Citation2017). Sociocultural beliefs and trust in medical institutions are key components of vaccine acceptability that may be strained among refugees (Lazarus et al., Citation2021; Sallam, Citation2021; Thomas et al., Citation2021), which we also noted in qualitative data regarding mistrust and conspiracy theories. This underscores the need to ensure COVID-19 implementation approaches address these community narratives of mistrust, perhaps as indicated from our qualitative findings, through vaccine safety assurances and political leadership support.

Findings corroborate multi-level factors linked with vaccine acceptability in a systematic review among men who have sex with men across multiple vaccines (e.g. HPV) (Nadarzynski et al., Citation2021). Our findings indicate a lack of knowledge and awareness of COVID-19 vaccines among urban refugee youth in Kampala, similarly reported among internally displaced persons in the DRC (Claude et al., Citation2020). Lack of awareness of vaccination campaigns among refugee and displaced persons has also been reported for other vaccines in European (Mipatrini et al., Citation2017) and South Asian (Feldstein et al., Citation2020) contexts. Similar to other studies with non-refugees in Uganda (Kanyike et al., Citation2021; Kasozi et al., Citation2021), and with non-refugee samples across other LMICs (Bono et al., Citation2021; Lazarus et al., Citation2021), we found that fear of side effects was a barrier to COVID-19 vaccine acceptability. Negative messaging on social media also reduced vaccine acceptability, a factor reported with non-refugees in Uganda (Kanyike et al., Citation2021) and in other global contexts (Hou et al., Citation2021). These findings signal the potential to harness online platforms to develop tailored vaccine campaigns for urban refugee youth to help promote COVID-19 acceptance.

Facilitators to COVID-19 vaccine acceptability included supportive health services and government support. This corroborates research with non-refugee populations in Uganda that found the most trusted sources for COVID-19 vaccine decision making were health workers and the government (Solís Arce et al., Citation2021). Our findings align with prior research with migrants in the European region for other infectious disease vaccines, which reported that vaccine acceptability was linked with peer and familial support, trustworthy and culturally sensitive health practitioners, and tailored information (Driedger et al., Citation2018). Our findings also build on studies with non-refugees demonstrating that perceived COVID-19 vaccine benefits increase acceptability (Kanyike et al., Citation2021; Solís Arce et al., Citation2021).

The study findings indicate various strategies that can be implemented to improve COVID-19 vaccine acceptability among young refugees. For example, health workers who provide services to refugees must engage in culturally sensitive care, involve community ambassadors, create community-engaged health promotion initiatives, and meet linguistic needs (Bartovic et al., Citation2021). Development of outreach methods with refugee community organisations, including evaluating refugee community knowledge of COVID-19 and vaccines, may also be effective (Clarke et al., Citation2021). Vaccine literacy can address medical mistrust and hesitancy identified among young urban refugees toward other infectious diseases (e.g. HIV), and vaccines spanning a range of health issues, including through visible government support.

Study limitations include the non-random sample and cross-sectional data collection that limit generalisability. A longitudinal design would provide insight into changes in acceptability over time, particularly as COVID-19 vaccines and boosters are becoming more available in Uganda. We did not include measures of vaccine hesitancy in the survey, and this could have provided a more comprehensive picture. While the vaccine acceptance scale had been used in prior research, it was skewed positively and future research could use a more balanced scale. Finally, vaccine acceptability does not equate with uptake (Vermandere et al., Citation2014), so future studies could explore factors associated with uptake among urban refugee youth once the COVID-19 vaccine boosters are more widely available. In spite of these limitations, this study provides multi-method insights that contribute to the limited knowledge base of refugee vaccine acceptability in LMICs, particularly among young people.

Conclusion

Results signal the urgent need to address social ecological factors () that shape vaccine acceptability among young urban refugees in Kampala. This is a call to action to tailor vaccine distribution for young people for COVID-19 – and other health issues – and to recognise the heterogeneity in acceptability among refugees. It is essential to mobilise strategies to improve vaccination acceptability among young refugees through improved health care system interactions (Bartovic et al., Citation2021), outreach (Clarke et al., Citation2021), and vaccine literacy initiatives tailored to the needs of refugees in urban contexts. As reported by the United Nations Development Programme, as of August 2022, 72.4% of persons living in high-income countries have received at least one COVID-19 vaccination dose compared with 21.8% in low-income countries (UNDP, Citation2022). Thus persons in high-income countries – more than 3.3 fold-more likely to access a COVID-19 vaccine – are less vulnerable to virus variants and new waves and the socio-economic recovery will be expedited. While understanding COVID-19 acceptability among young urban refugees is an important first step, access barriers must also be addressed in refugee vaccination plans to advance global refugee vaccine equity.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. Funders played no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, nor the writing of the report or the decision to submit for publication. We acknowledge the support of Young African Refugees for Integral Development (YARID), International Research Consortium (IRC) Kampala, Ugandan Ministry of Health, OGERA, as well as the peer navigators, research assistants and coordinators.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bartovic, J., Datta, S. S., Severoni, S., & D’Anna, V. (2021). Ensuring equitable access to vaccines for refugees and migrants during the COVID-19 pandemic. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 99(1), 3–3A. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.20.267690

- Bono, S. A., Villela, E. F. d. M., Siau, C. S., Chen, W. S., Pengpid, S., Hasan, M. T., Sessou, P., Ditekemena, J. D., Amodan, B. O., Hosseinipour, M. C., Dolo, H., Fodjo, J. N. S., Low, W. Y., & Colebunders, R. (2021). Factors affecting COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: An international survey among low-and middle-income countries. Vaccines, 9(5), 515. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines905051

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Guidance for unvaccinated people: How to protect yourself and others.

- Clarke, S. K., Kumar, G. S., Sutton, J., Atem, J., Banerji, A., Brindamour, M., Geltman, P., & Zaaeed, N. (2021). Potential impact of COVID-19 on recently resettled refugee populations in the United States and Canada: Perspectives of refugee healthcare providers. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 23(1), 184–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-020-01104-4

- Claude, K. M., Serge, M. S., Alexis, K. K., & Hawkes, M. T. (2020). Prevention of COVID-19 in internally displaced persons camps in War-Torn North Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo: A mixed-methods study. Global Health: Science and Practice, 8(4), 638–653. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-20-00272

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed., pp. 1–26). London: SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.2307/3152153.

- Dedoose. (2016). Web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data (7.0.23). SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC.

- Driedger, M., Mayhew, A., Welch, V., Agbata, E., Gruner, D., Greenaway, C., Noori, T., Sandu, M., Sangou, T., Mathew, C., Kaur, H., Pareek, M., & Pottie, K. (2018). Accessibility and acceptability of infectious disease interventions among migrants in the EU/EEA: A CERQual systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(11), Article 2329. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112329

- Feldstein, L. R., Bennett, S. D., Estivariz, C. F., Cooley, G. M., Weil, L., Billah, M. M., Uzzaman, M. S., Bohara, R., Vandenent, M., Adhikari, J. M., Leidman, E., Hasan, M., Akhtar, S., Hasman, A., Conklin, L., Ehlman, D., Alamgir, A., & Flora, M. S. (2020). Vaccination coverage survey and seroprevalence among forcibly displaced Rohingya children, Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 2018: A cross-sectional study. PLOS Medicine, 17(3), Article e1003071. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003071

- Hou, Z., Tong, Y., Du, F., Lu, L., Zhao, S., Yu, K., Piatek, S. J., Larson, H. J., & Lin, L. (2021). Assessing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, confidence and public engagement: A global social listening study. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3775544

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). (2022). Uganda. University of Washington, Seattle, United States. 2022. Downloaded July 20, 2022 from: https://www.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/covid_briefs/190_briefing_Uganda.pdf.

- Kanyike, A. M., Olum, R., Kajjimu, J., Ojilong, D., Akech, G. M., Nassozi, D. R., Agira, D., Wamala, N. K., Asiimwe, A., Matovu, D., Nakimuli, A. B., Lyavala, M., Kulwenza, P., Kiwumulo, J., & Bongomin, F. (2021). Acceptance of the coronavirus disease-2019 vaccine among medical students in Uganda. Tropical Medicine and Health, 49(1), Article 37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-021-00331-1

- Kasozi, K. I., Laudisoit, A., Osuwat, L. O., Batiha, G. E.-S., Al Omairi, N. E., Aigbogun, E., Ninsiima, H. I., Usman, I. M., DeTora, L. M., MacLeod, E. T., Nalugo, H., Crawley, F. P., Bierer, B. E., Mwandah, D. C., Kato, C. D., Kiyimba, K., Ayikobua, E. T., Lillian, L., Matama, K., … Welburn, S. C. (2021). A descriptive-multivariate analysis of community knowledge, confidence, and trust in COVID-19 clinical trials among healthcare workers in Uganda. Vaccines, 9(3), Article 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9030253

- Kluge, H. H. P., Jakab, Z., Bartovic, J., D’Anna, V., & Severoni, S. (2020). Refugee and migrant health in the COVID-19 response. The Lancet, 395(10232), 1237–1239. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30791-1

- Kumar, S., Quinn, S. C., Kim, K. H., Musa, D., Hilyard, K. M., & Freimuth, V. S. (2012). The social ecological model as a framework for the determinants of 2009 H1N1 vaccine uptake in the US. Health Education & Behavior, 39(2), 229–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198111415105

- Lazarus, J. V., Ratzan, S. C., Palayew, A., Gostin, L. O., Larson, H. J., Rabin, K., Kimball, S., & El-Mohandes, A. (2021). A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nature Medicine, 27(2), 225–228. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9

- Logie, C., Okumu, M., Mwima, S., Hakiza, R., Irungi, K. P., Kyambadde, P., Kironde, E., & Narasimhan, M. (2019). Social ecological factors associated with experiencing violence among urban refugee and displaced adolescent girls and young women in informal settlements in Kampala, Uganda: A cross-sectional study. Conflict and Health, 13(1), Article 60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-019-0242-9

- Logie, C. H., Okumu, M., Berry, I., Hakiza, R., Kibuuka Musoke, D., Kyambadde, P., Mwima, S., Lester, R. T., Perez-Brumer, A. G., Baral, S., & Mbuagbaw, L. (2021). Kukaa Salama (staying safe): Study protocol for a pre/post-trial of an interactive mHealth intervention for increasing COVID-19 prevention practices with urban refugee youth in Kampala, Uganda. BMJ Open, 11(11), Article e055530. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055530

- Mcleroy, K., Bibeau, D. L., Steckler, A., & Glanz, K. (1988). An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly, 15(4), 351–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019818801500401

- Meteke, S., Stefopulos, M., Als, D., Gaffey, M. F., Kamali, M., Siddiqui, F. J., Munyuzangabo, M., Jain, R. P., Shah, S., Radhakrishnan, A., Ataullahjan, A., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2020). Delivering infectious disease interventions to women and children in conflict settings: A systematic review. BMJ Global Health, 5(Suppl 1), Article e001967. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001967

- Mipatrini, D., Stefanelli, P., Severoni, S., & Rezza, G. (2017). Vaccinations in migrants and refugees: A challenge for European health systems. A systematic review of current scientific evidence. Pathogens and Global Health, 111(2), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/20477724.2017.1281374

- Nadarzynski, T., Frost, M., Miller, D., Wheldon, C. W., Wiernik, B. M., Zou, H., Richardson, D., Marlow, L. A. V., Smith, H., Jones, C. J., & Llewellyn, C. (2021). Vaccine acceptability, uptake and completion amongst men who have sex with men: A systematic review, meta-analysis and theoretical framework. Vaccine, 39(27), 3565–3581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.05.013

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2020). What is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on immigrants and their children?

- Sabila, S., & Silver, I. (2020). Cities as partners: The case of Kampala. Forced Migration Review, 63(February), 41–43. https://www.fmreview.org/cities/saliba-silver

- Sallam, M. (2021). COVID-19 Vaccine hesitancy worldwide: A concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines, 9(2), Article 160. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/9/2/160. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9020160

- Singh, L., Singh, N. S., Nezafat Maldonado, B., Tweed, S., Blanchet, K., & Graham, W. J. (2020). What does ‘leave no one behind’ mean for humanitarian crises-affected populations in the COVID-19 pandemic? BMJ Global Health, 5(4), Article e002540. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002540

- Solís Arce, J. S., Warren, S. S., Meriggi, N. F., Scacco, A., McMurry, N., Voors, M., Syunyaev, G., Abdul Malik, A., Aboutajdine, S., Armand, A., Asad, S., Augsburg, B., Bancalari, A., Björkman Nyqvist, M., Borisova, E., Manuel Bosancianu, C., Cheema, A., Collins, E., Zia Farooqi, A., … Mushfiq Mobarak, A. (2021). COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitancy in Low and Middle Income Countries, and Implications for Messaging. MedRxiv.

- Thomas, C. M., Osterholm, M. T., & Stauffer, W. M. (2021). Critical considerations for COVID-19 vaccination of refugees, immigrants, and migrants. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 104(2), 433–435. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-1614

- UNHCR. (2020). Global trends: Forced displacement in 2020 (Issue 265). https://www.unhcr.org/60b638e37/unhcr-global-trends-2020.

- UNHCR. (2021). Uganda - Refugee Statistics April 2021 (Issue April).

- UNHCR. (2022). Uganda - Refugee Statistics January 2022 Kampala. January, 1.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2022). Data Futures Platform: Global Dashboard for Vaccine Equity. New York, NY. Accessed March 2, 2023 at https://data.undp.org/vaccine-equity/

- Vermandere, H., Naanyu, V., Mabeya, H., Broeck, D. V., Michielsen, K., & Degomme, O. (2014). Determinants of acceptance and subsequent uptake of the HPV vaccine in a cohort in Eldoret, Kenya. PLoS ONE, 9(10), Article e109353. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0109353

- World Health Organization. (2019). Delivery of immunization services for refugees and migrants.

- Yunus, M., Donaldson, C., & Perron, J.-L. (2020). COVID-19 Vaccines a global common good. The Lancet Healthy Longevity, 1(1), e6–e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-7568(20)30003-9