ABSTRACT

Impeded access to health services is a major factor influencing migrant health. In Uganda, previous research has shown lower utilisation of health services for young rural–urban migrants compared to their non-migrant counterparts. However, access to health services does not start at utilisation, but can be hampered by being able to identify a need for care. Using qualitative methods, we aimed to explore young rural–urban migrants’ perceptions of health and patterns of engagement with health services. We analysed, using thematic analysis, a purposive sample of 18 in-depth interviews with 10 young people who had recently migrated within Uganda. Our results are presented through a framework conceptualising access at the intersection between abilities of people and characteristics of services. Participants perceived a need for care mostly through serious crises. Their ability to obtain care was hindered by a lack of resources, as well as the relative social isolation brought by migration. Our study highlights other barriers to accessing care such as the role of social norms and HIV-related stigma in health issues prioritisation, and healthcare workers’ attitudes. This knowledge can inform approaches to ensure that community-based services are able to support healthcare access and improved health outcomes for this vulnerable group.

Background

Adolescence and young adulthood are crucial developmental periods. Migrating away from the usual social support systems at this point could bring unique stressors (Yu et al., Citation2019), for example by exacerbating certain mental and physical health risk factors: exploitative relationships, violence, increased use of drugs and alcohol, etc. (Nkosi et al., Citation2019; Yu et al., Citation2019). Even though young people’s healthcare needs might be lower compared to infants and older people, evidence shows that their social position such as their age, gender, marital and socio-economic status can exacerbate marginalisation and vulnerability to poor health (Nkosi et al., Citation2019). Young internal migrants (migrating within their country of origin), especially when coming from disadvantaged groups, are therefore in a precarious position, as they struggle to find their feet in a new and challenging environment. A study of young rural–urban migrants may also give insights into challenges facing urban youth in resource scarce contexts. Recent research suggests that more than two-third of the sub-Saharan African urban population reside in slum settlements characterised by poverty, marginalisation and a lack of socio-economic opportunities (Kabiru et al., Citation2013).

Access to healthcare is a major factor in overall migrant health. Although rural–urban migration may give access to better health services, migrants face specific challenges to accessing services in resource-stretched settings within sub-Saharan Africa and are shown to utilise services less than their non-migrants counterparts (Ginsburg et al., Citation2021). For example, in Kenya, perceived discrimination, language barriers and documentation requirements prevent migrants from using health services (Arnold et al., Citation2014). These perceived barriers negatively influence migrants’ perceptions of their deservingness for services, and overall healthcare-seeking behaviour (Legido-Quigley et al., Citation2019; Mosca et al., Citation2017; Wickramage et al., Citation2018).

In Uganda, a recent study comparing utilisation of sexual health services (SHR) in young rural–urban migrants compared to local young people living in the streets shows lower utilisation rates in migrants and identified migration as the main predictor of SRH services use (Bwambale et al., Citation2021). However, access to healthcare does not start at the point of using health services but at identifying a need for care and acting accordingly. A better understanding of the perceptions of access to health services in a group of young mobile people in this context could help build welcoming care facilities for young people moving to urban areas and address the delays in seeking healthcare for this group. Our study aims to contribute to filling this gap by examining accounts of young rural–urban migrants’ lives in a trading centre in Kalungu District, Uganda, and exploring how their experiences might shape their perceptions of health and access to health services.

Conceptualisations of access to healthcare

Although precisely what is constituted within the definition of access is contested, equity of access is a stated objective of many healthcare systems (Dixon-Woods et al., Citation2006; Richard et al., Citation2016). For some authors, access is purely a matter of supply of health services (availability, quality, costs), which should be equal for people in equal need (Goddard & Smith, Citation2001). For others, access is the result of an interaction between supply-side and demand-side factors (Mooney, Citation1983), such as people’s knowledge, attitudes and skills. The concept of candidacy, widely applied to healthcare, describes the ways in which people’s eligibility for care is not based on a single decision. Rather, access is constantly negotiated between health services and individuals (Dixon-Woods et al., Citation2006; Mackenzie et al., Citation2013; Nkosi et al., Citation2019).

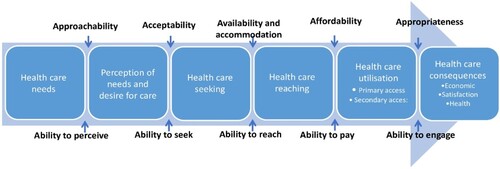

This analysis is guided by a framework conceptualised by Levesque et al. (Citation2013) which considers both structural factors of health systems and capabilities of the individuals in their physical and social environments; access to healthcare is put at the interface of those two. It is a patient-centred framework which builds on a synthesis of published literature on the conceptualisation of access. Additionally, this framework provides a broad scope and systematic way of studying access that gives room to both supply and demand sides of the interaction between potential users and services. Access is here defined as ‘the opportunity to reach and obtain appropriate health care services in situations of perceived need for care’ and is different from accessibility, which is a property of services. It encompasses the possibility to identify healthcare needs, to seek then reach healthcare services, to be offered appropriate services, and to use them (Levesque et al., Citation2013). Five main domains of health services accessibility are conceptualised: approachability, acceptability, availability, affordability and appropriateness. These domains relate to five dimensions of abilities: the ability to perceive, seek, reach, pay and engage. In this framework, access encompasses all the steps that enable people to utilise services, from perceiving a need for care, to seeking and reaching care (as shown in the sequence in , moving from left to right). Utilisation thus represents achieved access. In this study, we focus on participants’ perceptions of their abilities and of characteristics of services to uncover potential barriers to access at the different points in the sequence of access to healthcare.

Figure 1. A conceptual framework of access to healthcare. Adapted from `Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations' (Levesque et al., Citation2013), Int J Equity Health 12, 18. CC BY 2.0.

Material and methods

We present the findings from our analysis of in-depth interviews with young migrants, collected for a study of HIV and mobility, exploring the experiences of young people who have recently migrated in Uganda in relation to HIV risks and patterns of engagement with HIV prevention services.

Study setting

The setting is a town with a population of around 24,000 in the Kalungu district of Uganda situated on the highway linking the two cities of Masaka and Kampala, the town is a resting point for long-distance truck drivers on national or international journeys to and from Rwanda, Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of Congo. For people migrating from rural areas to bigger cities, sometimes aiming for the capital city, Kampala, small towns, such as the research setting, are also a first stop, and for some the only stop, where they can get work and a place to stay. Kalungu district has one of the highest rates of HIV prevalence in Uganda, estimated at 12.5% (Kiwuwa-Muyingo et al., Citation2020).

Data collection

The data the present study presents were collected from September 2017 to late 2018 through in-depth interviews of young people aged 16–24 years old who had migrated to the area within the nine months preceding the data collection. For the broader study, the respondents were purposively sampled to reflect the different categories that young migrants fall into (e.g. domestic workers, school attenders, traders, fishers, etc.). In order to include as broad a group as possible we drew on the principles of respondent-driven sampling and recruited through ‘seed’ participants, identified at our preparatory phase who were asked to recruit their peers through their social networks of recent migrants. The seed participants were identified during a formative research phase which consisted of a community entry group discussion with local leaders, social mapping (including youth meeting places), a transect walk, structured observation of youth gathering places, structured observation of entry/exit points, night and weekend observations carried out over 15 days by the local social science team. We refunded transport costs incurred and provided 10,000 Ugandan shillings (£2.50) in recognition of their participation in the interview.

Interviews were conducted by Ugandan social science researchers of the same sex as participants, to facilitate the rapport. A refined sample of participants reflecting a broad range of characteristics and circumstances of the baseline sample was selected for a second wave of interviews, six months after the first one, to capture some of the dynamism of their lives, as well as build rapport and further explore the topics in the first interviews. Interviews were conducted in Luganda using a list of broad themes rather than a formal topic guide, and interviewers were prepared to explore topics young people may introduce themselves. The interviews were recorded with participant consent, then transcribed and translated to English. To avoid a loss of nuance and meaning that could occur with a translation (Green & Thorogood, Citation2018), some quotes, especially idiomatic expressions, were transcribed verbatim then translated in English with attention paid to capturing their equivalent meaning. All audio recordings were summarised into detailed scripts that included a description of the context, reported speech and verbatim quotes. The completeness of the scripts was tested by transcribing verbatim some of the interviews and comparing with draft scripts (Rutakumwa et al., Citation2020).

Sampling strategy

For the present study, all the 43 interviews (31 interviews with 19 males, 12 interviews with 9 females) were initially read to check the content related to information on health and health services. Repeated interviews were prioritised, because they afforded more depth, and some additional health-related topics were brought up solely in second interviews. Finally, we aimed to obtain a roughly even distribution across age and gender, considering the different perceptions of access to healthcare these attributes might result in. In total, 10 interviews of 5 male participants (with repeat interviews) and 8 of 5 female participants (3 repeated and 2 single interviews) – as fewer female participants were recruited for the second wave of data collection – aged between 18 and 24 years were included in the analysis.

Data analysis

A thematic analysis of the data set was conducted to allow for a rich description of key features of the data set as well as the possibility to identify unanticipated patterns (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). This approach also fits well with an exploration of the perceptions of health and access to healthcare in a critical realist stance, according to which participants’ ways of making meaning of their experiences are embedded in a broader social context (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006).

The analysis process began with a familiarisation stage in which the transcripts were read and re-read. Then, using NVivo version 12 PLUS software, scripts were broken down into codes at a semantic level, examining the underlying assumptions that shape the content of the interviews (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Transcripts were coded across all themes, considering that accounts that were not directly related to health or healthcare nonetheless had relevance to their perceptions of health, and would help identify the broader social context. The following step was to identify patterns across the interviews and organise them in themes. Although the analysis had clear aims, the identification of codes was guided by the content of transcripts rather than previous research or literature.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the Uganda Virus Research Institute, the Uganda National Council for Science and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM). Only anonymised data were used; names were replaced by numbers, and personal identifiers were also removed from the body of the scripts.

Findings

Young people mostly originated from other districts in Uganda. They tended to live in shared rental accommodation and had casual employment, for example in a rice farm, metal welding shops (for the males), or, for the females, house maids. Most had dropped out of primary or secondary school due to economic reasons. In explaining their reasons for leaving home and pursuing a migratory path, young people reported that emancipation from the family was motivated by a search for financial and social independence. With this independence, however, came the responsibility for their own security and wellbeing. Participants describe their new environment as one full of risks and threats: food and housing insecurity, drug and alcohol use, unsafe sex, violence. One of the main concerns expressed was a desire for safety, through finding a safe home, friends who would not engage in risky behaviour, and avoiding social isolation. The fact that they are away from their families adds another dimension to sickness compared to a young person who lives with their parents. For them, being sick means that they might not earn a living, be able to feed themselves, be able to afford healthcare costs. They are therefore preoccupied with finding potential sources of support in their new environment, reliable friends, boyfriends/husbands for females. In this section, we detail aspects of their experiences related to accessing healthcare. They are presented through a framework placing access at the intersection between participants’ abilities and different aspects of health services’ accessibility.

Ability to perceive the need for care

The ability to identify whether they are in need of care is determined by factors such as knowledge and beliefs related to health and sickness (Levesque et al., Citation2013).

Meanings of sickness

Participants’ accounts of illness often revolved around the experiences of sick relatives, as those were perceived as more serious and worth seeking care for than their own experiences. Sometimes they would be based on acute health issues that they have themselves suffered from. It is worth noting that one participant was living with a chronic illness from her early years, having acquired HIV through maternal transmission.

The most frequent perception of illness entailed being bedridden and weak. In other words, participants mainly considered an illness as serious if it rendered the sufferer stuck in bed: ‘She was there, time came, and [HIV] weakened her. That is why, you see, I fear it. It weakened her, for four months she was bedridden’ (P16, female, 23). The need to seek care or consider taking medication was consequently tied to this stage of ill-being: ‘Young people often want to go and seek treatment after getting bedridden. Some young people, as long as they are still able to walk, they will not seek health treatment’ (P7, male, 23). One of the consequences of illness therefore was that they would be unable to get out of bed and earn a living. It is at that stage that healthcare seeking was perceived as necessary. Before that, they were likely to use self-medication. According to some participants, their peers apply that same rule when it comes to seeking preventive services, such as HIV testing, ‘Young people say “I go and test, am I sick? I will first get bedridden then I go and test. Why should I go and test when I am not sick?”’ (P12, male, 20–21). In this view, ‘real and serious’ health issues – physically debilitating and interrupting their income generation activities – legitimise the use of health services.

As put by one participant, ‘in most cases, it is sickness that burdens a person’ (P9, female, 21 years). Because of the precarity of their daily life in the trading centre and the fact that they mostly rely on themselves for subsistence and survival, being sick is highly destabilising and burdensome. Not only does it prevent them from earning an income, but they might also need to pay for healthcare. This perception of illness relates to some risk management strategies participants described, for instance, the need to avoid isolation and quickly establish a support system by finding a housemate or a partner, so that someone would be able to care for them or support them financially, in case they became sick.

Additionally, the anxiety associated with illnesses was often at the forefront. Being sick also meant becoming anxious. For example, getting infected with HIV specifically meant that they would ‘get into thoughts, become slim and lose peace’ (P16, female, 23). Although many participants described persistent anxiety symptoms, insomnia, and feelings of hopelessness that they relate to their harsh living conditions, anxiety itself is never portrayed as a health issue, or worth seeking help. It is mostly self-managed, with coping strategies including alcohol and drug consumption: ‘they give you a bottle, you take it and calm the pressure/reduce stress. The pressure/stress you just calm it, for it cannot completely go away’ (P9, female, 21). Some of the functions of alcohol and substance use were to keep young migrants from ‘thinking too much’, a local idiom for depression, and help them ‘sleep till morning’ (P16, female, 23). Furthermore, additional sources of anxiety are avoided at all costs; for some participants, screening for HIV was one of them, because having a positive test would only make them miserable, to the point where they would not have any hope or plan for their future:

If I tested and was found positive, I can die of thoughts but without testing I live normally and do my work without any thoughts. (P8, male 23)

Approachability of health services

Approachability suggests that people facing health needs can identify that health services exist, can be reached and can impact their health (Levesque et al., Citation2013). It is an attribute of health services to be identifiable, clearly visible to those who might need them, and to be considered beneficial.

During interviews, it was implicit that participants considered formal healthcare and health services as valuable in the management of health issues. When prompted on healthcare-seeking behaviours, they often replied with reasons why young people did not use services enough. There was an underlying assumption, unchallenged by participants, that young people would benefit, at least in terms of health, in using health services. Participants were also aware of the existence of different health facilities, public and private, multiple contacts with healthcare providers through health services’ outreach informed them, such as through opportunities for HIV testing. Such services were seen to be for participants who ‘had never got time to go to a health centre, but this time [I] got tested, health workers came in xxxx and [I] was not busy’ (P7, male, 23).

The importance of outreach as a source of information for participants, who had all recently migrated to the trading centre and did not know much about their new place, is also shown by a participant, who, when asked about where young people access health care services and information regarding HIV prevention explained:

The health workers do community outreach like at xxxx’s clinic … A month before, they had come and taught people about family planning and other ladies’ reproductive health concerns … Some young people access health care services from xxxx’s clinic, xxxx health centre and others go to xxxx [local non-governmental organisation]. (P12, female, 19)

Ability to seek care

The ability to seek care refers to the individuals’ capacity to choose to seek care and their knowledge about healthcare options (Levesque et al., Citation2013).

Although, as stated earlier, participants seemed to value the use of health services, they constantly gave reasons why young people do not use health services enough. They often portrayed themselves as interested in healthcare, and willing to seek care but unable to due to various reasons, contrary to some others who ‘are just reluctant to going there (to health services), they keep saying they will go there but they do not’ (P16, female, 23). This could mask an unwillingness to engage with health services, stated in a more socially acceptable way during the interviews, in order to avoid offending the interviewer. Indeed, some participants asked for health advice during the interviews, suggesting that they may have thought of the researchers as connected to the local health clinics, despite explanations and clarifications provided by the interviewers to the contrary.

Healthcare seeking also meant going to a traditional healer especially after having sought formal care without seeing any improvement in their symptoms. A participant expressed that he ‘fell sick with a strange disease’ and that he ‘did not get any help from health facilities, until [he] consulted a traditional healer locally who healed him’ (P12, male, 20–21). They could maintain a sense of control over the outcomes, as there were still things that could be done to ease their symptoms, for example, in the case above, ‘clean his mother’s grave’ as instructed by the healer. Traditional healers helped them make meaning of their bodily experiences at times when formal care did not allow them to. For example, one female participant who took her often sick child to the hospital and was told there was ‘nothing her baby is suffering from’ found a more satisfying explanation with traditional healers: ‘because the baby’s father has other children (twins), [the twins] affected this baby and it often fell sick’ (P8, female, 20). Moreover, she was told about ‘rituals connected to the twins’ she could do to protect her child. Traditional care was an integral part of the range of choices for healthcare.

Acceptability

Acceptability relates to socio-cultural factors that determine the acceptability of different aspects of services, as well as the judged appropriateness for people to engage with services (Levesque et al., Citation2013). Acceptable care had to ensure privacy, in young migrants’ perspectives. Participants often described health facilities as a public space, in which ‘when they go there, they find many other people including those they know well waiting for the same service’ (P3, male, 19). It is difficult to be assured that the reason for consultation would remain private in public facilities. Beyond professional secrecy, privacy was a matter of not being seen by the many people attending the facility at the same time. Therefore, crowded facilities also meant they would be unable to keep their visit private. Private clinics, with fewer visitors, were thought to offer more privacy for that reason.

Second, young people had a preconceived idea of who are suitable candidates for each health facility. For instance,

xxxx (a facility resulting from the collaboration between the Ugandan government and NGOs to provide free HIV services) they in many cases treat children and HIV positive patients … health center III (a public primary care facility) mainly treat pregnant women. (P10, male, 23).

Indeed, this reticence to engage in services alludes to the persistent influence of HIV stigma. When it came to attending a health facility, they feared that people would ‘suspect them of lining up for HIV testing’ (P3, male, 19). The prominence of HIV in the interviews could be a consequence of the questions asked and the initial research question, exploring young people’s experiences in relation to HIV services. However, HIV is a highly visible health issue in their landscape, as the study site is ‘known for’ HIV and most health-related messages aimed at young people are around HIV and AIDS. One of the participants, who was living with HIV, disclosed facing rejection in her workplaces and her everyday relationships. Most participants, to our knowledge as we relied on self-report, did not live with HIV, but the fear of stigma from being associated with HIV was present in their accounts.

Young migrants were sensitive to the attitudes of health care providers when they sought care. The acceptability of a service was judged by the quality of personal interactions with care providers, whether they ‘cared’ (P9, female, 21). Gender norms also seem to influence the perceived acceptability of care. One female participant would go to one facility rather than the other because the healthcare provider was a woman and ‘one can explain her problems to her, she is so easy on women and even young people’ (P13, female, 22). This subtle expression of difficulties regarding seeking care as a woman can also be linked to the gendered judgment regarding sexual behaviour. Female participants weighed the level of social acceptability in their sexual health decisions, as this quote shows:

For us as girls we want condoms that I do not get pregnant. It is the first one or priority, not HIV/AIDS […]. So, for the boy, he does not want to get infected but wants to impregnate you, yet you as a girl you do not want to get pregnant at least you get HIV. It is because for HIV it is not seen that you are infected, but the pregnancy grows in front and there they will know that she got pregnant. (P16, female, 23)

Ability to reach care

The ability to reach care relates to factors that would enable people to physically reach health services (Levesque et al., Citation2013). Participants considered their ability to reach health services hindered by their lack of occupational flexibility. Even when they would want to go to the health centre, they ‘usually do not have time though … [They] have no one to leave here (in the workplace)’ (P16, female, 23). Young migrants earned a living by doing casual work or were hired under tacit and precarious contracts. It was thus difficult to leave their workplaces even when they had a diagnosed health condition. A participant, living with HIV, hoped that disclosing her status to her employers would give her the flexibility required to go to her follow-up consultations:

work had become too much, there was no way [I] could leave and go for [my] drug refills. [I] decided to tell them the truth, so that they would be aware of [my] status. (P9, female, 21)

Availability and accommodation

Availability and accommodation relate to the existence of facilities with a sufficient capacity to produce services that can be reached promptly (Levesque et al., Citation2013). Participants were aware of the availability of health services and that they could be reached in a timely manner in the urban context. However, they situated the difficulty in healthcare providers’ working hours, which were considered too limited and did not fit their schedules, as ‘services are only provided during weekdays … [when] many young people are busy at their places of work’ (P8, male, 23). Some participants seemed to associate the long waiting times with a scarcity of health facilities and suggested that opening more health facilities would alleviate this ‘congestion’ (P8, male, 23). Presumably, spending more time in a health facility increased the risk of being seen which relates to the fear of stigma many participants expressed.

Participants also reported a constant lack of drugs in public health facilities; that even justified why they did not seek care from ‘government health facilities, because in the end they are asked to buy drugs from private facilities’ (P10, male, 23). Consequently, participants generally perceived private facilities as more available because of reduced waiting times and the availability of drugs. However, they were more expensive.

Ability to afford care

The ability to afford care refers to people’s ability to generate economic resources to pay for healthcare services (Levesque et al., Citation2013). Financial means was the topic that participants spontaneously brought up most frequently. Economic hardship was a core reason why they decided to migrate in the first place and moving into the city rarely solved this problem. They had a low capacity to generate economic resources and were often living highly precariously; their income was hardly sufficient for their daily food supply and accommodation. Thus, a health issue that requires seeking care or worse, being admitted in a health facility was a major source of financial distress:

That is to say, we were perplexed. I had saved some money to start up a stall and that was lost, it was spent in hospital and even all what my aunt had … and when we were discharged, I had debts of forty-eight thousand shillings (around £12). (P13, female, 22)

The participants regularly relied on the support of their relatives or partners to be able to afford care. Sometimes, they had to return to their primary home if they could not manage the situation alone anymore; if they got serious diseases, ‘they end up returning to their parents, sometimes they don’t have parents and life becomes too hard for them’ (P10, male, 23). Therefore, besides poverty, their independence, recently earned through migration contributed to reduce their ability to afford healthcare. Having a partner or someone to rely on was even perceived as an insurance that they would be able to deal with such unplanned expenses. As one female participant said, it is an imperative to have a partner that can help gather the money for medical bills because ‘it is not possible for someone who is independent, lacking money, to be sick and admitted at the health centre. Someone can live alone and feed herself but falls sick when she does not have any money with her at home’ (P9, female, 21). To sum up, not only being independent threatened their ability to afford care, being sick was a threat to their independence, as it forced them to seek support from relatives or partners.

Affordability

In the previous section, we focused on participants’ ability to generate financial resources. Here, affordability describes the capacity for people to spend those resources to use health services (Levesque et al., Citation2013). In participants’ perspective, healthcare affordability, can be conceptualised not only in terms of finances, but also time. The cost of consultation or hospitalisation and treatments was unsurprisingly considered high. They were asked for ‘a lot of money’. Moreover, there was an opportunity cost, a loss of revenue, for utilising health services especially in case of hospitalisation. Health services in the region generally require lay care for inpatient care: a family member can be required to stay with the sick relative. For one participant, her child’s hospitalisation resulted not only in a loss of income because of the time she spent not working, but also in a job loss, as she was told ‘no, now that you have spent a period of time without working, we gave your vacancy to someone else’ (P13, female, 22).

Ability to engage

The ability to engage reflects the capacity to participate and get involved in decision making related to care (Levesque et al., Citation2013). Participants’ accounts of their interaction with healthcare workers seemed characterised by an imbalance of power. They expressed undergoing, enduring care rather than actively deciding of its direction. For example, a female participant living with HIV said about having multiple partners: ‘health workers do not allow it’ (P9, female, 21). This shows a judgmental attitude from healthcare providers, which the patient endures. Participants sometimes asked the interviewers questions about their own health or previous experiences with healthcare providers, when they felt comfortable enough with the interviewer. A participant asked, by the end of the interview ‘whether what [I] saw coming out of [my genitals] was truly a coil or not and how long it remains/stays inside [my] body’ (P12, female, 19). Another participant, who was told by a healthcare professional that she had anaemia, did not ask why as they ‘did not talk much [at the time of the consultation] but now [I] want to go back and know why it was like that’ (P8, female, 20). Although they wanted to understand, they had not been able to voice these questions and concerns during the consultations. These interactions reflect difficulties to take ownership of the care process.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the experiences of access to healthcare for young rural–urban migrants in a trading centre in southern Uganda. We did so by considering both their perceptions of health services’ characteristics and how their capabilities show through their own accounts. This study contributes to a growing literature on access to healthcare and mobility in the Global South (Sweileh et al., Citation2018). The focus was shifted from the angle of utilisation, and access is here considered as an opportunity to obtain appropriate care. Exploring and prioritising their perceptions, which are inevitably a reflection of their subjectivity, was central to the analysis.

The results show that participants perceive various health threats (food and housing insecurity, unsafe sex practices for example) from their environment, which have been described in the literature regarding young migrants (Bernays et al., Citation2020) and are thought to contribute to health issues (Kamndaya et al., Citation2014; Mmari et al., Citation2014; Yu et al., Citation2019). This extreme precarity is added to an isolation from their usual social circles, seen for instance in a lack of support in case of illness, putting young migrants in a particularly vulnerable position, which negatively influence their conceptions of health and health services.

Participants tacitly considered that they would benefit from using health services. However, a reluctance to seek care was expressed throughout the interviews, often through a deliberate distancing of healthcare needs on to ‘others’. Until a health problem became debilitating, disrupting their ability to earn an income or socially function, they were not prioritised since there were more pressing concerns such as pursuing economic stability (Bernays et al., Citation2021). These results are consistent with studies using the candidacy framework, exploring how adolescents and young people define their eligibility to healthcare through ‘a series of crises’ (Nkosi et al., Citation2019), acute and specific events that warrant candidacy (Dixon-Woods et al., Citation2006; Kawuma et al., Citation2018). This perspective has been associated, in socio-economically disadvantaged communities, with a lack of a positive conceptualisation of health (Dixon-Woods et al., Citation2006). It could explain participants’ approach to prevention services, for example, HIV testing; the fear of testing was common, because being found positive would bring ‘too many thoughts’ and more disturbance into their lives. This shows a perception of health focused on a diseased state, rather than active seeking or maintenance of a state of wellbeing. This is where health services outreach, shown in this study to have a positive impact on health services approachability and care acceptability could help. We recommend, in order to reduce delays in seeking care, that outreach go beyond HIV and STIs, to be used as an opportunity to expand a positive view on health – as something to be actively sought, protected and maintained – by educating communities on physical and mental wellbeing.

Social norms also contribute to how health issues are prioritised. For example, an unwanted pregnancy or an infection like HIV can be highly stigmatised and therefore be a major source of concern for the person affected and others fearing contagion. Perceived cultural norms and beliefs have been shown to hinder adolescent and young people’s utilisation of health services, especially for sexual and reproductive services, in rural Kwazulu-Natal, in South Africa (Ngwenya et al., Citation2020). On the other hand, we have shown that participants experienced intense emotional distress, but that these are rarely considered to be a health problem that could be mitigated through healthcare seeking. Instead, they are self-managed with alcohol or drugs (Bernays et al., Citation2020). This attitude towards mental health issues could also be related to norms and expectations in their social environment.

Stigma and social values similarly play an important role in the perceived acceptability of services. Ideal candidates for health services were thought to be people living with HIV, pregnant women and children, which leaves little room for young people. This seems mostly related to the fear of the stigma associated with HIV. Previous studies have emphasised the importance of privacy for young people (Abuosi & Anaba, Citation2019), and the role of stigma as a barrier to engaging with health services (Ngwenya et al., Citation2020). Here, privacy goes beyond traditional definitions of professional secrecy in healthcare and encompasses being simply seen entering a health facility. Being away from their usual social circles, one could have thought that young migrants were granted relative anonymity. This study shows that the new social circles young migrants built and their reputation in their new town are considered essential, as they also rely on those relations in case of hardship. The importance of social support for young migrants to adapt to their host city has also been emphasised in a study in China (Yu et al., Citation2019). Alternatively, because rural–urban migrants remain relatively close (in location) to their families and are likely to return home to find support, it can be hypothesised that they need to keep abiding by the norms of their community of origin. These findings highlight the need for stigma-reducing interventions, as well as community-based interventions such as local peer supporters networks (Bernays et al., Citation2021) in order to improve their sense of social inclusion and facilitate their access to and navigation of health services.

Participants’ ability to reach care was diminished by their precarious lifestyle and rigid working patterns. In fact, disadvantaged groups are more likely to lack practical resources such as the transportation or occupational flexibility required to negotiate health services (Arnold et al., Citation2014; Dixon-Woods et al., Citation2006; Nkosi et al., Citation2019). It was expected of health services to compensate for this lack of flexibility by having flexible working hours, being more available.

Difficulties to afford healthcare were a major hindrance to young migrant’s access to healthcare. Because their ability to generate financial resources was limited, they relied on debts and support from their social networks, which were made fragile by their recent migration. The affordability of health services included the opportunity cost of attending them. It is argued that the costs facing deprived communities dissuade them from using health services (Yu et al., Citation2019), especially optional services such as preventive medicine (Dixon-Woods et al., Citation2006). Furthermore, being sick threatened their independence as this burden needs to be shared with partners or relatives. This could further shed light on young migrants’ approaches to accessing health services through acute events perceived as serious, while for prevention, other strategies are envisioned.

Young migrants in our study were sensitive to the attitudes of healthcare providers and expressed being more likely to return to a facility if they perceived the healthcare professional as friendly and concerned with their lives. Healthcare workers attitudes are shown to affect adolescents’ decisions to access health services (Abuosi & Anaba, Citation2019; Homer et al., Citation2018; Jonas et al., Citation2017; Nkosi et al., Citation2019), particularly for females (Jonas et al., Citation2017). Because providers play a central role in ensuring uptake of services, it is important to train and sensitise health providers to these issues (Jonas et al., Citation2017; Nkosi et al., Citation2019).

Strengths and limitations

Although many accounts of diseases revolve around HIV, this analysis incorporates a wide range of concerns regarding health, but also non-health-related aspects of migrants’ lives that proved to be relevant to their access to healthcare. Furthermore, because HIV remains a central public health issue in Uganda, these results are more notably pertinent for access to healthcare in this country. Indeed, HIV shapes perceptions and attitudes of young people regarding health services in general, even for other illnesses.

The first author was not directly involved in the data collection but worked with the research team locally to discuss the meanings and broader context shaping participants’ accounts. Furthermore, the interview summaries were rich in details regarding the environment of the interviews; attitudes (for example, laughs or joking tones) of both the participants and the interviewer were described.

Conclusion

This work explored opportunities to seek and obtain healthcare services in situations of perceived needs, for young rural–urban migrants. The precarity situations participants live in shape their perceptions of health and health services, as health problems had to earn their place in a priority scale determined by urgency. The relative social isolation brought by migration further hindered their ability to afford healthcare services. However, young migrants remain embedded in both the social fabric of their primary and new homes, and social norms and stigma highly influenced their perceptions of health and the acceptability of services. Our study also highlighted the role of health services outreach, which has a positive impact on the approachability of services, and care acceptability. Based on these findings, we recommended the development of community-based interventions building on peers’ networks and the expansion of health services outreach beyond HIV and STIs, so that young people in precarious situations are more able to embrace a view on health as something to be actively sought, protected and maintained.

References

- Abuosi, A. A., & Anaba, E. A. (2019). Barriers on access to and use of adolescent health services in Ghana. Journal of Health Research, 33(3), 197–207. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHR-10-2018-0119

- Arnold, C., Theede, J., & Gagnon, A. (2014). A qualitative exploration of access to urban migrant healthcare in Nairobi, Kenya. Social Science & Medicine, 110, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.019

- Bernays, S., Lanyon, C., Dlamini, V., Ngwenya, N., & Seeley, J. (2020). Being young and on the move in South Africa: How ‘waithood’ exacerbates HIV risks and disrupts the success of current HIV prevention interventions. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 15(4), 368–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450128.2020.1739359

- Bernays, S., Lanyon, C., Tumwesige, E., Aswiime, A., Ngwenya, N., Dlamini, V., Shahmanesh, M., & Seeley, J. (2021). ‘This is what is going to help me’: Developing a co-designed and theoretically informed harm reduction intervention for mobile youth in South Africa and Uganda. Global Public Health, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2021.1953105

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bwambale, M. F., Bukuluki, P., Moyer, C. A., & Van den Borne, B. H. W. (2021). Utilisation of sexual and reproductive health services among street children and young adults in Kampala, Uganda: Does migration matter? BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 169. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06173-1

- Dixon-Woods, M., Cavers, D., Agarwal, S., Annandale, E., Arthur, A., Harvey, J., Hsu, R., Katbamna, S., Olsen, R., Smith, L., Riley, R., & Sutton, A. J. (2006). Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 6(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-6-35

- Ginsburg, C., Collinson, M.A., Gómez-Olivé, F.X. et al. (2021). Internal migration and health in South Africa: determinants of healthcare utilisation in a young adult cohort. BMC Public Health, 21, 554. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10590-6

- Goddard, M., & Smith, P. (2001). Equity of access to health care services : theory and evidence from the UK. Social Science & Medicine, 53(9), 1149–1162. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00415-9

- Green, J., & Thorogood, N. (2018). Qualitative methods for health research (4th ed.). SAGE.

- Homer, C. S. E., Castro Lopes, S., Nove, A., Michel-Schuldt, M., McConville, F., Moyo, N. T., Bokosi, M., & ten Hoope-Bender, P. (2018). Barriers to and strategies for addressing the availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality of the sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn and adolescent health workforce: Addressing the post-2015 agenda. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1686-4

- Jonas, K., Crutzen, R., van den Borne, B., & Reddy, P. (2017). Healthcare workers’ behaviors and personal determinants associated with providing adequate sexual and reproductive healthcare services in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1268-x

- Kabiru, C. W., Izugbara, C. O., & Beguy, D. (2013). The health and wellbeing of young people in sub-Saharan Africa: An under-researched area? BMC International Health and Human Rights, 13(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-698X-13-11

- Kamndaya, M., Thomas, L., Vearey, J., Sartorius, B., & Kazembe, L. (2014). Material deprivation affects high sexual risk behavior among young people in urban slums, South Africa. Journal of Urban Health, 91(3), 581–591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-013-9856-1

- Kawuma, R., Seeley, J., Mupambireyi, Z., Cowan, F., Bernays, S., & Team, T. R. T. (2018). ‘Treatment is not yet necessary’: delays in seeking access to HIV treatment in Uganda and Zimbabwe. African Journal of AIDS Research, 17(3), 217–225. https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2018.1490785

- Kiwuwa-Muyingo, S., Abongomera, G., Mambule, I., Senjovu, D., Katabira, E., Kityo, C., Gibb, D. M., Ford, D., & Seeley, J. (2020). Lessons for test and treat in an antiretroviral programme after decentralisation in Uganda: A retrospective analysis of outcomes in public healthcare facilities within the Lablite project. International Health, 12(5), 429–443. https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihz090

- Legido-Quigley, H., Pocock, N., Tan, S. T., Pajin, L., Suphanchaimat, R., Wickramage, K., McKee, M., & Pottie, K. (2019). Healthcare is not universal if undocumented migrants are excluded. BMJ, 366, Article l4160. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4160

- Levesque, J.-F., Harris, M. F., & Russell, G. (2013). Patient-centred access to health care: Conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. International Journal for Equity in Health, 12(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-12-18

- Mackenzie, M., Conway, E., Hastings, A., Munro, M., & O’Donnell, C. (2013). Is ‘candidacy’ a useful concept for understanding journeys through public services? A critical interpretive literature synthesis. Social Policy & Administration, 47(7), 806–825. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2012.00864.x

- Mmari, K., Blum, R., Sonenstein, F., Marshall, B., Brahmbhatt, H., Venables, E., Delany-Moretlwe, S., Lou, C., Gao, E., Acharya, R., Jejeebhoy, S., & Sangowawa, A. (2014). Adolescents’ perceptions of health from disadvantaged urban communities: Findings from the WAVE study. Social Science & Medicine, 104, 124–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.12.012

- Mooney, G. H. (1983). Equity in health care : Confronting the confusion. Effective Health Care, 1(4), 179–185.

- Mosca, D., Bandara, J., & Kelley, E. (2017). Health of migrants : Resetting the agenda. Report of the 2nd global constitution, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 21-23 February 2017. International Organisation of Migration.

- Ngwenya, N., Nkosi, B., Mchunu, L. S., Ferguson, J., Seeley, J., & Doyle, A. M. (2020). Behavioural and socio-ecological factors that influence access and utilisation of health services by young people living in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: Implications for intervention. PLoS One, 15(4), e0231080. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231080

- Nkosi, B., Seeley, J., Ngwenya, N., Mchunu, S. L., Gumede, D., Ferguson, J., & Doyle, A. M. (2019). Exploring adolescents and young people’s candidacy for utilising health services in a rural district, South Africa. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 195. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-3960-1

- Richard, L., Furler, J., Densley, K., Haggerty, J., Russell, G., Levesque, J.-F., & Gunn, J. (2016). Equity of access to primary healthcare for vulnerable populations: The IMPACT international online survey of innovations. International Journal for Equity in Health, 15(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0351-7

- Rutakumwa, R., Mugisha, J. O., Bernays, S., Kabunga, E., Tumwekwase, G., Mbonye, M., & Seeley, J. (2020). Conducting in-depth interviews with and without voice recorders: A comparative analysis. Qualitative Research, 20(5), 565–581. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794119884806

- Sweileh, W. M., Wickramage, K., Pottie, K., Hui, C., Roberts, B., Sawalha, A. F., & Zyoud, S. H. (2018). Bibliometric analysis of global migration health research in peer-reviewed literature (2000–2016). BMC Public Health, 18(1), 777. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5689-x

- Wickramage, K., Vearey, J., Zwi, A. B., Robinson, C., & Knipper, M. (2018). Migration and health: A global public health research priority. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 987. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5932-5

- Yu, C., Lou, C., Cheng, Y., Cui, Y., Lian, Q., Wang, Z., Gao, E., & Wang, L. (2019). Young internal migrants’ major health issues and health seeking barriers in Shanghai, China: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 336. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6661-0